Seasonal Changes in Physiological Responses and Yield of Citrus latifolia Under High-Density Planting and Different Soil Moisture Tensions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

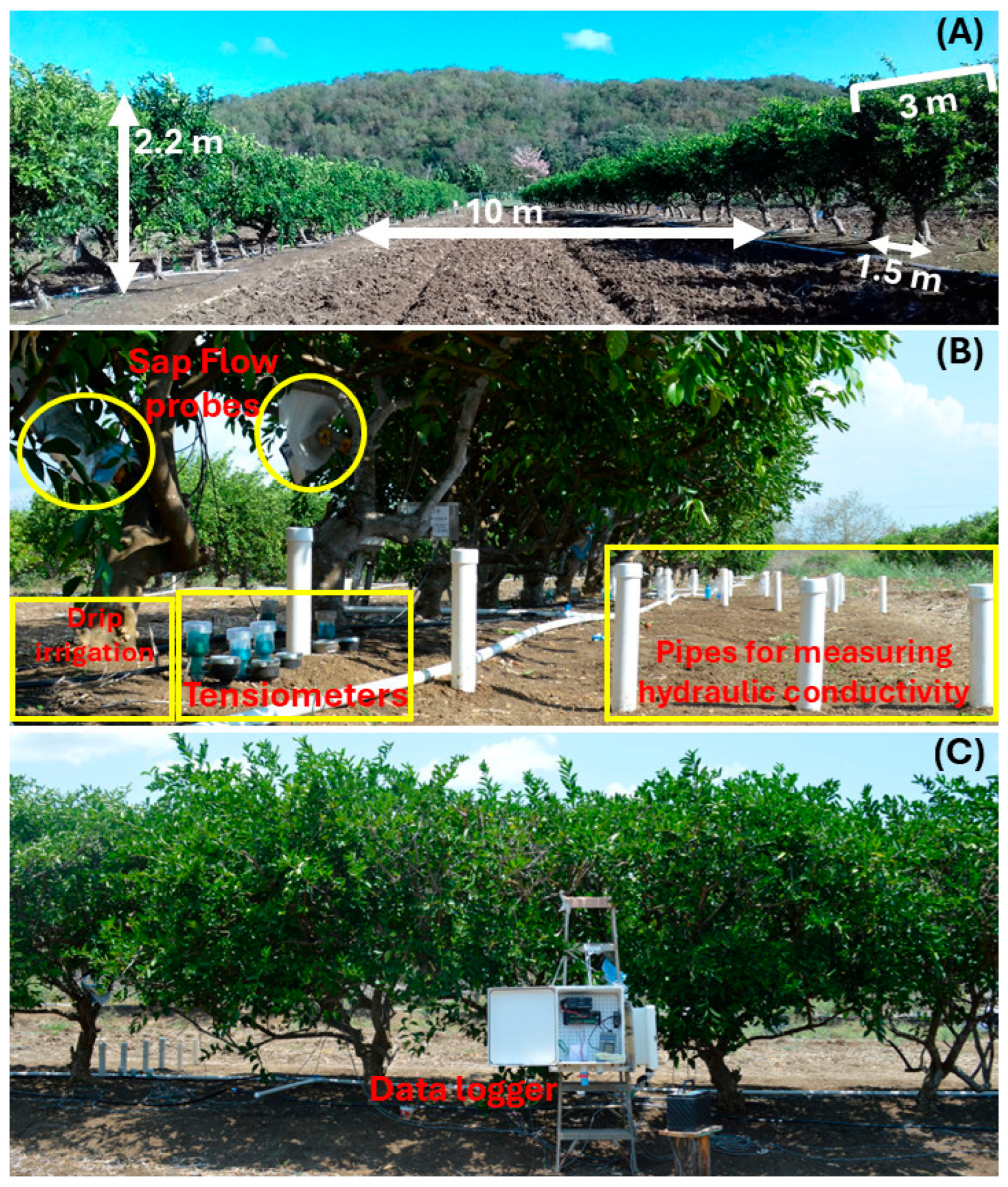

2.1. Site Location and Orchard Characteristics

2.2. Evaluated Treatments

2.3. Evaluated Variables

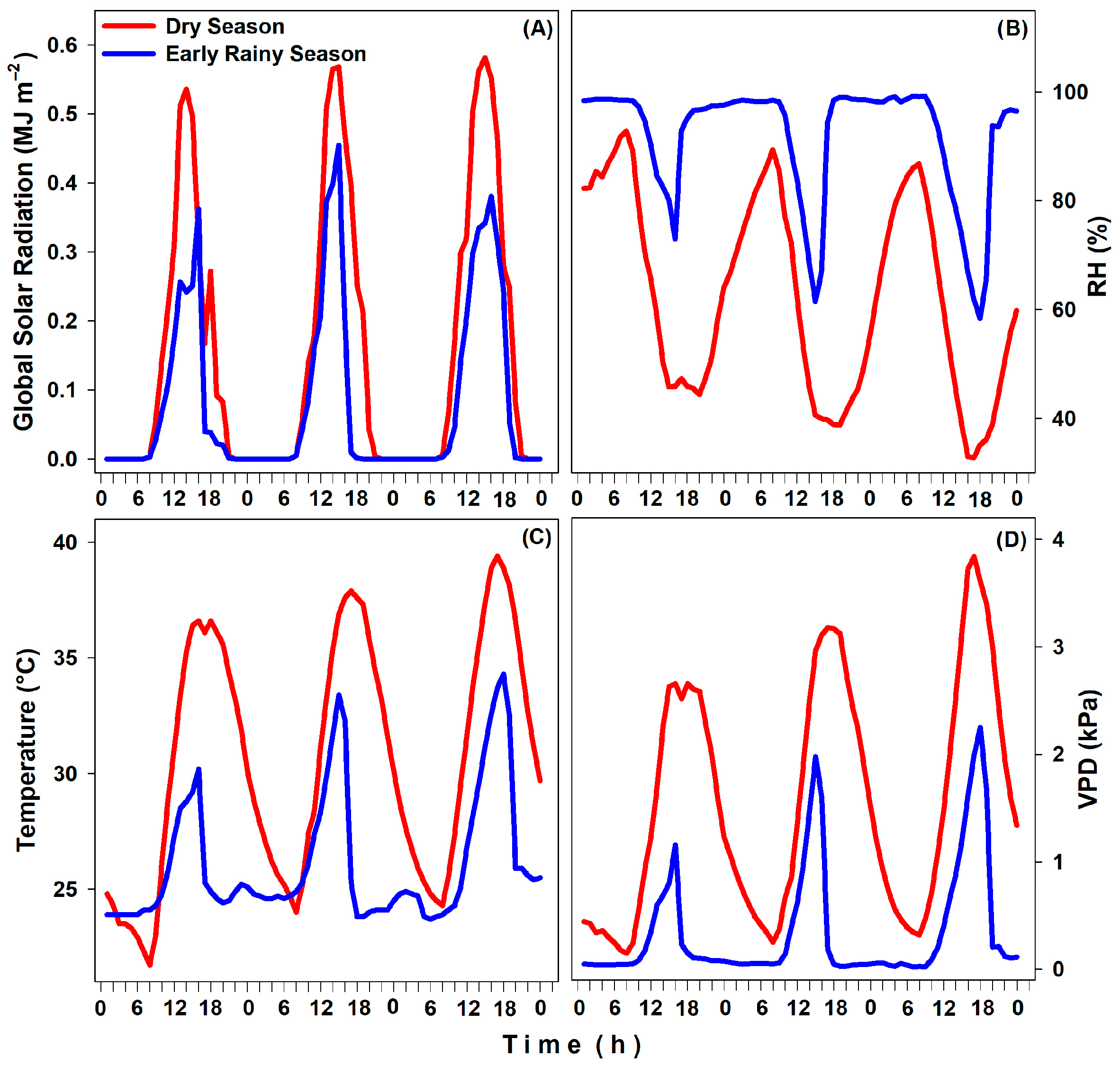

2.3.1. Microclimate Data and Water Status

2.3.2. Sap Flow Measurements

2.3.3. Leaf Photochemistry and Gas Exchange Measurements

2.3.4. Leaf Area Index, Shoot Growth, and Yield Measurements

2.4. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Microclimate Data, Water Potential, and Relative Water Content

3.2. Sap Flow

3.3. Leaf Photochemistry and Gas Exchange

3.4. Leaf Area Index, Shoot Growth, and Yield

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AN | Net photosynthetic rate |

| DS | Dry season |

| E | Transpiration rate |

| ETR | Electron transport rate |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| gs | Stomatal conductance |

| H | High soil moisture tension (−0.085 MPa) |

| LAI | Leaf area index |

| L | Low soil moisture tension (−0.010 MPa) |

| M | Medium soil moisture tension (−0.035 MPa) |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| NPQ | Non-photochemical quenching |

| PAM | Pulse amplitude modulated (fluorometer) |

| qN | Non-photochemical quenching coefficient |

| qP | Photochemical quenching coefficient |

| Rg | Global solar radiation |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| RS | Rainy season |

| RWC | Relative water content |

| SF | Sap flow |

| SMT | Soil moisture tension |

| VPD | Vapor pressure deficit |

| ΨL | Leaf water potential |

| Ψstem | Stem water potential |

| WUE | Water use efficiency |

| ΦPSII | Effective quantum yield of photosystem II |

| Fv/Fm | Maximum quantum yield of photosystem II |

References

- De Ollas, C.; Morillón, R.; Fotopoulos, V.; Puértolas, J.; Ollitrault, P.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Arbona, V. Facing climate change: Biotechnology of iconic Mediterranean woody crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, D.W.; Tezara, W. Causes of decreased photosynthetic rate and metabolic capacity in water-deficient leaf cells: A critical evaluation of mechanisms and integration of processes. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezara, W.; Urich, R.; Coronel, I.; Marín, O.; Herrera, A. Asimilación de carbono, eficiencia de uso de agua y actividad fotoquímica en xerófitas de ecosistemas semiáridos de Venezuela. Ecosistemas 2010, 19, 67–78. Available online: https://www.revistaecosistemas.net/index.php/ecosistemas/article/view/37 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Rivero, R.M.; Martínez, V.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Arbona, V. Tolerance of citrus plants to the combination of high temperatures and drought is associated with increased transpiration modulated by a reduction in abscisic acid levels. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.V.; Machado, E.C. Some aspects of citrus ecophysiology in subtropical climates: Revisiting photosynthesis under natural conditions. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2007, 19, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.V.; Machado, E.C.; Santos, M.G.; Oliveira, R.F. Photosynthesis and water relations of well-watered orange plants as affected by winter and summer conditions. Photosynthetica 2009, 47, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, C.; Guardiola, J.L.; Nebauer, S.G. Response of the photosynthetic apparatus to a flowering-inductive period by water stress in Citrus. Trees 2012, 26, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Santos, M.R.; Donato, S.L.R.; Coelho, E.F.; Arantes, A.M.; Coelho-Filho, M.A. Irrigação lateralmente alternada em lima ácida ‘Tahiti’ na região norte de Minas Gerais. Irrigação 2016, 1, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- da Silva, C.R.; Folegatti, M.V.; Araújo, S.T.J.; Alves, J.J.; Fonseca, S.C.; Vasconcelos, R.R. Water relations and photosynthesis as criteria for adequate irrigation management in ‘Tahiti’ lime trees. Sci. Agric. 2005, 62, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIAP-SAGARPA. Atlas Agroalimentario 2019; Secretaría de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019; pp. 140–141. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/siap (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Quej, V.H.; Almorox, J.; Arnaldo, J.A.; Moratiel, R. Evaluation of temperature-based methods for the estimation of reference evapotranspiration in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2018, 24, 05018029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, G.; Nakhforoosh, A.; Kaul, H.P. Management of crop water under drought: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 401–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.M.; Lagadec, M.D.L. Increasing the productivity of avocado orchards using high density plantings: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 177, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.S.; Goswami, A.K. High density planting in fruit crops. HortFlora Res. Spectr. 2016, 5, 261–264. Available online: https://hortflorajournal.com/AbstractInfo.aspx?ContentId=442 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, Update 2015: International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; World Soil Resources Reports No. 106; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Agustí, M.; Zaragoza, S.; Bleiholder, H.; Hack, H.; Klose, R. Escalas Fenológicas BBCH de los Cítricos; Conselleria d’Agricultura, Pesca i Alimentació, Generalitat Valenciana: Valencia, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Hernández, B.; Garruña-Hernández, R.; Carrillo-Ávila, E.; Quej-Chi, V.H.; Andrade, J.L.; Andueza-Noh, R.H.; Arreola-Enríquez, J. Using splines in the application of the instantaneous profile method for the hydrodynamic characterization of a tropical agricultural Vertisol. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2022, 46, e0210086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, F.; Syvertsen, J.P.; Gimeno, V.; Botía, P.; Perez-Perez, J.G. Responses to flooding and drought stress by two citrus rootstock seedlings with different water-use efficiency. Physiol. Plant. 2007, 130, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier, A. Une nouvelle méthode pour la mesure flux de séve brute dans le tronc des arbres. Ann. Sci. For. 1985, 42, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier, A. Evaluation of transpiration in a Douglas-fir stand by means of sap flow measurements. Tree Physiol. 1987, 3, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Urban, L.; Zhao, P. Granier’s Thermal Dissipation Probe (TDP) method for measuring sap flow in trees: Theory and practice. Acta Bot. Sin. 2004, 46, 631–646. Available online: https://www.ishs.org/sites/default/files/documents/lu2004.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Coelho, R.D.; Vellame, L.M.; Júnior, E.F. Estimation of transpiration of the ‘Valencia’ orange young plant using thermal dissipation probe method. Eng. Agríc. 2012, 32, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego-Gámez, B.Y.; Garrúna, R.; Tun-Suárez, J.M.; Kantun-Can, J.; Reyes-Ramírez, A.; Cervantes-Díaz, L. Bacillus spp. inoculation improves photosystem II efficiency and enhances photosynthesis in pepper plants. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 76, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gamir, J.; Primo-Millo, E.; Forner-Giner, M.A. An integrated view of whole-tree hydraulic architecture: Does stomatal or hydraulic conductance determine whole tree transpiration? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miserere, A.; Searles, P.S.; Manchó, G.; Maseda, P.H.; Rousseaux, M.C. Sap flow responses to warming and fruit load in young olive trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenes, N.; Kerr, K.L.; Trugman, A.T.; Anderegg, W.R.L. Competition and drought alter optimal stomatal strategy in tree seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortuño, M.F.; Conejero, W.; Moreno, F.; Moriana, A.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Biel, C.; Mellisho, C.D.; Pérez-Pastor, A.; Domingo, R.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.C.; et al. Could trunk diameter sensors be used in woody crops for irrigation scheduling? A review of current knowledge and future perspectives. Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalley, M.J.; Phillips, N. Interspecific variation in nighttime transpiration and stomatal conductance in a mixed New England deciduous forest. Tree Physiol. 2006, 26, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, C.; Castel, J.; Testi, L.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R. Can heat-pulse sap flow measurements be used as continuous water stress indicators of citrus trees? Irrig. Sci. 2013, 31, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.R. Chlorophyll fluorescence: A probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Lawson, T. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: A guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, D.W. Limitation to photosynthesis in water-stressed leaves: Stomata vs. metabolism and the role of ATP. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilkens, M.; Kress, E.; Lambrev, P.; Miloslavina, Y.; Müller, M.; Holzwarth, A.R.; Jahns, P. Identification of a slowly inducible zeaxanthin-dependent component of non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence generated under steady-state conditions in Arabidopsis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, A.M.; Ball, M.C. Protection and storage of chlorophyll in overwintering evergreens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 11098–11101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A.V.; Johnson, M.P.; Duffy, C.D.P. The photoprotective molecular switch in the photosystem II antenna. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1817, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, G.H.; Weis, E. Chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis: The basics. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1991, 42, 313–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G.N. Chlorophyll fluorescence—A practical guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jifon, J.L.; Syvertsen, J.P. Moderate shade can increase net gas exchange and reduce photoinhibition in citrus leaves. Tree Physiol. 2003, 23, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu, A.; Terzi, R.; Saruhan, N.; Saglam, A. Current advances in the investigation of leaf rolling caused by biotic and abiotic stress factors. Plant Sci. 2012, 182, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munné-Bosch, S.; Alegre, L. Die and let live: Leaf senescence contributes to plant survival under drought stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2004, 31, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, A.C.R.; Prudente, D.A.; Machado, E.C.; Ribeiro, R.V. Daily temperature amplitude affects the vegetative growth and carbon metabolism of orange trees in a rootstock-dependent manner. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 31, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, D.J.; Tadeo, F.R.; Primo-Millo, E.; Talon, M. Fruit set dependence on carbohydrate availability in citrus trees. Tree Physiol. 2003, 23, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Hernández, B.; González-Jiménez, V.; Carrillo-Ávila, E.; Garruña-Hernández, R.; Andrade, J.L.; Quej-Chi, V.H.; Arreola-Enríquez, J. Yield, Physiology, Fruit Quality and Water Footprint in Persian Lime (Citrus latifolia Tan.) in Response to Soil Moisture Tension in Two Phenological Stages in Campeche, México. Water 2022, 14, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartzoulakis, K.; Michelakis, N.; Stefanoudaki, E. Water use, growth, yield and fruit quality of ‘Bonanza’ oranges under different soil water regimes. Adv. Hortic. Sci. 1999, 13, 6–11. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42881974?utm_source=chatgpt.com&seq=1 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Alves, J.J.; Silva, C.R.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Silva, T.J.A.; Folegatti, M.V. Growth of young ‘Tahiti’ lime trees under irrigation levels. Eng. Agríc. 2005, 25, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, H.B.; Mourão, F.D.A.A.; Stuchi, E.S.; Espinoza-Nuñez, E.; Cantuarias-Avilés, T. The horticultural performance of five ‘Tahiti’ lime selections grafted onto ‘Swingle’ citrumelo under irrigated and non-irrigated conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 150, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Urrutia, V.M.; Robles-González, M.M.; Rocha-Peña, M.A.; Virgen-Calleros, G.; Reyes-Hernández, J.; Fernández-Rivera, E. Growth, yield and fruit quality of Tahiti lime on eight standard rootstocks affected by soil depth. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2014, 4, 793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Nuñez, E.; Mourão Filho, F.A.A.; Stuchi, E.S.; Cantuarias-Avilés, T.; Santos-Dias, C.T. Performance of ‘Tahiti’ lime on twelve rootstocks under irrigated and non-irrigated conditions. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 129, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Hernández, B.; Garruña-Hernández, R.; Santamaría-Basulto, F.; Andrade-Torres, J.L.; Carrillo-Ávila, E.; Andueza-Noh, R.H. Lime yield (Citrus × latifolia Tanaka ex Q. Jiménez) and fruit quality in the winter season from orchards maintained with different soil moisture tension. Agroproductividad 2020, 13, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivera-Hernández, B.; Garruña, R.; Andrade, J.L.; Tezara, W.; Us Santamaría, R.; Andueza-Noh, R.H.; González-Jiménez, V.; Carrillo-Ávila, E. Seasonal Changes in Physiological Responses and Yield of Citrus latifolia Under High-Density Planting and Different Soil Moisture Tensions. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121472

Rivera-Hernández B, Garruña R, Andrade JL, Tezara W, Us Santamaría R, Andueza-Noh RH, González-Jiménez V, Carrillo-Ávila E. Seasonal Changes in Physiological Responses and Yield of Citrus latifolia Under High-Density Planting and Different Soil Moisture Tensions. Horticulturae. 2025; 11(12):1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121472

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivera-Hernández, Benigno, René Garruña, José Luis Andrade, Wilmer Tezara, Roberth Us Santamaría, Rubén H. Andueza-Noh, Vianey González-Jiménez, and Eugenio Carrillo-Ávila. 2025. "Seasonal Changes in Physiological Responses and Yield of Citrus latifolia Under High-Density Planting and Different Soil Moisture Tensions" Horticulturae 11, no. 12: 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121472

APA StyleRivera-Hernández, B., Garruña, R., Andrade, J. L., Tezara, W., Us Santamaría, R., Andueza-Noh, R. H., González-Jiménez, V., & Carrillo-Ávila, E. (2025). Seasonal Changes in Physiological Responses and Yield of Citrus latifolia Under High-Density Planting and Different Soil Moisture Tensions. Horticulturae, 11(12), 1472. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae11121472