Abstract

BslA (Biofilm surface layer protein A), a highly hydrophobic lipoprotein from Bacillus spp., self-assembles at fluid interfaces to form a crystalline film that reduces surface tension. In this study, we selected Pichia pastoris as a eukaryotic system for expressing recombinant BslA identified in Bacillus paralicheniformis BL-1. The secretory expression of recombinant BslA in the P. pastoris GS115 strain under the AOX1 promoter was confirmed in shake-flask cultivation. Next, two fed-batch fermentation strategies, constant dissolved oxygen strategy (DO-stat) and oxygen-limited fed-batch (OLFB) strategy, in a 5 L scale, were compared. The DO-stat process led to late-stage cell death and product degradation, limiting yields. Switching to the OLFB process by removing the glycerol feeding phase mitigated this issue, allowing extended fermentation and increasing the final recombinant BslA concentration to 657 mg/L. This study establishes P. pastoris with an OLFB strategy as an effective system for secreting recombinant BslA protein, providing a basis for future industrial-scale production.

1. Introduction

Biosurfactants are a class of natural surface-active molecules metabolically produced by microorganisms (such as bacteria and yeast) or plant and animal cells, featuring an amphiphilic structure [1]. Compared to traditional chemical surfactants, they offer core advantages such as environmental friendliness, biodegradability, and low toxicity. This not only addresses the urgent need for sustainable chemical products but also enables their safe application in sensitive fields, including environmental remediation (e.g., biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbon pollution) [2], agriculture (as green pesticide adjuvants) [3], food [4], pharmaceuticals [5], and cosmetics [6]. Furthermore, employing synthetic biology to engineer microbial strains for low-cost and high-efficiency production has become a cutting-edge focus in the field of biomanufacturing. Therefore, in-depth research on biosurfactants holds significant scientific value and application prospects for driving the green transformation of industries, developing a circular economy, and addressing environmental pollution issues [1].

In its native biological context, BslA is a secreted protein that self-assembles at the surface of Bacillus subtilis biofilms, forming a highly ordered, elastic layer at the interface. This layer functions as a hydrophobic “raincoat,” enveloping the cellular community within the dense biofilm matrix and conferring the biofilm’s characteristic hydrophobicity. BslA operates primarily through extracellular self-assembly rather than via direct interaction with cell wall components [7,8]. A defining feature of BslA is its exceptional hydrophobicity, which drives its self-assembly at air–liquid or liquid–solid interfaces into a dense, crystalline-like hydrophobic protein film [8].

To date, recombinant BslA protein expression has utilized prokaryotic organisms as hosts. Morris et al. heterologously expressed orthologous bslA genes from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Bacillus licheniformis, and Bacillus pumilus in a mutant of Bacillus subtilis possessing a bslA gene deletion (bslA−) [9]. The GST-tagged BslA variant was also successfully expressed in Escherichia coli for structural analysis [10]. However, no literature is available on pilot- or production-scale bioreactor processes for native BslA or recombinant BslA protein. Although the BslA protein, as a novel surfactant, holds broad application prospects, several challenges must be overcome to advance from academic research to large-scale commercial production, such as increasing yield and reducing separation and purification costs.

Pichia pastoris is a highly advantageous eukaryotic expression system for producing recombinant proteins, offering several key benefits: high protein yield driven by strong inducible promoters; capability for post-translational modifications such as glycosylation and disulfide bond formation, enhancing protein functionality; high solubility and reduced risk of inclusion body formation compared to bacterial systems; scalability to high-density fermentation for industrial-scale production; and low host protein contamination, simplifying downstream purification [11]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated as a suitable host for the soluble expression of hydrophobic proteins [12]. These features make it particularly suitable for producing recombinant BslA protein. P. pastoris GS115 is a widely used histidine auxotroph (his4−) strain, allowing for selection with vectors containing the HIS4 marker [13]. Its key feature is the methanol utilization phenotype (Mut+), enabling strong, methanol-induced expression of target genes via the AOX1 promoter [14]. This system is valued for high expression levels, ability to perform eukaryotic post-translational modifications, and suitability for high-density fermentation.

Previously, we identified the expression of the BslA protein in Bacillus paralicheniformis BL-1 in response to salinity stress [15]. In this research, P. pastoris GS115 was selected as a host cell for secretory expression of BslA from B. paralicheniformis BL-1 under control of the AOX1 promoter. The production of recombinant BslA was improved in lab-scale fermentation by switching from a constant dissolved oxygen feeding strategy (DO-stat) to oxygen-limited fed-batch (OLFB). The expressed protein concentration in the supernatant was quantitatively determined to be 657 mg/L after 120 h of fermentation. This demonstrated the potential of using P. pastoris as an expression platform to industrially produce BslA protein with high yield and in a proper surface activity.

2. Methods

2.1. Strains and Medium

The recombinant BslA protein from B. paralicheniformis BL-1 was heterologously expressed in P. pastoris GS115 via the plasmid vector pPIC9K (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Expression was driven by the AOX1 promoter, with the kanamycin resistance gene serving as the selectable marker.

For routine cultivation of P. pastoris GS115, yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) medium was used, containing 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, and 20 g/L glucose. Selection of His+ transformants was carried out on minimal dextrose (MD) medium, which consisted of 13.4 g/L yeast nitrogen base (YNB), 0.4 mg/L biotin, and 20 g/L glucose.

Seed cultures of P. pastoris GS115 were prepared in shake flasks with buffered glycerol-complex medium (BMGY). This medium contained 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 13.4 g/L YNB, 0.4 mg/L biotin, and 10 g/L glycerol.

For heterologous protein expression under shake-flask conditions, buffered methanol-complex medium (BMMY) was employed. This medium contained 10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone, 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), 13.4 g/L YNB, 0.4 mg/L biotin, and 5 g/L methanol.

2.2. Construction of Recombinant Expression Plasmid pPIC9K-bslA

The bslA gene sequence was obtained from the genomic data of the BL-1 strain (accession number PRJNA1109274). Signal peptides of BslA were predicted by the SignalP 6.0 server [16]. After removal of the signal peptide bslA33-179, the coding sequence was codon optimized by NovoPro (https://www.novoprolabs.com/tools/codon-optimization (accessed on 5 June 2023)) for P. pastoris. Sequences of nature bslA and optimized bslA are listed in Supplementary Table S3. The optimized bslA gene (540 bp) was synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) and subcloned into the pPIC9K vector using the EcoRI and NotI restriction sites. The constructed pPIC9K-bslA plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α, and the plasmid was extracted by using the EZ-500 Spin Column Plasmid Max-Preps Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sangong, Shanghai, China).

The plasmid was digested by SacI (FastDigest, ThermoFisher) restriction endonuclease for linearization according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The linearized DNA was ethanol precipitated (1/10 V of CH3COONa and 2.5-fold V of ice-cold ethanol), and stored at −80 °C for further use.

2.3. Yeast Transformation

The plasmid was transformed into P. pastoris GS115 via electroporation, following a previously reported procedure with minor adjustments [17]. Briefly, an overnight culture of P. pastoris GS115 in YPD medium was used to inoculate fresh YPD medium at 5% (v/v) in a 500 mL shake flask. The culture was incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 250 rpm until the OD600 reached 1.0–2.0. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1500× g for 5 min. For each transformation, approximately 8 × 108cells (based on an OD600 of 1.0 corresponding to 5 × 107 cells/mL) were treated with 8 mL of LiAc/DTT solution [100 mM LiAc, 10 mM DTT, 0.6 M sorbitol, and 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5] at room temperature for 30 min. After incubation, the cells were pelleted, washed three times with 1.5 mL of ice-cold 1 M sorbitol, and finally resuspended in ice-cold 1 M sorbitol to a density of 1010 cells/mL.

For the electroporation, 80 μL of cells were mixed with 10 ng of linearized DNA, and transferred to a 0.2 cm electroporation cuvette (Gene Pulser, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and kept on ice for at least 10 min. The Electro Cell Manipulator 600 (BTX) was used for an electroporation pulse (1.5 kV, 25 μF, 186 Ω). The electroporated cells were immediately added with 1 mL of chilled 1 M sorbitol, and 200 μL aliquots were spread on MD agar plates for selecting His+ transformants at 30 °C until the colonies appeared.

For screening recombinant P. pastoris GS115 integrated with pPIC9K-bslA, the His+ transformant colonies on MD plates were picked up into 200 μL YPD medium in 96-well plates and aerobically incubated at 30 °C for 2 days. The 10 μL culture was spotted on a YPD agar plate supplemented with 0, 0.25 mg/mL, 0.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL, and 2.0 mg/mL geneticin, and then incubated at 30 °C for 2 days. This antibiotic gradient assay allowed the identification of transformants with higher gene copy numbers, which were then selected for subsequent fermentation. The integration of the gene of interest using the α-factor primer (5′-TAC TAT TGC CAG CAT TGC TGC-3′) paired with the 3′AOX1 primer (5′-GCA AAT GGC ATT CTG ACA TCC-3′).

2.4. Expression of Recombinant BslA in Shake Flask

Shake-flask production of the recombinant protein was performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, with minor modifications as described below. A single ~2 mm colony of integrant was inoculated into 50 mL of BMGY in a 500 mL shake flask, and grown at 30 °C with 250 rpm agitation until OD600 reached 2. The cells were collected by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 min, and the cell pellets were resuspended in an OD600 of 1.0 in 25 mL BMMY, and then continued to grow at 30 °C. After 24 h, 100% methanol was added to a final concentration of 5 g/L every 24 h to maintain the protein induction, and 200 μL samples were taken every 24 h to analyze the expression of recombinant BslA by electrophoresis.

2.5. Fed-Batch Fermentations

The basal salt medium (BSM) used for fed-batch cultivations was prepared with the following components per liter of distilled water: 26.7 mL of H3PO4 (85%), 0.93 g of CaSO4, 18.2 g of K2SO4, 14.9 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 4.13 g of KOH, 40.0 g of glycerol, and 4.35 mL of sterile PTM1 trace salts solution. The PTM1 trace salts solution contained per liter: 6.0 g of CuSO4·5H2O, 0.08 g of NaI, 3.0 g of MnSO4·H2O, 0.2 g of Na2MoO4·2H2O, 0.02 g of H3BO3, 0.5 g of CoCl2, 20.0 g of ZnCl2, 65.0 g of FeSO4·7H2O, 0.3 g of biotin, and 5 mL of H2SO4. The PTM1 trace salt solution was filtered by 0.22 μm membrane and all bioreactor protein production runs were performed using 5 L Bench-top Glass Bioreactor (Good Shine GS-F3005S) under the following operation conditions: initial volume 3 L, stirring rate 400 rpm, temperature at 30 °C, gas flow rate 1 vvm, and pH controlled at 6.0 by feeding 30% (v/v) ammonia. The pH and DO were monitored online by pH Sensor 405 (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH, USA) and DO Sensor InPro 6800 (Mettler Toledo), respectively. For the fed-batch culture process, the real-time volume of the fermentation system was determined by measuring the weight loss of the feeding bottle containing the supplemented substrate.

The fermentations were carried out with two modes: constant dissolved oxygen (DO) feeding (DO-stat) and oxygen-limited fed-batch (OLFB). In the DO-stat mode, the cultivation started with a batch phase using 40 g/L glycerol as a carbon source. Secondly, a 12 h glycerol feeding phase started when glycerol was exhausted as indicated by a DO spike, and the DO was controlled at 20%. Finally, the methanol feeding phase started using methanol as the sole carbon source and inducer. Methanol feeding was initiated at a low rate of 2 mL/(L·h) for 4 h to prevent a sharp drop in biomass during the transition from glycerol to methanol. The feeding rate was then gradually increased to 3 mL/(L·h) for another 4 h to allow cells to adapt further. In the third stage, the rate was raised to 5 mL/(L·h) to ensure methanol remained non-limiting while the oxygen supply kept dissolved oxygen (DO) at 20% until 70 h. After 70 h, as oxygen demand increased further, we discontinued the 20% DO setpoint and accordingly increased the methanol feed rate to 8 mL/(L·h), stopping methanol addition at 90 h.

In OLFB mode, the cultivation started with the same batch phase using 40 g/L glycerol as a carbon source. When glycerol was exhausted, as indicated by a DO spike, the methanol feeding phase started. Set the gas flow at 1 vvm and the stirring rate at maximum without controlling the DO level. The methanol feeding started at 20 h with a rate of 2 mL/(L·h). Since oxygen was the limiting factor and cell density was relatively low, adjustments were made based on the DO signal. Whenever DO dropped to zero, the methanol feed rate was increased to 3 mL/(L·h). After 60 h, based on empirical observation that biomass had accumulated sufficiently and cells had adapted to the methanol flow, the rate was raised to 5 mL/(L·h) and maintained until the end of fermentation. This ensured that methanol did not become a limiting substrate; in this mode, only oxygen remained the limiting factor.

2.6. Biomass Analysis

Biomass concentration was determined as dry cell weight (DCW) per liter of culture broth. As indicated by the sampling time, 5 mL of broth was collected with three technical replicates. The samples were centrifuged at 1500× g for 5 min. Cell pellets were washed twice with ddH2O via centrifugation and subsequently dried at 105 °C until constant weight was achieved. The weight was measured after cooling to room temperature.

2.7. Calculation of the Specific Growth Rate and Production Rate

To eliminate the influence of volume variation on specific growth rate calculation during fed-batch culture, the specific growth rate μ with the unit of h−1 was determined by correcting the volume change in the fermentation system, with the equation shown below:

where X1 and X2 represent the DCW concentrations of the fermentation broth at the initial time point t1 and the final time point t2, respectively, with the unit of g/L; V1 and V2 denote the volumes of the fermentation system corresponding to time points t1 and t2 respectively, with the unit of L; t1 and t2 are the initial and final time points of the culture period, both with the unit of h.

Standard deviation of the specific growth rate SD(μ) with the unit of h−1 was calculated with the equation, assuming volume was free of measurement error:

where SD(X1) and SD(X2) represent the standard deviations of the DCW concentrations of the fermentation broth at the initial time point t1 and the final time point t2, respectively, with the unit of g/L; the definitions of X1, X2, t1, and t2 are consistent with those in the specific growth rate calculation equation above.

The volumetric productivity Rp with the unit of mg/(L∙h) was determined by correcting the volume change in the fermentation system, with the equation shown below:

where P1 and P2 represent the recombinant BslA concentrations in the fermentation broth at the initial time point t1 and the final time point t2, respectively, with the unit of mg/L.

The standard deviation of the volumetric productivity SD(Rp) with the unit of mg/(L∙h) was derived based on the error propagation principle, assuming volume was free of measurement error:

where SD(P1) and SD(P2) are the standard deviations of the recombinant BslA concentrations at time points t1 and t2, respectively, with the unit of mg/L; the definitions of P1, P2, t1, and t2 are consistent with those in the volumetric productivity calculation equation above.

The total protein synthesis rate of recombinant BslA (rp) with the unit of mg/h was determined using the following equation to eliminate the influence of volume variation during fed-batch culture:

where P1 and P2 are the recombinant BslA concentrations at time points t1 and t2, respectively, with the unit of mg/L; V1, V2, t1, and t2 are consistent with those in the specific growth rate calculation equation above

The standard deviation of the total protein synthesis rate, SD(rp), with the unit of mg/h, was calculated based on the error propagation principle, assuming no measurement error for the fermentation volume:

where SD(P1) and SD(P2) are the standard deviations of the recombinant BslA concentrations at time points t1 and t2, respectively, with the unit of mg/L; the definitions of P1, P2, t1, and t2 are consistent with those in the total product formation rate calculation equation above.

2.8. Protein Electrophoresis and Determining Protein Concentration

Culture broth was centrifuged to remove the cell pellets, and the supernatant was mixed with LDS sample buffer (NuPAGE, ThermoFisher), incubated at 75 °C for 5 min, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 3 min. The proteins were separated by commercial 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (NuPAGE, ThermoFisher) with MOPS buffer at 200 V for 40 min. The electrophoresed gel was stained with Coomassie Blue. The relative abundance of recombinant BslA was quantified by ImageJ 1.54g [18] with three technical replicates. The target protein band of approximately 15 kDa was excised from the SDS-PAGE gel. The gel slice was dissolved, and the protein was recovered using the Micro Protein PAGE Recovery Kit (Sangon Biotech). The concentration of the recovered protein was then determined with the Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Sangon Biotech).

2.9. Measurement of Biosurfactant Activity

Culture broth was centrifuged to remove the cell pellets. The cell-free supernatant was desalted, and the buffer was diluted to the same volume of PBS (pH 7.0) buffer with a Zeba 7K MWCO spin desalting column (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For protein concentration, the desalted protein solution was 20-fold concentrated by ultrafiltration at 4 °C using Pierce Protein Concentrators PES, 3K MWCO (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The emulsification index (E24%) was used to determine the biosurfactant activity of culture broths or concentrated proteins [19]. In brief, 5 mL of the sample (desalted cell-free supernatant or concentrated protein) was combined with an equal volume of kerosene. The mixture was vortexed vigorously for 2 min and then allowed to stand undisturbed for 24 h. E24% was calculated using the formula: (height of the emulsion layer/total height of the mixture) × 100%. All measurements were conducted in triplicate.

2.10. Identification of BslA by Mass Spectrometry

MS identification of BslA was according to the previous method with slight modifications [20]. Briefly, the electrophoresed gel was Coomassie Blue-stained, and the bands corresponding to recombinant BslA were cut. The gel pieces were cleaned, desalted, and vacuum centrifuged and then digested with 5 ng/μL of trypsin at 37 °C for at least 20 h. Tryptic peptides were acidified with 100 μL extraction buffer (100% ACN, 0.1% TFA), desalted with a C18 Stage Tip column (ThermoFisher), vacuum centrifuged, and lyophilized. The tryptic peptides were resuspended in 0.1% formic acid before analysis.

Protein samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS utilizing a ThermoFisher Q-Exactive Plus mass spectrometer coupled to an Easy nLC1000 system. Peptides were first trapped on a ReproSil-Pur C18 column (0.10 mm × 20 mm, 5 μm) and then separated on an analytical ReproSil-Pur C18 column (0.75 mm × 150 mm, 3 μm) with a 300 nL/min flow rate. Peptides were separated using a linear gradient of 1.6–4% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) for 0 min to 2 min, 4–22.4% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) for 2 min to 44 min, 22.4–32% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) for 44 min to 51 min, 32–80% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) for 51 min to 53 min, and 80% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) for 53 min to 60 min. Full-scan MS spectra were collected at a resolution of 100,000, with the top 10 most intense ions subsequently selected for MS/MS fragmentation. Precursor ions selected for MS/MS analysis were required to have a known charge state of two or higher. Peptide sequences were searched using MaxQuant 2.0 software [21,22] against the BslA protein sequence, uniport-Komagataella pastoris (Pichia pastoris) [4922]-5257-20231020.fasta and common contaminants. For the database search, we employed a precursor mass tolerance of 2.5 Da and a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.2 Da, while allowing for up to two missed cleavages.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of Recombinant BslA Protein

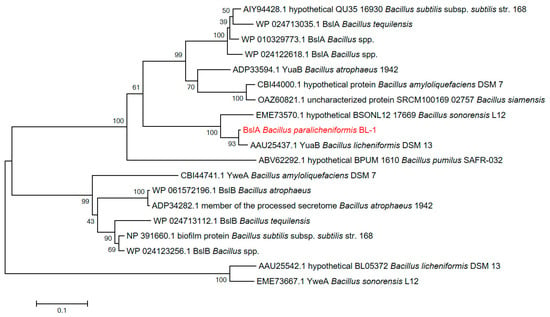

Research indicated that BslA, produced by Bacillus licheniformis, is a natural surface-active biomolecule contributing to the reduction in surface tension [12]. In a previous study, we noticed that the expression of bslA in B. paralicheniformis BL-1 was in response to the salinity stress [15]. We performed an amino acid sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis to gather information on the classification of the BslA protein in Bacillus species (Table S1). The BslA produced in B. paralicheniformis BL-1 was close to YuaB (identity of 97.21%) in B. licheniformis DSM 13 with A21V and V52T substitutions, while BslA from B. paralicheniformis BL-1 was distant to hypothetical protein BL05372 (identity of 38.46%) in B. licheniformis DSM 13 and YweA in B. sonorensis L12 (Figure 1 and Figure S1). Therefore, we hypothesized that BslA from B. paralicheniformis BL-1 was also a hydrophobic protein with potential biosurfactant activity.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of BslA proteins in Bacillus based on amino acid sequences. The amino acid sequences of BslA proteins were aligned with other biofilm proteins from Bacillus, and a phylogenetic tree was calculated in MEGA 7.0 by the Neighbor–Joining method with a bootstrap value of 1000 replicates. The BslA from B. paralicheniformis studied in this study was highlighted in red.

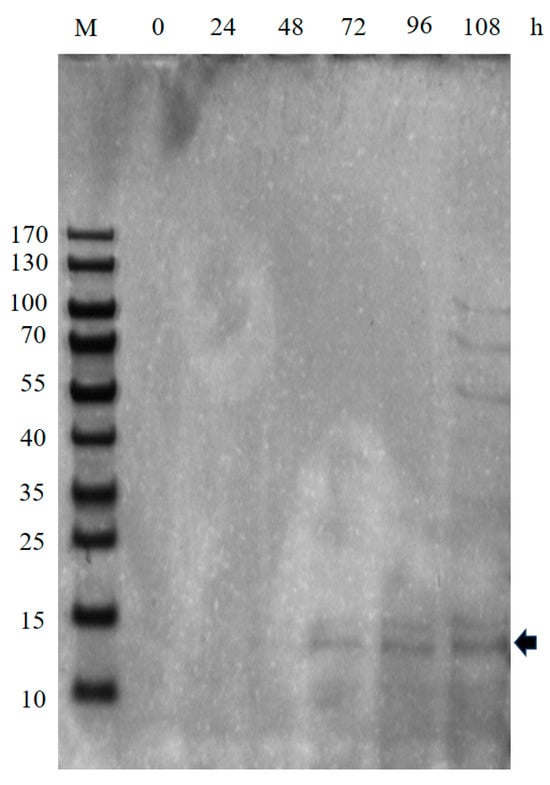

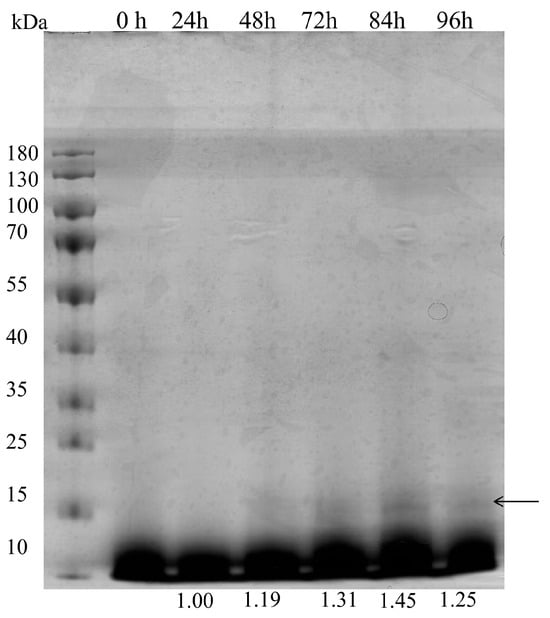

Considering the expression of secreted proteins, high-density fermentation for industrial-scale production, and low host protein contamination, simplifying downstream purification, we selected P. pastoris GS115 as the host to express recombinant BslA. The SignalP 6.0 server [16] predicted the presence of signal peptides and a cleavage site between positions 32 and 33. Thus, the coding sequences of bslA33-179 were codon optimized based on the P. pastoris codon bias, and the expression vector pPIC9K-bslA was constructed. One transformant, GS115/bslA-19, was able to grow in YPD agar containing 1 mg/mL of G418; therefore, this transformant was selected as a potential candidate to evaluate the expression of recombinant BslA (Figures S2 and S3). The expression of recombinant BslA33-179 was verified in shake flasks using BMMY. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed the presence of an approximately 15 kDa protein in the supernatant (Figure 2). The band corresponding to ~15 kDa was subsequently excised from the gel, and the protein was redissolved and extracted for further mass spectrometry analysis. The results (Table S2) showed that four characteristic peptides were detected by mass spectrometry, confirming that the ~15 kDa protein is the recombinant BslA protein.

Figure 2.

Expression of recombinant BslA in P. pastoris GS115. A single colony GS115/bslA transformant was cultured in BMGY at 30 °C for 24 h, and cell pellets were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in BMMY for methanol induction of BslA expression. The 20 μL of supernatants were collected and electrophoresed, followed by Coomassie blue R-250 staining. The arrow indicated the expected protein bands; M, marker; h, sampling hour.

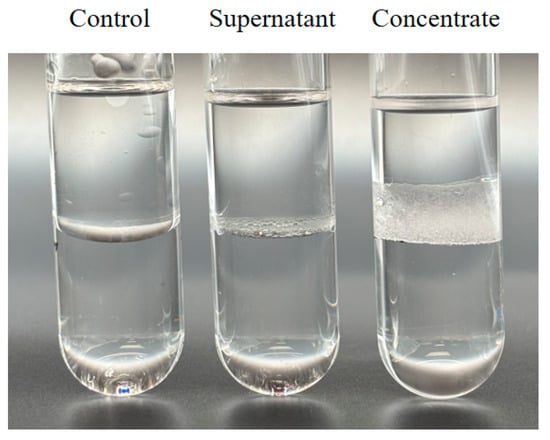

The biosurfactant activity was determined by emulsification index (E24%) by using culture broths or concentrated proteins. The supernatant displayed limited surface activity because of the low BslA protein concentration, as indicated by the height of the emulsion layer. The 20-fold concentrate exhibited an emulsification index of 25% suggested moderate surface activity of the concentrate (Figure 3). Taken together, these results indicated that the recombinant BslA33-179 with biosurfactant activity was successfully expressed in P. pastoris GS115.

Figure 3.

Biosurfactant activity of recombinant BslA protein. The culture broth was harvested by centrifugation, and the cell pellets were discarded. The supernatants were desalted to PBS (pH 7.0). Part of the desalted protein solutions was concentrated by ultrafiltration. Five milliliters of kerosene was added to the same volume of desalted cell-free supernatant (Supernatant) or concentrated protein solution (Concentrate). The desalted supernatant of BMMY-cultured GS115 strain without exogenous gene integration was used as a control (Control). The mixtures were vortexed and rested 24 h at room temperature. The assay was performed in triplicate (n = 3).

3.2. Fed-Batch Fermentation in DO-Stat Mode

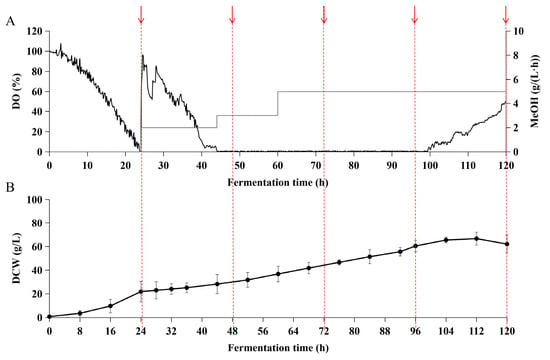

Next, we examined whether the expression of the recombinant BslA could be scaled up in the lab-scale. The fed-batch fermentation began with a batch phase, which contained glycerol basal salts medium using 40 g/L glycerol as a carbon source (glycerol phase). During the glycerol phase, DO was reduced to 17.4% (Figure 4A), and the dry cell weight (DCW) reached 21.9 ± 2.6 g/L at the end of the glycerol phase (Figure 4B). When the DO spike was observed, a 12 h glycerol feeding phase started to further increase biomass density with DO control at 20% by enhancing the oxygen supply (Figure 4A). The biomass accumulated to 56.4 ± 4.1 g/L at 36 h (Figure 4B). The methanol feeding was started at 36 h, with a slow feed rate at 2 mL/(L·h) in the beginning (36–40 h), and gradually increased to 3 mL/(L·h) from 40 h to 44 h, 5 mL/(L·h) from 40 h to 68 h, and 7.5 mL/(L·h) from 68 h to 90 h. In the methanol phase, the dry cell weight reached the peak (72.51 ± 5.30 g/L) at 76 h with a relatively slow specific growth rate due to the methanol as the sole carbon source (Figure 4B). At the end of fermentation at 96 h, the accumulation of fermentation products reached 425 ± 8.53 mg/L (Table 1). However, we noticed a drop in the biomass during the last 20 h of the fermentation (Figure 4B and Table 1), which suggested the excessive accumulation of methanol in the late-stage fermentation. Surprisingly, even though the bacterial biomass decreased and the specific growth rate slowed down, the recombinant BslA production was higher than that in the previous period of low methanol feeding. In late-stage cell death, it was accompanied by a decrease in the accumulation of recombinant BslA protein in the medium (Figure 5). This was consistent with the negative production rate in the late-stage fermentation stage as indicated by volumetric productivity (−5.10 ± 0.008 mg/(L∙h)) and total protein synthesis rate (−21.52 ± 0.092 mg/h) as shown in Table 1. In the high methanol feed phase (7.5 mL/(L∙h) from 70 to 90 h, the DO could only be controlled below 10% due to the oxygen supply limit coming from the equipment. This indicated fed-batch process still needs to be improved for targeting the accumulation of recombinant BslA when close to the end of fermentation.

Figure 4.

Fermentation parameters in DO-stat mode. In DO-stat mode, DO was controlled above 20% from 24 h to 72 h. (A) Online DO measurement and methanol feeding rate. DO is represented by the black line, and methanol feeding rate by the grey solid line. (B) DCW was measured at the indicated time with three technical replicates (n = 3). Time points for SDS-PAGE protein analysis are indicated by arrows.

Table 1.

Fermentation parameters.

Figure 5.

Analysis of recombinant BslA production in DO-stat mode fermentation. Samples were collected at the indicated time points. Supernatants were collected by centrifugation, and 20 μL of supernatants were mixed with LDS sampling buffer and electrophoresed. The gels were stained by Coomassie blue R-250. The relative abundance of recombinant BslA was quantified by ImageJ and represented the mean of three technical replicates. The arrow indicated the expected protein bands.

3.3. Fed-Batch Fermentation in OLFB Mode

In DO-stat mode, the glycerol feeding phase enables a high-cell-density at the onset of methanol induction, facilitating a rapid recombinant protein expression. However, cell density decreased in late-stage fermentation, likely due to excessive methanol accumulation or the cell toxicity of the recombinant BslA protein. This decline subsequently reduced the final accumulation of recombinant BslA in the culture medium. We therefore hypothesized that while oxygen-limited cultivation yields a lower final cell density than the DO-stat mode, it mitigates late-stage cell death and product degradation. This trade-off allows for a prolonged fermentation period, ultimately achieving a higher final product concentration. Furthermore, the lower cell density reduces the equipment’s demand for a high oxygen supply.

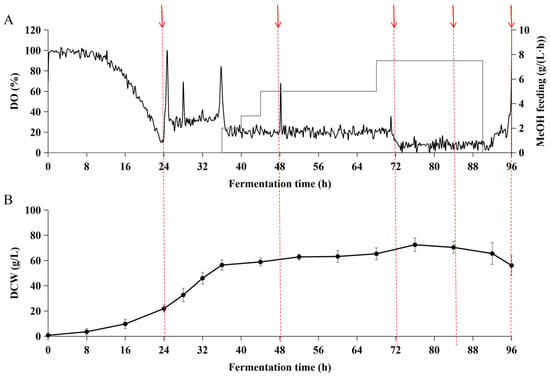

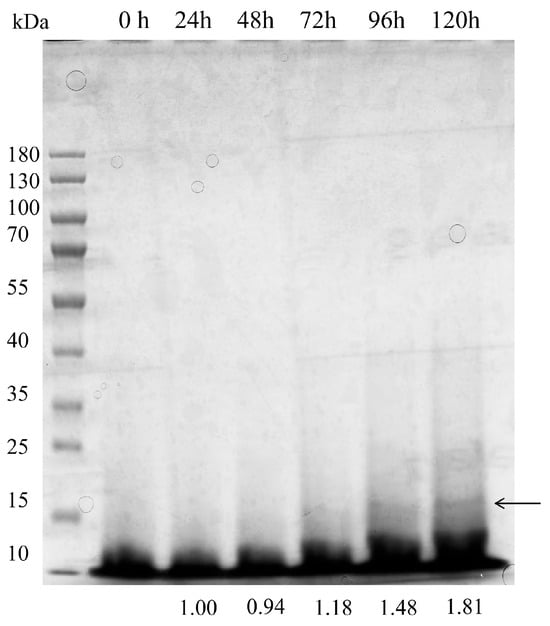

In OLFB mode, the total fermentation time was able to extend to 120 h. Removed glycerol feeding phase resulted in 0.15 ± 0.029 h−1 of specific growth rate before the methanol induction (Table 1). The methanol feeding was initially set at 2 mL/(L·h) and raised to 3 mL/(L·h) when DO reached zero at 44 h, and further raised to 5 mL/(L·h) from 60 h to 120 h (Figure 6A). The lower cell density in OLFB mode resulted in a higher specific rate in the methanol phase than in DO-stat mode (Table 1). The biomass reached 66.70 ± 5.44 g/L at 112 h and reduced to 62.11 ± 7.80 g/L at 120 h (Figure 6B). The degradation of recombinant BslA in the supernatant was not observed in the OLFB mode (Figure 7). Although the cell density and recombinant BslA productivity in OLFB mode were slightly lower than in DO-stat mode, the accumulated concentration of recombinant BslA protein was higher in OLFB mode, reaching 657 ± 6.82 mg/L at 120 h (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Fermentation parameters in the OLFB mode. In the OLFB mode, oxygen supply is limited from 44 h to 100 h. (A) Online DO measurement and methanol feeding rate. DO is represented by the black line, and methanol feeding rate by the grey solid line. (B) DCW was measured at the indicated time with three technical replicates (n = 3). Arrows represented the time points of sampling for SDS-PAGE protein analysis.

Figure 7.

Quantification of recombinant BslA production in the OLFB fed-batch fermentation. Recombinant BslA levels in culture supernatants were analyzed at the specified intervals. A representative Coomassie blue-stained gel, loaded with 20 μL of supernatant per lane, is shown. Band intensity was quantified with ImageJ, and the relative abundance represented the mean of three technical replicates. The arrow indicated the expected protein bands.

4. Discussion

To date, recombinant BslA protein has successfully expressed in the B. subtilis and E. coli systems [9,10]. However, the productivity of the BslA protein in these two prokaryotic cell systems has not been reported to date, given that the scope of those earlier investigations was limited to functional and structural analyses of the protein [9,10]. In this study, we selected P. pastoris GS115 as a host cell for expressing recombinant BslA and demonstrated that the recombinant BslA protein identified in B. paralicheniformis BL-1 [15] had biosurfactant activity.

Unlike bacterial systems, e.g., E. coli, one advantage of P. pastoris as an expression system is that it does not produce endotoxins, which is critical for producing proteins for human use [23]. BslA protein functions as a “cross-linking” agent within the extracellular matrix and interacts with other matrix components, meaning the Bacillus species secretes other cell–matrix components together with BslA expression [7,24]. Thus, purifying BslA from a Bacillus expression system requires separating it from the host’s many other secreted proteins. The other advantage of choosing the P. pastoris expression system for expressing the BslA protein is that secretory expression using simple, defined mineral salt medium facilitates downstream purification by avoiding contamination from intracellular host proteins and eliminating the need for cumbersome cell disruption steps, thereby enhancing the recovery rate and purity of the target protein [25]. Furthermore, the use of the strong, methanol-inducible AOX1 promoter provided precise control over BslA expression, enabling its scalable production [26].

In the high-cell-density fermentation of Pichia pastoris for recombinant protein expression, while a high oxygen supply promotes both biomass accumulation and protein production, it also leads to significantly increased oxygen demand, posing substantial technical and economic challenges in large-scale processes [27,28]. We employed a standard DO-stat strategy to express BslA in a lab-scale bioreactor using P. pastoris GS115 (Figure 4). During the late fermentation stage, we observed a decline in biomass, likely due to an insufficient oxygen supply (inability to maintain 20% DO) and/or environmental stress resulting from the accumulating BslA, which exhibited surfactant activity. The decline of biomass was consistent with a reduction in product titer, possibly due to cell death and proteolytic degradation. Targeting higher product accumulation at the end of fermentation, we improved the strategy by removing the glycerol feeding phase and implementing an oxygen-limited fed-batch (OLFB) process (Figure 5). This approach aimed to lower the initial biomass at the beginning of methanol induction and extend the production phase to enhance recombinant BslA yield. To our knowledge, only Charoenrat and colleagues [29,30] have reported the application of this approach so far. In our work, we observed that the same strategy also improved the expression of the BslA protein, suggesting that this dissolved oxygen limitation method may be applicable and worth trying for the expression of other proteins in P. pastoris.

Another potential cause of the observed biomass decline in the later fermentation stage could be the accumulation of excess methanol [31]. Under the oxygen-limited conditions in the DO-stat process, as indicated by dissolved oxygen dropping to zero after 72 h (Figure 4A), methanol was not efficiently consumed and instead accumulated, exerting cytotoxic effects. Consequently, the reduction in the methanol feed rate in the OLFB process might also benefit product synthesis and prevent the degradation of the product. On the other hand, in the DO-stat mode, the elevated methanol feeding rate (7.5 mL/(L·h) during 70–90 h) resulted in a DO level of approximately 10%. Notably, the product formation rate under this low-DO condition was higher than when DO was controlled at 20%. However, it was observed that the biomass began to decline in the later part of this high-feeding phase and continued to decrease throughout the subsequent late-stage of fermentation. This observation suggests that a methanol feeding rate of 5 mL/(L·h) might be the maximum to avoid methanol-induced cytotoxicity under these conditions. However, since we did not measure residual methanol concentrations, the precise relationship between the methanol feeding rate and the product formation rate remains unclear. Optimizing the methanol feed strategy under the premise of oxygen limitation represents a direction for future process improvement [32,33]. Furthermore, implementing a methanol-limited fed-batch strategy based on real-time methanol monitoring could be considered as a safer and more robust approach to mitigate cell death and prevent protein degradation.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results, recombinant BslA was successfully expressed in P. pastoris GS115 and shown to possess biosurfactant activity. For scaling up production, the OLFB fermentation mode was superior to the DO-stat mode, as it prevented late-stage cell death and product degradation, resulting in a final protein yield of 657 ± 14 mg/L after 120 h of fermentation. This suggested that the OLFB strategy could be applied for the industrial-scale production of this biosurfactant protein.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation12010051/s1, Figure S1. Amino acid sequence alignment of biofilm surface layer protein A (BslA) from Bacillus. Colors indicate global consensus. The multiple sequence alignment and consensus analysis were conducted using Jalview (version 2.11.4). Figure S2. Selection of geneticin resistant transformants. A representative figure for screening recombinant P. pastoris GS115 integrated with pPIC9K-bslA. After initial selection of His+ transformants by using MD plates, colonies were picked up into 200 μL YPD medium in 96-wells plates and aerobically incubated at 30 °C for 2 days. The 10 μL culture was spotted on YPD agar plate supplemented with 0, 0.25 mg/mL, 0.5 mg/mL, 1.0 mg/mL, and 2.0 mg/mL geneticin, and then incubated at 30 °C for 2 days. Figure S3. PCR identification of genomic integration of pPIC9K-bslA. The integration of gene of interest in recombinant P. pastoris were identified by PCR, using the α-factor primer (5’-TAC TAT TGC CAG CAT TGC TGC-3’) and 3’AOX1 primer (5’-GCA AAT GGC ATT CTG ACA TCC-3’). Table S1. Selected BslA proteins. Table S2. MS identification of BpBslA protein. Table S3. Sequences of native bslA and optimized bslA.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization of the project and design: L.Y., L.Z. and R.G. Drafting the article or critically revising it for important intellectual content: L.Y., R.G. and L.Z. Critical analysis of data and reviewing manuscript: All. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, under Grants [number: 31801102].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sankhyan, S.; Kumar, P.; Pandit, S.; Kumar, S.; Ranjan, N.; Ray, S. Biological machinery for the production of biosurfactant and their potential applications. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 285, 127765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cui, C.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; He, B.; Long, Y.; Ye, J. Biodegradation of petroleum hydrocarbons based pollutants in contaminated soil by exogenous effective microorganisms and indigenous microbiome. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 253, 114673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markam, S.S.; Raj, A.; Kumar, A.; Khan, M.L. Microbial biosurfactants: Green alternatives and sustainable solution for augmenting pesticide remediation and management of organic waste. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2024, 7, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.M.; Stamford, T.L.; Sarubbo, L.A.; de Luna, J.M.; Rufino, R.D.; Banat, I.M. Microbial biosurfactants as additives for food industries. Biotechnol. Prog. 2013, 29, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, F.; Maji, D.; Phatake, R.S.; Kumar, K. Pharmaceutical applications of microbial biosurfactants. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 681, 125887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adu, S.A.; Naughton, P.J.; Marchant, R.; Banat, I.M. Microbial biosurfactants in cosmetic and personal sskincare pharmaceutical formulations. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaouteli, S.; Bamford, N.C.; Brandani, G.B.; Morris, R.J.; Schor, M.; Carrington, J.T.; Hobley, L.; van Aalten, D.M.F.; Stanley-Wall, N.R.; MacPhee, C.E. Lateral interactions govern self-assembly of the bacterial biofilm matrix protein BslA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2312022120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.J.; Bamford, N.C.; Bromley, K.M.; Erskine, E.; Stanley-Wall, N.R.; MacPhee, C.E. Bacillus subtilis matrix protein TasA is interfacially active, but BslA dominates interfacial film properties. Langmuir 2024, 40, 4164–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.J.; Schor, M.; Gillespie, R.M.C.; Ferreira, A.S.; Baldauf, L.; Earl, C.; Ostrowski, A.; Hobley, L.; BromLey, K.M.; Sukhodub, T.; et al. Natural variations in the biofilm-associated protein BslA from the genus Bacillus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobley, L.; Ostrowski, A.; Rao, F.V.; BromLey, K.M.; Porter, M.; Prescott, A.R.; MacPhee, C.E.; van Aalten, D.M.; Stanley-Wall, N.R. BslA is a self-assembling bacterial hydrophobin that coats the Bacillus subtilis biofilm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13600–13605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unver, Y.; Dagci, I. Komagataella phaffii (Pichia pastoris) as a powerful yeast expression system for biologics production. Front. Biosci. 2024, 16, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, B.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Qiao, M. Heterologous expression and characterization of the hydrophobin HFBI in Pichia pastoris and evaluation of its contribution to the food industry. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbalaei, M.; Rezaee, S.A.; Farsiani, H. Pichia pastoris: A highly successful expression system for optimal synthesis of heterologous proteins. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 5867–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Shi, L.; Qi, F.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Song, Z.; Cai, M. Methanol-independent protein expression by AOX1 promoter with trans-acting elements engineering and glucose-glycerol-shift induction in Pichia pastoris. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Guo, R.; Liu, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, R.; Shao, C.; Zhou, J.; Ding, F.; Yu, L. Isolation of Bacillus paralichenifromis BL-1 and its potential application in producing bioflocculants using phenol saline wastewater. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G. A brief history of protein sorting prediction. Protein J. 2019, 38, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Letchworth, G.J. High efficiency transformation by electroporation of Pichia pastoris pretreated with lithium acetate and dithiothreitol. BioTechniques 2004, 36, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Khalid, Z.M.; Malik, K.A. Enhanced biodegradation and emulsification of crude oil and hyperproduction of biosurfactants by a gamma ray-induced mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1995, 21, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Sun, W. Sumoylation stabilizes RACK1B and enhance its interaction with RAP2.6 in the abscisic acid response. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Carlson, A.; Sinitcyn, P.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. Visualization of LC-MS/MS proteomics data in MaxQuant. Proteomics 2015, 15, 1453–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Cox, J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 2301–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallach, R.E.; Conticello, V.P.; Chaikof, E.L. Expression of a recombinant elastin-like protein in Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol. Prog. 2009, 25, 1810–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yuan, S.; Tao, H.; Dong, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, W.; Liu, C. Bacillus anthracis S-layer protein BslA binds to extracellular matrix by interacting with laminin. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Zhang, C.; Wu, J.; Tang, Q.; Xie, Y.; Yu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y. Optimizing Pichia pastoris protein secretion: Role of N-linked glycosylation on the alpha-mating factor secretion signal leader. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 391, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, Y.H.; Tao, L.F.; Yang, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Cai, M.H. Rational design and characterization of enhanced alcohol-inducible synthetic promoters in Pichia pastoris. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0219124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.C.; Gong, T.; Wang, Q.H.; Liang, X.; Chen, J.J.; Zhu, P. Scaling-up fermentation of Pichia pastoris to demonstration-scale using new methanol-feeding strategy and increased air pressure instead of pure oxygen supplement. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastilan, R.; Boes, A.; Spiegel, H.; Voepel, N.; Chudobova, I.; Hellwig, S.; Buyel, J.F.; Reimann, A.; Fischer, R. Improvement of a fermentation process for the production of two PfAMA1-DiCo-based malaria vaccine candidates in Pichia pastoris. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charoenrat, T.; Ketudat-Cairns, M.; Stendahl-Andersen, H.; Jahic, M.; Enfors, S.O. Oxygen-limited fed-batch process: An alternative control for Pichia pastoris recombinant protein processes. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2005, 27, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenrat, T.; Ketudat-Cairns, M.; Jahic, M.; Veide, A.; Enfors, S.O. Increased total air pressure versus oxygen limitation for enhanced oxygen transfer and product formation in a Pichia pastoris recombinant protein process. Biochem. Eng. J. 2006, 30, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.F.; Yang, J.; Zhao, F.; Lin, Y.; Han, S. Comparative transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal the methanol dissimilation pathway of Pichia pastoris. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Smith, L.A.; Plantz, B.A.; Schlegel, V.L.; Meagher, M.M. Design of methanol Feed control in Pichia pastoris fermentations based upon a growth model. Biotechnol. Prog. 2002, 18, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadiut, O.; Dietzsch, C.; Herwig, C. Determination of a dynamic feeding strategy for recombinant Pichia pastoris strains. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1152, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.