Abstract

Accurate prediction of the State of Health (SOH) of lithium-ion batteries is essential for improving the safety and longevity of energy storage systems. This paper introduces ExpertMixer, a novel model based on a fused expert network for SOH estimation. By combining the strengths of state space models and recurrent neural networks, the model effectively handles the joint optimization of long-sequence dependency modeling and complex dynamic feature extraction. To improve temporal representation, ExpertMixer utilizes sampling time-based rotary position encoding (RoPE). It consists of two expert modules: a Mamba module designed to capture global degradation trends and an LSTM module focused on modeling local dynamic fluctuations. These are adaptively fused through a learnable gating mechanism that supports multi-scale feature integration. Experiments performed on the NASA PCoE dataset show that ExpertMixer achieves optimal performance on the NASA L subset, with an average MAE of 1.047 and RMSE of 1.603. It surpasses the traditional CNN BiGRU model, which had an MAE of 2.286, by 54.2%, and improves upon the advanced SambaMixer model, which had an MAE of 1.072, by 2.3%. Under low-temperature conditions using Battery 47, the model reduces the prediction error for nonlinear degradation to an MAE of 0.539, significantly exceeding all compared methods. Ablation studies verify the effectiveness of the dual-expert structure and fusion mechanism; removing the gating module results in an 18.7% decrease in performance. This research offers a new framework for lithium battery life prediction that demonstrates improved accuracy and generalization capability, suggesting potential practical value for intelligent energy storage management.

1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (Li-ion batteries), serving as the cornerstone of modern electrochemical energy storage systems, have emerged as the preferred solution for applications ranging from portable consumer electronics to electric vehicles (EVs) and large-scale grid energy storage. This is attributable to their remarkable high energy density, excellent long-term cycle life, nearly negligible memory effect, and low self-discharge characteristics. Their revolutionary energy storage mechanism was authoritatively recognized by the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. However, repeated charge–discharge cycles induce a series of complex and irreversible physicochemical evolution processes within the battery. These are specifically manifested as structural degradation and phase separation of electrode active materials, continuous growth and reorganization of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) film, redox decomposition of the electrolyte, and uncontrolled deposition of metallic lithium, also known as lithium dendrites. These multi-scale, multi-physics coupled aging mechanisms synergistically contribute to the inevitable and progressive degradation of the battery’s maximum available capacity, which is referred to as the State of Health (SOH). When the SOH decays to a predetermined safety or performance failure threshold, the battery not only loses its functional value but also poses potential extreme safety risks, such as thermal runaway. Therefore, achieving accurate prediction of the battery’s Remaining Useful Life (RUL), which is defined as the number of remaining charge–discharge cycles that the system can endure before the SOH declines to the failure threshold, constitutes a core scientific challenge and an engineering prerequisite for ensuring the safe, efficient, and reliable operation of battery systems throughout their entire lifecycle [,].

Current mainstream methodologies for SOH and RUL prediction primarily encompass two major research paradigms: model-based, also termed physics-based, and data-driven approaches []. Within the model-based paradigm, research focuses on constructing mathematical-physical models that deeply reflect the internal aging dynamics of batteries and their long-term time-dependent behaviors, leveraging these models for state estimation and life extrapolation. Representative techniques include prediction methods based on state estimation theory, particularly within the Bayesian filtering framework. The core of this approach lies in Particle Filter (PF) and its numerous variants. These may incorporate empirical degradation models, integrate Kalman filters for state updates, or introduce intelligent algorithms like particle swarm optimization to mitigate particle degeneration and impoverishment. These methods achieve probabilistic RUL prediction through recursive updating of model parameters and hidden state variables []. Another important branch relies on fundamental electrochemical principles or equivalent circuit theory. This involves using simplified Equivalent Circuit Models (ECMs) or Electrochemical Models (EMs) that incorporate coupled multi-physics processes, such as ion diffusion, charge transfer kinetics, and concentration polarization, to indirectly characterize and predict the aging state by simulating key internal physicochemical processes. Such methods form the theoretical foundation of the state estimation modules in traditional Battery Management Systems (BMS) [].

In data-driven research on predicting the State of Health (SOH) of lithium-ion batteries, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants, such as LSTM and GRU, have become mainstream tools for lifespan modeling due to their ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies in time series data. Numerous studies have integrated recurrent networks with convolutional neural networks (CNN) to achieve synergistic optimization of local feature extraction and temporal dependency modeling. Specifically, Mazzi et al. [] adopted a “1D-CNN + BiGRU” architecture, utilizing CNN to extract local signal features and BiGRU to capture bidirectional temporal correlations based on the NASA PCoE dataset. Yao et al. [], on the same dataset, integrated wavelet activation functions and proposed a CNN-WNN-WLSTM network to enhance nonlinear signal modeling capabilities. Wu et al. [] combined convolutional autoencoders with recurrent autoencoders to achieve joint feature compression and temporal modeling via GRU networks. Zhu et al. [] introduced an attention mechanism into a CNN-BiLSTM model to emphasize the contribution of key time steps and support estimation of the Remaining Useful Life (RUL). Furthermore, diverse network designs continue to drive performance improvements: Ren et al. [] used autoencoders to preprocess data, feeding the features into parallel CNN and LSTM blocks to achieve separate optimization of feature dimensionality reduction and temporal modeling. Tong et al. [] proposed an ADLSTM network incorporating Bayesian optimization to enhance stability through adaptive hyperparameter tuning. Crocioni et al. [] compared CNN-LSTM and CNN-GRU architectures, demonstrating the efficiency advantage of GRU in lightweight scenarios. Li et al. [] proposed an AST-LSTM network to enhance the capture of dynamic degradation processes through adaptive temporal modeling. As a local feature extractor, CNN is often combined with other models to form hybrid architectures. For instance, Yang et al. [] integrated CNN with random forest (CNN-RF), using CNN for feature extraction and random forest for nonlinear regression. Safavi et al. [] proposed a hybrid model combining CNN-based feature extraction, the Coati optimization algorithm, and XGBoost for early prediction of the remaining useful life of lithium-ion batteries, achieving significantly improved accuracy with RMSE and MAPE values of 106 cycles and 7.5%, respectively. The introduction of attention mechanisms has significantly improved models’ ability to identify critical features and important time steps, establishing them as a key technical approach for State of Health prediction in complex scenarios. A growing number of studies employ multi-head or hierarchical attention mechanisms to emphasize the contributions of different cycle phases and key features. For example, the self attention knowledge domain adaptation network introduced by Chen et al. [] demonstrates the value of such architectures. In recent years, the Transformer has been gradually applied to SOH prediction due to its strength in global dependency modeling. Feng et al. [] proposed a GPT 2 based model called GPT4Battery that combines a feature extractor with a dual task head, achieving high prediction accuracy on the GOTION dataset. Gomez et al. [] used a Temporal Fusion Transformer incorporating Bi LSTM layers to handle temporal dependencies. Zhu et al. [] further refined the Transformer by introducing sparse attention and dilated convolutional layers to improve long-sequence processing efficiency. However, the quadratic time complexity of standard Transformers presents computational challenges when dealing with high sampling rate time series data []. Consequently, some studies have turned to hybrid architectures, such as combining CNN and Transformer to handle local features and global dependencies separately [], or building dual path structures with Transformer and LSTM to enhance complex dependency modeling. To improve prediction reliability and scenario adaptability, researchers have also explored various model enhancement and generalization methods. Model fusion has become an important direction, including combining deep learning with traditional techniques such as particle filters or Kalman filters for uncertainty quantification, and integrating Gaussian process regression to improve generalization in small sample scenarios. Transfer learning and domain adaptation techniques effectively address distribution shift issues. For instance, transfer learning alleviates data mismatch across different domains, and the self-attention knowledge domain adaptation network proposed by Chen et al. [] improves robustness through cross domain feature alignment. Shen et al. [] focused on specific charging patterns and employed extreme learning machines to achieve efficient feature mapping. The computational limitations of traditional Transformers in long-sequence processing have driven the development of structured state space models, which challenge Transformer dominance through their linear complexity. Gu et al. [] incorporated the HiPPO framework into the LSSL model, demonstrating training feasibility and revealing the dual recurrent convolutional representation properties of SSMs. Subsequent research continued to optimize performance, such as the S4 model by Gu et al. [], which efficiently constructs convolutional kernels through structured state matrix design. This development culminated in the Mamba model proposed by Gu and Dao [], which introduces a selective mechanism that maintains subquadratic complexity while enhancing performance, making it particularly suitable for long-sequence tasks and demonstrating advantages across multiple domains. Recent studies have further expanded the applications of SSMs. For example, Ali et al. [] and Dao and Gu [] explored the relationship between attention mechanisms and SSMs while incorporating hardware optimization experience from Transformers. Behrouz et al. [] extended Mamba-like models to adapt the selective mechanism to token and channel dimensions, offering a new paradigm for multivariate time series signal modeling and showing promising potential for SOH prediction. In summary, lithium ion battery SOH prediction has formed a research landscape dominated by recurrent convolutional hybrid models, with Transformers and SSMs representing emerging directions. However, existing methods still have room for improvement in efficient long-sequence modeling, capturing multivariate dependencies, and robustness under complex operating conditions.

Conventional model-based prediction methods exhibit considerable limitations in generalization capability, robustness, and computational efficiency. The applicability of specific models, such as highly parameterized electrochemical models or equivalent circuit models designed for particular chemical systems, is often restricted to predefined battery types, temperature ranges, and aging pathways. This makes it challenging to adapt to the diversity of real-world operating conditions. The prediction accuracy of these methods depends heavily on the precise identification of dynamically evolving parameters, including physical quantities like reaction rate constants and diffusion coefficients. The time-varying nature of these parameters during cycling is highly sensitive to dynamic operating conditions, such as fast charging and pulsed loads, often resulting in parameter drift and model mismatch problems. Furthermore, state estimation algorithms like particle filtering are inherently affected by particle degeneracy and sample impoverishment. These issues frequently necessitate the introduction of Markov Chain Monte Carlo resampling strategies for optimization, which substantially increases computational complexity and introduces implementation uncertainty. With advances in sensing technologies and computational power, data-driven approaches have emerged as a prominent research direction due to their strengths in nonlinear pattern recognition. These methods reduce the reliance on explicit physical mechanisms by mining degradation features and their correlations with health states from multi-source historical data, such as voltage, current, and temperature sequences, to achieve end-to-end prediction. Early research primarily employed classical machine learning techniques like support vector regression. More recently, deep learning technologies have gained widespread adoption owing to their capacity for automatic feature extraction. For instance, Song et al. [] combined the spatial feature extraction capability of convolutional neural networks with the temporal modeling ability of long short-term memory networks to predict health state via state-of-charge inference. Zhang et al. [] applied long short-term memory networks to capture long-term dependencies in capacity data and integrated Monte Carlo simulation to achieve probabilistic prediction under multi-temperature conditions. Despite these promising developments, current deep learning approaches still face critical limitations. Many studies have not adequately incorporated recent architectural advances such as attention mechanisms and graph neural networks, resulting in insufficient modeling capacity for the complex dynamic characteristics of battery aging. A notable example is the widespread failure to accurately represent capacity recovery phenomena. This phenomenon arises from internal relaxation processes, such as the redistribution of lithium-ion concentration gradients or structural reorganization within the solid electrolyte interphase layer. The reversible capacity rebound that occurs after specific charge–discharge protocols can significantly distort the state of health degradation trajectory, introducing strong non-stationarity. In addition, although the Transformer architecture has achieved remarkable success in sequence modeling, the quadratic computational complexity of its self-attention mechanism with respect to sequence length poses significant challenges for processing high-sampling-rate battery time-series data efficiently. Coupled with the high demand for labeled data and substantial computational resources, these limitations hinder practical engineering applications. The field of lithium-ion battery state of health assessment and remaining useful life prediction is therefore confronted with a dual challenge: traditional physical models suffer from limited generalization, while existing data-driven methods often lack the dynamic adaptability required for complex operating conditions. There is a pressing need to develop new prediction frameworks that are both efficient and robust.

In response to these challenges, this study presents an innovative mixture-of-experts deep learning architecture that integrates priors from electrochemical degradation mechanisms. The originality of this research is primarily manifested in three aspects: (1) proposing a dynamic fusion methodology tailored for the multi-timescale characteristics of battery degradation; (2) constructing an adaptive gated architecture capable of autonomously balancing long- and short-term dynamics; and (3) establishing a deep connection between the deep learning model and battery physical mechanisms. Together, these innovations constitute a novel predictive framework specifically designed for modeling complex battery aging dynamics. The proposed model achieves synergistic optimization through three key mechanisms: it captures long-term temporal dependencies via selective state space models, extracts short-term dynamic features using gated adaptive LSTM units, and establishes a deep fusion mechanism for global-local feature integration. Empirical validation conducted on NASA’s publicly available battery cycling dataset demonstrates that our approach substantially outperforms existing mainstream methods in both prediction accuracy and cross-model generalization capability. The core contributions of this work are threefold. First, we develop a hybrid Mamba-LSTM feature encoding architecture that enhances the depth and robustness of temporal modeling. Second, we design a differentiable gated expert network that dynamically weights feature representations across different chemical systems, significantly improving cross-domain adaptability. Third, we establish a physics-constrained embedded data fusion paradigm that offers a novel methodological framework for addressing critical bottlenecks in lifespan prediction under complex operating conditions.

2. Theoretical Basis and Methodology

2.1. Degradation of Battery SOH and EOL Determination

Lithium-ion batteries have been extensively utilized in portable electronic devices, electric vehicles, and renewable energy storage systems owing to their high energy density, long cycle life, and relatively low self-discharge rate. The performance degradation of batteries is generally reflected in the decline of the State of Health (SOH), which gradually decreases over time as a result of various internal and external factors, as further analyzed later in this section. SOH serves as an indicator of the battery’s current performance relative to its initial condition, specifically in terms of remaining usable capacity and output power. The SOH of a lithium-ion battery is defined as a percentage as follows:

where (Qk) represents the current capacity at the kth cycle, and Qr denotes the rated capacity. As the battery undergoes repeated charge and discharge cycles, its SOH gradually degrades. This degradation process is reflected in the evolution of external operational parameters such as voltage, current, and temperature, as illustrated in Figure 1. Battery EOL is characterized by the irreversible failure to meet the rated capacity or power requirements, signifying the transition from a functional to a failed state. This condition is intrinsically determined by the accumulation of irreversible electrochemical reactions within the cell. While the EOL is conventionally associated with the SOH decreasing below a predetermined threshold (e.g., 70% of rated capacity), the occurrence of capacity recovery effects can cause the SOH to fluctuate above and below this boundary. To resolve this ambiguity, the present work defines the EOL indicator as the first cycle subsequent to the last instance where the SOH falls below the threshold, thereby providing a stable and non-reversible benchmark for life termination.

Figure 1.

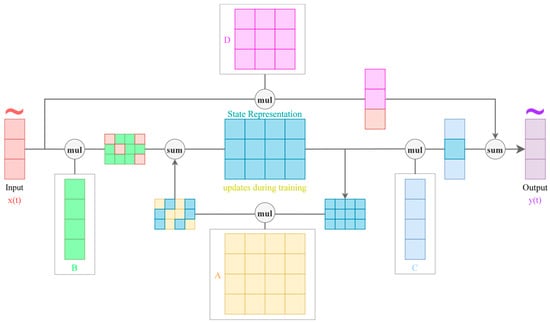

Structured State Space Model Diagram. Among them. A is State Transition Matrix; B is Input Projection Matrix; C is Output Projection Matrix; D is Skip Matrix.

The aging of lithium-ion batteries results from the combined effects of internal chemical mechanisms and external operating conditions []. Regarding internal factors, Liu et al. [] systematically summarized 21 degradation mechanisms, which can be categorized into three core mechanisms: LLI, LAM, and increase in internal resistance. Among these, LLI has the most significant impact on aging, including lithium plating and SEI film growth. Lithium plating predominantly occurs on the anode surface during charging, potentially leading to dendrite formation and internal short circuits. The continuous formation of the SEI film consumes active lithium and deteriorates reaction kinetics []. LAM is primarily characterized by structural degradation and failure of cathode active materials, often accompanied by gas generation and increased internal resistance []. The increase in internal resistance is also associated with factors such as electrode corrosion, electrolyte decomposition, and separator aging.

The external factors primarily include temperature, charge–discharge rate, depth of overcharge/over-discharge, and mechanical stress. Operating batteries outside the recommended temperature range can lead to adverse effects: elevated temperatures accelerate SEI formation, cathode degradation, and the risk of thermal runaway, while low temperatures hinder ion transport, increase internal resistance, and cause rapid capacity loss. High charging rates are prone to induce lithium plating on the anode, a process further exacerbated by Joule heating effects. Overcharging can result in irreversible structural changes in the cathode and an increase in internal resistance, whereas over-discharging may lead to dissolution of the anode current collector and promote dendrite formation during subsequent recharging.

It is evident that the degradation of the SOH in lithium-ion batteries results from the complex interplay of multiple internal mechanisms and external stressors, which also poses significant challenges to the modeling of their aging behavior.

2.2. Model Design Principles and Motivation

The degradation of the state of health in lithium-ion batteries represents a typical spatiotemporal dynamic process characterized by inherent multi-timescale properties, which pose a fundamental challenge to lifespan prediction. Specifically, battery aging involves not only long-term gradual degradation governed by irreversible mechanisms such as loss of active lithium and deterioration of active materials, but also short-term fluctuations and capacity recovery phenomena induced by internal relaxation processes, including lithium-ion concentration redistribution and dynamic reconstruction of the interface film. Conventional monolithic model architectures often struggle to accurately capture these differentiated dynamics simultaneously: while recurrent neural networks excel at modeling local temporal dependencies, they exhibit limited efficiency in capturing ultra-long-range correlations; meanwhile, emerging state space models demonstrate superior performance on long sequences but lack sensitivity in capturing transient nonlinear dynamics. To address these limitations, this study proposes the ExpertMixer model, whose core design philosophy lies in constructing a synergistic dual-expert system to, respectively, handle degradation patterns across different timescales. Specifically, the Mamba expert, based on a state space model, is designed as a global trend perceiver, aimed at efficiently capturing the macroscopic degradation trajectory spanning the entire battery lifecycle. In contrast, the LSTM expert serves as a local dynamic detector, focusing on extracting mid- to short-term capacity fluctuations and recovery characteristics. To intelligently integrate the strengths of both experts, we introduce a learnable gated fusion mechanism that adaptively adjusts fusion weights based on the real-time characteristics of the input sequence, thereby achieving seamless integration of multi-scale features from global to local levels. Furthermore, considering the physical significance of sampling time points in battery time series (e.g., discharge duration), we adopt a sampling time-based rotary position encoding to deeply embed temporal physical information into feature representations, thereby enhancing the model’s awareness of temporal dynamics. In summary, the architecture design of the ExpertMixer model is grounded in a profound understanding of the physical mechanisms underlying battery aging, with the objective of achieving more robust and accurate estimation of battery state of health through a well-defined and synergistically optimized system.

2.3. Structured State Space Models

SSMs describe the relationship between the input signal “x(t)” and the output signal “y(t)” through a hidden state “h(t)”, which evolves over time according to a linear dynamical system. The SSM is defined by the following equations:

Therefore, the SSM is referred to as a Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) system. In LTI systems, the recurrent representation of the SSM can be expressed in convolutional form: . Note that the convolution kernel K is a function of the SSM matrices and contains L elements. For large L and dense matrices , the computational cost is significantly high. Gu et al. [] constrained the matrix A to be a Diagonal Plus Low-Rank (DPLR) matrix, where , making the computation of the convolution kernel more efficient. To further enhance the performance of SSMs, Gu and Dao [] proposed Mamba, which introduces selectivity into the SSM by making the matrices , and time-varying, meaning each token is processed by its own set of matrices. Behrouz et al. [] pointed out that Mamba’s selectivity operates only at the token level and not at the channel level, which prevents information from flowing across channels. To address this issue, they proposed MambaMixer, which adds channel-level selectivity to the SSM, making it particularly well-suited for multi-channel data, such as images or multivariate time series. In simple terms, MambaMixer consists of two mixing operations: a token mixer and a channel mixer , defined as follows:

These mixers are constructed using one or more Mamba-like blocks. To obtain the output y of a single MambaMixer block, the input x is first processed by the token mixer and then by the channel mixer :

Note that the transpose operation is necessary to enable the channel mixer to operate along the channel dimension. Inspired by DenseNet [], MambaMixer further implements a learned weighted average of the outputs from earlier blocks with the input of the current block, defined as follows:

where m is the current index of M stacked MambaMixer blocks, , , , and are learnable parameters, and where is the input to the encoder model.

3. ExpertMixer Prediction Model

3.1. Model Architecture

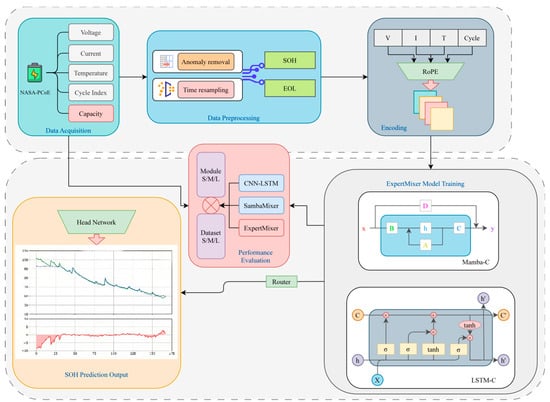

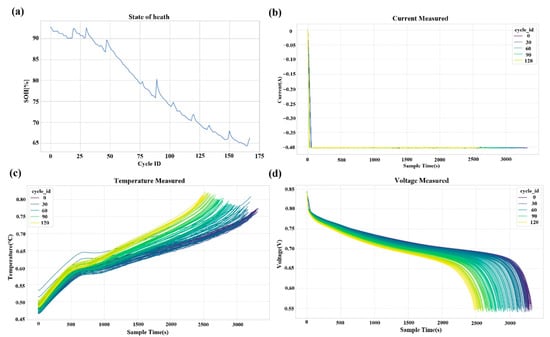

The proposed fused expert prediction network architecture is presented in Figure 2. Based on the analysis in Figure 3, we selected battery voltage, current, temperature, and cycle number as input features. These feature vectors are first transformed into hidden representations through a feature projector, then augmented with sampling time-based positional encoding and rotary positional encoding to incorporate temporal and positional information. Subsequently, the processed features are fed into both the LSTM hybrid channel feature extractor and the Mamba hybrid channel feature extractor in parallel. The extracted features from both pathways are integrated through a fused expert module, and finally processed by the prediction head module to generate the output analysis.

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of the model.

Figure 3.

(a) Life curve of 5th battery; (b) Curve of current variation with sampling time for 5th battery under different cycle rounds; (c) Curve of temperature variation with sampling time for 5th battery under different cycle rounds; (d) Curve of voltage variation with sampling time for 5th battery under different cycle rounds. This preliminary feature analysis motivates the design of the ExpertMixer architecture presented in Section 3.

Figure 3a displays the full lifecycle evolution of Battery No. 5 tested under a constant discharge current of 2.0 A and at a room temperature of 24 °C. The capacity degradation of this battery exhibits classic three-stage nonlinear behavior. During the initial phase (approximately 0–50 cycles), the capacity declines gradually, a trend primarily associated with SEI film formation. The intermediate stage (around 50–120 cycles) is marked by an accelerated decay rate, indicative of cumulative irreversible degradation mechanisms such as LAM and LLI. The final stage (beyond 120 cycles) is characterized by more intricate degradation behavior, including pronounced fluctuations and multiple instances of capacity recovery, suggesting the influence of relaxation processes like lithium-ion concentration rebalancing, stress release in electrode materials, and reconstruction of the interface layer. The curve also reveals repeated crossings of the EOL threshold, supporting the operational definition of EOL as the first cycle at which the state of health remains persistently below the threshold. From a modeling standpoint, these multi-timescale degradation patterns underscore the value of the mixture-of-experts architecture. The long-term decline trends are effectively captured by state space models, whereas local variations and transient recovery phenomena are better handled by LSTM networks. The time-varying nature of the degradation further justifies the incorporation of rotary positional encoding (RoPE), which enhances temporal representation in modeling aging dynamics. This dataset not only supplies high-quality training material but also offers critical insights into the design of prediction models grounded in physical degradation mechanisms.

Figure 3b presents the test curves of current variation with sampling time for Battery No. 5 across different cycle periods. All current curves demonstrate highly consistent linear characteristics, indicating the high control precision of the experimental system and compliance with the principle of controlled variables, thereby providing high-quality input for the model. The stability of current signals ensures consistency in input feature distribution, reduces noise interference, and facilitates the model’s learning of coupling relationships between current and other state variables such as voltage and temperature. From the perspective of aging mechanisms, the stability of current curves indirectly reflects the characteristics of internal impedance changes, demonstrating relatively consistent rate performance of the battery under test conditions. Figure 3c,d display the curves of temperature and voltage variation with sampling time, respectively. The voltage curve exhibits a typical discharge plateau, showing a monotonic decrease over time. With increasing cycle numbers, an overall voltage drop and accelerated voltage decline at the end of discharge are observed, directly indicating increased internal resistance and loss of active lithium. The temperature curve demonstrates an initial rise followed by a gradual decline, with the peak temperature gradually increasing with aging, indirectly confirming the mechanism of increased internal resistance. Voltage and temperature curves exhibit significant coupling relationships, where voltage changes are often accompanied by responsive fluctuations in temperature, providing natural samples for the model to learn electro-thermal coupling effects. The high sensitivity of voltage signals and the good stability of temperature signals constitute complementary information sources, and feature fusion can enhance the model’s state perception capability. These curves also reveal temporal dynamic characteristics of the aging process, such as increased voltage decay slope and elevated temperature baseline, providing physical basis for rotary positional encoding and helping to establish quantitative relationships between sampling time and aging state. Inter-cycle differences provide discriminative features for the model to distinguish health states, while intra-cycle consistency ensures feature extraction stability, collectively establishing a data foundation for constructing predictive models with mechanistic interpretability.

3.2. Feature Extraction Network

The hybrid expert decision network proposed in this study consists of two primary backbone feature extraction modules: a Mamba feature extraction expert and an LSTM feature extraction expert. These modules work in concert to extract critical information from time-series data across multiple dimensions. Among them, the Mamba module is designed based on a structured SSM, enabling dynamic adjustment of state dependencies and offering exceptional modeling flexibility. Its core strength lies in efficiently capturing global contextual relationships in ultra-long sequences while breaking through the efficiency limitations of traditional long-sequence modeling via linear computational complexity, achieving a balance between accuracy and speed. In contrast, the LSTM module leverages classic gating mechanisms (forget gate, input gate, output gate) and parameterized cell states to stably extract local dynamic features in medium- to long-term time-series scenarios. It mitigates the vanishing gradient problem common in traditional recurrent neural networks, ensuring the reliability of feature extraction.

To further enhance the richness and discriminative capability of feature representations, the network design transcends the limitations of single-dimensional feature extraction: it not only captures dynamic degradation patterns of battery time-series data along the temporal dimension but also incorporates feature interaction and fusion mechanisms at the channel level, fully leveraging cross-channel correlations in multivariate data (e.g., voltage, current, temperature). Specifically, the Mamba-based feature extraction process is as follows:

The extraction process of LSTM features is as follows:

where x represents the battery information features after positional encoding and input projection, and denote the Mamba and LSTM feature extraction networks, respectively, and and represent the battery capacity information features obtained after processing by the corresponding feature extraction networks.

3.3. Expert Fusion Network

To fully leverage the complementarity and diversity of features extracted by different expert models, this paper designs an adaptive hybrid expert decision module, whose core is a learnable Router mechanism. The primary function of this routing module is to dynamically evaluate the feature contributions of the two expert branches (Mamba and LSTM) to the current input sample. By quantifying the relevance of each expert’s features to the task objective, it generates adaptive gating weights. These weights directly serve as feature fusion coefficients, enabling weighted integration of the features extracted by the two expert branches. The final output is a hybrid expert feature that combines global long-sequence dependencies with local mid-to-long-sequence dynamics, effectively mitigating the modeling bias of any single model. The specific calculation formulas are as follows:

where α is a learnable parameter used to control the proportion of the two expert features, and Router is the fusion expert function. The features are then fed into the head network to obtain the final output.

3.4. Rotary Position Embeddings

In the top-level architecture illustrated in Figure 1, the positional encoding layer employs the RoPE mechanism to generate position embeddings corresponding to the cycle index k, which are subsequently added to the projected token representations. In the original Transformer model proposed by Vaswani et al. [], the introduction of positional embeddings aimed to address the self-attention mechanism’s inability to perceive sequence order. Given that the Transformer architecture inherently lacks recurrent or convolutional structures, without explicit positional encoding, the model would fail to discern the sequential relationships among elements. Among various absolute or relative positional encoding methods, the sinusoidal-cosine positional encoding used in the original Transformer remains widely adopted due to its simplicity and effectiveness. This encoding generates positional representations based on the absolute position p of an element within the sequence.

However, RoPE adopts a distinct strategy by encoding positional information in the form of rotation matrices and directly applying it to the interaction between Query and Key vectors, thereby achieving dynamic modeling of relative positional relationships. Unlike traditional sinusoidal-cosine encoding, which is simply added to feature vectors, RoPE enables the model to explicitly perceive the relative distances between elements during the computation of attention scores. This characteristic grants it stronger robustness when handling long sequences. Although SSMs such as Mamba inherently incorporate recurrent and convolutional mechanisms and already possess certain sequence-aware capabilities, explicit positional embeddings have proven beneficial in enhancing the model’s sensitivity to positional information in tasks highly dependent on spatial structures, such as vision. Based on this insight, and considering the characteristics of battery time-series data, this study introduces rotary position encoding to strengthen the model’s ability to capture long-term dependencies along the temporal dimension.

Unlike the aforementioned encoding methods based on sequence index p, this paper incorporates the sampling time corresponding to position p in cycle k into the rotary position encoding, resulting in . The core idea is to encode specific sampling time information into the feature representation through rotational transformation. Specifically, for the i-th dimension group (corresponding to dimensions 2i and 2i + 1) in the -dimensional features, the rotation matrix at position p is defined as follows:

where , and denotes the sampling time at position p in cycle k. By applying this rotation matrix to the corresponding dimension pairs of the feature vector, the rotary position embedding incorporating sampling time can be obtained as follows:

where is the raw feature vector of cycle k. Since the time signals have been resampled to a fixed length L, the time intervals between adjacent samples remain constant. However, for different batteries or different cycle periods, the actual sampling time corresponding to the same sequence position may vary. This rotary encoding mechanism based on sampling time introduces an inductive bias to the model, enabling it to extract meaningful patterns from temporal information (e.g., battery discharge duration) while enhancing the model’s adaptability to varying sampling frequencies and sample sizes.

4. Experimental Setup and Data Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

This study utilizes discharge cycle data from the lithium-ion battery dataset provided by NASA Ames Prognostics Center of Excellence (PCoE) [,]. Table 1 systematically summarizes the key testing conditions and initial state parameters of multiple 18650-type NCA lithium-ion batteries in the NASA PCoE dataset, clearly demonstrating the diversity and complexity of the experimental design. The table encompasses five critical dimensions: battery identification number, discharge current mode (constant or PWM pulse), cutoff voltage, ambient temperature, and initial capacity. The data reveal that the dataset covers discharge rates ranging from 1.0 A to 4.0 A, various voltage cutoff thresholds between 2.0 V and 2.7 V, and a broad temperature range from 4 °C to 43 °C. This experimental design incorporating multiple coupled stress factors significantly enhances the characterization capability for different aging paths and degradation behaviors of batteries. Particularly noteworthy is the substantial variation in initial capacity among different batteries (0.9280 Ah to 2.0353 Ah), which not only reflects the inherent performance variability during manufacturing but also provides a solid foundation for validating model generalization capabilities across different cells. This multi-dimensional analysis confirms that the dataset serves as an ideal benchmark for verifying the robustness and generalization potential of state-of-health prediction models.

Table 1.

Key Feature Dimensions of the NASA Dataset.

Table 2 clearly presents the battery numbering allocation strategy used in this study to construct training sets of different scales (NASA-S, NASA-M, NASA-L), with its core design intention being to systematically evaluate the relationship between model performance and both data volume and data diversity. The table adopts a matrix layout, with the three datasets arranged horizontally and battery numbers listed vertically, using “train” and “-” markers to indicate the usage status of each battery in specific datasets. It can be observed that the dataset scales are progressively increasing: NASA-S contains the smallest number of batteries with relatively simple operating conditions (e.g., predominantly constant current), while NASA-M and NASA-L gradually incorporate more batteries aged under different current modes (such as PWM), voltage cutoff points, and temperatures, significantly enriching the diversity of data distribution. This carefully designed data partitioning scheme, particularly the fixed use of Batteries #6, #7, and #47 as the test set, ensures that models of different scales and comparative experiments are all evaluated on a unified and fair benchmark. During the data preprocessing phase, cycles with obvious measurement anomalies were first removed, such as those with capacity measurements occasionally dropping to 0.0 mAh. Second, abnormal data points where the SOH decline between adjacent cycles exceeded 10% were filtered out. Additionally, invalid sampling points recorded after load disconnection in each cycle were eliminated. To further standardize the data format, the time intervals between cycles were calculated for positional encoding, and all time signals were resampled to a uniform length. Throughout the experiments and ablation analyses, the NASA-L dataset was used by default unless otherwise specified.

Table 2.

Battery numbers for different training datasets.

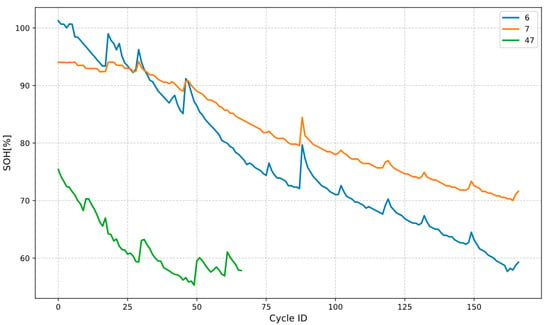

Figure 4 visually demonstrates the capacity fade curves of three test batteries (No. 6, 7, and 47), clearly revealing their distinctly different aging behaviors and degradation trajectories under the same evaluation criteria. Battery 47 exhibits the most severe and nonlinear capacity degradation, showing a rapid deterioration trend accompanied by significant fluctuations, which aligns with its testing environment at 4 °C []. In contrast, Batteries 6 and 7 demonstrate more gradual and linear capacity degradation at 24 °C. All battery curves display varying degrees of capacity recovery phenomena, manifested as local fluctuations and temporary rebounds, which directly reflect the complex internal relaxation processes of the batteries and pose a fundamental challenge to the predictive models’ ability to capture non-stationary dynamics. By visualizing the significant heterogeneity in the aging paths of test batteries, Figure 4 strongly validates the reliability and rigor of subsequent experimental results, indicating that an excellent prediction model must simultaneously adapt to multiple degradation patterns including smooth, severe, and highly fluctuating modes [].

Figure 4.

The capacity degradation curves of the three test sets of batteries.

Table 3 systematically presents the core architectural hyperparameters of the three differently scaled ExpertMixer models (S, M, L) designed in this study, including model dimension (dmodel), state dimension (dstate), and number of layers. The configuration clearly demonstrates a hierarchically progressive design strategy: from the lightweight ExpertMixer-S (dmodel = 256, dstate = 16, 8 layers) to the medium-scale ExpertMixer-M (dmodel = 512, dstate = 16, 8 layers), and finally to the large-scale complex ExpertMixer-L (dmodel = 1024, dstate = 24, 12 layers). This incremental growth in parameters directly corresponds to enhanced representational learning capacity, where expanded model dimensions enrich feature mapping capabilities, increased state dimensions improve the state space model’s ability to capture long-range dependencies, and additional layers enable the construction of more complex hierarchical features []. This table establishes a clear comparative baseline for the ablation studies in Section 4.3, “Analysis of Dataset Size and Model Parameters”. By varying only the model scale while keeping other variables constant, it enables scientific validation of the matching relationship between model capacity and data complexity, serving as crucial evidence for analyzing performance trends relative to parameter scaling.

Table 3.

Hyperparameters of Models of Varying Sizes.

The following metrics, commonly adopted in state of health (SOH) prediction tasks, were employed to evaluate the experimental results:

This section presents experiments conducted using the ExpertMixer model trained on the NASA-L dataset. The SOH estimation performance throughout the entire battery life cycle is presented in Section 4.2, while Section 4.3 analyzes the model’s performance under different training data sizes and further investigates the impact of model scale adjustments on prediction accuracy.

During data preprocessing, cycles were discarded only when an SOH drop of more than 10% between adjacent cycles was accompanied by clear signs of instrumental failure, such as capacity measurements abruptly falling to 0.0 mAh. This conservative criterion ensured the removal of severe measurement artifacts while preserving all physically plausible degradation patterns. The total number of cycles removed by this process constituted a negligible fraction of the entire dataset.

4.2. Estimation of SOH over the Battery Lifecycle

As described in Section 3, the model takes sampling-time signals from individual discharge cycles as input and outputs the estimated SOH of the battery for that specific cycle. Following the sampling methodology detailed in Section 4.1, the degradation trajectories showing capacity fade versus cycle number for each battery in the evaluation set were obtained. For the battery EOL prediction task, the proposed ExpertMixer model demonstrates outstanding performance. As shown in Table 4, ExpertMixer significantly outperforms other baseline models in EOL prediction, including CNN-LSTM, Transformer, LSTM, and Mamba. Ablation studies further validate the effectiveness of each module in the model.

Table 4.

Comparative Results of the ExpertMixer Model against Various Methods.

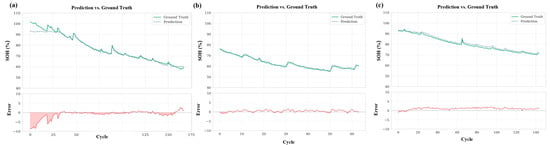

Figure 5a,b present the SOH prediction results for Batteries No. 6 and 7, respectively, under standard experimental conditions (24 °C, constant current). The capacity degradation of both batteries exhibits predominantly linear characteristics, accompanied by minor nonlinear fluctuations, providing important cases for validating the model’s fundamental prediction capability in typical aging modes. In terms of numerical fitting accuracy, the model’s prediction curves demonstrate high consistency with the measured data throughout the entire lifecycle, accurately reproducing the stable decay trend of SOH with increasing cycle numbers. The linear degradation slope shows excellent agreement with the true values. Although the overall degradation pattern is steady, the model successfully captures minor capacity fluctuations and small-magnitude recovery phenomena occurring during the intermediate cycle stage, indicating its high sensitivity in characterizing variations caused by measurement noise, minor operational disturbances, and internal electrochemical relaxation processes. These results benefit from the well-designed model architecture: the SSM component effectively captures global linear degradation patterns and establishes long-term dependencies; the LSTM network focuses on extracting dynamic features at local time scales, achieving sensitive response to subtle fluctuations []; the RoPE strategy embeds temporal physical information into feature representations, enhancing temporal awareness; and the gated fusion mechanism achieves optimal combination of different expert outputs through adaptive weight adjustment, ensuring balanced modeling of both linear trends and nonlinear variations. Corroborated by quantitative evaluation metrics, these visual results confirm the model’s excellent prediction accuracy and stability under standard operating conditions. They demonstrate that the ExpertMixer architecture not only handles extremely nonlinear degradation scenarios but also maintains outstanding performance in conventional steady aging modes, reflecting the model’s design versatility and robustness while providing a reliable technical solution for lithium battery health state prediction.

Figure 5.

(a) Comparison between predicted and actual SOH values for Cell #6; (b) Comparison between predicted and actual SOH values for Cell #7; (c) Comparison between predicted and actual SOH values for Cell #47.

Figure 5c presents the SOH prediction performance of cell 47 under an extreme testing condition at 4 °C, providing a critical empirical assessment of the model’s generalization capability in complex nonlinear degradation scenarios. The capacity fade trajectory exhibits pronounced nonstationarity, characterized by multiple abrupt decrement steps and intricate relaxation driven recoveries, which pose a stringent challenge to the model’s ability to represent dynamics []. The predicted values remain highly consistent with the measurements over the entire life cycle, accurately tracking the overall SOH decline while successfully capturing instantaneous dynamics at multiple key degradation nodes. These abrupt transitions reflect irreversible processes in the low temperature environment, including accelerated growth of the solid electrolyte interphase, deterioration of lithium ion transport kinetics, and deposition of lithium metal. The model demonstrates outstanding ability to represent subtle capacity recovery phenomena, faithfully reproducing small rebounds following each severe decrement, thereby reflecting effective parsing of underlying physicochemical mechanisms such as re-equilibration of lithium ion concentration gradients, stress relief in electrode materials, and dynamic reconstruction of the interphase. This performance is enabled by several design innovations. A rotary positional encoding mechanism based on sampling time RoPE embeds temporal physical information into the feature representation and strengthens sensitivity to temporal dependencies. Within a dual-expert architecture, a state space model expert captures long sequence global dependencies and abrupt features, whereas a long short term memory expert focuses on medium and short range dynamic patterns. The two experts are fused through a learnable gating mechanism that adaptively integrates features, allowing the model to handle both slow linear degradation and sharp nonlinear jumps. This case not only verifies predictive accuracy under extreme conditions but also demonstrates, from a mechanistic perspective, the proposed method’s capability to analyze complex aging dynamics. It provides a new benchmark testing scenario for lithium ion battery health prediction and indicates that an architecture combining multiscale feature extraction with physics informed information encoding is an effective approach to lifespan prediction under complex operating conditions.

This section demonstrates that the proposed ExpertMixer model exhibits superior performance in estimating the SOH over the entire lifespan of lithium-ion batteries. As shown in Table 4, the model achieves the lowest mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) across multiple test cells, significantly outperforming conventional methods such as CNN-BiGRU and advanced models like SambaMixer. Particularly under low-temperature conditions (Cell #47), the model demonstrates a remarkable capability in capturing nonlinear degradation processes, resulting in a substantial reduction in prediction errors. Visualization results further confirm that the model maintains high consistency between predicted trajectories and ground truth values under various aging patterns, including linear, nonlinear, and highly fluctuating degradation. Ablation studies validate the effectiveness of the dual-expert architecture and gating fusion mechanism, indicating that these components work collaboratively to enhance the model’s accuracy and robustness. In conclusion, the ExpertMixer model accurately characterizes the degradation behavior of batteries throughout their full life cycle, offering a reliable solution for SOH estimation under complex operating conditions.

The exceptional predictive performance observed in this experiment can be fundamentally attributed to the close alignment between the design principles of the ExpertMixer model and the underlying physical mechanisms of lithium-ion battery aging. The degradation of battery state of health constitutes a typical multi-timescale coupled process, which is effectively captured through a synergistic integration of global trend modeling and local dynamic detection. The Mamba expert, leveraging the linear complexity and long-range dependency modeling capability of the structured state space model, serves as an efficient trend extractor that accurately identifies long-term gradual degradation governed by irreversible mechanisms such as loss of active lithium and loss of active material. In parallel, the LSTM expert functions as a sensitive dynamic fluctuation detector, utilizing its gated mechanism to capture mid- to short-term variations and capacity recovery phenomena arising from internal relaxation processes, external disturbances, and complex side reactions like SEI film reconstruction. Connecting these components, a learnable gated fusion mechanism acts as an intelligent coordination center that adaptively adjusts the contribution weights of both experts based on the aging characteristics present in the input sequence. This comprehensive framework enables robust performance across diverse aging patterns, maintaining high accuracy whether handling the highly nonlinear dynamics of Battery #47 under low-temperature conditions or the smooth linear degradation observed in Battery #06, thereby establishing a solid theoretical foundation for reliable state-of-health estimation.

The performance improvements reported in Table 4 are further supported by statistical significance analysis. As detailed in Supplementary Note S1, the narrow confidence intervals and low standard deviations observed across five independent training runs (e.g., MAE: 1.047 ± 0.0017) confirm the stability and reproducibility of the ExpertMixer model. Additionally, Supplementary Note S2 verifies that the model maintains consistent performance with low variability across multiple runs, further corroborating the robustness of the reported results.

4.3. Analysis of Dataset Size and Model Parameters

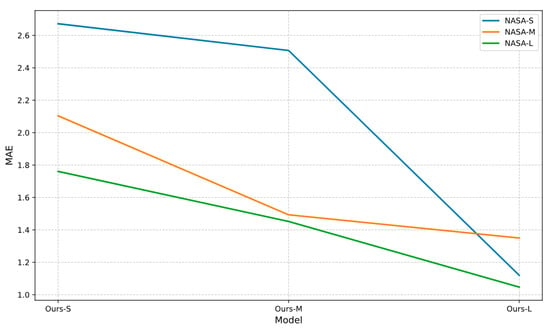

In this experiment, the performance of ExpertMixer architectures with varying scales was evaluated. The corresponding ExpertMixer S, ExpertMixer M, and ExpertMixer L models were obtained through training on three distinct datasets of different sizes: NASA S, NASA M, and NASA L. Table 5 systematically presents a comprehensive performance evaluation of the ExpertMixer model under varying architectural scales and training data volumes in a rigorous quantitative format. It serves as essential evidence for analyzing the model’s scalability and data efficiency. The table employs a three dimensional comparative structure, with the horizontal header featuring three commonly used evaluation metrics for regression tasks: MAE, RMSE, and MAPE. The vertical axis lists three models of different scales (ExpertMixer S, ExpertMixer M, ExpertMixer L), each displaying training results on three progressively larger datasets: NASA S, NASA M, and NASA L. Analysis of the data yields two clear and important conclusions. First, with a fixed training dataset size, increasing the model scale consistently leads to performance improvement. This trend remains consistent across both RMSE and MAPE metrics, clearly demonstrating that greater model capacity, reflected through larger model dimensions, state dimensions, and deeper layers, enhances the model’s representational learning capability. This enables the model to capture more complex and subtle aging patterns from the data, resulting in more accurate predictions. Second, under a fixed model architecture, increasing the amount of training data significantly enhances model performance. This pattern is most evident in the parameter-limited ExpertMixer S model. When training data expanded from the smallest NASA S to the largest NASA L, the MAE of ExpertMixer S substantially decreased from 2.672 to 1.120, representing a performance improvement of over 100%. This demonstrates that even a relatively simple model can achieve high performance levels when trained with sufficiently rich and diverse data. Although the performance improvement margin narrows for larger ExpertMixer M and ExpertMixer L models, the increasing trend remains stable and clear, indicating that large scale models require correspondingly large scale data to fully realize their potential capabilities while avoiding overfitting. In summary, Table 5 not only validates the fundamental deep learning principle that “larger models plus more data equals better performance,” but more importantly, it reveals through detailed data that the ExpertMixer model exhibits excellent scalability and data utilization efficiency. The data in Table 5 provide strong quantitative evidence for the discussion in Section 4.3 “Dataset Size and Model Parameter Analysis” of the paper, clearly indicating that expanding model architectures and collecting more diverse data represent an effective pathway for further enhancing the accuracy of lithium battery SOH prediction.

Table 5.

SOH Estimation Results under Varying Model Scales and Dataset Sizes.

Table 6 presents a systematic performance comparison between the proposed ExpertMixer model and two baseline methods across training sets of different scales, serving as crucial evidence for evaluating the model’s effectiveness and advancement. These results indicate that even under small-sample training conditions, ExpertMixer achieves higher feature extraction efficiency and model expressiveness through its innovative design incorporating expert networks and rotary position encoding. As the training data scale expands to NASA M and NASA L, all models show expected performance improvements, though ExpertMixer demonstrates the most substantial and consistent gains. On the largest NASA L dataset, ExpertMixer achieves optimal comprehensive performance (MAE 1.047, RMSE 1.603, MAPE 1.321), with its key metrics significantly outperforming reference models. This trend clearly demonstrates that the ExpertMixer architecture possesses excellent scalability, enabling it to fully leverage diverse aging patterns and complex dynamic characteristics embedded in large scale data, thereby continuously enhancing its prediction accuracy and generalization capability. Notably, the comparison with the strong baseline SambaMixer further reinforces the contribution of this study. While SambaMixer, as an advanced pure SSM based method, has significantly surpassed traditional models, ExpertMixer establishes a more balanced and powerful hybrid architecture through several innovations: enhancing medium range dynamic feature capture via LSTM expert modules, designing learnable gating mechanisms for adaptive feature fusion, and employing sampling time based rotary position encoding to deepen temporal awareness. The results in Table 6 confirm that this synergistic design effectively overcomes the limitations of single model structures, thereby achieving more robust and accurate health state prediction across all data scales. In summary, the quantitative results in Table 6 are consistent with the core argument of this study: the ExpertMixer model significantly outperforms existing mainstream methods in terms of data efficiency, performance ceiling, and architectural generality, representing a competitive and generalizable approach for accurate lithium battery health state prediction under complex operating conditions.

Table 6.

State of Health (SOH) Estimation Results with Varying Dataset Sizes.

Figure 6 systematically compares the MAE performance of ExpertMixer models with different parameter scales (S, M, L) under various training data sizes (NASA S, NASA M, NASA L). This visualization provides important quantitative evidence for the model scalability analysis in this study. From the vertical dimension analysis, a general scaling effect pattern can be observed: for the NASA-L dataset, the largest-scale model achieves the lowest prediction error, though the relationship is not strictly monotonic as evidenced by the performance variation across different model sizes. Taking the NASA L dataset as an example, the ExpertMixer S model achieves an MAE of 1.120, the ExpertMixer M model reduces it to 1.350, while the largest parameter scale ExpertMixer L model further optimizes the error to 1.047. This regular pattern confirms that increasing model capacity, manifested through larger model dimensions, state dimensions, and deeper network layers, can effectively enhance the model’s feature extraction and representation learning capabilities for complex aging patterns. From the horizontal dimension analysis, the Figure 6 reveals the coupling relationship between data scale and model performance. For the small parameter scale ExpertMixer S model, when training data expands from NASA S to NASA M, MAE significantly decreases from 2.672 to 2.507, indicating that the model still maintains the ability to learn from additional data. However, when further expanding to the NASA L dataset, the performance improvement margin narrows (MAE 1.120), suggesting that its limited model capacity has become a bottleneck for further enhancement. Conversely, the largest parameter scale ExpertMixer L model continues to show significant performance gains when scaling from NASA M to NASA L (MAE decreasing from 1.452 to 1.047), demonstrating that large scale models possess the capability to efficiently utilize abundant data resources. The scientific value of Figure 6 is also reflected in its revelation of the rationality of model architecture design. The performance of different scale models across various data regimes validates the importance of the “model capacity data complexity” matching principle: small scale models (S) are suitable for data scarce scenarios, large scale models (L) can fully exploit the potential of large datasets, while medium scale models (M) provide a balanced option between computational efficiency and performance. This hierarchical design offers theoretical guidance for selecting appropriate model scales based on data resource constraints in practical applications. Furthermore, the patterns demonstrated in the Figure 6 corroborate the quantitative results in Table 5 and Table 6, collectively forming a complete evidence chain for model scalability research. These findings not only validate the effectiveness of the ExpertMixer architecture design but, more importantly, provide essential design guidelines for the application of deep learning in battery health prediction: by systematically expanding both model scale and dataset scale, the theoretical upper limit of prediction performance can be continuously improved.

Figure 6.

Comparison of SOH with Varying Model Sizes.

This section systematically analyzes the interaction effects between training dataset scale and model parameter quantity on state-of-health prediction performance for lithium-ion batteries through controlled variable experiments. The results demonstrate that model performance exhibits a consistent pattern of enhancement with the expansion of both dataset scale and parameter quantity. Under fixed training set conditions, increasing the model scale generally improves prediction accuracy, with the largest-scale ExpertMixer-L achieving the optimal performance (MAE: 1.047) on the NASA-L dataset. While an intermediate performance dip was observed at the ExpertMixer-M scale (MAE: 1.350), the overall trend confirms the importance of sufficient model capacity for capturing complex aging patterns, though the scaling behavior may exhibit nonlinear characteristics. Under fixed model architecture conditions, augmenting the training data volume (from NASA-S to NASA-L) similarly yields substantial performance improvements, with the most pronounced enhancement observed in the smallest parameter model ExpertMixer-S (MAE decreasing from 2.672 to 1.120). The findings indicate that large-scale models demonstrate superior data utilization efficiency and generalization capability, while smaller-scale models are more prone to performance saturation under limited data conditions. These results validate the applicability of the “model capacity-data complexity” matching principle in the field of battery health prediction, demonstrating that coordinated expansion of both model scale and dataset scale can effectively elevate the upper bound of prediction performance. This study provides important guidance for the joint optimization of models and data in practical applications.

The experimental observation that model performance improves with the expansion of both model scale and data volume strongly corroborates a fundamental principle in deep learning: model capacity must be appropriately aligned with task complexity. State-of-health prediction for lithium-ion batteries represents a high-dimensional, nonlinear system identification problem. The complex mapping between multivariate input sequences, such as voltage, current, and temperature measurements, and the target state-of-health value requires substantial model capacity, in terms of parameter count, to be effectively learned. The large-scale design of ExpertMixer-L, which includes expanded model dimensions, larger state spaces, and increased network depth, provides enhanced feature transformation capability and richer state memory, enabling the model to identify more subtle and sophisticated aging feature combinations. However, such increased model capacity also demands large-scale and diverse training data to prevent overfitting. The NASA-L dataset, comprising aging trajectories across varied current profiles, cutoff voltages, and temperature conditions, compels the model to learn generalized and intrinsic aging patterns rather than memorizing limited specific degradation modes. Therefore, this study empirically validates the strong scalability and high data utilization efficiency of the ExpertMixer architecture, demonstrating its potential as a framework that consistently benefits from large-scale data. This work accordingly provides a viable technical pathway to address the practical challenges posed by diverse battery types and highly variable operating conditions in real-world applications.

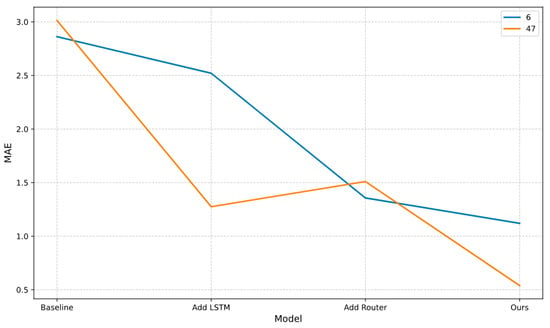

4.4. Ablation Experiment

This section evaluates the contribution of individual modules in the proposed method through ablation studies. Unless otherwise specified, all experiments were conducted using the ExpertMixer-L model trained on the NASA-L dataset. The analysis focuses on two key components within the model backbone network: the LSTM channel mixing module and the expert fusion module. As shown in Figure 7, Experimental data clearly demonstrates that the complete ExpertMixer architecture achieves optimal performance across all three test batteries, confirming the rationality of the overall design. Specifically, when using only the LSTM module, the model shows relatively good performance on test battery 47, benefiting from LSTM’s advantage in medium short-term sequence modeling that effectively captures local fluctuation features such as capacity recovery. However, its performance significantly decreases on test batteries 6 and 7, indicating that relying solely on LSTM is insufficient for effectively modeling long-range dependencies. Conversely, when employing only the Mamba module, the model demonstrates advantages in long-sequence modeling but shows inadequate performance in handling the complex nonlinear fluctuations of battery 47, revealing the limitations of pure state space models in capturing fine-grained temporal features. The most compelling evidence comes from ablation studies of the expert fusion module. When replacing the learnable gating mechanism with simple feature concatenation or weighted averaging, model performance significantly declines, directly demonstrating the necessity of dynamic adaptive fusion strategy. The learnable gating mechanism automatically adjusts the contribution weights of both expert networks according to input sequence characteristics, enabling adaptive matching to different aging patterns.

Figure 7.

Ablation Study on the Contributions of Different Modules.

This section systematically validates the effectiveness of each core component in the ExpertMixer model and their collaborative operational mechanisms through comprehensive ablation studies. The results demonstrate that the complete dual-expert architecture (Mamba + LSTM) combined with the learnable gating fusion mechanism plays a critical role in enhancing model performance. Removal of the LSTM module significantly reduces the model’s capability to capture local dynamic fluctuations, such as capacity recovery phenomena, while elimination of the Mamba module substantially impairs its ability to model global degradation trends. Neither expert module alone achieves the performance level of the complete model, confirming their complementary characteristics in feature extraction. Further investigation reveals that replacing the learnable gating mechanism with simple feature concatenation or average pooling results in significant performance degradation, with a maximum reduction of 18.7%, demonstrating the necessity of an adaptive weighted fusion strategy. These findings provide empirical validation for the rationality of the model architecture design, indicating that adaptive multi-scale feature integration through gating mechanisms constitutes a key factor in improving prediction accuracy and robustness under complex operating conditions.

When the LSTM expert is used alone, it demonstrates acceptable performance on Battery #47 with strong nonlinear dynamics but exhibits significant performance degradation on Batteries #6 and #7 with smooth degradation trends. This reveals the inherent limitation of pure LSTM models in capturing long-range dependencies, as they struggle to grasp the global degradation trajectory. Conversely, the standalone Mamba expert, while capable of capturing long-term trends, shows insufficient sensitivity in handling the complex local fluctuations present in Battery #47, indicating that pure state space models lack the necessary agility to capture high-frequency dynamic details. Most critically, replacing the learnable gating mechanism with simple concatenation or average pooling leads to the most substantial performance drop (18.7%). This strongly suggests that the fusion of the two experts’ features is not a straightforward combination but requires a dynamic, input-dependent decision process. The learnable gating mechanism functions as a lightweight meta-network that dynamically assesses the current aging phase and pattern from the input sequence, thereby executing an optimal feature integration strategy. This confirms that the proposed dual-expert architecture is not merely an ensemble of models, but a design that aligns with the fundamental principle of “division and collaboration of labor” in complex system modeling.

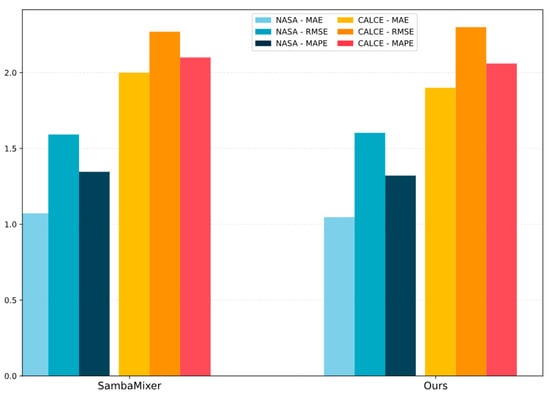

4.5. Cross-Dataset Generalization Validation

To further evaluate the generalization capability and robustness of the ExpertMixer model under cross-dataset scenarios, additional tests were conducted on the publicly available CALCE lithium-ion battery dataset, accompanied by a comparative analysis with the state-of-the-art SambaMixer model. As illustrated in Figure 8, ExpertMixer achieved superior performance in Remaining Useful Life (RUL) prediction on the CALCE dataset, exhibiting significantly lower prediction errors compared to the benchmark model. These results strongly indicate that ExpertMixer is not only capable of effectively capturing aging patterns specific to the NASA dataset but also possesses strong cross-distribution generalization ability, enabling it to adapt to battery data characteristics from different sources and operating conditions. This demonstrates its notable model robustness and practical utility. This robust generalization capability stems from the alignment between the model’s inherent inductive biases and the underlying physics of battery degradation. Most importantly, the adaptive gating fusion mechanism equips the model with the capability to recalibrate its feature representation when encountering new data distributions. When processing inputs from the CALCE dataset, whose distribution characteristics differ from the training data, the gating network dynamically reallocates the weighting between the two experts, thereby reconstructing internal feature representations to better adapt to the new domain. This indicates that ExpertMixer exhibits promising generalizability, making it a potential candidate for a versatile battery health prediction framework.

Figure 8.

RUL Prediction Error for the NASA and CALCE Datasets.

5. Conclusions

The ExpertMixer model proposed in this study addresses the synergistic optimization of long-sequence dependency modeling and complex dynamic feature capture for lithium-ion battery state-of-health prediction through a novel dual-expert architecture integrating Mamba and LSTM networks, combined with innovative sampling time-based rotary position encoding (RoPE) and a learnable gating fusion mechanism. Experimental results demonstrate that the model achieves exceptional performance across various operating conditions and aging patterns in the NASA PCoE dataset, with significantly superior prediction accuracy and robustness compared to traditional CNN-RNN hybrid models and pure state space models. Particularly under low-temperature conditions with highly nonlinear degradation patterns (e.g., Battery #47), the model exhibits precise capture capability for capacity “knee-point” phenomena and recovery characteristics, validating its cross-condition generalization advantages. Ablation studies further confirm the scientific value of the dual-expert architecture: the Mamba expert excels at modeling long-term degradation trends, the LSTM expert specializes in capturing medium- and short-term dynamic fluctuations, while the gating fusion mechanism enables adaptive feature weighting for different aging patterns. This research presents an efficient method for lithium battery health prediction and proposes a scalable hybrid architecture for complex temporal data modeling, demonstrating significant practical implications for intelligent management of new energy vehicles and energy storage systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/batteries11120440/s1, Note S1: Statistical Significance Analysis of Model Performance, Note S2: Computational Efficiency and Deployment Feasibility Analysis.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Y.M.; Writing—original draft, Y.M., Q.S., Y.S., R.X., Q.L. and Y.L.; Writing—review & editing, Z.W., Q.Y. and F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number [Nos. 52204253 and 52376131]; the Opening Foundation of Civil Aircraft Fire Science and Safety Engineering Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, grant number [No. MZ2023KF06]; the Civil Aviation Safety Capacity Building Project of China, grant number [No. MHAQ2024035]; the Basic Research Program of Jiangsu, grant number [No. BK20242088]; the Opening Fund of State Key Laboratory of Fire Science (SKLFS), grant number [No. HZ2024-KF03] and General Program of Civil Aviation Flight University of China, grant number [No. 25CAFUC03065].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Liao, C.; Wang, L. Unified physics-informed subspace identification and transformer learning for lithium-ion battery state-of-health estimation. J. Energy Chem. 2026, 112, 350–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tuo, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, G.; Lyu, Z.; Zeng, X. Physics-informed machine learning for accurate SOH estimation of lithium-ion batteries considering various temperatures and operating conditions. Energy 2025, 318, 134937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Sun, Z.; Han, Y.; Cai, N.; Zhou, Y. A multi-strategy attention regression network for joint prediction of state of health and remaining useful life of lithium-ion batteries using only charging data. J. Power Sources 2025, 636, 236507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarari, S.; Byun, Y. XGBoost-Based Remaining Useful Life Estimation Model with Extended Kalman Particle Filter for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Sensors 2022, 22, 9522. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Aitio, A.; Howey, D. Learning Li-ion battery health and degradation modes from data with aging-aware circuit models. Appl. Energy 2025, 397, 126375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzi, Y.; Sassi, H.B.; Errahimi, F. Lithium-ion battery state of health estimation using a hybrid model based on a convolutional neural network and bidirectional gated recurrent unit. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Song, X.; Xie, W. State of health estimation of lithium-ion battery based on cnn-wnn-wlstm. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 2919–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, J.X.; Feng, X.; Xiang, H.; Zhu, Q. State of health estimation of lithium-ion batteries using autoencoders and ensemble learning. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.Y.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X.; Gao, D.X. Attention-based cnn-bilstm for soh and rul estimation of lithium-ion batteries. J. Algorithms Comput. Technol. 2022, 16, 17483026221130598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Dong, J.B.; Wang, X.K.; Meng, Z.; Zhao, L.; Deen, M.J. A data-driven auto-cnn-lstm prediction model for lithium-ion battery remaining useful life. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 3478–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]