Abstract

A successful expansion and intensification of the links between tourism and horticulture is needed for tourism to contribute to economic diversification. Without inter-sectoral coordination and the cultivation of sustainable links between tourism demand and other sectors in the destination’s economy, tourism will be unable to function as a driver of tourist attraction. Therefore, tourism needs to establish ties with other industries, such as agriculture, to positively contribute to the surrounding area’s economy and improve the quality of life in rural and urban areas. The current study explores the sustainable gardening practices (SGP) in hotels and their impact on predicting tourist revisit intention with the mediating role of tourist attitudes (ATT) toward green hotels and assessing the environmental gardening identity (EGID) as a moderator. Dyadic data were collected from 286 guests and hotel gardeners and was analyzed by PLS-SEM. The results revealed that sustainable gardening practices positively (R2 = 0.581) and significantly (p > 0.05) improve tourist revisit intention through the mediating role of tourist attitudes toward green hotels. At the same time, the empirical results supported the moderation effects of the EGID on the links between SGP and ATT. Several practical and theoretical implications were discussed and elaborated upon.

1. Introduction

The climate change problem requires careful consideration regarding the world’s soil as one of the crucial solutions. Agriculture and forestry, which dictate the managed soils worldwide, have the most significant roles to play [1]. Previous research proposes that green spaces such as gardens and golf courses have the potential to capture and store CO2 [2,3]. Therefore, sustainable gardening practices can help restrict the impacts of climate change. Sustainable gardening practices strive to preserve both resources and the environment by capturing stormwater and reducing the reliance on potable water, improving water quality, forgoing toxic pesticides, using few or no amendments, utilizing native plants, increasing biodiversity and bio-complexity, minimizing the employment of non-renewable resources such as peat moss and fossil fuels and stopping soil erosion [4,5].

Landscaping in hotel and resort gardens has a key role in attracting hotel visitors [6]. At the same time, hotel gardens are regarded as a significant contributor to generating a massive quantity of wet waste, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions and a heavy consumption of water [7]. Regarding water consumption, a study conducted in Zanzibar displayed that hotels with extensive gardens, especially coastal resorts, use an average of 50% of their total freshwater consumption [8]. Therefore, the different green hotel certification programs (i.e., the Green Star Hotel Programme (GSH) in Egypt) integrated sustainable gardening practices into their evaluation process [9]. On the other hand, by adopting sustainable gardening practices, green hotels can succeed in achieving more than one target at once. They can contribute to mitigating climate change, complying with the criteria of the green rating programs and targeting the growing customer segment with a solid environmental gardening identity by forming positive attitudes toward these practices [10]. Therefore, when green hotels adopt sustainable gardening practices to benefit society and the environment, guests are more willing to visit these hotels [11].

Green hotel practices and their relationship to different variables (e.g., cost, loyalty, visit intention, etc.) have been the subjects of a large body of literature [7,12,13]. This literature need to be more comprehensive and extensive, regarding the evaluation of open spaces in hotels, including gardens, their components and their influence on the environment and green guests’ attitudes and behaviors, [8,14]. Our study tries to bridge this gap by building on the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the identity theory and the theory of reasoned action to test the relationship between sustainable gardening practices (SGP) and green hotel visitor intentions, with the mediating effects of consumer attitudes toward the green hotel (ATT) and the moderating effect of the environmental gardening identity between sustainable gardening practices (SGP) and consumer attitudes toward the green hotel (ATT). The collected data were analyzed employing a structural equation-based model with the Smart-PLS data analysis method.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Sustainable Gardening Practices

Conventional gardening methods are based on herbicides and pesticides that cause water pollution from the chemical runoffs used by green space maintenance [15]. Therefore, traditional gardening practices may increase the emissions of volatile chemicals and carbon dioxide on a more global scale and may have a long-term impact on the balance of ecosystems [16]. Since the methods used in gardening directly impact the amount of carbon dioxide captured in the soil [17], several research attempts have been conducted to boost sustainable gardening practices to increase biodiversity and limit the effects of climate change [18]. Sustainable gardening practices, also called ecological or naturalistic, are distinguished by the growing of plants within local resource limitations, using the right physical site features with specific plant species that flourish under those conditions, preserving resources, using organic compost, using no or very few pesticides and artificial fertilizers, weeding and grass mowing on a relatively rare basis [10]. Sustainable gardening also provides various supplies and habitats for wildlife species [19]. This may involve providing nesting sites for wild bees or birds, constructing ponds to attract amphibians and choosing plants that deliver food for birds and pollinating insects [19,20,21].

According to [3], agriculture, climate, soil and forestry researchers have identified five steps that underpin sustainable gardening practices. (1) ”Minimizing carbon-emitting inputs”. This depends on the choice of tools, equipment and chemicals used in the garden. (2) “Don’t leave garden soil naked”. Bare soil is vulnerable to deterioration, weeds and carbon loss. (3) “Plant trees and shrubs”. They are big, woody and long-lived and can absorb more significant quantities of carbon than other plants for more extended periods. (4) “Expand recycling to the garden”. Discarding waste by recycling leaves, woody garden clippings, grass, kitchen waste and dead garden plants into compost and employing it in the garden will not only lessen the methane released from landfills but will enhance the garden’s soil and aid in storing carbon. (5) “Think long and hard about your lawn”. Soils contained in turf grasses could catch and keep considerable quantities of carbon.

2.2. Consumers’ Attitude towards Green Hotels as a Mediator in the Relationship between Sustainable Gardening Practices and Customers’ Green Hotel Visit Intention

In 2005, tourism contributed to climate change by producing roughly 5% of all human-made CO2 emissions, with the hotel industry accounting for 21% of total tourism CO2 emissions [22]. Global tourism’s carbon impact rose by 3.3% annually between 2009 and 2013, accounting for approximately 8% of global greenhouse emissions [23]. Green hotels strive to operate green carbon management initiatives to control air pollution, energy efficiency, water conservation, noise pollution and waste management, aiming to mitigate climate change [24]. Therefore, hotels that cannot implement green practices or promote such adoption effectively may be unable to retain their guests, especially green guests [25]. Many consumers nowadays search for hotels practicing these policies and are willing to pay more money for these green products and services [26,27]. A meta-analysis indicates that visitors anticipate paying a $9–$26 premium for a standard room in green hotels [28]. Therefore, examining guests’ “attitudes” to identify the extent of their “intention” to stay or visit green hotels while travelling is crucial [29,30]. Customer attitude can explain one-third of their behavior intention toward green hotel and restaurants visits [31]. Attitude is a positive or negative evaluation of an issue [32]. Accordingly, customer attitudes toward green hotels can be described as the tendency to evaluate favorably or unfavorably toward green hotels’ endeavors [33,34]. Here, [26] indicates that guest’ attitudes toward environmental issues is impacted by the green practices adopted by hotels. Many guests now look for green hotels mainly because they are aware of the environmental damages (i.e., the emissions emitted into the air, water and soil) and the wasting/harming of the environmental resources caused by the accommodations sector (i.e., the extreme consumption of non-durable goods, energy and water) [35]. In the same vein, [36] found that the more gardens were sustainability-managed, the more species they possessed and the more attractive they were in view of individuals. That is, a positive relationship exists between sustainable gardening practices and the aesthetical perception of a garden [37]. This positive evaluation of sustainable gardening practices is our argument to propose the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Sustainable gardening practices positively and significantly influence consume’ attitudes toward green hotels.

Building guests’ positive intentions is a fundamental target of every hotel due to its contribution to boosting guest retention rates and revenue [38]. Behavioral intentions are surrogate behavior indicators, as one’s confirmed probability to perform a specific action [32]. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the individual performance of a specific behavior is predicted by an individual’s attitude toward the behavior [39]. According to the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), most human behaviors are predictable based on their intention since such behaviors are voluntary and under the direction of the intention [40]. The TPB, on the other hand, is an extension of the TRA. The main distinction between these two models is that the TPB includes an extra dimension of perceived behavioral control as a factor of behavioral intention. This dimension is connected to control beliefs [41]. When guests perceive staying at a green hotel as experiencing a healthy, eco-friendly guestroom, consuming fresh and healthy food, and being more socially responsible, etc., they are probable to have a favorable attitude. Therefore, they are predicted to engage in that behavior [42]. Precisely, previous studies asserted that consumer attitudes toward green hotels favorably affects their intention to visit, stay and their willingness to pay a premium for eco-friendly hotels that have adopted green principles, e.g., sustainable gardening practices [29,43,44,45]. The following two hypotheses were derived based on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB).

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Consumer attitudes toward green hotelspositively and significantly influences the consumers’ green hotel visit intention.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Consumer attitudes toward green hotels mediates the relationship between sustainable gardening practices and customer green hotel visit intention.

2.3. Environmental Gardening Identity as a Moderator in the Relationship between Sustainable Gardening Practices’ Influence on the Consumer’s Attitude towards Green Hotels

Recently, identity has emerged as a significant influence on environmental attitudes and behavior [10]. According to the identity theory, identity, or “self-understanding,” refers to the methods of defining oneself in a community by encouraging cognition, emotion and behaviors in different domains [46,47]. In gardening, [48] argued that basic gardening behaviors (e.g., cultivating plants, following their growth, accumulating knowledge and experiencing sensory enjoyment) effectively facilitate a view of oneself as being near the earth. Recently, gardening has become a distinctive identity for individuals. According to [49], gardening has surpassed handiwork and cooking as the most preferred domestic duty among French households, and the satisfaction delivered by it is parallel to that offered by leisure activities. Similarly, a garden can be a fertile area for fostering a personal identity as an eco-friendly gardener. Therefore, a garden can work as a significant force in shaping an environmental identity [10]. Environmental identity is defined as an “experienced social standing of who we are in relation to and how we interact with the natural environment.” [50]. Having an environmental identity requires the individual to believe that the environment is essential in and of itself and is a crucial aspect of that person’s basic sense of self [51]. In light of this, [10] asserted the significance of an individuals’ environmental gardening identity in understanding the adoption of sustainable gardening behaviors.

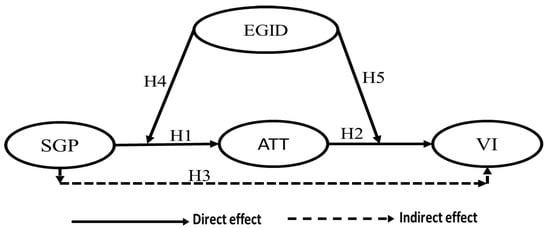

Regarding the effect of environmental identity on customer attitudes and behavior, based on the identity theory, “one’s behavior is dictated by self-identity” [52]. Additionally, the study of [53] found that, by grounding on the identity theory, environmental identity positively influences ecotourism attitudes and behaviors. As seen in Figure 1, and based on the identity theory, we developed the following hypotheses:

Figure 1.

The suggested theoretical framework with hypotheses. SGP → Sustainable Gardening Practices; ATT → Consumer Attitudes Towards Green Hotel; VI → Green Hotel Visit Intention; EGID→Environmental Gardening Identity.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

An environmental gardening identity moderates the sustainable gardening practices’ influence on consumer attitudes toward green hotels (the association will be more robust when the environmental gardening identity is high).

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

An environmental gardening identity moderates how consumer attitudes toward green hotels’ influence customer green hotel visit intention (the association will be more robust when the environmental gardening identity is high).

3. Methods

A quantitative-based research approach was adopted by designing a self-structured questionnaire to collect the study data. Partial least squares-based structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed. PLS-SEM is an appropriate method for exploring and testing the early phases of our theory. PLS-SEM was utilized to assess the measurement and validity of the structural model for its multivariate nature capabilities and good predictive power. Furthermore, a 5000 bootstraps approach was conducted to repeat the 286 dyadic date (total of 572) to assess the research hypotheses.

3.1. Participants and Collection of the Study Data

The research team benefited from postgraduate students working in hotels and resorts to collect the data through their excellent personal association with hotel and resort human resources managers (HRMs). The HRMs helped collect the required data from guests who had at least a balcony garden and hotel gardeners at the Sharm El-Sheikh five and four-star hotels and resorts (located in Egypt) using convenient sample and drop-and-collect techniques. We targeted hotels that have national, regional, or international environmental certificates approved by the global sustainable tourism council (GSTC). As a result, 50 five and four-star hotels were targeted in Sharm El-Sheikh (Egypt).

Sharm El-Sheikh was chosen as it owns numerous high-ranked five-and four-star hotels and resorts with vast green areas and gardens. The survey was split into two sequential phases. In the first phase, hotel guests were asked to answer and provide the information necessary for the ATT, IV and EGID variables. One month after, hotel gardeners within the same hotels and resorts were asked to complete the SGP questionnaire items. In the two phases, 400 questionnaires were disseminated to each sample (a total of 800 surveys). After removing all the unqualified and irrelevant questionnaires, we were left with 286 guests and 286 hotel gardeners. The Dyadic data were tested with an effective recovery rate of 71. 5%. The data were collected in August and September 2022. The respondents were required to sign a consent form and were given a choice between participating in the survey or skipping it. All the participants confirmed that their answers would be kept confidential. The final guest sample included 197 males (98.9%) and 89 females (31.1%). Most of them were between the ages of 19 and 52. For the hotel and resort gardeners, the final gardener’s sample comprised 253 males, accounting for 88.5% of the total, and 33 women (11.5 %). Most of them were between the ages of 32 and 54. The majority of the guests were from Germany (51%), followed by the Netherlands (20%), France (19%) and Russia (10%). A non-response bias test was conducted using the independent t-test analysis method. Since the mean-variance among late and early replies did not show any significant statistical differences (p > 0.05), the bias from non-response is not an issue and did not cause an issue in this study [54].

3.2. Scale and Measure Development

An extensive review of the related previous studies was conducted to develop the study scale and create the questionnaire items. This process yielded four significant measures that were employed as the study scale. The SGP (sustainable gardening practices variable) was tested by 13 items derived from [10,55,56]. At the same time, consumer attitudes toward green hotels (ATT) was operationalized by the four-items scale suggested by [34]. Three items from [57] were employed to measure the green hotel visit intention (IV). Finally, the EGID (environmental gardening identity) was measured by sixteen items created by [10]. A Likert scale of one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree) was employed. Academics and specialists in the field tested the tool (8). Eight academics and eight professionals in the field area tested the instrument. The text was transcribed and clarified. The scale content was retained and employed with no changes.

4. Findings of Data Analysis

The SmartPLS-4.0 program was employed to assess the previously justified research hypotheses using SEM (structural equation modeling) via “Partial least squares PLS 4.” The proposed theoretical model was tested in two sequential stages [54].

4.1. Evaluation of Outer Model (Validity Assessment)

Following the suggestions of [54,58], the scale validity (discriminant and convergent) and reliability were assessed through several criteria. First, for reliability, Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (C_R) values, as shown in Table 1, exceeded the threshold of 0.7, which signaled of a proper level of reliability.

Table 1.

Assessment of outer model validity.

Second, the standardized factor loading for all the reflective items was higher than 0.7, further supporting the scale’s convergent validity. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.50, which approved the convergent validity [57]. Finally, three main indices were checked to test discriminant validity: (1) cross-loading, (2), the Fornell–Larcker index and (3) the heterotrait–monotrait value (HTMT) [57]. As revealed in Table 2, the outer loading for the latent variables (bolded) exceeded the cross-loading with other items.

Table 2.

Cross-loading output.

Table 3 shows the bolded diagonal AVEs which were higher than the correlation coefficient between the variables. As a rule, [59] suggested that the readings on the HTMT should be less than 0.90. In the study, the levels of HTMT were significantly lower. Based on the findings, it is clear that the model structure possesses the necessary discriminant validity. As a direct consequence, the outputs of the outer model (measurement model) were deemed proper to move forward with the assessment of inner model (the structural model).

Table 3.

AVEs values and HTMT results.

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation (Hypotheses Testing)

The model should possess an adequate predictive and explanatory power before testing the path coefficient [60]. Furthermore, the multicollinearity test should show adequate results based on the VIF values not exceeding 5. The VIF values in our model ranged between 1.679 and 4.826 (<0.5), which supported the nonexistence of multicollinearity in the model. Furthermore, the lower level of R2 values was 0.10 for a good model fit [61]. Consequently, the R2 values for the study variables: ATT (R2 = 0.497) and VI (R2 = 0.581) were appropriate (Table 4). Likewise, the Stone-Geisser (Q2) index revealed that the ATT and VI values were higher than zero (Table 4), suggesting a sufficient predictive validity for our model [58]. As a direct result, an adequate level of predictive validity was also demonstrated for the structural model.

Table 4.

Model goodness of fit R2 and Q2.

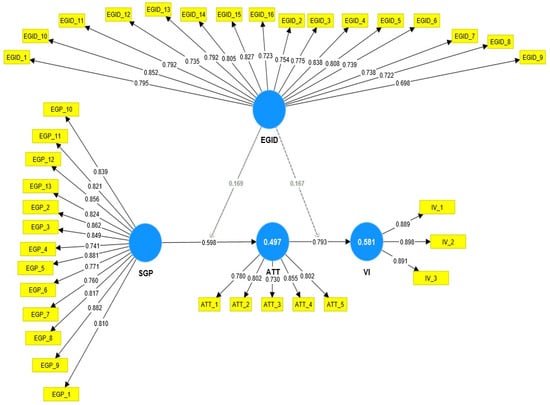

A bootstrapping method was used to conduct the final analysis, which consisted of a path coefficient and t-value analysis of the hypothesized paths. The hypothesis test results are displayed below in Table 5, and in Figure 2, which includes the path coefficient values and the relevant significance. SGP were found to have a positive and significant correlation with ATT (β = 0.598). Therefore, we can accept H1. The results also demonstrated that ATT had a significant (p < 0.000) and positive association with VI (β = 0.793), which led us to support H2. The mediation impact of ATT in the link between SGP-VI was supported with a significant effect size of β = 0.474. Therefore, H3 was accepted. Lastly, the findings supported the positive moderation impact of the EGID on the links between SGP toward ATT and ATT toward VI at significant path coefficient values of β = 0.169 and β = 0.167, respectively, which confirms H4 and H5.

Table 5.

The structural inner model’s findings.

Figure 2.

The tested inner and outer model. SGP → Sustainable Gardening Practices; ATT → Consumer Attitudes Towards Green Hotel; VI → Green Hotel Visit Intention; EGID → Environmental Gardening Identity.

5. Discussion and Implications

In line with the previous studies [26,36,37,62], our study demonstrated the significant positive impact of SGP and ATT (H1). As a result of the growing environmental awareness, customers perceive green practices based on their genuine altruism toward the environment, that is, doing something useful for the environment without desiring anything in return. Therefore, their perception of hotels adopting green practices and their belief that it is involved in eco-friendly practices, including sustainable gardening practices, would form a positive attitude toward the hotel in the guest’s minds [37,62]. These positive attitudes are shaped by the fact that green practices are defined in the hotel sector as a value-added business strategy that benefits stakeholders by engaging in environmental protection activities, such as waste reduction, energy and water usage and human health [63,64,65]. The hotel’s green practices and initiatives also include reducing energy and water use, recycling and reusing waste, improving building infrastructure, engaging in society, purchasing sustainable products, environmental education and awareness, lowering transportation carbon footprint and pursuing green building certification [66]. Within the theory of planned behavior (TPB) framework, this study confirms that green attitudes are an antecedent for the intentional behaviors of green hotel visits (H2). Overall, green attitudes are more likely to lead to eco-friendly activities [67,68]. This is because, based on the theory of reasoned action (TRA), guests are likely to behave in a way that strives to satisfy their beliefs. If customers are concerned regarding nature, they will probably want to be involved in favorably environmental practices (e.g., choice to visit or stay at green hotels) [69]. It has been proven that a green purchasing attitude may drive green purchasing intentions and behavior [70]. At the same time, a favorable attitude toward organic food may positively affect organic food purchasing intentions [71].

In agreement with the results of the direct relationships of our study and with the foundations of the theory of planned behavior (TPB), the empirical results prove that the impact of ATT as a mediating variable in the links between SGP and VI is significant and positive (H3). Guest perceptions of a hotel linked to green commitments and concerns, including sustainable gardening practices, can significantly affect their attitudes toward that hotel, which ultimately crystallize into behavioral intentions to visit it [62,72].

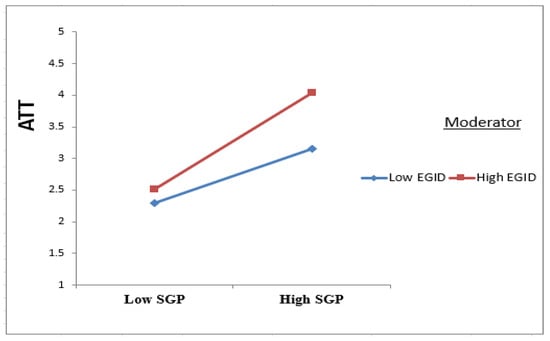

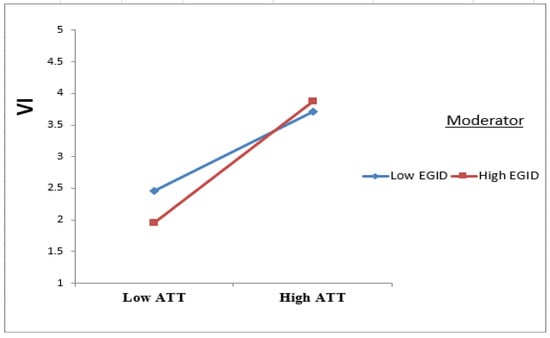

Finally, the empirical results supported the moderation effects of the EGID on the links between SGP and ATT (H4) and between ATT and VI (H5). In other words, according to the interaction plot in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the connections made by the EGID between SGP and ATT and between ATT and VI will strengthen. These results agreed with the studies in which environmental identity generally is among the most influential factors clarifying people’s attitudes and behavior toward environmental conservation [69,73]. According to Yazdanpanah and Forouzani [74], integrating personal norms and self-identity increased the proportion of the explained variation of the TPB model by 8 %. Similarly, a strong positive association was found between an environmental identity and engagement in sustainable gardening practices. Therefore, the environmental gardening identity differentiates between those who choose gardening practices as a way to connect to nature and those who choose them for other reasons, such as creativity, beauty, or growing food, with the former tending to be more environmentally friendly [10].

Figure 3.

EGID moderation effect on SGP toward ATT.

Figure 4.

EGID moderation effect on ATT toward VI.

In terms of the theoretical implications, the current study used the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action to prove that SGP predicts consumer attitudes toward green hotel visit intention. Additionally, according to the identity theory, our study used the EGID as a moderator to improve the effect of SGP on ATT and ATT on VI. Therefore, the study adds to the literature on horticulture, gardening and green behavior in hotels. Furthermore, the literature on SGP and the EGID needs to be expanded and is still in its infancy. Regarding the practical implications, this paper strives to exploit the vast gardens and green areas in most hotels and tourist resorts by adopting sustainable gardening practices to reduce the environmental effects of conventional gardening, comply with the requirements of green accreditation programs and influence the attitudes and behaviors of customers with an environmental gardening identity. Therefore, the authors examined the role of ATT in mediating the relationship between SGP and VI. At the same time, the EGID was tested as a moderator between SGP and ATT and between ATT and VI, respectively. Finally, based on a win-win principle, the study recommends that hotels can adopt and market sustainable gardening practices to attract the growing segment of customers with an environmental gardening identity. For example, about 49% of the adult population participates in gardening activities in the UK, which boasts around 24 million home gardens. Similarly, in the USA, it is estimated that 78% of homeowners engaged in gardening regularly [75], limiting climate change and supporting the local community by marketing its organic agricultural products by planting them in hotel gardens [76].

6. Conclusions and Future Research Opportunities

Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), the Theory of Reasoned Action and the identity theory, this study confirms that green attitudes are an antecedent for the intentional tourist behavior intention to stay in a green hotel. Overall, green attitudes are more likely to lead to eco-friendly activities. This is because tourists are likely to behave in a way that strives to satisfy their beliefs. If tourists are concerned regarding nature, they will probably want to be involved favorably in environmental practices (e.g., their choice to visit or stay at green hotels). It has been proven that a green purchasing attitude may drive green purchasing intentions and behavior. At the same time, a environmental gardening identity was found to be a strengthened moderator of the tested relationships.

Dyadic data were collected from hotel guests (286) and hotel gardeners(286) in Sharm El-Sheikh hotels and resorts (located in Egypt) using a convenient sample and drop-and-collect method. Sharm El-Sheikh was selected due to its abundance of five-star hotels and resorts with expansive green areas and gardens. The inner and outer model was evaluated using the PLS-SEM method. The outer measurement model showed a proper convergent and discriminant validity; consequently, the inner model was assessed to test the study hypotheses. The findings confirmed the significant positive impact of SGP on ATT; in return, ATT positively impacted VI. These findings suggest that, as a result of an increased awareness of the environment, customers evaluate green practices based on their genuine altruism toward the environment. This definition of altruism refers to doing something beneficial for the environment without expecting anything in return. Therefore, guest perception of the hotel adopting green practices and their belief that it is involved in eco-friendly practices, including sustainable gardening practices, would form a positive attitude toward the hotel in the minds of the guests, which might lead to a visit and revisit intention. The results also validated the positive moderation effects of the environmental gardening identity on the relationship between SGP and VI.

The current study, similar to the prior research that has been done on this subject, has several flaws, and it is proposed that further research routes can be investigated. First, the study investigated the impact of sustainable gardening practices (SGP) on tourist attitudes toward green hotels (ATT). The study further explored the direct impact of ATT on visit intention with moderating role of environmental gardening identity (EGID). However, several other factors can be employed and tested as mediating bodies, such as social influence and perceived behavioral control. Moreover, other variables can be employed and tested as moderators, such as tourist nationality, satisfaction and loyalty level, hotel price, tourist age, or a gardener’s years of experience. Additionally, the accurate causal effects between the latent variables are difficult to determine using cross-sectional data. Future researchers may use longitudinal or various data sources to confirm the study’s structure model. A reliable replication of the study’s results requires future researchers to implement the current model in other contexts or countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A.E. and S.F.; methodology, I.A.E., S.F. and A.M.S.A.; software, I.A.E. and S.F.; validation, I.A.E., A.M.S.A., F.A.A. and S.F.; formal analysis, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.; investigation, I.A.E., S.F. and A.M.S.A.; resources, I.A.E.; data curation, I.A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F., I.A.E. and A.M.S.A.; writing—review and editing, I.A.E., S.F. and A.M.S.A.; visualization, I.A.E.; supervision, I.A.E.; project administration, I.A.E., S.F., F.A.A. and A.M.S.A.; funding acquisition, I.A.E. and A.M.S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. 2365).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Deanship of Scientific Research ethical committee, King Faisal University (project number: GRANT2365, date of approval: 01/05/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from researchers who meet the eligibility criteria. Kindly contact the first author privately through e-mail.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pouyat, R.V.; Yesilonis, I.D.; Nowak, D.J. Carbon Storage by Urban Soils in the United States. J. Environ. Qual. 2006, 35, 1566–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pataki, D.E.; Alig, R.J.; Fung, A.S.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Kennedy, C.A.; Mcpherson, E.G.; Nowak, D.J.; Pouyat, R.V.; Romero Lankao, P. Urban ecosystems and the North American carbon cycle. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2006, 12, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union of Concerned Scientists. A Guide to Combating Global Warming from the Ground Up; Union of Concerned Scientists: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.B. Gardeners Perceptions of the Aesthetics, Manageability, and Sustainability of Residential Landscapes. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2002, 1, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.; Buttler, A.; Francez, A.-J.; Laggoun-Défarge, F.; Vasander, H.; Schloter, M.; Combe, J.; Grosvernier, P.; Harms, H.; Epron, D.; et al. Exploitation of Northern Peatlands and Biodiversity Maintenance: A Conflict between Economy and Ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2003, 1, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, A.; Cudney, E.; Paryani, K. Customer-driven Hotel Landscaping Design: A Case Study. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2013, 30, 832–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Trang, H.L.T.; Kim, W. Water Conservation and Waste Reduction Management for Increasing Guest Loyalty and Green Hotel Practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.S.; Sheta, W.A.; El Kordy, A.M. Environmental Assessment of Coastal Resorts: Recreational Spaces as a Case Study. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 974, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, C.; Dissanayake, D.M.P.P.; Karunasena, G.; Madhusanka, N. Mitigation of Challenges in Sustaining Green Certification in the Sri Lankan Hotel Sector. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018, 8, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesling, F.M.; Manning, C.M. How Green Is Your Thumb? Environmental Gardening Identity and Ecological Gardening Practices. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Predict Consumers’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aomar, R.; Hussain, M. An Assessment of Green Practices in a Hotel Supply Chain: A Study of UAE Hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 32, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perramon, J.; Oliveras-Villanueva, M.; Llach, J. Impact of Service Quality and Environmental Practices on Hotel Companies: An Empirical Approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 107, 103307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Sobaih, A.E.E.; Aliedan, M.; Azazz, A.M.S. The Effect of Green Human Resource Management on Environmental Performance in Small Tourism Enterprises: Mediating Role of Pro-Environmental Behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchoud, H.; Moreau-Guigon, E.; Farrugia, F.; Chevreuil, M.; Mouchel, J.M. Contribution by Urban and Agricultural Pesticide Uses to Water Contamination at the Scale of the Marne Watershed. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 375, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niinemets, Ü.; Peñuelas, J. Gardening and Urban Landscaping: Significant Players in Global Change. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.A.; Phares, N.; Nightingale, K.D.; Weatherby, R.L.; Radis, W.; Ballard, J.; Campagna, M.; Kurtz, D.; Livingston, K.; Riechers, G.; et al. The Potential for Urban Household Vegetable Gardens to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 157, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, C.D.; Lortie, C.J. The Importance of Urban Backgardens on Plant and Invertebrate Recruitment: A Field Microcosm Experiment. Urban Ecosyst. 2010, 13, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Z.G.; Fuller, R.A.; Loram, A.; Irvine, K.N.; Sims, V.; Gaston, K.J. A National Scale Inventory of Resource Provision for Biodiversity within Domestic Gardens. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J.L.; Martin, A.P.; Shortall, C.R.; Todd, A.D.; Goulson, D.; Knight, M.E.; Hale, R.J.; Sanderson, R.A. Quantifying and Comparing Bumblebee Nest Densities in Gardens and Countryside Habitats. J. Appl. Ecol. 2007, 45, 784–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Hermans, Z.; de Koster, J.; Smismans, R. Promoting Pro-Environmental Gardening Practices: Field Experimental Evidence for the Effectiveness of Biospheric Appeals. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grosbois, D.; Fennell, D.A. Determinants of Climate Change Disclosure Practices of Global Hotel Companies: Application of Institutional and Stakeholder Theories. Tour. Manag. 2022, 88, 104404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The Carbon Footprint of Global Tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Sharma, V.P.; Singh, R.; Vijayvargy, L.; Nilaish. Adopting Green and Sustainable Practices in the Hotel Industry Operations—An Analysis of Critical Performance Indicators for Improved Environmental Quality. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. The Compelling “Hard Case” for “Green” Hotel Development. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2008, 49, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaktola, K.; Jauhari, V. Exploring Consumer Attitude and Behaviour towards Green Practices in the Lodging Industry in India. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 19, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Matute, J.; Mika, M.; Kubal-Czerwińska, M.; Krzesiwo, K.; Pawłowska-Legwand, A. Predictors of Patronage Intentions towards ‘Green’ Hotels in an Emerging Tourism Market. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 103, 103221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuminoff, N.V.; Zhang, C.; Rudi, J. Are Travelers Willing to Pay a Premium to Stay at a “Green” Hotel? Evidence from an Internal Meta-Analysis of Hedonic Price Premia. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2010, 39, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An Application of Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Young Indian Consumers’ Green Hotel Visit Intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lita, R.P.; Surya, S.; Ma’ruf, M.; Syahrul, L. Green Attitude and Behavior of Local Tourists towards Hotels and Restaurants in West Sumatra, Indonesia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 20, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, A. A Structural Model of Environmental Attitudes and Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Lee, J.-S. Empirical Investigation of the Roles of Attitudes toward Green Behaviors, Overall Image, Gender, and Age in Hotel Customers’ Eco-Friendly Decision-Making Process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, H.; Rundmo, T. Personality, Risky Driving and Accident Involvement among Norwegian Drivers. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2002, 33, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B.; Kumar, S. Values and Ascribed Responsibility to Predict Consumers’ Attitude and Concern towards Green Hotel Visit Intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Green Hotel Choice: Testing the Effect of Environmental Friendly Activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Junge, X.; Matthies, D. The Influence of Plant Diversity on People’s Perception and Aesthetic Appreciation of Grassland Vegetation. Biol. Conserv. 2010, 143, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann-Matthies, P.; Marty, T. Does Ecological Gardening Increase Species Richness and Aesthetic Quality of a Garden? Biol. Conserv. 2013, 159, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Back, K.-J. Relationships Among Image Congruence, Consumption Emotions, and Customer Loyalty in the Lodging Industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2008, 32, 467–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentiss-Hall. Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Negative Word-of-Mouth Communication Intention: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An Investigation of Green Hotel Customers’ Decision Formation: Developing an Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Green Hotel Knowledge and Tourists’ Staying Behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2211–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.G.T.; Bagheri, P.; Tümer, M. Decoding Behavioural Responses of Green Hotel Guests. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2509–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.D.; Saunders, C.D. Introduction: Environmental and Conservation Psychology. In The Oxford Handbook of Environmental and Conservation Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Li, L.M.W. The Relationship between Identity and Environmental Concern: A Meta-Analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The Role of Nature in the Urban Context. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 127–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousse, C. Travail Professionnel, Tâches Domestiques, Temps « libre »: Quelques Déterminants Sociaux de La Vie Quotidienne. Econ. Stat. 2015, 478, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, A.J. Self, Interaction, and Natural Environment: Refocusing Our Eyesight; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Fayyad, S. Underdog Environmental Expectations and Environmental Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Hotel Industry: Mediation of Desire to Prove Others Wrong and Individual Green Values as a Moderator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ Support for Tourism: An identity perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeroovengadum, V. Environmental Identity and Ecotourism Behaviours: Examination of the Direct and Indirect Effects. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguina, A. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 2015, 38, 220–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coisnon, T.; Rousselière, D.; Rousselière, S. Information on Biodiversity and Environmental Behaviors: A European Study of Individual and Institutional Drivers to Adopt Sustainable Gardening Practices. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 84, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. The Investigation of Green Best Practices for Hotels in Taiwan. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 57, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, Y.H.; Kim, D.J.; Wachter, K. A Study of Mobile User Engagement (MoEN): Engagement Motivations, Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Continued Engagement Intention. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Sinkovics, R.R., Ghauri, P.N., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.; Day, J.; Ha, S. The Impact of Eco-Friendly Practices on Green Image and Customer Attitudes: An Investigation in a Café Setting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, K.; Fairhurst, A. The Review of “Green” Research in Hospitality, 2000-2014. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D.; Svaren, S. How “Green” Are North American Hotels? An Exploration of Low-Cost Adoption Practices. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Abdelrahman, M.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Alrawad, M.; Fayyad, S. Environmental Transformational Leadership and Green Innovation in the Hotel Industry: Two Moderated Mediation Analyses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.; Che Abdullah, S.N.; Haron, S.N.; Hamid, M.Y. A Review of Green Practices and Initiatives from Stakeholder’s Perspectives towards Sustainable Hotel Operations and Performance Impact. J. Facil. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. Pro-Environmental Purchase Behaviour: The Role of Consumers’ Biospheric Values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 33, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tonder, E.; Fullerton, S.; de Beer, L.T.; Saunders, S.G. Social and Personal Factors Influencing Green Customer Citizenship Behaviours: The Role of Subjective Norm, Internal Values and Attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccioli, M.; Czajkowski, M.; Glenk, K.; Martin-Ortega, J. Environmental Attitudes and Place Identity as Determinants of Preferences for Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 174, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Lin, C.-K.; Safdari, M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-H.; Hamilton, K. Using an Integrated Social Cognition Model to Explain Green Purchasing Behavior among Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling Ways to Reach Organic Purchase: Green Perceived Value, Perceived Knowledge, Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S. The Drivers of Green Brand Equity: Green Brand Image, Green Satisfaction, and Green Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatersleben, B.; Murtagh, N.; Abrahamse, W. Values, Identity and pro-Environmental Behaviour. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2014, 9, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Iranian Students’ Intention to Purchase Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmin-Pui, L.S.; Griffiths, A.; Roe, J.; Heaton, T.; Cameron, R. Why Garden?—Attitudes and the Perceived Health Benefits of Home Gardening. Cities 2021, 112, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Ameen, F.A.; Fayyad, S. Agritourism and Peer-to-Peer Accommodation: A Moderated Mediation Model. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).