Abstract

Bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) are nanosized (10–400 nm), membrane-enclosed particles naturally secreted by both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Initially characterized as virulence factors in pathogenic species, BEVs are now recognized as multifunctional entities with significant biotechnological potential. Their cargo—comprising proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and metabolites—enables diverse biological activities, including immune modulation, epithelial barrier protection, stress tolerance, and intercellular communication. Recent studies have highlighted BEVs from biotechnologically relevant bacteria—such as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria, lactic acid bacteria, bifidobacteria, cyanobacteria, bacilli, and streptomycetes—for their different roles in biological and ecological interactions. These properties underpin emerging applications in health, agriculture, and bioprocessing, including next-generation postbiotics, vaccine platforms, drug and RNA delivery systems, and novel plant biostimulants. However, major challenges persist, particularly low production yields, variability in cargo composition, and scalability. Addressing these limitations requires a deeper understanding of vesiculation mechanisms and the development of process-oriented strategies for BEV recovery and purification. This review synthesizes recent advances in genetic analysis, physiological modulation, physicochemical stimuli, and bioprocess optimization aimed at enhancing BEV production and stabilizing cargo profiles, providing a comprehensive overview of approaches to unlock the full potential of BEVs as versatile biotechnological tools.

1. Introduction

Bacterial extracellular vesicles (BEVs) are nanosized (10–400 nm), spherical, membrane-enclosed particles released by virtually all bacteria. They play essential roles in microbe-microbe and host–microbe interactions, including immune modulation, signaling, and pathogenesis [1,2].

The biogenesis and structural diversity of BEVs differ between Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria due to their distinct cell envelope organization [1,2].

In Gram-negative bacteria, BEVs originate either from blebbing of the outer membrane, giving rise to outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) that are typically devoid of cytosolic cargo, or through endolysin-triggered explosive cell lysis, which results in the release of outer–inner membrane vesicles (OIMVs) and explosive outer membrane vesicles (EOMVs) containing cytosolic components [2,3]. Because they mirror the composition of the outer membrane, BEVs from Gram-negative bacteria expose lipopolysaccharide (LPS) on their surface, enabling activation of host immune cells [4].

In contrast, Gram-positive bacteria lack an outer membrane and produce extracellular membrane vesicles (EMVs or CMVs) derived from the cytoplasmic membrane. Although their biogenesis remains less well understood, both blebbing and lysis-derived mechanisms have been described. These vesicles typically encapsulate cytosolic cargo and present peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid (LTA) on their surface, contributing to host immune cell activation [2,5]. Despite these structural and mechanistic differences, all BEVs share the capacity to transport heterogeneous biomolecular cargo—including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and metabolites—fundamental to their biological functional versatility [1,2,5].

Initially studied primarily as virulence factors in pathogens, BEVs have recently emerged as promising biotechnological tools [1,6]. Beyond their roles in immune modulation and toxin delivery, vesicles derived from probiotic and industrially relevant bacteria contribute to beneficial effects such as gut barrier protection, immune regulation, stress tolerance, and inter-microbial communication. This functional diversity underscores their potential applications in health, agriculture, and bioprocessing, while highlighting the need to address key challenges related to production yield, cargo consistency, purification efficiency, and scalability.

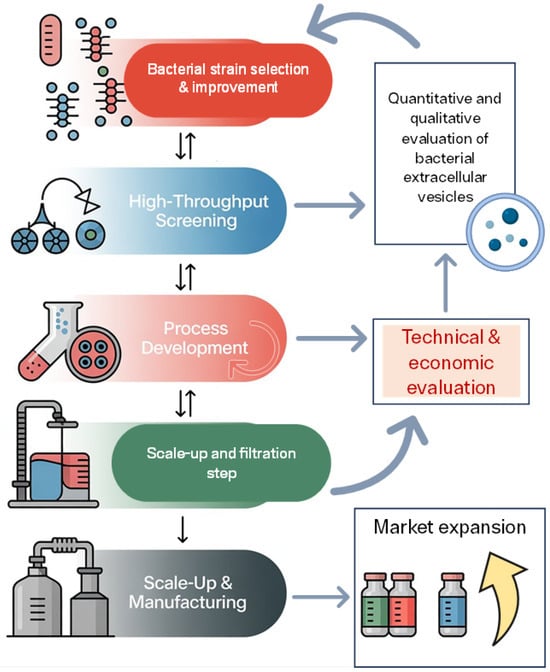

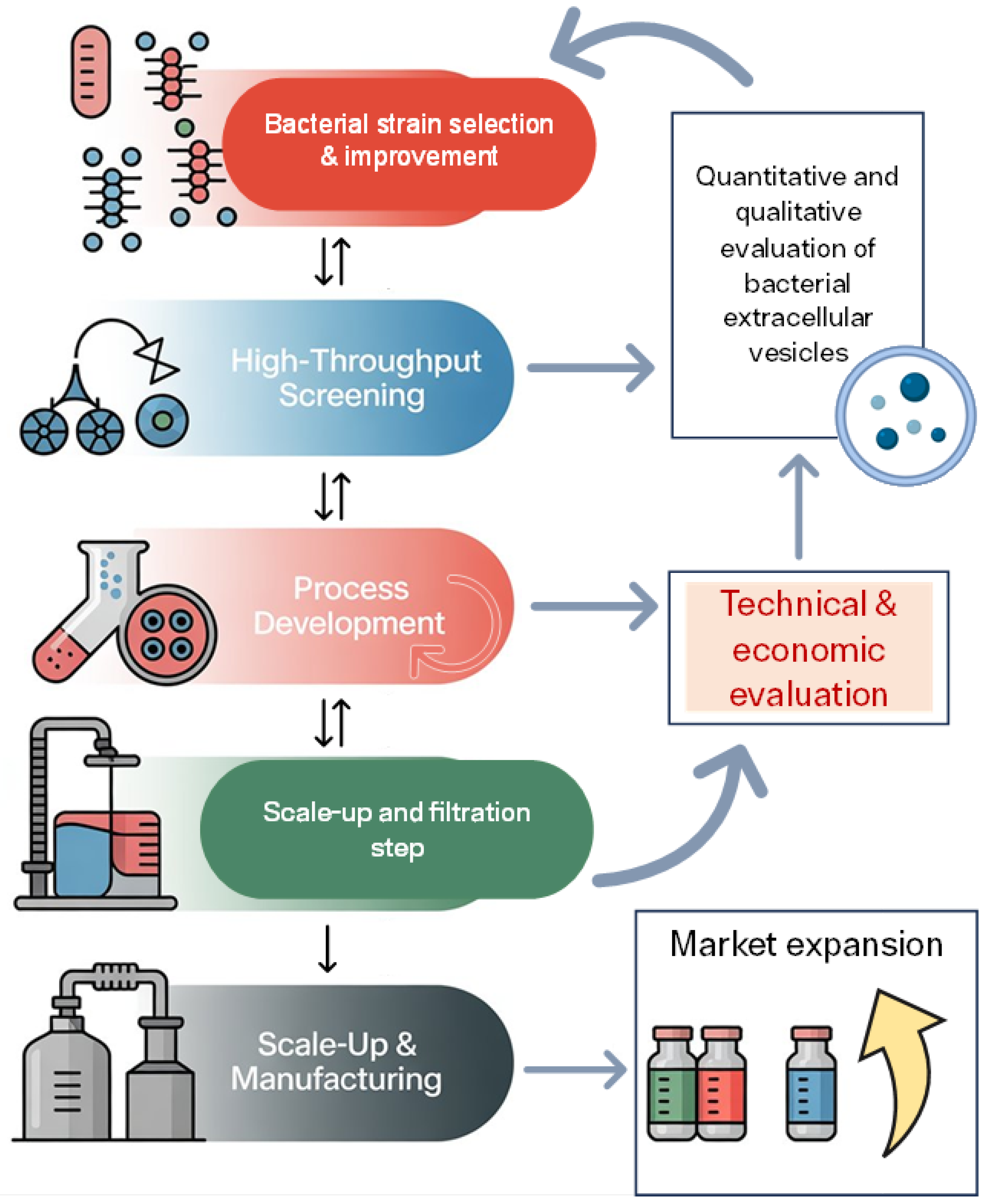

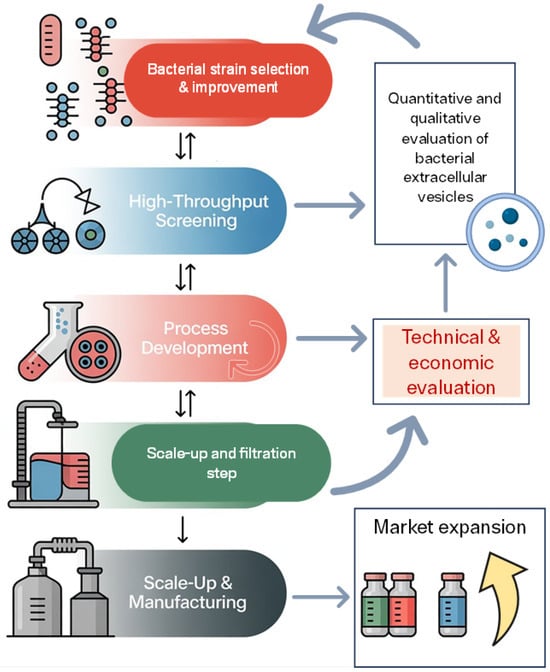

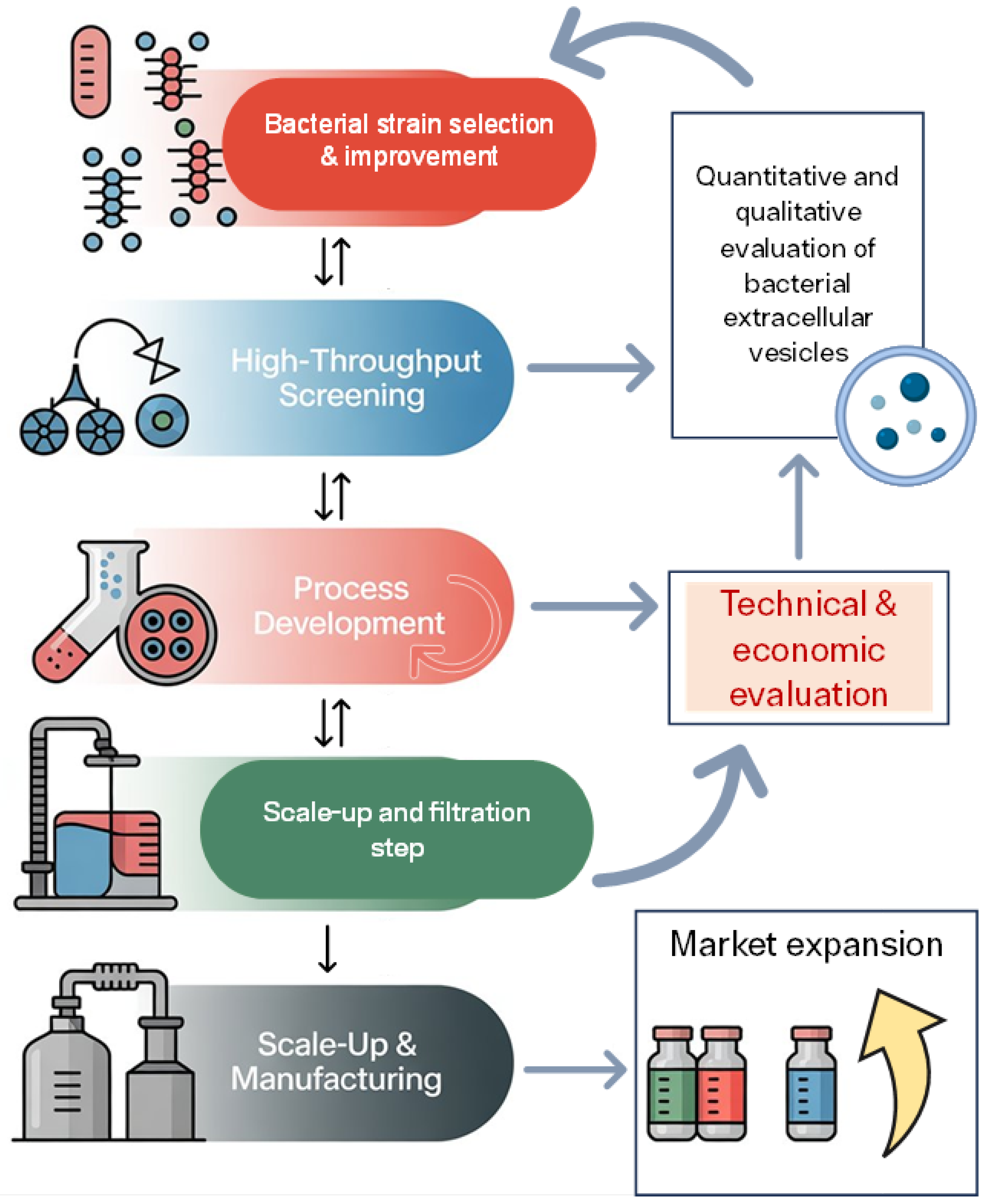

This review focuses on strategies to enhance BEV production and functionality for biotechnological applications. We discuss approaches—including genetic manipulation, physiological modulation, controlled environmental stimuli, and advanced bioprocess optimization (Figure 1)—drawing on recent studies published in the last five years, with particular emphasis on BEVs derived from beneficial or industrially relevant bacteria.

1.1. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles as Biotechnological Tools

Historically, research on BEVs has focused on Gram-negative pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Helicobacter pylori, Escherichia coli, Neisseria meningitidis, and Vibrio cholerae. These early investigations established BEVs—particularly OMVs—as a key mediator of virulence, toxin delivery, immune modulation, and antimicrobial resistance [7,8]. Over the past decade, however, a paradigm shift has emerged, as beneficial and industrially relevant bacteria have also been shown to produce BEVs with functional properties exploitable for biotechnological applications. BEVs from lactic acid bacteria—such as Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG (formerly Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG) and Lactobacillus johnsonii—and other beneficial bacteria belonging to the Bacillus and Streptomyces genera, as well as Cyanobacteria, have been shown to mediate intercellular communication, modulate host immunity, and influence plant or gut microbial community physiology [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Probiotic-derived BEVs have attracted particular attention for their immunomodulatory and barrier-protective effects. BEVs from L. rhamnosus GG strengthen epithelial tight junctions and modulate cytokine secretion [9,10], whereas vesicles from L. johnsonii deliver small RNAs capable of altering human epithelial cell transcriptomes [11]. Bacillus subtilis releases BEVs that can trigger immune responses in animals, highlighting their role in both ecological fitness and biotechnological applications [12,13]. Additionally, BEVs derived from a genetically engineered B. subtilis mitigate inflammatory responses, restoring the impaired intestinal barriers and modulating gut microbiota in mice [14]. Streptomyces species were recently shown to produce vesicles enriched in bioactive metabolites, including antibiotics [15]. Cyanobacteria produce EVs as part of an overlooked secretion system. These vesicles carry proteins, lipids, and metabolites involved in nutrient exchange, intercellular communication, and defense against environmental stress, highlighting their key role in ecological interactions and microenvironment modulation [16].

Figure 1.

Workflow for optimizing bacterial extracellular vesicle (BEV) production and commercialization. The process begins with bacterial strain selection and improvement, followed by high-throughput screening, including omics analyses, to identify high-yield EV producers with stable and uniform cargo composition (represented as circles of the same color). Process development focuses on optimizing fermentation conditions and vesicle recovery. Subsequent scale-up and filtration steps enable transition from laboratory to pilot scale, ensuring BEV integrity and purity. Scale-up and manufacturing represent the final stage of industrial production. Throughout the workflow, quantitative and qualitative evaluation of BEVs and technical and economic assessments guide decision-making and process refinement. The ultimate goal is market expansion (upward arrow indicates expansion in market size, reach, or geographical distribution), leveraging BEVs for biotechnological applications in fields such as biomedicine, cosmetics, food, and agriculture.

Figure 1.

Workflow for optimizing bacterial extracellular vesicle (BEV) production and commercialization. The process begins with bacterial strain selection and improvement, followed by high-throughput screening, including omics analyses, to identify high-yield EV producers with stable and uniform cargo composition (represented as circles of the same color). Process development focuses on optimizing fermentation conditions and vesicle recovery. Subsequent scale-up and filtration steps enable transition from laboratory to pilot scale, ensuring BEV integrity and purity. Scale-up and manufacturing represent the final stage of industrial production. Throughout the workflow, quantitative and qualitative evaluation of BEVs and technical and economic assessments guide decision-making and process refinement. The ultimate goal is market expansion (upward arrow indicates expansion in market size, reach, or geographical distribution), leveraging BEVs for biotechnological applications in fields such as biomedicine, cosmetics, food, and agriculture.

1.2. Beneficial Effects of Bacteria Are Related to Their Extracellular Vesicle Cargo

The functional diversity of BEVs produced by beneficial bacteria has become increasingly evident over the past decade, revealing their role as sophisticated mediators of intercellular communication, host–microbe interactions, microbial community dynamics, and metabolite or enzyme delivery. Unlike BEVs from pathogenic bacteria, BEVs derived from commensal, probiotic, or industrial microbes often exert protective, regulatory, or metabolically advantageous functions within their environments. Among the most extensively studied producers are lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Vesicles released by Lacticaseibacillus and Lactobacillus species interact directly with epithelial and immune cells, modulating host responses and contributing to intestinal homeostasis. For instance, L. rhamnosus GG produces vesicles carrying proteins such as p40 and p75, which activate epithelial survival pathways and support tight-junction integrity [9,10]. Similarly, L. johnsonii secretes BEVs enriched in small regulatory RNAs that alter host gene expression, suggesting a mechanism of inter-kingdom communication that may shape immune tolerance and gut barrier function [11]. Beyond LAB, Bifidobacterium species generate vesicles with significant immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities. BEVs from Bifidobacterium longum reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production while enhancing IL-10 secretion through dendritic cell conditioning [17]. BEVs from Bifidobacterium bifidum carry a diverse set of proteins, including mucin-binding moonlighting proteins (e.g., GroEL, EF-Tu), stress-related chaperones, and enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism. These components enable adhesion to host mucosal surfaces and may contribute to immune modulation and epithelial barrier maintenance [18,19,20]. Beneficial bacilli also produce highly functional BEVs. Interestingly, proteomic characterization of BEVs from Bacillus pumilus revealed a cargo enriched in peptidases, phosphatases, RNase J, iron transporters, and signal peptides, with composition influenced by culture conditions [21]. Actinobacteria, particularly Streptomyces species, represent another important source of BEVs. Long recognized for their complex secondary metabolism, Streptomyces have recently been shown to secrete vesicles containing antibiotics, siderophores, and bioactive metabolites with roles in inter-microbial competition and soil ecology [15,22]. In environmental microbiomes, BEVs also participate in long-distance signaling and nutrient acquisition. Cyanobacteria produce vesicles carrying proteins, lipids, and metabolites, contributing to ecological interactions and microenvironment modulation [16].

Therefore, the functional characterization of BEVs derived from beneficial bacteria reveals a remarkably diverse molecular repertoire whose biological relevance and biotechnological exploitation can be closely associated with cargo composition, as illustrated in Table 1 with representative examples [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In particular, BEVs transport proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, metabolites, and cell-wall-associated components [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], and this molecular cargo directly underpins their beneficial effects, possibly ranging from immunomodulation and metabolic regulation to stress tolerance and plant growth promotion. In other words, the biological activity of BEVs is inseparable from the nature of their cargo, which enables bacteria to extend their functional reach beyond the cell boundaries. This functional diversity supports their potential as versatile biotechnological platforms for drug and RNA (including sRNA) delivery in inter-kingdom communication, enzyme transport for bioprocessing, vaccine development, next-generation postbiotics, agricultural biostimulants, and plant immunity enhancement. They also exhibit therapeutic promise for various diseases [31,32,33,34]. However, despite these opportunities, major bottlenecks persist, particularly the low BEV production yield, variability in cargo composition, and challenges in scalability and reproducibility for industrial and clinical applications. As detailed in the next paragraphs, BEV secretion varies widely across species and even strains, growth conditions, and physiological states, and, although the main vesiculation pathways have been characterized, the molecular networks driving hypervesiculation remain poorly understood. Addressing these limitations requires a shift from descriptive studies toward process-oriented strategies aimed at improving BEV production and stabilizing cargo profiles.

Table 1.

Molecular cargo of BEVs: representative biological roles and current or emerging biotechnological applications.

2. Genetic and Physiological Factors Controlling Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Production

BEV biogenesis is a genetically regulated process involving multiple pathways that govern membrane remodeling, cargo selection, and BEV release [35,36]. Recent studies have identified genes encoding enzymes, proteases, and regulatory proteins—such as sigma factors and peptidoglycan-modifying enzymes—that significantly influence vesiculation rates [35,36].

Beyond genetic determinants, physiological conditions strongly modulate BEV production. Factors such as growth mode (i.e., biofilm or planktonic cultures) alter vesicle yield and cargo, reflecting adaptive strategies for survival and communication [36,37]. Biofilm-associated bacteria often exhibit enhanced vesiculation and distinct proteomic profiles compared to planktonic cells, with implications for virulence and immune modulation [37].

As described in the following paragraphs, the physiological state of the cell—including bacteriophage infections, nutrient availability and stationary versus exponential growth—affects not only BEV yield but also cargo selectivity, influencing the functional roles of BEVs in microbial ecology and host interactions. Understanding these genetic and physiological factors is critical for elucidating BEV biology and optimizing their use in biotechnology and therapeutic applications.

2.1. Genes Involved in Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Production

Recent efforts have focused on identifying genetic and regulatory targets to increase vesicle production. However, understanding how these modifications influence EV cargo composition and function remains essential for their effective use in biotechnology [38,39].

Genetic manipulation in Gram-negative bacteria has revealed multiple strategies to enhance BEV production. The Tol-Pal system, which maintains outer membrane (OM) integrity, represents a prominent target. Disruption of these components markedly increases vesiculation; for example, deletion of tolB in Buttiauxella agrestis yielded a 17-fold increase in vesicle release, primarily at cell poles and division sites [40]. Similarly, tolA deletions in E. coli K-12 BW25113 and BL21(DE3) produced 4- and 13-fold increases, respectively [41,42], whereas a tolR mutation in E. coli Nissle 1917 enhanced vesiculation by 52-fold [43]. Notably, these hypervesiculating mutants exhibit heterogeneity in vesicle size and morphology, including multilamellar and irregular structures, potentially affecting vesicle function and cellular interactions [40,41,43].

Another approach to increase hypervesiculation is the overexpression of the outer membrane protease OmpT. In enterohemorrhagic E. coli, OmpT upregulation induces an approximately 40-fold increase in BEV production, presumably by reducing stabilizing contacts between the OM and peptidoglycan [44]. However, this strategy alters vesicle architecture, producing smaller vesicles with reduced protein and lipid content, highlighting the trade-off between vesicle quantity and compositional fidelity. Similarly, deletion of outer membrane porin oprF or lipoprotein oprI in Pseudomonas KT2440 strains enhances vesiculation by up to 4-fold, but with varying effects on growth, membrane integrity, and cytosolic protein incorporation [38]. Importantly, co-overexpression of gpsA or accABCD in the ΔoprF background restored membrane integrity by 37% while preserving vesicle output, underscoring the critical role of membrane biosynthesis in hypervesiculating strains [38].

Genome-scale and computational approaches have further refined BEV engineering. Indeed, the deletion of four genes (poxB, sgbE, gmhA, and allD) identified through metabolic network simulations increases vesicle production without compromising growth. Single-gene knockout ΔsgbE yielded up to a 10-fold increase in BEV output compared to the parental JC8031 strain. Lipidomic analysis confirmed that BEV integrity was maintained, demonstrating the feasibility of combining in silico design with experimental validation for scalable BEV production [25].

Lipoproteins also play a critical role in Gram-negative hypervesiculation. The outer membrane lipoprotein NlpI, which modulates peptidoglycan cross-linking, restricts BEV formation; its deletion increases BEV release by 2- to 6-fold due to ~40% reduction in Lpp–PG cross-links [45,46,47]. Double knockouts, such as ΔmlaEΔnlpI in E. coli Nissle 1917, further elevate BEV output (~8-fold) and produce multilamellar BEVs, reinforcing the link between envelope destabilization and hypervesiculation [48]. Genome-wide screens have also confirmed the complexity of BEV regulation, showing that 171 genes in the Keio deletion collection influence vesicle production, including those involved in oxidative stress defense and LPS biosynthesis. These observations highlight the connection between envelope integrity, stress response, and vesiculation [49].

Disruption of stress-response and envelope-modifying genes such as degP, rfaC, and the gene encoding SRRz/Rz1 lysis module further shows that hypervesiculation often results from envelope destabilization, and multi-gene interventions produce stronger effects than single-gene deletions [50]. Similarly, the MLA pathway in Campylobacter jejuni controls vesicle release and reacts to environmental cues such as bile salts, linking host signals to BEV production [51]. Cytoskeletal factors, including RodZ and MreB, also influence BEV biogenesis, with RodZ loss increasing vesicle output over 50-fold and partial MreB repression producing an 8-fold increase [52]. This suggests that cell shape and structural integrity are key for vesiculation.

Genetic manipulation in Gram-positive bacteria remains less advanced, with BEV biogenesis largely dependent on active metabolism. Regulatory factors such as SigB in Listeria monocytogenes and CovRS in Streptococcus pyogenes have been implicated. At the same time, in filamentous actinobacteria, vesicles often originate at hyphal tips, possibly driven by mechanical stress [53]. As shown in Streptomyces sp. Mg1, ΔlnyI mutants produce only ~27% of vesicles relative to wild type, primarily affecting smaller vesicle populations (<100 nm), demonstrating the connection between specialized polyketide metabolism and vesiculogenesis [27]. In Staphylococcus aureus, deletions of sle1 reduce BEV yield and vesicle size, with complementation restoring production, while Δlgt mutants increase vesicle release 2- to 3-fold with altered protein profiles [30,34,54,55].

In B. subtilis, autolysin-mediated stress pathways are central to BEV production. Exposure to surfactin ethanol stress increases vesicle output ~10-fold in wild-type cells. In contrast, ΔsigD mutants produce ~50% fewer BEVs, and ΔlytCDEF mutants show almost no autolysis and a 6.5-fold reduction in vesicles, emphasizing the cooperative requirement of multiple autolysins [56]. Another protein involved in vesicle recovery is Sfp, a 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferase essential for surfactin biosynthesis. Indeed, functional sfp strains produce very few recoverable vesicles, while sfp-deficient strains display a significant increase, illustrating strain-specific differences in BEV yield [57]. Similarly, in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, activation of the Pst/SenX3–RegX3 system in ΔpstA1 mutants results in a 15-fold increase in vesicle release, independent of VirR or ESX-5, highlighting alternative regulatory pathways for BEV biogenesis [58].

These studies demonstrate that hypervesiculation can be achieved by targeting envelope-stabilizing elements, adjusting stress-response pathways, and manipulating cytoskeletal or cell wall components across bacterial species. However, increased BEV production often comes with envelope stress, growth defects, and changes in vesicle structure, raising concerns about safety, reproducibility, and functional accuracy.

2.2. Production of Bacterial Extracellular Vesivles Can Vary Among Different Strains of the Same Species

Due to the role played by single genes in BEV production, their yield and cargo can vary among strains of the same species [28,36,52,59,60]. An evolutionary study highlighted that vesiculation can be a dynamic phenomenon: E. coli clones derived from a Long-Term Evolution Experiment (LTEE) after 50,000 generations produced vesicles of varying sizes and with differential OmpA and LPS composition, emphasizing the influence of accumulated mutations [61]. Although a very limited number of studies focus on this aspect, a combination of complementary strategies can be adopted aimed at reducing strain-dependent variability.

Using certified and traceable strains from reference collections (e.g., ATCC, DSMZ, etc.) can ensure homogeneity of experimental stocks and reduce the risk of genetic divergence [62,63,64] (https://www.atcc.org/resources/technical-documents/reference-strains-how-many-passages-are-too-many, accessed on 16 January 2026). In addition, limiting subcultures and using frozen master stocks can help preserve phenotypic stability and production consistency over time (ATCC technical documents). These approaches minimize phenotypic drift and ensure reproducibility across labs and studies [65].

Screening of multiple strains obtained by transposon insertion allows the identification of isolates with characteristic vesiculation profiles [35,36]. This finding suggests that complete genomic sequencing of strains allows the correlation of mutations or genetic variants to specific vesiculation behaviors, improving traceability and functional interpretation of data [62,63]. Finally, rigorous control of growth conditions—as detailed below—and regular phenotypic monitoring of BEV production—including culture medium, growth phase, and cell density—are essential to maintaining high standards of comparability between experiments [1,65].

2.3. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Production Yield in Static Versus Planktonic Cultures

The growth conditions of microorganisms are key determinants in the production of BEVs. Static cultures strongly differ from planktonic cultures, primarily in terms of growth conditions, particularly the availability of oxygen and nutrients, as well as the spatial distribution of cells within the culture medium. In static cultures, no agitation is applied: the liquid medium remains still, and cells tend to settle at the bottom or adhere to the vessel surfaces, forming biofilms. Oxygenation is limited, and microbial growth is slower and more heterogeneous, as gradients of nutrients and oxygen can develop within the culture [66]. Conversely, in planktonic cultures, the medium is continuously agitated and aerated, allowing cells to remain uniformly suspended and promoting a more efficient oxygen exchange. As a result, growth is faster and more homogeneous, making these conditions ideal for quantitative studies. Consequently, BEV production also varies significantly depending on the growth conditions of microorganisms. BEVs produced under planktonic conditions differ in both quantity and protein profile compared to those obtained under static conditions. Moreover, dynamic systems can enhance BEV production: it has been shown that BEV production by N. meningitidis in stirred tank reactors operated in continuous mode increases ninefold compared to batch cultures [1]. Conversely, BEVs produced by V. cholerae under static conditions (i.e., from biofilms) promote biofilm formation compared to BEVs derived from planktonic cultures [67]. In the study by Johnston et al. (2023) [68], the DNA content of BEVs produced by P. aeruginosa grown under planktonic and biofilm conditions was evaluated. BEVs derived from biofilms were smaller but contained higher amounts of plasmid DNA and proved more efficient in the transfer of resistance genes. In contrast, BEVs produced under planktonic conditions were more effective at encapsulating and protecting plasmid DNA from DNase-mediated degradation [68]. Another study also examines how P. aeruginosa-derived BEVs from planktonic and biofilm conditions differ both quantitatively and qualitatively. The biofilm pellet was larger and more gelatinous compared to that of planktonic cells. It was demonstrated that BEVs from biofilms are generally smaller and more gelatinous, contain higher amounts of LPS per unit weight, and exhibit functional properties such as proteolytic activity and the ability to bind antibiotics [69]. These findings are in accordance with the results of Kanno et al. (2023) [36] that revealed biofilm-specific regulation and distinct gene expression patterns, with surface attachment promoting vesicle release and underscoring the role of biofilm development in vesiculation.

It is also evident that both the quantity and quality of BEVs produced, and consequently their optimal yield for biotechnological and industrial applications, are highly dependent on the microbial species used. However, these parameters are not static; they vary significantly according to growth conditions and the diverse physiological, environmental, and metabolic stimuli to which the cells are exposed. In other words, achieving high BEV yields with desirable functional properties requires a deep understanding of microbial behavior under different conditions and a targeted optimization of the factors that regulate their production.

2.4. Physiological States Affecting Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Production Yield and Cargo

The production and content of BEVs are strongly influenced by the physiological state of the parent cell. The growth phase and metabolic conditions represent key factors in determining both the quantity of vesicles released and their molecular composition.

Numerous studies have shown that the stationary and late-exponential growth phase often represents the optimal time for the collection of BEVs [70,71,72]. During these phases, bacterial cells undergo physiological stress due to limited nutrient availability and the accumulation of waste products or secondary metabolites. These internal signals induce extensive changes in gene regulation and signaling pathways, resulting in enhanced BEV release and selective modulation of BEV protein and lipid [73,74]. The optimal timing for isolating BEVs is at the end of the exponential growth phase or early stationary phase, as this maximizes yield and preserves vesicle bioactivity and purity. For example, P. aeruginosa BEVs change their properties during the transition to the stationary phase. In this phase, BEVs appear to play a greater functional role in cell-to-cell communication. The focus is not only on the quantity of BEVs but also on their quality and functionality, as stationary-phase BEVs are more active, highly charged, and more involved in signaling and cellular interactions [75].

BEV production is growth phase-dependent: bacteria release the highest quantity and most bioactive vesicles during the late exponential or early stationary phase. It was also shown that extending culture time beyond this does not proportionally increase yield and may alter vesicle cargo or increase contaminants. In this study using Lactobacillus acidophilus and E. coli Nissle, the authors found that BEV release increased only modestly, about 1.5-fold, when culture time was extended from 24 to 48 h. They also noted that doubling the culture duration did not produce a proportional increase in BEV yield, because bacterial growth slows after the exponential phase and approaches saturation, limiting further vesicle production [76].

During biofilm development, P. aeruginosa releases two distinct types of extracellular vesicles that play opposite roles. BEVs produced during the exponential growth phase enhance bacterial attachment, promote biofilm formation, and support population expansion. In contrast, BEVs secreted during the survival or death phase help bacteria adapt and survive in harsh environments by aiding nutrient and iron acquisition. However, in iron-rich conditions, these same vesicles become toxic, triggering iron-dependent cell death through oxidative stress and ROS production, thereby inhibiting biofilm [77].

The molecular composition also changes in a growth phase-dependent manner. Indeed, BEVs isolated at different growth phases show significant differences in protein, lipid, and nucleic acid content, as well as immunogenicity and functional properties. For example, Helicobacter pylori BEVs isolated from the late-exponential phase contain higher levels of protein, DNA, and RNA than BEVs isolated from early-exponential and stationary growth phases [74]. Also, the amount of RNA contained in BEVs isolated from P. aeruginosa decreases during the transition to the stationary phase, while the RNA species remain constant. This indicates that RNA export via BEVs is a transient phenomenon, occurring mainly during the late exponential phase [78]. In summary, the bacterial growth phase is a critical determinant of BEV production.

Most studies agree that the optimal window for isolation occurs at the end of the exponential phase or the onset of the stationary phase, when bacteria experiencing physiological stress release the highest amount of functionally active vesicles. Extending the culture period beyond this point does not substantially increase yield and may instead alter vesicle cargo or introduce additional contaminants. Therefore, precise timing of BEV collection is essential to obtain abundant, bioactive, and high-quality vesicles, ensuring maximal reliability and efficacy in experimental and biotechnological applications.

2.5. Bacteriophages as Modulators of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Production

Bacteriophages represent a biotic factor capable of significantly modulating the production of BEVs. Several studies have demonstrated that exposure to phages acts as a potent stress signal that increases BEV production, as phage infection is one of the conditions under which bacteria intensify vesicle release to mitigate viral predation [79]. Beyond enhancing their overall secretion, phages can alter both the quantity and the molecular composition of BEVs, reshaping their lipid, protein, and nucleic acid cargo [79]. This indicates that bacteriophages directly influence the cellular pathways responsible for BEV formation and packaging and may reprogram vesicle output during infection. The finding that a prophage-deficient strain exhibits reduced BEV production supports a role for prophage in BEV biogenesis [80]. Additionally, in Gram-negative bacteria, phage infection can trigger endolysin-mediated explosive cell lysis, leading to the massive release of distinct vesicle subtypes such as OIMVs and explosive outer membrane vesicles (EOMVs), which derive from the abrupt rupture of the bacterial cell [79]. These explosive events constitute a highly productive mechanism of BEV generation under phage attack and contribute substantially to the vesicle pool found in phage-exposed bacterial populations.

2.6. In Vivo Dynamics of BEVs: Biodistribution and Biological Effects

BEVs can be naturally produced by bacteria residing in the host microbiota and by pathogenic bacteria [81].

In plant systems, BEVs from beneficial rhizobacteria can be absorbed by roots and translocated to aerial tissues, influencing plant development and growth, stimulating immunity and enhancing resistance to pathogens [82]. For example, Sinorhizobium fredii produces OMVs whose composition and function shift under symbiosis-mimicking conditions that can be simulated by genistein exposure. Genistein-induced OMVs trigger soybean root hair deformation, activate early nodulation genes, and suppress plant defense responses [83].

In animals, growing evidence shows that BEVs act as key mediators of host–microbe communication by delivering effector molecules that modulate signaling pathways and cellular functions. Across gut, lung, skin, and oral cavity, BEVs influence epithelial responses, shape immune activity, and interact with the central nervous system, underscoring their broad relevance to health and disease [84]. In particular, BEVs released by gut bacteria have gained increasing attention as carriers of bioactive and signaling molecules exerting potential regulatory roles in gut–organ axis diseases, including disorders of the central nervous system, organs, cardiovascular system, and metabolism [85]. BEVs can enter the host systemic circulation and cross major biological barriers, including the intestinal epithelium, vascular endothelium and, in some instances, the blood–brain barrier [86,87,88,89].

Exogenous administration of BEVs—whether oral, intraperitoneal, or intravenous—results in their selective accumulation in specific organs, as demonstrated by in vivo biodistribution studies [87,90]. As an example, after systemic or mucosal administration, they accumulate preferentially in the liver, spleen and lungs [90]. These tissue-specific biodistribution patterns have been demonstrated using lipophilic fluorescent dyes (e.g., DiD) and ex vivo imaging, confirming the capacity of BEVs to reach target tissues following oral or intraperitoneal delivery [89]. Indeed, there are different imaging technologies for in vivo tracking of BEVs, comprising optical-based imaging using fluorescence (FLI) and bioluminescence (BLI), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), and nuclear imaging—including SPECT and PET—each with its own advantages and limitations [90]. These approaches enable non-invasive assessment of BEV absorption, distribution, and clearance, providing quantitative pharmacokinetic information valuable for therapeutic development.

Overall, although we are still in an early stage of investigation, an increasing number of in vivo studies demonstrate that BEVs can be targeted to specific tissues in both animals and plants, where they modulate physiological and immune functions. Their biodistribution and biological effects are shaped by composition, amount, and district of production/route of administration. Together, these findings support the rational design of safe and effective biotechnological applications based on BEVs.

3. Strategic Variables to Modulate the Production Yield and Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles

Understanding the physiological mechanisms of BEV biogenesis and release is crucial to exploit their enormous biotechnological potential. BEVs are not a passive product of, for example, cellular stress; their release is a highly regulated process. Indeed, in response to environmental, chemical, or biological stresses, bacteria can modulate BEV release as a multifunctional adaptive strategy. BEVs may allow for: the expulsion of misfolded proteins and toxins; modulation of the synthesis of biologically active molecules by protecting and concentrating them within BEVs and reducing intracellular accumulation that could limit their biosynthesis; protection against antimicrobial agents, thus contributing to survival in adverse conditions. In pathogens, BEVs can also facilitate evasion of the host immune system and, in all bacteria, promote intercellular communication and the exchange of signaling molecules, making vesiculation a key mechanism of physiological adaptation and metabolic modulation [2,91,92,93,94]. Indeed, experimental evidence shows that different types of environmental and chemical stresses—such as exposure to antibiotics, nutrient depletion, oxidative or redox stress, temperature and pH changes, osmotic stress and the presence of chemical compounds (i.e., solvents, detergents, and chelating agents) increase the release of BEVs in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [91,95]. Culture parameters such as temperature, pH, medium composition, and co-culture can therefore become strategic variables to modulate the biogenesis and cargo of BEVs and optimize yield in either industrial or laboratory fermentation systems [93,96]. The main strategies, involving bacterial genetic manipulation and culture conditions, that can affect BEV yield and composition are illustrated in Table 2 with representative examples.

Table 2.

Effects of genetic manipulation, cellular stresses and culture conditions on BEV production.

3.1. Metabolic Stress Modulates Extracellular Vesicle Production

Metabolic stress can be one of the modulators of BEV production and cargo composition. Controlled nutrient limitation or medium optimization can enhance BEV release, alter their molecular content, and modify their biological activity in a species-dependent manner. The controlled selection of the growth phase is a crucial tool for obtaining BEVs with reproducible and functional characteristics. Similarly, controlled induction of metabolic stress, through the limitation of specific nutrients (e.g., iron, nitrogen, phosphate) or by modulating culture conditions (e.g., accumulation of secondary metabolites), can be exploited to modulate BEV production toward desired profiles. These strategies allow the replication of environmental stimuli encountered by bacteria in natural or infectious contexts, contributing to both the understanding of the physiological role of BEVs and paving the way for scalable biotechnological applications. Certain forms of metabolic stress, such as nutrient limitation, can induce the production of BEVs as a cellular defense or communication mechanism. Conversely, when metabolic stress becomes too severe, bacterial growth slows markedly and the total BEV yield per culture may decrease, even though the relative production per cell increases. Metabolic stress exerts a dual effect: it stimulates BEV production at the cellular level while reduces overall yield when bacterial growth is strongly limited. BEV production under nutrient stress appears to be an adaptive response aimed at enhancing bacterial survival, facilitating exchange of metabolites—such as nutrients and bioactive compounds—and macromolecules—like enzymes, RNA and DNA- promoting intercellular communication. The effects of isolated amino acids on BEV production have also been documented. Cysteine deprivation induces oxidative stress and triggers BEV release by N. meningitidis. BEVs from N. meningitidis are already used as the basis for meningococcal vaccines, and controlled cysteine depletion may represent a strategy to naturally increase BEV yield while maintaining, or even improving, their antigenic quality [23].

Finally, it has been shown that the absence of certain trace elements in the growth medium can alter the protein composition of BEVs. This study demonstrates that, for B. pumilus, phosphate deficiency changed the protein spectrum of BEVs [21]. BEVs play a role in bacterial iron acquisition, as they may contain iron-binding moieties (siderophores) that scavenge free iron and facilitate delivery to the parental cell. Growth in iron-limiting conditions triggers BEV production for Mycobacterium tuberculosis [97], and pathogenic and commensal E. coli [98]. The accumulation of toxic metabolites can alter vesicle quality by modifying their lipid and/or protein composition. For example, the buildup of hydrogen peroxide and other ROS, arising from disrupted metabolism or toxic accumulation, increases vesiculation in P. aeruginosa [99]. As nutrient limitation can enhance BEV secretion as a stress response, enriching the growth medium can also promote BEV production and release. In particular, enriched or specific nutrient sources (e.g., glucose) can increase BEV yield. For example, bifidobacteria produced the highest BEV yield in glucose-containing media, while the absence of saccharides led to poor growth and low BEV production [100]. For instance, supplementing E. coli Nissle cultures with 1% glycine resulted in a 69-fold increase in BEV protein content and a 51-fold increase in lipid content, while simultaneously decreasing lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxin activity [101].

The type of growth medium is also crucial and specific to the microorganism in question, affecting not only the yield and composition of BEVs but also their potential biological activities. For example, Propionibacterium freudenreichii grown in cow milk ultrafiltrate produced more abundant, smaller BEVs with distinct protein cargo and stronger anti-inflammatory activity compared to yeast extract lactate medium [112].

Controlled metabolic stress induction is a well-established method to enhance BEV production and modify their cargo. However, the response is dependent on the type of stress, the bacterial species, and the environmental conditions. Optimal management of nutrient availability and metabolic stress is therefore crucial for maximizing both the production and the quality of BEVs.

3.2. Impact of Antibiotics on Extracellular Vesicle Release

Antibiotic exposure is one of the most known stimuli for BEV biogenesis. In several Gram-negative and Gram-positive strains, sub-lethal concentrations have been observed to induce envelope-stress responses that promote membrane curvature and budding, thereby increasing vesicle release. In E. coli, exposure to antibiotics at 2-fold the minimum inhibitory concentration (2× MIC) or clinical concentrations induces a dose-dependent increase in BEV release, with β-lactams stimulating 3–5-fold higher secretion compared to untreated controls and 2–4-fold higher secretion compared to quinolones and aminoglycosides [102]. The effect of antibiotic exposure can also influence the chemical-physical characteristics, composition, and dynamics of BEVs. In the tigecycline-resistant E. coli 47EC strain, sub-inhibitory concentrations (1/2× or 1/4× MIC) of gentamicin, meropenem, ceftazidime, chloramphenicol, tigecycline, ciprofloxacin, polymyxin, rifaximin and mitomycin C significantly increase the secretion of OMVs, which have larger dimensions and a lower zeta potential than the untreated control [103]. In E. coli K12, sub-MIC doses of ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol were shown to significantly alter vesicle dynamics, increasing vesicle production, diffusion rate, and distance, as well as promoting membrane detachment. These results indicate that antibiotic-induced stress acts as a signal that stimulates vesicle release and dispersion, which may mediate stress communication between cells, contributing to adaptation and potentially antibiotic tolerance or resistance [113]. In three multidrug-resistant clinical strains of H. pylori, antibiotic-induced stress alters the secretion and physicochemical characteristics of vesicles in a strain- and antibiotic-dependent manner. Treatment with 1/4× MIC of metronidazole or levofloxacin increases vesicle production and significantly alters their fatty acid profile, while clarithromycin does not induce significant changes. A conserved process of selective enrichment of BEVs in C17:0 fatty acids, with a reduction in C14:0, C18:1, and C19c:0, was also highlighted, indicating a targeted control of lipid composition as an adaptive response to antibiotic stress. Thus, antibiotic exposure alters the lipid profile and physicochemical properties of BEVs, implying a membrane reorganization and an adaptive response aimed at antimicrobial tolerance [104]. The effect of antibiotic exposure on vesiculation has also been demonstrated in Gram-positive bacteria; in methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), sub-MICs of ampicillin increased vesicle secretion up to 22.4-fold compared to controls, also enriching the cargo in β-lactamases [105]. In the Streptomyces genus, available data are more limited but highly suggestive. In Streptomyces sp. Mg1, mutation of the lnyI gene, involved in the biosynthesis of the polyketoid linearmycin, resulted in a significant reduction in BEV release, highlighting a functional connection between vesiculation and antibiotic synthesis [27]. The mechanism underlying the stimulatory effect of antibiotic exposure appears to be related to the antibiotic target: agents that impair peptidoglycan synthesis or membrane stability (β-lactams, glycopeptides, polymyxins) induce a more marked response than those with intracellular targets (quinolones, macrolides), consistent with the activation of envelope-stress circuits, the formation of membranous curvature, and the expulsion of damaged components. Overall, studies converge in considering sub-MIC antibiotic exposure as a regulatory signal that controls both the quantity and composition of vesicles, with implications ranging from detoxification and intercellular communication to the transfer of defense molecules and resistance genes [114]. From a biotechnological perspective, a detailed understanding of these mechanisms in Streptomyces, Bacillus, and other industrial producers may allow us to exploit controlled antibiotic stress as a tool to increase the yield and functional loading of BEVs, optimizing natural delivery systems for metabolites, enzymes, or bioactive molecules.

3.3. Physicochemical Stress as Modulators of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Production

Physicochemical stresses can modulate vesiculation and influence cargo composition.

In Salmonella typhimurium, for example, the outer membrane protein PagC contains a pH-sensitive motif that regulates OMV release through protonation-dependent conformational changes. At acidic pH, protonation of this motif promotes membrane bending and increases vesiculation [106].

Growth of H. pylori under acidic conditions reduces the quantity and size of OMVs produced. However, vesicles generated under these conditions exhibit increased protein, DNA, and RNA content compared to those produced at neutral pH. Proteomic analysis revealed significant differences between the proteomes of OMVs and those of parent bacteria, with a selective enrichment of beta-lactamases and outer membrane proteins in the vesicles, indicating that growth conditions influence not only yield but also OMV composition [107]. In general, in Gram- negative bacteria the acidic environment can induce lipid rearrangements in the outer membrane, such as lipid A modifications, which promote vesicle stabilization and budding, according to models of adaptation for membrane integrity [94].

Temperature is another key factor that significantly affects both the yield and the molecular composition of BEVs. For example, in S. aureus, even moderate temperature variations significantly influence vesicle biogenesis and content. BEVs produced at 40 °C show an enrichment in virulence factors and a higher concentration of proteins and lipids, while BEVs produced at 34 °C exhibit greater protein diversity and RNA content and are more cytotoxic to macrophages, highlighting that temperature modulates both vesicle composition and interaction with host cells [108]. The case of Serratia marcescens is interesting, as it releases a high quantity of OMVs at 22 and 30 °C, while at 37 °C, the production of OMVs is almost zero [109]. In E. coli degP mutants, vesiculation increases in response to elevated temperatures that favor the accumulation of misfolded proteins, suggesting that OMV production may be modulated by temperature as a stress adaptation mechanism [110].

Stress exerted by chemicals also has significant effects on vesiculation. Exposure to oxidative stress by H2O2 in enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) showed selective packaging: outer membrane lipoproteins were preferentially exported into OMVs, while integral proteins were retained, suggesting a “disposal” mechanism for oxidizable proteins [111]. In P. aeruginosa PA14, exposure to ~250 μM H2O2 increased vesicle production by ~2.7-fold compared to the untreated control [99].

In Gram-negative bacteria, the use of EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), which chelates the Ca2+ and Mg2+ cations that stabilize the electrostatic bridges of LPS, promotes lateral repulsion of phospholipids and unstable microdomains. In E. coli and Salmonella enterica, EDTA induces the loss of components and fragments of the outer membrane [115,116]. In N. meningitidis, buffers containing 10 mM EDTA significantly increase OMV release [23]. For Gram-positive bacteria, there is no direct evidence that EDTA stimulates BEV biogenesis. However, chemical treatments can often be nonspecific and/or strongly dependent on strain and experimental conditions. For example, in S. aureus, BEVs and their activity persist after washing with 10% hypochlorite, while the use of EDTA causes their removal from the substrate and the elimination of their biological activity. Consequently, the use of chelators requires caution to avoid loss of vesicle integrity and artifacts in their characterization [117].

These examples demonstrate that combining environmental, chemical, and metabolic stresses represents an effective and versatile strategy for increasing BEV yields and modulating cargo. In experimental designs, it is advisable to explore different combinations and exposure times, evaluating not only quantities but also protein, lipid, and functional composition, to optimize production for biotechnological applications.

4. Fermentation and Process Optimization Strategies for Extracellular Vesicle Production

Efficient production of BEVs at an industrial scale requires a holistic approach that integrates upstream and downstream process optimization. Beyond the genetic and physiological determinants of vesiculation, fermentation strategies play a pivotal role in maximizing yield and ensuring cargo consistency. Key factors include the composition of the culture medium, which influences metabolic activity and vesicle biogenesis; operational parameters such as aeration, cell density, and harvest time, which affect both productivity and vesicle integrity; and the choice of bioreactor mode—batch, fed-batch, or continuous—each offering distinct advantages for process control and scalability. Finally, isolation and purification steps are critical for achieving high-quality BEVs suitable for therapeutic or biotechnological applications, requiring methods that balance recovery efficiency with preservation of vesicle functionality. All these issues highlight the intrinsic heterogeneity of BEVs that complicates their analysis and exploitation, underscoring the need for transparent reporting, clearer best practices, and targeted guidance to address existing knowledge gaps and advance BEV research and industrial applications [6,65]. The research on BEVs has a significantly shorter history than that of eukaryotic EVs (EEVs), and many aspects of BEV biogenesis and heterogeneity remain unclear. While the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) guidelines, such as MISEV [118], have substantially improved methodological rigor and reporting standards for EEVs, their applicability to bacterial extracellular vesicles remains a matter of debate in the scientific community. Indeed, BEVs exhibit distinctive biological characteristics, different biogenesis pathways, and contaminants that are not fully addressed by current guidelines, highlighting the need for BEV-specific adaptations, standardization experiments, and targeted recommendations to enable reproducibility, scalability, and quality control.

Filling these gaps through transparent reporting, standardized comparative studies, and guidelines specifically tailored to BEVs will be essential to advance both fundamental research and the safe and reproducible commercialization of BEV-based products.

The following sections explore these aspects in detail, highlighting how medium formulation, fermentation dynamics, and downstream processing converge to optimize BEV production.

4.1. Optimization of the Culture Medium: Rich and Defined Medium

The production and purity of BEVs are significantly impacted by the medium selection. Media formulations, based on their composition, modulate bacterial growth and their metabolic activity, including BEV production [119] (Table 3). These effects have been demonstrated across multiple bacterial species, including E. coli, N. meningitidis, and P. aeruginosa, where nutrient composition modulated vesicle lipid content, endotoxin levels, and overall purity [120]. Careful medium selection is therefore critical for optimizing the balance between BEVs quantity and quality, particularly in applications requiring high-purity vesicles, such as vaccines, therapeutics, and biotechnological products [121]. Using a rich and full medium (such as whole broth cultures) encourages cell growth [122]; hence, the BEV concentrate is more contaminated by media proteins and metabolites. Refs. [123,124], for instance, point out that a “full-strength broth” product can include substantial broth components, considered contaminants, that lower the purity of the BEVs collected. Final purity is essential for BEV production, in contrast to conventional fermentations targeting metabolites or biostimulants, where quantitative yield is prioritized even at the expense of residual contaminants [118]. On the other hand, the components in the final test can be better controlled by using a specified medium [65] showed that N. meningitidis BEV differ among each other in their protein profiles depending on the medium (e.g., MC.6M vs. Frantz), highlighting the medium’s influence on BEV composition. Defined or minimal media are used for BEVs to minimize bulk-contaminated effects, while rich media are often used for fermentations involved in biostimulants production (enzymes, antibiotics, bacterial hormones, etc.), in which lower product purity is widely accepted [125,126]. Chemically defined media allow for tighter control over nutrient composition, producing BEVs with more consistent proteomic and lipidomic profiles and reduced contamination, although yields may be lower [31]. BEV production can be increased by regulating bacterial growth, increasing the accumulation of components in the bacterial outer membrane, changing the fluidity of the cell membrane, and reducing the degree of cross-linking of peptidoglycan [2].

Table 3.

Comparison of BEV characteristics under cultivation in rich versus minimal media.

4.2. Fermentation Parameters: Aeration, Cell Density, Harvest Time

High dissolved oxygen tension can boost vesicle production, making aeration a crucial factor. According to Gerritzen et al. [131], N. meningitidis produces three times as many vesicles when oxygen saturation is increased from 30% to 100%. Highly aerated fermentations can increase vesicle release and oxidative stress without inhibiting development. Cell density is another leading parameter that strongly influences bacterial vesiculation: fed-batch or continuous fermentations strive for high densities to boost volumetric yield, but they also need to carefully regulate nutrients and oxygen to maintain cell viability [132]. Lastly, the harvest period needs to be optimized because if the culture is kept in the stationary phase for too long, extracellular proteases that break down BEV proteins may be released. Dai et al. [65] suggest that extracellular proteases secreted during the stationary phase may degrade vesicle proteins, contributing to batch-to-batch variability in vesicle proteome profiles depending on the time of harvest. Therefore, harvesting often takes place in the late log or early stationary phase to maximize the number of BEVs before degradation [133].

4.3. Bioreactor Operation Modes and Dynamics

Various bioreactor operation strategies are employed to optimize the total yield of BEVs. Batch fermentations are simple to operate but they only produce a small amount of BEVs due to toxin accumulation and limited resources. In fed-batch operations, on the other hand, nutrients (carbon, salts, etc.) are delivered gradually, sustaining longer cell growth and resulting in significantly higher densities compared batch vs. batch-refeed (a kind of semi-continuous) systems, showing that batch-refeed systems produce 3× more BEVs than pure batch [134]. Despite the demonstrated benefits of batch-refeed strategies in eukaryotic EV production, there is currently no published evidence of similar methods being applied to bacterial extracellular vesicle production, highlighting a gap in this field. Stationary state in fermentation conditions can be more easily maintained, controlled and adjusted on demand [135]. In general, dynamic processes (fed-batch or continuous) are preferable when maximizing the final BEV titer is desired, keeping fermentation conditions under control and minimizing variations between batches.

4.4. Isolation and Purification Strategies to Increase BEV Yield and Quality

One of the main challenges in the biotechnological application of BEVs is the difficulty in obtaining large, homogeneous, and reproducible preparations. BEVs are generally produced in limited quantities, and most isolation procedures require the use of large culture volumes to recover even modest quantities of sample [29,136,137]. Furthermore, the production of BEVs is often characterized by a marked heterogeneity in terms of size, density and cargo, and this can also lead to significant differences between preparations obtained from the same strain [22,26,138,139,140]. A further critical issue is obtaining BEV preparations free of soluble proteins, cellular fragments, and macromolecular complexes, which complicate cargo standardization, particle number quantification, and overall preparation quality assessment, thus limiting potential biotechnological applications. The choice and/or combination of isolation methods (e.g., ultracentrifugation, density gradient, filtration, size-exclusion chromatography, affinity chromatography) directly influences the efficacy and reproducibility of downstream experiments [141,142]. Isolation and purification are two distinct but complementary steps in BEV sample preparation to obtain high-quality samples. The isolation phase includes the initial steps required to separate BEVs from the culture medium, removing whole cells and debris. Purification, on the other hand, aims to eliminate residual contaminants such as soluble proteins and aggregates that are not removed by the isolation steps. This phase is essential to ensure that the final preparations are pure and homogeneous, conditions necessary for higher-quality downstream analyses such as omics analysis. Furthermore, purification reduces artifacts due to contaminants, ensures greater reproducibility between batches, and is suitable for the use of BEVs in biotechnological or therapeutic applications where the presence of contaminants could interfere with the functionality, structural integrity, and safety of the product [97,143]. However, current purification strategies present significant limitations, such as reduced yield, aggregation, or structural damage. Furthermore, purification protocols require lengthy procedures, expensive instrumentation, and specialized technical expertise, factors that can limit the scalability and applicability of the methods in biotechnological or therapeutic contexts [31,144].

Among isolation techniques, ultracentrifugation (UC) is considered the “gold standard” for BEV purification. After preliminary removal of cells and debris with low-speed centrifugation, the supernatant is subjected to ultracentrifugation, typically 100,000–200,000× g for 1.5–2 h, to obtain a pellet of BEVs [128,145]. UC effectively concentrates BEVs but generates a heterogeneous population because separation occurs primarily based on sedimentation velocity, which depends on size and density, without distinguishing subtypes with similar biophysical characteristics. To increase purity, UC can be combined with density gradient ultracentrifugation (DGUC), which instead allows separation of vesicles based on their flotation density, reducing contaminants such as protein aggregates or cellular fragments [128]. However, DGUC requires longer processing times, greater technical complexity, and larger sample volumes, often resulting in lower yields than simple UC. Both methods require sophisticated instrumentation and advanced expertise, limiting scalability for biotechnological or therapeutic applications. In summary, UC and DGUC represent fundamental tools to obtain concentrated and relatively pure BEV preparations, but they must be balanced between yield, purity and operational convenience, often in combination with other strategies (filtration, chromatography) to ensure reproducible results suitable for functional or omics studies.

Alternatives to UC and DGUC are membrane-based approaches such as tangential flow filtration (TFF). TFF reduces the clogging typical of dead-end filtrations thanks to the tangential flow and allows for the processing of liters of sample in relatively short times, maintaining low mechanical impact on the vesicles and limiting aggregation phenomena that can occur during UC [142,146]. However, TFF alone does not guarantee the complete removal of soluble proteins, aggregates, or other similarly sized particles, and may result in loss of vesicles due to membrane adsorption or mechanical stress, necessitating a subsequent purification step [147,148]. Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), on the other hand, is a gentle technique that allows BEVs to be isolated while preserving their integrity and obtaining highly pure fractions. Separation occurs primarily based on size: larger vesicles rapidly elute through the column matrix, while soluble proteins, aggregates, and cellular fragments penetrate the pores and are retarded, thus allowing contaminants to be eliminated without applying high centrifugal forces that could damage the vesicles [149,150,151]. Despite its advantages, the SEC method has some limitations: column capacity is often limited, processing times are long, and collected fractions are diluted, sometimes requiring an additional concentration step. To overcome these limitations, SEC can be combined with TFF: TFF removes debris and aggregates before SEC, increasing throughput and reducing vesicle loss. SEC, in this context, ensures final purification and homogeneity of fractions, allowing for scalable, reproducible, and high-quality preparations [152,153].

Despite growing interest in scalable workflows, the documented use of alternative strategies such as TFF or SEC for BEV isolation remains limited and, in the specific case of BEVs, is even rarer, with most protocols continuing to rely almost exclusively on ultracentrifugation [6]. This highlights the need to develop, implement, and standardize protocols for BEV isolation. In recent years, more modern strategies have been developed to improve purity, yield, or scalability. For example, the combined approach of TFF and High-Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography (HPAEC) enables orthogonal separation based on size and surface charge, reducing contaminants (soluble proteins, flagellin, etc.) and increasing the purity of BEVs from both Gram-negative and Gram-positive strains, with enhanced biological activity reported for BEVs from lactic acid bacteria [143]. Another promising alternative for large-scale production is the precipitation induced by the broad-spectrum antimicrobial epsilon-poly-L-lysine (ϵ-PL), which allows BEV concentration by low-speed centrifugation (10,000× g) without the need for ultracentrifugation, offering a rapid and cost-effective approach [154]. Finally, a chromatographic method based on multifunctional beads (EVscore47) specific for BEVs has recently been described; in E. coli, this approach yielded up to ~11-fold higher recovery and ~13-fold higher purity compared with standard ultracentrifugation [137].

However, it should be noted that many of the newer strategies relying on molecular affinity (surface chemistry, specific ligands, interaction-based membranes) are currently applied to and more fully developed for eukaryotic vesicles, owing to the availability of well-characterized membrane markers. In BEVs, the heterogeneity among bacterial species, variability in membrane components, and absence of universal markers make the use of immunocapture or affinity-based methods far less standardized and largely experimental [155,156].

To date, no technique is universally recognized as “superior” for BEV isolation and purification: each method, whether based on size, density, charge, precipitation, or affinity, entails trade-offs between yield, purity, vesicle integrity, throughput, and scalability. This reflects the substantial variability of bacterial strains, growth conditions, and sample preparations, which makes it challenging to standardize a single protocol suitable for all applications.

4.5. Considerations for Buffer Selection and Storage Conditions in Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Preservation

A frequently overlooked aspect in the collection and preservation of BEVs is the choice of resuspension buffer and storage conditions, both of which can significantly influence vesicle integrity, cargo, and functionality. Although many protocols employ buffers such as PBS or DPBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, it is reasonable to hypothesize that formulations lacking these ions may provide greater stability for BEVs by reducing electrostatic interactions that promote vesicle aggregation or fusion [157,158]. In parallel, the selection of appropriate cryoprotectants is critical. Non-reducing sugars such as trehalose are widely used to protect vesicles during freezing or lyophilization. Notably, a recent study introduced a thermodynamic approach to load trehalose inside vesicles prior to lyophilization, resulting in significantly improved preservation of RNA and proteins after dehydration [159]. Although developed using mammalian EVs, this strategy offers a potentially applicable model for BEVs as well. Moreover, experimental evaluations of storage protocols indicate that maintaining vesicles at −80 °C is among the most effective conditions for preserving particle concentration and cargo function. A systematic study demonstrated that freeze and thaw cycles at −80 C lead to particle loss, an increase in mean vesicle diameter, and alterations in zeta potential, collectively suggesting vesicle fusion or structural damage [160]. Finally, the lack of standardized protocols for BEVs and the limited data directly comparing DPBS with or without Ca2+ and Mg2+ or assessing different cryoprotectants represent a major gap in the current literature. Establishing systematic studies that evaluate particle number, structural integrity, molecular cargo, and functional activity under different storage conditions is essential to make BEV production and distribution protocols more robust and reproducible.

4.6. Protein Corona of BEVs: An Overlooked Aspect

Recent advances indicate that EVs, like all biogenic nanoparticles, are likely to acquire a protein corona when released into complex biological environments. The corona consists of proteins and biomolecules adsorbed onto the EV surface when exposed to biomolecule-rich environments, distinct from membrane-integrated or luminal components [161,162,163]. Although direct experimental studies explicitly characterizing a corona on BEVs are still lacking, extensive evidence from EEVs demonstrates that extracellular proteins spontaneously adsorb onto vesicle surfaces, forming a dynamically regulated corona that profoundly affects EV identity, interactions, and biodistribution.

Studies have shown that EEVs from mammalian cells immediately bind extracellular proteins after release, generating both a hard corona, composed of tightly bound, slowly exchanging proteins, and a more transient soft corona of loosely associated biomolecules. Therefore, for EEVs, protein corona formation is well documented and significantly influences their properties, cellular uptake, biodistribution, and biological activity. EEVs produced in serum-free cultures lack a corona, which forms rapidly upon serum exposure, with its composition varying with serum type and health status [161,162]. EEVs incubated in plasma acquire specific proteins such as apolipoproteins, complement factors, fibrinogen, and immunoglobulins, detectable by proteomics and microscopy [162]. Functionally, the corona can alter EEV fate; for example, albumin coating on EEVs derived from mesenchymal stem cells modified uptake and biodistribution [164,165]. These findings are relevant to BEVs because the physicochemical drivers—surface charge, membrane composition, exposed lipids and proteins—are conserved across EV types, although BEVs differ fundamentally from EEVs in their biogenesis and molecular composition.

Although BEVs carry intrinsic surface proteins and lipids from the producing organism, it is unclear whether they acquire a host-derived protein corona in biofluids like eukaryotic extracellular vesicles (EEVs). Indeed, BEVs, particularly OMVs from Gram-negative bacteria, naturally expose outer membrane components such as LPS, periplasmic proteins, lipoproteins, and other surface antigens known for their high binding affinity to serum proteins and host factors, providing a favorable interface for corona formation in vivo. Furthermore, recent work on EEV coronas has demonstrated that the corona composition depends strongly on the extracellular environment and on their origin, suggesting that BEVs released into host tissues would similarly acquire distinct coronas that modulate their immunogenicity, uptake, and biological effects.

Collectively, although direct evidence is still to be obtained, the mechanistic principles established in EEV corona biology, together with the known surface architecture of BEVs, strongly support the concept that BEVs may also acquire a context-dependent protein corona that contributes to shaping their functional interactions within microbial communities and during host–microbe communication. Ignoring corona formation may lead to misinterpretation of BEV proteomic profiles and functional roles. While intrinsic cargo is relatively well characterized, host- or environment-derived coronas remain largely unexplored, representing a critical research gap with implications for immunogenicity, virulence, and therapeutic applications.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Despite the growing interest in BEVs as platforms for biotechnological applications—such as drug and nucleic acid delivery, immunomodulation, and plant biostimulation—low production yield and cargo variability remain the primary bottlenecks for industrial and clinical translation [144,166]. Natural vesiculation rates are insufficient for large-scale manufacturing, and variability in BEV composition further complicates standardization. Overcoming these limitations requires complementary strategies at multiple levels: genetic engineering to enhance vesiculation pathways, physiological modulation through stress or nutrient optimization, and bioprocess innovations such as controlled fermentation and shear-stress stimulation [124,167,168].

However, these approaches are often applied in isolation; future progress will depend on integrated, multi-factorial strategies that combine genetic, environmental, and engineering interventions under Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP).

A critical gap remains the lack of quantitative frameworks for predicting BEV yield and cargo quality. Here, omics-driven approaches—including transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—offer powerful tools to map vesiculation networks and identify molecular targets for rational strain design. In this context, emerging spatial transcriptomics technologies, such as the highly multiplexed method described by Sarfatis et al. (2025) [169], represent a transformative opportunity. By enabling single-cell, spatially resolved gene expression profiling in bacterial populations, these techniques could uncover microenvironmental cues and regulatory circuits that govern vesicle biogenesis. Integrating spatial transcriptomics with machine learning and metabolic modeling would allow predictive control of BEV production, facilitating precision bioprocessing and targeted cargo engineering.

In summary, the next decade will likely see a transition from empirical optimization to data-driven, integrated platforms for BEV manufacturing, leveraging advanced omics and spatial technologies to unlock their full potential as standardized, scalable tools for therapeutics, diagnostics, and sustainable biotechnology.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation, F.C., A.G., S.L.S., G.G. and T.F.; writing—review and editing, G.G., T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Commission—NextGenerationEU, Piano Nazionale Resistenza e Resilienza (PNRR), grant number CN00000033.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This research has been financially supported by the European Commission—NextGenerationEU, Piano Nazionale Resistenza e Resilienza (PNRR)—Missione 4 Componente 2 Investimento 1.4—Avviso N. 3138 del 16 dicembre 2021 rettificato con D.D. n.3175 del 18 dicembre 2021 del Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca—CN5 “National Biodiversity Future Center”—NBFC—code n. CN00000033. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Ideogram to generate a raw draft of Figure 1, and Chatgpt (OpenAI) version GPT 5.2 and Microsoft 365 Copilot (GPT-5 chat model) for text editing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EVs | Extracellular Vesicles |

| BEVs | Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles |

| EEVs | Eukaryotic Extracellular Vesicles |

| OM | Outer Membrane |

| OMV | Outer Membrane Vesicles |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| UC | Ultracentrifugation |

| TFF | Tangential Flow Filtration |

| SEC | Size-Exclusion Chromatography |

| HPAEC | High-Performance Anion Exchange Chromatography |

| GMP | Good Manufacturing Practices |

References

- Muñoz-Echeverri, L.M.; Benavides-López, S.; Geiger, O.; Trujillo-Roldán, M.A.; Valdez-Cruz, N.A. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Biotechnological Perspective for Enhanced Productivity. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Schild, S.; Kaparakis-Liaskos, M.; Eberl, L. Composition and Functions of Bacterial Membrane Vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Nomura, N.; Eberl, L. Types and Origins of Bacterial Membrane Vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulkens, J.; Vergauwen, G.; Van Deun, J.; Geeurickx, E.; Dhondt, B.; Lippens, L.; De Scheerder, M.A.; Miinalainen, I.; Rappu, P.; De Geest, B.G.; et al. Increased Levels of Systemic LPS-Positive Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Patients with Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction. Gut 2020, 69, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briaud, P.; Carroll, R.K. Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Functions in Gram-Positive Bacteria. Infect. Immun. 2020, 88, e00433-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Langhe, N.; Van Dorpe, S.; Guilbert, N.; Vander Cruyssen, A.; Roux, Q.; Deville, S.; Dedeyne, S.; Tummers, P.; Denys, H.; Vandekerckhove, L.; et al. Mapping Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle Research: Insights, Best Practices and Knowledge Gaps. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C.; Kuehn, M.J. Outer-Membrane Vesicles from Gram-Negative Bacteria: Biogenesis and Functions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T.N.; Kuehn, M.J. Virulence and Immunomodulatory Roles of Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, S.; Dou, H.; Cheng, T.; Huang, T.; Lv, Z.; Tu, Y.; Shi, Y.; et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Promote Wound Healing via MiR-21-5p-Mediated Re-Epithelization and Angiogenesis. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Zhang, X.; Hao, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Liang, X.; Liu, T.; Gong, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhai, Z.; et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus Gg Derived Extracellular Vesicles Modulate Gut Microbiota and Attenuate Inflammatory in Dss-Induced Colitis Mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.R.; Gonzalez, C.F.; Lorca, G. Internalization of Extracellular Vesicles from Lactobacillus johnsonii N6.2 Elicit an RNA Sensory Response in Human Pancreatic Cell Lines. J. Extracell. Biol. 2023, 2, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini-Giv, N.; Basas, A.; Hicks, C.; El-Omar, E.; El-Assaad, F.; Hosseini-Beheshti, E. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles and Their Novel Therapeutic Applications in Health and Cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 962216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Xiang, X.; Hao, C.; Ma, D. Roles of Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Systemic Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1258860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wei, C.; Pan, C.; Wei, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Genetically Engineered Bacillus subtilis-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Alleviates Ulcerative Colitis by Restoring Intestinal Barrier and Regulating Gut Microbiota. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 512, 162727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]