Abstract

Agronomic management directly influences soil and berry quality in vineyards, a crop of global relevance. However, some knowledge gaps regarding the effects of management practices in traditional vineyards of the Itata Valley in Chile remain. This study evaluated the impact of contrasting management systems: non-managed País (PA), conventionally managed País (CPA), organically managed Cinsault (OCI) and organically managed Carmenere (OCA), on soil bioindicators, chemical composition and berry rheological properties. The results showed that organic management, such as OCA, resulted in 96% and 95% higher dehydrogenase and urease activities, respectively, while OCI exceeded CPA by 86% and 173% in arylsulfatase and phosphatase activities, respectively. The CPA treatment exhibited significantly higher available nitrogen compared with PA (231%), OCI (509%) and OCA (236%), as well as greater available phosphorus than OCI (503%) and OCA (413%). Regarding berry rheology, OCA displayed the highest pulp viscosity compared to OCI, although the differences among treatments were not statistically significant. Multivariate analysis associated CPA with higher soil chemical fertility, whereas organic systems (OCI and OCA) were related to greater soil bioactivity and fruit viscosity. Therefore, organic management is recommended to improve soil biological functionality and fruit structural stability, contributing to the long-term sustainability of vineyards in the valley.

1. Introduction

Chile is one of the top producers wine producers and wine exporters, with 166,000 hectares under cultivation, representing 3.2% of the global vineyard area, and ranking among the world’s top ten wine exporters [1]. Viticulture in Chile’s historical valleys stands out not only for its economic contribution but also for its cultural and social significance [2]. Grapevines grow under edaphoclimatic conditions characterized by a Mediterranean climate with dry summers, classified mainly as Csa (hot-summer Mediterranean) in inland zones and Csb (warm-summer Mediterranean) in coastal areas, according to the Köppen–Geiger classification [3]. These conditions include high solar radiation, a marked diurnal temperature range of 12 to 15 °C [3] and soils of volcanic and granitic origin [4]. Such edaphoclimatic conditions promote the accumulation of sugars, synthesis of phenolic compounds, and preservation of berry acidity, all of which enhance wine quality [5]. The Itata Valley, located in the Ñuble Region of central-southern Chile, has a tradition of grape cultivation and wine production spanning over four centuries. Wine production in the Valley is characterized by the predominance of heritage varieties such as País and Muscat of Alexandria [6]. The presence of century-old dry-farmed vineyards and the wide varietal diversity have established the Valley as a centre for traditional and niche wines with high added value, as well as a growing demand in specialized markets [6]. However, in these valleys, there is still limited information on abiotic factors such as agronomic management, which can alter soil characteristics and affect both yield and berry quality [7].

The type of agronomic management applied in vineyards is a particularly relevant factor as it affects vineyard productivity, influences varietal expression and determines long-term sustainability [8]. In Chile, vineyards are managed under different agronomic systems, ranging from minimal intervention to conventional and organic management [9]. Conventional vineyard systems are characterized by the intensive use of synthetic inputs such as mineral fertilizers and chemical pesticides [10,11]. In contrast, organic systems promote the incorporation of natural techniques such as compost, manure and green fertilizers, the use of cover crops, mechanical weed control and the regulation of pests through biological agents [12]. Although both management systems can achieve high fruit productivity, they differ in terms of the chemical and biological composition of the soil. For example, when comparing vineyards managed organically and conventionally, Colautti et al. (2023) [13] reported that organic management resulted in higher concentrations of Cu, while conventional management exhibited higher levels of Na and Mg and greater pH values, with no significant changes in microbial composition. Therefore, agronomic management can modify the chemical and biological composition of the soil, which in turn affects the physicochemical characteristics of the berries, including sugar content, phenolic compounds and secondary metabolites responsible for the sensory profile of wines [14].

Soil health is determined by the interaction among its physical, chemical and biological properties [15]. The latter, which includes soil enzymatic activity, are also referred to as bioindicators and are widely used as sensitive tools to evaluate changes in soil ecosystem quality and functionality [16]. Agronomic management directly influences soil health, producing effects that can impact plant physiological expression and productivity [17]. In particular, practices associated with organic management, such as the application of compost and the use of cover crops, have been shown to improve soil health by increasing enzymatic activity in key nutrient cycles, including N, P and K [18]. Similarly, comparative studies in vineyards have indicated that organic management, compared with conventional systems, can significantly enhance physical and chemical soil properties, supporting vegetative growth, berry quality and sometimes phenolic content [19]. In this context, in addition to assessing soil health, it is essential to consider berry quality. For instance, grapes cultivated under organic management have been reported to exhibit significantly higher total polyphenol and tannin levels than those under conventional management [20]. Recently, techniques such as rheological analysis have been employed to evaluate enological quality and sensory perception, including fluid viscosity among other variables [21]. However, the effects of agronomic management on soil bioindicators and rheological properties such as fluid viscosity remain scarcely explored in heritage vineyards of Chile, particularly in the Itata Valley.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effect of agronomic management type (non-managed, conventional, and organic) on soil quality bioindicators, including basal soil respiration and enzymatic activities related to the C, N, P, and S cycles, as well as on available soil chemical elements (organic matter, macroelements, and microelements) and berry viscosity in vineyards of the Itata Valley. We hypothesized that vineyards under organic management would significantly improve their biological properties, such as respiration and enzymatic activity, compared with vineyards managed conventionally or without agronomic intervention. This expectation is based on the fact that organic management promotes larger and more active microbial communities due to improved soil physical conditions and greater incorporation of organic carbon [22]. Conversely, conventionally managed vineyards were expected to show significantly higher levels of available soil nutrients than organic and non-managed vineyards. In addition, it was anticipated that the type of management would influence berry quality, reflected in changes in apparent viscosity as a function of distribution and shear rate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Sampling and Study Area

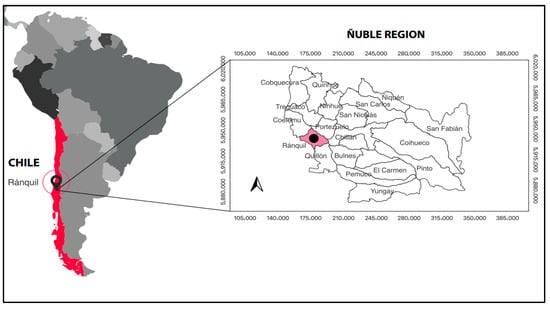

Soil samples were collected from a vineyard located in the commune of Ránquil, in the Itata Valley, Ñuble Region, Chile (36.68777° S, 72.63636° W) (Figure 1), which contained different grape varieties and agronomic management systems. The oldest variety in the vineyard, País, dates back to 1768. The area is characterized by granitic soils [4], moderate slopes ranging from 8% to 20% [23] and varying levels of fertility. Grapevines grow under rainfed conditions in a Csb-type climate according to the Köppen classification (Mediterranean climate with cool summers), with an average annual temperature of 14 °C [3]. Precipitation in the sampling area reached 815 mm in 2024 [24]. Soil and berry samples were collected in April 2025, and each composite sample consisted of four subsamples. Soil samples (1 kg) were collected at a depth of 20 cm, according to [25], from the grapevine rhizosphere, from which 500 g were used for chemical analysis at the Soil and Water Analysis Laboratory of the University of Concepción, Chillán, Chile. Another 500 g subsample was stored at 5 °C and transported to the Soil Microbiology Laboratory of the University of Concepción, Concepción, Chile, for analysis of biological activity.

Figure 1.

Map showing South America, indicating the location of the commune of Ránquil in Chile, and the sampling site (black dot) in the commune of Ránquil, Itata Province, Ñuble Region, Chile.

The experimental design was based on real conditions in a heritage vineyard, where the combinations of variety and management correspond to current agricultural practices in the Itata Valley. The treatments corresponded to different combinations of agronomic management and grape varieties: (i) non-managed País (PA), (ii) conventionally managed País (CPA), (iii) organically managed Cinsault (OCI), and (iv) organically managed Carmenere (OCA). The conventional management involved inorganic fertilization with a mixture of macronutrients nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K), along with the application of red guano, while weeds were controlled using chemical herbicides. Organic management, implemented since 2020, consisted of soil fertilization with animal- and plant-based amendments, including chicken, turkey, and goat manure, oat straw, and grape pomace, while weed control was performed using grazing animals such as geese and goats. Organic management was complemented by a foliar application of 30% wine vinegar as a phytosanitary treatment. The non-managed vines received no weed control, fertilization, or phytosanitary interventions. The selection of varieties was based on their prevalence within each predominant management system in the Itata Valley, prioritizing the comparison of agronomic practices under real productive conditions in the Itata Valley.

2.2. Soil Biological Activity Analysis

Soil microbiological activity was determined based on basal soil respiration and the activity of enzymes related to the C, N, P and S cycles. Soil respiration was measured following the method described by Alef and Nannipieri (1995) [26], in which 25 g of soil were incubated (Memmert GmbH, Schwabach, Germany) at 22 °C for seven days. The incubated solution was then titrated with 0.1 M HCl (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and respiration was expressed as µg of CO2 produced per gram of dry soil per hour. Urease activity was determined according to the method described by Nannipieri et al. (1980) [27] and expressed as µmol of NH4+ produced per gram of dry soil per hour. Acid phosphatase activity was quantified following the procedure described by Naseby and Lynch (1997) [28], with results expressed as µmol of p-nitrophenol (PNP) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) per gram of dry soil per hour. Dehydrogenase activity was assessed according to García et al. (1997) [29], by exposing the soil for 20 h to INT (2-p-iodophenyl-3-p-nitrophenyl-5-phenyltetrazolium chloride) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to form INTF and expressed as µg of INTF per gram of soil. Arylsulfatase activity was determined following the method described by Tabatabai and Bremner (1970) [30] and expressed as µmol of p-nitrophenol (PNP) released per gram of dry soil per hour.

2.3. Chemical Analysis of the Soil

Soil pH (Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) was determined using a soil-to-water suspension (1:5, w/v). The remaining chemical parameters, including organic matter, nitrate (N–NO3−), ammonium (N–NH4+), available nitrogen (N), available phosphorus (P–Olsen), available and exchangeable potassium (K), exchangeable calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), sodium (Na) and aluminum (Al), base sum, effective cation exchange capacity (ECEC), saturation of Al, K and Ca, available sulphur (S), iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), boron (B) and electrical conductivity, were determined according to the procedures described by Sadzawka et al. (2006) [31]. All analyses were performed according to ISO 17025 standards [32] at the Soil Laboratory of the Department of Soils and Natural Resources, University of Concepción, Chillán, Chile.

2.4. Fruit Rheometry Analysis

The rheological behaviour of grape pulp samples was determined by measuring shear stress (τ) as a function of shear rate (γ·) using an Anton Paar SmartPave 102e (Anton Paar GmbH, Graz, Austria) rotational rheometer equipped with a CP25-1 measuring cone (25 mm, 1° angle) under controlled temperature [33]. Apparent viscosity curves were fitted to the Carreau and Power Law models, selected for their ability to describe the pseudoplastic behaviour typical of complex food systems. Fruits from the different grape varieties were manually ground until obtaining an aqueous paste [34]. All samples were packaged in polyethylene bags and stored at 4 °C until rheological analysis. Measurements were conducted in quintuplicate, and apparent viscosity data were recorded as a function of shear rate.

Model fitting was carried out by nonlinear regression using MATLAB R2024a [35], and the goodness of fit was evaluated through the coefficient of determination (R2). The most appropriate model for each sample was selected based on the R2 value and the visual agreement between experimental and fitted curves. Chemical analyses of reference fruit for each grape variety were performed by the producer on 15 March 2022 (Supplementary Material Table S1).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To determine significant differences among vineyard management treatments, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test at a significance level of p = 0.05, when assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were met. Statistical analyses were carried out using Infostat software version 2008 (Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina). [36]. To assess relationships among soil variables affected by agronomic management, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, applying a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with a significance level of p = 0.05 using RStudio software, version R 4.5.1 [37].

3. Results

3.1. Biological Activity of the Soil

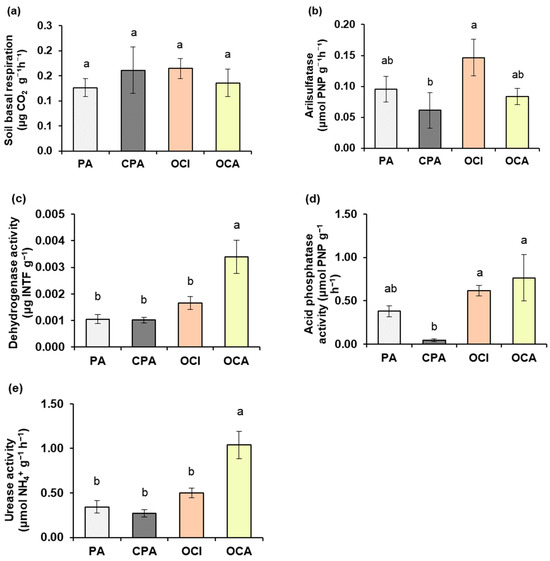

Basal soil respiration did not show significant improvement among management treatments, with values ranging between 0.13 µg CO2 g−1 h−1 and 0.16 µg CO2 g−1 h−1. However, consistent with the proposed hypothesis, significant increases in enzymatic activities were observed because of agronomic management, particularly in the organically managed treatments (Figure 2). Arylsulfatase activity was 86% higher (p < 0.05) in OCI compared with CPA, while PA and OCA showed no significant differences among treatments. Dehydrogenase and urease activities increased significantly in OCA compared with the other treatments, with average increases of 96% and 95%, respectively. Acid phosphatase activity was statistically higher in OCI and OCA than in CPA (173% and 178%, respectively), whereas PA, with an average of 0.38 µmol PNP g−1 h−1, showed no significant differences among treatments.

Figure 2.

Soil activity in vineyards in the Itata Valley: (a) basal soil respiration and enzymatic activities of (b) arylsulfatase, (c) dehydrogenase, (d) acid phosphatase, (e) urease. Treatment: PA: País (without agronomic management); CPA: conventional País; OCI: organic Cinsault; OCA: organic Carmenere. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatments according to Fischer’s LSD test (p < 0.05). Mean ± standard error (n = 4). Bars correspond to the experimental error for each treatment.

3.2. Chemical Properties of Soil

Soil chemical variables showed significant differences among agronomic managements (Table 1). Consistent with the proposed hypothesis, CPA was one of the treatments with the highest nutrient availability. CPA contained more nitrate (p < 0.05) than PA (200%), OCI (720%) and OCA (310%). Similarly, ammonium was significantly higher in CPA compared with PA (308%), OCI (322%) and OCA (159%). Consequently, available nitrogen (nitrate plus ammonium) was significantly higher in CPA than in PA (231%), OCI (509%) and OCA (236%). CPA also produced significantly higher available phosphorus than OCI (503%) and OCA (413%), respectively. Potassium saturation was significantly higher in CPA, with a 75% increase compared with OCI.

Table 1.

Chemical analysis of soils from the study sites of the Itata Valley, Ñuble Region, Chile.

In contrast, PA, CPA and OCA exhibited higher available potassium (p < 0.05) than OCI, with increases of 166%, 184% and 140%, respectively. Similarly, PA, CPA and OCA generated more exchangeable calcium (p < 0.05) than OCI, with increases of 98%, 73% and 67%, respectively. The sum of bases was significantly greater in PA, CPA and OCA than in OCI, with increases of 91%, 60% and 59%, respectively. Effective exchange capacity was also significantly higher in PA, CPA and OCA compared with OCI, with increases of 90%, 59% and 58%, respectively.

PA produced more exchangeable magnesium (p < 0.05) than CPA (84%), OCI (53%) and OCA (41%). PA also generated significantly higher copper content than OCI (160%) and OCA (86%). In contrast, OCI exhibited higher aluminum saturation (p < 0.05) than PA (400%), CPA (341%), and OCA (341%). OCI also produced significantly higher available sulphur than PA (25%), CPA (96%) and OCA (46%). The OCA management generated significantly higher boron content than PA, CPA and OCI, with increases of 319%, 450% and 1000%, respectively. Meanwhile, OCI and PA produced significantly higher iron content than OCA, with increases of 137% and 102%, respectively.

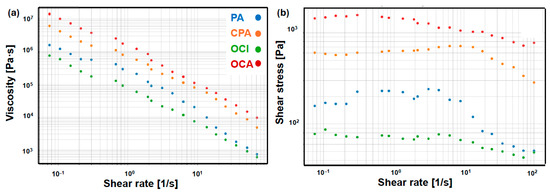

3.3. Rheometry of Fruits

The rheological results (Figure 3) showed that all grape pulps exhibited pseudoplastic behaviour, with a decrease in viscosity as the shear rate increased. Viscosity was significantly higher in OCA, followed by CPA, PA and OCI, with differences exceeding 95% between the extreme values. This pattern indicates a denser and more cohesive internal structure in OCA, whereas OCI showed a more fluid matrix with lower resistance to flow. Shear stress increased with shear rate in all pulps, although with sublinear slopes, confirming the progressive breakdown of the internal structure. The highest values were again recorded in OCA, suggesting a higher consistency index (K) and a flow index (n) lower than 1, typical of highly pseudoplastic materials. Overall, OCA and CPA exhibited greater structural resistance and stability, while PA and OCI showed higher fluidity and lower cohesion.

Figure 3.

Rheological profiles of grape pulps subjected to different handling practices. (a) Apparent viscosity and (b) shear stress as a function of shear rate. PA: País (without agronomic management); CPA: conventional País; OCI: organic Cinsault; OCA: organic Carmenere.

3.4. Fruit Viscosity

The fitting of apparent viscosity curves as a function of shear rate (γ·) for the four grape pulp samples (PA, CPA, OCI and OCA) was performed using the Carreau and Power Law models. These models were selected based on the quality of fit and the shape of the obtained curves, showing an excellent fit for all datasets. Different models were used for the samples: the Carreau model was applied to the País variety, which was subjected to different vineyard management practices, whereas data from the Cinsault and Carmenere varieties under the same agronomic management were fitted to the Power Law model.

The analysis of apparent viscosity at a shear rate of 50 s−1 showed that the PA and CPA treatments presented lower variability with more homogeneous distributions. In contrast, the OCI and OCA treatments exhibited greater dispersion and the presence of outlier values, suggesting a more heterogeneous internal structure possibly associated with compositional differences. These observations were supported by the statistical analyses: the one-way ANOVA indicated no significant differences among treatments, which was confirmed by the Kruskal–Wallis test (p = 0.065). However, Levene’s test revealed heterogeneity of variances (p = 0.027), consistent with the greater variability observed in the organic treatments. Although statistical significance was not reached, the results suggested a tendency toward differences. Overall, these findings indicate that, while mean viscosity values did not differ significantly among treatments, the variability observed in the organic samples may reflect structural heterogeneity with potential technological implications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rheological models applied to the berry pulp of different vineyard management systems.

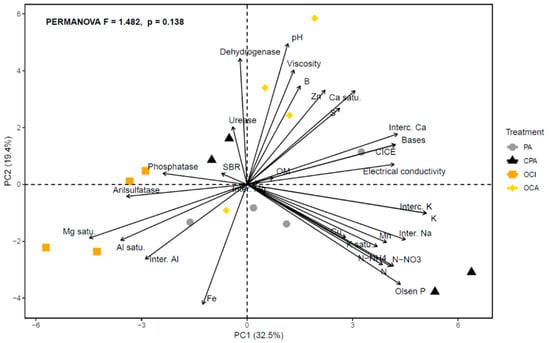

3.5. Analysis of Principal Components of Soil Variables and Fruit Viscosity

The principal component analysis (Figure 4) showed that PC1 and PC2 together explained 52% of the total variability in the dataset. Along the PC1 axis, variables associated with soil chemical fertility, such as electrical conductivity, cation exchange capacity, exchangeable bases (Ca, K, Na), nitrates and available phosphorus, were grouped within the CPA treatment. In contrast, at the negative end of the PC1 axis, variables indicative of acidity and aluminum and magnesium saturation (Al saturation, Mg saturation and exchangeable Al), together with the enzyme’s phosphatase and arylsulfatase, were concentrated in the OCI and OCA treatments, representing more acidic soils with lower chemical fertility. The PA treatment was associated with several soil variables, including organic matter, nutrients such as Cu, effective cation exchange capacity and exchangeable bases. However, the MANOVA indicated no significant differences among treatments (p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and PERMANOVA for agronomic management (PA: País (without agronomic management); CPA: conventional País; OCI: organic Cinsault; OCA: organic Carmenere)) performed on the soil and fruit variables (pH; organic matter = OM; Nitrate N = N-NO3; Ammonium N = N-NH4 N; Olsen P; Potassium = K; Exchangeable K = Interc. K; Exchangeable Ca = Interc. Ca; Exchangeable Mg = Inter. Mg; Exchangeable Na = Inter. Na; Bases; Exchangeable Al = Inter. Al; CICE; Al saturation = Al saturation; K saturation = K saturation; Ca saturation = Ca saturation; Mg saturation = Mg saturation; S; Fe; Mn; Zn; Cu; B; Electrical conductivity; SBR = soil basal respiration; enzyme activities; Arylsulfatase; Dehydrogenase; Phosphatase; Urease and Fruit viscosity).

Positive associations were observed among variables, particularly between fruit viscosity, pH and boron, and to a lesser extent with biological activity (dehydrogenase, urease), zinc content and calcium saturation. A negative association was also observed between fruit viscosity and soil iron content.

4. Discussion

In the present study, soil bioindicators, available chemical elements and berry viscosity of grapevines from the Itata Valley were evaluated under contrasting agronomic management systems. The results showed that although no statistical differences were detected in pH or basal soil respiration among the evaluated vineyards, notable variations were observed in enzymatic activity and soil nutrient availability between treatments, highlighting clear contrasts between grapevines under organic and conventional management. These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating that management practices exert a strong influence on soil health and chemical properties [38]. Moreover, the rheological analysis of the berries revealed that the fitting models differed according to the type of agronomic management. The non-managed and conventionally managed grapevine (PA and CPA) differed from those managed organically (OCI and OCA). A similar trend was observed in apparent viscosity at a shear rate of 50 s−1, where PA and CPA showed lower variability and more homogeneous distributions compared with the organic treatments OCI and OCA. These results are relevant for the viticulture industry, which promotes the production of high-quality wines under site-specific conditions and management practices, in line with the concept of terroir [39,40]. Therefore, the findings of this study demonstrate that it is possible to modulate berry compositional quality through agronomic management and, indirectly, the bioactive compounds strongly associated with viscosity as evaluated in this research [41].

This study demonstrated that vineyard management can influence both the biological and chemical quality of the soil. Soil pH is considered one of the most restrictive factors affecting nutrient solubility and availability, as it supports the diversity and richness of agricultural systems [42]. Variations in pH ranges can either enable or limit species growth, development and overall ecosystem sustainability [43]. According to our results, Table 1 shows that the presence or absence of conventional or organic agricultural management, as well as the dynamics of nutrient availability and soil health development, depends on the origin of the nutrient sources incorporated into the soil and vineyard variety.

This is because the soil microbiome acts as a reservoir for the microbiota associated with grapevines and therefore contributes to the final sensory properties of wines [44,45]. Consequently, soil enzymatic activities also determine the abundance and diversity of microbial communities that provide soil health, nutrient availability and stability [46].

Regarding enzymatic behaviour, the treatments PA (non-managed) and CPA (conventional) of the País variety showed no significant differences in arylsulfatase, dehydrogenase, acid phosphatase or urease activities, although CPA tended to display equal or lower concentrations of these enzymes (Figure 2b–e). However, the soil nutrient profile of the País variety differed between PA and CPA, specifically showing higher levels of nitrate, ammonium and available nitrogen in CPA (Table 1). Thus, the CPA treatment is characterized by its proximity and association with nitrogen and available phosphorus sources (Figure 4), as well as by low urease activity and basal soil respiration (Figure 4). Conversely, exchangeable Mg, available S, and Zn decreased under conventional management (CPA) of the vineyard (Table 1). The reduction in exchangeable Mg may be attributed to higher nitrogen concentrations, since both elements compete for the cation exchange sites of the colloidal complex [47]. The higher N content may displace Mg from the exchange sites, enhancing its leaching potential [48].

In addition, the lower available sulphur concentration may be linked to the reduced arylsulfatase activity observed in CPA, although this was not statistically significant (Table 1; Figure 2b). This pattern is consistent with conventional agricultural management practices, which tend to limit microbial development and consequently the transformation of organic S into inorganic S [49]. In the case of Zn, conventional management (CPA) may decrease its availability through fixation with phosphorus and reduced microbial activity, which together diminish its solubility [50]. Both Zn and S, which were deficient in the soil, exhibited low association with the CPA treatment in the principal component analysis (Figure 4). However, Mg was positively associated with CPA (Figure 4). This may be due to the fact that, despite competition with nitrogen for active sites, the level of exchangeable Mg in the soil remains moderate, which is still beneficial for plant growth (Table 1; Figure 4).

In the case of organic management, soil pH (measured in water) showed noticeable variation, with values of 5.85 for OCI and 6.48 for OCA, corresponding to a difference of 0.63 (Table 1). This pattern is consistent with the stronger association between OCA and soil pH observed in the PCA (Figure 4). Treatment with a lower pH of 5.85 (OCI) exhibited reduced dehydrogenase and urease activity and a weaker association with these enzymes, whereas arylsulfatase and acid phosphatase activities were statistically similar and highly associated (Figure 2 and Figure 4). Dehydrogenase and urease are considered indicators of microbial activity, with an optimal pH range close to neutrality, between approximately 6.2 and 7.4 [51]. Consequently, OCA treatment, with a pH of 6.48, resulted in higher soil enzyme activity and a stronger association (Figure 2c and Figure 4). However, given that management between OCI and OCA is similar, grape varieties (Cinsault and Carmenere) are the source of variation. Grape variety can significantly influence soil enzyme activity, such as dehydrogenase and urease, and thus nutrient availability and mobility. Each variety differs in vigour, architecture, and depth of the root system, as well as in the amount and type of exudates it releases, which modifies the chemical and biological dynamics of the soil [52]. These variations affect processes such as mineralization and nutrient release, along with microbial activity, generating direct changes in the availability of elements essential for crop development.

Regarding soil chemistry, the OCI treatment (pH 5.85) showed higher aluminum saturation, which displaced exchangeable potassium and reduced both the base sum and the effective cation exchange capacity (Table 1; Figure 4). In addition, zinc and boron decreased and were not associated with the OCI treatment in the principal component analysis (Table 1; Figure 4). This behaviour is related to the fact that both micronutrients increase in solubility at pH values below 6 [53], which enhances competition with other cations such as Fe2+, Mn2+ and H+ [54]. Moreover, in soils with high organic matter content, these elements can form strong complexes with Al and Fe oxides or with organic acids, generating stable salts [55].

Sulphur concentration increased at lower pH in the OCI treatment (Table 1), which may be due to the greater affinity between Zn2+ and SO42−, leading to higher availability of Sulphur. This pattern was corroborated by the PCA shown in Figure 4 [56,57].

When comparing the four treatments, enzymatic activities in the CPA treatment tended to be lower, although not all cases were statistically significant (Figure 2b–e). Among the enzymatic activities that differed significantly from CPA were arylsulfatase (CPA < OCI), acid phosphatase (CPA < OCI = OCA), dehydrogenase, and urease (CPA < OCA) (Figure 2b–e). Soil dehydrogenase and urease activities, which indicate soil fertility and biological activity, were markedly higher in OCA (pH 6.48 in water) compared with all other treatments (Table 1; Figure 2b,e and Figure 4). This study showed that Carmenere had higher soil health indicators than Cinsault under the same management, confirming the effect of variety on soil biological properties [52]. For this reason, it is pertinent that future research deeper into the effect of grape variety, with varieties from the Itata Valley, on soil biological modulation.

Although higher concentrations of nitrogen were observed in CPA soils—both as nitrate and ammonium, as well as available nitrogen—the soil urease activity was lower (Table 1; Figure 2e and Figure 4). This is because the higher nitrogen availability in CPA depends on the conventional fertilization plan, deriving from external inputs rather than the natural biogeochemical nitrogen cycle. Consequently, the activity of soil bacteria, fungi, and yeasts becomes limited, resulting in dependency on external nitrogen sources [58,59].

Similarly, acid phosphatase activity was lower in CPA, even though the Olsen phosphorus concentration was higher in the chemical analysis and showed an inverse association (Table 1; Figure 2c and Figure 4). Acid phosphatase is an enzyme produced by soil microorganisms and plant roots through a negative feedback mechanism [60,61]. Its activity increases when the available phosphorus concentration in the soil is low. Therefore, acid phosphatase is synthesized to hydrolyze organic phosphorus into inorganic forms, making phosphorus available for plant uptake [62].

In general, soil basal respiration did not show significant differences among treatments (Figure 2a). Similarly, soil organic matter content did not vary across treatments (Table 1). This was confirmed by the weak relationship observed between basal respiration and organic matter in PA, CPA, and OCA soils (Figure 4). In particular, in the conventional treatment (CPA), herbicides were applied at the beginning of the season to control weeds; however, these applications were not carried out during the harvest stage (sampling time), which could have attenuated expected differences between treatments.

Vegetation cover in vineyard soils, particularly under rain-fed conditions, enhances soil water movement, moisture retention, temperature regulation, and overall rhizosphere microclimate, promoting the development of both micro- and macro-organisms [62]. Such conditions increase the diversity and richness of perennial species under less intensive management, as typically observed in vineyards with extensive organic farming systems [63]. However, plant diversity depends not only on vineyard ground cover but also on management practices such as mowing frequency, the use of mixed cover crops, the promotion of spontaneous vegetation, and/or chemical weed control [64,65]. These practices have also been reported to directly influence bud and fruit quality in wine grapevines [66].

Regarding the evaluation of berries, the Carreau model describes pseudoplastic fluids that exhibit high viscosity at rest and a progressive decrease in viscosity with increasing shear rate [67]. The shape of the curves suggests that PA and CPA samples contain resistant internal structures (such as fibres or colloidal particles) that gradually disorganize under flow [68]. This indicates a rheological behaviour typical of complex materials that flow more easily when agitated but remain resistant at rest. Such characteristics are suitable for applications where structural stability is required when the product is not being handled [69].

The Power Law model describes pseudoplastic materials whose viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate, without reaching a defined plateau [70]. The OCI and OCA treatments exhibited a more homogeneous and rapid fluid response as shear stress increased, suggesting lower internal structural content and greater fluidity even at low shear rates [71]. These materials are more suitable for formulations requiring immediate flow behaviour, such as functional beverages or liquid systems [72]. Although differences in responses were observed between management practices, it is possible that vine variety also acted as an additional source of variation. We acknowledge this limitation in our study, which could be adequately addressed in future research.

The higher viscosity observed in OCA and CPA could be attributed to a greater retention of phenolic compounds and organic acids, which enhance the structural cohesion of the fruit [73]. This behaviour is consistent with [74], who reported that interactions between polysaccharides and phenols strengthen the colloidal network, thereby increasing flow resistance. In this context, the relationship between rheological behaviour and antioxidant capacity could be considered a functional quality indicator with potential technological relevance.

PA and CPA exhibited a more resistant internal structure to flow, whereas OCI and OCA showed a more fluid and less structured behaviour. These findings may be related to the agronomic treatment applied to the vines or their variety and could be critical for selecting ingredients in the design of functional or structural food products in the future. However, the results are not conclusive regarding the relationship between the rheological behaviour of the pulp and vineyard management, since chemical composition data of the fruit were not available.

Viscosity was also associated with soil parameters such as pH, boron, zinc, and biological activity, which influence the synthesis of polysaccharides and phenolic compounds. According to Kim et al. (2022) [75] and Mrabet et al. (2024) [76], high-quality soils with strong biological fertility promote the formation of fruits with improved physical properties. Overall, these results reinforce the functional connection between soil quality and rheological properties, highlighting the value of organic management in improving fruit quality and sustainability of vineyards.

Nevertheless, it should be considered that varietal differences among the evaluated vines may have influenced both rheological results and soil responses under different agronomic managements. Therefore, future studies should maintain a single grape variety under contrasting management conditions to more precisely isolate the effect of the cropping system on fruit quality and soil dynamics.

5. Conclusions

PA and CPA exhibited a more resistant internal structure to flow, whereas OCI and OCA showed a more fluid and less structured behaviour. These findings may be linked to the agronomic management applied to the vines and could be relevant for selecting ingredients in the formulation of functional or structurally complex food products. However, the results are not conclusive regarding the relationship between the rheological behaviour of the pulp and vineyard management, as data on the chemical composition of the berries was not available.

Viscosity was also associated with soil parameters such as pH, boron, zinc, and biological activity—factors which influence the synthesis of polysaccharides and phenolic compounds. Overall, these results reinforce the functional linkage between soil quality and rheological behaviour, emphasizing the value of organic management in improving fruit quality and vineyard sustainability.

Nevertheless, varietal differences among the evaluated vines may have influenced both rheological properties and soil responses under the different management regimes. Therefore, future studies should maintain a single grape variety under contrasting management conditions to isolate the effects of cropping systems on fruit quality and soil dynamics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121518/s1, Table S1: Chemical analyses of reference fruit for each grape variety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.-P., M.B. and S.M.-B.; methodology, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B., M.J.-P., E.M.U.-I. and M.S.; software, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B. and M.J.-P.; validation, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B., M.J.-P. and E.M.U.-I.; formal analysis, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B., M.J.-P., E.M.U.-I. and M.S.; investigation, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B. and M.J.-P.; resources, M.J.-P. and M.S.; data curation, A.P.-P., M.B. and S.M.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B., M.J.-P. and E.M.U.-I.; writing—review and editing, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B., M.J.-P., E.M.U.-I. and M.S.; visualization, A.P.-P. and M.B.; supervision, A.P.-P. and M.B.; project administration, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B. and M.J.-P.; funding acquisition, A.P.-P., M.B., S.M.-B., M.J.-P. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Regional Government of Ñuble, Chile, program BID 40050601-0.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Víctor Castellón Campos for providing access to the vineyards and actively collaborating in the development of this study in the Itata Valley. Their support was essential for carrying out the sampling and obtaining agronomic information related to the evaluated management systems.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). State of the World Vine and Wine Sector in 2024; OIV: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/2025-04/OIV-State_of_the_World_Vine-and-Wine-Sector-in-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Lacoste, P.; Aranda, M.; Matamala, J.; Premat, E.; Quinteros, K.; Soto, N.; Gaete, J.; Rivas, J.; Solar, M. Pisada de la uva y lagar tradicional en Chile y Argentina (1550–1850). Atenea 2011, 503, 39–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarricolea, P.; Herrera-Ossandon, M.; Meseguer-Ruiz, Ó. Climatic regionalisation of continental Chile. J. Maps 2017, 13, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, M.; Salazar, O.; Seguel, O.; Luzio, W. Main Features of Chilean Soils. In The Soils of Chile; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 25–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Roby, J.-P.; De Rességuier, L. Soil-related terroir factors: A review. OENO One 2018, 52, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez Henríquez, B.; Eugenia Cid-Aguayo, B.; Oliveros, V.; Henríquez Ramírez, A.A.; Letelier, E.; Bastías-Mercado, F.; Vanhulst, J. Wineries in the Itata and Cauquenes Valleys: Local flavors, multiple dispossessions and care for the commons as pluriverses for (Neo)peasant climate resilience. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2024, 7, 862–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unc, A.; Eshel, G.; Unc, G.A.; Doniger, T.; Sherman, C.; Leikin, M.; Steinberger, Y. Vineyard soil microbial community under conventional, sustainable and organic management practices in a Mediterranean climate. Soil Res. 2021, 59, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Salvi, L.; Sbraci, S.; Storchi, P.; Mattii, G.B. Sustainable viticulture: Effects of soil management in Vitis vinifera. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederberg, P.; Gustafsson, J.-G.; Mårtensson, A. Potential for organic Chilean wine. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B-Soil Plant Sci. 2009, 59, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chausali, N.; Saxena, J. Conventional Versus Organic Farming: Nutrient Status. In Advances in Organic Farming; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaller, J.G.; Cantelmo, C.; Santos, G.D.; Muther, S.; Gruber, E.; Pallua, P.; Mandl, K.; Friedrich, B.; Hofstetter, I.; Schmuckenschlager, B.; et al. Herbicides in vineyards reduce grapevine root mycorrhization and alter soil microorganisms and the nutrient composition in grapevine roots, leaves, xylem sap and grape juice. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 23215–23226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivcev, B.; Sivcev, I.; Rankovic-Vasic, Z. Natural process and use of natural matters in organic viticulture. J. Agric. Sci. Belgrade 2010, 55, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colautti, A.; Civilini, M.; Contin, M.; Celotti, E.; Iacumin, L. Organic vs. conventional: Impact of cultivation treatments on the soil microbiota in the vineyard. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1242267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, R.R.; Ribeiro Sanches, M.A.; Machado de Castilhos, M.B.; Cantú-Lozano, D.; Telis-Romero, J. Determination of the rheological behavior and thermophysical properties of malbec grape juice concentrates (Vitis vinifera). Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L. Soil health characteristics. Open Access Gov. 2023, 41, 398–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudicina, V.A.; Dennis, P.G.; Palazzolo, E.; Badalucco, L. Key biochemical attributes to assess soil ecosystem sustainability. In Environmental Protection Strategies for Sustainable Development; Malik, A., Grohmann, E., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 193–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, I.P.; Hale, C. Healthy soils for productivity and sustainable development in agriculture. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1018, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.D.; Toujaguez, R.; Alves, E.S.D.A.; Silva, P.C.V.D.; Montaldo, Y.C.; Santos, T.M.C.D.; Balbino, R.D.S.; Ramalho, V.R.R.D.A.R. Enzymatic activity of soil microbiota in agroecological systems: A review of its relevance for nutrient cycling. Adv. Res. 2025, 26, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías-Gallardo, F.; Quiñones-Muñoz, T.A.; Miranda-Avilés, R.; Ramírez-Santoyo, L.F.; Zanor, G.A.; Ozuna, C. Impact of organic agriculture on the quality of grapes (Syrah and tempranillo) harvested in Guanajuato, Mexico: Relationship between soil elemental profile and grape bioactive properties. Agriculture 2025, 15, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maioli, F.; Picchi, M.; Millarini, V.; Domizio, P.; Scozzafava, G.; Zanoni, B.; Canuti, V. A methodological approach to assess the effect of organic, biodynamic, and conventional production processes on the intrinsic and perceived quality of a typical wine: The case study of chianti docg. Foods 2021, 10, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguna, L.; Bartolomé, B.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Mouthfeel perception of wine: Oral physiology, components and instrumental characterization. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, O.P.; Lazo, A.; Parajuli, B.; Nepal, J. Fostering microbial activity and diversity in agricultural systems: Adopting better management practices and strategies: Part 1. CSA News 2024, 69, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional de Riego; Centro de Información de Recursos Naturales (CIREN). Estudios de Suelos: Proyecto Itata, Etapa 1 (Informe); Biblioteca Digital CIREN: Santiago, Chile, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias (INIA). Red Agrometeorológica INIA; INIA: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.; Martins, V.; Gerós, H. From the vineyard soil to the grape berry surface: Unravelling the dynamics of the microbial terroir. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 374, 109145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alef, K. Dehydrogenase Activity. In Methods in Applied Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry; Alef, K., Nannipieri, P., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1995; pp. 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- Nannipieri, P.; Ceccanti, B.; Cervelli, S.; Matarese, E. Extraction of phosphatase, urease, proteases, organic carbon, and nitrogen from soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseby, D.C.; Lynch, J.M. Rhizosphere soil enzymes as indicators of perturbations caused by enzyme substrate addition and inoculation of a genetically modified strain of Pseudomonas fluorescens on wheat seed. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1997, 29, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Hernandez, T.; Costa, F. Potential use of dehydrogenase activity as an index of microbial activity in degraded soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1997, 28, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabai, M.A.; Bremner, J.M. Arylsulfatase activity of soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1970, 34, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadzawka, A.; Carrasco, M.; Grez, R.; Mora, G.; de la Luz, M.; Flores, H.; Neaman, A. Métodos de Análisis Recomendados Para los Suelos de Chile; Revisión 2006. Serie Actas (Spanish); Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias: Santiago, Chile, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Trávnícek, P.; Burg, P.; Krakowiak-Bal, A.; Junga, P.; Vitez, T.; Ziemianczyk, U. Study of rheological behaviour of wines. Int. Agrophysics 2016, 30, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ah-Hen, K.; Fuenzalida, C.; Hess, S.; Contreras, A.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Lemus-Mondaca, R. Antioxidant capacity and total phenolic compounds of twelve selected potato landrace clones grown in southern Chile. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 72, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MathWorks. MATLAB (Version R2024a) [Computer Software]. The MathWorks, Inc. 2024. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Balzarini, M.G.; González, L.; Tablada, M.; Casanoves, F.; Di Rienzo, J.A.; Robledo, C.W. InfoStat: Manual del Usuario (Versión 2008); Editorial Brujas: Córdoba, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Versión 4.X). R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2024. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Amaral, H.F.; Schwan-Estrada, K.R.F.; Sena, J.O.A.D.; Colozzi-Filho, A.; Andrade, D.S. Seasonal variations in soil chemical and microbial indicators under conventional and organic vineyards. Acta Sci. Agron. 2022, 45, e56158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Seguin, G. The concept of terroir in viticulture. J. Wine Res. 2006, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clingeleffer, P. Terroir: The application of an old concept in modern viticulture. In Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, O.; Karakus, S.; Ates, F.; Daler, S.; Hatterman-Valenti, H. Enhancing Royal grape quality through a three-year investigation of soil management practices and organic amendments on berry biochemistry. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neina, D. The Role of Soil pH in Plant Nutrition and Soil Remediation. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019, 2019, 5794869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusmayadi, G.; Safruddin, S. Effect of Soil pH Variation on Peanut Plant Growth. West Sci. Agro 2024, 2, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarraonaindia, I.; Owens, S.M.; Weisenhorn, P.; West, K.; Hampton-Marcell, J.; Lax, S.; Bokulich, N.A.; Mills, D.A.; Martin, G.; Taghavi, S.; et al. The Soil Microbiome Influences Grapevine-Associated Microbiota. mBio 2015, 6, e02527-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, I.; Zarraonaindia, I.; Perisin, M.; Palacios, A.; Acedo, A. From Vineyard Soil to Wine Fermentation: Microbiome Approximations to Explain the “terroir” Concept. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamir, E.; Kangabam, R.D.; Borah, K.; Tamuly, A.; Deka Boruah, H.P.; Silla, Y. Role of Soil Microbiome and Enzyme Activities in Plant Growth Nutrition and Ecological Restoration of Soil Health. In Microbes and Enzymes in Soil Health and Bioremediation; Kumar, A., Sharma, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 99–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, R. Effects of different ammonium nitrate levels on the amounts of exchangeable soil magnesium and applied magnesium in eight mineral soils. Agric. Food Sci. 1984, 56, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.D.; Smethurst, P.J. Base cation availability and leaching after nitrogen fertilisation of a eucalypt plantation. Soil Res. 2008, 46, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Saha, S.; Roy, P.D.; Padhan, D.; Pati, S.; Hazra, G.C. Microbial Transformation of Sulphur: An Approach to Combat the Sulphur Deficiencies in Agricultural Soils. In Role of Rhizospheric Microbes in Soil; Meena, V.S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Srivastava, S.; Goyal, N.; Walia, S. Behavior of zinc in soils and recent advances on strategies for ameliorating zinc phyto-toxicity. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2024, 220, 105676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Sun, B.; Wei, Y.; Xu, N.; Zhang, S.; Gu, L.; Bai, Z. Grape Cultivar Features Differentiate the Grape Rhizosphere Microbiota. Plants 2022, 11, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, N.; Singh, D. Enzymes in Relation to Soil Biological Properties and Sustainability. In Sustainable Management of Soil and Environment; Meena, R.S., Kumar, S., Bohra, J.S., Jat, M.L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Nisab, C.P.; Ghosh, G.K.; Sahu, M. Available zinc status in relation to soil properties in some red and lateritic soils of Birbhum district, west Bengal, India. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2019, 8, 1764–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnasamy, R.; Krishnamoorthy, K. Cationic interferences on zinc adsorption. Soil Res. 1991, 29, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S.S.; Naresh, R.K.; Mandal, A.; Singh, R.; Dhaliwal, M.K. Dynamics and transformations of micronutrients in agricultural soils as influenced by organic matter build-up: A review. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2019, 1–2, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, F.N.; Sönmez, O. The effect of different sulphur sources applied at various rates on soil ph. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 13, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khampuang, K.; Chaiwong, N.; Yazici, A.; Demirer, B.; Cakmak, I.; Prom-U-Thai, C. Effect of sulfur fertilization on productivity and grain zinc yield of rice grown under low and adequate soil zinc applications. Rice Sci. 2023, 30, 632–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. Fungi and nitrogen cycle: Symbiotic relationship, mechanism and significance. In Soil Nitrogen Ecology; Cruz, C., Vishwakarma, K., Choudhary, D.K., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 62, pp. 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.C.; Grenni, P.; Onet, C.; Onet, A. Fertilization and soil microbial community: A review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadouria, J.; Giri, J. Purple acid phosphatases: Roles in phosphate utilization and new emerging functions. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannipieri, P.; Giagnoni, L.; Landi, L.; Renella, G. Role of phosphatase enzymes in soil. In Phosphorus in Action; Bünemann, E., Oberson, A., Frossard, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 26, pp. 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffard, B.; Winter, S.; Guidoni, S.; Nicolai, A.; Castaldini, M.; Cluzeau, D.; Coll, P.; Cortet, J.; Le Cadre, E.; d’Errico, G.; et al. Vineyard Management and Its Impacts on Soil Biodiversity, Functions, and Ecosystem Services. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 850272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, J.; Marini, L.; Paoletti, M.G. Organic farming benefits local plant diversity in vineyard farms located in intensive agricultural landscapes. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguankeo, P.P.; León, R.G. Weed management practices determine plant and arthropod diversity and seed predation in vineyards. Weed Res. 2011, 51, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, J.C.; Louw, P.J.E.; Agenbag, G.A. Cover crop management in a sauvignon blanc/ramsey vineyard in the semi-arid olifants river valley, South Africa. 2. Effect of different cover crops and cover crop management practices on grapevine performance. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2016, 28, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, J.C.; Louw, P.J.E.; Agenbag, G.A. Cover crop management in a chardonnay/99 richter vineyard in the coastal region, South Africa. 2. Effect of different cover crops and cover crop management practices on grapevine performance. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2017, 27, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, P.; Williams, K.A.; Angers, P.; Pedneault, K. Changes in the flavan-3-ol and polysaccharide content during the fermentation of Vitis vinifera Cabernet-Sauvignon and cold-hardy Vitis varieties Frontenac and Frontenac blanc. OENO One 2021, 55, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangon, M.; Marassi, V.; Mattivi, F.; Marangon, C.M.; Moio, L.; Roda, B.; Rolle, L.; Ugliano, M.; Versari, A.; Zanella, S.; et al. The role of protein-phenolic interactions in the formation of red wine colloidal particles: This is an original research article submitted in cooperation with Macrowine 2025. OENO One 2025, 59, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O. Structural Rheology in the Development and Study of Complex Polymer Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çevik, M.; Tezcan, D.; Sabancı, S.; İçier, F. Changes in rheological properties of Koruk (unripe grape) juice concentrates during vacuum evaporation. Akad. Gıda 2016, 14, 322–332. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Lapuente, L.; Guadalupe, Z.; Ayestarán, B. Properties of Wine Polysaccharides; IntechOpen: Houston, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castilhos, M.B.M.; Betiol, L.F.L.; Carvalho, G.R.; Telis-Romero, J. Experimental study of physical and rheological properties of grape juice using different temperatures and concentrations. Part I: Cabernet Sauvignon. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jančářová, I.; Jančář, L.; Náplavová, A.; Kubáň, V. Changes of organic acids and phenolic compounds contents in grapevine berries during their ripening. Open Chem. 2013, 11, 1575–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Wu, C.; Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Ma, Y.; Li, C. Textural characteristic, antioxidant activity, sugar, organic acid, and phenolic profiles of 10 promising jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) selections. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, C1218–C1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L.; Lee, M.; Chung, K.-H. Soil and leaf chemical properties and fruit quality in kiwifruit orchard. Korean J. Environ. Agric. 2022, 41, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, O.; Asbai, Z.; Hadidi, M.; Bahlaouan, B.; Tesse, R.; ElAntri, S.; Boutaleb, N. Fruit quality of ‘Stanley’ plums based on soil composition across diverse agro-ecological zones of Morocco. Comun. Sci. 2024, 16, e4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).