This chapter presents and analyzes in detail the results of the experiments carried out to evaluate the produced slurry in terms of the quality parameters of rheology and particle size distribution, and to clean the anode slurry in the twin-screw extruder. Emphasis is placed on the investigation of various parameters and their influence on the effectiveness of the cleaning processes. The relevant cleaning factors are summarized by the Sinner circle, which includes the chemical cleaning medium, mechanical kinetics, temperature and cleaning time. Images are also used to illustrate the most significant differences. Finally, electrochemical analysis of cross-contamination during cycling concludes the investigation of the process chain for manufacturing lithium-ion batteries.

3.1. Quality Parameters of Slurry

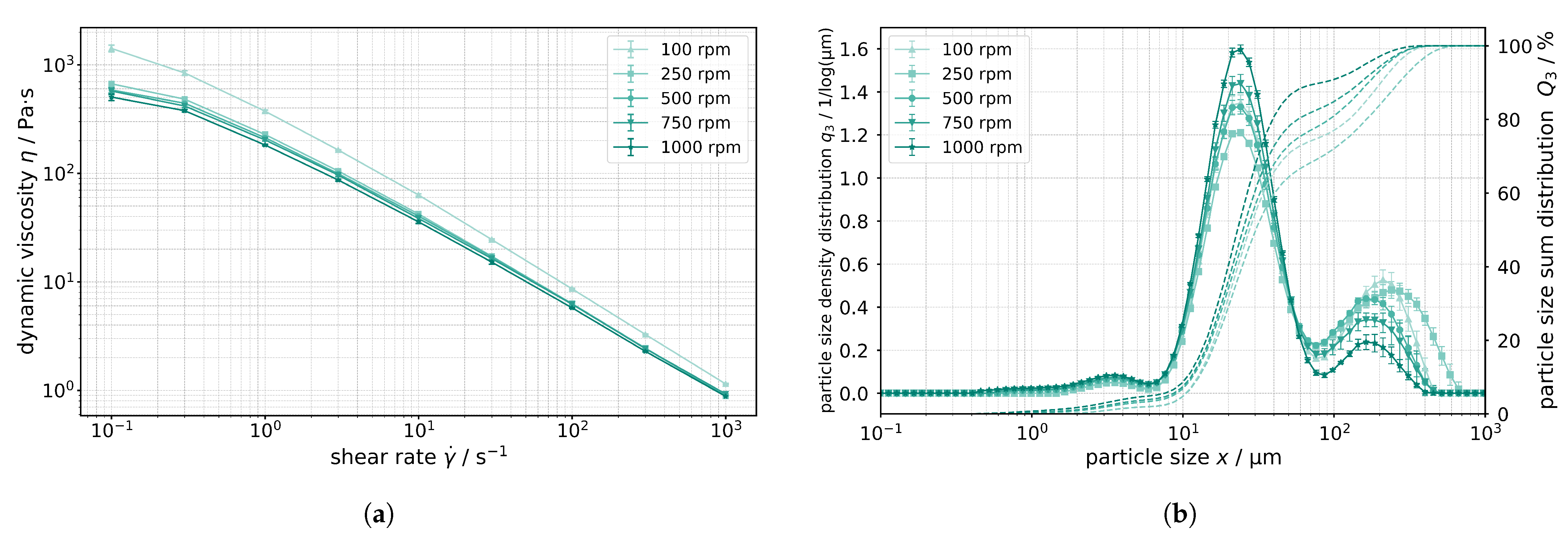

The quality of the produced anode slurries was determined by measuring viscosity and particle size distribution (PSD). Slurry quality is important, because it will influence the subsequent cleaning step. The viscosity curves shown in

Figure 3a describe the dependence of dynamic viscosity on shear rate for different twin screw speeds. Five different screw speeds were chosen, ranging from 100 rpm to 1000 rpm. All curves confirm a structurally viscous behaviour, as the viscosity of the slurry decreases with increasing shear rate at all speeds studied. This behavior suggests that the structure of the anode slurry is more affected at higher speeds in the extruder, leading to a reduction in viscosity. The arrangement of the particles and the interactions within the slurry are affected by the shear forces, resulting in the formation of a different network between the particles and the binder [

36].

On the other hand,

Figure 3b shows the particle size distribution of the anode slurry as a function of the respective particle size for different screw speeds from 100 rpm to 1000 rpm. The distribution shows three distinct peaks indicating the presence of different particle classes. The first peak, with particle sizes between 1 μm and 10 μm, represents the smaller aggregates resulting from the dispersion of the carbon black. These particles remain relatively stable even at higher speeds, indicating that they are highly agglomerated or aggregated and difficult to break up. The second peak at about 20 μm largely reflects the graphite content and the third peak at about 150 μm to 200μm shows the presence of larger agglomerates formed by the aggregation of several aggregates. The height and width of this peak decrease with increasing speed, indicating that these larger agglomerates are broken up at higher shear forces in the extruder. The decrease in particle size distribution in the region of the larger agglomerates explains the decrease in viscosity as described in the

Figure 3a.

A significantly more homogeneous distribution can be achieved by implementing a pretreatment process before homogenisation of the powders that will be inserted into the extruder chamber by the feeder, or by optimizing the process parameters. The residence time, and therefore the resulting material, can be adjusted by reducing the mass flow rate and increasing the energy input [

16,

37,

38]. This can be achieved by using a different screw configuration or a higher extruder speed, for example [

14]. However, the focus here was on investigating the corresponding cleaning process, so the same process parameters were always used for reproducibility purposes. Furthermore, it should be noted that viscosity is largely independent of PSD because the adsorption of CMC molecules significantly affects viscosity, which dominates and decides the consecutive cleaning kinetics [

39].

At lower screw speeds, the slurry remains more inhomogeneous as the larger agglomerates settle more quickly. At higher screw speeds, the slurry becomes more homogeneous and stable as the agglomerates are broken up, which can be advantageous for processing. In summary,

Figure 3b shows that higher screw speeds in the extruder result in better dispersion of the particles and breaking up of larger agglomerates, which in turn helps to reduce the viscosity and improve the processability of the anode slurry. The resulting quality characteristics have a critical impact on cleaning, which is highly dependent on the composition and initial viscosity of the slurry. For subsequent cleaning, the same recipe with the same solids content was used for reproducibility. The extruder throughput for production was also set to be constant at 1 kg/h of slurry and the screw speed was 750 rpm.

In order to gain a better understanding of the material being processed for consecutive cleaning, the corresponding electrode was subjected to optical examination via SEM based on the selected slurry formulation. A specific location was analyzed for different size scales, which are shown in

Figure 4. The active material graphite and the conductive carbon black binder network are clearly visible in all images. The SEM micrographs at different magnifications reveal the characteristic microstructure of the graphite-based anode. At low magnification, large platelet-like graphite particles with irregular edges can be clearly identified. The particles are relatively densely packed but still exhibit interparticle voids. With higher magnification, the layered morphology of the graphite becomes more apparent, and the interfaces between adjacent particles are visible.

In the subsequent images, the surface topography of the graphite platelets is shown in greater detail. Sharp edges, steps, and fracture planes highlight the crystalline nature of the graphite domains. In addition, fine particulate material can be observed in the pores and on the surfaces of the larger platelets, which likely corresponds to conductive additives and binder residues. These features form a percolating network between the graphite particles and contribute to the electrical conductivity of the electrode.

Furthermore, the electrical resistivity of the electrodes was analyzed. The measurement yielded a composite volume resistivity of 0.181 ± 0.07 Ω cm, an interface resistance of 0.0347 ± 0.0046 Ω cm2, and a composite surface resistivity of 0.00077 ± 0.00007 Ω cm2. Overall, the SEM analysis demonstrates a heterogeneous but interconnected microstructure consisting of graphite as the active material, with smaller particles and binder phases distributed along the particle boundaries. The hierarchical porosity visible at different length scales indicates pathways for electrolyte infiltration while simultaneously providing sufficient electrical connectivity through the carbonaceous binder network.

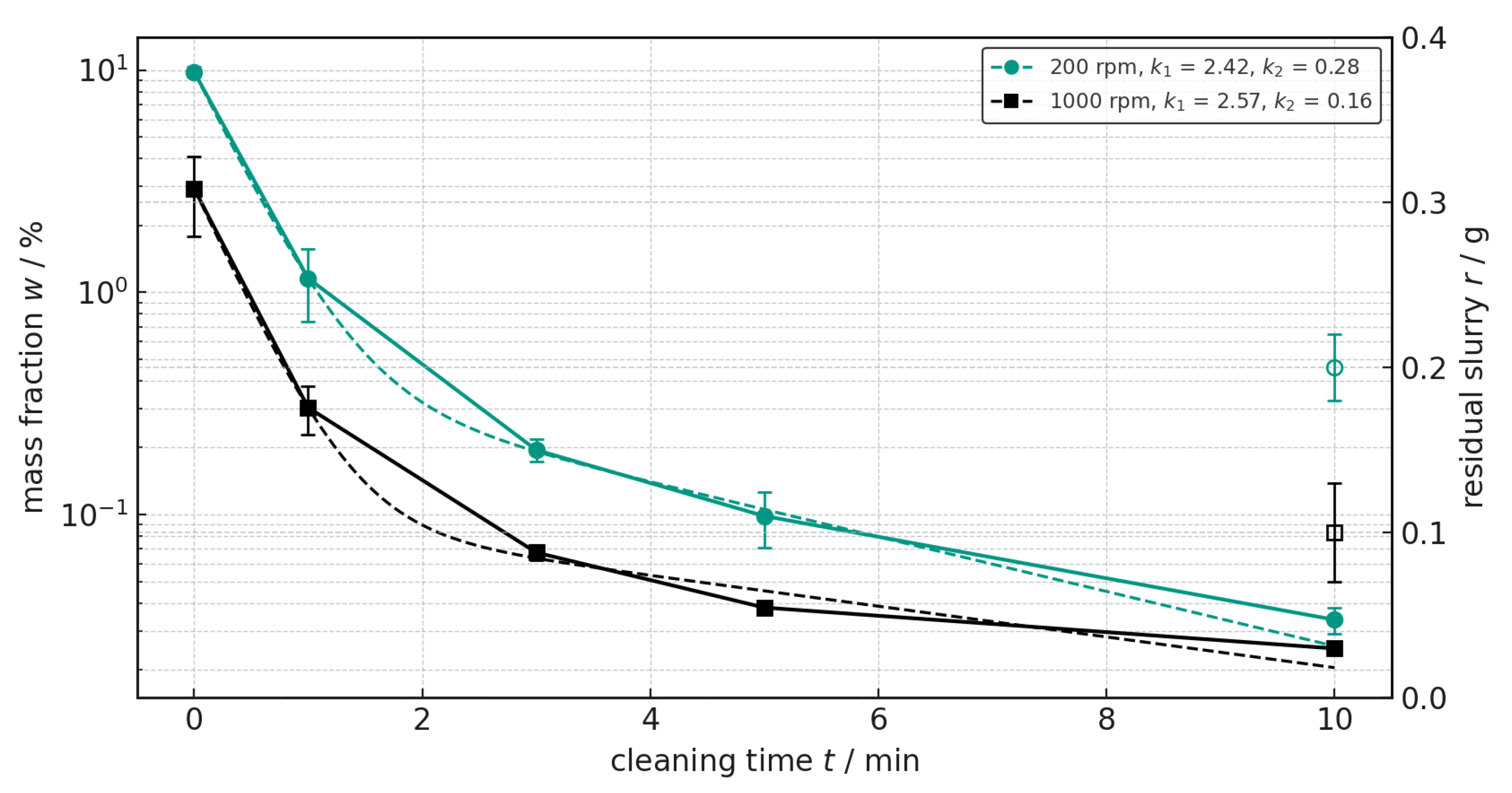

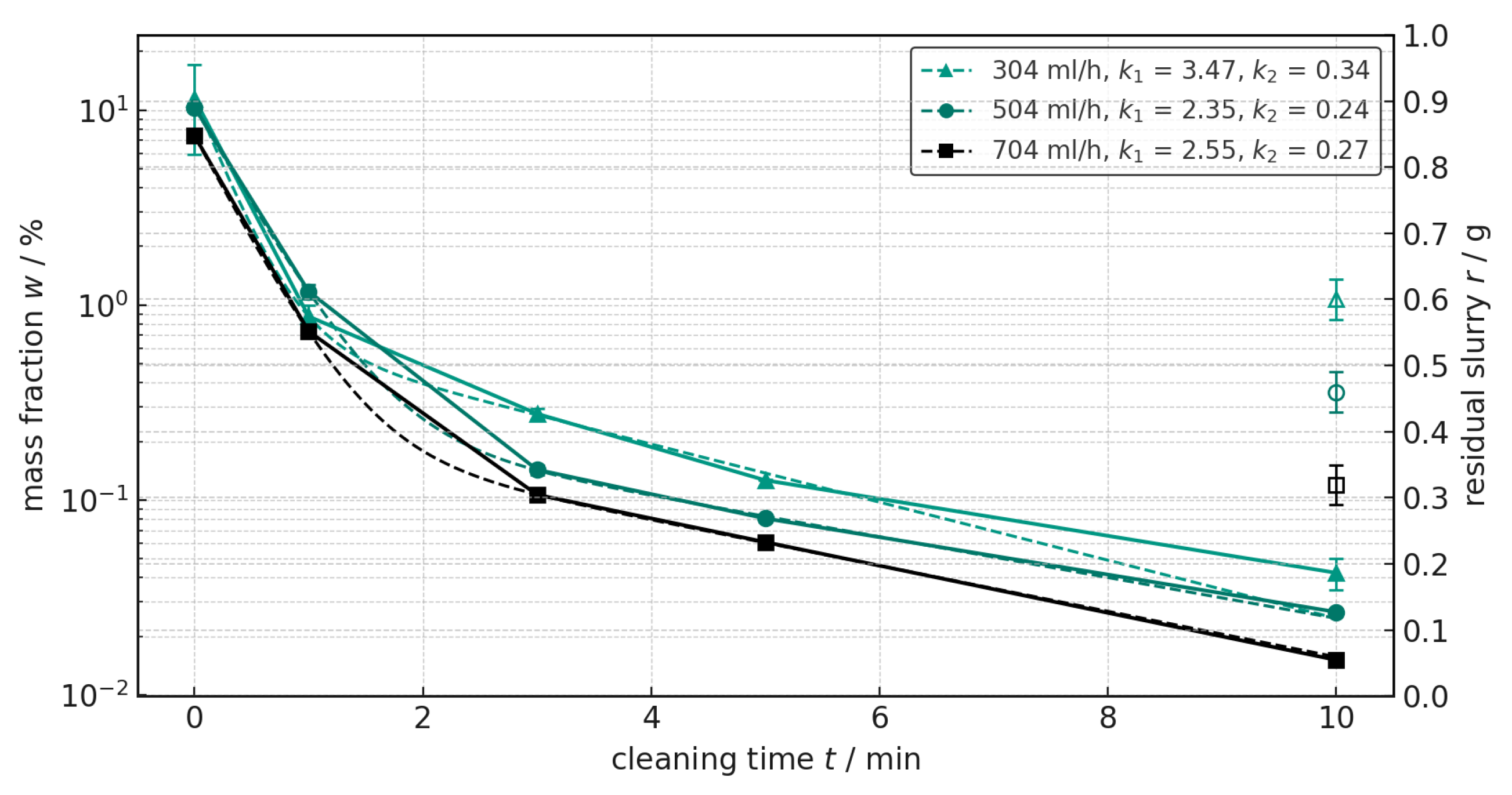

3.2. Cleaning Time

The cleaning time, although one component of the Sinner circle, is not varied as a separate parameter in this work. Rather, continuous cleaning curves are obtained by measuring time-specific samples. The optimal duration must be chosen to ensure complete removal of residues without excessive consumption of resources. This is particularly important for industrial applications where both the effectiveness and efficiency of the cleaning process are of great importance. In general, all experimental investigations, which will be elaborated in more detail in the following sections, showed a reduction in slurry weight fraction with increasing cleaning time. The results generally showed that the cleaning performance is highest at the beginning of the cleaning process. With increasing time, the slope of the curve, and thus the amount of residue removed, decreases, indicating a decreasing effectiveness over time.

Most cleaning samples show that cleaning is largely complete after five minutes, which is sufficient to assess the effectiveness of the method. After ten minutes, only a small mass fraction of the anode slurry remains, indicating almost complete removal of the residues by the cleaning methods used. Further evaluation reveals two essential processes. Firstly, the remaining suspensions are discharged, and then the residues are rinsed out. To quantify the cleaning kinetic, a double-exponential model

is used to fit the data and describe the decrease in mass fraction

w. The time-dependent concentration consists of two superimposed decay components.

A1 and

A2 represent the relative proportions of the decaying components and the initial mass fraction before exponential decay begins, whereas coefficient

A1 represents the rapidly decaying fraction associated with the fast removal of loosely bound residues, whereas coefficient

A2 denotes the slowly decaying fraction corresponding to the gradual removal of more strongly adhered or inaccessible residues. The sum of both indicates the total weight fraction of slurry at the outlet at

t = 0, i.e., how much slurry is present at the beginning of the cleaning procedure. Note that the starting point for each measurement is different. Each measurement was taken analogously, beginning with the first drop of cleaning agent and continuing for the same time interval. Slight deviations occurred at the start of each measurement depending on the cleaning medium and process parameters, because these factors strongly influence the dwell time.

The parameters

k1 and

k2 describe the corresponding rate constants. Thus, analogous to an existing model for describing the kinetics of dispersion, a kinetic model was developed to describe the cleaning processes [

40]. The rate constants primarily describe the cleaning kinetics and are referred to as the cleaning rate, which describes the cleaning speed. These parameters are crucial for determining cleaning efficiency over time. The first term in Equation (

2) describes a rapid initial reduction associated with the direct displacement effect resulting from the flow of the cleaning agent and directly rinsable residues of the suspension. The second term represents a significantly slower decrease corresponding to the removal of residual adhesions or hard-to-reach contaminants. This allows cleaning processes to be compared under identical conditions with regard to cleaning kinetics.

In addition to analyzing the cleaning kinetics and the cleaning process in the process chamber, it is crucial to quantify the amount of slurry remaining on the twin screws. Complete and effective cleaning can only be guaranteed by considering the combination of both parameters, as fast cleaning does not necessarily mean complete cleaning. When studying the cleaning efficiency of various parameters, the residual slurry remaining on the twin screws after cleaning was weighed and elicited for each cleaning strategy in the respective following chapters. Finally,

Section 3.6 summarizes every cleaning procedure that has been investigated in this study.

3.3. Variation of the Cleaning Agent

Cleaning tests using solvents such as ethanol, isopropanol, acetone and recommended industrial cleaners were conducted as part of initial preliminary testing. After consultation with industry experts and based on the knowledge gained, the cleaning media were narrowed down to the following for more specific investigation.

Figure 5 compares the cleaning media deionized water, ethanol, COSA™ CIP 96 and CB 100 in terms of their effectiveness in removing residues from the anode slurry and shows the different cleaning kinetics. The exponential fit according to Equation (

2) is also shown and the numeric value of the kinetic parameters

k1 and

k2 are provided in the legend. All fits reached high degrees of determination (

R > 0.999) and the full data of all fit curves is provided in the

Appendix A Table A1. The four detergents show different decay curves of the mass fractions over the cleaning time. Deionized water starts with a mass fraction at 6.568% and shows a rapid decrease in the first few minutes before stabilizing at a low level. This shows the high effectiveness of deionized water in removing anode slurry residues.

To be noted, cleaning kinetics or model parameters alone can be misleading. In addition to long-term kinetics, the absolute values and final residual slurry in the extruder must be compared. For the final assessment, the residual slurry after each cleaning process was plotted on the second y-axis in

Figure 5. This data confirms that water is the most effective cleaning medium because the residual slurry mass is lowest. While the initial ejection removes most of the slurry produced from the extruder chamber, the removal of the last particulate residues is crucial for effectiveness.

Ethanol starts at 4.376% and also shows a rapid decrease in the first few minutes, but stabilizes at a slightly higher level than deionized water. The second highest cleaning rate k1 at the beginning of 6.234 is obtained for Ethanol. This is due to the fact that ethanol has reached its cleaning limit and only removes the superficial and easily soluble components of the anode slurry. Although ethanol lowers surface tension, it does not lower it enough to break the adhesion of binders. In contrast, water-based anode slurries are formulated to adhere well to surfaces. The less soluble components, such as graphite and carbon black, which are more adherent to the surface, remain on the screws and are not effectively removed. As a result, after about one minute of cleaning, only relatively clear ethanol flowed from the extruder outlet without a large amount of suspended slurry residue which is confirmed by a small value of 0.042 for k2. In comparison, deionized water shows a k2 value of 0.342, indicating much better cleaning efficiency over a longer cleaning time. Therefore, from a chemical perspective, ethanol proves to be an ineffective cleaning agent, but it emphasizes the effectiveness of the extruder in removing the remaining slurry.

COSA™ CIP 96 shows no significant change in the mass fraction of residues after 3 min, indicating that this cleaning medium is not very effective. The cleaning kinetics model also confirms this, as it yields the only negative k2 value for this medium. The slightly negative value most likely stems from fitting and experimental errors and should be interpreted as zero, i.e., the absence of a slower, diffusion-driven deep cleaning. Graphite and carbon black are hydrophobic, carbon-based materials that are difficult to dissolve in water-based cleaners. The chemical stability and strong adhesion of these components can reduce the effectiveness of CB 100. Additionally, the low-foaming formulation, when combined with the shear forces caused by rotational speed, limits interfacial activity. This reduces the mechanical detachment required to remove fine graphite or carbon black (CB) particles, as well as the formulation’s limited compatibility with CMC-based residues. This explains why CB 100 loses its effectiveness after the first minute of cleaning. Although the cleaning rate k1 shows the highest overall value, the absolute values of the mass fractions over cleaning time show no advantage.

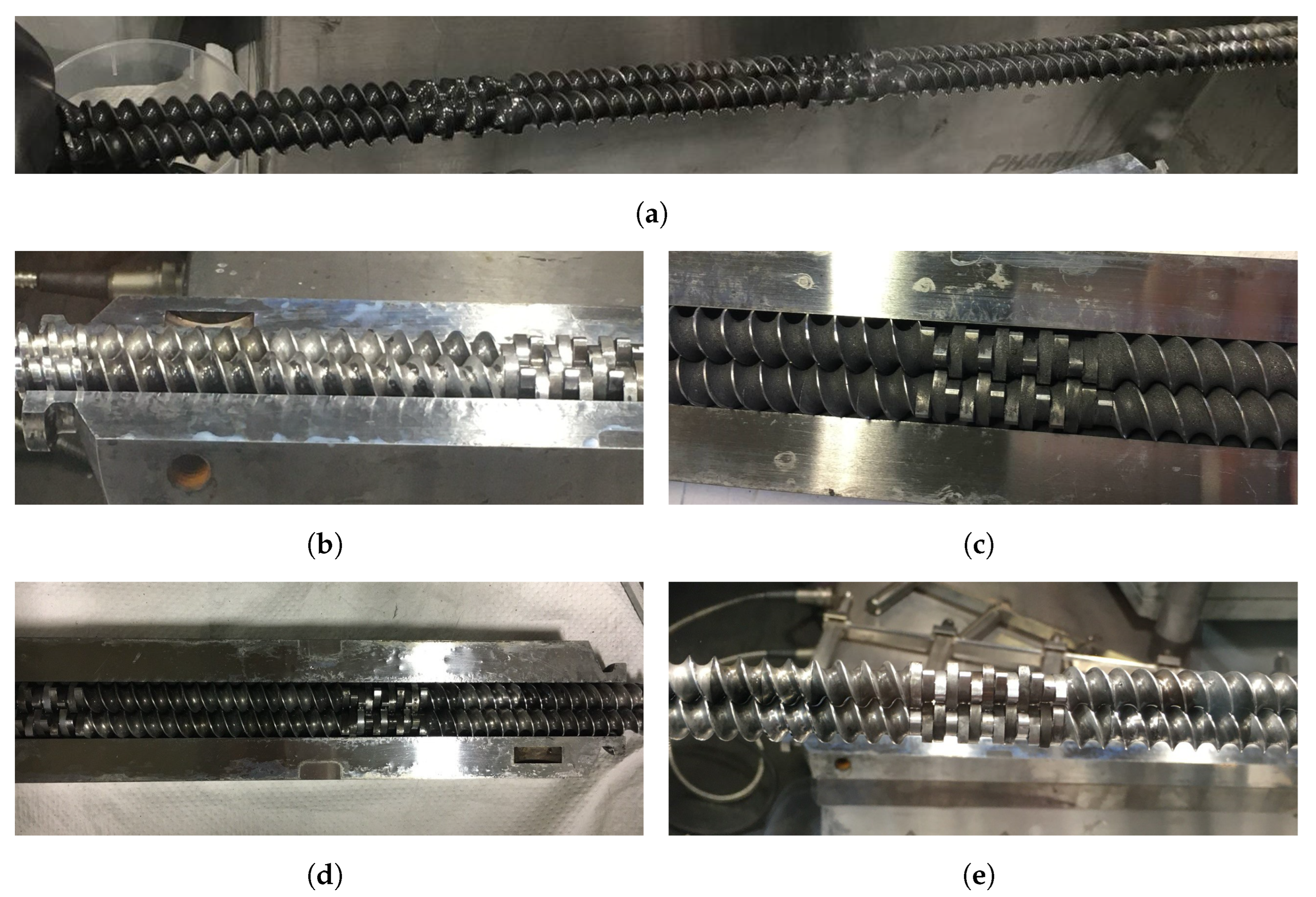

In order to better assess the effectiveness of the cleaning process,

Figure 6a illustrates the double screw geometry used immediately after processing the anode slurry formulation. The black slurry can clearly be seen distributed along the screw, particularly in the kneading elements and in the last section of the conveyor elements before discharge.

Figure 6b–e shows the twin screws at the end of each cleaning process for visual assessment. For this purpose, the four different cleaning media were considered separately. At first glance, the screw appears clean after cleaning with CB100, but upon closer inspection, many black spots remain, indicating that they did not come off during cleaning. For the ethanol procedure, it is clear that the slurry dried more strongly on the screw elements. For this reason, ethanol is absolutely unsuitable for removing residual slurry. With COSA CIP as the cleaning medium, the screw appears very dark, which is confirmed by the cleaning performance of the measured samples.

In summary, deionized water with a high cleaning rate of k2 has the best cleaning performance and is the most effective cleaning medium under the tested conditions. Also, there are hardly any visible residues and the screw alone shows the cleanest results based on visual assessment. Furthermore, when using water as a cleaning agent, no further impurities originating from the cleaning agent itself are to be expected that could affect the quality of the slurry. This is why further testing of process parameters was carried out with this solvent.

3.5. Influence of Temperature

To investigate the cleaning process at elevated temperature, all zones of the extruder were heated to 90 °C. In addition, the screws were cleaned with deionized water at a moderate flow rate of 556 mL/h and a screw speed of 500 rpm. The sample water with the anode slurry residue, taken at the extruder outlet, had a measured temperature of about 50 °C. The cleaning temperature otherwise used is 20 °C, and cleaning with deionized water is also used for comparison in this chapter.

The results of the analysis of the influence of temperature are shown in

Figure 9. When cleaning with deionized water at 50 °C, the initial mass ratio is 7.102%, which is similar to the value for cleaning at 20 °C. However, the reduction in the mass ratio over time is much faster, so that after one minute it is well below 1% at 0.536% and after three minutes it is already below 0.1% at 0.096%. In the final phase, the mass ratio continues to decrease and finally reaches 0.020% after ten minutes, so that the mass ratio at the normal cleaning temperature is approximately twice as high. This is also confirmed by comparing the cleaning rate

k1 at the beginning of 2.94 to the cleaning rate of 2.05 at room temperature.

At higher temperatures, the deionized water is more effective in removing anode slurry residues, as evidenced by the faster and greater reduction in mass fraction over the entire cleaning time. At elevated temperatures, water becomes less viscous, improving the rinsing effect. At the same time, the viscosity of the residual slurry decreases, making it easier to wash out. Furthermore, CMC is water-soluble but swells slowly at room temperature. Higher temperatures increase the dissolution and swelling rates, causing binder residues to detach more quickly. Additionally, the surface tension of water decreases with temperature, resulting in better wetting of metal surfaces in the extruder. This means that remaining deposits are dissolved more effectively. This effect is confirmed by the gravimetrically determined residual slurry of 0.1 g at elevated temperature, compared to 0.3 g at room temperature.

Since cleaning with granules is state of the art in polymer processing using extruders, tests have also been carried out with cleaning granules after slurry production, but these require a temperature of over 150 °C. This preheating causes the residual slurry in the extruder chamber to dry out and harden, making an effective cleaning process impossible. In addition, the use of high temperatures in the extruder chamber should be avoided because, depending on the composition of the formulation, premature evaporation of the solvent or degradation of the binders could occur. Either scenario would be fatal to a flexible and automated production and cleaning process.

3.6. Overall Discussion

Comparing the cleaning efficiency of various parameters, the cleaning rate and the residual slurry remaining on the twin screws after cleaning were compared before. The parameters studied included temperature, screw speed, volume flow and the type of detergent used. These measurements provide an insight into the effectiveness of different cleaning conditions, further supported by the plotted cleaning profiles obtained from the data.

Table 1 summarizes the final measured value after each cleaning process and adds a calculation of the cleaning time until 0.01% residue is achieved. The aim is to illustrate the confirmation of taking two regimes into consideration. Hereby, the cleaning rate is discussed in terms of the remaining mass fraction after ten minutes and the predicted time to reach 0.01% concerning the efficiency. Additionally, the effectiveness must be examined in relation to the residual slurry.

Taking into account a free volume of 36.53 cm3 for our screw configuration in the extruder chamber and a density of our anode suspension of approximately 1.3 g/cm3, the extruder conveys most of the volume in the process chamber during processing without any further addition of material. Under the assumption of a fully filled extruder chamber results a slurry weight of 47.49 g which demonstrates that the remaining slurry is comparatively low by weight but clearly visible. This is confirmed qualitatively by comparing the values and shows that not all solvents are compatible and that the mechanical and thermal effects are dominant.

Residual slurry measurements and cleaning curves consistently demonstrate the significant impact of temperature, screw speed, and flow rate on cleaning efficiency. To make additional estimations, we approximated the kinetic model to predict the time, in minutes, until the remaining mass in the extruder is reduced to 0.01%. These results confirm previous findings that higher temperatures, slower long-term speeds, and higher cleaning medium volume flows optimize cleaning kinetics as they align with the mass fractions after ten minutes of cleaning. The fastest times are achieved in each case, as evidenced by the efficiency and effectiveness. Further evidence is provided by the lower residual slurry value on the twin screws. Among the cleaning agents tested, ionized water was the most effective, followed by CB100 and ethanol. A detailed analysis of these factors, supported by experimental data, provides valuable insights into optimizing the cleaning process for continuous dispersion.

For a final comparison for potential contamination with a cathode suspension that has a equally measured density of 1.3 g/cm3, a mass fraction of 0.02% results in a residual weight of 0.95 g contaminated mass that is remaining after a cleaning process of 10 min, for a worst case scenario. Taking into account that a sample container has a volume of 50 mL and assuming that the remaining cathode suspension would contaminate the anode paste, the worst-case scenario would result in contamination of 0.015%. All of this assumes that the cathode material would continue to adhere to the screw elements and would not change during the subsequent anode processing. This influence must now be validated in terms of electrochemistry.

3.7. Analysis of Cross-Contamination

Determining the effects of potential contamination during the mixing step requires investigating the resulting cell performance in terms of electrochemical properties. Due to the occurrence of unpredictable short circuits at the start of the 100-cycle test or during the test itself when contamination levels were too high, it has not yet been possible to identify a limit value for completed cleaning based solely on specific capacity data.

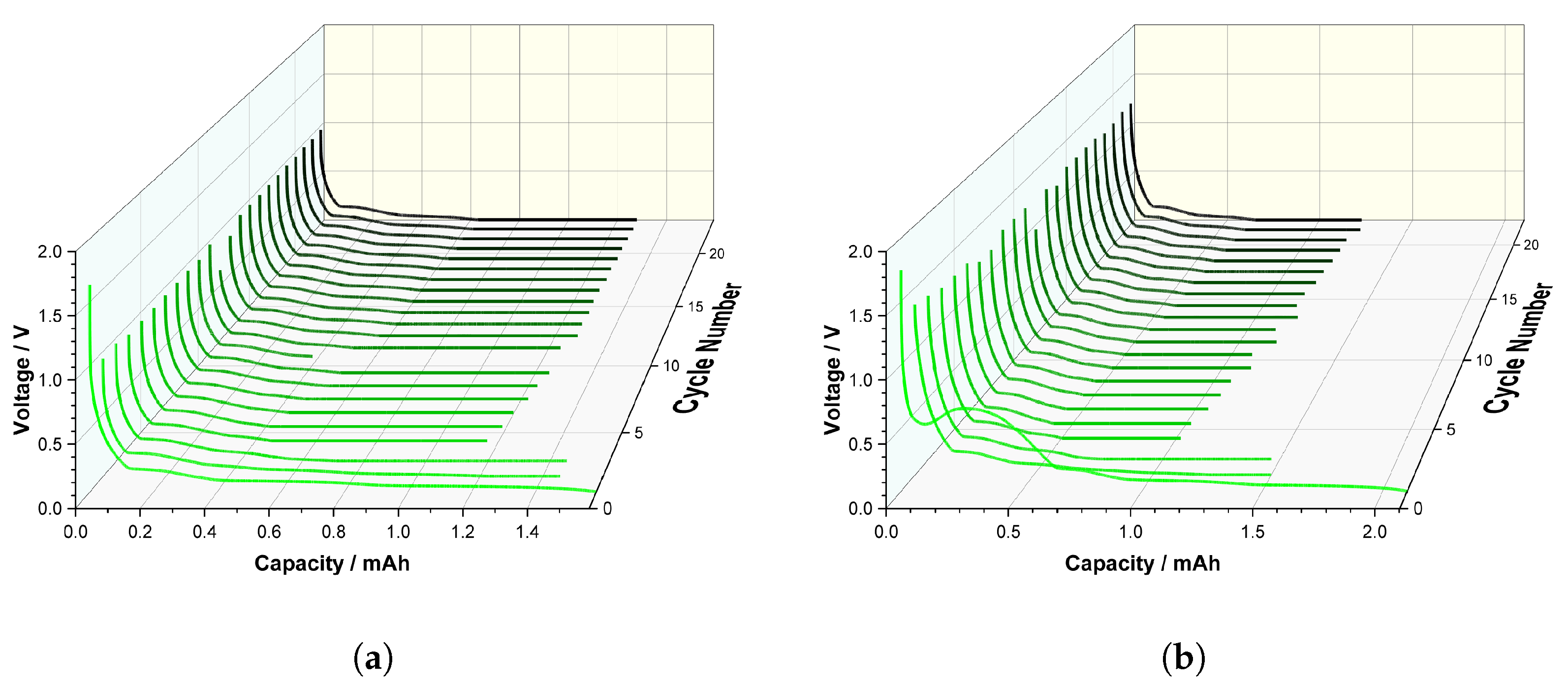

Therefore, an initial close examination was conducted to compare the discharge curves of an anode half-cell with those of a contaminated anode half-cell containing 8.5 wt% NMC. The results are shown in

Figure 10a,b. Voltage over capacity was plotted for over 20 cycles. The sequence began with C/20, changed to C/10, and then concluded with C/5. During the first cycle, a passivation layer called solid electrolyte interface (SEI) forms on the anode when the electrolyte comes into contact with the first current. This layer protects the anode from further reactions with the electrolyte, thereby stabilizing the battery. However, if the SEI layer grows too thick over time, it leads to capacity loss and increased internal resistance of the battery. Thus, the SEI layer is an important yet problematic component. Thus, the first step is an irreversible process.

As shown in

Figure 10a, the discharge curve in the first cycle of the reference anode is significantly longer, as the lower C-rate results in a slower cycle. The other curves do not show any gradations or discrepancies, such as undesirable side reactions. Thus, delithiation proceeds properly for the reference anode. A large difference in the first charging cycle is clearly visible when the reference is compared to the contaminated cell in

Figure 10b. When the voltage falls below approximately 0.7 V, there is a sudden increase in voltage. This spike is an activation or side reaction artifact caused by the NMC particles on the anode. Therefore, lithiation of NMC occur simultaneously on the contaminated anode.

Since NMC-contaminated anode half-cells led to a short circuit within a very short time when the contamination exceeded 12 wt%, LFP-contaminated anode half-cells were tested in parallel. A gradual increase in contamination was investigated. In this case, a significantly higher degree of contamination was achieved, presumably due to the considerably finer PSD of the LFP active material. The coin cells were cycled at C/10. A total of 100 cycles were performed, nevertheless, no reproducible information on longevity or performance as a function of contamination could be obtained. Thus, the decisive electrochemical analysis comparison was performed in the first cycle.

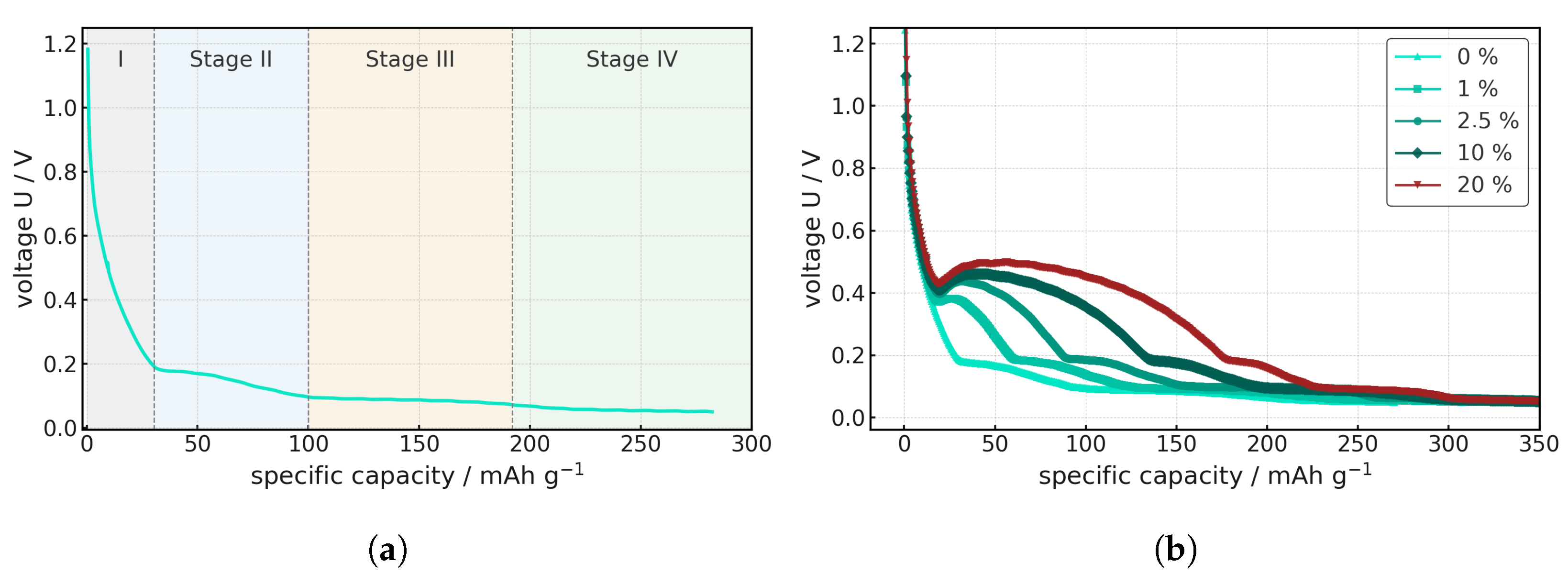

The delithiation process undergoes several stages.

Figure 11a shows the voltage curve as a function of specific capacity during the discharge of an anode half-cell. These describe the intercalation processes during delithiation and can be divided into four characteristic stages that correspond to the well-known staging sequence already described in previous studies: LiC

6 → LiC

12 → LiC

18 → LiC

24 → C [

41].

Each of these stages is characterized by a typical potential plateau in the voltage curve and reflects structural rearrangements of the intercalation system. In the initial delithiation phase, lithium departs the fully occupied intercalation sites. This stage is characterized by a relatively steep voltage drop, as the lithium concentration in the graphite layers decreases abruptly. The associated plateau is comparatively short and thermodynamically stable, but reacts strongly to ohmic losses. As delithiation progresses, the Li occupancy density for the second stage decreases. In this stage, there is a significant drop in potential, which is determined by the coexistence of two phases, LiC12 and LiC18, that describe the lithium stoichiometry in graphite. The process is increasingly limited by diffusion and interfacial kinetics. In the third phase, only part of the graphite layers are occupied by lithium. The plateau becomes flatter and is more strongly dominated by kinetic effects, as the Li transport paths are lengthened and the exchange current density at the interfaces decreases. The contribution to the total capacity is significant, but delithiation proceeds more slowly. The final delithiation stage corresponds to the removal of weakly bound residual lithium from the graphite layers. Thermodynamically, this results in a flat potential curve at low capacity. The fourth phase is characterized by a flat potential curve at low capacity.

These four stages were examined analogously for the contaminated cells, as shown in

Figure 11b. It was found that the electrochemical discharge behavior of the graphite half-cells changes significantly with increasing LFP contamination. While the reference electrode without impurities clearly exhibits the characteristic potential plateaus of the graphite staging sequence, these plateaus become significantly shorter even with low LFP content.

At around 1–2.5% contamination, the plateaus appear increasingly sloped and lose their horizontal shape. This indicates that the lithium is primarily absorbed by the contaminated cathode material in the half-cell anode, meaning that the lithium ultimately intercalates with the graphite. This additional accumulation of lithium causes a significant increase in voltage. The required end-of-charge voltage for LFP is approximately 3.6 V, which is never reached in the anode half-cell. Therefore, after the first cycle, the contaminated LFP acts as inert material in the cell, which further hinders ion transport. With 10 wt% and 20 wt% LFP content, this effect increases even more, as much more lithium is preferentially absorbed by the LFP in the first step, and this absorption is thus distributed over a wider voltage range. Thus, the transitions between stages are distorted, and plateaus are barely recognizable. This results in limiting electronic and ionic transport.

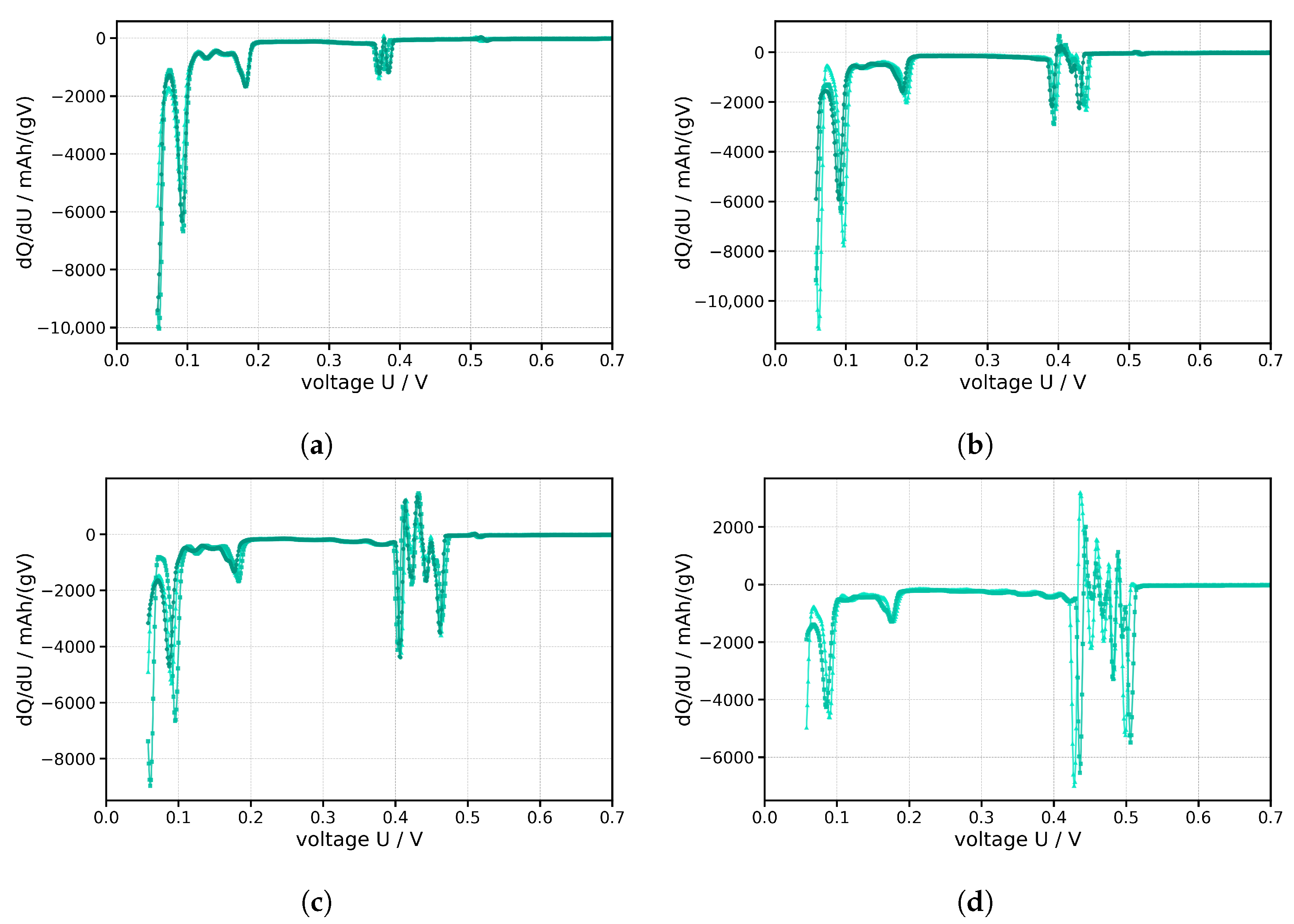

For a more in-depth electrochemical analysis of the contaminated half-cells, dQ/dU analyses were also performed. This differential capacity analysis is an established method for visualizing phase transformations and transitions within intercalation electrodes. Steps, plateaus, or breaks in the voltage curve appear as distinct peaks in the dQ/dU representation, which can be directly assigned to the phase boundaries of the graphite staging reactions. This allows the method to provide a much more precise analysis of the transition areas, the phases involved, and their relative proportions.

Figure 12 illustrates the electrochemical analysis of the various degrees of contamination, which, analogous to

Figure 11 describing the delithiation curves, increase successively from a plain anode half-cell to a contamination rate of 20 wt% LFP. The diagram describes how the capacity of a cell changes as a function of voltage, which is used to investigate phase-specific reactions and degradation mechanisms. The ordinate describes the capacity density per voltage unit and explains how much charge is stored or discharged for a given voltage change. The abscissa describes the voltage of the battery relative to the lithium reference and thus indicates the state of discharge.

The curves from the first discharge cycle are shown, as an anomaly also occurs only in the first cycle. A sharp increase in dQ/dU below 0.5 V is a critical sign of unwanted reactions, from which capacity losses can be predicted. Possible causes for this are higher internal resistance, an unstable SEI layer, or electrolyte decomposition, which can result in a short circuit. Furthermore, lithium plating occurs preferentially below 0.5 V, which electrochemically confirms cross-contamination. Lithium plating leads to an accumulation of Li ions on the electrode, from which dendrites can grow through the electrolyte. As soon as these come into contact with the separator, a short circuit occurs, stopping the cycling of the cell.

The dQ/dU analyses illustrate the influence of LFP contamination on the delithiation of graphite. While the reference electrode without foreign matter shows pronounced and sharply defined peaks that can be assigned to the classic staging transitions, these characteristics are increasingly attenuated and broadened even at low contamination levels. At 2.5 wt% LFP, the peaks appear less intense and partially split, indicating a growing inhomogeneity of the reaction fronts. At 10 wt% and 20 wt%, the transitions are severely faded, and peaks that were originally separate merge, especially in the range of 0.4–0.5 V, where transport limitations dominate, which is why the dQ/dU curve is characterized by undefined signal areas and irregular deflections.

Based on the electrochemical analysis in

Figure 12, an indicator can also be identified here in the first cycle, whereby even slight contamination of up to 2.5 wt% did not lead to any decrease in capacity or premature failure of the cell over 100 cycles. The presumed cause here is the formation of the SEI layer and the associated irreversible lithium deposition. This results in a large amount of charge being accumulated without any significant change in voltage, resulting in the high

dQ/

dU peak. The higher the contamination, the higher the peak, which shows a maximum point in the other charge direction at a contamination of 20 wt% LFP. Nevertheless, although these indicators show a clear influence of contamination on the electrochemical properties, they do not provide any information about the effects on the service life or performance of a longer-running cell. This has provided valuable electrochemical insights and quantifications on contaminated coin cells.