Abstract

Understanding how cultivated xerophytic shrubs physiologically regulate canopy water loss under anomalously wet conditions is crucial for predicting ecohydrological responses and for providing practical guidance in landscape restoration under the ongoing warming–wetting trend on the northern Loess Plateau. This study tested hypotheses concerning the hierarchy of atmospheric and soil-water controls on canopy transpiration (Ec), stomatal conductance (gs), the strength of canopy–atmosphere coupling, and species-specific soil-water sensitivities and water-use strategies in Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila. Concurrent measurements of branch-level sap flow, meteorological variables, and soil water content (SWC) at multiple depths were conducted in two adjacent stands during the wet season of a climatically wet year (July–September 2017). Meteorological factors, particularly vapor pressure deficit (VPD), were the dominant drivers of daily Ec and gs, whereas SWC exerted secondary but species-specific influences. Both shrubs were strongly coupled to the atmosphere, with consistently low decoupling coefficients (Ω ≈ 0.11–0.15) on daily scales. C. korshinskii maintained stable water use through access to deeper soil, whereas S. psammophila responded sensitively to fluctuations in shallow SWC. These contrasting patterns indicate depth-partitioned water-use strategies and a context-dependent continuum between isohydric and anisohydric behavior rather than fixed species traits. The findings support improved parameterization of shrub water use in ecohydrological models, more effective water-use management, and informed species selection and nursery practices for landscape restoration in semi-arid regions experiencing warming–wetting climatic shifts.

1. Introduction

Arid and semi-arid regions, which occupy approximately 41% of the Earth’s terrestrial surface, are characterized by limited water availability—a key factor shaping the structure and functioning of dryland ecosystems [1,2]. These ecosystems are highly vulnerable to land degradation, soil erosion, and desertification, and are strongly influenced by human activities [3,4]. Understanding plant water use, biosphere–atmosphere interactions, and their broader implications for climate regulation, hydrology, and ecological dynamics is essential in the context of ongoing climate change.

The Loess Plateau and Mu Us Desert in Northwest China have long suffered from severe soil degradation due to intensive land use, the high erodibility of loess deposits, and harsh climatic conditions. In response, large-scale ecological restoration initiatives—most notably the Grain for Green program—have nearly doubled the region’s vegetation cover over the past two decades, transforming vast areas of barren land into grasslands, shrublands, and forests [5,6]. Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila are two dominant pioneer xerophytic shrubs widely used for windbreaks and sand fixation in this region because of their exceptional drought tolerance and ability to establish under adverse environmental conditions [7,8]. Historical records indicate that the afforested area of C. korshinskii exceeds 1.2 million ha across the loess hills and northern deserts of Shaanxi Province. In comparison, S. psammophila occupies approximately 350,000 ha in the desert zones around Yulin City. In counties such as Jiaxian, plantations of these two species together accounted for over 70% the total afforested land.

However, these achievements conceal a fundamental contradiction: on the Loess Plateau, where annual precipitation ranges from 200 to 550 mm, the establishment of dense, water-intensive vegetation has disrupted the region’s fragile water balance. For example, long-term monitoring indicates that cultivation of C. korshinskii accelerates soil water loss, reducing soil water content (SWC) by 0.008–0.016 cm3 cm−3 yr−1 based on over a decade of in situ measurements across the 0–4 m soil profile [9]. This mismatch between vegetation demand and limited soil water supply has led to the widespread formation of dry soil layers, threatening the delicate water balance, the long-term survival of vegetation, and the sustainability of ecological restoration efforts [10,11,12,13].

Efforts to elucidate water-use and drought-resistance mechanisms in xerophytic shrubs have focused on their physiological traits and hydraulic architecture. C. korshinskii exhibits an isohydric strategy, maintaining strict stomatal regulation under water stress and demonstrating high resistance to xylem embolism, albeit at the cost of reduced hydraulic conductivity [14,15,16,17,18]. In contrast, S. psammophila employs an anisohydric strategy, maintaining its stomata open for extended periods during drought, exhibiting high hydraulic conductivity but a correspondingly greater vulnerability to embolism [8,14,15,19,20]. The water sources used by these species have recently been identified through stable-isotope tracing of hydrogen and oxygen. Results show that C. korshinskii primarily absorbs deep soil water through its well-developed taproot system, whereas S. psammophila relies mainly on shallow soil water accessed by its dense fibrous lateral roots [18,21,22]. Advances in sap flow monitoring have further enhanced understanding of how shrub water use links soil and atmospheric processes. Compared with S. psammophila, C. korshinskii exhibits stronger rainfall-induced suppression of sap flow, primarily driven by post-event increases in air humidity and reductions in vapor pressure deficit (VPD), which lower evaporative demand and promote stomatal closure [23]. In contrast, sap flow in S. psammophila displays scale-dependent controls—varying diurnally with solar radiation (Rs), seasonally with air temperature (Ta), Rs, and VPD, and interannually with SWC and leaf area index [24]. To date, the vast majority of studies have focused on sap flow or whole-plant transpiration at the scale of sap flow or whole-plant transpiration, with few explicitly extending to time-continuous physiological responses, such as stomatal conductance (gs) or the strength of canopy–atmosphere coupling.

In recent decades, the northern Loess Plateau has shown a clear trend toward warming and wetting conditions, accompanied by increased precipitation [25,26]. Under such evolving climatic conditions, a mechanistic, physiology-based understanding of the water use of these xerophytic shrubs, particularly in wet years, is critical for diagnosing the formation and tendency of dry soil layers and for anticipating shifts in vegetation community structure and broader ecohydrological trajectories.

While most studies focus on shrub responses under drought stress, a critical gap remains in understanding how atmospheric and soil-water conditions regulate canopy water loss and which species-specific water-use strategies mediate stomatal behavior and canopy–atmosphere coupling under wetter conditions. In this context, we hypothesized that: (1) a distinct hierarchy of atmospheric and soil-water controls governs canopy transpiration (Ec) and gs, with atmospheric conditions expected to dominate even during the wet season of a climatically wet year; (2) the canopies of both shrubs remain strongly coupled to the atmosphere, such that the decoupling coefficient (Ω) stays low and Ec, including nocturnal water loss, is primarily driven by atmospheric factors rather than soil-water availability; and (3) species differences arise from contrasting sensitivity to SWC and depth-partitioned water use, producing context-dependent shifts along the anisohydric–isohydric continuum rather than a fixed, species trait.

To test these hypotheses, our objectives were to: (1) characterize the diurnal and daily dynamics of Ec and gs, including nocturnal Ec, and quantify Ω; (2) determine the relationships between Ec, gs, Ω and key meteorological variables (Rs, VPD, and wind speed) as well as SWC at multiple depths, and assess the relative importance of atmospheric versus soil-water controls; and (3) compare species-specific responses of Ec, gs, and Ω to SWC and infer water-use strategies within the anisohydric–isohydric framework.

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve the objectives of this study, we concurrently monitored branch-level sap flow, meteorological conditions, and SWC at multiple depths in the Liudaogou catchment, Shaanxi Province, China, during the wet season of a climatically wet year (7 July–27 September 2017). Ec was scaled from branch-level sap flow, while gs and Ω were estimated by inverting a modified Penman–Monteith equation. We then (1) quantified the diurnal and daily dynamics of Ec, gs, and Ω; (2) evaluated their responses to meteorological drivers and depth-resolved SWC, and assessed the relative importance of these factors; and (3) compared species-specific patterns of water-use regulation and canopy–atmosphere coupling. The resulting dataset provides empirical constraints to improve and localize ecohydrological models of plant–water interactions under changing climatic conditions, offering practical guidance for species selection in the ecological restoration of water-limited landscapes.

2.1. Study Site and Shrub Species

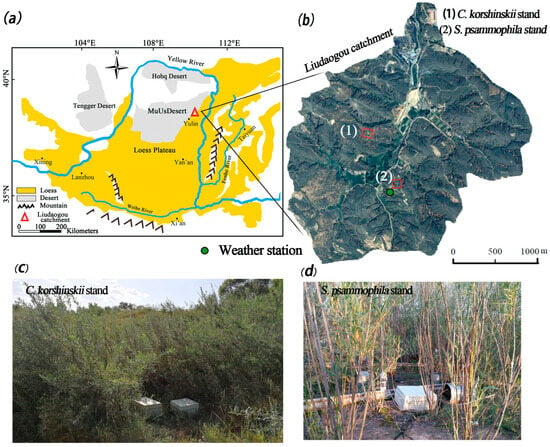

This study was conducted in the Liudaogou catchment (central coordinates: 38.78° N, 110.35° E; mean altitude: 1200 m a.s.l.) in Yulin City, Shaanxi Province, China. The catchment lies near the Mu Us Desert on the northwestern Loess Plateau and is characterized by extensive, highly erodible Quaternary aeolian loess deposits (Figure 1). The region is known as the “water–wind erosion crisscross zone”, featuring rugged terrain with deeply incised gullies and rolling hills formed by the combined fluvial and aeolian processes. Soils are developed from loess and classified as Ustorthents under the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Soil Taxonomy, corresponding to Typic Loaminthic Entisols in the Chinese Soil Taxonomy. These calcareous soils, derived from coarse-grained loess materials, range from loamy sand to loam in texture and exhibit weak cohesion, high permeability, and low water-holding capacity—factors that contribute to their susceptibility to erosion. The regional climate is continental monsoonal, with a mean annual temperature of 8.4 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 437 mm (1971–2013). Reference evapotranspiration averages approximately 1200 mm. Vegetation transitions zonally from forest to desert steppe.

Figure 1.

Site location and experimental stands for investigating divergent water-use strategies between Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila in the semi-arid Loess Plateau. (a) Location of the Liudaogou catchment. (b) Placement of the shrub stands and weather station. Representative images of the (c) C. korshinskii and (d) S. psammophila stands.

Two xerophytic shrubs, Caragana korshinskii (Fabaceae) and Salix psammophila (Salicaceae), dominate the region and are widely used in dryland restoration. C. korshinskii develops a deep taproot system and exhibits intense drought and cold tolerance, exhibiting conservative, isohydric water use. In contrast, S. psammophila possesses an extensive, shallow, fibrous root system and moderate drought tolerance, behaving more anisohydrically, with rapid growth and high resilience to sand burial. The images of soils and particle-size composition (0–100 cm) in the two experimental stands are presented in Figure S1.

Two experimental stands were selected, one for each species (Figure 1b). The C. korshinskii stand, established 15 years prior to the study, was located on the upper part of a hill with a 5° slope (Figure 1c). The S. psammophila stand, planted 7 years prior, was situated on an adjacent hill with a 7° slope (Figure 1d). Both stands developed under natural, unmanaged conditions, without irrigation, pruning, or soil tillage. The two sites were approximately 480 m apart, ensuring similar climatic and edaphic conditions.

2.2. Meteorological Variables and SWC Monitoring

An automatic weather station was installed midway between the two stands to continuously monitor meteorological variables. The station was located in an open area with an unobstructed fetch exceeding 20 m in all directions. Rs (W m−2) was measured using a pyranometer (CNR4; Kipp & Zonen B.V., Delft, The Netherlands). Air temperature (Ta, °C) and relative humidity (RH, %) were monitored using a ventilated temperature-humidity probe (HMP155; Vaisala, Helsinki, Finland) mounted 1.5 m above the ground inside a multi-plate radiation shield to minimize solar heating. Wind speed (u, m s−1) was recorded using a three-cup anemometer (03002; R.M. Young Company, Traverse City, MI, USA) at a height of 2.0 m. Precipitation was measured using a tipping-bucket rain gauge (TE525MM, Texas Electronics, Dallas, TX, USA) with a resolution of 0.1 mm tip−1 and an orifice diameter of 16 cm, installed 0.5 m above the ground.

All sensors were connected to a datalogger (CR1000; Campbell Scientific, Logan, UT, USA), which sampled data every 1 s and stored 10 min averages. Hourly and daily values of Rs, Ta, RH, u, and precipitation were aggregated for subsequent analysis. Rainfall events were identified based on both total precipitation and temporal separation. Successive rainfall records separated by less than 6 h were considered a single event, whereas intervals longer than 6 h were treated as distinct events. Only rainfall events exceeding 1.0 mm in total precipitation were included in analyses.

Soil water content (SWC, cm3 cm−3) was continuously monitored in both stands using time-domain reflectometry sensors (TDR315; Acclima, Inc., Meridian, ID, USA) installed horizontally at depths of 10, 20, 50, and 100 cm. Sensors were carefully inserted into undisturbed soil profiles adjacent to representative plants to minimize disturbance. All TDR sensors at each experimental stand were linked to a CR1000 datalogger, which recorded 1 h averages from 10 min sampling intervals. The resulting dataset captured temporal fluctuations and vertical redistribution of soil water following rainfall events.

2.3. Sap Flow Monitoring and Stand Transpiration Upscaling

Branch-level sap flux density was measured in both C. korshinskii and S. psammophila stands using external heat ratio (EHR) sap flow gauges constructed following the protocol of [27]. In each stand, seven branches from different individuals were selected for EHR gauge installation to monitor in situ raw sap flux density (Vr; cm3 cm−2 h−1). Selected branches represented typical growth conditions and were chosen based on the following criteria: (1) similar branch diameter (7.5–10 mm); (2) healthy foliage with no signs of disease or physical damage; and (3) representative canopy position (mid-canopy, fully sunlit). Each selected branch instrumented with an EHR gauge, and all gauges in each stand were connected to a CR1000 datalogger, which automatically triggered measurements and recorded sap flow signals at 1 h intervals.

At the conclusion of field measurements, each instrumented branch was individually calibrated using the cut-stem gravimetric method under controlled hydraulic pressure to convert Vr to calibrated sap flux density (Vs; cm3 cm−2 h−1). For each instrumented branch, its stem was excised approximately 10 cm above and below the installed gauge while maintaining the original gauge–stem configuration intact. The cut stems were then connected to a purified pressurized water supply, with flow regulated by adjusting the water head between a Mariotte’s bottle and the stem section (maximum 15 m, equivalent to 150 kPa). Calibration was performed independently for all instrumented branches of both species, and the calibration coefficient (Vg/Vrc) was used to calculate Vs. The branch-level transpiration rate (J, cm3 cm−1 h−1) was determined by multiplying vs. by the branch cross-sectional area (a; cm2).

After sap flow monitoring, a “standard branch” was identified in each stand based on median stem size and leaf biomass. All leaves of the standard branch were harvested, and their fresh mass (ms) was measured with an electronic balance. Similarly, the leaves of each instrumented branch were harvested and weighted (mi, for the i-th monitored branch, i = 1, …, 7). The transpiration rate of the i-th instrumented branch (Ji) was normalized to the equivalent rate of the corresponding “standard branch” (Jsi) according to the ratio of leaf mass between branches (Jsi = Ji· mi/ms). Because it was impractical to harvest all leaves within each stand, the total leaf biomass was visually estimated following a commonly used stand-scaling approach. Specifically, for every branch within the stand, its leaf biomass was visually compared to that of the standard branch to estimate the proportional equivalence (e.g., 0.8×, 1.2×, 2× of the standard branch). Summing these proportional values yielded the total number of equivalent standard branches (n) for each stand. Stand-level transpiration rate (Ec, mm h−1) was then upscaled by multiplying the mean Jsi by n and dividing the stand area (A, m2). Basic structural characteristics of the study stands are summarized in Table 1, and the distribution of stem numbers across stem diameter classes in both stands is presented in Figure S2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila Study Stands in the Liudaogou Catchment.

2.4. Derivation of Physiological Proxies: Stomatal Conductance and Decoupling Coefficients

To move beyond canopy transpiration and examine the underlying physiological mechanisms, two key proxies were derived: gs and Ω. These parameters are essential for testing our hypotheses regarding stomatal regulation and canopy–atmosphere coupling.

We estimated gs by inverting the Penman–Monteith equation, using measured Ec and meteorological data. This approach provides an integrated measure of canopy-level stomatal behavior governing plant water loss. Specifically, rearranging the modified Penman–Monteith Equation (1) following [28,29] yields Equation (2).

where Δ is the slope of the saturation vapor pressure–temperature curve (kPa °C−1) [30]; Rnc is the net radiation absorbed by the canopy (MJ m−2 h−1), calculated by scaling the net radiation with the canopy interception fraction [31]; ρa is the density of dry air (kg m−3) [32]; cp is the specific heat of dry air at constant pressure (1.005 × 10−3 MJ kg−1 °C−1) [31]; and λ is the latent heat of vaporization of water (MJ kg−1) [32,33]. The psychrometric constant γ (kPa °C−1) is computed based on atmospheric pressure and the specific heat of air [32,34]. Ktime (3600 s h−1) converts Ec from mm s−1 to mm h−1.

Aerodynamic conductance (ga) was calculated following [35] and the parameterization conventions adopted in the REF-ET model [36]. The conductance was expressed as:

where k (= 0.41) is the von Kármán constant. uz is wind speed (m s−1) at measurement height z (2.0 m in this study); d is zero plane displacement height (0.67 × h, with h being mean canopy height); zw and zh are the heights of wind and humidity/temperature measurements (m), respectively; and zom and zoh are roughness length for momentum and heat/vapor transfer, respectively. Following the FAO-56/ASCE standardized formulation implemented in REF-ET v4.1 [36], these parameters were set to zom = 0.123 × h and zoh = 0.0123 × h, respectively. This empirical relationship has been widely applied for short canopies and low-stature vegetation, providing realistic estimates of boundary-layer resistance in semi-arid shrublands.

Ω quantifies the degree of coupling between canopy transpiration and the atmospheric condition, thereby indicating whether transpiration is primarily controlled by stomata or by available energy. This directly addresses our hypothesis regarding the role of canopy–atmosphere coupling. Ω ranges between 0 and 1 and is calculated following [28]:

Values of Ω approaching 0 indicate strong canopy–atmosphere coupling, where transpiration is highly controlled by stomatal and boundary-layer conductance and proportional to variations in VPD. Conversely, Ω values near 1 signify weak coupling, where transpiration is mainly driven by available energy and stomatal control is less effective on canopy transpiration.

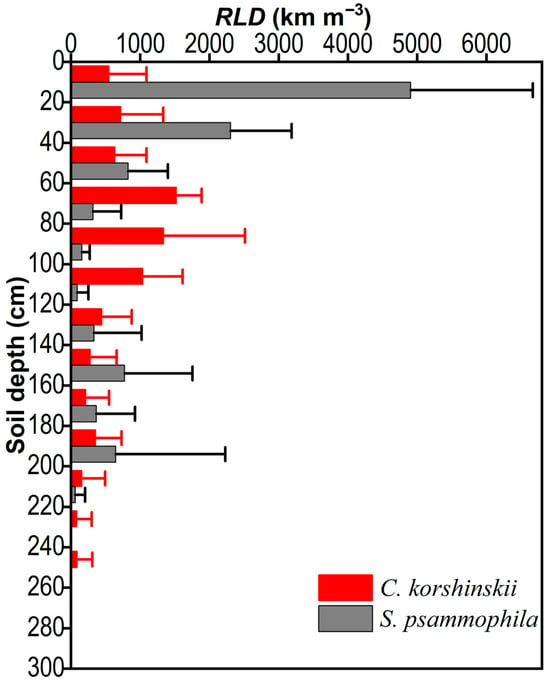

2.5. Fine Root Distribution

To provide independent morphological evidence supporting the inferred differences in water-source partitioning between the two species, fine root distribution was examined across the 0–300 cm soil profile using the soil-core method. In each stand, six soil cores were collected from systematically distributed locations to represent the general rooting zone. To avoid bias toward individual bases, each core was taken midway between adjacent individual shrubs. Undisturbed soil samples were extracted using a cylindrical soil corer (10 cm diameter × 20 cm length) and subsequently sectioned at 20 cm intervals. Roots were carefully separated from the soil, washed, and air-dried. The cleaned root samples were scanned using an optical root scanner, and root morphological traits were analyzed with WinRHIZO Pro 2012b software (Regents Instruments Inc., Québec City, QC, Canada). We quantified hydraulically active lateral roots by calculating the fine root length density (RLD, km m−3), defined as the total length of fine roots (≤2 mm in diameter) per unit volume of soil.

2.6. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were designed to test the study’s hypotheses regarding species-specific environmental controls on water use. Species were treated as fixed effects, and instrumented branches served as the units of replication. Statistical analyses were therefore based on shrub-level mean values derived from multiple observation days per species, ensuring that interspecific comparisons reflected true species differences rather than within-individual variation.

Pearson correlation and linear regression analyses were used to characterize the functional relationships among Ec, gs, and Ω in relation to key meteorological variables (VPD, Rs, and u) and SWC at depths of 10, 20, 50, and 100 cm. Confidence intervals (95%) for all regression fits were calculated and displayed to quantify the uncertainty associated with the modeled relationships. Partial correlation analysis was employed to isolate the independent effects of meteorological variables on Ec, gs, and Ω while controlling for the influences of SWC, and vice versa.

To directly evaluate the relative contributions of atmosphere and SWC, a regression-based relative-importance analysis was performed using Shapley value decomposition. This method partitions the explained variance of Ec, gs, and Ω among the predictors (Rs, VPD, u, and SWC at depths of 10, 20, and 50 cm), providing unbiased estimates of each driver’s contribution—crucial for assessing the environmental control hierarchy between species.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 29 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and figures were prepared with OriginPro 2021 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Meteorological and Soil Water Conditions

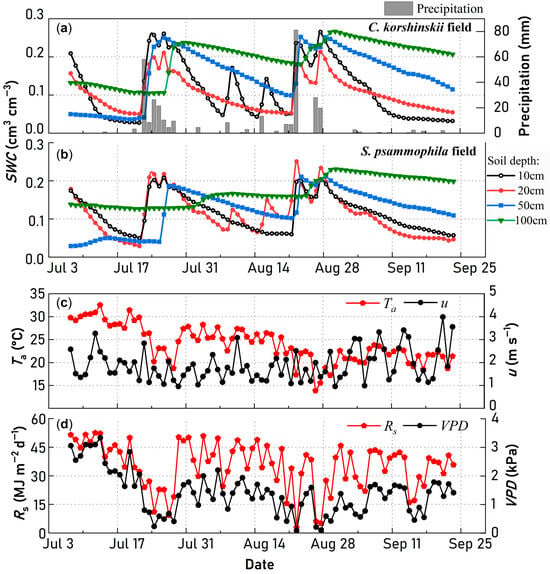

During the observation period, rainfall occurred on 35 days (Figure 2a), comprising 21 discrete rainfall events totaling 331.0 mm. This accounted for 51% of the annual rainfall and exceeded the regional mean annual precipitation, confirming a wet year. Most rainfall events were of low intensity: approximately 62% recorded less than 10 mm; six events ranged between 10 and 50 mm; and two exceeded 50 mm.

Figure 2.

Environmental drivers affecting canopy transpiration: Daily dynamics of key meteorological variables and soil water content. (a) Precipitation and SWC (cm3 cm−3) profiles in the C. korshinskii stand. (b) SWC profiles in the S. psammophila stand. (c) Daily patterns of air temperature (Ta, °C) and wind speed (u, m s−1). (d) Daily patterns of solar radiation (Rs, MJ m−2 d−1) and vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa).

Rainfall induced marked fluctuations in SWC across the measured depths, particularly during high-intensity or prolonged events (Figure 2a,b). The upper soil layers exhibited frequent wetting–drying cycles due to their high sensitivity to rainfall, whereas deeper layers responded more slowly and primarily to heavier rainfall events. Temporal variations in key meteorological variables—including daily mean Rs, Ta, u, and VPD—are shown in Figure 2c,d. These variables displayed pronounced day-to-day fluctuations characteristic of the region’s monsoonal climate.

3.2. Canopy Transpiration, Stomatal Conductance, and Decoupling Coefficients

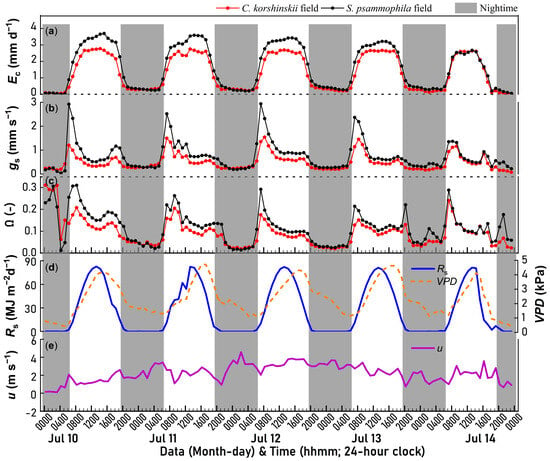

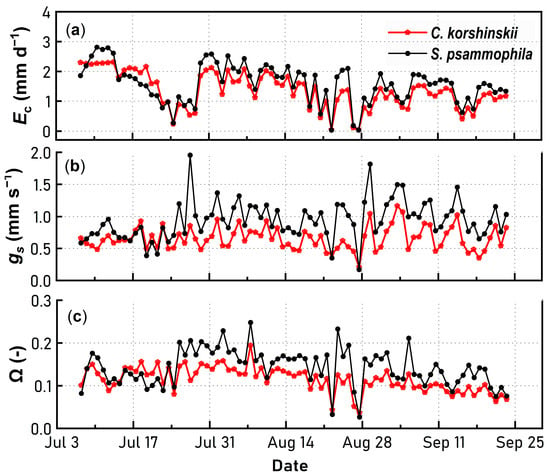

Canopy transpiration exhibited distinct diurnal cycles, with a consistent single-peak pattern in both shrub stands (Figure 3a,b). Under clear-sky conditions, Ec commenced between 05:00 and 06:00 in response to rising Rs, increased rapidly until approximately 09:30, then rose more gradually to a midday maximum around 14:00 before declining steadily to near zero by midnight. The diurnal dynamics of Ec were strongly correlated with Rs and VPD (Figure 3a,d).

Figure 3.

Intra-daily patterns of water use and microclimate: A five-day series of clear-sky conditions during the study period. (a) Canopy transpiration (Ec, mm h−1). (b) Stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1). (c) Decoupling coefficient (Ω). Concurrent microclimatological data for (d) solar radiation (Rs, MJ m−2 d−1) and vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa), and (e) wind speed (u, m s−1).

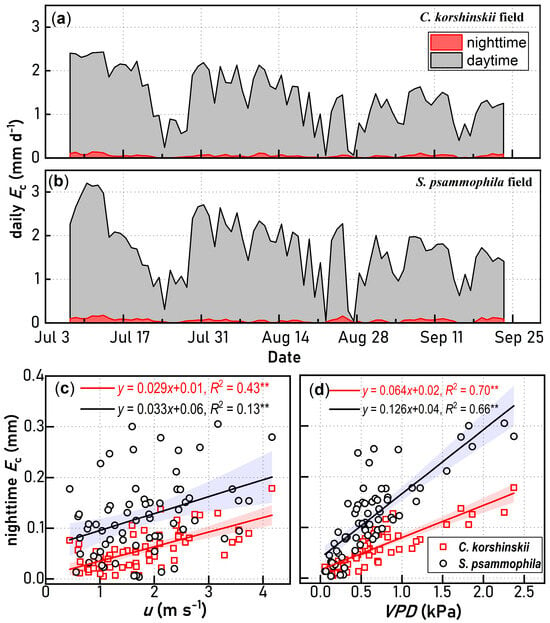

Although transpiration was predominantly daytime-driven, measurable nocturnal Ec was observed in both species. In C. korshinskii, nocturnal Ec reached a maximum of 0.14 mm d−1, totaling 3.99 mm during the observation period, whereas daytime Ec peaked at 2.32 mm d−1 and accumulated 107.39 mm (Figure 4a). In S. psammophila, nocturnal Ec attained 0.18 mm d−1 and summed to 4.65 mm, while daytime Ec reached 3.10 mm d−1 and totaled 129.51 mm (Figure 4b). Consequently, nocturnal Ec accounted for 3.6% and 3.5% of daily totals in C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively. Although a few days showed nocturnal fractions exceeding 30% of daily totals, these values generally remained below 10%.

Figure 4.

Diurnal and nocturnal transpiration patterns and their drivers: Partitioning of daily canopy water loss and analysis of nighttime controls. Daytime (06:00–19:00) and nocturnal (20:00–05:00) canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1) for (a) C. korshinskii and (b) S. psammophila, respectively. Relationships between nocturnal Ec and (c) wind speed (u, m s−1) and (d) vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa), with the shaded area representing the 95% confidence intervals of the regression fits. Significance levels: ** p < 0.01.

Nocturnal Ec in both species was closely associated with VPD (R2 = 0.70 for C. korshinskii and R2 = 0.66 for S. psammophila), whereas the influence of wind speed was comparatively minor, being moderate in C. korshinskii (R2 = 0.42) and negligible in S. psammophila (R2 = 0.13) (Figure 4c,d). These results indicate that nighttime water loss in both species is essentially a passive consequence of residual atmospheric demand, modulated by aerodynamic conditions rather than by active physiological regulation.

Stomatal conductance showed clear diurnal variation in both shrub species (Figure 3b). gs began to increase at around 06:00, reaching a sharp peak between 07:00 and 08:00, coinciding with the period of the most rapid rise in Ec. Thereafter, gs declined quickly by noon and remained low and stable until 19:00. In contrast to the broad midday peak of Ec, gs displayed a narrow, transient maximum, reflecting rapid stomatal closure once atmospheric demand intensified. The onset of gs occurred slightly earlier in S. psammophila than in C. korshinskii, likely reflecting its quicker stomatal response to increasing Rs. The maximum gs values were 1.94 mm s−1 in C. korshinskii and 3.62 mm s−1 in S. psammophila, with corresponding daily means of 0.65 and 1.04 mm s−1, respectively.

The decoupling coefficient exhibited a diurnal pattern broadly similar to that of gs, though with greater temporal fluctuations and stronger responses to environmental changes (Figure 3c). Hourly Ω values reached up to 0.54 in C. korshinskii and 0.70 in S. psammophila, typically shortly after rainfall or shallow soil-water recharge in the early morning. Mean daily Ω were 0.11 in C. korshinskii and 0.15 in S. psammophila, respectively. These consistently low Ω values indicate that the canopies of both species were strongly coupled to the atmosphere, meaning that transpiration was primarily controlled by stomatal and boundary-layer conductance and remained highly responsive to VPD variations (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Stand-level water use dynamics during the growing season: Daily variations in key physiological variables for Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila. (a) Canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1). (b) Stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1). (c) Decoupling coefficient (Ω, -).

3.3. Atmospheric Control of Canopy Transpiration and Stomatal Conductance

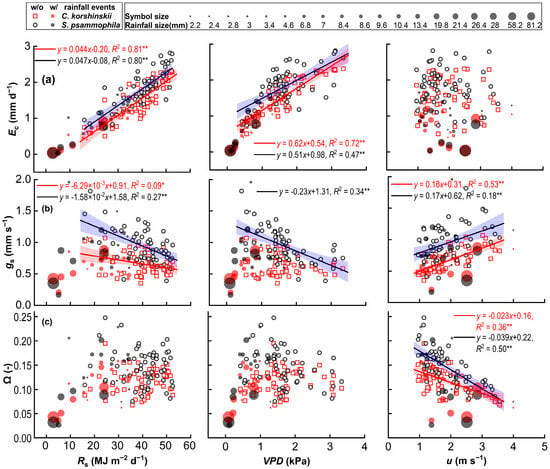

During the observation period, daily Ec showed significant positive correlations with both Rs and VPD in two shrub stands. A strong linear relationship was observed between Ec and Rs, explaining 81% and 80% of the variance in Ec in C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively. Moreover, while Ec exhibited a robust linear response to VPD in C. korshinskii, accounting for 72% of the variance, it explained only 47% of the variance in S. psammophila (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Quantifying environmental controls on shrub water use: Functional responses of physiological variables to key micrometeorological drivers. (a) Canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1). (b) Stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1). (c) Decoupling coefficient (Ω, -). Relationships are shown for both Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila in response to solar radiation (Rs, MJ m−2 d−1), vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa), and wind speed (u, m s−1). The shaded area represents the 95% confidence intervals of the regression fits. Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Distinct patterns in stomatal conductance were found. In S. psammophila, daily gs was significantly and negatively correlated with both Rs and VPD, with linear regressions explaining 27% and 34% of its daily variation, respectively. In contrast, in C. korshinskii, daily gs showed a significant negative correlation with Rs but no significant relationship with VPD (Figure 6b). These contrasting responses reflect species-specific differences in stomatal sensitivity to atmospheric demand.

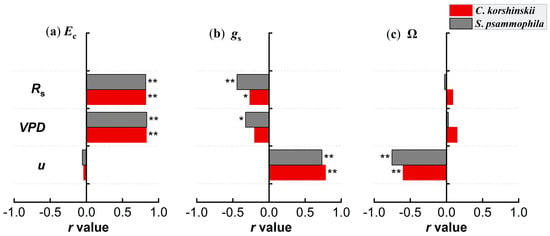

Wind speed was not significantly correlated with Ec in either species, but it was significantly positively correlated with gs and strongly negatively correlated with Ω (Figure 6c). Partial correlation analysis, performed while controlling for SWC at multiple depths, confirmed these findings (Figure 7). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that atmospheric drivers—particularly Rs, VPD, and u—were the dominant factors influencing Ec and gs, and thereby strongly regulated the degree of canopy–atmosphere coupling in both shrub species.

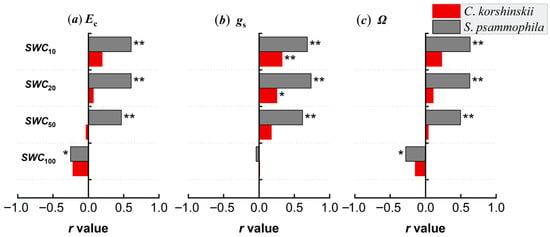

Figure 7.

Isolating the dominant meteorological drivers: Partial correlation analysis of physiological responses to microclimate while controlling for soil water content (SWC, cm3 cm−3) variation. (a) Canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1). (b) Stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1). (c) Decoupling coefficient (Ω, -). Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01. Meteorological variables include solar radiation (Rs, MJ m−2 d−1), vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa), and wind speed (u, m s−1), with SWC at multiple depths as the control variable.

3.4. SWC and Rainfall Impact on Canopy Transpiration and Stomatal Conductance

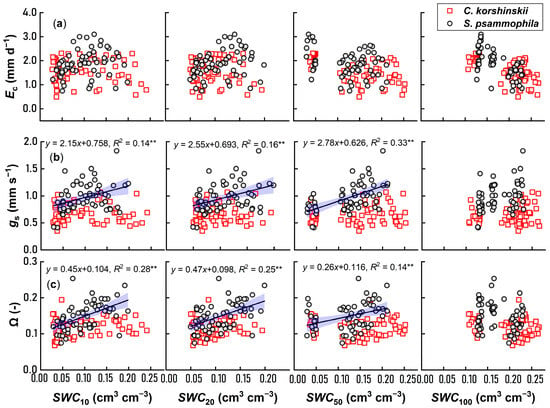

In the C. korshinskii stand, daily Ec showed no significant correlations with SWC at any measured depths, nor did SWC significantly affect gs or Ω. In contrast, in S. psammophila, Ec was not significantly correlated with SWC, whereas gs and Ω exhibited clear, significant positive correlations with SWC at depths of 10, 20, and 50 cm. Linear regression indicated that SWC at these depths accounted for 14%, 16%, and 33% of the variation in gs and 28%, 25%, and 14% of the variation in Ω, respectively (Figure 8). After controlling for meteorological variables, partial correlations confirmed significant positive relationships between Ec, gs, and Ω and shallow-layer SWC at 10, 20, and 50 cm in S. psammophila. In contrast, correlations in C. korshinskii remained weak, with significance only at 10 and 20 cm (Figure 9). The negative correlation between SWC at 100 cm and both Ec and Ω was mainly attributed to the inverse relationship between SWC and VPD.

Figure 8.

Soil water regulation of shrub water use: Responses of key physiological variables to soil water content (SWC) across vertical profiles. (a) Canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1). (b) Stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1). (c) Decoupling coefficient (Ω, -). Relationships are shown for Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila against SWC (cm3 cm−3) at 10, 20, 50, and 100 cm depths. The shaded area represents the 95% confidence intervals of the regression fits. Significance levels: ** p < 0.01.

Figure 9.

Isolating soil water content (SWC) influence on shrub physiology: Partial correlation analysis of water use parameters with SWC profiles while controlling for micrometeorological conditions. (a) Canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1). (b) Stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1). (c) Decoupling coefficient (Ω, -). Analysis reveals relationships with SWC (cm3 cm−3) at 10-, 20-, 50-, and 100 cm depths, controlling for solar radiation (Rs, MJ m−2 d−1), vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa), and wind speed (u, m s−1). Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

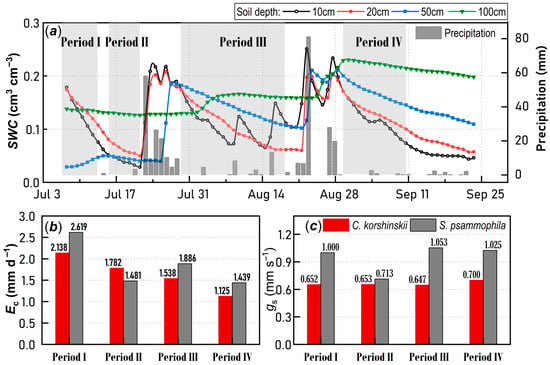

Rainfall events induced distinct soil water regimes (Figure 10a). During shallow soil drying (Period I → II), SWC decreased by 0.08 cm3 cm−3, resulting in Ec declines of 16.7% in C. korshinskii and 43.5% in S. psammophila. In contrast, gs decreased notably only in S. psammophila. Shallow-soil recharge (Period II → III) caused Ec and gs to increase markedly in S. psammophila (+27.4% and +47.7%), but showed little effect in C. korshinskii. During deep-soil recharge (Period IV), Ec decreased comparably in both species (−26.9% versus −23.7%), with minimal variation in gs.

Figure 10.

Hydrological periods and shrub water use: Divergent physiological responses to contrasting soil water dynamics. (a) Duration of four characteristic soil water content (SWC, cm3 cm−3) periods: Period I (initial), Period II (shallow depletion), Period III (shallow recharge), and Period IV (deep recharge). Mean values of (b) canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1) and (c) stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1) for Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila across these four periods.

Overall, S. psammophila responded sensitively to shallow SWC fluctuations, exhibiting substantial variability in both Ec and gs. In contrast, C. korshinskii maintained relatively stable Ec and gs, reflecting a conservative, atmosphere-driven water-use strategy buffered by deep soil water.

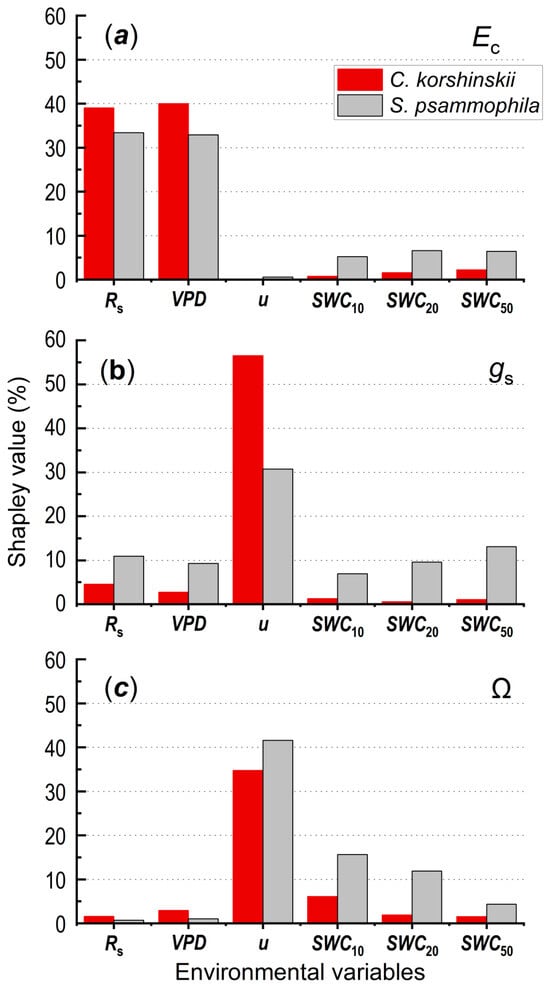

3.5. Relative Importance of Meteorological Conditions and SWC in Regulating Shrub Water Use

Relative importance analyses revealed distinct patterns in the environmental control of Ec, gs, and Ω between the two shrub species (Figure 11). For Ec, key meteorological factors—VPD, Rs, and u—collectively explained 79.2% of the daily variation in C. korshinskii and 66.9% in S. psammophila. Among these variables, VPD and Rs were the dominant contributors, whereas wind speed had only a minor effect in both species. In contrast, shallow-layer SWC at 10, 20, and 50 cm accounted for only 4.5% of the Ec variation in C. korshinskii, but contributed up to 18.2% in S. psammophila, indicating a stronger dependence on SWC in the latter.

Figure 11.

Quantifying environmental drivers of shrub water use: Relative importance of meteorological factors and soil water in explaining physiological variation. (a) Canopy transpiration (Ec, mm d−1). (b) Stomatal conductance (gs, mm s−1). (c) Decoupling coefficient (Ω, -). Shapley values from regression-based relative-importance analysis show contributions of solar radiation (Rs, MJ m−2 d−1), vapor pressure deficit (VPD, kPa), wind speed (u, m s−1), and soil water content (SWC, cm3 cm−3) at depths of 10, 20, and 50 cm for Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila.

For gs, meteorological drivers collectively explained 63.8% and 50.9% of the variance in C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively. Wind speed emerged as the most influential variable, accounting for 56.5% and 30.7% of the variance in the two species, respectively. Shallow-layer SWC accounted for only 3.0% of the variation in C. korshinskii but reached 29.6% in S. psammophila, underscoring the latter’s sensitivity to short-term fluctuations in shallow-layer soil water.

Similarly, meteorological factors accounted for 39.2% and 43.3% of the Ω variation in C. korshinskii and S. psammophila, respectively. Wind speed again exerted the most decisive influence, accounting for 34.7% and 41.6% in the two species, whereas shallow SWC accounted for 9.5% and 31.8%, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Hierarchy of Atmospheric and Soil-Water Controls on Xerophytic Shrub Water Use in a Wet Year

Our wet-season observations revealed a distinct hierarchy among environmental drivers regulating Ec and gs in both xerophytic shrubs. The results clearly demonstrated that atmospheric condition was the dominant control, with meteorological variables collectively explaining most of the daily variance in Ec (~79% for C. korshinskii and ~67% for S. psammophila) and gs (~64% and ~51%, respectively). This dominance reflects the strong canopy–atmosphere coupling observed in both species (Ω = 0.11–0.15), under which transpiration is primarily governed by stomatal conductance and closely tracks VPD [37,38]. Overall, the influence of Rs on Ec, gs, and Ω paralleled that of VPD, a pattern driven primarily by the strong daytime co-variation between these two variables [39,40].

Wind speed further modulated these interactions. Although wind speed showed no direct effect on daily Ec, it correlated positively with gs and negatively with Ω, consistent with wind thinning the leaf boundary layer and enhancing aerodynamic conductance. In such strongly coupled, low-stature canopies, wind acts not by supplying additional energy for evaporation, but by amplifying stomatal responsiveness to VPD [41,42]. This implies that: (1) models should explicitly incorporate aerodynamic conductance so that wind effects can be represented mechanistically without spuriously inflating Ec (i.e., explicitly parameterize wind-dependent leaf boundary-layer conductance gbl and aerodynamic conductance ga in the land-surface scheme); and (2) because gs underpins CO2 uptake, wind—via its effects on gbl/ga and leaf temperature—can modulate photosynthesis and canopy carbon assimilation, and therefore should be considered in photosynthesis/carbon-uptake calculations rather than treated as negligible [43,44].

A small yet consistent nocturnal transpiration (~3.5–3.6% of daily totals) was also observed in both species. Nocturnal Ec was tightly linked to nighttime VPD, with minor wind influence. Given Ω near zero at night, this water loss is best explained by incomplete stomatal closure under residual VPD—a common, passively driven phenomenon in woody plants [45,46]. Although minor nighttime conductance may contribute to maintaining hydraulic continuity and root-to-shoot nutrient mass flow [46], facilitating O2 supply/CO2 efflux in living tissues [47], or, under humid nights, enabling opportunistic foliar nutrient uptake [48], our data support a non-regulated, residual flux rather than an active physiological strategy [47]. Ignoring this flux in models would result in a slight underestimation of total water loss and a misrepresentation of early-morning water status.

While soil water ultimately supplies the water for transpiration, its influence was secondary during this wet season. Shallow-layer SWC (0–50 cm) explained only a small fraction of the variance in Ec (4.5% for C. korshinskii, 18.2% for S. psammophila), gs (3.0% and 29.6%), and Ω (9.5% and 31.8%, respectively). Notably, S. psammophila showed clear positive responses of gs and Ω to shallow SWC, whereas C. korshinskii remained largely insensitive. This pattern indicates depth-partitioned water use: S. psammophila depends more on transient near-surface moisture, while C. korshinskii buffers short-term surface drying by exploiting deeper reserves, consistent with results from stable-isotope tracing of hydrogen and oxygen [18,21,22]. Because SWC was measured only to 1.0 m, the deeper uptake of C. korshinskii is inferred from its weak shallow-SWC dependence and the presence of fine roots beyond 2.6 m (Figure 12). Confirming this mechanism requires further deeper SWC observations.

Figure 12.

Belowground rooting strategies underpinning divergent water use: Histograms of fine-root length density (RLD, km m−3) distribution throughout the 300 cm soil profile for Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila.

4.2. What the Wet-Season Data Reveal: Isohydric Versus Anisohydric Behavior as a Conditional Spectrum

Most previous studies have portrayed a distinct hydraulic divergence between the two species: C. korshinskii is commonly characterized as an isohydric, atmosphere-dominated species exhibiting limited sensitivity to soil water availability [15,49], and S. psammophila is generally described as anisohydric, with pronounced physiological responses to fluctuations in SWC [14,15,21,22]. The wet-season data only partly confirm this expectation. Both species indeed operated under strong canopy–atmosphere coupling and VPD control, but their water-use behaviors diverged from textbook classifications.

S. psammophila showed pronounced stomatal sensitivity to shallow SWC, actively closing stomata during shallow drying and reopening after rewetting—features typically associated with isohydric regulation. This likely helps prevent xylem cavitation under short-term stress. In contrast, C. korshinskii maintained remarkably steady Ec and gs, exhibiting stability reminiscent of anisohydric behavior. However, this apparent stability likely reflects hydraulic buffering via deep rooting rather than a tolerance of low water potential.

Thus, the results indicate that isohydric and anisohydric behaviors form a context-dependent continuum rather than fixed species traits. Under wet-year conditions, ample deep soil water allows C. korshinskii to maintain steady transpiration, whereas S. psammophila, which is dependent on dynamic shallow water, exhibits tighter stomatal control. Conversely, during multi-month droughts—when deep stores are depleted—C. korshinskii would likely display stronger isohydric regulation, and S. psammophila may incur greater hydraulic risk to sustain gas exchange. Consequently, the data support a plastic, resource-context-dependent interpretation of water-use strategy rather than a rigid dichotomy.

4.3. Implications for Ecohydrological Modeling and Revegetation Management

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for enhancing ecohydrological models and guiding vegetation management in semi-arid regions. From a modeling perspective, our results emphasize that transpiration schemes should adopt a VPD-centric formulation, particularly under conditions of strong canopy–atmosphere coupling. Rs can be treated as a correlated covariate rather than an independent driver once its covariance with VPD is accounted for. Furthermore, aerodynamic conductance, i.e., ga, should be explicitly represented in model structures so that wind effects can enhance gs and reduce Ω without artificially inflating Ec.

Differences in rooting depth and water uptake strategy between C. korshinskii and S. psammophila also have direct implications for model parameterization. Models should assign deeper, more buffered water uptake zones to C. korshinskii and shallower, more responsive zones to S. psammophila, reflecting their respective hydraulic architectures. For S. psammophila, SWC should constrain gs more directly than Ec, as stomatal regulation is the primary mechanism mediating its response to fluctuations in shallow soil water. In addition, a small, VPD-driven nocturnal conductance should be incorporated into model routines to capture the observed 3–4% nocturnal Ec and to improve the simulation of early-morning canopy water status.

From a management perspective, our findings indicate that C. korshinskii exhibits a conservative and stable water-use pattern with minimal dependence on shallow SWC. Its ability to tap deeper soil-water reserves supports sustained transpiration during dry periods while minimizing the risk of rapid desiccation of the surface layer. Together, these traits reflect an appropriate safety–efficiency trade-off in hydraulic functioning [16,50], making C. korshinskii particularly well suited for revegetation in environments with limited water availability and long intervals between rainfall events. In contrast, S. psammophila responds rapidly to shallow soil-water recharge and shows substantial declines in gs during shallow drying. This behavior enables it to utilize frequent, small rainfall events efficiently but may increase vulnerability during prolonged droughts when near-surface moisture is depleted. Accordingly, C. korshinskii is better suited to harsh, water-deficient environments, whereas S. psammophila may be more appropriate for zones with shallower water tables or regions with intermittent rainfall. Mixed plantations that combine both species could take advantage of their complementary water-use strategies—C. korshinskii stabilizing water consumption during dry spells and S. psammophila exploiting rainfall pulses. To ensure long-term sustainability, revegetation design should match total biomass to the site’s soil-water carrying capacity and remain flexible to interannual climate variability [51,52]. It is essential to note that the present study does not evaluate survival under extreme drought; therefore, its implications for the most arid desert ecosystems should be interpreted with caution.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

Several factors limit the scope of inference from this study and highlight directions for future work. First, the temporal scope was restricted to a single wet season of a wet year, which constrains our ability to generalize the observed water-use patterns to drier years or multi-year drought conditions. Second, the SWC profile was monitored only to a depth of 1.0 m; consequently, the inferred deep-water uptake for C. korshinskii remains indirect and requires confirmation from deeper soil water. Third, no concurrent physiological measurements—such as leaf or sapwood water potential, hydraulic vulnerability curves, or xylem embolism dynamics—were available to directly link the observed patterns of gs and Ec to underlying hydraulic constraints. Finally, the two stands differed in age, canopy structure, and microsite hydrology, which may have influenced both soil water distribution and absolute flux rates.

Future research should aim to address these limitations by conducting multi-year, multi-season monitoring campaigns that encompass both dry and wet periods, thereby capturing the full range of environmental variability in the Loess Plateau region. Integrating deeper SWC monitoring (≥2–3 m) with stable isotope tracing and measurements of xylem water potential would enable direct quantification of the depth of root water uptake and hydraulic risk under contrasting climatic conditions. Paired, co-located experimental stands with matched stand age, leaf area index, and soil properties would provide a more robust comparison of species-level responses. Finally, explicit measurements of ga and leaf boundary-layer properties would help clarify the mechanistic pathways by which wind modulates stomatal and canopy-coupling dynamics.

Despite these limitations, this study provides mechanistic evidence for how atmospheric demand and soil-water availability jointly, yet hierarchically, regulate canopy transpiration, stomatal behavior, and canopy–atmosphere coupling in cultivated xerophytic shrubs during an anomalously wet year on the northern Loess Plateau. By combining continuous sap-flow monitoring with multi-depth soil-water and micrometeorological observations, the work advances a process-based understanding of shrub water-use regulation under strong canopy–atmosphere coupling—an environmental condition seldom examined in previous dryland studies. The contrasting responses of C. korshinskii and S. psammophila extend the anisohydric–isohydric framework into a context-dependent continuum shaped by depth-partitioned water-use strategies. These insights enhance the parameterization of shrub water use in ecohydrological models and provide practical guidance for water-use management, species selection, and nursery practices in semi-arid landscapes experiencing ongoing warming–wetting climatic shifts.

5. Conclusions

This study quantified Ec, gs, and Ω for C. korshinskii and S. psammophila during the wet season of a climatically wet year on the northern Loess Plateau, allowing explicit evaluation of the proposed hypotheses.

First, the results demonstrated a clear hierarchy of environmental controls, with atmospheric factors strongly regulating Ec and gs. Meteorological variables explained most of the daily variation in Ec (~79% and ~67%) and gs (~64% and ~51%). Wind speed increased gs and reduced Ω without enhancing Ec, reinforcing the primacy of atmospheric regulation. A small but consistent nocturnal transpiration rate (≈3–4%) was also driven primarily by nighttime VPD. Second, both shrubs exhibited strong and persistent canopy–atmosphere coupling. Ω remained consistently low (≈0.11–0.15) on daily scales throughout the wet season, even under abundant soil water, indicating that coupling strength was governed primarily by stomatal and aerodynamic conductance rather than by SWC. The occurrence of nocturnal Ec further highlighted sustained atmospheric control. Third, the species showed contrasting sensitivities to soil-water availability that reflect depth-partitioned water-use strategies. Shallow SWC contributed modestly to variation in C. korshinskii, whereas it strongly influenced S. psammophila, which depends on shallow moisture pulses. C. korshinskii maintained stable water use through deeper soil water uptake. These patterns reflect context-dependent shifts along the anisohydric–isohydric continuum rather than fixed species-level traits, highlighting distinct ecological niches.

The novelty of this work lies in its mechanistic assessment of canopy water loss, stomatal behavior, and canopy–atmosphere coupling under wet climatic conditions—an aspect rarely examined in cultivated xerophytic shrubs. By quantifying the relative roles of atmospheric and soil-water controls and identifying species-specific hydraulic strategies, this study advances understanding of shrub water-use physiology. These insights are particularly relevant in the context of the ongoing warming–wetting trend on the northern Loess Plateau and support improved parameterization of shrub water use in ecohydrological models, better water-use management, and informed species selection for landscape restoration in semi-arid regions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae12010013/s1, Figure S1: Soil images and particle-size composition (0–100 cm) in the two experimental stands. Soil particles were classified into sand (2–0.05 mm), silt (0.05–0.002 mm), and clay (<0.002 mm) following the USDA texture classification system. Panels show: (a) soil profile in the C. korshinskii stand; (b) soil profile in the S. psammophila stand; (c) particle-size composition in the C. korshinskii stand; and (d) particle-size composition in the S. psammophila stand; Figure S2: Distribution of stem numbers across stem diameter classes in the Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila stands. Stem diameter classes were grouped at 2.5 mm intervals (0–2.5 mm, 2.5–5 mm, …, ≥20 mm). Stem counts were determined from complete stand surveys in each experimental plot to characterize the structural composition of both shrub communities.

Author Contributions

Methodology, S.W. and J.F.; Validation, S.W.; Investigation, S.W.; Writing—original draft, S.W.; Writing—review and editing, N.Y., J.F. and C.Y.; Funding acquisition, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [NSFC 42107321], Scientific Research Project of Science and Technology for Forestry in Chongqing [ZDXM2024-1], and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [SWU-KT 22062], and the APC was funded by [NSFC 42107321].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Scott B. Jones of Utah State University for his thoughtful review and editing of the manuscript. We are also grateful to the editors and the three anonymous reviewers for their diligent work and valuable comments, which significantly improved the manuscript’s quality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Hoover, D.L.; Bestelmeyer, B.; Grimm, N.B.; Huxman, T.E.; Reed, S.C.; Sala, O.; Seastedt, T.R.; Wilmer, H.; Ferrenberg, S. Traversing the Wasteland: A Framework for Assessing Ecological Threats to Drylands. Bioscience 2020, 70, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, A.; Murali, G.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Roll, U. Global evaluation of current and future threats to drylands and their vertebrate biodiversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.X.; Wang, Y.J.; Yao, Y.; Wang, C.X. Land cover change in global drylands: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Fan, J.; Zhang, S.G.; Zhao, X.; Luo, Z.B.; Zhou, G. Changes and driving factors of soil water in mixed-species plantations and different precipitation scenarios on the Loess Plateau of China. Catena 2024, 246, 108370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Park, T.; Wang, X.H.; Piao, S.L.; Xu, B.D.; Chaturvedi, R.K.; Fuchs, R.; Brovkin, V.; Ciais, P.; Fensholt, R.; et al. China and India lead in greening of the world through land-use management. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.T.; He, H.L.; Zhang, M.Y.; Deng, J.M.; Ren, X.L.; Lv, Y.; Liu, W.H.; Lin, Z.N.; Dong, S.Y. Grain for Green Project dominates greening in afforested areas rather than that in grass revegetation areas of the Loess Plateau, China-using Deep Crossing LSTM Age network. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 084068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, F.Y.; Yang, T.R.; Chao, H.Y.; Ma, X.H.; Wu, J.J.; Yang, Q.; Ren, G.P.; Song, L.; Wang, Q.; Qi, L.W.; et al. Genomic insights into drought adaptation of the forage shrub Caragana korshinskii (Fabaceae) widely planted in drylands. Plant J. 2025, 121, e17255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; An, J.X.; Shao, Y.M.; Gao, G.Y. Responses of leaf-level physiological traits and water use characteristics to drought of a xerophytic shrub in northern China. J. Hydrol. 2025, 658, 133204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.X.; Shao, M.A.; Zhu, Y.J.; Luo, Y. Soil moisture decline due to afforestation across the Loess Plateau, China. J. Hydrol. 2017, 546, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.L.; Yang, D.W.; Yang, Y.T.; Piao, S.L.; Yang, H.B.; Lei, H.M.; Fu, B.J. Excessive Afforestation and Soil Drying on China’s Loess Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2018, 123, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.X.; Shao, M.A.; Zhang, C.C.; Zhao, C.L. Regional temporal persistence of dried soil layer along south-north transect of the Loess Plateau, China. J. Hydrol. 2015, 528, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.H.; Chen, Z.X.; Shen, Y.Y.; Yang, X.L. Thinning promoted the rejuvenation and highly efficient use of soil water for degraded Caragana korshinskii plantation in semiarid loessal regions. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Fan, X.G.; Li, T.C.; Zhang, J.L.; Jia, Y.H. Estimation and Restoration of Dried Soil Layers in a Slope-Gully Unit of the Chinese Loess Plateau. Hydrol. Process. 2024, 38, e15318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Chen, W.Y.; Chen, J.C.; Shi, H. Vulnerability to drought-induced cavitation in shoots of two typical shrubs in the southern Mu Us Sandy Land, China. J. Arid Land 2016, 8, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Chen, W.Y.; Chen, J.C.; Shi, H. Contrasting hydraulic strategies in Salix psammophila and Caragana korshinskii in the southern Mu Us Desert, China. Ecol. Res. 2016, 31, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.Q.; Nie, Z.F.; Turner, N.C.; Li, F.M.; Gao, T.P.; Fang, X.W.; Scoffoni, C. Combined high leaf hydraulic safety and efficiency provides drought tolerance in Caragana species adapted to low mean annual precipitation. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.Y.; Xie, L.F.; Ren, J.J.; Zhang, T.X.; Cui, J.H.; Bao, Z.L.T.; Zhou, W.F.; Bai, J.; Gong, C.M. CkREV regulates xylem vessel development in Caragana korshinskii and enhances drought response. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 982853. [Google Scholar]

- Che, C.W.; Zhang, M.J.; Yang, W.M.; Wang, S.J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.L. Dissimilarity in radial growth and response to drought of Korshinsk peashrub (Caragana korshinskii Kom.) under different management practices in the western Loess Plateau. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1357472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Chen, J.C.; Ai, S.S.; Shi, H. Responses of leaf water potential and gas exchange to the precipitation manipulation in two shrubs on the Chinese Loess Plateau. J. Arid Land 2020, 12, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Dang, X.H.; Meng, Z.J.; Liu, Y.; Lou, J.L.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X. Effects of Drought on the Water Use Strategies of Pure and Mixed Shrubs in the Mu Us Sandy Land. Plants 2024, 13, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Knighton, J.; Evaristo, J.; Wassen, M. Contrasting adaptive strategies by Caragana korshinskii and Salix psammophila in a semiarid revegetated ecosystem. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 300, 108323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chun, K.P.; Ziegler, A.D.; Evaristo, J. Dynamic hydrological niche segregation: How plants compete for water in a semi-arid ecosystem. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gao, G.Y.; Li, J.R.; Yuan, C.; Lu, Y.H.; Fu, B.J. Sap flow dynamics of xerophytic shrubs differ significantly among rainfall categories in the Loess Plateau of China. J. Hydrol. 2020, 585, 124815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, M.; Zha, T.S.; Jia, X.; Iqbal, S.; Qian, D.; Bourque, C.P.A.; Khan, A.; Tian, Y.; Bai, Y.J.; Liu, P.; et al. A multiple-temporal scale analysis of biophysical control of sap flow in Salix psammophila growing in a semiarid shrubland ecosystem of northwest China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 288, 107985. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Q.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, X. Precipitation Changes and Future Trend Predictions in Typical Basin of the Loess Plateau, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.Z.; Wang, W.G.; Wei, J.; Forzieri, G.; Fetzer, I.; Wang-Erlandsson, L. Revegetation Impacts on Moisture Recycling and Precipitation Trends in the Chinese Loess Plateau. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2024WR038199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Ge, J.M.; Wang, Q.M.; Yong, C.X.; You, W. New design of external heat-ratio method for measuring low and reverse rates of sap flow in thin stems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 419, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, P.G.; Mcnaughton, K.G. Stomatal Control of Transpiration: Scaling Up from Leaf to Region. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1986, 15, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.G. Using the FAO-56 dual crop coefficient method over an irrigated region as part of an evapotranspiration intercomparison study. J. Hydrol. 2000, 229, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, F.W. On the Computation of Saturation Vapor Pressure. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1967, 6, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusa, I.A.M.; Walker, R.R.; Lu, P. Evapotranspiration components from energy balance, sapflow and microlysimetry techniques for an irrigated vineyard in inland Australia. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 127, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration: Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fritschen, L.J.; Gay, L.W. Humidity and Moisture. In Environmental Instrumentation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 119–163. [Google Scholar]

- Brunt, D. Notes on radiation in the atmosphere. I. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1932, 58, 389–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, A.; Oliver, H. Penmans equation for estimating regional evaporation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1977, 103, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G. REF-ET: Reference Evapotranspiration Calculation Software for FAO and ASCE Standardized Equations, version 4.1; University of Idaho, Kimberly Research and Extension Center: Kimberly, ID, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Novick, K.A.; Ficklin, D.L.; Stoy, P.C.; Williams, C.A.; Bohrer, G.; Oishi, A.C.; Papuga, S.A.; Blanken, P.D.; Noormets, A.; Sulman, B.N.; et al. The increasing importance of atmospheric demand for ecosystem water and carbon fluxes. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flo, V.; Martinez-Vilalta, J.; Granda, V.; Mencuccini, M.; Poyatos, R. Vapour pressure deficit is the main driver of tree canopy conductance across biomes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 322, 109029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Y.; Wang, Y.K.; Liu, S.Y.; Wei, X.G.; Wang, X. Response of relative sap flow to meteorological factors under different soil moisture conditions in rainfed jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) plantations in semiarid Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 136, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Yan, H.; Xie, B.; Zhao, J.; Wang, N.; Wang, X. Canopy Transpiration and Stomatal Conductance Dynamics of Ulmus pumila L. and Caragana korshinskii Kom. Plantations on the Bashang Plateau, China. Forests 2022, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, M.; Conejero, W.; Vera, J.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M. Effects of Postharvest Water Deficits on the Physiological Behavior of Early-Maturing Nectarine Trees. Plants 2020, 9, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapira, O.; Hochberg, U.; Joseph, A.; McAdam, S.; Azoulay-Shemer, T.; Brodersen, C.R.; Holbrook, N.M.; Zait, Y. Wind speed affects the rate and kinetics of stomatal conductance. Plant J. 2024, 120, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Armas, R.; de Arellano, J.V.G.; Mangan, M.R.; Hartogensis, O.; de Boer, H. Impact of canopy environmental variables on the diurnal dynamics of water and carbon dioxide exchange at leaf and canopy level. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 2425–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, K.; van den Berg, T.; Zhang, J.; Moene, A.; Vialet-Chabrand, S. Beyond the boundary: A new road to improve photosynthesis via wind. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 5791–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Liang, C.; Xie, B.; Qin, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Cao, J. Nocturnal Water Use Partitioning and Its Environmental and Stomatal Control Mechanism in Caragana korshinskii Kom in a Semi-Arid Region of Northern China. Forests 2023, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Gu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, L. Nocturnal sap flow as compensation for water deficits: An implicit water-saving strategy used by mangroves in stressful environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Dios, V.; Chowdhury, F.; Granda, E.; Yao, Y.; Tissue, D. Assessing the potential functions of nocturnal stomatal conductance in C3 and C4 plants. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1696–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, C.; Chi, C.; Fernández, V.; Burkhardt, J. Nocturnal Transpiration May Be Associated with Foliar Nutrient Uptake. Plants 2023, 12, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.W.; Turner, N.C.; Palta, J.A.; Yu, M.X.; Gao, T.P.; Li, F.M. The distribution of four Caragana species is related to their differential responses to drought stress. Plant Ecol. 2014, 215, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Qi, S.; Tian, X.; Yao, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Fang, X. Higher Flower Hydraulic Safety, Drought Tolerance and Structural Resource Allocation Provide Drought Adaptation to Low Mean Annual Precipitation in Caragana Species. Plant Cell Environ. 2024. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Jia, X. Soil Drought and Water Carrying Capacity for Vegetation in the Critical Zone of the Loess Plateau: A Review. Vadose Zone J. 2018, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.S. Soil water carrying capacity for vegetation. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.