Abstract

The growth and development of ruminants are closely linked to the stability and functional capacity of their rumen microbiota. Rumen microbiota transplantation (RMT), which entails the transfer of ruminal microorganisms and their metabolites from healthy donors to recipient animals, has emerged as a promising strategy for modulating host physiology. Accumulating evidence indicates that RMT can substantially influence nutrient digestion, immune function, and overall growth performance. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the mechanisms through which RMT affects ruminant growth and development, with particular attention to its roles in shaping microbial colonization and succession, enhancing rumen fermentation efficiency, and modulating host metabolic pathways. Together, these regulatory processes contribute to improved rumen maturation in young animals and enhanced production performance in adults. In addition, this review critically examines key factors governing the efficacy of RMT, including transplantation procedures, donor microbiota characteristics, and the physiological status of recipient animals. By integrating these insights, the present synthesis provides a conceptual framework to support the precise and effective application of RMT in the sustainable management of healthy ruminant production systems.

1. Introduction

As herbivorous mammals with a complex forestomach system, ruminants depend heavily on the fermentative capacity of the rumen to achieve both ecological adaptability and economic productivity []. The rumen hosts a dense and diverse microbial community comprising bacteria, archaea, protozoa, anaerobic fungi, and phages, which together constitute a highly interdependent symbiotic ecosystem [,,]. This microbiome functions as the central metabolic hub of the host, enabling the degradation of structural carbohydrates—such as cellulose and hemicellulose—into microbial protein, volatile fatty acids (VFAs), gases, and heat. These microbial metabolites serve as critical substrates for host energy metabolism, growth, and immune regulation [,,]. Accordingly, the diversity, stability, and functionality of the rumen microbiota are key determinants of feed efficiency, growth trajectory, production performance, and overall physiological homeostasis in ruminants [].

Historically, efforts to manipulate the rumen microbiome have largely centered on dietary interventions. One common strategy involves adjusting the dietary ratio of concentrate to roughage, thereby influencing microbial composition. For instance, high-concentrate diets markedly reduce the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and alpha-diversity indices relative to low-concentrate diets []. In contrast, increasing the proportion of forage (58:42 vs. 41:59) substantially elevates the abundance of methanogens, fungi, and fibrolytic bacteria. In goats, such dietary modifications increase the populations of Ruminococcus flavefaciens, Ruminococcus albus, Fibrobacter succinogenes, and other fibrolytic taxa, while frequently promoting the proliferation of Prevotella species—key contributors to hemicellulose and pectin degradation [].

Beyond diet composition, various feed additives—including antibiotics (e.g., monensin, lasalocid, salinomycin), probiotics, and prebiotics—have been used to modulate ruminal microbial populations and fermentation dynamics []. However, increasing concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance have accelerated the transition toward more sustainable microbial-based alternatives []. Prebiotics such as proteins, peptides, fats, and carbohydrates (e.g., galactooligosaccharides, inulin, lactulose) selectively stimulate beneficial rumen microorganisms, enhancing digestive efficiency and decreasing methane emissions per unit of feed intake [,]. Direct-fed microbials (DFMs), a more precise designation than “probiotics,” encompass lactic acid-producing and -utilizing bacteria, yeasts, and other functional microorganisms that directly influence ruminal fermentation [].

A growing body of evidence indicates that supplementation with live yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) enhances rumen microbial equilibrium by increasing total bacterial, fungal, and protozoal populations while reducing starch-degrading and lactate-producing bacteria. These shifts stabilize the ruminal environment and improve fermentation efficiency []. Additionally, early-life microbial interventions have proven particularly impactful: targeted modulation of microbial colonization during the neonatal period can promote the establishment of a more stable and functional rumen microbiome, resulting in long-term improvements in health and productivity [].

Rumen microbiota transplantation (RMT) represents an emerging intervention involving the transfer of the entire rumen microbial consortium—including bacteria, archaea, protozoa, fungi, and their associated metabolites—from a healthy donor to a recipient. The central operational principle of RMT is to remodel the recipient’s rumen ecosystem by introducing a functionally superior microbial community, thereby overcoming the inherent limitations of single-strain probiotics and achieving more profound and stable improvements in digestion, health, and productivity. This technique offers a powerful platform for dissecting host–microbe interactions and elucidating the causal roles of specific microbial communities in host physiology. By restructuring rumen microbial composition and function, RMT has the potential to modulate digestive efficiency, immune responses, and growth performance. While conventional strategies such as probiotics or feed additives introduce only limited microbial strains or indirectly influence fermentation, RMT enables the holistic transfer of entire, functionally adapted microbial consortia—facilitating direct and targeted remodeling of the rumen ecosystem and potentially yielding more consistent and substantial improvements in ruminant performance. Despite its potential, research on RMT in ruminants remains at an early stage, with current progress focused primarily on methodological refinement, microbial cultivation, and functional characterization.

This review synthesizes current knowledge on the mechanisms through which RMT influences ruminant growth and development. Specifically, it highlights how microbial transplantation reshapes rumen microbial colonization and succession, modulates fermentation patterns, alters host metabolic pathways, and enhances developmental and productive outcomes. Furthermore, the review evaluates factors that affect the efficacy and reproducibility of RMT, with the aim of establishing a conceptual and practical framework for its integration into precision livestock management and sustainable ruminant production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, USA), ScienceDirect (Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), X-MOL (X-MOL Academic Platform, Beijing, China), and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Beijing, China) for all publications available up to 15 September 2025. The search strategy centered on the core concepts “rumen,” “microbiota,” and “transplantation.” The following Boolean expression served as a general template and was adapted to the syntax requirements of each database:

*(rumen OR ruminant) AND (microbiota OR microbiome) AND (transplant OR transfaunation)**.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria:

- (1)

- Original research studies in which rumen microbiota transplantation (RMT) was the principal experimental treatment;

- (2)

- Studies employing ruminants (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats) or artificial rumen systems (e.g., Rusitec, continuous-culture fermenters);

- (3)

- Studies evaluating the effects of RMT on rumen microbial communities, fermentation characteristics, host metabolism, or production performance.

Exclusion criteria:

- (1)

- Non-original literature (e.g., reviews, commentaries);

- (2)

- Duplicate publications;

- (3)

- Studies lacking accessible full text;

- (4)

- Research not aligned with the primary objectives of this review.

2.3. Literature Screening and Data Extraction

All retrieved references were imported into NoteExpress (Version 3.2.0, Aegean Software, Beijing, China) for organization and deduplication. Titles and abstracts were initially screened for relevance, followed by full-text evaluation based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Reference lists of included studies were manually examined to identify additional relevant literature. Literature screening and data extraction were conducted independently by two reviewers (Yirun Zhao and Yutao Qiu) to minimize selection bias. Discrepancies regarding study eligibility were resolved through discussion or, when necessary, adjudicated by a third senior author (Zhiqing Li).

2.4. Results of Literature Screening

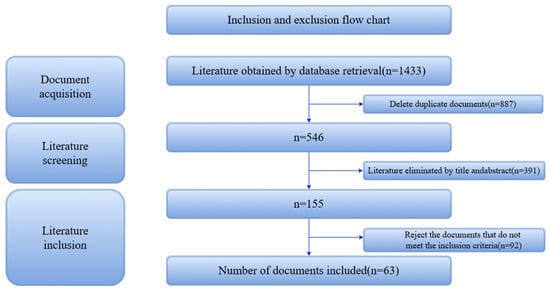

The initial database search yielded 1433 records. After removal of duplicates, 546 articles remained for further screening. Based on title and abstract evaluation, 391 records were excluded. Following full-text assessment, a total of 63 studies met all criteria and were included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Literature screening flowchart.

3. Methods of Rumen Microbiota Transplantation

Rumen microbiota transplantation (RMT) methods can be broadly categorized into two types based on the source of inoculum. The first involves the direct acquisition and transfer of rumen fluid or contents from donor to recipient animals, typically administered into the recipient’s rumen via various delivery methods. The second entails functional microbial transplantation, in which specific microbial consortia or single strains with targeted functions are identified through metagenomic or other high-throughput analyses, cultured in vitro, and subsequently transplanted.

3.1. Content Transplantation

The earliest record of content transplantation dates back to the 18th century. Over time, the procedures for rumen content acquisition have evolved, and four principal approaches are currently recognized:

- Via rumen fistula—This minimally invasive technique allows for the collection of 8–16 L of active rumen fluid from the donor. It enables precise donor health control and repeatable sampling but requires surgical fistula implantation.

- Via oral or nasogastric tube—A non-surgical, flexible method applicable to animals without fistulas. It allows for the collection of 1–4 L per session but requires stringent donor screening to prevent pathogen transmission.

- Via regurgitated bolus—A traditional and simple approach involving the feeding of chewed cud from healthy animals to sick recipients. However, the microbial and substrate concentrations are relatively low.

- Slaughterhouse collection—Provides large volumes of rumen material and is useful when live donors are unavailable. Nonetheless, it carries a high risk of pathogen contamination and decreased microbial activity due to unknown donor background, feed withdrawal, and transport conditions [].

Each method presents distinct advantages and limitations; the optimal choice depends on practical objectives, resource availability, and production conditions.

Transplantation methods also vary depending on the form of inoculum, including direct oral administration of fresh rumen fluid [], oral administration of frozen rumen fluid [], oral administration of freeze-dried rumen fluid [], and direct transplantation of rumen contents [].

Among these, oral administration of fresh rumen fluid is most common due to its simplicity and the high activity of its microbial population—including bacteria, protozoa, and fungi—facilitating rapid colonization of the recipient rumen. For example, Huuki et al. described the oral administration of freshly collected rumen fluid to calves via a silicone tube connected to a syringe [].

For frozen rumen fluid, samples are typically aliquoted and stored at −80 °C for up to 30 days, then thawed in a 39 °C water bath for 2 h before use []. Although a strong correlation (R2 ≥ 0.95) has been reported between the microbial compositions of frozen and fresh fluids, the in vitro degradation capacity of frozen samples is significantly lower []. However, preservation efficacy can be enhanced using optimized cryoprotectant solutions. Denek et al. demonstrated that frozen rumen fluid supplemented with 5% DMSO retained digestibility comparable to fresh rumen fluid in vitro []. Therefore, while frozen storage extends preservation and enables long-distance transport, it entails notable microbial loss, particularly among strict anaerobes and protozoa, and incurs higher preservation costs.

The freeze-drying method involves centrifugation of rumen fluid at 500× g for 5 min to remove large particles, followed by centrifugation at 24,000× g at 4 °C for 20 min to collect microbial cells. The resulting pellet is resuspended in 10% skim milk, mixed thoroughly, and vacuum freeze-dried. The obtained powder (corresponding to 40 mL of rumen fluid per 1 g of powder) is sealed and stored at −20 °C. Before use, it is reconstituted with phosphate buffer, centrifuged, and the supernatant is utilized []. Freeze-dried inocula exhibit excellent stability, remaining viable for over a year at 4 °C without a cold chain, making them suitable for large-scale and long-distance applications.

Existing studies exhibit significant variation, with inoculation doses typically reported as a volume of rumen fluid (e.g., 10–50 mL/kg body weight for neonates, 1–4 L per session for adults) or an equivalent of microbial biomass, and frequencies ranging from a single administration to multiple inoculations over days or weeks []. Each method presents distinct advantages and limitations; the optimal choice depends on practical objectives, resource availability, and production conditions.

3.2. Functional Microbiota Transplantation

The primary objective of functional microbiota transplantation (FMT) in ruminants is to enhance rumen fermentation efficiency, reduce methane emissions, improve nutrient absorption, and prevent metabolic or infectious diseases by transferring microbial communities with defined physiological functions. This approach integrates metagenomic insights with culturomics, enabling the isolation and transplantation of targeted microbial consortia.

Metagenomic sequencing plays a pivotal role in identifying donor microorganisms with desired metabolic capabilities, particularly those involved in fiber degradation. Through metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) analysis, Ghareschahi et al. reported that taxa belonging to Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Fibrobacteres harbor abundant carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) responsible for degrading cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, rendering them promising functional donors []. Similarly, It was demonstrated that metagenomic analyses can comprehensively characterize rumen microbial composition without the constraints of traditional culturing, allowing precise identification and enrichment of microbial populations with superior fiber-degrading capacity [].

This pre-screening of donor rumen samples for functional microorganisms via metagenomic data has been shown to improve transplantation efficiency, providing a molecular basis for accelerating the maturation of fiber digestion systems in recipient animals. Furthermore, the in vitro construction and subsequent transplantation of targeted microbial consortia validate the feasibility of precision microbiota transplantation as a scalable and controlled strategy in ruminant production []. Nevertheless, further research is required to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underpinning host–microbiota interactions during and after transplantation.

4. Remodeling Effects of Rumen Microbiota Transplantation on Microbial Communities

4.1. Adaptive Changes and Metabolic Diversity of Microbial Communities

Rumen microbiota transplantation accelerates microbial colonization and promotes the maturation of the rumen ecosystem. Newborn ruminants possess an almost sterile rumen, and initial microbial colonization occurs primarily through vertical maternal transmission (via the birth canal, skin, and saliva) and environmental exposure []. Colonization begins within hours after birth, progressing from an early dominance of facultative anaerobes such as Streptococcus to the emergence of functional groups including cellulolytic bacteria and methanogens, culminating in a stable community dominated by Prevotella and Bacteroides prior to starter feeding.

This successional process is strongly influenced by diet composition, particularly the starch-to-fiber ratio, during the early postnatal period (3–4 weeks). During this critical window, volatile fatty acids (VFAs) produced from fermentation, especially butyrate, play a key role in stimulating rumen epithelial growth and functional development. The microbial community established during the transition from milk to solid feed is critical, directly shaping post-weaning growth and production efficiency.

Traditionally, adaptive microbial shifts during dietary transitions were modulated via feed formulation: high-starch diets promote starch-degrading bacteria, whereas roughage enrichment favors fiber-degrading populations []. In contrast, RMT offers a more directed ecological intervention. Inoculation with mature rumen fluid (whether fresh, frozen, or freeze-dried) consistently enriches key bacterial genera in recipients, including Eubacterium (Firmicutes), Acidiphilium (Proteobacteria), and Polaribacter (Bacteroidetes) []. This microbial shift drives a beneficial change in fermentation patterns, specifically by increasing propionate concentration and lowering the acetate-to-propionate ratio.

In fresh dairy cows, transplantation of rumen fluid from high-yielding donors did not significantly change overall microbial diversity but selectively reshaped functionally relevant taxa and pathways, modulating amino acid, fatty acid, and bile acid metabolism []. These findings suggest that RMT can strategically remodel microbial networks to improve host metabolic efficiency and resilience.

Overall, the rumen microbiome is a dynamic ecosystem whose adaptability and metabolic diversity represent key levers for optimizing dairy production efficiency and environmental sustainability []. Consequently, RMT can serve as an ecological pre-adaptation tool that accelerates microbial succession, reconstructs metabolic networks, and synchronizes host–microbe–metabolite interactions during critical developmental or periparturient stages—ultimately enhancing production performance and reducing environmental burden.

4.2. Interactions and Optimization Among Microbial Communities

Rumen microbiota transplantation is not merely a mechanical transfer of donor microbes into the recipient rumen; rather, it represents a dynamic reconfiguration of microbial community interactions. A defining feature of the rumen ecosystem is its high functional redundancy []. This means that despite comprising hundreds of microbial species, the core metabolic tasks are relatively few. This redundancy allows for flexibility and functional compensation following transplantation.

For example, transplantation of microbiota from low-methane-emitting donors enriched in Prevotella lacticifex and Succinivibrionaceae into high-methane emitters resulted in suppression of methanogenic archaea via interspecies hydrogen competition []. Similarly, in cases of subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), transplantation of healthy rumen content effectively excluded Treponema-associated dysbiosis, restored fiber-degrading bacterial populations, and reestablished fermentative balance [].

Microbial networks in the rumen encompass not only competitive but also mutualistic and syntrophic relationships. For instance, acetogenic bacteria (e.g., Blautia) compete with methanogens for hydrogen, thereby limiting the substrate for methane production. Simultaneously, γ-proteobacteria divert carbon flux through the succinate pathway. Together, these interdependent metabolic interactions shunt carbon and electrons away from methanogenesis, effectively reducing methane emissions [].

A pivotal study investigating microbial interactions utilized rumen content transplantation from bison—a species renowned for its efficient fiber digestion—into healthy cattle []. Despite maintaining an identical diet post-transplantation, the introduced bison microbiota successfully reconfigured the rumen ecosystem. This was characterized by the proliferation of Ostracodinium protozoa, which enhanced proteolysis, and its synergy with enriched Christensenellaceae. This optimized microbial network resulted in a significant 3.2% increase in nitrogen digestibility (66.5% vs. 63.3%) and a remarkable 150% improvement in nitrogen retention (13.2 vs. 5.3 g/d). This case demonstrates that RMT can introduce a functionally superior consortium whose interactions and metabolic output can override the baseline state of a healthy microbiota, leading to enhanced nutrient utilization even without dietary changes.

Collectively, these findings illustrate that RMT induces functional reprogramming at the community level—introducing exogenous microbiota disrupts existing niche equilibria, initiating competitive exclusion, metabolic shunting, and complementary symbiosis that drive optimized fermentation outcomes. Future research should focus on spatial dynamics and metabolic flux partitioning within transplanted microbial consortia, advancing RMT from an empirical intervention to a precision-guided regulatory strategy.

In summary, RMT significantly modifies the microbial composition and metabolic functions of recipient animals by integrating exogenous microbiota into endogenous networks. Table 1 summarizes representative changes in microbial taxa and metabolic profiles observed across different rumen fluid or content transplantation studies.

Table 1.

Summary of Effects of Rumen Microbiota Transplantation on Recipient Microbial Communities, Metabolites, and Production Health.

5. Application of Rumen Microbiota Transplantation in Ruminant Production

5.1. Regulation of Rumen Fermentation and Nutrient Metabolism

Rumen microbiota transplantation (RMT) directly modulates rumen fermentation dynamics and nutrient metabolic fluxes by restructuring the microbial community. Plant cell wall polysaccharides—particularly lignocellulose—represent the primary energy source in ruminant diets; however, their complex architecture necessitates coordinated degradation by diverse rumen microorganisms [,]. In an artificial rumen system, Oss et al. demonstrated that mixed inoculation with microbial consortia derived from cattle (Bos taurus) and bison (Bison bison) elicited pronounced synergistic effects. When the two inocula were combined at specific ratios (e.g., 67:33 or 33:67), dry matter (DM) and neutral detergent fiber (aNDF) degradation of barley straw increased significantly compared with single-inoculum treatments (p < 0.05). Moreover, nitrogen degradation in concentrate feeds increased linearly with the proportion of bison inoculum (p < 0.04) [].

In contrast, Nguyen et al. reported that transplantation of bison rumen microbiota into heifers resulted in persistent downregulation of microbial genes involved in nitrogen metabolism and oxidative stress responses, without accompanying improvements in fiber digestion or production traits []. Collectively, these findings suggest that although RMT can enhance fiber and nitrogen utilization via microbial community complementarity in vitro, its in vivo performance is often constrained by host regulatory mechanisms and environmental adaptation. This disparity underscores the need to move beyond simplistic “community replacement” paradigms to identify the key drivers of metabolic reprogramming—particularly volatile fatty acids (VFAs), the end products of microbial fermentation and primary energy substrates for the host [,].

Several studies support this perspective. Inoculation of young goats with rumen fluid from adult animals enhanced fiber degradation capacity through multi-kingdom interactions (bacteria–fungi–protozoa), resulting in marked increases in ruminal butyrate and propionate concentrations (92% and 19%, respectively) alongside decreased acetate production. This VFA shift indicates improved fermentation efficiency after transplantation []. However, in identical twin calves, early rumen fluid inoculation yielded only a transient increase in butyrate proportion at 3 months of age (p = 0.04), with no long-term differences in other VFA parameters. As animals matured, both groups exhibited rising acetate levels and declining propionate/butyrate ratios, with no significant between-group differences []. Similarly, Zhou et al. observed no notable changes in total VFAs, ammonia-N, or other fermentation indices after cross-inoculating rumen fluid between high- and low-feed-intake ruminants [].

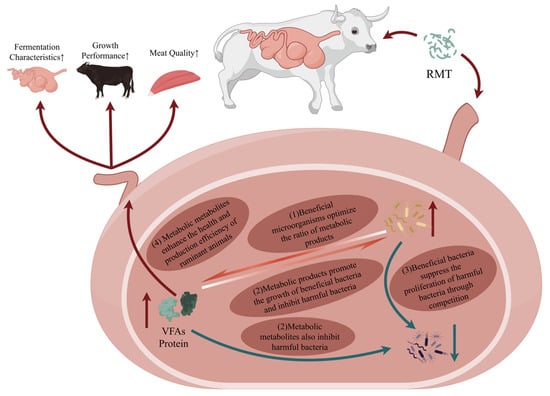

In summary, RMT holds substantial potential to modulate rumen fermentation and nutrient metabolism by reconfiguring microbial consortia, thereby optimizing fiber digestion and VFA generation to enhance energy utilization. Nevertheless, existing research reveals inconsistent outcomes. Variability in fiber degradation, nitrogen metabolism, and VFA profiles is strongly influenced by host species, individual variation, microbial colonization capacity, and host–microbiota interactions [,]. These findings highlight the complexity of translating in vitro “community complementarity” into in vivo “functional integration,” emphasizing that microbial replacement alone is insufficient to guarantee functional benefits. The complex interactions between transplanted microbiota, rumen fermentation, and host physiology are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic Diagram of the Mechanism of Rumen Microbiota Transplantation on Ruminant Growth and Development. (Arrows indicate the following: upward arrow (↑) for increase, downward arrow (↓) for decrease, and circular arrow (↷/↶) for direction).

5.2. Regulation of Gut Health and Microbiota Composition

Given the central role of RMT in modulating rumen fermentation and nutrient metabolism, its influence naturally extends to the intestinal tract—the primary site for nutrient absorption and a key barrier governing immune and microbial homeostasis []. Understanding the downstream impacts of RMT on intestinal physiology and hindgut microbial ecology is therefore essential for a holistic evaluation of its effects on ruminant health.

Emerging evidence indicates that exogenous microbial interventions, including rumen fluid inoculation, can direct gastrointestinal microbiota assembly in young ruminants, promoting microbial diversity and colonization by functional core taxa. These changes enhance digestive efficiency and mitigate post-weaning growth setbacks [,]. Following multiple RMTs in calves, Succinivibrionaceae and Prevotella became dominant taxa. Succinivibrionaceae promoted propionate production, lowered intestinal pH, and suppressed enteric pathogens such as Escherichia coli. Meanwhile, Prevotella facilitated cellulose degradation and nutrient absorption while reducing hindgut fermentation burden. Collectively, these shifts were associated with reduced diarrhea incidence and increased hindgut microbial diversity [].

Similarly, Bu et al. (2020) showed that repeated inoculation of adult dairy cows with donor rumen fluid enriched beneficial taxa (e.g., RFN20) and reduced opportunistic pathogens such as Megasphaera via competitive exclusion, culminating in a 36% reduction in diarrhea frequency (p < 0.01) []. Beyond compositional changes, RMT also protects gut epithelial integrity. In a sheep acidosis model, RMT accelerated microbial homeostasis restoration, rebalanced fermentation, and alleviated ruminal papilla damage. These benefits coincided with decreased ruminal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) concentrations, increased papilla length, downregulation of TNF-α, upregulation of IL-10, and enhanced expression of tight junction proteins (Claudin-1, Claudin-4), collectively strengthening epithelial barrier function and attenuating local inflammation [].

However, RMT effects are highly dependent on developmental stage. Yin et al. (2021) reported that transplantation of rumen fluid from adult sheep (AT group) or 3-month-old lambs (LT group) into weaned lambs accelerated gastrointestinal microbiota maturation but concurrently induced adverse outcomes, including elevated serum inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IFN-α) and increased intestinal permeability marker D-lactate, indicative of epithelial barrier disruption and immune activation []. The main effects of RMT on gut health and immunity, including changes in microbial composition, gut barrier function, and inflammatory responses, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the Main Effects of Rumen Microbiota Transplantation (RMT) on Gut Health and Immunity in Ruminants.

5.3. Impacts on Host Health and Growth Performance

The regulatory effects of RMT on rumen fermentation and intestinal health, as described above, ultimately shape systemic host physiology, influencing growth trajectories, metabolic homeostasis, and immune function. Importantly, these effects are strongly context- and stage-dependent. While RMT can be especially beneficial in neonatal or pathological conditions by improving nutrient utilization efficiency and reinforcing mucosal barrier integrity, its application during transitional periods such as weaning may provoke undesirable inflammatory responses []. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of the host’s developmental and physiological status is essential to maximize therapeutic benefits and minimize potential risks.

Despite these considerations, when implemented appropriately, RMT has repeatedly been shown to exert multifaceted benefits on lamb growth, digestion, and overall health. It was reported that lambs inoculated with active rumen fluid recovered from weight loss earlier than controls (day 9 vs. day 12) and exhibited significantly greater average daily gain (ADG) []. Similarly, it was found that early-weaned lambs receiving fresh rumen fluid displayed a 17% increase in ADG and a 13.5% reduction in feed conversion ratio (FCR) []. Beyond improvements in growth, RMT also modulates systemic metabolic profiles. It was observed that a 66% increase in serum alkaline phosphatase and a 37% increase in high-density lipoprotein (HDL), suggesting enhanced bone metabolism and increased anti-inflammatory capacity []. Additionally, it was demonstrated that inoculation with solid-phase rumen microbiota significantly elevated serum total bile acids (p < 0.05), thereby improving lipid digestion and energy utilization [].

RMT also promotes beneficial shifts in rumen fermentation parameters. It was also reported a 34.6% increase in neutral detergent fiber (NDF) digestibility and altered VFA profiles in lambs receiving fresh rumen fluid, reflecting enhanced fiber degradation efficiency [].It was further observed an increase in Bacteroidetes abundance, consistent with improved polysaccharide hydrolysis []. At the same time, RMT reduces pathogen burdens and modulates inflammatory status. It was documented a 45% decrease in Escherichia-Shigella abundance and an increase in beneficial Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group populations []. It was similarly found reductions in Clostridium sensu stricto and Fusobacterium, accompanied by downregulation of arachidonic acid metabolism pathways, indicating diminished production of pro-inflammatory lipid mediators [].

Collectively, these findings show that by restructuring the rumen microbial community and enhancing its function, RMT exerts broad regulatory effects on host health and growth. These include improvements in growth performance, metabolic and immunological profiles, and intestinal health []. Central to these outcomes is the RMT-mediated enhancement of nutrient assimilation and stabilization of the gut–microbiota axis. Through these synergistic improvements, RMT fosters improved growth trajectories and production outcomes. Consequently, RMT represents not only a valuable model for dissecting host–microbiota interactions but also a promising biotechnological strategy for advancing ruminant health management and sustainable production efficiency [].

6. Summary

Based on the 63 studies included in this review, rumen microbiota transplantation (RMT) emerges as a potent bioregulatory strategy capable of reshaping rumen microbial ecosystems to substantially influence nutrient metabolism, gastrointestinal health, and growth performance in ruminants. Its primary value lies in its ability to enhance nutrient utilization efficiency and reinforce physiological resilience. Although RMT has demonstrated potential to improve fermentation efficiency, epithelial barrier integrity, and overall productivity, its outcomes remain highly context-dependent and are often constrained by complex host–microbe–environment interactions [].

Moreover, the potential risks associated with microbial transfer—such as inadvertent pathogen transmission or induction of dysbiosis—necessitate careful donor selection and stringent biosafety measures. To realize the full potential of RMT, future research must focus on developing standardized operational frameworks. These include: Refining donor selection criteria based on functional microbial traits rather than solely on apparent health status; Determining optimal transplantation timing in relation to host developmental stages (e.g., neonatal versus weaning periods) to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse effects; Leveraging multi-omics approaches to mechanistically delineate causal relationships among transplanted microbiota, their metabolic activities, and host physiological outcomes [].

Future work should prioritize elucidating the molecular mechanisms of host–microbe communication, mapping the spatial organization of microbial interactions, and characterizing metabolic fluxes to optimize donor selection, transplantation protocols, and timing strategies. Through these advances, RMT has the potential to become a safe, precise, and highly effective biotechnological tool for promoting sustainable ruminant production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and Z.L.; methodology, E.L. and Y.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Q.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and E.L.; project administration, X.M. and Z.L.; funding acquisition, D.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (CARS-37).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, R.; Chang, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, G.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, G. Response of Rumen Microorganisms to pH during Anaerobic Hydrolysis and Acidogenesis of Lignocellulose Biomass. Waste Manag. 2024, 174, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, I.; Jami, E. Review: The Compositional Variation of the Rumen Microbiome and Its Effect on Host Performance and Methane Emission. Animal 2018, 12, s220–s232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, É.B.R.D.; Silva, J.A.R.D.; Silva, W.C.D.; Belo, T.S.; Sousa, C.E.L.; Santos, M.R.P.D.; Neves, K.A.L.; Rodrigues, T.C.G.D.C.; Camargo-Júnior, R.N.C.; Lourenço-Júnior, J.D.B. A Review of the Rumen Microbiota and the Different Molecular Techniques Used to Identify Microorganisms Found in the Rumen Fluid of Ruminants. Animals 2024, 14, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, R.R.; Faciola, A.P. Ruminal Phages—A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 763416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, C.; Crispie, F.; Lewis, E.; Reid, M.; O’Toole, P.W.; Cotter, P.D. The Rumen Microbiome: A Crucial Consideration When Optimising Milk and Meat Production and Nitrogen Utilisation Efficiency. Gut Microbes 2019, 10, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, G.; Huang, X. Effects of Chlortetracycline Rumen-Protected Granules on Rumen Microorganisms and Its Diarrhea Therapeutic Effect. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 840442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, B.-S.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.C.; Wen, J.; Cao, S.; Zhang, K.; Li, Q.; Yuan, H. Persistent Action of Cow Rumen Microorganisms in Enhancing Biodegradation of Wheat Straw by Rumen Fermentation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 715, 136529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharechahi, J.; Vahidi, M.F.; Sharifi, G.; Ariaeenejad, S.; Ding, X.-Z.; Han, J.-L.; Salekdeh, G.H. Lignocellulose Degradation by Rumen Bacterial Communities: New Insights from Metagenome Analyses. Environ. Res. 2023, 229, 115925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. The Effects of Different Concentrate-to-Forage Ratio Diets on Rumen Bacterial Microbiota and the Structures of Holstein Cows during the Feeding Cycle. Animals 2020, 10, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.J.; Mao, S.Y.; Long, L.M.; Zhu, W.Y. Effect of Disodium Fumarate on Microbial Abundance, Ruminal Fermentation and Methane Emission in Goats under Different Forage: Concentrate Ratios. Animal 2012, 6, 1788–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirase, N.K.; Greene, L.W.; Schelling, G.T.; Byers, F.M. Effect of Magnesium and Potassium on Microbial Fermentation in a Continuous Culture Fermentation System with Different Levels of Monensin or Lasalocid. J. Anim. Sci. 1987, 65, 1633–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anee, I.J.; Alam, S.; Begum, R.A.; Shahjahan, R.M.; Khandaker, A.M. The Role of Probiotics on Animal Health and Nutrition. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2021, 82, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Wojnarowski, K.; Cholewińska, P.; Szeligowska, N.; Bawej, M.; Pacoń, J. Selected Alternative Feed Additives Used to Manipulate the Rumen Microbiome. Animals 2021, 11, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacharodi, A.; Hassan, S.; Ahmed, Z.H.T.; Singh, P.; Maqbool, M.; Meenatchi, R.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Sharma, A. The Ruminant Gut Microbiome vs Enteric Methane Emission: The Essential Microbes May Help to Mitigate the Global Methane Crisis. Environ. Res. 2024, 261, 119661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholif, A.E.; Anele, A.; Anele, U.Y. Microbial Feed Additives in Ruminant Feeding. AIMS Microbiol. 2024, 10, 542–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Choi, S.H.; Nogoy, K.M.; Liang, S. Review: The Development of the Gastrointestinal Tract Microbiota and Intervention in Neonatal Ruminants. Animal 2021, 15, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Chang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, L.; Meng, Q. Effect of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae on Alfalfa Nutrient Degradation Characteristics and Rumen Microbial Populations of Steers Fed Diets with Different Concentrate-to-Forage Ratios. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePeters, E.J.; George, L.W. Rumen Transfaunation. Immunol. Lett. 2014, 162, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, G.; Liu, Z.; Wu, P.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J. Repeated Inoculation with Fresh Rumen Fluid before or during Weaning Modulates the Microbiota Composition and Co-Occurrence of the Rumen and Colon of Lambs. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.Y.; Zhou, J.W.; Yi, S.Y.; Wang, M.; Tan, Z.L. In Vitro Inoculation of Fresh or Frozen Rumen Fluid Distinguishes Contrasting Microbial Communities and Fermentation Induced by Increasing Forage to Concentrate Ratio. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 772645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Shi, W.; Yang, B.; Gao, G.; Chen, H.; Cao, L.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J. Effects of Repeated Oral Inoculation of Artificially Fed Lambs with Lyophilized Rumen Fluid on Growth Performance, Rumen Fermentation, Microbial Population and Organ Development. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2020, 264, 114465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chai, S.; Pang, K.; Wang, X.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Dong, T.; Huang, W.; et al. Ruminal Fluid Transplantation Accelerates Rumen Microbial Remodeling and Improves Feed Efficiency in Yaks. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huuki, H.; Ahvenjärvi, S.; Lidauer, P.; Popova, M.; Vilkki, J.; Vanhatalo, A.; Tapio, I. Fresh Rumen Liquid Inoculant Enhances the Rumen Microbial Community Establishment in Pre-Weaned Dairy Calves. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 758395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanghero, M.; Chiaravalli, M.; Colombini, S.; Fabro, C.; Froldi, F.; Mason, F.; Moschini, M.; Sarnataro, C.; Schiavon, S.; Tagliapietra, F. Rumen Inoculum Collected from Cows at Slaughter or from a Continuous Fermenter and Preserved in Warm, Refrigerated, Chilled or Freeze-Dried Environments for In Vitro Tests. Animals 2019, 9, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A.S.; Mohamed, R.A.I. Fresh or Frozen Rumen Contents from Slaughtered Cattle to Estimatein Vitro Degradation of Two Contrasting Feeds. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 57, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denek, N.; Can, A.; Avci, M. Frozen Rumen Fluid as Microbial Inoculum in the Two-Stage in Vitro Digestibility Assay of Ruminant Feeds. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 40, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, D.; Hendriks, W.H.; Xiong, B.; Pellikaan, W.F. Starch and Cellulose Degradation in the Rumen and Applications of Metagenomics on Ruminal Microorganisms. Animals 2022, 12, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, M.H.; Hammon, H.M.; Koch, C. Early Rumen Development in Calves: Biological Processes and Nutritional Strategies—A Mini-Review. JDS Commun. 2025, 6, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Q.; Zhang, R.; Fu, T. Review of Strategies to Promote Rumen Development in Calves. Animals 2019, 9, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Abecia, L.; Newbold, C.J. Manipulating Rumen Microbiome and Fermentation through Interventions during Early Life: A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.A.; Hassan, F.; Rehman, M.S.; Huws, S.A.; Cheng, Y.; Din, A.U. Gut Microbiome Colonization and Development in Neonatal Ruminants: Strategies, Prospects, and Opportunities. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zheng, G.; Men, H.; Wang, W.; Li, S. The Response of Fecal Microbiota and Host Metabolome in Dairy Cows Following Rumen Fluid Transplantation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 940158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.-Y.; Sun, H.-Z.; Wu, X.-H.; Liu, J.-X.; Guan, L.L. Multi-Omics Reveals That the Rumen Microbiome and Its Metabolome Together with the Host Metabolome Contribute to Individualized Dairy Cow Performance. Microbiome 2020, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, P.J. Redundancy, Resilience, and Host Specificity of the Ruminal Microbiota: Implications for Engineering Improved Ruminal Fermentations. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkai, T.; Takizawa, S.; Fujimori, M.; Mitsumori, M. —Invited Review—The Role of Rumen Microbiota in Enteric Methane Mitigation for Sustainable Ruminant Production. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.Y.; Qi, W.P.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Mei, S.J.; Mao, S.Y. Changes in Rumen Fermentation and Bacterial Community in Lactating Dairy Cows with Subacute Rumen Acidosis Following Rumen Content Transplantation. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 10780–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Álvaro, M.; Auffret, M.D.; Stewart, R.D.; Dewhurst, R.J.; Duthie, C.-A.; Rooke, J.A.; Wallace, R.J.; Shih, B.; Freeman, T.C.; Watson, M.; et al. Identification of Complex Rumen Microbiome Interaction Within Diverse Functional Niches as Mechanisms Affecting the Variation of Methane Emissions in Bovine. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, G.O.; Oss, D.B.; He, Z.; Gruninger, R.J.; Elekwachi, C.; Forster, R.J.; Yang, W.; Beauchemin, K.A.; McAllister, T.A. Repeated Inoculation of Cattle Rumen with Bison Rumen Contents Alters the Rumen Microbiome and Improves Nitrogen Digestibility in Cattle. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, X.; Hu, M.; Hou, J.; Du, Y.; Si, W.; Yang, L.; Xu, L.; Xu, Q. Modulating Gastrointestinal Microbiota to Alleviate Diarrhea in Calves. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1181545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, A.; Palma-Hidalgo, J.M.; Jiménez, E.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. Enhancing Rumen Microbial Diversity and Its Impact on Energy and Protein Metabolism in Forage-Fed Goats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1272835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, W.; Mao, S. Dynamic Changes in Rumen Fermentation and Bacterial Community Following Rumen Fluid Transplantation in a Sheep Model of Rumen Acidosis: Implications for Rumen Health in Ruminants. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 8453–8467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, G.; Loor, J.J.; Zhou, P.; Dong, X. Effects of Inoculation with Active Microorganisms Derived from Adult Goats on Growth Performance, Gut Microbiota and Serum Metabolome in Newborn Lambs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1128271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Ran, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, P.; Chen, J.; Loor, J.J.; et al. Inoculation of Newborn Lambs with Ruminal Solids Derived from Adult Goats Reprograms the Development of Gut Microbiota and Serum Metabolome and Favors Growth Performance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 983–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, H.J.; Bayer, E.A.; Rincon, M.T.; Lamed, R.; White, B.A. Polysaccharide Utilization by Gut Bacteria: Potential for New Insights from Genomic Analysis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Feng, Q.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Yang, F.; Zhou, J. Adding Rumen Microorganisms to Improve Fermentation Quality, Enzymatic Efficiency, and Microbial Communities of Hybrid Pennisetum Silage. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 410, 131272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oss, D.B.; Ribeiro, G.O.; Marcondes, M.I.; Yang, W.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Forster, R.J.; McAllister, T.A. Synergism of Cattle and Bison Inoculum on Ruminal Fermentation and Select Bacterial Communities in an Artificial Rumen (Rusitec) Fed a Barley Straw Based Diet. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.M.; Badhan, A.K.; Reid, I.D.; Ribeiro, G.; Gruninger, R.; Tsang, A.; Guan, L.L.; McAllister, T. Comparative Analysis of Functional Diversity of Rumen Microbiome in Bison and Beef Heifers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e01320-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.-B.; Li, W.-W.; Yu, H.-Q. Application of Rumen Microorganisms for Anaerobic Bioconversion of Lignocellulosic Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 128, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belanche, A.; Palma-Hidalgo, J.M.; Nejjam, I.; Jiménez, E.; Martín-García, A.I.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R. Inoculation with Rumen Fluid in Early Life as a Strategy to Optimize the Weaning Process in Intensive Dairy Goat Systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 5047–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huuki, H.; Tapio, M.; Mäntysaari, P.; Negussie, E.; Ahvenjärvi, S.; Vilkki, J.; Vanhatalo, A.; Tapio, I. Long-Term Effects of Early-Life Rumen Microbiota Modulation on Dairy Cow Production Performance and Methane Emissions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 983823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Peng, Y.-J.; Chen, Y.; Klinger, C.M.; Oba, M.; Liu, J.-X.; Guan, L.L. Assessment of Microbiome Changes after Rumen Transfaunation: Implications on Improving Feed Efficiency in Beef Cattle. Microbiome 2018, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, P.J.; Cox, M.S.; Vieira De Paula, T.; Lin, M.; Hall, M.B.; Suen, G. Transient Changes in Milk Production Efficiency and Bacterial Community Composition Resulting from Near-Total Exchange of Ruminal Contents between High- and Low-Efficiency Holstein Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 7165–7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimer, P.J.; Stevenson, D.M.; Mantovani, H.C.; Man, S.L.C. Host Specificity of the Ruminal Bacterial Community in the Dairy Cow Following Near-Total Exchange of Ruminal Contents. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 5902–5912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, M.A.; Penner, G.B.; Chaucheyras-Durand, F.; Guan, L.L. Development and Physiology of the Rumen and the Lower Gut: Targets for Improving Gut Health. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 4955–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Hidalgo, J.M.; Jiménez, E.; Popova, M.; Morgavi, D.P.; Martín-García, A.I.; Yáñez-Ruiz, D.R.; Belanche, A. Inoculation with Rumen Fluid in Early Life Accelerates the Rumen Microbial Development and Favours the Weaning Process in Goats. Anim. Microbiome 2021, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liang, S.; Choi, S.; Li, G. Effects of Maternal Rumen Microbiota on the Development of the Microbial Communities in the Gastrointestinal Tracts of Neonatal Sika Deer. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2025, 67, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, D.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Park, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Yu, Z. Repeated Inoculation of Young Calves With Rumen Microbiota Does Not Significantly Modulate the Rumen Prokaryotic Microbiota Consistently but Decreases Diarrhea. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ji, S.; Duan, C.; Ju, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, H.; Liu, Y. Rumen Fluid Transplantation Affects Growth Performance of Weaned Lambs by Altering Gastrointestinal Microbiota, Immune Function and Feed Digestibility. Animal 2021, 15, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Z.; Sun, H.X.; Li, G.D.; Liu, H.W.; Zhou, D.W. Effects of Inoculation with Rumen Fluid on Nutrient Digestibility, Growth Performance and Rumen Fermentation of Early Weaned Lambs. Livest. Sci. 2014, 162, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Qiao, Y.; Li, E.; Li, M.; Che, L. Interplay between Nutrition, Microbiota, and Immunity in Rotavirus Infection: Insights from Human and Animal Models. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1680448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, G.; Xing, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, M.; Huang, K.; Li, E.; Ma, X. Dietary Galacto-Oligosaccharides Enhance Growth Performance and Modulate Gut Microbiota in Weaned Piglets: A Sustainable Alternative to Antibiotics. Animals 2025, 15, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Horn, N.; Ajuwon, K.M. Mechanisms of Deoxynivalenol-Induced Endocytosis and Degradation of Tight Junction Proteins in Jejunal IPEC-J2 Cells Involve Selective Activation of the MAPK Pathways. Arch. Toxicol. 2021, 95, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.B.; Liu, P.; Huang, C.F.; Liu, L.; Li, E.K.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S. Effect of Wheat Bran on Apparent Total Tract Digestibility, Growth Performance, Fecal Microbiota and Their Metabolites in Growing Pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2018, 239, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).