Abstract

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), an annual herbaceous plant in the Solanaceae family, possesses significant edible and medicinal value. Studies have shown that there are significant differences in the plant chemical constituents and antioxidant activity among different colored peppers, but there have been fewer studies on the relationship between pigment content, plant chemical constituents and antioxidant activity in peppers. Therefore, this study divided twenty pepper accessions of pepper materials into four categories based on color changes and measured the bioactive compounds, pigment content and antioxidant activity of these four types of peppers at different maturity stages and conducted correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA). The results showed that yellow pepper cultivars had higher levels of vitamin C (Vc), and Class IV (purple-to-red transitioning pepper cultivars) had higher total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and anthocyanin content in the early fruit stage. Correlation analysis showed that Class IV (purple-to-red transitioning pepper cultivars) had higher levels of bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity. The antioxidant content in immature fruits was high, but decreased as the fruits matured. This study focuses on pepper-derived bioactive compounds and their antioxidant activity, providing a scientific basis for developing natural antioxidant products, expanding pepper resource utilization, and guiding pepper variety selection and cultivation management.

1. Introduction

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) stands as one of the most widely utilized crops with dual roles as a vegetable and a spice [1]. Although the fruit possesses multiple inherent traits that influence consumer acceptance, it remains in high global demand [2]. Among the key traits that determine the quality of pepper fruits, fruit color stands out as the most critical, as it is closely linked to pigments associated with flavor characteristics, nutritional value, and health-beneficial properties. The coloration of immature pepper fruits ranges from ivory to various shades of green, a number of other pepper cultivars may even exhibit different purple tones, whereas the mature pepper fruit varies from white to yellow, orange and red, or even brown. The color of the fruit varies because of the concentration of pigments, mainly chlorophyll, carotenoids and anthocyanins [3]. Fruit color ranks as a key quality attribute, as pigments not only modulate fruit hue but also confer diverse functional properties—including defense against abiotic stresses (e.g., ultraviolet radiation, intense light, low temperatures) and pathogenic organisms [4]. More importantly, these bioactive compounds play a vital role in shaping the flavor profiles and nutraceutical value of pepper fruits, as the majority of them possess significant antioxidant activity. Furthermore, this pepper variety holds considerable nutritional significance, as it is enriched with pigments, vitamins, and phenolic compounds—bioactive substances extensively linked to a range of biological activities, including antimicrobial, antiseptic, anticancer, counterirritant, cardioprotective, appetite-stimulating, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory effects [5,6,7].

Phytochemicals serve as the primary contributors to the organoleptic characteristics and bioactive properties of pepper fruits. The content of phytochemicals is one of the important indicators to evaluate fruit quality, including carbohydrates, vitamins, phenols and so on. At the same time, the organic acids, pigments and aromatic substances can be endowed with color, fragrance and good sensory properties. Vitamin C (Vc) functions as a coenzyme for enzymes implicated in human metabolic processes and is present at high levels in mature pepper fruits [8]. Fruits are integral components of our diet and potential sources of essential nutrients [9]. With the increasing emphasis on a healthy diet, there is a growing interest in functional foods rich in flavonoids and anthocyanins, which has also boosted the commercial value of purple fruits and vegetables [9]. The majority of functional attributes exhibited by pepper cultivars—including dietary benefits and pharmacological activities—are primarily ascribed to the antioxidant potential of vitamin C (Vc), total phenols, and flavonoids [10]. Additionally, pepper fruits are significant sources of nutraceutical compounds such as carotenoids, flavonoids, and ascorbic acid, which promote human health [11].

Peppers are used in almost all the dishes in China, and people eat them at every harvesting maturity stage (from green to red color). Since peppers are consumed at any stage from green to red, it is crucial to ascertain the presence of health-promoting secondary metabolite constituents, such as phenolic compounds, alkaloids, and terpenoid pigment (particularly flavonoids, which have been demonstrated to have positive effects on human health and disease prevention) [12,13]. Although efforts have been made to clarify the content of harvesting maturity stage in order to assess the antioxidant activities and physicochemical characteristics of pepper fruits with red, orange, yellow, green, and purple fruit colors, there is a dearth of knowledge regarding other advantageous substances at each level of maturity [14]. As the pepper fruit matures, its phytochemical composition changes, so in order to determine the best quality of the pepper fruit at the time of harvesting, the maturity of the harvest should be considered. Calculating days after flowering (DAF) is one of the most common ways to determine fruit ripeness. Therefore, it is also important to use chemical methods to determine harvest maturity [15]. Although there has been an attempt to elucidate the content of metabolites at each harvesting maturity stage [16], information on other beneficial compounds at fruit color is lacking. Several studies have been carried out to evaluate the variation degree between anthocyanins and carotenoids in purple and yellow pepper fruits. However, the available findings provide limited information regarding how phytochemicals influence the pigment composition of peppers at different maturity stages, as well as the corresponding impacts on antioxidant capacity [17]. The maturity of the pepper fruits is a key factor in obtaining the desirable quality capable of providing consumers with a high content of vitamins and antioxidants. Thus, these phytochemicals have potential health benefits for the human diet. Numerous studies have confirmed that peppers possess substantial nutritional value, prominent health-promoting effects, and notable medicinal properties—traits that endow them with excellent quality and garner significant interest from both consumers and producers [18].

The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of maturity stage on the secondary metabolites and antioxidant activities of differently colored peppers. The core objective of the present study was to determine the pigment contents, nutrients and antioxidant capacity of four types of pepper fruits with different colors at different maturity stages, determine the key phytochemicals and pigments affecting pepper fruits through PCA, and analyze the correlation degree between pepper fruit color and maturation stage through correlation analysis. This study provides a comprehensive perspective on the phytochemical characteristics of pepper fruit color and ripening stage. In addition, it may provide a basis for further research to evaluate potential applications that can be used in medicinal plants, functional foods, nutriceuticals, or the production of natural medicines that improve health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

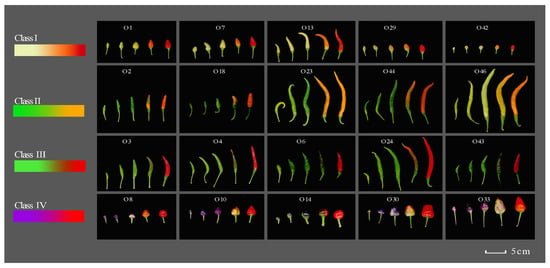

The cultivars of 20 peppers accessions were obtained from the Shanxi Agricultural University Horticulture Institute pepper research group. All peppers were cultivated at the Horticultural practice base of Shanxi Agricultural University (37°42′ N, 112°58′ E), which has a warm temperate continental climate with four distinct seasons, significant temperature variations, multi-year average precipitation of 466.3 mm (concentrated in June–August), annual evaporation capacity of 1765.9 mm, annual sunshine duration of 2500–2600 h, and prevailing southwest and northwest winds year-round. Pepper seeds were planted in the greenhouse in March 2023, transplanted to a test field when the plants reached the eight-leaf stage, and the daily management practices were conducted until harvesting. Peppers were divided into four categories (Figure 1, Table S1). The stages of fruit ripening were defined with reference to the method described by Deepa et al. [19]. Pepper fruits were collected at five distinct developmental stages, specifically 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 days after anthesis (DAA). The fruit stalks and placenta were removed. The fresh fruit were stored at −80 °C for further analysis.

Figure 1.

Four groups classified with different fruit color and fruit maturity of peppers. Note: The order of maturation is from left to right: 10 days, 20 days, 30 days, 40 days and 50 days after flowering.

2.2. Fruit Color Trait Determination (L*a*b*)

Twenty pepper cultivars were divided into four categories according to L*, a*, b* values and pigment levels in different periods. Three pepper plants with similar growth vigor were selected, and six fruits were harvested from each plant (uniform in size and consistent in color). A colorimeter was used to measure the peel lightness (L*), red–green axis (a*), and yellow–blue axis (b*) values of pepper fruits at different developmental stages. Measurements were taken at three points (upper, middle, and lower parts) in the central region of each fruit, and the average value was used as the final color parameter. The three color parameters were defined as follows: L* represents lightness, ranging from 0 (absolute black) to 100 (absolute white); a* denotes the red–green axis, with positive values indicating red tendency and negative values indicating green tendency; b* denotes the yellow–blue axis, with positive values indicating yellow tendency and negative values indicating blue tendency. Each fruit sample was measured at three equidistant points on the equatorial plane, and the average value was taken as the final color parameter of the sample.

2.3. Soluble Sugar Content (SS)

The soluble sugar content was extracted from fruit samples by hot Ethanol (EtOH) extraction method with 3 replicates [20]. Two hundred milligrams of ground pepper fruit tissue was placed into a test tube, followed by the addition of 3 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol; the mixture was homogenized via shaking. Subsequently, the sample was incubated at 80 °C for 30 min with continuous shaking, and thereafter centrifuged at 10,000 revolutions per minute for 10 min. Repeat the above steps 2 times for the residue. After 10-fold dilution of the total solution to be tested, 2 mL was taken into 5 mL of freshly prepared EtOH reagent (0.2% EtOH in concentrated H2SO4) and was pipetted into a test tube and chilled in ice water. The extract was mixed with the enthrone reagent, the tube heated in boiling water for 15 min, and rapidly cooled. The absorbance was measured at 630 nm [21]. Soluble sugar content was calculated as mg glucose equivalents (GLU)/g fresh weight (Fw) (y = 0.0026x − 0.0125, R2 = 0.9914).

2.4. Soluble Protein Content (SP)

The soluble protein content was extracted by the Coomassie Brillant Blue G-250 Bradford Method [22]. Pipette 10 mL of distilled water with 150 mg of ground pepper fruit material in a test tube (repeat twice for each sample), centrifuge for 10 min at 5000 r/min. To test the 1 mL solution, 5 mL of Coomassie Brilliant Blue reagent was added, shaken well, and left for 5 min until the reaction is complete. The colorimetry was used to measure the absorbance at 595 nm, and the results were expressed as mg bovine serum albumin equivalent (BSA)/g fresh weight (Fw) (y = 0.0067x + 0.0986, R2 = 0.9939).

2.5. Vitamin C Content (Vc)

Vc determination was conducted using ammonium molybdate staining method [23]. Weigh 200 mg of pepper fruit samples, add 2.5 mL oxalic acid EDTA solution and grind into a homogenate. Take the homogenate by 3000 r/min centrifugation for 10 min, pipette 1 mL of supernatant add 0.5 mL metaphosphate–acetic acid solution, 1.0 mL 5% (volume fraction) H2SO4, 2.0 mL 5% ammonium molybdate solution; the tube was heated in hot water (30 °C) for 15 min, and the absorbance was read at 760 nm [24]. The results were expressed as mg ascorbic acid equivalent (ASC)/100 g fresh weight (Fw) (y = 0.0218x − 0.0434, R2 = 0.9981).

2.6. Total Polyphenolic Content (TPC)

Total polyphenolic content of pepper extracts was determined by spectrophotometric method [25]. A total of 4 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol was mixed by shaking with 500 mg of ground pepper fruit material in a test tube, then ultrasonically extracted (40 °C) for 30 min, and the above steps were repeated 2 times for the residue constant volume to be transferred into a 10 mL tube. Accordingly, 1.0 mL of the plant extract was pipetted into a test tube, followed by the addition of 0.5 mL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Subsequently, 2 mL of 10% (w/v) sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) solution was incorporated into the mixture. The flasks were stored in the dark. After 1 h, it was measured at 760 nm using an Ultraviolet–visible scanning spectrometer (Shimadzu, Model UV-2700i, Kyoto, Japan) [26]. Results are expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/g fresh weight (Fw) (y = 0.0004x + 0.4168, R2 = 0.9915).

2.7. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The aluminum chloride colorimetric method established by Mammen et al. was employed for the quantification of total flavonoid content (TFC) in pepper samples [27]. Consistent with the TPC determination protocol, 1 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.25 mL of 5% aluminum chloride (AlCl3) solution. After thorough vortexing and a 6 min incubation at room temperature, 0.25 mL of 10% aluminum nitrate (Al(NO3)3) was added to the mixture, which was then re-vortexed and incubated for an additional 6 min. Finally, 1.5 mL of 4% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution was incorporated into the reaction system. Shake the mixture thoroughly, allow it to stand for 15 min, and then measure the absorbance at 510 nm with a spectrophotometer. Results are expressed as mg rutin (98%, Solarbio, Beijing, China) equivalent (RU)/g fresh weight (F.w) (y = 0.0018x + 0.0211, R2 = 0.9968).

2.8. Pigment Content in Fruits

The chlorophyll pigment content was quantified in accordance with the experimental protocol outlined previously. Five fruits were selected, and their flesh and peel portions were cut and weighed to 0.5 g per sample, with three replicates set for the study. Subsequently, the pepper samples were subjected to extraction with 95% ethanol (EtOH) in an ultrasonic bath, and the resulting mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 revolutions per minute (r/min) for a duration of 10 min [28].

Ca = 13.95 × A665 − 6.88 × A649

Cb = 24.96 × A649 − 7.32 × A665

Cchlorophyll = Ca + Cb

Ccarotenoid = (1000 × A470 − 2.05 × Ca − 114.8 × Cb)/245

Anthocyanin were determined using the pH method. The pepper pulp was ultrasonically extracted with methanol (1% HCl), and the supernatant was collected for the absorbance and measured at 530 nm and 700 nm, respectively, with three biological replicates [29].

Canthocyanin = [(A530 − A700) pH1 − (A530 − A700) pH4.5] × Mw × DF × V × 100/(e L Wt)

2.9. Antioxidant Activity

Radical scavenging assay by 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and ferric-reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP) were used to determine the antioxidant activity of plant extracts.

The ABTS Assay: Minor modifications were made to the method originally proposed by Mareček [30]. Weigh 0.1 g of pepper fruit, grind it in 10 mL of 95% ethanol, and dilute the resulting slurry to a concentration of 1 mg/mL to serve as the test solution. An aqueous solution of ABTS (7.4 mM, 0.2 mL) was first prepared and mixed with 0.2 mL of 0.26 M potassium persulfate (K2S2O8) solution in the dark for 12 h. The resulting mixture was then diluted with pH 7.4 phosphate buffer until the absorbance was at 734 nm (A734 reached 0.7 ± 0.02, yielding the ABTS radical cation solution). For blank measurement, 0.8 mL of freshly prepared ABTS solution was mixed with 0.2 mL of 95% (v/v) ethanol, and the absorbance (A_blank) was recorded at 734 nm. For sample analysis, 0.8 mL of ABTS solution was combined with 0.2 mL of the test sample solution; after thorough mixing, the absorbance (A_sample) was measured at the same wavelength. All aforementioned procedures were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Ascorbic acid (ACS) content per gram of sample was substituted for the sample itself, and the results were computed based on the standard curve, expressed as clearance rate (yABTS = −42.61x + 0.029, R2 = 0.9935).

The DPPH method: After slight modification of Mareček’s reference method [30], the same sample preparation procedure as the ABTS method was adopted. Specifically, 1.0 mg of DPPH was weighed, and its A value was measured three times at a wavelength of 519 nm. The clearance rate was used to present the experimental results, which were computed via the calibration curve (ACS) following the equation (yDPPH = −20.559x + 0.3, R2 = 0.9942).

The FRAP method: A protocol slightly modified from Gohari [31] was utilized. Initially, three solutions were prepared: 0.3 mM acetic acid buffer (pH = 7.0), 25 mL of 10 mM TPTZ reagent, and 50 mL of 20 mM FeCl3 solution. These three components were mixed at a 10:1:1 volume ratio to generate the FRAP working solution, which was freshly prepared for immediate use. Next, 0.1 g of pepper sample was weighed and homogenized with 2.5 mL of deionized water. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 1200× g and 4 °C for 10 min, after which 0.1 mL of the supernatant was aliquoted and mixed with 2.4 mL of the FRAP working solution. After incubation in a 37 °C water bath for 10 min, the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 593 nm. For calibration curve establishment, the sample was substituted with FeSO4 standard solutions at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mol/L, yielding the regression equation (yFRAP = 140x − 5.94, R2 = 0.9975).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The experiments were conducted in triplicate. We subjected the obtained data to multivariate statistical analysis, including analysis of variance, one-way ANOVA, Pearson correlation, PCA, analysis using SPSS 25.0 (Statistical Analysis software, version 25, IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), GraPhpad Prism 9.5 (Data processing and graphics software, version 9.5, GraphPad Software Co., San Diego, CA, USA) and Origin 2021 (Graphing and data analysis software, version 21, Origin Lab Co., Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Cluster Analysis of Fruit Color in Different Peppers

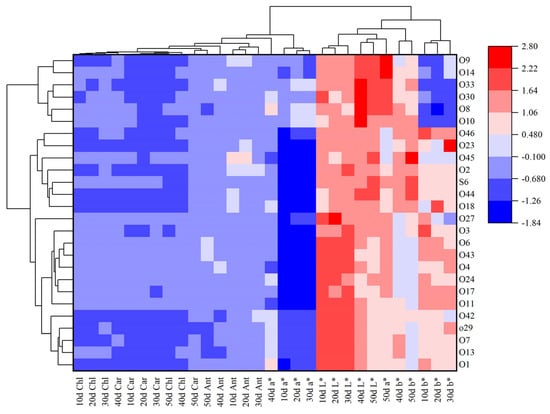

Using the L*, a*, b* values of pepper fruit color and the content of fruit peel pigments as the basis for fruit color classification, the Ward clustering algorithm was applied, with correlation and Euclidean distance as the clustering distances for row and column clustering analysis, respectively (Figure 2). For the measured L*, a*, b* values and pigment content of pepper fruit peel, they are generally clustered into two major categories. The first category includes all periods of chlorophyll, carotenoid and anthocyanin content indicators, as well as the a* color indicator from 10 to 40 days after flowering; the second category includes all periods of L* and b* color indicators, as well as the a* color indicator 50 days after flowering. It suggests that the L* and b* values are mainly influenced by the content of chlorophyll and carotenoids, while the a* value is primarily related to the content of anthocyanins. Based on the above analysis results, the 20 chili materials were classified into four fruit color types (Figure 1). The first category includes materials that change from yellow–green or yellow–white to bright red (O1, O7, O13, O29 and O42), the second category includes materials that change from green to orange–yellow (O2, O18, O23, O44 and O46), the third category includes materials that change from green to bright red or dark red (O3, O4, O6, O24 and O43) and the fourth category includes materials that change from purple to bright red or dark red (O8, O10, O11, O30 and O33).

Figure 2.

Cluster analysis chart of L*, a*, b* values and pigment content of pepper fruits in different periods. Note: This chart integrates three color parameters (L*, a*, b*) and three key pigment contents (chlorophyll, carotenoid, anthocyanidin) of 20 pepper cultivars across five developmental stages (10–50 days after flowering), with the horizontal axis representing the Euclidean distance coefficient (smaller values indicate higher similarity), the vertical axis marking sample numbers, and branches of different colors corresponding to four classes, each with distinct color transition trends and pigment characteristics.

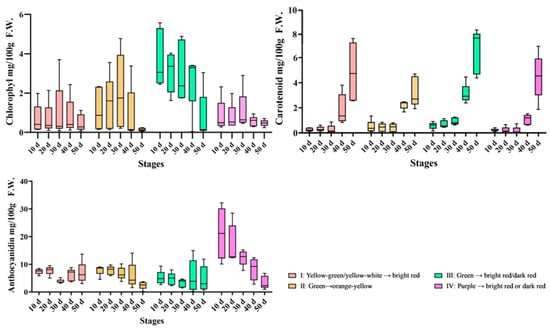

3.2. The Pigment Content of Different Colored Peppers at Different Stages

Many studies have reported an association between pepper fruit color and pigment content, while our study demonstrates that pigment content varies with both fruit color and maturity stages (Figure 3). Overall, the chlorophyll content of peppers showed a phased increase during the young fruit stage, followed by a gradual decrease. Taking Class II (green to orange) as an example, the chlorophyll content continuously increased from 2.5 mg/100 g F.W. at 10 days to 3.0 mg/100 g F.W. at 30 days (an increase of 20.0%), and then significantly decreased to 2.0 mg/100 g F.W. at 50 days (a decrease of 33.3% compared to 30 days). In Class III (green to red), the chlorophyll content reached a peak of 5.5 mg/100 g F.W. at 20 days (an infinite increase compared to 10 days), followed by a rapid decline, with only 1.8 mg/100 g F.W. at 50 days (a decrease of 67.3% compared to 20 days). This indicates that pepper chlorophyll gradually accumulates during the young fruit stage (10–30 days) and enters the degradation stage after 30 days.

Figure 3.

Variations in pigment content with pepper fruit color and maturity change.

Carotenoids showed a continuous accumulation pattern throughout the growth cycle, with a significant increase after 30 days. The carotenoid content in Class I gradually increased from 0.2 mg/100 g F.W. at 10 days to 0.5 mg/100 g F.W. at 30 days, and further increased to 7.5 mg/100 g F.W. at 50 days. In Class III, it increased from 0.5 mg/100 g F.W. at 10 days to 1.0 mg/100 g F.W. at 30 days (doubled), and reached 8.0 mg/100 g F.W. at 50 days. It can be seen that carotenoid content had doubled by 30 days and entered a rapid accumulation period in the late maturity stage (40–50 days).

The anthocyanin content of fruits in Class IV (purple to red) reached a peak in the young fruit stage (20 days) and then gradually decreased. The anthocyanin content of this class reached 30.0 mg/100 g F.W. at 20 days, then continued to decrease, with 25.0 mg/100 g F.W. at 30 days (a decrease of 16.7% compared to 20 days) and 10.0 mg/100 g F.W. at 50 days (a decrease of 66.7% compared to 20 days). This trend indicates that anthocyanin synthesis in peppers in Class IV is mainly concentrated in the young fruit stage, with degradation predominating in the late maturity stage.

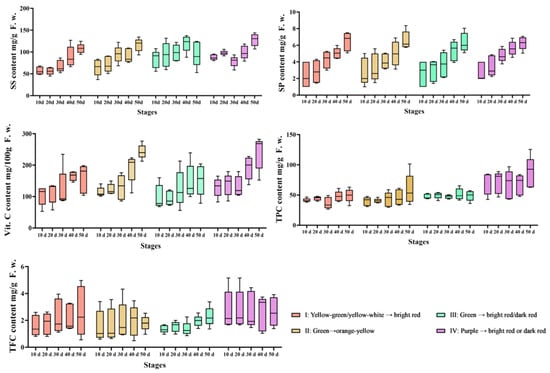

3.3. The Chemical Composition of Four Different Colored Peppers at Different Stages

To study the influence on phytochemicals of different fruit color and maturity of peppers, the distributions of SS, SP, Vc, TPC and TFC in the 20 germplasms are presented in Figure 4. Notable significant differences were observed in the contents of all phytochemicals across the four Capsicum groups. Overall, the SS values of chili fruits gradually increased in all five stages, indicating that the SS gradually accumulated as the fruits matured. The Vc content gradually increased with fruit development. The Vc content of class II (green to orange) fruits was as high as 242.96 mg/100 g in mature fruits, which was higher than other cultivar and the yellow colored fruit. The highest contents of TPC (87.43 mg/g) and TFC (2.77 mg/g) were observed in class IV. Among the five phytochemical parameters, the TPC and TFC were most varied in Class IV (purple-to-red transitioning pepper cultivars), and the Vc contents were highest in class II pepper material with mature, yellow colored fruit. Interestingly, the average values of TPC and TFC all decreased in the order of Class IV (purple to red) > Class II (green to orange) > Class I > Class III (green to red), whereas the average content of SP and Vc increased in the order of Class IV (purple to red) < Class I < Class III (green to red) < Class II (green to orange).

Figure 4.

Variations in phytochemicals with pepper fruit color and maturity change.

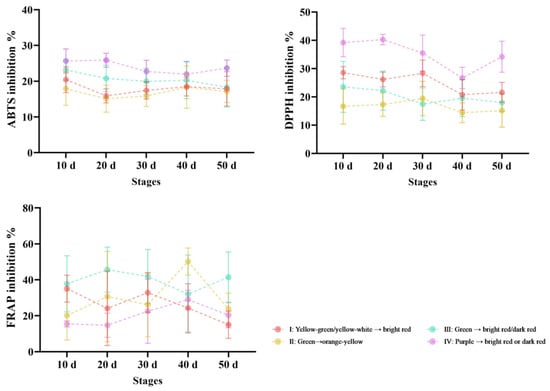

3.4. The Antioxidant Activity of Different Colored Peppers at Different Stages

Three widely applied antioxidant assays, namely DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS, were adopted to evaluate the antioxidant activity of pepper samples (Figure 5). At the early fruiting stage, most materials exhibited high antioxidant capacity, which was followed by a decrease at the breaker stages and a modest elevation when reaching biological ripeness. For most Capsicum materials, antioxidant capacity was relatively higher during the young fruit stage, followed by a decrease at the color transition stage, and a slight elevation when reaching the mature stage. The ABTS, DPPH and FRAP ranged from 10.05% to 45.57%, 6.27% to 47.85% and 3.65% to 68.90%, respectively. Among the four-category fruit color classification, fruits belonging to Class IV exhibited stronger DPPH and ABTS free radical scavenging capacities compared with the other three color classes, among which the highest ABTS scavenging rate was 54.9% at 10d, and the highest DPPH scavenging rate was 47.85% at 50 d. Overall, the antioxidant activity of purple fruit is stronger than that of other colored pepper materials.

Figure 5.

Variations in antioxidant activity with pepper fruit color and maturity change.

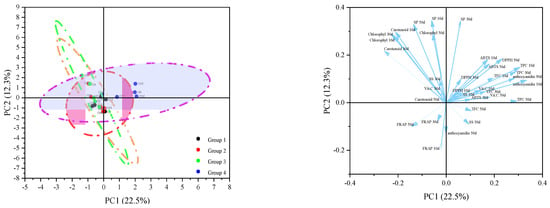

3.5. Principal Component Analysis of Chemical Composition, Pigments and Antioxidants

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the dataset covering 20 pepper germplasms, with the analyzed parameters including phytochemical contents and antioxidant activity indices measured at 10, 30, and 50 days post-anthesis (DAA). Ten principal components (PCs) with eigenvalues exceeding 1 accounted for 87.33% of the total variance among the tested germplasms (Figure 6). In the analysis of phytochemical variables and antioxidant activity, the first principal component (PC1) accounted for 22.5% of the total variance, supported by an eigenvalue of 7.43. The second principal component (PC2) contributed 12.30% to the total variance with a corresponding eigenvalue of 4.06, while the third (PC3) and fourth (PC4) components explained 9.56% and 9.53% of the total variance, respectively. Consequently, PC1 and PC2 were selected to generate score and loading plots, which were utilized to analyze the distribution characteristics of pepper germplasm resources and the associations between their phytochemical contents and antioxidant activities. Anthocyanidin 10d (33.57%), TPC 10d (30.74%), TPC 50d (29.44%), TPC 30d (29.02%), anthocyanidin 30d (28.52%), TFC 10d (19.83%), Vc 50d (18.23%) made the largest contributions to the variance along PC1. Furthermore, we also observed distinct aggregation in Class I, Class II and Class III with chlorophyll and carotenoids. The score and loading diagrams depict the distribution patterns of pepper germplasm resources, which were classified according to fruit color and maturity stage; the majority of Class I, Class II, and Class III accessions were located on the negative side of PC1, while Class IV (purple to red) accessions were positioned on the positive side.

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis biplot for the phytochemical contents and antioxidants of peppers.

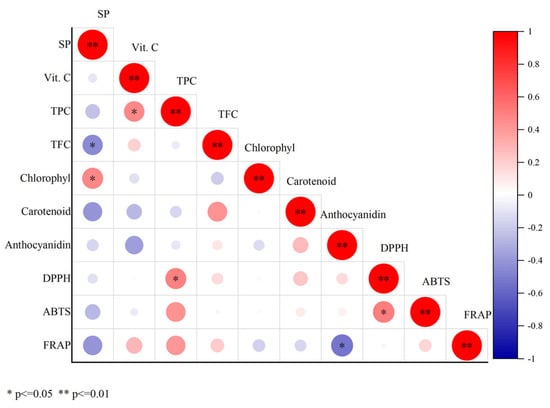

3.6. Correlation Analysis Between Phytochemicals, Pigments and Antioxidants

To elucidate the relationship between nutrient content, pigment levels, and antioxidant capacity in mature chili peppers (50 days post-flowering), a correlation analysis was conducted (Figure 7). The results indicated that soluble protein in peppers was positively correlated with chlorophyll content (r = 0.48) and negatively correlated with flavonoids (r = −0.45), total phenolic content was positively correlated with Vc content (r = 0.46) and DPPH (r = 0.49), ABTS was positively correlated with DPPH (r = 0.51), while FRAP was negatively correlated with anthocyanins (r = −0.52).

Figure 7.

Correlation analysis chart of nutritional components, pigments, and antioxidant capacity of peppers. Note: “*” means significant (* p ≤ 0.05), “**” means extremely significant (** p ≤ 0.01).

4. Discussion

As a critical sensory characteristic of pepper fruits, color is intrinsically linked to the accumulation of phytochemicals (e.g., carotenoids, anthocyanins) and the variation in antioxidant properties among different classes. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the metabolic profiles associated with pepper fruit color are closely linked to fruit pigments, and these bioactive components exert a significant influence on the biological properties of the fruits [32]. Notably, pepper genotypes displaying diverse fruit coloration exhibit a vivid surface appearance, which in turn contributes to variations in phytochemical compositions and antioxidant capacities of the fruits [33]. The main component of pigmented substances in the pericarp decide the fruit color, and their content is essential for the formation of fruit phenotypes [34]. This may be attributed to the purple color of the fruits, which has a high accumulation of phenolic compounds and flavonoids. The scavenging capacity of fruit extract is influenced by the substitution of the hydroxyl group in the aromatic rings of phenols, which contributes to the ability of the metabolites to donate hydrogen [35]. The presence of several metabolites with an aromatic ring in their structure, like TFC and TPC, which contribute to the high scavenging activity values, may account for the purple chili’s scavenging capacity. Anthocyanins require phenolic compounds, which also explains the higher clearance rate of Class IV (purple–red) fruits than other classes (Figure 4). Similar results were reported in previous studies [17,36]. As a result, the findings indicate that the phytochemical parameter values of investigated peppers are in accordance with the data from previous studies [37,38]. Accordingly, researching the correlations between fruit color, phytochemical contents and antioxidant activities may therefore be very helpful in choosing pepper cultivars that are both high quality and have medicinal values.

In this study, all pepper extracts contain bioactive compounds with variation in bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity; the antioxidant activity of chili fruits was high at the young fruit stage (Figure 5). This parameter could serve as a discriminatory criterion for differentiating pepper fruits of distinct color types across various fruit ripening stages [39]. In class IV (purple to red) fruits, the SS was higher in the infant stage than at 30 d (Figure 4), because of the difference expressed by the purple color of the fruit, which indicated the SS substance may be involved in anthocyanin synthesis. Elevated levels of total flavonoid content (TFC), other phytochemical constituents, and antioxidant capacities collectively indicate that the purple fruits possess favorable quality attributes and potential health-promoting properties [40]. There were targeted and untargeted metabolites (including the capsaicin, TPC and TFC levels) and antioxidant properties in super-hot chili peppers at different maturity stages [41]. Anthocyanin accumulation in berries during the early ripening stages may contribute to enhanced antioxidant capacity, attributed to the increased content of polyphenolic compounds. For the SP, the trend of values was more or less the same in all five stages, with a gradual increase (Figure 4), suggesting that the SP index may not be related to changes in fruit color. The antioxidant capacity of the TPC in pepper was higher than that of Vc, and the antioxidant capacity of immature fruit was higher than that of mature fruit, and the antioxidant capacity gradually decreased with the maturity of fruit (Figure 5). The Vc is an ascorbate chemical which can react with physiologically important radicals and oxidants and acts as a reducing agent and antioxidant. It serves as a co-substrate for multiple hydroxylases and oxidoreductases, maintaining the active center metal ions in a reduced state [42,43]. In conclusion, the TPC and TFC both complement each other and together they can act on antioxidant capacity. While these results have made a substantial contribution to the field of chili research, majority of these studies focused on pericarp extracts and only a small number of genotypes were employed. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation focusing on diverse pepper genotypes is necessary to achieve an in-depth understanding of how pericarp color interacts to influence the phytochemical contents and antioxidant properties of the fruits.

A majority of the phenotypic traits exhibited significant differences among distinct Capsicum species [44,45]. This study provided information concerning physicochemical properties (SS, SP, Vc, TFC, TPC), pigment substances (chlorophyll, carotenoids, anthocyanins), antioxidant capacity (FRAP, ABTS and DPPH) and variations in biologically active compounds, antioxidant activity and physicochemical properties in peppers (Table S1). A majority of the phenotypic traits exhibited significant differences among distinct Capsicum species [17]. Consumers’ primary interest lies in food products that are visually appealing, offer protective effects against diverse diseases, and are enriched with bioactive compounds recognized for their beneficial properties [46]. Epidemiological studies showed that flavonoids activate the antioxidants, which include anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anti-angiogenic, anti-viral, and also anti-malarial properties [47].

The results indicated the influence on the biochemical and physicochemical compositions of fruit color and maturity of peppers that was similar to previous findings [8,48]. Class IV (purple-to-red transitioning pepper cultivars) had higher antioxidant activity than other cultivars, and immature peppers had higher antioxidant activity than mature fruit among pepper fruits of different colors and stages (Figure 5). The fruit of Lonicera caerulea has been shown to exhibit changes in primary and secondary metabolites as it ripens. These changes suggest that fruit development and taste may be influenced by changes in organic acid and soluble sugar contents, and that fruit color and antioxidant activity may be closely correlated with changes in phenolic acid, anthocyanin, and flavonoid contents [49]. Consistent with findings from previous studies, purple fruit genotypes demonstrated higher levels of total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) compared to genotypes with other fruit colors, whereas orange fruit genotypes showed elevated ascorbic acid (Vc) levels [36]. Here, multivariate analysis performed on the phytochemical contents and antioxidant properties of the fruit of 20 pepper genotypes revealed that pericarp color could affect the phytochemical contents and antioxidant properties of the fruit. The study revealed that the Class IV (purple to red) extracts exhibited stronger antioxidant activity than other cultivars. These differences showed that antioxidant properties vary with the accumulation and degradation of phytochemicals in the plant due to different maturity stages. These compounds—including total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and anthocyanins from Class IV pepper cultivars (purple-to-red transitioning types) as well as carotenoids from mature pepper fruits—can serve as discriminative indicators for differentiating pepper germplasm resources based on their food usage categories. The results will be very useful for nutritional studies on phytochemicals and antioxidant-activity-rich food and fruit authenticity research with pepper.

The temporal variations in the studied variables (e.g., phytochemical contents, antioxidant activity, soluble sugar (SS), soluble protein (SP)) stem from the physiological maturation and biochemical metabolism of pepper fruits: during ripening, chlorophyll degrades while carotenoids or anthocyanins accumulate (thus driving fruit color changes); SS fuels anthocyanin biosynthesis in purple–red peppers, peaking in the early stage before declining; SP increases steadily with fruit development; and antioxidant activity decreases as phenolics and flavonoids degrade, with total phenolic content (TPC) contributing more significantly to antioxidant capacity than vitamin C (Vc). These variations are theoretically regulated by growth regulators (e.g., ethylene promotes ripening-related pigment transformations, while cytokinins and gibberellins preserve phytochemical levels in immature fruits) and key biomolecules (e.g., enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway modulate phenolics and flavonoids, and capsaicin interacts with antioxidant compounds). Although no explicit stress treatment was applied in this study, developmental stress (e.g., ripening-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS)) triggers the synthesis of phenolic and anthocyanin antioxidants, and potential environmental stress (such as temperature or light fluctuations) or intrinsic genotypic stress adaptation (e.g., the robust stress responses of purple–red cultivars) may further enhance the accumulation of bioactive compounds.

5. Conclusions

The nutrients and antioxidant capacity of differently colored peppers were analyzed in this experiment. The results suggest that certain sensory characteristics of the fruit—with mature fruit color as a key example—can serve as indicators of the phytochemical composition in pepper fruits. In particular, pepper species with yellow colored fruits had higher levels of Vc. The pepper species of fruits that were purple had higher TPC, TFC and anthocyanin contents at the young fruit stage. The antioxidant content of the immature fruit was high, but it dropped as the fruit ripened. The correlation of phytochemicals and antioxidant activity was summarized by PCA, validating the different performances in the four categories of pepper germplasm. The correlation analysis verified the correlation between chemical substances and antioxidant activity. This study fills the gap in understanding how fruit color and maturity jointly shape pepper phytochemicals, identifying clear trait–nutrient links. The PCA and correlation data offer direct, actionable insights for breeding, enabling rapid pre-selection of high-antioxidant, nutrient-rich genotypes based on observable fruit traits, with no complex testing required.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121481/s1, Figure S1: Correlation analysis of fruit phytochemicals with pigment composition of pepper fruit color; Figure S2: Pearson’s correlation coefficients of phytochemical contents and antioxidant; Table S1: Impacts of different periods and color-based groups on pepper ABTS activity; Table S2: Impacts of different periods and color-based groups on pepper DPPH activity; Table S3: Impacts of different periods and color-based groups on pepper FRAP activity; Table S4: Variations in chlorophyll content across different pepper fruit colors and maturity stages; Table S5: Variations in carotenoid content across different pepper fruit colors and maturity stages; Table S6: Variations in anthocyanin content across different pepper fruit colors and maturity stages; Table S7: Variations in soluble sugar (SS) content with pepper fruit color and maturity; Table S8: Variations in soluble protein (SP) content with pepper fruit color and maturity; Table S9: Variations in vitamin C (Vc) content with pepper fruit color and maturity; Table S10: Variations in total phenolic content (TPC) with pepper fruit color and maturity; Table S11: Variations in total flavonoid content (TFC) with pepper fruit color and maturity.

Author Contributions

J.W.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. J.H.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft. R.Z.: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. N.L.: Investigation, Methodology, Resources. S.Z.: Investigation, Resources. J.L.: Investigation. S.S.: Funding acquisition, Project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Applied Basic Research Project of Shanxi Province [Grant No. 202503021211171], the Key Research and Development Program of Lvliang City [Grant No. 2025NY11] and the Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System in Shanxi Province [Grant No. 2025CYJSTX08] and the Central Government-Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project [Grant No. YDZJSX2024C017].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABTS | 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid radical scavenging activities |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging activities |

| FRAP | ferric-reducing antioxidant power |

| SP | total soluble protein |

| SS | soluble sugar |

| TFC | total flavonoid content |

| TPC | total phenolic content |

| Vc | vitamin C |

References

- Guo, G.; Pan, B.; Yi, X.; Khan, A.; Zhu, X.; Ge, W.; Liu, J.; Diao, W.; Wang, S. Genetic diversity between local landraces and current breeding lines of pepper in China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Zou, X. Geographical and Ecological Differences in Pepper Cultivation and Consumption in China. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 718517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, H.; He, C.; Mumtaz, M.A.; Hao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, W.; Zhu, J.; Bao, W.; Cheng, S.; Zhu, G.; et al. Fine mapping and identification of candidate genes for fruit color in pepper (Capsicum chinense). Sci. Hortic. 2023, 310, 111724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.; Roriz, C.L.; Morales, P.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Food colorants: Challenges, opportunities and current desires of agro-industries to ensure consumer expectations and regulatory practices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 52, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azlan, A.; Sultana, S.; Huei, C.S.; Razman, M.R. Antioxidant, Anti-Obesity, Nutritional and Other Beneficial Effects of Different Chili Pepper: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Crosby, K.; Yoo, K.S.; Leskovar, D.I.; Jifon, J.; Patil, B.S. Ascorbic acid, capsaicinoid, and flavonoid aglycone concentrations as a function of fruit maturity stage in greenhouse-grown peppers. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 33, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, L.; Simkin, A.J.; George Priya Doss, C.; Siva, R. Fruit ripening: Dynamics and integrated analysis of carotenoids and anthocyanins. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, L.R.; Talcott, S.T.; Brenes, C.H.; Villalon, B. Changes in phytochemical and antioxidant activity of selected pepper cultivars (Capsicum species) as influenced by maturity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, E.; Teka, T.A.; Nandasiri, R.; Rout, J.R.; Harouna, D.V.; Astatkie, T.; Urugo, M.M. Fruit By-Products and Their Industrial Applications for Nutritional Benefits and Health Promotion: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Kapoor, B.; Gulati, M.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, M.; Singh, S.K.; Awasthi, A. Sweet pepper and its principle constituent capsiate: Functional properties and health benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Rana, R.M.; Ahmar, S.; Saeed, S.; Gulzar, A.; Khan, M.A.; Wattoo, F.M.; Wang, X.; Branca, F.; Mora-Poblete, F.; et al. Effect of Drought Stress on Capsaicin and Antioxidant Contents in Pepper Genotypes at Reproductive Stage. Plants 2021, 10, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, V.C.; Reimer, J.J.; Wormit, A. Color for Life: Biosynthesis and Distribution of Phenolic Compounds in Pepper (Capsicum annuum). Agriculture 2019, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Shang, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Ren, H.; Hu, X.; Yi, J. Effect of ripening and variety on the physiochemical quality and flavor of fermented Chinese chili pepper (Paojiao). Food Chem. 2022, 368, 130797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.H.; Kim, M.H.; Han, Y.S. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of colored peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megat Ahmad Azman, P.N.; Shamsudin, R.; Che Man, H.; Ya’acob, M.E. Some Physical Properties and Mass Modelling of Pepper Berries (Piper nigrum L.), Variety Kuching, at Different Maturity Levels. Processes 2020, 8, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, L.H. Red pepper (Capsicum spp.) fruit: A model for the study of secondary metabolite product distribution and its management. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1744, 020034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, Z.; Bedő, J.; Pápai, B.; Tóth-Lencsés, A.K.; Csilléry, G.; Szőke, A.; Bányai-Stefanovits, É.; Kiss, E.; Veres, A. Ripening-Induced Changes in the Nutraceutical Compounds of Differently Coloured Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Breeding Lines. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, T.; Ranilović, J.; Gajari, D.; Tomić-Obrdalj, H.; Šubarić, D.; Moslavac, T.; Cikoš, A.-M.; Jokić, S. Podravka and Slavonka Varieties of Pepper Seeds (Capsicum annuum L.) as a New Source of Highly Nutritional Edible Oil. Foods 2020, 9, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, N.; Kaur, C.; George, B.; Singh, B.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidant constituents in some sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes during maturity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, P.S.; Landhäusser, S.M. A method for routine measurements of total sugar and starch content in woody plant tissues. Tree Physiol. 2004, 24, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-Z.; Zhou, G.-S. Effects of water stress and high nocturnal temperature on photosynthesis and nitrogen level of a perennial grass Leymus chinensis. Plant Soil 2005, 269, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mæhre, H.K.; Dalheim, L.; Edvinsen, G.K.; Elvevoll, E.O.; Jensen, I.-J. Protein Determination—Method Matters. Foods 2018, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Duan, X.; An, Y.; He, J.; Li, J.; Xian, J.; Zhou, D. An Analysis of Capsaicin, Dihydrocapsaicin, Vitamin C and Flavones in Different Tissues during the Development of Ornamental Pepper. Plants 2024, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva, T.L.; Aguiar-Oliveira, E.; Mazalli, M.R.; Kamimura, E.S.; Maldonado, R.R. Comparison between titrimetric and spectrophotometric methods for quantification of vitamin C. Food Chem. 2017, 224, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabiya, R. Spectrophotometric Determination of Total Phenolic Content for Standardization of Various Phyllanthus Species. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2019, 12, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Gillespie, K.M. Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, D.; Daniel, M. A critical evaluation on the reliability of two aluminum chloride chelation methods for quantification of flavonoids. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1365–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bai, J.; Duan, X.; Wang, J. Accumulation characteristics of carotenoids and adaptive fruit color variation in ornamental pepper. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 275, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian, F.S.; Li, W.; Beta, T. Measurement of anthocyanins and other phytochemicals in purple wheat. Food Chem. 2008, 109, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareček, V.; Mikyška, A.; Hampel, D.; Čejka, P.; Neuwirthová, J.; Malachová, A.; Cerkal, R. ABTS and DPPH methods as a tool for studying antioxidant capacity of spring barley and malt. J. Cereal Sci. 2017, 73, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.A. Approach to Optimization of FRAP Methodology for Studies Based on Selected Monoterpenes. Molecules 2020, 25, 5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lightbourn, G.J.; Griesbach, R.J.; Novotny, J.A.; Clevidence, B.A.; Rao, D.D.; Stommel, J.R. Effects of anthocyanin and carotenoid combinations on foliage and immature fruit color of Capsicum annuum L. J. Hered. 2008, 99, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripodi, P.; Ficcadenti, N.; Rotino, G.L.; Festa, G.; Bertone, A.; Pepe, A.; Caramanico, R.; Migliori, C.A.; Spadafora, D.; Schiavi, M.; et al. Genotypic and environmental effects on the agronomic, health-related compounds and antioxidant properties of chilli peppers for diverse market destinations. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4550–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Gui, X.-L.; Chang, X.-B.; Gong, Z.-H. A further analysis of the relationship between yellow ripe-fruit color and the capsanthin-capsorubin synthase gene in pepper (Capsicum sp.) indicated a new mutant variant in C. annuum and a tandem repeat structure in promoter region. PLoS ONE 2017, 8, e61996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, G.-I.; Almajano, M.P. Red Fruits: Extraction of Antioxidants, Phenolic Content, and Radical Scavenging Determination: A Review. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Ro, N.; Kim, J.; Ko, H.C.; Lee, S.; Oh, H.; Kim, B.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, G.A. Characterization of Diverse Pepper (Capsicum spp.) Germplasms Based on Agro-Morphological Traits and Phytochemical Contents. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, M.; Kalita, D.; Bartolo, M.E.; Jayanty, S.S. Capsaicinoids, Polyphenols and Antioxidant Activities of Capsicum annuum: Comparative Study of the Effect of Ripening Stage and Cooking Methods. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.W.; Momin, C.M.; Acharya, P.; Kabir, J.; Debnath, M.K.; Dhua, R.S. Dynamics of changes in bioactive molecules and antioxidant potential of Capsicum chinense Jacq. cv. Habanero at nine maturity stages. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionică, M.E.; Nour, V.; Trandafir, I. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of hot pepper fruits at different stages of growth and ripening. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2017, 90, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Azzarello, E.; Pollastri, S.; Tattini, M. Flavonoids as antioxidants in plants: Location and functional significance. Plant Sci. 2012, 196, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada, D.N.; Pulicherla, S.R.; Holguin, F.O. Widely Targeted Metabolomics Reveals Metabolite Diversity in Jalapeño and Serrano Chile Peppers (Capsicum annuum L.). Metabolites 2023, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, A.; Jelodar, G.; Nazifi, S.; Sajedianfard, J. An Overview of the Characteristics and Function of Vitamin C in Various Tissues: Relying on its Antioxidant Function. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci. 2016, 18, e4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborthy, A.; Ramani, P.; Sherlin, H.J.; Premkumar, P.; Natesan, A. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant activity of Vitamin C in oral environment. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2014, 25, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, J.A.; Hernández, M.S.; Melgarejo, L.M.; Martínez, O.; Fernández-Trujillo, J.P. Physiological behavior and quality traits during fruit growth and ripening of four Amazonic hot pepper accessions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola-Díaz, M.D.C.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; López de Andrés, J.; Voltes-Martínez, A.; Zamora, A.; Pérez-Molina, G.M.; Castro, D.J.; Marchal, J.A.; Verardo, V. Evaluation of Phenolic Compounds and Pigments Content in Yellow Bell Pepper Wastes. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.M.; Yusof, N.A.; Yahaya, A.F.; Rozali, N.N.M.; Othman, R. Carotenoids of Capsicum Fruits: Pigment Profile and Health-Promoting Functional Attributes. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, C.R.; Carvalho, T.T.; Manchope, M.F.; Artero, N.A.; Rasquel-Oliveira, F.S.; Fattori, V.; Casagrande, R.; Verri, W.A.; McPhee, D.J. Therapeutic Potential of Flavonoids in Pain and Inflammation: Mechanisms of Action, Pre-Clinical and Clinical Data, and Pharmaceutical Development. Molecules 2020, 25, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, A.; Ferreres, F.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Gil, M.I. Characterization and quantitation of antioxidant constituents of sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 3861–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Suh, D.H.; Jung, E.S.; Park, H.M.; Jung, G.-Y.; Do, S.-G.; Lee, C.H. Metabolomics of Lonicera caerulea fruit during ripening and its relationship with color and antioxidant activity. Food Res. Int. 2015, 78, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).