Abstract

Improving electronic and ionic transport and the structural stability of electrode materials is essential for the development of advanced lithium-ion batteries. Despite its great potential as a high-power anode, Ti2Nb10O29 (TNO) still underperforms due to its unsatisfactory electronic and ionic conductivity. Here, a TNO/carbon microtube (TNO@CMT) composite is constructed via an ethanol-assisted solvothermal process and controlled annealing. The hollow carbon framework derived from kapok fibers provides a lightweight conductive skeleton and abundant nucleation sites for uniform TNO growth. By tuning precursor concentration, the interfacial structure and loading are precisely regulated, optimizing electron/ion transport. The optimized TNO@CMT-2 exhibits uniformly dispersed TNO nanoparticles anchored on both inner and outer CMT surfaces, enabling rapid electron transfer, short Li+ diffusion paths, and high structural stability. Consequently, it delivers a reversible capacity of 314.9 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C, retains 75.8% capacity after 1000 cycles at 10 C, and maintains 147.96 mAh g−1 at 40 C. Furthermore, the Li+ diffusion coefficient of TNO/CMT-2 is 5.4 × 10−11 cm2 s−1, which is nearly four times higher than that of pure TNO. This work presents a promising approach to designing multi-cation oxide/carbon heterostructures that synergistically enhance charge and ion transport, offering valuable insights for next-generation high-rate lithium-ion batteries.

1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of global energy consumption and the increasing severity of environmental pollution, developing efficient and clean energy storage systems has become a critical focus in both scientific research and technological advancement [1,2,3,4,5]. Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have dominated portable electronics and electric vehicles due to their high energy density, long cycle life, and absence of memory effect, and are expected to play a central role in large-scale energy storage for future smart grids [6,7,8,9]. However, commercial graphite anodes suffer from relatively low operating potential (0.1 V vs. Li+/Li) and potential safety hazards arising from lithium dendrite formation under high-rate charge/discharge conditions, which severely constrain the development of next-generation LIBs with high power density and stability [10,11]. Therefore, it is essential to explore novel anode materials with excellent rate capability and outstanding cycling stability [8,12]. Among various candidates, titanium–niobium oxides (T–Nb–O), particularly Ti2Nb10O29 (TNO), have attracted considerable attention due to their higher theoretical capacity (~396 mAh g−1), safe lithium insertion/extraction potential (>1.0 V vs. Li+/Li), and superior structural stability [13,14,15]. The open and robust Wadsley–Roth shear crystal structure of TNO provides abundant lithium-ion diffusion channels [13,16,17]. Nevertheless, the inherently low electronic conductivity and moderate ionic diffusivity of TNO still lead to rapid capacity fading at high charge/discharge rates, posing a major challenge for practical applications.

Integrating the nanoscale design of TNO with conductive substrates seems to be a theoretically feasible approach to solving the above problems [15]. Designing TNO with nanoscale features can significantly shorten ion diffusion pathways and increase surface area, thereby enhancing reaction kinetics [12,18,19]. Incorporating TNO with conductive carbon substrates, such as graphene or carbon nanotubes, helps to improve overall electronic conductivity, suppress particle agglomeration, and mitigate volume changes during cycling [20]. However, conventional physical mixing methods often fail to establish robust interfacial contact between active materials and carbon matrices, leading to interface degradation during long-term cycling. Recently, biomass-derived carbon materials, particularly carbonized kapok fibers (CMT), have attracted considerable attention due to their natural three-dimensional tubular framework [9]. This structure not only provides abundant surface-active sites and continuous conductive channels to facilitate rapid lithium-ion transport, but also effectively buffers TNO mechanical stress during repeated cycling [21]. In addition, these carbonized fibers possess unique advantages over conventional carbon substrates, including natural abundance, low cost, and inherent hollow tubular structure [22,23]. Therefore, rationally designing TNO/biomass carbon composites that combine strong interfacial coupling with continuous conductive networks may further enhance the electrochemical performance of TNO [2].

The current TNO/carbon system is confronted with challenges such as poor interface control, uneven loading, and lack of optimization between components; yet, despite the fundamental improvements from carbon compositing, these issues limit its performance ceiling, leading to suboptimal capacity, cycling stability, and rate capability [8,19]. Herein, we ingeniously constructed a TNO/carbon microtube (TNO@CMT) composite fabricated through an ethanol-assisted solvothermal strategy followed by controlled annealing [24]. The natural hollow CMTs derived from kapok fibers act as lightweight conductive skeletons and nucleation sites for homogeneous TNO deposition [25]. By adjusting the concentration of the precursor, the load and interface structure of TNO can be precisely controlled, thereby adjusting the charge transport pathway and mechanical stability [22,26,27]. The optimized TNO@CMT-2 composite exhibits superior lithium storage performance, delivering a reversible capacity of 314.9 mAh g−1 at 0.5 C, significantly higher than those of TNO@CMT-1 (279.4 mAh g−1) and TNO@CMT-5 (259.3 mAh g−1). Notably, TNO@CMT-2 demonstrates excellent rate capability (retaining 147.96 mAh g−1 at 40 C) and long-term cycling stability (capacity retention of 75.8% after 1000 cycles at 10 C). This work not only demonstrates significant enhancement of TNO anode performance through structural optimization, but also highlights the promising potential of biomass-derived carbon materials for advanced energy storage applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Materials

Titanium isopropoxide (C12H28O4Ti, 95%, analytical reagent grade) was procured from Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, Niobium (V) chloride (NbCl5, 99.9%) and absolute ethanol (C2H5OH, 99.7%, AR) were supplied by Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Shantou, China.

2.2. Preparation of Pure TNO and TNO@CMT

Firstly, the kapok fibers were washed three times each with deionized water and anhydrous ethanol to remove surface impurities. The cleaned and thoroughly dried cotton fibers were then transferred into a high-temperature ceramic boat and carbonized in a tube furnace under a N2 atmosphere. The heating rate was set to 10 °C·min−1, and the temperature was increased to 800 °C and maintained for 2 h to obtain CMT.

TNO@CMT composites were prepared via a simple solvothermal method. Specifically, a solution of C12H28O4Ti was mixed with anhydrous ethanol, followed by the addition of NbCl5 and 50 mg of CMT. The mixture underwent solvothermal treatment at 200 °C for 6 h. The resulting product was washed by centrifugation and dried at 60 °C for 3 h. Finally, the sample was annealed at 800 °C under a N2 atmosphere for 2 h to obtain the TNO@CMT composite. In this work, precursor concentration refers to the total concentration of C12H28O4Ti and NbCl5. Given the lower bond energy of Nb–O, the effective concentration and reactivity of niobium are likely the key factors governing TNO formation on CMT [16]. Three samples with different precursor concentrations were prepared and designated as TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2, and TNO@CMT-5, corresponding to C12H28O4Ti/NbCl5 mass ratios of 0.070 g/0.385 g (1×), 0.140 g/0.770 g (2×), and 0.350 g/1.925 g (5×), respectively.

2.3. Preparation and Measurement of Batteries

Electrochemical tests were conducted on CR2025 coin cells assembled in an Ar-environment glove box (<0.1 ppm H2O/O2). The cell configuration comprises a lithium foil counter electrode and 40 μL of electrolyte, with a Celgard 2400 separator sandwiched between the working and counter electrodes. The electrolyte consisted of 1 M LiPF6 dissolved in a mixture of ethylene carbonate (EC) and diethyl carbonate (DEC), blended in a 1:1 mass ratio. The working electrode slurry was prepared by dissolving 200 mg of active material (TNO@CMT-1, -2 or -5), acetylene black, and PVDF binder (at a weight ratio of 7:2:1) in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). To ensure comparability, an identical procedure was followed for all three materials. The slurry was stirred in an automatic solder paste mixer for 10 min and then coated onto clean copper foil using a film applicator with a controlled wet film thickness of 100 μm. This step is critical for achieving a uniform layer and consistent active material loading across all electrodes. The coated foil was then dried in a vacuum oven at 100 °C for 12 h before being punched into disks with a radius of 7.5 mm. The active material loading was ~1.5 mg cm−2 across all electrodes, confirmed by measuring the mass of disks punched from various areas of the electrode foils. All capacity values (1C = 396 mA g−1) are calculated based on the total mass of the composite (TNO + CMT). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were carried out using the CHI660 electrochemical workstation. Additionally, the rate capability and cycling performance of the electrodes were evaluated utilizing the multi-channel battery testing system LANBTS BT-2016 (China).

2.4. Material Characterization

The X-ray diffractometer (XRD) characterization in this study was carried out using Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 30 mA (Smart Lab, Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Raman spectral acquisition was performed with a Renishaw microscope system utilizing 514 nm laser excitation (In Via Reflex, Renishaw plc, London, UK). The carbon content in TNO@CMT was collected using a thermal analysis system (Q600, TA, Newcastle, DE, USA). The sample was about 4.0 mg, and the heating rate was 10 °C min−1 in dry air. The chemical valence state of the elements was analyzed using an X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, AXIS SUPRA, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto City, Japan). All SEM images were captured on a VeriosG4 UC field-emission scanning electron microscope under operating conditions of 5 kV and 25 pA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). TEM and HRTEM micrographs were obtained utilizing a JEOL JEM 2100F microscope at 200 kV (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

3. Results

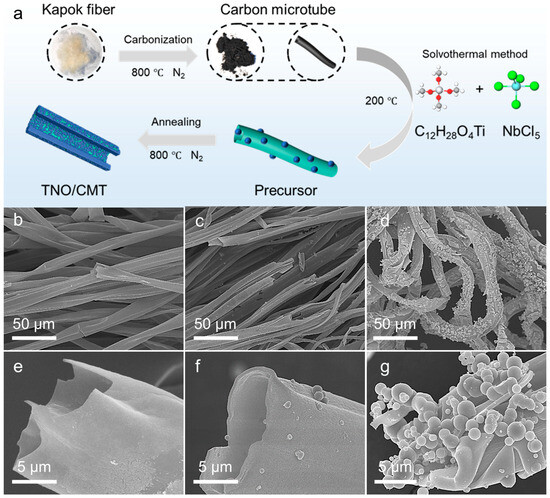

The formation process of the TNO@CMT composite is schematically depicted in Figure 1a. Initially, natural kapok fibers were carbonized under a nitrogen atmosphere, yielding carbonized kapok fibers (CMT) with a hollow tubular framework that provided both a continuous conductive pathway and abundant active sites for subsequent metal precursor deposition. Leveraging this architecture, Ti and Nb precursors were uniformly anchored onto the CMT surface through an ethanol-based solvothermal process to form a well-integrated TNO precursor/CMT composite. The annealing of the TNO precursor/CMT composite was carried out at 800 °C for 2 h under a flowing nitrogen atmosphere to obtain the TNO/CMT composite. The annealing temperature of 800 °C was selected to balance a high electrical conductivity against a moderate degree of graphitization in the CMT of the composite [26,27,28]. Notably, varying the precursor concentration was crucial for controlling the growth behavior and surface morphology of TNO on CMT. At lower precursor concentrations (TNO@CMT-1), the limited availability of metal ions resulted in sparse island-like TNO nanoparticles scattered over the carbon surface, exposing large areas of the substrate and forming discontinuous active layers that restricted electron transport (Figure 1b,e). In contrast, at higher concentrations, TNO@CMT-5 exhibited excessive TNO accumulation and localized agglomeration, which generated large TNO microspheres. These microspheres not only reduced the electrochemically active surface area but also induced significant mechanical stress upon cycling, leading to interfacial delamination from the carbon framework and ultimately compromising both ion diffusion kinetics and structural stability (Figure 1d,g). With a 2× precursor concentration, TNO@CMT-2 exhibited fine and uniformly dispersed TNO nanoparticles anchored on both the inner and outer surfaces of the carbon tubes (Figure 1c,f and Figure S1, Supporting Information). These nanoparticles constituted a continuous and interconnected ion transport network, ensuring ample exposure of active sites and efficient Li+ ion transport while mitigating aggregation-induced degradation. Furthermore, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping confirmed the homogeneous distribution of Nb, Ti, O and C throughout the carbon framework, validating the in situ crystallization and intimate interfacial coupling between TNO and CMT (Figure S2, Supporting Information). In summary, TNO@CMT-2 exemplifies the well-orchestrated integration of morphological control, interfacial engineering, and functional synergy, establishing a robust structural foundation for enhanced energy conversion and storage performance.

Figure 1.

(a) A schematic illustration of the synthesis process for TNO@CMT composites. Representative SEM images of the composites prepared with different precursor concentrations: (b,e) TNO@CMT-1, (c,f) TNO@CMT-2, and (d,g) TNO@CMT-5.

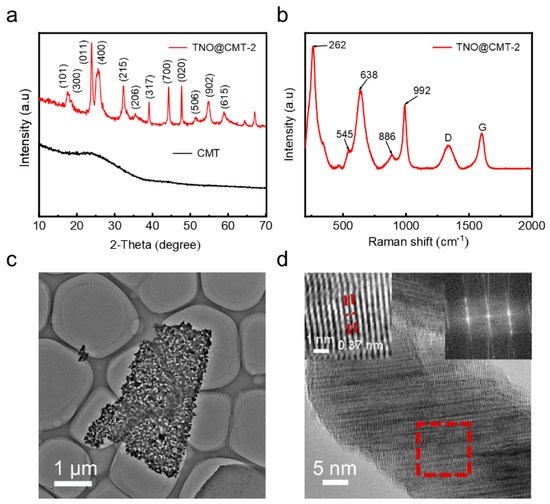

The crystalline structures of the as-prepared CMT and TNO@CMT-2 composites were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD). As shown in Figure 2a, pristine CMT exhibits two broad diffraction peaks at approximately 24.3° and 44.2°, corresponding to the (002) and (101) planes of amorphous carbon. In contrast, all diffraction peaks of the TNO@CMT-2 composite can be unambiguously indexed to the monoclinic Ti2Nb10O29 phase (JCPDS No. 72-0159) [29], confirming the successful formation of crystalline TNO. The characteristic broad peaks of the CMT are not observed in the TNO@CMT-2 composite XRD pattern, primarily because the diffraction intensity of crystalline TNO significantly exceeds that of the amorphous carbon background. The diffraction patterns of the three TNO@CMT composites (TNO@CMT-1, -2 and -5) show consistent positions and relative intensities of the characteristic peaks, indicating that varying the precursor concentration does not alter the crystal structure of TNO (Figure S8, Supporting Information). To further probe the local crystal structure, Raman spectroscopy was performed on the TNO@CMT-2 composite (Figure 2b). The distinct vibration bands at 638 and 992 cm−1 correspond to Nb–O–Nb stretching and Ti–O stretching in octahedral sites, respectively, which are characteristic of monoclinic Ti2Nb10O29. Moreover, the D band (1340.8 cm−1) and G band (1598 cm−1) of the CMT exhibit an intensity ratio (ID/IG) of 0.65, indicating a high degree of graphitization that can facilitate electron transport [29]. The microstructure of TNO/CMT-2 was examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), high-resolution TEM (HRTEM), and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) (Figure 2c,d). TNO consists of well-dispersed nanosized particles forming interconnected nanosheets. Meanwhile, HRTEM reveals clear lattice fringes with an interplanar spacing of 0.37 nm, corresponding to the (011) plane of Ti2Nb10O29. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern exhibits sharp, discrete spots, confirming the single-phase monoclinic structure.

Figure 2.

Structural and morphological characterization. (a) XRD patterns of TNO@CMT-2 and pristine CMT, (b) Raman spectrum, (c) TEM image, and (d) HRTEM image of TNO@CMT-2, with the inset showing the corresponding FFT and inverse FFT patterns from the red box area.

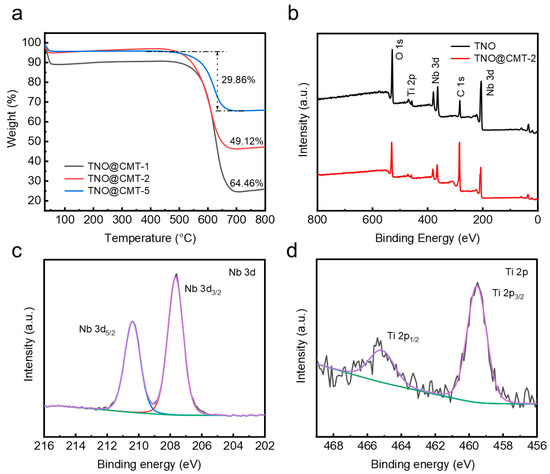

The contents of TNO/CMT components were systematically assessed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) under air atmosphere (Figure 3a). During heating to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C·min−1, CMT and TNO/CMT samples exhibited two distinct weight loss stages. The minor mass loss below 200 °C originated from the desorption of physically adsorbed water, while the major weight reduction occurring between 550 and 650 °C was attributed to the combustion of the CMT framework. After excluding the moisture contribution, the carbon contents of TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2, and TNO@CMT-5 were quantified as 64.46%, 49.12%, and 29.86%, respectively. Correspondingly, the TNO loadings increased gradually from 25.54% to 45.88%, and finally to 65.14%. This quantitative evolution matches well with the morphological gradient observed in the SEM results, confirming a controlled deposition of the TNO phase. To further examine the chemical states and surface composition, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on TNO and TNO@CMT-2 (Figure 3b). The survey spectra revealed the presence of Ti, Nb, O, and C as the major elements, without any additional peaks, in good agreement with the EDS results. The enhanced C 1s signal intensity of TNO@CMT-2 compared with pristine TNO was attributed to the contribution of the conductive CMT substrate. The C 1s spectrum could be deconvoluted into three peaks centered at 284.8, 285.7, and 288.9eV, which are assigned to C–C, C–O, and C=O functional groups, respectively (Figure Fast Phase a, Supporting Information). The O 1s spectrum features two peaks at 530.8 eV and 532.1 eV, attributed to the M–O lattice oxygen (M = Nb/Ti) and surface O–H species, respectively (Figure S3b, Supporting Information). For TNO@CMT-2, the two peaks at 465.1 and 459.5 eV correspond to Ti 2p1/2 and Ti 2p3/2, whereas the peaks at 210.3 and 207.4 eV stem from Nb 3d3/2 and Nb 3d5/2, respectively (Figure 3c,d). Compared to TNO, TNO@CMT-2 shows a shift to lower binding energy in the Ti 2p and Nb 3d peak (Figure S4a,b Supporting Information). This shift is attributed to the formation of Ti–O–C and Nb–O–C interfacial bonds, which strengthen the coupling between TNO and carbon.

Figure 3.

(a) TG curves for TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2, and TNO@CMT-5. (b) XPS survey spectra of TNO and TNO@CMT-2. (c,d) High-resolution XPS spectra from the (c) Nb 3d and (d) Ti 2p regions of TNO@CMT-2, respectively. (XPS analysis of the Nb 3d and Ti 2p regions reveals the raw data (black), baseline (green), overall fit (purple), and the deconvoluted spectral contributions. The latter are attributed to their respective spin-orbit doublets: Nb 3d (3d5/2: blue, 3d3/2: red) and Ti 2p (2p3/2: blue, 2p1/2: red).

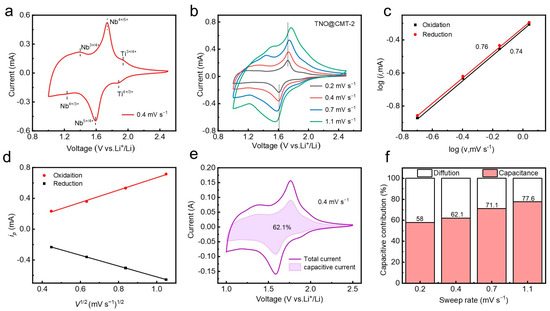

To comprehensively evaluate the electrochemical behavior of the TNO@CMT-2 electrode, cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were carried out. As illustrated in Figure 4a, the CV curve at 0.4 mV·s−1 exhibits two distinct redox peaks located at 1.59/1.73 V and 1.88/1.93 V, corresponding to the Nb4+/Nb5+ and Ti3+/Ti4+ redox transitions, respectively. The broad shape of these peaks is attributed to a solid-solution intercalation mechanism. A minor response in the 1.0–1.5 V region can be ascribed to the Nb3+/Nb4+ pair, consistent with previous reports on TNO-based anodes [21,30,31]. To further investigate the electrochemical kinetics and interfacial transport behavior, CV tests were performed at different scan rates. As the scan rate increased from 0.2 to 1.1 mV·s−1, the potential separation of the Nb4+/Nb5+ couple shifted only by 0.12 V (Figure 4b), demonstrating low polarization and fast redox kinetics. This kinetic enhancement originates from the conductive three-dimensional CMT network that accelerates electron migration and maintains structural integrity during charge/discharge [13,32,33]. The relationship between the peak current (i) and the scan rate (v) was analyzed to quantify the charge storage mechanism. Based on Equation (S1) (Supporting Information), a b-value between 0.5 and 1 reflects a mixed contribution from diffusion-controlled and capacitive processes [34,35]. The linear fits yield b-values of 0.76 (anodic) and 0.74 (cathodic), indicating the coexistence of ion diffusion and capacitive-controlled reactions (Figure 4c). To confirm the cyclic stability of the above dynamic characteristics, we further tested the CV curves of the electrode after 1000 cycles at 10 C and calculated the corresponding b-values for each cycle (Figure S9, Supporting Information). The anode and cathode exhibit b-values of 0.72 and 0.69, respectively. The tiny fluctuations of the b value in the cycle confirm the high repeatability of the rapid charge transfer kinetics dominated by the three-dimensional CMT network. Moreover, the linear correlation between the peak current and the square root of the scan rate (v1/2) confirms that diffusion-controlled lithium-ion intercalation remains a key component of charge storage (Figure 4d). Quantitative analysis (Equation (S2), Supporting Information) reveals that the pseudocapacitive contribution increases from 62.1% to 77.6% as the scan rate rises from 0.2 to 1.1 mV·s−1 (Figure 4e,f). This enhanced surface-dominated behavior originates from the hierarchical porous structure of the CMT and the homogeneous distribution of TNO nanoparticles, facilitating rapid ion/electron transport.

Figure 4.

Kinetic characterization and capacitive contribution analysis of TNO@CMT-2. (a) CV curve at 0.2 mV s−1. (b) Rate-dependent CV curves from 0.2 to 1.1 mV s−1. (c) b-value determination plot (log i vs. log v). (d) Assessment of diffusion behavior (i vs. v1/2). (e) Capacitive contribution at 0.4 mV s−1. (f) Scan rate-dependent pseudocapacitive ratio.

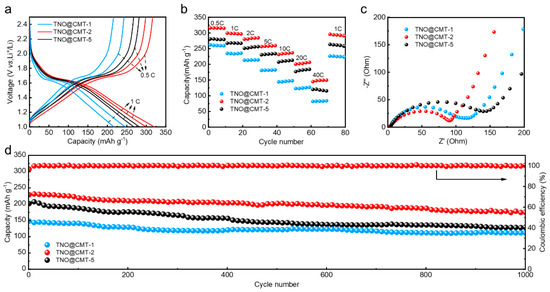

To evaluate the electrochemical performance of the TNO@CMT composites, half-cells assembled with TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2, and TNO@CMT-5 electrodes were cycled within a voltage range of 1.0–2.5 V. As shown in Figure 5a, the galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) profiles recorded at 0.5 C and 1 C exhibit nearly identical shapes for all three samples, reflecting the reversible Redox properties of the TNO phase [26,28]. Specifically, the plateau region between 2.5 and 1.7 V corresponds to a solid-solution lithiation process, followed by a distinct two-phase conversion reaction within 1.7–1.6 V. The gradual voltage decline below 1.6 V is associated with a subsequent deep lithiation process. Such multi-step reaction behavior agrees well with previous reports on Ti–Nb–O anodes, confirming a combination of solid-solution and phase-transition mechanisms during Li+ insertion and extraction [23,36,37]. Among all samples, TNO@CMT-2 delivers the highest specific capacity, achieving 314.9 mAh·g−1 at 0.5 C, which exceeds those of TNO@CMT-1 (279.4 mAh·g−1) and TNO@CMT-5 (259.3 mAh·g−1). This superior electrochemical performance can be attributed to the well-balanced composition and architecture of TNO@CMT-2. Its three-dimensional CMT framework provides a continuous conductive network and abundant electron pathways, effectively mitigating the intrinsic polarization of TNO caused by its low ionic and electronic conductivities [9,38]. Meanwhile, the homogeneous dispersion of nanosized TNO particles shortens Li+ diffusion distances and maintains structural integrity during cycling. Therefore, the optimized TNO@CMT-2 composite exhibits a synergistic enhancement in both electronic transport and electrochemical activity, laying a solid foundation for its excellent rate capability and stability in subsequent tests.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical performance of the TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2, and TNO@CMT-5 electrodes in half-cell configurations: (a) Galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) profiles at 0.5 C and 1 C; (b) rate capabilities from 0.5 C to 40 C; (c) Nyquist plots from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS); (d) long-term cycling stability at 10 C over 1000 cycles.

Figure 5b compares the rate performance of the TNO@CMT electrodes. Among all the prepared samples, TNO@CMT-2 demonstrates significantly enhanced rate capability across the entire current density range of 0.5 to 40 C. It delivers an impressive discharge capacity of 147.96 mAh g−1, which accounts for 37.4% of its theoretical capacity, at the maximum current density of 40 C. This performance highlights its superior rate capabilities compared to the pertinent literature (Table S1, Supporting Information) [8,39,40,41]. When the current density returns to 1 C, the TNO@CMT-2 electrode retains 98.8% of its initial specific capacity, confirming its outstanding reversibility and structural robustness during fast charge/discharge processes. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed to elucidate the charge-transfer and ion-diffusion behaviors of the electrodes (Figure 5c). All Nyquist plots exhibit a high-frequency semicircle followed by a low-frequency sloped line, corresponding to the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) and the Warburg impedance related to Li+ diffusion, respectively. To quantify these processes, an equivalent circuit model (Figure S5, Supporting Information) was employed, and the fitted electrochemical parameters are presented in Table S2 (Supporting Information). In this model, Rs represents the combined ohmic resistance, including the electrolyte resistance and the contact resistance at interfaces, while the charge transfer process is represented by the parallel connection of a CPE and Rct. The excellent fit (Chi-Squared values < 0.03) achieved without a separate circuit element for the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) film indicates that its resistance contribution is relatively small and is effectively integrated into the Rct [8,21]. Among the three electrodes, TNO@CMT-2 exhibited the lowest Rs (3.41 Ω) and Rct (88.40 Ω). Furthermore, the diffusion rate of lithium ions for this electrode is measured at 1.4 × 10−11 cm2 s−1, which is significantly better than that of other TNOs. This indicates that Li+ ions can migrate more efficiently within the active framework of TNO@CMT-2, benefiting from its reduced polarization and improved interfacial conductivity. The remarkable enhancement in rate capability and charge-transfer kinetics originates from the synergistic structure of the TNO@CMT-2 composite. The uniformly distributed TNO nanoparticles are intimately anchored on the interconnected CMT skeleton, constructing a continuous three-dimensional conductive network. This carbon framework not only shortens the electron transport pathway, but also provides an enlarged electrode/electrolyte contact area owing to the high surface area of CMTs, thereby accelerating both ion diffusion and electron transfer. Collectively, the optimized architecture of TNO@CMT-2 effectively integrates fast electrochemical kinetics with structural durability, underpinning its exceptional rate and cycling performance.

The long-term cycling stability of the electrodes was assessed over 1000 cycles at a high current density of 10 C (Figure 5d). TNO@CMT-2 maintained a reversible capacity of 175.43 mAh·g−1 after 1000 cycles, corresponding to 75.8% capacity retention. In contrast, TNO@CMT-1 and TNO@CMT-5 exhibited pronounced capacity fading, retaining only 112.2 and 122.9 mAh·g−1, respectively. Such a distinct discrepancy in cycling stability can be ascribed to the structural differences among the TNO/CMT composites. The structural integrity maintained by TNO@CMT-2, as evidenced by SEM analysis after 1000 cycles, stands in stark contrast to the detachment and agglomeration observed in TNO@CMT-1 and TNO@CMT-5, respectively (Figure S7, Supporting Information). For TNO@CMT-5 materials, excessively loaded TNO nanoparticles agglomerate into micron-sized spheres, readily inducing uneven stress distribution during repeated lithium charging and discharging cycles. The microcracks formed on the microsphere surface gradually propagate, causing the TNO active layer to detach from the CMT framework to degrade its rate capability and cycle performance. Conversely, TNO@CMT-1 suffers from insufficient TNO coverage, producing a discontinuous conductive network. The exposed CMT areas create localized regions of high current density, which intensify electrolyte decomposition and side reactions, further impairing cycling durability. Therefore, both excessive and deficient TNO contents compromise the structural integrity and long-term reversibility of the electrodes. In stark contrast, TNO@CMT-2 exhibits an optimal structural configuration where nanoscale TNO particles are uniformly anchored on an interconnected CMT framework. This intimate interface effectively buffers the volume variations and mitigates internal stress during repeated cycling, maintaining continuous electronic pathways and mechanical coherence. As a result, the TNO@CMT-2 electrode demonstrates outstanding cycling stability and structural endurance under high-rate operation, underscoring the critical importance of balanced architecture in achieving durable energy storage performance.

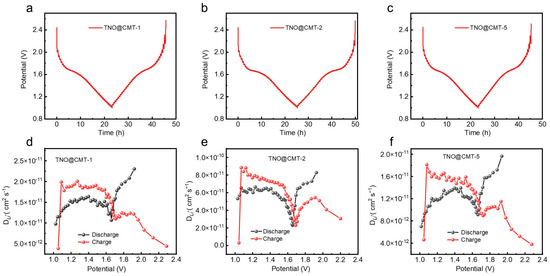

The lithium-ion transport kinetics of the TNO@CMT composites were comprehensively analyzed through the galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT), wherein galvanostatic pulses at a current density of 0.1 C were applied for 10 min each time, followed by a 20 min open-circuit relaxation period to facilitate equilibrium assessment. As depicted in Figure 6a–c, all samples exhibit distinct equilibrium voltage plateaus near 1.6 V during the titration process, which can be attributed to the Nb4+/Nb5+ redox transition. This feature is in good agreement with the voltage behavior observed in their GCD profiles, confirming the consistency of the redox mechanism across different electrochemical measurements. The lithium-ion diffusion coefficients (DLi+) calculated from Equation (S3) (Supporting Information) are presented in Figure 6d–f. During discharge (lithiation), the average lithium-ion diffusion coefficients of TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-5, and TNO@CMT-2 are 1.5 × 10−11, 1.2 × 10−11, and 5.4 × 10−11 cm2 s−1, respectively. These values were consistent with those obtained from the EIS measurements. Table S3 presents a comparison of DLi+ values for various niobium-based oxides, calculated using the same GITT test method and Fick’s second law equation [19,21,34,42,43]. The data reveal that the TNO@CMT electrode demonstrates superior lithium-ion diffusion capability. Notably, TNO@CMT-2 exhibits a lithium-ion diffusion coefficient nearly four times higher than those of TNO@CMT-1 and TNO@CMT-5, demonstrating its superior Li+ transport capability. This enhanced ion diffusion originates from the well-optimized composite architecture of TNO@CMT-2, in which the uniformly distributed TNO nanoparticles are intimately embedded within the interconnected CMT network. Such a configuration ensures a continuous conductive framework and abundant electrochemically active interfaces, thereby reducing both electron and ion transport pathways. Therefore, TNO@CMT-2 effectively accelerates charge transport kinetics due to its aforementioned advantages, thereby supporting its outstanding rate performance and cycling performance.

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis of Li+ transport kinetics. (a–c) GITT curves and (d–f) the corresponding Li+ diffusion coefficients (DLi+) for TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2, and TNO@CMT-5, measured at a current rate of 0.1 C.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we successfully synthesized Ti2Nb10O29/carbon microtube (TNO@CMT) composites via an ethanol-assisted solvothermal method combined with a controlled annealing process. The hollow tubular carbon framework provides a conductive scaffold and abundant nucleation sites for uniform TNO growth, while the precursor concentration enables precise regulation of nanoparticle loading and interface structure. Among the three precursor concentrations tested (1×, 2×, 5×), the sample prepared with the 2× concentration exhibited the most uniform anchoring of TNO nanoparticles on both the inner and outer surfaces of the CMTs, which corresponded to the highest structural integrity and the best electrochemical performance. Consequently, it delivers a high reversible capacity of 314.9 mAh·g−1 at 0.5 C, excellent rate performance of 147.96 mAh·g−1 at 40 C, and 75.8% capacity retention after 1000 cycles at 10 C, with a Li+ diffusion coefficient of 5.4 × 10−11 cm2 s−1. This work presents an opportunity to develop high-performance and sustainable electrode materials by integrating nanoscale engineering with biomass-derived carbon frameworks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/batteries11120462/s1, Figure S1: SEM images of (a) CMT and (b) TNO@CMT-2; Figure S2: Element distribution of TNO@CMT-2; Figure S3: HRXPS spectra of TNO@CMT-2 in the (a) C 1s and (b) O 1s regions; Figure S4: The XPS spectra for (a) Ti 2p and (b) Nb 3d of the TNO and TNO@CMT-2 samples were compared; Figure S5: An equivalent electrical circuit that describes the impedance behavior of TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2 and TNO@CMT-5 electrodes; Figure S6: The plots of real parts of the Zre versus ω−1/2 of TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2 and TNO@CMT-5; Figure S7: SEM images of (a) TNO@CMT-1, (b) TNO@CMT-2 and (c) TNO@CMT-5 anodes after 1000 cycles at 10 C; Figure S8: XRD patterns of TNO@CMT-1 and TNO@CMT-5; Figure S9: Electrochemical kinetics after 1000 cycles at 10 C. (a) Rate-dependent CV curves from 0.2 to 1.1 mV s−1. (b) b-value determination plot (log i vs. log v). Table S1: Comparison of rate performance for different TNO-based samples; Table S2: Simulated values of equivalent circuit components for TNO@CMT-1, TNO@CMT-2 and TNO@CMT-5 samples; Table S3: DLi+ values of the TNO-based electrodes were calculated from the GITT curves using Fick’s second law. References [8,19,21,34,39,40,41,42,43] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.N., H.X. and C.D.; methodology, Z.N. and L.L.; validation, Z.N. and H.X.; investigation, H.X. and C.D.; data curation, Z.N. and H.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.N., C.D. and L.Y.; writing—review and editing, G.W. (Guizhen Wang) and G.W. (Gengping Wan). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 22168016, 22278101, 52502237 and U24A20204), the Innovation Project for Scientific and Technological Talents in Hainan Province (Grant No. KJRC2023C08), the Innovation Team Project of Natural Science Foundation in Hainan Province (Grant No. 525CXTD607), the Finance Science and Technology Project of Hainan Province (Grant No. ZDYF2020009), and the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 525QN260).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, C.; Hu, L.; Ren, X.; Lin, L.; Zhan, C.; Weng, Q.; Sun, X.; Yu, X. Asymmetric Charge Distribution of Active Centers in Small Molecule Quinone Cathode Boosts High-Energy and High-Rate Aqueous Zinc-Organic Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2313241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bai, Y.; He, R.; Yao, F.; Chang, L.; Nie, P. In Situ Construction T-Nb2O5 Nanolayer on Porous Carbon Cloth as Binder-Free Anode for Lithium-Ion Battery with Long Cycle Life. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 670, 160635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S. The Application of BiGRU-MSTA Based on Multi-Scale Temporal Attention Mechanism in Predicting the Remaining Life of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Batteries 2025, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Du, C.; Zhou, X.; Xiong, H.; Wang, G.; Lu, X. Achieving Stable Zn Metal Anode via a Hydrophobic and Zn2+-Conductive Amorphous Carbon Interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 657, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, Y.-S.; Chang-Jian, C.-W.; Chu Weng, H.; Chiang, H.-H.; Lu, C.-Z.; Kong Pang, W.; Peterson, V.K.; Jiang, X.-C.; Wu, P.-I.; Chen, C.-P.; et al. Doping with W6+ Ions Enhances the Performance of TiNb2O7 as an Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 573, 151517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhu, H.; Liu, B.; Yang, L.; Wang, X.; Shen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ai, C.; Ren, Y.; et al. Synergy of Ion Doping and Spiral Array Architecture on Ti2 Nb10 O29: A New Way to Achieve High-power Electrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Jang, H.; Wen, B.; Jo, C.; Groombridge, A.S.; Boies, A.; Kim, M.G.; De Volder, M. Compositional Study of Ti–Nb Oxide (TiNb2O7, Ti2Nb10O29, Ti2Nb14O39, and TiNb24O62) Anodes for High Power Li Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 9878–9885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Meng, J.; Han, K.; Liu, F.; Wang, W.; An, Q.; Mai, L. Crystal Structure Regulation Boosts the Conductivity and Redox Chemistry of T-Nb2O5 Anode Material. Nano Energy 2023, 110, 108377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, K.; Zhang, G.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, S.; Sun, X.; Ma, Y. Fast Charging Anode Materials for Lithium-ion Batteries: Current Status and Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2200796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berschneider, E.; Wagner, B.; Meindl, M.; Eckardt, B. Centralized SoC Balancing for Batteries with Droop-Controlled DC/DC Converters for Electric Aircraft. Batteries 2025, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Feng, X.; Qian, Z.; Ma, J.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, W.; Han, C. Silicon Anode Modification Strategies in Solid-State Lithium-Ion Batteries. Mater. Horiz. 2025, 12, 5513–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhao, H.; Sun, J.; Han, Q.; Zhu, J.; Lu, J. Insights into Micromorphological Effects of Cation Disordering on Co-free Layered Oxide Cathodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2204931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, X.; Guo, J. Synthesis of Ag-Coated TiNb2O7 Composites with Excellent Electrochemical Properties for Lithium-Ion Battery. Mater. Lett. 2017, 197, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Yao, T.; Ji, X.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, X.; Zhang, B.; Ma, C.; Meng, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H. Enhancing the Lithium Storage Performance of the Nb2O5 Anode via Synergistic Engineering of Phase and Cu Doping. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 22055–22065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Du, S. Optimizing Porous Transport Layers in PEM Water Electrolyzers: A 1D Two-Phase Model. Batteries 2025, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Yuan, T.; Pang, Y.; Zheng, S. Optimizing Charge Dynamics in Ti2Nb10O29 Anode via Strategic Orbital Hybridization and Delocalized Electronic Engineering. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 690, 137323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Wan, G.; Wu, L.; Shi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, G. Iron-Doped Nickel–Cobalt Bimetallic Phosphide Nanowire Hybrids for Solid-State Supercapacitors with Excellent Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 654, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Lan, H.; Yan, L.; Qian, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, H.; Long, N.; Shui, M.; Shu, J. TiNb2O7 Hollow Nanofiber Anode with Superior Electrochemical Performance in Rechargeable Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nano Energy 2017, 38, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, G.; Wan, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Deng, Z.; Chai, J.; Wei, C.; Wang, G. Titanium Niobate (Ti2Nb10O29) Anchored on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Foams as Flexible and Self-Supported Anode for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 587, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.-Q.; Xie, X.; Chen, K.; Hao, X.; Jiang, M.; Tang, Y.; Xie, H.; Wen, Z. V/F Co-Doped TNO Anode Enables Superior High-Power and Long-Life Li-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 40433–40442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Du, C.; Zhao, H.; Yu, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wan, G.; Wang, L.; Wang, G. Nanoengineering of Ultrathin Carbon-Coated T-Nb2O5 Nanosheets for High-Performance Lithium Storage. Coatings 2025, 15, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Hu, M.; Xu, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Z. Smart Construction of Ti2Nb10O29/Carbon Nanofiber Core-Shell Composite Arrays as Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 886, 161146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Deng, S.; Feng, S.; Wu, J.; Tu, J. Hierarchical Porous Ti2 Nb10 O29 Nanospheres as Superior Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 21134–21139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Jiang, B.; Zhu, J.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. Early Remaining Useful Life Prediction for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using a Gaussian Process Regression Model Based on Degradation Pattern Recognition. Batteries 2025, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Bao, J.; Lu, C.; Zhou, X.; Xia, X.; Zhang, J.; He, X.; Gan, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Solvothermal Synthesis of TiNb2O7 Microspheres as Anodic Materials for High-Performance Lithium–Ion Batteries. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2025, 29, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Alwarappan, S. Transformation of Biomass Precursor into Both High-efficiency Cathode Catalyst and Solid Electrolyte for Rechargeable Zn-air Batteries. Small 2025, 21, 2502395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Wu, L.; Du, C.; Lv, H.; Wan, G.; Xiong, H.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, G. In-Situ Growth of Cross-Link NiAl-LDH Nanosheets on the Inner/Outer Surfaces of Carbon Microtubes for Anti-Corrosive Electromagnetic Wave Absorption. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 238, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Dai, A.; Zhou, T.; Huang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, T.; He, X.; Ma, L.; Xiao, X.; Ge, M.; et al. Parasitic Structure Defect Blights Sustainability of Cobalt-Free Single Crystalline Cathodes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Xu, J.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Cai, X.; Yan, H.; Fan, L.; Shui, M.; Yan, L.; Shu, J. One-Dimensional Ti2Nb10O29 Nanowire for Enhanced Lithium Storage. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 33200–33207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.-C.; Mu, T.; Zhu, X. Nitrogen Pinning Promoted Highly Reversible TiNb2O7-Graphene Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nano Energy 2025, 139, 110948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ni, M.; Liu, W.; Xia, Q.; Xia, H. N-Doped Carbon-Coated Interconnected TiNb2O7 Hollow Nanospheres as Advanced Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 15502–15512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cai, X.; Li, J.; Deng, C.; Liu, Y.; Yan, H.; Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Shui, M.; Yan, L.; et al. Ti2Nb10O29@C Hollow Submicron Ribbons for Superior Lithium Storage. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 23334–23340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jin, B.; Zhang, R.; Bao, K.; Xie, H.; Guo, J.; Wei, M.; Jiang, Q. Synthesis of Ti2Nb10O29/C Composite as an Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 14807–14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Tang, Y.; Wang, G.; Yu, W.; Wan, G.; Wu, L.; Deng, Z.; Wang, G. Multiple Reinforcement Effect Induced by Gradient Carbon Coating to Comprehensively Promote Lithium Storage Performance of Ti2Nb10O29. Nano Energy 2022, 96, 107132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazylevych, S.; Kondracki, Ł.; Sieffert, J.M.; Hebert, A.; Lee, S.; Ogasawara, H.; Trabesinger, S.; McCalla, E. Mechanistic Insights into the Surface Instabilities of TiNb2O7, a High-power Li-ion Anode. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, 2500123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Jiang, L.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Huang, S.; Luo, L.; Chen, Y. Hierarchical Porous Carbon Derived from Kapok Fibers for Biocompatible and Ultralong Cycling Zinc-Ion Capacitors. Energy Storage Mater. 2025, 77, 104219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, X.; Chang, J.; Wu, D.; Xu, F.; Zhang, L.; Du, W.; Jiang, K. Graphene Incorporated, N Doped Activated Carbon as Catalytic Electrode in Redox Active Electrolyte Mediated Supercapacitor. J. Power Sources 2017, 337, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, Q.; Gao, X.; Chen, G.; Xie, S.; Cai, G.; Shen, Y.; Chen, L.; Sun, J.; et al. Facile Scalable Multilevel Structure Engineering Makes Ti0.667Nb1.333O4 a New Promising Lithium-Ion Battery Anode. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 24, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, R.; Liu, S.; Luo, H.; Chen, Z.; Ou, Y.; Wang, W.; Chai, T.; Wang, X.; Tu, S.; Chen, Z.; et al. Fast Phase Transformation of Micrometer-Scale Single-Crystal TiNb2O7 Anode for Ah-Level Fast-Charging Laminated Pouch Cell. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 108, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, M.; Wen, Y.; Wang, H.; Qiu, J.; Xu, B. High-Rate Lithium Storage Performance of TiNb2O7 Anode Due to Single-Crystal Structure Coupling with Cr3+-Doping. J. Power Sources 2023, 564, 232672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Su, T.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Manawan, M.; Ma, D.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Z.; et al. Strain and Doping Engineerings Unlocking Power Density and Cyclability of Microspherical TiNb2O7 Anodes of Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 108, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wang, F.; Yang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J. Realizing Rapid Electrochemical Kinetics of Mg2+ in Ti-Nb Oxides through a Li+ Intercalation Activated Strategy toward Extremely Fast Charge/Discharge Dual-Ion Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 52, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Deng, S.; Shi, S.; Wu, L.; Wang, G.; Pan, G.; Lin, S.; Xia, X. Ultrafast and Durable Lithium-Ion Storage Enabled by Intertwined Carbon Nanofiber/Ti2Nb10O29 Core-Shell Arrays. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 332, 135433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).