Adsorbed Carrier Solid-State Fermentation of Beauveria bassiana: Process Optimization and Growth Dynamics Modelization Based on an Improved Biomass Determination Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microbial Strain and Inoculum Preparation

2.2. ACSSF Experiments for Single-Factor Optimizations and ANN Optimization

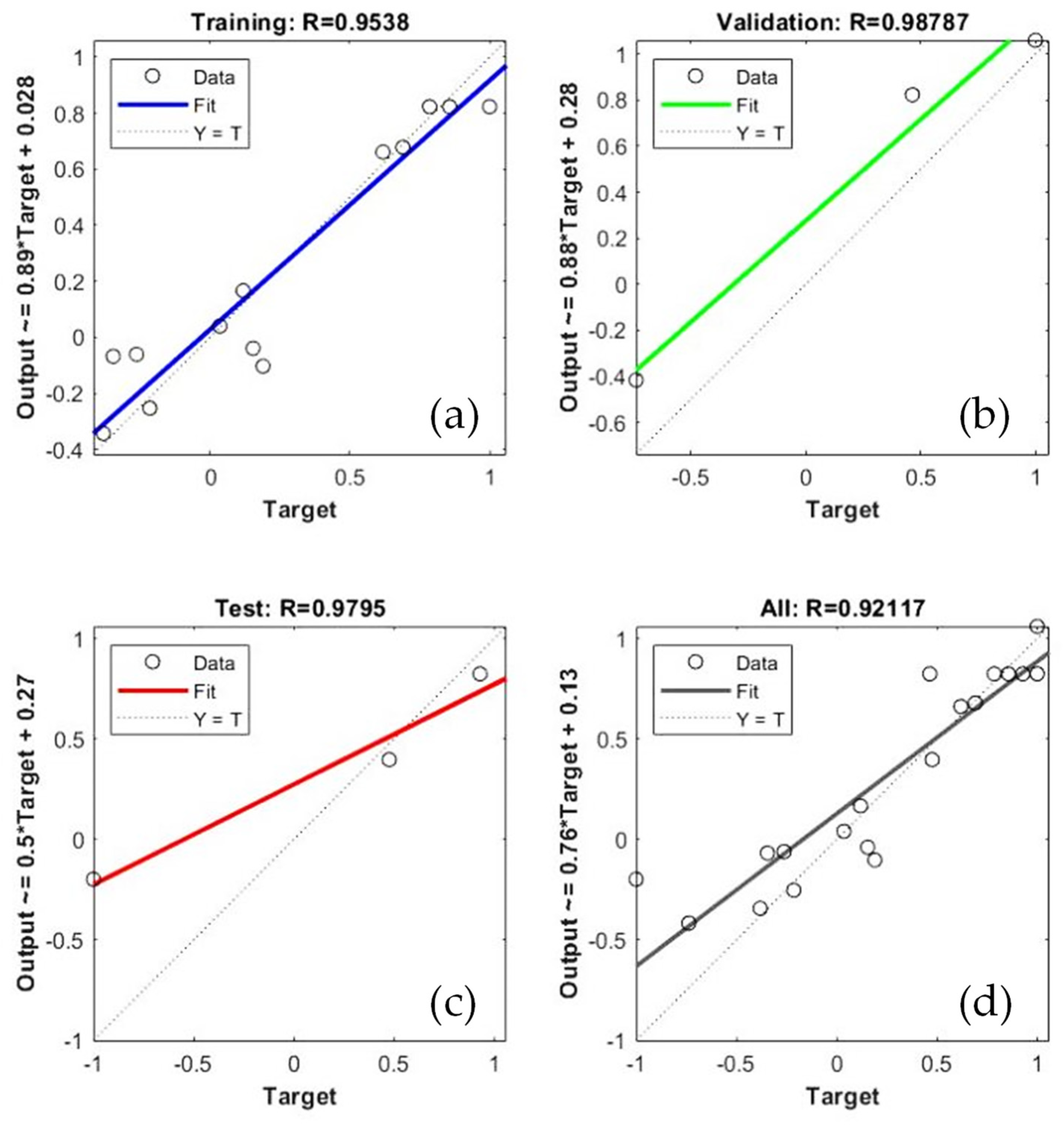

2.3. ANN-GA Optimization

2.4. Kinetic Model of Microbial Growth

2.5. Pretreatment of ACSSF Samples and Granularity Analysis

2.6. Biomass Determination (MBTH Method)

2.7. Moisture Content Determination

3. Results

3.1. The Improvement of the Pretreating Method for ACSSF Samples and the Methodological Evaluation of the Improved MBTH Method

3.2. Single-Factor Optimization

3.3. Optimization of ACSSF Media by the ANN-GA Method

3.4. The Process Dynamics of ACSSF

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lopez-Perez, M.; Rodriguez-Gomez, D.; Loera, O. Production of conidia of Beauveria bassiana in solid-state culture: Current status and future perspectives. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.X.; Luo, Q.Z.; Guo, Q.Q.; Su, R.S.; Liu, J.F.; He, H.L.; Cheng, Y.Q. Optimization of the Culture Medium of Beauveria bassiana and Spore Yield Using Response Surface Methodology. Fermentation 2024, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.L.; Kumar, A.; Chintagunta, A.D.; Samudrala, P.J.K.; Bardin, M.; Lichtfouse, E. Microbial Production of Biopesticides for Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Z.; Xia, Y.X.; Kim, B.; Keyhani, N.O. Two hydrophobins are involved in fungal spore coat rodlet layer assembly and each play distinct roles in surface interactions, development and pathogenesis in the entomopathogenic fungus, Beauveria bassiana. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 80, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.G.; Feng, J.; Fan, Y.H.; Zhang, Y.J.; Bidochka, M.J.; Leger, R.J.S.; Pei, Y. Expressing a fusion protein with protease and chitinase activities increases the virulence of the insect pathogen Beauveria bassiana. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2009, 102, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.G.; Leng, B.; Xiao, Y.H.; Jin, K.; Ma, J.C.; Fan, Y.H.; Feng, J.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Pei, Y. Cloning of Beauveria bassiana chitinase gene Bbchit1 and its application to improve fungal strain virulence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, G.M.; Jaronski, S.T. The production and uses of Beauveria bassiana as a microbial insecticide. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Zhan, F.F.; Zeng, L.Q.; Sun, Y.L.; Fu, S.H.; Fang, Y.; Lin, X.C.; Lin, H.Y.; Su, J.; Cai, S.P. Arginine accumulation suppresses heat production during fermentation of the biocontrol fungus Beauveria bassiana. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e02134-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.P.; Shi, D.X.; Li, Y.H.; He, X.Z.; Wang, X.Y.; Lin, K.; Zheng, X.L. Development of Biphasic Culture System for an Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria bassiana PfBb Strain and Its Virulence on a Defoliating Moth Phauda flammans (Walker). J. Fungi 2025, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarin, G.M.; Kobori, N.N.; Coleman, J.J.; Jackson, M.A. Impact of osmotic stress on production, morphology, and fitness of Beauveria bassiana blastospores. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 4815–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanicki, N.S.; Lopes, E.C.M.; de Lira, A.C.; Poletto, T.B.; Fonceca, L.Z.; Delalibera, I.D. Comparative analysis of Beauveria bassiana submerged conidia with blastospores: Yield, growth kinetics, and virulence. Biol. Control 2023, 185, 105314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, A.; Artola, A.; Barrena, R.; Sánchez, A. Harnessing Packed-Bed Bioreactors’ Potential in Solid-State Fermentation: The Case of Beauveria bassiana Conidia Production. Fermentation 2024, 10, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.P.; Ma, Y.Z.; Ding, W.; Jiang, Y.K.; Chen, X.M.; Chen, J.; Gao, H.L.; Xue, Y.P.; Zheng, Y.G. Efficient production of R-2-(4-hydroxyphenoxy) propionic acid by Beauveria bassiana using biofilm-based two-stage fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 399, 130588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Juache, H.R.; Avila-Hernández, J.G.; Rodríguez-Durán, L.V.; Michel, M.R.; Wong-Paz, J.E.; Muñiz-Márquez, D.B.; Veana, F.; Aguilar-Zárate, M.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Aguilar-Zárate, P. Characterization of a Biofilm Bioreactor Designed for the Single-Step Production of Aerial Conidia and Oosporein by Beauveria bassiana PQ2. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.Q.; Chen, Q.X.; Tang, T.X.; Huang, Z.G. Unraveling the water source and formation process of Huangshui in solid-state fermentation. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025, 34, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.; Uhl, P.; Zhu, Y.; Wijffels, R.H.; Xu, Y.; Rinzema, A. Modeling of industrial-scale anaerobic solid-state fermentation for Chinese liquor production. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394, 124942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, L.P.; Casciatori, F.P.; De, C.L.I.; Thoméo, J.C. Production of conidia of the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae ICB 425 in a tray bioreactor. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 42, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garro, M.S.; Rivas, F.P.; Garro, O.A. Solid State Fermentation in Food Processing: Advances in Reactor Design and Novel Applications. In Innovative Food Processing Technologies; Kai Knoerzer, K.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberghe, L.; Pandey, A.; Carvalho, J.; Letti, L.; Soccol, C.R. Solid-state fermentation technology and innovation for the production of agricultural and animal feed bioproducts. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2020, 1, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudler, S.; Bley, T. Better One-Eyed than Blind-Challenges and Opportunities of Biomass Measurement During Solid-State Fermentation of Basidiomycetes. In Filaments in Bioprocesses; Krull, R., Bley, T., Eds.; Advances in Biochemical Engineering-Biotechnology; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; Volume 149, pp. 223–252. [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki, A.; Diamantopoulou, P.; Papanikolaou, S.; Philippoussis, A. Evaluation of Biomass and Chitin Production of Morchella Mushrooms Grown on Starch-Based Substrates. Foods 2019, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wychen, S.; Long, W.; Black, S.K.; Laurens, L.M.L. MBTH: A novel approach to rapid, spectrophotometric quantitation of total algal carbohydrates. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 518, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudler, S.; Bley, T. Biomass estimation during macro-scale solid-state fermentation of basidiomycetes using established and novel approaches. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti, C.T.; Vergoignan, C.; Feron, G.; Durand, A. Glucosamine measurement as indirect method for biomass estimation of Cunninghamella elegans grown in solid state cultivation conditions. Biochem. Eng. J. 2001, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhu, W.; Gao, L. Analysis of Cell Concentration, Volume Concentration, and Colony Size of Microcystis via Laser Particle Analyzer. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 947–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Zhang, F.G.; Lü, Q.N. Ideal Laser Particle Size Analyzer and Its Lower Limit of Measurement and Resolving Power. Laser Optoelectron. Prog. 2022, 59, 1329001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciatori, F.P.; Bück, A.; Thoméo, J.C.; Tsotsas, E. Two-phase and two-dimensional model describing heat and water transfer during solid-state fermentation within a packed-bed bioreactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 287, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, Y. Spore Production of Clonostachys rosea in a New Solid-state Fermentation Reactor. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 174, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Modern Solid State Fermentation; Springer: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Chen, H.Z. Xanthan Production on Polyurethane Foam and Its Enhancement by Air Pressure Pulsation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 162, 2244–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; He, Q.; Che, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, G. Optimization and scale-up of the production of rhamnolipid by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in solid-state fermentation using high-density polyurethane foam as an inert support. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 43, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Fernandes, H.; Peres, H.; OliveTeles, A.; Salgado, J.M. Polyunsaturated fatty acids production by solid-state fermentation on polyurethane foam by Mortierella alpina. Biotechnol. Prog. 2020, 37, e3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitol, L.O.; Biz, A.; Mallmann, E.; Krieger, N.; Mitchell, D.A. Production of pectinases by solid-state fermentation in a pilot-scale packed-bed bioreactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzua, M.C.; Mussatto, S.I.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Rodriguez, R.; de la Garza, H.; Teixeira, J.A.; Aguilar, C.N. Exploitation of agro industrial wastes as immobilization carrier for solid-state fermentation. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2009, 30, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, A.; Artola, A.; Sánchez, A.; Barrena, R. Rice husk as a source for fungal biopesticide production by solid-state fermentation using B. bassiana and T. harzianum. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 296, 122322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narwade, J.D.; Odaneth, A.A.; Lele, S.S. Solid-state fermentation in an earthen vessel: Trichoderma viride spore-based biopesticide production using corn cobs. Fungal Biol. 2023, 127, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, A.; Barrena, R.; Meyling, N.V.; Artola, A. Conidia production of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana using packed-bed bioreactor: Effect of substrate biodegradability on conidia virulence. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 341, 118059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala, A.; Vittone, S.; Barrena, R.; Sánchez, A.; Artola, A. Scanning agro-industrial wastes as substrates for fungal biopesticide production: Use of Beauveria bassiana and Trichoderma harzianum in solid-state fermentation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lpdc, A.; Fpc, B.; Ivv, A.; Rlg, A.; Jct, A. Metarhizium anisopliae conidia production in packed-bed bioreactor using rice as substrate in successive cultivations. Process Biochem. 2020, 97, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viccini, G.; Mannich, M.; Capalbo, D.M.F.; Valdebenito-Sanhueza, R.; Mitchell, D.A. Spore production in solid-state fermentation of rice by Clonostachys rosea, a biopesticide for gray mold of strawberries. Process Biochem. 2007, 42, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, A.V.; Brentassi, M.E. Effectiveness of several nutritional sources on the virulence of Beauveria bassiana s.l. CEP147 against the planthopper Delphacodes kuscheli. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2022, 170, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, R.; Jakobs-Schönwandt, D.; Patel, A.V. Screening of liquid media and fermentation of an endophytic Beauveria bassiana strain in a bioreactor. AMB Express 2014, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, G.; Ragunathan, R.; Johney, J. Assessing the impact of corn steep liquor as an inducer on enhancing laccase production and laccase gene (Lac1) transcription in Pleurotus pulmonarius during solid-state fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 27, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.B.; Koucheh, M.F.; Babakhani, S.; Kafil, H.S.; Fahmi, A. Improvement of Mortar Samples Using the Bacterial Suspension Cultured in the Industrial Corn Steep Liquor Media. Ind. Biotechnol. 2022, 18, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidra, A.; Németh, A. Applicability of Neural Networks for the Fermentation of Propionic Acid by Propionibacterium acidipropionici. Period. Polytech.-Chem. Eng. 2022, 66, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.Q.; Ding, C.; Zhou, M.Z.; Wang, C.; Hu, B.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wu, Q.; Feng, N.J. Artificial Neural Network Genetic Algorithm to Optimize Yin Rice Inoculation Fermentation Conditions for Improving Physico-chemical Characteristics. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2018, 24, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.A.; Krieger, N.; Berovič, M. Solid-State Fermentation Bioreactors; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Aklilu, E.G.; Adem, A.; Kasirajan, R.; Ahmed, Y. Artificial neural network and response surface methodology for modeling and optimization of activation of lactoperoxidase system. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 37, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhao, X.Q.; Zhang, X.; Jiao, Y. Corn Steep Liquor as an Efficient Bioresource for Functional Components Production by Biotransformation Technology. Foods 2025, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Hou, Y.Y.; Du, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Dong, L.Y.; Liang, Q.L.; Wang, Y.M.; Bai, G.; Luo, G.A. Determination of Main Categories of Components in Corn Steep Liquor by Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and Partial Least-Squares Regression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 7830–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong-Rodríguez, M.J.; Maldonado-Blanco, M.G.; Hernández-Escareno, J.J.; Galán-Wong, L.J.; Sandoval-Coronado, C.F. Study of Beauveria bassiana growth, blastospore yield, desiccation-tolerance, viability and toxic activity using different liquid media. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 5736–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Q.; Pang, B.; Yang, R.R.; Liu, G.W.; Ai, C.Y.; Jiang, C.M.; Shi, J.L. Improvement of the probiotic potential and yield of Lactobacillus rhamnosus cells using corn steep liquor. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 131, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asun, A.C.; Lin, S.T.; Ng, H.S.; Lan, J.C.W. Production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) by Bacillus subtilis BBEL02 fermentation using nitrogen-rich industrial wastes as crude feedstocks. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 187, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of the Precision | Number of Repetitions | Average 2 g·cm−3 | Standard Deviation (SD) g·cm−3 | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-day | 6 | 0.0860 | 0.0029 | 3.32 |

| Inter-day | 18 | 0.0857 | 0.0032 | 3.75 |

| Factor | Level 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −α | −1 | 0 | 1 | α | |

| Carbon source dosage (B) g·cm−3 | 0.0082 | 0.0150 | 0.0250 | 0.0350 | 0.0418 |

| Nitrogen source dosage (C) g·cm−3 | 0.0040 | 0.0048 | 0.0060 | 0.0072 | 0.0080 |

| Water dosage (D) g·cm−3 | 0.2163 | 0.2300 | 0.2500 | 0.2700 | 0.2836 |

| Run No. | Carbon Source Dosage (B) g·cm−3 | Nitrogen Source Dosage (C) g·cm−3 | Water Dosage (D) g·cm−3 | Biomass Yield g·cm−3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0.1055 |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 0.1189 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 0.0951 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 0.1171 |

| 5 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 0.0930 |

| 6 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 0.1266 |

| 7 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1064 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1136 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1213 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1133 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1231 |

| 12 | −1.682 | 0 | 0 | 0.0767 |

| 13 | 1.682 | 0 | 0 | 0.0963 |

| 14 | 0 | −1.682 | 0 | 0.0921 |

| 15 | 0 | 1.682 | 0 | 0.0832 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | −1.682 | 0.1025 |

| 17 | 0 | 0 | 1.682 | 0.1046 |

| 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1266 |

| 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1210 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1249 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chang, L.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y. Adsorbed Carrier Solid-State Fermentation of Beauveria bassiana: Process Optimization and Growth Dynamics Modelization Based on an Improved Biomass Determination Method. Fermentation 2026, 12, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010015

Zhang X, Liu Y, Zhang M, Chang L, Qin Y, Zhang Y. Adsorbed Carrier Solid-State Fermentation of Beauveria bassiana: Process Optimization and Growth Dynamics Modelization Based on an Improved Biomass Determination Method. Fermentation. 2026; 12(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiaoran, Yi Liu, Miao Zhang, Liyuan Chang, Yiqi Qin, and Yaoxia Zhang. 2026. "Adsorbed Carrier Solid-State Fermentation of Beauveria bassiana: Process Optimization and Growth Dynamics Modelization Based on an Improved Biomass Determination Method" Fermentation 12, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010015

APA StyleZhang, X., Liu, Y., Zhang, M., Chang, L., Qin, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2026). Adsorbed Carrier Solid-State Fermentation of Beauveria bassiana: Process Optimization and Growth Dynamics Modelization Based on an Improved Biomass Determination Method. Fermentation, 12(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation12010015