Abstract

In this study, the characterization of some bioactive content of exopolysaccharide (EPS) extracted from Pediococcus ethanolidurans isolated with Smilax excelsa L. from conventionally produced pickles were investigated. Background: Although this study is the main study involving the characterization of EPS obtained from Pediococcus ethanolidurans, it is important because it has determined a natural polysaccharide that can be used in different fields in the industry. According to the obtained results, sugar analysis by GC-MS revealed that EPS consisted of glucose (7.59%), mannose (41.96%), fructose (16.98%), arabinose (3.15%) and rhamnose (30.30%). From the thermal behavior determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), it was concluded that it should not be heated close to 250 °C. At the same time, according to the thermogram obtained as a result of X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, it was found to have a crystalline structure. EPS, which reached 73.844% efficiency, showed antibacterial activity against Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, while 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) scavenging activity was detected at 0.24 mM. It also has remarkable results, seen in cytotoxicity analysis against healthy HT-29 cells, demonstrating that it has proliferative activity as high as %125 In short, Pediococcus ethanolidurans was found to be a novel EPS producer with impressive properties.

1. Introduction

Smilax, commonly called Sarsaparilla, is the largest genus of the Smilacaceae family. There are 350 subspecies belonging to the genus Smilax. Plants of this genus are spiny, perennial and tall. They grow in temperate, tropical and subtropical regions around the world. About 76 of these species originate from China, 29 from America and 24 from India [1,2]. Various species of the genus Smilax have been reported to have many pharmacological activities [1,3,4,5,6], including anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties [7]. There are also sources that suggest that it is used to treat acute bacillary dysentery, syphilis, eczema, cystitis, dermatitis, acute and chronic nephritis, mercury–silver poisoning, stomach pain and swelling, and breast cancer [8].

Among these species, Smilax excelsa L., locally known in Turkey as “kırçan”, is widely consumed in the Black Sea region, particularly in the form of traditionally fermented pickles. There are studies in the literature on leaf, stem and flower parts of Smilax excelsa L. [1,2,3,5,9]. However, no research on the traditional pickle form of Smilax excelsa L. has been found. However, knowledge of the diverse and rich microflora of traditional pickles will contribute to the literature and lead to divergent studies. It is also very important to know the different properties of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) isolated from traditional pickles. Furthermore, biomolecules such as exopolysaccharides produced by lactic acid bacteria have been the focus of attention in recent years.

Exopolysaccharides, which are biodegradable and biocompatible and come from the group of biopolymers, are generally compatible with the structure and composition of all living things. It is also known that biopolymers can be produced from microorganisms as well as from plants and animals. Recently, the natural potential benefits of polysaccharides produced from bioresources have attracted attention. This unique affinity for biopolysaccharides is exploited as a biosurfactant, bioemulsifier and exopolysaccharide in biotechnological, pharmacological, industrial and medical applications [10,11,12].

Exopolysaccharides (EPS) are the most notable biopolymers of recent times [13]. EPS are grouped in two categories, such as homopolysaccharides (HoPS) and heteropolysaccharides (HePS), according to the type of monosaccharide they contain. HoPS consists of a single type of monosaccharide, while HePS consists of a combination of different monosaccharides, although it has been reported that it can sometimes contain amino sugars or glycerol and phosphate [14]. Some studies have shown that LABs can genetically synthesize more than one EPS [15,16]. Recent studies have proven that some LAB strains can produce HoPS and HePS. However, studies on EPS production and characterization of EPS produced by Pediococcus, which belong to the lactic acid bacteria group, are limited. To date, EPS are known to be produced by strains of the genus Pediococcus, strains isolated from wine and beer [17], and Lactobacillus and Pediococcus species in cider [15,16].

This study reports the isolation and comprehensive characterization of exopolysaccharides (EPS) produced by Pediococcus ethanolidurans isolated from traditionally fermented Smilax excelsa L. pickles. To the best of our knowledge, previous studies on P. ethanolidurans have primarily focused on genetic-level investigations of EPS biosynthesis [18], whereas detailed physicochemical and bioactive characterization of its EPS has not yet been reported. Therefore, the present work emphasizes the structural features and bioactive properties of EPS derived from P. ethanolidurans. Moreover, this study provides a valuable contribution to the understanding of both the microbial ecology of Smilax excelsa L. pickles and the functional potential of EPS produced by P. ethanolidurans.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain and Culture Condition

P. ethanolidurans was isolated from a traditionally fermented Smilax excelsa L. pickle and preserved at −80 °C. To ensure culture activation and viability, the frozen stock was sub-cultured three consecutive times in de Man–Rogosa–Sharpe (MRS) broth (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 37 °C for 18 h. Phenotypically distinct colonies were preliminarily characterized by Gram staining and catalase testing. Subsequently, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) was employed for taxonomic identification. Based on the MALDI-TOF score values, the isolate was confirmed as P. ethanolidurans and maintained at −80 °C in MRS broth supplemented with 15% (v/v) glycerol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for subsequent exopolysaccharide (EPS) production studies.

2.2. Extraction and Purification of EPS

Exopolysaccharide (EPS) production by P. ethanolidurans was carried out under standard growth conditions. The activated culture was anaerobically incubated in MRS broth at 37 °C for 24 h with shaking. After the incubation, the medium was heated in a boiling water bath for 15 min to inactivate the enzyme and centrifuged at 10,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C to remove the cells. The 80% (w/v) TCA (trichloroacetic acid; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to the culture, and the final concentration was adjusted to 4% (w/v), which was stirred for 12 h before incubation at 10,000× g at 4 °C and centrifuged 15 min. The clarified supernatant was subsequently mixed with two volumes of chilled absolute ethanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and kept at 4 °C for 12 h to precipitate the crude EPS. The EPS precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 10,000× g for 15 min at 4 °C, washed twice with cold ethanol, and dried under vacuum to obtain the crude EPS fraction. The carbohydrate content of the crude EPS was quantified by the phenol sulfuric acid assay using D-glucose (Sigma–Aldrich, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) as the standard.

2.3. Characterization of EPS

2.3.1. XRD

The crystalline characteristics of the EPS were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD; Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) analysis. The dried EPS sample was mounted onto the specimen holder, and diffraction patterns were recorded using a Bragg–Brentano θ–2θ geometry. The diffractogram was obtained over an appropriate 2θ range to evaluate the crystalline or amorphous nature of the polymeric structure.

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis

The purified EPS sample (2 mg) was finely ground with spectroscopic-grade potassium bromide (KBr, 200 mg) and pressed into pellets under vacuum. The infrared spectrum was recorded using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (PG Instruments Limited, Earl Shilton, Leicestershire, UK) within the range of 4000–400 cm−1 to identify the functional groups and characteristic chemical bonds present in the EPS structure.

2.3.3. Thermodynamic Stability Analysis

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was used to determine the thermal properties of EPS. For this purpose, the weight loss curve of EPS versus temperature was determined by the DSC test performed with a heating induction of 10 °C/min between 20 and 600 °C by placing 5 mg of the purified EPS sample in Al2O3.

2.3.4. Monosaccharide Composition Analysis

The monosaccharide composition of the purified EPS was determined by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS; Agilent Technologies 7890A, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a DB-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm, film thickness 0.25 µm) and a flame ionization detector (FID). Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1.

For derivatization, the EPS sample (5 mg) was hydrolyzed with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) at 120 °C for 3 h. The hydrolysate was repeatedly co-evaporated with methanol (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) (five times) using a rotary evaporator to remove residual TFA and water. The dried sample was then reduced with sodium borohydride (30 mg NaBH4; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and acetylated with acetic anhydride.

The resulting alditol acetates were analyzed by GC-MS, and monosaccharide components were identified by comparing their retention times and mass spectra with those of authentic standards (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), including L-rhamnose, L-arabinose, D-galactose, D-glucose, D-xylose, D-mannose, D-fructose, and D-ribose.

2.3.5. Measurement of Cytotoxicity

The cytotoxic effect of the purified EPS on normal human fibroblast cells was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay [19]. Normal CCD-1079Sk cells (CRL-2097™, Manassas, VA, USA) were trypsinized and seeded into 96-well plates at an appropriate density, followed by treatment with various concentrations of EPS (15.625–500 μg mL−1). The cells were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the culture medium (DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was carefully removed, and MTT reagent (0.5 mg mL−1; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added to each well. The plates were further incubated for 3 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere to allow the formation of formazan crystals. The supernatant was then discarded, and the crystals were solubilized with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a micro-plate spectrophotometer (BioTek Synergy H1, BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability (%) was calculated relative to untreated controls, and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was determined by non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

2.3.6. Intrinsic Viscosity-Based Molecular Weight Determination

The molecular weight (Mw) of the purified EPS was determined indirectly based on intrinsic viscosity (η) measurements using a rheological approach [12]. Viscosity measurements were performed at 25 °C over a shear rate range of 1–100 s−1 for EPS solutions prepared at different concentrations. The flow behavior of the EPS solutions was evaluated using the Herschel–Bulkley model to obtain intrinsic viscosity values.

The molecular weight was calculated using the Mark–Houwink equation, which correlates intrinsic viscosity with polymer molecular weight through polymer-specific constants, as previously reported for LAB-derived EPS [20,21].

where τ: shear stress (Pa), το: yield stress (Pa), K: polymer-specific constant values, γ: shear rate (s−1), η: internal viscosity, Mw: weight-average molecular weight, a: Mark–Houwink exponent and n: flow index.

τ = το + K·γn

η = K·Mwa

2.4. Antimicrobial Activity

2.4.1. Zone of Inhibition (ZOI) Assay

The antimicrobial activity of EPS was determined by the disk diffusion method against six bacterial strains (Escherichia coli ATCC 11230, Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 7644 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 2592). For this purpose, the tested bacteria were grown overnight at 37 °C in Nutrient Broth (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and then applied to the surface of the sterile Nutrient Agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with a sterile swab and allowed to dry for 10 min. Then, EPS samples were prepared in four different concentrations (1, 10, 20 and 50 μg mL −1) and were impregnated on the disk (Φ = 4 mm) and placed on the agar. Petri dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the zoned areas around the filter disk were quantified as a specific inhibition zone for each bacterium.

2.4.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) Assay

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) of the purified EPS were determined using the broth microdilution method according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [22]. Bacterial strains exhibiting inhibitory zones in the antimicrobial assay were selected for MIC and MBC evaluation. Selected bacteria strains were activated overnight in Nutrient Broth at 37 °C prior to testing. Serial two-fold dilutions of EPS were prepared in sterile Nutrient Broth to obtain final concentrations of 0, 50, 125, 250, 500, 1000, 2500, 5000 and 10,000 μg mL−1. The bacterial inoculum was standardized and added to each well at a 1:100 ratio. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h with shaking at 100 rpm, and bacterial growth was monitored by measuring optical density at 600 nm.

For MBC determination, aliquots from wells showing no visible growth were spread onto Nutrient Agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) plates and incubated under similar conditions. The lowest EPS concentration that resulted in no bacterial growth on agar plates was recorded as the MBC. All assays were performed in triplicate. Penicillin (10 μg mL−1) served as the positive control. The MBC/MIC ratio was calculated to differentiate between bactericidal (MBC/MIC ≤ 4) and bacteriostatic (MBC/MIC > 4) activity.

2.5. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

The Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) test is a method that determines a compound’s ability to scavenge free radicals with Trolox ((S)-(2)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-chroman-2-carboxylic acid; Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) [23]. For this, 10 mL of the different concentrations of purified EPS (50, 25 and 10 μg mL−1) were mixed with 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS; Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) radical cation solution and stored for 5 min, and the amount of ABTS remaining at the end of the time was determined by reading at 734 nm. The results are expressed as Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC).

2.6. Data Analysis

In the current study, statistical differences were determined using SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Results were performed using Duncan’s multiple comparison test with a 95% confidence interval (p < 0.05).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Purification of the EPS

The chemical composition of EPS produced in the study is given in Table 1. The type of bacteria produced affects the polymer dry solids and total sugars of EPS. The total sugar of the EPS produced by P. ethanolidurans with high EPS yield was determined to be 73.844%. No study on the sugar content of EPS obtained from Pediococcus species was found in the literature. However, the sugar ratios of different EPS products from different LAB can be different [24]. This may be due to the difference in the medium used or the incubation conditions [25].

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of EPS from P. ethanolidurans.

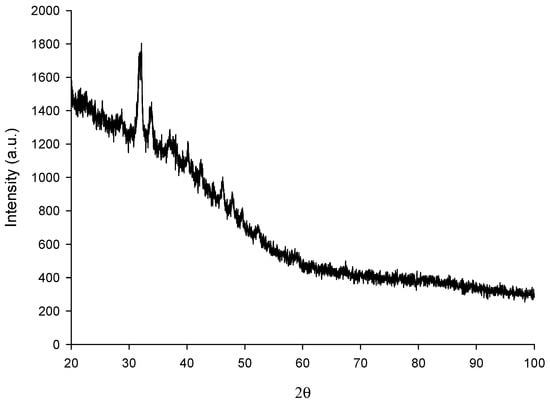

3.2. XRD

As can be seen in Figure 1, the XRD analysis results show that the spectrum of the two thetas (2θ) is broad with a sharp peak. The broad peaks represent the amorphous structure of EPS while the sharp peaks represent the crystalline structure. In the XRD structure of EPS obtained from P. ethanolidurans, elongated peaks are observed in the two theta regions 28.67°, 34.75° and 47.4° at densities of 1558.5, 1786.2 and 1000, respectively. The XRD pattern shows the former EPS where a crystalline structure took it out. These results have not been obtained with EPS from other protective Pedioccocus strains of similar structure. The strength of our study is that it is the first study in which the first XRD structure of EPS was obtained with P. ethanolidurans measurement. The crystal structure of polysaccharides in previous operations recently performed tends to influence their speed, swelling, viscosity and size properties. Overall, our result is that EPS with (1 → 4)-linked α-D-glucose units as branch points has a crystalline structure, and this property may affect its ultimate techno-functionality.

Figure 1.

XRD spectrum of the EPS.

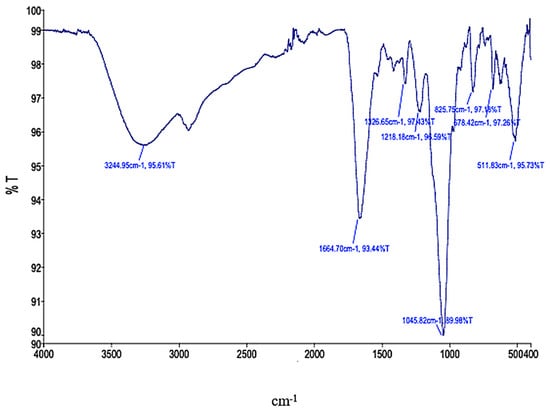

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis

Possible changes in the functional groups of EPS from P. ethanolidurans were tested in a complex spectrum pattern from 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1 by FTIR analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

FTIR analysis of EPS.

As can be seen in Figure 2, the results showed that a broad strain peak at 3244.95 cm−1 was due to the bending and stretching of O-H in the hydroxyl group [26]. The small peaks in the 2924.16–2852.88 cm−1 (C-H) region indicated low lipid content in EPS samples from P. ethanolidurans [27]. Strong amide group peaks appeared at 1664.7 cm−1, each [28] indicating that the protein is one of the main components of EPS [26,28]. The small peaks at 1326.65 cm−1 in the EPS of P. ethanolidurans represented the methyl group and carboxylic groups, and the latter group could be assigned to uronic acid [29]. An intense absorbance peak between 1218.18 and 1045.82 cm−1 has been assigned to the sulfate groups (S=O and C-O-S bonds) in EPS [29], while large peaks in the area of 1094.40 and 1032.43 cm−1 indicated the existence of carbohydrates in EPS [12].

It can be said that the monosaccharide content of the EPS of P. ethanolidurans and the FTIR spectra are mutually supportive [30]. For example, EPS from P. ethanolidurans had a higher protein but lower carbohydrate contents which was also observed in the protein bands of the FTIR spectra. The 1000–1200 cm−1 region showed an intense band characteristic of the C-O-C and C-O stretches of the alcohol groups in carbohydrates [31]. The band at 1030 cm−1 is characteristic of polysaccharide compounds [30]. The substance is a polysaccharide [27,30]. The characteristic absorption signal at 825.75 cm−1 indicated the presence of α-anomeric configured D-mannopyranose units [24,32]. The band at 678.42 and 511.83 cm cm−1 represents C-S linkage and halogen compound (C-Br) [30].

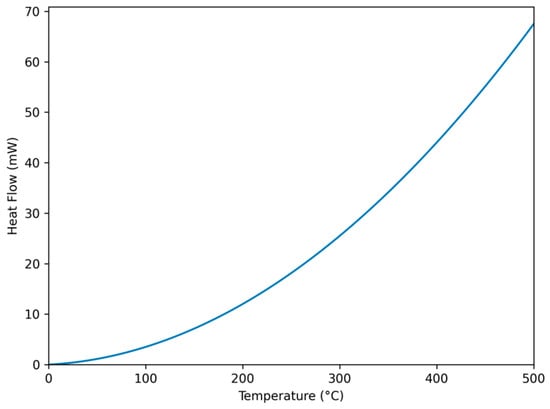

3.4. Thermodynamic Stability Analysis

The thermal behavior of EPS is an important parameter to identify potential industrial applications. When the thermal behavior of EPS obtained from P. ethanolidurans was examined, it showed a slight peak of the first heating thermogram between 70 and 100 °C instead of a sharp melting point (Figure 3). As previously reported by Singh et al., this endotherm can also be attributed to the evaporation of moisture [33]. Therefore, EPS from P. ethanolidurans should not be heated to a temperature close to 250 °C in order to not compromise the integrity of the polysaccharide structure.

Figure 3.

DSC thermograph of EPS.

3.5. Monosaccharide Composition Analysis

Gas chromatography (GC) determination showed that P. ethanolidurans EPS was a heteropolysaccharide. The total sugar content of P. ethanolidurans EPS was 73.6% and included glucose (7.59%), mannose (41.96%), fructose (16.98%), arabinose (3.15%) and rhamnose (30.30%), as shown in Table 2. The total sugar content of EPS obtained from P. ethanolidurans is 2932 cm−1, and the absorption peak in this range is 70% and consists of glucose. In addition, this EPS contains 28% mannose and 16.2% galactose [34]. This undetectable peak at 1726 cm−1 may also indicate the presence of rhamnose. According to the number of monosaccharides, uronic acid is not present in EPS. The strong band at 1646 cm−1 was assigned to the stretching vibration and the proportion of each monosaccharide; EPS differed from mannose or galactose [6]. The signal at 1544 cm−1 indicates that EPS produces an amide group (N-H), indicating protein binding, as previously reported by Ahmed et al. [35]. The peak at 1408 cm−1 consisted of glucose, mannose, and arabinose, and the peak at 1026 cm−1, formed by vibration of the O-H bond, contained galactose [36].

Table 2.

Monosaccharide composition of EPS.

The strong frequency band between 1160 cm−1 and 950 cm−1 represents mannose and fructose in different proportions [11]. Therefore, P. ethanolidurans produced a new type caused by the stretching vibration of the pyran ring, and it is the ideal fingerprint of EPS [36,37]. EPS produced by the same strains may have different monosaccharide compositions. The peak at 926 cm−1 may be due to asymmetric stretching of the glucose ring.

Previous studies have shown that the monosaccharide composition of EPS can vary by species and genus [37]. It can also be the β-configuration of sugar units [34]. Depending on the medium and conditions of the peak observed at 815 cm−1, mannose may show a characteristic absorption peak [38]. The monosaccharide composition of EPS obtained from P. ethanolidurans has not yet been found in any study in the literature. However, the monosaccharide content and number of this EPS also differ from EPS obtained from various Pediococcus species found in the literature. For example, EPS composed of glucose (79.0%), mannose (9.5%), arabinose (6.2%) and galactose (5.2%) was isolated from P.pentosaceus M41 [36]. Another study reported that EPS isolated from P.pentosaceus consisted only of glucose, mannose and fructose. Based on the monosaccharide composition of the EPS obtained in the study, it can be said that it is a new EPS. However, the following should not be overlooked; the monosaccharide composition of EPS is species- and strain-dependent [39], but is also influenced by various factors such as culture medium and culture conditions [19].

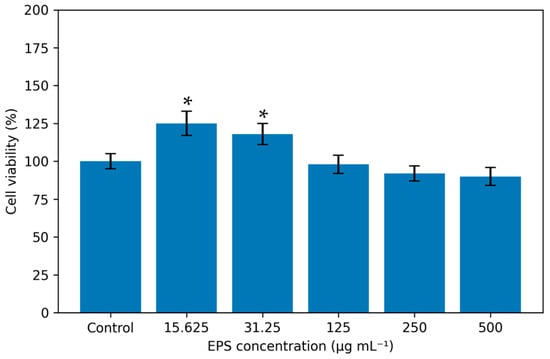

3.6. Measurement of Cytotoxicity

The inhibition of EPS from P. ethanolidurans at different concentrations (15.625–500 μg mL−1) and incubation times (24 h) against normal CCD-1079Sk cells are summarized in Figure 4. Human dermal fibroblast cells (CCD-1079Sk) were obtained from ATCC, and cell line information was confirmed via the Cellosaurus database (https://www.cellosaurus.org/CVCL_2337, accessed on 15 October 2025).

Figure 4.

MTT cytotoxicity analysis of EPS (* p < 0.05).

At the lowest concentration (15.625 μg mL−1) for incubation after 24 h, the inhibition ratio of EPS from P. ethanolidurans against CCD-1079Sk cell viability increased to 125%. According to the analytical results, the pure EPS did not cause 50% inhibition of cell viability at the concentrations tested. EPS was not found to be highly cytotoxic as IC50 values were high. However, the rest of the EPSs showed no activity against CCD-1079Sk cell line compared to control cells (Figure 4). In addition, it was found that the EPS sample had a strong proliferative effect at low concentrations.

3.7. Intrinsic Viscosity and Molecular Weight of EPS

Based on intrinsic viscosity analysis and application of the Mark–Houwink equation, the molecular weight (Mw) of the EPS produced by P. ethanolidurans was calculated as 68.2 kDa. This Mw value falls within the range reported for EPS produced by Pediococcus species, including P. acidilactici and P. pentosaceus, whose EPS molecular weights typically vary from approximately 46 to 74 kDa, depending on strain and production conditions [40,41,42]. The moderate Mw of the EPS is consistent with its heteropolysaccharide composition and semi-crystalline structure observed in XRD analysis. EPS within this Mw range are commonly associated with favorable rheological behavior, thermal stability and biological functionality. Therefore, the Mw value obtained in this study further supports the classification of P. ethanolidurans EPS as a structurally robust and functionally promising biopolymer.

3.8. Antimicrobial Activity

While pathogens cause food spoilage in vitro, they can also cause infections in the gastrointestinal tract in vivo [37]. Antibiotics can be used for bacterial infections, but with antibiotic resistance now an issue, research into safe, effective and biological antimicrobials has become a priority. Previous studies have shown that EPS derived from LAB has good antibacterial activity [43]. In a study that was conducted, it was stated that EPS obtained from LABs isolated from pickles showed potent inhibitory activity against E. coli and S. aureus, as also shown in Table 3 [44].

Table 3.

Antioxidant and antibacterial effects of the EPS.

In this study, the antimicrobial activity of EPS from P. ethanolidurans against Gram (+) and Gram (−) food pathogens was determined. According to the results obtained, EPS, L. monocytogenes, S. aureus and E. coli showed potent antibacterial activity against bacteria. Although the inhibitory effect of EPS on the three harmful bacteria is concentration-dependent, L. monocytogenes was also active against S. aureus and E. coli at concentrations of 50 mg mL−1. These results suggest that the EPS of P. ethanolidurans has the most potent inhibitory effect on L. monocytogenes, followed by E. coli, and the worst inhibitory effect on S. aureus. MIC results obtained after susceptibility testing between 50 µg mL−1 and 250 µg mL−1 were determined against L. monocytogenes and E. coli, respectively. In addition, the MBC of EPS was only determined in L. monocytogenes. MIC and MBC values could not be determined for S. aureus. The ratios MBC/MIC ≤ 2 and MBC/MIC ≥ 4 indicate bactericidal and bacteriostatic effects, respectively [45]. Based on the obtained results, the EPS produced by P. ethanolidurans did not exhibit bactericidal activity; however, the findings obtained against L. monocytogenes suggest a bacteriostatic effect.

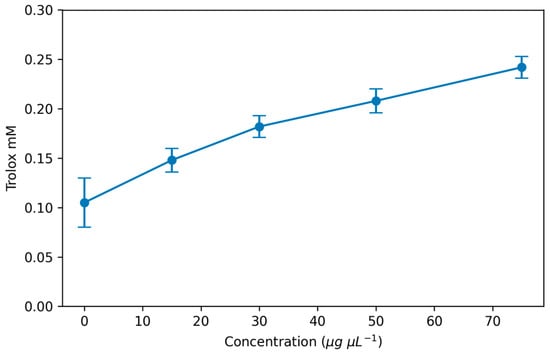

3.9. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

EPS from various sources can exhibit antioxidant effects that can scavenge active oxygen free radicals and reduce diseases incidence, as an important functional role [6]. In a previous study, EPS from L. kimchi SR8 significantly improved liver index, serum superoxide dismutase activity and survival rate in mice [46]. In addition, there are studies showing that food spoilage can be slowed down by scavenging free radicals in vitro thanks to the antioxidant properties of some EPS [47]. It seems that EPS produced by different LAB strains is a natural and safe antioxidant that could have good prospects of application in the food preservation and health products industry [6,48]. In this experiment, the in vitro antioxidant capacity of EPS obtained from P. ethanolidurans was evaluated by the ABTS radical scavenging method. According to the obtained results, it was determined that the TEAC clearance rate reached 0.24 mM. These results indicate that EPS has potential antioxidant capacity, as shown in Figure 5. This can be attributed to the hydroxyl group and the -COOH, C=O and -O- in the P. ethanolidurans polysaccharide fraction or other functional groups that can donate electrons to the reaction. And as a result, these groups can terminate the radical chain reaction with free radicals.

Figure 5.

ABTS radical scavenging activities of the EPS.

The antioxidant activity of EPS from the same or similar sources may differ. This could be mainly because the molecular weight and specific chemical composition of EPS can alter the antioxidant activity. Although the TEAC is a widely accepted free radical model, it may not be very suitable for the analysis of high-molecular-weight polysaccharides. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate EPS along with its molecular weight and ensure that it dissolves well to ensure sample bioactivity performance [48].

4. Conclusions

The occurrence of Pediococcus species during lactic acid fermentation of traditional foods has been widely reported, and members of this genus are recognized as important microorganisms in fermentation processes [49,50]. Several studies have described the properties of exopolysaccharides (EPS) isolated from Pediococcus species obtained from various food matrices. However, the present study represents the most comprehensive investigation to date on EPS produced by Pediococcus ethanolidurans.

EPS obtained from different strains of the same species may exhibit diverse physicochemical, biological, and technological properties due to variations in metabolic activity and fermentation behavior. Therefore, comparative studies focusing on strain-dependent EPS characteristics provide valuable contributions to the literature. Food-borne Pediococcus strains are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) microorganisms and play a significant role in both traditional and controlled food fermentation owing to their functional, technological and probiotic attributes.

In this study, P. ethanolidurans was successfully isolated from traditionally fermented Smilax excelsa L. pickles, and the biological and physicochemical properties of its EPS were comprehensively characterized. In addition, the cytotoxic effects of the purified EPS were evaluated using in vitro cell culture assays. Based on the obtained results, the EPS produced by P. ethanolidurans exhibited favorable technological properties, including antimicrobial activity and thermal stability.

These findings suggest that Pediococcus strains producing EPS with desirable functional characteristics may be developed as natural bioactive supplements and employed as starter or adjunct cultures in controlled food fermentation processes. Moreover, bacterial EPS derived from lactic acid bacteria are increasingly recognized for their potential applications in the food, cosmetic and packaging industries. Overall, this study provides novel and significant insights into the functional potential of EPS produced by P. ethanolidurans and represents an important contribution to the existing literature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.K., B.G. and M.T.T.; methodology, S.M.K., B.G. and M.T.T.; software, S.M.K.; validation, S.M.K.; formal analysis, S.M.K., B.G. and M.T.T.; investigation, S.M.K.; resources, M.T.T.; data curation, S.M.K., M.T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.K.; writing—review and editing, S.M.K.; visualization, S.M.K.; supervision, S.M.K.; project administration, S.M.K., funding acquisition, S.M.K., B.G. and M.T.T. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was partially supported by Gumushane University coordinator ship of scientific research projects by 20.F5115.01.06 code number.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Gumushane University for help and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ozsoy, N.; Can, A.; Yanardag, R.; Akev, N. Antioxidant activity of Smilax excelsa L. leaf extracts. Food Chem. 2008, 110, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, S. Smilax china L. (Smilacaceae). In Handbook of 200 Medicinal Plants: A Comprehensive Review of Their Traditional Medical Uses and Scientific Justifications; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1665–1671. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Y.-H.; Hsu, Y.-W.; Liaw, C.-C.; Lee, J.K.; Huang, H.-C.; Kuo, L.-M.Y. Cytotoxic Phenylpropanoid Glycosides from the Stems of Smilax china. J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 1475–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellat, M.; İşLer, C.T.; Uyar, A.; Kuzu, M.; Aydın, T.; Etyemez, M.; Türk, E.; Yavas, I.; Güvenç, M. Protective effect of Smilax excelsa L. pretreatment via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory effects, and activation of Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway in testicular torsion model. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaligh, P.; Salehi, P.; Farimani, M.M.; Ali-Asgari, S.; Esmaeili, M.A.; Nejad Ebrahimi, S. Bioactive compounds from Smilax excelsa L. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2016, 13, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, W.; Rui, X.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Jiang, M.; Dong, M. Chemical modification, characterization and bioactivity of a released exopolysaccharide (r-EPS1) from Lactobacillus plantarum. Glycoconj. J. 2015, 32, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, F.; Gao, J.-L.; Fung, K.-P.; Zheng, Y.; Lee, S.M.-Y.; Wang, Y.-T. Anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effect of Smilax glabra Roxb. extract on hepatoma cell lines. Chem. Interact. 2008, 171, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itharat, A.; Houghton, P.J.; Eno-Amooquaye, E.; Burke, P.J.; Sampson, J.H.; Raman, A. In vitro cytotoxic activity of Thai medicinal plants used traditionally to treat cancer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 90, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, E.; Turfan, N.; Özer, H.; Üstün, N.Ş.; Pekşen, A. Nutrient And Bioactive Substance Contents Of Edible Plants Grown Naturally In Salipazari (Samsun). Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2020, 19, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dertli, E.; Colquhoun, I.J.; Gunning, A.P.; Bongaerts, R.J.; Le Gall, G.; Bonev, B.B.; Mayer, M.J.; Narbad, A. Structure and Biosynthesis of Two Exopolysaccharides Produced by Lactobacillus johnsonii FI9785. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 31938–31951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Zia, K.M.; Tabasum, S.; Noreen, A.; Ali, M.; Iqbal, R.; Zuber, M. Blends and composites of exopolysaccharides; properties and applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 94, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatas, S.M.; Ekici, L.; Develi, I.; Dertli, E.; Sagdic, O. Effects of GSM 1800 band radiation on composition, structure and bioactivity of exopolysaccharides produced by yoghurt starter cultures. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, K.M.; Zannini, E.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E.K. Lactic Acid Bacteria Exopolysaccharides in Foods and Beverages: Isolation, Properties, Characterization, and Health Benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badel, S.; Bernardi, T.; Michaud, P. New perspectives for Lactobacilli exopolysaccharides. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibarburu, I.; Soria-Díaz, M.E.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, M.A.; Velasco, S.E.; Tejero-Mateo, P.; Gil-Serrano, A.M.; Irastorza, A.; Dueñas, M.T. Growth and exopolysaccharide (EPS) production by Oenococcus oeni I4 and structural characterization of their EPSs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 103, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, A.I.; Ibarburu, I.; Elizaquivel, P.; Zuriarrain, A.; Berregi, I.; López, P.; Prieto, A.; Aznar, R.; Dueñas, M.T. Disclosing diversity of exopolysaccharide-producing lactobacilli from Spanish natural ciders. LWT 2018, 90, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dols-Lafargue, M.; Lee, H.Y.; Le Marrec, C.; Heyraud, A.; Chambat, G.; Lonvaud-Funel, A. Characterization of gtf, a Glucosyltransferase Gene in the Genomes of Pediococcus parvulus and Oenococcus oeni, Two Bacterial Species Commonly Found in Wine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 4079–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llamas-Arriba, M.G.; Pérez-Ramos, A.; Puertas, A.I.; López, P.; Dueñas, M.T.; Prieto, A. Characterization of Pediococcus ethanolidurans CUPV141: A β-D-glucan- and Heteropolysaccharide-Producing Bacterium. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhou, K.; Yin, S.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C. Purification and characterization of an exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus plantarum HY isolated from home-made Sichuan Pickle. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Sun, L.; Xue, W.; Yin, N.; Zhu, W. Relationship of intrinsic viscosity to molecular weight for poly (1, 4-butylene adipate). Polym. Test. 2010, 29, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuelli, M.A. Intrinsic Viscosity Determination of High Molecular Weight Biopolymers by Different Plot Methods. Chia Gum Case. J. Polym. Biopolym. Phys. Chem. 2018, 6, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. M07-A9: Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard, 9th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Prete, R.; Dell’orco, F.; Sabatini, G.; Montagano, F.; Battista, N.; Corsetti, A. Improving the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Fermented Milks with Exopolysaccharides-Producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains. Foods 2024, 13, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.N.; Aman, A.; Silipo, A.; Qader, S.A.U.; Molinaro, A. Structural analysis and characterization of dextran produced by wild and mutant strains of Leuconostoc mesenteroides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 99, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Xia, X.; Tang, W.; Ji, J.; Rui, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, M. Structural Characterization and Anticancer Activity of Cell-Bound Exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus helveticus MB2-1. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3454–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Qi, H.-Y.; Lv, M.-L.; Kong, Y.; Yu, Y.-W.; Xu, X.-Y. Component analysis of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) during aerobic sludge granulation using FTIR and 3D-EEM technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 124, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, J.; Flemming, H.-C. FTIR-Spectroscopy in Microbial and Material Analysis. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 1998, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Sun, S.; Tian, W.; Chen, G.Q.; Huang, W. A rapid method for detecting bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates in intact cells by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 51, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badireddy, A.R.; Chellam, S.; Gassman, P.L.; Engelhard, M.H.; Lea, A.S.; Rosso, K.M. Role of extracellular polymeric substances in bioflocculation of activated sludge microorganisms under glucose-controlled conditions. Water Res. 2010, 44, 4505–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingegowada, D.C.; Kumar, J.K.; Prasad, A.D.; Zarei, M.; Gopal, S. FTIR Spectroscopic Studies on Cleome gynandra-Comparative Analysis of Functional Group Before and After Extraction. Rom. J. Biophys. 2012, 22, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, D.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X. Distinction of leukemia patients’ and healthy persons’ serum using FTIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 101, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirin, S.; Aslim, B. Characterization of Lactic Acid Bacteria Derived Exopolysaccharides for Use as a Defined Neuroprotective Agent Against Amyloid Beta1–42-Induced Apoptosis in SH-SH5Y Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.S.; Kaur, N.; Pandey, A.; Kennedy, J.F. Hyper-production of pullulan from de-oiled rice bran by Aureobasidium pullulans in a stirred tank reactor and its characterization. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 11, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanmani, P.; Satish Kumar, R.; Yuvaraj, N.; Paari, K.A.; Pattukumar, V.; Arul, V. Production and purification of a novel exopolysaccharide from lactic acid bacterium Streptococcus phocae PI80 and its functional characteristics activity in vitro. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 4827–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, Z.; Wang, Y.; Anjum, N.; Ahmad, H.; Ahmad, A.; Raza, M. Characterization of new exopolysaccharides produced by coculturing of L. kefiranofaciens with yoghurt strains. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2013, 59, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.; Abu-Jdayil, B.; Olaimat, A.; Esposito, G.; Itsaranuwat, P.; Osaili, T.; Obaid, R.; Kizhakkayil, J.; Liu, S.-Q. Physicochemical, bioactive and rheological properties of an exopolysaccharide produced by a probiotic Pediococcus pentosaceus M41. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, X.; Tian, R.; Tang, R.; Zhang, J. Characterization and Biological Activity of a Novel Exopolysaccharide Produced by Pediococcus pentosaceus SSC–12 from Silage. Microorganisms 2021, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, W.; Rui, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, M.; Dong, M. Characterization of a novel exopolysaccharide with antitumor activity from Lactobacillus plantarum 70810. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 63, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, Y.; Casillo, A.; Gharsallah, H.; Joulak, I.; Lanzetta, R.; Corsaro, M.M.; Attia, H.; Azabou, S. Production and structural characterization of exopolysaccharides from newly isolated probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 108, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Wang, X.; Ji, Q.; Bao, D.; Jin, G.; Shan, B.; Mei, L.; Qi, J. Characterization of the exopolysaccharide produced by Pediococcus acidilactici S1 and its effect on the gel properties of fat substitute meat mince. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; He, J.; Gan, L.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Yang, L.; Li, R.; Tian, Y. Exopolysaccharide Produced by Pediococcus pentosaceus E8: Structure, Bio-Activities, and Its Potential Application. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 923522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Luo, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Shan, Y.; Lu, M.; Tian, F.; Ni, Y. Exopolysaccharides produced by Pediococcus acidilactici MT41-11 isolated from camel milk: Structural characteristics and bioactive properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 1036–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nambiar, R.B.; Sellamuthu, P.S.; Perumal, A.B.; Sadiku, E.R.; Phiri, G.; Jayaramudu, J. Characterization of an exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus plantarum HM47 isolated from human breast milk. Process. Biochem. 2018, 73, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Niu, M.; Song, D.; Song, X.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Y.; Lu, B.; Niu, G. Preparation, partial characterization and biological activity of exopolysaccharides produced from Lactobacillus fermentum S1. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2020, 129, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, V.K.; Han, J.-H.; Rather, I.A.; Park, C.; Lim, J.; Paek, W.K.; Lee, J.S.; Yoon, J.-I.; Park, Y.-H. Characterization and Antibacterial Potential of Lactic Acid Bacterium Pediococcus pentosaceus 4I1 Isolated from Freshwater Fish Zacco koreanus. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, P.; Liao, Q.; Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Feng, D.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Xu, H. Extraction, purification, and antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharides produced by Lactobacillus kimchi SR8 from sour meat in vitro and in vivo. CyTA—J. Food 2021, 19, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Cheng, Q.; Abbas, Z.; Tong, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; et al. Optimization of Exopolysaccharide Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum R301 and Its Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Foods 2023, 12, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R.P.; Anandharaj, M.; David Ravindran, A. Characterization of a novel exopolysaccharide produced by Lactobacillus gasseri FR4 and demonstration of its in vitro biological properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, H.; Oliveira, M.; Aroso, R.; Cubero, N.; Hogg, T.; Teixeira, P. Antilisterial activity of lactic acid bacteria isolated from “Alheiras” (traditional Portuguese fermented sausages): In situ assays. Meat Sci. 2007, 76, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banwo, K.; Sanni, A.; Tan, H. Functional Properties of Pediococcus Species Isolated from Traditional Fermented Cereal Gruel and Milk in Nigeria. Food Biotechnol. 2013, 27, 14–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.