Abstract

Nitrogen (N) is a key nutrient for grapevine development, influencing from biomass formation to photosynthetic efficiency and grape quality. However, despite the widespread adoption of grafted plants in modern viticulture, understanding of how different scion–rootstock combinations modulate the uptake of different forms of N present in the soil remains limited. In this context, assessing the nutrient uptake efficiency of grapevines can be a strategy for selecting efficient cultivars, especially in nutritionally poor environments. This study aimed to assess the uptake efficiency of N forms by ‘Chardonnay’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’. Vines were subjected to Hoagland’s nutrient solution at 50% total strength for 21 days, followed by nutrient depletion and a 72 h kinetic uptake assay. Morphological, physiological, biochemical and uptake-related parameters—Vmax, Km, Cmin and influx (I)—were assessed. ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto the ‘IAC 572’ rootstock was the most efficient in the uptake of both NO3− and NH4+, as it showed the lowest Km and Cmin values and a high influx in relation to the other grapevines evaluated. In general, the ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grafted onto the ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘IAC 572’ exhibited the highest affinity (i.e., lower Km) for N forms, indicating that these combinations are more adaptable to environments with low N availability or require lower N inputs. These findings highlight the importance of using kinetic parameters in plant selection, because they can point out the efficient use of and ability to uptake different N forms, in addition to selecting plants that are efficient at uptaking nutrients in nutritionally depleted soils, or even physiologically efficient with low fertilization rates.

1. Introduction

Soils cultivated with vineyards around the world are often characterized by low organic matter levels, which lead to low availability of mineral nitrogen (N) forms to vines. Balanced vineyard nutrition is essential to sustain vine vigor, optimize fruit quality, and ensure long-term soil fertility. Proper fertilization supports physiological efficiency and resilience against environmental stress [1,2]. Therefore, it is necessary to apply N to meet vines’ nutritional demands and to ensure high yield and the proper composition of both grape must and its by-products, such as juice and wine [3,4]. Nitrogen should preferably be applied at small doses to avoid excess soil mineral N forms, mainly nitrate (NO3−), which has high soil mobility and leaching potential [5]. This process can increase soil contamination, as well as subsurface and surface waters near vineyards [6,7].

When it comes to vine cultivation, rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’, as well as the cultivars Chardonnay (white grape) and Cabernet Sauvignon (red grape), are plant materials widely used in vineyards worldwide [8,9]. Rootstocks are often selected based on their resistance to diseases and pests, or even on their morphological features, such as fast growth [10,11,12]. Rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ is quite vigorous, well-developed and presents a deep root system, which adapts to a wide range of physical and chemical soil conditions [13,14]. Rootstock ‘SO4’ has a superficial root system and adapts to acidic soils with low natural fertility; yet, it shows a short growing season, high resistance to phylloxera (Daktulosphaira vitifoliae) and low resistance to frost [13,14]. Another example is the ‘IAC 572’ rootstock, which was selected for tropical regions, without cold tolerance, and high vegetative vigor features [15]. The rootstock ‘IAC 572’ was used in this study because it is one of the most widely used rootstocks in Brazil, especially in tropical and subtropical climates. Developed by the Agronomic Institute of Campinas, ‘IAC 572’ exhibits excellent performance in warm regions and compatibility with most commercial cultivars, both table and wine grapes. It also shows ease of rooting and good adaptation to nutritionally poor and sandy soils [16,17].

Cultivar Chardonnay, often referred to as a French cultivar, resulted from crossing between cultivars Pinot Noir and Gouais Blanc (also called ‘Heunisch Weiss’), from Croatia [18,19]. Cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon has French origin and descends from two cultivars, namely, ‘Cabernet Franc’ and ‘Sauvignon Blanc’ [19,20]. Accordingly, scion cultivars are grafted onto resistant rootstocks adapted to the intrinsic circumstances of the growing region in order to minimize the impacts of different diseases and to enhance vine yield as well. However, the international literature provides little or no information on the most efficient rootstocks and cultivars in taking up N, mainly when they are grown under subtropical climate.

Research on nitrogen uptake in grapevines has evolved from early work describing the forms of nitrogen absorbed by roots and their influence on vegetative growth to more recent studies demonstrating that rootstocks differ in their capacity to acquire, transport, and assimilate nitrogen [3,5,10]. It is now well established that the rootstock plays a central role in determining nitrogen uptake efficiency and in regulating the supply of N to the scion, with significant consequences for vine vigor, nutrient status, and yield performance [8,21,22,23]. Advances in root physiology and nutrient flux methodologies have led to the incorporation of kinetic parameters—such as Vmax, Km, and Cmin—as tools to quantify nutrient uptake capacity and affinity [24,25,26,27,28]. The kinetic parameters help contextualize how different grapevine rootstocks respond to nitrogen availability and support more precise rootstock selection and nitrogen management strategies, especially because when selecting the combination of grafted vines (rootstock/scion), the efficiency of N uptake, which is the element that most impacts grape yield, grape composition and its by-products, such as wines and juices [4,24], is not considered. Furthermore, plants uptake N mainly in the forms of nitrate (NO3−) or ammonium (NH4+), and this process is facilitated by transport proteins that are in the membranes of the cells of the epidermis and cortex of the roots [29]. These transporters can have different levels of affinity for N forms, being divided into two types: high-affinity (HATS) and low-affinity (LATS). Generally, HATS work better at lower concentrations (below 0.5 mmol L−1), while LATS are more effective at higher concentrations (above 0.5 mmol L−1). Therefore, it is expected that plants that adapt to environments with fewer nutrients activate high-affinity systems, especially for N [30,31].

In this context, the process to select the most efficient rootstocks and cultivars in N uptake can be performed by estimating kinetic parameters, such as maximum uptake rate (Vmax), Michaelis-Menten constant (Km), minimum concentration (Cmin) and influx (I) [24,32,33,34]. Vmax is the maximum uptake rate recorded for membrane transporters, i.e., when all available transport sites are loaded. Cmin is the concentration at which ions’ net uptake stops before the solution is fully depleted. Km refers to the carrier affinity coefficient for the solute, which is equal to the substrate ion concentration at half the maximum transport rate. Influx represents the amount of nutrient absorbed by the mass of roots in a unit of time [25,26,27]. Thus, the kinetic parameters of nutrient uptake quantitatively describe the rate of uptake of nutrient ions by plant roots as a function of the concentration of these ions in the soil solution. In addition to kinetic parameters, physiological (photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance to water vapor, intercellular CO2 concentration, transpiration rate, water use efficiency, for example) and biochemical (chlorophyll a fluorescence and photosynthetic pigments, for example) variables can help select the most efficient rootstocks and cultivars in N uptake, since these variables are closely linked to nutrient uptake in plants [24,35,36].

Recent studies demonstrate that rootstocks differ significantly in their efficiency at taking up nitrogen and other nutrients, affecting vigor, leaf composition, and the productive performance of the grafted scion [21,22]. In this context, the use of kinetic parameters allows the selection of rootstocks capable of maintaining high efficiency even under conditions of low nutrient availability and in nutritionally poor soils, contributing to greater productive stability and better use of fertilizers, thereby reducing costs and environmental impacts [37,38,39]. In addition to enabling the selection of rootstocks and cultivars with greater efficiency in N uptake, which allows for a reduction in the doses or frequency of N application in vineyards, it is also expected to maintain a high yield of grapes, must, and wine with the desired composition [40,41]. Thus, the use of uptake kinetics in viticulture represents a modern and strategic tool contributing to management strategies, beyond helps achieve more sustainable viticulture, which is a globally desirable accomplishment. This study aimed to assess the uptake efficiency of N forms by ‘Chardonnay’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grafted onto rootstocks the ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Treatments

The experiment was conducted from March to April 2021, in a greenhouse, at the Federal University of Santa Maria (UFSM), Santa Maria City, Rio Grande do Sul State (RS), Southern Brazil. Air temperature in the greenhouse was 25 °C, and relative humidity was maintained at 60% throughout the experiment by a fan-pad system. The cultivars Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon produced under a table-type grafting system, although using fork grafting, were grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’ (rootstock crossing 101-14 MGT—Vitis Riparia × Vitis rupestris × Vitis caribaea), ‘Paulsen 1103’ (Vitis berlandieri × Vitis rupestres) and ‘SO4’ ((Teleki 4 Sel. Oppenheim) (Vitis berlandieri × Vitis riparia)). The study followed a completely randomized experimental design, with six repetitions—each plant was taken as one repetition. Accordingly, ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto the rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’, and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grafted onto the rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’, ‘SO4’ were evaluated. This process corresponded to treatments applied to two cultivars, namely, ‘Chardonnay’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, and to three rootstocks: ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’.

Five-month-old grafted cultivars were carefully removed from the tubes in March 2021. The substrate on the roots was removed, and the roots were carefully washed in distilled water until the substrate was fully removed. The vines (with 10 to 15 leaves at transplantation time, as well as similar height and stem diameter) were transferred to 8 L plastic containers with 5 L of Hoagland’s nutrient solution at 50% full strength [42]. The nutrient solution comprised the following (mg L−1): N-NO3− = 98, N-NH4+ = 7, P = 15.5, K = 117, Ca = 80, Mg = 24.3, S = 35, Fe-EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) = 2.5, Cu = 0.01, Zn = 0.075, Mn = 0.25, B = 0.25 and Mo = 0.005. The plants remained in the pots for 21 days until the first acclimatization stage was complete. The nutrient solution’s pH was adjusted to 6.0 daily by the addition of HCl 1 mol L−1 or NaOH 1 mol L−1 to it, and the solution was changed every five days. A 3 mm thick Styrofoam sheet was placed on the surface of each pot to help plant fixation and reduce evaporation. The blade had two holes: a central one to support the grapevines and a diagonal one to allow the aeration PVC (polyvinyl chloride) tube to pass through it. This tube was connected to a free air compressor.

2.2. Nutrient Depletion and Kinetics of NO3− and NH4+ Uptake

Vines were subjected to a 15-day internal nutrient reserves depletion period with the addition of calcium sulfate (0.1 mol L−1 CaSO4) after the acclimatization period. CaSO4 was added to maintain root integrity and to preserve the membrane’s electrochemical potential, as well as cell wall integrity [32]. Vines were supplied again with Hoagland’s solution at 50% full strength after the nutrient depletion period [32]. Nutrient depletion refers to the reduction in the concentration of a nutrient in the soil solution adjacent to the root surface (rhizosphere) as a result of continuous uptake by the plant and the rate of replenishment of that nutrient in the absorption zone [43]. They remained in the solution for 1 h so that the system could reach steady-state uptake conditions. Kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km and Cmin) and nitrate (NO3−) and ammonium (NH4+) uptake rates by vines were determined through the methodology described by Paula et al. [32,44]. A 50 mL aliquot of solution was collected from each pot (time zero) at the time of changing the Hoagland solution at 50% full strength to start the kinetic time-course sampling (nutrient uptake pattern throughout the experimental period). Subsequently, 50 mL aliquots were collected every 6 h for the first 24 h, every 3 h between 24 and 48 h, and every 1 h between 48 and 72 h. Thus, the solution was collected for 72 h, totaling 37 collections.

The solutions were stored and frozen at −4 °C for further N form analysis. NO3− and NH4+ concentrations were quantified using an autoanalyzer (Skalar San++ continuous flow analyzer, 1074 sampler, Breda, The Netherlands).

2.3. Photosynthetic Variables

Measurements were taken after internal nutrient reserves depletion in the morning, between 08:00 a.m. and 10:00 a.m., using a portable Infrared Gas Analyzer (IRGA) (LI-6400 XT, LI-COR Biosciences, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA). Photosynthetic variables were measured in middle-third leaves that were fully expanded and healthy in all treatments. Net CO2 assimilation rate (photosynthetic rate) (A), stomatal conductance to water vapor (Gs), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), transpiration rate (E), water use efficiency (WUE) and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (A/Ci) (by Ribulose1,5-Biphostat Carboxylase/Oxygenase) were the assessed variables. Gas exchange settings were carried out in a leaf chamber at a CO2 concentration of 400 µmol mol−1, photon flux density of 1000 µmol m−2 s−1, relative air humidity of 50% ± 5% and a temperature of 20 °C/25 °C. Variables A, Ci, E and Gs were calculated using the equations proposed by von Caemmerer and Farquhar [45].

2.4. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Assessment

Chlorophyll a fluorescence emission was analyzed after internal nutrient reserves depletion in fully expanded leaves using a portable modulated light fluorometer (Junior-Pam Chlorophyll Fluorometer, Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). Measurements were taken in the morning (07:30 a.m.–08:30 a.m.) on a sunny day. Leaves were previously adapted to the dark for 30 min, with the aid of an aluminum foil envelope, to measure the initial fluorescence (Fo). Subsequently, they were subjected to a saturating light pulse (10,000 µmol m−2 s−1) for 0.6 s to determine the maximum fluorescence (Fm). Maximum PSII quantum yield (Fv/Fm), PSII quantum efficiency (Y(II)), electron transport rate (ETRm) and non-photochemical dissipation (NPQ) were calculated based on the initially measured parameters [46].

2.5. Biochemical Variables in Leaves and Roots

Complete leaf and root samples were collected after the 72 h solution collection, frozen in liquid N and stored in an ultrafreezer (−80 °C). Subsequently, they were macerated in liquid N and used to determine the activity of antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidases (POD), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentration, substances reactive to thiobarbituric acid (TBARS) and nitrate reductase activity.

Photosynthetic pigments were determined in fresh leaf samples based on the methodology proposed by Hiscox and Israelstam [47]. Solution absorbance was measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Celm, E-205D, São Paulo, Brazil) at 663, 645 and 470 nm for chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and carotenoids, respectively, and estimated using the equation by Lichtenthaler [48]. Total chlorophyll represented the sum of chlorophyll a and b values.

The activity of the enzymes guaiacol peroxidase (POD) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) in grape leaf and root samples was determined using the methodology proposed by Zhu et al. [49]. The activity of non-specific peroxidases in the extract was determined based on Zeraik et al. [50] using ‘guaiacol’ as a substrate. SOD activity was determined based on the spectrophotometric method described by Giannopolitis and Ries [51]. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) concentration was set using the methodology proposed by Loreto and Velikova [52]. Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) determination was estimated using the method described by El-Moshaty et al. [53].

The activity of nitrate reductase (NR) (µM NO2− g MF−1 h−1) was analyzed using the method described by Jaworski [54], with modifications. A standard curve was plotted to calculate enzyme activity based on the amount of nitrite released by plant tissues into the incubation solution.

2.6. Grapevine Collection and N Analysis in Tissues

Plants were removed from pots containing the nutrient solution after the 72 h kinetic time-course sampling assessment. They were divided into leaves, stems (graft and rootstock) and roots. The remaining nutrient solution volume was measured using a graduated cylinder. Leaf, stem and root fresh matter was measured on a precision scale (Shimadzu, UX620H, Kyoto, Japan). Samples were dried in an oven at 65 °C until a constant mass was reached. Dry matter weight was determined, and the samples were ground in a Willey mill with a 2 mm sieve. Subsequently, total N concentration in plant organs was determined, therefore, the samples were subjected to sulfur digestion [55]. The extract digestion was distilled in a micro-Kjeldahl distiller (Tecnal, TE-0363, São Paulo, Brazil) and titrated with 0.025 mol L−1 sulfuric acid to determine total N [55]. Finally, nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) values and N uptake efficiency (NUtE) were evaluated as described by Congreves et al. [56].

2.7. Root System Morphology

Roots were scanned using a scanner (Regent Instruments, Inc., EPSON Expression 11000 scanner equipped with additional light (TPU), Quebec, QC, Canada). Root morphological features were analyzed using WinRhizo Pro 2013 software (Regent Instrument Inc., Quebec City, QC, Canada) [57] at 600 dpi resolution. In order to do so, root fragments were inserted after thawing on an acrylic tub (20 cm in width × 30 cm in length, with a 1 cm water blade); roots were cut to facilitate their random arrangement on the acrylic tub. Root surface area (cm2 plant−1), root volume (cm3 plant−1), mean diameter (mm), total root length (cm plant−1) and root distribution rate at each diameter range were measured.

2.8. Kinetic Parameters Related to the Uptake of N Forms

The initial and final solution volumes in the pots, root fresh matter values, and Vmax and Km values were calculated using Influx 1.0 software [44]—an evolution of Cinetica 2.0 software [58]—based on NO3− and NH4+ concentrations in Hoagland’s nutrient solution. NO3− and NH4+ concentrations in the nutrient solution were used to determine the Cmin value at the 72 h assessment time. All kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km, Cmin) were calculated individually through the best fit of regressions, according to the nutrient concentrations of each plant. The software estimates Vmax and Km using a nonlinear Michaelis–Menten regression, following the least-squares algorithm implemented internally in Influx. Equation (1), proposed by Michaelis–Menten and modified by Nielsen and Barber [59], was used to determine the net influx (IL) value per plant.

where Vmax is the maximum uptake rate recorded for membrane transporters, i.e., when all available transport sites are loaded; C is the concentration of nutrients in the solution at collection time; Cmin is the minimum concentration of nutrients over a 72 h period, i.e., the concentration at which the net uptake of ions stops before the solution is fully depleted; and Km refers to the carrier’s affinity coefficient for the solute, equal to the substrate ion concentration that corresponds to half the maximum transport rate.

IL = [Vmax (C − Cmin)]/[Km + (C − Cmin)]

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Kinetic, photosynthetic, physiological, morphological and nutritional parameter results were subjected to homogeneity and normality tests. Subsequently, the collected data were processed and statistically analyzed in R statistical software [60]. Results were compared using the Tukey test (p < 0.05) when treatment effects were significant.

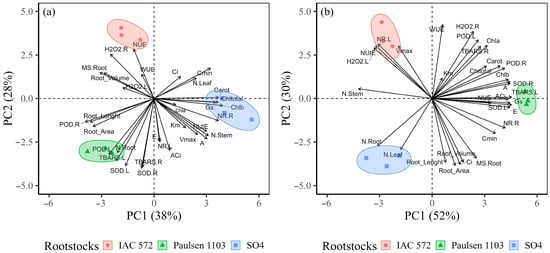

In addition, the data were subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) using the “factoextra” [61] and “FactoMineR” packages [62] in R statistical software [60]. PCA was performed based on a set of components (PC1 and PC2) that likely allowed explaining more complex interactions between the assessed variables and those mostly contributing to differences between treatments.

3. Results

3.1. Plant Growth and N Concentration in Organs

Dry matter production from shoots, roots and total did not statistically differ in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ (Table 1), with the exception of root dry matter production of ‘Chardonnay’, which showed the highest dry matter when grafted onto ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’. The highest N concentrations in stems and roots of Cabernet Sauvignon were observed when grafted with ‘SO4’ and ‘Paulsen 1103’, respectively. On the other hand, the lowest N concentrations in leaves, stems and roots of ‘Chardonnay’ vines were overall observed when the cultivar was grafted onto ‘Paulsen 1103’. Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) values and N uptake efficiency (NUtE) did not significantly differ in the cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’. Rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ accounted for the highest NUE value and the lowest NUtE value in the cultivar Chardonnay.

Table 1.

Dry matter production, total N concentration in organs, nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and nitrogen uptake efficiency (NUtE) of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ grapevines grafted onto the rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’, grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves.

3.2. Root Morphology

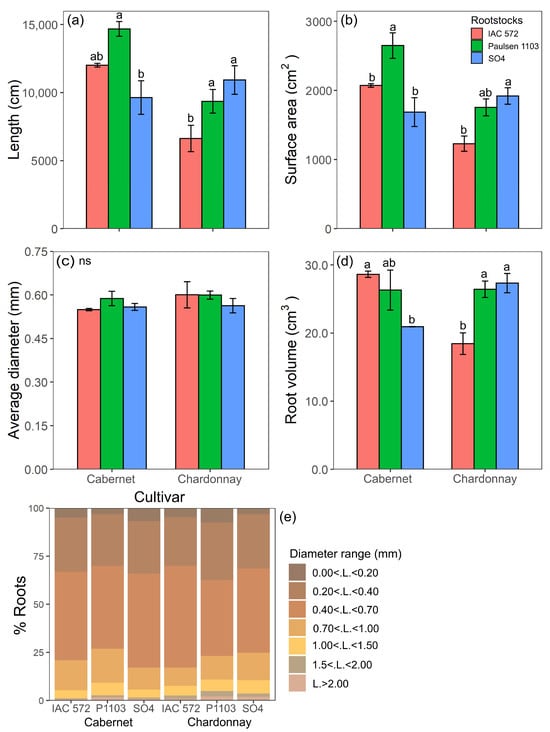

The highest root length, surface area and volume values recorded for ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ were observed when this cultivar was grafted onto ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘IAC 572’ (Figure 1a,b,d). The highest root length, surface area and volume values recorded for ‘Chardonnay’ were observed in this cultivar grafted onto ‘SO4’ and ‘Paulsen 1103’ (Figure 1a,b,d). Root diameter did not significantly differ among the rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ in the two assessed cultivars (Figure 1c). It was observed that 75% of roots in the cultivars Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ roots had diameters smaller than 0.7 mm (Figure 1e).

Figure 1.

Length (a), surface area (b), average diameter (c), root volume (d) and percentage distribution of roots for each diameter range (e) of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Lower case letters compare rootstocks in each cultivar by the Tukey test (p < 0.05). ns = not significant. Vertical bars represent standard deviation.

3.3. Kinetic Parameters Associated with NO3− and NH4+ Uptake

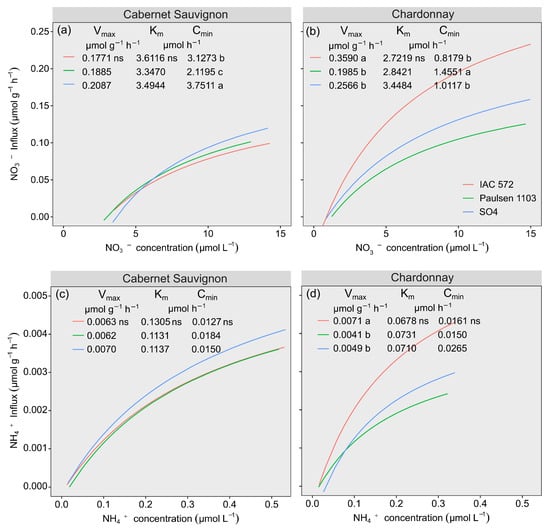

Vmax and Km values recorded for NO3− and NH4+ in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ did not significantly differ among ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ (Figure 2a,c). Km values did not significantly differ in ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ (Figure 2b,d). The highest Vmax values recorded for NO3− and NH4+ in ‘Chardonnay’ were observed in this cultivar grafted onto rootstock ‘IAC 572’ (Figure 2b,d). The highest Cmin values observed for NO3− in cultivars Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay were found in rootstocks ‘SO4’ and ‘Paulsen 1103’, respectively (Figure 2a,b). Cmin values recorded for NH4+ in cultivars Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay did not significantly differ among rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ (Figure 2c,d).

Figure 2.

Influx and uptake kinetic parameters of NO3− and NH4+ from ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (a,c) and ‘Chardonnay’ (b,d) grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Lower case letters compare rootstocks in each cultivar by the Tukey test (p < 0.05). ns = not significant.

NO3− and NH4+ uptake kinetics showed uptake differences between scion–rootstock combinations, as observed in the vine influx curve (Figure 2). Cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon started taking up NO3− and NH4+ in the solution, even at low concentrations, and continued doing so at similar levels when grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’. ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto the rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ started taking up even at low concentrations. Rootstock ‘IAC 572’ showed NO3− uptake at higher concentrations than ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ in the cultivar Chardonnay; therefore, it recorded lower Cmin values.

3.4. NO3− and NH4+ Uptake Assessment Through the Kinetic Kinetic Time-Course Sampling

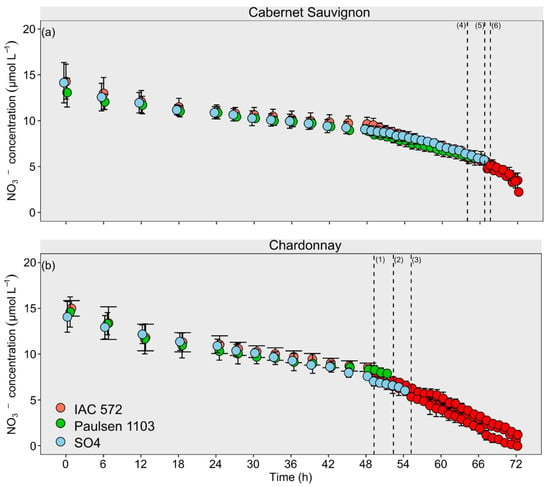

According to the NO3− uptake kinetic kinetic time-course sampling in the cultivars Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ behaved similarly up to approximately 48 h of assessment (Figure 3). Cmin values recorded for NO3− were first found in ‘Chardonnay’ (49 h) and, later on, in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (64 h). Cmin values recorded for NO3− in both cultivars were reached by rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’, respectively.

Figure 3.

Concentration decay of NO3− from ‘Chardonnay’ (a) and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (b) grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Superscript numbers represent the time to reach the lowest concentration (p < 0.05) in ‘Chardonnay’ on rootstocks (1) IAC 572; (2) Paulsen 1103; and (3) SO4; and in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ on rootstocks (4) IAC 572; (5) Paulsen 1103; and (6) SO4. Red dots: time reaching lowest concentration p < 0.05.

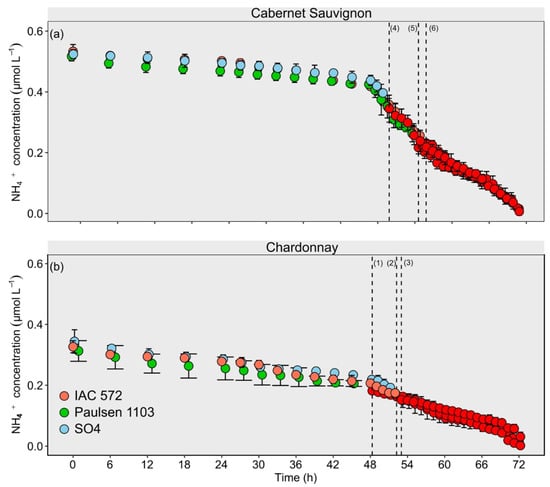

The three assessed rootstocks behaved similarly up to 48 h of assessment based on the NH4+ uptake kinetic kinetic time-course sampling in the cultivars Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay (Figure 4). Cmin values recorded for NH4+ in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ were first observed in rootstock ‘IAC 572’, which was followed by rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’.

Figure 4.

Concentration decay of NH4+ from ‘Chardonnay’ (a) and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (b) grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Superscript numbers represent the time to reach the lowest concentration (p < 0.05) in ‘Chardonnay’ on rootstocks (1) IAC 572; (2) Paulsen 1103; and (3) SO4; and in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ on rootstocks (4) IAC 572; (5) Paulsen 1103; and (6) SO4. Red dots: time reaching lowest concentration p < 0.05.

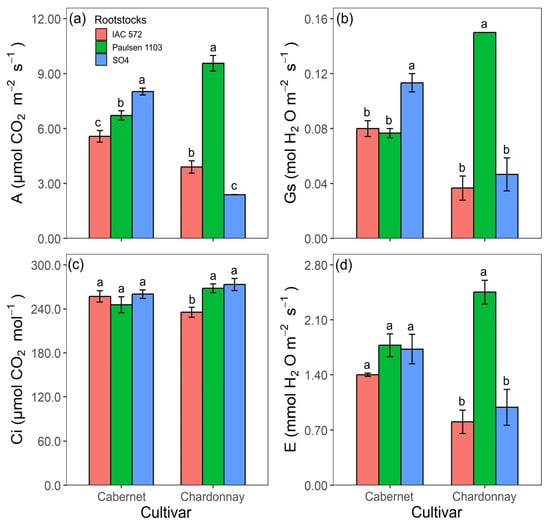

3.5. Photosynthetic Parameters

The highest A and Gs values in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ were recorded for rootstock ‘SO4’ (Figure 5a,b). Ci and E concentrations did not statistically differ among the assessed rootstocks (Figure 5c,d). The highest A, Gs and E values were recorded for rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ in cultivar Chardonnay (Figure 5a,b,d). The highest Ci values were observed when ‘Chardonnay’ was grafted onto rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ (Figure 5c).

Figure 5.

Net photosynthetic rate (A) (a), stomatal conductance (Gs) (b), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) (c) and transpiration rate (E) (d) in leaves of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Lower case letters compare rootstocks in each cultivar by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) (a, b, c). Vertical bars represent standard deviation.

3.6. Biochemical Variables in Leaves and Roots

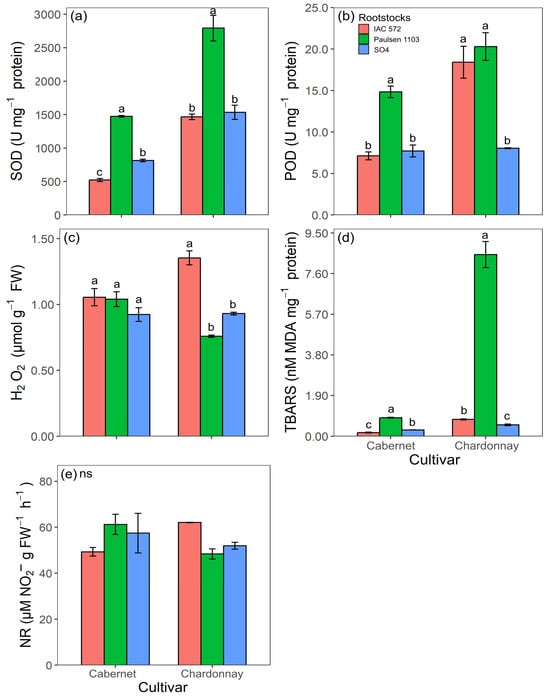

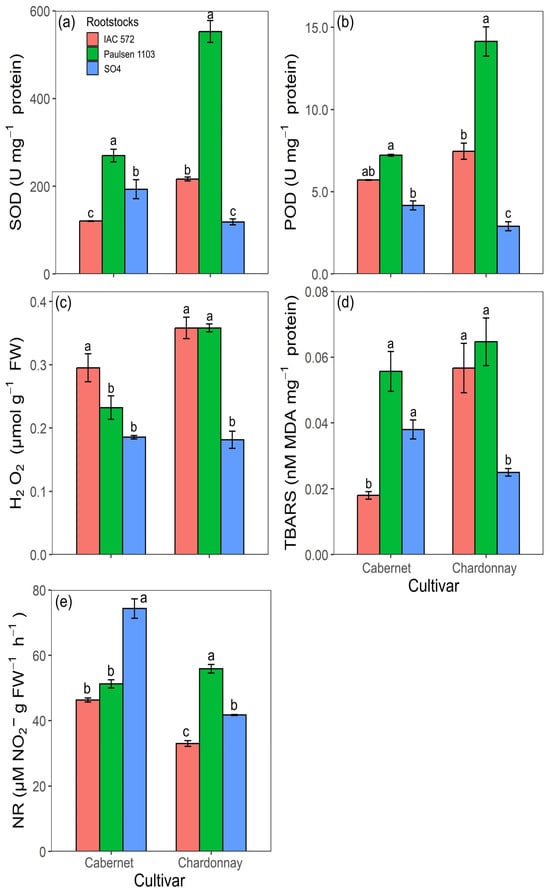

The highest values recorded for the activity of the enzymes SOD and POD, as well as for TBARS concentrations in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ leaves, were observed in rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ (Figure 6a,b,d). The highest leaf H2O2 concentration in ‘Chardonnay’ was observed when this cultivar was grafted onto ‘IAC 572’ (Figure 6c). The leaf H2O2 concentration in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ did not statistically differ among rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’, ‘IAC 572’ and ‘SO4’ (Figure 6c). The activity of the enzyme nitrate reductase in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ leaves did not significantly differ among the assessed rootstocks (Figure 7a).

Figure 6.

Superoxide dismutase activity (SOD) (a), guaiacol peroxidase activity (POD) (b), H2O2 concentration (c), MDA concentration (TBARS) (d) and nitrate reductase activity (NR) (e) in leaves of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Lower case letters compare rootstocks in each cultivar by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) (a, b, c). ns = not significant. Vertical bars represent standard deviation.

Figure 7.

Superoxide dismutase activity (SOD) (a), guaiacol peroxidase activity (POD) (b), H2O2 concentration (c), MDA concentration (TBARS) (d) and nitrate reductase activity (NR) (e) in roots of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Lower case letters compare rootstocks in each cultivar by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) (a, b, c). Vertical bars represent standard deviation.

The highest values recorded for the enzymes SOD and POD in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ roots were found in rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ (Figure 7a,b). Cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon grafted onto rootstock ‘IAC 572’ showed the highest H2O2 concentrations and the lowest TBARS concentrations (Figure 7c,d). ‘Chardonnay’ roots showed the highest H2O2 and TBARS concentrations in rootstocks ‘IAC 572’ and ‘Paulsen 1103’ (Figure 7c,d). The highest activity of the enzyme nitrate reductase observed in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ roots was recorded for rootstocks ‘SO4’ and ‘Paulsen 1103’ (Figure 7e).

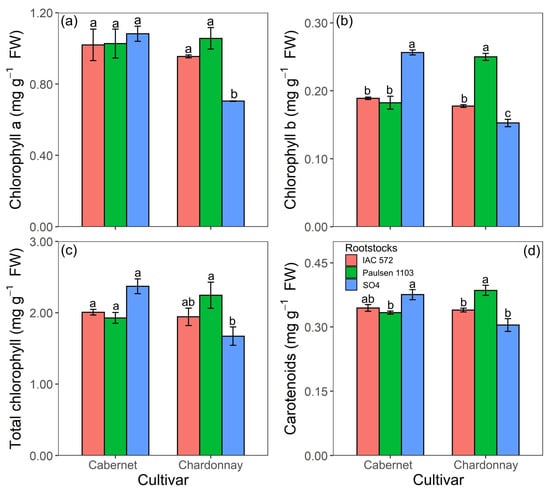

3.7. Photosynthetic Pigments

Chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll concentrations in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ did not statistically differ among rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’, ‘IAC 572’ and ‘SO4’. ‘Chardonnay’ showed the highest chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll concentrations in rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘IAC 572’ (Figure 8a,c). The highest chlorophyll b and carotenoid concentrations in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ were observed when this cultivar was grafted onto rootstock ‘SO4’ and in ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto ‘Paulsen 1103’ (Figure 8c,d).

Figure 8.

Chlorophyll a (a), chlorophyll b (b), total chlorophyll (c) and concentration of carotenoids (d) in leaves of ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ grapevines grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks grown in Hoagland nutrient solution after 15 d of reduced internal nutrient reserves. Lower case letters compare rootstocks in each cultivar by the Tukey test (p < 0.05) (a, b, c). Vertical bars represent standard deviation.

3.8. Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed by only extracting the first two components (PC1 and PC2); their sum explained 66% and 82% of the original data variability for the cultivars Cabernet Sauvignon and Chardonnay, respectively (Figure 9). PCA enabled the observation of the behavior of three different clusters within each cultivar. In the cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon, the rootstock ‘SO4’ was correlated with kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km and Cmin), photosynthesis (A, E, A/Ci, Ci), photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a, b, total and carotenoids), and N concentration in the leaves and stems (Figure 9a). Rootstock ‘IAC 572’ was correlated with NUE, WUE, root volume and dry matter, and H2O2 in the leaves and roots. On the other hand, rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ presented a negative correlation with Cmin and positive correlation with N accumulation in the roots, as well as with root length and surface area. Rootstock ‘SO4’ was influenced by root growth parameters (volume, surface area, length and dry matter), by N accumulation in the leaves and roots, and by Ci in cultivar Chardonnay (Figure 9b). Rootstock ‘IAC 572’ was correlated to Vmax, NUtE, H2O2 and NR in leaves. Rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ presented a correlation with kinetic parameters (Cmin), photosynthesis (A, E, Gs, A/Ci) and SOD.

Figure 9.

Relation between principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) from kinetic parameters (Vmax, Km and Cmin), morphological parameters (dry mass, N concentration in organs and root morphology), physiological parameters (photosynthesis), biochemicals (SOD, POD, H2O2, TBARS and nitrate reductase in the leaves and roots) and photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll a, b, total and carotenoids) of the grapevines ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ (a) and ‘Chardonnay’ (b) grafted onto ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’ rootstocks.

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological Parameters, Tissue Nutrients and Kinetic Parameters Related to N Uptake

N use efficiency (NUE) and N uptake efficiency (NUtE) did not significantly differ in cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’. However, cultivar Chardonnay grafted onto rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ presented the highest NUE value and the lowest NUtE value. This finding may have resulted from the lower N uptake efficiency, assumingly deriving from a greater ability to use N for dry matter; this refers to the fact that, in low N conditions, efficiency of uptake is more important than efficiency of utilization [63]. Furthermore, N assimilation is driven by N-acquiring enzymes such as nitrate reductase (NR), nitrite reductase (NiR) and glutamine synthetase (GS). This assimilation physiology can be influenced by factors such as light conditions or substrate availability. Despite the uptake and assimilation processes of N in grapevines having been elaborated at the transcriptional level in detail over the last few decades, little is known, based on the various N-forms, about the regulation of the gene expression of NR and the downstream enzymes NiR and GS in rootstocks [64].

Dry matter production did not differ among the grafted vines, but N concentrations were different among the assessed organs (leaf, stem and roots). This outcome may have happened because annual organs, such as leaves, present intense cell division and elongation; therefore, their increased dry matter amounts demand larger amounts of nutrients, such as N [65,66]. There is a strong correlation between graft growth, transpiration, and rootstock hydraulic conductance, suggesting that rootstocks can modulate N translocation to the shoot, controlling water flow in the plant. Similarly, graft union can influence N translocation to the shoot and the transport of N reserves to the roots. The degree of healing at the graft union can alter xylem anatomy locally. As a consequence, the hydraulic properties of the entire plant can be modified, impacting the movement of water, hormones, and other nutrients such as NO3− and NH4+ [67]. Thus, some rootstocks have the potential to perform better than others under low nutrient availability [23], including the effect of scion–rootstock combination, which was herein assessed; this finding evidenced that each rootstock behaves differently in combination with the scion cultivar.

The highest root length, surface area and volume values were observed in rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘IAC 572’ for ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’, and in ‘SO4’ and ‘Paulsen 1103’ for ‘Chardonnay’. These variables can be quite relevant for the nutrient uptake process, since more developed root systems can explore a larger soil volume; consequently, they can take up more nutrients. The difference in the behavior–response of root variables between the vines evaluated may be related to the genetic material of each cultivar or rootstock; findings similar to those obtained in this study were observed by Mahmud et al. [68], who assessed four different rootstocks and found different root yield behaviors—including that behavior was different even between physiological phases. Additionally, the highest root diameter rate was observed at size <07 mm, which is a positive finding, because a larger number of fine roots (smaller diameter) contributes to vines’ greater uptake of water and nutrients [69,70]. Furthermore, root growth can be impacted via poor phloem connections at the graft union, which limits shoot-to-root transport of assimilates. Finally, as nitrate reduction mainly occurs in grapevine leaves, the rootstock contribution to N translocation toward shoots may modulate the rate of N assimilation and thus the plant N status [64].

The highest Vmax values of NO3− and NH4+ observed in cultivar Chardonnay grafted onto rootstock ‘IAC 572’ indicate that this combination may have a higher density of NO3− uptake sites per root unit [24,71]. Furthermore, in general, the lowest Km values for NO3− and NH4+ ions were observed in ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto the ‘IAC 572’ rootstock; the lower the Km value, the higher the ion affinity of its transport sites. On the other hand, Vmax and Km values recorded for NO3− and NH4+ in cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon did not significantly differ among the three rootstocks. This finding suggests that the density of uptake sites per root unit and affinity of its transport sites is similar in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ among the rootstocks.

The lowest Cmin values recorded for NO3− and NH4+ ions in ‘Chardonnay’ and ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ were observed with the combination of rootstocks in the following order: ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’. This finding can be explained by the high NO3− and NH4+ uptake capacity by vines in solutions with low concentrations of both ions [33]. This finding suggests that the two herein assessed cultivars can be grown in solution or in soils with low NO3− availability, or that they can receive lower doses and fewer applications of nitrogen fertilizers when they are grafted onto rootstocks ‘IAC 572’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘SO4’.

4.2. Photosynthetic and Biochemical Variables

The highest A and Gs values observed for ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grafted onto rootstock ‘SO4’ and for ‘Chardonnay’ grafted onto ‘Paulsen 1103’ can be explained by the different carboxylation efficacy of the grafted vines [72]. However, these highest A and Gs values did not lead to higher biomass production in these cultivars, because the dry matter did not differ among rootstocks. Assumingly, the vine’s development time was insufficient for the increased photosynthetic activity to translate into greater biomass production, given that the plants were still in an early stage (five months old). The vines showed different Ci concentration values, and this variation may indicate that stomatal conductance does not limit the net photosynthetic rate and that it may account for CO2 accumulation in intercellular spaces of grapevines under low N levels at a slower CO2 fixation rate [73]. Furthermore, vigorous rootstocks, such as ‘Paulsen 1103’, showed higher photosynthesis and conductance rates.

The highest activities of the enzymes SOD and POD, as well as malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration, which are some of the lipid peroxidation products in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’ leaves and roots, were observed in rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’. This finding points towards oxidative stress in this rootstock, because it was not possible to avoid damaging membrane lipids even under increased activity of antioxidant enzymes [74,75]. Oxidative stress was possibly induced by the production of other reactive oxygen species, such as hydroxyl radical or superoxide anion [76,77], because there was no significant difference in this rootstock’s H2O2 concentration. There was no significant reduction in biomass production in this rootstock even when variables indicated oxidative stress. Assumingly, enzymes’ activation and the activation of other antioxidant agents prevented greater damage to plants and avoided negative effects on biomass production [74,75].

NO3− is the main inorganic N form available to plants, and nitrate reductase is the first enzyme assimilating the inorganic N route into complex organic molecules; therefore, it plays a key role in plant metabolism [78] as the limiting stage in this process. Our results show that the rootstocks did not differ in the activity of enzyme nitrate reductase in leaves, but rootstocks ‘SO4’ and ‘Paulsen 1103’ showed the highest activity of this enzyme in both cultivars. The higher activity of nitrate reductase in the roots highlights greater nitrate availability and reduction in these rootstocks’ root system because this enzyme is quite responsive to its substrate [79]. Furthermore, the higher activity of nitrate reductase can point towards greater plant ability to synthesize proteins [80], which is crucial for the plants’ life cycle.

Chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll concentrations in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grafted onto rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’, ‘IAC 572’ and ‘SO4’ did not significantly differ from each other. On the other hand, ‘Chardonnay’ showed the highest chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll concentrations in rootstocks ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘IAC 572’. Furthermore, the highest chlorophyll b and carotenoid concentrations in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ were observed in rootstock ‘SO4’, and the highest chlorophyll b and carotenoids concentrations in ‘Chardonnay’ were observed in rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’. This finding may indicate a greater ability to absorb light radiation [81], which is supported by the higher photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance recorded for these rootstocks. However, assumingly, this greater radiation absorption capacity and photosynthetic rate were not expressed in higher biomass production due to the relatively short time the plants were exposed to the nutrient solution effect. This could limit the growth of the vines, in addition to compromising the metabolism of the plants, resulting in nutritional stress.

This response–behavior of grapevines may be related to the functioning of N transporters, which vary according to their affinity for NO3− and NH4+, and can be classified as high affinity (HATS), low affinity (LATS) or dual affinity. NO3− is taken up by transporters of the NRT (Nitrate Transporter) gene family, while the AMT (Ammonium Transporter) gene family acts for NH4+ [82,83,84]. AMTs and NRTs are essential for supplying the N required for the synthesis of essential photosynthetic components, such as chlorophyll and RuBisCO. NO3− uptake in cells occurs through transporters present in the plasma membrane, which can be classified according to their affinity for the substrate. There are high affinity transporters (HATS—“High Affinity Transport System”) that operate under low concentrations of NO3− [85,86] and can be divided into constitutive (cHATS), which operate at concentrations of approximately 0.2 mM, and induced (iHATS), which operate at concentrations lower than 0.2 mM [87]. There are also low affinity transporters (LATS—“Low Affinity Transport System”) that operate at concentrations above 1 mM [87]. HATS and LATS are encoded, respectively, by the NRT2 and NRT1 gene families [85,86]. Meanwhile, at higher external concentrations of NH4+, there is evidence that the nutrient probably permeates root cells as NH3 and NH4+ through two distinct mechanisms. The first is the passive and electroneutral NH3 influx/efflux cycle, putatively facilitated by aquaporins [85], which results in the hyperaccumulation of the charged form in the vacuole. The second includes NH4+ influx, likely mediated by other plasma membrane channels, such as specific nonselective cation (NSCC) and potassium (K+) channels, among which is AKT1. At low external NH4+ concentrations (<1 mM), NH4+ influx is a saturable and highly controlled process, mediated by members of the AMT1 subfamily (of the Ammonium Transporter/Methylammonium Permease family) through NH4+ uniport or NH3/H+ cotransport [85]. Thus, the NH3 and NH4+ influx is responsive to the plant’s N status and is subject to diurnal regulation, varying throughout the day [82].

4.3. Principal Component Analysis

According to PCA results, the assessed rootstocks (‘SO4’, ‘Paulsen 1103’ and ‘IAC 572’) presented different correlations with each cultivar (‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ and ‘Chardonnay’). This finding clarifies the specificity between each rootstock and cultivar. It is important to highlight that cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon grafted onto rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ showed negative correlation with Cmin, which is interesting because the lower the Cmin value, the lower the nutrient concentrations that roots can extract from the soil solution, and it increases ion affinity with the uptake sites, a fact that results in increased efficiency in taking up N forms [24]. Accordingly, rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ can increase N accumulation in the roots and its subsequent translocation to the leaves. This process helps physiological activity, such as A, E and Gs, as well as contributes to CO2 assimilation. Thus, it enables greater root system development, such as root length, surface area and volume, as seen in the PCA recorded herein. Similar results were recorded by Kulmann et al. [24]. On the other hand, rootstock ‘IAC 572’ showed a positive correlation with H2O2 and NR in the leaves in the current study. This outcome likely occurred due to rootstock energy expenditure when it was subjected to low concentrations of nutrients, such as N, which can promote ROS (reactive oxygen species) overproduction. Furthermore, plants produce antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD, to prevent ROS-induced oxidative damage and to maintain homeostasis in plant cells [86]. In addition, the superoxide radical (O2•–) is often the first ROS formed in the cell; it can be detoxified from the cell through SOD activity and generate H2O2 as a reaction byproduct [87]. This process partially explains the correlations observed in PCA.

5. Conclusions

The results demonstrate that the scion–rootstock combination is a determining factor for optimizing nitrogen (N) uptake and use in grapevine, directly influencing the physiological performance of the vines.

Cultivar Chardonnay grafted onto the ‘IAC 572’ rootstock and cultivar Cabernet Sauvignon grafted onto rootstock ‘Paulsen 1103’ were the most efficient in the uptake of NO3– because they presented the lowest Km and Cmin values. This supports the idea that these combinations will be more successful in environments with low N availability or even when subjected to low doses of nitrogen fertilizers.

The use of kinetic parameters of nutrient uptake can be an essential tool for fruit growing, as it allows for the selection of more nutrient-efficient genotypes, the selection of cultivars based on soil nutrient availability, and the optimization of fertilizer use.

For studies of this nature, the limitations lie in the fact that controlled trials often oversimplify nutrient dynamics, which can mask the spatial and temporal heterogeneity in nutrient availability and even in plant demand throughout the growing season. In this sense, long-term field monitoring is essential to validate the kinetic responses of nutrient uptake under real vineyard conditions, incorporating cultivar management in different soil types, climates, and even management practices.

This study offers significant insights but points to gaps that can be explored in future research: (i) examining how microbial communities (including nitrifying bacteria, N-fixing bacteria, and mycorrhizae) affect nutrient uptake kinetics, especially nitrogen forms; (ii) applying molecular approaches to characterize transporter regulation, as well as to assess the stability of uptake efficiency throughout the growing season; (iii) evaluating how climatic variables (precipitation and temperature, for example) alter the efficiency of different rootstocks, especially under stress scenarios; (iv) introducing techniques that allow for real-time estimation of nutrient uptake, thereby reducing dependence on complex hydroponic systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and G.B.; methodology, A.T. and G.B.; formal analysis, M.S.d.S.K. and G.N.d.S.; investigation, A.T., G.N.d.S., G.Z.P., B.G.D., J.H., A.V.K., R.S., Á.L.P.B., F.T.N. and M.M.A.; writing—original draft, A.T.; writing—review and editing, A.T., M.S.d.S.K., G.N.d.S., A.V.K., R.S., L.A.T. and G.B.; supervision and project administration, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq—Process: 423772/2018-0; 306146/2023-1) and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul—FAPERGS (Term of grant 21/2551-0002232-9).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all staff and students responsible for the maintenance and data collection from this field trial.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Cataldo, E.; Fucile, M.; Manzi, D.; Masini, C.M.; Doni, S.; Mattii, G.B. Sustainable soil management: Effects of clinoptilolite and organic compost soil application on eco-physiology, quercitin, and hydroxylated, methoxylated anthocyanins on Vitis vinifera. Plants 2023, 12, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visconti, F.; López, R.; Olego, M.Á. The health of vineyard soils: Towards a sustainable viticulture. Horticulture 2024, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlin, J.L.; Austin, R.; Hardy, D.; Howard, A.; Heitman, J.L. Nutrient management effects on wine grape tissue nutrient content. Plants 2022, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassinari, A.; Stefanello, L.O.; Schwalbert, R.A.; Vitto, B.B.; Kulmann, M.S.S.; Santos, J.P.J.; Arruda, W.S.; Schwalbert, R.; Tiecher, T.L.; Ceretta, C.A.; et al. Nitrogen critical level in leaves in ‘Chardonnay’ and ‘Pinot Noir’ grapevines to adequate yield and quality must. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nortjé, G.P.; Laker, M.C. Factors that determine the sorption of mineral elements in soils and their impact on soil and water pollution. Minerals 2021, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Zeng, L.; Qin, W.; Feng, J. Measures for reducing nitrate leaching in orchards: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsala, R.Z.; Capri, E.; Russo, E.; Barazzoni, L.; Peroncini, E.; Crema, M.; De Carrey, R.; Otero, N.; Colla, R.; Calliera, M.; et al. Influence of nitrogen-based fertilization on nitrates occurrence in groundwater of hilly vineyards. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 144512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibacache, A.; Verdugo-Vásquez, N.; Zurita-Silva, A. Rootstock: Scion combinations and nutrient uptake in grapevines. In Fruit Crops; Srivastava, A.K., Hu, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahemi, A.; Dodson Peterson, J.C.; Lund, K.T. Commercial grape rootstocks selections. In Grape Rootstocks and Related Species; Rahemi, A., Peterson, J.C.D., Lund, K.T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 117–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollat, N.; Peccoux, A.; Papura, D.; Esmenjaud, D.; Marguerit, E.; Tandonnet, J.-P.; Bordenave, L.; Cookson, S.J.; Barrieu, F.; Rossdeutsch, L.; et al. Rootstocks as a component of adaptation to environment. In Grapevine in a Changing Environment: A Molecular and Ecophysiological Perspective; Gerós, H., Chaves, M.M., Gil, H.M., Delrot, S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 68–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrotkó, K.; Rozpara, E. Rootstocks and improvement. In Cherries: Botany, Production and Uses; Quero-García, J., Iezzoni, A., Pulawska, J., Lang, G., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017; pp. 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdati, K.; Sarikhani, S.; Arab, M.M.; Leslie, C.A.; Dandekar, A.M.; Aletà, N.; Bielsa, B.; Gradziel, T.M.; Montesinos, Á.; Rubio-Cabetas, M.J.; et al. Advances in rootstock breeding of nut trees: Objectives and strategies. Plants 2021, 10, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, R.; Sampaio, T.L.; Pinkerton, J.; Vasconcelos, M.C. Grapevine Rootstocks for Oregon Vineyards; Oregon State University Extension Service: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2004; EM8882. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.; Sun, T.; Sun, H.; Yue, Q.; Yao, Y. Modifications of ‘Summer Black’ grape berry quality as affected by the different rootstocks. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 210, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbó, M.; Feldberg, N. Agronomic behavior of grape rootstocks resistant to young vine decline in Santa Catarina State, Brazil. BIO Web Conf. 2016, 7, 01017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Agronômico de Campinas (IAC). Cultivar IAC 572 ‘Jales’. Available online: https://www.iac.sp.gov.br/cultivares/inicio/Folders/Videira/IAC572(Jales).htm (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Soares, J.M.; Leão, P.C.S. A Vitivinicultura no Semiárido Brasileiro; Embrapa Informação Tecnológica: Brasília, DF, Brazil; Embrapa Semi-Árido: Petrolina, Brazil, 2009; 756p. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J.; Boursiquot, J.-M.; This, P.; Chu, K.; Johansson, H.; Meredith, C. Historical genetics: The parentage of Chardonnay, Gamay, and other wine grapes of northeastern France. Science 1999, 285, 1562–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- This, P.; Lacombe, T.; Thomas, M.R. Historical origins and genetic diversity of wine grapes. Trends Genet. 2006, 22, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J.; Meredith, C. The parentage of a classic wine grape, Cabernet Sauvignon. Nat. Genet. 1997, 16, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, R.P.; Pérez-Alfocea, F.; Cookson, S.J.; Ollat, N.; Vitale, A. Physiological and molecular aspects of plant rootstock-scion interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 852518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivran, M.; Sharma, N.; Dubey, A.K.; Singh, S.K.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, R.M.; Singh, N.; Singh, R. Scion–rootstock relationship: Molecular mechanism and quality fruit production. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Kummer, M.; Vasconcelos, M.C. Soil nitrogen utilisation for growth and gas exchange by grapevines in response to nitrogen supply and rootstock. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2001, 7, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulmann, M.S.S.; Sete, P.B.; Paula, B.V.; Stefanello, L.O.; Schwalbert, R.; Schwalbert, R.A.; Arruda, W.S.; Sans, G.A.; Parcianello, C.F.; Nicoloso, F.T.; et al. Kinetic parameters govern of the uptake of nitrogen forms in ‘Paulsen’ and ‘Magnolia’ grapevine rootstocks. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 264, 109174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Zhu, L.; Wang, S.; Gu, W.; Huang, D.; Xu, W.; Jiang, A.; Li, S. Nitrate uptake kinetics of grapevine under root restriction. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 111, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, H.E.P.; Olivos, A.; Brown, P.H.; Clemente, J.M.; Bruckner, C.H.; Jifon, J.L. Short-term water stress affecting NO3− absorption by almond plants. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 197, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.R.S.; Santos, L.A. Absorção de nutrientes. In Nutrição Mineral de Plantas, 2nd ed.; Fernandes, M.S., Ed.; Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência do Solo (SBCS): Viçosa, MG, Brazil, 2018; p. 432. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Moll, R.H.; Kamprath, E.J.; Jackson, W.A. Analysis and interpretation of factors which contribute to efficiency of nitrogen utilization. Agron. J. 1982, 74, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Academic Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Rodríguez, V.; Cañas, R.A.; de la Torre, F.N.; Pascual, M.B.; Avila, C.; Cánovas, F.M. Molecular fundamentals of nitrogen uptake and transport in trees. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2489–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Beeckman, T.; Xu, G. Plant nitrogen nutrition: Sensing and signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, B.V.; Ramos, A.C.M.; Telles, L.A.R.; Schneider, R.O.; Kulmann, M.S.S.; Kaminski, J.; Ceretta, C.A.; Melo, G.W.B.; Mayer, N.A.; Antunes, L.E.; et al. Morphological and kinetic parameters of the uptake of nitrogen forms in clonal peach rootstocks. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 239, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, B.V.; Sete, P.B.; Berghetti, Á.L.P.; da Silva, L.O.S.; Jung, J.P.; Nicoloso, F.T.; Mayer, N.A.; Kulmann, M.S.; Brunetto, G. Kinetic parameters related to nitrogen uptake in ‘Okinawa’ peach rootstocks are altered by ‘Chimarrita’ scion Nitrogen uptake in ‘Okinawa’ peach rootstock. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 103, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sete, P.B.; Paula, B.V.; Kulmann, M.S.S.; Rossi, A.; Rozane, D.E.; Hindersmann, J.; Krug, A.V.; Brunetto, G. Kinetic parameters related to nitrogen uptake efficiency of pear trees (Pyrus communis). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalcsits, L.; Lotze, E.; Tagliavini, M.; Hannam, K.D.; Mimmo, T.; Neilsen, D.; Neilsen, G.; Atkinson, D.; Casagrande Biasuz, E.; Borruso, L.; et al. Recent achievements and new research opportunities for optimizing macronutrient availability, acquisition, and distribution for perennial fruit crops. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegatti, R.D.; Souza, A.G.; Bianchi, V.J. Nutritional efficiency for nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in peach rootstocks. J. Plant Nutr. 2020, 44, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serio, F.; Miglietta, P.P.; Lamastra, L.; Ficocelli, S.; Intini, F.; De Leo, F.; De Donno, A. Groundwater nitrate contamination and agricultural land use: A grey water footprint perspective in Southern Apulia Region (Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1425–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Yang, J.L.; Zhao, X.R.; Yang, S.H.; Mulder, J.; Dörsch, P.; Zhang, G.L. Nitrate leaching and N accumulation in a typical subtropical red soil with N fertilization. Geoderma 2022, 407, 115559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.; Wang, P.; Zhao, J.; Ding, M.; Zhang, H.; Nie, M.; Huang, G. Sources and migration similarly determine nitrate concentrations: Integrating isotopic, landscape, and biological approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 852, 158216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.; Zhang, T.; Yao, S.; Guo, Y. Effects of households’ fertilization knowledge and technologies on over-fertilization: A case study of grape growers in Shaanxi, China. Land 2020, 9321, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Yue, F.; Cui, Y.; Chen, C. The role of fine management techniques in relation to agricultural pollution and farmer income: The case of the fruit industry. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 034001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The Water-Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soil; California Agricultural Experiment Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1950; Circular 347. [Google Scholar]

- Barłóg, P.; Grzebisz, W.; Łukowiak, R. Fertilizers and fertilization strategies mitigating soil factors constraining efficiency of nitrogen in plant production. Plants 2022, 11, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paula, B.V.; Rozane, D.E.; Brunetto, G.; Marques, A.C.R.; Santos, E.; Melo, G.W.B. Influx 1.0: Software Para Estimar Parâmetros Cinéticos de Absorção de Nutrientes Com Base na Equação de Michaelis–Menten; SSRN: 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4949719 (accessed on 10 September 2024). (In Portuguese).

- von Caemmerer, S.; Farquhar, G.D. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta 1981, 153, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G.N. Chlorophyll fluorescence a practical guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscox, J.D.; Israelstam, G.F. A method for the extraction of chlorophyll from leaf tissue without maceration. Can. J. Bot. 1979, 57, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wei, G.; Li, J.; Qian, Q.; Yu, J. Silicon alleviates salt stress and increases antioxidant enzymes activity in leaves of salt-stressed cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Plant Sci. 2004, 167, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraik, A.E.; Souza, F.S.; Fatibello-Filho, O.; Leite, O.D. Desenvolvimento de um spot test para o monitoramento da atividade da peroxidase em um procedimento de purificação. Quim. Nova 2008, 31, 731–734. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S. Purification and quantitative relationship with water-soluble protein in seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 1977, 48, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loreto, F.; Velikova, V. Isoprene produced by leaves protects the photosynthetic apparatus against ozone damage, quenches ozone products, and reduces lipid peroxidation of cellular membranes. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Moshaty, F.I.B.; Pike, S.M.; Novacky, A.J.; Sehgal, O.P. Lipid peroxidation and superoxide production in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) leaves infected with tobacco ringspot virus or southern bean mosaic virus. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1993, 43, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, E.G. Nitrate reductase assay in intact plant tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1971, 43, 1274–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.B. The determination of nitrogen by the Kjeldahl method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1904, 26, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreves, K.A.; Otchere, O.; Ferland, D.; Farzadfar, S.; Williams, S.; Arcand, M.M. Nitrogen use efficiency definitions of today and tomorrow. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 637108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danjon, F.; Pot, D.; Raffin, A.; Courdier, F. Genetics of root architecture in 1- year-old Pinus pinaster measured with the WinRHIZO image analysis system: Preliminary results. In The Supporting Roots of Trees and Woody Plants: Form, Function and Physiology; Springer: Dordrecht, Holanda, 2000; pp. 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.A. Estimativa dos parâmetros cinéticos em Km e Vmax por uma aproximação gráfico-matemática. Rev. Ceres 1985, 32, 79–84. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, N.E.; Barber, S.A. Differences among genotypes of corn in the kinetics of P uptake. Agron. J. 1978, 70, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=factoextra (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A. Role of nitrogen (N) in plant growth, photosynthesis pigments, and N use efficiency: A review. Agrisost 2022, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.P.; Bárdos, G.; Merkt, N.; Zörb, C. Expression of key enzymes for nitrogen assimilation in grapevine rootstock in response to N—Form and timing. J. Plant Nutr. Soil. Sci. 2020, 183, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Scandellari, F.; Bonora, E.; Tagliavini, M. Nutrient release during decomposition of leaf litter in a peach (Prunus persica L.) orchard. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2010, 87, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, G.; Ceretta, C.A.; Melo, G.W.B.; Girotto, E.; Ferreira, P.A.A.; Lourenzi, C.R.; Couto, R.R.; Tassinaria, A.; Hammerschmitt, R.K.; Silva, L.O.S.; et al. Contribution of nitrogen from urea applied at different rates and times on grapevine nutrition. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 207, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossdeutsch, L.; Schreiner, R.P.; Skinkis, P.A.; Deluc, L. Nitrate uptake and transport properties of two grapevine rootstocks with varying vigor. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 608813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, K.P.; Field, S.K.; Rogiers, S.Y.; Nielsen, S.; Guisard, Y.; Holzapfel, B.P. Rootstocks alter the seasonal dynamics and vertical distribution of new root growth of Vitis vinifera cv. Shiraz grapevines. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuneo, I.F.; Barrios-Masias, F.; Knipfer, T.; Uretsky, J.; Reyes, C.; Lenain, P.; Brodersen, C.R.; Walker, M.A.; McElrone, A.J. Differences in grapevine rootstock sensitivity and recovery from drought are linked to fine root cortical lacunae and root tip function. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulmann, M.S.S.; Stefanello, L.O.; Tassinari, A.; Arruda, W.S.; Vitto, B.B.; Souza, R.O.S.; Ceretta, C.A.; Simão, D.G.; Tiecher, T.L.; Brunetto, G. Dynamics of spatial and temporal growth of the root system of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) under nitrogen levels in sandy soil in subtropical climate. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 303, 111223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, R.O.; Furtini Neto, A.E.; Deccetti, S.F.C.; Viana, C.S. Root morphology and nutrient uptake kinetics by australian Cedar clones. Rev. Caatinga 2016, 29, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somkuwar, R.G.; Bhange, M.A.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Ramteke, S.D. Interaction effect of rootstocks on gas exchange parameters, biochemical changes and nutrient status) in Sauvignon Blanc winegrapes. J. Adv. Agric. 2014, 3, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovis, V.L.; Erismann, N.M.; Machado, E.C.; Quaggio, J.A.; Boaretto, R.M.; Mattos Júnior, D. Biomass partitioning and photosynthesis in the quest for nitrogen—Use efficiency for citrus tree species. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannea, F.B.; Padiglia, A. Antioxidant defense systems in plants: Mechanisms, regulation, and biotechnological strategies for enhanced oxidative stress tolerance. Life 2025, 15, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: Antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M. Reactive oxygen species (ROS): Plant perspectives on oxidative signalling and biotic stress response. Discov. Plants 2025, 2, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.N.P.; Sung, J. Light spectral-ranged specific metabolisms of plant pigments. Metabolites 2025, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, V.M.T.S.; Andrade, A.G.; Souza, E.S.; França, J.G.E.; Maciel, G.A. Atividade enzimática em variedades de cana-de-açúcar cultivadas in vitro sob diferentes níveis de nitrogênio. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2004, 39, 1087–1093. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.P.; Bonfim, R.A.A.D.; Silva, L.D.D.; Souza, M.O.; Soares, P.P.D.S.; Sá, M.C.; Cairo, P.A.R. Nitrate reductase activity in Eucalyptus urophylla and Khaya senegalensis seedlings: Optimization of the in vivo assay. J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugraheni, W.; Solichatu, S.; Etikawati, N. Variations in growth, proline content, and nitrate reductase activity of Canna edulis at different water availability. Cell. Biol. Dev. 2019, 3, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A.; Martí, M.C.; Sevilla, F. Oxidative post-translational modifications of plant antioxidant systems under environmental stress. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, A.D.M.; Britto, D.T.; Kaiser, B.N.; Kinghorn, J.R.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Kumar, A.; Okamoto, M.; Rawat, S.; Siddiqi, M.Y.; Unkles, S.E.; et al. The regulation of nitrate and ammonium transport systems in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratore, C.; Espen, L.; Prinsi, B. Nitrogen uptake in plants: The plasma membrane root transport systems from a physiological and proteomic perspective. Plants 2021, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Huang, D. The utilization and roles of nitrogen in plants. Forests 2024, 15, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandio, M.V.L. Expressão gênica de transportadores de nitrato e amônio, proteína reguladora NAR e bombas de prótons em arroz (Oryza Sativa L.) e seus efeitos na eficiência de absorção de nitrogênio. Master’s Thesis, Na Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Seropédica, Brazil, 2011; 69p. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Chen, W.W.; Wang, Y.Y.; Huang, Z.R.; Ye, X.; Chen, L.S.; Yang, L.T. Effects of phosphorus deficiency on the absorption of mineral nutrients, photosynthetic system performance and antioxidant metabolism in Citrus grandis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwalbert, R.; Milanesi, G.D.; Stefanello, L.; Moura-Bueno, J.M.; Drescher, G.L.; Marques, A.C.R.; Kulmann, M.S.S.; Berghetti, A.P.; Tarouco, C.P.; Machado, L.C.; et al. How do native grasses from South America handle zinc excess in the soil? A physiological approach. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2022, 195, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).