Abstract

In lithium-ion battery electrodes, repeated lithium insertion and extraction generate compositional gradients and volumetric changes that produce evolving stress fields and eigenstrains, accelerating mechanical degradation. While existing diffusion-induced stress models often capture only elastic behavior, they rarely provide a closed-form analytical treatment of irreversible deformation or its connection to cyclic degradation. In this work, a transparent analytical framework is developed for a planar electrode that explicitly couples lithium diffusion with elastic-plastic deformation, eigenstrain formation, and fracture-aware stress relaxation. The framework provides a means to quantitatively model the evolution of residual stress gradients, revealing the formation of a damaging tensile state at the electrode surface after delithiation and demonstrating how path-dependent irreversible deformation establishes a degradation memory. A parametric study is used to demonstrate the framework’s capability to clarify the influence of diffusivity and yield strength on residual stress development. This framework, which unifies diffusion, plasticity, and fracture in closed-form mechanical relations, provides new physical insight into the origins of chemo-mechanical degradation and offers a computationally efficient tool for guiding the design of durable next-generation electrode materials where chemo-mechanical strains are moderate.

1. Introduction

Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries have become a cornerstone of portable electronics, electric vehicles and grid-storage applications owing to their high energy density and favorable cycle life. However, the repeated lithiation and delithiation of electrode active materials inherently introduces volumetric changes and compositional inhomogeneities, which in turn generate internal stresses that contribute to capacity fade, mechanical cracking and ultimately loss of structural integrity. In particular, diffusion-induced stresses have been widely studied in electrode particles, films and composite architectures.

The long-term performance and reliability of lithium-ion batteries are fundamentally constrained by a range of degradation mechanisms that develop during electrochemical cycling. At the core of battery operation is the repeated insertion (lithiation) and extraction (delithiation) of lithium ions into and from the host electrode materials [1,2,3]. This process is intrinsically coupled with significant volumetric expansion and contraction of the active material’s crystal lattice. Over numerous charge–discharge cycles, these repetitive volume changes generate mechanical stresses that can lead to particle cracking, pulverization, and eventual structural disintegration [4,5,6,7]. The formation of new fracture surfaces exposes fresh electrode material to the electrolyte, promoting parasitic side reactions and continual growth of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) [8,9,10,11]. This, in turn, causes irreversible loss of both cyclable lithium inventory [12,13,14] and active material [15], manifesting macroscopically as capacity fade [16,17] and internal resistance growth [18,19], thereby limiting both lifetime and performance.

Extensive experimental [20,21] and computational studies have sought to unravel these degradation mechanisms [20,22]. While electrochemical diagnostics such as Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Incremental Capacity Analysis provide insight into resistance growth and lithium inventory loss [23], complementary in situ imaging techniques, including X-ray computed tomography and digital image correlation, reveal the evolution of cracking and delamination in electrode microstructures [24,25]. Together, these studies underscore the strong coupling between chemical and mechanical processes and highlight the need for predictive models that bridge microstructural deformation with electrochemical degradation pathways.

A significant body of theoretical work has focused on the mechanical origins of degradation, particularly through diffusion-induced stresses arising from concentration gradients during cycling. Seminal analyses by Christensen and Newman [26] and Zhang et al. [27] modeled lithium insertion as an analog of thermal expansion, enabling computation of elastic stress distributions. Subsequent developments introduced finite-strain plasticity [28], electro-chemo-mechanical coupling at large deformations [28,29], and fracture or damage evolution using phase-field and continuum damage models [30]. These models, validated by experimental techniques such as wafer curvature [31], Raman spectroscopy [32], and digital image correlation [33], provide detailed insight into stress evolution. More recent mesoscale and multiscale simulations [34,35] have revealed how particle interactions and microstructural heterogeneity modulate the stress field during operation. Such particle-based modeling is particularly critical for understanding degradation in next-generation systems, such as all-solid-state batteries, where chemo-mechanical stresses at the interfaces between active particles and the solid electrolyte govern performance and failure [36]. However, simplified geometries that isolate the fundamental coupling between diffusion and constraint remain vital. As shown in studies on electrode coating instabilities [37,38], analytical treatments of constrained expansion provide critical insights into the fracture driving forces that operate across different electrode scales.

There has been considerable progress in understanding the chemo-mechanical degradation of cathode materials. Experimental efforts have provided crucial insights, from post-mortem visualization of intergranular particle fracture [39] to quantitative operando measurements of stress evolution in highly engineered particles [40]. This has been complemented by theoretical work, including the development of elegant analytical solutions for diffusion-induced elastic stress [41], diffusion-induced stress models that explicitly incorporate plasticity and large-deformation electro-chemo-mechanical coupling [42,43,44], and sophisticated numerical simulations that explicitly model cohesive fracture [45]. Despite this progress, a critical gap remains between these approaches. Elastic analytical frameworks, while offering valuable transparency, cannot represent how irreversible plastic strain accumulates to establish a path-dependent degradation memory. Conversely, plasticity-inclusive numerical models, although capable of resolving complex stress–strain histories, are typically formulated as finite-element or related simulations and therefore do not generally yield compact closed-form expressions for the residual stress and eigenstrain fields after delithiation. As a result, the direct mechanistic connection between lithiation-induced plastic compaction and the persistent residual stress state that governs damage in subsequent cycles remains only partially transparent.

While this existing research provides a strong foundation, a complete mechanistic understanding is hindered by two key limitations in the current theoretical landscape. First, an explicit analytical representation of eigenstrain fields, the irreversible misfit strain remaining after delithiation, is needed to model how these strains evolve into residual stresses. Second, the concept of path-dependent degradation, wherein the irreversible plastic strain from prior cycles, representing the permanent microstructural rearrangement and pore collapse observed in granular electrodes [46], creates a persistent stress memory that fundamentally alters the material’s response in all subsequent cycles, is seldom captured in a transparent mechanistic framework. It is important to note that for brittle electrode materials, this plastic deformation serves as a continuum surrogate for the irreversible densification, pore collapse, and micro-crushing that occur within porous secondary particles under the high compressive stresses generated during lithiation.

This study introduces a chemo-mechanical analytical framework developed to bridge these gaps by coupling one-dimensional lithium diffusion with elastic-plastic deformation and eigenstrain theory [47,48]. The model explicitly captures the generation of irreversible plastic strain during lithiation and represents it as eigenstrain in the delithiated state, thereby revealing the path-dependent nature of degradation. Furthermore, a novel fracture-aware capping scheme is introduced to approximate stress relaxation caused by microcracking without requiring computationally intensive simulations. This approach provides a more physically complete picture than simple diffusion-elastic treatments, yet retains the analytical clarity often lost in full-scale finite-element simulations, offering new insight into how irreversible chemo-mechanical deformation drives electrode degradation. In contrast to previous diffusion-induced stress models that include plasticity, which are typically solved numerically in two or three dimensions, the present framework provides closed-form one-dimensional relations linking lithium concentration, plastic strain, and residual stress. This analytical structure makes the role of retained plastic strain as an eigenstrain field, and its contribution to degradation memory, directly accessible in terms of a small set of material and geometric parameters.

By focusing on an illustrative case of small-strain ceramic cathodes such as LiMn2O4 (LMO), the proposed method isolates the essential chemo-mechanical coupling mechanisms while maintaining analytical transparency. The resulting framework is not intended to be a definitive simulation of LMO but rather a tool that elucidates how irreversible deformation, residual stress, and fracture collectively govern mechanical integrity. As such, it provides a mechanistically grounded methodological foundation for future multi-cycle degradation analyses and experimental validation efforts.

2. Methodology

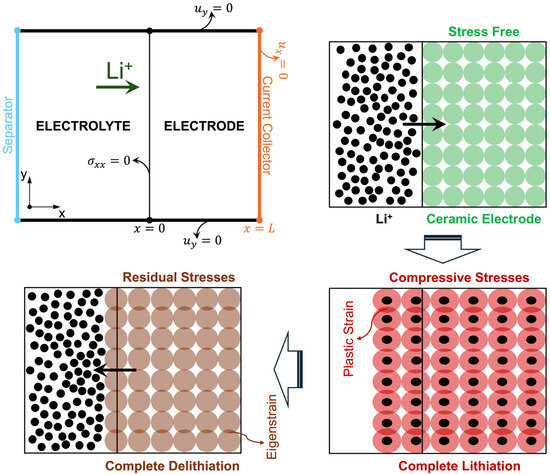

A chemo-mechanical analytical framework was developed to investigate eigenstrain-driven degradation in lithium-ion battery electrodes. The framework couples lithium diffusion, Vegard-induced lattice expansion, elastic-plastic deformation, and residual stress formation under cyclic lithiation and delithiation. The model assumes a planar, one-dimensional electrode geometry, where lithium transport and the resulting mechanical response are represented along the electrode thickness direction, denoted by the spatial coordinate, x. The in-plane direction along the electrode surface is denoted by y, and all fields are taken to depend only on coordinate and time, t, with the in-plane directions treated as uniform as illustrated in Figure 1. This simplified geometry captures the essential through-thickness coupling between lithium concentration gradients and the resulting stress evolution, while remaining analytically tractable. In the present formulation, the current collector is treated as mechanically much stiffer than the active layer, so that its in-plane deformation is negligible and in the limit where the product of collector modulus and thickness greatly exceeds that of the cathode, this stiffness contrast can be represented by a zero macroscopic in-plane strain condition in the active material.

Figure 1.

One-dimensional electrode geometry, boundary conditions, and schematic microstructural evolution underlying the analytical model of a constrained cathode film during a lithiation-delithiation cycle. During lithiation, constrained expansion of the active particles generates compressive contact stresses and plastic compaction. After full delithiation, the retained plastic strain acts as an eigenstrain, producing a residual stress field in the lithium-free electrode.

Figure 1 provides a combined representation of the macroscopic electrode configuration and the underlying microstructural mechanism of degradation. The upper-left panel shows the one-dimensional geometry and boundary conditions used in the analytical model, with a planar cathode film of thickness L bounded by the separator/electrolyte at x = 0 and a rigid current collector at x = L. The remaining panels illustrate the corresponding particle-scale states during a single lithiation-delithiation cycle where an initial stress-free state, a lithiated state with constrained expansion and plastic compaction, and a delithiated state with retained eigenstrain and residual stress. In the upper-left panel, the condition at x = 0 denotes the traction-free boundary normal to the thickness direction x.

During the lithiation step, Vegard-induced lattice expansion causes individual active material particles to swell. In the constrained cathode microstructure, in-plane deformation is restricted by neighboring particles and by the current collector, preventing free volumetric dilation and generating high compressive internal stresses at particle contacts. Once these stresses exceed the effective yield strength, inelastic densification occurs, creating an irreversible plastic strain. During subsequent delithiation, the chemical strain vanishes as lithium leaves the lattice, but the plastic strain remains as an eigenstrain field. This retained eigenstrain acts as a source term for the residual in-plane stress distribution in the lithium-free state, representing the fundamental mechanism of eigenstrain-driven degradation resolved by the analytical framework.

2.1. Governing Diffusion Equation

The chemo-mechanical behavior of lithium-ion battery electrodes was modeled through a one-dimensional analytical framework that couples lithium diffusion, eigenstrain generation, and stress evolution under cyclic lithiation and delithiation. Lithium insertion is described by Fick’s second law of diffusion as given in Equation (1) where c(x,t) is the local lithium concentration D is diffusion coefficient.

At the electrode surface, x = 0, lithiation is modeled by imposing a constant surface concentration, c(0,t) = cmax, where cmax is the maximum lithium concentration achievable at the electrode surface under the given charging conditions. This Dirichlet boundary condition is chosen to represent a scenario where surface reaction kinetics are assumed to be fast, leading to immediate surface saturation. The inner boundary, x = L, is considered impermeable and is represented by a Neumann boundary condition of zero flux, mathematically expressed as at x = L.

While a closed-form analytical solution for lithium concentration c(x,t) is available for simplified cases, like infinite domains, the coupled nature of this framework necessitates a numerical solution, implemented via the accompanying MATLAB 2024b code, to accurately capture the evolving concentration profiles under specified boundary conditions.

2.2. Strain Decomposition and Constitutive Relations

The insertion of lithium ions into the electrode lattice induces a volumetric expansion, which is quantified as a chemical strain. In the present one-dimensional formulation, attention is restricted to the in-plane chemical strain component, denoted . This strain is assumed to follow Vegard’s law, which provides a widely used linear approximation of the relationship between lithium concentration and lattice expansion. While this approximation is generally valid for the small-strain cathodes considered here, any minor material non-linearities would represent a small source of model uncertainty. The chemical strain is taken to be linearly related to the molar concentration of lithium via the chemical expansion coefficient , which relates the concentration of lithium to the resulting in-plane chemical strain. In this notation, has units of strain per (mol m−3) and quantifies the in-plane lattice strain generated per unit lithium concentration. This diffusion-induced strain acts as an eigenstrain, analogous to thermal strain, and is the primary driver of stress within the electrode. The parameter denotes the partial molar volume, relating volumetric strain to lithium concentration through and therefore has units of (mol−1 m3) and characterizes the volumetric expansion per mole of inserted lithium. In the present notation, the in-plane chemical strain is given in Equation (2).

The total in-plane strain, , formulated in Equation (3), is additively decomposed into its elastic, , plastic, , and chemical, , components. Here, , , , and denote the corresponding in-plane components. The quantity represents the recoverable elastic strain present at any stage of lithiation or delithiation, while and together account for the inelastic deformation induced by lithium insertion. Upon delithiation, vanishes, but remains as an eigenstrain responsible for the internal stress field.

As the model represents a thin-film electrode constrained by a rigid substrate or a particle constrained by its neighbors, as shown in Figure 1, the total macroscopic in-plane strain is assumed to be zero. This represents the limiting case of a very stiff current collector, for which the in-plane deformation of the support is negligible, and the active layer accommodates almost all the misfit strain. For more compliant collectors, the same framework could be extended by relaxing this condition and distributing the misfit strain between the cathode and the support according to their relative in-plane stiffnesses, but this case is not considered here. Under this condition, the elastic, plastic, and chemical contributions in the in-plane direction satisfy . In the scalar notation used throughout, this relation is written as , which expresses the internal balancing of strains that generates the diffusion-induced stress.

In this reduced one-dimensional description, the in-plane normal stress component acting parallel to the electrode surface, , and its associated elastic strain are considered. For notational simplicity, these quantities are denoted by and . Under the plane-stress approximation adopted here, they are related by the uniaxial Hooke’s law as given in Equation (4), where E is the Young’s modulus. Strictly, a thin film that is fully constrained in-plane supports an approximately equi-biaxial in-plane (membrane) stress state, for which the in-plane stresses satisfy , so that the effective biaxial modulus is . Compared to this equi-biaxial case, the uniaxial relation in Equation (4) simply rescales the stress amplitude by the factor and does not affect the spatial distribution or the eigenstrain-memory effects captured by the analytical solution. For the sake of analytical transparency, the simpler uniaxial plane-stress relation is retained throughout.

This intentional simplification is central to the model’s objective to retain the essential physics of diffusion-induced stress generation and plastic flow while remaining analytically tractable. Compared with a fully equi-biaxial, in-plane constrained film, where the in-plane stresses scale with an effective modulus , the present uniaxial relation changes only the overall stress magnitude by a constant factor and does not affect the predicted through-thickness trends or eigenstrain-memory effects. Since Poisson’s ratio does not enter the one-dimensional formulation and is not required as an input parameter, no specific value is imposed. This simplification is considered appropriate for the analysis of small-strain ceramic cathodes such as LMO, ensuring the fundamental chemo-mechanical couplings are captured effectively [26,27]. While a plane-strain condition would offer higher quantitative accuracy, its mathematical complexity would obscure the direct, analytical link between diffusion, plastic deformation, and residual stress, which is the primary focus of this work. The absolute stress values obtained from the uniaxial relation should therefore be interpreted as slightly lower than those that would arise in a fully equi-biaxial, plane-strain description, but the qualitative trends and the fundamental mechanisms of degradation memory revealed by the model remain robust.

2.3. Plastic Flow and Eigenstrain Formation

To represent the path-dependent nature of plasticity under the small-strain kinematics adopted in this work, the stress evolution is solved within an incremental elastic-plastic framework. Crucially, since constrained lithiation generates high compressive stresses, as noted in Section 2.1, the yield condition here represents the threshold for compressive crushing or densification of the electrode microstructure, rather than dislocation-mediated slip typical of metals. While ceramic oxides are brittle in tension, they can sustain significant inelastic deformation under confinement through intergranular friction and rearrangement. This formulation aligns with homogenized mechanical models of battery electrodes, where compressive failure is treated using continuum plasticity theories [49]. In this homogenized description, the plastic strain, , and its retained eigenstrain counterpart should be interpreted as effective measures of grain-scale processes, such as sliding along weak grain boundaries, intergranular cracking, and pore collapse within polycrystalline secondary particles, averaged over a representative volume element of the microstructure. Microstructural heterogeneity therefore enters the model through the spatial variation in plastic strain driven by the diffusion-controlled stress gradient and through the choice of effective yield and fracture strengths that reflect the aggregate response of layered and spinel cathodes. The framework does not resolve individual grains or crack paths. Instead, it captures their net mechanical effect through this continuum eigenstrain field combined with the fracture-aware capping scheme. At each increment, a trial stress is first computed assuming purely elastic behavior. If this trial stress exceeds the material yield strength, , with denoting the yield strength of the electrode material, plastic flow occurs where the stress is returned to the yield surface by capping, , and the irreversible plastic strain, , is updated to maintain equilibrium.

This incremental formulation accurately captures the generation of irreversible strain during lithiation. Upon delithiation chemical strain, , vanishes, whereas the plastic strain, , persists as an eigenstrain field, which generates internal stresses in the lithium-free state.

To represent the mechanical limits of brittle ceramic electrodes and to account for fracture-induced stress relaxation, the residual stress field, with respect to electrode depth, calculated from the permanent plastic strain distribution after full delithiation, was subjected to a fracture-aware capping procedure. The residual stress is initially expressed using Equation (5), where denotes the uncapped residual stress field generated purely by the retained plastic strain

2.4. Fracture-Aware Stress Capping

The model distinguishes between two failure modes based on the stress state. During lithiation, the material is in compression and is assumed to yield plastically. However, during delithiation, the residual stresses are tensile. Although similar in magnitude for some brittle materials, represents the fracture threshold and is physically distinct from the plastic yield limit, . The yield strength, , governs the onset of irreversible plastic deformation, while the fracture strength cap, , represents the limit at which microcracking is assumed to initiate, leading to a reduction in the load-bearing capacity of the material. In this study’s case, they are assigned the same value for simplicity. It is acknowledged that for brittle ceramics like LMO, the tensile fracture strength is typically much lower than the compressive yield strength. This assumption therefore represents a limiting case of an ideally brittle material where irreversible deformation and fracture are assumed to initiate concurrently. Distinguishing between these failure modes is a key area for future model refinement but is beyond the scope of the present analytical framework, which prioritizes a closed-form solution. This simplification prevents the model from capturing distinct plastic and fracture regimes, collapsing them into a single inelastic response. As such, the model is primarily applicable to ideally brittle materials, such as the small-strain ceramic cathodes considered here, where fracture is assumed to initiate concurrently with the onset of significant irreversible deformation.

In regions where the absolute value of initial residual stress, , exceeds the estimated fracture threshold, , a proportional reduction in the plastic strain is applied. This fracture-aware capping scheme is designed to approximate the physical effects of microcrack-induced stress relaxation in a computationally efficient manner. Physically, the proportional reduction in plastic strain represents the phenomenological effect of microcracking, which increases the material’s local compliance and reduces its load-bearing capacity, thereby relaxing the stress state back to the material’s fracture limit. It is important to note that this scheme is not derived from first principles of fracture mechanics and does not account for the energy dissipation associated with crack formation. Rather, it serves as a pragmatic method to ensure the stress state remains physically plausible. The proportional reduction serves as an empirical surrogate for the complex process of microcrack formation. The scheme is therefore not intended as a physically rigorous fracture model while it preserves stress continuity, it is not formally derived from principles of energy consistency. Rather, it serves as a pragmatic method for ensuring that the final stress state remains within the material’s physical load-bearing limits. The reduction is applied conditionally that is only in regions where the residual stress exceeds the fracture threshold is the plastic strain reduced while in all other regions, the strain remains unchanged to prevent any unphysical increase. This conditional, piecewise logic can be expressed compactly by Equation (6), where the revised plastic strain acts as the final eigenstrain, .

The final residual stress is then updated using Equation (7) where denotes the final residual stress field after application of the fracture-aware capping scheme. This proportional reduction mimics stress relief via microcrack formation, enabling the model to approximate fracture-induced relaxation without explicitly resolving crack paths, as would be required in phase-field or finite-element simulations [29,30].

To illustrate this process, consider a point within the electrode where after delithiation, the initial residual stress calculated from Equation (5) is 120 MPa. If the fracture strength cap is 100 MPa, the stress exceeds the limit. The retained plastic strain at that point is proportionally reduced according to Equation (6) to approximately 0.833. The final residual stress is then updated using Equation (7), resulting in 100 MPa, ensuring the stress state remains within the material’s physical limits. This mimics stress relief from microcracking.

2.5. Model Applicability and Limitations

The present formulation assumes isotropic, homogeneous, and isothermal material behavior, together with small-strain kinematics appropriate for ceramic cathodes such as LMO, and negligible in-plane stress gradients, consistent with a one-dimensional approximation across the electrode thickness. At the full-cell scale, these in-plane constraints arise from the combined confinement imposed by adjacent electrode layers, the current collectors, and the cell casing. In the present one-dimensional formulation, this effect is represented by the assumption of zero macroscopic in-plane strain in the active layer, so the current collectors and cell housing are treated as effectively rigid supports. Under this limiting assumption, the stresses predicted by the model should be interpreted as an upper-bound case. The stress magnitudes would be lower in cells with more compliant supports, while the qualitative through-thickness distribution would remain similar.

While these simplifications reduce geometric and constitutive complexity, they retain the essential physics linking lithium diffusion, plastic deformation, and eigenstrain formation. Furthermore, the fracture-aware capping scheme, while computationally efficient, remains an empirical approximation. Future work could replace this with more rigorous phase-field or cohesive zone models to explicitly capture crack evolution. Moreover, these assumptions allow for transparent analytical treatment without sacrificing the model’s ability to capture the primary chemo-mechanical interactions responsible for degradation. Extensions of the framework to account for anisotropic diffusivity, temperature coupling, or heterogeneous composite microstructures are conceptually straightforward and may be pursued in future studies [34,35]. Overall, this analytical framework provides a computationally efficient and physically interpretable approach for connecting irreversible deformation to residual stress evolution in lithium-ion battery electrodes, thereby bridging the gap between purely elastic analytical models and fully numerical, large-scale simulations that incorporate plasticity and fracture.

Although the present framework assumes a planar thin-film geometry, the underlying physics of constrained expansion are directly relevant to composite electrodes. In a composite microstructure, individual active particles are mechanically confined by the polymeric binder network and neighboring particles. This local confinement creates a stress state analogous to the in-plane constraint of a thin film on a rigid substrate. Mechanics modeling of electrode coatings in the literature demonstrates that these interaction forces and constraints are the primary drivers of mechanical instability and decohesion [37]. Therefore, the stress evolution and degradation memory captured by this one-dimensional analytical model serve as a representative unit cell for the local chemo-mechanical behavior of constrained active material within a larger composite architecture.

3. Illustrative Analysis

To demonstrate the functionality of the proposed analytical framework, this section presents an illustrative application. A representative set of parameters for a small-strain ceramic cathode, LMO, is used. The objective is not to provide a definitive analysis of a specific LMO electrode but rather to showcase the method’s capability to quantify stress evolution, model residual stress distributions, and highlight the formation of eigenstrain fields using physically plausible, literature-derived inputs.

All computations were performed using the MATLAB code developed for this study, which is openly available in the accompanying data repository. The code allows users to specify material and geometric parameters, solve the coupled diffusion-mechanical problem, and visualize the resulting lithium concentration, stress, and plastic strain profiles.

3.1. Model Setup and Parameters

A one-dimensional domain of thickness L = 50 × 10−6 m was considered, representing a thin cathode film constrained in-plane; the analytical solution provides the in-plane normal stress component and the associated plastic strain as functions of the through-thickness coordinate x. The initial lithium concentration was assumed to be zero, and lithiation was imposed by a constant surface concentration boundary condition at x = 0, estimated from reported values in the literature [27]. The corresponding diffusion problem was solved for a charging period of 3600 s that is equivalent to a moderate C-rate.

The material and model parameters used in the calculations are summarized in Table 1. The values for the material properties were selected from established literature for spinel-type LMO or comparable ceramic cathodes. Specifically, the lithium diffusivity [50,51] and Young’s modulus [27] were obtained from the cited studies, and the in-plane chemical expansion coefficient was calibrated from the lattice expansion data reported for LMO [27]. For the maximum lithium concentration cmax used here, this choice gives an in-plane chemical strain ≈ 0.026 (≈2.6% per axis). Under the assumption of isotropic Vegard expansion, the corresponding volumetric strain is ΔV/V ≈ 3 ≈ 0.078, i.e., a total volumetric expansion of approximately 7–8%, consistent with the lattice parameter change from ~8.03 Å to ~8.24 Å reported for LMO [52]. For such modest lattice changes, the difference between a small-strain kinematic description and a full finite-strain formulation is minor compared with the uncertainties in material properties such as diffusivity, elastic modulus, and yield strength. Consequently, the small-strain approximation is not expected to introduce a significant error in the predicted stress evolution for LMO. By contrast, chemistries that undergo substantially larger lattice changes during cycling would require an extension of the present framework to finite-strain kinematics. The yield and fracture strengths were chosen to represent typical stress scales associated with fracture in LMO and related oxide cathodes [53,54]. It is important to note that while nanoindentation measurements indicate intrinsic hardness values in the GPa range for oxide cathode materials [54], the effective yield strength of polycrystalline secondary particles is significantly lower (~100 MPa). Accordingly, the fracture-strength cap equals to 100 MPa adopted here should be interpreted as representing the order of magnitude of crack-initiation stresses for sintered LMO and related oxide cathodes, rather than a precise fit to a particular experiment.

Table 1.

Material and model parameters used in the analytical framework for lithiation-induced stress and residual stress analysis.

This lower value governs the mechanical response of the porous aggregate, where degradation is dominated by intergranular fracture and sliding along weak grain boundaries rather than intragranular deformation. Within the present continuum formulation, these intergranular processes manifest as irreversible compaction and stiffness loss, which are encoded in the plastic strain during lithiation and subsequently in the eigenstrain field that drives the residual stress state after delithiation. The specific assumption of equal yield and fracture strengths is a deliberate choice for this illustrative case, representing the limiting behavior of an ideally brittle material. In this framework, it implies that the onset of irreversible deformation occurs concurrently with fracture-induced stress relaxation, which is a reasonable approximation for many ceramic systems and is central to the analytical tractability of the fracture-aware capping scheme.

3.2. Stress Evolution and Residual State

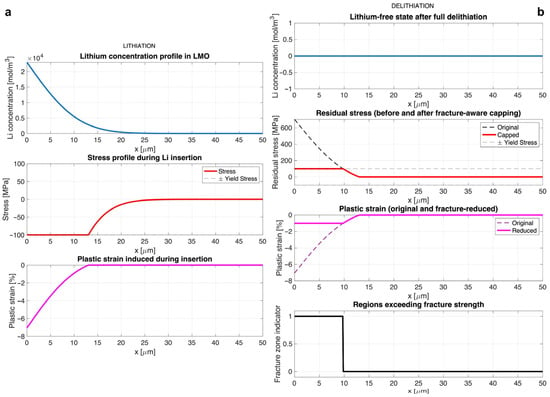

Figure 2a illustrates the distribution of lithium concentration, stress, and plastic strain across the electrode thickness at the end of the lithiation step. The concentration profile exhibits a characteristic diffusion gradient, with the highest lithium content near the surface, where = 0, and a gradual decrease toward the interior. This non-uniform chemical expansion produces a compressive stress field due to mechanical constraint.

Figure 2.

(a) State at the end of lithiation (left column). Top: Lithium concentration profile across the electrode thickness, showing a high concentration at the surface that decays into the interior. Middle: Stress profile showing compressive stress that exceeds the compressive yield limit (−100 MPa) near the surface. Bottom: Resulting plastic strain induced in the yielded region near the surface. (b) Residual state after full delithiation (right column). Top: Lithium concentration is zero across the electrode. Top Middle: Residual stress profile before (dashed line) and after (solid line) the fracture-aware capping is applied. Bottom Middle: The original irreversible plastic strain (dashed line) and the reduced plastic strain (solid line) after capping. Bottom: A binary indicator for regions where the initial residual stress exceeded the fracture strength cap.

In regions where the magnitude of compressive stress exceeds the compressive yield limit (−100 MPa), plastic flow is activated. The stress in these zones is capped at yield strength, , according to the elastic-plastic constitutive law, while inner regions remain elastic. The localized plastic strain , shown in Figure 2a, represents the irreversible deformation that will persist after delithiation and thus acts as the eigenstrain source for residual stress formation.

Figure 2b shows the residual stress and retained plastic strain distributions following complete delithiation. As lithium is removed, the chemical strain, , vanishes, but the plastic strain remains. This results in a tensile-compressive residual stress gradient, with high tensile stress near the surface where compressive yielding occurred, balanced by compressive stress toward the interior where deformation remained elastic. The magnitude of residual stresses is limited by the fracture-aware capping scheme as described by Equations (6) and (7), which approximates microcrack-induced relaxation by proportionally reducing the effective plastic strain. For the parameter values in Table 1, the peak plastic strain at the electrode surface in Figure 2 is of order 1 × 10−2 (about 1%). For a 50 µm-thick film, this corresponds to a sub-micrometer in-plane compaction of the surface layer (≈0.5 µm), which is small at the macroscopic scale but sufficient to generate the tensile–compressive residual stress gradients shown in Figure 2b. In the capped residual state, the corresponding peak tensile stress at the surface is limited to approximately 100 MPa by the fracture-strength threshold, . This stress level is comparable to the magnitudes associated with fracture and crack formation in sintered LMO and related oxide cathodes discussed in the literature [53,54], supporting the plausibility of the predicted residual stress scale.

3.3. Discussion of Model Insights and Scope

This single-cycle analysis isolates the mechanisms responsible for eigenstrain formation and associated stress redistribution. This focus is intentional, as the stress and strain state at the end of the first cycle establishes the initial conditions for all subsequent degradation. The framework captures how irreversible compressive deformation during lithiation translates into tensile residual stress upon delithiation, a key contributor to crack initiation in subsequent cycles. While multi-cycle degradation, SEI evolution, or creep effects are beyond the present scope, the analytical transparency of this model provides a clear mechanistic foundation for such future extensions. For example, the framework is ideally suited for an iterative approach to model cyclic degradation where the final retained plastic strain, , from the end of one cycle would serve as the initial state for the next, allowing for the explicit simulation of how residual eigenstrain and degradation memory accumulate over time. Residual fields calculated here would serve as the starting point for the next cycle.

By adjusting input parameters in the MATLAB script, users can explore how electrode thickness, diffusivity, yield strength, or fracture limit influence the magnitude and spatial distribution of both transient and residual stresses. This feature makes the framework a practical and interpretable tool for understanding and comparing the mechanical stability of candidate electrode materials. In this sense, the primary utility of the approach is twofold: it provides a mechanistically transparent description of eigenstrain-driven degradation, and, because each solution is obtained at negligible computational cost, it enables rapid screening of how variations in key material and design parameters influence residual stress gradients before resorting to more complex numerical models.

Direct quantitative benchmarking of the present one-dimensional analytical solution against a specific operando dataset, such as wafer-curvature or X-ray diffraction measurements, is not attempted here. The illustrative calculations are performed for a generic thin-film cathode using literature-averaged material properties and idealized boundary conditions, rather than for a particular cell architecture. A rigorous fit to any given experiment would require re-parameterizing the model for that system and incorporating additional cell-scale effects such as current-collector compliance, multilayer stacking, and SEI growth, which would detract from the analytical focus of this study. Instead, the model’s principal predictions are assessed at a qualitative level and are consistent with experimental observations reported in the literature [55,56].

The key outcome, that irreversible plastic deformation during lithiation generates a tensile-compressive residual stress field upon delithiation, is well supported by in situ measurements. Wafer curvature studies on thin-film electrodes [31] have revealed the transition from compressive stress during lithiation to residual tensile stress after delithiation, driving mechanical failure. Likewise, Digital Image Correlation and Raman spectroscopy analyses [32,33] have mapped non-uniform strain fields that persist after cycling, confirming the existence of eigenstrains and the concept of a path-dependent degradation memory. The fracture-aware capping scheme proposed here, although an approximation, aligns conceptually with experimentally observed microcracking that relieves stress during cycling. Therefore, the present analytical framework provides a physically grounded and experimentally consistent basis for understanding the chemo-mechanical degradation of lithium-ion electrodes.

The magnitude of plastic strain predicted here, of order 10−3–10−2, is consistent with the non-uniform deformation and crack formation resolved in X-ray tomography, digital image correlation and related imaging studies of Li-ion battery electrodes [24,25,31,32,33], where comparable levels of inelastic strain give rise to surface roughening and microcracking rather than gross macroscopic distortion. For the representative parameter set in Table 1, the capped residual stress profiles satisfy , so that the peak tensile residual stress at the surface is of order 102 MPa. Interpreted as an approximation to an equi-biaxial constraint (see Section 2.2), this implies an upper bound of at most a factor higher, i.e., ≲(1.3–1.4) × 102 MPa for typical oxide-ceramic Poisson’s ratios. These bounds are comparable to the stress levels associated with fracture and crack initiation in sintered LMO and related spinel cathodes discussed in the literature [53,54], indicating that the residual stresses predicted by the model are experimentally plausible.

The illustrative calculations shown here are restricted to a single lithiation-delithiation cycle while the eigenstrain-based formulation naturally extends to multiple cycles. In an iterative implementation, the retained plastic strain and capped eigenstrain after each cycle would serve as the initial condition for the next, leading to a progressive build-up and eventual saturation of the residual tensile stress near the surface as microcracking limits further stress growth. These trends mirror operando observations from wafer-curvature measurements and X-ray diffraction stress analyses, which report a cycle-dependent evolution of average film stress and non-recoverable lattice strain in oxide cathodes [31,40]. Thus, while explicit multi-cycle simulations are deferred to future work, the present framework provides a mechanistic basis for interpreting the path-dependent residual stress histories measured in these experiments.

Although directly resolving the full through-thickness stress profile experimentally remains difficult, several emerging operando probes can provide partial validation of the model. High-energy X-ray microdiffraction and related synchrotron techniques can measure lattice strains in selected sub-surface layers, while neutron Bragg-edge imaging yields path-averaged strain along the beam direction in relatively thick electrodes. In addition, stress-sensitive Raman mapping provides near-surface estimates of residual stress with high lateral resolution. When interpreted through the lens of the present one-dimensional eigenstrain framework, such measurements could be used to test specific predictions of the model, for example, the sign change between surface tension and interior compression, or the depth scale over which the high-stress region extends, even if the full stress gradient cannot be measured directly.

3.4. Parametric Study

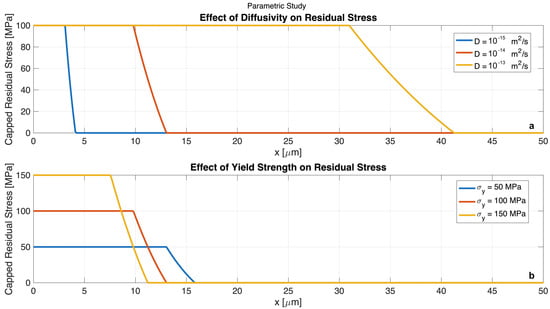

To demonstrate the framework’s utility in exploring the influence of material properties on mechanical degradation, a parametric study was conducted. The model was used to investigate how variations in two key parameters, lithium diffusivity, D, and material yield strength, , affect the resulting residual stress profile. The magnitude and spatial distribution of this residual tensile stress are primary indicators of the driving force for crack initiation and propagation in subsequent cycles. The results are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Results of the parametric study showing the influence of key material properties on the capped residual stress profile after a single lithiation-delithiation cycle. (a) Effect of lithium diffusivity on residual stress, with yield strength held constant at 100 MPa. The plot shows that higher diffusivity leads to a deeper penetration of the high-stress region into the electrode. (b) Effect of yield strength on residual stress, with diffusivity held constant at 10−14 m2/s. The plot demonstrates that higher yield strength effectively confines the region of high residual stress to a shallower depth near the electrode surface. Together, these results highlight key material design principles for enhancing the mechanical robustness of battery electrodes.

Figure 3a illustrates the effect of varying lithium diffusivity while holding the yield strength constant at 100 MPa. The results show a clear trend where, as diffusivity increases, the depth of the high-stress region penetrates further into the electrode. For slow diffusion, D = 10−15 m2/s, the irreversible deformation and resulting residual stress are confined to a shallow surface layer of approximately 4 µm. In contrast, for fast diffusion, D = 10−13 m2/s, the higher ionic mobility allows lithium to penetrate deeper within the fixed charging time, causing a much wider zone, over 32 µm, to yield. This demonstrates that while high diffusivity is beneficial for electrochemical power performance, it can be detrimental to mechanical integrity by increasing the volume of material susceptible to damage.

Figure 3b shows the impact of varying the electrode material’s yield strength while keeping diffusivity constant. The analysis reveals that a higher yield strength is highly effective at mitigating mechanical damage. While the peak residual stress is capped by the yield strength itself, a stronger material, = 150 MPa, possesses a larger elastic window and can accommodate more diffusion-induced stress without permanent deformation. As a result, plastic yielding is confined to a much shallower region near the surface, less than 10 µm deep. Conversely, a weaker material, = 50 MPa, yields more easily, leading to a deeper zone of irreversible strain and residual stress. These findings provide a clear directive for materials design. Enhancing the mechanical strength of electrode materials is a critical strategy for limiting the extent of irreversible deformation and improving the battery’s cycle life.

In the present small-strain formulation, the thickness of the yielded (plastic) zone is controlled primarily by the diffusion length scale, , and the yield strength, because yielding is triggered by the condition . For the modest strain levels predicted here, with peak plastic strain of order 1 × 10−2 at the surface shown in Figure 2, the difference between a small-strain and a finite-strain elastic–plastic description would change the local stress magnitude by only a few percent and therefore has a negligible impact on the computed plastic-zone thickness. Consequently, the reported depths of the yielded region, from a few micrometers up to several tens of micrometers, depending on the diffusion coefficient, D, and yield strength, , should be viewed as robust with respect to the kinematic choice for LMO-like small-strain cathodes. For chemistries exhibiting much larger lattice expansions, a finite-strain extension of the framework would be required and could modestly broaden the predicted plastic region, but such cases lie beyond the scope of the present small-strain LMO case study.

4. Conclusions

This study has presented a chemo-mechanical analytical framework that captures the formation of residual stresses and eigenstrains in lithium-ion battery electrodes by coupling one-dimensional diffusion with elastic-plastic constitutive behavior. The model provides closed-form mechanical relations linking lithium concentration gradients to stress evolution and residual stress formation, thereby establishing a transparent mechanistic link between irreversible deformation and path-dependent mechanical degradation.

The results show that non-uniform lithium concentration during lithiation induces compressive stresses near the electrode surface, which, upon exceeding the yield strength, generates irreversible plastic deformation. After delithiation, the chemical strain vanishes, while the retained plastic strain acts as an eigenstrain, producing a damaging tensile stress state at the electrode surface balanced by a compressive core. The implementation of a fracture-aware capping scheme ensures that residual stresses remain within the material’s mechanical limits by approximating microcrack-induced relaxation through proportional reduction in plastic strain. This simple yet physically grounded treatment enables a computationally efficient approximation of fracture effects without resorting to complex finite-element or phase-field simulations. The resulting combination of analytical transparency and low computational cost makes the framework most useful both as a mechanistic lens on chemo-mechanical degradation and as a front-end tool for rapid exploration of material properties and electrode design choices in systems where chemo-mechanical strains are moderate.

Direct experimental measurement of through-thickness stress gradients in cathode materials remains a significant challenge. Emerging operando techniques, including high-energy X-ray microdiffraction, neutron Bragg-edge imaging, and stress-sensitive Raman mapping, offer depth- or path-averaged measurements of lattice strain that could be combined with the present analytical framework to partially validate its predicted residual stress gradients, even when full three-dimensional stress fields are not directly accessible. Therefore, physically grounded analytical models, like the one presented here, are essential for providing insights into the internal stress states that govern mechanical degradation. The predictions are qualitatively consistent with established experimental observations, such as the evolution of average stress measured by wafer curvature and the location of cracking observed in post-mortem microscopy [57]. They are also consistent with operando X-ray diffraction and curvature studies that report progressive accumulation of non-recoverable lattice strain and residual stress with cycling in oxide cathodes [31,40].

The present model intentionally focuses on small-strain ceramic cathodes like LMO, for which volumetric changes are moderate and analytical treatment remains valid. While multi-cycle degradation, SEI evolution, and damage accumulation are not included, the framework provides a mechanistically transparent foundation for future extensions incorporating cyclic hardening/softening, viscoplasticity, or coupled electrochemical-mechanical fatigue. The analytical relations derived here can be readily adapted to other small-strain material systems and geometries, serving as a benchmark for validating numerical simulations and guiding the design of mechanically robust electrode systems where volumetric changes remain moderate. Furthermore, the framework’s fundamental approach can be extended to address the unique chemo-mechanical challenges in next-generation systems, such as all-solid-state batteries or composite electrodes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The MATLAB code developed for solving the case study and implementing the proposed analytical model is openly available at https://doi.org/10.17632/8bg5dn24m2.1 in Mendeley Data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Broussely, M.; Biensan, P.; Simon, B. Lithium insertion into host materials: The key to success for Li ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 1999, 45, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J. Lithium insertion/extraction mechanism in alloy anodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Shen, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Reversible lithiation-delithiation chemistry in cobalt based metal organic framework nanowire electrode engineering for advanced lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 15411–15419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazioli, D.; Magri, M.; Salvadori, A. Computational modeling of Li-ion batteries. Comput. Mech. 2016, 58, 889–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Luan, W.; Chen, H.; Huo, L.; Wang, M.; Tu, S.T. A Review of Multiscale Mechanical Failures in Lithium-Ion Batteries: Implications for Performance, Lifetime and Safety. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, M.T.; Xia, S.; Zhu, T. The mechanics of large-volume-change transformations in high-capacity battery materials. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2016, 9, 480–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, T.; Nusko, D.; Pitta Bauermann, L.; Vetter, M.; Schäfer, M.; Holly, C. Methods for Quantifying Expansion in Lithium-Ion Battery Cells Resulting from Cycling: A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chao, Y.; Li, M.; Xiao, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, K.; Cui, X.; Xu, G.; Li, L.; Yang, C.; et al. A Review of Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) and Dendrite Formation in Lithium Batteries; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Kumar, R.; Xiao, X.; Sheldon, B.W.; Gao, H. Failure progression in the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) on silicon electrodes. Nano Energy 2020, 68, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, R.D.; Bernardi, D.M. Modeling Solid-Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) Fracture: Coupled Mechani-cal/Chemical Degradation of the Lithium Ion Battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A461–A474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jia, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.G.; Xu, W. Recent Progress in Understanding Solid Electrolyte Interphase on Lithium Metal Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xin, F.; Whittingham, M.S.; Liaw, B. Lithium inventory tracking as a non-destructive battery evaluation and monitoring method. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Seok, C.; Tao, L.; Shi, C.; Yao, J.; Xia, D.; Promi, A.T.; Meyer, K.; Yang, D.; Liu, S.; et al. Mitigating Cyclable Li-Ion Inventory Loss in Full Cells with Mn-Rich Disordered Rocksalt Cathodes. Adv. Energy Mater 2025, 15, 2501285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornheim, A.; O’Hanlon, D.C. What do Coulombic Efficiency and Capacity Retention Truly Measure? A Deep Dive into Cyclable Lithium Inventory, Limitation Type, and Redox Side Reactions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Ren, D.; Liao, J.; Song, Y.; Liang, H.; Wang, A.; He, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; et al. Revisiting the initial irreversible capacity loss of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2 cathode material batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 50, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Duan, Q.; Qi, K.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q. Capacity fading mechanisms and state of health prediction of commercial lithium-ion battery in total lifespan. J. Energy Storage 2022, 46, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, S.; Delaille, A.; Gualous, H.; Gyan, P.; Revel, R.; Bernard, J.; Redondo-Iglesias, E.; Peter, J. Calendar aging of commercial graphite/LiFePO4 cell—Predicting capacity fade under time dependent storage conditions. J. Power Sources 2014, 255, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraheem, R.; Strange, C.; dos Reis, G. Capacity and Internal Resistance of lithium-ion batteries: Full degradation curve prediction from Voltage response at constant Current at discharge. J. Power Sources 2023, 556, 232477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroe, D.I.; Swierczynski, M.; Kær, S.K.; Teodorescu, R. Degradation Behavior of Lithium-Ion Batteries During Calendar Ageing—The Case of the Internal Resistance Increase. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, J.S.; O’Kane, S.; Prosser, R.; Kirkaldy, N.D.; Patel, A.N.; Hales, A.; Ghosh, A.; Ai, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Offer, Lithium ion battery degradation: What you need to know. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 8200–8221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, R. Recent advances in the interfacial stability, design and in situ characterization of garnet-type Li7La3Zr2O12 solid-state electrolytes based lithium metal batteries. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 13280–13290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Kim, J.; Bae, Y.S.; Moon, J. Predictive modeling of lithium-ion battery degradation: Incorporating SEI layer growth and mechanical stress factors. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2024, 38, 6157–6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, M.; Ondrejka, P.; Mikolasek, M. Comprehensive Degradation Analysis of NCA Li-Ion Batteries via Methods of Electrochemical Characterisation for Various Stress-Inducing Scenarios. Batteries 2023, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A.H.; Goldin, G.M.; Barnett, S.A.; Zhu, H.; Kee, R.J. Effects of three-dimensional cathode microstructure on the performance of lithium-ion battery cathodes. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 88, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, J.P.; Jha, G.; Youn, D.H.; Ziegler, J.M.; Andoni, I.; Choi, E.J.; Heller, A.; Dunn, B.S.; Weiss, P.S.; Penner, R.M.; et al. Electrode Degradation in Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1243–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.; Newman, J. Stress generation and fracture in lithium insertion materials. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2006, 10, 293–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shyy, W.; Marie Sastry, A. Numerical Simulation of Intercalation-Induced Stress in Li-Ion Battery Electrode Particles. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, A910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, A.F.; Guduru, P.R.; Sethuraman, V.A. A finite strain model of stress, diffusion, plastic flow, and electro-chemical reactions in a lithium-ion half-cell. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2011, 59, 804–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal, H.; Miehe, C. Computational electro-chemo-mechanics of lithium-ion battery electrodes at finite strains. Comput. Mech. 2015, 55, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xie, Y.; Chen, H.; Luan, W. Numerical analysis of the cyclic mechanical damage of Li-ion battery electrode and experimental validation. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 142, 105915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadimpalli, S.P.V.; Sethuraman, V.A.; Bucci, G.; Srinivasan, V.; Bower, A.F.; Guduru, P.R. On Plastic Deformation and Fracture in Si Films during Electrochemical Lithiation/Delithiation Cycling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, A1885–A1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Song, H.; Guo, J.; Kang, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Q. In situ measurement of rate-dependent strain/stress evolution and mechanism exploration in graphene electrodes during electrochemical process. Carbon N. Y. 2019, 144, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Pecht, M. In situ stress measurement techniques on li-ion battery electrodes: A review. Energies 2017, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Lu, W. A battery model that fully couples mechanics and electrochemistry at both particle and electrode levels by incorporation of particle interaction. J. Power Sources 2017, 360, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.A.; Mendoza, H.; Brunini, V.E.; Trembacki, B.L.; Noble, D.R.; Grillet, A.M. Insights into lithium-ion battery degradation and safety mechanisms from mesoscale simulations using experimentally reconstructed mesostructures. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2016, 13, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, F.; Korsunsky, A.M. OxDEM: Discrete element method based on strain energy formulation. Adv. Powder Technol. 2025, 36, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, G.; Talamini, B.; Renuka Balakrishna, A.; Chiang, Y.M.; Carter, W.C. Mechanical instability of electrode-electrolyte interfaces in solid-state batteries. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018, 2, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yang, Y.; Yin, F.; Liu, P.; Cloetens, P.; Liu, Y.; Lin, F.; Zhao, K. Heterogeneous damage in Li-ion batteries: Experimental analysis and theoretical modeling. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2019, 129, 160–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Sui, T.; Ying, S.; Li, L.; Lu, L.; Korsunsky, A.M. Nano-structural changes in Li-ion battery cathodes during cycling revealed by FIB-SEM serial sectioning tomography. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2015, 3, 18171–18179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano Brandt, L.; Marie, J.J.; Moxham, T.; Förstermann, D.P.; Salvati, E.; Besnard, C.; Papadaki, C.; Wang, Z.; Bruce, P.G.; Korsunsky, A.M. Synchrotron X-ray quantitative evaluation of transient deformation and damage phenomena in a single nickel-rich cathode particle. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 3556–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsunsky, A.M.; Sui, T.; Song, B. Explicit formulae for the internal stress in spherical particles of active material within lithium ion battery cathodes during charging and discharging. Mater. Des. 2015, 69, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Pharr, M.; Cai, S.; Vlassak, J.J.; Suo, Z. Large plastic deformation in high-capacity lithium-ion batteries caused by charge and discharge. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, s226–s235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Zheng, B.; Yang, F.; Lu, D. An analytical model for lithiation-induced concurrent plastic flow and phase transformation in a cylindrical silicon electrode. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2020, 202, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Fan, F.; Liang, W.; Guo, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, S. A chemo-mechanical model of lithiation in silicon. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2014, 70, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Sui, T.; Song, B.; Zheng, H.; Lu, L.; Korsunsky, A.M. On the fragmentation of active material secondary par-ticles in lithium ion battery cathodes induced by charge cycling. Extreme. Mech. Lett. 2016, 9, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangrós Giménez, C.; Finke, B.; Schilde, C.; Froböse, L.; Kwade, A. Numerical simulation of the behavior of lithiumion battery electrodes during the calendaring process via the discrete element method. Powder Technol. 2019, 349, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, T. Micromechanics of Defects in Solids; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Korsunsky, A.M. A Teaching Essay on Residual Stresses and Eigenstrains, 1st ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Li, W.; Wierzbicki, T.; Xia, Y.; Harding, J. Deformation and failure of lithium-ion batteries treated as a discrete layered structure. Int. J. Plast 2019, 121, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwata, N.; Nakane, M.; Miyazaki, T.; Mitsuishi, K.; Kawamura, J. Lithium diffusion coefficient in LiMn2O4 thin films measured by secondary ion mass spectrometry with ion-exchange method. Solid State Ion. 2018, 320, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Huang, B.; He, Y. Determination of Li+ solid diffusion coefficient in LiMn2O4 by CITT. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2005, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.C. Preparation of a new crystal form of manganese dioxide: λ-MnO2. J. Solid State Chem. 1981, 39, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.; Newman, J. A Mathematical Model of Stress Generation and Fracture in Lithium Manganese Ox-ide. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Sun, H.; de Vasconcelos, L.S.; Zhao, K. Mechanical and Structural Degradation of LiNixMnyCozO2 Cath-ode in Li-Ion Batteries: An Experimental Study. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A3333–A3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, N.S.; Park, K.Y.; Hersam, M.C. Characterizing and Mitigating Chemomechanical Degradation in High-Energy Lithium-Ion Battery Cathode Materials. Acc. Mater. Res. 2022, 3, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slautin, B.; Alikin, D.; Rosato, D.; Pelegov, D.; Shur, V.; Kholkin, A. Local study of lithiation and degradation paths in limn2o4 battery cathodes: Confocal raman microscopy approach. Batteries 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, V.A.; Chon, M.J.; Shimshak, M.; Srinivasan, V.; Guduru, P.R. In situ measurements of stress evolution in silicon thin films during electrochemical lithiation and delithiation. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 5062–5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).