Abstract

Micropropagation is particularly relevant to A. xanthorrhiza because this crop is traditionally propagated by crown buds, with very low field multiplication rates and a high incidence of systemic pathogens, whereas in vitro culture enables rapid clonal multiplication, sanitation, and long-term conservation of elite and regional genotypes. Micropropagation of A. xanthorrhiza remains hindered by physiological disorders such as hyperhydricity and low shoot proliferation, often associated with limited gas exchange and inadequate culture systems. This study evaluated the effects of different gas exchange regimes and liquid culture methods on in vitro morphogenetic and structural responses. Forced ventilation at 81.3 gas exchanges per day reduced hyperhydricity to 8.3%, while sealed vessels exhibited a hyperhydricity rate of 65.8%. RITA® bioreactors resulted in the highest shoot multiplication rate (6.5/explant), which is a 48.2% increase over semi-solid medium (4.4 shoots/explant). Additionally, RITA® systems enhanced leaf expansion, reduced oxidative symptoms, and improved shoot morphology. These findings demonstrate that combining ventilation and immersion control is a promising strategy to improve micropropagation efficiency in A. xanthorrhiza, providing quantitative evidence that complements and extends prior qualitative studies on in vitro ventilation and liquid culture systems.

1. Introduction

Arracacha (Arracacia xanthorrhiza Bancroft) is a vegetatively propagated root crop native to the Andes, where it has been cultivated since pre-Columbian times. It is primarily used as a food source and holds significant regional and economic value in South America, especially in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru [1,2]. In its native regions, it is commercialized fresh and eaten boiled, fried, or in soups, purées, salads, and baked goods. Its tuberous roots contain high starch levels (>70%), dietary fiber (4.07%), protein (9.64%), potassium (3.32%), magnesium (1.12%), calcium, and vitamin A [3]. Their swelling capacity (3.86 g g−1 dry weight base) makes them useful in pasta and bakery products, while phenolics such as 1-caffeoylquinic acid, quercetin derivatives, and d-viniferin offer antioxidant and gut health benefits [3]. Notably, A. xanthorrhiza is the only Apiaceae species domesticated in the Americas through asexual propagation [4], which consists of isolating and rooting cormels. This technique is still used today and contributes to the dissemination of crop and soil diseases, leading to economic losses and the genetic erosion of cultivated forms [5,6].

Micropropagation techniques have emerged as an essential tool to support mass clonal propagation and conservation in this as well as other Andean vegetatively propagated crops [7,8,9,10]. Since the 1980s, various studies have developed protocols for direct and indirect shoot regeneration, organogenesis, and somatic embryogenesis in arracacha [11,12,13,14]. Although micropropagation has enabled large-scale propagation and the preservation of landraces and wild relatives [15], conventional systems using semi-solid media and sealed vessels still suffer from several limitations, including low multiplication rates, high costs, physiological disorders such as hyperhydricity, and poor acclimatization success [11]. Reduced efficiency of conventional micropropagation systems is partly due to the accumulation of unfavorable gases within sealed culture vessels, resulting from limited gas exchange. Among these, ethylene [16,17,18] stands out as a key growth regulator that negatively affects in vitro cultures by inhibiting shoot proliferation, altering morphogenesis, and promoting physiological disorders such as hyperhydricity and premature senescence [19]. Elevated ethylene levels ultimately compromise plant vigor and acclimatization success. In contrast, culture systems that enhance gas exchange favor the removal of ethylene from the in vitro environment, mitigating its inhibitory effects and improving overall micropropagation performance.

Improving the efficiency and physiological quality of in vitro-propagated plants requires innovative systems that enhance gas exchange and nutrient availability. Temporary immersion systems (TIS) and ventilated culture vessels offer promising alternatives, and their effects on arracacha development have not been thoroughly explored. In this species, different gas exchange intensities and TIS affect micropropagation performance and morphophysiological traits [12,13].

The collective body of research demonstrates that TIS represent a strategic advancement for the micropropagation of wood, fruit, and agroforestry species, although their application remains uneven across taxa. The literature describes that only a small fraction of TIS studies focus on tree species, despite clear advantages such as increased shoot proliferation, improved physiological quality, and superior acclimatization performance compared with semi-solid or continuous immersion systems [20,21]. Species such as Eucalyptus grandis × Eucalyptus urophylla, Eucalyptus globulus, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Pistacia spp., Malus domestica, Castanea sativa, Salix viminalis, Artocarpus altilis, Tectona grandis, Psidium guajava, Kalopanax septembolus, Cedrela odorata, Phoenix dactylifera (‘Mejhool’ and ‘Boufeggous’), Musa spp., Saccharum spp., Vanilla planifolia, Agave potatorum, Hylocereus undatus, Coffea arabica, Colocasia esculenta, Ananas comosus and Centella asiatica highlight the versatility of TIS across biological and commercial contexts. Comparative analyses of TIS, such as RITA®, PlantForm™, SETIS™, TIB, and Ebb-and-Flow, reinforce that immersion frequency and duration, explant density, and gas exchange are decisive parameters controlling hyperhydricity and biomass accumulation, requiring species-specific optimization rather than generalized protocols [20,21,22].

At the species and protocol levels, experimental studies reinforce and contextualize these broader trends by demonstrating that successful micropropagation depends equally on early-stage establishment, hormonal balance, and rooting strategies. In some species, efficient surface sterilization combined with MS or WPM media resulted in high explant survival and shoot development, supporting the relevance of nutrient-rich basal media for native woody species [23]. Similarly, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis showed strong responsiveness to cytokinin-mediated shoot induction while achieving optimal rooting without auxin supplementation, reducing costs and protocol complexity [24]. These findings align with TIS-based studies in Phoenix dactylifera, where PlantForm™ systems enhanced shoot number, root quality, chlorophyll content, and acclimatization success relative to gelled media, underscoring the physiological benefits of liquid-based, aerated environments [22]. When integrated with scaling-up analyses, these studies also highlight emerging challenges, such as somaclonal variation associated with excessive subculturing and the careful use of hormetic agents, such as silver nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes, in Saccharum spp., Stevia rebaudiana, and Vanilla planifolia [21]. Collectively, the evidence supports TIS as robust knowledge-intensive platforms, whose successful commercial application depends on rigorous experimental calibration, biological understanding, and standardization across diverse plant species [20,21,22,24].

In that context, the in vitro pattern of A. xanthorrhiza morphogenesis in TIS as well as the role of the atmosphere composition in the culture flasks remain unknown. Thus, the present investigations aimed to understand the effects of gas exchange on A. xanthorrhiza in vitro morphogenesis and to compare micropropagation performance and morphophysiological traits across classic gelled culture, culture media environments, gas exchange intensities, and TIS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

The cv. Amarela de Senador Amaral (ASA) was used due to its representativeness in Brazilian crop fields, which occupy 95% of the country’s cultivated areas [7]. All tests were performed with in vitro plants previously established following the procedures described by Marques et al. [11]. The mother plants originated from cormels of healthy, vigorous plants selected from the production fields of family farmers in Angelina County (27°27′22.5′′ S; 49°3′47.0′′ E), Santa Catarina State, South Brazil.

2.2. Culture Medium and Conditions

The cultures were cultivated in medium based on B5 saline formulation [14], supplemented with modified STABA vitamins [25,26], 3% sucrose (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, part number S0389) (w/v), 0.5 µM of α-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA, Sigma Aldrich, part number N0640), 1 µM of meta-topolin (mT, Duchefa Biochemie B.V., Haarlem, The Netherlands, CAS number 75737-38-1), and 26 µM of AgNO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, part number S8157), with pH adjusted to 5.8 with 1M KOH, before sterilization at 121 °C for 15 min.

The vessels and bioreactors were incubated in a growth room at 25 ± 2 °C, 60% ± 10% relative humidity, and a 16 h photoperiod under 50 µM photons m−2 s−1 provided by white-spectrum LED lamps (GreenPower TLED W, Signify N.V., Eindhoven, The Netherlands); each experimental unit consisted of one vessel or bioreactor containing 15 in vitro plantlets. In microplates, the air was renewed, depending on the filter type (based on the vessel model; Supplementary Figure S1). In the RITA® temporary immersion system, the culture medium was driven by compressed air (1 bar) for 3 min at 3 h intervals, resulting in 8 immersion cycles per day.

2.3. Evaluation of Gas Exchange, Liquid, and Semi-Solid Medium During In Vitro Morphogenesis

To evaluate the effects and optimal gas exchange (GE) in static medium conditions, a pilot test was performed, comparing five different situations: 0, 9.87, 13.09, 15.58 and 81.35 GE/day, using 80 mm diameter and 40 mm height O95/40 + OD95 Microbox® Micropropagation containers and hermetic covers or with different mesh GE filters from SACO2™ (Sac 02 Belgium NV, Deinze, Belgium) [27] whose lids were equipped with three different types of HEPA filters. The total gas volume contained in the vessel was exchanged 0, 10, 13.1, 15.6, or 81.4 times per day, depending on the filter type (based on the vessel model; Supplementary Figure S1). The five treatments (GE/day) were repeated five times, composing 25 sample units, arranged in a randomized complete block design. Each sample unit consisted of one Microbox containing five in vitro plantlets with 1 cm height and one leaf and was filled with 30 mL of culture medium.

According to the literature [28,29,30], Pn per vessel can be estimated by the following formula: , where k is a conversion coefficient, N is the number of air exchanges of the vessel, Co is the CO2 concentration outside the vessel, Ci is the CO2 concentration inside the vessel, and LA is the leaf area of plantlets per vessel (m2).

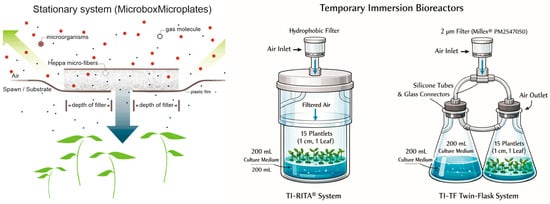

In a further experiment, we compared the morphogenetic characters of cultures grown in static liquid and semi-solid media (with and without GE) with those of plants in different TIS. The cultures maintained in static medium were cultivated in 90 mm diameter and 140 mm height O119/140 + OD119/140 Microbox® micropropagation containers with a hermetic cover or a HEPA-filtered cover at 15.58 GE/day. The semi-solid medium was jellified with 0.2% (w/v) Phytagel™ (Sigma-Aldrich; part number P8169), and the liquid medium was embedded in 100 mL of vermiculite substrate in order to sustain the plant position and aeration. The cultures in bioreactors were managed in TIS RITA® (VITROPIC™, Saint-Mathieu-de-Tréviers, France) (henceforth, TI-RITA®) or in TIS twin-flasks (TI-TF) assembled with two 500 mL glass Erlenmeyer flasks, closed with silicone stoppers, and drilled with glass ferrules along with silicone hoses for connection of plants and medium vessels, enabling air and medium flow in the system. In both bioreactors, air was sterilized at 1 bar using a polypropylene hydrophobic filter membrane with a 2 μm pore size (Merck Millipore Millex™, Burlington, VT, USA, part number PM2547050). All vessels and TIS received 15 sprouts, each approximately 1 cm in height and bearing a single leaf, and were filled with 200 mL of culture medium. The experiment consisted of six treatments, each replicated five times, totaling 30 experimental units. The trial was arranged in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A schematic figure to describe both stationary microplates and TIS bioreactors.

In both experiments, after 30 days in culture, the frequencies of survival, number of sprouts, and shoots and the levels of defoliation, fresh mass, dry mass, dry matter, and water content were quantified per treatment. The morphogenetic traits were observed using a stereomicroscope (SHZ10®, Olympus™, Tokyo, Japan). They registered through a DSLR digital camera (EOS Rebel T3i® with Lens EF-S 18–135 mm 1:3.5–5.6 F IS®, Canon™, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. Diaphanization and Scanning Electron Microscopy for Stomatal Counting and Morphology Evaluation

The leaves were fixed and stored as previously described by Melo de Pinna, Kraus and Menezes [15]. Five samples of each treatment at the mid-lamina region (areas in the vicinity of large veins were avoided) were treated with chloroform for 2 h by shaking and then rinsed in 70% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, part number 1.00983) and tap water. The fragments were treated in sequence, first with a 10% NaOH solution for 2 h with shaking and then with a 10% NaOCl solution until complete tissue clarification, as previously reported by Pompelli et al. [31].

To clarify the tissues, the leaves were immersed in an ethanol–xylene (Sigma-Aldrich, part number 534056) (1:1) solution for 30 s, followed by xylol for another 30 s, rinsed in deionized water, colorized by two series of 1% (w/v) toluidine blue (Sigma-Aldrich, part number 9640) and 1% (p./v.) sodium tetraborate (Sigma-Aldrich, part number 221732), and finally rinsed with deionized water for 3 min. The leaves were mounted on slides with cover glass and sealed with DPX Mountant for histology (Sigma-Aldrich, part number 06522).

The material was observed under an optical microscope (Olympus BX-40®, Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) and photographed (Olympus DP71®, Olympus Center Valley™, Tokyo, Japan). For each treatment in the evaluation, three random optical fields along the limb were photographed and analyzed using ImageJ® v. 1.53k) [32]. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), leaf fragments (~0.5 cm2) of a fully expanded leaf were sampled and immediately fixed in a Karnovsky solution [33], prepared in 0.1 M of cacodylate buffer (sodium cacodylate trihydrate, Sigma Aldrich, part number C4945) at pH 7.4 and 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Aldrich, part number G5882) for 60 h at 4 °C. All preparation steps were conducted as described in detail in Pompelli et al. [31] with modifications proposed by Cao et al. [34]. The images were captured in a JEOL XL30® scanning electron microscope (JEOL™, Tokyo, Japan) at 10 kV and amplification from 100 to 3000×. The full process was performed at Central Laboratory of Electron Microscopy (LCME) of the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) in Florianópolis, Brazil.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

In order to reduce the potentiality of multiplicative effects and/or scalar distortions that inflate the variance of the data under analysis, information measured as percentages (such as survival and density rates) were submitted to transformation through the . In the same approach, counting data (such as sprout, shoot and root frequencies) were transformed by the .

All the quantitative data collected in the experiments described above were subjected to normality and homoscedasticity tests and then analyzed using ANOVA, with Scott–Knott hierarchical clustering of the means at the 5% significance level. All the statistical analyses were performed through data processing in R software through GerminaR package v. 2.1.6 [35].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gas Exchange Intensities

The use of GE membranes did not affect plantlet survival, and across all treatments in the pilot experiment, the mean survival was 96.8%, and the defoliation was 1.3 leaves per plant (Table 1; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Means of survival (%), sprouts, shoots, dead leaves, roots (no. per sample unity), hyperhydricity (%), fresh mass, dry mass (mg/plant), dry matter and water content (%) of in vitro cultures of A. xanthorrhiza plantlets cultivated under different gas exchange (GE) intensities per day.

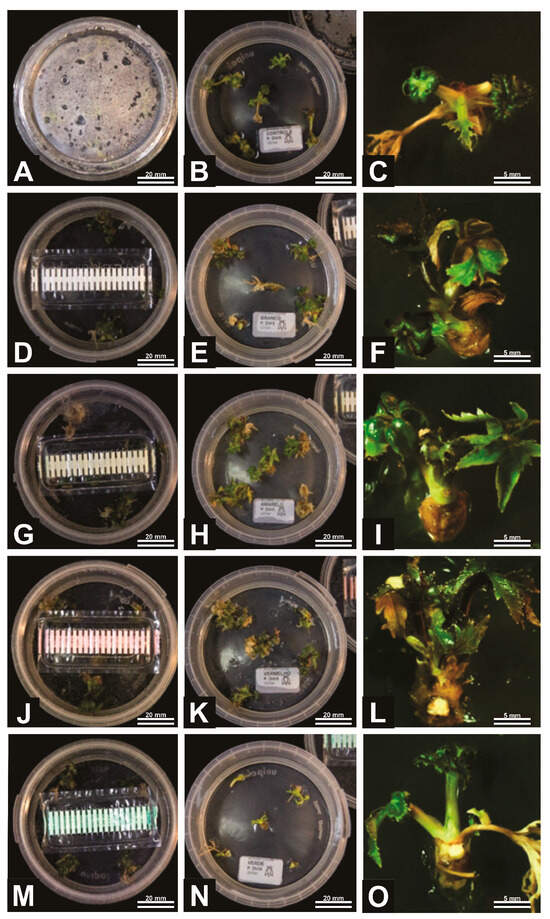

Figure 2.

General aspects of A. xanthorrhiza organogenesis under different gas exchange (GE) intensities: no GE possibility (A–C), 9.87 GE/day (D–F), 13.09 GE/day (G–I), 15.58 GE/day (J–L), and 81.35 GE/day (M–O). Figures (A,D,G,J,M) represent initiation of process, while Figures (B,E,H,K,N) are the intermediary phase and Figures (C,F,I,L,O) are the final elongation process.

Based on previous studies, it was expected that increasing gas exchange (GE) would promote more sprouts and newly formed leaves, as improved ventilation is known to reduce ethylene accumulation and enhance CO2 availability, thereby favoring morphogenetic responses in vitro [36,37,38,39,40]. However, in the present study, this expected trend was not progressively observed across all GE levels. A statistically significant response occurred only at the highest ventilation rate (81.3 GE per day), which unexpectedly resulted in a marked reduction in the number of sprouts (1.46 per plant). The number of shoots per plant reached its maximum at 15.6 GE per day (5.16) and its minimum at 81.3 GE per day (2.90), while the number of dead leaves was higher under low or absent gas exchange (0–13.1 GE per day).

Although membranes that allowed 15.6 GE/day resulted in enhanced sprout and shoot emissions (5.16 shoots/explant, an increase of 34%), this treatment showed a 51.2% increase in total dry matter and a 31.5% increase in fresh mass. However, 81.3 GE/day resulted in lower sprout/explant production (22.3%) and 24.9% fewer shoots, resulting in a 45.4% reduction in fresh mass. According to Kozai [40], net photosynthesis is about 6 times higher in ventilated vessels than in non-ventilated vessels. Also, this system increases gas permeability in in vitro culture vessels through passive or forced ventilation, thereby significantly enhancing net photosynthesis (Pn) by improving CO2 availability and reducing gaseous constraints typical of sealed systems [28,30,40]. Under these conditions, plantlets can attain photosynthetic rates comparable to those of greenhouse-grown plantlets and progressively reduce their dependence on exogenous sucrose. This shift toward photoautotrophic growth is associated with increased biomass accumulation, improved leaf physiological functionality, and enhanced stomatal performance, as a consequence of improved CO2 availability, reduced ethylene accumulation, and more effective gas exchange within ventilated culture vessels [40,41,42].

In agreement with Kubota and Kozai [28], increasing gas permeability of in vitro culture vessels through diffusive and forced ventilation enhanced net photosynthesis in potato plantlets, with forced ventilation producing the highest rates, whereas minimal ventilation resulted in near-zero net photosynthesis. These authors did not report increases in net photosynthetic rate; however, they showed that forced ventilation increased fresh weight by 2.4-fold and dry weight by up to 3.3-fold compared with minimal ventilation. These authors attribute such effects to increased CO2 availability within the vessels due to higher air exchange and that the dry weight per plantlet in the forced ventilation natural with air-diffusive filters treatments on day 30 was 3.3 and 2.1 times higher, respectively, as compared to that in the natural without air-diffusive filters. Consequently, plantlets cultivated in ventilated vessels exhibit greater physiological robustness and superior acclimatization performance after transfer to ex vitro conditions.

According to Niu et al. [30], culture vessels that allow gas exchange primarily provide the physical conditions required to quantify in situ CO2 exchange rather than directly determining the magnitude of net photosynthesis. They emphasized that net photosynthetic rates are strongly influenced by plant-related factors such as physiological status, photosynthetic capacity, and responsiveness to CO2 and light, which may differ among plantlets within the same system. Consequently, although ventilated culture systems permit gas exchange, increases in net photosynthesis are not necessarily uniform or consistently detectable at the population level. As discussed in a previous study by our research group [11], only plantlets physiologically well-adjusted to the culture environment effectively translate improved gas exchange into higher net photosynthetic rates. In contrast, others may not fully express their photosynthetic potential, rendering it visually or statistically indistinguishable from the others. Nonetheless, culture vessels and their closures regulate the internal gaseous microenvironment by controlling gas exchange between the vessel and the surrounding air. As discussed by Huang and Chen [43], this exchange primarily limits ethylene accumulation and excessive CO2 while allowing the renewal of atmospheric gases, thereby modifying the internal conditions experienced by in vitro plantlets. In this context, Zobayed et al. [44] emphasized that ventilation—particularly forced ventilation—is more effective than natural ventilation in correcting the in vitro gaseous environment, being a prerequisite for photoautotrophic micropropagation. Ventilated systems are consistently associated with higher net photosynthesis, reduced dark respiration, improved physiological performance, and enhanced ex vitro establishment. Taken together, these studies indicate that the effects of vessel permeability on net photosynthesis depend not only on the physical properties of the containers but also on how effectively gas exchange alleviates gaseous limitations to plant metabolism, providing a conceptual framework that complements the quantitative evidence reported in experimental studies such as Kubota and Kozai [28].

3.2. Morphogenesis Under Different Medium Availability and Gas Exchange Systems

To compare classic gelled culture medium with passive GE systems, liquid media environments, and TIS, preliminary tests were established to perform the fairest comparisons across such diverse conditions. The results of the experiment set the value of 15.6 GE/day in passive GE conditions (Figure 1).

To compare the static liquid medium with the other systems, a trial test was performed with 200 mL of medium, the minimum volume required to operate TI-RITA® and TI-TF. At such volume, the plants naturally became submersed in the medium, dying from anoxia and hyperhydricity within 10 days.

A circumvent for the problem was sought in inert substrates to embed in the medium; therefore, tests were performed with 100 mL of perlite (volcanic glass mineral) and vermiculite (phyllosilicate mineral) to sustain the plants and enable proper aeration. As the first one floated without aggregation, the choice of vermiculite substrate was made in the tests with liquid medium, which generated unexpected contrasts, as discussed forward.

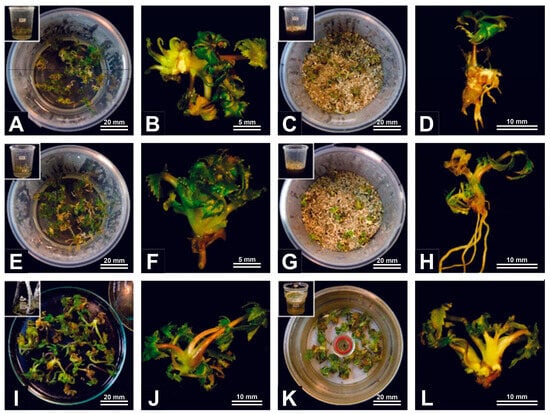

The overall survival rate in response to the treatments was 91.11%, with no statistical difference between them. Notwithstanding, the adaptation and development of the cultures to the different conditions showed some remarkable contrasts between the liquid medium with vermiculite and the semi-solid and TI conditions (Table 2, Figure 3).

Table 2.

Means of survival (%), sprouts, shoots, dead leaves, roots (n. per sample unity), hyperhydricity (%), fresh mass, dry mass (mg/plant), dry matter and water content (%) of in vitro cultures of A. xanthorrhiza plantlets cultivated in differential medium availability (semi-solid, Ss and liquid, Lq) and different gas exchange systems (hermetic, passive and active gas exchange).

Figure 3.

General aspects of A. xanthorrhiza semi-solid and liquid cultures under hermetic, passive and active gas exchange regimes: semi-solid medium with no gas exchange (A,B), liquid medium and vermiculite with no gas exchange (C,D), semi-solid medium with passive exchange (E,F), liquid medium and vermiculite with passive exchange (G,H), temporary immersion bioreactor with twin flasks (I,J), and RITA® temporary immersion bioreactor (K,L).

The sprouting showed cultures maintained in TI-RITA® (3.3 sprouts per plant), semi-solid medium with gas exchange (SS-GE) (3.3 sprouts/plant), IT-TF (2.78 sprouts per plant), and gelled medium hermetic (2.7 sprouts/plant), with no differences among them. The treatments with liquid medium over vermiculite with gas exchange (LQ-GE) and hermetic (LQ-H) presented the lower values, with no significant variations between them (1.70 and 1.78 sprouts per plant, respectively). The same tendency was observed in the number of shoots, with statistically superior values in TI-RITA® (9.33), SS-GE (7.77), TI-TF (6.83), and SS-H (6.28), with no differences between treatments, and lower emission in LQ-H (3.68) and LQ-GE (4.05). The defoliation measured by the number of dead leaves followed an inverse pattern, presenting higher statistical values in both treatments with liquid medium and vermiculite.

Temporary immersion systems (TIS) and intermittent immersion systems (IIS) have consistently been reported as more efficient alternatives to permanent immersion and semi-solid culture systems, mainly because they balance nutrient availability with adequate aeration. Studies on banana micropropagation demonstrate that IIS can significantly enhance regenerative rates compared with permanent immersion systems, particularly in responsive genotypes, by promoting periodic renewal of the in vitro atmosphere and preventing gas accumulation that limits cellular respiration [45,46]. These findings are reinforced by broader analyses showing that TIS, including RITA®, outperform semi-solid media by increasing shoot multiplication and uniformity while reducing the variability associated with continuous liquid exposure [20,47]. Comparative evaluations between liquid and semi-solid media further highlight that liquid environments can enhance shoot proliferation and growth but only when continuous submersion is avoided. It has been demonstrated that permanent liquid cultures often induce hyperhydricity, oxidative stress, and reduced shoot quality, whereas TIS mitigate these disorders by alternating immersion and aeration phases [48,49]. In this context, the use of TIS allows plants to benefit from improved nutrient uptake typical of liquid media while preventing excessive hydration and hypoxic stress commonly observed under static liquid conditions [50].

The importance of gas exchange emerges as a central factor underlying TIS’ superior performance. Classical studies on in vitro ventilation demonstrate that enhanced natural or forced air exchange substantially increases biomass accumulation, photosynthetic rates, and overall plantlet vigor by alleviating CO2 limitation inside culture vessels [28]. This physiological principle aligns with more recent findings showing that TIS, by improving gaseous exchange, prevent chlorosis, reduce hyperhydricity, and promote higher multiplication rates as compared with closed or poorly ventilated systems [47,51].

Finally, the role of immersion control and support materials in liquid systems has been emphasized as a strategy to further reduce the incidence of physiological disorders. The incorporation of inert supports, such as rockwool or similar substrates, improves explant positioning and aeration, significantly reducing hyperhydricity and enhancing shoot quality in liquid cultures [50,51]. Moreover, controlled immersion frequency and duration are critical parameters, as short immersion cycles maximize shoot proliferation and morphophysiological quality, whereas prolonged immersion leads to excessive hydration and stress responses [52,53]. Collectively, these studies provide a coherent framework supporting the superiority of temporary and intermittent immersion systems over permanent liquid and semi-solid cultures for efficient and physiologically balanced in vitro propagation.

Although having a low performance on the regenerative rate, the LQ-H and LQ-GE treatments were the only permissive conditions for root induction on shoots, significantly enhanced by the gas exchange (16.25 roots/plantlet). Except for the TI-TF, which had only 0.25 roots/shoot, no roots were observed in the other treatments. The vermiculite does not add nutrients to the culture environment, but due to its enhanced cation exchange capability, especially with divalent cations, essential medium macronutrients like Mg and Ca and micronutrients such as Co and Cu can be strongly adsorbed by the phyllosilicate surfaces until a solution equilibrium is reached [54,55].

Owing to the clear sprout and shoot development difficulties of the plants cultivated in vermiculite, it is reasonable to assume that these may be due to nutrient depletion, in a manner similar to what was observed when A. xanthorrhiza plants were exposed to activated charcoal in the culture medium [11].

Anyhow, the nutrient reduction seems to promote shoot rooting. The pattern of the growth regulators in a vermiculite substrate is unknown. Still, a charge-mediated restriction of cytokinin might be a feasible hypothesis, as long as the use of such an environment for final rooting of TI-scaled-up plants along with GE in a complementary way is a test worth making [56].

Hyperhydricity was observed only in cultures in TIS, with no differences among them (8.33%; Table 2), being perceptible on the petioles and limbs of the leaves, along with prominent hypertrophic deformations. Plantlets from TI-TF plants presented the highest fresh mass, followed by TI-RITA® plantlets. The other treatments showed no significant and visual hyperhydricity. Regarding dry matter/water content, all treatments showed no differences, indicating, as in the GE experiments, that plants did not enhance autotrophy or carbon fixations.

After the experimental period, plantlets cultivated in the bioreactor systems (TI-RITA® and TI-TF) were transferred to the rooting phase by replacing the culture medium. The basal salts and vitamins were maintained, while the cytokinin was omitted, and the medium was supplemented with 3 µM NAA and 0.7 µM GA3 to promote root initiation. Over the subsequent 20 days, a high incidence of hyperhydricity and tissue oxidation was observed in plants derived from both bioreactor systems, resulting in limited root development and reduced survival rates. In contrast, plantlets previously cultivated in gelled medium responded positively under the same rooting conditions.

These findings suggest that the physiological status of bioreactor-grown plantlets, potentially associated with excessive water uptake and reduced structural integrity, may influence their response during the rooting phase. Notably, the higher fresh mass observed in TI-grown plants, without a corresponding increase in dry mass, indicates possible internal hyperhydration not readily visible macroscopically, warranting further histological investigation. Adjustments to immersion times, aeration levels, and medium renewal frequency have been proposed in the literature [56,57] and may enhance acclimatization and improve rooting efficiency under photoautotrophic conditions.

Among the bamboo studies, TIS showed consistently positive effects, especially in Guadua angustifolia [58] and Bambusa vulgaris [53]. In G. angustifolia, the RITA® system increased shoot multiplication to 2.7–3.0 shoots per explant when four 2 min immersions per day were used, also improving rhizome development compared with semi-solid medium. For B. vulgaris, optimized temporary immersion at 2 min intervals with 6.6 μM 6-BAP enhanced shoot number, length, leaf expansion, chlorophyll content, and biochemical stability, whereas excessive immersion (3 min) caused 100% hyperhydricity. García et al. [59] demonstrated that temporary immersion reduced oxidative stress, improved stomatal morphology, increased pigments, and raised ex vitro survival to over 94% in B. vulgaris micropropagated plantlets.

In Coffea arabica, more somatic embryos in RITA® were observed than on semi-solid medium, reaching 94,222 embryos from callus densities of 0.005 g/cm3 under 3 min immersions every 6 h [60]. Similarly, Yoas and Johannes [61] confirmed that RITA® outperformed the semi-solid culture by increasing embryo yield, improving resource use, and reducing production time, though no photosynthesis was assessed. In Cannabis sativa, RITA® improved proliferation rate and shoot length and reduced culture time from six to four weeks, with the best treatment being 1 min immersion every 8 h using medium with low sucrose [49]. Although reduced sucrose suggested a shift toward photoautotrophy, photosynthesis was not measured. These studies confirm that monocots respond strongly to TIS, with increases in multiplication, growth quality, and operational efficiency.

Several woody and ornamental species also showed positive responses to temporary immersion systems. In Anthurium andraeanum, RITA® increased shoot initiation three- to four-fold and boosted proliferation by up to 2.6 times, with the best treatment being 5 min immersion, 20 mL medium per explant, and 2 h rest periods [62]. Hybrid chestnut (Castanea spp.) showed successful proliferation of apical, nodal, and basal segments with 1–3 min immersions repeated three to six times per day. However, performance varied among clones, and hyperhydricity was an issue for some genotypes [51]. In Piper aduncum, De Sousa et al. [63] described somatic embryo-derived plantlets reached 100% germination in RITA® with 3 min immersions every 6 h.

Comprehensive reviews reinforce these species-level findings. TIS—including RITA®—consistently improved multiplication rates, reduced production time, and enhanced acclimatization across multiple genera, such as Eucalyptus, Pistacia, Castanea, Psidium, and Malus [20,57]. Optimal treatments typically involved lower immersion frequencies (for example, every 12–16 h), which limited hyperhydricity while maintaining growth. The main disadvantages were excessive immersion, high cytokinin levels, and vessel limitations. The review also emphasizes that nearly 80% of studies reported hyperhydricity as a recurring problem, especially in pistachio and Eucalyptus, when immersion cycles were too frequent. As with almost all species-specific papers, no photosynthesis was detected or measured in the TIS context.

Across the species for which TIS were evaluated, including Guadua angustifolia [58], Bambusa vulgaris [59], Coffea arabica [60], Cannabis sativa [49], Anthurium andraeanum [62], Castanea spp. [51], and Piper aduncum [63], the reported positive effects were increased shoot multiplication, improvements in morphological quality, greater nutrient uptake, higher physiological stability, more efficient use of culture medium, and enhanced acclimatization. Although specific advantages varied by species and protocol, these studies consistently demonstrate that temporary immersion is an effective tool for improving micropropagation outcomes. Photosynthesis was measured only in Salix viminalis, where sucrose-free culture in a temporary immersion system supported autotrophic growth and active photosynthetic functioning [47]. However, disadvantages included hyperhydricity at high immersion frequencies, genotype-dependent sensitivity, vessel height limitations, and the need for precise optimization of immersion duration and frequency.

3.3. Stomata Densities and Behavior in Hermetic and Gas Exchange Conditions

Data presented in Table 3 indicate that stomatal density was strongly influenced by cultivation systems, with semi-solid hermetic cultures presenting a higher density (306 stomata mm2) than liquid hermetic cultures (215 stomata mm2). Both the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces were examined microscopically, but stomata were observed only on the abaxial epidermis, consistent with the hypostomatic pattern commonly reported for Apiaceae species such as carrot (Daucus carota), celery (Apium graveolens), and parsley (Petroselinum crispum) in which stomatal distribution is predominantly on the abaxial leaf surface [64,65,66]. This pattern aligns with the understanding that environmental structure drives stomatal differentiation, as suggested by Kozai and Kubota [67] and Etienne and Berthouly [12], who describe how gas composition, humidity, and medium type shape morphophysiological traits in micropropagated plants. The higher density observed under semi-solid conditions may reflect a developmental response to reduced mechanical submersion, suggesting that physical stability and microenvironmental constraints contribute to stomatal formation.

Table 3.

Stomatal density, leaf area, and relative stomata per area in A. xanthorrhiza semi-solid (Ss) and liquid (Lq) cultures under hermetic, passive and active gas exchange regimes in bioreactors.

When gas exchange was introduced, stomatal density increased in both semi-solid (349 mm2) and liquid cultures (241 mm2), reinforcing the importance of CO2 renewal and moderated humidity in promoting stomatal development. These results parallel the findings of Guo et al. [68], who emphasize that stomatal traits directly influence carbon assimilation, and Yang et al. [69], who show that increased stomatal density under higher light enhances photosynthetic capacity. In this sense, the rise in stomatal density under ventilated systems may represent a physiological adjustment that prepares shoots for improved ex vitro photosynthesis.

Consensus in the literature [19,70,71] is that micropropagated plants cultivated in hermetically sealed vessels exhibit a markedly higher stomatal density than those grown in systems that permit gas exchange because the closed microenvironment alters epidermal differentiation through simultaneous effects on humidity, CO2 concentration, and ethylene accumulation. Hermetic systems trap ethylene and other volatiles, and ethylene specifically disrupts epidermal patterning, increasing stomatal initiation and cell division in developing leaves [70]. In the absence of ventilation, relative humidity approaches saturation, which suppresses normal cuticle formation and weakens water-loss signaling, leading leaves to produce more stomata, many of which are structurally abnormal and poorly functional; the data are aligned with Silveira et al. [72], who report that ventilation reduces ethylene buildup and improves stomatal responsiveness.

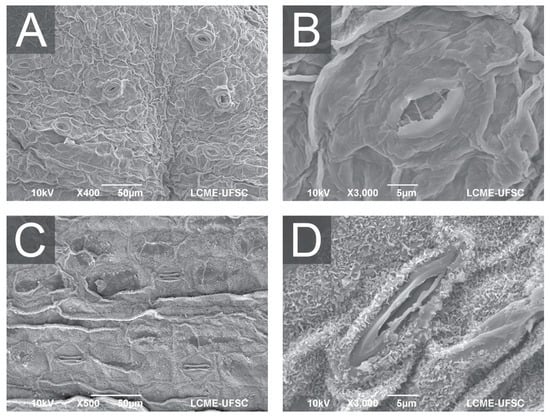

Under gas exchange, photosynthesis rapidly consumes the limited CO2 inside the vessel, exposing leaf primordia to chronic CO2 depletion, a stimulus well known to induce increased stomatal formation as a compensatory mechanism to improve CO2 capture. Under such conditions, stomatal initials are formed in excess, producing leaves with numerous, irregular, and often permanently open pores rather than fewer, highly functional stomata. Also, closed and non-functional stomata are very frequently observed in micropropagated plants [73] with hypertrophic and circular guard cells, as seen in Figure 4A, a phenotype associated with poor functionality in the literature. This phenotype is consistent with the alterations described by Majada et al. [74] and Wang et al. [75], in which in vitro-rooted plantlets displayed stomatal densities more than twice those of ex vitro-rooted plants, accompanied by enlarged guard cells, thin epidermal layers and impaired stomatal closure, reflecting impaired turgor regulation [76], emphasizing that impaired stomatal kinetics can dramatically reduce carbon assimilation under fluctuating light. Our observations confirm that hermetic conditions compromise stomatal architecture, likely reducing photosynthetic efficiency. In contrast, systems allowing passive or forced gas exchange maintain lower humidity, adequate CO2 availability and reduced ethylene concentration, enabling leaves to form fewer stomata that are structurally normal and physiologically functional. Studies using vented lids and forced-air culture systems have demonstrated that gas exchange reduces ethylene concentrations by more than twenty-fold and leads to the formation of fewer, morphologically uniform stomata closely resembling those of acclimatized plants [44].

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of A. xanthorrhiza leaves showing general aspect and distribution of open stomata in leaves from hermetic vessel (A), detail of opened stomata (B), general aspect and distribution of stomata in leaves from temporary immersion bioreactor with twin flasks (C), and detail of partially opened stomata (D).

Furthermore, Ziv [70] described how such environments cause weak stomatal control and thin cuticles, while Garvita and Wawangningrum [71] described deficiencies in wax deposition and epidermal development. The SEM images (Figure 3) confirm these trends, as plants from hermetic conditions display malformed stomata with compromised function, which would likely restrict CO2 uptake and photoprotective control. As a result, cultures grown without gas exchange presented more stomata per unit area but with impaired guard-cell morphology and reduced stomatal regulation. When gas exchange is absent, photosynthetic activity quickly consumes the limited CO2 within the vessel, generating a low-CO2 atmosphere that plants interpret as a condition requiring greater stomatal production to maximize carbon acquisition. This compensatory response has been widely demonstrated, including studies showing that near-zero CO2 diffusion in closed vessels directly stimulates stomatal hyperproliferation [77,78]. At the same time, the hermetic environment maintains relative humidity at saturation, preventing the formation of a physiologically functional cuticle and deregulating epidermal patterning.

Liquid medium, especially when combined with vermiculite, produces larger but fewer stomata, corresponding to the visual patterns in Figure 4B,D. This size–density trade-off resembles the patterns described by Murage [79] and Kumari et al. [80], who show that stomatal density may not correlate directly with photosynthetic capacity. Larger stomata may achieve higher maximum conductance but typically operate more slowly [81], and Wu et al. [82] note that slow stomatal kinetics hinder rapid photosynthesis induction. Thus, this trait in your liquid-grown plants may represent a disadvantage under real environmental fluctuations. Ventilation, in contrast, restores environmental cues that suppress excessive stomatal formation by normalizing CO2 availability, reducing excessive humidity, and preventing the accumulation of volatiles that interfere with epidermal development. Improved CO2 diffusion not only prevents unnecessary stomatal proliferation but also enhances chlorophyll accumulation, mesophyll differentiation, and vascular development, which reinforce functional stomatal regulation. As a result, plantlets cultured with gas exchange develop stomata but are more effective in balancing water loss and CO2 uptake upon transfer to ex vitro conditions. Taken together, the literature consistently [44,74,75] demonstrates that higher stomatal density in non-ventilated micropropagated plants is not an adaptive advantage but a stress-induced response arising from humidity saturation, carbon limitation, and volatile buildup. In contrast, ventilated systems restore developmental stability and produce leaves with appropriate stomatal numbers and functional physiology.

Despite these shifts in density, the proportion of leaf area containing stomata remains relatively constant across treatments (13.27–20.69%), suggesting that stomatal spatial distribution is preserved [48]. Bag et al. [48] describe that micropropagated plants maintain similar gas exchange performance despite lower stomatal frequencies compared with seedlings. Hassan et al. [73] noted that stomatal coverage can remain stable even when photosynthetic changes occur. Our findings, therefore, suggest that stomatal area coverage may serve as a stabilizing factor for gas exchange capacity despite anatomical variation.

In addition, in the present study, shoots cultured in TIS (Twins Flasks and RITA) produce stomata with normal morphology (Figure 3C,D) and densities similar to semi-solid systems (284–288 mm2). These results demonstrate that bioreactors restore stomatal integrity [12,40], suggesting that periodic aeration improves water status, photosynthetic capacity, and stomatal physiology in vitro. The functional stomata produced under these conditions suggest better adaptation potential and improved CO2 diffusion pathways. Viewed collectively, our data support the conclusion that increased stomatal density enhances the potential for higher photosynthesis only when stomatal structure and functionality are preserved. Yang et al. [69] report that high stomatal density increases net photosynthesis in bamboo only when accompanied by appropriate hydraulic adjustments, and Bag et al. [48] show that micropropagated shoots can achieve similar photosynthesis even with lower density when stomatal function is intact. In our system, ventilated treatments combine moderate-to-high density with full functionality, making them the most favorable for photosynthesis.

Finally, our results clearly indicate that improving photosynthesis in micropropagated A. xanthorrhiza depends not only on increasing stomatal number but also on fostering well-formed, responsive stomata capable of regulating CO2 influx under real environmental conditions.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Previous studies have shown that ventilated and photoautotrophic in vitro systems can reduce culture time, improve light-use efficiency, enhance ex vitro survival, and increase productivity per unit area, which are effects consistently attributed to improved photosynthetic performance. These findings highlight the central role of gas exchange in improving the physiological quality of micropropagated plantlets.

In this context, the results of the present study demonstrate that gas exchange and TIS can induce morphophysiological adaptations in Arracacia xanthorrhiza that favor ex vitro establishment, particularly by promoting the development of more normal, functionally similar stomata, which are typically absent under hermetic culture conditions. Given that stomatal functionality is a key determinant of photosynthetic competence, these responses are critical for successful acclimatization.

However, the contrasting performance observed among semi-solid, liquid, and TIS indicates that further optimization is still required. Improvements in nutrient availability, hormonal balance, and aeration dynamics are necessary to enhance shoot regeneration, control hyperhydricity, and improve the physiological readiness of plantlets. Liquid cultures subjected to gas exchange were particularly effective in promoting root induction. In contrast, passive gas exchange and TIS require additional refinement for this species when compared with gelled culture protocols. Considering the strong system- and inedibility species-dependence reported in the literature, future studies should focus on salt and sucrose reduction, cytokinin–auxin balance during multiplication and rooting, and the optimization of aeration flux and immersion time regimes to establish a robust and scalable mass clonal propagation protocol for A. xanthorrhiza.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12020176/s1. Figure S1: Operating Principle of the Microsac Filter.

Author Contributions

P.D.M.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation; M.R.F.: methodology, data curation, formal analysis; É.C.M.: methodology, investigation; Y.F.: methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation; C.A.C.: methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation; V.M.S.: validation, visualization, writing—review and editing; M.F.P.: data curation, visualization, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, supervision; M.P.G.: conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, data curation, validation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). Grants 304522/2023-6, and 407974/2018-0.

Data Availability Statement

All data were uploaded and are available for unrestricted access at https://1drv.ms/x/c/90670d53d2ee7f18/IQBgfO0vleUfQZC-HuvZOj0eAWAZDJfff6dopFqjiSlxghY?e=BLO6Te.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Andrade, N.J.P.; Sevillano, R.H.B.; Sørensen, M. Traditional uses, processes, and markets: The case of arracacha (Arracacia xanthorrhiza Bancroft). In Traditional Starch Food Products: Application and Processing, 4th ed.; Cereda, M.P., Vilpoux, O.F., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2025; pp. 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies). Scientific Opinion on the safety of Arracacia xanthorrhiza as a novel food. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Portillo, S.; Salazar-Sánchez, M.D.R.; Campos-Muzquiz, L.G.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Lopez Badillo, C.M.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R. Proximal characteristics, phenolic compounds profile, and functional properties of Ullucus tuberosus and Arracacia xanthorrhiza. Explor. Foods Foodomics 2024, 2, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo, E.; Sécond, G. Tracing the domestication of the Andean root crop arracacha (Arracacia xanthorrhiza Bancr.): A molecular survey confirms the selection of a wild form apt to asexual reproduction. Plant Genet. Resour. 2017, 15, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, N.R. Micropropagação e Indexação de Mandioquinha-Salsa; Universidade Federal de Lavras: Lavras, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Henz, G.P. Doenças da mandioquinha-salsa e sua situação atual no Brasil. Hort. Bras. 2002, 20, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, N.R.; Carvalho, A.D.F.; Silva, G.O.; Brotel, N.; Bortoletto, A.C. Mandioquinha-Salsa Arracacia xanthorrhiza Bancroft; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Embrapa. Mandioquinha-Salsa (Arracacia xanthorrhiza). Available online: https://sistemasdeproducao.cnptia.embrapa.br/FontesHTML/Mandioquinha/MandioquinhaSalsa/apresentacao.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Mesquita Filho, M.V.; Souza, A.F.; Silva, H.R.; Santos, F.F.; Oliveira, S.A. Adubação nitrogenada e fosfatada para produção comercializável de mandioquinhasalsa em latossolo vermelho amarelo. Hortic. Bras. 1996, 14, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Alencar, G. Cientistas Desenvolvem Variedades de Mandioquinha-Salsa Que Produzem até 80% Mais Que a Cultivar Tradicional. Available online: https://www.embrapa.br/busca-de-noticias/-/noticia/33407934/cientistas-desenvolvem-variedades-de-mandioquinha-salsa-que-produzem-ate-80-mais-que-a-cultivar-tradicional (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Marques, P.D.; Ornellas, T.S.; Fritsche, Y.; Mund, I.F.; Caprestano, C.A.; Stefenon, V.M.; Pompelli, M.F.; Guerra, M.P. New approaches on micropropagation of Arracacia xanthorrhiza (“Arracacha”): In vitro establishment, senescence reduction and plant growth regulators balance. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, H.; Berthouly, M. Temporary immersion systems in plant micropropagation. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2002, 69, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, V.; Schumann, A.; Pavlov, A.; Bley, T. Temporary immersion systems in plant biotechnology. Eng. Life Sci. 2014, 14, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, O.L.; Miller, R.A.; Ojima, K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1968, 50, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo de Pinna, G.F.A.; Kraus, J.E.; Menezes, N.L. Morphology and anatomy of leaf mine in Richterago riparia Roque (Asteraceae) in the campos rupestres of Serra do Cipó, Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 2002, 62, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voesenek, L.A.; Sasidharan, R. Ethylene and oxygen signalling drive plant survival during flooding. Plant Biol. 2013, 3, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, S.M. Effects of ethylene inhibitors, silver nitrate (AgNO3), cobalt chloride (CoCl2) and aminooxyacetic acid (AOA), on in vitro shoot induction and rooting of banana (Musa acuminata L.). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 2511–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenza, M.; Umiel, N.; Borochov, A. The involvement of ethylene in the senescence of ranunculus cut flowers. Postharvest Biol. Tec. 2000, 19, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, B.N. Morphophysiological disorders in in vitro culture of plants. Sci. Hort. 2006, 108, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.S.O.; Stein, V.C.; Santos, B.R.; Paiva, L.V. Temporary immersion systems in the micropropagation of forest species: A review. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2019, 47, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello-Bello, J.J.; Mancilla-Álvarez, E.; Spinoso-Castillo, J.L. Scaling-up procedures and factors for mass micropropagation using temporary immersion systems. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Plant 2025, 61, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abahmane, L. A comparative study between temporary immersion system and semi-solid cultures on shoot multiplication and plantlets production of two Moroccan date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) varieties in vitro. Not. Sci. Biol. 2020, 12, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Paek, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Bioreactor systems for micropropagation of plants: Present scenario and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1159588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feizi, F.; Mousavi, M.; Chehrazi, M. Possibility of using glass beads as a support matrix for plant micropropagation in temporary immersion bioreactors. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 11, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staba, E.J. Plant tissue culture as a technique for the phytochemist. In Recent Advances in Phytochemistry; Seikel, M.K., Runcekles, V.C., Eds.; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1969; Volume 2, pp. 75–106. [Google Scholar]

- Skirvin, R.M.; Chu, M.C. In vitro culture of ‘Forever Yours’ rose. HortScience 1979, 14, 608–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SACO2. Tissue Culture Boxes with Different Filter Options. Available online: https://saco2.com/microbox-filter-options/ (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Kubota, C.; Kozai, T. Growth and net photosynthetic rate of Solanum tuberosum in vitro under forced and natural ventilation. HortSci 1992, 27, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, S.L.; Vidave, W. Photosynthetic competence of plantlets grown in vitro. An automated system for measurement of photosynthesis in vitro. Physiol. Plant 1992, 84, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Kozai, T.; Kubota, C. A system for measuring the in situ CO2 exchange rates of in vitro plantlets. HortSci 1998, 33, 1076–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompelli, M.F.; Martins, S.C.; Celin, E.F.; Ventrella, M.C.; DaMatta, F.M. What is the influence of ordinary epidermal cells and stomata on the leaf plasticity of coffee plants grown under full-sun and shady conditions? Braz. J. Biol. 2010, 70, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Rueden, C.T.; Hiner, M.C.; Eliceiri, K.W. The ImageJ ecosystem: An open platform for biomedical image analysis. MoL Reprod. Dev. 2015, 82, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnovsky, M.J. A formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative of high osmolality for use in electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 1965, 27, 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Han, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Lv, Q.; Pompelli, M.F.; Pereira, J.D.; Araújo, W.L. Long exposure to salt stress in Jatropha curcas leads to stronger damage to the chloroplast ultrastructure and its functionality than the stomatal function. Forest 2023, 14, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Isla, F.; Alfaro, O.B.; Pompelli, M.F. GerminaR: An R package for germination analysis with the interactive web application ‘GerminaQuant for R’. Ecol. Res. 2019, 34, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddington, N.L. The influence of ethylene in plant tissue culture. Plant Growth Regul. 1992, 11, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Parvatam, G.; Ravishankar, G.A. AgNO3: A potential regulator of ethylene activity and plant growth modulator. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 12, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xia, X.; An, L.; Xin, X.; Liang, Y. Reversion of hyperhydricity in pink (Dianthus chinensis L.) plantlets by AgNO3 and its associated mechanism during in vitro culture. Plant Sci. 2017, 254, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaya, Y.; Ohmura, Y.; Kubota, C.; Kozai, T. Manipulation of the culture environment on in vitro air movement and its impact on plantlets photosynthesis. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2005, 83, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozai, T. Photoautotrophic micropropagation-environmental control for promoting photosynthesis. Propag. Ornam. Plants 2010, 10, 188–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kozai, T. Photoautotrophic micropropagation. In Automation and Environmental Control in Plant Tissue Culture; Aitken-Christie, J., Kozai, T., Smith, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 313–343. [Google Scholar]

- Zobayed, S.M.A.; Afreen-Zobayed, F.; Kubota, C.; Kozai, T. Stomatal characteristics and leaf anatomy of potato plantlets cultured in vitro under photoautotrophic and photomixotrophic conditions. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Plant 1999, 35, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, C. Physical properties of culture vessels for plant tissue culture. Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 91, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobayed, S.M.A.; Armstrong, J.; Armstrong, W. Micropropagation of potato: Evaluation of closed, diffusive and forced ventilation on growth and tuberization. Ann. Bot. 2001, 87, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.; Scherer, R.F.; Holderbaum, D.F.; Guerra, M.P.; Steiner, N. Combined effects of cultivar, culture system, cytokinin type and concentration on in vitro regenerative rate of banana. Plant Cell Cult. Micropropag. 2021, 17, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.F.; Garcia, A.G.; Fraga, H.P.F.; Dal Vesco, L.L.; Steinmacher, D.A.; Guerra, M.P. Nodule cluster cultures and temporary immersion bioreactors as a high performance micropropagation strategy in pineapple (Ananas comosus var. comosus). Sci. Hort. 2013, 151, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, D.; Vilavert, S.; Bernal, M.Á.; Sánchez, C.; Aldrey, A.; Vidal, N. The effect of sucrose supplementation on the micropropagation of Salix viminalis L. shoots in semisolid medium and temporary immersion bioreactors. Forest 2021, 12, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, N.; Chandra, S.; Palni, L.M.S.; Nandi, S.K. Micropropagation of Devringal [Thamnocalamus spathiflorus (Trin.) Munro]—A temperate bamboo, and comparison between in vitro propagated plants and seedlings. Plant Sci. 2000, 156, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, S.; Garrido, J.; Sánchez, C.; Ferreiro-Vera, C.; Codesido, V.; Vidal, N. A temporary immersion system to improve Cannabis sativa micropropagation. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, e895971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San José, M.C.; Blázquez, N.; Cernadas, M.J.; Janeiro, L.V.; Cuenca, B.; Sánchez, C.; Vidal, N. Temporary immersion systems to improve alder micropropagation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2020, 143, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.; Blanco, B.; Cuenca, B. A temporary immersion system for micropropagation of axillary shoots of hybrid chestnut. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2015, 123, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heringer, A.S.; Steinmacher, D.A.; Fraga, H.P.F.; Vieira, L.N.; Montagna, T.; Quinga, L.A.P.; Quoirin, M.G.G.; Jiménez, V.M.; Guerra, M.P. Improved high-efficiency protocol for somatic embryogenesis in peach palm (Bactris gasipaes Kunth) using RITA® temporaryimmersion system. Sci. Hort. 2014, 179, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ramírez, Y.; Freire-Seijo, M.; Barbón, R.; Torres-garcía, S. Efecto del 6-BAP y el tiempo de inmersión en la multiplicación de brotes de Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex Wendl en sistemas de inmersión temporal. Biotecnol. Apl. 2021, 38, 3201–3205. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, A.; Keay, J. Cation-exchange equilibria with vermiculite. J. Soil. Sci. 1964, 15, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.G.; Oliveira, M.M.; Arakaki, L.N.; Espinola, J.G.; Airoldi, C. Natural vermiculite as an exchanger support for heavy cations in aqueous solution. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2005, 285, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.; Sánchez, C. Use of bioreactor systems in the propagation of forest trees. Eng. Life Sci. 2019, 19, 896–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Businge, E.; Trifonova, A.; Schneider, C.; Rödel, P.; Egertsdotter, U. Evaluation of a New Temporary Immersion Bioreactor System for Micropropagation of Cultivars of Eucalyptus, Birch and Fir. Forests 2017, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, L.G.; López-Franco, R.; Morales-Pinzón, T. Micropropagation of Guadua angustifolia Kunth (Poaceae) using a temporary immersion system (RITA®). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 15, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Y.Y.; Barrera, G.P.; Freire, M.; Barbón, R.; Torres, S. Anatomical and biochemical responses to oxidative stress in shoots of Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex Wendl during the in vitro–ex vitro transition. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwaniki, I.W. Optimising Somatic Embryos Formation in Coffea arabica Cultivar Ruiru 11 Using Temporary Immersion Systems in Kenya. Master’s Thesis, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture And Technology, Juja, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yoas, A.I.L.; Johannes, E. Somatic embryogenesis of arabica coffee (Coffea arabica var. Lini-S 795) from Toraja by in vitro with the additional of 2, 4-Dichlorophenoxyacetid Acid (2, 4-D) and 6 Furfurylamino Purine (Kinetin). Acad. Res. Intern. 2021, 12, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Uy, J.N.R. Rapid In Vitro Multiplication of Anthurium Using Temporary Immersion System (RITA®); University of Hawaii at Mānoa: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, P.C.A.; Souza, S.S.S.E.; Meira, F.S.; Meira, R.O.; Gomes, H.T.; Silva-Cardoso, I.M.A.; Scherwinski-Pereira, J.E. Somatic embryogenesis and plant regeneration in Piper aduncum L. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Plant 2020, 56, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, C.R.; Chalk, L. Anatomy of the dicotyledons, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Evert, R.F. Esau’s Plant Anatomy: Meristems, Cells, and Tissues of the Plant Body: Their Structure, Function, and Development; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.J.; Luo, Q.; Li, T.; Meng, P.H.; Pu, Y.T.; Liu, J.X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Tan, G.F.; Xiong, A.S. Origin, evolution, breeding, and omics of Apiaceae: A family of vegetables and medicinal plants. Hortic. Res. 2022, 11, uhac076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozai, T.; Kubota, C. Developing a photoautotrophic micropropagation system for woody plants. J. Plant Res. 2001, 114, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Cherubini, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, M.-H.; Qi, L. Leaf stomatal traits rather than anatomical traits regulate gross primary productivity of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) stands. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1117564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Cochard, H.; Cao, K.-F. Strong leaf morphological, anatomical, and physiological responses of a subtropical woody bamboo (Sinarundinaria nitida) to contrasting light environments. Plant Ecol. 2014, 215, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, M. Quality of micropropagated plants—vitrification. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Plant 1991, 27, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvita, R.V.; Wawangningrum, H. Stomata cells studies of Paraphalaenopsis spp. from in vitro and greenhouse condition. Biodiversitas 2020, 21, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, A.A.C.; Lopes, F.J.F.; Sibov, S.T. Micropropagation of Bambusa oldhamii Munro in heterotrophic, mixotrophic and photomixotrophic systems. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2020, 141, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Setiawati, T.; Nurzaman, M.; Nopriyeni, N. The stomatal characteristics of monocots and dicots at different altitudes. Plant Sci. Today 2025, 12, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majada, J.P.; Tadeo, F.; Fal, M.A.; Sánchez-Tamés, R. Impact of culture vessel ventilation on the anatomy and morphology of micropropagated carnation. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. Cult. 2000, 63, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xin, X.; Wei, H.; Qiu, X.; Liu, B. IIn vitro regeneration, ex vitro rooting and foliar stoma studies of Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax. Agronomy 2020, 10, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyland, D.; van Wesemael, J.; Lawson, T.; Carpentier, S. The impact of slow stomatal kinetics on photosynthesis and water use efficiency under fluctuating light. Plant Physiol. 2021, 186, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, A.R.; Van Meeteren, U. Stomatal response characteristics of Tradescantia virginiana grown at high relative air humidity. Physiol. Plant 2005, 124, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospišilová, J.; Tichá, I.; Kadleček, P.; Haisel, D.; Plzáková, Š. Acclimatization of micropropagated plants to ex vitro conditions. Biol. Plant 1999, 42, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murage, H. Mass Propagation of Bamboo, and Its Adaptability to Waste Water Gardens. Ph.D. Thesis, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Juja, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, A.; Devi, K.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, R.K.; Joshi, R. Optimization of an efficient micropropagation system from the axillary buds of Phyllostachys pubescens: Chinese moso bamboo. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Plant, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsie, B.S.; Mendes, K.R.; Antunes, W.C.; Endres, L.; Campos, M.L.O.; Souza, F.C.; Santos, N.D.; Singh, B.; Arruda, E.C.P.; Pompelli, M.F. Jatropha curcas L. (Euphorbiaceae) modulates stomatal traits in response to leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficit. Biomass Bioenerg. 2015, 81, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.P.; Gao, X.; Zhang, R.; Luan, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S. Nitrogen addition alleviates water loss of Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) under drought by affecting light-induced stomatal responses. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 938, 173615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.