Precisely Engineering Interfaces for High-Energy Rechargeable Lithium Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

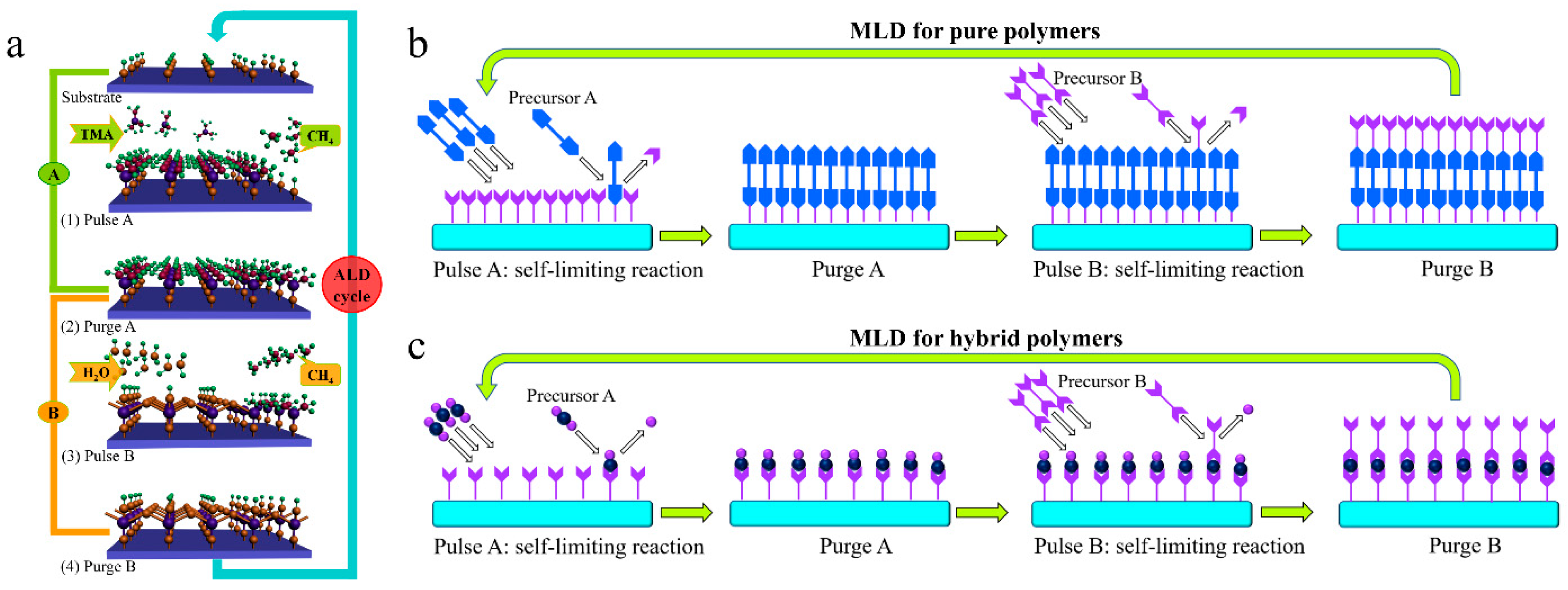

2. The Principle and Growth Mechanism of ALD and MLD

2.1. The Basics of ALD and MLD

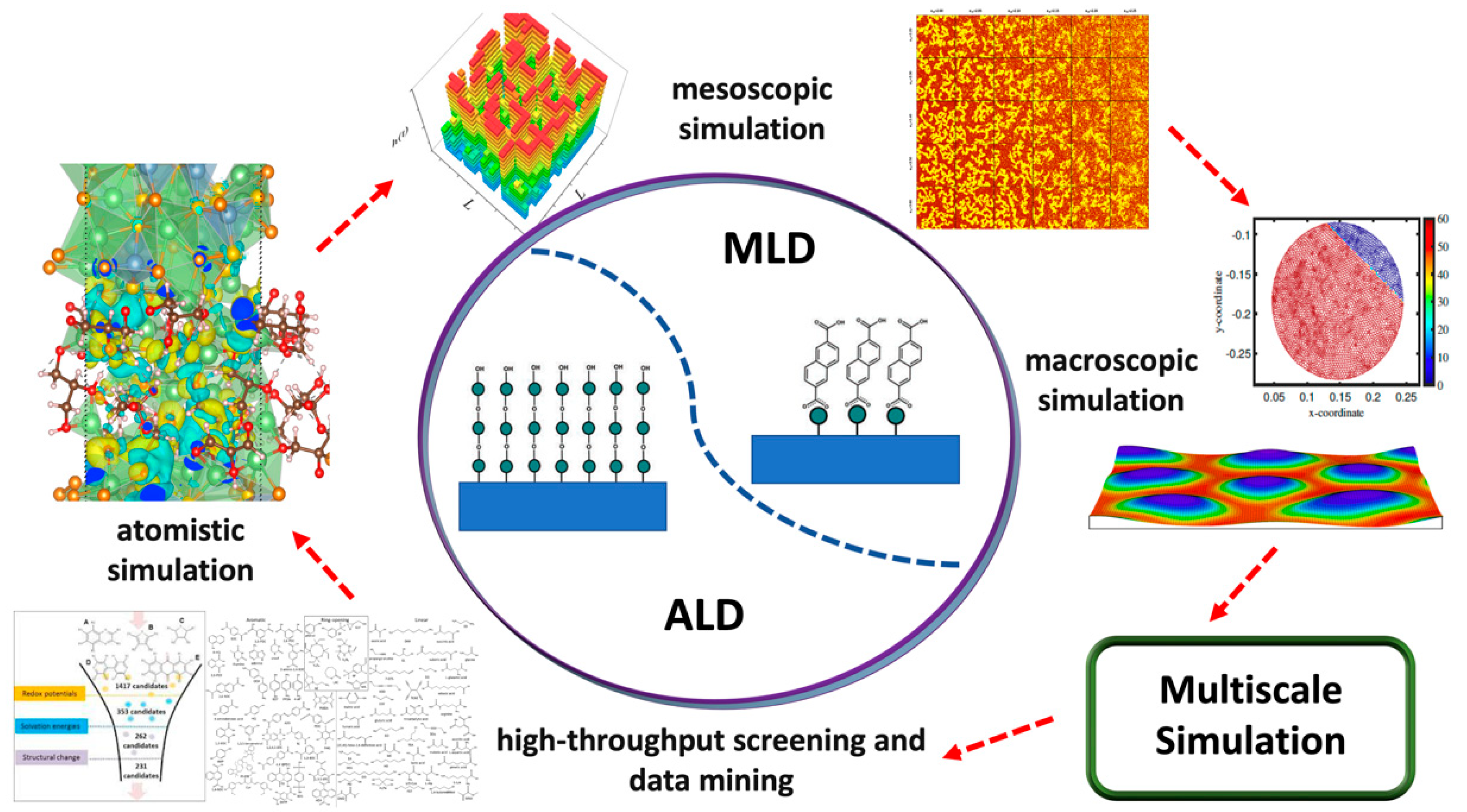

2.2. Theoretical Studies

3. Accurately Engineering Interfaces of LIBs and Beyond

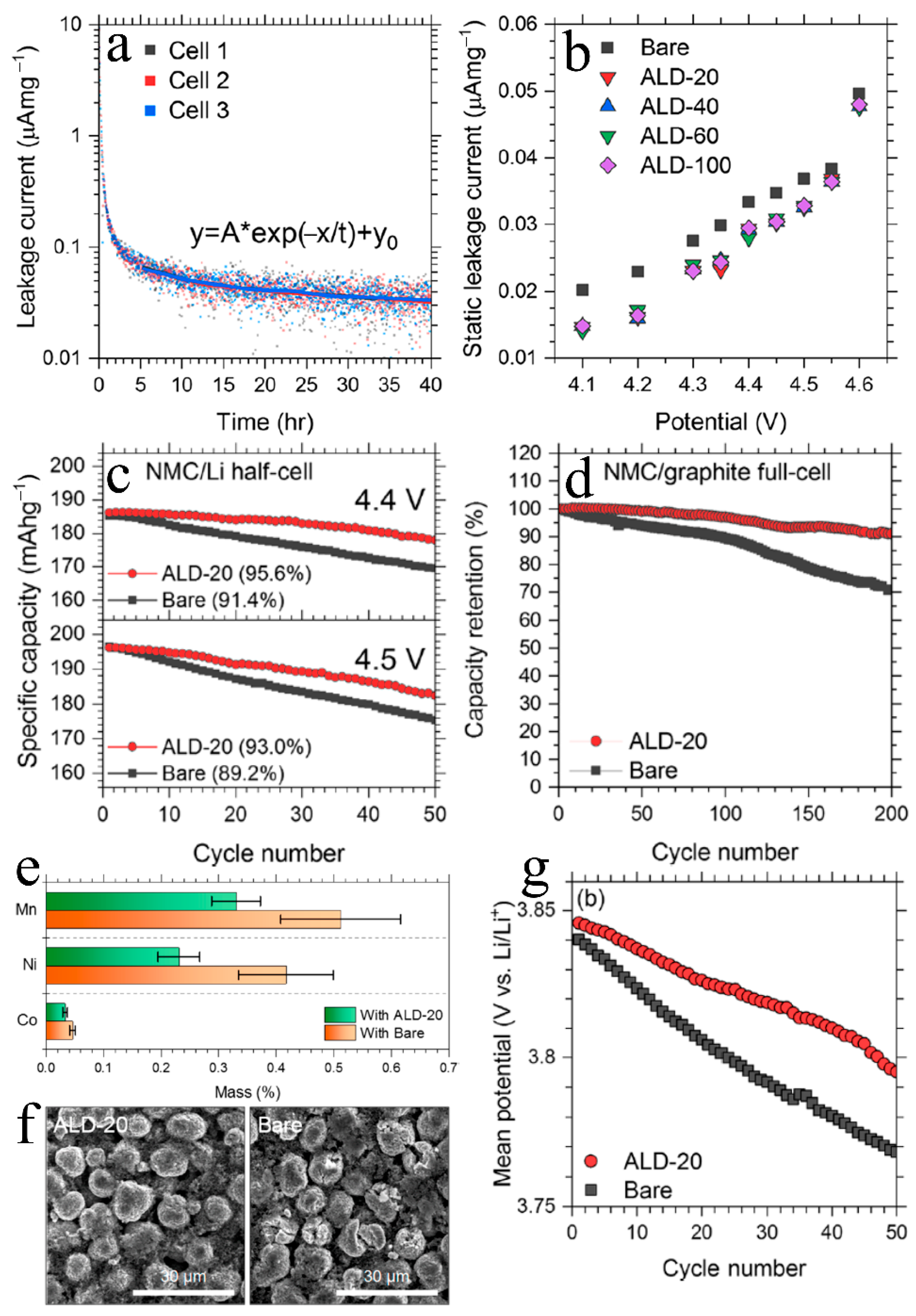

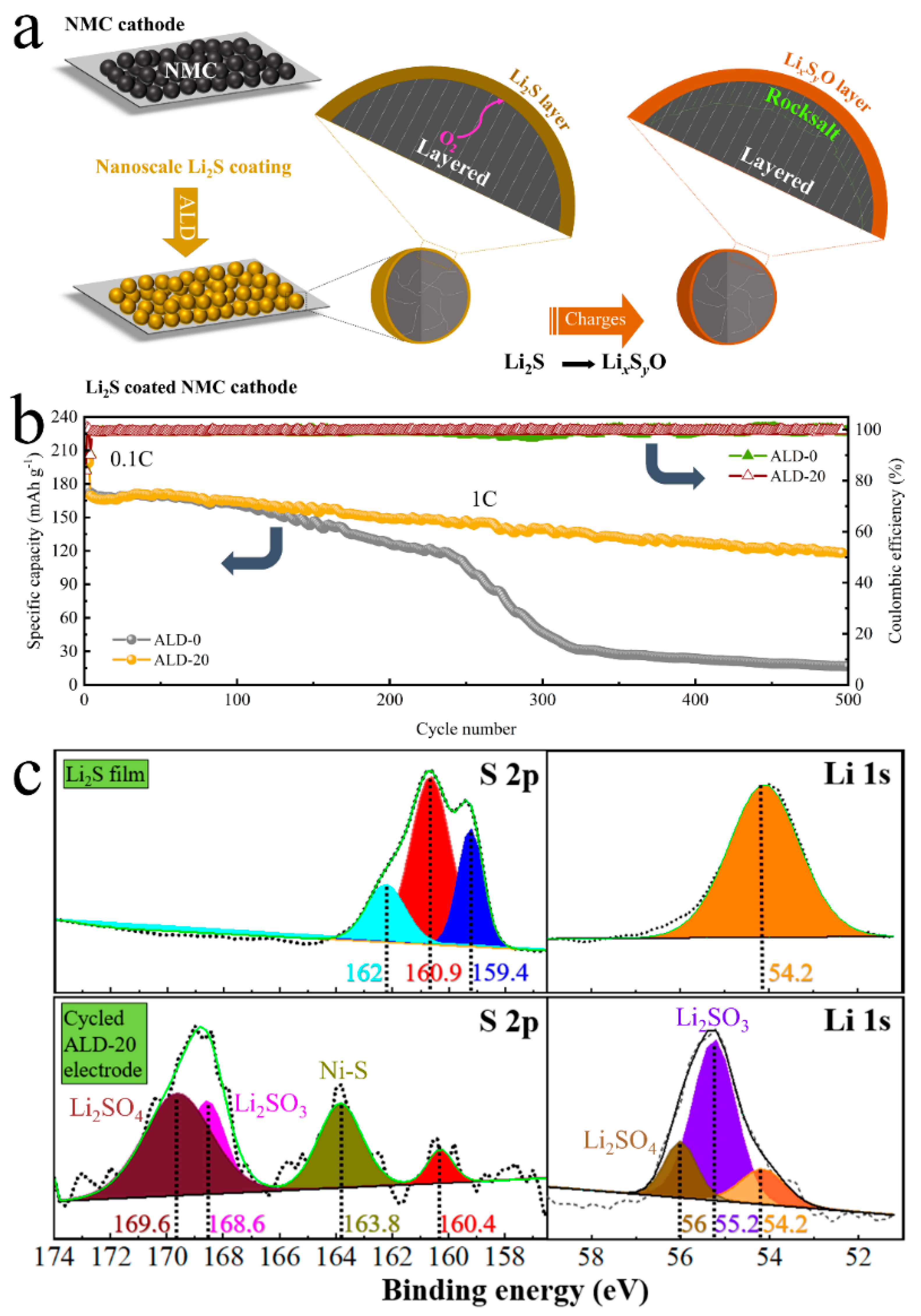

3.1. The Cathode/Electrolyte Interfaces

ALD Cathode Modeling

3.2. The ALD/Anode Interfaces

3.2.1. Si Anodes

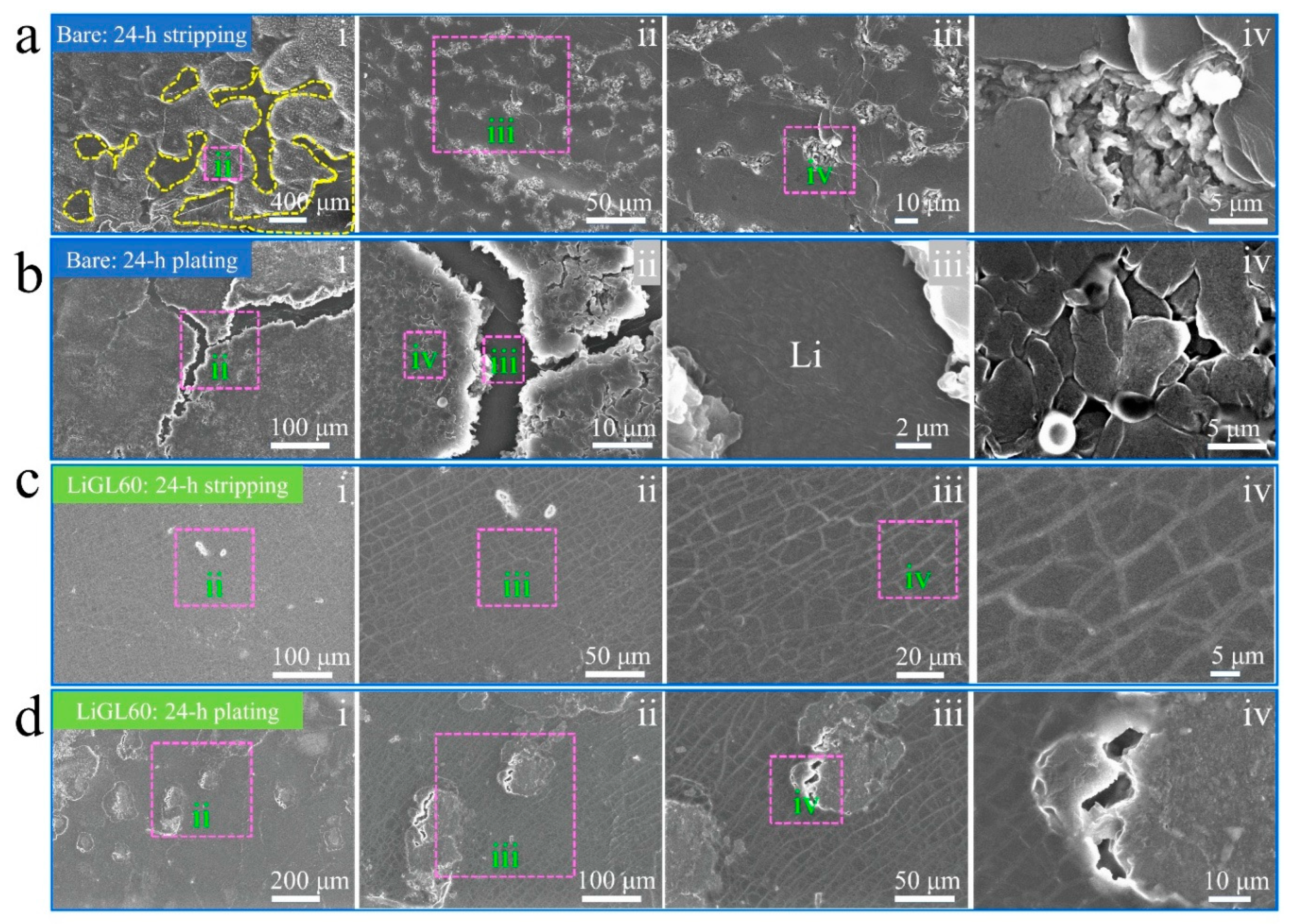

3.2.2. Li-Metal Anodes

3.3. Anode Interface Modeling

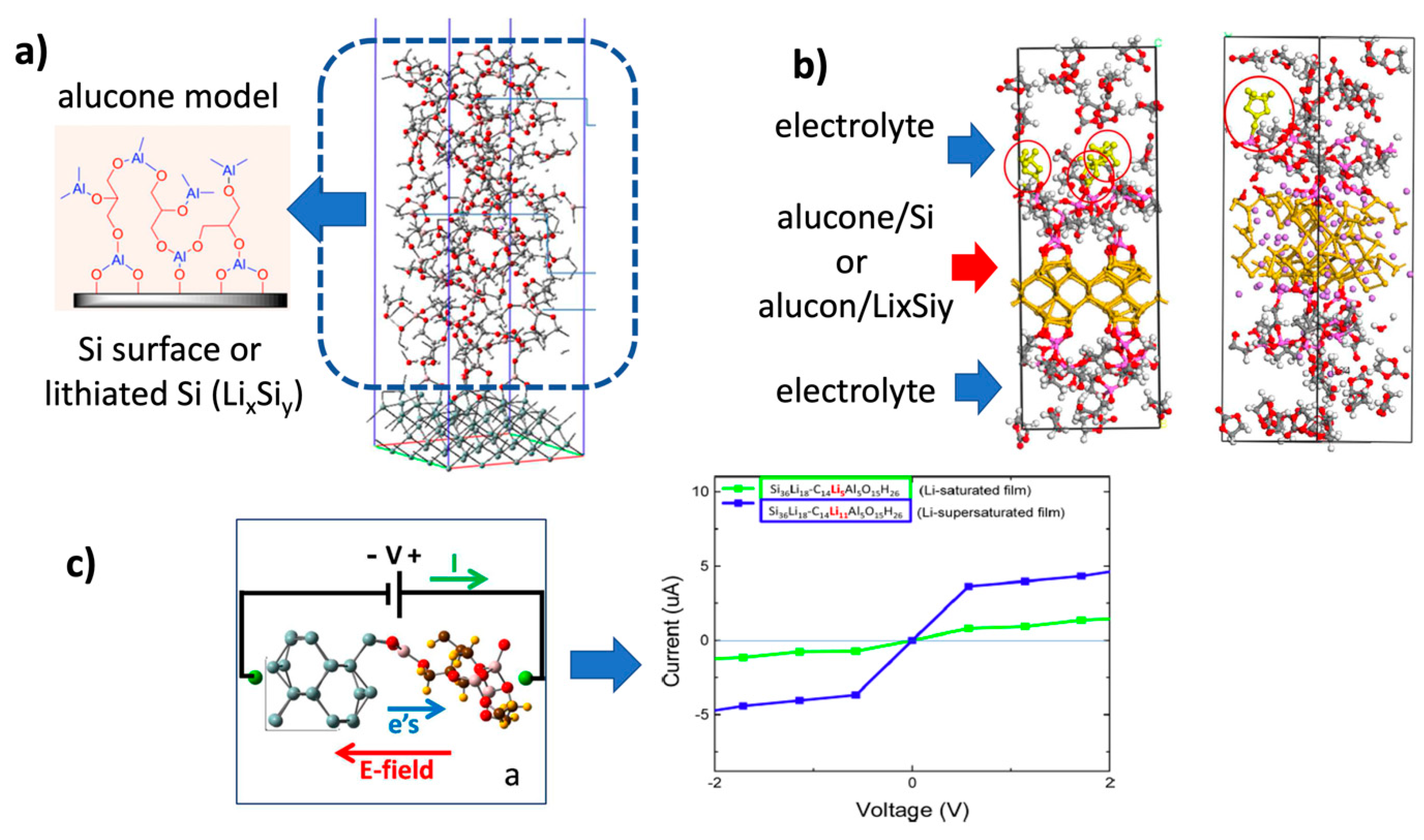

3.3.1. MLD-Si Anode Modeling

3.3.2. MLD-Li Anode Modeling

4. Conclusions and Outlook

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- George, S.M. Atomic layer deposition: An overview. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuiykov, S.; Akbari, M.K.; Hai, Z.; Xue, C.; Xu, H.; Hyde, L. Wafer-scale fabrication of conformal atomic-layered TiO2 by atomic layer deposition using tetrakis(dimethylamino)titanium and H2O precursors. Mater. Des. 2017, 120, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayle, A.J.; Berquist, Z.J.; Chen, Y.; Hill, A.J.; Hoffman, J.Y.; Bielinski, A.R.; Lenert, A.; Dasgupta, N.P. Tunable Atomic Layer Deposition into Ultra-High-Aspect-Ratio (>60,000:1) Aerogel Monoliths Enabled by Transport Modeling. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 5572–5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Ma, Z.; Wejinya, U.; Zou, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Meng, X. A revisit to atomic layer deposition of zinc oxide using diethylzinc and water as precursors. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 5236–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putkonen, M.; Niinistö, L. Atomic layer deposition of B2O3 thin films at room temperature. Thin Solid. Film. 2006, 514, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yang, X.Q.; Sun, X.L. Emerging applications of atomic layer deposition for lithium-ion battery studies. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 3589–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. An overview of molecular layer deposition for organic and organic-inorganic hybrid materials: Mechanisms, growth characteristics, and promising applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 18326–18378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Han, K.; Geng, D.; Ye, H.; Meng, X. Achieving high-performance silicon anodes of lithium-ion batteries via atomic and molecular layer deposited surface coatings: An overview. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 251, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, X.-B. Surface modifications of layered LiNixMnyCozO2 cathodes via atomic and molecular layer deposition. Rare Met. 2023, 42, 2121–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Atomic layer deposition of solid-state electrolytes for next-generation lithium-ion batteries and beyond: Opportunities and challenges. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 30, 296–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Banis, M.N.; Liang, J.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Adair, K.R.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. Manipulating Interfacial Nanostructure to Achieve High-Performance All-Solid-State Lithium-Ion Batteries. Small Methods 2019, 3, 1900261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamalainen, J.; Holopainen, J.; Munnik, F.; Hatanpaa, T.; Heikkila, M.; Ritala, M.; Leskela, M. Lithium phosphate thin films grown by atomic layer deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, A259–A263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hong, J.; Park, K.-Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.-W.; Kang, K. Aqueous Rechargeable Li and Na Ion Batteries. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11788–11827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Meng, X.; Elam, J.W. Atomic layer deposition of LixAlyS solid-state electrolytes for stabilizing lithium-metal anodes. ChemElectroChem 2016, 3, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.A.; Carballo, K.V.; Koirala, K.P.; Zhao, Q.; Gao, P.; Kim, J.-M.; Anderson, C.S.; Meng, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.-G.; et al. Lithicone-Protected Lithium Metal Anodes for Lithium Metal Batteries with Nickel-Rich Cathode Materials. Small Struct. 2024, 5, 2400174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lau, K.C.; Zhou, H.; Ghosh, S.K.; Benamara, M.; Zou, M. Molecular Layer Deposition of Crosslinked Polymeric Lithicone for Superior Lithium Metal Anodes. Energy Mater. Adv. 2021, 2021, 9786201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Velasquez Carballo, K.; Watanabe, F.; Meng, X. Tackling issues of lithium metal anodes with a novel polymeric lithicone coating. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 475, 146156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Velasquez Carballo, K.; Shao, A.; Cai, J.; Watanabe, F.; Meng, X. A novel polymeric lithicone coating for superior lithium metal anodes. Nano Energy 2024, 128, 109840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Interface engineering of lithium metal anodes via atomic and molecular layer deposition. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 659–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, Z. Constituting robust interfaces for better lithium-ion batteries and beyond using atomic and molecular layer deposition. In Encyclopedia of Nanomaterials, 1st ed.; Yin, Y., Lu, Y., Xia, Y., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 649–663. [Google Scholar]

- Miikkulainen, V.; Leskelä, M.; Ritala, M.; Puurunen, R.L. Crystallinity of inorganic films grown by atomic layer deposition: Overview and general trends. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 021301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puurunen, R.L. Surface chemistry of atomic layer deposition: A case study for the trimethylaluminum/water process. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 121301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.-I.; Umemoto, S.; Kikutani, T.; Okui, N. Layer-by-layer polycondensation of nylon 66 by alternating vapour deposition polymerization. Polymer 1997, 38, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; George, S.M. Molecular layer deposition of nylon 66 films examined using in situ FTIR spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 8509–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.; Tatsuura, S.; Sotoyama, W.; Matsuura, A.; Hayano, T. Quantum wire and dot formation by chemical vapor deposition and molecular layer deposition of one-dimensional conjugated polymer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1992, 60, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.; Oshima, A.; Kim, D.-I.; Morita, Y. Quantum dot formation in polymer wires by three-molecule molecular layer deposition (MLD) and applications to electro-optic/photovoltaic devices. ECS Trans. 2009, 25, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.; Ebihara, R.; Oshima, A. Polymer wires with quantum dots grown by molecular layer deposition of three source molecules for sensitized photovoltaics. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2011, 29, 051510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.; Ishii, S. Effect of quantum dot length on the degree of electron localization in polymer wires grown by molecular layer deposition. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2013, 31, 031501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Filler, M.A.; Kim, S.; Bent, S.F. Layer-by-layer growth on Ge(100) via spontaneous urea coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6123–6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loscutoff, P.W.; Zhou, H.; Clendenning, S.B.; Bent, S.F. Formation of organic nanoscale laminates and blends by molecular layer deposition. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Bent, S.F. Molecular layer deposition of functional thin films for advanced lithographic patterning. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Toney, M.F.; Bent, S.F. Cross-linked ultrathin polyurea films via molecular layer deposition. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 5638–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-S.; Choi, S.-E.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.S. Fine-tunable absorption of uniformly aligned polyurea thin films for optical filters using sequentially self-limited molecular layer deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 11788–11795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, S.E.; Losego, M.D.; Gong, B.; Sachet, E.; Maria, J.-P.; Williams, P.S.; Parsons, G.N. Highly conductive and conformal poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) thin films via oxidative molecular layer deposition. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 3471–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Atanasov, S.E.; Lemaire, P.; Lee, K.; Parsons, G.N. Platinum-free cathode for dye-sensitized solar cells using poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) formed via oxidative molecular layer deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 3866–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamae, T.; Tsukagoshi, K.; Matsuoka, O.; Yamamoto, S.; Nozoye, H. Preparation of polyimide-polyamide random copolymer thin film by sequential vapor deposition polymerization. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 41, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscutoff, P.W.; Lee, H.-B.-R.; Bent, S.F. Deposition of ultrathin polythiourea films by molecular layer deposition. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 5563–5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.V.; Maydannik, P.S.; Cameron, D.C. Molecular layer deposition of polyethylene terephthalate thin films. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2012, 30, 01A121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, L.D.; Heikkilä, M.J.; Puukilainen, E.; Sajavaara, T.; Grosso, D.; Ritala, M. Studies on atomic layer deposition of MOF-5 thin films. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 182, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, M.Q.; Trebukhova, S.A.; Ravdel, B.; Wheeler, M.C.; DiCarlo, J.; Tripp, C.P.; DeSisto, W.J. Synthesis and characterization of atomic layer deposited titanium nitride thin films on lithium titanate spinel powder as a lithium-ion battery anode. J. Power Sources 2007, 165, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Cavanagh, A.S.; Dillon, A.C.; Groner, M.D.; George, S.M.; Lee, S.H. Enhanced stability of LiCoO2 cathodes in lithium-ion batteries using surface modification by atomic layer deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, A75–A81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Cavanagh, A.S.; Riley, L.A.; Kang, S.H.; Dillon, A.C.; Groner, M.D.; George, S.M.; Lee, S.H. Ultrathin direct atomic layer deposition on composite electrodes for highly durable and safe Li-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2172–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Meng, X.; Tang, Y.; Banis, M.N.; Yang, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, R.; Cai, M.; Sun, X. Significant impact on cathode performance of lithium-ion batteries by precisely controlled metal oxide nanocoatings via atomic layer deposition. J. Power Sources 2014, 247, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X. Inhibiting Sulfur Shuttle Behaviors in High-Energy Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. U.S. Patent 62/471161, 14 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Cai, J.; Xu, G.-L.; Li, L.; Ren, Y.; Meng, X.; Amine, K.; Chen, Z. Surface modification for suppressing interfacial parasitic reactions of a nickel-rich lithium-ion cathode. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 2723–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Sendek, A.D.; Cubuk, E.D.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Wu, T.; Shi, F.; Liu, W.; Reed, E.J.; et al. Atomic layer deposition of stable LiAlF4 lithium ion conductive interfacial layer for stable cathode cycling. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 7019–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, A.; Tiurin, O.; Solomatin, N.; Auinat, M.; Meitav, A.; Ein-Eli, Y. Robust AlF3 Atomic Layer Deposition Protective Coating on LiMn1.5Ni0.5O4 Particles: An Advanced Li-Ion Battery Cathode Material Powder. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 6809–6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Wang, B.; Liu, J.; Kaliyappan, K.; Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dadheech, G.; Balogh, M.P.; Yang, L.; Sham, T.-K.; et al. Highly stable Li1.2Mn0.54Co0.13Ni0.13O2 enabled by novel atomic layer deposited AlPO4 coating. Nano Energy 2017, 34, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-F.; Fan, X.; Pearse, A.; Liou, S.-C.; Gregorczyk, K.; Leskes, M.; Wang, C.; Lee, S.B.; Rubloff, G.W.; Noked, M. Highly Reversible Conversion-Type FeOF Composite Electrode with Extended Lithium Insertion by Atomic Layer Deposition LiPON Protection. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 8780–8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, J.T.; Lee, D.C.; Magasinski, A.; Cho, W.I.; Yushin, G. Plasma-Enhanced Atomic Layer Deposition of Ultrathin Oxide Coatings for Stabilized Lithium-Sulfur Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2013, 3, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Comstock, D.J.; Fister, T.T.; Elam, J.W. Vapor-phase atomic-controllable growth of amorphous Li2S for high-performance lithium–sulfur batteries. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 10963–10972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lei, Y.; Lau, K.C.; Luo, X.; Du, P.; Wen, J.; Assary, R.S.; Das, U.; Miller, D.J.; Elam, J.W.; et al. A nanostructured cathode architecture for low charge overpotential in lithium-oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.-S.; Li, H.; Zhou, Z.; Armand, M.; Chen, L. Disodium Terephthalate (Na2C8H4O4) as High Performance Anode Material for Low-Cost Room-Temperature Sodium-Ion Battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppert, N.D.; Mukherjee, S.; Bates, A.M.; Son, E.-J.; Choi, M.J.; Park, S. Ex-situ X-ray diffraction analysis of electrode strain at TiO2 atomic layer deposition/α-MoO3 interface in a novel aqueous potassium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2016, 316, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wang, C.; Yu, Y.; Yan, M.; Wei, Q.; He, P.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Mai, L. Ultrathin Surface Coating Enables Stabilized Zinc Metal Anode. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 5, 1800848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Mathur, A.; Singh, A.; Pakhira, S.; Singh, R.; Chattopadhyay, S. Binder-Free ZnO Cathode synthesized via ALD by Direct Growth of Hierarchical ZnO Nanostructure on Current Collector for High-Performance Rechargeable Aluminium-Ion Batteries. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 12512–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebl, A.J.; Oldham, C.J.; Devine, C.K.; Gong, B.; Atanasov, S.E.; Parsons, G.N.; Fedkiw, P.S. Solid Electrolyte Interphase on Lithium-Ion Carbon Nanofiber Electrodes by Atomic and Molecular Layer Deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, A1971–A1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, D.M.; Travis, J.J.; Young, M.; Son, S.-B.; Kim, S.C.; Oh, K.H.; George, S.M.; Ban, C.; Lee, S.-H. Reversible high-capacity Si nanocomposite anodes for lithium-ion batteries enabled by molecular layer deposition. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Goncharova, L.V.; Sun, Q.; Li, X.; Lushington, A.; Wang, B.; Li, R.; Dai, F.; Cai, M.; Sun, X. Robust metallic lithium anode protection by the molecular-layer-deposition technique. Small Methods 2018, 2, 1700417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Goncharova, L.V.; Zhang, Q.; Kaghazchi, P.; Sun, Q.; Lushington, A.; Wang, B.; Li, R.; Sun, X. Inorganic–Organic Coating via Molecular Layer Deposition Enables Long Life Sodium Metal Anode. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 5653–5659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliyappan, K.; Or, T.; Deng, Y.-P.; Hu, Y.; Bai, Z.; Chen, Z. Constructing Safe and Durable High-Voltage P2 Layered Cathodes for Sodium Ion Batteries Enabled by Molecular Layer Deposition of Alucone. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multia, J.; Karppinen, M. Atomic/Molecular Layer Deposition for Designer’s Functional Metal–Organic Materials. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bui, H.; Grillo, F.; van Ommen, J.R. Atomic and molecular layer deposition: Off the beaten track. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Wang, H.; Tom, M.; Ou, F.; Orkoulas, G.; Christofides, P.D. Multiscale CFD Modeling of Area-Selective Atomic Layer Deposition: Application to Reactor Design and Operating Condition Calculation. Coatings 2023, 13, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Dai, Z.; Yang, F.; Wen, Y.; Shan, B.; Chen, R. Multiscale CFD modelling for conformal atomic layer deposition in high aspect ratio nanostructures. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Ou, F.; Wang, H.; Tom, M.; Orkoulas, G.; Christofides, P.D. Atomistic-mesoscopic modeling of area-selective thermal atomic layer deposition. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 188, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, N.E.; de Paula, C.; Bent, S.F. Understanding chemical and physical mechanisms in atomic layer deposition. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 040902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibanda, D.; Oyinbo, S.T.; Jen, T.-C. A review of atomic layer deposition modelling and simulation methodologies: Density functional theory and molecular dynamics. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2022, 11, 1332–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romine, D.; Sakidja, R. Modeling atomic layer deposition of alumina using reactive force field molecular dynamics. MRS Adv. 2022, 7, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezsevin, I.; Deijkers, J.H.; Merkx, M.J.M.; Kessels, W.M.M.; Sandoval, T.E.; Mackus, A.J.M. The Consequences of Random Sequential Adsorption for the Precursor Packing and Growth-Per-Cycle of Atomic Layer Deposition Processes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2024, 15, 7496–7501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Rothman, A.; Shearer, A.B.; Bent, S.F. Molecular Design in Area-Selective Atomic Layer Deposition: Understanding Inhibitors and Precursors. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 1741–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, X.; Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X. Atomic-scale constituting stable interface for improved LiNi0.6Mn0.2Co0.2O2 cathodes of lithium-ion batteries. Nanotechnology 2021, 32, 115401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Han, X.; Geng, D.; Li, J.; Meng, X. Atomic-scale tuned interface of nickel-rich cathode for enhanced electrochemical performance in lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ghosh, S.K.; Afshar-Mohajer, M.; Zhou, H.; Liu, Y.; Han, X.; Cai, J.; Zou, M.; Meng, X. Atomic layer deposition of zirconium oxide thin films. J. Mater. Res. 2019, 35, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.H.K.; Laskar, M.R.; Fang, S.; Xu, S.; Ellis, R.G.; Li, X.; Dreibelbis, M.; Babcock, S.E.; Mahanthappa, M.K.; Morgan, D. Optimizing AlF3 atomic layer deposition using trimethylaluminum and TaF5: Application to high voltage Li-ion battery cathodes. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 2016, 34, 031503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, A.; Choudhury, D.; Sharifi-Asl, S.; Yonemoto, B.T.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R.; Mane, A.U.; Elam, J.W.; Croy, J. Multifunctional Films Deposited by Atomic Layer Deposition for Tailored Interfaces of Electrochemical Systems. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 140541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Zheng, F.; Shen, L.; Dang, M.; Zhang, J. Coating ultra-thin TiN layer onto LiNi0. 8Co0. 1Mn0. 1O2 cathode material by atomic layer deposition for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 888, 161594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderick, L.; Hamed, H.; Mattelaer, F.; Minjauw, M.; Meersschaut, J.; Dendooven, J.; Safari, M.; Vereecken, P.; Detavernier, C. Atomic Layer Deposition of Nitrogen-Doped Al Phosphate Coatings for Li-Ion Battery Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 25949–25960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Ghosh, S.K.; Zou, M.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, X.; Meng, X. Atomic layer deposition of lithium zirconium oxides for the improved performance of lithium-ion batteries. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 2737–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, S.; Wolverton, C. Lithium Transport in Amorphous Al2O3 and AlF3 for Discovery of Battery Coatings. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 8009–8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, A.M.; Wickramaratne, D.; Bernstein, N.; Mo, Y.; Johannes, M.D. Li+ Diffusion in Amorphous and Crystalline Al2O3 for Battery Electrode Coatings. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 7795–7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Zheng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.-G. Tailoring grain boundary structures and chemistry of Ni-rich layered cathodes for enhanced cycle stability of lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zheng, J.; Lu, J.; Li, Y.; Yan, P.; Zhang, Y. Realizing superior cycling stability of Ni-Rich layered cathode by combination of grain boundary engineering and surface coating. Nano Energy 2019, 62, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhou, C.G.; Xie, M.; Hu, T.; Sun, H.T.; Xin, G.Q.; Wang, G.K.; George, S.M.; Lian, J. Amorphous vanadium oxide coating on graphene by atomic layer deposition for stable high energy lithium ion anodes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 10703–10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, J.A.; Becker, A.; Kanhaiya, K.; Heinz, H.; Weimer, A.W. Analyzing the Li–Al–O Interphase of Atomic Layer-Deposited Al2O3 Films on Layered Oxide Cathodes Using Atomistic Simulations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 1861–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, A.S.; Lee, Y.; Yoon, B.; George, S.M. Atomic layer deposition of LiOH and Li2CO3 using lithium t-butoxide as the lithium source. ECS Trans. 2010, 33, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cai, J.; Ren, Y.; Benamara, M.; Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, H.; Xiao, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. High-performance LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 cathode by nanoscale lithium sulfide coating via atomic layer deposition. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 69, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahaliabadeh, Z.; Miikkulainen, V.; Mäntymäki, M.; Colalongo, M.; Mousavihashemi, S.; Yao, L.; Jiang, H.; Lahtinen, J.; Kankaanpää, T.; Kallio, T. Stabilized Nickel-Rich-Layered Oxide Electrodes for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Environ. Mater. 2024, 7, e12741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Qi, Y.; Zavadil, K.R.; Jung, Y.S.; Dillon, A.C.; Cavanagh, A.S.; Lee, S.-H.; George, S.M. Using Atomic Layer Deposition to Hinder Solvent Decomposition in Lithium Ion Batteries: First-Principles Modeling and Experimental Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14741–14754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K. First-Principles Modeling of Mn(II) Migration above and Dissolution from LixMn2O4 Surfaces. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 2550–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haworth, A.R.; Johnston, B.I.J.; Wheatcroft, L.; McKinney, S.L.; Tapia-Ruiz, N.; Booth, S.G.; Nedoma, A.J.; Cussen, S.A.; Griffin, J.M. Structural Insight into Protective Alumina Coatings for Layered Li-Ion Cathode Materials by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 7171–7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Qiao, L.; Zhou, H.; Tang, Y.; Wahila, M.J.; Liu, H.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G.; Smeu, M.; Liu, H. Efficacy of atomic layer deposition of Al2O3 on composite LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 electrode for Li-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.L.B.; Sayed, F.N.; Banerjee, H.; Temprano, I.; Wan, J.; Morris, A.J.; Grey, C.P. Identification of the dual roles of Al2O3 coatings on NMC811-cathodes via theory and experiment. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Pham, H.; Liang, X.; Park, J. The role of atomic layer deposited coatings on lithium-ion transport: A comprehensive study. J. Power Sources 2023, 586, 233682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, J.-D.; Yao, H.-B.; Jiang, B. Size dependent lithium-ion conductivity of solid electrolytes in machine learning molecular dynamics simulations. Artif. Intell. Chem. 2024, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, Z. Computational Design of Inorganic Solid-State Electrolyte Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Acc. Mater. Res. 2024, 5, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.R.; Honrao, S.J.; Lawson, J.W. High-Throughput Screening of Li Solid-State Electrolytes with Bond Valence Methods and Machine Learning. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 9320–9329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Jun, B.; Jung, Y. Reliable Li-ion conductivity with efficient data generation and uncertainty estimation toward large-scale screening. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 163847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfir, M.R.; Nguyen, H.T.; Moyen, E.; Lee, Y.H.; Pribat, D. Silicon nanowires for Li-based battery anodes: A review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9566–9586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-M.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.; Sohn, H.-J. Li-alloy based anode materials for Li secondary batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3115–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Qin, L.; Wu, K.; Hui, L.; Gong, T.; Li, D.; Hu, Y.; Li, A.; et al. Molecular layer deposited mechanically and chemically robust niobicone interface empowering silicon nanowire anodes with competent cyclabilities. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 484, 149387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallas, J.M.; Welch, B.C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Hafner, S.E.; Qiao, R.; Yoon, T.; Cheng, Y.-T.; George, S.M.; Ban, C. Spatial Molecular Layer Deposition of Ultrathin Polyamide To Stabilize Silicon Anodes in Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 4135–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Ding, F.; Chen, X.; Nasybulin, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.-G. Lithium metal anodes for rechargeable batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 513–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozen, A.C.; Lin, C.-F.; Pearse, A.J.; Schroeder, M.A.; Han, X.; Hu, L.; Lee, S.-B.; Rubloff, G.W.; Noked, M. Next-generation lithium metal anode engineering via atomic layer deposition. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 5884–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaboina, P.K.; Rodrigues, S.; Rottmayer, M.; Cho, S.-J. In Situ Dendrite Suppression Study of Nanolayer Encapsulated Li Metal Enabled by Zirconia Atomic Layer Deposition. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 32801–32808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Cheng, X.; Cao, T.; Niu, J.; Wu, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y. Constructing ultrathin TiO2 protection layers via atomic layer deposition for stable lithium metal anode cycling. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 865, 158748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, K.-S.; Chen, X.; Ramirez, G.; Huang, Z.; Geise, N.R.; Steinrück, H.-G.; Fisher, B.L.; Shahbazian-Yassar, R.; Toney, M.F.; et al. Novel ALD Chemistry Enabled Low-Temperature Synthesis of Lithium Fluoride Coatings for Durable Lithium Anodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 26972–26981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Wang, M.; Cao, T.; Cheng, X.; Wu, R.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Li metal coated with Li3PO4 film via atomic layer deposition as battery anode. Ionics 2021, 27, 2445–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Cao, Y.; Libera, J.A.; Elam, J.W. Atomic layer deposition of aluminum sulfide: Growth mechanism and electrochemical evaluation in lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 9043–9052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.L.; Zavadil, K.R.; Hahn, N.T.; Meng, X.; Elam, J.W.; Leenheer, A.; Zhang, J.-G.; Jungjohann, K.L. Lithium self-discharge and its prevention: Direct visualization through in situ electrochemical scanning transmission electron microscopy. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11194–11205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liang, J.; Wang, C.; Sun, Q.; Lin, X.; Adair, K.R.; Luo, J.; Wang, D.; et al. A novel organic “polyurea” thin film for ultralong-life lithium-metal anodes via molecular-layer deposition. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Amirmaleki, M.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, C.; Codirenzi, A.; Goncharova, L.V.; Wang, C.; Adair, K.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; et al. Natural SEI-inspired dual-protective layers via atomic/molecular layer deposition for long-life metallic lithium anode. Matter 2019, 1, 1215–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, F.A.; Martinez de la Hoz, J.M.; Seminario, J.M.; Balbuena, P.B. Modeling solid-electrolyte interfacial phenomena in silicon anodes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2016, 13, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, L.; Cristancho, D.; Seminario, J.M.; Martinez de la Hoz, J.M.; Balbuena, P.B. Electron transfer through solid-electrolyte-interphase layers formed on Si anodes of Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 140, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzi, E.; M R, A.K.; Li, X.; Deng, S.; Nanda, J.; Zaghib, K. A comprehensive review of silicon anodes for high-energy lithium-ion batteries: Challenges, latest developments, and perspectives. Next Energy 2024, 5, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Kadam, S.; Li, H.; Shi, S.; Qi, Y. Review on modeling of the anode solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) for lithium-ion batteries. npj Comput. Mater. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Martinez de la Hoz, J.M.; Angarita, I.; Berrio-Sanchez, J.M.; Benitez, L.; Seminario, J.M.; Son, S.-B.; Lee, S.-H.; George, S.M.; Ban, C.; et al. Structure and Reactivity of Alucone-Coated Films on Si and LixSiy Surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 11948–11955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Balbuena, P.B.; Budzien, J.; Leung, K. Hybrid DFT Functional-Based Static and Molecular Dynamics Studies of Excess Electron in Liquid Ethylene Carbonate. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Forero, L.E.; Smith, T.W.; Balbuena, P.B. Effects of High and Low Salt Concentration in Electrolytes at Lithium–Metal Anode Surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Budzien, J.L. Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations of the initial stages of solid–electrolyte interphase formation on lithium ion battery graphitic anodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 6583–6586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K. Two-electron reduction of ethylene carbonate: A quantum chemistry re-examination of mechanisms. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013, 568, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadi, M.; Brandell, D.; Araujo, C.M. Electrolyte decomposition on Li-metal surfaces from first-principles theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 204701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Forero, L.E.; Smith, T.W.; Bertolini, S.; Balbuena, P.B. Reactivity at the Lithium–Metal Anode Surface of Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 26828–26839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, M.M.; Wolverton, C.; Isaacs, E.D. Electrical energy storage for transportation—Approaching the limits of, and going beyond, lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 7854–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saal, J.E.; Kirklin, S.; Aykol, M.; Meredig, B.; Wolverton, C. Materials Design and Discovery with High-Throughput Density Functional Theory: The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD). JOM 2013, 65, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykol, M.; Kim, S.; Hegde, V.I.; Snydacker, D.; Lu, Z.; Hao, S.; Kirklin, S.; Morgan, D.; Wolverton, C. High-throughput computational design of cathode coatings for Li-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Hector, L.G.; James, C.; Kim, K.J. Lithium Concentration Dependent Elastic Properties of Battery Electrode Materials from First Principles Calculations. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, F3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lau, K.C.; Meng, X. Precisely Engineering Interfaces for High-Energy Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Batteries 2025, 11, 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120441

Lau KC, Meng X. Precisely Engineering Interfaces for High-Energy Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Batteries. 2025; 11(12):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120441

Chicago/Turabian StyleLau, Kah Chun, and Xiangbo Meng. 2025. "Precisely Engineering Interfaces for High-Energy Rechargeable Lithium Batteries" Batteries 11, no. 12: 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120441

APA StyleLau, K. C., & Meng, X. (2025). Precisely Engineering Interfaces for High-Energy Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Batteries, 11(12), 441. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120441