KI-Assisted MnO2 Electrocatalysis Enables Low-Charging Voltage, Long-Life Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

E° = −1.25 V (vs. SHE)

E° = 0.4 V (vs. SHE)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Synthesis of Micro-Nanoparticles

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Electrochemical Tests

2.5. Full-Device Electrochemical Tests

3. Results

3.1. KI-Modified ZAB

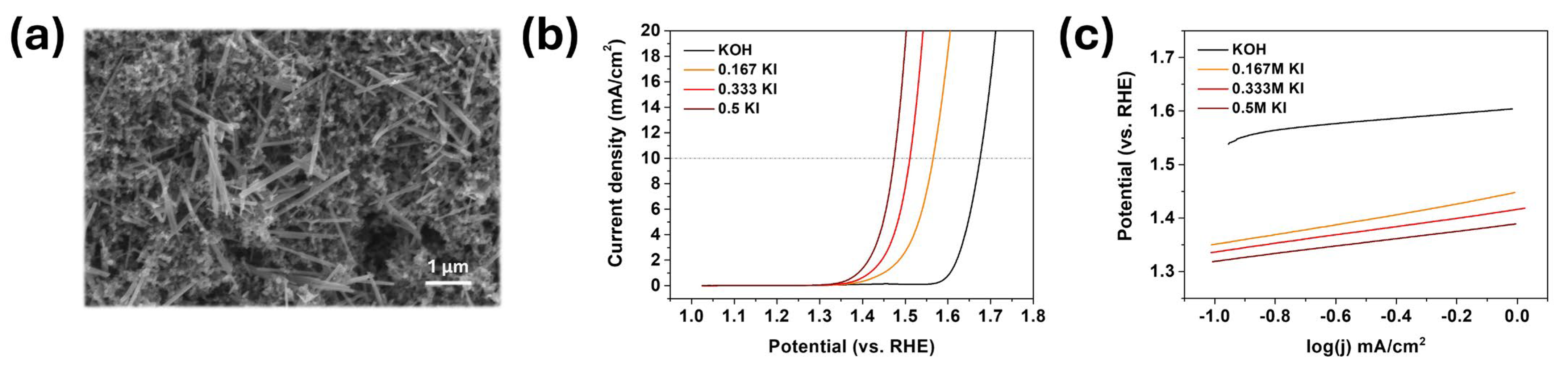

3.2. MnO2 OER/IOR Activity

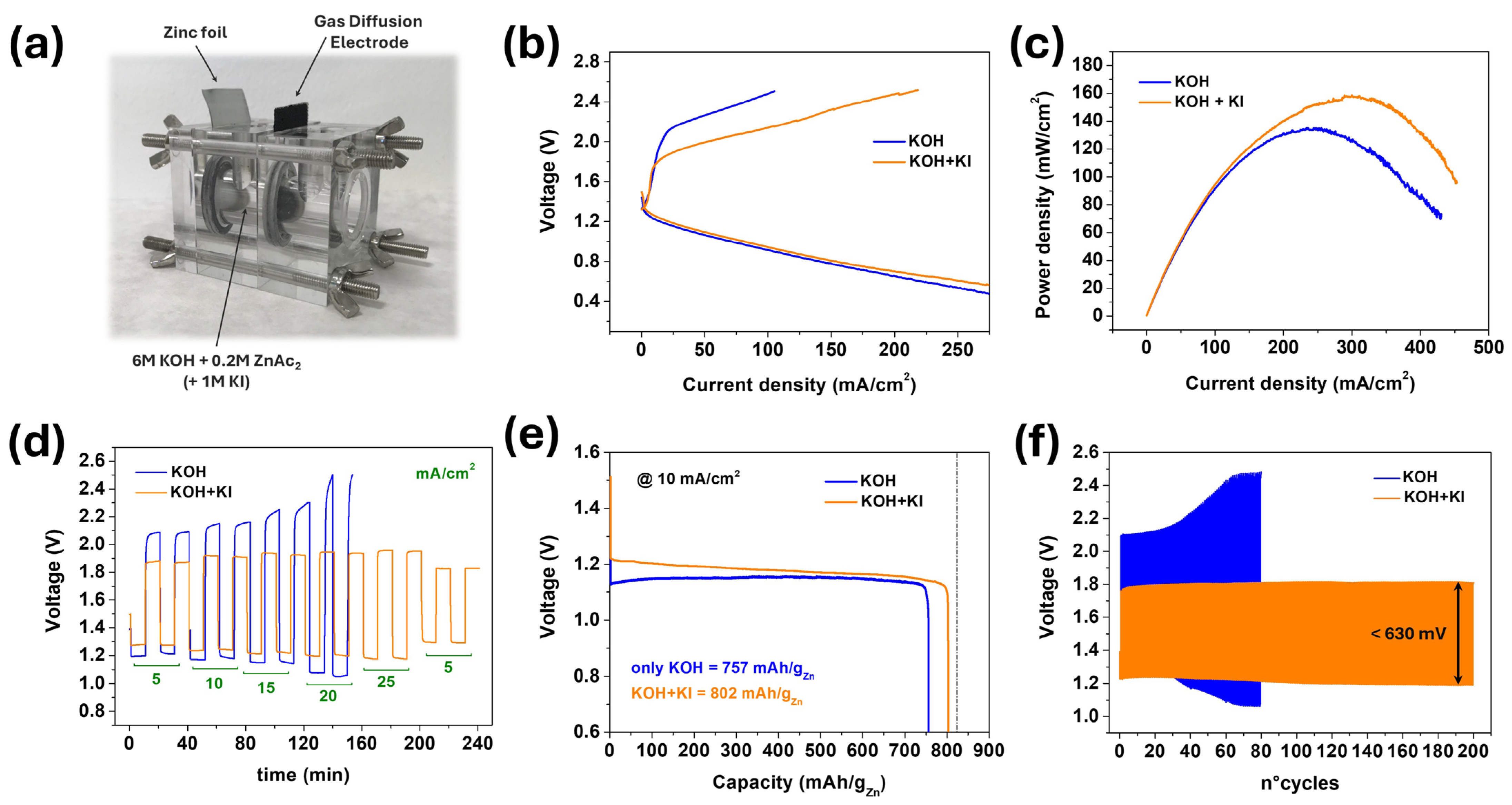

3.3. ZAB Performance

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, H.; Kim, D.; Lee, M.; Nam, K.W. Challenges and Possibilities for Aqueous Battery Systems. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Chao, D.; Hou, Y.; Pan, H.; Sun, W.; Yuan, Z.; Li, H.; Ma, T.; Su, D.; et al. Energetic Aqueous Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2201074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Kaushik, S.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Q. Sustainable Zinc-Air Battery Chemistry: Advances, Challenges and Prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 6139–6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, N.; Wang, K.; Wei, M.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Pei, P. Challenges for Large Scale Applications of Rechargeable Zn-Air Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 16369–16389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, K.; Han, C.; Pan, A. Progress on Bifunctional Carbon-Based Electrocatalysts for Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries Based on Voltage Difference Performance. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2303352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Long, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Zheng, Y.; He, B.; Zhou, M.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Hou, Z. Reducing the Charging Voltage of a Zn–Air Battery to 1.6 V Enabled by Redox Radical-Mediated Biomass Oxidation. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 8642–8650. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, X.; Sumboja, A.; Wuu, D.; An, T.; Li, B.; Goh, F.W.T.; Hor, T.S.A.; Zong, Y.; Liu, Z. Oxygen Reduction in Alkaline Media: From Mechanisms to Recent Advances of Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4643–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, V.; Hu, H.; Edison, E.; Manalastas, W.; Ren, H.; Kidkhunthod, P.; Sreejith, S.; Jayakumar, A.; Nsanzimana, J.M.V.; Srinivasan, M.; et al. Modulation of Single Atomic Co and Fe Sites on Hollow Carbon Nanospheres as Oxygen Electrodes for Rechargeable Zn–Air Batteries. Small Methods 2021, 5, 2000751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Karahan, H.E.; Shao, Q.; Wei, L.; Chen, Y. Recent Advances in Materials and Design of Electrochemically Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries. Small 2018, 14, 1801929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Kitiphatpiboon, N.; Feng, C.; Abudula, A.; Ma, Y.; Guan, G. Recent Progress in Transition-Metal-Oxide-Based Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction in Natural Seawater Splitting: A Critical Review. eScience 2023, 3, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesualdo, A.M.; Milanese, M.; Colangelo, G.; de Risi, A. Experimental Characterization of a Novel Fluidized-Bed Zn–Air Fuel Cell. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2023, 7, 2300103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; Xu, K.; Li, Y. Compositional Engineering of Sulfides, Phosphides, Carbides, Nitrides, Oxides, and Hydroxides for Water Splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 13415–13436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, C.; Sinha, N.; Roy, P. Transition Metal Non-Oxides as Electrocatalysts: Advantages and Challenges. Small 2022, 18, 202202033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Yang, J.; Ge, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, M.; Dai, L.; Li, S.; Li, W. Carbon-Based Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction and Oxygen Evolution Reactions: Optimization Strategies and Mechanistic Analysis. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 71, 234–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Ning, J.; Hu, Y. Achieving High Energy Efficiency: Recent Advances in Zn-Air-Based Hybrid Battery Systems. Small Sci. 2024, 4, 202300094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tan, P. Redox Mediators Optimize Reaction Pathways of Rechargeable Zn-Air Batteries. Innov. Energy 2024, 1, 100028-1–100028-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Ding, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, X.; Han, X.; Deng, Y.; Hu, W.; Zhong, C. A Rechargeable Zn–Air Battery with High Energy Efficiency and Long Life Enabled by a Highly Water-Retentive Gel Electrolyte with Reaction Modifier. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 201908127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.S.; Liang, X.; Ma, F.X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zhen, L.; Zeng, X.C.; Xu, C.Y. Low-Potential Iodide Oxidation Enables Dual-Atom CoFe–N–C Catalysts for Ultra-Stable and High-Energy-Efficiency Zn–Air Batteries. Small 2024, 20, 202307863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, T.; Zuo, Y.; Wei, M.; Wang, J.; Shao, Z.; Leung, D.Y.C.; Zhao, T.; Ni, M. High-Power-Density and High-Energy-Efficiency Zinc-Air Flow Battery System for Long-Duration Energy Storage. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Ma, N.; Lei, H.; Liu, Y.; Ling, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Fan, J.; et al. I3−/I− Redox Reaction-Mediated Organic Zinc-Air Batteries with Accelerated Kinetics and Long Shelf Lives. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2023, 62, 202303845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, S.; Barwe, S.; Masa, J.; Wintrich, D.; Seisel, S.; Baltruschat, H.; Schuhmann, W. Online Monitoring of Electrochemical Carbon Corrosion in Alkaline Electrolytes by Differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1585–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, T.; Dai, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yu, J.; Bello, I.T.; Ni, M. Pt/C as a Bifunctional ORR/Iodide Oxidation Reaction (IOR) Catalyst for Zn-Air Batteries with Unprecedentedly High Energy Efficiency of 76.5%. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 320, 121992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; You, Y.; Kong, L.; Feng, W.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Li, C.; He, W.; Sun, Z.M. Precisely Constructing Orbital-Coupled Fe–Co Dual-Atom Sites for High-Energy-Efficiency Zn–Air/Iodide Hybrid Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 202405533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qin, H.; Alfred, M.; Ke, H.; Cai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Huang, F.; Liu, B.; Lv, P.; Wei, Q. Reaction Modifier System Enable Double-Network Hydrogel Electrolyte for Flexible Zinc-Air Batteries with Tolerance to Extreme Cold Conditions. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 42, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Song, Y.; He, D.; Li, W.; Pan, A.; Han, C. Constructing a High-Performance Bifunctional MnO2-Based Electrocatalyst towards Applications in Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 2024, 12, 29355–29382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Yan, G.; Lian, Y.; Qi, P.; Mu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Z.; Peng, Y. MnIII-Enriched α-MnO2 Nanowires as Efficient Bifunctional Oxygen Catalysts for Rechargeable Zn-Air Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 23, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, E.; Jörissen, L.; Brimaud, S. Rational Design of a Low-Cost, Durable and Efficient Bifunctional Oxygen Electrode for Rechargeable Metal-Air Batteries. J. Power Sources 2021, 482, 228900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, Y.; Waseem, S.; Alleva, A.; Banerjee, P.; Bonanni, V.; Emanuele, E.; Ciancio, R.; Gianoncelli, A.; Kourousias, G.; Bassi, A.L.; et al. Synthesis, Characterization, Functional Testing and Ageing Analysis of Bifunctional Zn-Air Battery GDEs, Based on α-MnO2 Nanowires and Ni/NiO Nanoparticle Electrocatalysts. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 469, 143246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.; Chen, P.; Quan, X.; Si, M.; Gao, D. Improving the Oxygen Evolution Reaction Kinetics in Zn-Air Battery by Iodide Oxidation Reaction. Small 2024, 20, 202402052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Lu, Q.; Wu, L.; Zhang, K.; Tang, M.; Xie, H.; Zhang, X.; Shao, Z.; An, L. I3−-Mediated Oxygen Evolution Activities to Boost Rechargeable Zinc-Air Battery Performance with Low Charging Voltage and Long Cycling Life. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2025, 64, 202416235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, D.; Lou, X.W. Shape-Controlled Synthesis of MnO2 Nanostructures with Enhanced Electrocatalytic Activity for Oxygen Reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Lian, Y.; Gu, Y.; Yang, C.; Sun, H.; Mu, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zheng, X.; Chen, M.; et al. Phase and Morphology Transformation of MnO2 Induced by Ionic Liquids toward Efficient Water Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 10137–10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.F.; Ko, J.S.; Rolison, D.R.; Long, J.W. Translating Materials-Level Performance into Device-Relevant Metrics for Zinc-Based Batteries. Joule 2018, 2, 2519–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gaitán, E.; Morant-Miñana, M.C.; Frattini, D.; Maddalena, L.; Fina, A.; Gerbaldi, C.; Cantero, I.; Ortiz-Vitoriano, N. Agarose-Based Gel Electrolytes for Sustainable Primary and Secondary Zinc-Air Batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Biscaglia, F.; Di Masi, S.; Milanese, M.; Mele, C.; Gigli, G.; De Risi, A.; De Marco, L. KI-Assisted MnO2 Electrocatalysis Enables Low-Charging Voltage, Long-Life Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries. Batteries 2025, 11, 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120463

Biscaglia F, Di Masi S, Milanese M, Mele C, Gigli G, De Risi A, De Marco L. KI-Assisted MnO2 Electrocatalysis Enables Low-Charging Voltage, Long-Life Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries. Batteries. 2025; 11(12):463. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120463

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiscaglia, Francesco, Sabrina Di Masi, Marco Milanese, Claudio Mele, Giuseppe Gigli, Arturo De Risi, and Luisa De Marco. 2025. "KI-Assisted MnO2 Electrocatalysis Enables Low-Charging Voltage, Long-Life Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries" Batteries 11, no. 12: 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120463

APA StyleBiscaglia, F., Di Masi, S., Milanese, M., Mele, C., Gigli, G., De Risi, A., & De Marco, L. (2025). KI-Assisted MnO2 Electrocatalysis Enables Low-Charging Voltage, Long-Life Rechargeable Zinc–Air Batteries. Batteries, 11(12), 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120463