Abstract

The global prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such as Staphylococcus aureus, presents a substantial challenge to public health, necessitating the development of innovative therapeutic strategies to combat these infections. This study examined the synergistic effects of a biosurfactant (BS) derived from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and a novel extract from Rosmarinus officinalis (RoME) obtained through supercritical CO2 extraction against S. aureus sourced from the microbiology laboratory at King Salman Hospital in Ha’il, Saudi Arabia. Antibacterial efficacy was determined using minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays, assessments of bacterial membrane damage, and qRT-PCR analysis of genes associated with antibiotic resistance. The findings revealed that the S. aureus strain exhibited resistance to multiple antibiotics with a resistance score of 0.44. RoME and BS demonstrated MICs of 0.125 mg/mL and 0.5 mg/mL, respectively. The assays indicated significant bacterial membrane damage and reduced expression of the norA, mdeA, and sel genes, which are implicated in resistance and virulence, respectively. The combination of BSs with plant extracts may provide innovative approaches for treating infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria, highlighting the potential of probiotic-derived BSs in combination with plant extracts.

1. Introduction

The impact of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial pathogens on global public health is increasing. As a result, conventional antibiotic use has become ineffective and poses a serious risk to animal and human health. One of the MDR pathogens we found was S. aureus. This Gram-positive bacterium is one of the principal causes of community- and healthcare-associated infections. It is responsible for many diseases, including nosocomial and skin infections and invasive diseases such as osteomyelitis, bacteremia, endocarditis, pneumonia, and sepsis. Because of its adaptability, the presence of numerous virulence determinants, and its ability to form and maintain biofilms, its survival in clinical and environmental areas has been enhanced [1].

The increase in cases of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is deeply concerning. These MRSA strains can develop resistance to β-lactam antibiotics due to the presence of the mecA gene, which codes for PBP2a, which poorly binds β-lactams. In addition, MRSA has gained resistance to several tetracycline and aminoglycoside antibiotics [2].

The development of antibiotics using conventional and traditional approaches cannot keep pace with the speed at which antibiotic resistance is increasing. Consequently, scientists have focused on antimicrobial agents derived from natural products, such as phytochemicals and microbial BSs, particularly those with multiple modes of action. These biomolecules offer promising applications in therapeutics, food, and cosmetics because of their antimicrobial, antiadhesive, antibiofilm, and immunomodulatory properties.

Amphiphilic BSs are a class of macromolecules usually produced by different types of microorganisms, such as bacteria, yeast, and fungi. These molecules differ in size and shape and can reduce surface and interfacial tensions, allowing them to disrupt the lipid membranes of target cells, leading to cell lysis and preventing the adhesion of microorganisms. Among bacterial strains that produce BSs, L. plantarum has been identified as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) [3] and recognized for its probiotic properties, along with other lactic acid bacteria (LAB) [4]. L. plantarum is commonly isolated from fermented foods and produces BSs with different bioactivities, such as antimicrobial, antiviral, and antifungal activities. These BSs can disrupt membranes and inhibit biofilm formation on medical and food processing [5].

The process through which L. plantarum-derived BSs act on pathogens such as S. aureus has many facets. Apart from membrane destabilization [6], there is the potential inhibition of the expression of efflux pumps [7] and the expression of quorum sensing systems that control the development of bacterial biofilms and the expression of their pathogenic potential and virulence [8].

Similar to BSs from microorganisms, antimicrobials derived from plants have been widely used to treat infections [9]. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) is a perennial herb of the family Lamiaceae, indigenous to the Mediterranean basin. Rosemary is used widely in the formulation of food, cosmetics and medicine due to its properties as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial herb [10,11]. It is a potential source of many bioactive compounds, such as rosmarinic acid, carnosic acid, carnosol, 1,8-cineole, camphor, borneol, a delicate mixture of herbs, and many other elements, all of which contribute to the biological activity of rosemary [11].

In most conventional methods used to extract bioactives from plants, organic solvents are usually used without regard to their impact on the stabilization and purity of sensitive compounds. Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) of carbon dioxide (CO2) coupled with ethanol as a co-solvent is a viable option [12,13]. Under moderate temperature and high pressure, SFE selectively extracts sensitive compounds without the use of toxic solvents [12,13]. RoME obtained through SFE also showed remarkable inhibition of bacterial growth such as S. aureus, Listeria monocytogenes and other Gram-positive bacteria. The antibacterial potency can be attributed to the high content of monoterpenes and diterpenes [14].

Interestingly, the combination of plant extracts and BSs produced some of the most potent antimicrobial compounds. BSs disturb membranes, while phytochemicals inhibit essential enzymes, break down DNA, or disrupt other biosynthetic processes at lower concentrations. Furthermore, the combined action has the potency of a broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, which reduces the resistance development [15].

In addition to phenotypic approaches, such as the determination of MIC and some tests for membrane integrity, some molecular approaches have also been adopted, such as the use of quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), which provides valuable information about the response of bacterial cells exposed to these agents at the transcriptional level [16]. The expression of genes such as norA and mdeA, which are involved in the encoding of efflux pumps, and sel, which greatly contributes to the supergene of the staphylococcal enterotoxins, are positive indicators of therapeutic virulence suppression and resistance pathways of the treatment. The expression of these genes also reflects pathogenicity to some extent, as well as the therapeutic potential of the approach [17].

In this context, this study aimed to determine the antibacterial effectiveness of BSs obtained from L. plantarum and RoME of supercritical CO2 extract, individually and in combination, on a clinically isolated MDR S. aureus strain. The study involved comprehensive characterization, including antimicrobial susceptibility testing through MIC determination, evaluation of bacterial membrane integrity, and analysis of gene expression using qRT-PCR. The main hypothesis is that the natural combination of these two biomolecules will possess more antibacterial activity than either product alone, which could serve as an environmentally friendly substitute for synthetic antibiotics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pathogenic Bacterial Strain and Culture Conditions

A clinical strain of multidrug-resistant S. aureus was obtained from the microbiology laboratory at King Salman Hospital in Ha’il, Saudi Arabia. The collected samples were cultured on blood and Baird Parker agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The purity of the suspected S. aureus isolate was confirmed by subculturing on mannitol salt agar. The S. aureus strain was determined by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and the sequence was registered under GenBank accession number PV474277.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ha’il Affairs (reference number HAP-08-L-158) in 5 May 2025. A consent form was deemed unnecessary because the isolates were obtained from the laboratory without direct patient interaction.

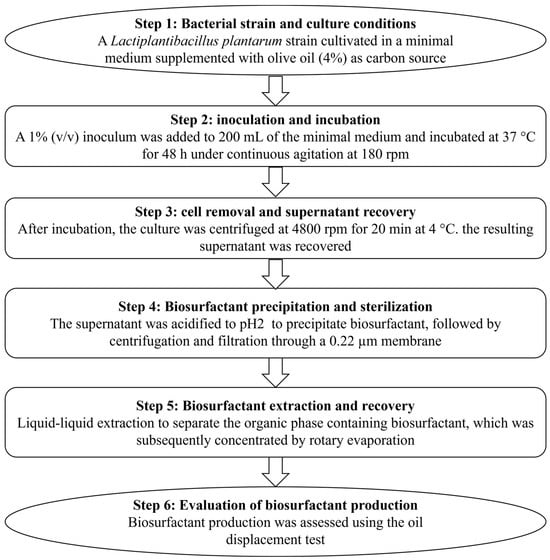

2.2. Production and Extraction of BS from L. plantarum

A L. plantarum strain isolated from traditional Tunisian fermented food [18] was used to generate BSs by growing the bacterial cells in a minimal medium containing sterile olive oil (4%) as the carbon source. To generate crude BS (Figure 1), a 1% overnight culture of L. plantarum was introduced into 200 mL of minimal medium and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h with continuous shaking at 180 rpm. Following incubation, the culture medium was centrifuged (4800 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C) to collect the cells and prevent protein compound denaturation. The supernatant was then acidified using a 0.4% HCl solution at pH 2 to precipitate the BSs. Subsequent centrifugation removed the bacteria, and the supernatant was collected after filtration through a 0.22 µm filter for sterilization. The mixture was vigorously stirred in a separatory funnel and left to settle for 5 min to separate the organic phase (containing the BS) from the aqueous phase. The organic phase was then dried using rotary evaporation under vacuum with a rotary evaporator (Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany) at 40 °C to eliminate ethyl acetate and retrieve the crude BS. The ability of L. plantarum to produce BSs was evaluated using an oil displacement test [19].

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the production and extraction of biosurfactants.

2.3. Oil Displacement Assay for BS Activity

BS production was assessed using the oil spread test, a widely recognized method for screening bacterial isolates [20,21]. This test utilizes the ability of BS to lower the surface tension as a key indicator [22]. The presence of a clear zone signifies BS production [23,24]. We employed an 85 mm diameter Petri dish filled with 20 mL of distilled water. Subsequently, 300 µL of the oil sample was carefully added to form a thin layer of oil on the water’s surface. An equal volume of the solution containing crude BS was applied to the oil surface. The diameter of the halo was measured and compared with that of the positive (0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)) and negative (distilled water) controls. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.4. Plant Material

Rosmarinus officinalis L. was collected from its natural environment in Sbikha Village/Maarouf, Kairouan (Tunisia) during the blooming period. A total of 1 Kg of the rosemary was dried in the shade at temperatures between 50 and 60 °C until it reached a moisture content of 8.4%. Subsequently, the dried plant material was finely milled using a laboratory grinder, resulting in particle sizes ranging from 500 to 1000 µm.

2.5. Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

SFE was performed using carbon dioxide in a pilot-scale supercritical fluid extractor (Aerospace Technology, Zunyi, China, model SUS304), which featured two extraction cells with volumes of 1 L and 5 L and two separators (S1 and S2). The extractor, measuring 50 mm in diameter and 250 mm in length, was filled with 100 g of dried and ground rosemary. The extraction was performed at a pressure of 15 MPa and a temperature of 45 °C, incorporating 7% (w/w) ethanol over a period of 180 min. The CO2 flow rate was maintained at 20 L·h−1 with slight modifications [25]. The supercritical extract (SFE) of rosemary was weighed and stored in the dark at +4 °C.

2.6. Study of Antibacterial Activity

2.6.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Assay

Following CA SFM/EUCAST 2025, the pathogenic strain was tested for susceptibility to different antimicrobials using the disk agar diffusion method. The antimicrobial susceptibility assay was performed using an overnight culture of the pathogen strain. The bacterial suspension was adjusted to approximately 1 × 106 CFU/mL. A variety of antibiotics (BioLab, Budapest, Hungary) were used to test the susceptibility of the identified S. aureus, including Tobramycin (10 µg), Gentamycin (10 µg), Kanamycin (30 µg), Erythromycin (15 µg), Clindamycin (2 µg), Norfloxacin (10 µg), Levofloxacin (5 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (1.25–23.75 µg), Linezolid (10 µg), Teicoplanin (30 µg), Vancomycin (5 µg), Tigecycline (15 µg), Tetracycline (30 µg), Cefoxitin (30 µg), Penicillin G (1 U), Oxacillin (1 µg), and Rifampicin (5 µg).

A list of antimicrobial disks used in this study and the results of the antibiograms are presented in Table 1. Assay results were collected 18–24 h after incubation at 37 °C.

Table 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility assay of the tested S. aureus (CA-SFM/EUCAST 2025).

2.6.2. Determination of Multiple Antibiotic Resistance Index (MAR) Index

The multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index for the S. aureus strain was calculated by dividing the number of antibiotics to which resistance was observed by the total number of antibiotics tested [26,27]. A MAR index greater than 0.2 suggests a source with frequent antibiotic exposure, while a MAR index of 0.2 or less indicates infrequent exposure to antimicrobials [28].

2.6.3. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the BS (1 mg/mL) derived from the probiotic strain and RoME (1 mg/mL) were assessed using a microdilution technique [29]. In summary, the bacterial strain was introduced into 3 mL of MH broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) and incubated overnight at 37 °C with constant agitation. The test solutions were dispensed into the wells of a 96-well plate (Corning, New York, NY, USA), with each well containing 200 µL of the solution. Subsequently, 20 µL of a bacterial suspension adjusted to a final optical density (OD) of 0.01 at 600 nm (Infinite F200 PRO, TECAN, Lyon, France), and 10 µL of resazurin were added to each well. After a 24 h incubation period at 37 °C, the OD was recorded at 600 nm using an ELISA reader (Infinite F200 PRO, TECAN). The MIC was defined as the concentration that inhibited bacterial growth. The negative control included only the medium, while the positive control contained only the inoculated bacteria without the test substances. All experiments were conducted in triplicates.

After determining the MICs for BS and RoME, three treatments were prepared. The first treatment used only BS, and the second treatment used RoME alone. In both assays, the concentration of each product was 1/4 of its MIC to avoid antibacterial effects. The third treatment combined BS and RoME, each at 1/4 of its MIC. For the second and third treatments, Tween 80 was added at a concentration of 5 mg/mL to ensure the complete miscibility of the RoME.

2.6.4. Bacterial Cell Membrane Disintegration Test

The purpose of this test was to determine whether BS, RoME, or a combination of BS and RoME could disturb cell membrane integrity. Bacterial suspensions were prepared using minimal medium. After 24 h of incubation at 37 °C, the cells were suspended in PBS (pH 7.4) after two washes. After the four treatments: an untreated control, biosurfactant (BS) alone, Rosmarinus officinalis extract (RoME) alone, and a combination of biosurfactant and Rosmarinus officinalis extract (BS + RoME), the bacterial strain was incubated at 37 °C for one hour. A 260 nm absorbance measurement was performed after the incubation period to assess whether ultraviolet-absorbing materials were released from the cells [30]. All experiments were conducted in triplicates. The presence of materials that absorb at 260 nm indicates the presence of proteins detached from the bacterial cell and, consequently, the membrane disintegration of the bacterial cells.

2.7. RNA Extraction

Each S. aureus bacterial culture, whether it was a control or treated with BS or RoME, was mixed with 1 mL RNA Protect Bacteria Reagent. The mixture was centrifuged at 5000× g for 10 min. The resulting cell pellet was subjected to total RNA extraction using the GF-1 Total RNA Extraction Kit protocol (Vivantis, Subang Jaya, Malaysia). Cell lysis was performed using a buffer containing guanidine isothiocyanate and lysozyme, followed by the addition of ethanol to optimize the RNA binding conditions. The prepared lysate was then applied to an RNeasy mini column to facilitate RNA purification.

2.8. RT-PCR Amplification

Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was performed as previously described by Xu et al. following the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription protocol (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) [31]. Briefly, RNA samples were mixed with a master mix containing Quantiscript Reverse Transcriptase, Quantiscript RT Buffer, RT Primer Mix, and RNase-free water. The mixture was incubated at 42 °C for 15 min, followed by a 3 min incubation at 95 °C to inactivate the reverse transcriptase. Custom oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technology, Inc. (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA) and used in this study (Table 2). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in a 20 μL reaction volume comprising 10 μL of QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 0.6 μL of 60 pmol primer, 2 μL of synthesized cDNA, and 6.8 μL RNase-free water. Amplification was conducted using the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 15 min, followed by 45 cycles at 94 °C for 15 s, 59 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 15 s. The PCR products were visualized and analyzed using the same detection systems. Relative gene expression levels between treated and untreated cells were calculated using the comparative Ct (ΔΔCt) method [31,32].

Table 2.

Primer sequences used in RT-PCR analysis for S. aureus.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean ± SD. To assess the statistical significance of each sample, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed, followed by the Student–Newman–Keuls test. The Levene test confirmed homogeneity of variance, and results with (p < 0.05) were considered significant. All data were processed using SPSS software (version 20, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Isolated S. aureus

As indicated in Table 1, the susceptibility of S. aureus PV474277 to a range of antibiotics, including Tobramycin, Gentamycin, Kanamycin, Erythromycin, Clindamycin, Norfloxacin, Levofloxacin, Ciprofloxacin, Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, Linezolid, Teicoplanin, Vancomycin, Tigecycline, Tetracycline, Cefoxitin, Penicillin G, Oxacillin, and Rifampicin, was assessed. S. aureus strain exhibited resistance to Kanamycin, Erythromycin, Ciprofloxacin, Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole, Tetracycline, Cefoxitin, Penicillin G, and Oxacillin, with a MAR index of 0.44, which is greater than 0.22%. A MAR index greater than 0.2 indicates that the patient has been frequently exposed to antibiotics.

3.2. Antibacterial Activity

In this study, an emulsion of RoME and L. plantarum BS was evaluated for its antagonistic potential against S. aureus. Based on the results obtained in Table 3, the extract had significant antagonistic effects on the target bacteria. Both the L. plantarum BS and RoME had MICs of 0.125 and 0.5 mg/mL against S. aureus (MRSA), respectively.

Table 3.

Antibacterial effect of BS and RoME against S. aureus and oil displacement.

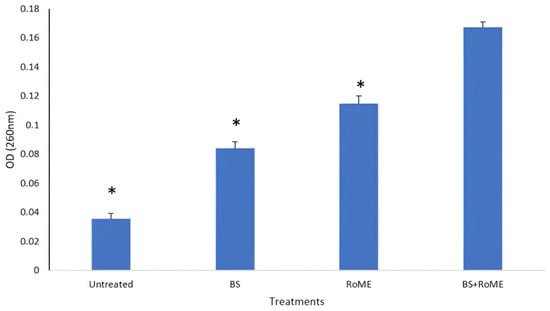

3.3. Bacterial Cell Membrane Disintegration Test

To provide insight into the possibility that the different treatments could have cell membrane disintegration potency in the tested pathogenic S. aureus, the absorbance of the supernatant at 260 nm was measured after treatment to examine the presence of any material released from the cell that absorbs ultraviolet light. Our findings showed that treatment with crude BSs and RoME can affect cell membrane disintegration in the tested pathogens. A significant difference was observed (p < 0.05) when compared with untreated strains. This was confirmed by the presence of UV-absorbing cellular products in the supernatant after treatment. The OD (260 nm) was approximately 0.01–0.04 for the untreated strains. After treatment with different formulations, the OD260 nm increased to values ranging from 0.08 to 0.2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of different treatments on bacterial cell membrane disintegration. BS: Biosurfatant only; RoME: rosemary extract; BS + RoME: Biosurfactant with rosemary extract. Asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference in the same line between the treated and non-treated cells.

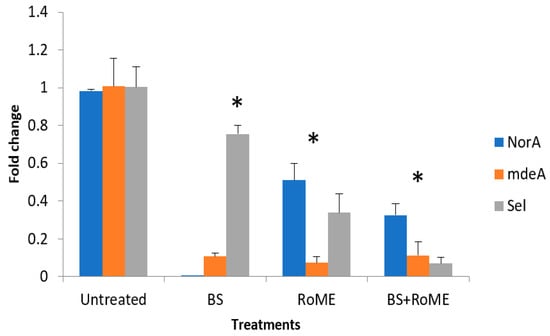

3.4. Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR was used to measure the transcription levels of certain key genes in S. aureus associated with efflux and virulence, including norA, mdeA, and sel. The results are summarized in Figure 3. Gene expression analysis revealed a significant modulation of the efflux pump-encoding genes (norA and mdeA) and sel gene encoding an enterotoxin that plays a role in virulence between treated and untreated strains. Our data revealed that all treatments resulted in downregulation of the target genes compared to the control (p < 0.05). The BS treatment produced a pronounced inhibitory effect particularly on norA expression (p < 0.05), while the RoME alone induced a significant reduction in the expression of different target genes (p < 0.05). The combined BS and RoME treatment exhibited a strong effect, leading to a highly significant decrease in the expression of all targeted genes (p < 0.05) compared to that of the untreated control and single-treatment groups. These results highlight the synergistic interaction between BS and RoME, enhancing their capacity to suppress efflux pumps and virulence gene expression in S. aureus.

Figure 3.

Expression levels of norA, mdeA, and sel genes. Control: Untreated bacteria; Treatment A: treatment with BS; Treatment B: treatment with RoME; Treatment C: treatment with BS and RoME. Asterisks (*) indicate a significant difference in the same line between the treated and non-treated cells.

4. Discussion

We investigated the antimicrobial properties of a BS derived from L. plantarum and a supercritical CO2 extract from R. officinalis against a clinical strain of multidrug-resistant S. aureus. The results indicated that both the BS and RoME exhibited significant antimicrobial effects. Moreover, combination therapy surpassed monotherapy in all evaluated aspects, including minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), damage to bacterial membranes, and the expression and reaction of resistance and virulence genes. The increasing prevalence of multidrug resistance and emergence of MRSA represent significant global public health challenges [34]. Indeed, in the absence of new antibacterial agents that surpass the effectiveness of current options against multidrug-resistant pathogenic strains, combination therapy has been investigated to enhance treatment outcomes [35]. The variation in the MAR index could be due to differences in the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant genes that lead to MDR [36]. A MAR index exceeding 0.2 indicates that the isolates come from a high-risk contamination source where antimicrobials are extensively used [37,38]. Strains that show resistance to at least one antimicrobial drug across three or more antimicrobial classes are classified as MDR strains [38]. This resistance is particularly notable against β-lactams, tetracyclines, and fluoroquinolones, as extensively documented in both clinical and hospital-acquired S. aureus [39]. The BS associated with L. plantarum is of notable interest because of its antibacterial effectiveness, with a MIC of 0.125 mg/mL, and its substantial oil displacement capability. This is attributed to the amphiphilic nature of BSs, which allows them to reduce surface tension, disrupt lipid membranes and inhibit bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [40]. These properties were confirmed in our results, which assessed membrane integrity and observed controlled lysis of nucleic acids and intracellular content following treatment. Recent research has underscored the disruptive impact of BSs from Gram-positive bacteria, such as Lactococcus and other LAB species, along with their low toxicity [41]. These BSs, considered GRAS, are being actively investigated for applications in food preservation and preventive antimicrobial treatment [42,43]. The extract of RoME, obtained through supercritical CO2 extraction, demonstrated moderate antibacterial activity, with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 0.5 mg/mL. However, previous studies have shown that R. officinalis exhibits antibacterial properties against various pathogens [44,45,46]. Supercritical extraction is valued for its ability to process thermolabile compounds and selectively concentrate antimicrobial phytochemicals, including carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid, and 1,8-cineole [47]. The literature corroborates this activity, indicating that these compounds may integrate into bacterial membranes, inhibit bacterial efflux pumps, and induce oxidative stress, culminating in bacterial death [6]. A recent study indicated that RoME, especially when extracted using methanol and ethyl acetate, demonstrated significant antibacterial and anti-biofilm properties against MRSA [48]. The mechanisms by which natural compounds exert anti-biofilm and anti-quorum-sensing effects on P. aeruginosa likely involve a variety of synergistic molecular and cellular targets [15]. For example, terpenes, found in essential oils, are recognized for their lipophilic characteristics, allowing them to integrate into bacterial cell membranes. This integration can result in membrane disruption, leading to increased permeability, changes in membrane potential, and ultimately the leakage of intracellular contents, which impairs bacterial viability and the metabolic functions necessary for biofilm development. Such damage to the membrane can also weaken efflux pumps, thereby boosting the effectiveness of antibiotics used in conjunction with them [49]. This integration can result in membrane disruption, leading to increased permeability, changes in membrane potential, and ultimately the leakage of intracellular contents, which impairs bacterial viability and the metabolic functions necessary for biofilm development. Such damage to the membrane can weaken efflux pumps, thereby boosting the effectiveness of antibiotics used in conjunction with them [48]. Another study revealed that the probiotic biosurfactant extracted exhibited potent antibiofilm effects against all the pathogens tested. This antibacterial property can be attributed to its capacity to modify cell physiology, including changes in hydrophobicity and membrane disruption [19,50].

While RoME demonstrated a lower potency compared to BS alone, its antibacterial efficacy was significant when used in conjunction with BS. A recent investigation that is in concordance with our findings revealed that the combination of crude RoME with tetracycline showed the greatest synergistic effect [51]. This pairing inhibited biofilm formation by 21.4% to 57.31% and led to a notable increase in fluorescence intensity of up to 14% in 75% of the extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains studied [51]. The combination between BS and RoME is particularly efficacious, as it reduces the MICs of both agents by 50% and significantly enhances membrane leakage and gene suppression as it was shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. These findings suggest that BS enhances membrane permeability, facilitating the retention of RoME’s lipophilic phytochemicals within the cytoplasm, thereby enhancing its antimicrobial efficacy. This combined effect is consistent with recent studies on microbial–phytochemical interactions targeting resistant pathogens [6,52]. Indeed, certain antibiotics like cefquinome and sulphaquinoxaline demonstrated a synergistic effect with rosemary ethanol extract against S. aureus [53]. RoME possesses notable antioxidant and antibacterial qualities; however, its use in aqueous environments is restricted due to its minimal solubility in water because of its highly hydrophobic nature [54,55]. Consequently, a recent study by Park et al. (2020) [52] explored the micellar solubilization of RoME using four different surfactants (Tween 20, polyglyceryl-10-laurate, polyglyceryl-10-myristate, and polyglyceryl-10-monooleate) to boost its water solubility. The results were consistent with our findings and showed that the addition of surfactants to the RoME solution significantly enhanced its water solubility, with polyglyceryl-10-monooleate, which has the longest tail, being the most effective [56]. The combined effect was examined not only for RoME but also for other plant extracts. A recent study revealed that combining thyme extract with biosurfactants results in antibacterial, anti-biofilm, and synergistic properties, proving effective against both antibiotic-resistant and non-resistant pathogenic bacteria [15]. Previous studies have suggested that these compounds may simplify drug penetration through the outer layers of bacterial cell walls, block the inhibitory effect of protective enzymes, and interfere with the metabolic targets of antibiotics [52].

Post-treatment analysis revealed a marked reduction in the expression levels of three genes: norA (efflux pump), mdeA (multidrug efflux A), and sel (staphylococcal enterotoxin) (Figure 3). The combination treatment achieved a 55% suppression of the norA gene, which is frequently examined because of its association with fluoroquinolone resistance [57]. The mdeA gene, which is involved in multidrug efflux, exhibited a 50% decrease in expression. Furthermore, sel, a virulence factor, was significantly suppressed. Consequently, the combined treatment not only demonstrates bactericidal properties but also effectively targets the resistance and virulence mechanisms of the pathogen [58]. Research has indicated that natural compounds can influence crucial resistance and virulence genes in S. aureus, particularly the efflux pumps norA and mdeA, which are associated with resistance to fluoroquinolones, biocides, and multiple drugs [57,59]. Phytochemicals derived from R. officinalis, such as carnosic acid and carnosol, have been found to significantly affect norA, thereby decreasing efflux activity and increasing the accumulation of antibiotics within cells [55]. Recent studies have shown that essential oils and metabolites resembling biosurfactants can inhibit efflux-pump systems, such as norA and mdeA, in both MRSA and methicillin sensitive S. aureus strains (MSSA) [60]. Additionally, plant extracts can downregulate virulence genes, such as sel, by interfering with global regulators, such as agr and sarA, resulting in reduced expression of enterotoxins at subinhibitory concentrations [61,62].

In S. aureus grown at pH 5.5, norB and mdeA remained stable. Increased resistance to various antibiotics is facilitated by the expression of many genes including mdeA in S. aureus [63,64]. The consistent expression of norB, norC, and mdeA in S. aureus may be crucial for antibiotic resistance in anaerobic environments, leading to heightened virulence when S. aureus encounters the gastrointestinal tract [17]. During biofilm formation by S. aureus, the expression of efflux pumps and virulence-related genes may be altered. This observation supports earlier findings that antibiotic resistance observed in biofilm cells is linked to increased virulence. Modulating these genes could provide clinical benefits beyond bacterial eradication, such as reducing infection severity and decreasing the likelihood of recurrence. The suggested dual-agent approach offers significant benefits. The GRAS status of the RoME and the outstanding biocompatibility of BS make them ideal for use in topical formulations, wound dressings, and coatings for medical devices. Their efficacy against multidrug-resistant strains further supports their use as adjuncts in antibiotic therapy, either to restore susceptibility or to reduce the required antibiotic dosage. In the context of food safety, these formulations can serve as biopreservatives, targeting pathogens that persist after food processing [14]. This study demonstrated that a BS from L. plantarum combined with an SC–CO2 RoME exhibited significant synergistic antibacterial effects against MDR S. aureus. This combination not only reduces bacterial populations but also disrupts membrane integrity and suppresses key resistance and virulence characteristics of bacteria. These findings underscore the need for further investigation into the application of biocompatible antimicrobial agents derived from plants and microbes. In light of the impending antibiotic resistance crisis, this approach offers an innovative and sustainable addition to the expanding repertoire of multitargeted antimicrobial therapies.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the integration of a BS derived from the bacterium L. plantarum with RoME absorbed by supercritical CO presents a promising synergistic strategy to address multidrug-resistant (MDR) S. aureus. The BS exhibited potent surface-active and antibacterial properties, while the RoME provided additional phytochemical-based inhibition. Notably, the combination therapy resulted in reduced minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, enhanced membrane disruption, and significant downregulation of key antimicrobial efflux pumps and virulence genes (norA, mdeA, and sel), underscoring its multi-targeted antimicrobial effects. The observed synergy between the BS and RoME appears to arise from a cooperative mechanism, wherein the capacity of the BS to permeabilize membranes facilitates the penetration of phytochemical antimicrobial agents into cells, thereby augmenting their efficacy. This combination not only enhances bacterial eradication but also diminishes the likelihood of developing resistant strains, which is a growing concern in the context of escalating antibiotic resistance.

The inherent natural origins, biodegradability, and biocompatibility of both the BS and RoME position their combined application as particularly advantageous for clinical treatments, antimicrobial topical gels, coatings to prevent biofilm formation on medical devices, and ensuring food safety. However, the broader clinical or commercial implementation of this technology may be constrained until further strain testing, in vivo anti-staphylococcal efficacy testing, and safety evaluations are conducted. This study contributes to the expanding field of alternative antimicrobials and underscores the significance of integrating microbial BSs with plant extracts to address the escalating challenge of multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation: N.H. and A.M.; data curation, W.R. and A.S.A.; funding acquisition, N.H.; investigation, N.L. and M.O.A.; methodology, A.M. and N.H.; project administration, N.H. and A.M.; software, N.L. and W.R.; validation and visualization, H.M.; writing—original draft, N.H.; writing—review and editing, N.H. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il—Saudi Arabia through project number <<RCP-24 086>>.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ha’il Affairs (reference number HAP-08-L-158) in 5 May 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

A consent form was deemed unnecessary because the isolates were obtained from the laboratory without direct patient interaction.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il—Saudi Arabia through project number <<RCP-24 086>>.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tong, S.Y.; Fowler, V.G.; Skalla, L.; Holland, T.L. Management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: A review. JAMA 2025, 334, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhundi, S.; Zhang, K. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00020-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21, Volume 3, Chapter 1. Part 182, Substances Generally Recognized as Safe, Subpart A, General Provision, Section 182.20, Essential Oils, Oleoresins (Solvent Free), and Natural Extractives (Including Distillates); Office of the Federal Register National Archives and Records: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mouafo, H.T.; Sokamte, A.T.; Manet, L.; Mbarga, A.J.M.; Nadezdha, S.; Devappa, S.; Mbawala, A. Biofilm inhibition, antibacterial and antiadhesive properties of a novel biosurfactant from Lactobacillus paracasei N2 against multi-antibiotics-resistant pathogens isolated from braised fish. Fermentation 2023, 9, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, A.N.; Prapulla, S.G. Evaluation and functional characterization of a biosurfactant produced by Lactobacillus plantarum CFR 2194. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 172, 1777–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, M.T.; Russo, P.; Capozzi, V.; Drider, D.; Spano, G.; Fiocco, D. Bioprospecting antimicrobials from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: Key factors underlying its probiotic action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdhi, A.; Leban, N.; Chakroun, I.; Bayar, S.; Mahdouani, K.; Majdoub, H.; Kouidhi, B. Use of extracellular polysaccharides, secreted by Lactobacillus plantarum and Bacillus spp., as reducing indole production agents to control biofilm formation and efflux pumps inhibitor in Escherichia coli. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 125, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Gu, S.; Cui, X.; Shi, Y.; Wen, S.; Chen, H.; Ge, J. Antimicrobial, anti-adhesive and anti-biofilm potential of biosurfactants isolated from Pediococcus acidilactici and Lactobacillus plantarum against Staphylococcus aureus CMCC26003. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 127, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Savoia, D. Plant-derived antimicrobial compounds: Alternatives to antibiotics. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 979–990. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, G.; Ros, G.; Castillo, J. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis, L.): A review. Medicines 2018, 5, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.; Junghanns, W. Rosmarinus officinalis L.: Rosemary. In Medicinal, Aromatic and Stimulant Plants; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 501–521. [Google Scholar]

- Reverchon, E.; Della Porta, G.; Gorgoglione, D. Supercritical CO2 extraction of volatile oil from rose concrete. Flavour Fragr. J. 1997, 12, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Porto, C.; Decorti, D.; Natolino, A. Application of a supercritical CO2 extraction procedure to recover volatile compounds and polyphenols from Rosa damascena. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Y.; Velamuri, R.; Fagan, J.; Schaefer, J. Full-spectrum analysis of bioactive compounds in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) as influenced by different extraction methods. Molecules 2020, 25, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, A.; Allahri, F.B.; Samian, P.; Najarkolaee, S.M.G.; Yusofvand, R.; Eslammanesh, T.; Hassanshahi, M. Investigating The Synergistic and Antimicrobial Effect of Glycolipid Biosurfactants Produced by Shewanella alga 12B and Bacillus pumilus SG Bacteria with Thyme Plant Extract on Some Pathogenic Bacteria. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci. 2024, 26, e157556. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, W.; Meldrum, D.R. RT-qPCR based quantitative analysis of gene expression in single bacterial cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 85, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Ahn, J. Differential gene expression in planktonic and biofilm cells of multiple antibiotic-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 325, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Slama, R.; Kouidhi, B.; Zmantar, T.; Chaieb, K.; Bakhrouf, A. Anti-listerial and anti-biofilm activities of potential Probiotic Lactobacillus strains isolated from Tunisian traditional fermented food. J. Food Saf. 2013, 33, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Haddaji, N.; Ncib, K.; Bahia, W.; Ghorbel, M.; Leban, N.; Bouali, N.; Bechambi, O.; Mzoughi, R.; Mahdhi, A. Control of multidrug-resistant pathogenic staphylococci associated with vaginal infection using biosurfactants derived from potential probiotic Bacillus strain. Fermentation 2022, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, M.I.; Gayathiri, S.; Gnanaselvi, U.; Jenifer, P.S.; Raj, S.M.; Gurunathan, S. Novel lipopeptide biosurfactant produced by hydrocarbon degrading and heavy metal tolerant bacterium Escherichia fergusonii KLU01 as a potential tool for bioremediation. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 9291–9295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, S.; Ahmad, S.A.; Wan Johari, W.L.; Abd Shukor, M.Y.; Alias, S.A.; Smykla, J.; Saruni, N.H.; Abdul Razak, N.S.; Yasid, N.A. Production of lipopeptide biosurfactant by a hydrocarbon-degrading Antarctic Rhodococcus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnif, S.; Chamkha, M.; Labat, M.; Sayadi, S. Simultaneous hydrocarbon biodegradation and biosurfactant production by oilfield-selected bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Soni, J.; Kaur, G.; Kaur, J. A study on biosurfactant production in Lactobacillus and Bacillus sp. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 723–733. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan, C.N.; Cooper, D.G.; Neufeld, R.J. Selection of microbes producing biosurfactants in media without hydrocarbons. J. Ferment. Technol. 1984, 62, 311–314. [Google Scholar]

- Dhouibi, N.; Manuguerra, S.; Arena, R.; Mahdhi, A.; Messina, C.M.; Santulli, A.; Dhaouadi, H. Screening of antioxidant potentials and bioactive properties of the extracts obtained from two Centaurea L. Species (C. kroumirensis Coss. and C. sicula L. subsp sicula). Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titilawo, Y.; Sibanda, T.; Obi, L.; Okoh, A. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of faecal contamination of water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10969–10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumperman, P.H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thenmozhi, S.; Rajeswari, P.; Kumar, B.S.; Saipriyanga, V.; Kalpana, M. Multi-drug resistant patterns of biofilm forming Aeromonas hydrophila from urine samples. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2014, 5, 2908–2918. [Google Scholar]

- Sundheim, G.; Hagtvedt, T.; Dainty, R. Resistance of meat associated staphylococci to a quarternary ammonium compound. Food Microbiol. 1992, 9, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Zhou, W.; Li, P.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Y. Mode of action of pentocin 31-1: An antilisteria bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus pentosus from Chinese traditional ham. Food Control 2008, 19, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Lee, H.; Ahn, J. Growth and virulence properties of biofilm-forming Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium under different acidic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7910–7917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latteef, N.S.; Salih, W.Y.; Abdulhassan, A.A.; Obeed, R.J. Evaluation of gene expression of norA and norB gene in ciproflaxin and levofloxacin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Arch. Razi Inst. 2022, 77, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Mahato, R.P.; Ch, S.; Kumbham, S. Current strategies against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and advances toward future therapy. Microbe 2025, 6, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellberg, B.; Bonomo, R.A. Combination therapy for extreme drug–resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Ready for prime time? Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1332–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Kimera, Z.I.; Mshana, S.E.; Rweyemamu, M.M.; Mboera, L.E.; Matee, M.I. Antimicrobial use and resistance in food-producing animals and the environment: An African perspective. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saber, T.; Samir, M.; El-Mekkawy, R.M.; Ariny, E.; El-Sayed, S.R.; Enan, G.; Abdelatif, S.H.; Askora, A.; Merwad, A.M.; Tartor, Y.H. Methicillin-and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from humans and ready-to-eat meat: Characterization of antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation ability. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 735494. [Google Scholar]

- Badawy, B.; Gwida, M.; Sadat, A.; El-Toukhy, M.; Sayed-Ahmed, M.; Alam, N.; Ahmad, S.; Ali, M.S.; Elafify, M. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of virulent Listeria monocytogenes and Cronobacter sakazakii in dairy cattle, the environment, and dried milk with the in vitro application of natural alternative control. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, T.J. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Ashraf, S.A.; Surti, M.; Awadelkareem, A.M.; Snoussi, M.; Hamadou, W.S.; Bardakci, F.; Jamal, A.; Jahan, S.; et al. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum-derived biosurfactant attenuates quorum sensing-mediated virulence and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Chromobacterium violaceum. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1026. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, B.; Kaur, S.; Dwibedi, V.; Albadrani, G.M.; Al-Ghadi, M.Q.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Unveiling the antimicrobial and antibiofilm potential of biosurfactant produced by newly isolated Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strain 1625. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1459388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banat, I.M.; Makkar, R.S.; Cameotra, S.S. Potential commercial applications of microbial surfactants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 53, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, M.; Costa, S. Biosurfactants in food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, M.; Karygianni, L.; Argyropoulou, A.; Anderson, A.C.; Hellwig, E.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Wittmer, A.; Vach, K.; Al-Ahmad, A. The antimicrobial effect of Rosmarinus officinalis extracts on oral initial adhesion ex vivo. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 4369–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manilal, A.; Sabu, K.R.; Woldemariam, M.; Aklilu, A.; Biresaw, G.; Yohanes, T.; Seid, M.; Merdekios, B. Antibacterial activity of Rosmarinus officinalis against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates and meat-borne pathogens. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6677420. [Google Scholar]

- Del Campo, J.; Amiot, M.; Nguyen-The, C. Antimicrobial effect of rosemary extracts. J. Food Prot. 2000, 63, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Camargo, A.d.P.; García-Cañas, V.; Herrero, M.; Cifuentes, A.; Ibáñez, E. Comparative study of green sub- and supercritical processes to obtain carnosic acid and carnosol-enriched rosemary extracts with in vitro anti-proliferative activity on colon cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khashei, S.; Fazeli, H.; Rahimi, F.; Karbasizadeh, V. Antibiotic-potentiating efficacy of Rosmarinus officinalis L. to combat planktonic cells, biofilms, and efflux pump activities of extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strains. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1558611. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-El Tawab, A.A.; El-Hofy, F.I.; Mobarez, E.A.; Taha, H.S.; Tawkol, N.Y. Synergistic effect between some antimicrobial agents and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) toward Staphylococcus aureus–in-vitro. Benha Vet. Med. J. 2015, 28, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourabiti, F.; Derdak, R.; El Amrani, A.; Momen, G.; Timinouni, M.; Soukri, A.; El Khalfi, B.; Zouheir, Y. The antimicrobial effectiveness of Rosmarinus officinalis, Lavandula angustifolia, and Salvia officinalis essential oils against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in silico. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 168, 112–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Smuts, J.P.; Dodbiba, E.; Rangarajan, R.; Lang, J.C.; Armstrong, D.W. Degradation study of carnosic acid, carnosol, rosmarinic acid, and rosemary extract (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) assessed using HPLC. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9305–9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Mun, S.; Kim, Y. Influences of added surfactants on the water solubility and antibacterial activity of rosemary extract. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.Y.; Trucksis, M.; Hooper, D.C. Quinolone resistance mediated by norA: Physiologic characterization and relationship to flqB, a quinolone resistance locus on the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussama, B.K.; Fatima, S.; Djilali, B.; Rym, B. The Combined effect of Rosmarinus officinalis L essential oil and Bacteriocin BacLP01 from Lactobacillus plantarum against Bacillus subtilis ATCC11778. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 7, 2551–2557. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; O’Toole, P.W.; Shen, W.; Amrine-Madsen, H.; Jiang, X.; Lobo, N.; Palmer, L.M.; Voelker, L.; Fan, F.; Gwynn, M.N.; et al. Novel chromosomally encoded multidrug efflux transporter MdeA in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.; Abrantes, P.; Costa, S.S.; Viveiros, M.; Couto, I. Occurrence and variability of the efflux pump gene norA across the Staphylococcus genus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, S.; Hillebrand, G.G.; Nunez, G. Rosmarinus officinalis L. (rosemary) extracts containing carnosic acid and carnosol are potent quorum sensing inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.A.M.; Abdelgalil, S.Y.; Khamis, T.; Abdelwahab, A.M.; Atwa, D.N.; Elmowalid, G.A. Thymoquinone’potent impairment of multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus NorA efflux pump activity. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16483. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, A.; Mooyottu, S.; Yin, H.; Nair, M.S.; Bhattaram, V.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Inhibiting microbial toxins using plant-derived compounds and plant extracts. Medicines 2015, 2, 186–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Onodera, Y.; Lee, J.C.; Hooper, D.C. NorB, an efflux pump in Staphylococcus aureus strain MW2, contributes to bacterial fitness in abscesses. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 7123–7129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Høiby, N.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Givskov, M.; Molin, S.; Ciofu, O. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2010, 35, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, R.; Berry, V. Bacterial biofilm formation, pathogenicity, diagnostics and control: An overview. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2009, 63, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Darie-Niţă, R.N.; Vasile, C.; Stoleru, E.; Pamfil, D.; Zaharescu, T.; Tarţău, L.; Tudorachi, N.; Brebu, M.A.; Pricope, G.M.; Dumitriu, R.P.; et al. Evaluation of the rosemary extract effect on the properties of polylactic acid-based materials. Materials 2018, 11, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Mendoza, L.; Guamba, E.; Miño, K.; Romero, M.P.; Levoyer, A.; Alvarez-Barreto, J.F.; Machado, A.; Alexis, F. Antimicrobial properties of plant fibers. Molecules 2022, 27, 7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.