Abstract

Across plants, the PEBP gene family is reported to regulate storage organ formation, developmental plasticity, and floral transitioning. However, its evolutionary dynamics and functional diversification within Allium species remain poorly understood. In this study, we performed genomic and transcriptomic analyses of the PEBP gene family across three economically important Allium species, including Allium fistulosum (bunching onion), Allium sativum (garlic), and Allium cepa (onion), identifying 19, 17, and 21 PEBP genes, respectively. The genes were assigned into five subfamilies (FT-like, TFL1-like, MFT-like, BFT-like, and PEBP-like), with MFT-like members being the most abundant. Structural analysis revealed strong conservation of key motifs (e.g., GxHR and DPDxP) across species, while substantial variation in intron–exon organization suggested subfunctionalization. Collinearity analysis indicated that segmental duplication primarily drove PEBP gene expansion in garlic and onion, whereas tandem duplication was absent in bunching onion. Promoter analysis showed enrichment of light- and hormone-related cis-regulatory elements, implicating their involvement in environmental and hormonal regulation. Expression profiling demonstrated clear tissue specificity, with AsPEBP11/13/14/16/19 exhibiting significantly higher expression in normal flowers than in abnormal ones, suggesting key roles in floral morphogenesis. Together, these findings will prove useful for future breeding programs aimed at improving reproductive development and fertility in Allium species.

1. Introduction

The highly conserved phosphatidylethanolamine-binding proteins (PEBP) are involved in a number of processes in plants, including sink–source allocation, tuber formation, architecture determination, seed dormancy, and floral transitioning [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Moreover, PEBPs have been found to be key regulators of the vegetative-to-reproductive transition [7,8,9,10]. The plant PEBP gene family comprises three subgroups: FLOWERING LOCUS T-likes, which encode florigens [11,12]; TERMINAL FLOWER1 (TFL1)-likes, which inhibit flowering [8,13]; and MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 (MFT)-likes, which regulate the germination process [14,15].

In Arabidopsis thaliana, the florigen Flowering Locus T (FT) promotes flowering [1,16,17,18], whereas Brother of FT and TFL1 (BFT), Arabidopsis Thaliana Centroradialis (ATC), and Terminal Flower 1 (TFL1) repress flowering. TFL1 and FT, respectively, act as transcriptional co-repressor and co-activator. In the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and mediated by 14-3-3 proteins, TFL1 and FT form either the florigen repression complex (FRC) or florigen activation complex (FAC) by interacting with the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor (TF) Flowering Locus D (FD) [17,19,20]. Competition for binding to FD at target genes results in antagonism between TFL1 and FT [21,22]. Despite their opposing functions, both proteins differ minimally in their amino acid sequences [18,23,24]. In fact, a change in only a single amino acid can convert TFL1 into FT or FT into TFL1 [23,24,25,26]. Finally, PEBPs regulate sink–source dynamics by interacting with Sucrose Transporters (SUTs) or Sugar Will Eventually be Exported Transporters (SWEETs) [27,28].

The monocotyledonous Allium L. genus (family Amaryllidaceae, order Asparagales) encompasses more than 900 species distributed across semi-arid, tropical, and temperate regions of Asia, North America, Europe, and northern Africa, as well as other geographies [29]. Allium species typically form bulbs valued for their edible fleshy scales, distinctive flavor, and nutritional content. Furthermore, Allium plants are used medicinally due to their cardioprotective, antithrombotic, antibiotic, and anticarcinogenic effects. Economically important cultivated species include chive (Allium schoenoprasum), bunching onion (Allium fistulosum), Chinese chive (Allium tuberosum), onion (Allium cepa), leek (Allium ampeloprasum), and garlic (Allium sativum). The chromosome-level assemblies of garlic (16.24 Gb), onion (15.78 Gb), and bunching onion (11.27 Gb) highlight the genus’s complex evolutionary history, including whole-genome duplication (WGD) events that contributed to the large genome sizes characteristic of Allium species. These resources are essential for identifying genes and regulatory networks underlying key agronomic traits such as bulb formation, flavor compound biosynthesis, and stress resistance [30,31,32].

Although PEBP genes are well-known to play diverse roles in plants, their functions in garlic (A. sativum) remain poorly understood. Investigating the evolutionary characteristics and transcriptomic profiles of PEBPs will help clarify their roles in A. sativum. Different species have variable numbers of PEBP genes: 6, 12, and 16 have been identified in the dicots A. thaliana [33], tomato [34], and soybean [35], respectively, and 20 and 24 have been identified in the monocots rice [36] and maize [37]. As in many plant species, development in Allium is strongly influenced by PEBP family gene regulation. In garlic, one TFL2-like gene and six FT-like genes have been associated with floral induction and bulb formation [6], and vernalization is associated with the upregulation of AsFT2, a likely florigen [38,39]. In onion, AcFT1 and AcFT4 hold opposing roles in bulbing (AcFT1 promotes, AcFT4 inhibits), whereas AcFT2 promotes flowering [3,40]. To clarify the roles of this gene family in Allium species, we performed gene structure, phylogenetic, collinearity, expression pattern, and cis-acting element analyses. Understanding PEBP regulatory functions in floral organ development across Allium life forms will aid in breeding improved varieties and illuminating the specific roles of individual PEBP members in regulating flowering across Allium species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PEBP Protein Discovery and Characterization

Full-length PEBP protein amino acid sequences in A. thaliana and rice were collected from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 20 May 2025) based on reported gene accession numbers [33,36]. Genomic information and annotation files for Allium cepa, Allium fistulosum, and Allium sativum were obtained from the CNGBdb (China National GeneBank DataBase, https://db.cngb.org/, accessed on 21 May 2025).

Six A. thaliana PEBP protein sequences were used as BLASTP v2.12.0 queries (E-value ≤ 10−5) against the whole-genome protein datasets of A. sativum, A. cepa, and A. fistulosum. In parallel, the PEBP domain (PF01161) Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile was collected from the Pfam database and used to discover PEBP sequences within the Allium genomes in HMMER v3.3.2 (E ≤ 10−5). Candidate sequences retrieved by both approaches were analyzed using SMART (https://smart.embl.de/, accessed on 23 May 2025) and NCBI Batch CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi, accessed on 23 May 2025) to verify the presence of conserved PEBP domains.

ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 23 May 2025) was utilized to estimate the grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), molecular weight (MW), and theoretical isoelectric point (PI) of each protein. In addition, the subcellular localization of all identified PEBP genes was predicted using the WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/, accessed on 23 May 2025).

Multiple sequence alignment of PEBP amino acid sequences from A. thaliana, rice, A. sativum, A. fistulosum, and A. cepa was achieved using MEGA X (https://www.megasoftware.net/, accessed on 23 May 2025). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted with the neighbor-joining (NJ) approach under the JTT (Jones–Taylor–Thornton) matrix model, using default parameters and 1000 bootstrap replicates. Finally, the resultant phylogeny was refined and visualized with Figtree v1.4.5 (https://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/Figtree/, accessed on 23 May 2025). Amino acid sequences of AsPEBP were aligned using the ClustalW v2.0.11 and visualized using the Jalview (https://www.jalview.org, accessed on 29 December 2025).

2.2. Evaluation of Gene Structures, Protein Motifs, and Cis-Acting Elements

The exon–intron structures of PEBP genes were resolved with the GSDS 2.0 (Gene Structure Display Server, http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/, accessed on 23 May 2025). Conserved motifs within PEBPs were discovered with the MEME (Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation) suite (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme, accessed on 23 May 2025) using a maximum motif number of 15. Promoter sequences, defined as the region 2000 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS), were extracted to identify cis-acting regulation elements via PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 23 May 2025).

2.3. Collinearity and Chromosomal Localization Assessment

The chromosome-specific positions of PEBP family genes were extracted using Allium genomic sequences as well as general feature format (GFF) files in TBtools v2.309 to generate a gene localization map. Collinearity relationships between species pairs were identified with MCScanX ((https://github.com/wyp1125/MCScanX, accessed on 25 May 2025). KaKs_Calculator v2.0 was utilized to calculate substitution rates (synonymous [Ks] and nonsynonymous [Ka]), as well as Ka/Ks ratios, for syntenic PEBP gene pairs.

2.4. Differential Gene Expression Profiling Across Various Tissues

To further investigate the expression of PEBP genes in garlic tissue, the expression of AsPEBP genes in the roots, bulbs, stems, leaves, buds, flowers, and sprouts were analyzed based on A. sativum cv. Ershuizao RNA-Seq data (PRJNA607255), normalized as FPKM (fragment per million exons mapping) [32], and visualized using TBtools v2.309. Only transcripts with an average FPKM value ≥ 10 in at least one of the organs were used for heatmap construction.

2.5. Nucleic Acid Collection, Amplification, and Quantitation

Total RNA was collected following the manufacturer’s instructions using a commercial Quick RNA Isolation Kit (Huayueyang, Beijing, China). A FastQuant RT Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA from 1 µg of total RNA. Reverse transcription was achieved with a HiScript®II First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (including gDNA wiper) (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was carried out on a LightCycler 480 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with Magic SYBR Green qPCR Mix (Magic-bio, Hangzhou, China). The 2−∆∆Ct method was utilized to quantify relative expression, with AsActin as the internal reference gene. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S6. Three independent biological replicates and two technical replicates were utilized for each assay.

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Discovery and Phylogenetic Analysis of the PEBP Gene Family in Allium Species

Fifty-seven PEBP gene family members were identified across the three representative Allium species using a combination of HMM and BLASTP searches. Among them, 19 were found in garlic (A. sativum), 21 in onion (A. cepa), and 17 in bunching onion (A. fistulosum). Based on chromosomal positions, these genes were renamed as AsPEBP1-AsPEBP19, AcPEBP1-AcPEBP21, and AfPEBP1-AfPEBP17 (Table S1).

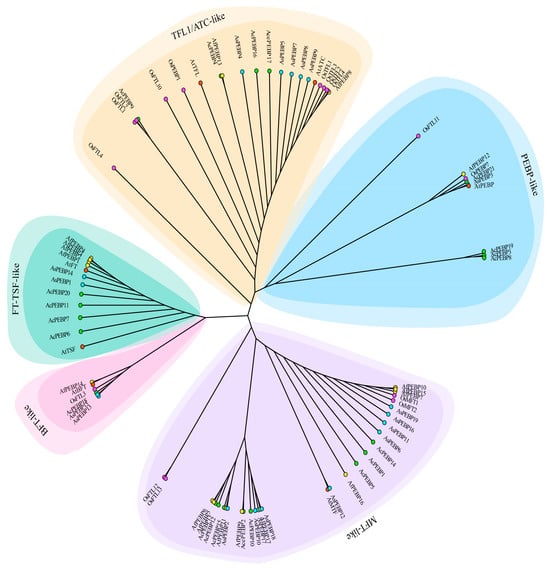

To examine the evolutionary relationships among the Allium PEBP, a phylogenetic (N-J) tree was developed based on multiple-sequence alignment of 81 PEBP protein sequences from A. thaliana, A. sativum, A. fistulosum, A. cepa, and O. sativa (Figure 1, Table S7). The phylogenetic results showed a classification pattern similar to that of A. thaliana and rice, dividing the 57 Allium PEBPs into five subfamilies: TFL1/ATC-like, FT-TSF-like, BFT-like, MFT-like, and PEBP-like.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic assessment of PEBPs from Allium species, A. thaliana, and rice. The proteins are classed into five subfamilies: TFL1/ATC-like (khaki), PEBP-like (light blue), MFT-like (purple), BFT-like (pink), and FT-TSF-like (turquoise). Different species are indicated by solid dots in distinct colors: cyan for garlic (A. sativum), green for onion (A. cepa), yellow for bunching onion (A. fistulosum), red for A. thaliana, and magenta for rice.

Among these, the MFT-like subfamily comprised the largest number of genes (26 total; nine AsPEBP, nine AfPEBP, and eight AcPEBP), followed by the TFL1/ATC-like family (11 genes). The remaining genes were distributed among the FT-TSF-like (10 genes), PEBP-like (six genes), and BFT-like (four genes) groups. In garlic, the MFT-like subfamily comprised the highest number of members (nine AsPEBPs), while the PEBP-like family contained the fewest (one AsPEBP).

3.2. Allium PEBP Protein Properties and Subcellular Locations

The Allium PEBPs displayed considerable variation in length, ranging from 83 aa (AcPEBP19) to 534 aa (AcPEBP8), with an average of 181.98 aa (Table S1). Their molecular weights ranged from 9.85 kDa (AcPEBP19) to 58.30 kDa (AcPEBP8), averaging 20.44 kDa. The predicted pIs ranged from 4.76 to 10.12, with an average of 8.01. Among the Allium PEBPs, 16 were classified as acidic (pI < 7), and 42 had instability indices exceeding 40. Only two proteins (AcPEBP8 and AcPEBP9) exhibited positive GRAVY values, indicating hydrophobicity, whereas the rest of the proteins were hydrophilic.

Subcellular localization analysis revealed that Allium PEBPs were distributed across multiple organelles, including the chloroplast, mitochondria, cytoplasm, nucleus, cytoskeleton, and cell membrane, with most predicted to localize predominantly in the cytoplasm.

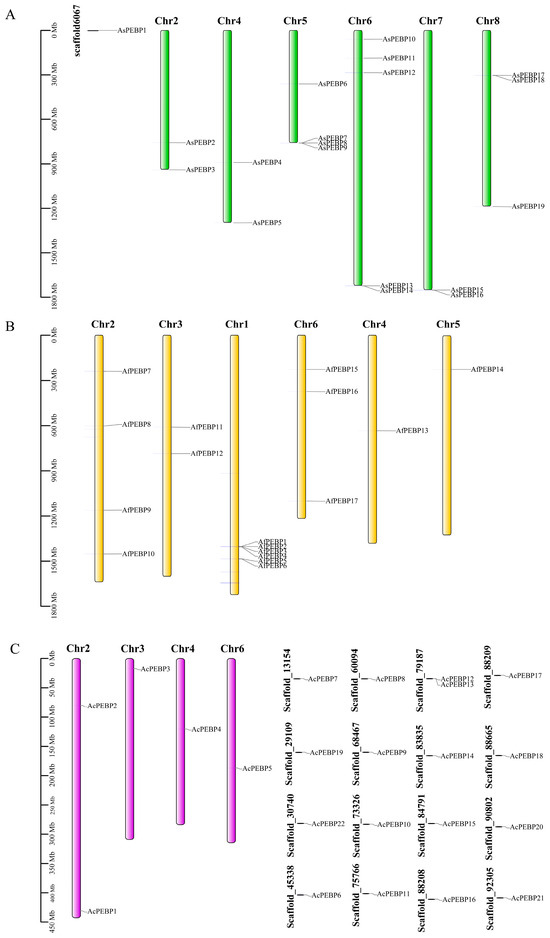

3.3. Chromosome-Specific Locations and Duplication Analysis of Allium PEBP Genes

The chromosomal coordinates of the 57 PEBP genes were extracted from the genome annotation file of three Allium species. The PEBP genes were organized irregularly across chromosomes (Figure 2). In A. fistulosum, the highest number of PEBP genes (six) was found on chromosome 1, whereas only one gene was present on AfChr4 and AfChr5. In A. cepa, a single PEBP gene was identified on AcChr3, AcChr4, and AcChr6. Due to the incomplete assembly of the onion genome, 17 PEBP genes were located on unanchored scaffolds. In A. sativum, the AsPEBP genes were mainly distributed across six chromosomes (AsChr2, AsChr4, AsChr5, AsChr6, AsChr7, and AsChr8), with AsChr6 containing the highest number. In addition, AsPEBP1 was located on an unanchored scaffold.

Figure 2.

Chromosomal arrangement of PEBP genes across three Allium species. (A) Distribution in garlic (A. sativum). (B) Distribution in bunching onion (A. fistulosum). (C) Distribution in onion (A. cepa).

Collinearity analysis within Allium species revealed six homologous gene pairs in garlic, 12 in bunching onion, and seven in onion (Figure 3). Tandem duplications were not observed in bunching onion. Segmental duplication analysis indicated four and six pairs of segmentally duplicated genes, respectively, in garlic and onion, suggesting that both segmental and tandem duplication contributed to PEBP gene diversification in these species, with segmental duplication being the dominant mechanism. In contrast, segmental duplication was the sole driver of PEBP gene amplification in bunching onion. Analysis uncovered that the PEBP gene family in garlic, onion, and bunching onion expanded primarily through segmental duplication, leading to an uneven distribution of genes across their genomes.

Figure 3.

Chromosome-specific locations and collinearity analysis of PEBP genes in Allium species. PEBP genes are distributed across different chromosomes, and duplicated gene pairs are joined by red lines.

3.4. Syntenic and Selective Pressure Analysis of Allium PEBP Genes

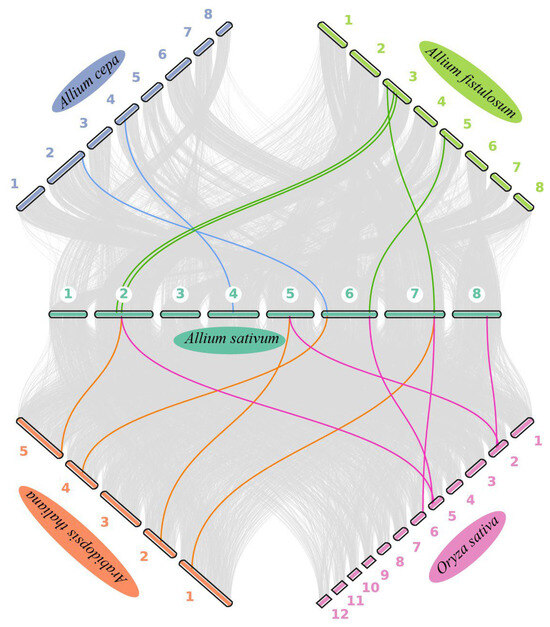

To further decipher the evolutionary relationships among Allium PEBP genes, collinearity maps were generated between garlic and the other two Allium species, as well as A. thaliana and rice (Figure 4). Garlic exhibited two, four, five, and five homologous gene pairs with onion, bunching onion, rice, and A. thaliana, respectively (Table S3).

Figure 4.

Syntenic relationships among PEBP genes from three Allium species, A. thaliana, and rice. Grey background lines represent collinear blocks across the various genomes, while PEBP gene pairs are highlighted in distinct colors.

Selective pressure analysis based on Ka/Ks ratios (Table S2) showed that Ka values of the homologous gene pairs ranged from 0.002 to 0.331, while Ks values ranged from 0.024 to 3.279. Most Allium PEBP gene pairs (96%) had Ka/Ks ratios < 1, highlighting strong purifying selection during evolution. Only one pair (AcPEBP4 and AcPEBP6) exhibited a Ka/Ks > 1, suggesting a relatively faster pace of evolution as well as the presence of positive selection pressures. Six homologous gene pairs were identified in garlic (AsPEBP3-AsPEBP17, AsPEBP2-AsPEBP19, AsPEBP10-AsPEBP13, AsPEBP10-AsPEBP10, AsPEBP10-AsPEBP18, and AsPEBP19-AsPEBP10), all with Ka/Ks ratios < 1, indicating that these orthologous pairs were under purifying selection. Notably, the homologous gene pair AsPEBP10-AsPEBP10 underwent tandem duplication due to intra-sequence homology (Table S2). Together, these results indicate that purifying selection has been the dominant force acting on the PEBP gene family in the genus Allium, ensuring the functional conservation of these critical genes.

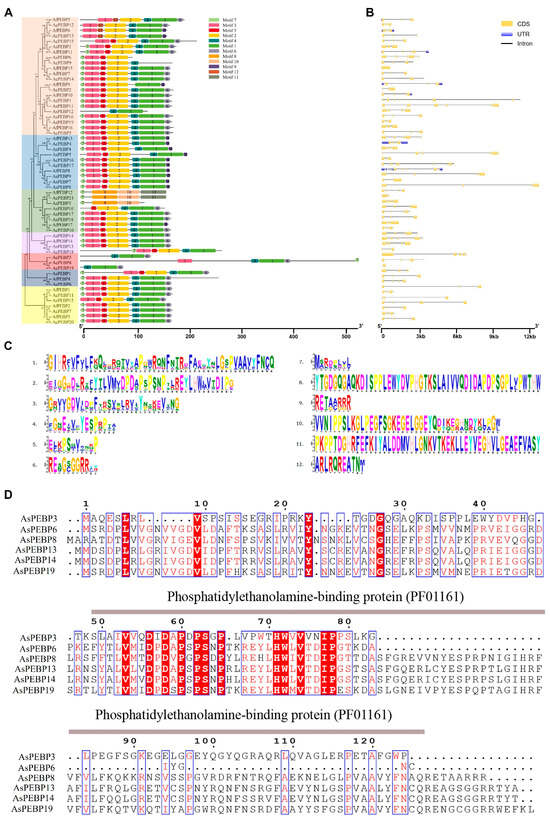

3.5. Evaluation of Allium PEBP Gene Structures and Conserved Motifs

To gain a comprehensive understanding of Allium PEBP gene members, conserved motifs were identified using the MEME suite, and gene structures were investigated (Figure 5, Table S4). The PEBP gene family members across the three Allium species were grouped into seven distinct subfamilies (Figure 5A). A total of 12 conserved motifs were discovered among Allium PEBPs, with their specific sequences shown in Figure 5C. In total, 10, 11, and 12 conserved motifs were detected in garlic, onion, and bunching onion, respectively.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, and conserved motif compositions of PEBP genes in Allium species. (A) Phylogenetic tree and predicted motif distribution of PEBPs in Allium species. (B) Exon–intron structures of Allium PEBP genes. (C) Conserved motifs discovered in Allium PEBPs. (D) Multiple sequence alignment of representative Allium PEBPs.

The distribution of conserved motifs among proteins within the same clade was largely similar. Most Allium PEBPs contained the GxHR motif (Motif 1), a hallmark of the PEBP family. Except for AsPEBP3, AsPEBP12, AfPEBP12, AcPEBP3, AcPEBP8, AcPEBP19, and AcPEBP21, all other Allium PEBPs possessed the DPDxP motif (Motif 2), another major functional motif. All PEBP members contained Motif 3 and Motif 7, and most exhibited Motifs 2–5, indicating a high level of structural conservation within the Allium PEBP family. Moreover, AsPEBP3, AcPEBP21, and AfPEBP12 shared Motifs 7, 8, and 10, suggesting that they may perform analogous biological functions.

Figure 5B shows that the garlic AsPEBP genes contained one to five introns, with 50% of the genes harboring three introns and two genes containing five introns. The onion AcPEBP genes possessed zero to seven introns. Only one gene lacked introns, half contained four introns, and two had seven introns. The bunching onion AfPEBP genes contained zero to eight introns, with one gene lacking introns and eight genes containing four introns. Overall, members of the same subfamily exhibited comparable exon–intron organizations, suggesting a potential relationship between gene structure, biological function, regulatory mechanisms, and evolutionary divergence. Amino acid sequence alignment showed that the identities among AsPEBPs were more than 55% (Figure 5D). All AsPEBP have conserved motif DPDxP and GxHR, which are critical for anion-binding. Particularly, motif GxHR has a preference for Ile residues.

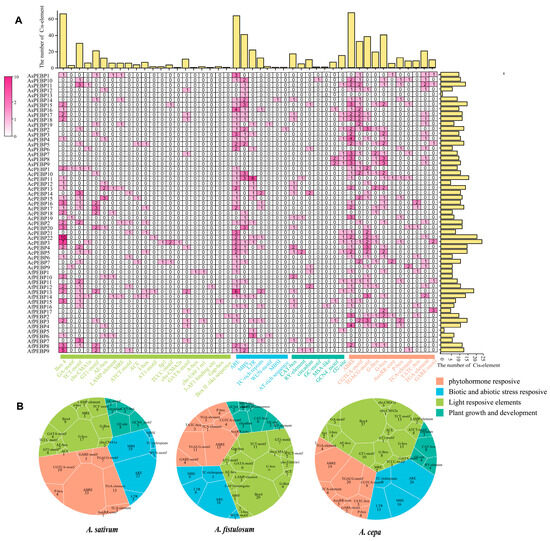

3.6. Cis-Regulatory Elements Present Within Allium PEBP Gene Promoters

To explore the possible mechanisms of regulation of Allium PEBP gene expression, cis-regulatory elements were predicted within the 2000 bp upstream regions of each PEBP gene across the three Allium species (Figure 6). The identified elements were associated with phytohormone responsiveness (e.g., abscisic acid, auxin, gibberellin), light responsiveness (e.g., phytochrome and cryptochrome signaling), growth- and development-related processes (e.g., meristem expression, seed development), and abiotic or external stress responsiveness (e.g., drought, low temperature). In Allium species, these regulatory themes are particularly relevant: light and photoperiod cues are known to govern flowering and bulb formation in onion and bunching onion, whereas hormone signaling—especially auxin and cytokinin—plays a key role in garlic clonal propagation [31,32]. These motifs likely fine-tune PEBP gene expression in response to environmental and endogenous signals, thereby modulating their functional roles.

Figure 6.

Identification of cis-acting elements within Allium PEBP gene promoters. (A) Distribution of cis-acting elements within Allium PEBP promoters. The bar plot indicates the number of cis-elements by category (vertical) and by individual gene (horizontal). (B) Proportion of the four major types of response elements in different Allium species.

Light-related elements were the most frequently discovered, with 251 occurrences. PEBP genes in onion and bunching onion contained the highest number of light-responsive elements, followed by hormone-responsive elements, and the fewest growth- and development-related elements. In contrast, garlic PEBP genes contained the greatest number of hormone-responsive elements, followed by light-responsive elements. Among the various promoter motifs, ABRE (hormone response), ARE (stress response), and Box4 (light response) were the most prevalent across all species. The cis-element profiles of garlic PEBP genes align with hormonal regulation of asexual propagation, whereas those of onion and bunching onion correspond to photoperiodic regulation of sexual reproduction.

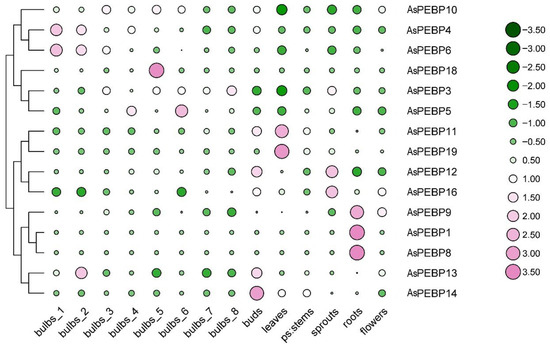

3.7. Tissue-Specific AsPEBP Gene Expression

The tissue-specific expression patterns of AsPEBP genes in garlic were dissected using published transcriptome data (PRJNA607255), including for flowers, roots, sprouts, pseudostems, leaves, buds, and bulbs at various developmental stages (Figure 7, Table S5) [32]. Four genes (AsPEBP2, AsPEBP7, AsPEBP15, and AsPEBP17) were excluded from the analysis due to lack of detectable expression in any tissue. Notably, AsPEBP1, AsPEBP8, and AsPEBP9 exhibited expression restricted to roots. AsPEBP11 and AsPEBP19 showed high expression in leaves, while AsPEBP11, AsPEBP12, AsPEBP13, and AsPEBP14 were strongly expressed in buds. In addition, AsPEBP4, AsPEBP5, AsPEBP6, AsPEBP13, and AsPEBP18 displayed elevated expression during different stages of bulb development. In contrast, most AsPEBP genes showed low expression levels in pseudostems and flowers, indicating organ-specific regulation and minimal functional redundancy within the gene family.

Figure 7.

Tissue-specific expression profiles of AsPEBP genes in garlic based on published data. A heatmap was generated based on row-normalized absolute FPKM values for each gene across various organs, including roots, bulbs, pseudostems, leaves, buds, flowers, and sprouts. Bulb stages 1–8, respectively, correspond to 192-, 197-, 202-, 207-, 212-, 217-, 222-, and 227-day-old bulbs. The color scale with pink and green represent high and low values, respectively.

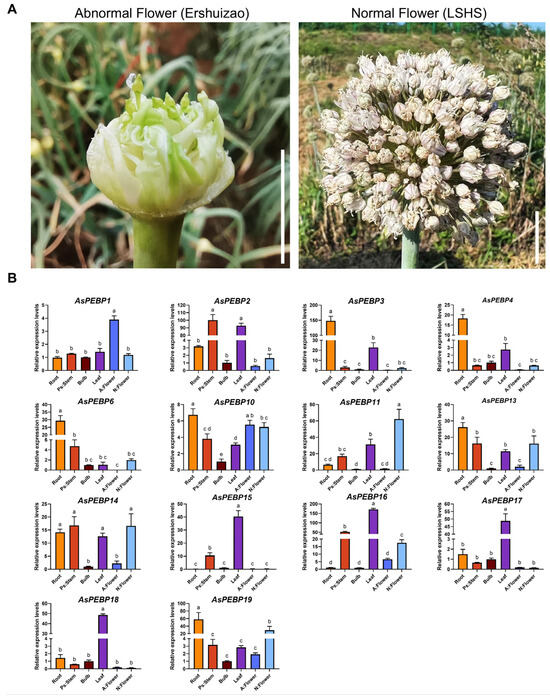

3.8. Expression Analysis of the AsPEBP Genes by RT-qPCR

Clonal propagation is utilized for modern garlic varieties, and only a small proportion can flower and produce seeds. Anther and stigma abortion, along with inflorescence bulblet formation, are the major causes of floral abnormalities (Figure 8A). To investigate the expression patterns of AsPEBP genes in different tissues and in normal versus abnormal flowers, 14 candidate genes were selected for RT-qPCR validation (Figure 8B). Expression analysis across garlic tissues revealed that all 14 genes exhibited substantial expression in bulb tissue. AsPEBP3, AsPEBP4, AsPEBP6, AsPEBP13, AsPEBP14, and AsPEBP19 showed significantly higher expression in roots, suggesting roles in nutrient transport or stress response. AsPEBP2, AsPEBP15, AsPEBP16, AsPEBP17, and AsPEBP18 showed elevated expression in leaves, implying involvement in leaf development or photoperiod sensing. Notably, five genes (AsPEBP11, AsPEBP13, AsPEBP14, AsPEBP16, and AsPEBP19) displayed significantly higher expression in normal flowers compared to abnormal ones, suggesting that these may be potential candidate genes involved in garlic flower morphogenesis.

Figure 8.

Expression profiles of 14 AsPEBP genes across different garlic tissues. (A) Phenotypes of the abnormal flower (Ershuizao) and the normal flower (LSHS) in garlic. White lines indicate one centimeter. (B) Expression profiles of 14 AsPEBP genes in different garlic tissues. The x-axis represents tissue type, including roots, pseudostems, bulbs, leaves, and abnormal and normal flowers. The y-axis indicates the relative expression levels of AsPEBP genes. Significant differences (denoted by different lowercase letters) were determined using one-way ANOVA at p < 0.05. Ps:Stem indicates pseudostem; A: Flower indicates abnormal flower; N: Flower indicates normal flower.

4. Discussion

The Allium genus, which includes economically important species such as garlic (A. sativum), onion (A. cepa), and bunching onion (A. fistulosum), is characterized by large genome sizes and notable pungency. Although the PEBP gene family is known to regulate key developmental processes such as flowering, its functions in Allium species remain poorly characterized. In this study, 57 PEBP genes were identified across three Allium species (19 in garlic, 17 in onion, and 21 in bunching onion), representing a notable expansion relative to eudicot models such as A. thaliana, which possesses only six members (Figure 1; Table S1). This expansion is consistent with patterns observed in other monocots, including rice (24 PEBP members) and maize (20 PEBP members), and suggests lineage-specific diversification in Allium [36,37].

The predominance of the MFT-like subfamily (26 genes) in Allium contrasts with A. thaliana [33], tomato [34], potato [41], and Brassica napus [42], where FT-like and TFL1-like genes are more prevalent. This divergence may reflect distinct evolutionary pressures associated with perennial growth habits or environmental adaptation [43]. However, previous studies reported no detectable MFT-like homologs across the garlic genome [44,45], likely due to differences in sequence alignment or phylogenetic reconstruction methods. Chromosomal localization analysis highlighted that PEBP genes are unevenly organized across chromosomes in all three Allium species (Figure 2). Similarly irregular distributions have been reported in other plants, including carrot [46], tomato [34], tumorous stem mustard [47], and rice [36].

In plants, various forms of duplication are major drivers of gene family expansion and diversification [48,49,50]. In Allium, segmental duplication was identified as the predominant mechanism driving PEBP family expansion in garlic and onion, while tandem duplication was absent in bunching onion. This differs from the pattern observed in tomato, where both segmental and tandem duplications contributed to PEBP family proliferation [34]. Most duplicated gene pairs showed Ka/Ks ratios < 1, indicating strong purifying selection that preserves functional stability, consistent with observations in soybean and A. thaliana [35]. In contrast, the AcPEBP4–AcPEBP6 pair (Ka/Ks > 1) may have undergone neofunctionalization under positive selection, paralleling the functional diversification reported among FT homologs in sugar beet [26].

The conserved motifs GxHR and DPDxP are essential for the biological functioning of PEBPs [51]. Mutations within or adjacent to these regions can disrupt interactions between FT and FD proteins by altering phosphate ion binding [52]. The strong conservation of motifs, particularly Motifs 3 and 7 across all Allium PEBP members, highlights the structural importance of the PEBP domain in maintaining protein stability. This conservation is consistent with the “external loop” region described by Ho and Weigel [23], which decides the functional specificity between FT and TFL1 in A. thaliana.

The observed variation in intron–exon structure (ranging from zero to eight introns across Allium species) exceeds that typically found in eudicots. For example, A. thaliana PEBP genes contain only one to four introns. Such structural plasticity may enhance regulatory complexity through alternative splicing, facilitating functional diversification similar to that reported for CENL1 genes in poplar [11]. Moreover, the exclusive presence of Motifs 7, 8, and 10 in AsPEBP3, AcPEBP21, and AfPEBP12 suggests possible subfunctionalization within specific clades. This pattern aligns with the findings of Ahn et al. [24], who reported that divergence in the external loop grants antagonistic activity between the floral regulators TFL1 and FT. The structural characteristics identified in Allium PEBPs may therefore underlie functional specificity, potentially mediating the antagonistic roles these proteins play in flowering regulation and bulb development.

Cis-regulatory elements in gene promoters play essential roles in transcription initiation and regulation, acting as specific protein-binding sites [53,54]. Light influences numerous developmental processes, with the photoperiod pathway regulating flowering largely through the activation of FT expression [55]. Promoter motifs such as the G-box, I-box, and GT1-motif are key components of light-responsive gene regulation [56]. Promoter analyses of Allium PEBP genes revealed an abundance of light- and hormone-responsive elements, underscoring the integration of environmental and endogenous cues in controlling PEBP expression. The predominance of ABRE elements indicates strong abscisic acid (ABA) responsiveness, consistent with the established role of MFT-like genes in seed germination regulation [14,19]. This observation aligns with the findings of Xi et al. [14], who showed that MFT regulates seed germination through a negative feedback mechanism modulating ABA signaling in A. thaliana.

Transcriptome profiling across garlic tissues revealed that AsPEBP genes exhibit distinct spatial expression patterns consistent with their presumed roles in organ development (Figure 7). For instance, AsPEBP1, AsPEBP8, and AsPEBP9 were exclusively expressed in roots, suggesting functions in root development or nutrient uptake, similar to FT-like genes in other monocots that modulate root growth under stress conditions [3]. Conversely, AsPEBP11 and AsPEBP19 showed high expression in leaves, indicating possible involvement in leaf morphogenesis or photosynthesis-related processes. Four genes (AsPEBP11, AsPEBP12, AsPEBP13, and AsPEBP14) were strongly expressed in buds, implying roles in bud initiation or dormancy release, consistent with the contribution of PEBP genes to meristem maintenance in species such as potato [2]. Additionally, AsPEBP4, AsPEBP5, AsPEBP6, AsPEBP13, and AsPEBP18 were upregulated during bulb development, suggesting participation in bulb formation and sink–source allocation, consistent with observations in onion where AcFT1 promotes bulbing [3].

qRT-PCR analysis of 14 AsPEBP genes across various garlic tissues revealed distinct expression patterns, with several genes showing markedly higher expression in normal flowers than in abnormal ones (Figure 8). Five genes (AsPEBP11, AsPEBP13, AsPEBP14, AsPEBP16, and AsPEBP19) exhibited significantly higher expression in normal flowers, suggesting roles in flower morphogenesis as floral promoters or organ identity regulators. For instance, AsPEBP11 and AsPEBP19 (FT-like orthologs) may function similarly to AcFT2 in onion to promote flowering [3], while AsPEBP13 and AsPEBP14 may parallel StSP6A in potato in regulating meristem transition [2]. Their upregulation implies possible interactions with FD-like TFs to activate floral integrators like LFY, consistent with the FAC model [20]. The reduced expression of these genes in abnormal flowers may result from environmental or genetic disruptions in flowering pathways. The contrasting expression of AsPEBP4 (bulb-promoting) and AsPEBP11 (flower-promoting) suggests a trade-off between sexual and asexual reproduction, similar to other geophytes where FT homologs regulate both flowering and storage organ formation [57]. These expression patterns highlight potential molecular markers or genome editing target sites for breeding fertile garlic varieties, and future work should include functional validation via CRISPR/Cas9 and exploration of epigenetic regulation mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

In this study, 57 PEBP genes were identified across three Allium species: 19 in garlic, 17 in onion, and 21 in bunching onion. Their gene structures, conserved domains, protein motifs, and cis-regulatory elements were characterized. Phylogenetic analysis grouped these genes into five subfamilies, consistent with patterns observed in other plant species. Collinearity analysis indicated that segmental duplication primarily drove PEBP gene expansion in garlic and onion, whereas tandem duplication was absent in bunching onion. Expression profiling using RNA-seq and qRT-PCR demonstrated clear tissue specificity, with five AsPEBP genes exhibiting elevated expression in normal flowers, suggesting roles in floral development. Overall, this study helps to clarify the evolutionary history of PEBP genes within the genus Allium and provides a basis for molecular breeding efforts in garlic.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010069/s1. Table S1: Detailed information on the PEBP genes identified in three Allium species; Table S2: Segmental and tandem duplication events of PEBP genes within three Allium species; Table S3: Syntenic relationships between garlic PEBP genes and those of other Allium species, Arabidopsis thaliana, and rice; Table S4: Analysis and distribution of conserved motifs among Allium PEBPs; Table S5: Average FPKM values of PEBP gene transcripts across different garlic tissues; Table S6: Primer sequences used for AsPEBP and reference genes in qRT-PCR analysis. Table S7: Protein sequence of All PEBPs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y. and Z.L.; methodology, L.Y.; software, L.Y., M.M., J.Z. and Y.M.; validation, W.C.; formal analysis, M.M. and H.L.; investigation, L.Y., P.W., G.G., H.L., Y.Z., M.Y. and F.L.; resources, L.Y., Z.L. and W.C.; data curation, Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.C., Z.L. and J.L.; visualization, L.Y. and Y.M.; supervision, W.C.; project administration, W.C.; funding acquisition, L.Y., Z.L. and W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Earmarked Fund for CARS-24-G-23, the Earmarked Fund for Sichuan Innovation Team Program of CARS (SCCXTD-2024-22), the Sichuan Province Engineering Technology Research Center of Vegetables (2023PZSC0302), the “5 + 1” Agricultural Frontier Technology Research Project of SAAS (5+1QYGG003), and the Sichuan Provincial Finance Department (1+9KJGG001).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the NCBI SRA repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra, accessed on 15 December 2025), accession number PRJNA607255.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Corbesier, L.; Vincent, C.; Jang, S.; Fornara, F.; Fan, Q.; Searle, I.; Giakountis, A.; Farrona, S.; Gissot, L.; Turnbull, C.; et al. FT Protein Movement Contributes to Long-Distance Signaling in Floral Induction of Arabidopsis. Science 2007, 316, 1030–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, C.; Abelenda, J.A.; Cruz-Oró, E.; Cuéllar, C.A.; Tamaki, S.; Silva, J.; Shimamoto, K.; Prat, S. Control of flowering and storage organ formation in potato by FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nature 2011, 478, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.; Baldwin, S.; Kenel, F.; McCallum, J.; Macknight, R. FLOWERING LOCUS T genes control onion bulb formation and flowering. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeggangers, H.A.; Rosilio-Brami, T.; Bigas-Nadal, J.; Rubin, N.; van Dijk, A.D.; Nunez de Caceres Gonzalez, F.F.; Saadon-Shitrit, S.; Nijveen, H.; Hilhorst, H.W.; Immink, R.G.; et al. Tulipa gesneriana and Lilium longiflorum PEBP Genes and Their Putative Roles in Flowering Time Control. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 59, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelenda, J.A.; Bergonzi, S.; Oortwijn, M.; Sonnewald, S.; Du, M.; Visser, R.G.F.; Sonnewald, U.; Bachem, C.W.B. Source-Sink Regulation Is Mediated by Interaction of an FT Homolog with a SWEET Protein in Potato. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 1178–1186.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Michael, T.E.; Faigenboim, A.; Shemesh-Mayer, E.; Forer, I.; Gershberg, C.; Shafran, H.; Rabinowitch, H.D.; Kamenetsky-Goldstein, R. Crosstalk in the darkness: Bulb vernalization activates meristem transition via circadian rhythm and photoperiodic pathway. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusinkiewicz, P.; Erasmus, Y.; Lane, B.; Harder, L.D.; Coen, E. Evolution and development of inflorescence architectures. Science 2007, 316, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlgren, A.; Gyllenstrand, N.; Källman, T.; Sundström, J.F.; Moore, D.; Lascoux, M.; Lagercrantz, U. Evolution of the PEBP Gene Family in Plants: Functional Diversification in Seed Plant Evolution. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifschitz, E.; Ayre, B.G.; Eshed, Y. Florigen and anti-florigen—A systemic mechanism for coordinating growth and termination in flowering plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Périlleux, C.; Bouché, F.; Randoux, M.; Orman-Ligeza, B. Turning Meristems into Fortresses. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruonala, R.; Rinne, P.i.L.H.; Kangasjärvi, J.; van der Schoot, C. CENL1 Expression in the Rib Meristem Affects Stem Elongation and the Transition to Dormancy in Populus. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.X.; Wang, S.; Wen, J.; Zhou, S.Z.; Jiang, X.D.; Zhong, M.C.; Liu, J.; Dong, X.; Deng, Y.; Hu, J.Y.; et al. Evolution of FLOWERING LOCUS T-like genes in angiosperms: A core Lamiales-specific diversification. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 3946–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida de Jesus, D.; Batista, D.M.; Monteiro, E.F.; Salzman, S.; Carvalho, L.M.; Santana, K.; André, T. Structural changes and adaptative evolutionary constraints in FLOWERING LOCUS T and TERMINAL FLOWER1-like genes of flowering plants. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 954015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, W.; Liu, C.; Hou, X.; Yu, H. MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 regulates seed germination through a negative feedback loop modulating ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 1733–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, H.; Källman, T.; Lagercrantz, U. Early evolution of the MFT-like gene family in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 70, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Daimon, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Ikeda, Y.; Ichinoki, H.; Notaguchi, M.; Goto, K.; Araki, T. FD, a bZIP protein mediating signals from the floral pathway integrator FT at the shoot apex. Science 2005, 309, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigge, P.A.; Kim, M.C.; Jaeger, K.E.; Busch, W.; Schmid, M.; Lohmann, J.U.; Weigel, D. Integration of spatial and temporal information during floral induction in Arabidopsis. Science 2005, 309, 1056–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardailsky, I.; Shukla, V.K.; Ahn, J.H.; Dagenais, N.; Christensen, S.K.; Nguyen, J.T.; Chory, J.; Harrison, M.J.; Weigel, D. Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 1999, 286, 1962–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Fan, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Hu, R.; Fu, Y. Identification of a Soybean MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 Homolog Involved in Regulation of Seed Germination. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taoka, K.; Ohki, I.; Tsuji, H.; Furuita, K.; Hayashi, K.; Yanase, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Nakashima, C.; Purwestri, Y.A.; Tamaki, S.; et al. 14-3-3 proteins act as intracellular receptors for rice Hd3a florigen. Nature 2011, 476, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanano, S.; Goto, K. Arabidopsis TERMINAL FLOWER1 is involved in the regulation of flowering time and inflorescence development through transcriptional repression. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3172–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Klasfeld, S.; Jeong, C.W.; Jin, R.; Goto, K.; Yamaguchi, N.; Wagner, D. TERMINAL FLOWER 1-FD complex target genes and competition with FLOWERING LOCUS T. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, W.W.; Weigel, D. Structural features determining flower-promoting activity of Arabidopsis FLOWERING LOCUS T. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.H.; Miller, D.; Winter, V.J.; Banfield, M.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yoo, S.Y.; Henz, S.R.; Brady, R.L.; Weigel, D. A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzawa, Y.; Money, T.; Bradley, D. A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7748–7753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pin, P.A.; Benlloch, R.; Bonnet, D.; Wremerth-Weich, E.; Kraft, T.; Gielen, J.J.L.; Nilsson, O. An antagonistic pair of FT homologs mediates the control of flowering time in sugar beet. Science 2010, 330, 1397–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, C.; Grof, C.P. Sucrose transporters of higher plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeena, G.S.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, R.K. Structure, evolution and diverse physiological roles of SWEET sugar transporters in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 100, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M. All about Allium. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R1449–R1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Liu, X.; Zhou, B.; Tian, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zong, H.; Qi, J.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, P.; et al. Chromosome-level genomes of three key Allium crops and their trait evolution. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, N.; Hu, Z.; Miao, J.; Hu, X.; Lyu, X.; Fang, H.; Zhou, Y.-M.; Mahmoud, A.; Deng, G.; Meng, Y.-Q.; et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of bunching onion illuminates genome evolution and flavor formation in Allium crops. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, N.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Qiao, X.; Lu, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. A Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of Garlic (Allium sativum) Provides Insights into Genome Evolution and Allicin Biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1328–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickland, D.P.; Hanzawa, Y. The FLOWERING LOCUS T/TERMINAL FLOWER 1 Gene Family: Functional Evolution and Molecular Mechanisms. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Jia, X.; Yang, Z.; Fu, Q.; Yang, H.; Xu, X. Genome-Wide Identification of PEBP Gene Family in Solanum lycopersicum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, Q.; Ji, Y.; Li, C.; Fang, C.; Wang, M.; Wu, M.; et al. Functional Evolution of Phosphatidylethanolamine Binding Proteins in Soybean and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhu, M.; Guo, Y.; Sun, J.; Ma, W.; Wang, X. Genomic Survey of PEBP Gene Family in Rice: Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis, and Expression Profiles in Organs and under Abiotic Stresses. Plants 2022, 11, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevskaya, O.N.; Meng, X.; Hou, Z.; Ananiev, E.V.; Simmons, C.R. A Genomic and Expression Compendium of the Expanded PEBP Gene Family from Maize. Plant Physiol. 2007, 146, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohkin Shalom, S.; Gillett, D.; Zemach, H.; Kimhi, S.; Forer, I.; Zutahy, Y.; Tam, Y.; Teper-Bamnolker, P.; Kamenetsky, R.; Eshel, D. Storage temperature controls the timing of garlic bulb formation via shoot apical meristem termination. Planta 2015, 242, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, A.K.; Shalom, S.R.; Faigenboim-Doron, A.; Teper-Bamnolker, P.; Salam, B.B.; Daus, A.; Kamenetsky, R.; Eshel, D. Differential carbohydrate gene expression during preplanting temperature treatments controls meristem termination and bulbing in garlic. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 150, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, R.K.; Han, J.S.H.; Vijayakumar, H.; Subramani, B.; Thamilarasan, S.K.; Park, J.-I.; Nou, I.-S. Molecular and Functional Characterization of FLOWERING LOCUS T Homologs in Allium cepa. Molecules 2016, 21, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jin, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, N.; Li, S.; Si, H.; Rajora, O.P.; Li, X.-Q. Genome-wide identification of PEBP gene family members in potato, their phylogenetic relationships, and expression patterns under heat stress. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 4683–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, H.; Du, D. Identification, evolution and expression analyses of the whole genome-wide PEBP gene family in Brassica napus L. BMC Genom. Data 2023, 24, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko-Suzuki, M.; Kurihara-Ishikawa, R.; Okushita-Terakawa, C.; Kojima, C.; Nagano-Fujiwara, M.; Ohki, I.; Tsuji, H.; Shimamoto, K.; Taoka, K.I. TFL1-Like Proteins in Rice Antagonize Rice FT-Like Protein in Inflorescence Development by Competition for Complex Formation with 14-3-3 and FD. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Tan, Y.; Cai, C.; Zhang, B. Identification and expression analysis of phosphatidy ethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) gene family in cotton. Genomics 2019, 111, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh-Mayer, E.; Faigenboim, A.; Ben Michael, T.E.; Kamenetsky-Goldstein, R. Integrated Genomic and Transcriptomic Elucidation of Flowering in Garlic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, D.; Ou, C.; Hao, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhuang, F. Genome-wide identification and characterization profile of phosphatidy ethanolamine-binding protein family genes in carrot. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1047890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Gu, L.; Tan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hui, F.; He, X.; Chang, P.; Gong, D.; Sun, Q. Genome-wide analysis and identification of the PEBP genes of Brassica juncea var. Tumida. BMC Genomics 2022, 23, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Landherr, L.L.; Frohlich, M.W.; Leebens-Mack, J.; Ma, H.; dePamphilis, C.W. Patterns of gene duplication in the plant SKP1 gene family in angiosperms: Evidence for multiple mechanisms of rapid gene birth. Plant J. 2007, 50, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchy, N.; Lehti-Shiu, M.; Shiu, S.-H. Evolution of Gene Duplication in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 2294–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Li, Q.; Yin, H.; Qi, K.; Li, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S.; Paterson, A.H. Gene duplication and evolution in recurring polyploidization–diploidization cycles in plants. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, H.; Zou, D.; Yuan, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Expression Profile of FaFT1 and Its Ectopic Expression in Arabidopsis Demonstrate Its Function in the Reproductive Development of Fragaria × ananassa. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2022, 41, 1687–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Fang, L.; Gao, F.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chang, L.; et al. Mutation of SELF-PRUNING homologs in cotton promotes short-branching plant architecture. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 2543–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Roeder, R.G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 769–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Sun, K.; Mackaluso, J.D.; Seddon, A.E.; Jin, R.; Thomashow, M.F.; Shiu, S.-H. Cis-regulatory code of stress-responsive transcription in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14992–14997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, Q.; Hu, B.; Wu, W. Comparative transcriptome profiling of Arabidopsis Col-0 in responses to heat stress under different light conditions. Plant Growth Regul. 2016, 79, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, G.; Pichersky, E.; Malik, V.S.; Timko, M.P.; Scolnik, P.A.; Cashmore, A.R. An evolutionarily conserved protein binding sequence upstream of a plant light-regulated gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 7089–7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosa, J.; Bellinazzo, F.; Kamenetsky Goldstein, R.; Macknight, R.; Immink, R.G.H. PHOSPHATIDYLETHANOLAMINE-BINDING PROTEINS: The conductors of dual reproduction in plants with vegetative storage organs. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2845–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.