Abstract

Anthocyanins are important secondary metabolites that impart color to fruits, and their biosynthesis is regulated by light. AP2/ERF transcription factors represent one of the largest TF families in plants and play pivotal roles in regulating plant growth and development, secondary metabolism, and stress responses. However, their comprehensive profile in mango (Mangifera indica L.) and their role in mango anthocyanin biosynthesis remain largely unclear. In this study, genome-wide identification and analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in mango were conducted. A total of 240 family members were identified and classified into five subfamilies. Phylogenetic tree, conserved motif, and gene structure analyses revealed high conservation within the same subfamily and significant divergence among different subfamilies. Synteny analysis indicated that segmental and tandem duplication events played a major role in the expansion of the MiAP2/ERF family. Organ-specific expression profiles based on RNA-seq data uncovered the expression patterns of MiAP2/ERF genes in different plant organs. Furthermore, RNA-seq analyses related to light-induced anthocyanin accumulation, including preharvest “bagging–debagging” treatment and postharvest UV-B/white light and blue light treatments, identified a subset of MiAP2/ERF genes with significant light-responsive trends. The expression patterns of six blue-light-induced MiAP2/ERF genes were validated by means of qPCR. In summary, this study provides a comprehensive theoretical characterization of the AP2/ERF family in mango and reveals its potential role in light-induced anthocyanin accumulation, thereby establishing a solid theoretical foundation for subsequent investigations into gene functions and molecular mechanisms.

1. Introduction

Mango (Mangifera indica L.) is a popular tropical fruit worldwide. It is extensively cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions. Fruit color is a crucial fruit quality attribute, with red-skinned cultivars often being more desirable to customers [1]. This red pigmentation results from the accumulation of anthocyanins, primarily cyanidin-3-O-galactoside and peonidin-3-O-glucoside [2,3].

Anthocyanins are water-soluble pigments that impart red, purple, and blue colors in plants [4]. Their biosynthesis occurs through the phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathways, involving key enzymes such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), dihydroflavonol reductase (DFR), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), and UDP-glucose: flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (UFGT) [4]. The expression of these structural genes is primarily regulated by an MYB-bHLH-WD40 transcription factor (TF) complex [5]. Related studies have been reported in species such as Arabidopsis thaliana, soybean (Glycine max), strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa), and Cerasus humilis [6,7,8,9].

The APETALA2/ethylene response factor (AP2/ERF) superfamily represents one of the largest TF families in plants, characterized by a conserved AP2/ERF DNA-binding domain of approximately 60-70 amino acids [10]. This family is divided into five subfamilies: AP2 (APETALA2), RAV (related to ABI3/VP1), ERF, DREB (Dehydration Responsive Element Binding), and Soloist. The AP2-subfamily proteins contain two AP2 domains, while RAV members possess one AP2 domain and one B3 domain [11]. Both the ERF and DREB subfamilies contain a single AP2 domain; they are distinguished by key amino acid residues at the 14th and 19th positions of the AP2/ERF domain, with ERF having alanine (Ala) and aspartate (Asp) and DREB having valine (Val) and glutamic acid (Glu), respectively [12]. The Soloist subfamily, also with one AP2 domain, is phylogenetically distinct and exhibits significant differences in gene structure [13].

Since the initial isolation of the AP2 gene in Arabidopsis [14], genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF family has been conducted in numerous plant species, including Arabidopsis [15], rice [15], wheat [16], poplar [17], grapevine [18], apple [19], and citrus [20]. These TFs are known to play pivotal roles in plant growth, development (e.g., flower, seed, and root development and fruit ripening) [14,21,22,23,24,25,26], and responses to various abiotic stresses, such as drought, chilling, and heat [27,28,29].

Accumulating evidence also underscores the importance of AP2/ERF members in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis. In pear, Pp4ERF24 and Pp12ERF96 interact with PpMYB114 to enhance MBW complex formation, thereby promoting anthocyanin biosynthesis. Conversely, PpERF105 and PpERF9 repress anthocyanin biosynthesis by inducing the repressor PpMYB140 or inhibiting PpMYB114, respectively [30,31,32]. In strawberry, FaRAV1 activates the expression of both structural genes (CHS, F3H, DFR, and GT1) and the regulatory gene MYB10, leading to increased anthocyanin biosynthesis [33]. For fruits that, like mango, belong to the climacteric type, such as apple, the transcription factor MdAP2_1a positively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by binding to the promoter of MdMYB10 and interacting with its protein product [34]. Similarly, in Actinidia arguta, AzERF059 promotes anthocyanin accumulation by mediating the auxin pathway and regulating AaGH3 [35]. Despite these advances in other species, the AP2/ERF gene family in mango and its potential role in anthocyanin regulation remain largely unknown.

In this study, we performed genome-wide identification and characterization of the AP2/ERF superfamily in mango. Our analysis included subfamily classification, an examination of gene structures and conserved motifs, and synteny analysis. Furthermore, we investigated the expression profiles of these genes across different organs and during light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis using RNA-seq and quantitative PCR (qPCR). Our findings provide a foundation for future functional studies of the AP2/ERF family in mango, particularly its role in controlling a key fruit quality trait.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Analysis of AP2/ERF Genes in Mango

The whole-genome sequence and GFF annotation information file of mango were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), under the bio-project accession number PRJNA487154 [36]. The IDs of all Arabidopsis thaliana AP2/ERF (AtAP2/ERF) family members were obtained from a previous report [15]. Subsequently, the protein sequences of all AtAP2/ERF members were downloaded in bulk using the “Sequence Bulk Download” function on the TAIR website (https://v2.arabidopsis.org/tools/bulk/sequences/index.jsp accessed on 20 November 2024). Using these AtAP2/ERF protein sequences as queries, a comparative analysis was performed against the complete mango proteome using the “Protein BLAST” (v2.17.0) function both in TBtools (v2.124) and on the NCBI website. Redundant sequences were manually removed to complete the preliminary screening. All initially screened mango protein sequences were then submitted to the “Batch CD-search” tool on the NCBI website for a systematic analysis of conserved domains. Through manual inspection, proteins containing complete AP2 conserved domains were identified as potential members of the MiAP2/ERF family. The longest transcript of each potential MiAP2/ERF member was subsequently obtained using TBtools. A total of 240 candidate proteins were ultimately selected for further analysis. These 240 MiAP2/ERF family members were renamed sequentially from MiAP2/ERF1 to MiAP2/ERF240 based on their gene ID numbers in ascending order, and these names were assigned as gene names for subsequent analyses.

2.2. Physicochemical Property Analysis and Subcellular Localization Prediction of MiAP2/ERF Proteins

The “Protein Parameter Calc” function in TBtools was used to analyze the physicochemical properties of the 240 MiAP2/ERF proteins, including the number of amino acids, molecular weight, theoretical pI, instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY). Following this, the online tool WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/ accessed on 16 May 2025) was employed to predict the subcellular localization of the MiAP2/ERF proteins.

2.3. Construction of the MiAP2/ERF Phylogenetic Tree and Analysis of Conserved Motifs and Gene Structures

The protein sequences of the 240 MiAP2/ERF members and all previously downloaded AtAP2/ERF proteins were aligned using the MUSCLE algorithm in MEGA 11 software. Subsequently, a phylogenetic tree was constructed from the alignment results using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method. The “Bootstrap” value was set to 1000, and all other parameters were set to their defaults. The resulting phylogenetic tree was exported as a Newick format file and submitted to the Evolview website (http://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/ accessed on 21 May 2025) for visualization and refinement [37]. Conserved motif analysis of the 240 MiAP2/ERF proteins was conducted using the online tool MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme accessed on 17 December 2024), with the maximum number of motifs set to 10 and other parameters set to their default values. Based on the mango genome GFF annotation file, the gene structures of the MiAP2/ERF genes were visualized using the “Visualize Gene Structure” function in TBtools.

2.4. Chromosomal Localization and Collinearity Analysis

We performed synteny analysis, a method that compares chromosomal gene order between species to reveal evolutionarily conserved regions. The chromosomal distribution of the 240 MiAP2/ERF genes was determined using TBtools, based on the mango genome GFF annotation file. Intraspecific collinearity analysis within mango and interspecific collinearity analysis with other species (Arabidopsis thaliana and Prunus persica) were both performed using the MCscan X plugin built into TBtools [38]. The Ka/Ks values were calculated utilizing the “Simple Ka/Ks Calculator (NG)” function in TBtools.

2.5. RNA-Seq Expression Pattern Analysis

This study utilized four RNA-seq datasets for expression pattern analysis. The organ-specific RNA-seq data for the “Alphonso” mango cultivar (including leaf, bark, seed, root, flower, peel, and flesh) were downloaded from the NCBI database (accession: PRJNA48715). The other three RNA-seq datasets were generated from previous work by our research team: the peel RNA-seq data from the “Guifei” mango cultivar under postharvest UV-B/white light (PRJNA1084921) and blue light (PRJNA854296) treatments were publicly published [39,40], and the remaining RNA-seq data from the “bagging–debagging” experiment on “Guifei” mango have not yet been published. The samples from each time point and group contained three biological replicates. First, the low-quality data in the raw reads were filtered and removed using Fastp (v0.20.0) software. Simultaneously, low-quality reads (Q ≤ 20) were removed to obtain clean reads. Subsequently, TopHat was used to align them to the mango reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_011075055.1/ accessed on 15 December 2023) [41]. Cufflinks was utilized to assemble the transcripts, and gene expression levels are represented in FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per million fragments mapped). Differential expression analysis between different sample groups was performed using the DESeq R package (1.10.1). Genes meeting the conditions of p-value < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 1 were considered differentially expressed genes (DEGs). In the construction of the final heatmaps, the mean value of the three biological replicates for each group was used for representation, and we excluded lowly expressed genes (those with an FPKM value for each time period of less than 10) from the three treatment datasets but retained all genes in the organ-specific dataset. Finally, the “HeatMap” function in TBtools was employed to visualize the expression patterns of MiAP2/ERF genes across the different RNA-seq datasets. The data underwent normalization processing using Row scale Normalized.

2.6. Plant Material and Treatment

Postharvest UV-B/white-light-treated mango fruits (cv. Guifei) were harvested from a commercial orchard located in Yazhou District, Sanya City, Hainan Province, China. The fruits were placed in a growth chamber (Boxun, BIC-400, Shanghai, China) maintained at 17 °C and 80% humidity for different treatments. The treatment group received mixed irradiation from a UV-B light source (SANKYO DENKI, G15T8E, 312 nm, Tokyo, Japan) and a white light source (NVC, EGZZ1001, Huizhou, China), with irradiance levels set at 9.0 μW cm−2 for UV-B and 40.0 W m−2 for white light, while the control group was kept in complete darkness. The treatment was applied continuously for 24 h per day. Sampling of mango peel was conducted at 0, 7, and 14 d (days) of treatment. For the treatment group, peel samples were taken from the irradiated side of the fruit, while for the control group, sampling was performed randomly on the fruit surface. The collected peel samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then transferred to an ultra-low-temperature freezer at −80 °C for subsequent experimental analysis. The experimental procedures were described in detail in a previous study [39]. The specific methodology for postharvest blue light treatment on “Guifei” mango fruits was also documented in an earlier publication [40]. Briefly, mango fruits harvested from a commercial orchard were divided into two groups of uniform size and healthy condition. One group was subjected to blue light irradiation (wavelength 453.2 nm, intensity 110 μmol/m2/s) as the treatment group, while the other group was kept in darkness as the control group. Mango peel samples were collected at 0, 6, 24, 72, 144, and 216 h (hours) of treatment using the same sampling method as described for the UV-B/white light experiment. The samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored in an ultra-low-temperature freezer for subsequent experimental analysis.

2.7. RNA Extraction and qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from mango peel using a Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (Tiangen, DP441, Beijing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and concentration of the extracted total RNA were measured with a NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Subsequently, 1 µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA (complementary DNA) using the HiScript III All-in-one RT SuperMix Kit (Vazyme, R333, Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The synthesized cDNA (50 ng/µL) was diluted 20-fold with nuclease-free water and used as the template for qPCR. The qPCR reactions were performed in a total volume of 15 µL, containing 5.5 µL of diluted cDNA (a total of 13.75 ng), 1 µL of each forward and reverse primer (10 µM), and 7.5 µL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ II (Takara, Kyoto, Japan). The amplification program was set as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. All reactions were carried out in a real-time PCR system (qTOWER3 G, Jena, Germany). The relative expression levels of the target genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with the mango β-actin gene serving as the internal reference for normalization. All samples were analyzed in three biological replicates.

2.8. Primer Design and Synthesis

All qPCR primers were designed using the online platform Primer3 (https://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/ accessed on 16 June 2025). The initially designed primers were subsequently checked for specificity using the built-in “Primer Check” function in TBtools software [42].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test in SPSS software (version 27.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 (*) and highly significant at p < 0.01 (**).

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of MiAP2/ERF Proteins

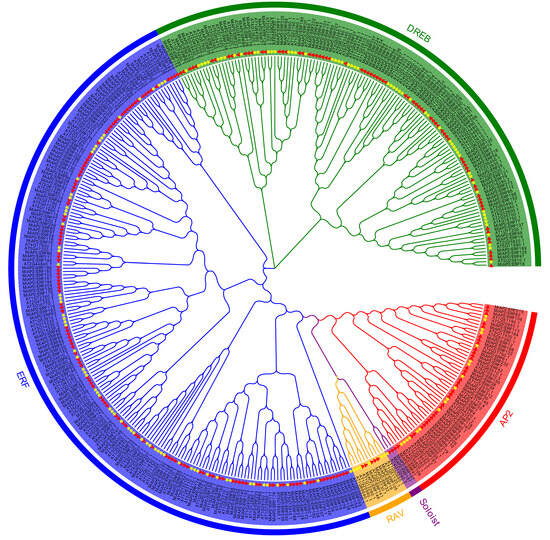

A total of 240 MiAP2/ERFs were identified from the mango genome and were named MiAP2/ERF1 to MiAP2/ERF240 in ascending gene ID order. The number of amino acids ranged from 120 (MiAP2/ERF15 and MiAP2/ERF100) to 742 (MiAP2/ERF184), with corresponding molecular weights ranging from 13.20 kDa to 81.46 kDa (File S1). A phylogenetic tree constructed with these MiAP2/ERFs and Arabidopsis AtAP2/ERFs classified them into five subfamilies: AP2 (34 genes), RAV (5 genes), ERF (126 genes), DREB (73 genes), and Soloist (2 genes) (Figure 1 and File S1).

Figure 1.

The phylogenetic tree of the identified MiAP2/ERF proteins. The Arabidopsis thaliana AP2/ERF proteins (AtAP2/ERFs) were used as representative references for the defined subfamilies. Mangifera indica AP2/ERF proteins (MiAP2/ERFs) are marked with red triangles, while AtAP2/ERFs are indicated by yellow five-pointed stars. Distinct subfamilies are highlighted by different colored backgrounds. In the figure, different subfamilies are color-coded as follows: red for AP2, green for DREB, blue for ERF, orange for RAV, and purple for Soloist.

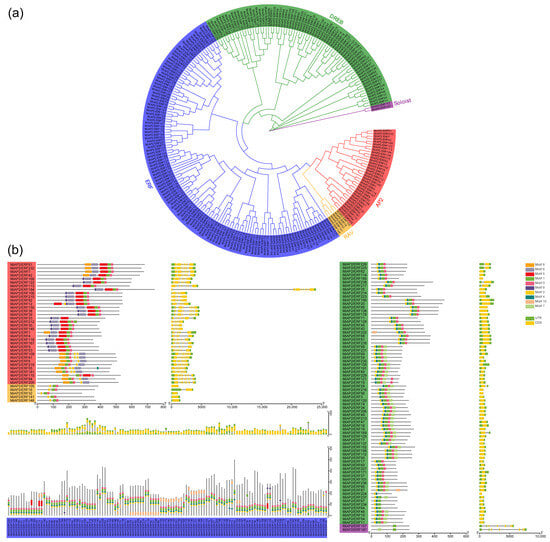

3.2. Gene Structure and Conserved Motif Analysis of MiAP2/ERF Proteins

Conserved motif analysis showed that most MiAP2/ERF members contained both motif 1 and motif 3, which represent the AP2 domain, except for the two Soloist genes, which contained only motif 1 (Figure 2). The AP2 subfamily exhibited specific motifs, including motifs 8, 6, 9, and 5, while motifs 2 and 4 were present in most genes from the ERF and DREB subfamilies (Figure 2). Motif 7 was mainly found in the DREB subfamily (Figure 2). Genes within the same subfamily generally exhibited similar motif types and distribution patterns. For instance, most ERF and DREB members showed a similar motif order (motifs 2, 4, 1, and 3), and all five RAV members consisted of motifs 2, 1, and 3 from the N-terminus to the C-terminus (Figure 2). Gene structure analysis revealed that the AP2 and Soloist subfamilies contained more introns than the ERF, DREB, and RAV subfamilies (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship, conserved motifs, and gene structure of MiAP2/ERFs. (a) Phylogenetic tree constructed based on full-length protein sequences of MiAP2/ERFs. Different colored backgrounds represent distinct subfamilies. (b) Conserved motifs and gene structure of MiAP2/ERFs. In the figure, different subfamilies are color-coded as follows: red for AP2, green for DREB, blue for ERF, orange for RAV, and purple for Soloist.

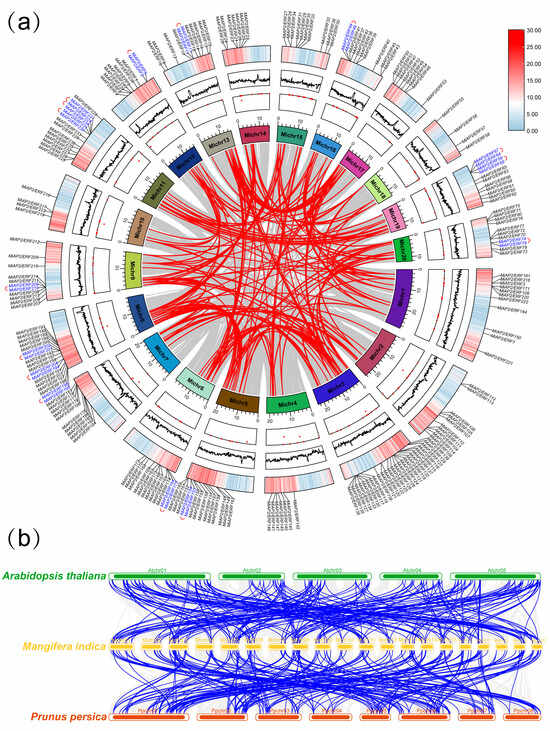

3.3. Chromosomal Distribution and Syntenic Analysis of MiAP2/ERF Genes

Based on the genome annotation, the 240 MiAP2/ERF genes were mapped onto the mango chromosomes. Among them, 23 genes (MiAP2/ERF81 to MiAP2/ERF103) were located on scaffold chromosomes, likely due to incomplete genome assembly; the remaining 217 genes were distributed across all 20 chromosomes (Supplementary File S1, Figure 3a). Chromosome 3 harbored the most genes (25), followed by chromosome 8 (18); chromosomes 5 and 11 (14 each); chromosome 6 (12); chromosomes 1, 9, 13, 19, and 20 (11 each); chromosomes 2, 7, 15, and 16 (10 each); chromosome 12 (9 genes); chromosome 17 (8 genes); chromosomes 4 and 14 (7 each); and chromosomes 10 and 18 (4 each) (Supplementary File S1, Figure 3a). Intraspecific collinearity analysis revealed 190 segmental duplicate pairs and 16 tandem duplicate pairs within the MiAP2/ERF gene family. Notably, two of the tandem duplication events involved genes located on scaffold chromosomes (Supplementary Files S2 and S3 and Figure 3a). Interspecific collinearity analysis identified 234 homologous gene pairs between mango and Arabidopsis thaliana and 253 pairs between mango and peach. These similar numbers of homologous pairs suggest relatively close evolutionary relationships between mango and these two species (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Analysis of homologous relationships among MiAP2/ERF genes. (a) Intraspecific collinearity analysis of MiAP2/ERF gene family in mango. Segmental duplication pairs are highlighted by red connecting lines between MiAP2/ERF genes, while tandem duplication pairs are indicated by blue connecting lines. (b) Interspecific collinearity analysis of AP2/ERF genes between mango and Arabidopsis thaliana and peach. Homologous gene pairs are connected by blue lines.

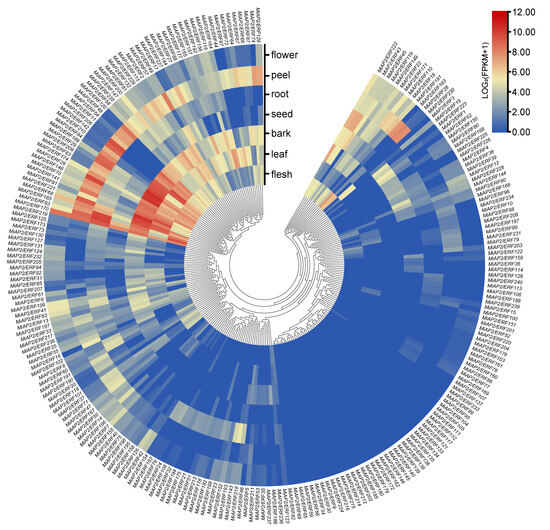

3.4. Organ-Specific Expression Profiling of MiAP2/ERF Genes

An analysis of transcriptome data from the “Alphonso” mango revealed that the expression patterns of the 240 MiAP2/ERF genes across different organs (flower, peel, root, seed, bark, leaf, and flesh) could be categorized into three groups. The first group consisted of genes with high expression in most organs; the second group contained genes specifically highly expressed in certain organs; and the third group showed nearly no expression in all organs (Figure 4). Among these, MiAP2/ERF170 exhibited high expression levels across all mango organs, suggesting a potential fundamental role in mango growth and development (Figure 4). Furthermore, MiAP2/ERF genes within Group I generally showed high expression in the peel, indicating their potential primary involvement in mango peel morphogenesis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of the expression profiles of 240 MiAP2/ERF genes across different organs. The color bar represents expression values, ranging from low (blue) to high (red).

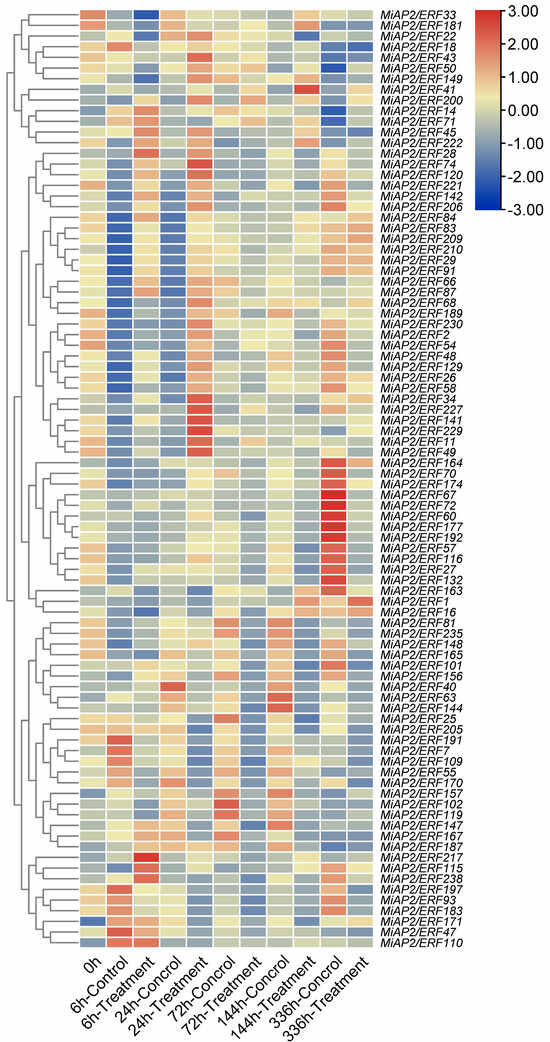

3.5. Analysis of MiAP2/ERF Gene Expression Patterns in Mango Peel Subjected to Preharvest “Bagging–Debagging” Treatment

Transcriptomic analysis of the preharvest “bagging–debagging” treatment revealed that, compared to the bagged control, a set of genes, comprising MiAP2/ERF200, 14, 45, 222, 28, 74, 120, 221, 142, 206, 84, 83, 209, 210, 29, 91, 66, 87, 217, and 115, were significantly upregulated at both 6 and 24 h after debagging. In contrast, another set of genes, comprising MiAP2/ERF68, 189, 230, 2, 54, 48, 129, 26, 58, 34, 227, 141, 229, 11, and 49, showed no significant upregulation at 6 h but were markedly upregulated at 24 h post-debagging (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Transcriptomic analysis of MiAP2/ERF genes in mango peel under “bagging–debagging” treatment. Expression is shown for treatment and control conditions at multiple time points (0, 6, 24, 72, 144, 336 h) based on RNA-seq data.

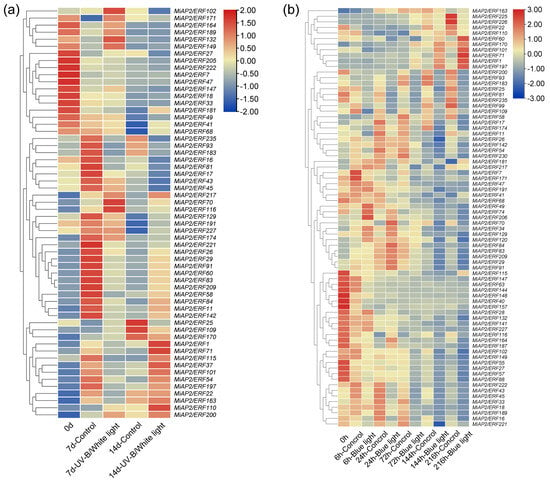

3.6. Analysis of MiAP2/ERF Gene Expression Patterns Under UV-B/White Light and Blue Light Treatments

We analyzed the expression patterns of MiAP2/ERF genes under postharvest light induction using RNA-seq data. Under UV-B/white light treatment, genes MiAP2/ERF217, 70, 116, and 200 exhibited higher expression levels at both 7 and 14 days compared to the dark control (Figure 6a). Specifically, MiAP2/ERF102, 171, 164, 189, 132, and 149 showed elevated expression only at the earlier stage (7 days), whereas MiAP2/ERF1, 71, 115, 37, 101, 54, and 197 were significantly upregulated specifically at the later stage (14 days) (Figure 6a). Under blue light treatment, the expression levels of MiAP2/ERF74, 206, 70, 34, 129, 120, and 84 were significantly induced during the early stages (6 and 24 h) (Figure 6b). In contrast, MiAP2/ERF170, 101, 71, 1, and 197 exhibited markedly higher expression during the later stages of treatment (72, 144, and 216 h) (Figure 6b). Notably, MiAP2/ERF70, 1, 71, 101, and 197 were consistently upregulated in response to postharvest light induction in both transcriptomic analyses (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

RNA-seq profiling of MiAP2/ERF gene expression in “Guifei” mango peel under UV-B/white light (a) and blue light (b) treatments. Expression is shown for treatment and control conditions at multiple time points ((a): 0, 7, and 17 d; (b): 0, 6, 24, 72, 144, and 216 h) based on RNA-seq data.

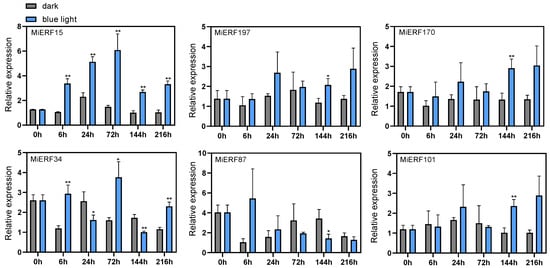

3.7. qPCR Analysis of MiAP2/ERF Expression Patterns During Blue-Light-Induced Anthocyanin Accumulation in Mango

Based on the transcriptomic data from blue-light-treated mango peel (Supplementary File S5), six MiAP2/ERF genes responsive to blue light were selected for validation qPCR. The results revealed that blue light induction triggered an overall upregulation of four genes—MiAP2/ERF15, 197, 170, and 101—compared to the control group, with MiAP2/ERF15 showing the most pronounced response. In contrast, MiAP2/ERF34 expression was induced at 6 h post-treatment, peaked at 72 h, and subsequently declined. Similarly, MiAP2/ERF87 was induced at 6 h but dropped below control levels by 72 h, suggesting that both genes are primarily early-responsive to blue light (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analysis of MiAP2/ERF gene expression in “Guifei” mango peel under blue light treatments, analyzed by means of qPCR. The data values are means ± SDs (n = 3). The * symbol indicates significant differences (p-value < 0.05); ** indicates highly significant differences (p-value < 0.01).

4. Discussion

The AP2/ERF family represents one of the largest TF families in plants and plays crucial roles in various biological processes, including growth and development, secondary metabolism, hormone signaling, and stress responses [43,44]. With the increasing availability of whole-genome sequencing data, this gene family has been characterized in multiple plant species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, rice, grapevine, strawberry, sweet potato, and maize [15,18,45,46,47,48]. In this study, we identified 240 MiAP2/ERF genes from the mango genome and systematically named them MiAP2/ERF1 to MiAP2/ERF240 based on their ascending gene IDs. The AP2/ERF family was initially classified into three subfamilies in Arabidopsis: AP2, ERF, and RAV. Subsequent research revealed that some ERF members do not respond to ethylene, leading to a refined classification system comprising five subfamilies: AP2, ERF, DREB, RAV, and Soloist [49,50]. In the mango MiAP2/ERF family, the AP2 subfamily contains 34 members (14.2% of the total), while the distribution of the other subfamilies is as follows: 126 (52.5%) in ERF, 73 (30.4%) in DREB, 5 (2%) in RAV, and 2 (1%) in Soloist. For comparison, the distribution in Arabidopsis is 12 (12.2%) in AP2, 65 (44.2%) in ERF, 57 (38.8%) in DREB, 6 (4.1%) in RAV, and 1 (1%) in Soloist [15]. Notably, both mango and Arabidopsis exhibit the same descending order of subfamily size: ERF, DREB, AP2, RAV, and Soloist. This indicates that members of the AP2/ERF gene family in both species exhibit strong conservation in the evolution of their core structures and functional frameworks. Furthermore, a comparison with the number of AP2/ERF family members in Arabidopsis reveals that the number in mango is significantly higher, which may be related to the biological characteristics of mango as a perennial woody fruit tree.

Conserved motifs, gene structures, and domains serve as fundamental features for analyzing functional divergence and evolutionary relationships among gene family members. Our analysis revealed similar motif types and distributions within the same subfamily. For instance, motifs 2, 4, 3, and 1 displayed identical distribution patterns across all members of the ERF and DREB subfamilies, indicating high evolutionary conservation. In contrast, distinct variations were observed between different subfamilies, such as the unique presence of motifs 8, 6, 9, and 5 in the AP2 subfamily. Gene structure analysis demonstrated that the AP2 subfamily members possess a greater number of exons and introns compared to other subfamilies, suggesting their potential involvement in more complex biological functions. Members of the Soloist subfamily also exhibit more complex gene structures; however, research on this subfamily remains limited. In Arabidopsis thaliana, one member of this subfamily has been demonstrated to participate in salicylic acid-mediated defense against biotic stress [51]. Substantial functional divergence among subfamilies is closely associated with variations in their conserved domains. Most AP2 subfamily members contain two AP2 domains and are primarily involved in regulating organ development, seed germination, and abiotic stress responses. In Arabidopsis, the AP2 members ANT (AINTEGUMENTA) and AIL6 (AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE6) regulate floral organ development and morphogenesis [52]. The RAV subfamily possesses one AP2 domain and one B3 domain, enabling specific binding to GCC-box and CACCTG sequences [53]. The ERF subfamily members bind to ethylene-responsive GCC-box elements to mediate ethylene signaling [54], while the DREB subfamily primarily interacts with low-temperature-responsive elements (LTREs) and DRE/CRT (CCGAC) elements to participate in abiotic stress responses [55,56]. Gene family evolution and expansion are primarily driven by gene duplication events, including tandem and segmental duplications [57]. Our collinearity analysis identified 190 segmental and 16 tandem duplication pairs in the MiAP2/ERF family, suggesting that these duplication events have played a crucial role in the expansion of this gene family during mango’s evolution.

The biological functions of genes are intrinsically linked to their expression patterns. To investigate the potential regulatory roles of MiAP2/ERF genes in mango growth and development, we analyzed their expression patterns using organ-specific RNA-seq data. The results revealed that the expression profiles can be broadly categorized into three groups. The first group comprises genes with high expression in most organs, suggesting their involvement in fundamental physiological functions. For example, in grapevine, VviERF105 is highly expressed in stems and leaves, where it regulates abiotic-stress-responsive genes to enhance plant tolerance [58]. Similarly, in rice, OsERF83 is expressed in all plant organs and improves drought resistance by regulating drought-related genes [59]. The second group consists of genes specifically highly expressed in certain organs, indicating organ-specific functions. In rice, OsAP2/ERF-40 promotes adventitious root development [60], and in chrysanthemum, CmERF053 regulates root growth and development [61]. In Arabidopsis, BOLITA (an AP2/ERF transcription factor) modulates leaf size [62], while in lettuce, LsAP2 regulates seed shape [63]. The third group includes genes with negligible expression in the six examined organs, implying their potential importance in other organs or under specific conditions not covered in this study. In summary, comparative analysis with other reported species has provided potential functional annotations for the MiAP2/ERF expression patterns observed in this study, and it further corroborates the evolutionary characteristics of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family as both conserved and diverse.

Accumulating evidence indicates that AP2/ERF TFs play regulatory roles in anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants. Our previous studies demonstrated that both postharvest UV-B/white light and blue light treatments induce anthocyanin accumulation in mango peel [39,40]. Research in other plant species has revealed that AP2/ERF TFs regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis through two primary molecular mechanisms. First, they can directly bind to and activate promoters of structural genes in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway. In pear, PbERF22 activates the PbUFGT promoter, thereby promoting anthocyanin accumulation [64]. Conversely, in potato, StRAV1 represses anthocyanin biosynthesis by suppressing the transcription of structural genes StCHS, StANS, and StF3′5′H [65]. Second, AP2/ERF TFs can function through protein–protein interactions with other TFs. In pear, PyERF3 interacts with PyMYB114 and PybHLH3 to form a protein complex that regulates downstream structural genes and influences anthocyanin accumulation [66]. Our RNA-seq analysis of light treatments revealed light-induced expression of several MiAP2/ERF genes, which was further validated through qPCR experiments. Existing research supports the involvement of AP2/ERF genes in light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis. In Arabidopsis, the aterf4/aterf8 double mutant showed a significantly reduced anthocyanin content when compared to a wild type under light conditions, indicating that aterf4 and aterf8 positively regulate light-induced anthocyanin synthesis [67]. In pear, Pp4ERF24 and Pp12ERF96 respond to blue light and interact with PpMYB114 to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis [30]. Furthermore, apple research revealed that light signals are transduced through the MdWRKY1-MdLNC499-MdERF109 pathway, ultimately leading to MdERF109-mediated activation of key anthocyanin biosynthesis genes (CHS, UFGT, bHLH) and promoting anthocyanin accumulation in apple peel [68]. Based on these findings and our expression data, we hypothesize that certain MiAP2/ERF genes may play crucial roles in light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in mango peel. It should be noted that this study has limitations. The possible functions of some genes were inferred through transcriptome and qPCR analyses of gene expression, but direct functional validation of the genes was not performed, and the potential influence of post-transcriptional regulation or tissue heterogeneity was not considered. These issues should be addressed in future studies to fully elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms and modes of action of important AP2/ERF genes.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically identified the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in mango, revealing its key characteristics in terms of evolution, expression, and light response, thereby providing core genetic resources and a theoretical foundation for deciphering the regulatory network of light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in mango. Analyses indicated that this family has undergone significant expansion through gene duplication, with its members being highly evolutionarily conserved and exhibiting distinct tissue-specific expression patterns, suggesting their broad and important roles in mango growth and development. Most crucially, through RNA-seq analysis related to light-induced anthocyanin accumulation and subsequent qPCR validation, we screened a set of candidate MiAP2/ERF genes with potential regulatory roles in this process. Their expression patterns suggest that these genes may have important functions in light-induced anthocyanin accumulation in mango. This study provides valuable genetic resources for a multi-faceted analysis of the molecular mechanism governing anthocyanin biosynthesis in mango and lays a solid foundation for subsequent functional validation and mechanistic studies of these genes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121500/s1, File S1: Physicochemical properties of Mangifera indica L. AP2/ERF proteins; File S2: One-to-one orthologous relationship between mango species; File S3: Segmentally and tandemly duplicated MiAP2/ERF gene pairs; File S4: Sequences of the primers used in this study; File S5: RNA-seq analysis of MiAP2/ERF gene expression in the peel of “Guifei” mango under blue light treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z., M.M.T., Q.D. and M.Q.; methodology, W.Z., M.M.T. and K.Z.; formal analysis, W.Z., M.M.T., Q.D. and M.Q.; data curation, W.Z., M.M.T. and K.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, W.Z., M.M.T., K.Z., Q.D. and M.Q.; writing—review and editing, W.Z., M.M.T., K.Z., Q.D. and M.Q.; funding acquisition, W.Z., Q.D. and M.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 32360736 and 32160678), the National Key Research and Development Plan of China (grant number: 2023YFD2300801), the PhD Scientific Research and Innovation Foundation of The Education Department of Hainan Province Joint Project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City (grant number: HSPHDSRF-2024-12-003), the Open Fund of the Key Laboratory for Quality Regulation of Tropical Horticultural Crops of Hainan Province (grant number: HNZDSYS(2025)-02), and the Collaborative Innovation Center of Nanfan and High-Efficiency Tropical Agriculture, Hainan University (grant number: XTCX2022NYC04).

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within this manuscript and the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ledesma, N.; Campbell, R.J. The Status of Mango Cultivars, Market Perspectives and Mango Cultivar Improvement for the Future. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1244, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wu, H.; Yang, C.; Shi, B.; Zheng, B.; Ma, X.; Zhou, K.; Qian, M. Postharvest Light-Induced Flavonoids Accumulation in Mango (Mangifera indica L.) Peel Is Associated with the up-Regulation of Flavonoids-Related and Light Signal Pathway Genes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1136281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, B.; Wu, H.; Zheng, B.; Qian, M.; Gao, A.; Zhou, K. Analysis of Light-Independent Anthocyanin Accumulation in Mango (Mangifera indica L.). Horticulturae 2021, 7, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakola, L. New Insights into the Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Fruits. Trends Plant Sci. 2013, 18, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araguirang, G.E.; Richter, A.S. Activation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in High Light—What Is the Initial Signal? New Phytol. 2022, 236, 2037–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudry, A.; Heim, M.A.; Dubreucq, B.; Caboche, M.; Weisshaar, B.; Lepiniec, L. TT2, TT8, and TTG1 Synergistically Specify the Expression of BANYULS and Proanthocyanidin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2004, 39, 366–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaart, J.G.; Dubos, C.; Romero De La Fuente, I.; van Houwelingen, A.M.M.L.; de Vos, R.C.H.; Jonker, H.H.; Xu, W.; Routaboul, J.-M.; Lepiniec, L.; Bovy, A.G. Identification and Characterization of MYB-bHLH-WD40 Regulatory Complexes Controlling Proanthocyanidin Biosynthesis in Strawberry (Fragaria × Ananassa) Fruits. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Rao, X.; Li, Y.; Jun, J.H.; Dixon, R.A. Dissecting the Transcriptional Regulation of Proanthocyanidin and Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Soybean (Glycine max). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1429–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Lang, S.; Song, X. ChMYB1-ChbHLH42-ChTTG1 Module Regulates Abscisic Acid-Induced Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Cerasus humilis. Hortic. Plant J. 2024, 10, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, T.; Yuan, L. ERF Gene Clusters: Working Together to Regulate Metabolism. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Wei, S.; Zheng, X.; Tu, P.; Tao, F. APETALA2/Ethylene-Responsive Factors in Higher Plant and Their Roles in Regulation of Plant Stress Response. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 1533–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Tan, S.; Xu, W.; Pan, J.; Yang, F.; Pi, E. ERF Subfamily Transcription Factors and Their Function in Plant Responses to Abiotic Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1042084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Haxim, Y.; Liang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Gao, B.; Zhang, D.; Li, X. Genome-Wide Investigation of AP2/ERF Gene Family in the Desert Legume Eremosparton Songoricum: Identification, Classification, Evolution, and Expression Profiling under Drought Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 885694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jofuku, K.D.; den Boer, B.G.; Van Montagu, M.; Okamuro, J.K. Control of Arabidopsis Flower and Seed Development by the Homeotic Gene APETALA2. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, T.; Suzuki, K.; Fujimura, T.; Shinshi, H. Genome-Wide Analysis of the ERF Gene Family in Arabidopsis and Rice. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Chen, J.-M.; Yao, Q.-H.; Xiong, F.; Sun, C.-C.; Zhou, X.-R.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, A.-S. Discovery and Expression Profile Analysis of AP2/ERF Family Genes from Triticum aestivum. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.; Cai, B.; Peng, R.-H.; Zhu, B.; Jin, X.-F.; Xue, Y.; Gao, F.; Fu, X.-Y.; Tian, Y.-S.; Zhao, W.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of the AP2/ERF Gene Family in Populus trichocarpa. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 371, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licausi, F.; Giorgi, F.M.; Zenoni, S.; Osti, F.; Pezzotti, M.; Perata, P. Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of the AP2/ERF Superfamily in Vitis vinifera. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, C.L.; Rombaldi, C.V.; Dal Cero, J.; Nobile, P.M.; Laurens, F.; Bouzayen, M.; Quecini, V. Genome-Wide Analysis of the AP2/ERF Superfamily in Apple and Transcriptional Evidence of ERF Involvement in Scab Pathogenesis. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 151, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Shen, S.; Yin, X.; Xu, Q.; Sun, C.; Grierson, D.; Ferguson, I.; Chen, K. Isolation, Classification and Transcription Profiles of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Superfamily in Citrus. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 4261–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canher, B.; Lanssens, F.; Zhang, A.; Bisht, A.; Mazumdar, S.; Heyman, J.; Wolf, S.; Melnyk, C.W.; De Veylder, L. The Regeneration Factors ERF114 and ERF115 Regulate Auxin-Mediated Lateral Root Development in Response to Mechanical Cues. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyomarc’h, S.; Boutté, Y.; Laplaze, L. AP2/ERF Transcription Factors Orchestrate Very Long Chain Fatty Acid Biosynthesis during Arabidopsis Lateral Root Development. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambhir, P.; Singh, V.; Parida, A.; Raghuvanshi, U.; Kumar, R.; Sharma, A.K. Ethylene Response Factor ERF.D7 Activates Auxin Response Factor 2 Paralogs to Regulate Tomato Fruit Ripening. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 2775–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Geng, M.; Ma, L.; Yao, G.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H. The H2S-Responsive Transcription Factor ERF.D3 Regulates Tomato Abscisic Acid Metabolism, Leaf Senescence, and Fruit Ripening. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiae560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Cui, Y.; Fan, Z.; Huang, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Ma, H. Ficus carica ERF12 Improves Fruit Firmness at Ripening. Hortic. Plant J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zeng, X.; Wang, X.; Pan, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Hormone Metabolic Profiling and Transcriptome Analysis Reveal Phytohormone Crosstalk and the Role of OfERF017 in the Flowering and Senescence of Sweet Osmanthus. Hortic. Plant J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Song, Q.; Wei, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, M.; Sun, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Luo, K. The AP2/ERF Transcription Factor PtoERF15 Confers Drought Tolerance via JA-Mediated Signaling in Populus. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 1848–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, L.; Li, A.; Guo, J.; Wang, H.; Qi, H.; Li, M.; Yang, P.; Song, S. An AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Confers Chilling Tolerance in Rice. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, X.; Bürger, M.; Wang, Y.; Chory, J. Two Interacting Ethylene Response Factors Regulate Heat Stress Response. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Bai, S.; Zhao, Y.; Qian, M.; Tao, R.; Yin, L.; Gao, L.; Teng, Y. Ethylene Response Factors Pp4ERF24 and Pp12ERF96 Regulate Blue Light-Induced Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in ‘Red Zaosu’ Pear Fruits by Interacting with MYB114. Plant Mol. Biol. 2019, 99, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Premathilake, A.T.; Gao, Y.; Yu, W.; Tao, R.; Teng, Y.; Bai, S. Ethylene-Activated PpERF105 Induces the Expression of the Repressor-Type R2R3-MYB Gene PpMYB140 to Inhibit Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Red Pear Fruit. Plant J. 2021, 105, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, W.; Liao, Y.; Pan, C.; Zhang, M.; Tao, R.; Wei, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. The Ethylene-Responsive Transcription Factor PpERF9 Represses PpRAP2.4 and PpMYB114 via Histone Deacetylation to Inhibit Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Pear. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2271–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; et al. The Strawberry Transcription Factor FaRAV1 Positively Regulates Anthocyanin Accumulation by Activation of FaMYB10 and Anthocyanin Pathway Genes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2267–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, T.; Tomes, S.; Gleave, A.P.; Zhang, H.; Dare, A.P.; Plunkett, B.; Espley, R.V.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, R.; Allan, A.C.; et al. microRNA172 Targets APETALA2 to Regulate Flavonoid Biosynthesis in Apple (Malus domestica). Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhan, X.; Lin, M.; Li, X.; Wang, R.; Sun, L.; Gu, H.; Wei, F.; Fang, J.; et al. AaEIL2 and AaERF059 Are Involved in Fruit Coloration and Ripening by Crossly Regulating Ethylene and Auxin Signal Pathway in Actinidia arguta. Hortic. Plant J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Luo, Y.; Huang, J.; Gao, S.; Zhu, G.; Dang, Z.; Gai, J.; Yang, M.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, H.; et al. The Genome Evolution and Domestication of Tropical Fruit Mango. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Lercher, M.J.; Chen, W.-H.; Hu, S. Evolview v2: An Online Visualization and Management Tool for Customized and Annotated Phylogenetic Trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W236–W241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A Toolkit for Detection and Evolutionary Analysis of Gene Synteny and Collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Zhu, W.; Weng, Z.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhou, K.; Strid, Å.; Qian, M. Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveal the Regulation Mechanism of Postharvest Light-Induced Phenolics Accumulation in Mango Peel. LWT 2024, 213, 117050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Pan, C.; Yang, Q.; Bai, S.; Teng, Y. Blue Light Simultaneously Induces Peel Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and Flesh Carotenoid/Sucrose Biosynthesis in Mango Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 16021–16035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential Gene and Transcript Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; He, Y.; Li, S.; Shi, S.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of AP2/ERF Genes in Eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.M.; Rehman, A.; Razzaq, A.; Parvaiz, A.; Mustafa, G.; Sharif, F.; Mo, H.; Youlu, Y.; Shakeel, A.; Ren, M. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of Erf Gene Family in Cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharoni, A.M.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Satoh, K.; Shimizu, T.; Kondoh, H.; Sasaya, T.; Choi, I.-R.; Omura, T.; Kikuchi, S. Gene Structures, Classification and Expression Models of the AP2/EREBP Transcription Factor Family in Rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 344–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Kong, Y.; Li, H.; Yao, A.; Han, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Han, D. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Profiling of the AP2/ERF Gene Family in Fragaria vesca L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Hao, X.; He, S.; Hao, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, X. Correction to: Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogeny and Expression Analysis of AP2/ERF Transcription Factors Family in Sweet Potato. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; An, L.; Li, F.; Ahmad, W.; Aslam, M.; Ul Haq, M.Z.; Yan, Y.; Ahmad, R.M. Wide-Range Portrayal of AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Family in Maize (Zea mays L.) Development and Stress Responses. Genes 2023, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechmann, J.L.; Heard, J.; Martin, G.; Reuber, L.; Jiang, C.; Keddie, J.; Adam, L.; Pineda, O.; Ratcliffe, O.J.; Samaha, R.R.; et al. Arabidopsis Transcription Factors: Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis among Eukaryotes. Science 2000, 290, 2105–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, Y.; Liu, Q.; Dubouzet, J.G.; Abe, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. DNA-Binding Specificity of the ERF/AP2 Domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, Transcription Factors Involved in Dehydration- and Cold-Inducible Gene Expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 290, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, M.K.; Swain, S.; Gautam, J.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, N.; Bhattacharjee, L.; Nandi, A.K. The Arabidopsis Thaliana At4g13040 Gene, a Unique Member of the AP2/EREBP Family, Is a Positive Regulator for Salicylic Acid Accumulation and Basal Defense against Bacterial Pathogens. J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 171, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizek, B.A.; Bantle, A.T.; Heflin, J.M.; Han, H.; Freese, N.H.; Loraine, A.E. AINTEGUMENTA and AINTEGUMENTA-LIKE6 Directly Regulate Floral Homeotic, Growth, and Vascular Development Genes in Young Arabidopsis Flowers. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5478–5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giraudat, J.; Hauge, B.M.; Valon, C.; Smalle, J.; Parcy, F.; Goodman, H.M. Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 Gene by Positional Cloning. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, D.; Yamasaki, K.; Sarai, A.; Ohme-Takagi, M. Determinants in the Sequence Specific Binding of Two Plant Transcription Factors, CBF1 and NtERF2, to the DRE and GCC Motifs. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 4202–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, E.J.; Gilmour, S.J.; Thomashow, M.F. Arabidopsis thaliana CBF1 Encodes an AP2 Domain-Containing Transcriptional Activator That Binds to the C-Repeat/DRE, a Cis-Acting DNA Regulatory Element That Stimulates Transcription in Response to Low Temperature and Water Deficit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Kasuga, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Abe, H.; Miura, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Two Transcription Factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA Binding Domain Separate Two Cellular Signal Transduction Pathways in Drought- and Low-Temperature-Responsive Gene Expression, Respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1391–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vision, T.J.; Brown, D.G.; Tanksley, S.D. The Origins of Genomic Duplications in Arabidopsis. Science 2000, 290, 2114–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Qu, Z.; Guo, W.; van Nocker, S.; Zhang, C. Grapevine VviERF105 Promotes Tolerance to Abiotic Stress and Is Degraded by the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase VviPUB19. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 201, 105001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.E.; Bang, S.W.; Kim, S.H.; Seo, J.S.; Yoon, H.-B.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.-K. Overexpression of OsERF83, a Vascular Tissue-Specific Transcription Factor Gene, Confers Drought Tolerance in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neogy, A.; Garg, T.; Kumar, A.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Singh, H.; Singh, U.; Singh, Z.; Prasad, K.; Jain, M.; Yadav, S.R. Corrigendum to: Genome-Wide Transcript Profiling Reveals an Auxin-Responsive Transcription Factor, OsAP2/ERF-40, Promoting Rice Adventitious Root Development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Wen, C.; Xi, L.; Lv, S.; Zhao, Q.; Kou, Y.; Ma, N.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, X. The AP2/ERF Transcription Factor CmERF053 of Chrysanthemum Positively Regulates Shoot Branching, Lateral Root, and Drought Tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsch-Martinez, N.; Greco, R.; Becker, J.D.; Dixit, S.; Bergervoet, J.H.W.; Karaba, A.; de Folter, S.; Pereira, A. BOLITA, an Arabidopsis AP2/ERF-like Transcription Factor That Affects Cell Expansion and Proliferation/Differentiation Pathways. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 62, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Wang, S.; Ning, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Qi, M.; Wang, Q. The APETALA2 Transcription Factor LsAP2 Regulates Seed Shape in Lettuce. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2463–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, H.-T.; Zhao, G.-P.; Song, J.-X.; Wang, X.-L.; Yang, C.-Q.; Zhai, R.; Wang, Z.-G.; Ma, F.-W.; Xu, L.-F. Jasmonate and Ethylene-Regulated Ethylene Response Factor 22 Promotes Lanolin-Induced Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in “Zaosu” Pear (Pyrus bretschneideri Rehd.) Fruit. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, D.; Zhao, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, J.; Song, B. StRAV1 Negatively Regulates Anthocyanin Accumulation in Potato. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 295, 110817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Ming, M.; Allan, A.C.; Gu, C.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, R.; Chang, Y.; Qi, K.; Zhang, S.; et al. Map-Based Cloning of the Pear Gene MYB114 Identifies an Interaction with Other Transcription Factors to Coordinately Regulate Fruit Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. Plant J. 2017, 92, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Sato, F. The Function of ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR Genes in the Light-Induced Anthocyanin Production of Arabidopsis thaliana Leaves. Plant Biotechnol. 2018, 35, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yang, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, T.; Song, T.; Yao, Y.; Tian, J. The Long Noncoding RNA MdLNC499 Bridges MdWRKY1 and MdERF109 Function to Regulate Early-Stage Light-Induced Anthocyanin Accumulation in Apple Fruit. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 3309–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).