Abstract

This study reports the isolation, identification, and functional characterization of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) obtained from the endogenous fermentation of Theobroma bicolor (pataxte), an understudied Mesoamerican species with unexplored biotechnological potential. Five lactic acid bacteria strains were isolated and selected for comprehensive in vitro evaluation of their probiotic attributes. The assays included antimicrobial activity (disk diffusion and minimum inhibitory concentration), tolerance to simulated gastrointestinal conditions, and comparison of survival between non-encapsulated and bigel-encapsulated cells during digestion. All five isolates demonstrated notable antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella Enteritidis ATCC 13076, and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923. Strain S1.B exhibited exceptional resistance to acidic pH (2.0) and bile salts, reaching 3.61 ± 0.00 log (CFU/mL) after gastrointestinal simulation. The strain was identified as Lactiplantibacillus pentosus via 16S rRNA gene sequencing, marking the first documented isolation of this species from pataxte fermentation. Bigel encapsulation markedly enhanced its survival, increasing viability to 5.08 ± 0.10 log (CFU/mL). These findings identify Lactiplantibacillus pentosus 124-2 as a potential probiotic candidate originating from pataxte fermentation and highlight bigel systems as powerful vehicles for bacterial protection. Collectively, this work expands the microbial biodiversity known in Theobroma fermentations and underscores their promise for future functional food applications.

1. Introduction

The genus Theobroma comprises twenty-two species that are endemic to Central and South America; in Mexico, two species are found, Theobroma cacao L. and Theobroma bicolor L. [1]. Theobroma bicolor L. is a tree that belongs to the family Malvaceae; in Mexico, it is known as pataxte, patashe, or cacao cimarron [2]. Pataxte grows in regions with temperatures between 28 °C and 30 °C; in this context, its presence is also reported in countries such as Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and Suriname [3,4,5].

The nutritional characteristics of the pataxte have been reported scarcely; according to Diaz & Hernandez [1], it has a high content of unsaturated fatty acids, specifically oleic acid (C18:1) and gadoleic acid (C20:1). In the same context, according to Benlloch-Tinoco et al. [6], the pataxte has a high content of lipids in the seed, especially oleic acid (C18:1) (40.6%), stearic acid (C18.0) (47.5%), palmitic acid (16:0) (7.9%), linoleic acid (C18:2) (1.9%) and eicosanoid acid (C20:0) (1.8%). Additionally, its seeds are rich in minerals, particularly magnesium and iron [7]. Crucially, Theobroma bicolor is the Theobroma with the highest dietary fiber content (3.1 g/100 g) [3]. This high fiber density, combined with the abundance of phenolic compounds and flavonoids in the pulp [1], suggests that pataxte serves as a natural prebiotic potential matrix. These components not only provide nutritional value but also act as selective substrates that can promote the growth of specific beneficial microorganisms during processing [8,9].

In contrast to the extensive body of research on Theobroma cacao fermentation [10], scientific information regarding the fermentation process and associated microbiota of Theobroma bicolor remains limited. Cocoa fermentation is a well-characterized process typically lasting five to seven days, and involving a succession of microbial activities that strongly influence final product quality [11,12,13]. Numerous studies have documented a high diversity of lactic acid bacteria associated with cocoa fermentations, including species from the genera Lactiplantibacillus, Leuconostoc, Weissella, Pediococcus, Lactococcus, and Fructobacillus, which have been isolated from different geographic regions and fermentation conditions [14,15,16,17]. However, the unique high-fiber and polyphenolic environment of Thebroma biocolor represents a distinct ecological niche [1,3]. Screening for LAB from this unconventional substrate is particularly promising, as autochthonous strains must adapt to metabolize complex non-digestible carbohydrates [18]. Consequently, pataxte fermentations could harbor novel probiotic candidates with superior robustness and unique metabolic capabilities compared to those found in more common sources.

In this context, probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate quantities, confer a health benefit to the host [19]; for a microorganism to be classified as a probiotic, it must meet a series of requirements, among which the following standout (1) be correctly identified, (2) not be pathogenic by nature, (3) be resistant to destruction by gastric secretions and bile, (4) must have the ability to adhere to the intestinal epithelium, as well the ability to colonize the gastrointestinal tract, even for short periods, (5) produce antimicrobial substances and (6) be in sufficient quantity to be able to exert the desired effect [19,20]. However, maintaining probiotic viability during processing, storage, and passage through the gastrointestinal tract remains a major technological challenge [21,22].

In this context, protective delivery systems have gained increasing attention, among which bigels represent a promising emerging technology [23]. Bigels can be defined as topical formulations obtained by the combination of a water system (hydrogels) and a lipophilic system (oleogels), which gives it characteristics of both gels [24]; the two constituent gels can be of the same or different colloidal phase or they can be a mixture of a hydrogel and an oleogel mixed in different proportions [25]. Recently, the use of bigels as carriers of probiotics has been proposed [26]; the capsule generates a protection that acts as a barrier between bacteria and the destructive environmental conditions of the digestive tract [24].

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have reported the isolation and identification of lactic acid bacteria from endogenous fermentation with Theobroma bicolor [3,6,27,28]. Therefore, this study aimed to (1) isolate lactic-acid bacteria resulting from endogenous fermentation of pataxte following the fermentation methodology of the cacao, (2) perform a preliminary screening of the isolated strains based on selected probiotic-related functional traits, and (3) investigate the protective effect of bigel encapsulation on the viability of selected LAB strains under simulated gastrointestinal conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

The pataxte used in this study was harvested in the municipality of San Bautista Valle Nacional, state of Oaxaca, Mexico, with an average annual precipitation of 4100 mm and a temperature of 25 °C. The pataxte fruits were opened manually, the shell was discarded, the pulp and seeds were divided into batches of 500 g, and introduced into vacuum bags; subsequently, each bag was vacuum sealed using a packaging machine (Torrey, Nuevo León, Mexico). To preserve the raw material prior to experimentation, the samples were stored in freezing conditions (−18 °C). For the production of bigel, carrageenan (MSC®, Puebla, Mexico), alginate (MCS®, Puebla, Mexico), canola oil and soy lecithin (Gel Caps, Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico) were used.

2.2. Biological Material

For this study, pathogenic strains including E. coli ATCC 25922, S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076, and S. aureus ATCC 25923 were provided by the Public Health Institute of the State of Puebla.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Fermentation

Before fermentation assays, the samples were thawed at refrigeration temperature (4 °C). Endogenous fermentation was carried out in a rectangular plastic box with dimensions of 60 cm × 40 cm × 30 cm [13]. The grains of the pataxte were covered with adhesive plastic which was perforated allowing adequate aeration of pataxte grains. The fermentation was carried out for a period of five days at 25 °C, and the grains were rotated every two days [29].

2.3.2. Physicochemical Properties of Fermentation

pH

The pH was measured according to the methodology of the AOAC (2000 [30]) (N° 970.21); readings were taken every twenty-four hours.

Titratable Acidity

The titratable acidity was carried out according to the methodology of the AOAC (2000 [30]) (N° 942.15); readings were taken every twenty-four hours.

2.3.3. Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria

Initially, 10 g of the fermented and ground pataxte grains were placed in 90 mL of 0.9% saline solution; subsequently, serial dilutions were made by adding the first 900 μL of saline solution and 100 μL of ground pataxte with the saline solution (10−1 to 10−6). Later, 100 μL of the serial dilutions were taken and spread onto the surface of pre-dried de Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) agar (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) media. MRS agar was selected for its acidic pH and selective composition, such as sodium acetate and ammonium citrate, which suppresses the growth of competing flora [31]. To further ensure the selection of LAB and inhibit the proliferation of obligate aerobic yeasts and molds commonly found in fermented grains, plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h [32].

After incubation, a first round of purification was performed by selecting colonies with glistening white coloration, the presence of clear zone surrounding the colony, a diameter ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 mm, and non-filamentous morphology, which were re-streaked onto fresh MRS agar and incubated under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 48 h. The resulting isolates were subjected to a catalase test. Only catalase-negative isolates were subjected to a second purification step by streaking onto MRS agar supplemented with 1.2% mannitol. These purified colonies were incubated under the same conditions to ensure isolate stability and purity.

2.3.4. Morphological Examination

Gram Staining

Gram staining was carried out according to the methodology of [33]. It began by identifying the sample with a 40× lens in an optical Olympus CX22LED microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and finally, a 100× lens was used with the aid of immersion oil.

2.3.5. Biochemical Identification

Catalase Test

An isolated colony was taken on MRS agar and fixed on a slide; subsequently, a drop of 30% hydrogen peroxide was added to the sample. LAB, being anaerobic bacteria, do not have the enzyme catalase, so they cannot decompose hydrogen peroxide into oxygen and water [34].

2.3.6. Antimicrobial Activity

Kirby-Bauer Test

100 μL of pathogenic bacteria (E. coli, S. Enteritidis, and S. aureus with a concentration equal to 0.5 of McFarlane’s were plated on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar (BD Bioxon, Mexico City, Mexico). Subsequently, 100 μL of the cell-free supernatant (CFS) from each LAB culture (previously grown in MRS broth for 48 h) was placed on a previously sterilized filter-paper disk. These disks were placed on the MH agar plates with the pathogenic bacteria inoculated; the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h to allow the development of pathogenically bacterial lawn. Finally, the antibacterial activity of the LAB was expressed as the diameter of the clear area formed using a vernier caliper. Measurements were performed in triplicate [35].

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

Serial dilutions were made in a 96-well microplate with MH broth (BD Bioxon, Mexico City, Mexico); two controls were used; the first was the control (C), which corresponds to MH broth (100 μL) without bacterial suspension and the second was positive control (C+) which corresponds to 50 μL MH broth and 50 μL of pathogenic bacteria (E. coli, S. aureus, and S. Enteritidis), D1 (dilution 1) consists of 100 μL of LAB supernatant (of which 50 μL were taken for D2) and 50 μL of the pathogenic bacteria, D2 consist of 50 μL MH, 50 μL of LAB supernatant (of which 50 μL were taken) and 50 μL of pathogenic bacteria. A microplate reader (Thermo scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a 620 nm wavelength filter was used; measurements were performed in duplicate.

The MIC90 was defined as the lowest concentration of LAB supernatant capable of inhibiting at least 90% of bacterial growth compared to the positive control, and this criterion was used for MIC determination. MIC90 values were expressed as percentage (v/v) of LAB cell-free supernatant relative to the assay volume (100 μL per well), since antimicrobial activity was evaluated using volumetric dilutions rather than mass-based concentrations.

2.3.7. Identification of Isolated Bacteria by MALDI-TOF MS

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France), is an emerging technology used for bacterial identification and strain typing [36]. MALDI-TOF MS generates ions from a sample, separates the generated ions from a sample, and then separates the generated ions based on the mass-to-charge ratio in the gas phase [37].

The isolated bacteria were sub-cultured on Blood Agar Base medium (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany); the plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h. Blood Agar Base medium ensures protein expression and reliable mass spectral profiles for bacterial identification [36].

Subsequently, a colony of the isolated bacteria was taken and dispersed on the plate (DS-22-45-96847) (BioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France) , and 1 μL of CHCA (a-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) matrix was added to the colony in each of the wells; an E.coli ATCC 8739 strain was used for calibration. Finally, the plate was left to dry at room temperature and introduced into the VITEK® MS JL/VE/1208 machine (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). The procedure was carried out in duplicate.

2.3.8. Molecular Identification of the Selected LAB Strain and Phylogenetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using a lysis buffer protocol [38,39,40]. The extracted DNA was stored at −20° C until further processing. Amplification of the 16S rRNA gene (approximately 1550 bp) was performed using universal primers [39]. The PCR products were sequenced bidirectionally using the Sanger dideoxy-terminal method (Sanger et al., 1977 [41]). Sequencing reactions were performed with the BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems™, Foster City, CA, USA; REF 4404312), run on a 3500/Flex Series Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems™, REF 4404312), and analyzed on a 3500/Flex Series Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems™). Sequencing was carried out in both forward and reverse directions [38,39,40].

The raw chromatogram files generated by capillary electrophoresis were manually curated using Chromas v2.6.6 (Technelysium Pty Ltd., Victoria, QLD, Australia; free version), with visual inspection of peak height and resolution for each nucleotide. Sequence assembly was performed using DNA Baser v5.21.0BT (Heracle BioSoft, Pitesti, Romania), aligning forward and reverse reads into a single consensus sequence in FASTA format. The resulting consensus 16s rRNA gene sequence was used for taxonomic identification by sequence alignment against the curated NCBI database “16S ribosomal RNA (Bacteria and Archaea type strains)” using BLASTn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), accessed on 27 December 2025 . Sequence similarity was evaluated based on query coverage, E-value, and percentage identity. The isolate was assigned to the closest taxonomic match according to the highest sequence identity with reference type strains.

For the phylogenetic analysis, all sequences were aligned using Clustal W, and the resulting multiple sequence alignment was manually inspected to remove poorly aligned regions and excessive gaps. A phylogenetic tree was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method, and branch support was assessed by bootstrap analysis with 100 replicates. The final tree was rooted using the selected group and visualized for interpretation.

2.3.9. Bigel Preparation

For the hydrogel preparation, two separate polymeric dispersions of alginate and carrageenan were formulated with concentrations of 3.5% and 4% (w/v), respectively. The dispersions were prepared using a food processor (Thermomix TM31, Vorwerk, Wuppertal, Germany) at 60 °C, starting at 1133 rpm and gradually increasing to 3399 rpm for 30 min from when the dispersion reached 60 °C. After the homogenization of each polymeric dispersion, they were mixed at a 50:50 ratio. For the oleogel formulation, the hydrogel was homogenized using a food processor (Thermomix TM31, Vorwerk, Wuppertal, Germany) at 10,200 rpm, and oil was added gradually. The oil was previously mixed with 0.44% of lecithin in a slow and completely cold stream. The bigel ratio was 70:30 (hydrogel–vegetable oil).

2.3.10. Encapsulation of Bacterial Strains

For the encapsulation of bacterial strains, 5 mL of the biomass of the microbial strains with 0.9% saline solution was added to the bigel at a temperature of 40 °C. Subsequently, the strains were mixed manually with the bigel for 30 s.

2.3.11. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Simulation

The simulated gastrointestinal digestion assay was conducted following a sequential oral, gastric, and intestinal model. For the oral phase, 5 mL of each bacterial culture was combined with 4 mL of sterile saline solution (pH 6.5) in sterile Falcon tubes. Subsequently, 125 μL of an alpha-amylase (Sigma-Aldrich, San Luis, MO, USA) solution (1.3 mg/mL CaCl2 1 mM) was added. The pH was adjusted to 6.5 using 1 M NaHCO3, and samples were incubated at 37 °C for 5 min under agitation at 100 rpm. The gastric phase was performed in the same tube by adding 9 mL of simulated gastric fluid consisting of pepsin (Sigma-Aldrich, San Luis, MO, USA) (3 mg/mL, 0.85% NaCl). The pH was adjusted to 2.0 using 1 M HCl, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h with continuous shaking at 100 rpm.

For the intestinal phase, 9 mL of simulated intestinal fluid composed of pancreatin (1.9 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, San Luis, MO, USA) and bile salts (1.2%) (BioBasic, Markham, ON, Canada) was added. The pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 1 M NaHCO3, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for an additional 2 h at 100 rpm. After completion of each digestion stage, the survival assay was performed in triplicate, reporting log (CFU/mL) [42].

2.3.12. Statistical Analysis

The results of the comparison and selection experiments were statistically processed and analyzed using Minitab software (V.19) and GraphPad software (V.10.2.0). Analysis of variance (ANOVA), Tukey’s test and Student’s t-test were used for group comparisons. The level of statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Endogenous Fermentation

Cocoa fermentation is typically divided into two stages. In the first stage, the pulp is metabolized by microorganisms that produce organic acids and ethanol; in the second stage, these metabolites promote hydrolytic reactions within the cotyledon [12]. Ethanol production occurs under anaerobic, acidic, and carbohydrate-rich conditions and is an exothermic process that increases the temperature of the fermenting mass [13,16,43]. During this process, pH decreases while titratable acidity increases, exhibiting an inverse relationship [44].

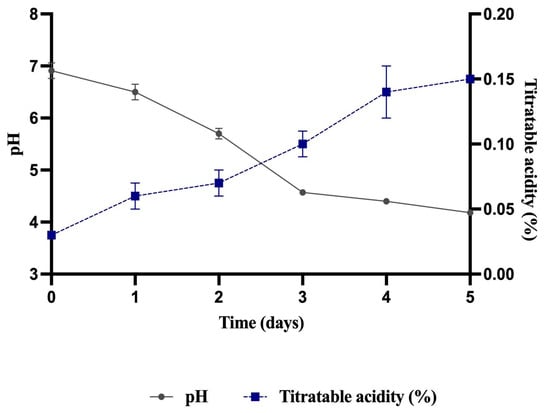

In the fermentation of pataxte beans, a significant reduction in pH was observed, decreasing from 6.91 at the beginning of the process to 4.18 at the end (Figure 1). Similarly, titratable acidity increased from 0.03% to 0.15% (Figure 1). According to Castro-Alayo et al. [45], such physicochemical changes are characteristic of a successful cocoa fermentation.

Figure 1.

pH and titratable acidity in fermented pataxte grains.

Pataxte bean fermentation in this study was carried out over a period of five days. Batista et al. [12] reported that criollo cocoa requires a shorter time to complete fermentation (approximately 156 h). Likewise, other authors have noted that cocoa beans typically require five to seven days of fermentation, and prolonging the process beyond this period may promote fungal growth and undesirable flavors [11]. Velazquez-Reyes et al. [29] emphasize that the duration of cocoa fermentation depends strongly on the origin and genotype of the beans. In the present study, fungal growth was observed beginning on day five, prompting termination of the fermentation process at that point.

3.2. Isolation of Lactic Acid Bacteria

Several researchers have successfully isolated and characterized LAB from endogenous fermentations with Theobroma cacao [15,46]. In this study, the initial isolation process yielded multiple bacteria (LAB) when cultured on MRS agar. Preliminary microscopic and biochemical characterization indicated the predominance of Gram-positive bacteria among the recovered isolates. However, the presence of additional Gram-negative bacteria suggested that the initial cultures represented mixed microbial populations rather than fully purified LAB strains (Table 1). This outcome is consistent with the known limitations of standard MRS agar selectivity when applied to complex spontaneous fermentation matrices, where competing flora (including certain Gram-negative bacteria) can initially proliferate alongside LAB [13,47]. As noted by Schwan & Wheals [13], the early stages of Theobroma fermentations are characterized by high microbial diversity, requiring rigorous subsequent purification steps to ensure the isolation of definitive LAB strains.

Table 1.

Macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of presumed LAB isolates on MRS agar.

Based on these observations, the culture medium was modified to improve LAB selectivity. Because Gram-negative bacteria do not fully metabolize mannitol, mannitol supplementation was used to suppress their growth [48,49]. Plates were prepared with MRS agar +1.2% mannitol. Five LAB strains were successfully isolated from pataxte, and their macro- and microscopic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of presumed LAB isolates on MRS agar with 1.2% mannitol.

The isolates presented exhibit morphological and biochemical characteristics consistent with the LAB group. Regarding microscopic morphology, while most isolates (S1.B, S2.A, S2.B, S5.A) displayed a bacillar shape, strain S6.B presented a coccoid morphology. Both shapes are characteristic of LAB; the family Lactobacillaceae includes both rod-shaped (e.g., Lactobacillus) and spherical-shaped (e.g., Pediococcus and Leuconostoc) bacteria [32]. Macroscopically, the colonies were predominantly white/transparent, with circular shapes and diameters ranging from small to large, which is typical of Lactobacillaceae proliferation on agar MRS.

Furthermore, all isolates tested negative for the catalase enzyme. This is the primary diagnostic feature for LAB, as they are typically aerotolerant anaerobes that lack heme-containing proteins like catalase, using alternative mechanisms such as peroxidases to manage oxidative stress [50]. The combination of Gram-positive staining, non-spore-forming bacillar or coccoid morphology, and a negative catalase reaction confirms that these isolates belong to the LAB group, as reported in similar fermented grain studies [13].

3.3. Antagonistic Activity

Probiotic microorganisms are expected to exhibit antimicrobial effects, particularly against pathogens relevant to the gastrointestinal tract [51]. Numerous studies have demonstrated the antimicrobial capacity of various LAB strains [52,53,54]. In the present work, S1.B produced an inhibition zone of 12.00 mm against S. Enteritidis , which, according to Abdel-Daim et al. [55], corresponds to moderate inhibition. Additionally, S1.B showed inhibition zones of 8.03 mm against E.coli, and 7.33 mm against S. aureus. Strain S2.A exhibited antimicrobial activity of 10.57 mm against S. Enteritidis, also classified as moderate inhibition [55], and 7.33 mm against E. coli. These findings are consistent with Piedra et al. [56], who reported antimicrobial effects of Lactobacillus pentosus against Salmonella. Such inhibitory activity has been attributed to bacteriocin-like proteins produced by certain lactobacilli [57], as well as to the generation of organic acids (primarily lactic and acetic acids), which lower environmental pH and inhibit pathogen growth [57,58,59]. The antagonistic activity results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Antagonistic activity against pathogenic strains by the disk diffusion method.

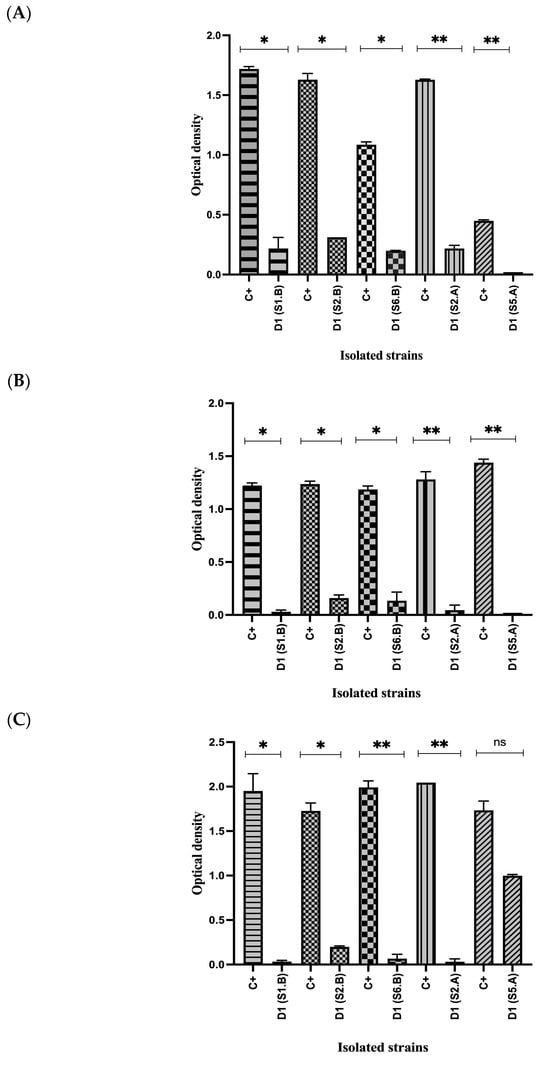

In addition to the disk diffusion assay, antimicrobial activity of cell-free supernatants was evaluated. For E.coli, the positive control (E. coli + MH) showed a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) compared with dilution 1 (D1) obtained from the supernatants of the isolated strains (Figure 2A). A similar pattern was observed for S. Enteritidis , where positive control differed significantly (p < 0.05) from D1 for all isolates (Figure 2B). For S. aureus, significant differences (p < 0.05) were also detected between the positive control and D1, except for strain S5.A, which did not differ statistically from the control (p > 0.05) (Figure 2C). These results collectively demonstrate the antimicrobial potential of the isolated strains.

Figure 2.

Antimicrobial activity of the LAB supernatant against pathogenic bacteria using the microplate technique. (A) Antimicrobial activity of the LAB supernatant against E. coli using the microplate technique. (B) Antimicrobial activity of the LAB supernatant against S. Enteritidis using the microplate technique. (C) Antimicrobial activity of the LAB supernatant against S. aureus using the microplate technique. Student’s t-test; (* = p ≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.01, ns = not significant). C+ (positive control), D1 (dilution 1).

Additionally, Table 4 presents the minimum inhibitory concentration required to inhibit 90% of the pathogenic bacteria (MIC90) using the cell-free supernatants of the isolated strains. Strain S5.A showed the greatest inhibitory capacity against E.coli, requiring only 7.41% of the supernatant, and also inhibited S. Enteritidis with a 32.56%. However, this strain displayed the lowest inhibitory effect against S. aureus, with a MIC90 of 99.42% In contrast, strain S2.B exhibited the highest MIC90 values across all pathogens, indicating the weakest antimicrobial performance among the isolates. The results align with findings from Kim-Kang et al. [59], who demonstrated that the cell-free supernatant of a LAB strain can inhibit Salmonella, E. coli, S. aureus, and other foodborne pathogens. The antimicrobial effects are commonly attributed to the secretion of organic acids, particularly lactic acid, as well as bacteriocins and antimicrobial peptides that exert inhibitory activity against pathogenic bacteria. Based on the MIC90 values observed, two of the five isolated strains (S2.B and S6.B) were excluded from further probiotic evaluation due to their comparatively low antimicrobial potential.

Table 4.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC90) of selected LAB cell-free supernatants against pathogenic bacteria.

3.4. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion

Probiotic strains must survive passage through the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), tolerating acidic gastric conditions and bile salts in order to exert their beneficial effects [56]. The in vitro digestion assay in this study comprised three sequential phases: oral, gastric, and intestinal. According to the results shown in Table 5, strain S1.B exhibited TNTC (Too numerous to count) counts during the oral phase, and no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between the gastric and intestinal phases, reaching 3.61 ± 0.00 log (CFU/mL) after intestinal exposure. Similarly, strain S2.A did not show significant differences (p > 0.05) between the gastric and intestinal phases, maintaining a viability of 0.34 ± 0.49 log(CFU/mL). These results indicate that both S1.B and S2.A were able to survive exposure to acidic pH and bile salts. Previous studies have reported that LAB isolated from Theobroma cacao exhibit substantial viability under simulated gastric and intestinal conditions [60]. The ability of a microorganism to withstand acidic environments depends on factors such as intracellular hydronium ion accumulation and metabolic regulation [60,61].

Table 5.

Survival of selected LAB strains during in vitro gastrointestinal simulation.

In contrast, strain S5.A did not survive the gastric phase, nor was growth detected during the subsequent intestinal stage, suggesting greater sensitivity to low pH and bile salts. The literature emphasizes that acid and bile tolerance varies widely among LAB species and even among strains of the same species [61]. Since resistance to low pH (2.0–3.0) and bile salts is critical criterion for selecting potential probiotics [56], encapsulation strategies (such as bigels) have been proposed to enhance bacterial survival during food incorporation and gastrointestinal transit [24]. A comparison of encapsulated and non-encapsulated strains revealed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) in the gastric and intestinal phases for S2.A and S1.B (Table 5). While non-encapsulated S5.A showed no tolerance to bile salts or acidic conditions, its encapsulated counterpart demonstrated detectable survival in both phases, with significant differences (p < 0.05) between encapsulated and non-encapsulated treatments. This finding aligns with the results of Bollom et al. [24], who reported that bigels effectively protected Bifidobacterium lactis and Lactobacillus acidophilus during an in vitro digestion.

Similarly, Zhuang et al. [62] developed a soy lecithin-stearic acid bigel system in combination with a hydrogel phase and incorporated Lactobacillus acidophillus and Bifdobacterium lactis into yogurt. The survival of both probiotics within the bigel matrix remained significantly higher than that of non-encapsulated cells over five weeks, demonstrating the ability of bigels to enhance probiotic stability. Bigels exert a protective effect by forming a semi-solid physical barrier that shields bacteria from harsh gastric conditions. Additionally, their oleogel fraction can emulsify or solubilize bile salts, which reduces direct bacterial damage and helps preserve viability [24]. Collectively, these results highlight the potential of bigels as effective delivery systems that enable encapsulated probiotics to reach the intestine and exert their beneficial effects.

3.5. Identification of Isolated Bacteria by MALDI-TOF MS

Strain S1.B, which exhibited the highest tolerance to low pH and bile salts, as well as strong antimicrobial activity, was selected for identification by MALDI-TOF MS. The analysis revealed a spectral profile consistent with Lactobacillus pentosus/plantarum/paraplantarum group. MALDI-TOF MS is widely used for bacterial identification due to its speed, reproducibility, and ability to differentiate closely related species based on protein mass spectra [36]. The technique generates ionized peptides from whole cells, which are then separated according to their mass-to-charge ratio to produce a characteristic fingerprint for each microorganism [37].

However, MALDI-TOF MS identification can be limited by the completeness of commercial reference database, particularly for less-studied species or strains isolated from unconventional substrates. This limitation likely explains why strain S1.B was matched to a species group rather than a single definitive species, requiring further confirmation through molecular identification methods [63].

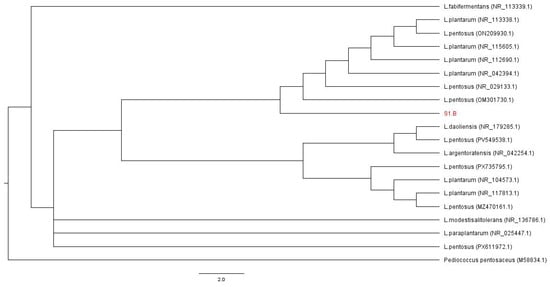

3.6. Molecular Identification of the Potential Probiotic Isolated

To complement the preliminary identification obtained through MALDI-TOF MS, molecular analysis of the 16S rRNA gene was performed. Forward and reverse sequences were assembled into a high-quality consensus sequence of 1542 bp, which was used for taxonomic analysis. BLASTn alignment against the curated NCBI database “16S ribosomal RNA (Bacteria and Archaea type strains)” revealed that strain S1.B corresponds to Lactiplantibacillus pentosus, exhibiting 99% similarity with the closest entries in the NCBI GenBank database (accession number NR_029133.1). The assembled consensus 16S rRNA gene sequence generated in this study is provided in Supplementary Material File S1.

Figure 3 shows the phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Although some internal nodes showed low bootstrap support, this behavior is commonly reported when using the 16S rRNA gene to resolve phylogenetic relationships among closely related LAB. Nevertheless, strain S1.B consistently clustered within the Lactiplantibacillus pentosus clade, supporting its taxonomic assignment.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of strain S1.B based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using 16S rRNA gene sequences of strain S1.B and closely related reference strains retrieved from NCBI GenBank database. Sequences were aligned using Clustal W, and tree was inferred using the Likelihood method. Branch support values were estimated by bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates and are shown at the nodes. The tree was rooted using Pediococcus pentosaceus as the outgroup. Scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site.

According to Schwan & Wheals. [13], the most frequently isolated LAB during cocoa fermentations include Lactiplantibacilllus plantarum, Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Lactococcus lactis. Numerous studies have also documented the isolation and characterization of LAB from spontaneous fermentations of Theobroma cacao across different geographic regions, with Lactiplantibacilllus plantarum being one of the most commonly reported species [15,17,46]. Although L. pentosus has occasionally been isolated from cocoa (Theobroma cacao) fermentations [64], its presence in pataxte (Theobroma bicolor) has not been previously documented. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first report of L. pentosus isolated from spontaneous fermentation of Theobroma bicolor, highlighting the unexplored microbial diversity associated with this species and its potential biotechnological relevance.

4. Conclusions

In this study, five LAB were isolated from the endogenous fermentation of Theobroma bicolor (pataxte) grains. These strains were subjected to different in vitro assays, including antimicrobial activity (Kirby-Bauer and MIC tests) and simulated gastrointestinal digestion. The MIC results demonstrated inhibitory activity against E. coli, S. Enteritidis, and S. aureus using the cell-free supernatants of the isolates. In the Kirby-Bauer assay, strain S1.B and S2.A showed intermediate activity against S. Enteritidis.

Among the five isolates, only one strain, S1.B, survived exposure to acid pH (2.0) and bile salts during the in vitro gastrointestinal simulation, with a survival of 3.61 ± 0.00 Log (CFU/mL). This strain was identified as Lactiplantibacillus pentosus. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first report of a LAB strain isolated and identified from endogenous fermentation of T. bicolor, demonstrating notable potential as probiotic candidate. Finally, the bigels used in this study proved effective as probiotic delivery systems, enhancing bacterial protection under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. These results highlight bigels as an innovative and versatile technology with promising applications in food industry.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation12010041/s1, File S1. Genome sequence of Lactiplantibacillus pentosus.

Author Contributions

M.F.R.-O.: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Conceptualization. B.P.-A.: Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review and editing. M.d.L.M.-J.: Methodology, Supervision, Validation. L.C.-M.: Methodology, Supervision, Resources. G.A.C.-U.: Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the UPAEP and CONAHCYT for supporting Maria Fernanda Rosas-Ordaz through the funding of her PhD studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Díaz, R.O.; Hernández, M.S. Theobromas de la Amazonia Colombiana: Una alternativa saludable. Inf. Tecnol. 2020, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Marroquín, L.A.; Reyes-Reyes, A.L.; Avendaño-Arrazate, C.H.; Hernández-Goméz, E. Pataxte (Theobroma bicolor Humb. Bonpl.): Especie Subutilizada en México. Agro Product. 2016, 9, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tinajero-Carrizales, C.; González-Pérez, A.L.; Rodríguez-Castillejos, G.C.; Castañón-Nájera, G.; Ruíz Salazar, R. Comparación próximal en Cacao (Theobroma cacao) y Pataxte (T. bicolor) de Tabasco y Chiapas, México. Polibotánica 2021, 52, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigrero, B.; Sanclemente, B. Sustitución de Theobroma cacao Por Theobroma bicolor y su Aplicación en Repostería. Master’s Thesis, University of Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce-Sánchez, J.; Zurita-Benavides, M.G.; Peñuela, M.C. Reproductive ecology of white cacao (Theobroma bicolor Humb. Bonpl.) in Ecuador, western Amazonia: Floral visitors and the impact of fungus and mistletoe on fruit production. Braz. J. Bot. 2021, 44, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlloch-Tinoco, M.; Ramírez, J.M.N.; García, P.; Gentile, P.; Girón-Hernández, J. Theobroma genus: Exploring the therapeutic potential of T. grandiflorum and T. bicolor in biomedicine. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Chang, J.F.; Vásquez-Cortez, L.H.; Zapata-Quevedo, K.L.; Rodríguez-Cevallos, S.L. Caracterización morfológica, fisicoquímica y microbiológica del cacao Macambo (Theobroma bicolor Humb. Bonpl.) en Ecuador. Rev. Agrotecnológica Amaz. 2024, 4, e657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chen, C.; Ni, D.; Yang, Y.; Tian, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Wang, L. Effects of Fermentation on Bioactivity and the Composition of Polyphenols Contained in Polyphenol-Rich Foods: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño, A.C.; Pérez, D.M.; Montalvo, I.G.; Medina, M.A.S.; Bautista, E.H. Evaluación del Proceso Fermentativo Tradicional del Theobroma bicolor en Teotitlán del Valle, Oaxaca, México. Cienc. Lat. Rev. Cient. Multidiscip. 2025, 9, 7899–7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Weckx, S. The cocoa bean fermentation process: From ecosystem analysis to starter culture development. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán-Alvarez, R.; Márquez-Ramos, J.G. Fermentation of Cocoa Beans. In Fermentation—Processes, Benefits and Risks; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, N.N.; Ramos, C.L.; Dias, D.R.; Pinheiro, A.C.M.; Schwan, R.F. The impact of yeast starter cultures on the microbial communities and volatile compounds in cocoa fermentation and the resulting sensory attributes of chocolate. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 53, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwan, R.F.; Wheals, A.E. The Microbiology of Cocoa Fermentation and its Role in Chocolate Quality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, N.; Yilmaz, B.; Sharma, H.; Kumar, M.; Pateiro, M.; Ozogul, F.; Lorenzo, J.M. A novel approach to Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: From probiotic properties to the omics insights. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 268, 127289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyirifo, D.S.; Wamalwa, M.; Otwe, E.P.; Galyuon, I.; Runo, S.; Takrama, J.; Ngeranwa, J. Metagenomics analysis of cocoa bean fermentation microbiome identifying species diversity and putative functional capabilities. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, L.J.R.; Almeida, M.H.; Nout, M.J.R.; Zwietering, M.H. Theobroma cacao L., “The Food of the Gods”: Quality Determinants of Commercial Cocoa Beans, with Particular Reference to the Impact of Fermentation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2011, 51, 731–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, H.G.; Ouattara, H.; Yao, W.; Williams, N.; Reverchon, S.; Niamke, S.; Elias, R.; Edwards, D. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) strains are actively involved in the occurrence of aroma compounds during cocoa fermentation. Microbiol. Nat. 2019, 1, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Lv, M.; Shao, Z.; Hungwe, M.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y.; Geng, W. Metabolism Characteristics of Lactic Acid Bacteria and the Expanding Applications in Food Industry. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 612285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, A.; Bonet, R. Probióticos. Farm. Prof. 2017, 31, 13–16. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7718744 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Tormo Carnicé, R. Probióticos. Concepto y mecanismos de acción. An. Pediatría 2006, 4, 30–41. Available online: https://www.analesdepediatria.org/es-probioticos-concepto-mecanismos-accion-articulo-13092364 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Tripathi, M.K.; Giri, S.K. Probiotic functional foods: Survival of probiotics during processing and storage. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 9, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.T.; Tzortzis, G.; Charalampopoulos, D.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Microencapsulation of probiotics for gastrointestinal delivery. J. Control. Release 2012, 162, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, B.; Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M. Bigels as novel carriers of bioactive compounds: Applications and research trends. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollom, M.A. Development and Characterization of a Novel, Edible Bigel System with the Potential to Protect Probiotics During In Vitro Digestion. Master’s Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, 2020; pp. 1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Qureshi, D.; Nayak, S.K.; Pal, K. Bigels. In Polymeric Gels; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2018; pp. 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, F.; Yuan, S.; Dai, W.; Yin, L.; Dai, Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Guo, Q.; Zhu, Q. Development of novel Lactobacillus plantarum-encapsulated Bigel based on soy lecithin-beeswax oleogel and flaxseed gum hydrogel for enhanced survival during storage and gastrointestinal digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 163, 111052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, P.D.; Cardoso-Ugarte, G.A.; Pérez-Armendáriz, B. Producción de bebida fermentada simbiótica de pataxte (Theobroma bicolor) adicionada con bacterias ácido lácticas. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. Soc. 2024, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, M.A.; Sánchez-Chino, X.M.; García-Bautista, M.; González-Díaz, A.Á.; Ruíz-Montoya, L.; Castellanos-Morales, G. Phenotypic and genetic variation in pataxte (Theobroma bicolor Humb. Bonpl.) from cacao growing regions from southeastern Mexico. Bot. Sci. 2025, 103, 858–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Reyes, D.; Gschaedler, A.; Kirchmayr, M.; Avendaño-Arrazate, C.; Rodríguez-Campos, J.; Calva-Estrada, S.; Lugo-Cervantes, E. Cocoa bean turning as a method for redirecting the aroma compound profile in artisanal cocoa fermentation. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 17th ed.; Horwitz, W., Ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Man, J.C.; Rogosa, M.; Sharpe, M.E. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1960, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzapfel, W.H.; Wood, B.J. (Eds.) Lactic Acid Bacteria; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Sapra, A. Gram Staining; National Library of Medicine; StatPearls Publishing: Orlando, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562156/ (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Halima, K.; Anokhe, A.; Kalia, V. Catalase Test: A Biochemical Protocol for Bacterial Identification. AgriCos 2022, 3, 53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, M.L. Pruebas de sensibilidad antimicrobiana: Métodología de laboratorio. Rev. Médica Hosp. Nac. Niños Dr. Carlos Sáenz Herrera 1999, 34, 33–41. Available online: https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1017-85461999000100010 (accessed on 7 March 2024).

- Singhal, N.; Kumar, M.; Kanaujia, P.K.; Virdi, J.S. MALDI-TOF Mass spectrometry: An Emerging Technology for Microbial Identification and Diagnosis. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Yousefi, L.; Pakdel, F.; Ghotaslou, R.; Rezaee, M.A.; Khodadadi, E.; Oskouei, M.A.; Soroush Barhaghi, M.H.; Kafil, H.S. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectroscopy Applications in Clinical Microbiology. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 2021, 9928238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woese, C.R.; Kandler, O.; Wheelis, M.L. Towards a natural system of organisms: Proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 4576–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarridge, J.E. Impact of 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis for Identification of Bacteria on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 17, 840–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanger, F.; Nicklen, S.; Coulson, A.R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5463–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ortiz, V.M.; Trujillo-López, M.A.; El-Kassis, E.G.; Bautista-Rodríguez, E.; Kirchmayr, M.R.; Hernández-Carranza, P.; Pérez-Armendáriz, B. Bacillus mojavensis isolated from aguamiel and its potential as a probiotic bacterium. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2024, 67, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.T.T.; Fleet, G.H.; Zhao, J. Unravelling the contribution of lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria to cocoa fermentation using inoculated organisms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 279, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortez, D.; Quispe-Sanchez, L.; Mestanza, M.; Oliva-Cruz, M.; Yoplac, I.; Torres, C.; Chavez, S.G. Changes in bioactive compounds during fermentation of cocoa (Theobroma cacao) harvested in Amazonas-Peru. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Alayo, E.M.; Idrogo-Vásquez, G.; Siche, R.; Cardenas-Toro, F.P. Formation of aromatic compounds precursors during fermentation of Criollo and Forastero cocoa. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visintin, S.; Alessandria, V.; Valente, A.; Dolci, P.; Cocolin, L. Molecular identification and physiological characterization of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria isolated from heap and box cocoa bean fermentations in West Africa. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 216, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ben Omar, N.; Ampe, F. Microbial Community Dynamics during Production of the Mexican Fermented Maize Dough Pozol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3664–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamei, S.; Hu, Y.O.O.; Olofsson, T.C.; Andersson, A.F.; Forsgren, E.; Vásquez, A. Improvement of identification methods for honeybee specific Lactic Acid Bacteria; future approaches. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, D.; Poddar, S.; Rai, R.P.; Purwati, E.; Dewi, N.P.; Pratama, Y.E. Molecular Identification of Lactic Acid Bacteria an Approach to Sustainable Food Security. J. Public Health Res. 2022, 10, jphr.2021.2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wright, A.; Axelsson, L. Lactic Acid Bacteria: Microbiological and Functional Aspects; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; p. 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Lee, H.-J. Antimicrobial Activity of Probiotic Bacteria Isolated from Plants: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jo, J.; Wan, J.; Seo, H.; Han, S.-W.; Shin, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-H. In Vitro Evaluation of Probiotic Properties and Anti-Pathogenic Effects of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Strains as Potential Probiotics. Foods 2024, 13, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões, L.; Fernandes, N.; de Souza, A.; dos Santos, L.; Magnani, M.; Abrunhosa, L.; Teixeira, J.; Schwan, R.F.; Dias, D.R. Probiotic and Antifungal Attributes of Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolates from Naturally Fermented Brazilian Table Olives. Fermentation 2022, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelidkazeran, E.; Bouri Yildiz, M.; Sahin, F. In Vitro Assessment of Biological and Functional Properties of Potential Probiotic Strains Isolated from Commercial and Dairy Sources. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, A.; Hassouna, N.; Hafez, M.; Ashor, M.S.A.; Aboulwafa, M.M. Antagonistic Activity of Lactobacillus Isolates against Salmonella typhi In Vitro. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 680605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piedra, V.; Usaga, J.; Redondo-Solano, M.; Uribe-Lorío, L.; Valenzuela-Martínez, C.; Barboza, N. Inhibiting potential of selected lactic acid bacteria isolated from Costa Rican agro-industrial waste against Salmonella sp. in yogurt. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2024, 14, 12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Bangar, S.P.; Echegaray, N.; Suri, S.; Tomasevic, I.; Manuel Lorenzo, J.; Melekoglu, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Ozogul, F. The Impacts of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on the Functional Properties of Fermented Foods: A Review of Current Knowledge. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddik, H.A.; Bendali, F.; Gancel, F.; Fliss, I.; Spano, G.; Drider, D. Lactobacillus plantarum and Its Probiotic and Food Potentialities. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 9, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kang, S.I.; Shin, D.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Lee, C.W.; Yang, Y.; Son, Y.K.; Yang, H.-S.; Lee, B.-H.; An, H.-J.; et al. Potential of Cell-Free Supernatant from Lactobacillus plantarum NIBR97, Including Novel Bacteriocins, as a Natural Alternative to Chemical Disinfectants. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandha, M.C.; Shukla, R.M. Exploration of probiotic attributes in lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented Theobroma cacao L. fruit using in vitro techniques. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1274636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Ramírez, M.C.; Jaimez-Ordaz, J.; Escorza-Iglesias, V.A.; Rodríguez-Serrano, G.M.; Contreras-López, E.; Ramírez-Godínez, J.; Castañeda-Ovando, A.; Morales-Estrada, A.I.; Felix-Reyes, N.; González-Olivares, L.G. Lactobacillus pentosus ABHEAU-05: An in vitro digestion resistant lactic acid bacterium isolated from a traditional fermented Mexican beverage. Rev. Argent. De Microbiol. 2020, 52, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, X.; Clark, S.; Acevedo, N. Bigels—Oleocolloid matrices—As probiotic protective systems in yogurt. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 4892–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koster, C.G.; Brul, S. MALDI-TOF MS identification and tracking of food spoilers and food-borne pathogens. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 10, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrurrozi; Rahayu, E.P.; Nugroho, I.B.; Lisdiyanti, P. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) isolated from fermented cocoa beans prevent the growth of model food-contaminating bacteria. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2099, 020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.