Abstract

Medicinal plants have garnered widespread attention owing to their broad range of biological activities and pharmaceutical value. However, achieving a balance between promoting plant growth and enhancing bioactive compound accumulation remains a major challenge in current research. In this study, Salvia miltiorrhiza was selected as the model organism to investigate the effects of MgH2 on growth and the accumulation of bioactive compounds. Our results demonstrated that MgH2 treatment at 10.0 mg kg−1 soil increased the seed germination rate by 49.3%. At the optimal concentration of 12.5 mg kg−1 soil, MgH2 significantly promoted seedling growth, enhancing root biomass by 745.6% after 4 weeks of treatment. Furthermore, MgH2 application dramatically boosted the accumulation of bioactive compounds, increasing the total content of rosmarinic acid and dihydrotanshinone by 1271.8% and 2407.7%, respectively. Transcriptome analysis revealed that these improvements were associated with the upregulation of genes involved in plant hormone signal transduction, energy metabolism, and the biosynthesis pathways of tanshinones and salvianolic acids. Our findings provide the first evidence that MgH2 acts as a dual-functional regulator, simultaneously enhancing both plant growth and secondary metabolite accumulation in medicinal plants, offering a green and efficient cultivation strategy for the sustainable production of high-quality S. miltiorrhiza.

1. Introduction

Medicinal plants are widely acknowledged for their extensive bioactivities and pharmaceutical value [1] (Gao et al., 2024). Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge is a perennial medicinal plant in the genus Salvia of the family Lamiaceae [2]. Salvia miltiorrhiza, commonly known as Danshen, typically 30–60 cm in height with erect stems, opposite leaves, and distinctive whorled purple-blue flowers, is extensively cultivated across provinces such as Shandong, Henan, Shanxi, and Anhui. Its primary medicinal part is the root, which contains various bioactive compounds with antioxidant [3], anti-inflammatory [4], antitumor [5], and cardiovascular protective properties [6], such as tanshinones and salvianolic acids [7]. Due to its wide range of pharmacological activities, S. miltiorrhiza has been extensively applied in traditional Chinese medicine for treating cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, liver diseases, cancer, and other conditions [8]. Moreover, S. miltiorrhiza, owing to its relatively short life cycle, ease of propagation and cultivation, relatively small genome size (approximately 538 Mb) [9,10], and well-established genetic transformation [11,12,13] and gene editing systems [14], has emerged as one of the model systems in medicinal plant biology [15]. However, due to environmental factors, planting conditions, and cultivation techniques, the yield and quality of S. miltiorrhiza exhibit considerable variability [16,17,18,19], affecting its application in modern pharmaceutical industries. Various exogenous elicitors, including methyl jasmonate (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), silver ions (Ag+), and yeast extract (YE), have been employed to enhance the accumulation of bioactive compounds in medicinal plants [20,21,22,23,24,25]. Nevertheless, achieving a balance between promoting plant growth and enhancing active compound biosynthesis remains a major challenge [26]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop eco-friendly methods capable of simultaneously promoting plant growth and increasing the accumulation of active compounds.

Magnesium hydride (MgH2) is a metal hydride with a high hydrogen storage capacity. It reacts with water to produce hydrogen gas (H2) and magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) at room temperature [27]. This characteristic has led to its widespread use in energy storage and fuel cell technologies. Recently, with a deeper understanding of plant physiological regulation, the potential of MgH2 in agriculture and horticulture has gradually gained attention. Studies have shown that H2 released from MgH2 can act as a signaling molecule, regulating various physiological processes in plants, such as seed germination, photosynthesis, and stress resistance [28,29,30,31]. Furthermore, Mg(OH)2 can slowly release magnesium ions (Mg2+) in soil, participating in chlorophyll synthesis and improving photosynthetic efficiency [32,33]. Therefore, MgH2, as a novel plant growth regulator, shows great promise for application. Previous studies have demonstrated that MgH2 exhibits significant physiological regulatory effects across different plant species. For instance, MgH2 can extend the vase life of cut flowers by regulating nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen sulfide signaling [34,35] and alleviate copper toxicity in alfalfa seedlings [36]. Moreover, MgH2 can mitigate cadmium-induced damage in rice seedlings by influencing RNA m6A methylation modifications [29] and reduce oxidative injury caused by osmotic stress through activation of the ascorbate-glutathione cycle [30]. These studies collectively indicate that MgH2 plays a crucial role in plant stress tolerance and growth regulation. However, its application in medicinal plants, particularly its potential to concurrently enhance growth and bioactive compound accumulation, remains unexplored.

To investigate the role of MgH2 in medicinal plants, we selected S. miltiorrhiza, a well-studied medicinal model plant, as the subject of our research. Seedlings were treated with varying concentrations of 10.0, 12.5, and 15 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil [30,35], and the results demonstrated that MgH2 positively influenced seed germination and seedling growth and development, while significantly enhancing the accumulation of active compounds such as tanshinones and salvianolic acids. The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon were explored by integrating transcriptomic sequencing technology. This study provides the first evidence of these effects, highlighting the potential of MgH2 to promote both plant growth and secondary metabolite biosynthesis in medicinal plants. Optimizing the concentration and timing of MgH2 application has led to a green and efficient cultivation strategy for S. miltiorrhiza, which can be applied to other medicinal plants as well.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Cultivation Conditions

The S. miltiorrhiza seeds used in this study were from a genetically stable line preserved in the germplasm repository of the College of Life Sciences and Medicine, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University. These seeds are maintained under standard conditions (4 °C, low humidity) to ensure viability and genetic integrity. After screening, plump and uniformly sized seeds were selected for experimentation. The experimental soil substrate consisted of a mixture of nutrient soil, vermiculite, and perlite at a volume ratio of 3:1:1, ensuring good aeration and water retention [36]. Soil moisture was maintained at approximately 60% water-holding capacity, ensuring no visible water discharge upon compression. The plants were cultivated in a growth chamber under the following conditions: a 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod with a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 300 μmol m−2 s−1, day/night temperatures of 25/20 °C, and 65% relative humidity.

2.2. MgH2 Treatments

The MgH2 reagent was provided by the Center of Hydrogen Science, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Based on literature reports and preliminary experimental results, the optimal application concentration range of MgH2 was determined to be 10.0–15.0 mg kg−1 soil. Three treatment concentrations and a control group were established: 10.0 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group a), 12.5 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group b), 15.0 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group c), and an untreated control group (Group ck). Each treatment had at least 3 biological replicates to ensure data reliability. MgH2 powder was uniformly applied into the soil at designated concentrations during soil preparation and thoroughly mixed.

The seeds of S. miltiorrhiza were selected and rinsed 3–5 times with distilled water. The treated seeds were then sown into soil mixtures containing different concentrations of MgH2. Each culture pot was sown with 200 seeds, with 3 biological replicates per treatment group. The seed germination rate was determined after 14 days to assess the impact of MgH2 on S. miltiorrhiza seed germination.

2.3. Growth and Photosynthetic Analysis of S. miltiorrhiza Seedlings

After germination and the emergence of two true leaves, S. miltiorrhiza seedlings were transplanted into pots. Each pot contained 1 kg of moist soil, with 8 seedlings planted per pot. Two weeks after transplantation, the seedlings, which had been growing for approximately 5 weeks, were treated with MgH2. Samples were collected every fortnight, data were recorded, and fresh samples were stored for further analysis. From each treatment group, six seedlings were selected for measurement. Photosynthetic parameters were determined using the LCPRO+ photosynthesis system. The following growth parameters were recorded: plant height, root length, leaf length, leaf width, and leaf count. Additionally, the fresh and dry weights of the roots, stems, and leaves were measured. Note: Plant height was defined as the vertical distance from the highest growth point to the soil surface. Root length was measured from the soil surface to the tip of the longest primary root. Leaf length and width were measured at maximum expansion points. Leaf count: total number of leaves per plant. Fresh and dry weights: fresh weights of aerial parts (stems and leaves) and roots were weighed separately, followed by drying at 45 °C for 48 h to determine dry weights.

2.4. Extraction and Quantification of Secondary Metabolites from S. miltiorrhiza Roots

Root samples of S. miltiorrhiza were thoroughly cleaned and weighed to 0.5 g. These samples were then dried in an oven at 45 °C for 48 h to ensure complete moisture evaporation. The dried samples were subsequently ground using a tissue homogenizer to obtain a fine powder. An accurate amount (0.02 g) of the powdered sample was weighed and transferred into a 2.0 mL centrifuge tube. To this, 1.5 mL of 70% methanol was added for extraction. The mixture was subjected to ultrasonic extraction for 1 h in an ultrasonic bath, with periodic shaking every 15 min to ensure even extraction. Following extraction, samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully aspirated using a 2 mL syringe and filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter to remove any particulate impurities. Chromatographic analysis of metabolites was carried out using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) under the following analytical conditions. Separation was performed on a reversed-phase C18 column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm particle size), maintained at a constant temperature of 30 °C. The mobile phase consisted of two components: solvent A (acetonitrile) and solvent B (0.02% phosphoric acid in water). A gradient elution program was applied to optimize the separation of target compounds. The flow rate was set at 1.0 mL/min throughout the run. Detection was carried out using a photodiode array (PDA) detector. For fat-soluble diterpenes (e.g., tanshinones), the detection wavelength was set at 270 nm; for water-soluble phenolic acids (e.g., salvianolic acids), it was set at 288 nm. The identification of individual compounds was confirmed by comparing their retention times with those of authentic reference standards. All standard substances were purchased from the China National Institute for Food and Drug Control (Beijing, China). Data were analyzed using the Empower 3 software system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA). Metabolite concentrations were determined and calculated as described previously [37,38], ensuring accuracy and reproducibility across samples.

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing of S. miltiorrhiza Seedling Roots

Root samples from Group b and Group ck at 4 weeks, which exhibited the most significant growth differences, were selected for transcriptomic sequencing. To further explore the molecular mechanisms by which MgH2 promotes the growth and accumulation of active compounds in S. miltiorrhiza, root samples from the 4-week treatment group (12.5 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil, Group b) and the control group (ck) were subjected to transcriptomic sequencing. Sequencing was performed by Wuhan Benagen Tech Solutions Company Limited. RNA was extracted using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and RNA integrity was assessed by NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). High-quality RNA was then used for library construction, followed by paired-end sequencing (150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Rigorous quality control procedures were applied to filter out low-quality or contaminated sequences, ensuring data reliability and accuracy. The resulting data were analyzed through alignment to the reference genome, quantification of gene expression levels, identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), functional enrichment analysis, and investigation of novel genes and alternative splicing events. These analyses aimed to provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed phenotypic differences between the experimental groups. The criteria for selecting DEGs were log2FoldChange ≥1 or ≤−1 and FDR < 0.05. KEGG enrichment analysis was employed to identify key pathways associated with growth, development, and secondary metabolism. The quality of the transcriptome sequencing data was assessed by Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The raw RNA-seq data have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database. The accession number is PRJNA1369401.

2.6. RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using Transzol reagent (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NE, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) with FastStar Universal SYBR Green Master mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The Salvia miltiorrhiza actin gene (XM_057912742.1) was used as the reference gene for normalization. Relative expression levels of target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All gene-specific primers used for qRT-PCR are listed in Table S2.

2.7. Data Statistics and Analysis

All experimental data were statistically analyzed using SPSS Statistics (v.27) and GraphPad Prism (v.10.1). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for statistical comparisons, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05) or two-tailed Student’s t-test (p < 0.05) as appropriate. All experiments were conducted with at least 3 biological replicates to ensure data reliability and reproducibility. All figures were generated using GraphPad Prism (v.10.1), Adobe Photoshop (v.2024), and Adobe Illustrator (v.2024).

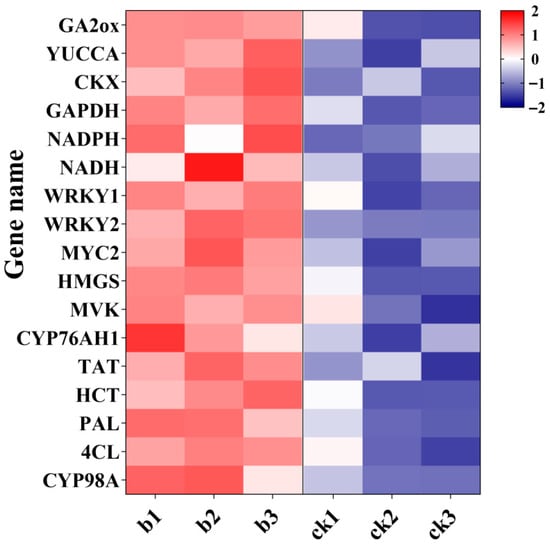

For the gene expression heatmap, the transcriptomic data were processed and visualized as follows to ensure clarity and accurate representation of the treatment effects. The analysis was based on Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) values obtained from root samples of the MgH2-treated group (Group b) and the control group (Group ck) at 4 weeks.

To prepare the data for visualization, a two-step transformation was applied. First, raw FPKM values were subjected to a log2(FPKM + 1) transformation. The addition of 1 prevents undefined values when taking the logarithm of zero and helps mitigate the right-skewed distribution typical of expression data, making the distribution more suitable for downstream analysis. Subsequently, the log-transformed data were Z-score normalized across samples for each gene using the formula Z = (x−μ)/σ, where x is the log-transformed value, μ is the mean, and σ is the standard deviation. This standardization centers the data around a mean of 0 with a standard deviation of 1, allowing for an intuitive comparison of relative expression changes across different genes. The normalized Z-score matrix was used to generate the hierarchical clustering heatmap. The color scale was explicitly defined to reflect the direction and magnitude of change: a Z-score of 0 is represented as white, indicating expression at the average level. Positive Z-scores (up-regulation in the treated group) are represented in a gradient of red, while negative Z-scores (down-regulation) are represented in a gradient of blue.

Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed to visualize the global effects of MgH2 treatment on phenotypic traits and metabolite accumulation. For phenotypic clustering (Figure S2), the dataset included all growth parameters (plant height, root length, leaf length, leaf width, leaf number) and physiological indices (aerial part/root fresh and dry weights, ΔC, Pn). For metabolic clustering (Figure S3), the contents of seven major bioactive compounds (caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, salvianolic acid B, cryptotanshinone, tanshinone IIA, dihydrotanshinone, and tanshinone) were analyzed. All data were z-score normalized to give equal weight to each variable. Hierarchical clustering was performed in R (version 4.2.0) using the pheatmap package (version 1.0.12), employing the clustering distance rows parameter.

3. Results

3.1. MgH2 Treatment Promotes Seed Germination in S. miltiorrhiza

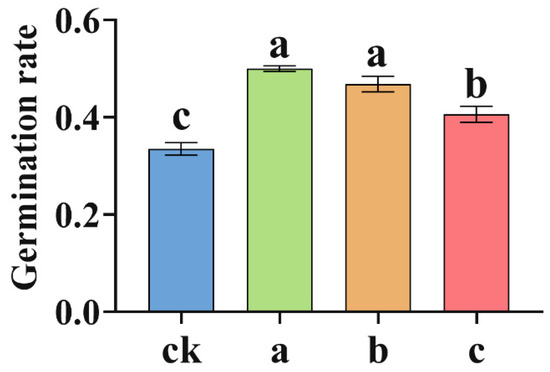

To investigate the effects of MgH2 on seed germination, plump and uniformly sized S. miltiorrhiza seeds were sown in pots with soil MgH2 concentrations of 0 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group ck), 10.0 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group a), 12.5 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group b), and 15.0 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group c). After two weeks of treatment, germination rates were recorded. The results demonstrated that MgH2 significantly enhanced seed germination. The germination rate was 33.5% in Group ck, 50.0% in Group a, 46.8% in Group b, and 42.0% in Group c (Figure 1). Compared to Group ck, the germination rates increased by 49.3% in Groups a, 39.7% in Groups b, and 25.4% in Groups c, with Group a displaying the most pronounced improvement. These findings indicate that MgH2 effectively promotes S. miltiorrhiza seed germination within a specific concentration range, with 10.0 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil identified as the optimal concentration.

Figure 1.

Seed germination rate of S. miltiorrhiza. The different letters on the columns indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD. A total of 3 biological replicates were set for each group. In the figures, ck, a, b, and c represent treatment groups with 0, 10.0, 12.5, and 15.0 mg of MgH2 applied per kg of soil, respectively.

3.2. MgH2 Enhances Seedling Shoot Growth and Development in S. miltiorrhiza

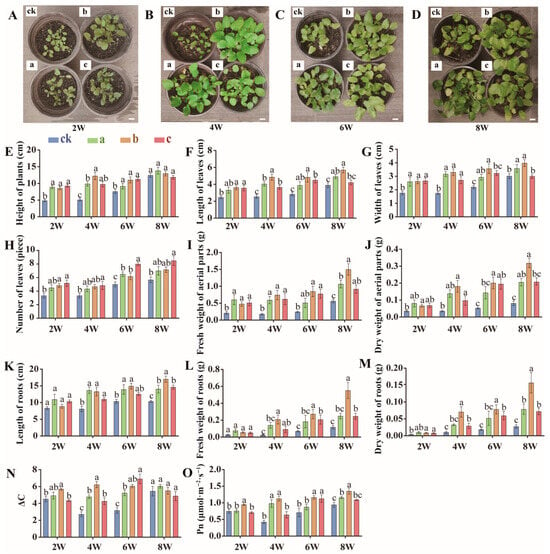

Five-week-old S. miltiorrhiza seedlings were treated with 0 mg (Group ck), 10.0 mg soil (Group a), 12.5 mg (Group b), or 15 mg (Group c) MgH2 kg−1 soil for eight weeks to systematically analyze its effects on seedling growth. Morphological and physiological parameters of the shoots were measured biweekly. From the second week onward, MgH2-treated seedlings exhibited accelerated shoot growth, outperforming Group ck in plant height, leaf length, leaf width, leaf number, and aerial parts fresh/dry weights (Figure 2A–J and Figure S1). Notably, Group b displayed the most significant growth advantage after four weeks of treatment, with plant height increasing by 140.3% (Figure 2E), aerial parts fresh weight by 311.1% (Figure 2I), and aerial parts dry weight by 414.3% compared to Group ck (Figure 2J). These results suggest that MgH2 markedly promotes shoot development in S. miltiorrhiza seedlings.

Figure 2.

Morphological and physiological indicators of S. miltiorrhiza seedlings under MgH2 treatment. Note: In the figures, ck, a, b, and c represent treatment groups with 0, 10.0, 12.5, and 15.0 mg of MgH2 applied per kg of soil, respectively. 2W, 4W, 6W, and 8W indicate the duration of treatment (2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks, respectively). (A–D) Photographs of S. miltiorrhiza seedings in pots treated with MgH2 for 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 6 weeks, or 8 weeks (Scale bars: 2 cm). (E–H) Plant height, leaf length, leaf width, and leaf numbers of S. miltiorrhiza seedlings under different treatments. (I,J) Fresh weight and dry weight of aerial parts of S. miltiorrhiza seedlings. (K–M) Root length, root fresh weight, and dry weight of S. miltiorrhiza seedlings. (N) Carbon dioxide increment of S. miltiorrhiza seedlings. (O) Photosynthetic rate of S. miltiorrhiza seedlings. Leaf length and width measurements were taken from the longest and widest part of the largest leaf when unfolded. The different letters on the columns indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD. A total of 6 biological replicates were set for each group. The percentage increases mentioned in the text are calculated relative to the time-matched control group (Group ck).

Given prior evidence that Mg2+ enhances photosynthesis, we evaluated the impact of MgH2 on CO2 assimilation (ΔC) and net photosynthetic rate (Pn) in seedlings. MgH2 treatment, particularly in Group B at four weeks, significantly elevated ΔC and Pn by 125.9% (Figure 2N) and 169.0% (Figure 2O), respectively, indicating improved photosynthetic efficiency. As photosynthesis drives plant growth, these results imply that MgH2 likely facilitates seedling development by augmenting energy production via enhanced photosynthesis.

3.3. MgH2 Increases Root Biomass in S. miltiorrhiza

The medicinal value of S. miltiorrhiza primarily resides in its roots; thus, root biomass directly influences yield and quality. Previous studies have shown that H2 promotes root elongation and lateral root formation [39]. Our data revealed that MgH2 treatment significantly increased root length (Figure 2K), fresh weight (Figure 2L), and dry weight (Figure 2M), with the most pronounced effects observed at four weeks. Group b exhibited a 90.2% increase in root length, 745.6% higher fresh weight, and 584.5% greater dry weight relative to Group ck (Figure 2K–M). These findings demonstrate that MgH2 not only stimulates shoot growth but also enhances root development, enabling more efficient water and nutrient uptake, thereby bolstering overall plant vigor. The dual mechanisms of MgH2 action may involve (i) boosting carbon assimilation via photosynthesis and (ii) strengthening root systems to improve resource acquisition.

3.4. MgH2 Elevates the Accumulation of Tanshinones and Salvianolic Acids in S. miltiorrhiza Roots

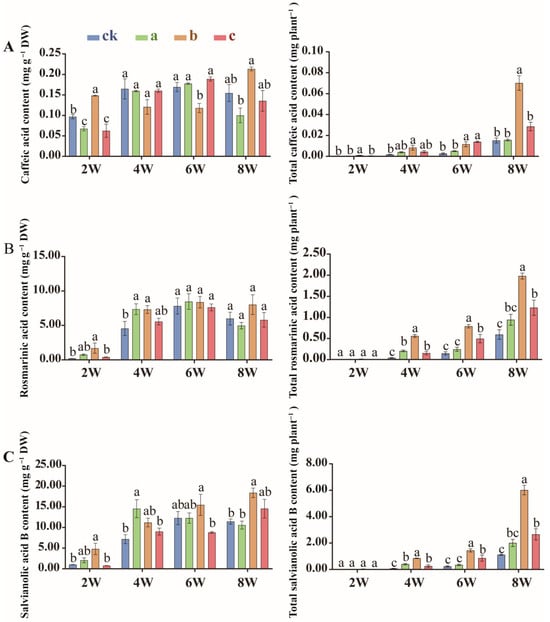

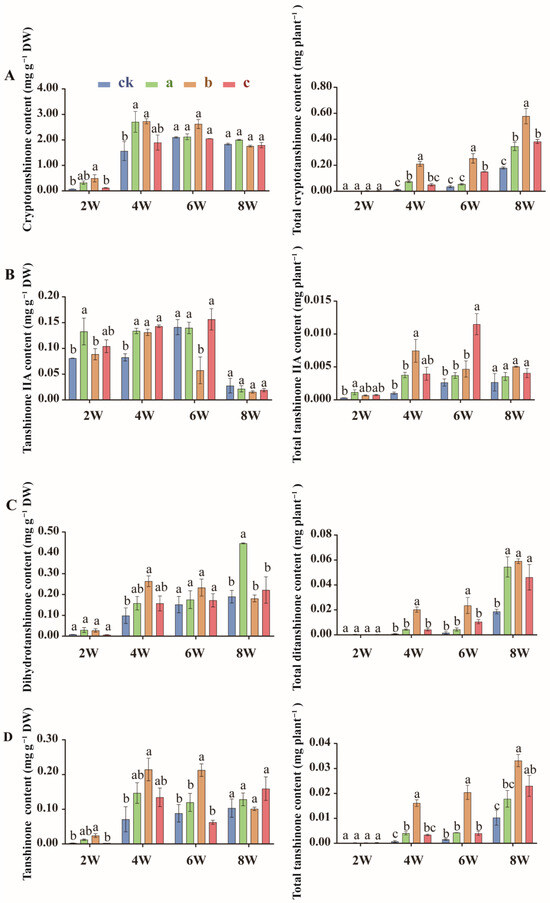

S. miltiorrhiza contains two major classes of bioactive constituents: the hydrophilic salvianolic acids (e.g., caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, salvianolic acid B) and the lipophilic tanshinones (e.g., cryptotanshinone, tanshinone IIA, dihydrotanshinone, tanshinone). These compounds collectively exert potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective activities. HPLC analysis revealed that MgH2 treatment significantly increased the unit and total contents of these compounds in roots, and the differences were most obvious in group b after 2 and 4 weeks of MgH2 treatment.

After two weeks of treatment, the unit content of caffeic acid (Figure 3A), rosmarinic acid (Figure 3B), salvianorin B (Figure 3C), cryptotanshinone (Figure 4A), tanshinone IIA (Figure 4B), dihydrotanshinone (Figure 4C), and tanshinone (Figure 4D) in the roots of group b rose by 53.2%, 704.1%, 376.5%, 568.0%, 9.6%, 222.3%, and 813.6%, respectively. By four weeks, the total root content of these compounds increased by 393.6%, 1271.8%, 1054.1%, 1529.4%, 634.1%, 2407.7%, and 2104.9%, respectively (Figure 3A–C and Figure 4A–D).

Figure 3.

Unit (left) and total (right) contents of caffeic acid (A), rosmarinic acid (B) and salvianorin B (C) in S. miltiorrhiza roots under MgH2 treatment. The different letters on the columns indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD. A total of 3 biological replicates were set for each group. The percentage increases mentioned in the text are calculated relative to the time-matched control group (Group ck).

Figure 4.

Unit (left) and total contents (right) of cryptotanshinone (A), tanshinone IIA (B), dihydrotanshinone (C), and tanshinone (D) in S. miltiorrhiza roots under MgH2 treatment. The different letters on the columns indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05). Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SD. A total of 3 biological replicates were set for each group. The percentage increases mentioned in the text are calculated relative to the time-matched control group (Group ck).

Strikingly, the magnitude of the increase in bioactive compounds varied significantly among individual metabolites. For instance, rosmarinic acid and dihydrotanshinone exhibited the most dramatic rises in both unit and total content, with rosmarinic acid showing increases of 704.1% in unit content and 1271.8% in total content after two and four weeks (Figure 3B), respectively, and dihydrotanshinone demonstrating 222.3% and 2407.7% increases (Figure 4C). In contrast, compounds such as caffeic acid and tanshinone IIA displayed relatively modest gains in unit content (rising by 53.2% and 9.6% at two weeks, respectively) (Figure 3A and Figure 4B). Crucially, however, the substantial enhancement in root biomass amplified the accumulation of these metabolites, driving their total contents to surge by 393.6% for caffeic acid and 634.1% for tanshinone IIA by four weeks (Figure 3A and Figure 4B). The unit content reflects the metabolic intensity within the root tissue, while the total content per plant represents the integrated yield. The remarkable increases in total content, particularly for metabolites with more moderate rises in unit concentration, underscore that the boost in root biomass is a major driver for enhancing the net production of bioactive compounds. These disparities likely reflect distinct regulatory mechanisms governing phenylpropanoid (e.g., involving PAL and 4CL) and terpenoid (e.g., involving HMGS and MVK) metabolic pathways, suggesting that MgH2 differentially modulates secondary metabolite biosynthesis by both stimulating specific enzymatic pathways and leveraging root system expansion to boost overall resource acquisition and compound yield.

3.5. Multivariate Analysis Reveals Coordinated Enhancement by MgH2

To gain a comprehensive understanding of MgH2’s global effects, we performed hierarchical clustering analysis on both phenotypic and metabolic datasets. The phenotypic clustering (Figure S2) clearly separated MgH2-treated samples from the control group, with Group b (12.5 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil) demonstrating the most consistent and substantial improvements across most key growth and photosynthetic parameters. Similarly, metabolic clustering (Figure S3) revealed that Group b formed a distinct cluster exhibiting the most pronounced and coordinated enhancement in the accumulation of both salvianolic acids and tanshinones. Based on these multivariate analyses demonstrating the superior and most consistent performance of the 12.5 mg kg−1 treatment across the majority of measured traits, Group b was selected for subsequent transcriptome sequencing to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying MgH2’s optimal efficacy.

3.6. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Potential Mechanisms

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying MgH2-induced growth promotion and bioactive compound accumulation, we performed transcriptome sequencing on root samples from Group b and Group ck at four weeks post-treatment, where both growth parameters and total metabolite content exhibited maximal differential responses (Figure 2K–M, Figure 3 and Figure 4). Comparative analysis identified 578 upregulated and 771 downregulated genes (Figures S4 and S5). GO biological processes and KEGG enrichment highlighted significant pathways, including “Metabolic pathways,” “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites,” and “Plant hormone signal transduction” (Figure S6). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of the transcriptome data revealed a clear separation between the MgH2-treated and control groups along the principal component 1 (PC1), which accounted for 40.86% of the total variance (Figure S7). This distinct clustering of biological replicates within each group demonstrates the high reproducibility of our sequencing data and the pronounced effect of MgH2 on the root transcriptome.

Within the “Plant hormone signal transduction” pathway, growth and energy metabolism related genes (e.g., GA2ox, YUCCA, CKX, GAPDH, NADPH, NADH) were upregulated (Figure 5). The upregulation of GA2ox and YUCCA (involved in gibberellin synthesis) and CKX (cytokinin degradation), alongside energy metabolism genes (GAPDH, NADPH, NADH), suggests that MgH2 modulates hormonal balance and energy allocation to foster growth. In the “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites” pathway, genes associated with tanshinone and salvianolic acid production (WRKY1, WRKY2, MYC2, HMGS, MVK, CYP76AH1, TAT, HCT, PAL, 4CL, CYP98A) were significantly upregulated (Figure 5). This transcriptional activation likely drives the observed accumulation of bioactive compounds.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of gene expression for selected differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to root development and specialized metabolism at 4 weeks. The heatmap displays Z-score normalized expression values (derived from log2(FPKM + 1) transformed data, normalized per gene across all samples). Rows represent individual genes; columns represent biological replicates (b1, b2, b3: replicates of the MgH2-treated group; ck1, ck2, ck3: replicates of the control group). The color scale represents the Z-score: white (Z = 0, mean expression level), increasing intensities of red (positive Z-score, expression above the mean), and increasing intensities of blue (negative Z-score, expression below the mean.

To validate the reliability of our RNA-seq data, we selected 10 key DEGs (including WRKY1, WRKY2, MYC2, HMGS, MVK, CYP76AH1, TAT, PAL, 4CL, CYP98A75) for qRT-PCR analysis. The expression patterns of these genes determined by qRT-PCR were highly consistent with the RNA-seq results (Figure S8), confirming the accuracy of our transcriptomic profiling.

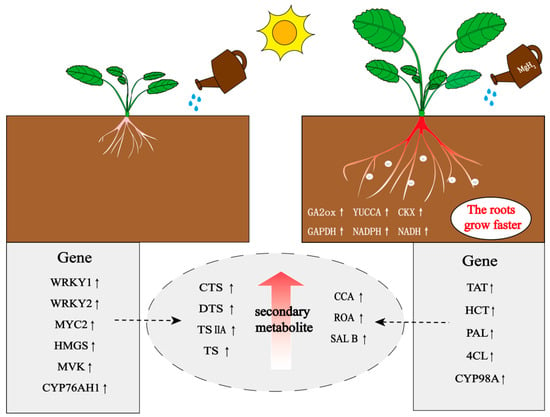

In summary, MgH2 promotes S. miltiorrhiza growth and metabolite synthesis through physicochemical effects and transcriptional regulation of key pathways (Figure 6), providing a theoretical foundation for its application in medicinal plant cultivation.

Figure 6.

MgH2 treatment enhances growth, root development and bioactive compound accumulation in S. miltiorrhiza by modulating hormone signaling, energy metabolism, and secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways. The upward arrow indicates an increase in gene expression level or metabolite content.

4. Discussion

Medicinal plants hold immense value in healthcare due to their rich bioactive compound reservoir. However, a persistent challenge in this field lies in simultaneously enhancing plant growth and the accumulation of pharmacologically active secondary metabolites [26]. This study presents the first application of magnesium hydride (MgH2) to the model medicinal plant S. miltiorrhiza, systematically investigating its effects on seed germination, seedling growth, photosynthesis, root biomass accumulation, and the content of key bioactive constituents, including tanshinones and salvianolic acids.

Our results demonstrate that MgH2 treatment was associated with significantly enhanced seed germination efficiency (Figure 1) and accelerated seedling growth above ground, as evidenced by increased plant height, leaf area, leaf number, and biomass (Figure 2A–J). This growth promotion was accompanied by improved photosynthetic performance, indicated by elevated CO2 assimilation (ΔC) and net photosynthetic rate (Pn) (Figure 2N–O). Crucially, MgH2 treatment also substantially increased root biomass (Figure 2K–M). Moreover, it was linked to significantly boosting the accumulation of the core secondary metabolites, tanshinones and salvianolic acids (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Notably, concentration-dependent effects were observed: 10 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group a) yielded the highest germination rate (Figure 1), while 12.5 mg MgH2 kg−1 soil (Group b) provided superior growth promotion at the seedling stage (Figure 2). This suggests distinct physiological requirements during different developmental phases. The differential responses to MgH2 concentrations at various growth stages may be attributed to complex interactions between internal hormonal regulation and external environmental factors. During seed germination, the optimal effect at 10 mg kg−1 could be linked to H2-mediated modulation of abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA) metabolism [40,41], which are critical for breaking dormancy and initiating germination. The slightly higher concentration (12.5 mg kg−1) required for optimal seedling growth might reflect the increased demand for magnesium as a cofactor in numerous enzymatic reactions involved in central metabolic pathways, including glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and ATP synthesis. These metabolic processes provide essential energy and carbon skeletons necessary for vigorous vegetative growth. Furthermore, temperature fluctuations during different growth periods might influence MgH2 hydrolysis rates and consequently affect H2 and Mg2+ availability, adding another layer of regulation to the observed concentration-dependent effects [42]. Overall, the group b concentration demonstrated the most significant integrated effect at 4 weeks. This was characterized by enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, overall plant biomass, and root secondary metabolite content. It is noteworthy that this enhancement peaked at 4 weeks but subsequently diminished, consistent with the kinetics of H2 release from MgH2 [43]. This observation highlights a potential need for timed re-supply to sustain the effect in practical applications. Importantly, unlike conventional elicitors such as methyl jasmonate (MeJA) [21] or silver ions (Ag+) [25], which often enhance metabolite accumulation at the expense of growth, MgH2 was observed to function as a bifunctional regulator, simultaneously promoting both plant growth and secondary metabolite biosynthesis. The coordinated enhancement of both growth and secondary metabolism suggests a synergistic action of MgH2 hydrolysis products, primarily through H2 signaling and Mg2+ nutrition, although direct mechanistic evidence for their specific signaling pathways is beyond the scope of this initial application study.

Based on the chemical properties of MgH2, its hydrolysis in water to yield H2 and Mg(OH)2, and existing literature, we propose that the observed multifaceted promotive effects are likely mediated synergistically by the released hydrogen molecule (H2) and magnesium ions (Mg2+). H2 has been established as a novel gaseous signaling molecule in plants, regulating diverse processes including seed germination, root development, photosynthesis, and abiotic stress tolerance [28,29,30]. The significant improvements in seed germination rate and root length induced by MgH2 align closely with previously reported physiological effects of H2 [44,45]. Concurrently, the Mg(OH)2 dissolves gradually in soil, releasing Mg2+. As an essential core component of chlorophyll, Mg2+ directly participates in the construction of the photosynthetic apparatus [46]. This mechanism may underpin the significant increases in Pn and ΔC observed in MgH2-treated S. miltiorrhiza seedlings. Beyond magnesium’s fundamental role in chlorophyll structure, the hydrogen gas released from MgH2 hydrolysis may further enhance photosynthetic performance through multiple mechanisms. Previous studies have demonstrated that H2 can increase chlorophyll content by upregulating the expression of chlorophyll biosynthesis genes while suppressing chlorophyll degradation pathways [47,48]. Additionally, H2 has been shown to modulate stomatal conductance through interactions with key signaling molecules such as nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S), thereby improving CO2 uptake and utilization [49]. The combination of improved stomatal conductance from H2 signaling and enhanced chlorophyll synthesis from Mg2+ nutrition may create a synergistic effect that significantly boosts photosynthetic efficiency. This enhanced photosynthetic capacity, in turn, provides increased photoassimilates and energy (ATP and NADPH) that support both growth-related processes and the biosynthetic demands of secondary metabolite production. The improved dry matter accumulation observed in MgH2-treated plants, particularly in roots where bioactive compounds are stored, can be largely attributed to this coordinated enhancement of photosynthetic performance and carbon allocation. This synergistic action via multiple pathways appears crucial for the pronounced promotion of both shoot and root growth, especially the substantial enhancement in root development and biomass accumulation.

To elucidate the molecular basis of MgH2’s regulation of root growth and secondary metabolism, we performed transcriptome sequencing on roots from the highly responsive Group b and Group ck seedlings. Analysis revealed significant alterations in the root gene expression profile following MgH2 treatment. KEGG enrichment analysis highlighted “Metabolic pathways”, “Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites”, and “Plant hormone signal transduction” as major enriched pathways, suggesting potential integration of gene networks governing both growth regulation and metabolic responses by MgH2. Numerous genes associated with growth regulation were upregulated, including GA2ox, YUCCA, CKX, GAPDH, NADPH, and NADH. Among these, GA2ox and CKX, involved in the degradation of gibberellins and cytokinins, respectively, are known to promote root development [50,51,52,53]. YUCCA encodes a key rate-limiting enzyme in auxin biosynthesis [54]. GAPDH, NADPH, and NADH are central to energy metabolism [55,56]. Furthermore, transcription factors and structural genes critically involved in the biosynthesis of phenolic acids (salvianolic acids) and diterpenoids (tanshinones) were significantly upregulated. These include WRKY1, WRKY2, MYC2, HMGS, MVK, CYP76AH1, TAT, HCT, PAL, 4CL, and CYP98A. Notably, WRKY transcription factors are pivotal regulators of tanshinone and salvianolic acid synthesis [57,58,59,60] while MYC2 participates in the jasmonate signaling pathway [61,62], governing secondary metabolite accumulation. Enzymes encoded by PAL, 4CL, and CYP98A are essential in the phenylpropanoid pathway, catalyzing the synthesis of phenolic compounds like Salvianolic acid [63,64]. HMGS and MVK function in the terpenoid backbone pathway, regulating tanshinone biosynthesis [65]. The coordinated upregulation of these genes provides molecular evidence consistent with the observed physiological and biochemical phenotypic alterations. Nevertheless, these transcriptional changes represent one layer of a potentially complex regulatory system, which may also involve post-transcriptional regulation and metabolite feedback mechanisms not captured in this study. For instance, the accumulation of salvianolic acids or tanshinones themselves could potentially exert feedback inhibition on their biosynthetic enzymes or upstream regulators, fine-tuning the metabolic flux. Furthermore, the stability and activity of key biosynthetic enzymes, such as those encoded by PAL, CYP76AH1, and others identified in our transcriptome data, could be subject to regulation through phosphorylation, ubiquitination, or other protein modifications downstream of MgH2-derived signals. The precise regulatory mechanisms underlying the perception, transduction, and integration of H2 and Mg2+ signals to orchestrate downstream gene networks necessitate further functional validation and pathway dissection.

The coordinated responses observed across different organizational levels, spanning from morphological traits to metabolic accumulation, were further confirmed by multivariate clustering analysis (Figures S2 and S3). The clear separation of MgH2-treated groups in both phenotypic and metabolic clustering demonstrates the consistency and system-wide nature of MgH2’s effects, supporting our hypothesis of its dual regulatory function.

In summary, this study reveals the unique potential of MgH2 application in S. miltiorrhiza. Its key advantage over conventional growth regulators or elicitors lies in its association with concurrent enhancement of both growth performance and medicinal quality. This represents a significant advance and an innovative approach towards resolving the persistent “growth-quality trade-off” dilemma in medicinal plant cultivation. It extends the application of MgH2, which was previously studied for preservation or stress resistance in non-medicinal plants, into the realm of medicinal plant cultivation for quality improvement.

As a novel, environmentally friendly additive, the practical application of MgH2 necessitates further research to optimize dosage, timing, and application frequency (considering the temporal limitation of the H2 release), elucidate its long-term stability and transformation in soil, assess potential residue risks, evaluate its impact on soil microbial communities for long-term ecological safety, and investigate its compatibility with other agronomic practices. Furthermore, species-specific responses to MgH2 require evaluation to optimize protocols for different medicinal plants.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that MgH2 application is an effective strategy for synchronously enhancing both the growth and the medicinal quality of Salvia miltiorrhiza. We achieved our objective of investigating MgH2’s effects by showing that it significantly improves seed germination, promotes photosynthetic efficiency and biomass accumulation in seedlings, and substantially increases the root content of pharmaceutically valuable tanshinones and salvianolic acids. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that these promotive effects were accompanied by the upregulation of genes involved in hormone signaling, energy metabolism, and the biosynthesis pathways of these secondary metabolites. Our findings confirm the dual regulatory role of MgH2 and provide a foundational, eco-friendly cultivation technique for the sustainable production of high-quality S. miltiorrhiza.

6. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

While this study demonstrates the promising potential of MgH2 as a novel plant growth regulator for medicinal plants, several limitations should be acknowledged to properly contextualize the findings and guide future research.

First, the potential environmental effects of MgH2 soil application, such as soil pH alteration due to Mg(OH)2 formation and the persistence of residues, were not directly monitored in this pot-based study. Although the hydrolysis product Mg(OH)2 is a mild base and our soil mixture likely provided sufficient buffering capacity, future field-scale studies should systematically measure soil pH, electrical conductivity, and other physicochemical parameters throughout the growth period to fully assess its environmental impact and long-term stability. Second, our observations were conducted over a relatively short-term period (8 weeks) under controlled laboratory conditions. This timeframe, while sufficient to capture significant physiological and transcriptional changes, may not fully represent the long-term effects of MgH2 application on the yield and quality of S. miltiorrhiza across its entire growth cycle, especially under field conditions with fluctuating environmental factors. Therefore, multi-season field trials are essential to validate the efficacy and economic viability of this approach. Third, the present work focused exclusively on the species-specific response of S. miltiorrhiza. The transferability of these findings to other medicinal plants remains an open question. Given that the proposed mechanism involves fundamental processes like H2 signaling and Mg2+ nutrition, which are conserved across plant species, it is plausible that MgH2 could benefit a wider range of medicinal species. However, the optimal concentration and timing of application are likely to vary. Future research should therefore explore the effects of MgH2 on other high-value medicinal plants with different metabolic profiles and growth habits to determine the broader applicability of this strategy.

In conclusion, addressing these limitations in future work will be crucial for transitioning MgH2 from a promising laboratory discovery to a reliable, eco-friendly tool for the sustainable cultivation of medicinal plants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121499/s1. Figure S1: Phenotypic responses of Salvia miltiorrhiza seedlings to MgH2 treatment. Figure S2: Hierarchical clustering analysis of phenotypic traits in S. miltiorrhiza seedlings under MgH2 treatment. Figure S3: Hierarchical clustering analysis of bioactive compound accumulation in S. miltiorrhiza roots under MgH2 treatment. Figure S4: Heat map of differentially expressed transcripts analysis (4-week Group b vs. Group ck). Figure S5: Volcano plots analysis of up- and down-regulated differentially expressed genes associated with MgH2 treatment (4-week Group b vs. Group ck). Figure S6: GO biological process and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of genes associated with MgH2 treatment (4-week Group b vs. Group ck). Figure S7: PCA score plots with each point representing an independent biological replicate. Figure S8: qRT-PCR validation of significant DEGs. Table S1: Complete ANOVA results (F-values, degrees of freedom, and p-values) for all major phenotypic traits and metabolite contents. Table S2: Primer used in this research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L., Y.Z. and D.Y.; methodology, J.L. and X.D.; software, G.A.; validation, Y.L. (Yang Liu), Y.L. (Yihong Li) and I.Y.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and H.Y.; investigation, W.L., X.D. and H.Z.; resources, D.Y.; data curation, J.L. and G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, W.L., H.Z. and D.Y.; visualization, Y.L. (Yang Liu); supervision, D.Y.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, D.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers LMS25C020001 and LD25H280001), the Key Project of the Central Government: Capacity Building of Sustainable Utilization of Traditional Chinese Medicine Resources (Grant Number 2060302), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 32201819), and the Key Scientific and Technological Grant of Zhejiang for Breeding New Agricultural Varieties (Grant Number 2021C02074). The APC was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China Grant Numbers LMS25C020001.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenjiang Ding’s group from Shanghai Jiao Tong University for providing the magnesium hydride (MgH2) reagent.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Dongfeng Yang was employed by the Shaoxing Biomedical Research Institute of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that there search was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Xiang, C.; Yuan, C.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; et al. MetaDb: A database for metabolites and their regulation in plants with an emphasis on medicinal plants. Mol. Hortic. 2024, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Lou, G.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Guo, J.; Qi, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, G.; Xu, S.; et al. Unveiling the spatial distribution and molecular mechanisms of terpenoid biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza and S. grandifolia using multi-omics and DESI–MSI. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Xiang, Z.; Ye, T.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, Z. Antioxidant activities of Salvia miltiorrhiza and Panax notoginseng. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, D.; Lou, H.; Sun, L.; Ji, J. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory activities of tanshinones isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza var. alba roots in THP-1 macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 188, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.-S.; Wang, Z.-G. Salvianolic acid B from Salvia miltiorrhiza bunge: A potential antitumor agent. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1042745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Fu, L.; Nile, S.H.; Zhang, J.; Kai, G. Salvia miltiorrhiza in Treating Cardiovascular Diseases: A Review on Its Pharmacological and Clinical Applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Hong, X.; You, H.; Zhang, R.; Liang, Z.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, M.; et al. DNA methylation regulates biosynthesis of tanshinones and phenolic acids during growth of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant Physiol. 2023, 194, 2086–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, I.; Kim, H.; Moon, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, B. Overview of Salvia miltiorrhiza as a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Various Diseases: An Update on Efficacy and Mechanisms of Action. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Lin, C.; Xing, P.; Fen, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhou, C.; Gu, Y.Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X. A high-quality reference genome sequence of Salvia miltiorrhiza provides insights into tanshinone synthesis in its red rhizomes. Plant Genome 2020, 13, e20041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Song, J.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Song, C.; Wang, B.; et al. Analysis of the Genome Sequence of the Medicinal Plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 949–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, J.; Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, R.; Li, X.; Song, Z.; et al. One-Step Regeneration of Hairy Roots to Induce High Tanshinone Plants in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 913985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lu, S. Genetic Transformation of Salvia miltiorrhiza. In The Salvia miltiorrhiza Genome. Compendium of Plant Genomes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.-P.; Wang, Z.-Z. Genetic transformation of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated method. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2007, 88, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alok, A.; Jain, P.; Kumar, J.; Yajnik, K.; Bhalothia, P. Genome engineering in medicinally important plants using CRISPR/Cas9 tool. In Genome Engineering via CRISPR-Cas9 System; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S. Biosynthesis and Regulatory Mechanisms of Bioactive Compounds in Salvia miltiorrhiza, a Model System for Medicinal Plant Biology. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2021, 40, 243–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; He, C.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Li, M.; Zhou, X.; Xu, M.; He, X. Impacts of fertilization methods on Salvia miltiorrhiza quality and characteristics of the epiphytic microbial community. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1395628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Han, T.; Liu, C.; Sun, P.; Liao, D.; Li, X. Deciphering the effects of genotype and climatic factors on the performance, active ingredients and rhizosphere soil properties of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1110860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, P.; Pu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Y. A comprehensive analytical platform for unraveling the effect of the cultivation area on the composition of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 145, 111952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-D.; Cen, Y.-S.; Yu, Y.-G.; Qi, Z.-C.; Yang, D.-F.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Hou, Z.-N.; Liang, Z.-S. Simultaneous Determination of 17 Constituents of Chinese Wild Radix Salvia miltiorrhiza from Different Geographical Areas by Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. Curr. Pharm. Anal. 2020, 16, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hong, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Hou, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yang, D. Transcriptomic analysis provides insight into the regulation mechanism of silver ions (Ag+) and jasmonic acid methyl ester (MeJA) on secondary metabolism in the hairy roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge (Lamiaceae). Med. Plant Biol. 2023, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Wan, G.; Liang, Z. Accumulation of salicylic acid-induced phenolic compounds and raised activities of secondary metabolic and antioxidative enzymes in Salvia miltiorrhiza cell culture. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 148, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Li, Y.; Su, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, L.; Yang, D.; Liang, Z. The exploration of methyl jasmonate on the tanshinones biosynthesis in hair roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge and Salvia castanea f. tomentosa Stib. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 167, 113563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.-S.; Yang, D.-F.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.-H. Roles of reactive oxygen species in methyl jasmonate and nitric oxide-induced tanshinone production in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 31, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Liao, P.; Nile, S.H.; Georgiev, M.I.; Kai, G. Biotechnological Exploration of Transformed Root Culture for Value-Added Products. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ning, D.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, R.; Huang, L. Comparative proteomic analysis of the response to silver ions and yeast extract in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy root cultures. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 107, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, G.; Su, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Ma, G.; Han, J. Effect of CeO2, TiO2 and SiO2 nanoparticles on the growth and quality of model medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza by acting on soil microenvironment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 280, 116552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J. Metal hydrides as hydrogen storage media and their applications. Hydrog. Technol. Implicat. 2018, 1, 13–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Cheng, P.; Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Zou, J.; Shen, W. Magnesium hydride confers copper tolerance in alfalfa via regulating nitric oxide signaling. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Cao, J.; Lu, J.; Xu, X.; Wu, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Exogenous MgH2-derived hydrogen alleviates cadmium toxicity through m6A RNA methylation in rice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Yao, W.; Cheng, X.; Wang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Shen, W. Magnesium Hydride Confers Osmotic Tolerance in Mung Bean Seedlings by Promoting Ascorbate–Glutathione Cycle. Plants 2024, 13, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, L.; Feng, L.; Tie, J.; Liao, W. Hydrogen gas: A potential novel tool to enhance abiotic stress tolerance in plant. Plant Stress 2025, 17, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohra, A.; Sanadhya, D.; Shukla, A. Synthesis, characterization of Mg(OH)2 nanoparticles and its effect on photosynthetic efficiency in two cultivars of Brassica juncea germinated under cadmium toxicity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Biotechnology & Nanobiotechnology, Gwalior, India, 10–12 February 2016; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, C.; Xiao, W.; Hao, H.; Xiaoqing, L.; Chao, L.; Lei, Z.; Fashui, H. Effects of Mg2+ on spectral characteristics and photosynthetic functions of spinach photosystem II. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2009, 72, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zou, J.; Ding, W.; Shen, W. Magnesium Hydride-Mediated Sustainable Hydrogen Supply Prolongs the Vase Life of Cut Carnation Flowers via Hydrogen Sulfide. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 595376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zou, J.; Ding, W.; Du, H.; Shen, W. Magnesium hydride acts as a convenient hydrogen supply to prolong the vase life of cut roses by modulating nitric oxide synthesis. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 177, 111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Qi, Y.; Chu, S.; Ma, Y.; Xu, L.; Lv, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, D.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Endophytic fungus Cladosporium tenuissimum DF11, an efficient inducer of tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza roots. Phytochemistry 2022, 194, 113021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Qiu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Yu, H.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Abozeid, A.; Xia, P.; Zhang, L.; et al. A novel synergistic regulatory mechanism involving the MYB39-MYB111-bHLH51-TTG1 module in the phenolic and diterpenoid biosynthetic pathways of Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 4367–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-D.; Yu, Y.-G.; Yang, D.-F.; Qi, Z.-C.; Liu, R.-Z.; Deng, F.-T.; Cai, Z.-X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.-F.; Liang, Z.-S. Chemotaxonomic variation in secondary metabolites contents and their correlation between environmental factors in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge from natural habitat of China. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 113, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Duan, X.; Yao, P.; Cui, W.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Q.; Chen, J.; Dai, T.; Shen, W. Hydrogen Gas Is Involved in Auxin-Induced Lateral Root Formation by Modulating Nitric Oxide Synthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, K.; Su, J.; Lu, R.; Lu, R.; Zhao, G.; Cui, W.; Wang, R.; Mu, H.; Cui, J.; Shen, W. Hydrogen-induced tolerance against osmotic stress in alfalfa seedlings involves ABA signaling. Plant Soil. 2019, 445, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Jiao, J.; Li, J.; Song, Z.; Zhang, B. The GA and ABA signaling is required for hydrogen-mediated seed germination in wax gourd. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbovytskyy, Y.; Berezovets, V.; Kytsya, A.; Zavaliy, I.; Yartys, V. Hydrogen Generation by the Hydrolysis of MgH2. Mater Sci. 2020, 56, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.K.; Lee, N.S.; Jeong, Y.G.; Jeong, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Yoo, Y.C.; Han, S.Y. Magnesium hydride attenuates cognitive impairment in a rat model of vascular dementia. Anat. Biol. Anthropol. 2020, 33, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Liao, W. Hydrogen Gas Improves Seed Germination in Cucumber by Regulating Sugar and Starch Metabolisms. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chu, S.; Zhou, P. A critical review for hydrogen application in agriculture: Recent advances and perspectives. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 54, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tränkner, M.; Tavakol, E.; Jákli, B. Functioning of potassium and magnesium in photosynthesis, photosynthate translocation and photoprotection. Physiol. Plant. 2018, 163, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Yang, Z.; Shi, L.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; Song, W. Hydrogen-rich water delays post-harvest yellowing in broccoli by inhibiting ethylene and ABA levels, thereby reducing chlorophyll degradation and carotenoid accumulation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 228, 113661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, S.; Zheng, Y. Research Progress of Hydrogen Rich Water in Preservation of Postharvest Horticultural Products: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 9478–9488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lai, D.; Wang, Q.; Shen, W. Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent Nitric Oxide Production Contributes to Hydrogen-Promoted Stomatal Closure in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, J.; Ma, C.; Kadmiel, M.; Gai, Y.; Strauss, S.; Jiang, X.; Busov, V. Tissue-specific expression of Populus C19 GA 2-oxidases differentially regulate above- and below-ground biomass growth through control of bioactive GA concentrations. New Phytol. 2011, 192, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.-F.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chen, K.-T.; Hsing, Y.-I.; Zeevaart, J.A.; Chen, L.-J.; Yu, S.-M. A Novel Class of Gibberellin 2-Oxidases Control Semidwarfism, Tillering, and Root Development in Rice. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 2603–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramireddy, E.; Nelissen, H.; Leuendorf, J.E.; Van Lijsebettens, M.; Inzé, D.; Schmülling, T. Root engineering in maize by increasing cytokinin degradation causes enhanced root growth and leaf mineral enrichment. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 106, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Li, Y.; Zhai, L.; Li, W.; Kumar, R.; Yer, H.; Duan, H.; Cheng, B.; Deng, Z.; Li, Y. Root predominant overexpression of iaaM and CKX genes promotes root initiation and biomass production in citrus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2023, 155, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Christensen, S.K.; Fankhauser, C.; Cashman, J.R.; Cohen, J.D.; Weigel, D.; Chory, J. A Role for Flavin Monooxygenase-Like Enzymes in Auxin Biosynthesis. Science 2001, 291, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Knuesting, J.; Birkholz, O.; Heinisch, J.J.; Scheibe, R. Cytosolic GAPDH as a redox-dependent regulator of energy metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Wang, R.-S.; Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox Couples and Cellular Energy Metabolism. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.-Q.; Li, W.-R.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Liang, Z.-S. Transcriptional activity and subcellular location of SmWRKY42-like and its response to gibberellin and ethylene treatments in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Chin. Herb. Med. 2018, 10, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Hao, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Kai, G. Transcription Factor SmWRKY1 Positively Promotes the Biosynthesis of Tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Hao, X.; Shi, M.; Fu, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Feng, Y.; Makunga, N.P.; Kai, G. Tanshinone production could be increased by the expression of SmWRKY2 in Salvia miltiorrhiza hairy roots. Plant Sci. 2019, 284, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Guo, W.; Yang, D.; Hou, Z.; Liang, Z. Transcriptional Profiles of SmWRKY Family Genes and Their Putative Roles in the Biosynthesis of Tanshinone and Phenolic Acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Lv, B.; Shao, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, M.; Zuo, A.; Wei, J.; Dong, J.; Ma, P. The SmMYC2–SmMYB36 complex is involved in methyl jasmonate-mediated tanshinones biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant J. 2024, 119, 746–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, N.; Yang, J.; Zhou, D.; Yuan, S.; Pan, X.; Jiang, C.; Wu, Z. CwJAZ4/9 negatively regulates jasmonate-mediated biosynthesis of terpenoids through interacting with CwMYC2 and confers salt tolerance in Curcuma wenyujin. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 3090–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, B.; Liang, L.; Huang, Z.; Fan, W.; Chen, J.; He, W.; Chen, H.; Huang, L.; et al. Insights into salvianolic acid B biosynthesis from chromosome-scale assembly of the Salvia bowleyana genome. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Duan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Li, Q.; Yu, L.; Han, C.; Huo, J.; Chen, W.; Xiao, Y. CYP98A monooxygenases: A key enzyme family in plant phenolic compound biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, P.; Liu, J.; Osbourn, A.; Dong, J.; Liang, Z. Regulation and metabolic engineering of tanshinone biosynthesis. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 18137–18144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).