Variations in Nutritional Composition of Walnut Kernels Across Different Elevations in Chongqing Region, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Determination of Nutrient Content

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Total Nutritional Quality Evaluation of Walnuts in Chongqing

3.2. Changes in Nutrient Composition of Walnuts at Different Elevations

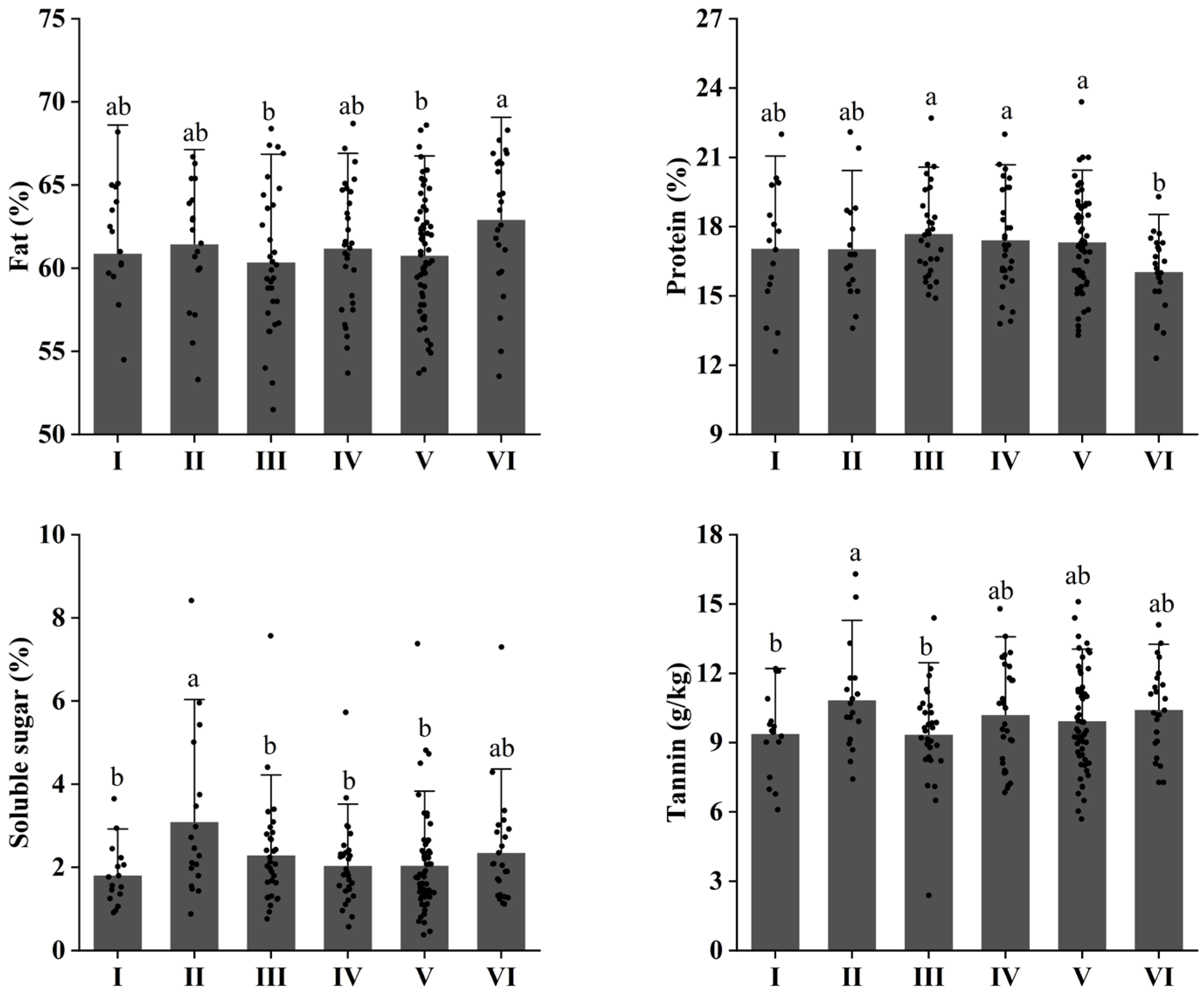

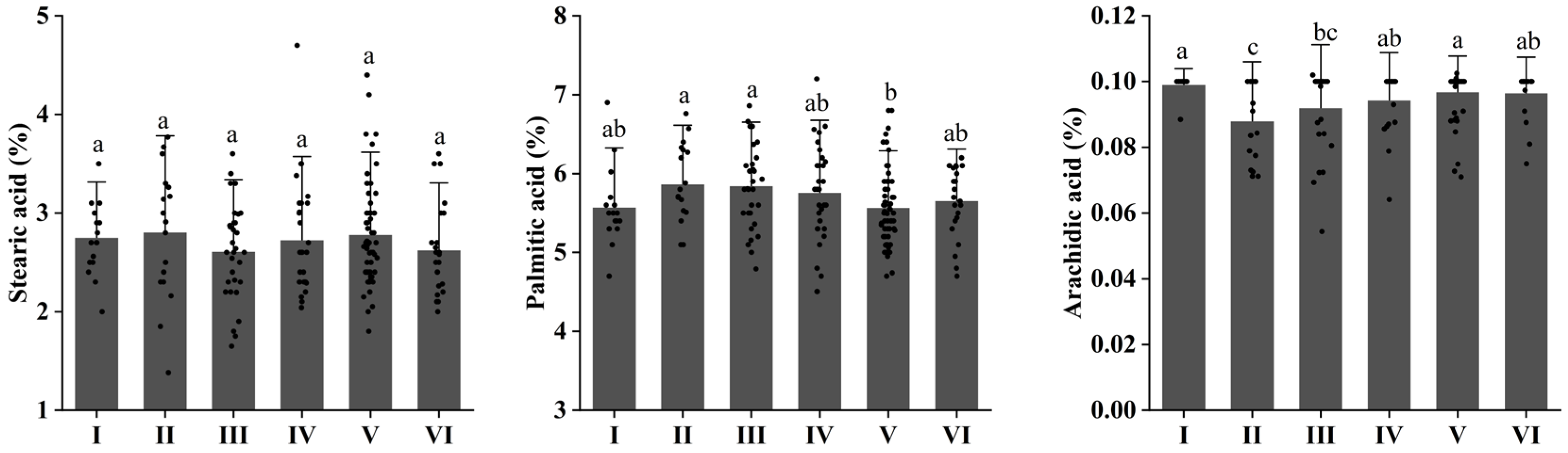

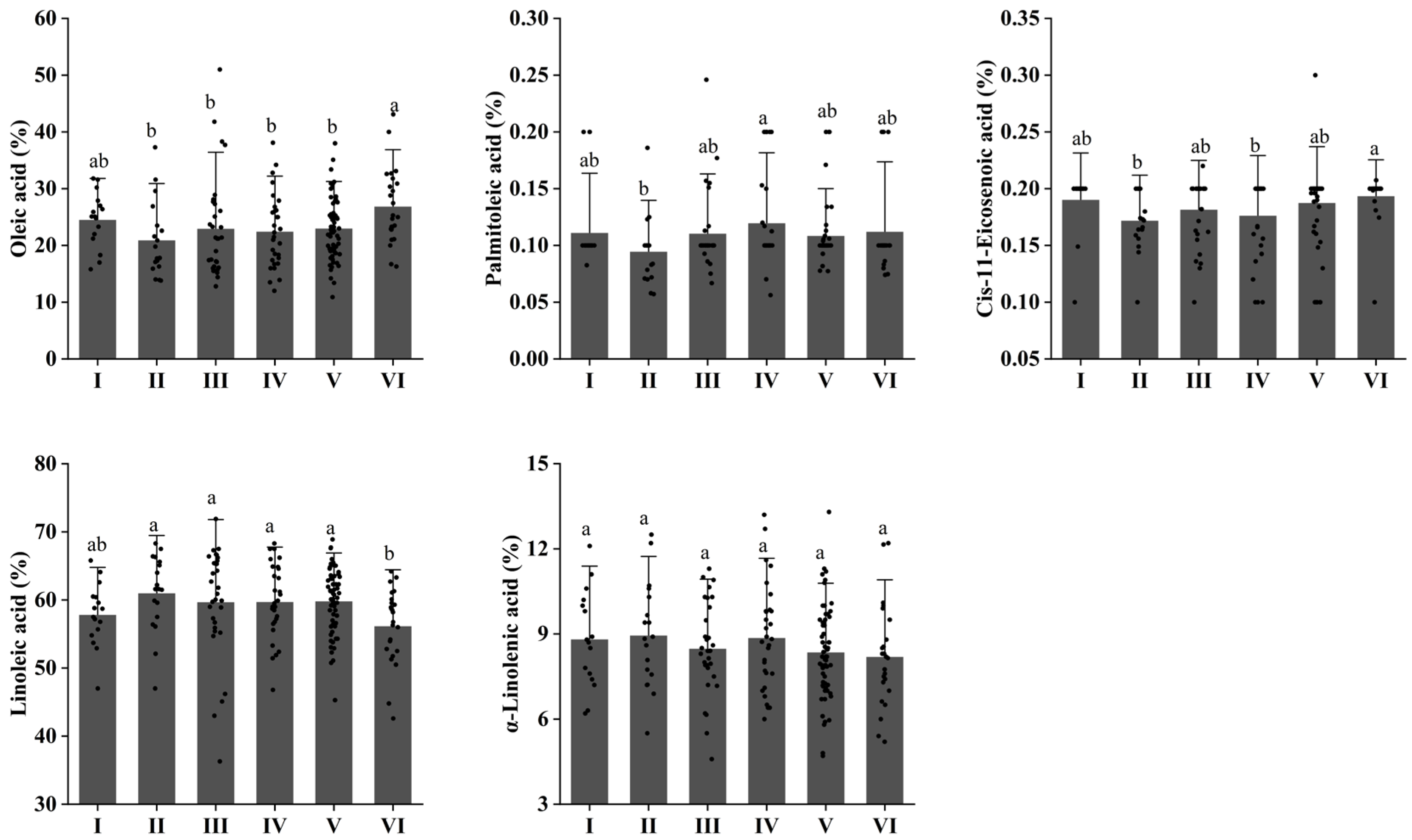

3.3. Changes in Saturated Fatty Acid (SFA) of Walnuts at Different Elevations

3.4. Changes in Monounsaturated Fatty Acids (MUFA) and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFA) of Walnuts at Different Elevations

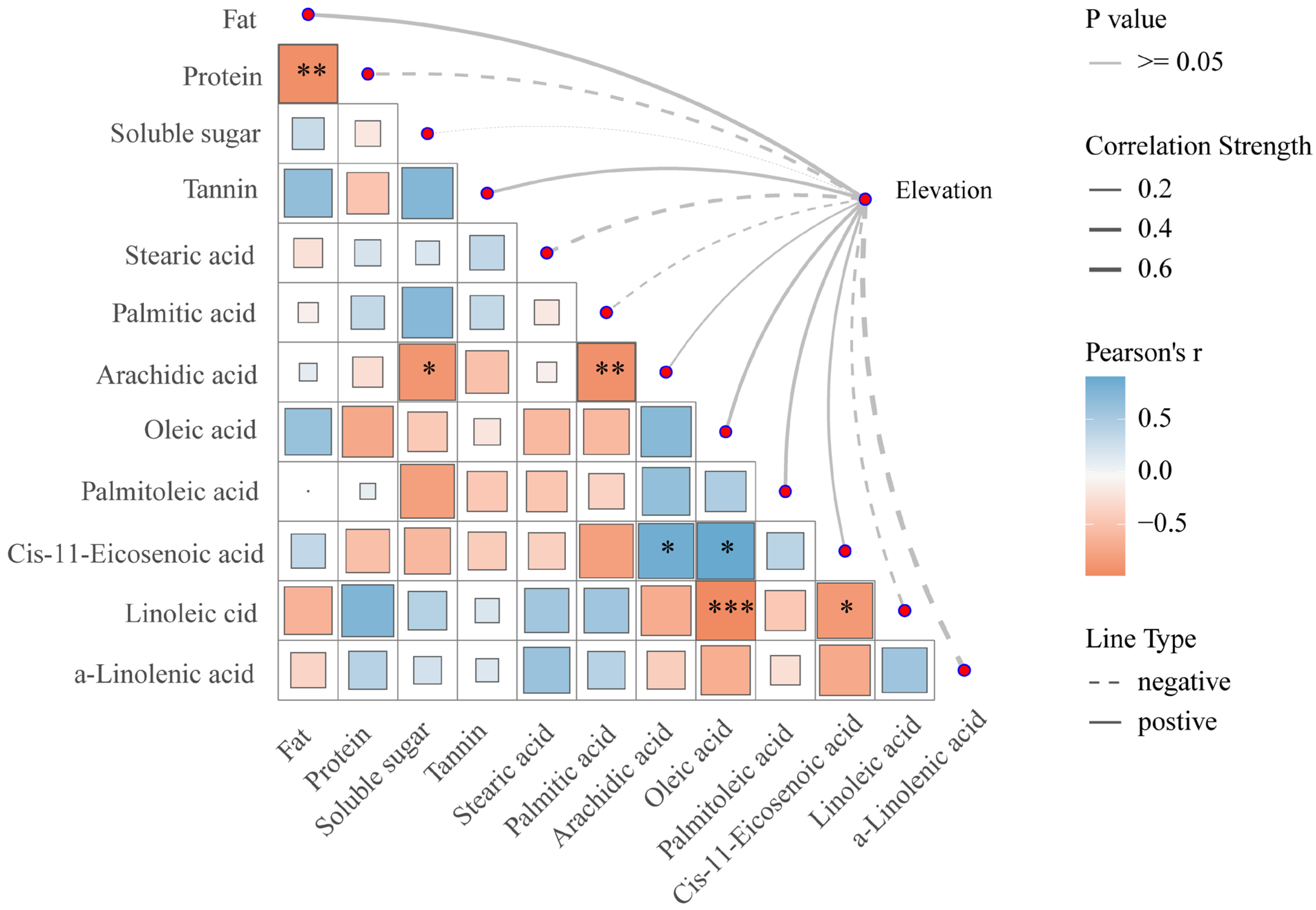

3.5. Visualization Analysis of Mantel Test for Walnut Nutritional Quality at Different Elevations

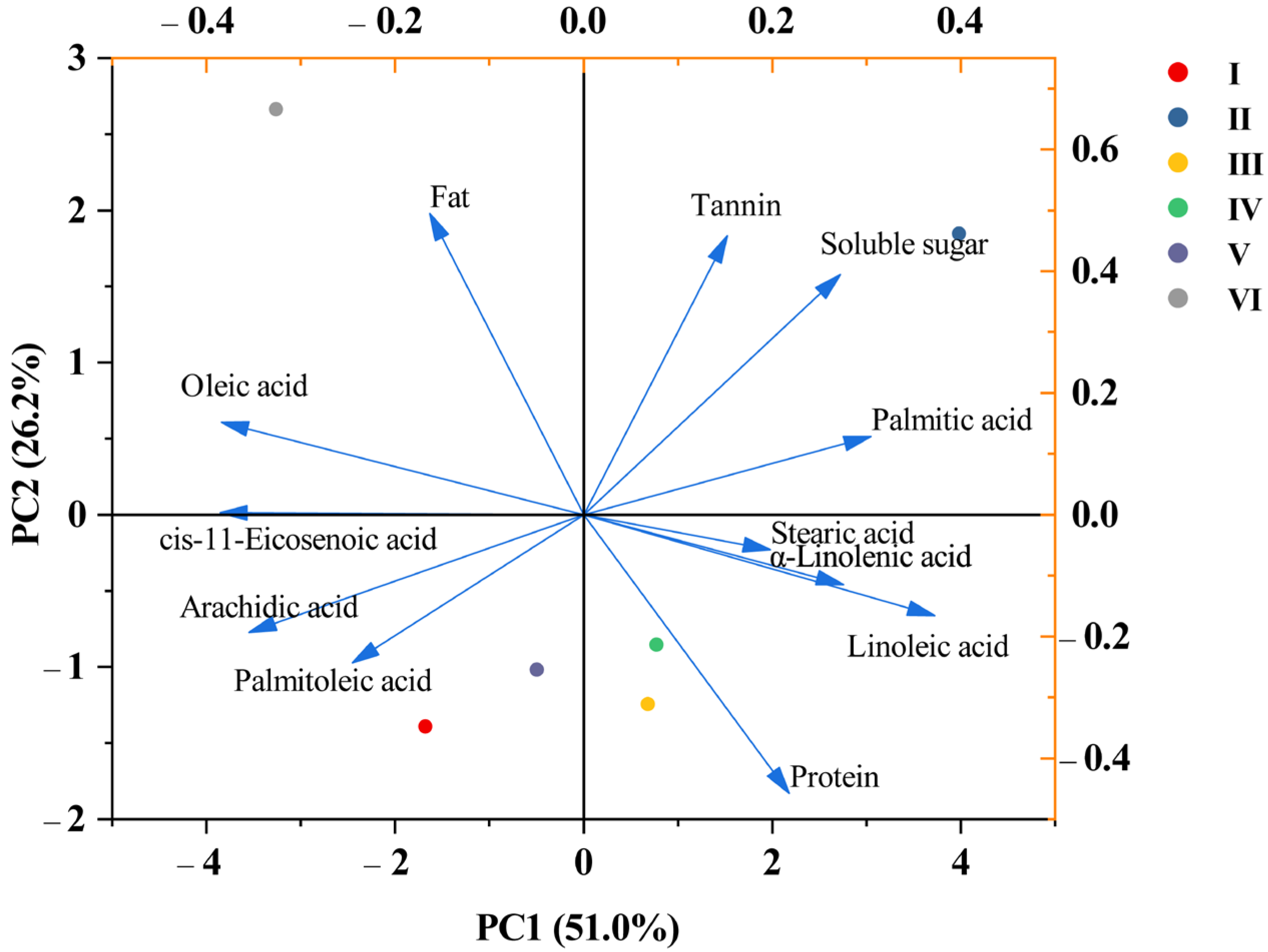

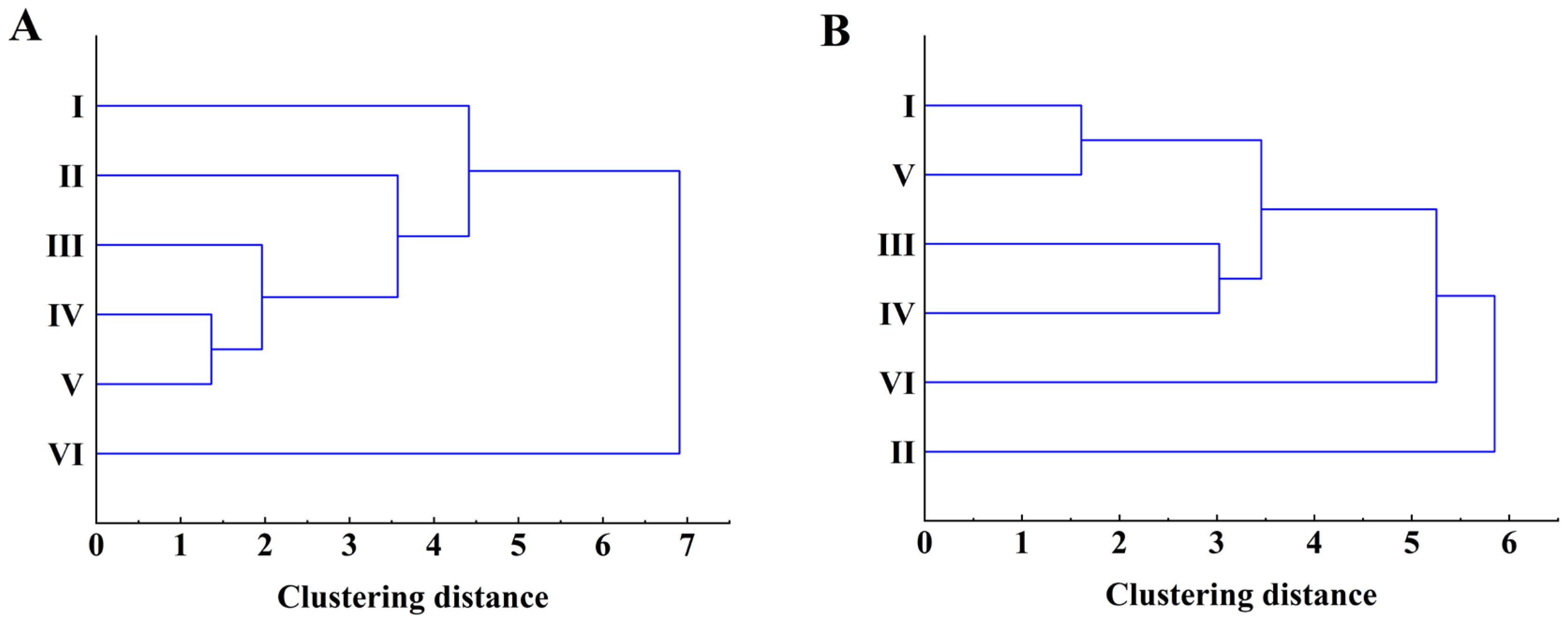

3.6. Analysis of PCA for Walnut Nutritional Quality at Different Elevations

3.7. Subordinate Function Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, X.; Tang, J.; Fan, W.; Li, B.; Bai, Y.; He, J.; Pei, D.; Zhang, J. Phenotypic Differences and Physiological Responses of Salt Resistance of Walnut with Four Rootstock Types. Plants 2022, 11, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; He, W.; Zhao, S.; Jiao, T.; Hu, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Zang, J. Advanced insights into walnut protein: Structure, physiochemical properties and applications. Foods 2023, 12, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuppalapati, C. Specialty Crops: Walnuts. In Specialty Crops for Climate Change Adaptation: Strategies for Enhanced Food Security by Using Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 515–625. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Wu, C.; Zheng, X.; Nie, R.; Tang, J.; Ji, X.; Zhang, J. Physiological and biochemical responses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in symbiosis with Juglans nigra L. seedlings to alleviate salt stress. Rhizosphere 2024, 31, 100928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Lheureux, F.; Dirlewanger, E. Walnut: Past and future of genetic improvement. Tree Genet. Genomes 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.; Hu, H.; Xu, G. Cold Hardiness and Physio-Biochemical Responses of Annual Branches in Five Early-Fruiting Walnut Varieties (Juglans regia L.) Under Simulated Low-Temperature Stress. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Stokes, A.; Mao, Z.; Jourdan, C.; Sabatier, S.; Pailler, F.; Fourtier, S.; Dufour, L.; Monnier, Y. Linking above-and belowground phenology of hybrid walnut growing along a climatic gradient in temperate agroforestry systems. Plant Soil 2018, 424, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Pan, K.; Zhang, A.; Wu, X.; Tariq, A.; Chen, W.; Li, Z.; Sun, F.; Sun, X.; Olatunji, O.A. Optimization of growth and production parameters of walnut (Juglans regia) saplings with response surface methodology. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Z.-J.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Chen, S.-X.; Thakur, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.-G.; Shang, Y.-F.; Wei, Z.-J. Exploration of walnut components and their association with health effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 5113–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.; Angove, M.J.; Tucci, J.; Dennis, C. Walnuts (Juglans regia) chemical composition and research in human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyhan, O.; Ozcan, A.; Ozcan, H.; Kafkas, E.; Kafkas, S.; Sutyemez, M.; Ercisli, S. Fat, fatty acids and tocopherol content of several walnut genotypes. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2017, 45, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, J.R.; Fitzsimmons-Thoss, V. Determination of unsaturated fatty acids composition in walnut (Juglans regia L.) oil using NMR spectroscopy. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafkas, E.; Attar, S.H.; Gundesli, M.A.; Ozcan, A.; Ergun, M. Phenolic and fatty acid profile, and protein content of different walnut cultivars and genotypes (Juglans regia L.) grown in the USA. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2020, 20, S1711–S1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, E.; Mataix, J. Fatty acid composition of nuts–implications for cardiovascular health. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 96, S29–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Ma, Z.F.; Zhang, H.; Ma, S.; Kong, L. Structural characteristics and functional properties of walnut glutelin as hydrolyzed: Effect of enzymatic modification. Int. J. Food Prop. 2019, 22, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze-Tao, K.W.C.; Sathe, S.K. Walnuts (Juglans regia L): Proximate composition, protein solubility, protein amino acid composition and protein in vitro digestibility. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Protein Quality Evaluation: Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation, Bethesda, Md., USA 4-8 December 1989; Food & Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kazankaya, A.; Balta, M.F.; Yörük, I.; Balta, F.; Battal, P. Analysis of sugar composition in nut crops. Asian J. Chem. 2008, 20, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Zhong, L.; Yang, H.; Hou, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, R.; Yu, J.; Cheng, Y. Systematic transcriptomic and metabolomic analysis of walnut (Juglans regia L.) fruit to trace variations in antioxidant activity during ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 295, 110849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhong, L.; Yang, H.; Zhu, F.; Hou, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, Y. Comparative analysis of antioxidant activities between dried and fresh walnut kernels by metabolomic approaches. LWT 2022, 155, 112875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündeşli, M.A.; Uğur, R.; Yaman, M. The Effects of Altitude on Fruit Characteristics, Nutrient Chemicals, and Biochemical Properties of Walnut Fruits (Juglans regia L.). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Su, S.; Zhang, H. Effects of canopy microclimate on Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima Blume) nut yield and quality. Forests 2020, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Si, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Y.; Su, S. Effects of canopy position and microclimate on fruit development and quality of Camellia oleifera. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, A.; Jeena, N.; Singh, R.; Singh, H. Factors influencing soil ecosystem and agricultural productivity at higher altitudes. In Microbiological Advancements for Higher Altitude Agro-Ecosystems & Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jeyakumar, S.P.; Dash, B.; Singh, A.K.; Suyal, D.C.; Soni, R. Nutrient cycling at higher altitudes. In Microbiological Advancements for Higher Altitude Agro-Ecosystems & Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yi, H.; Gao, X.; Bai, T.; Ni, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, J.; Yu, W.; et al. Effect of Different Altitudes on Morpho-Physiological Attributes Associated with Mango Quality. Diversity 2022, 14, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Breksa, A.P., III; Mishchuk, D.O.; Slupsky, C.M. Elevation, Rootstock, and Soil Depth Affect the Nutritional Quality of Mandarin Oranges. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 2672–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-H.; Wang, Y.-S.; Wei, L.-B.; Feng, D.-L.; Li, X.-Z.; Xia, Y. Soil nutrient status and fertility evaluation in major producing areas of walnut, Chongqing. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2023, 51, 88–93, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Medda, S.; Fadda, A.; Mulas, M. Influence of climate change on metabolism and biological characteristics in perennial woody fruit crops in the Mediterranean environment. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyuncu, M.A.; Ekinci, K.; Gun, A. The effects of altitude on fruit quality and compression load for cracking of walnuts (Juglans regia L.). J. Food Qual. 2004, 27, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryal, A.; Dolkar, D.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Kant, A.; Chaurasia, O.; Stobdan, T. Effect of altitude on the phenology and fruit quality attributes of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) fruits. Def. Life Sci. J. 2020, 5, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trad, M.; Gaaliche, B.; Renard, C.M.; Mars, M. Inter-and intra-tree variability in quality of figs. Influence of altitude, leaf area and fruit position in the canopy. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 162, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naryal, A.; Acharya, S.; Bhardwaj, A.K.; Kant, A.; Chaurasia, O.P.; Stobdan, T. Altitudinal effect on sugar contents and sugar profiles in dried apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) fruit. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 76, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Liu, M.; Chen, M.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Mou, T.; Wang, A.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Jiang, L. The Effect of Different Altitude Conditions on the Quality Characteristics of Turnips (Brassica rapa). Agronomy 2025, 15, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhatwalia, J.; Kumari, A.; Guleria, I.; Kumar Shukla, R.; Saleh, N.i.; El-Nashar, H.A.; El-Shazly, M. Effect of altitude and harvest year on nutraceutical characteristics of Rubus ellipticus fruits. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1419862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, C.; Nocerino, S.; Paduano, A.; Sacchi, R. Influence of some environmental factors on drupe maturation and olive oil composition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Zhang, D.; Ma, Z. Transcriptome Analysis of Genes Involved in Fatty Acid and Lipid Biosynthesis in Developing Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Seed Kernels from Qinghai Plateau. Plants 2022, 11, 3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüksolak, Z.N.; Akn, M.A.; Kahramanolu, B.; Okatan, V. Effects of Altitude on the Pomological Characteristics and Chemical Properties of ‘Chandler’ Walnuts: A Case Study in Uak Province. Acta Agrobot. 2020, 73, 7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Qin, S.; Yang, W.; Ma, X.; Qiao, X.; Yang, B. Effects of Genetic Background and Altitude on Sugars, Malic Acid and Ascorbic Acid in Fruits of Wild and Cultivated Apples (Malus sp.). Foods 2021, 10, 2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.M.; Alharbi, B.M.; Abdulmajeed, A.M.; Elkelish, A.; Hozzein, W.N.; Hassan, H.M. Oxidative stress responses of some endemic plants to high altitudes by intensifying antioxidants and secondary metabolites content. Plants 2020, 9, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Cong, Z.; Wang, C.; He, M.; Liu, C.; Gao, P. Research progress on Walnut oil: Bioactive compounds, health benefits, extraction methods, and medicinal uses. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Ding, N.-Z. Plant unsaturated fatty acids: Multiple roles in stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 562785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Lipid metabolism in plants under low-temperature stress: A review. In Physiological Processes in Plants Under Low Temperature Stress; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 409–516. [Google Scholar]

- Beyhan, O.; Elmastas, M.; Genc, N.; Aksit, H. Effect of altitude on fatty acid composition in Turkish hazelnut (Coryllus avellana L.) varieties. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 16064–16068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.G.; Kothapalli, K.S.; Park, W.J.; DeAllie, C.; Liu, L.; Liang, A.; Lawrence, P.; Brenna, J.T. Palmitic acid (16:0) competes with omega-6 linoleic and omega-3 ɑ-linolenic acids for FADS2 mediated Δ6-desaturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1861, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, P.T.; Nguyen, C.X.; Bui, H.T.; Tran, L.T.; Stacey, G.; Gillman, J.D.; Zhang, Z.J.; Stacey, M.G. Demonstration of highly efficient dual gRNA CRISPR/Cas9 editing of the homeologous GmFAD2–1A and GmFAD2–1B genes to yield a high oleic, low linoleic and α-linolenic acid phenotype in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W. Genome-wide identification of FAD gene family and functional analysis of MsFAD3. 1 involved in the accumulation of α-linolenic acid in alfalfa. Crop Sci. 2021, 61, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.K.; Mishra, G. Functional characterization and expression profile of microsomal FAD2 and FAD3 genes involved in linoleic and α-linolenic acid production in Leucas cephalotes. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Region | Sample Size (Sample) | Elevation Range (m) | Annual Temperature (°C) | Annual Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beibei | 3 | 497~516 | 18.2 | 1156.8 |

| Qianjiang | 8 | 556~948 | 15.4 | 1200.3 |

| Liangping | 3 | 474~524 | 16.6 | 1262 |

| Chengkou | 67 | 1064~1792 | 13.8 | 1261.4 |

| Fengdu | 10 | 905~1405 | 18.5 | 1200 |

| Wulong | 5 | 865~1340 | 14.5 | 1258 |

| Zhongxian | 3 | 710~890 | 17 | 1167 |

| Kaizhou | 7 | 1457~1610 | 18.5 | 1200 |

| Yunyang | 6 | 910~1420 | 20 | 950 |

| Fengjie | 10 | 1200~1478 | 16 | 1132 |

| Wushan | 14 | 600~1600 | 14 | 1200 |

| Wuxi | 28 | 616~1790 | 14.8 | 1350 |

| Shizhu | 3 | 810~1100 | 12.4 | 1200 |

| Xiushan | 4 | 615~980 | 16 | 1341.1 |

| Youyang | 6 | 910~977 | 15.2 | 1353 |

| Pengshui | 4 | 820~983 | 15 | 1104.2 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Maximum | Minimum | Range | Coefficient of Variation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat (%) | 61.15 | 4.122 | 68.7 | 46.2 | 22.5 | 0.067 |

| Protein (%) | 17.196 | 2.108 | 23.4 | 12.3 | 11.1 | 0.123 |

| Soluble sugar (%) | 2.218 | 1.284 | 8.42 | 0.38 | 8.04 | 0.579 |

| Tannin (g/kg) | 9.997 | 2.099 | 16.3 | 2.39 | 13.91 | 0.21 |

| Stearic acid (%) | 2.723 | 0.526 | 4.7 | 1.38 | 3.32 | 0.193 |

| Palmitic acid (%) | 5.692 | 0.517 | 7.2 | 4.505 | 2.695 | 0.091 |

| Arachidic acid (%) | 0.095 | 0.01 | 0.103 | 0.054 | 0.048 | 0.101 |

| Oleic acid (%) | 23.396 | 6.666 | 51 | 10.9 | 40.1 | 0.285 |

| Palmitoleic acid (%) | 0.11 | 0.034 | 0.246 | 0.056 | 0.19 | 0.31 |

| cis-11-Eicosenoic acid (%) | 0.184 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.165 |

| Linoleic acid (%) | 59.284 | 5.765 | 71.9 | 36.3 | 35.6 | 0.097 |

| α-Linolenic acid (%) | 8.548 | 1.709 | 13.3 | 4.59 | 8.71 | 0.2 |

| Principal Component Number | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 6.122 | 3.15 | 1.503 | 0.794 | 0.43 |

| Percentage of Variance (%) | 51.021 | 26.249 | 12.527 | 6.619 | 3.584 |

| Cumulative (%) | 51.021 | 77.269 | 89.796 | 96.416 | 100 |

| Fat | −0.163 | 0.495 | 0.049 | 0.274 | 0.077 |

| Protein | 0.218 | −0.458 | −0.152 | −0.058 | 0.171 |

| Soluble sugar | 0.272 | 0.395 | −0.092 | −0.223 | −0.089 |

| Tannin | 0.152 | 0.458 | 0.206 | 0.25 | 0.444 |

| Stearic acid | 0.198 | −0.057 | 0.705 | −0.008 | 0.087 |

| Palmitic acid | 0.305 | 0.129 | −0.482 | 0.153 | −0.164 |

| Arachidic acid | −0.355 | −0.193 | 0.267 | 0.071 | 0.013 |

| Oleic acid | −0.384 | 0.152 | −0.079 | 0.008 | −0.186 |

| Palmitoleic acid | −0.245 | −0.244 | −0.21 | 0.635 | 0.365 |

| cis-11-Eicosenoic acid | −0.385 | 0.003 | 0.083 | −0.309 | −0.102 |

| Linoleic acid | 0.372 | −0.166 | 0.046 | −0.115 | 0.345 |

| α-Linolenic acid | 0.275 | −0.115 | 0.253 | 0.518 | −0.655 |

| Elevation | μ (1) | μ (2) | μ (3) | μ (4) | D-Value | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 0.218 | 0 | 1 | 0.398 | 0.273 | 6 |

| II | 1 | 0.799 | 0.845 | 0.276 | 0.875 | 1 |

| III | 0.545 | 0.036 | 0 | 0.124 | 0.307 | 5 |

| IV | 0.557 | 0.132 | 0.612 | 1 | 0.479 | 2 |

| V | 0.382 | 0.092 | 0.987 | 0 | 0.355 | 4 |

| VI | 0 | 1 | 0.511 | 0.395 | 0.366 | 3 |

| Wj | 0.529 | 0.272 | 0.13 | 0.069 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tang, J.; Li, A.; Tong, L.; Ji, X.; Su, Y.; Sun, L.; Nie, R.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. Variations in Nutritional Composition of Walnut Kernels Across Different Elevations in Chongqing Region, China. Horticulturae 2026, 12, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010016

Tang J, Li A, Tong L, Ji X, Su Y, Sun L, Nie R, Wu C, Li X, Zhang J. Variations in Nutritional Composition of Walnut Kernels Across Different Elevations in Chongqing Region, China. Horticulturae. 2026; 12(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Jiajia, Ao Li, Long Tong, Xinying Ji, Yi Su, Leyuan Sun, Ruining Nie, Chengxu Wu, Xiuzhen Li, and Junpei Zhang. 2026. "Variations in Nutritional Composition of Walnut Kernels Across Different Elevations in Chongqing Region, China" Horticulturae 12, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010016

APA StyleTang, J., Li, A., Tong, L., Ji, X., Su, Y., Sun, L., Nie, R., Wu, C., Li, X., & Zhang, J. (2026). Variations in Nutritional Composition of Walnut Kernels Across Different Elevations in Chongqing Region, China. Horticulturae, 12(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae12010016