Abstract

This study evaluated the performance of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) cultivated in coupled aquaponic systems integrated with Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) under tropical greenhouse conditions. The experiment was conducted across two consecutive lettuce production cycles to assess fish growth, plant performance, water quality, and nutrient dynamics. African catfish exhibited significantly higher specific growth rates (1.08 ± 0.18%/day; p = 0.02) and weight gain (92.38 ± 22.29%; p = 0.03) compared with tilapia. During the first lettuce cycle, tilapia-based systems yielded significantly higher final plant weights (177.6 ± 34.4 g/plant; p = 0.0002), and greater increases in leaf number, weight gain, and absolute growth rate than catfish-based systems. However, in the second cycle, catfish systems resulted in superior lettuce leaf morphology, with significantly greater leaf length, width, and total leaf area. Nutrient profiles differed markedly between systems. In the deep-water culture (DWC) units, total phosphorus (TP) concentrations were significantly higher in the tilapia-based system during cycle 1 (12.39 ± 0.64 mg/L; p = 0.0001), while total nitrogen (TN) concentrations were significantly higher in the catfish treatment during cycle 2 (21.54 ± 2.93 mg/L; p = 0.0007). Catfish-based systems also showed higher levels of calcium and sodium. Despite these differences, temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen remained within optimal ranges for aquaponic production across both systems. Overall, tilapia-based aquaponics promoted faster early-cycle plant growth and higher initial yield, whereas catfish-based systems enhanced nitrogen availability and improved lettuce leaf structural development over successive cycles. These findings indicate that fish species selection plays a critical role in shaping nutrient dynamics and crop performance in tropical aquaponic systems.

1. Introduction

Climate change, soil degradation, and increasing water scarcity pose significant and interconnected threats to the sustainability of global food systems [1]. These challenges are further compounded by rapid population growth and accelerating urbanization, which continue to place mounting pressure on conventional agricultural production systems [2]. Addressing future food demand therefore requires innovative, resource-efficient farming strategies that enhance productivity while reducing reliance on finite land and water resources. In this context, soilless cultivation technologies, particularly aquaponic systems, have emerged as promising alternatives, offering enhanced water- and nutrient-use efficiency, reduced land requirements, and the capacity for year-round crop production in urban and peri-urban environments [3].

Aquaponics is an integrated farming system that combines the cultivation of aquatic organisms and plants, where the nutrient-rich effluent from the aquatic organisms undergoes bacterial transformation and is subsequently used to nourish the cultivated plants [4,5,6]. This approach aligns with sustainable agricultural goals and is increasingly being adopted in tropical regions to optimize water-, space-, and nutrient-use efficiency [6,7,8]. Among fish species used in tropical aquaponic systems, Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) and African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) are predominant due to their rapid growth rates, feed conversion efficiency, and high adaptability to variable environmental conditions [8,9]. Tilapia is well known for its high tolerance to suboptimal water quality and its ability to maintain steady ammonia and phosphorus excretion rates, which favour vegetative crops [10]. Conversely, C. gariepinus exhibit a more carnivorous feeding behaviour that influences organic matter decomposition and nitrogen mineralization, potentially enhancing nitrate accumulation in water [11].

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) is a shallow-rooted leafy vegetable with a short growth cycle and is widely used as a model crop in aquaponic research due to its low nutrient requirements, rapid biomass accumulation, and strong market demand [8,12]. Previous studies indicate that lettuce growth and physiological responses in aquaponic systems vary according to fish species, system management practices, and nutrient composition of the culture water [8,13]. For example, tilapia-based systems are often associated with enhanced early growth and higher chlorophyll content, likely due to increased phosphorus and ammonium availability, whereas catfish-based systems tend to promote greater leaf expansion and structural development in later production cycles, attributed to elevated nitrate concentrations [14]. Despite these observations, the existing aquaponic literature does not clearly establish whether nutrient excretion from different fish species results in significantly distinct nutrient profiles in the aquaponic solution or consistent differences in plant yield. A better understanding of these interactions is therefore essential for improving nutrient-use efficiency and enhancing overall aquaponic system productivity [13,14].

Previous studies have predominantly focused on lettuce performance in aquaponic systems, examining factors such as the effects of probiotics [2], pH regulation [15], the use of different nutrient solutions [16,17], microbial diversity in different compartments [18] and the yield and quality of crops cultivated under hydroponic and aquaponic conditions [19]. However, comparatively little attention has been given to the influence of fish species on lettuce growth in soilless production systems, particularly under tropical conditions. This knowledge gap limits the optimization of aquaponic system design and management for region-specific applications. It was hypothesized that tilapia effluents, which are richer in phosphorus and ammonium, would support greater early-cycle lettuce biomass, whereas African catfish effluents, through sustained nitrate availability, would enhance leaf morphology and size in later production cycles. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the performance of lettuce grown in recirculating aquaponic systems integrated with either Nile tilapia or African catfish under tropical greenhouse conditions. Specifically, it assessed (i) fish growth performance, (ii) nutrient dynamics and water quality, and (iii) plant growth parameters across two lettuce cycles. It was hypothesized that tilapia effluents, being richer in phosphorus and ammonium, would promote higher early-cycle lettuce biomass, whereas catfish effluents would enhance leaf morphology and size through sustained nitrate accumulation in later cycles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and System Setup

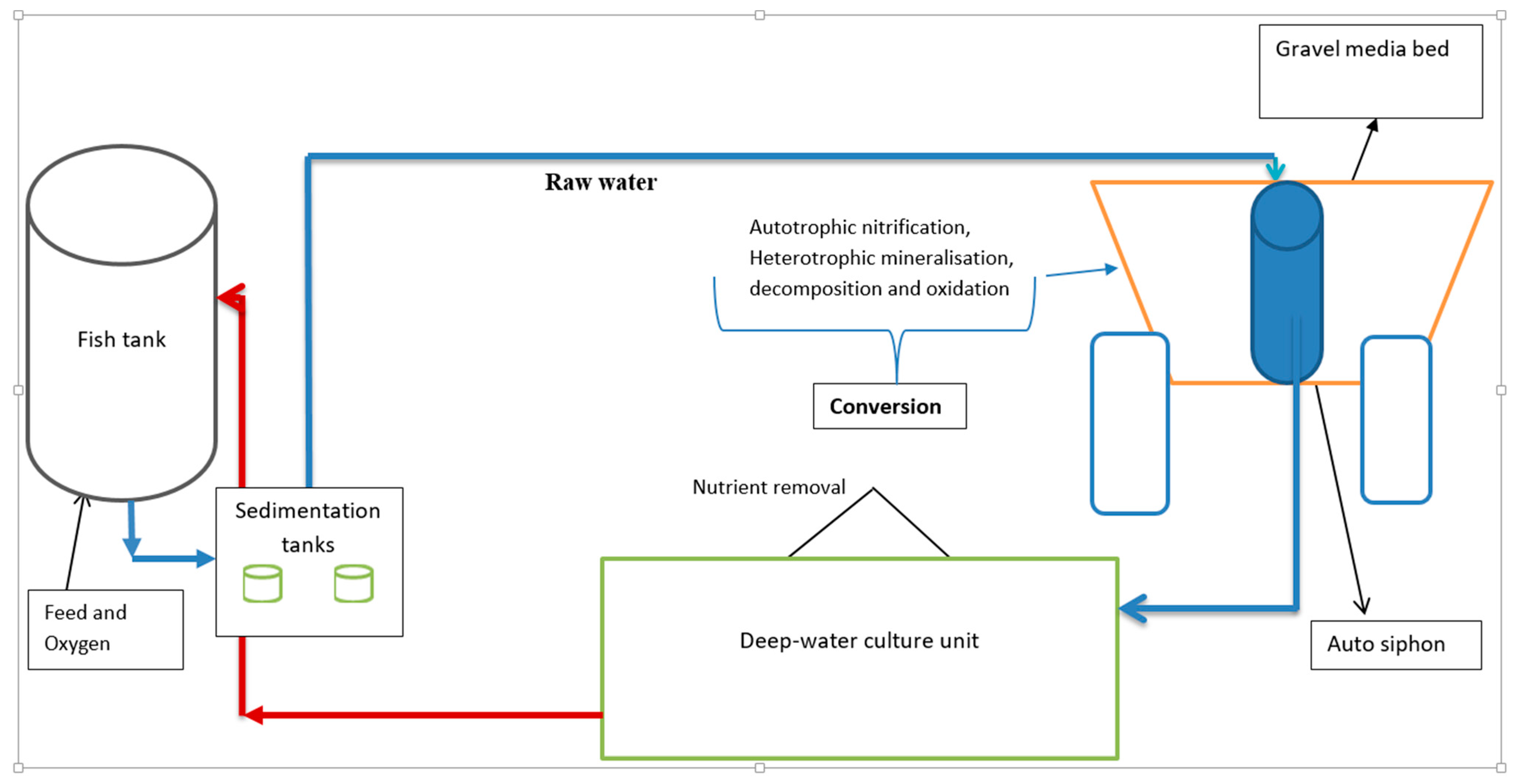

The experiment was conducted in a controlled tropical greenhouse at the National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI), Aquaculture Research and Development Centre in Kajjansi, Uganda (0°13′20″ N, 32°32′5″ E). The fish rearing period lasted 90 days. Six identical coupled aquaponic systems were established with a gravel bed and a deep-water culture (DWC) bed. A completely randomized design was used, with three replicate aquaponic systems randomly assigned to each treatment, namely tilapia (n = 3) and catfish (n = 3). Each system contained a fiberglass fish tank with a capacity of 1300 L, two sedimentation tanks, each with a capacity of 70 L, two ebb and flow gravel media beds, each with a capacity of 450 L, and a 900 L deep-water hydroponic culture unit (Figure 1). These units were connected by pipes to form a closed water cycle.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of a single experimental aquaponic unit and directions of flow of water. From the media bed, water drained into a deep-water hydroponic floating raft unit to achieve a water cycling rate of 4 cycles/h.

Water exiting the fish tank was fed by gravity to the sedimentation tanks, then to the gravel media bed at a flow rate of 216 L/h. As the water volume increased in the gravel bed (highest point), the water drained into a deep-water hydroponic unit to achieve a water cycling rate of 4 cycles/h at a flow rate of 214 L/h. From the hydroponic unit, water was pumped back to the fish rearing tank using a submersible pump (DAYLIFF, 0.25 kW, Nairobi, Kenya, imported from China) at a flow rate of 219 L/h, thereby completing the recirculating cycle.

The systems were aerated with air stones to maintain dissolved oxygen levels above 4 mg/L. Environmental conditions in the greenhouse were maintained at 25 ± 2 °C with a natural 12 h light: 12 h dark photoperiod. The sedimentation and gravel media grow-beds acted as mechanical and biological filters, respectively.

2.2. Fish Rearing Conditions

Juvenile fish were acclimatized for 14 days before the experiment commenced. Each 1300 L tank was stocked with 200 juvenile fish at average initial weights of 42.6 ± 0.55 g for Nile tilapia and 20.4 ± 0.70 g for African catfish. Fish were fed a commercial floating pellet (De Heus LL, Long Ho district, Vinh Long province, Vietnam) containing 37% crude protein, 11% moisture, 1.0% phosphorus, 5.5% crude fat, and 2.5% calcium. Feed was administered twice daily, at 09:00 h and 16:00 h. The daily feeding rate was maintained at 3% of fish body weight, adjusted fortnightly according to biomass gain. Feeding was carried out manually. Uneaten feed and solid wastes were siphoned daily, one hour after feeding, to prevent ammonia accumulation and maintain stable water quality. At the end of the 90-day culture period, 60 fish were sampled from each tank for the evaluation of growth performance. Fish performance was evaluated based on weight gain (WG), specific growth rate (SGR, %/day), daily weight gain (DWG, g), feed conversion ratio (FCR), and percentage survival rate (SR), as indicated in the following equations as described by Kasozi et al. [20].

WG = 100 × ((FW − IW)/IW)

SGR = ((ln FW − ln IW)/T) ×100

DWG = (FW − IW)/T

FCR = DM/BMG

SR = 100 × (Nf/Ni)

whereby:

FW = average final weight (g fish−1); IW = average initial weight (g fish−1); ln FW = the natural logarithm of the mean final weight; ln IW = the natural logarithm of the mean initial weight; T = number of days of the growth period; DM = dry matter of feed supplied (g); BMG = wet biomass gain (g); and Nf and Ni = final number and initial number of fish per tank, respectively.

2.3. Lettuce Cultivation and Management

Lettuce seeds were obtained from Holland Greentech, an agricultural input supplier in Uganda. The seeds were sown in 50-cell germination trays filled with peat moss as the growth medium. After sowing, the trays were thoroughly watered and covered with empty trays to enhance humidity and accelerate germination. Following seed emergence, the trays were uncovered and seedlings were maintained under nursery conditions with daily watering for four weeks. During this nursery period, no fertilizers or agrochemical sprays were applied. At four weeks after emergence, healthy and uniform seedlings were selected and transplanted onto floating rafts in each aquaponic deep-water culture (DWC) bed, at a spacing of 15 × 15 cm between plants. Each DWC bed contained 50 plants (Figure 2). Two successive 30-day growth cycles were conducted using nutrient-rich effluents from the respective fish systems. A total of 25 plants from each deep-water hydroponic unit were harvested, and growth was assessed by measuring initial and final fresh weight, weight gain, number of leaves, leaf length and width, leaf area, and absolute growth rate (AGR). Measurements were taken at harvest from representative plants within each replicate. The DWC beds were cleaned between cycles to minimize microbial contamination and maintain consistent nutrient exposure conditions.

Figure 2.

Overview of six aquaponic units integrating deep-water culture (DWC) beds planted with lettuce and gravel media beds supporting tomato cultivation.

Absolute growth rate (AGR) was calculated using the equation described by Kasozi et al. [21].

AGR = (M2 − M1)/T

whereby:

M2 = average final plant mass (g plant−1)

M1 = average initial plant mass (g plant−1)

T = number of days of the growth period

2.4. Water Sampling and Nutrient Analysis

Water samples were collected weekly from both fish tanks and DWC beds in sterilized polyethylene bottles taken between 08:30 h and 09:00 h. In situ measurements of temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDS) were taken using calibrated digital meters (Hanna HI-98194 multi-parameter, Cluj, Romania and YSI Pro20 dissolved oxygen meter, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). At the end of the two production cycles (60 days), nutrient analyses were carried out following standard procedures recommended by the American Public Health Association [22]. The parameters analysed included total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3−), nitrite (NO2−), and phosphate (PO4). Samples for mineral analysis were acidified with nitric acid and analysed using atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 400, Waltham, MA, USA) to determine iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na), and potassium (K) concentrations.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To avoid bias due to pseudo replication, values of individual fish per tank were averaged prior to analysis. Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and treatment mean differences were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the Statistica software package (TIBCO Software, Palo Alto, CA, USA, version 13.5.0).

3. Results

3.1. Fish Growth Performance

Fish growth performance varied significantly between Nile tilapia and African catfish systems over the 90-day culture period. The feed conversion ratio was superior in tilapia (FCR = 1.47 ± 0.02) compared to catfish (FCR = 1.64 ± 0.06; p = 0.01). The specific growth rate (SGR) was higher in African catfish (1.08 ± 0.18%/day) than in Nile tilapia (0.68 ± 0.30%/day; p = 0.02). Both species recorded survival rates above 85% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Fish growth parameters as means (±SD) between coupled aquaponic units with African Catfish and Nile tilapia. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, obtained from triplicate fish water tanks in the African catfish-based aquaponic system and the Nile tilapia-based aquaponic system. An asterisk (*) indicates means that are significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.2. Vegetative Growth of Lettuce

During the first lettuce growth cycle, plants in the tilapia-based aquaponic system demonstrated significantly improved growth performance compared to those in the African catfish systems (Table 2). Tilapia effluents supported higher final plant biomass (177.6 ± 34.4 g), greater weight gain (113.1 ± 38.0 g), and higher number of leaves (24.8 ± 6.3) than catfish effluents (141.5 ± 38.0 g, 73.3 ± 40.7 g, and 18.6 ± 3.4, respectively; p < 0.01). The absolute growth rate (AGR) was also higher in the tilapia system (4.04 ± 1.35 g/day) compared to catfish (2.6 ± 1.45 g/day; p = 0.0003).

Table 2.

Growth performance of lettuce observed in two growth trials. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, obtained from triplicate DWC beds in the African catfish-based aquaponic system and the Nile tilapia-based aquaponic system. An asterisk (*) indicates means that are significantly different at p < 0.05.

In the second crop cycle, however, lettuce grown in catfish-based systems exhibited improved morphological characteristics compared to tilapia systems. The leaf length (14.86 ± 1.58 cm), leaf width (11.81 ± 1.26 cm), and leaf area (165 ± 19.1 cm2) were significantly higher in catfish systems than in tilapia systems (11.34 ± 1.62 cm, 7.53 ± 2.18 cm, and 88.2 ± 33.5 cm2, respectively; p < 0.001). Although differences in final fresh weight and AGR were not significant, the enhanced leaf morphology under catfish effluents indicates improved nitrogen availability and utilization efficiency in the second cycle (Table 2).

3.3. Nutrient Dynamics in Fish Tanks

Water nutrient analysis revealed significant differences between Nile tilapia and African catfish-based systems. In the first growth cycle, tilapia rearing tanks had higher total phosphorus (14.4 ± 2.06) than African Catfish (6.75 ± 1.0). Regarding total nitrogen, African catfish rearing tanks had significantly higher total nitrogen (TN) compared to the tilapia rearing tanks. In both systems, silicon dioxide (SiO2) concentrations did not differ significantly (p > 0.05). However, during Growth Trial 2, the concentrations of TN and SiO2 were significantly higher in the African catfish-based rearing tanks compared to the Nile tilapia-based systems (Table 3).

Table 3.

Nutrient composition in fish rearing tanks and deep-water culture solution during the two growth cycles. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, obtained from triplicate DWC beds and rearing tanks in the African catfish—based aquaponic system and the Nile tilapia—based aquaponic system. Significant differences between tilapia-based aquaponic system and African catfish—based aquaponic system (p < 0.05) are indicated by an asterisk.

3.4. Nutrient Dynamics in Deep-Water Culture Solution

In Growth Trial 1, there were significant differences in the concentrations of TN, total phosphorus (TP), phosphate (PO4), nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N), and chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) between the African catfish-based aquaponic system and the Nile tilapia-based aquaponic system (Table 3). At the end of 30 days, TP in the Nile tilapia-based aquaponics averaged 12.39 ± 0.64 mg/L compared to 6.50 ± 0.29 mg/L in the African catfish-based system (Table 3), while phosphate averaged 8.60 ± 1.48 mg/L in the Nile tilapia-based aquaponic system compared to 2.45 ± 0.06 mg/L in the African catfish-based aquaponic system.

In Growth Trial 2, the African catfish system showed a marked increase in total nitrogen (21.54 ± 2.93 mg/L) compared to tilapia (5.15 ± 0.76 mg/L; p = 0.0007), while tilapia maintained higher TP (10.74 ± 1.05 mg/L; p = 0.04). This shift indicates greater nitrogen mineralization and nitrification activity in catfish systems over time. These results show that while tilapia initially enhanced phosphorus-driven growth, catfish systems progressively enriched nitrogen, supporting morphological development during later growth stages.

3.5. Mineral Concentrations in Fish Rearing Tanks and Deep-Water Culture Solution

There were no significant differences in the concentrations of copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and potassium (K) in water samples collected from the tanks of the African catfish and Nile tilapia systems (Table 4). At the end of the study, water samples from the tanks of the African catfish had higher concentrations of magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca) and sodium (Na) than the Nile tilapia systems. Regarding the deep-water culture solution, tilapia-based systems contained higher Fe concentrations in the DWC beds (0.48 ± 0.03 mg/L), while catfish systems exhibited higher Ca (3.34 ± 0.17 mg/L), Mg (3.19 ± 1.09 mg/L), and Na (4.48 ± 0.13 mg/L) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mineral composition from the fish rearing tanks and DWC systems. Each value is the mean ± SD from triplicate fish tanks and DWC beds. * indicates means were significantly different at p < 0.05.

3.6. Physico-Chemical Parameters in Fish Tanks and Deep-Water Culture Systems

The physico-chemical parameters in both aquaponic systems remained within optimal ranges recommended for fish and lettuce co-culture under tropical conditions. Mean temperature values in both the fish tanks and DWC units ranged from 25.1 to 25.9 °C, with no significant differences between the tilapia- and catfish-based systems (p > 0.05). This temperature stability supports fish metabolic processes and promotes efficient nitrification, both of which are critical for consistent nutrient conversion. Water pH fluctuated slightly between 6.2 and 6.6 across systems, with no significant variation between treatments, indicating effective biofiltration and microbial regulation. This pH range is suitable for nutrient solubility and optimal root nutrient uptake by lettuce. Similarly, total dissolved solids (TDS) and electrical conductivity (EC) levels were not influenced by fish species (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of water quality in the fish rearing tanks and deep-water culture systems. Each value is the mean ± SD from triplicate fish tanks and DWC beds. * indicates means were significantly different at p < 0.05. Mean values are followed by the range in parentheses.

Dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations were maintained above 4 mg/L in both the fish tanks and DWC units, ensuring adequate aeration for fish, plant roots, and nitrifying bacteria. However, DO levels were significantly higher in the catfish system’s DWC units (6.74 ± 0.10 mg/L) compared to the tilapia system (6.08 ± 0.09 mg/L; p = 0.001). This difference may reflect enhanced nitrification and aeration efficiency in the catfish system, potentially linked to the species’ higher oxygen tolerance and greater water movement driven by their activity. Overall, the stability of all measured parameters indicates effective system performance and strong bio-integration between fish and plants, providing favourable conditions for microbial nitrifiers while minimizing physiological stress on both aquatic and plant components.

4. Discussion

4.1. Fish Performance

The findings of this study demonstrate that the choice of fish species in aquaponic systems significantly affects nutrient dynamics, water quality, and the overall growth performance of lettuce under tropical conditions. Differences in fish metabolism, feeding behaviour, and waste excretion patterns created distinct nutrient profiles in the recirculating systems, which in turn influenced plant growth responses across production cycles. Nile tilapia exhibited superior feed conversion efficiency (FCR = 1.47 ± 0.02) compared to African catfish (FCR = 1.64 ± 0.06), confirming its well-documented adaptability and efficient feed utilization in aquaponic systems [15]. The higher phosphorus and ammonium concentrations in tilapia effluents likely resulted from their omnivorous feeding behaviour and efficient mineral excretion, which provided readily available nutrients for lettuce uptake during early growth stages. Tilapia exhibited a lower and more variable survival rate (86.6 ± 10.06%) compared to catfish (95.8 ± 1.89%), which may be due to species-specific differences in tolerance to environmental conditions. Tilapia juveniles are generally more sensitive to fluctuations in water quality parameters such as dissolved oxygen, temperature, and ammonia, which can increase stress and mortality. In contrast, African catfish possess physiological adaptations such as facultative air breathing and broader tolerance to low dissolved oxygen and sub-optimal water conditions, which generally confer greater resilience under variable rearing environments and likely contribute to their consistently higher survival rates [23,24].

4.2. Lettuce Growth

During the first lettuce production cycle, plants cultivated in tilapia-based systems attained significantly greater final fresh weight, biomass gain, and leaf number than those grown in catfish systems. The higher shoot weight observed in the tilapia-based treatment may be attributed to elevated phosphorus levels. Increased availability of phosphorus and ammonium in tilapia systems likely promoted early vegetative growth by enhancing chlorophyll synthesis, root elongation, and photosynthetic activity [25]. Similarly, Cerozi et al. [26] reported improved lettuce growth in aquaponics due to increased phosphorus accumulation. Furthermore, Jones et al. [10] and Estrada-Perez et al. [27] reported enhanced lettuce, cucumber and basil growth when irrigated with nutrient-rich effluents derived from tilapia aquaculture. It can be hypothesized that juvenile tilapia exhibited higher metabolic and feeding activity than African catfish, which resulted in greater fecal output and, consequently, increased nutrient release into the water compared with African catfish. However, in the second crop cycle, catfish systems outperformed tilapia systems in leaf morphology, including significantly higher leaf length, width, and area. This shift corresponded with elevated total nitrogen concentrations in the catfish systems during the second cycle, likely driven by enhanced nitrification as the aquaponic system matured. As system performance improves over time, the establishment and stabilization of nitrifying microbial communities can increase nutrients in the water column [19]. Similar trends have been reported in established aquaponic systems, where nitrogen transformations become more efficient with successive production cycles [5]. Sebastião et al. [14] also reported enhanced lettuce morphology and canopy development in catfish-based systems, which was associated with increased nitrate accumulation. The reduced leaf area of lettuce observed during growth trial 2 in the tilapia-based aquaponic system may be attributed to a combination of nutritional factors. As plant biomass and nutrient demand increased during the second trial, the supply of calcium, an essential element for leaf expansion and photosynthetic development, was relatively lower in the deep-water culture units of the tilapia-based system compared with the catfish-based system. This reduced calcium availability may have contributed to the observed reduction in lettuce leaf area during growth trial 2 in the tilapia-based aquaponic system.

4.3. Nutrient and Mineral Concentrations

In aquaponics, concentrations of plant-available nutrients in solution are driven by many factors, including fish species, growth stage, stocking density, feeding rate, feed composition, and rates of microbial nitrification [4]. The optimal nutrient levels for leafy and fruity vegetables in aquaponics systems are not yet well established. Our study observed elevated total nitrogen levels in catfish-based systems during the second growth trial, likely due to enhanced nitrification activity. This is supported by the significantly higher dissolved oxygen (DO) levels measured in both the fish tanks and DWC beds of catfish systems (6.74 ± 0.10 mg/L) compared to tilapia systems (6.08 ± 0.09 mg/L). Adequate oxygen availability is crucial for microbial nitrification, facilitating the oxidation of ammonium to nitrate [28], which in turn supports sustained plant growth and improved leaf morphology [17]. These findings suggest that fish species can indirectly influence microbial processes and nutrient transformations, thereby affecting plant productivity. In contrast, phosphate concentrations in the DWC units of catfish-based systems were slightly lower than those observed in tilapia-based systems. However, phosphate levels in the catfish systems remained just above the 1.9–2.8 mg/L range reported by Asher [29] as adequate for plant growth in culture solutions, indicating that nutrient availability was sufficient to support lettuce development.

In aquaponic systems, calcium (Ca), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and iron (Fe) are commonly identified as the most limiting essential nutrients for plant growth in the culture solution [8,30]. In the present study, rearing tanks within catfish-based systems contained significantly higher concentrations of Ca, Mg, and Na compared with those of tilapia-based systems. This difference likely reflects species-specific variations in feed utilization, metabolic excretion, and ion regulation, which in turn influence the ionic composition of the recirculating water and subsequent nutrient availability to plants [8]. Calcium and magnesium play critical roles in aquaponic plant growth, with calcium requiring continuous availability due to its low mobility in plants, and magnesium being essential for chlorophyll formation and photosynthesis [31,32]. Sodium, while non-essential and potentially toxic at high concentrations, can be beneficial at low levels by supporting osmotic regulation and partially substituting for potassium, particularly in leafy vegetables [17,32]. Overall, the comparative results indicate that Nile tilapia-based aquaponic systems are better suited for fast-growing crops (≤30 days) requiring rapid nutrient uptake and early yield, while African catfish systems are advantageous for crops requiring prolonged growth periods or morphology-driven quality. The findings also suggest that alternating or integrating both fish species could optimize nutrient balance, enhance microbial diversity, and improve the long-term sustainability of aquaponic systems. These results collectively reinforce the potential of aquaponics as a climate-smart agricultural technology for tropical regions. The balanced nutrient dynamics, stable water quality, and minimal mineral accumulation observed in this study demonstrate the feasibility of scaling up such systems for commercial vegetable and fish production. Future research should therefore focus on the microbial ecology of mixed-species systems, long-term nutrient turnover, and cost–benefit analysis to develop optimized aquaponic models suited to the needs of small- and medium-scale tropical producers.

This study provides clear evidence that fish species selection plays a critical role in shaping nutrient dynamics, water quality, and crop performance in tropical aquaponic systems. Under identical recirculating conditions, Oreochromis niloticus and Clarias gariepinus produced distinct water nutrient profiles that directly influenced the growth, physiology, and morphology of lettuce (Lactuca sativa). Nile tilapia-based systems exhibited higher phosphorus and ammonium concentrations, which promoted vigorous early vegetative growth, greater leaf number, and higher total biomass during the first production cycle. In contrast, African catfish-based systems progressively accumulated total nitrogen and nitrate, resulting in enhanced leaf morphology, wider leaves with larger surface areas during the second cycle. These findings confirm that tilapia systems favour phosphorus-driven, early-cycle growth, whereas catfish systems provide sustained nitrogen enrichment that supports long-term plant development.

4.4. Physico-Chemical Parameters

In both the African catfish and Nile tilapia rearing tanks, temperature (25.10–25.92 °C), pH (5.96–6.35), and dissolved oxygen (4.40–5.82 mg/L) remained within optimal ranges recommended for tropical aquaponic systems [30]. These stable water quality conditions demonstrate that both fish species can be effectively integrated with plant production under controlled environments. Ammonium–nitrogen (NH4+–N) concentrations were consistently below 1 mg/L throughout the study, a level considered non-toxic and therefore not detrimental to the health or growth performance of either species [33,34]. EC and TDS values increased over time in both systems, reflecting the release of ions from fish feed as well as the mineralization of accumulated organic matter [5]. Despite this increase, both EC and TDS remained within optimal ranges for fish culture, as Reyes Yanes [34] reported that EC values of 0.1–2.0 mS/cm and TDS levels below 1000 mg/L are desirable for aquaponic systems.

Furthermore, dissolved oxygen levels remained above the minimum threshold of 4 mg/L required for efficient aquaponics operation, as recommended by Sallenave [35], ensuring adequate aeration to support fish metabolism and nitrification processes. Both EC and TDS were within the optimum range for culturing fish. In the deep-water culture units, the catfish-based aquaponic systems recorded slightly higher dissolved oxygen levels, which supported more efficient nitrification and enhanced nitrogen turnover. The water pH ranged between 6.43 and 6.55, an optimal range for nutrient availability and plant growth in aquaponic systems [35]. The electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids recorded in both systems were within recommended limits for lettuce production, confirming balanced nutrient mineralization and salt accumulation [36]. The higher DO and total nitrogen in catfish systems, combined with steady pH and temperature, indicate robust biological filtration and reduced stress on aquatic organisms.

5. Conclusions

The results demonstrate that integrating fish and hydroponics through species-specific management can enhance nutrient recycling and resource-use efficiency. Both Nile tilapia and African catfish exhibited considerable potential for integration into sustainable aquaponic systems under tropical greenhouse conditions. Tilapia-based systems are well-suited for short-cycle leafy vegetables that require rapid biomass accumulation and early harvest. In contrast, African catfish systems are more appropriate for plants requiring longer growth periods, promoting enhanced morphological quality and greater nitrogen-use efficiency. This complementary relationship between the two fish species suggests that a combined or alternating aquaponic approach could optimize nutrient availability across multiple cropping cycles, minimize external fertilizer input, and improve the overall resilience. This is further supported by Yep and Zheng [8], who suggested that the use of multiple species may be advantageous for developing a more balanced and comprehensive nutrient profile in aquaponic systems.

These results provide a foundation for designing climate-smart aquaponic models for tropical regions. The integration of fish species with contrasting nutrient excretion profiles offers an opportunity to create balanced systems that support consistent crop performance and water quality over time. To fully harness these benefits, future research should investigate the microbial communities responsible for nutrient transformations, evaluate long-term nutrient cycling in multi-cycle production, and assess the economic feasibility of dual-species aquaponic systems. Additionally, integrating renewable energy and automation technologies into these systems could enhance water- and nutrient-use efficiency, reduce operational costs, and increase scalability for commercial and community-level adoption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A., N.K., B.K. and I.R.; methodology, C.A., N.K., E.A. and I.R.; data curation, N.K., G.A. and P.D.T.; writing of original draft, N.K., B.K. and I.R.; reviewing and editing, C.A., G.A., P.D.T., M.A., G.B., E.A. and G.D.; project administration, C.A., N.K., P.D.T. and B.K.; funding acquisition, C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the European Commission under the project titled ‘Potentials of Agroecological Practices in East Africa with a focus on Circular Water-Energy-Nutrient Systems’ (PrAEctiCe), under project call ref: HORIZON-CL6-2022-FARM2FORK-01-12 and Grant No. 101084248.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the National Fisheries Resources Research Institute (NaFIRRI)—Aquaculture Research and Development Centre, Kajjansi, Uganda, for providing experimental facilities, greenhouse space, and technical support during this study. The authors also thank the National Crop Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI) and the Buginyanya Zonal Agricultural Research and Development Institute (BugiZARDI) for their collaboration in crop management, nutrient analysis, and system monitoring. Special appreciation is extended to the technical staff and research assistants at NaFIRRI for their contributions to fish husbandry, biofilter operation, and water quality monitoring. The authors further acknowledge the guidance and logistical support provided by the National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO), Uganda, for facilitating institutional collaboration and coordination of this research activity.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture-Trends and Challenges; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, L.A.; Shaghaleh, H.; El-Kassar, G.M.; Abu-Hashim, M.; Elsadek, E.A.; Alhaj Hamoud, Y. Aquaponics: A sustainable path to food sovereignty and enhanced water use efficiency. Water 2023, 15, 4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennard, W.; Goddek, S. Aquaponics: The basics. In Aquaponics Food Production Systems; Goddek, S., Joyce, A., Kotzen, B., Burnell, G.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Rakocy, J.E.; Masser, M.P.; Losordo, T.M. Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems: Aquaponics—Integrating Fish and Plant Culture; Southern Regional Aquaculture Center: Stoneville, MS, USA, 2006; pp. 1–16.

- Kasozi, N.; Kaiser, H.; Wilhelmi, B. Effect of Bacillus spp. on lettuce growth and root associated bacterial community in a small-scale aquaponics system. Agronomy 2021, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Chandrakant, M.H.; John, V.C.; Peter, R.M.; John, I.E. Aquaponics as an integrated agri-aquaculture system (IAAS): Emerging trends and future prospects. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 194, 122709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Lu, C.; Pan, S.; Yang, J.; Miao, R.; Ren, W.; Yu, Q.; Fu, B.; Jin, F.-F.; Lu, Y. Optimizing resource use efficiencies in the food–energy–water nexus for sustainable agriculture: From conceptual model to decision support system. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 33, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yep, B.; Zheng, Y. Aquaponic trends and challenges—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 1586–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaus, U.; Palm, H. Effects of the fish species choice on vegetables in aquaponics under spring-summer conditions in northern Germany (Mecklenburg Western Pomerania). Aquaculture 2017, 473, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.J.; Shaw, C.; Chen, T.W.; Staß, C.M.; Ulrichs, C.; Riewe, D.; Kloas, W.; Geilfus, C.M. Plant nutritional value of aquaculture water produced by feeding Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) alternative protein diets: A lettuce and basil case study. Plants People Planet. 2024, 6, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauch, S.M.; Wenzel, L.C.; Bischoff, A.; Dellwig, O.; Klein, J.; Schüch, A.; Wasenitz, B.; Palm, H.W. Commercial African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) Recirculating aquaculture systems: Assessment of element and energy pathways with special focus on the phosphorus cycle. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, C.; Cohen, M.; Pantanella, E.; Stankus, A.; Lovatelli, A. Small-scale aquaponic food production. In Integrated Fish and Plant Farming; Technical Paper No. 589; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture: Rome, Italy, 2014; pp. 130–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lopchan Lama, S.; Marcelino, K.R.; Wongkiew, S.; Surendra, K.C.; Hu, Z.; Lee, J.W.; Khanal, S.K. Recent advances in aquaponic systems: A critical review. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastião, F.; Vaz, D.C.; Pires, C.L.; Cruz, P.F.; Moreno, M.J.; Brito, R.M.M.; Cotrim, L.; Oliveira, N.; Costa, A.; Fonseca, A.; et al. Nutrient-efficient catfish-based aquaponics for producing lamb’s lettuce at two light intensities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 6541–6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Yang, T.; Kim, H.-J. pH dynamics in aquaponic systems: Implications for plant and fish crop productivity and yield. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Kim, H.-J. Characterizing nutrient composition and concentration in tomato-, basil-, and lettuce-based aquaponic and hydroponic systems. Water 2020, 12, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanacore, L.; El-Nakhel, C.; Modarelli, G.C.; Rouphael, Y.; Pannico, A.; Langellotti, A.L.; Masi, P.; Cirillo, C.; De Pascale, S. Growth, ecophysiological responses, and leaf mineral composition of lettuce and curly endive in hydroponic and aquaponic systems. Plants 2024, 13, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmautz, Z.; Graber, A.; Jaenicke, S.; Goesmann, A.; Junge, R.; Smits, T.H.M. Microbial diversity in different compartments of an quaponics system. Arch. Microbiol. 2017, 199, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennard, W.A.; Leonard, B.V. A comparison of three different hydroponic sub-systems (gravel bed, floating and nutrient film technique) in an aquaponic test system. Aquac. Int. 2006, 14, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, N.; Wilhelmi, B.; Kaiser, H. The effect of the addition of a probiotic mixture of two Bacillus species to a coupled aquaponics system on water quality, growth and digestive enzyme activity of Mozambique tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus. J. Appl. Aquac. 2021, 35, 510–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, N.; Kaiser, H.; Wilhelmi, B. Determination of phylloplane associated bacteria of lettuce from a small-scale aquaponic system via 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequence analysis. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association and Water Pollution Control Federation. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Palm, H.W.; Knaus, U.; Wasenitz, B.; Bischoff, A.A.; Strauch, S.M. Proportional up scaling of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus Burchell, 1822) commercial recirculating aquaculture systems disproportionally affects nutrient dynamics. Aquaculture 2018, 491, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baßmann, B.; Brenner, M.; Palm, H.W. Stress and welfare of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus Burchell, 1822) in a coupled aquaponic system. Water 2017, 9, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuswantoro, S.; Sung, T.-Y.; Kurniawan, M.; Wu, T.-M.; Chen, B.; Hong, M.-C. Effects of phosphate-enriched nutrient in the polyculture of Nile tilapia and freshwater prawn in an aquaponic system. Fishes 2023, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerozi, B.D.S.; Fitzsimmons, K. Use of Bacillus spp. to enhance phosphorus availability and serve as a plant growth promoter in aquaponics systems. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 211, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Pérez, N.; Zavala-Leal, I.; González-Hermoso, J.; Ruiz-Velazco, J. Comparing lettuce and cucumber production using hydroponics and aquaponic (tilapia) systems. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2024, 52, 59–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasozi, N.; Abraham, B.; Kaiser, H.; Wilhelmi, B. The complex microbiome in aquaponics: Significance of the bacterial ecosystem. Ann. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, C.J.; Loneragan, J.F. Response of plants to phosphate concentration in solution culture: I. Growth and phosphorus content. Soil Sci. 1967, 103, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddek, S.; Delaide, B.; Mankasingh, U.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; Jijakli, H.; Thorarinsdottir, R. Challenges of Sustainable and Commercial Aquaponics. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4199–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, R.V.; Treadwell, D.D.; Simonne, E.H. Opportunities and challenges to sustainability in aquaponic systems. HortTechnology 2011, 21, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maucieri, C.; Nicoletto, C.; Van Os, E.; Anseeuw, D.; van Havermaet, R.; Junge, R. Hydroponic technologies. In Aquaponics Food Production; Systems; Goddek, S., Joyce, A., Kotzen, B., Burnell, G.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, H.Y.; Robaina, L.; Pirhonen, J.; Mente, E.; Dominguez, D.; Parisi, G. Fish welfare in aquaponic systems: Its relation to water quality with an emphasis on feed and faeces: A review. Water 2017, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Yanes, A.; Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R. Towards automated aquaponics: A review on monitoring, IoT, and smart systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallenave, R. Important Water Quality Parameters in Aquaponics Systems; New Mexico State University: Las Cruces, NM, USA, 2016; Volume 80, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, B.; Olorunwa, O.J.; Wilson, J.C.; Barickman, T.C. Seasonal dynamics of lettuce growth on different electrical conductivity under a nutrient film technique hydroponic system. Technol. Hortic. 2024, 4, e01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.