1. Introduction

Cucumber, a major crop in the Cucurbitaceae family, is cultivated in over 80 countries [

1] and provides various health benefits, such as water balance regulation, blood pressure and blood glucose maintenance, and skin soothing [

2,

3]. In 2021, cucumber cultivation generated the highest income among greenhouse crops in Korea (KRW 12,456,000 per 1000 m

2). Its cultivation area is 4078 ha, with approximately 75% (3073 ha) under greenhouse conditions [

4]. To sustain such a large cultivation area, a stable supply of high-quality cucumber seedlings is required.

Cucumber fields are often affected by soil-borne diseases, such as

Meloidogyne spp.,

Fusarium spp., and

Rhizoctonia spp., leading to the increased use of disease-resistant rootstocks for grafted cucumber seedlings [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The application of rootstocks resistant to Fusarium wilt disease in cucumber, such as Figleaf gourd (

C. ficifolia), Crookneck pumpkin (

C. moschata), and

C. maxima ×

C. moschata, can enhance cucumber growth and yield [

10]. For example, seedlings of the scion ‘NakwonSeongCheongJang’ grafted on the rootstock ‘Heukjong’ (

C. ficifolia) showed the greatest plant length and leaf area, whereas ‘Sinsedae’ grafted on ‘Heukjong’ exhibited higher chlorophyll content (SPAD) [

7]. Grafted seedlings have improved tolerance to high and low temperatures, enhanced nutrient absorption, improved fruit quality, and increased yield compared with non-grafted seedlings.

Seedling quality can be evaluated through plant length and leaf area measurements. However, non-destructive methods for leaf area measurement, such as blueprinting and tracing, are time-consuming, increasing costs [

11,

12]. Recently, image-based technology using multispectral cameras has been developed to rapidly and accurately measure the plant height and leaf area of grafted cucumber seedlings. Spectral imaging can be used to detect differences in the absorption and reflectance characteristics of plants at different wavelengths, thereby enabling the analysis of diverse physiological conditions [

13]. Unlike standard RGB imaging, multispectral imaging can capture reflectance at different spectral bands, such as those corresponding to visible and near-infrared light, thus facilitating more accurate leaf segmentation and detection of overlap under different lighting conditions. In addition, unlike hyperspectral imaging, which captures continuous wavelength data, multispectral imaging is more rapid and cost-effective, making it better suited to industrial- or nursery-scale applications [

14]. While Jang et al. [

15] reported a high correlation (

R2 ≥ 0.85) between actual measured values and image-based values of plant height and leaf area, they observed errors arising from leaf overlap in plants in plug tray units.

Currently, most seedlings are shipped in plug trays, rather than individually, highlighting the importance of evaluating seedling quality within plug trays [

13]. However, estimating leaf area based on top-down images of plug tray units can lead to discrepancies due to leaf area overlap. Li et al. [

16] applied Azure Kinect to analyze watermelon seedlings and revealed that as the number of true leaves increased, the overlapping leaf area expanded, resulting in measurement errors. Nasution et al. [

17] found that in hydroponically grown cabbage (

Brassica rapa), non-destructive methods for counting leaves became increasingly difficult weeks after transplanting, owing to leaf overlap. In addition, Jang et al. [

15] attributed discrepancies between actual measured values and image-based values in plug tray units (which reached 63%) to leaf area overlap. Leaf area overlap, a major source of error in image-based leaf area estimation, has a greater impact in later growth stages. Additionally, it occurs more frequently in plug tray units than in individual units, suggesting the limitations of accurately estimating leaf area using images of plug tray units.

Several methods have been proposed to address this problem. Tong et al. [

18] developed a non-destructive image processing method that segments leaf area to determine seedling quality for plug seedlings of cucumber, tomato, pepper, and eggplant. This method achieved a seedling quality identification accuracy of over 95% [

18]. Wang et al. [

19] applied image segmentation based on the Chan–Vese model and the Sobel operator, which reduced the error rate of cucumber leaf estimation by 6.54%. Chien and Lin [

20] used side-view images of cabbage and broccoli to correct top-view leaf area image values, resulting in a significant reduction in the relative error from 14.5% and 13.1% to 1.6% and 4.9%, respectively.

Leaf area overlap has a greater impact in later growth stages. If not corrected, it may lead to the underestimation of actual seedling growth, undermining the reliability of image-based growth estimation in automated seedling nurseries.

To address this issue, it is essential to introduce a correction variable that quantitatively reflects the changing growth status of the seedlings over time. In this study, we incorporated days after grafting (DAG) into a regression model to examine the potential for improving the accuracy of image-based estimations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation Site and Varieties

The experiment was conducted at “Solrae” seedling nursery, located in Iksan, Jeonbuk Special Self-Governing Province of South Korea. The rootstock used in the experiment was the Cucurbitaceae rootstock ‘Heukjong’ (Cucurbita ficifolia, Nongwoo Bio Co., Ltd., Suwon, Republic of Korea), and the cucumber scion varieties were ‘Goodmorning Backdadagi’ (GB) (Nongwoo Bio Co., Ltd.), ‘NakwonSeongCheongJang’ (NC) (Wonnong Seeds Co., Ltd., Anseong, Republic of Korea), and ‘Sinsedae’ (SD) (Farmhannong Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea). Each scion was grafted onto the rootstock prior to beginning the experiments.

2.2. Cultivation Management

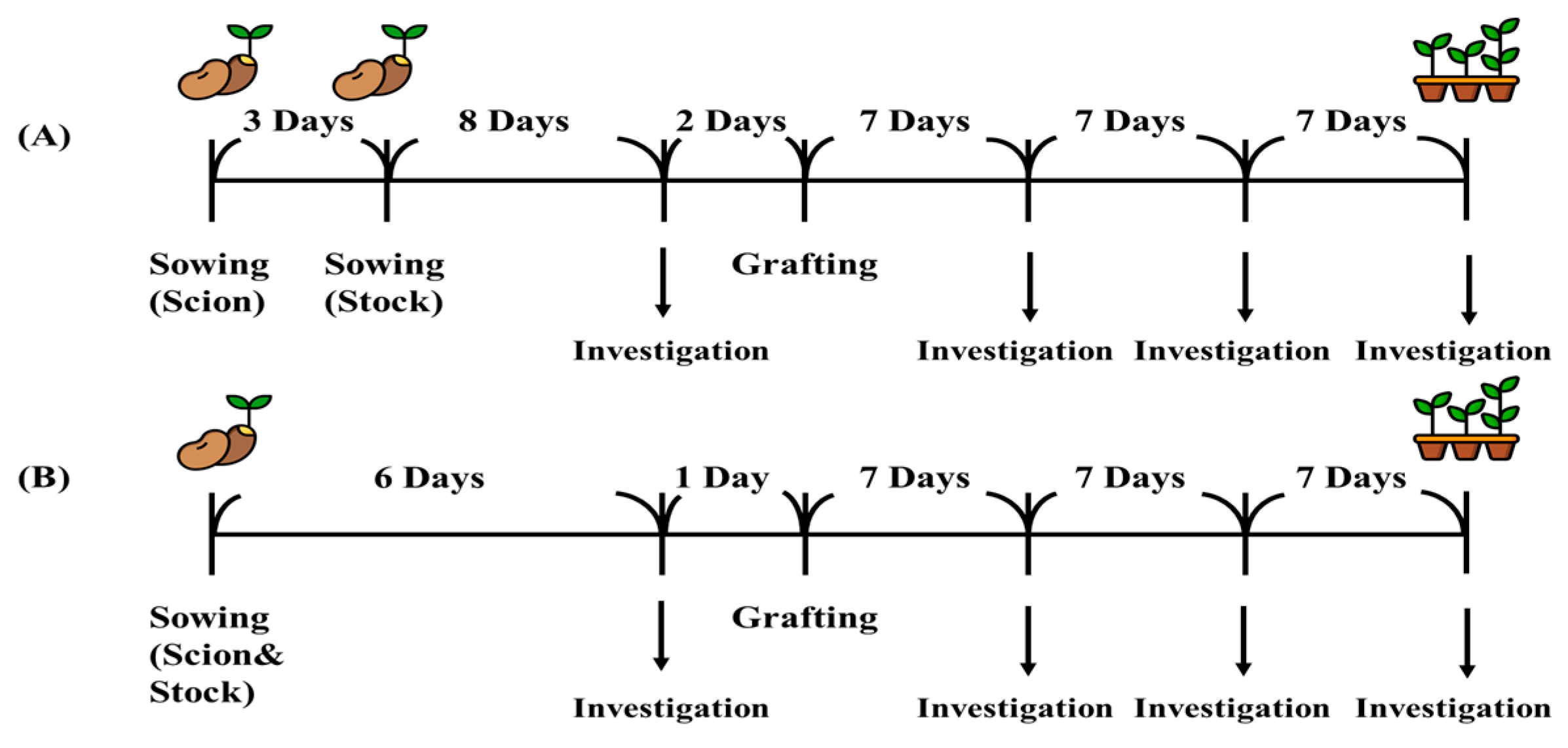

Grafted cucumber seedlings were grown in trays filled with a mixture of peat moss (BM4; Berger Co., Ltd., Saint-Modeste, QC, Canada), horticultural soil (Chologi; Nongwoo Bio Co., Ltd.), and perlite (Newpershine; GFC Co., Ltd., Seoul, Republic of Korea) at a ratio of 50:38:12. The rootstock variety ‘Heukjong’ was sown in 50-cell trays, whereas the scion varieties GB, NC, and SD were sown in 128-cell trays. The experiment was conducted once each in spring and summer, considering seasonal differences in growth. In spring, cucumber scions were sown on 3 March 2023, and rootstocks were sown on 6 March 2023. In summer, both the rootstocks and scions were sown on 21 July 2023. After sowing, the seeds were germinated for 3 days in a germination room at 30 °C with 100% relative humidity. Grafting was performed using the ordinary one-leaf splice grafting method commonly used for Cucurbitaceae crops. In this method, one cotyledon of the scion is cut at a 60° angle, including the growing point of the rootstock, and the cambium of the scion and rootstock are closely joined [

21]. Grafting was conducted on 16 March (spring) and 28 July (summer). After grafting, the seedlings were kept in a rooting room (temperature 30 °C, relative humidity 100%) for 5 days. From sowing to shipment, the spring and summer periods took 34 and 28 days, respectively (

Figure 1).

Agricultural environmental measuring instruments (aM-31; Wisesensing, Yongin, Republic of Korea) were installed in the seedling nursery to collect data on atmospheric temperature and light intensity.

2.3. Image Acquisition

Images were acquired using a multispectral camera (FS-3200T-10GE-NNC, JAI Co., Ltd., Copenhagen, Denmark) at the vegetable science laboratory, Wonkwang University, in Iksan, Jeonbuk Special Self-Governing Province. Images were taken at 1-week intervals after grafting, up to 3 weeks post-grafting, corresponding to the shipping stage. In an environment where external light sources were controlled, light-emitting diodes provided suitable wavelength bands (white, 450 nm/550 nm/650 nm; red, 650 nm; NIR1, 740 nm; NIR2, 850 nm) for acquiring images. The chamber (100 cm width × 70 cm depth × 150 cm height) was equipped with two light-emitting diodes, one multispectral camera, and one LiDAR sensor (RPLiDAR A3M1, Slamtec Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, 785 nm) (

Figure 2). Wavelength bands of the multispectral camera were RGB (Red/Green/Blue; 450–650 nm), NIR1 (750 ± 50 nm), and NIR2 (830 ± 30 nm), and images were acquired across five bands, including three visible light bands (RGB) and two near-infrared bands (NIR1, NIR2).

During imaging, a white reference measuring 13 cm (L) × 2.5 cm (W) was placed alongside the cucumber seedlings (

Figure 3). After multispectral imaging, ENVI software (ENVI 5.3, Exelis Visual Information Solution Inc., Boulder, CO, USA) was used to mask the wavelength regions where the crop leaves reflected light, using five bands (RGB: 450, 550, 650 nm; NIR1: 750 nm; NIR2: 830 nm), and to obtain the number of pixels in these regions. Image data were preprocessed using the white reference in the RGB image. The actual area of the white reference (37.5 cm

2) was divided by the number of pixels in the multispectral image of the white reference (18,293) to calculate the area per pixel (0.0020499964 cm

2). Multiplying the number of pixels by the area of one pixel allowed for the derivation of the image value for leaf area.

2.4. Measurement of Actual Leaf Area Values

To compare the leaf area values obtained from imaging with the actual measurements, the leaf area was measured using the same plug tray seedlings used for imaging. Measurements were performed in three replicates of plug tray units. Leaf area was measured destructively using a leaf area meter (LI-3100C Area Meter, LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA), and each leaf was examined individually. The total leaf area per plant was recorded for all leaves, including cotyledons. For the plug tray units, leaf area was calculated by averaging the measurements of five seedlings selected from a 50-cell tray and multiplying by 50. Kaushaliya Madhavi et al. [

22] and Sandino et al. [

23] revealed that as leaf height becomes more uniform and the vertical spacing between leaves contracts, the overlapping of leaves increases, resulting in a reduced visible area in top-view images. Under these conditions, the percentage error between the actual and image-based measurements of leaf area at the plug tray level can be expressed by the following equation proposed by Kaushaliya Madhavi et al. [

22]:

This relationship highlights the importance of considering both the vertical structure of the plant and its changes in growth over time when modeling image-based leaf area. Error rates as high as 63% have been reported [

15]. Therefore, a similar error rate was expected in this study, and correcting this error was the primary objective.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Linear regression analysis was conducted to correct the leaf area values measured based on the images to more closely match the actual measurements. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Excel 2016, Microsoft 365, Redmond, WA, USA). The data were categorized by variety (GB, NC, and SD) and season (spring and summer). Regression models were developed using the leaf area-corrected imaging value (Y) as the dependent variable. Simple and multiple regression models were constructed with imaging-based leaf area (imaging value, X1) and DAG (X2) as independent variables. The equations for each model are as follows:

Multiple Regression Model:

where

Y is the corrected image value (cm

2),

X1 is the image-based leaf area acquired using the multispectral camera (cm

2),

X2 is days after grafting (DAG),

β0 is the Y-intercept, and

β1 and

β2 are the respective coefficients. All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation and differences among treatments were assessed using Tukey’s test at

p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Growth of Grafted Seedlings

The daily average temperature and daily light integral (DLI) in the nursery during spring and summer are shown in

Figure 4. During spring, the average temperature ranged from 20 to 25 °C, whereas in summer, it generally exceeded 28 °C. Interestingly, the DLI was higher in spring than in summer, which is presumed to reflect the shading measures applied in summer to prevent light damage caused by intense solar radiation. The optimal DLI for cucumber seedling production has been reported to be 6.35–11.52 mol m

−2 d

−1, and the optimal daytime temperature is between 25 and 28 °C [

24,

25,

26]. However, in the present study, the daily temperature during summer often exceeded 28 °C (

Figure 4), and consequently, the measured leaf area tended to be slightly smaller than in spring due to heat stress. Nevertheless, this seasonal difference was not statistically significant.

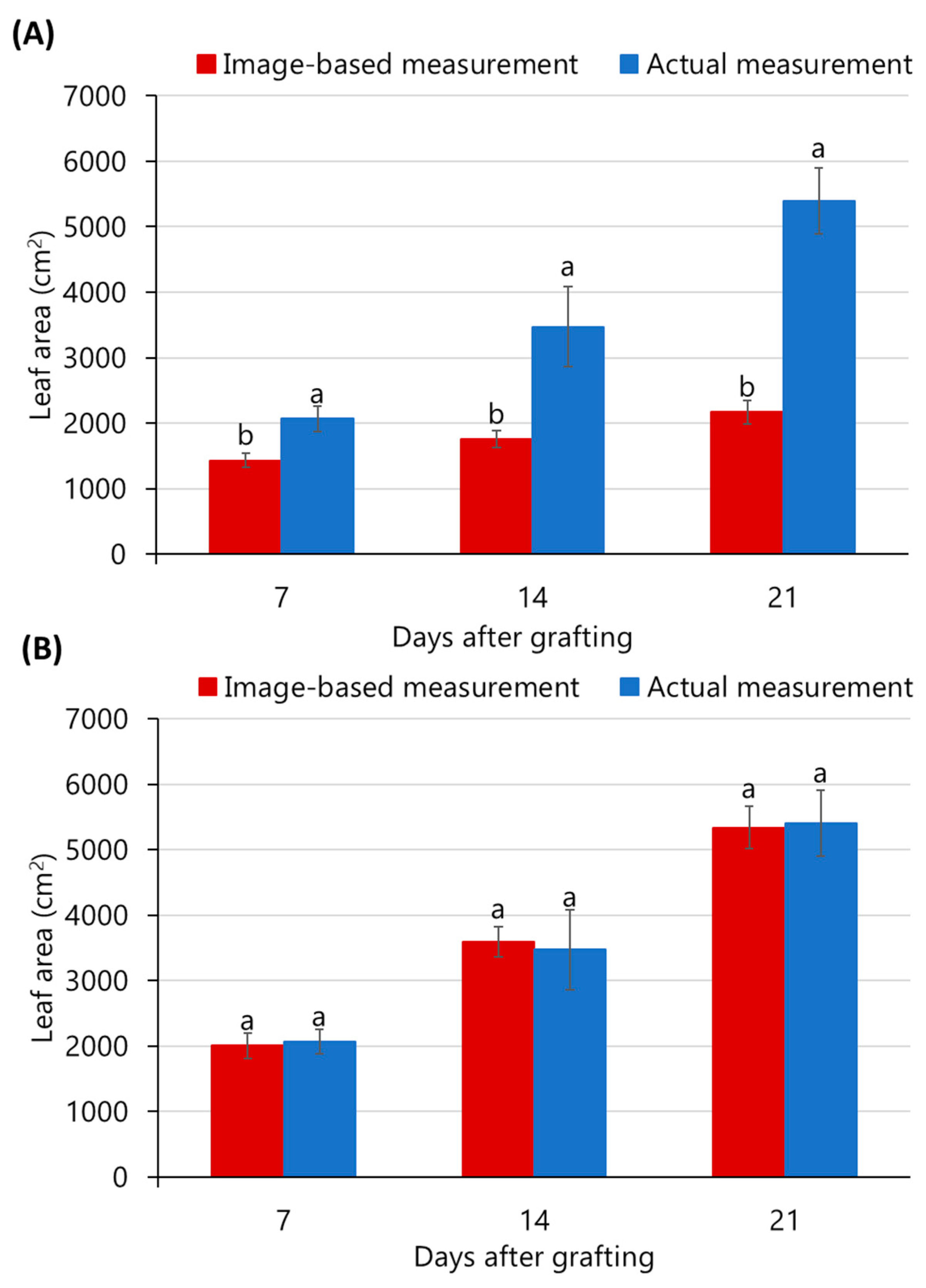

As shown in

Table 1, both the actual and image-based leaf area values gradually increased with an increase in the DAG. Consequently, there was a corresponding increase in the leaf overlap ratio, from approximately 29% at 7 DAG to approximately 60% at 21 days.

Comparatively, we detected no statistically significant differences in leaf area among the scion cultivars of cucumber (

Figure 5). At 21 DAG, the measured leaf area per plug tray ranged from approximately 5000 to 6000 cm

2 for GB, NC, and SD, and the image-based leaf area was approximately 2000 cm

2, showing no significant variation among cultivars. Over time after grafting, the cotyledons developed into leaves, and both the number of true leaves and leaf area tended to increase. A similar tendency was reported by Ban et al. [

27] and Chien and Lin [

28]. In the later growth stages, leaf overlap within the plug trays was pronounced, particularly as the DAG increased (

Table 1).

On all assessed days, the leaf area of the grafted cucumber seedlings measured using image-based analysis was lower than the actual measurement value. This can be interpreted as reflecting reduced accuracy in the image analysis due to leaf overlap from an increased number of true leaves. A similar tendency was reported by Li et al. [

16]. In that study, when measuring the leaf area of watermelon plug tray seedlings using Azure Kinect, the error rate increased as the number of true leaves increased, with leaf overlap intensifying (6.1% for one leaf, 6.9% for two leaves, and 12.1% for three leaves). In addition, Xu et al. [

29] reported that in watermelon plug trays, 8–10 days after sowing, the image-based leaf area was smaller than the actual measurement of leaf area based on 3D point cloud-based analysis. This agrees with the results of the present study, in which the leaf area of cucumber seedlings estimated using a multispectral camera was underestimated compared with the actual measured area. Therefore, considering both this study and previous research, as the development of true leaves progresses within plug trays, leaf area overlap increases, and the image-based measurement of leaf area tends to be underestimated. Accordingly, when measuring leaf area from the top view using an image-analysis system, a correction algorithm must be developed to deal with leaf area overlap.

In the early growth stages, errors occurred when growing medium and trays were recognized as plant parts, resulting in inaccurate estimations of leaf area. In the later growth stages, as the leaves grew within the limited area of the tray, the extent of the overlap increased, showing a tendency for the image value to be either overestimated or underestimated.

3.2. Overall Comparison

Figure 6 illustrates the association between image-based and actual measurement of leaf area depending on the inclusion of the variable DAG in the regression model. In the simple regression model excluding DAG, the coefficient of determination (

R2) was 0.8667, and the regression equation was

y = 0.214

x + 1003.4, indicating that the image-based leaf area measurements tended to be substantially underestimated compared with the actual measurements. In contrast, when DAG was included in the model, the

R2 increased to 0.9221, and the corresponding regression equation was

y = 0.9221

x + 284.18, showing a markedly enhanced agreement between image-based and actual leaf area values. These findings indicate that the inclusion of DAG effectively corrected for the underestimation of leaf area based on imaging caused by increasing leaf expansion and overlapping as time progressed after grafting. By incorporating DAG as a variable, the regression model more closely reflected morphological changes at different stages of growth, thereby enhancing the accuracy of image-based leaf area estimations.

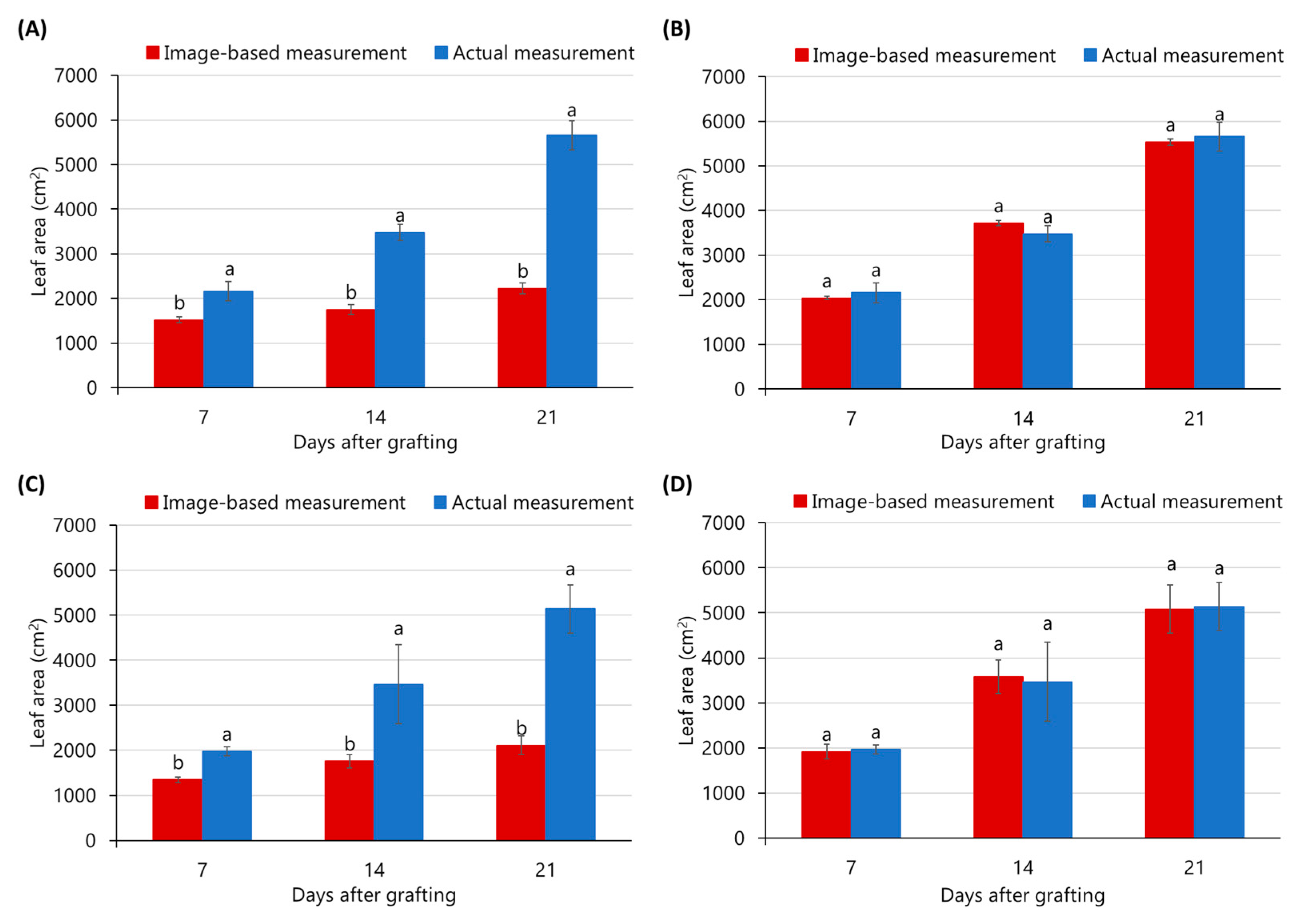

As shown in

Figure 7, in all treatments, there was a significant increase in leaf area as time progressed after grafting, reaching its highest value (approximately 6000 cm

2) at 21 DAG, which is consistent with the typical growth pattern in which true leaves expand, and leaf area gradually increases after grafting. However, at all assessed time points, image-based leaf area measurements were lower than the measured values, with the discrepancy becoming more pronounced during the later stages of growth (

Figure 7A). This tendency can be attributed to the heightened degree of leaf overlap during later growth, obscuring the lower leaves to a greater extent in the top-view images. In contrast, when DAG was included as a model variable, the image-based leaf area estimates were comparable with the actual measurements, particularly at 21 DAG (

Figure 7B).

This enhancement can be explained physiologically in terms of the temporal growth pattern of leaves following grafting. Shortly after grafting, leaf growth is limited, and overlapping is minimal. With a subsequent progression of DAG, true leaves develop, and the canopy gradually expands, leading to a greater degree of overlap and the occlusion of lower leaves in top-view images. Consequently, DAG can be interpreted as an indirect indicator of the degree of leaf overlap, and its inclusion in the regression model effectively corrected estimation errors in image-based leaf area caused by growth-related overlapping.

Similarly, previous studies have reported improvements in the accuracy of leaf area prediction through the application of time-based correction variables. For example, Cho and Son [

30], Du et al. [

31], and Bantis and Koukounaras [

32] demonstrated that incorporating the parameters days after sowing or growing degree days contributed to enhancing the accuracy of predictions. In the present study, the application of a multiple linear regression model incorporating DAG yielded a higher

R2 value than the simple regression model, with the value of the correlation coefficient increasing from 0.86 to 0.92 at the plug tray level, indicating a mitigation of the leaf overlap-induced error. These findings are consistent with those reported by Zou et al. [

33], who obtained a very high correlation (

R2 > 0.99) between cumulative leaf dimensions and grafting days in grafted tomato seedlings.

Our findings serve as an empirical example, indicating that the integration of DAG as a variable reflecting growth stage can facilitate a significant enhancement of the accuracy of image-based leaf area estimations, and thereby contribute to the development of precise growth monitoring systems for high-quality seedling production. Accordingly, we believe that the incorporation of DAG in regression models represents a promising approach not only for cucumbers but also for other Cucurbitaceae crops for which grafting is essential, such as watermelon and pumpkin.

3.3. Comparison by Variety

The overall trends observed in the total comparison were consistent among the different cultivars, indicating that the inclusion of DAG markedly enhanced the correlation between image-based and actual measurements of leaf area (

Figure 8). When DAG was excluded, the image-based measurements of leaf area tended to be underestimated for all three assessed cultivars, with correspondingly relatively low coefficients of determination (

R2 = 0.8850–0.8928). This underestimation is presumed to be attributable to the expansion of true leaves and an increase in the overlap of adjacent leaves as time progresses after grafting, thereby reducing the visibly detectable leaf area in top-view images.

In contrast, when DAG was included as a correction factor, the accuracy of leaf area estimates for all three cultivars significantly increased. The coefficients of determination increased to 0.9233–0.9562, and the regression slopes approached 1.0, indicating that the image-derived leaf areas closely matched the actual measured values. These findings accordingly that a consideration of DAG can effectively compensate for changes in leaf overlap and canopy structure occurring during the post-grafting growth period.

Among the cultivars, the highest accuracy when including DAG was obtained for GB (

R2 = 0.9562;

Figure 8A), followed by SD (

R2 = 0.9523;

Figure 8B) and NC (

R2 = 0.9323;

Figure 8C). The consistently high corrected

R2 values indicate that the same regression model could be applied for other cucumber cultivars.

At the plug tray level, the image-based leaf area values obtained without DAG correction (

Figure 9A,C,E) remained nearly constant at approximately 2000 cm

2 for all cultivars, even as DAG increased from 7 to 21, and were consistently underestimated compared with the actual measurement values with the progression of DAG, with the largest discrepancies being observed at 21 DAG. In contrast, with the application of DAG correction (

Figure 9B,D,F), the extent of this underestimation was substantially reduced, with the image-based estimates improving to levels comparable with the actual measurements, particularly at 14 and 21 DAG.

These findings indicate that by reflecting the degree of leaf overlap at different stages of growth, the variable DAG can effectively contribute to correcting estimation errors. Consequently, incorporating DAG in regression models is considered to represent an effective approach for enhancing the accuracy of image-based leaf area estimation, regardless of differences in cultivars.

3.4. Comparison by Season

The trends observed in overall and cultivar-based comparisons were consistently confirmed in the seasonal comparisons. For both seasons (spring and summer), we obtained enhanced correlations between image-based and actual measured leaf areas when using regression models incorporating DAG (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). In particular, in spring (

Figure 10A), DAG inclusion contributed to a substantial improvement in accuracy (

R2 = 0.9570) compared with the model without DAG (

R2 = 0.8579), and a similar enhancement was observed in summer (

Figure 10B;

R2 = 0.9080 including DAG and 0.8855 excluding DAG). These findings indicate that regardless of seasonal environmental differences, such as light intensity and temperature, the application of DAG can contribute to enhancing the consistency and reliability of leaf area estimation.

The regression model incorporating DAG-based correction consistently showed superior predictive performance, not only among cultivars but also for different seasons, indicating that the same regression equation could be applied universally for grafted cucumber seedlings. In practical nursery operations, in which seedlings are produced and shipped year-round, environmental conditions such as temperature and light intensity are generally maintained within a narrow range. Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that the minor environmental variations among seasons would not have a significant influence on the estimation of leaf area (

Table 1), thus indicating that the correction model proposed in this study could be uniformly applied under actual nursery conditions.

Currently, seedling nurseries invest considerable time and labor in selecting high-quality seedlings. Consequently, non-destructive methods for evaluating seedling quality are an important consideration for reducing labor costs and ensuring consistent selection. Several different approaches aimed at minimizing estimation errors have been assessed [

13]. The regression model proposed in the present study, incorporating DAG-based correction, provides a practical solution to these challenges. With continuous data accumulation, it could be used to further minimize stage-specific estimation errors and enable rapid field-level implementation in commercial nurseries.

Due to the limited number of plug tray replicates in this study, it was not feasible to reliably train complex nonlinear or machine learning models. Consequently, as a more practical approach, we adopted a linear regression model, given its lower risk of overfitting and more ready interpretability. In nursery and open-field remote sensing studies focusing on leaf area index or leaf area estimations, linear regression has been widely employed to establish corrections in relationships between image/spectral indices and actual measurements [

27,

34,

35]. Moreover, this approach also facilitates direct comparisons with previous studies and provides a useful baseline for future research.

Although the linear regression model was optimized for estimating the leaf area of grafted cucumber seedlings, the concept of using DAG to correct for leaf overlap can, in theory, be extended to the seedling growth processes of other crops. Accordingly, future studies should collect data from a broader range of crops and growing conditions and apply nonlinear or data-driven approaches, such as polynomial regression or machine learning, to enhance the generalizability and predictive robustness of models.

4. Conclusions

This study adopted a multispectral imaging approach to address the issue of leaf overlap in leaf area estimation by introducing DAG as a correction variable in a multiple regression model to reflect the growth stages of a given crop.

Across all experimental conditions, including different cultivars and seasons, the inclusion of DAG significantly improved the accuracy of leaf area estimates, with the R2 increasing from 0.86 to 0.92 at the plug tray level. This improvement was consistent for three cucumber cultivars, ‘Goodmorning Backdadagi,’ ‘NakwonSeongCheongJang,’ and ‘Sinsedae,’ as well as in both spring and summer. No significant differences in R2 were observed among cultivars, seasons, or DAG inclusion conditions, indicating that the proposed correction model is broadly applicable for practical use in seedling nurseries.

Nonetheless, this study was conducted under specific environmental and imaging conditions using a limited spectral range. To enhance model generalizability and operational relevance, future research should examine a wider variety of crop species and cultivation settings. Incorporating advanced modeling techniques such as polynomial regression or machine learning could further improve model performance and applicability across diverse production environments.