Abstract

Powdery mildew poses a significant threat to watermelon production. The development of disease-resistant varieties through gene editing represents a major focus in current breeding research. In this study, we identified an MLO family gene in watermelon, denoted by ClMLO5b, which is phylogenetically closely related to cucumber CsaMLO8 and melon CmMLO5. Homology modeling revealed high conservation of the three-dimensional protein structures among these orthologs. Expression analysis demonstrated that ClMLO5b is significantly up-regulated upon powdery mildew infection, and the protein localizes to the plasma membrane. To validate its function, we first employed an Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation system to rapidly verify the editing efficiency of two CRISPR/Cas9 targets designed for ClMLO5b. Subsequently, stable transgenic watermelon plants were generated via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation, and a mutant line with homozygous substitutions at target site 2 was obtained. Disease resistance assays showed that, compared to wild-type plants, the Clmlo5b exhibited strongly inhibited mycelial growth, significantly reduced disease severity, and a substantial decrease in spore production after inoculation with powdery mildew. Our findings confirm that ClMLO5b is a key susceptibility gene in watermelon and provide both a promising genetic target and valuable breeding material for developing powdery mildew-resistant watermelon varieties.

1. Introduction

Powdery mildew (PM), a widespread fungal disease, severely affects the yield and quality of watermelon (Citrullus lanatus L.) and other cucurbit crops. This disease is globally distributed, particularly in temperate and subtropical regions, with Golovinomyces cichoracearum and Podosphaera xanthii being the primary causative pathogens [1,2]. Typical symptoms include the appearance of white, powdery coatings on leaf surfaces, leading to leaf chlorosis, premature senescence, and impaired fruit development [3].

Recent advances in molecular biology have significantly accelerated research on powdery mildew resistance. Studies indicate that resistance to this disease is governed not by single genes but complex polygenic networks [4,5,6]. Among the key players, the MLO (Mildew Locus O) gene family has garnered increasing attention. Initially identified in barley, loss-of-function mutations in MLO genes confer enhanced resistance to powdery mildew [7]. Subsequent research has revealed that MLO genes participate in powdery mildew susceptibility across diverse plant species. MLO proteins are plant-specific integral membrane proteins with seven transmembrane domains, structurally resembling animal G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and containing a calmodulin-binding domain [8,9]. Evidence suggests that certain MLO family members act as susceptibility factors, and their disruption can lead to broad-spectrum resistance [10,11]. For instance, mutations in HvMLO confer effective resistance in barley [7]. Similarly, loss of MLO function has been shown to enhance resistance in tomato [12], pea [13,14], pepper [15], and wheat [16], highlighting the conserved role of these genes in modulating plant-pathogen interactions.

In cucurbit crops, members of the MLO gene family play a conserved role in regulating powdery mildew susceptibility. Iovieno conducted a comprehensive analysis of the MLO family in melon (Cucumis melo), watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), and zucchini (Cucurbita pepo), identifying 16, 14, and 18 MLO homologs, respectively. Through phylogenetic and expression analyses, several candidate susceptibility genes were identified, all of which were significantly upregulated upon powdery mildew infection [17]. In watermelon, strong induction of ClMLO12 was observed at 9 and 24 h post-inoculation (hpi), suggesting its role as a pathogen-responsive susceptibility gene [17]. In the original study, the gene was designated ClMLO12 (Gene ID: Cla020573) in the Watermelon (97103) v1 genome. To maintain consistency with the updated genome version (v2) and reflect its chromosomal location, we refer to it here as ClMLO5b (Gene ID: Cla97C05G102540). This reannotation aligns its nomenclature with its orthologs (CmMLO5, CsaMLO8) and phylogenetic clade. This gene is orthologous to CmMLO5 (MELO3C012438) in melon, and both belong to phylogenetic clade V, which contains well-characterized MLO susceptibility genes across dicot species [17,18]. Functional evidence further supports the role of these clade V genes in powdery mildew susceptibility. In melon, a C-to-T single-nucleotide mutation in CmMLO5 results in a Thr-to-Ile substitution, leading to loss of function and enhanced resistance [19]. Similarly, heterologous expression of the cucumber ortholog CsaMLO8 in Arabidopsis and tomato increased their susceptibility to powdery mildew [20]. More recently, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of CsaMLO8 in susceptible cucumber lines has successfully generated resistant mutants, providing direct genetic evidence of its role as a susceptibility factor [21,22,23].

Gene editing technologies, particularly the CRISPR/Cas9 system, have significantly accelerated watermelon breeding by enabling precise and efficient gene knockout, replacement, or insertion. The first successful application of CRISPR/Cas9 in watermelon was reported by Tian [24], demonstrating targeted gene mutagenesis. Subsequently, Wang utilized this system to mutate the ClBG1 gene, investigating its role in seed size and germination [25]. These pioneering studies established the feasibility of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in watermelon. A major breakthrough was achieved by Feng [26], who developed a chimeric ClGRF4-GIF1 system that enabled highly efficient genetic transformation and gene editing with rates up to 67.27%, independent of genotype constraints. Building on this optimized system, researchers have expanded applications to develop haploid inducer lines and seedless watermelon varieties through targeted gene editing [27,28,29,30]. Additionally, editing of the ClWIP1 gene has yielded gynoecious watermelon lines [31]. The mature application of the above research methods in watermelon genetic transformation allows us to directly perform functional verification of candidate susceptibility genes in watermelon (such as ClMLO5b). More importantly, these advances provide a theoretical foundation and practical tools for increasing yield and breeding high-quality watermelon varieties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The powdery mildew-susceptible watermelon cultivar ‘812’ used in this study was provided by the Molecular Genetics and Breeding Laboratory for Watermelon and Melon at Northeast Agricultural University. The method for powdery mildew isolation and inoculation followed the protocol described by Yadav et al. [32].

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

MLO protein sequences from different species were obtained from the following databases: cucumber (http://cucurbitgenomics.org/organism/2/, accessed on 11 December 2025), melon (http://cucurbitgenomics.org/organism/18, accessed on 11 December 2025), and watermelon (http://cucurbitgenomics.org/organism/21, accessed on 11 December 2025). A total of 17 protein IDs are provided in Table S1. Multiple amino acid sequences of the MLO protein family were aligned using ClustalW with default parameters. Following alignment, the poorly aligned terminal regions of the sequences were manually trimmed to enhance alignment accuracy. Subsequently, a Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 11 based on the trimmed alignment, employing the Poisson correction model and a complete deletion treatment for gaps. Branch reliability was assessed by 1000 bootstrap replicates.

2.3. Subcellular Localization

Using watermelon cDNA as a template, the homologous arms of the ClMLO5b gene were amplified by PCR via homologous recombination. The pCAMBIA1300-sGFP plasmid was digested with restriction enzymes and subsequently recombined with the amplified fragment to generate the 35S::ClMLO5b-sGFP fusion construct. The resulting recombinant reaction system was transformed into E. coli DH5α chemically competent cells (WEIDI, China), and positive clones were identified by sequencing. Plasmids extracted from these clones were then introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens competent cells (WEIDI, China).

Suspensions of Agrobacterium carrying either the 35S::ClMLO5b-sGFP expression vector or a control vector (35S::sGFP) were transiently injected into leaves of 4-week-old tobacco plants (a well-established heterologous system for efficient transient expression). After incubation in darkness at 23 °C for two days, the samples were observed and imaged using a laser scanning confocal microscope (FV3000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with 488 nm excitation.

2.4. Vector Construction and Genetic Transformation of Watermelon

Based on the sequence of ClMLO5b, two gene editing targets were designed. Using the backbone of pKSE402 vector and the pCBC-DT1T2 intermediate vector, specific primers for both targets were constructed via homologous recombination (Supplementary Table S2). The primer pairs were amplified using pCBC-DT1T2 as the template. The resulting PCR products were ligated into the BsaI-digested pKSE402 vector by incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. The ligation product was then transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells and plated on LB solid medium supplemented with kanamycin, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 12–16 h. Positive single colonies identified by PCR and sequencing were selected for plasmid extraction, which was subsequently transformed into the appropriate Agrobacterium strain.

For plant transformation, full and uniform watermelon seeds were surface-sterilized and germinated for two days in the dark on germination medium. For stable transformation mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 and Agrobacterium rhizogenes K599, cotyledonary nodes from the resulting seedlings were excised and used for infection. A single colony of Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 harboring the target construct—or A. rhizogenes K599 for editing efficiency validation—was inoculated in LB medium. When the bacterial culture reached an OD600 = 0.6–0.8, the cells were harvested and used for explant inoculation. The prepared explants were immersed in the diluted Agrobacterium suspension for 5–10 min, then transferred to co-culture medium and kept in the dark at 25 °C for three days.

After co-culture, transient transformation was checked under a fluorescence microscope. The explants were then transferred to selection medium and cultured under light to induce callus formation—or hairy roots in the case of A. rhizogenes. One to two weeks post-transformation, fluorescent hairy roots or tissues were collected under a fluorescence microscope. Genomic DNA was extracted from these tissues, and target regions were amplified by PCR using specifically designed primers, followed by sequencing of the products.

When fluorescent shoots reached 1–2 cm in height, they were excised and transferred to rooting medium. During subculture, surrounding non-transformed leaves and competing shoots were carefully removed to maintain dominant growth of the transformed shoots. Rooted plantlets were transplanted into pots containing sterilized soil and grown in a controlled greenhouse under a 28 °C/23 °C day/night cycle. Once a robust root system had developed, the plants were transferred to the greenhouse (26 °C under a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle) for final establishment.

2.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Gene-specific primers for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) were designed based on the sequence of ClMLO5b (Supplementary Table S2). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SYBR Green PCR master mix (TransGen, Beijing, China) and QTOWER (Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany). Qualified cDNA samples were used as templates, with each sample analyzed in three biological and three technical replicates. The watermelon ClACTIN gene was used as the internal control in the analysis [33]. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. qPCR thermal cycling conditions are shown in Supplementary Table S4.

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscope

Leaves from both wild-type (WT) and Clmlo5b watermelon seedlings were collected at 0 and 72 hpi with a powdery mildew spore suspension. Leaf segments (2 × 5 mm) were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (pH 6.8) at 4 °C for over 1.5 h, followed by three rinses with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8; 7 min each). Dehydration was performed using a graded ethanol series, with contents of 50%, 70%, 90% (7 min each), and two changes of 100% ethanol (7 min each). The samples were then treated with a 1:1 mixture of ethanol and tert-butanol, followed by two exchanges of pure tert-butanol (15 min each). After freezing at –20 °C for 30 min, the samples were dried in an ES-2030 freeze dryer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) for approximately 4 h. Finally, the specimens were mounted on stubs with the adaxial surface facing upward, sputter-coated with a 10–15 nm metal layer, and stored in a desiccator until SEM observation.

2.7. Physiological Observation

Leaves from both WT and mutant plants inoculated with spore suspension were collected at 0, 24 h and 6 days post-inoculation. The samples were stained with 0.067 mg/mL trypan blue solution (Solarbio, Beijing, China), boiled for 10–15 min, and naturally cooled before being destained with chloral hydrate. The stained leaves were preserved in 50% glycerol and observed under a microscope (NIKON DS-RI2, Tokyo, Japan). Disease severity was assessed according to the melon powdery mildew grading standard [34] using a 0–4 scale: 0 = no symptoms; 1 = <25% leaf area covered; 2 = 25–50%; 3 = 50–75%; 4 = >75%. The disease index (PDI) was calculated as: PDI = [Σ(disease ratings)/(number of plants × maximum rating)] × 100 [35]. Susceptibility was further quantified by counting conidiophores from approximately three randomly selected colonies per infected leaf using a hemocytometer under an inverted microscope (DMiL, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.8. Statistical Data Analysis

All experiments included three independent biological replicates. Data were recorded using Microsoft Excel 2016 and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 8.0.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Genes Associated with Resistance to Powdery Mildew in Watermelon

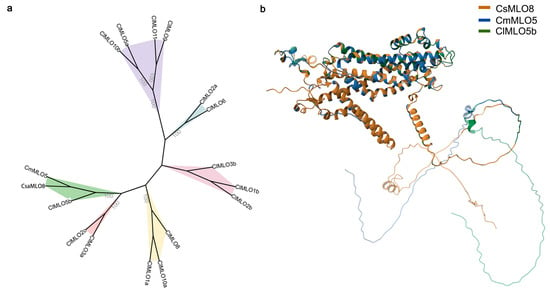

To identify MLO genes involved in powdery mildew resistance regulation in watermelon, we performed a phylogenetic analysis using reported PM-resistant MLO genes from cucumber (CsaMLO8) and melon (CmMLO5) as references. A BLAST search against the watermelon reference genome using conserved domains of CsaMLO8 and CmMLO5 revealed highest similarity with Cla97C05G102540 (annotated as MLO-like protein) on chromosome 5. Subsequent genome-wide screening identified 15 MLO family members in watermelon. These genes, together with CsaMLO8 and CmMLO5, were used to construct a phylogenetic tree. The watermelon MLO genes were systematically named according to their physical locations (5′ to 3′) on respective chromosomes (Supplementary Table S3). Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that ClMLO5b (Cla97C05G102540) clusters within the same evolutionary clade as CsaMLO8 and CmMLO5, indicating their close phylogenetic relationship (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Analysis of powdery mildew resistance-associated MLO Genes in Cucurbits. (a) Phylogenetic tree illustrating the evolutionary relationships among selected cucurbit MLO proteins. Numbers at branches represent node support values. (b) Three-dimensional structural models of representative cucurbit MLO proteins, with colors distinguishing different proteins: CsMLO8 (brown), CmMLO5 (blue), and ClMLO5b (green).

Using the homology modeling tool available on the Swiss-Model platform (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/, accessed on 11 December 2025), we generated three-dimensional structural models for the MLO proteins CsMLO8, CmMLO5, and ClMLO5b. Structural alignment performed with PDB-based comparison tools revealed high structural conservation among the three proteins (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure 1b). When CsMLO8 was used as the reference structure, the alignment with CmMLO5 showed a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 1.34 Å and a template modeling score (TM-score) of 0.80, with 95% sequence identity. A total of 458 amino acid residues were aligned, and the model covered all 533 residues of CmMLO5, indicating high model completeness. Similarly, alignment of ClMLO5b with CsMLO8 yielded an RMSD of 1.27 Å and a TM-score of 0.76, with 435 residues aligned and a full coverage of 508 residues in the model. The reference model of CsMLO8 contained 574 residues, all included in the modeling process without structural gaps. All three protein structures showed RMSD values below 1.5 Å and TM-scores above 0.75, indicating strong conservation of the tertiary structure backbone, a hallmark of homologous proteins (Supplementary Table S3). Spatial superposition of Cα atoms further illustrated that the core structures—particularly the transmembrane helices and conserved intracellular loops—were nearly identical among the three proteins (Figure 1b). Minor structural variations were mainly localized to disordered regions at the N- and C-termini and certain extracellular loops, which may reflect functional divergence among species.

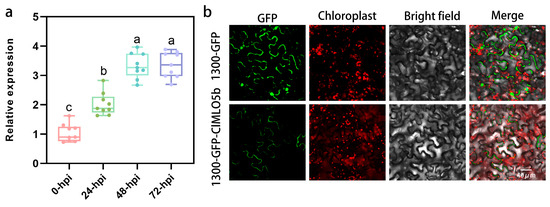

3.2. Analysis of ClMLO5b Expression Patterns

To characterize the spatiotemporal expression pattern of ClMLO5b in response to powdery mildew infection, we collected leaf samples from susceptible watermelon plants at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hpi and analyzed transcript levels using quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 2a). Relative to the 0 hpi control, ClMLO5b expression was significantly up-regulated at 24 hpi and continued to increase until 48 hpi, after which it stabilized. These results demonstrate that ClMLO5b is responsive to powdery mildew infection at an early stage, showing significant induction at 24 hpi. Subcellular localization analysis further showed that ClMLO5b is specifically localized to the plasma membrane (Figure 2b), consistent with previous findings on MLO protein localization and their role in powdery mildew susceptibility in cucumber and melon.

Figure 2.

Expression analysis of ClMLO5b. (a) Box plot showing the relative expression levels of ClMLO5b at different time points (0, 24, 48, and 72 h post-inoculation). Data analysis employed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) combined with Tukey’s post hoc test. Different letters (a, b, c) indicate statistically significant differences. (b) Confocal microscopy images showing the subcellular localization of 1300-GFP (control) and 1300-GFP-ClMLO5b fusion protein. From left to right: GFP signal (green), chloroplast autofluorescence (red), bright-field image, and merged channels. Scale bar: 40 μm.

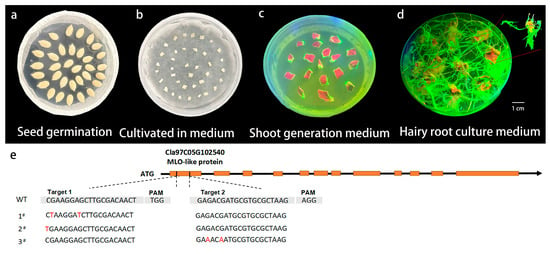

3.3. Feasibility Assessment of Target Site Detection in Agrobacterium-Mediated Watermelon Transformation Technology

A CRISPR/Cas9 editing vector targeting ClMLO5b was constructed based on its coding sequence, using cDNA from powdery mildew-susceptible watermelon as template. To validate targeting efficiency, we employed an Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root transformation system. The transformation procedure (Figure 3a–e) involved removing the seed coat and germinating seeds in darkness (Figure 3a); infecting cotyledon explants prepared according to Feng et al. [26] (Figure 3b); co-culturing at 25 °C for 3 days; decontaminating with sterile water; and transferring to MS selection medium (Figure 3c). Genomic DNA was extracted from emerging adventitious roots (Figure 3d) and target regions were amplified using specific primers (Supplementary Table S2) for sequencing analysis.

Figure 3.

Validation of target sites for ClMLO5b gene editing and plant tissue culture process. (a–d) Key stages of the plant tissue culture process. Scale bar: 1 cm. (e) Schematic representation of the gene editing targets, showing the structure of Cla97C05G102540 (MLO-like protein) with exons (orange boxes) and introns (black lines). Sequencing chromatograms of the wild-type (WT) and three mutant lines (1#, 2#, 3#) are displayed, with the PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif) sequence highlighted by dashed lines and mutation sites indicated in red.

Sequencing results revealed successful mutagenesis at both target sites: Explant 1# showed two point mutations in Target 1 (G → T at positions 2 and 8); Explant 2# had one point mutation in Target 1 (C → T at position 1); Explant 3# contained two point mutations in Target 2 (G → A at positions 3 and 6). These results confirm the effectiveness of both designed targets and demonstrate successful gene editing in watermelon adventitious roots using this hairy root transformation system.

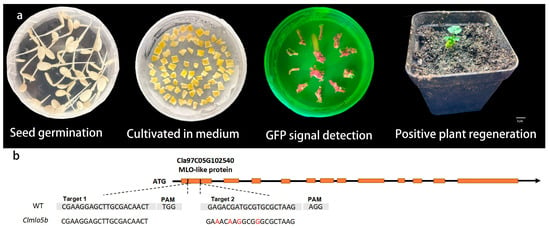

3.4. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genetic Transformation of Watermelon Targeting ClMLO5b

To generate Clmlo5b gene-edited mutants, we performed stable genetic transformation of watermelon via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated method. The overall transformation and selection procedure is summarized in Figure 4a, which includes key steps from seed germination and explant preparation to preliminary screening of transformation events using GFP fluorescence, and finally the acquisition of positive regenerated plantlets followed by greenhouse acclimatization. Through self-pollination of T0 plants and segregation analysis of the progeny, we successfully isolated a Clmlo5b line carrying homozygous edits in the T1 generation. Deep sequencing of the target site confirmed that the mutant contains four nucleotide substitutions at target site 2: G → A at position 3, G → A at position 6, T → G at position 8, and T → G at position 12 (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genetic transformation of ClMLO5b in watermelon. (a) Key stages of the transformation process (from left to right): seed germination, culture on medium, GFP signal detection, and successfully acclimatized positive plant. Scale bar: 1 cm. (b) Schematic of the gene editing target site, showing the structure of Cla97C05G102540 (encoding an MLO-like protein) with exons (orange boxes) and introns (black line). Sequencing results of the wild-type (WT) and the Clmlo5b mutant are aligned, with the PAM (protospacer adjacent motif) sequence and mutation sites highlighted in red.

3.5. Analysis of Disease Resistance in Clmlo5b

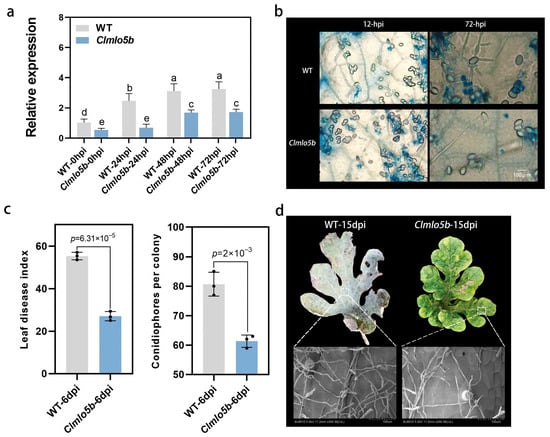

We first measured the expression level of the Clmlo5b gene in the Clmlo5b. The results showed a significant reduction in its transcript abundance compared to the WT. Following powdery mildew inoculation, expression of Clmlo5b in the mutant began to increase markedly at 48 hpi, though this induction was delayed relative to the WT (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Disease resistance analysis of Clmlo5b mutant. (a) Relative expression levels of Clmlo5b in wild-type (WT) and Clmlo5b at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h post-inoculation. Data analysis employed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) combined with Tukey’s post hoc test. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences. (b) Trypan blue-stained leaf sections of WT and Clmlo5b at 12 and 72 hpi. Scale bar: 100 μm. (c) Disease index (left) and number of conidia per colony (right) in WT and mutant plants at 6 dpi. Statistical significance (p-values) is indicated. (d) Scanning electron microscopy images of leaf surfaces from WT and Clmlo5b at 15 dpi. Scale bar: 20 μm.

To further investigate this phenotype, we monitored the fungal infection process by trypan blue staining at 12 and 72 hpi. At 12 hpi, no significant differences were observed between the mutant and WT in terms of conidial attachment, germination, or germ tube formation. By 72 hpi, however, WT plants showed fully developed appressoria with extensive hyphal growth into host tissues, indicating successful infection. In contrast, fungal development in the Clmlo5b was notably delayed, with only fine filamentous structures emerging from the appressoria (Figure 5b), demonstrating enhanced resistance to powdery mildew.

At 6 days post-inoculation (dpi), both the disease index and the number of conidia per colony were significantly lower in the Clmlo5b than in the WT (Figure 5c), further confirming its resistant phenotype.

Scanning electron microscopy at 15 dpi revealed markedly less hyphal coverage on leaves of the Clmlo5b compared to the WT, which exhibited dense fungal mycelia accompanied by leaf chlorosis and withering. In contrast, fungal growth on mutant leaves remained sparse (Figure 5d), indicating a strong suppression of hyphal development and spread. Collectively, these results demonstrate that ClMLO5b plays a critical role in watermelon immunity against powdery mildew.

4. Discussion

Phylogenetic studies of the MLO gene family reveal that PM-associated MLO genes are clustered in clade IV in monocots, while dicot susceptibility (S) genes predominantly reside in clade V. Members from other clades (I–III and VI) have not been conclusively linked to susceptibility [8,20]. In cucurbits, MLO family members are distributed across six major clades (I–VI), consistent with phylogenetic patterns observed in Arabidopsis and monocot species [8,36]. Within this family, clade V has been strongly implicated in PM susceptibility. For instance, three clade V genes in cucumber (CsaMLO1, CsaMLO8, and CsaMLO11) have been experimentally confirmed to modulate susceptibility to PM [20,22,23,37,38]. Similarly, three clade V orthologs in melon (CmMLO5, CmMLO3, and CmMLO12) are considered candidate S-genes [17,19,39].

In this study, we identified a clade V MLO gene in watermelon, denoted by ClMLO5b (Gene ID: Cla97C05G102540, annotated as MLO-like protein), through phylogenetic analysis and homology modeling. Tertiary structure models of CsaMLO8, CmMLO5, and ClMLO5b were constructed using Swiss-Model and aligned with PDB-based tools. The results confirmed high structural conservation among the three proteins, with RMSD values below 1.5 Å and TM-scores exceeding 0.75, indicating nearly identical backbone architectures (Figure 1a,b). These findings align with previous phylogenetic analyses of cucurbit MLO genes and further support the functional conservation of clade V members in PM susceptibility [17]. Notably, variations were observed in flexible regions such as the N- and C-terminal segments and specific extracellular loops. Such structural divergence may underlie species-specific functional adaptation, potentially influencing host–pathogen recognition and defense responses. Our analysis also revealed subtle structural differences in these regions between ClMLO5b and its orthologs, suggesting a unique evolutionary trajectory in watermelon’s PM resistance mechanism.

The use of Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation for validating gene editing efficiency represents a critical and efficient step in functional genomics studies of horticultural crops. This approach leverages the ability of the Ri plasmid-derived rol genes in A. rhizogenes to efficiently induce hairy roots in plant tissues. By introducing a constructed CRISPR/Cas9 editing vector into the bacterium through plasmid recombination or co-transformation, and subsequently infecting plant explants with the engineered strain, researchers can rapidly and cost-effectively assess gRNA efficiency before committing to time-consuming stable transformation. In this study, we first employed this hairy root transformation system to confirm the high editing efficiency of gRNAs targeting the ClMLO5b gene (Figure 3e). Following successful validation, we proceeded with stable genetic transformation using the same gRNA construct in a PM-susceptible watermelon variety via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated method, ultimately obtaining a mutant plant with precise edits at the ClMLO5b locus (Figure 4b). This mutant was subsequently subjected to comprehensive disease resistance evaluation.

The Clmlo5b not only exhibits delayed pathogen-induced gene response timepoints but also inhibits hyphal development (Figure 5a,b) and also showed significantly reduced disease indices and conidial production at later infection stages (Figure 5c,d). These collective results demonstrate that ClMLO5b functions as a typical susceptibility factor in the watermelon-PM interaction. Notably, no significant differences were observed between the mutant and wild-type plants during early infection stages (12 hpi) in terms of spore germination and germ tube formation, indicating that ClMLO5b disruption does not affect initial pathogen recognition or penetration attempts. However, by 72 hpi, fungal development was arrested in the mutant, with only limited primary hyphae formation and failure to establish successful parasitic relationship. Interestingly, although significantly reduced, Clmlo5b transcript accumulation was still inducible upon infection in the mutant. This residual expression likely originates from the mutated allele. Whether this transcript produces a truncated protein with partial or altered function or is subject to nonsense-mediated decay requires further investigation. Nevertheless, the strong loss-of-susceptibility phenotype observed indicates that any potential truncated protein is insufficient to support full pathogen colonization. This suggests that ClMLO5b likely functions as a negative regulator of basal defense responses at infection sites. In WT, PM may exploit ClMLO5b protein to suppress such physical or chemical defenses, thereby facilitating successful colonization, whereas in the mutant, sustained activation of defense responses ultimately restricts pathogen establishment and spread. This finding is consistent with previous reports on MLO gene functions in cucurbits. For instance, Mamin Ibrahim Tek et al. observed that only limited spore germination and hyphal growth occurred in CsaMLO8-edited cucumber plants 10 days post-inoculation [22]. Similarly, Dong S et al. obtained PM-resistant mutants through CsaMLO8 knockout [38]. These independent results collectively demonstrate the conserved role of MLO genes as susceptibility factors and validate the infection-inhibiting phenotype resulting from their functional disruption.

5. Conclusions

ClMLO5b plays a central role in watermelon immunity against powdery mildew. Its disruption significantly enhances resistance, likely due to the gene’s regulatory function during early infection stages. The loss of Clmlo5b may facilitate accelerated activation of defense mechanisms, thereby delaying infection and suppressing fungal development. These findings not only identify ClMLO5b as a promising target for genetic improvement of powdery mildew resistance in watermelon but also provide valuable insights for breeding programs in other susceptible horticultural crops. Future studies should investigate the precise role of ClMLO5b in immune signaling pathways and explore the transfer of this resistance mechanism to other crops through gene editing, thereby expanding its application in disease-resistant breeding.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121517/s1, Figure S1: Sequencing peak diagram of Agrobacterium-mediated gene editing mutation sites in root cells. Table S1: Gene IDs of Watermelon MLO. Table S2: Primer sequence information. Table S3: Pairwise Structure Alignment. Table S4: qPCR thermal cycling conditions. Table S5: Medium components for watermelon tissue culture

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing, L.W.; software, validation and formal analysis, W.S.; data curation, J.Z.; investigation and resources, Z.Z.; visualization, S.P.; investigation, Y.C.; project administration, supervision and funding acquisition, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant NO. U21A20229), the major development program of Heilongjiang Province (Grant NO. GA23B007), and the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province (Grant NO. ZL2024C011).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McGrath, M.T.; Staniszewska, H.; Shishkoff, N.; Casella, G. Fungicide sensitivity of Sphaerotheca fuliginea populations in the United States. Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.K.; Suren, H.; Kousik, C. Elucidation of resistance signaling and identification of powdery mildew resistant mapping loci (ClaPMR2) during watermelon-Podosphaera xanthii interaction using RNA-Seq and whole-genome resequencing approach. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kousik, C.S.; Levi, A.; Ling, K.; Wechter, W.P. Potential Sources of Resistance to Cucurbit Powdery Mildew in U.S. Plant Introductions of Bottle Gourd. HortScience 2008, 43, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.R.; Levi, A.; Wehner, T.; Pitrat, M. PI 525088-PMR, A Melon Race 1 Powdery Mildew-resistant Watermelon Line. HortScience 2006, 41, 1527–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, Y.; Cohen, Y. Inheritance of Resistance to Powdery Mildew Race 1W in Watermelon. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 1446–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.E.; Levi, A.; Caniglia, E. Evaluation of U.S. Plant Introductions of Watermelon for Resistance to Powdery Mildew. HortScience 2005, 40, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büschges, R.; Hollricher, K.; Panstruga, R.; Simons, G.; Wolter, M.; Frijters, A.; van Daelen, R.; van der Lee, T.; Diergaarde, P.; Groenendijk, J.; et al. The barley Mlo gene: A novel control element of plant pathogen resistance. Cell 1997, 88, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devoto, A.; Hartmann, H.A.; Piffanelli, P.; Elliott, C.; Simmons, C.; Taramino, G.; Goh, C.S.; Cohen, F.E.; Emerson, B.C.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; et al. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the plant-specific seven-transmembrane MLO family. J. Mol. Evol. 2003, 56, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.C.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.K.; Chun, H.J.; Choi, M.S.; Chung, W.S.; Moon, B.C.; Kang, C.H.; Park, C.Y.; Yoo, J.H.; et al. Mlo, a modulator of plant defense and cell death, is a novel calmodulin-binding protein. Isolation and characterization of a rice Mlo homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 19304–19314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, S.; Jacobsen, E.; Visser, R.G.F.; Bai, Y. Loss of susceptibility as a novel breeding strategy for durable and broad-spectrum resistance. Mol. Breed. 2010, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Pavan, S.; Zheng, Z.; Zappel, N.F.; Reinstädler, A.; Lotti, C.; De Giovanni, C.; Ricciardi, L.; Lindhout, P.; Visser, R.; et al. Naturally occurring broad-spectrum powdery mildew resistance in a Central American tomato accession is caused by loss of mlo function. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact 2008, 21, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphry, M.; Reinstädler, A.; Ivanov, S.; Bisseling, T.; Panstruga, R. Durable broadspectrum powdery mildew resistance in pea er1 plants is conferred by natural loss-of-function mutations in PsMLO1. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan, S.; Schiavulli, A.; Appiano, M.; Marcotrigiano, A.R.; Cillo, F.; Visser, R.G.; Bai, Y.; Lotti, C.; Ricciardi, L. Pea powdery mildew er1 resistance is associated to loss-of-function mutations at a MLO homologous locus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 123, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Nonomura, T.; Appiano, M.; Pavan, S.; Matsuda, Y.; Toyoda, H.; Wolters, A.M.; Visser, R.G.; Bai, Y. Loss of function in Mlo orthologs reduces susceptibility of pepper and tomato to powdery mildew disease caused by Leveillula taurica. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Shan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, C.; Qiu, J.L. Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovieno, P.; Andolfo, G.; Schiavulli, A.; Catalano, D.; Ricciardi, L.; Frusciante, L.; Ercolano, M.R.; Pavan, S. Structure, evolution and functional inference on the Mildew Locus O (MLO) gene family in three cultivated Cucurbitaceae spp. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consonni, C.; Humphry, M.E.; Hartmann, H.A.; Livaja, M.; Durner, J.; Westphal, L.; Vogel, J.; Lipka, V.; Kemmerling, B.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; et al. Conserved requirement for a plant host cell protein in powdery mildew pathogenesis. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, N.; Amanullah, S.; Gao, P. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and expression analysis of MLO gene family in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1144317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.A.; Appiano, M.; Martínez, M.S.; Hermans, F.W.; Vriezen, W.H.; Visser, R.G.; Bai, Y.; Schouten, H.J. A transposable element insertion in the susceptibility gene CsaMLO8 results in hypocotyl resistance to powdery mildew in cucumber. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnaider, Y.; Elad, Y.; Rav-David, D.; Pashkovsky, E.; Leibman, D.; Kravchik, M.; Shtarkman-Cohen, M.; Gal-On, A.; Spiegelman, Z. Development of Powdery Mildew Resistance in Cucumber Using CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis of CsaMLO8. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tek, M.I.; Calis, O.; Fidan, H.; Shah, M.D.; Celik, S.; Wani, S.H. CRISPR/Cas9 based mlo-mediated resistance against Podosphaera xanthii in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1081506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Yang, L.; Hu, Z.; Mo, C.; Geng, S.; Zhao, X.; He, Q.; Xiao, L.; Lu, L.; Wang, D.; et al. Multiplex gene editing reveals cucumber MILDEW RESISTANCE LOCUS O family roles in powdery mildew resistance. Plant Physiol. 2024, 195, 1069–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Jiang, L.; Cui, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Gong, G.; Zong, M.; et al. Engineering herbicide-resistant watermelon variety through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated base-editing. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 1353–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, S.; Tian, S.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, M.; Gong, G.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of ClBG1 decreased seed size and promoted seed germination in watermelon. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Xiao, L.; He, Y.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Tian, S.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, L. Highly efficient, genotype-independent transformation and gene editing in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) using a chimeric ClGRF4-GIF1 gene. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 2038–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Zong, M.; Li, M.; Gong, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Production of double haploid watermelon via maternal haploid induction. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1308–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, C.; He, W.; Wang, J.; Tian, S.; Yuan, L. ClPS1 gene-mediated manipulation of 2n pollen formation enables the creation of triploid seedless watermelon. Mol. Hortic. 2025, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Feng, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Luan, F.; Zhang, X.; Tian, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Establishing a highly efficient diploid seedless watermelon production system through manipulation of the SPOROCYTELESS gene. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 1128–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Tian, C.; Feng, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, S.; Yuan, L. Unlocking the role of ClDYAD in initiating meiosis: A functional analysis in watermelon. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 1260–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Ji, G.; Zhao, H.; Sun, H.; Ren, Y.; Tian, S.; Li, M.; Gong, G.; Zhang, H.; et al. A unique chromosome translocation disrupting ClWIP1 leads to gynoecy in watermelon. Plant J. 2020, 101, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Sikdar, A.; Zhang, X. Evaluation of watermelon germplasm and advance breeding lines against powdery mildew race ‘2F’. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 58, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Q.; Yuan, J.; Gao, L.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, W.; Huang, Y.; Bie, Z. Identification of suitable reference genes for gene expression normalization in qRT-PCR analysis in watermelon. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letkova, V. Peroxidase isozyme polymorphism in Cucurbita pepo cultivars with various morphotypes and different level of field resistance to powdery mildew. Sci. Hortic. 1999, 8, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, B.E.J.; Kent, G.C. An introduction to plant diseases. Q. Rev. Biol. 1969, 45, 299–300. [Google Scholar]

- Appiano, M.; Catalano, D.; Martínez, M.S.; Lotti, C.; Zheng, Z.; Visser, R.G.; Ricciardi, L.; Bai, Y.; Pavan, S. Monocot and dicot MLO powdery mildew susceptibility factors are functionally conserved in spite of the evolution of class-specific molecular features. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Wang, Y.; He, H.; Guo, C.; Zhu, W.; Pan, J.; Li, D.; Lian, H.; Pan, J.; Cai, R. Loss-of-Function Mutations in CsMLO1 Confer Durable Powdery Mildew Resistance in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Liu, X.; Han, J.; Miao, H.; Beckles, D.M.; Bai, Y.; Liu, X.; Guan, J.; Yang, R.; Gu, X.; et al. CsMLO8/11 are required for full susceptibility of cucumber stem to powdery mildew and interact with CsCRK2 and CsRbohD. Hortic. Res. 2023, 11, uhad295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Fan, C.; Ding, Z.; Wang, X.; Tang, L.; Bi, Y.; Luan, F.; Gao, P. CmPMRl and CmPMrs are responsible for resistance to powdery mildew caused by Podosphaera xanthii race 1 in Melon. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 1209–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).