Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are covalently closed RNA molecules that regulate various biological processes in plants. However, the functions of most identified circRNAs remain unclear. Here, we report a nucleoplasmic-localized circRNA, Vv-circRCD1, derived from exons 2 and 3 of the grape VvRCD1 gene. Overexpression of Vv-circRCD1 significantly shortened primary root length and increased root hair number and length, notably, and improved the salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Transient overexpression also significantly enhanced salt tolerance of grapevines. In silico analyses confirmed direct sequence complementarity between Vv-circRCD1 and the Vvi-miR399 family, and Vv-circRCD1 and Vvi-miR399 target genes (involved in salt stress responses) showed consistent expression patterns under salt stress, indicating a Vv-circRCD1–Vvi-miR399–target gene regulatory module may mediate salt tolerance. These results not only identified Vv-circRCD1 as a novel regulator of grapevine salt tolerance, but also highlighted its potential in improving crop stress resistance, providing a practical reference for crop breeding.

1. Introduction

Circular RNAs are a class of endogenous covalently closed non-coding RNAs that regulate eukaryotic gene expression through miRNA sponges [1], and play a key role in plant abiotic stress response and root development [2]. Transcriptome sequencing has identified thousands of grapevine circRNAs [3,4,5,6], including root-rich members, but more than 8000 computationally predicted grapevine circRNAs remain functionally uncharacterized [7,8,9,10]. Only a small portion was verified: Notably, ectopic overexpression of Vv-circATS1 and Vv-circPAS1 enhances the cold and salt tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana and grapevine [11,12,13]. Although numerous circRNAs have been identified in grapevine, and a handful have been linked to salt tolerance, the functional roles and underlying regulatory mechanisms of circRNAs derived from stress-responsive genes in grapevine salt stress adaptation remain largely unknown [14].

Radical-Induced Cell Death 1 gene (RCD1) encodes a member of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) family and is highly conserved in both plants and animals. Functional analyses of RCD1 homologs have established their critical functions in coordinating stress responses with developmental programs. RCD1 serves as a central node integrating multiple stress signaling pathways, hormone responses, and developmental processes [15]. It regulates plant responses to multiple abiotic stressors, including salinity, heat, high light and UV-B, as well as key phytohormones such as ethylene, abscisic acid and methyl jasmonate [16,17,18]. In Arabidopsis, RCD1 localizes to cytoplasmic foci under salt stress, where it interacts with the plasma membrane-localized Na+/H+ antiporter Salt Overly Sensitive 1 (SOS1) to mediate ionic homeostasis [19], which is a mechanism that explains the enhanced salt tolerance of RCD1-overexpressing lines [20]. Conversely, loss-of-function mutants of RCD1 exhibit pleiotropic defects, including altered plasmodesmata architecture [21], accelerated senescence, and stunted plants [22]. Notably, RCD1 modulates reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis through inhibition of the expression of ANAC017, thereby preventing oxidative damage during salt stress [23]. Given the critical role of RCD1 in plant stress adaptation, it is reasonable to hypothesize that circRNAs derived from RCD1 may participate in the same regulatory networks.

The regulatory networks governing plant stress responses frequently involve microRNAs (miRNAs), which serve as post-transcriptional modulators [24]. These endogenous 20–24 nucleotide RNAs are processed from stem-loop precursors by DICER-LIKE1 (DCL1) and typically mediate the cleavage or translational inhibition of their target mRNAs [25]. Among plant miRNAs, the miR399 family has been associated with abiotic stress responses and plays a key role in salt stress adaptation. Specifically, soybean plants overexpressing miR399a showed increased sensitivity to salt stress under 75 mM NaCl treatment, with a reduction of approximately 40% in primary root length [26]. Under drought stress, the expression levels of miR399 family members in Arabidopsis exhibited varying degrees of change [27], further supporting their involvement in salt stress-related signaling. These findings indicate that miR399 is a key regulator of plant stress responses, raising the possibility that its function may be modulated by circRNAs through the miRNA sponging mechanism.

CircRNAs modulate diverse biological processes through a variety of mechanisms, including miRNA and protein sponging, modulation of transcriptional activity, involvement in alternative splicing, and translation into functional peptides [28,29]. Os-circANK inhibits rice resistance to bacterial blight via the miR398b/CSD/SOD pathway [10]. circZmMED16 interacts with small subunit 1 of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (APS1) mRNA in both maize and Arabidopsis. Additionally, ciMIR156Ds form R-loops with MIR156D at the region where they derive in an aging-dependent manner, which reduces the occupancy of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II at that location and hence impedes pri-miR156d elongation [6]. These examples illustrate the versatility of circRNA-mediated gene regulation in plants, providing a theoretical basis for investigating whether grapevine RCD1-derived circRNA can interact with miR399 to modulate stress tolerance.

Based on previous studies, miR399 is a conserved miRNA [5], and its interaction with circRNAs derived from functional genes has not been fully elucidated in grapevines. In a previous transcriptome-wide analysis, we systematically identified and characterized the circRNA repertoire expressed in grapevine root tissues [30], and Vv-circRCD1 belongs to one of these candidate genes. In this study, we reported the cloning and molecular identification of Vv-circRCD1 and analyzed its expression pattern under salt stress. Through functional characterization of Vv-circRCD1 in transgenic grapevine and Arabidopsis lines, combined with verification of its specific interaction with Vvi-miR399. This work addresses the critical knowledge gap regarding the functional roles of grapevine circRNAs and their interactions with miR399 in mediating salt stress responses. We elucidate the precise regulatory mechanism of Vv-circRCD1 in grapevine salt tolerance centered on the Vv-circRCD1–Vvi-miR399 module, providing novel insights into circRNA-mediated stress adaptation in plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from 1-year-old Vitis vinifera cv. Thompson Seedless grapevines using a modified CTAB method [31]. For Arabidopsis thaliana, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol™ Reagent (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the FastKing RT Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) with random primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.2. Validation of Vv-circRCD1 in Grapevine

To confirm the back-splicing site of Vv-circRCD1, divergent primers and convergent primers were designed based on the grapevine genome annotation using Primer Premier 5.0. RT-PCR was performed using grapevine root cDNA and genomic DNA (gDNA) as templates. PCR reactions (25 μL) contained 1× PCR buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM each primer, and 1.25 U Taq DNA polymerase (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were resolved by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized under UV light. Target bands corresponding to Vv-circRCD1 were excised from the gel, purified using the Gel Extraction Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), and subsequently validated by Sanger sequencing to confirm the presence of back-splicing junctions [13]. Subcellular localization and tissue-specific expression patterns of Vv-circRCD1 were analyzed as previously described [13]. All primers used in the above experiments are listed in Table S1. The nucleus is referenced to VvU6, and the cytoplasm is referenced to VvActin.

2.3. Vector Construction and Agrobacterium Tumefaciens-Mediated Expression Assays in Nicotiana Benthamiana

The circRNA expression vector was constructed following a previously established strategy [14]. The Vv-circRCD1 sequence and its corresponding linear control fragment were cloned into the pHB binary vector under the control of the 2 × 35S promoter using BamH I and Xba I (New England Biolabs inc, Ipswich, MA, USA) restriction sites. All constructed vectors were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 (WeiDi, Shanghai, China) and cultured on Luria–Bertani (LB) liquid medium supplemented with 25 mg/L rifampicin and 50 mg/L kanamycin at 28 °C for 2–3 days. A single positive colony was selected and grown in liquid LB medium with the same antibiotics at 200 rpm and 28 °C for 8–10 h. Plasmid presence was confirmed by PCR. Positive clones were mixed with an equal volume of 50% glycerol and stored at −80 °C.

For transient expression in tobacco leaves, 10 μL of positive clone bacterial solution was added to 15 mL of LB liquid medium containing 50 mg/L rifampicin and 50 mg/L kanamycin. The mixture was then placed in a 50 mL sterile centrifuge tube and incubated in a shaker at 28 °C and 200 rpm until the OD600 reached 1.0. Subsequently, the sample was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 8 min to collect the Agrobacterium cells. The supernatant was removed, and MAA buffer (comprising 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, and 100 μM acetosyringone, pH 5.8) was added. The resuspended mixture was then incubated in a shaker at 28 °C and 200 rpm for 1 h. Finally, a syringe was used to inject the cultured bacterial solution into the leaves of N. benthamiana. Three days after injection, the tobacco leaves were collected, and RNA was extracted. All primers used are listed in Tables S2–S4.

2.4. Arabidopsis Transformation and Verification

Arabidopsis transformation was carried out using the floral dip method [32]. Transgenic plants (Vv-circRCD1 OE-2, -5, -7 and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE-1, -2, -3) were selected on medium containing 10 mg/L glufosinate ammonium (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). Putative transformants were further verified through circRNA-specific PCR and RT-qPCR using cDNA as a template. Amplification products were sequenced to confirm the correct back-splicing junction. The primers used are provided in Table S5.

2.5. Root Phenotype Analysis and Salt Stress Assays in A. thaliana

Seeds of wild-type (WT) and transgenic A. thaliana were surface-sterilized with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min and rinsed five times with sterile water. The sterilized seeds were sown on 1/2 MS medium and stratified at 4 °C for 2 days. Plates were then placed vertically in a growth chamber set to 22 °C with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod for 5 days to assess root architecture and root hair phenotypes. For each independent experiment, 5 seedlings per line were tested. Primary root length was measured using ImageJ software (v1.54c) [33] based on scanned images of the seedlings. Root hair density was quantified by counting the number of root hairs under a stereomicroscope. Three biological replicates were performed for each sample. For salt stress treatment, 5-day-old WT and transgenic seedlings were transferred to fresh 1/2 MS medium and grown for an additional 7 days. Plants were then treated with a 200 mM NaCl solution, while controls received water. Phenotypic observations were recorded after 14 days of treatment. Three biological replicates were performed for each sample.

2.6. Transient Expression of Vv-circRCD1 in Grapevine and Salt Stress Treatment

Tissue-cultured seedlings of Thompson Seedless were subjected to Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation under vacuum infiltration. Seedlings were immersed in infection solution and vacuum-infiltrated at −0.1 MPa for 5 min. After infiltration, plants were co-cultured on medium for 2 days. In salt stress treatment, the transient transformation of grape tissue-cultured seedlings (Vv-circRCD1 OE-2, -5, -7 and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE-1, -2, -3) and detached leaves were treated with 200 mM NaCl solution, respectively, while the control group was treated with water. Based on the preliminary experiments, the concentration of 200 mM NaCl salt stress treatment was determined. This dose can induce typical salt stress symptoms in grapevines, ensuring a reliable phenotype of salt tolerance traits. Phenotypic responses and chlorophyll content [34] were subsequently evaluated and recorded after 7 days of treatment. Three biological replicates were performed for each sample.

2.7. Interaction Network Prediction

The targeting relationships between grapevine Vv-circRCD1 and miRNAs, as well as between miRNAs and their potential mRNA targets, were predicted using the psRNATarget platform (2017 release) [35]. Candidate target miRNAs were further filtered against the grapevine database (Vitis vinifera L., Phytozome 13, 457_v2.1) to ensure species specificity. The maximum expectation value was set to 3.0 to ensure high-confidence predictions.

2.8. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Analysis

Gene expression analysis was performed using Talent qPCR PreMix (TIANGEN, China) on a qTOWER3 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Analytikjena, Jena, Germany). The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [36]. Convergent primers (▷◁) and divergent primers (◀▶) were designed to amplify the linear transcript and Vv-circRCD1, respectively, using grapevine root cDNA and gDNA as templates. Each assay included three biological replicates to ensure statistical reliability. All primers used in this study are listed in Table S6. The VvActin gene served as a reference gene. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0. Differences between treatment and control groups were assessed via Student’s t-test, with statistical significance defined as p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.01 (**).

3. Results

3.1. Expression of Vv-circRCD1 and Analysis of Splicing Sites

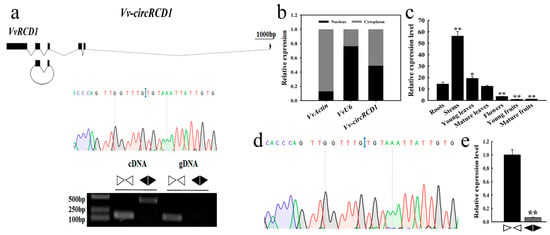

The circular RNA derived from the grapevine VvRCD1 gene was designated as Vv-circRCD1 (Figure 1a). This circRNA arises from back-splicing of exons 2 and 3 of VvRCD1. PCR assay indicated that Vv-circRCD1 was amplified from cDNA but not from gDNA. Sanger sequencing confirmed the back-splice junction site (UG/UG) of Vv-circRCD1 (Figure 1a). Subcellular localization analysis showed that the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic distribution ratio of Vv-circRCD1 was 0.49:0.51, with a slight enrichment in the cytoplasm (Figure 1b). RT-qPCR analysis of Vv-circRCD1 expression across seven grapevine tissues (roots, stems, young leaves, mature leaves, flowers, young fruits, and mature fruits) revealed tissue-specific accumulation, with the highest expression level detected in stems (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing analysis of Vv-circRCD1. (a) The upper diagram represents the gene structure of the Vv-circRCD1 and its parental gene. The black blocks and black lines denote exons and introns, respectively. In the middle, each back-splicing site was displayed by Sanger sequencing. The blue line indicates joint sequences; The lower diagram shows the RT-qPCR analysis of Vv-circRCD1 and linear fragment (linear RNA) after RNase R treatment. Convergent primers (▷◁) and divergent primers (◀▶) were designed to amplify each circRNA from the cDNA and the genomic DNA of the grapevine roots, with and without RNase R treatment. (b) Vv-circRCD1 expression in the nucleus and cytoplasm. The VvActin gene served as a reference gene. (c) Tissue-specific expression analysis of Vv-circRCD1. (d) Sanger sequencing of Vv-circRCD1 in N. benthamiana. The blue line indicated joint sequences. (e) RT-qPCR was performed to examine Vv-circRCD1 and linear RNA expression in N. benthamiana. Data are average standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments. * and ** indicated statistically significant difference at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, based on Student’s t-test.

To assess the conservation of circRNA biogenesis across species, Vv-circRCD1 was transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves via A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the UG/UG back-splicing junction in tobacco-expressed Vv-circRCD1 (Figure 1d), confirming its circular structure in a heterologous system. However, its expression level was markedly lower (less than 10%) compared to that of the linear fragment in tobacco (Figure 1e). These results indicate that Vv-circRCD1 is a genuine circRNA with a conserved back-splice junction, showing cytoplasm-preferred localization and tissue-specific expression in grapevines.

3.2. Vv-circRCD1 Regulates Root Architecture in Arabidopsis

Having confirmed the accurate splicing and salt-responsive expression pattern of Vv-circRCD1, we next sought to investigate its biological function in planta. Given that root architecture is a critical trait associated with plant stress adaptation, we first evaluated the regulatory role of Vv-circRCD1 in root development using a heterologous expression system in Arabidopsis thaliana.

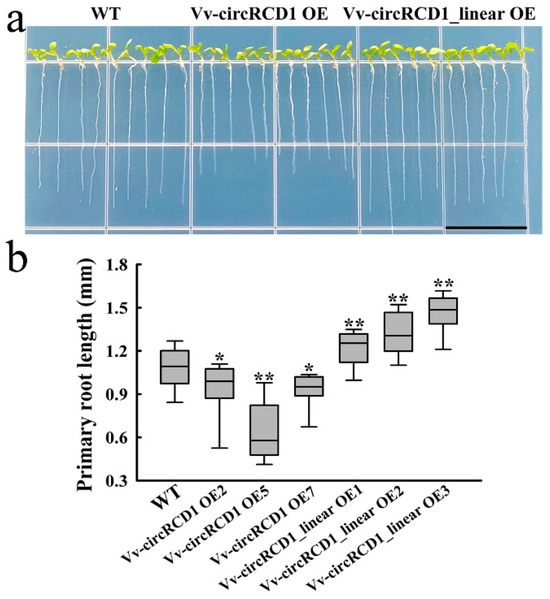

To investigate the potential roles of Vv-circRCD1 in root development, we generated transgenic A. thaliana lines overexpressing either the circular form (Vv-circRCD1 OE) or its overlapping linear fragment (Vv-circRCD1_linear OE), using WT as the control. Root length was significantly reduced in Vv-circRCD1 OE plants compared to both WT and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE (Figure 2a), with the most pronounced effect observed in the Vv-circRCD1 OE-5 (Figure 2b). In contrast, overexpression of the linear fragment derived from Vv-circRCD1 notably promoted root elongation relative to the WT.

Figure 2.

Root phenotype of Arabidopsis with overexpression of Vv-circRCD1 and homologous linear genes. Root phenotype (a) and primary root length statistics (b) of WT and transgenic plants were analyzed. Bar = 1 cm. Error bars indicate mean SD (n = 3). * and ** indicated statistically significant difference at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, based on Student’s t-test.

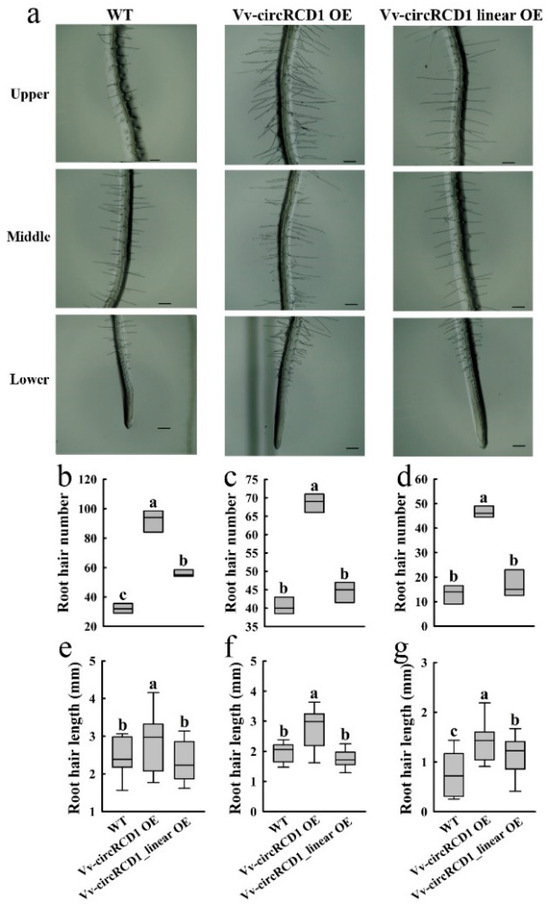

To assess the impact of Vv-circRCD1 on root hair development, we analyzed root hair density and length in three distinct root zones (upper, middle, lower) of 5-day-old Arabidopsis seedlings (WT, Vv-circRCD1 OE, and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE) (Figure 3). Overexpression of Vv-circRCD1 was also found to significantly influence root hair development in Arabidopsis. The number of root hairs in each zone was markedly higher in Vv-circRCD1 OE plants compared to both Vv-circRCD1_linear OE and WT plants (Figure 3b–d). In contrast, overexpression of the linear fragment resulted in a significant increase in root hair number only in the upper zone relative to the WT. Moreover, the length of root hairs in Vv-circRCD1 OE was significantly greater than that in either Vv-circRCD1_linear OE or WT plants across all zones (Figure 3e–g). A significant difference in root hair length was also observed between Vv-circRCD1_linear OE and WT, specifically in the lower zone. In conclusion, these results demonstrate that Vv-circRCD1 overexpression promotes both the quantity and length of Arabidopsis root hairs. These results indicate that Vv-circRCD1 and its linear fragment exert contrasting effects on Arabidopsis root architecture, with the circular form inhibiting primary root elongation and enhancing root hair density and length across all root zones.

Figure 3.

Root hair phenotype of Arabidopsis overexpressing Vv-circRCD1 and homologous linear genes. Root hair phenotype (a), number (b–d) and length (e–g) of WT and transgenic upper, middle and lower sections. Bar = 1 mm. Data are average SD from ten independent Experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05, based on Student’s t-test.

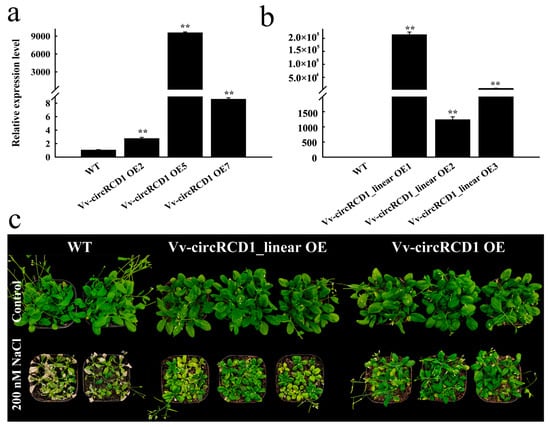

3.3. Overexpression of Vv-circRCD1 Enhanced Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis

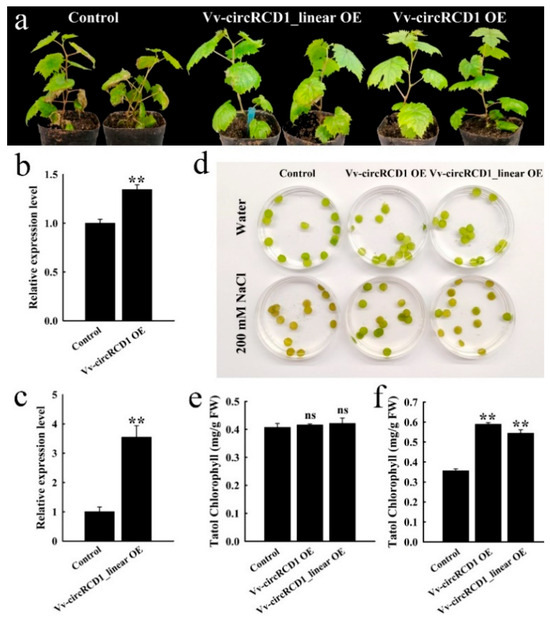

The observed alterations in root architecture implied that Vv-circRCD1 may participate in plant stress tolerance pathways. To test this hypothesis, we further assessed the performance of Vv-circRCD1 overexpression lines under salt stress conditions in Arabidopsis. To investigate the functional role of Vv-circRCD1 in salt stress response, we generated Arabidopsis plants overexpressing Vv-circRCD1 and evaluated their performance under salt stress. The results showed that transgenic lines exhibited significantly elevated expression levels of both circular Vv-circRCD1 and its homologous linear transcript (Figure 4a,b). Under normal growth conditions, there is no significant differences were observed between WT and transgenic plants. However, upon salt stress treatment, the growth and enhanced salt tolerance of Vv-circRCD1 OE and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE plants were significantly higher than those of WT (Figure 4c). These results indicate that Vv-circRCD1 overexpression confers enhanced salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis, with the Vv-circRCD1 OE exhibiting a greater protective effect than and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE.

Figure 4.

Phenotype of A. thaliana overexpressing Vv-circRCD1 under salt stress. (a) Expression level of Vv-circRCD1 in Vv-circRCD1 OE plant. (b) Expression level of Vv-circRCD1 homologous linear gene in Vv-circRCD1_linear OE. (c) Phenotypes of Vv-circRCD1_ OE and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE under salt stress. Data are average SD from three independent experiments. ** indicated statistically significant difference at p < 0.01, based on Student’s t-test.

3.4. Overexpression of Vv-circRCD1 Enhances Salt Tolerance in Grapevine

The heterologous expression assay in Arabidopsis demonstrated the positive role of Vv-circRCD1 in salt tolerance. To validate the function of this circRNA in its native species, we subsequently conducted homologous overexpression experiments in grapevine and analyzed the salt tolerance of transgenic lines. To validate the function of Vv-circRCD1 in grapevine, we transiently generated transgenic grapevine tissue culture seedlings overexpressing either Vv-circRCD1 OE or its linear fragment (Vv-circRCD1_linear OE), and empty vector was used as control. Vv-circRCD1 was instantaneously expressed in grapevine tissue culture seedlings, and the expression level of Vv-circRCD1 significantly increased (Figure 5b,c). Under salt stress treatment, grapevine plants overexpressing Vv-circRCD1 exhibited stronger salt tolerance compared to both Vv-circRCD1_linear OE and control plants (Figure 5a). Upon salt conditions, leaves from Vv-circRCD1 OE plants showed delayed browning compared to those expressing the linear fragment and control plants (Figure 5d). Meanwhile, the chlorophyll contents were significantly higher in both Vv-circRCD1 OE and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE plants than control. The chlorophyll content of the Vv-circRCD1 OE was 65.3% higher than that of the WT. In contrast, the chlorophyll content of the Vv-circRCD1_linear OE was 52.6% higher than that of the WT and 7.7% lower than that of the Vv-circRCD1 OE (Figure 5e,f). These results demonstrate that overexpression of Vv-circRCD1 can enhance the tolerance of grapevine to salt stress.

Figure 5.

Phenotypes of overexpressed Vv-circRCD1 and homologous linear genes in grapevine under salt stress. (a) The phenotype of Vv-circRCD1 overexpressed in grapevine under salt stress. (b) Expression of Vv-circRCD1 in Vv-circRCD1 OE. (c) Expression of Vv-circRCD1 homologous linear gene in Vv-circRCD1_linear OE. Grapevine leaves overexpressed Vv-circRCD1 OE and Vv-circRCD1_linear OE in salt treatment phenotype (d), chlorophyll content in water treatment (e) and chlorophyll content in salt treatment (f). Data are average SD from three independent Experiments. ns indicated no statistical significance. ** indicated statistically significant difference at p < 0.01, based on Student’s t-test.

3.5. Interaction Network Between Grapevine Vv-circRCD1 and miRNAs

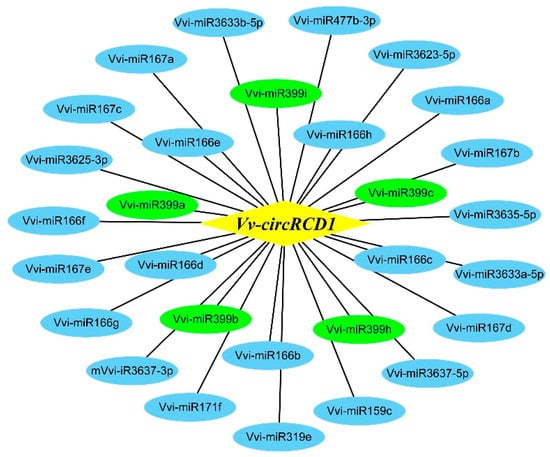

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying Vv-circRCD1-mediated salt tolerance, we next explored its potential regulatory targets. Given that circRNAs often exert functions by sponging miRNAs, we constructed a miRNA interaction network for Vv-circRCD1 in grapevine. A total of 29 miRNAs were identified as potential targets of Vv-circRCD1. Among these, five members of the grapevine miR399 family (Vvi-miR399i, Vvi-miR399a, Vvi-miR399h, Vvi-miR399b and Vvi-miR399c) exhibited particularly stable binding interactions with Vv-circRCD1, suggesting a potential regulatory relationship (Figure 6). These results indicate that Vv-circRCD1 may potentially interact with miRNAs in grapevines.

Figure 6.

Vv-circRCD1-miRNA interaction network diagram. Yellow represents Vv-circRCD1, and blue represents miRNA (among which green represents the members of the Vvi-miR399 family).

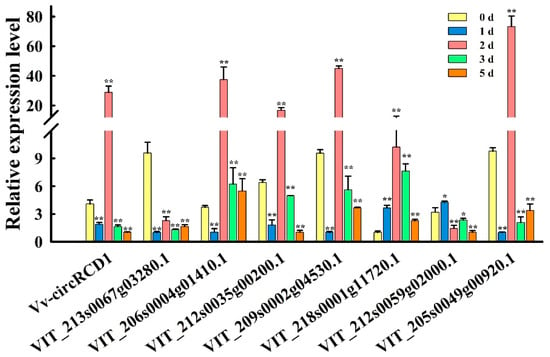

3.6. Expression Analysis of Vv-circRCD1 and miR399 Target Genes Under Salt Stress

Among the identified miRNA interactors, miR399 was previously reported to be involved in plant salt stress responses [37], suggesting a potential Vv-circRCD1-miR399 regulatory module. To confirm this regulatory relationship, we finally analyzed the expression patterns of Vv-circRCD1, miR399 and its downstream target genes under salt stress. According to our previous studies, the Vvi-miR399 family consists of 9 members. We found that seven Vvi-miR399 members simultaneously target the gene VIT_213s0067g03280.1 (Figure S1).

Under salt stress treatment, the expression patterns of Vv-circRCD1 and three additional genes (VIT_212s0035g00200.1, VIT_209s0002g04530.1 and VIT_205s0049g00920.1) exhibited a consistent trend. Initially, their expression levels declined, followed by a sharp increase, and then another abrupt decrease. Notably, on the second day of salt stress treatment, the expression of these four genes accumulated significantly and peaked. In contrast, the expression level of VIT_213s0067g03280.1 remained consistently and significantly lower than that of the control group throughout the salt stress treatment period. Conversely, the expression of VIT_218s0001g11720.1 was consistently and significantly higher than that of the control group during the entire salt stress treatment. Furthermore, the expression of VIT_206s0004g01410.1 was significantly higher than that of the control group only during the later stages of salt stress treatment, specifically on days 2, 3, and 5. As for VIT_212s0059g02000.1, its expression was significantly higher than that of the control group only on the first day of salt stress treatment, but it decreased significantly over the subsequent three days (Figure 7 and Figure S2). These results indicate that Vv-circRCD1 and miR399 target genes exhibit distinct expression dynamics under salt stress, which supports the existence of a potential Vv-circRCD1-miR399 regulatory module involved in plant salt stress responses.

Figure 7.

Expression of Vv-circRCD1 and miR399 target genes after exposure to 300 mM NaCl solution for 0, 1, 2, 3, and 5 d. Data are average SD from three independent Experiments. * and ** indicated statistically significant difference at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, based on Student’s t-test.

4. Discussion

4.1. Validation and Characterization of Vv-circRCD1

Sanger sequencing of the PCR product revealed a precise UG/UG back-splicing junction, consistent with the splicing signal present in the linear VvRCD1 transcript (Figure 1a). Moreover, transient expression in N. benthamiana also yielded the expected back-spliced product (Figure 1d), demonstrating that Vv-circRCD1 retains its circular conformation even in a heterologous system, thereby supporting its structural conservation across species. Subcellular localization analysis revealed that the cytoplasmic localization of Vv-circRCD1 was higher than its nuclear localization (Figure 1b). This distribution pattern suggests potential roles for Vv-circRCD1 in post-transcriptional regulation and/or intercellular transport. In the cytoplasm, circRNAs have been reported to interact with various RNA-binding proteins and miRNAs, thereby influencing gene expression at the post-transcriptional level [38]. For example, some circRNAs act as miRNA sponges, sequestering miRNAs and preventing them from binding to their target mRNAs, ultimately leading to increased expression of the target genes [39]. Moreover, the cytoplasmic localization of Vv-circRCD1 may also be related to its potential involvement in intercellular transport. CircRNAs can be packaged into extracellular vesicles and transported between cells, playing roles in cell-to-cell communication [40]. The high cytoplasmic abundance of Vv-circRCD1 makes it a likely candidate for such intercellular transport processes, which could have important implications for plant development, stress responses, and other physiological processes.

4.2. Grapevine Vv-circRCD1 Alters Root Phenotypes in Arabidopsis

CircRNAs have emerged as key regulators of plant development, particularly in root system architecture modulation. For instance, in wheat demonstrated that 23 differentially expressed circRNAs under low-nitrogen conditions promote root growth, highlighting their role in nutrient acquisition strategies [41]. Similarly, in soybean, the Gm03circRNA1785, gma-miR167c, GmARF6 and GmARF8 regulatory module orchestrates lateral root development through auxin signaling pathway modulation [42]. These findings underscore the conserved function of circRNAs in root system plasticity across species. Our findings reveal that Vv-circRCD1 functions as a negative regulator of primary root elongation but a positive regulator of lateral root formation. Vv-circRCD1 may modulate auxin polar transport and distribution in root tips, thereby inhibiting the meristematic activity of primary root apical meristems and leading to the shortening of primary roots (Figure 2). Such validation is particularly critical in future work, given the limitations in inferring grapevine-specific regulatory mechanisms from heterologous systems. For the increased root hair density (Figure 3), the concurrent increase in root hair density and length expands the root surface area for water and nutrient uptake, and enhances the exclusion of excess Na+ from root tips. Consistent with our miRNA interaction assay results, Vv-circRCD1 was found to directly sponge Vvi-miR399, a conserved miRNA that targets PHO2 (a key regulator of phosphorus homeostasis). This sequestration of Vvi-miR399 by Vv-circRCD1 likely modulates phosphorus uptake and utilization in plants, thereby promoting the initiation and elongation of root hairs. This phenotype suggests that Vv-circRCD1 may participate in redirecting growth resources from primary root elongation to lateral root proliferation, potentially enhancing the root system’s ability to explore a broader soil volume under stress conditions. This architectural remodeling could be advantageous for water and nutrient foraging under suboptimal conditions, including salinity.

4.3. Vv-circRCD1 Enhances Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis and Grapevine

While early plant circRNA research predominantly focused on sequencing and identification, recent studies have increasingly revealed their functional significance in stress adaptation. For example, rice circRNA Os06circ000871 was shown to enhance salt tolerance by regulating the expression of ion transporter genes through miRNA sponging [43]. Similarly, overexpression of Vv-circSIZ1 in grapevine callus significantly improved salt tolerance by modulating antioxidant enzyme activities and maintaining ion homeostasis [11]. Like these characterized circRNAs, Vv-circRCD1 also exerts its salt tolerance function via the ceRNA mechanism. However, it exhibits distinct regulatory specificity compared to previously reported stress-responsive circRNAs. For instance, circR5g05160 in rice enhances immunity against M. oryzae. through pathogen-associated molecular pattern-triggered signaling, a function unrelated to abiotic stress tolerance. In contrast, Vv-circRCD1 specifically targets the miR399 regulatory module—a pathway that bridges phosphate nutrient homeostasis and salt stress adaptation, which has not been documented in other plant stress-responsive circRNAs. This unique regulatory mode expands our understanding of how circRNAs coordinate nutrient metabolism and stress tolerance in plants.

Divergent research objects and phenotypic effects. Our previous study focused on Vv-circPAS1, demonstrating that its overexpression improved salt tolerance only in grapevine callus, with no salt-tolerant phenotype observed in transgenic Arabidopsis or grape tissue-culture seedlings. In this study, we demonstrated that Vv-circRCD1 exhibits tissue-specific expression patterns and responds dynamically to salt stress in grapevine. Notably, Arabidopsis and grapevine plants overexpressing Vv-circRCD1 showed significantly enhanced salt tolerance, as evidenced by improved growth performance and reduced physiological damage under salt stress conditions (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Mechanistically, the salt tolerance conferred by Vv-circRCD1 is likely underpinned by the coordinated regulation of ion homeostasis, ROS detoxification, and ABA-mediated stress signaling. These pathways may have synergistically contributed to the stress adaptation phenotype observed in Vv-circRCD1 overexpression lines. This protective effect was more pronounced for the circular form compared to its linear fragment, highlighting the structural advantages of circRNAs in stress adaptation [44]. This indicates that the circular structure of Vv-circRCD1 is a necessary condition for realizing its full regulatory potential in salt stress adaptation. While our data confirm Vv-circRCD1 modulates root architecture and salt tolerance, whether it acts synergistically or antagonistically with VvRCD1 remains unclear, and this question warrants further investigation in future studies.

4.4. Vv-circRCD1 Potentially Functions by Sequestering miR399 Family Members

The competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis posits that circRNAs, through their miRNA response elements, can sequester miRNAs away from their target mRNAs, thereby modulating gene expression networks [38,45,46]. This regulatory mechanism has been increasingly validated in plant stress responses [47,48], where circRNAs act as molecular decoys to alleviate miRNA-mediated repression of stress-responsive genes [28]. In this work, a novel Vv-circRCD1-Vvi-miR399 regulatory axis was discovered in grapevines. This is the first report of a circRNA-mediated module connecting phosphate homeostasis and salt stress adaptation in perennial fruit crops, which represents a key mechanism gap in current plant circRNA research.

We found that Vv-circRCD1 targets Vvi-miR399 family members (Figure 6) and Vvi-miR399 family genes likely mediate early responses to salt stress in grapevines. (Figure S2), which were known regulators of phosphate homeostasis and stress responses in plants [37,49]. Beyond its conserved role in phosphate signaling, Vvi-miR399 exerts a causal effect on salt tolerance by targeting PHO2—a ubiquitin ligase that coordinates phosphate transporters (PHT family) and sodium antiporters (NHX family) [50]. It has been reported that miR399 expression was induced by salt stress in various plant species, and its overexpression can improve salt tolerance by regulating ion transporter genes [51]. The interaction between Vv-circRCD1 and miR399 family members may therefore represent a conserved mechanism for stress signaling pathways.

The target genes of miR399, which encode phosphate transporters (VIT_205s0049g00920.1), phospholipase D (VIT_212s0035g00200.1), tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase (VIT_209s0002g04530.1), G-type lectin receptor kinases (VIT_206s0004g01410.1), were identified, and the expression patterns of such genes were consistent with that of Vv-circRCD1 under salt stress (Figure 7). It has been reported that these targets of miR399 are potentially involved in salt stress. In Arabidopsis, phosphate transporters (PHTs) were down-regulated under salt stress [50]. In Populus tomentosa, PeGLABRA3 activated phospholipase D (PLDδ) transcription under salt stress, conferring Na+ and ROS homeostasis via PLDδ and phosphatidic acid signaling [52]. In Arabidopsis, the pldα1 mpk3 double mutant shows increased resistance to salinity and ABA tolerance during germination compared to single mutants and wild type [53]. Protein kinase family, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, receptor-like kinases (RLKs), sucrose nonfermenting1 (SNF1)-related protein kinases (SnRKs), and calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs/CPKs), are essential for plant development [54,55] and stress responses [56,57]. For example, the receptor kinases family, which plays a key role in the plant’s response to salt stress [58,59]. A unique molecular mechanism was uncovered in this study. Unlike the previous study, which did not explore miRNA regulatory, this work identifies a specific interaction between Vv-circRCD1 and Vvi-miR399.

Co-expression correlation analysis across the salt stress time course uncovered dynamic associations between Vv-circRCD1 and its candidate target genes: Specifically, Vv-circRCD1 showed a strong negative correlation with VIT_212s0035g00200.1 and VIT_212s0059g02000.1 at 1 day post salt stress (1 dpi), with VIT_218s0001g11720.1 at 3 dpi, and with VIT_213s0067g03280.1 at 5 dpi. In contrast, positive regulatory patterns were observed at other time points: Vv-circRCD1 exhibited a strong positive correlation with VIT_213s0067g03280.1 at 2 dpi, and with VIT_218s0001g11720.1 (concurrently with the negative correlation with VIT_213s0067g03280.1) at 5 dpi (Figure S3). Therefore, we hypothesized that the upregulated expression of Vv-circRCD1 could sequester Vvi-miR399, attenuate its target cleavage activity against downstream genes, and ultimately mediate the upregulation of target genes in grapevines under salt stress. However, this regulatory mechanism requires further experimental validation. We will focus on verifying the Vv-circRCD1-miRNA-target gene network and analyzing its interaction with the linear transcript to better clarify this mechanism in grapevine salt stress response.

5. Conclusions

This study identifies Vv-circRCD1—a tissue-specific, nucleocytoplasmic-localized circRNA in grapevine—as a novel regulator that modulates root architecture and enhances salt tolerance in plants by acting as a miRNA sponge targeting Vvi-miR399. This is the first report demonstrating that Vv-circRCD1 mediates grapevines’ salt tolerance via the Vv-circRCD1–Vvi-miR399 module, uncovering a new circRNA-dependent mechanism for plant abiotic stress adaptation. As a valuable molecular target, Vv-circRCD1 provides genetic resources for breeding salt-tolerant grape varieties. Future research will validate its function in grapevines and explore its synergistic interactions with other stress-responsive genes, laying a foundation for sustainable viticulture in saline-alkali soils.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010072/s1, Table S1: Primers used for validating Vv-circRCD1 in grapevine. Table S2: The primers for cloning circRNA formation sequences. Table S3: The primers for cloning flanking intron sequences of circRNAs. Table S4: Primers for overexpression vectors used to construct Vv-circRCD1 and linear fragments. Table S5: Primers used to verify the transient and stable expression of Vv-circRCD1. Table S6: Primers of grapevine Vvi-miR399 precursor sequence. Figure S1: Prediction of interaction network Vvi-miR399 family members and their target genes. Figure S2: RT-qPCR analysis of the abundances of the Vvi-MIR399 gene family members under various stress conditions. Figure S3: Heat map of Vv-circRCD1 and miR399 target genes after exposure to 300 mM NaCl solution for 0 (a), 1 (b), 2 (c), 3 (d), and 5 d (e).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X.; methodology, D.F.; software, J.L. (Junpeng Li); investigation, Y.T., L.Z. (Lipeng Zhang) and J.L. (Jingjing Liu); validation, J.L. (Jingjing Liu); formal analysis, C.L. and L.W.; resources, H.L. and Z.Z.; data curation, Y.S. and J.L. (Jingjing Liu); writing—original draft preparation, J.L. (Jingjing Liu); writing—review and editing, J.L. (Jingjing Liu) and Y.R.; visualization, J.L. (Jingjing Liu); supervision, L.Z. (Long Zhou), Y.R. and C.M.; project administration, L.Z. (Long Zhou), Y.R. and C.M.; funding acquisition, L.Z. (Long Zhou), Y.R. and C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202446), the AI+ project of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2024AIZD010), the Forestry and Grassland Science and Technology Project of the Autonomous Region (XJLCKJ-2025-09), the Key Discipline Construction Project of Xinjiang Agricultural University (34190000203), and the High-level Talents Scientific Research Cultivation Program (2525GCCRC).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Doubao 11.8.0 for the purposes of professional English polishing during the first round of revision. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, C.; Chen, L. Circular RNAs: Characterization, cellular roles, and applications. Cell 2022, 185, 2016–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Fan, H.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, S.; Li, S.; Cheng, Y.; Meng, X.; Chen, F.; Shao, Z.; et al. Comprehensive regulatory networks for tomato organ development based on the genome and RNAome of MicroTom tomato. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, C.; Li, W.; Wang, G.; Yang, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, B.; Gao, R.; Jia, C. Transcriptomic analysis of ncRNAs and mRNAs interactions during drought stress in switchgrass. Plant Sci. 2024, 339, 111903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Saha, B.; Jaiswal, S.; Angadi, U.; Rai, A.; Iquebal, M. Genome-wide identification and characterization of tissue-specific non-coding RNAs in black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1079221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Feng, X.; Xu, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Mao, Y.; Xie, W.; Liu, T.; et al. CircZmMED16 delays plant flowering by negatively regulating starch content through its binding to ZmAPS1. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 1142–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yi, Y.; Ge, S.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C.; Xie, Q.; Wang, H.; Qian, Y.; et al. Circular RNAs derived from MIR156D promote rice heading by repressing transcription elongation of pri-miR156d through R-loop formation. Nat. Plants 2025, 11, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huo, H.; Qi, D.; Dong, X.; Tian, L.; Liu, C.; Cao, Y. Integrated omics reveal the mechanisms underlying softening and aroma changes in pear during postharvest storage and the role of melatonin. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Liu, M.; Ma, D.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Han, B. Identification of circular RNAs and their targets during tomato fruit ripening. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 136, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Xu, S.; Cao, G.; Chen, S.; Zhang, T.; Yang, B.B.; Zhou, G.; Yang, X. A novel peptide encoded by a rice circular RNA confers broad-spectrum disease resistance in rice plants. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Wang, S.; Liao, W.; Ouyang, M.; Lin, S.; Lin, R.; Sarris, P.F.; Michalopoulou, V.; Feng, X.; et al. The circular RNA circANK suppresses rice resistance to bacterial blight by inhibiting microRNA398b-mediated defense. Plant Cell 2025, 37, koaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Sun, B.; Fan, Z.; Su, Y.; Zheng, C.; Chen, W.; Yao, Y.; Ma, C.; Du, Y. Vv-circSIZ1 mediated by pre-mRNA processing machinery contributes to salt tolerance. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Yao, Y.; Ma, C.; Li, J.; Du, Y. The antisense circRNA VvcircABH controls salt tolerance and the brassinosteroid signaling response by suppressing cognate mRNA splicing in grape. New Phytol. 2024, 245, 1563–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ren, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yin, Y.; Han, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, D.; et al. Investigation of grapevine circular RNA Vv-circPAS1 revealed the function on root development and salt stress resistance. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Luo, M.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Wang, L.; Song, S.; Zhao, L.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; et al. Characterization and cloning of grape circular RNAs identified the cold resistance-related Vv-circATS1. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 966–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overmyer, K.; Tuominen, H.; Kettunen, R.; Betz, C.; Langebartels, C.; Sandermann, H.; Kangasjarvi, J. Ozone-sensitive Arabidopsis rcd1 mutant reveals opposite roles for ethylene and jasmonate signaling pathways in regulating superoxide-dependent cell death. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1849–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlfors, R.; Lang, S.; Overmyer, K.; Jaspers, P.; Brosché, M.; Tauriainen, A.; Kollist, H.; Tuominen, H.; Belles-Boix, E.; Piippo, M.; et al. Arabidopsis RADICAL-INDUCED CELL DEATH1 belongs to the WWE protein–protein interaction domain protein family and modulates abscisic acid, ethylene, and methyl jasmonate responses. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 1925–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujibe, T.; Saji, H.; Arakawa, K.; Yabe, N.; Takeuchi, Y.; Yamamoto, K.T. A methyl viologen-resistant mutant of Arabidopsis, which is allelic to ozone-sensitive rcd1, is tolerant to supplemental Ultraviolet-B irradiation. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainonen, J.; Jaspers, P.; Wrzaczek, M.; Lamminmäki, A.; Reddy, R.A.; Vaahtera, L.; Brosché, M.; Kangasjärvi, J. RCD1–DREB2A interaction in leaf senescence and stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem. J. 2012, 442, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar-Agarwal, S.; Zhu, J.; Kim, K.; Agarwal, M.; Fu, X.; Huang, A.; Zhu, J.-K. The plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter SOS1 interacts with RCD1 and functions in oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 18816–18821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Pang, J.; Shi, H.; Li, T.; Meng, H.; Kong, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.K.; Wang, Z. The Sm core protein SmEb regulates salt stress responses through maintaining proper splicing of RCD1 pre-mRNA in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Wu, H.; Deng, Z.; Cai, T.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Waterhouse, P.M.; White, R.G.; Liang, D. Control of root-to-shoot long-distance flow by a key ROS-regulating factor in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2476–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, T.; Shimura, Y.; Okada, K. The IRE gene encodes a protein kinase homologue and modulates root hair growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002, 30, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, J.; Wu, F.; Wen, H.; Liu, X.; Luo, W.; Gao, L.; Jiang, Z.; Mo, B.; Chen, X.; Kong, W.; et al. RCD1 promotes salt stress tolerance in Arabidopsis by repressing ANAC017 activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, X. Machine learning approaches for plant miRNA prediction: Challenges, advancements, and future directions. Agric. Commun. 2023, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, L. MicroRNAs in Plants Development and Stress Resistance.pdf. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 5909–5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mou, F.; Tian, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Q.; Li, X. Genome-wide small RNA analysis of soybean reveals auxin-responsive microRNAs that are differentially expressed in response to salt stress in root apex. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 6, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barciszewska-Pacak, M.; Milanowska, K.; Knop, K.; Bielewicz, D.; Nuc, P.; Plewka, P.; Pacak, A.; Vazquez, F.; Karlowski, W.; Jarmolowski, A.; et al. Arabidopsis microRNA expression regulation in a wide range of abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ma, Y.; Guo, T.; Li, G. Identification, biogenesis, function, and mechanism of action of circular RNAs in plants. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Watts, R.; Luo, H. Non-coding RNAs in plant stress responses: Molecular insights and agricultural applications. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 3195–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; He, J.; Xu, W.; Ma, C.; Ren, Y.; Liu, H. Integrative investigation of root-related mRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs of “Muscat Hamburg” (Vitis vinifera L.) grapevine in response to root restriction through transcriptomic analyses. Genes 2022, 13, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Fan, D.; Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Guo, D.; et al. Functional differences of grapevine circular RNA Vv-circPTCD1 in Arabidopsis and grapevine callus under abiotic stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clough, S.J.; Bent, A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2008, 16, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Zheng, H.; Cai, W.; Xu, P. A protocol for measuring the response of Arabidopsis roots to gravity and treatment for simulated microgravity. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; He, N.; Hou, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X. Factors influencing leaf chlorophyll content in natural forests at the biome scale. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhao, P. psRNATarget: A plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W155–W159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ren, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yin, Y.; Han, B.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Fan, D.; et al. Identification and analysis of the MIR399 gene family in grapevine reveal their potential functions in abiotic stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Jensen, T.; Clausen, B.; Bramsen, J.; Finsen, B.; Damgaard, C.; Kjems, J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 2013, 495, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, M.S.; Sharp, P.A. Emerging roles for natural microRNA sponges. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, R858–R861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louis, C.; Desoteux, M.; Coulouarn, C. Exosomal circRNAs: New players in the field of cholangiocarcinoma. Clin. Sci. 2019, 133, 2239–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Fan, X.; Liu, T.; Wang, S.; Zhao, G. Genome-wide analysis of differentially expressed profiles of mRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs during Cryptosporidium baileyi infection. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; You, Q.; Shen, X.; Guo, W.; Jiao, Y. Genome-wide identification and characterization of circular RNAs by high throughput sequencing in soybean. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yuan, M.; Zhao, Y.; Quan, Q.; Yu, D.; Yang, H.; Tang, X.; Xin, X.; Cai, G.; Qian, Q.; et al. Efficient deletion of multiple circle RNA loci by CRISPR-Cas9 reveals Os06circ02797 as a putative sponge for OsMIR408 in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1240–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, S.; Chen, M. Characterization and function of circular RNAs in plants. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memczak, S.; Jens, M.; Elefsinioti, A.; Torti, F.; Krueger, J.; Rybak, A.; Maier, L.; Mackowiak, S.D.; Gregersen, L.H.; Munschauer, M.; et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 2013, 495, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Xu, C.; Kang, J.; Xiao, L.; Wu, M.; Xiong, J.; Guo, X.; Liu, H. Endogenous miRNA Sponge lincRNA-RoR Regulates Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 in Human Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Dev. Cell 2013, 25, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xu, Y.; Song, Y.; Fan, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Chen, C.; Ma, C. Hierarchical Regulatory Networks Reveal Conserved Drivers of Plant Drought Response at the Cell-Type Level. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2415106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Song, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, L.; He, J.; et al. The microRNA-encoded peptide miPEP398b regulates heat tolerance in grapevine. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, D.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; He, J.; Yang, X.; Hang, R.; Jia, H.; Mo, B.; Tian, F.; et al. INDETERMINATE1 autonomously regulates phosphate homeostasis upstream of the miR399-ZmPHO2 signaling module in maize. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2208–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Wang, D.; Jiang, P.; Jia, W.; Li, Y. Variation of PHT families adapts salt cress to phosphate limitation under salinity. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 1549–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegler, J.L.; Oultram, J.M.J.; Grof, C.P.L.; Eamens, A.L. Molecular manipulation of the miR399/PHO2 expression module alters the salt stress response of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants 2020, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yin, K.; Yao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, N.; et al. Populus euphratica GLABRA3 binds PLDδ promoters to enhance salt tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadovič, P.; Šamajová, O.; Takáč, T.; Novák, D.; Zapletalová, V.; Colcombet, J.; Šamaj, J. Biochemical and genetic interactions of Phospholipase D Alpha 1 and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase 3 affect Arabidopsis stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ma, L.; Yang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Li, Q.; Ni, X.; Kudla, J.; Song, C.; Guo, Y. The Ca2+ Sensor SCaBP3/CBL7 Modulates Plasma Membrane H+-ATPase Activity and Promotes Alkali Tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1367–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, A.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, J.; Hao, G.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Xie, Q.; Xia, Y.; Yin, X. The protein kinase complex CBL10–CIPK8–SOS1 functions in Arabidopsis to regulate salt tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 1801–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zelicourt, A.; Colcombet, J.; Hirt, H. The role of MAPK modules and ABA during abiotic stress signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ding, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Guo, Y.; Gong, Z. Protein kinases in plant responses to drought, salt, and cold stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, C.; He, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Bhadauria, V.; Wang, S.; Cheng, W.; Liu, H.; et al. Natural variations of maize ZmLecRK1 determine its interaction with ZmBAK1 and resistance patterns to multiple pathogens. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 1606–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Yu, Q.; Tang, L.; Ji, W.; Bai, X.; Cai, H.; Liu, X.; Ding, X.; Zhu, Y. GsSRK, a G-type lectin S-receptor-like serine/threonine protein kinase, is a positive regulator of plant tolerance to salt stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2013, 170, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.