Abstract

Tea plantations are a hot-spot source of nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions in the agricultural system. Using nitrification inhibitors (NIs) is a promising way to mitigate agricultural N2O emissions and has been widely tested in many croplands. However, the efficiency of different NIs and whether there are soil-specific effects are still unclear in tea plantations with typical acidic soil conditions. This study evaluated the effects of three widely used NIs, i.e., dicyandiamide (DCD), 3,4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate (DMPP), and 2-chloro-6-(trichloromethyl) pyridine (Nitrapyrin), through a lab incubation trial, on the nitrification suppression, N2O emissions, and ammonia-oxidizing microbial communities in two tea plantation soils with contrasting physicochemical properties (pH and texture). During the 50-day incubation, the soil with a higher pH and coarse texture (TA) exhibited a four-times-higher apparent nitrification ratio (ANR) than the more acidic and clay soil (HZ). Nitrification inhibitor addition resulted in about a 60% and 80% reduction in the ANR in HZ and TA soils, respectively. During the entire incubation, ammonium sulfate (N) addition without NIs emitted N2O at 64.1 ± 1.2 and 61.5 ± 0.4 μg N kg−1 (mean ± standard deviation, and the same in the following text) in the HZ and TA soils, respectively. Compared with the N alone, the N2O mitigation efficiency of DCD, DMPP, and Nitrapyrin was 38.3% ± 0.4% (standard deviation), 33.8% ± 0.99%, and 36.5% ± 0.59% in the HZ soil and 94.1% ± 0.39%, 52.8% ± 1.05%, and 95.6% ± 0.65% in the TA soil, respectively. Nitrapyrin more effectively suppressed both ammonia-oxidizing archaeal (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacterial (AOB) abundance, particularly in the acidic soil (HZ), where ammonia-oxidizing archaea dominate nitrification. These results revealed the pivotal role of soil properties in controlling NI efficiency and highlighted Nitrapyrin as a potential superior nitrification inhibitor for N2O mitigation under the tested conditions in this study.

1. Introduction

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is one of the key greenhouse gases (GHGs), contributing to global climate change. It has a 298-times-greater global warming potential (GWP) than carbon dioxide (CO2) over 100 years [1]. Furthermore, N2O is also the dominant ozone-depleting substance [2]. Soil N2O emissions in agriculture contributed to about 60% of the total anthropogenic N2O emissions [3]. More N2O emissions will be emitted as the global population increases in the future [4]. Thus, finding effective mitigation strategies is still urgent and necessary in scientific research and policy making for agriculture.

Tea is the most consumed beverage after water and is widely cultivated in subtropical and tropical regions of Asia and Africa [5]. Despite a decline since the 1990s due to environmental concerns, the average annual nitrogen input in tea plantations remains exceptionally high, averaging 491 kg ha−1 in China [6] and 600 kg ha−1 in Japan [7]. These rates are 2.6 to 5.0 times those of cereal crops like rice, maize, and wheat [8]. Such intensive fertilization not only provides ample nutrients but also accelerates soil acidification [9], a condition known to favor N2O production [10,11]. According to a systematic analysis in 2020 by Wang et al. [8], global tea plantations emit an estimated 57–84 Gg N2O annually, accounting for 1.5–12.7% of the direct cropland N2O emissions. These emissions contribute to global warming and reduce economic benefits by lowering nitrogen use efficiency (NUE). Therefore, mitigating N2O losses in tea agroecosystems is essential for sustainable management.

The application of nitrification inhibitors (NIs) has been proposed as a promising way to reduce soil N2O emissions in agriculture [12]. The most widely used NIs are dicyandiamide (DCD), 3,4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate (DMPP), and 2-chloro-6-(trichloromethyl) pyridine (Nitrapyrin) in the practice of improving nitrogen use efficiency [13,14]. However, the above three NIs have differences in longevity, mobility in soil, and efficiency in retarding the activity of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms, due to their diverse chemical structures [15]. So far, most studies about NIs have been widely conducted in cereals and grasslands with semi-neutral or basic soil under a temperate climate; the efficiency of different NIs in tea plantations is still controversial [16,17]. The efficiency of NIs in reducing N2O emission is also strongly dependent on soil conditions, e.g., soil texture and pH [18]. Tea plantation soil has exhibited a lower mitigation efficiency of DMPP than cropland soil, and its lower soil pH decreased the abundance and activity of AOB, the functional target of DMPP [19]. Furthermore, the shift in the AOA and AOB community structure after long-term tea plantation may alter NI effectiveness [20]. Therefore, testing different NIs across soils with contrasting properties is essential for evaluating their robustness.

In the present study, we conducted a controlled lab trial to evaluate the effects of three widely used nitrification inhibitors, DCD, DMPP, and Nitrapyrin, on N2O emissions, nitrogen dynamics, and ammonia-oxidizing microbial communities in two contrasting tea plantation soils. The tested tea garden soils were collected from Hangzhou in Zhejiang (HZ) and Taian in Shandong (TA) as representative samples of China’s two primary tea plantation zones—the Jiangnan (south of Yangtze) and Jiangbei (north of Yangtze) tea plantation zones. The two soils typically represent the characteristic differences in soil pH and texture between southern and northern Chinese soils due to their pedogenic processes. We hypothesized that (1) NI performance would be higher in soils with a higher pH and loose texture, and (2) the three NIs would have a similar efficiency in identical soil due to the optimal application concentration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

Soil samples were collected from tea plantations in Hangzhou (HZ) and Tai’an (TA), which belong to the Zhejiang and Shandong provinces, respectively, in China in 2019. Both have been planted with tea trees (Camellia sinensis) for green tea production.

The sampling site of HZ (120°05′ E, 30°10′ N) is located in a subtropical zone, has a monsoon climate. The soil at the sampling site is classified as Ultisol, developed from the parent material of a Quaternary eolian red deposit. The sampling site of TA (117°04′ E, 36°12′ N) is located in a temperate zone and also has a monsoon climate, but is drier and cooler than HZ. The soil in the site of TA is classified as Luvisols, developed from a parent material of granite weathering residual. More comparisons of soil properties are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physio-chemical properties of the tested tea plantation soils for the incubation.

2.2. Soil Collection and Analysis

Before soil sampling, litter on the surface was removed. For each soil, composite soil samples (0–20 cm depth) were collected by a soil auger from multiple points across the tea plantation field. Fresh soil samples were transported on ice to the laboratory, where any visible stones, roots, and plant debris were manually removed. After that, soil samples were passed through a 2 mm sieve and stored at 4 °C for subsequent analyses and microcosm incubation.

Soil particle size distribution was determined using a laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000, Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). Soil total C and N contents were determined using the elemental analyzer (Vario Macro Cube, Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany). Soil available P and K were extracted using Mehlich-3 reagent and determined using the Inductive Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectrometer (iCAP 7400, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Soil pH was measured in a distilled water extraction (1/2.5 in w/v) using a soil pH electrode (Orion 3 Star, Thermo, USA). Soil NH4+-N and NO3−-N in the fresh soil samples were extracted with 1 M KCl (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) with a soil:solution by 1:10 (w/v) and then determined using the Automatic Chemistry Analyzer (SmartChem 140, AMS Alliance, Frépillon, France).

2.3. Experiment Design

The lab incubation included five treatments: background without any nitrogen or nitrification inhibitor (CK), chemical nitrogen addition alone (N), N plus DCD (10% of added N, DCD, Sanpu Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), N plus DMPP (1% of added N, DMPP, J&K Scientific Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and N plus Nitrapyrin (1% of added N, Nitrapyrin, Aofuto Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). To ensure the substrate saturation for N2O detection in the incubation vial, nitrogen was added at a rate of 500 mg kg−1 (based on dry soil weight) as a (NH4)2SO4 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) solution, corresponding to a field application rate of 1000 kg N ha−1. This amount was about 100% and 20% higher than the average amount in the tea plantation of HZ (467 kg N ha−1) and TA (792 kg N ha−1).

For the incubation, 20 g of soil (fresh soil but based on the oven dry weight) was placed into a glass jar (250 mL in volume, 10 cm in height), and then distilled water was added to reach a soil moisture of 60% maximum water hold capacity (WHC). To stabilize microbial activity following soil disturbance during the sampling, transportation, and storage, all soil samples in the jars were pre-incubated under the aerobic incubation condition at 25 °C with 60% WHC for 2 days in the climate chamber before the treatment. After the pre-incubation, all chemicals were evenly added as a solution to the soil surface and then mixed. During the incubation, the jars were kept open in the climate chamber, and the soil moisture (60% WHC) was maintained through the daily addition of distilled water according to the weight change.

Each treatment was replicated in 28 jars, and 280 jars in total were used simultaneously in this study. To minimize the interference of potentially uneven temperature and humidity in the climate chamber, all jars were put on four layers from the top to the bottom with the same amount and randomly selected from each layer during each sampling.

During the sampling, four fixed jars were selected in each treatment for gas measurement during the whole incubation period. Moreover, four replicates of each treatment were randomly taken out from the climate chamber for soil analysis on days 1, 7, 14, 25, 36, and 50 after the treatment. About 5 g of sampled fresh soil was immediately frozen in the fridge at −20 °C for soil DNA extraction. The left soils were kept at 4 °C for analyses of pH and the concentrations of NH4+-N and NO3−-N.

2.4. Soil Gas Sampling and N2O Concentration Determination

The N2O emission was measured through a semi-static chamber method. Before the experiment, all incubation jars should pass the blank test with pre-evacuated jars. After 2 h, the airtightness was measured according to the status of whether the pressure in the jars significantly increased using an electronical manometer (PG-100-102GP, COPAL ELECTRONICS, Kyoto, Japan).

Gas samples were collected at 1, 3, 6, 10, 15, 21, 28, 35, 45, and 50 days after the treatment. The static closed chamber method was conducted to measure the N2O emission for the advantage of high sensitivity. Before the gas sampling, the jars for gas sampling were sealed with a rubber stopper and silicone gel, and then the air in the sealed jars was evacuated for one minute with a vacuum pump. After that, the ambient air was introduced into the sealed jar to keep all jars at the same start concentration. This evacuation and air replacement was repeated three times to ensure the jar was fully filled with fresh air. During the final air introduction, a 15 mL gas sample was collected into a pre-vacuumed glass vial (738W, Labco, Lampeter, UK) and marked as the initial sample. After 6 h, a 15 mL gas sample was taken using a gas-tight syringe and was marked as the final sample. Before final gas sampling, the air in the sealed jar was evenly mixed using a syringe to ensure homogeneity. After gas sampling, the sealed jar was evacuated, and fresh air was introduced. The rubber stopper was also removed to keep the aerobic condition for further incubation.

The N2O concentration in the collected gas samples was determined using a gas chromatograph (GC 7890B, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The air in the vials was pumped into the GC with a robotic sampler (CA-6, Jiangbo, Beijing, China). The sampled air passed through the GC, with pure N2 (99.999%) as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 30 mL min−1. Different gas components were separated by a stainless-steel column packed with Porapak Q (80/100 mesh) at 55 °C. The N2O signal intensity was determined using the electron capture detector (ECD) at 300 °C. The N2O concentration in the gas sample was linearly scaled to the pre-mixed reference gas with a known N2O concentration. For quality check, the GC was calibrated daily using a multi-point calibration curve with certified standard gases at five different N2O concentrations (350 ppbv, 450 ppbv, 600 ppbv, 750 ppbv, and 900 ppbv). During the sample measurement, a standard (N2O 450 ppbv) was analyzed after every 12 samples to correct for ECD drift.

2.5. Ammonia-Oxidizing Gene Abundance

Soil DNA was extracted from 0.25 g soil samples taken on day 1, 14, and 50 with the soil DNA extraction kit (FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil, MP Bio, Santa Ana, CA, USA) according to the product protocol. The final DNA concentration was determined using a UV–VIS spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the DNA quality was checked through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The extracted DNA samples were stored at −20 °C for further analysis.

The microbial population involved in ammonia-oxidizing was assessed by quantifying the amoA gene copies of AOA, AOB, and TAO100, respectively, which were determined through real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) under specific primers and conditions. The paired primers were Arch-amoA23F/Arch-amoA616R [21], amoA-F/amoA-R [22], and TAO-amoAF/TAO-amoAR [23] for AOA, AOB, and TAO100, respectively. The reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 2.0 μL soil DNA extract, 10.0 μL ready-to-use SYBR Green qPCR Super-Mix UDG with Rox (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), 0.4 μL forward primers (10 μM), 0.4 μL reverse primers (10 μM), and 7.2 μL DNA-free water.

Primer specificity was confirmed through melting curve analysis and gel electrophoresis. Each qPCR was performed in triplicate using a standard curve and a negative control. Plasmids containing the cloned AOA-amoA, AOB-amoA, and TAO100-amoA genes were used for establishing the standard curve. The reaction efficiencies ranged from 97% to 104%, and the R2 values ranged from 0.990 to 0.999 for all three amoA genes.

For convenient comparison, the obtained raw gene copies per reaction were scaled to absolute gene copies per gram of dry soil according to the DNA dilution factor and the dry mass of the soil sample used for DNA extraction.

2.6. Calculation and Statistical Analysis

The N2O emission rate was calculated as follows [15]:

where F was the emission rate (μg N kg−1 d−1), ρ was the N2O-N density (1.25 kg m−3) at the standard condition, δC was the N2O concentration change (ppbv) during the closure period, δt was the seal duration (0.25 day), V was the headspace volume of the incubation jar (0.25 L), W was the dry soil weight (0.02 kg), and T was the incubation temperature (25 °C). The headspace volume of the incubation jars (V) was also corrected for the volume occupied by the incubated soil (~7.5 mL), which was calculated using the dry mass and approximate bulk density.

The cumulative soil N2O emission was calculated through linear integration as follows [15]:

where Cumloss is the cumulative N2O emission (μg N kg−1), Fi is the N2O emission rate of the ith measurement (μg N kg−1 d−1), i represents the sampling sequence from 1 to 10, t represents the sampling date, and the difference in the adjacent sampling dates (ti+1 − ti) represents the sampling interval (days) from 2 to 15.

The apparent nitrification ratio (ANR, %) was calculated as the relative contribution of nitrate in the total mineral N concentration [24]:

The nitrification inhibition efficiency (NIE) was calculated as follows [24]:

where ANRc and ANRi were the net nitrification rate with and without nitrification inhibitor addition, respectively.

To compare the overall treatment effect on dynamic soil characteristics, e.g., pH, chemical N, and amoA gene abundance, the trapezoid averaged values (AVE) were calculated instead of the simple algorithm average as follows [9]:

where AVE was the trapezoid averaged values with the same unit of the raw variable, AUC was the area under the dynamic change curve, which could be calculated according to the trapezoid area rule, and t was the incubation duration (50 days).

The effects of soil, treatment, and sampling date on the soil N2O emission rate and soil properties were tested using three-way ANOVA with interaction effects. In the ANOVA for soil N2O emission rate, soil and treatment were between-group factors, while the sampling date was set as a within-group factor, since the gas samples were taken from the fixed jars during the whole incubation. Alternatively, the sampling date was set as the between-group factor in the ANOVA for soil properties, since soil samples were taken from randomly selected jars.

The effects of soil and treatment on the cumulative N2O emission, as well as the trapezoid averaged values of soil properties, nitrification rate, and nitrification inhibition efficiency, were tested using two-way ANOVA. If the interaction effect was significant, the post hoc comparison between pairwise groups was carried out using the Turkey method for each soil. The effect size was assessed using the index partial eta square (partial η2). The relationships between the trapezoid averaged values of soil properties and cumulative N2O emissions were tested through Pearson correlation analysis. Path modeling with a partial least square algorithm (PLS-PM) was carried out to demonstrate the casual relationships among the observed and latent variables. The overall model performance was assessed with the Goodness-of-Fit index, which accounts for the overall quality at both the measurement and the structural models. In the path model, the strength and direction of the direct effects were represented by the path coefficients between structural variables, while the indirect effects were represented by the sum of the products of all possible path coefficients except the direct effect. All above calculations and statistical analyses were performed on the platform R (version 4.3.0). The contribution package ‘plspm’ (version 0.6.0) was used for path modeling [25].

3. Results

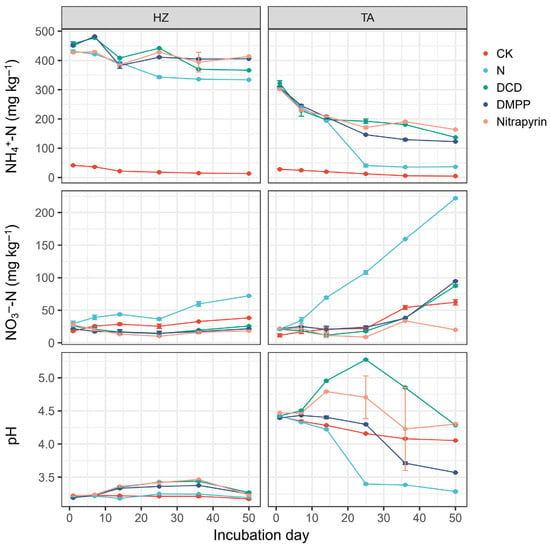

3.1. Soil NH4+-N, NO3−-N, and pH

Both the soil and treatment significantly influenced soil NH4+-N, NO3−-N, and pH changes during the incubation (Table S1). Generally, soil NH4+-N concentrations gradually decreased and remained relatively stable after day 25 (Figure 1). However, TA soil exhibited a more rapid decline than HZ soil. Compared with N alone, the NI addition maintained more NH4+-N throughout the incubation. At the end of the incubation, Nitrapyrin exhibited the highest NH4+-N concentration in both soils, while DCD and DMPP retained less in the HZ and TA soils, respectively. The overall soil NH4+-N concentrations were also significantly affected by the soil and the treatment (Table S2). HZ soil could retain more NH4+-N than the TA soil after the N addition (Figure S1). Three NIs exhibited a significantly higher overall soil NH4+-N concentration than the N alone. However, DMPP showed a lower soil NH4+-N concentration than the other two NIs in the TA soil, which was not found in the HZ soil.

Figure 1.

Changes in soil NH4+-N, NO3—-N, and pH during the incubation. Error bars indicate standard deviation of four replicates.

Generally, the soil NO3−-N concentration increased with time, and its dynamic was also significantly influenced by the soil, treatment, and sampling time (Table S1). Nitrogen addition without NIs (N) maintained more NO3−-N than CK, and the TA soil exhibited a significantly more rapid increase in the soil NO3−-N concentration than the HZ soil (Figure 1). At the end of incubation, the HZ and TA soils accumulated about 75 and 270 mg kg−1 in the treatment with N alone. NI addition significantly retarded the soil NO3−-N accumulation and exhibited lower soil NO3−-N concentrations than N alone. Among the three NIs, Nitrapyrin exhibited the lowest NO3−-N concentration, while DCD and DMPP accumulated the most NO3−-N in the HZ and TA soils, respectively, at the end of incubation. The overall trapezoid averaged NO3−-N concentration was also significantly different for soils and treatments (Table S2), and Nitrapyrin maintained the least NO3−-N among all treatments (Figure S1).

The soil, treatment, and sampling time still significantly influenced the soil pH dynamics (Table S1). In both soils, the soil pH decreased after nitrogen alone, while it firstly increased with NI addition. Soil pH varied between 3.15 and 3.49 in the HZ soil, while it exhibited a much larger variation with a range of 3.25~5.25 in the TA soil (Figure 1). In the TA soil, treatments with NIs showed a hump-shape change, which was not obvious in the HZ soil. Furthermore, the final soil pH values in the TA soil were all lower than the initial value. The overall soil pH value was significantly different among treatments depending on the soil (Table S2). In the HZ soil, the overall pH difference was small, while DCD and N alone showed the highest and lowest overall soil pH in the TA soil (Figure S1).

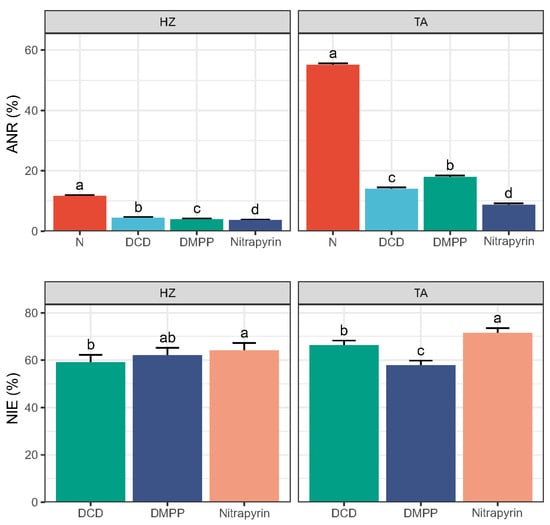

3.2. Apparent Nitrification Ratio and Nitrification Inhibition Efficiency

During the incubation, the apparent nitrification ratio (ANR) increased in both soils, with a more pronounced rise observed in the TA soil (Figure S2). The addition of nitrification inhibitors (NIs) resulted in a lower ANR compared to the N alone treatment, particularly in the TA soil. The overall ANR under the N alone treatment reached 12% in the HZ soil (Figure 2), while three NI additions reduced the overall ANR to 3.6%~4.4%, though the differences among them were not significant. In contrast, in the TA soil, these NIs significantly reduced the overall ANR to 8.8–18%, and Nitrapyrin resulted in largest reduction compared with the other two NIs.

Figure 2.

Overall apparent nitrification ratio (ANR) and inhibition efficiency (NIE). Error bars indicate standard deviation of four replicates, and different letters indicate the significant difference between treatments (p < 0.05).

The nitrification inhibition efficiency (NIE) ranged from 50% to 75% in the HZ soil and from 20% to 88% in the TA soil. The initial NIE in the TA soil was approximately 50% lower than that in the HZ soil (Figure S2). However, the NIE in the TA soil increased rapidly, peaking at around 80% by day 25. The statistical analysis indicated that, while the soil type did not exert a significant simple effect on NIE, the treatment factor had a significant influence (Table S4).

The overall NIE was significantly affected by the interaction between soil type and treatment (Table S4). In both soils, Nitrapyrin showed the significantly highest overall NIE (64% in HZ and 71% in TA), whereas DCD and DMPP exhibited the lowest NIE by 59% in the HZ soil and 58% in the TA soil, respectively (Figure 2).

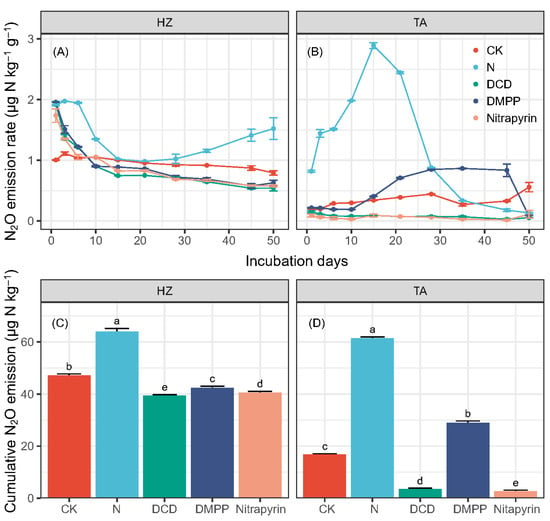

3.3. Soil N2O Emission

The soil N2O emission change was significantly influenced by the soil and treatment, with interactions (Table S5). In the HZ soil, CK showed a stable and low N2O emission rate, ranging between 0.65 and 1.13 μg N kg−1 d−1 (Figure 3A). Nitrogen addition alone showed higher emission rates than CK in the first week but decreased and became lower than CK after day 10, except in the treatment with N alone. The N2O emission rate in the treatment with N alone showed an increase after day 20, while all NI treatments maintained a decreasing trend.

Figure 3.

Soil N2O flux (A,B) and cumulative N2O emissions (C,D) in different soils. Error bars indicate standard deviation of four replicates, and different letters indicate the significant difference between treatments (p < 0.05).

In the TA soil, N2O emission rates were generally lower than those in the HZ soil, except for the N alone (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the emission rate in N alone firstly kept increasing to a peak of 2.8 μg N kg−1 d−1 until day 15 and then decreased. Compared with the treatment with N alone, NI additions exhibited lower N2O emission rates and a decreasing pattern at the beginning. DMPP showed higher N2O emission rates than the other two NIs. Furthermore, the emission rate in DMPP began to increase on day 10 and reached a peak of 0.8 μg N kg−1 d−1 on day 35. Throughout the whole incubation, the N2O emission rates in treatments DCD and Nitrapyrin were relative stable, but lower than 0.2 μg N kg−1 d−1.

The cumulative N2O emission was largely affected by the soil and treatment, with a significant interaction effect (Table S6). In the HZ soil, the background cumulative N2O emissions (CK) were 47.2 μg N kg−1, while the N addition alone (N) resulted in a 36% increase ober CK to 64.1 μg N kg−1 (Figure 3C). Compared to N alone, DCD showed the largest reduction, by 38%, but there was no big difference between DCD and DMPP or Nitrapyrin, which also showed about a 35% reduction.

The cumulative N2O emissions in the TA soil were lower than those in the HZ soil (Figure 3D). The highest cumulative N2O emission in the TA soil was also observed in the treatment with N alone, at 61.5 μg N kg−1, which was 266% more than that of CK, which emitted 16.8 μg N kg−1 during the 50-day incubation. Compared with N alone, NI additions exhibited a significant reduction, by 53–95%, and DCD and Nitrapyrin showed a larger reduction than DMPP.

3.4. Abundances of amoA Genes

During the incubation, the change in the soil AOA, AOB, and TAO100 abundance was significantly influenced by the soil, treatment, and incubation time (Table S7). Both soils showed similar initial AOA amoA gene abundances, but exhibited a descending trend in the HZ soil and a hump-shape in the TA soil, respectively (Figure S3). Compared with N alone, DMPP and DCD exhibited significantly lower AOA abundances in the HZ and TA soils, respectively. At the end of incubation on day 50, the AOA abundance was significantly lower in all NIs in HZ soil, but only significantly lower in DMPP in the TA soil (Figure S3). The initial gene abundances of AOB amoA were much lower than those of AOA in both soils. All treatments exhibited an increasing AOB abundance in the HZ soil, while there was no significant difference in the TA soil, except with N alone (Figure S3). Compared with N alone, NI additions exhibited a decrease in AOB abundance, which was larger in the TA soil. At the end of incubation, DMPP showed the significantly lowest AOB amoA gene abundance among NIs in the HZ soil. The initial TAO100 amoA gene abundance did not show any difference among treatments in both soils on day 1 (Figure S3). Meanwhile, at the end of incubation, nitrogen alone (N) exhibited a significantly higher TAO100 abundance than CK in HZ soil. Compared with N alone, only Nitrapyrin among the three NIs significantly reduced the TAO100 abundance at the end of incubation.

The overall AOA, AOB, and TAO100 gene abundance was significantly affected by the interactions between soils and treatments according to the results of the two-way ANOVA (Table S8). In the HZ soil, the N treatment showed the highest overall AOA abundance, which was significantly reduced by Nitrapyrin, and further significantly reduced by both DCD and DMPP. A different pattern was found in the TA soil, where the N and DMPP treatments maintained similarly high AOA abundances, both significantly exceeding the statistically indistinguishable levels in DCD and Nitrapyrin (Figure 4). The response of the average AOB abundance to the NIs also differed between soils. In the HZ soil, while the N treatment yielded the highest AOB, Nitrapyrin and DCD showed an intermediate and comparable suppressive effect, both being significantly higher than DMPP. In the TA soil, the N alone treatment also resulted in a significantly higher AOB abundance than all NIs, which did not differ significantly from each other. The two-way ANOVA also confirmed that the overall TAO100 amoA gene abundance was significantly affected by the interaction of soil and treatment (Table S8). Its abundance in the HZ soil was resilient to all treatments, showing no significant differences. In the TA soil, a significant suppression was evident under DCD and Nitrapyrin, as abundances in the N and DMPP treatments were comparable and significantly larger.

Figure 4.

Overall amoA gene abundance of AOA, AOB, and TAO100. Error bars indicate standard deviation of four replicates, and different letters indicate the significant difference between treatments (p < 0.05).

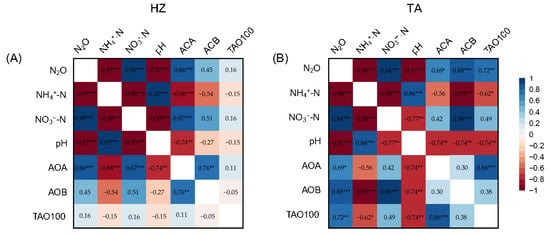

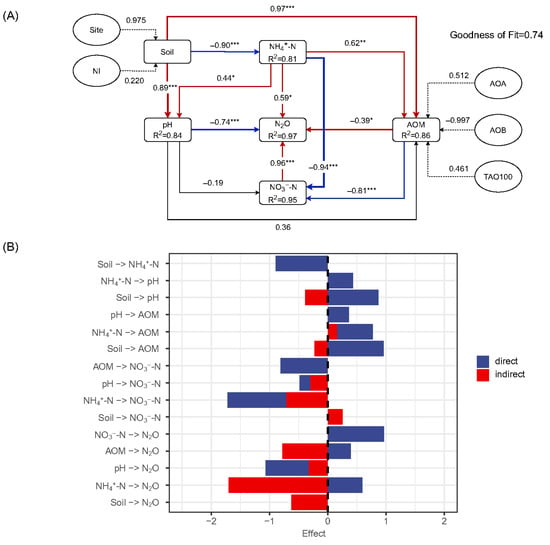

3.5. Structural Path Model

The N2O emission rates were significantly correlated with the soil NH4+-N, pH, and amoA gene abundance of AOA, AOB, and TAO100 (Figure S4). The cumulative N2O emission showed significantly positive correlations with soil NO3−-N, but a negative correlation with soil NH4+-N and pH. Furthermore, the cumulative N2O emission was significantly correlated with only AOA abundance in the HZ soil (Figure 5A), but with all three amoA gene abundances in the TA soil (Figure 5B). The soil NH4+-N exhibited a significantly negative correlation with soil NO3−-N, but a positive correlation with pH in both soils. The soil NO3−-N had a significantly negative correlation with AOA in the HZ soil, but a positive correlation with AOB expression in the TA soil. The soil pH exhibited a positive correlation with the amoA gene abundance, only with AOA in the HZ soil but with all three in the TA soil. Among the three amoA gene abundances, AOA only exhibited a positive correlation with AOB in the HZ soil, and only had positive correlation with TAO100 in the TA soil. There was no significant correlation between AOB and TAO100 in both soils.

Figure 5.

Correlation between cumulative N2O emission and soil properties in the HZ (A) and TA (B) soil. Values in the heatmap are correlation coefficients and *, **, and *** represent p values less than 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

The partial least squares path model (PLS-PM) integrated environmental, chemical, and microbial drivers for N2O emissions. The inner (structural) model explained more than 80% of the variance for each inner variable, and four inner variables accounted for 97% of the variance of the cumulative N2O emissions (Figure 6A). The overall model prediction power (GoF) was 0.74. Soil NH4+-N and NO3−-N exhibited significantly direct relationships with N2O emissions, while pH and ammonia-oxidizing gene abundance (AOM) exhibited negative path coefficients. Both soil and NH4+-N showed positive path coefficients with AOM, while pH did not. The factor for soil had a negative path relationship with NH4+-N, which was also negatively correlated with NO3−-N. In the outer model, the sampling site (Site) contributed more than nitrification inhibitor (NI) to the factor for soil, while AOB abundance contributed most to the variation in the factor for AOB.

Figure 6.

The relationship between site, NI, soil pH, NH4+-N, NO3−-N, and AOM. (A) The path model outputs. The numbers on the arrows are standardized path coefficients; the red or blue lines indicated a positive or negative effect. Path coefficients and coefficients of determination (R2) were calculated using 999 bootstraps. R2 values indicated the variance explained by the block. The Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) statistic is a measure of the overall prediction performance. GoF > 0.7 represents an acceptable ‘good’ fit. (B) The standardized path coefficients of the direct, indirect, and total effects on cumulative N2O emissions. *, **, and *** represent p values less than 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001, respectively.

Among the factors influencing N2O emission, soil NH4+-N and pH are the two main inner variables influencing the total effect (Figure 6B). In the direct pathways, soil NO3−-N and pH exhibited the greatest positive and negative effects, respectively. Meanwhile, in the indirect effects, all inner variables contributed negatively to the N2O emission, and NH4+-N and AOM were the two largest contributors. AOM showed significant positively direct, but negatively indirect, effects on the N2O emissions. Although the treatment of the soil (combination of site and NIs) contributed the smallest effect to N2O emissions, it showed the strongest total effect on the AOM, which was mostly from the direct pathway. Moreover, soil NH4+-N contributed a secondary impact to AOM, while pH showed the weakest influence. Most NO3−-N variations were directly from NH4+-N, which also showed a significant indirect effect mediated via AOM.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Soil Properties on Nitrification Inhibition Efficiency

The dynamics of soil NH4+ and NO3− were strongly affected by the soils and nitrification inhibitors (Table S1). Despite the addition of nitrification inhibitors, the TA soil showed a faster decline of soil NH4+ concentration (Figure 1) and a higher apparent nitrification ratio than the HZ soil (Figure 2). These results indicated the higher baseline nitrification activity of TA soil, which means more favorable conditions for nitrification organisms in the TA soil.

The dependence of nitrification activity on soil properties, e.g., pH, organic carbon, and texture, has also been reported in previous studies [26,27,28]. The higher pH and porous texture in the TA soil may be the pivotal factors contributing to the difference in the apparent nitrification ratio, since nitrifier activity is strongly constrained under acidic conditions, and the relatively higher pH in the TA soil may have a faster nitrification rate [29,30]. From a physiological perspective, the higher pH and more porous texture in the TA soil can create favorable conditions for supplying more substates for nitrification, since there is a pH-dependent equilibrium between the ammonia and ammonium [31], and the higher porosity indicates more O2 supply for aerobic nitrification.

All three NIs showed significant effects in suppressing NH4+ depletion and NO3− accumulation, but their performance was significantly different between soils (Figure 1). Nitrapyrin exhibited the lowest apparent nitrification ratio and strongest inhibition efficiency in both soils (Figure 2). However, DCD and DMPP showed a soil-specific effect in the nitrification inhibition efficiency, with a significant difference in TA soils (Figure 2). To clarify these soil-specific responses, the inherent properties of the HZ soil should be considered. The lack of significant differences among the three NIs in the HZ soil can be attributed to its inherently low baseline nitrification activity, which was likely constrained by the low soil pH (Table 1). Beyond pH, the finer texture and higher soil organic carbon (SOC) content in the HZ soil may also further reduce NI efficiency. Specifically, soils with higher clay and organic matter content are known to strongly adsorb organic compounds, potentially reducing the bioavailability of NIs like DCD and DMPP [32]. Furthermore, a higher SOC content can support a more active and diverse microbial community, potentially accelerating the biodegradation of these inhibitors [18,32]. This attenuated effect of NIs in soils with a low intrinsic nitrification potential has also been documented in other studies [33]. The divergent responses in the two soils clearly demonstrate that NI effectiveness is not universal but is strongly controlled by soil properties. Our results implied that factors like clay content and SOC, which influence inhibitor sorption and persistence, are critical determinants of NI performance. This soil-specific interaction highlights the necessity of considering the inherent soil characteristics when selecting and evaluating NIs for practical applications.

4.2. Efficiency of N2O Mitigation by NIs in Contrasting Soils

Cumulative N2O emissions differed significantly between soils and treatments, reflecting variations in the mitigation potential of NIs (Table S6). Overall, emissions were substantially higher in the HZ soil than in the TA soil (Figure 3), consistent with its higher SOC content and lower pH [34,35,36,37]. Although the TA soil exhibited a faster nitrification and greater NO3− accumulation (Figure 1 and Figure 2), its lower N2O emissions suggest that nitrification-derived N2O was less important here, or that the reduction of N2O to N2 was more efficient. This aligns with studies identifying denitrification as the dominant N2O source in tea soils [38].

The elevated emissions in the acidic HZ soil are likely due to the low pH simultaneously impairing N2O consumption and promoting its production. Acidic conditions strongly inhibit N2O reductase (NosZ), hindering the reduction of N2O to N2 during heterotrophic denitrification [35]. Concurrently, nitrifier denitrification by ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) is often enhanced at a low pH, as they adapt by upregulating nitric oxide reductase (NorB), leading to N2O accumulation [39,40]. Thus, the high N2O emissions from HZ soil likely result from both impaired N2O consumption and a significant contribution from AOB-driven nitrifier denitrification, a pathway whose importance increases as soil pH declines [41].

Chemical N addition alone increased N2O emissions in both soils, but the stimulatory effect was significantly stronger in the TA soil, whereas emissions in the HZ soil increased by only 18% (Figure 3). This disparity reflected contrasting balances between nitrification and denitrification processes, which are strongly influenced by soil texture, aeration, and pH [42,43]. In the TA soil, nitrogen addition provided a more abundant substrate for N2O production, as environmental constraints such as pH and texture were less limiting. Nitrification inhibitors substantially suppressed N2O fluxes in both soils, though their mitigation efficiencies differed. In the HZ soil, the N2O mitigation efficacy of NIs varied between 35% and 38%, with the order of DCD > Nitrapyrin > DMPP. In the TA soil, the order was Nitrapyrin > DCD > DMPP, with DMPP being substantially less effective. Both Nitrapyrin and DCD reduced cumulative emissions by more than 90%, whereas DMPP showed a markedly weaker mitigation (Figure 3). This pattern aligns with the observed soil NO3− dynamics (Figure 1) and overall nitrification inhibition efficiency (Figure 2), where DMPP was less effective at retaining soil NO3− and exhibited a lower inhibition in the TA soil.

The soil-dependent efficacy of nitrification inhibitors (NIs) is closely tied to their ability to regulate substrate availability for microbial N2O production. Nitrapyrin, which consistently and strongly inhibited nitrification, achieved the most stable N2O reduction across both soils, which was also supported in previous studies [12,13]. Its superior performance may be attributed to a higher hydrophobicity and stronger resistance to microbial degradation, particularly under acidic conditions [41,42]. By contrast, DMPP showed a lower efficiency than DCD in the TA soil, a result that appears inconsistent with reports of DMPP’s typically longer persistence and stronger efficacy [12,43]. This discrepancy may be due to the specific conditions of the TA soil requiring a higher functional concentration of DMPP for effective inhibition. Key soil factors such as low pH and a nitrifier community potentially dominated by ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) can reduce DMPP’s bioavailability or require a higher threshold for inhibition, as DMPP primarily targets AOB [19]. A previous study noted that DMPP’s effective concentration can be 2–5 times higher than other NIs in some soils [44], implying that our DMPP dose may be insufficient. The observed higher abundance of ammonia oxidizers under DMPP treatment (Figure 4) confirmed that the inhibition was incomplete.

4.3. Ammonia-Oxidizing Microbes Driving N2O Emission

The abundance of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOMs) provided further insight into the mechanisms underlying N2O mitigation by nitrification inhibitors (NIs). In contrast to studies conducted in neutral croplands, the AOM community in these acidic tea soils was dominated by AOA and TAO100, whereas AOB abundance remained relatively low (Figure 4). This pattern aligns with previous reports indicating the numerical dominance of AOA and TAO100 under strongly acidic conditions, where AOB are often suppressed [45,46]. Nitrogen fertilization (N) stimulated AOB in both soils but exerted divergent effects on AOA. It significantly increased AOA abundance in the HZ soil but decreased it in the TA soil. This may reflect the more favorable pH in the TA soil, enabling AOB to temporarily outcompete AOA following the initial NH4+ pulse, as supported by the marked increase in AOB after N addition in this soil (Figure S3).

The application of NIs further modulated the composition of the AOM community. In the HZ soil, all three inhibitors effectively suppressed AOA abundance relative to the N only treatment, whereas, in the TA soil, their primary effect was observed on AOB (Figure 4). This suggested a potential shift in the dominant ammonia-oxidizing populations between soils, which may influence NI efficacy. In the HZ soil, the reduction in AOA abundance under NI treatments was consistent with the observed decline in cumulative N2O emissions (Figure 5), implying a possible link between AOA activity and N2O production in this acidic soil. By contrast, in the TA soil, AOA abundance was less responsive to NIs, particularly DMPP, suggesting a comparatively smaller role of AOA in N2O generation under less acidic conditions. AOB abundance increased over time in the HZ soil (Figure S3) but remained low across most treatments in the TA soil. Interestingly, TAO100 abundance was significantly reduced only by Nitrapyrin in both soils (Figure S3), suggesting a broader inhibitory scope of this compound across different ammonia oxidizer groups.

In the HZ soil, cumulative N2O emissions were only significantly correlated with AOA abundance (Figure 5), underlining the dominant contribution of AOA in the acidic soils. By contrast, in the TA soil, N2O emissions were correlated with all three AOM groups, indicating that multiple AOMs jointly contributed to N2O production (Figure 5). This soil-dependent partitioning of microbial contributions is consistent with previous findings that AOA dominate under acidic or low N conditions, while AOB prevail under a higher N availability and neutral pH [34,45,47]. Considering most tea plantation soils have a pH less than 5.5, AOA would play a pivotal role in N transformation after fertilization [20].

According to the effect size of different factors in the pathway model (Figure 6B), soil NH4+-N (effect = 0.96) and NO3−-N (effect = 0.59) exerted significant positive direct effects on N2O emissions, whereas pH showed a strong negative direct influence (effect = −0.74). In contrast, the ammonia-oxidizing microorganism (AOM) abundance exhibited a dual role, with a positive direct effect (effect = 0.39) on N2O, while a stronger overall negative indirect effect (effect = 0.72) was mediated through substrate consumption and pathway regulation. Nitrification inhibitors (NIs) reduced N2O emissions through multiple pathways, not only by lowering NO3− accumulation, but also by directly suppressing AOM abundance. Notably, the total effect of soil, which integrates site and NI treatments on AOMs, was stronger than its direct effect on N2O, underscoring the importance of microbial mediation as a central mechanism of NI efficacy. Among all drivers, soil NH4+-N and pH were the two dominant variables influencing total N2O emissions, with NH4+-N serving as the primary stimulator of AOM growth, and pH exerting a critical direct suppression on N2O release.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the strongly soil-dependent efficacy of three common nitrification inhibitors (NIs) in mitigating N2O emissions in two typical tea plantation soils. Across both soils, all NIs effectively delayed NH4+ depletion and suppressed NO3− accumulation, yet their performance varied substantially with specific soil properties such as pH, texture, and SOC content. Nitrapyrin consistently provided the strongest and most reliable N2O suppression, whereas DCD and DMPP exhibited a more variable, soil-specific effectiveness.

Mechanistically, NIs reduced N2O emissions not only by regulating substrate availability but also through the direct suppression of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms (AOMs). Our results further indicated that AOA played a dominant role in nitrification in the strongly acidic soil, whereas multiple nitrifier groups contributed under moderately acidic conditions. These findings highlighted the importance of tailoring NI selection to local soil properties and microbial community composition. However, given that these conclusions are derived from a controlled laboratory incubation using only two specific soils, their broader applicability remains to be verified by field validation under realistic climatic conditions in the future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121470/s1. Figure S1. Overall soil NH4+-N, NO3−-N and pH in different treatments. Figure S2. Changes of apparent nitrification ratio (ANR) and inhibition efficiency (NIE) during the incubation. Figure S3. Changes of amoA gene abundance of AOA, AOB and TAO100 during the incubation. Figure S4. Heatmap of the correlation between soil N2O flux and soil properties during the incubation. Table S1. Three-way ANOVA of soil ammonium, nitrate and pH changes during the incubation. Table S2. Two-way ANOVA of overall soil ammonium, nitrate and pH during the incubation. Table S3. Three-way ANOVA of ANR and NIE changes during the incubation. Table S4. Two-way ANOVA of overall soil ANR and NIE. Table S5. Three-way ANOVA of soil N2O flux during the incubation. Table S6. Two-way ANOVA of cumulative soil N2O flux during the incubation. Table S7. Three-way ANOVA of soil AOA, AOB and TAO100 gene abundance during the incubation. Table S8. Two-way ANOVA of overall soil AOA, AOB and TAO100 gene abundance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and K.N.; methodology, S.N. and C.Z.; validation, J.W.; formal analysis, W.H. and S.N.; investigation, S.N. and W.H.; data curation, W.H. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.; writing—review and editing, W.H. and K.N.; supervision, X.Y. and K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the national Key R&D program of China (2022YFF0606800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42407459), Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2021-TRICAAS, 1610212022008), and Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the China (CARS-19).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankara, A.R.; Daniel, J.S.; Portmann, R.W. Nitrous Oxide (N2O): The Dominant Ozone-Depleting Substance Emitted in the 21st Century. Science 2009, 326, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Xu, R.; Canadell, J.G.; Thompson, R.L.; Winiwarter, W.; Suntharalingam, P.; Davidson, E.A.; Ciais, P.; Jackson, R.B.; Janssens-Maenhout, G.; et al. A Comprehensive Quantification of Global Nitrous Oxide Sources and Sinks. Nature 2020, 586, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Bo, Y.; Adalibieke, W.; Winiwarter, W.; Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Sun, Z.; Tian, H.; Smith, P.; Zhou, F. The Global Potential for Mitigating Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Croplands. One Earth 2024, 7, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. World Tea Production and Trade. Current and Future Development; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, K.; Liao, W.; Yi, X.; Niu, S.; Ma, L.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Ruan, J. Fertilization Status and Reduction Potential in Tea Gardens of China. J. Plant Nutr. Fert. 2019, 25, 421–432. [Google Scholar]

- Hirono, Y.; Sano, T.; Eguchi, S. Changes in the Nitrogen Footprint of Green Tea Consumption in Japan from 1965 to 2016. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 44936–44948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Pan, Z.; Wang, R.; Yan, G.; Liu, C.; Su, Y.; Zheng, X.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Tea-Planted Soils as Global Hotspots for N2O Emissions from Croplands. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ni, K.; Shi, Y.; Yi, X.; Zhang, Q.; Fang, L.; Ma, L.; Ruan, J. Effects of Long-Term Nitrogen Application on Soil Acidification and Solution Chemistry of a Tea Plantation in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 252, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaaban, M.; Wu, Y.; Wu, L.; Hu, R.; Younas, A.; Nunez-Delgado, A.; Xu, P.; Sun, Z.; Lin, S.; Xu, X.; et al. The Effects of pH Change through Liming on Soil N2O Emissions. Processes 2020, 8, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, T.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Sheng, X.; Bloszies, S.; et al. Intermediate Soil Acidification Induces Highest Nitrous Oxide Emissions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Yan, X.; Yagi, K. Evaluation of Effectiveness of Enhanced-Efficiency Fertilizers as Mitigation Options for N2O and NO Emissions from Agricultural Soils: Meta-Analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1837–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; He, W.; Smith, W.N.; Drury, C.F.; Jiang, R.; Grant, B.B.; Shi, Y.; Song, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Global Evaluation of Inhibitor Impacts on Ammonia and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Agricultural Soils: A Meta-Analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 5121–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, J.R.; Souza, B.R.; Mazzetto, A.M.; Galdos, M.V.; Chadwick, D.R.; Campbell, E.E.; Jaiswal, D.; Oliveira, J.C.; Monteiro, L.A.; Vianna, M.S.; et al. Mitigation of Nitrous Oxide Emissions in Grazing Systems through Nitrification Inhibitors: A Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2023, 125, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Gao, X. Biological and Chemical Nitrification Inhibitors Exhibited Different Effects on Soil Gross N Nitrification Rate and N2O Production: A 15N Microcosm Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 116162–116174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Fan, Q.; Yu, J.; Ma, Y.; Yin, J.; Liu, R. A Meta-Analysis to Examine Whether Nitrification Inhibitors Work through Selectively Inhibiting Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 962146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.L.; Carlos, F.S.; Barth, G.; Mühling, K.H. Do Tropical Climatic Conditions Reduce the Effectiveness of Nitrification Inhibitors? A Meta-Analysis of Studies Carried out in Brazil. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2023, 125, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Chen, H.; Duan, P.; Zhu, K.; Li, N.; Ma, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, Q. Soil Microbial Communities as Potential Regulators of N2O Sources in Highly Acidic Soils. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 230178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, P.; Bo, X.; Wu, J.; Han, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, K.; Shen, M.; Wang, J.; Zou, J. Soil pH-Dependent Efficacy of DMPP in Mitigating Nitrous Oxide under Different Land Uses. Geoderma 2024, 449, 117018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ni, K.; Shi, Y.; Yi, X.; Ji, L.; Ma, L.; Ruan, J. Heavy Nitrogen Application Increases Soil Nitrification through Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria Rather than Archaea in Acidic Tea (Camellia sinensis L.) Plantation Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pester, M.; Rattei, T.; Flechl, S.; Gröngröft, A.; Richter, A.; Overmann, J.; Reinhold-Hurek, B.; Loy, A.; Wagner, M. amoA-Based Consensus Phylogeny of Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea and Deep Sequencing of amoA Genes from Soils of Four Different Geographic Regions. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotthauwe, J.H.; Witzel, K.P.; Liesack, W. The Ammonia Monooxygenase Structural Gene amoA as a Functional Marker: Molecular Fine-Scale Analysis of Natural Ammonia-Oxidizing Populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 4704–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayatsu, M.; Tago, K.; Uchiyama, I.; Toyoda, A.; Wang, Y.; Shimomura, Y.; Okubo, T.; Kurisu, F.; Hirono, Y.; Nonaka, K.; et al. An Acid-Tolerant Ammonia-Oxidizing γ-Proteobacterium from Soil. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Li, H.; Hu, F.; Zhao, H. Effects of Rewetting on Soil Biota Structure and Nitrogen Mineralization, Nitrification in Air-Dried Red Soi. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2004, 41, 924–930. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, G.; Trinchera, L.; Russolillo, G.; Bertrand, F. Plspm: Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM). 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/plspm/index.html (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Sahrawat, K.L. Factors Affecting Nitrification in Soils. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2008, 39, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Zheng, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, C. Effects of Commonly Used Nitrification Inhibitors—Dicyandiamide (DCD), 3,4-Dimethylpyrazole Phosphate (DMPP), and Nitrapyrin—On Soil Nitrogen Dynamics and Nitrifiers in Three Typical Paddy Soils. Geoderma 2020, 380, 114637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Luo, J.; Lindsey, S.; Shi, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L. Effects of Soil Properties on Urea-N Transformation and Efficacy of Nitrification Inhibitor 3, 4-Dimethypyrazole Phosphate (DMPP). Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 68, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, G.; Leung, P.M.; Daebeler, A.; Guo, J.; Hu, S.; Cook, P.; Nicol, G.W.; Daims, H.; Greening, C. Nitrification in Acidic and Alkaline Environments. Essays Biochem. 2023, 67, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Hou, X.; Zhou, X.; Xin, X.; Wright, A.; Jia, Z. pH Regulates Key Players of Nitrification in Paddy Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 81, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.L.; Lehtovirta-Morley, L.E. Nitrification and beyond: Metabolic Versatility of Ammonia Oxidising Archaea. ISME J. 2023, 17, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; et al. Effect of Soil Organic Matter on Adsorption of Nitrification Inhibitor Nitrapyrin in Black Soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2020, 51, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.L.; Pitann, B.; Banedjschafie, S.; Mühling, K.H. Effectiveness of Three Nitrification Inhibitors on Mitigating Trace Gas Emissions from Different Soil Textures under Surface and Subsurface Drip Irrigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 359, 120969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggs, E.M.; Smales, C.L.; Bateman, E.J. Changing pH Shifts the Microbial Sourceas Well as the Magnitude of N2O Emission from Soil. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuhel, J.; Šimek, M.; Laughlin, R.J.; Bru, D.; Chèneby, D.; Watson, C.J.; Philippot, L. Insights into the Effect of Soil pH on N2O and N2 Emissions and Denitrifier Community Size and Activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1870–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senbayram, M.; Chen, R.; Budai, A.; Bakken, L.; Dittert, K. N2O Emission and the N2O/(N2O + N2) Product Ratio of Denitrification as Controlled by Available Carbon Substrates and Nitrate Concentrations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 147, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Müller, C.; Wang, S. Mechanistic Insights into the Effects of N Fertilizer Application on N2O-Emission Pathways in Acidic Soil of a Tea Plantation. Plant Soil 2015, 389, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Yuan, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, W.; Fan, J.; Liu, D.; Ding, W. Organic Fertilizers Have Divergent Effects on Soil N2O Emissions. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2019, 55, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Peng, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, B.; Ge, S.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L. Pathways and Organisms Involved in Ammonia Oxidation and Nitrous Oxide Emission. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 43, 2213–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Gwak, J.; Rohe, L.; Giesemann, A.; Kim, J.; Well, R.; Madsen, E.; Herbold, C.; Wagner, M.; Rhee, S. Indications for Enzymatic Denitrification to N2O at Low pH in an Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaeon. ISME J. 2019, 13, 2633–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Hirono, Y.; Yanai, Y.; Hattori, S.; Toyoda, S.; Yoshida, N. Isotopomer Analysis of Nitrous Oxide Accumulated in Soil Cultivated with Tea (Camellia sinensis) in Shizuoka, Central Japan. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 77, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Pinzon, P.A.; Prommer, J.; Sedlacek, C.J.; Sandén, T.; Spiegel, H.; Pjevac, P.; Fuchslueger, L.; Giguere, A.T. Inhibition Profile of Three Biological Nitrification Inhibitors and Their Response to Soil pH Modification in Two Contrasting Soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2024, 100, fiae072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiske, A.; Benckiser, G.; Herbert, T.; Ottow, J. Influence of the Nitrification Inhibitor 3,4-Dimethylpyrazole Phosphate (DMPP) in Comparison to Dicyandiamide (DCD) on Nitrous Oxide Emissions, Carbon Dioxide Fluxes and Methane Oxidation during 3 Years of Repeated Application in Field Experiments. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2001, 34, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibuike, G.; Palmada, T.; Saggar, S.; Giltrap, D.; Luo, J. A Comparison of the Threshold Concentrations of DCD, DMPP and Nitrapyrin to Reduce Urinary Nitrogen Nitrification Rates on Pasture Soils—A Laboratory Study. Soil Res. 2022, 61, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.M.; Hu, H.W.; Shen, J.P.; He, J.Z. Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaea Have More Important Role than Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria in Ammonia Oxidation of Strongly Acidic Soils. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayatsu, M.; Katsuyama, C.; Tago, K. Overview of Recent Researches on Nitrifying Microorganisms in Soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 67, 619–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Mo, T.; Zhong, J.; Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Li, Y. Synergistic Benefits of Lime and 3,4-Dimethylpyrazole Phosphate Application to Mitigate the Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Acidic Soils. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 263, 115387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).