1. Introduction

Actinomycetes are among the most biotechnologically valuable microorganisms, representing prolific producers of structurally diverse and biologically active secondary metabolites. They are responsible for more than two-thirds of naturally derived antibiotics, the majority of clinically important anticancer agents, immunomodulators, and cosmeceutical bioactives [

1,

2]. Within this prolific group, the genus

Kitasatospora—first described by Ōmura and Takahashi in 1982—has recently emerged as an underexplored lineage with considerable biosynthetic and ecological diversity due to its close phylogenetic relationship with

Streptomyces and comparable biosynthetic potential. Members of

Kitasatospora share morphological and chemotaxonomic characteristics with

Streptomyces but are distinguished by spore wall composition, 16S rRNA gene sequence,

gyrB signatures, high GC content, and complex secondary metabolic systems, reflecting an independent evolutionary trajectory [

3,

4,

5]. Importantly,

Kitasatospora species harbor distinct biosynthetic and regulatory systems that enable the production of chemically unique metabolites not found in

Streptomyces, underscoring their significance as an untapped reservoir of bioactive molecules [

6,

7].

Recent advances in genome sequencing and bioinformatics have revealed that

Kitasatospora genomes typically encode 25–40 biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) within 7–9 Mb high-GC genomes, including those for polyketide synthases (PKSs), nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), terpenes, and ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) [

7,

8,

9]. Recent reviews report over 100 identified metabolites—including macrolides, alkaloids, and peptide antibiotics—from

Kitasatospora species, highlighting their immense untapped potential for drug discovery and cosmetic applications [

9]. However, most BGCs remain transcriptionally silent under conventional laboratory conditions, forming a vast reservoir of cryptic or unexpressed metabolic potential. Consequently, activation strategies such as precursor-directed biosynthesis, co-cultivation induction, and fermentation parameter optimization have become essential tools in microbial natural product discovery, expanding the metabolic spectrum of actinomycetes and enabling targeted production of rare or novel metabolites with industrial, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic applications [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Among known species,

Kitasatospora griseola is one of the best-characterized members of the genus, originally isolated from soil and later distinguished from

Streptomyces based on morphological and chemotaxonomic analyses [

7]. Genomic and biochemical studies have revealed that

K. griseola produces diverse polyketide-type antibiotics and alkaloids, including bafilomycin, terpentecin, and satosporins A and B, which exhibit antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties [

14,

15]. Additionally, diterpene synthases such as CYC2 generate sclarene, biformene, and other novel bicyclic diterpenes, further demonstrating metabolic flexibility and pharmacological/cosmeceutical relevance [

9,

14]. Despite these findings, few studies have explored how environmental or nutritional factors regulate secondary metabolism in

K. griseola, yet understanding these influences is essential for optimizing fermentation-based metabolite production.

The discovery of novel

Kitasatospora strains from ecologically specialized environments has proven effective in unlocking new secondary metabolic diversity. Microorganisms inhabiting extreme or geochemically dynamic ecosystems frequently possess adaptive metabolic pathways that enable survival under nutrient-limited and high-stress conditions, often resulting in the production of structurally unique bioactive metabolites [

9,

13].

Jeju Island, a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site formed by volcanic activity, represents such a dynamic biosphere. In particular, Mulyeongari Oreum—a volcanic crater wetland within Mt. Halla National Park—features oligotrophic soil with high mineral content, strong ultraviolet exposure, and fluctuating hydrological conditions. These environmental pressures support highly adapted microbial communities, making this habitat a promising source of unexplored actinomycetes with distinctive biosynthetic potential [

16,

17].

During our ongoing screening for bioactive actinomycetes from Jeju’s volcanic regions, a filamentous strain designated JNUCC 62 was isolated from Mulyeongari Oreum. Phylogenetic analyses identified this strain as

Kitasatospora griseola, a genus known for its rich repertoire of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), including PKS, NRPS, terpene, and RiPP pathways [

18,

19,

20]. Despite this potential, many BGCs in

Kitasatospora remain poorly characterized or silent under standard laboratory conditions.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to perform integrated genomic and metabolomic characterization of K. griseola JNUCC 62 to explore its secondary metabolic capacity and identify BGC-associated metabolites with potential cosmeceutical relevance. We further employed a precursor-directed fermentation approach to investigate whether specific biosynthetic pathways could be selectively activated. The overall experimental workflow included strain isolation, genome sequencing and annotation, precursor-assisted fermentation, metabolite extraction and identification, and biological activity assessment.

This work aims to expand current knowledge of the metabolic potential of volcanic ecosystem-derived Kitasatospora strains and support the development of microbial natural products as promising functional ingredients for cosmetic and related applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Cultivation of the Strain

The actinobacterial strain JNUCC 62 (Mul-A1) was isolated from volcanic wetland soil collected at Mulyeongari Oreum, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea (33°20′ N, 126°37′ E). To selectively isolate rare actinomycetes, soil samples were serially diluted and plated onto Bennet’s agar (MBcell, Seoul, Republic of Korea) medium supplemented with cycloheximide (50 mg/mL in ethanol) and nalidixic acid (10 mg/mL in chloroform), both added at a 1:1000 dilution to inhibit fungal and Gram-negative bacterial growth.

Plates were incubated at 28 °C for seven days, and distinct filamentous colonies were repeatedly subcultured to obtain pure isolates. The purified isolate, designated Mul-A1, was preserved in 20% (v/v) glycerol at −80 °C and deposited in the Jeju National University Culture Collection (JNUCC) under the accession number JNUCC 62.

2.2. Genomic DNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Assembly

High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was extracted from a 5-day-old Bennet’s broth culture using a Qiagen Genomic-tip 100/G kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Whole-genome sequencing was conducted by CJ Bioscience Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea) using the PacBio Sequel I platform (Sequel_10K chemistry; Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA), producing a total coverage depth of 301.6×. De novo assembly was performed using HGAP 4 within SMRT Link v8.0 [

21], followed by sequence polishing with Arrow v2.3.3 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). The resulting draft genome comprised three contigs with a total size of 8,305,639 bp and a GC content of 72.8%. Genome annotation was conducted using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) [

22], and functional categorization of coding sequences (CDSs) was achieved with EggNOG-mapper v2.1.9 [

23].

2.3. Phylogenetic and Comparative Genomic Analyses

The 16S rRNA gene sequence was extracted from the assembled genome using Barrnap v0.9 [

24] and compared with reference sequences available in the EzBioCloud database for phylogenetic identification. Pairwise genomic similarity indices, including digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) and average nucleotide identity (ANI), were calculated using the Type (Strain) Genome Server (TYGS) [

25] and the OrthoANIu algorithm [

26], respectively. Functional clustering and orthologous group classification were performed using the COG database via EggNOG mapper [

23], and a circular genome map was generated with the CGView Server v2.0 [

27].

2.4. Genome Mining for Secondary Metabolite Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

To comprehensively investigate the biosynthetic capacity of K. griseola JNUCC 62, the complete assembled genome (8,305,639 bp; GC content 72.8%) was subjected to genome mining analysis using antiSMASH version 8.0. Prior to functional annotation, open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using Prodigal v2.6.3, which is integrated as the default gene-calling tool in the antiSMASH 8.0 pipeline, with default parameters to identify protein-coding regions in the assembled genome. The analysis was performed on the assembled FASTA file using default parameters, with advanced modules enabled, including KnownClusterBlast, ClusterFinder, SubClusterBlast, ActiveSiteFinder, and RiPP Recognition Element (RRE) Finder, to ensure the detection of canonical as well as cryptic biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs).

The analysis workflow consisted of multiple layers: (i) de novo identification of core biosynthetic enzymes such as polyketide synthases (PKS types I–III), nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS), terpene cyclases, lanthipeptide synthetases, and ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs); (ii) assignment of tailoring enzymes, regulators, and transporters; and (iii) detection of hybrid or modular clusters (e.g., PKS-NRPS, RiPP-PKS, or NRPS-RiPP systems) based on conserved domain architecture.

Each predicted BGC was annotated by cross-referencing the Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (MIBiG) version 3.0 database (European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Heidelberg, Germany) to identify sequence homology and structural similarity with previously characterized natural product clusters. Sequence alignments and similarity confidence levels were determined using BLASTP (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 11 August 2025) integrated within antiSMASH, and classification confidence was categorized as low, medium, or high according to antiSMASH scoring thresholds.

Predicted cluster boundaries were manually curated to verify open reading frame (ORF) integrity, GC bias, and syntenic organization using Geneious Prime 2024.1 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand). The overall biosynthetic landscape, including cluster density, domain arrangement, and functional distribution, was visualized using Circos software (v0.69, University of Toronto, Canada) and represented as a circular genome map integrating both coding and non-coding regions.

2.5. Purification and Structural Identification of Metabolites from JNUCC 62

The actinobacterial strain K. griseola JNUCC 62 (Mul-A1) was isolated from volcanic wetland soil at Mulyeongari Oreum and preserved in the Jeju National University Culture Collection (JNUCC). The strain was routinely maintained on Bennett’s agar at 28 °C.

For seed preparation, colonies were inoculated into YEME broth (yeast extract 4 g, malt extract 10 g, glucose 4 g/L; BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and shaken at 28 °C, 180 rpm for 3 days. A 2% (v/v) inoculum was transferred to GSS (MBcell, Seoul, Republic of Korea) production medium (soluble starch 10 g, glucose 20 g, soybean meal 25 g, beef extract 1 g, yeast extract 4 g, NaCl 2 g, K2HPO4 0.25 g, CaCO3 2 g/L; pH 7.2) and cultured at 28 °C for 5–7 days under aerobic conditions. To stimulate indole-derived secondary metabolite biosynthesis, a parallel fermentation was performed with 1% (w/v) L-tryptophan (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplementation. The combined culture volume reached 12 L.

After cultivation, whole culture broths (cells + supernatant) were extracted twice with equal volumes of ethyl acetate (EtOAc; Daejung Chemicals & Metals Co., Siheung, Republic of Korea). The EtOAc layers were collected, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate (Junsei Chemical Co., Tokyo, Japan), and concentrated under reduced pressure using a Rotavapor R-300 rotary evaporator (Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland). Each extract was dissolved in methanol and filtered through Whatman No. 1 paper (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) prior to purification. The EtOAc extract (0.6888 g) underwent stepwise chromatographic purification. First, methanolic Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) separated fractions based on UV absorption profiles. Active fractions were combined and further purified using silica gel 60 (0.040–0.063 mm; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) column chromatography with gradient methanol-chloroform (1:9 → 1:1,

v/

v). Final purification was achieved by reverse-phase HPLC on a Waters Alliance e2695 system equipped with a 2998 photodiode-array detector (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) operated for 60 min under the conditions summarized in

Table 1. Purified metabolites were evaporated to dryness under vacuum and stored at 4 °C until analysis.

Structural elucidation of the isolated compounds was carried out by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy using JNM-LA 400 and JNM-ECX 400 FT-NMR instruments (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with deuterated solvents (CDCl3 and DMSO-d6; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Tewksbury, MA, USA). Chemical shifts (δ) were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS). UV-visible spectra were obtained with a Shimadzu UV-1900 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan).

2.6. Preparation of the Ethyl Acetate Extract for Bioactivity Evaluation

The actinobacterial strain K. griseola JNUCC 62 was cultured on Bennet’s agar at 28 °C for 7 days and subsequently inoculated into Bennet’s broth for liquid fermentation at 28 °C with agitation at 150 rpm for 7 days. The culture broth (3 L) was centrifuged (8000× g, 20 min, 4 °C) to separate the supernatant, which was extracted three times with an equal volume of ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The combined EtOAc layers were concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (Eyela N-1000, Tokyo, Japan) to yield the crude ethyl acetate extract (JNUCC62 EA), which was stored at −20 °C until use. For all bioassays, the extract was dissolved in DMSO, and the final DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.1% (v/v).

2.7. Cell Culture and Cell Viability Assay

Murine macrophage RAW 264.7 and murine melanoma B16F10 cells were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB, Seoul, Republic of Korea). RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, while B16F10 cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS under 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Cell viability was assessed by the MTT assay. Cells (1 × 10

5 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with JNUCC62 EA (6.25–100 µg/mL) for 24 h. After incubation, 10 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added, followed by 4 h incubation. The medium was removed, and the formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µL DMSO. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm.

2.8. ABTS Radical Scavenging Assay

The antioxidant activity of JNUCC62 EA was evaluated by the ABTS•⁺ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) radical cation decolorization method [

28]. Briefly, the ABTS•⁺ solution was prepared by mixing 7 mM ABTS and 2.45 mM potassium persulfate and allowing the mixture to stand in the dark at room temperature for 16 h. The ABTS•⁺ solution was then diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) to obtain an absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. To each 190 µL of ABTS•⁺ solution, 10 µL of extract sample (12.5–500 µg/mL) was added, incubated for 6 min at room temperature, and absorbance was measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Ascorbic acid served as a positive control.

2.9. Tyrosinase Inhibition Assay

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity was determined spectrophotometrically using L-DOPA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as substrate. Briefly, 80 µL of 1 mM L-DOPA in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), 40 µL of JNUCC62 EA (12.5–200 µg/mL), and 40 µL of mushroom tyrosinase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, 250 U/mL) were mixed in a 96-well plate. The reaction mixture was incubated for 15 min at 37 °C, and absorbance was read at 475 nm. Arbutin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, 300 µM) was used as a reference inhibitor.

2.10. Determination of Nitric Oxide Production

RAW 264.7 cells were pre-treated with JNUCC62 EA (6.25–100 µg/mL) for 1 h and stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 1 µg/mL) for 24 h. The culture supernatant (100 µL) was mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), incubated for 10 min at room temperature, and absorbance was measured at 540 nm. Sodium nitrite was used as a standard to calculate NO concentration.

2.11. Cytokine Quantification by ELISA

The levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) in RAW 264.7 culture supernatants were measured using commercial ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical density was read at 450 nm, and concentrations were determined using standard curves.

2.12. Melanin Content and Intracellular Tyrosinase Activity

B16F10 cells were pre-treated with α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH, 200 nM) for 24 h to stimulate melanogenesis and then incubated with JNUCC62 EA (6.25–50 µg/mL) for another 48 h. Cells were lysed in 1 N NaOH (containing 10% DMSO) at 60 °C for 1 h, and absorbance was measured at 405 nm to quantify melanin. For intracellular tyrosinase activity, cell lysates were incubated with L-DOPA (1 mM, 37 °C, 1 h), and absorbance was measured at 475 nm. Arbutin (300 µM) served as a positive control.

2.13. Skin Irritation Assessment of the Ethyl Acetate Extract from JNUCC 62

A primary human skin irritation test for the ethyl acetate extract of

K. griseola JNUCC 62 (JNUCC62 EA) was performed by Dermapro Co., Ltd. (Seoul, Republic of Korea) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Personal Care Products Council (PCPC) Guidelines for cosmetic safety evaluation [

29]. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Dermapro (IRB No. 1-220777-A-N-01-B-DICN25194). All participants provided written informed consent before inclusion.

Healthy Korean adults between 19 and 60 years of age with no dermatological disorders, chronic skin conditions, or hypersensitivity were enrolled following screening. Of 31 initially recruited subjects, 30 participants (29 female, 1 male; mean age 49.3 ± 5.2 years, range 34–58 years) completed the study. Most volunteers exhibited normal-to-dry skin and had no prior history of irritation or allergy.

Two ethyl acetate extracts of K. griseola JNUCC 62, designated JNUCC62 EA-25 and JNUCC62 EA-50, were prepared at concentrations of 25 µg/mL and 50 µg/mL, respectively, by Jeju National University. These extracts were obtained as liquid formulations specifically designed for bioactivity evaluation, including anti-inflammatory and skin safety assays. All samples were stored at 4 °C in amber vials to prevent light degradation and were applied directly to the test systems without further dilution. Each test material (20 µL) was applied to the upper back using Van der Bend chambers (Van der Bend Laboratory Products B.V., Brielle, The Netherlands) fixed with Micropore™ tape (3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN, USA). Before application, the skin was cleansed with 70% ethanol.

Patches were occluded for 24 h, removed, and the sites were examined for erythema and edema 20 min post-removal (first reading) and again 24 h later (second reading) under standardized illumination and temperature. Skin reactions were graded on a five-point PCPC scale:

+1 = slight erythema; +2 = moderate erythema ± barely perceptible edema; +3 = moderate erythema with generalized edema; +4 = severe erythema and edema ± vesicles; +5 = severe reaction beyond patch area (considered allergic rather than irritant).

The mean irritation response (R) for each test material was calculated using the following equation:

where

n represents the total number of subjects.

The irritation level was classified according to the PCPC criteria as follows:

None to Slight (0.00 ≤ R < 0.87); Mild (0.87 ≤ R < 2.42); Moderate (2.42 ≤ R < 3.44); and Severe (R ≥ 3.44).

All skin reactions were independently evaluated by a board-certified dermatologist under standardized lighting conditions, and any local or systemic adverse events were carefully documented throughout the study period.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test in GraphPad Prism version 10.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. General Genome Features

The draft genome of

K. griseola JNUCC 62 consisted of three contigs totaling 8,305,639 bp with a mean GC content of 72.8% (

Table 1). The largest contig (8,235,469 bp) represented nearly the entire chromosome, whereas the remaining two contigs measured 62,082 bp and 8088 bp, with GC contents of 71.07% and 62.48%, respectively.

To evaluate whether these two small contigs might represent plasmids, we examined them for plasmid-related replication or partitioning genes (e.g., rep, par, tra, mob), circularization signatures, and ori-associated motifs. However, no plasmid-specific structural or functional features were detected, and their GC characteristics were highly similar to chromosomal coding patterns. Therefore, the two contigs were considered unresolved chromosomal fragments rather than extrachromosomal replicons.

The genome contained 7265 coding sequences (CDSs), with an average CDS length of 997 ± 900 bp, 34 rRNA genes, and 72 tRNA genes. The mean intergenic region was 159.7 ± 172.3 bp, and bacterial core gene coverage reached 100%, indicating a high-quality, nearly complete chromosomal assembly. The circular genome map (

Figure 1) illustrates the GC content and gene density typical of high-GC actinomycete.

3.2. 16S rRNA Gene-Based Phylogenetic Identification

The nearly complete 16S rRNA gene (1475 bp) of strain JNUCC 62 showed 99.8% sequence similarity to

K. griseola JCM 3339ᵀ (NR_044809.1), followed by

K. paracochleata (99.39%),

K. phosalacinea (99.39%), and

K. cineracea (98.55%) (

Table 2). This high degree of similarity clearly placed JNUCC 62 within the

K. griseola clade, consistent with its morphological and genomic characteristics typical of the genus

Kitasatospora.

3.3. Comparative Genomics and Genome Relatedness

Genome-based similarity analyses supported the taxonomic assignment of strain JNUCC 62 to K. griseola. The OrthoANIu value between JNUCC 62 and K. griseola JCM 3339ᵀ was 97.46%, exceeding the species boundary threshold (95–96%).

The average aligned length was 5,208,297 bp, corresponding to approximately 63% genome coverage for both strains (

Table 3). In parallel, the dDDH (d

0) value was 84.4% (95% CI: 80.6–87.6), with a negligible GC content difference (0.02%), confirming species-level congruence. All other Kitasatospora type strains exhibited much lower dDDH values (<55%), including

K. cheerisanensis (53%) and

K. fiedleri (36.4%), indicating that JNUCC 62 is a conspecific isolate of

K. griseola adapted to Jeju’s volcanic soil ecosystem (

Table 4).

3.4. Functional Gene Categorization

Functional classification based on COG analysis revealed that approximately 2700 genes (≈37%) were assigned to Category S (function unknown) (

Figure 2). Among the an-notated genes, the most abundant categories were related to amino acid transport and metabolism (E), transcriptional regulation (K), carbohydrate transport and metabolism (G), energy production and conversion (C), and inorganic ion transport and metabolism (P). This functional composition highlights the strain’s robust primary metabolic potential, supporting its adaptation to nutrient-limited volcanic environments. The predominance of metabolism- and regulation-related genes is consistent with the metabolic versatility and secondary metabolite potential characteristic of the genus

Kitasatospora.

3.5. Phylogenomic Tree Analysis

To further confirm the phylogenetic placement of strain JNUCC 62, a Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny (GBDP) tree was generated using the TYGS platform [

25]. The tree was inferred from pairwise genome distances (d

4 formula) with 100 bootstrap replicates, and only nodes with >50% support are shown. As illustrated in

Figure 3, JNUCC 62 clustered tightly with

K. griseola JCM 3339ᵀ with a bootstrap value of 100%, forming a distinct lineage separated from closely related taxa such as

K. cheerisanensis KCTC 2395ᵀ,

K. fiedleri DSM 113496, and

K. cineracea DSM 44780. This phylogenomic topology is fully consistent with the ANI (97.46%) and dDDH (84.4%) results, confirming that strain JNUCC 62 belongs to

K. griseola. Furthermore, the high 16S rRNA sequence similarity to the type strain

K. griseola JCM 3339ᵀ (

Table 2) supports the concordant taxonomic placement inferred from genome-based phylogeny. Additionally, species such as

K. paracochleata DSM 41656 and

K. setae NRRL B-16185 formed well-supported independent branches, reflecting the genomic diversity within the genus (

Figure 3). Collectively, these results demonstrate that

K. griseola JNUCC 62 represents a geographically distinct conspecific lineage adapted to the volcanic wetland environment of Jeju Island.

3.6. Purification and Structural Identification of Metabolites

Cultivation of K. griseola JNUCC 62 under both standard and tryptophan-enriched conditions yielded ethyl acetate extracts with distinct chemical profiles, indicating metabolic diversification. The tryptophan-supplemented culture produced a substantially higher extract mass (0.6888 g) than the control culture (0.2250 g), suggesting that the exogenous amino acid served as a biosynthetic enhancer for indole alkaloid formation. Chromatographic fractionation of the crude extracts using Sephadex LH-20 and silica gel columns produced multiple fractions exhibiting distinct UV absorbance patterns, consistent with the presence of diverse secondary metabolites.

Further purification by reverse-phase HPLC resulted in the isolation of four pure compounds (

1–

4), which were structurally elucidated through combined spectroscopic and chromatographic analyses, including UV-visible and NMR spectroscopy. These compounds were identified as 1-acetyl-β-carboline, perlolyrine, tryptopol, and 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid (

Figure 4;

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8). Compounds

1–

3 were exclusively detected in the tryptophan-fed culture, whereas compound

4 was obtained from the non-supplemented culture, supporting a precursor-directed metabolic shift. Their UV absorption maxima were 275, 283, 281, and 265 nm, respectively, and the NMR spectral data matched those reported in previous literature, confirming structural identity.

HPLC profiling provided further evidence of precursor-dependent biosynthetic modulation (

Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). In the tryptophan-supplemented culture, four distinct peaks were detected between 275 and 283 nm, corresponding to indole-derived β-carboline metabolites (

1–

3). Conversely, the control culture lacking tryptophan supplementation exhibited a single peak at 265 nm, corresponding to the pyrrole compound (

4). These chromatographic profiles confirm that L-tryptophan acts as a direct biosynthetic precursor, selectively channeling the secondary metabolism of

K. griseola JNUCC 62 toward β-carboline alkaloid biosynthesis.

Collectively, the selective production of β-carboline and pyrrole derivatives under different culture conditions demonstrates a precursor-dependent activation of secondary metabolism, in which amino acid supplementation promotes the synthesis of specialized metabolites. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first identification of these bioactive indole and pyrrole alkaloids from a volcanic soil-derived Kitasatospora strain isolated from Jeju Island.

3.7. Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Diversity in K. griseola JNUCC 62

Genome mining analysis using antiSMASH version 8.0 revealed that

K. griseola JNUCC 62 harbors an exceptionally rich secondary metabolic capacity, with a total of 30 biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) distributed across its 8.3 Mb high-GC genome (

Table 9). These clusters encompass a wide range of biosynthetic systems, including terpene (6 clusters), polyketide (8 clusters), nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS, 7 clusters), RiPP/lanthipeptide (5 clusters), and several hybrid PKS–NRPS or RiPP–PKS architectures, reflecting the strain’s remarkable chemical versatility. The total BGC content accounts for approximately 18.6% of the genome, underscoring the strong secondary metabolite-producing potential characteristic of actinomycetes. Several gene clusters exhibited high sequence similarity (> 70%) to experimentally validated biosynthetic pathways in the MIBiG database, while many others represented novel or cryptic clusters lacking close homologs, suggesting unexplored biosynthetic diversity.

Among the predicted clusters, terpene-related regions (1, 2, 10, and 26) were predicted to encode geosmin and hopene synthases, compounds responsible for earthy odor and antimicrobial activity. Type I PKS and hybrid PKS-NRPS clusters (Regions 5, 8, 19, 23, and 30) showed strong similarity to known macrolide and polyether scaffolds such as formicamycins A–M, leinaimycin, and tambjamine BE-18591, indicating their potential for polyketide-derived antibiotic biosynthesis. NRPS and NRPS-like clusters (Regions 7, 11, and 20) encoded predicted lankacidin-like and arylpolyene biosynthetic systems that are typically associated with pigment formation and redox-active metabolites. Additionally, RiPP and lanthipeptide clusters (Regions 6, 17, 21, and 22) contained homologs of LL-D49194d (LLD) and class IV lanthipeptide/SIA gene families, suggesting the ability to synthesize antibacterial peptides. Notably, Regions 9 and 10 encoded a nonribosomal peptide synthetase-aminocarboxylic acid hybrid module (EDHA) corresponding to an NAPA-NRPS pathway, consistent with the biosynthesis of indole-derived alkaloids such as β-carbolines, which were experimentally confirmed in JNUCC62 ethyl acetate extracts.

Overall, approximately 20% (6 clusters) of the detected BGCs exhibited high similarity (>80%) to known reference clusters, whereas the majority (24 clusters) displayed low or no similarity, implying the presence of unique metabolic pathways possibly influenced by the distinct environmental characteristics of Jeju Island. Comparative genomic–metabolomic analysis demonstrated a strong correlation between predicted clusters and isolated compounds: the β-carboline alkaloids (1-acetyl-β-carboline, perlolyrine, and tryptopol) were likely derived from NRPS-PKS hybrid clusters (Regions 8 and 10), while the biosynthesis of 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid corresponded to the arylpolyene/thiourea-associated cluster (Region 13). These findings support the hypothesis that K. griseola JNUCC 62 expresses a versatile repertoire of silent or inducible BGCs, particularly under tryptophan-enriched fermentation conditions.

Collectively, the results demonstrate that K. griseola JNUCC 62 harbors a complex and cryptic secondary metabolome that integrates multiple biosynthetic systems and regulatory pathways. This genomic configuration provides a strong foundation for future activation and heterologous expression studies aimed at uncovering novel indole-derived or peptide-based natural products with potential cosmeceutical and pharmaceutical applications.

3.8. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

The antioxidant potential of the ethyl acetate extract of

K.

griseola JNUCC 62 (JNUCC62 EA) was determined by the ABTS•⁺ radical scavenging assay. The extract exhibited a concentration-dependent radical scavenging effect (

Figure 5). At 500 μg/mL, JNUCC62 EA showed 99.31 ± 0.00% inhibition, comparable to the positive control ascorbic acid (100.05 ± 0.09%) at 25 μg/mL. The calculated IC

50 value for JNUCC62 EA was 116.10 ± 6.92 μg/mL, whereas that of ascorbic acid was 3.85 ± 0.04 μg/mL. These results indicate that the extract possesses moderate free radical scavenging capacity, suggesting the presence of redox-active secondary metabolites.

3.9. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

The anti-inflammatory potential of the ethyl acetate extract of

K.

griseola JNUCC 62 (JNUCC62 EA) was evaluated in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. As shown in

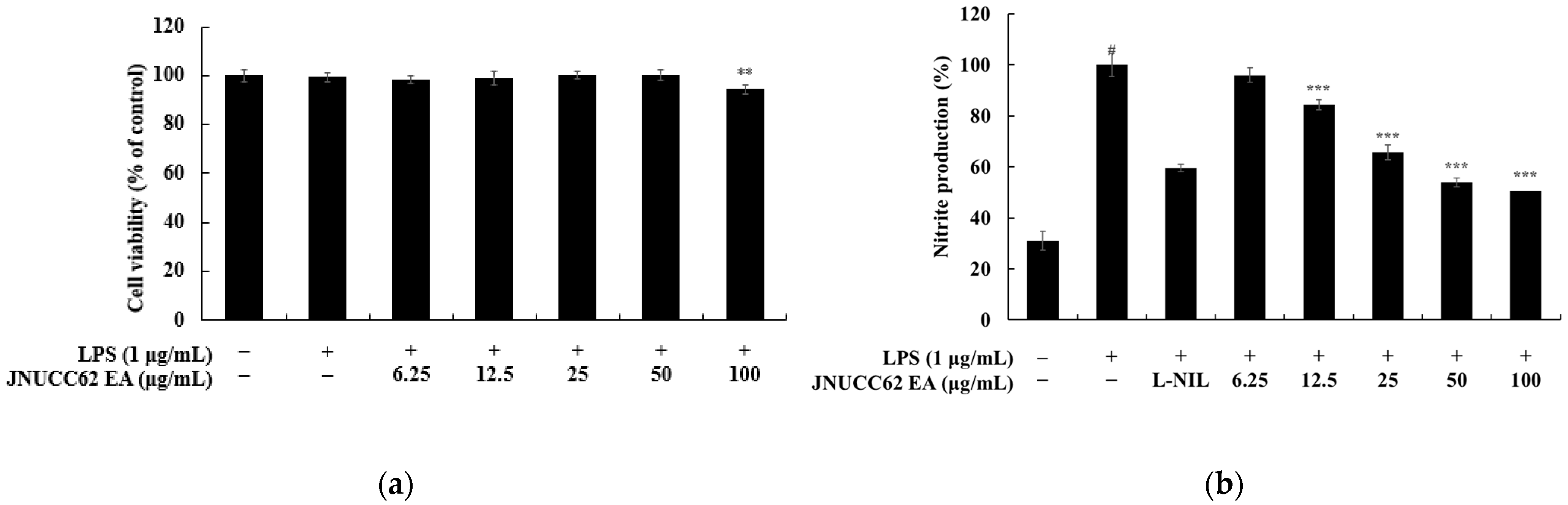

Figure 6, treatment with JNUCC62 EA (6.25–100 μg/mL) markedly and dose-dependently reduced nitric oxide (NO) production without inducing cytotoxicity. At 100 μg/mL, NO levels decreased to 31.09 ± 3.69% of the LPS-treated control, comparable to the inhibitory effect of the positive control L-NIL (40 μM), while cell viability remained above 98% at all tested concentrations. These findings demonstrate that JNUCC62 EA effectively suppresses LPS-induced NO synthesis, presumably through the inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity.

To further confirm its anti-inflammatory efficacy, the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in the culture supernatant were quantified by ELISA (

Figure 7). JNUCC62 EA significantly inhibited cytokine secretion in a concentration-dependent manner, reducing IL-6 to 65.32 ± 6.16%, IL-1β to 82.91 ± 0.43%, and TNF-α to 35.12 ± 0.93% relative to the LPS-stimulated control group (

p < 0.001). These consistent reductions in both NO and cytokine levels indicate that JNUCC62 EA exerts strong anti-inflammatory activity by downregulating key inflammatory mediators involved in macrophage activation.

Taken together, these results indicate that the extract effectively alleviates LPS-induced inflammation by reducing NO and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, suggesting potential involvement of inflammatory signaling pathways. However, further mechanistic studies are needed to clarify the precise intracellular targets, supporting its potential as a microbial-derived anti-inflammatory ingredient for cosmeceutical applications.

3.10. Anti-Melanogenic Activity

The potential cytotoxicity and anti-melanogenic effects of the ethyl acetate extract of Kitasatospora griseola JNUCC 62 (JNUCC62 EA) were evaluated in α-MSH-stimulated B16F10 melanoma cells. As shown in

Figure 8a, JNUCC62 EA exhibited no significant cytotoxicity up to 100 μg/mL, maintaining more than 95% cell viability, thereby confirming its suitability for melanogenesis-related assays.

Upon α-MSH stimulation, treatment with JNUCC62 EA significantly reduced intracellular melanin accumulation in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 8b). At a concentration of 25 μg/mL, the melanin content decreased to 61.49 ± 1.24% relative to the α-MSH-treated control (100%), demonstrating stronger depigmenting activity than the reference compound arbutin (300 μM).

Consistent with these findings, intracellular tyrosinase activity was also markedly suppressed by JNUCC62 EA (

Figure 8c). At 25 μg/mL, the extract inhibited cellular tyrosinase activity to 24.32 ± 0.31% of the control (

p < 0.001), confirming that JNUCC62 EA effectively interferes with melanin biosynthesis.

Collectively, these results indicate that JNUCC62 EA exerts potent melanogenesis-inhibitory activity without cytotoxicity, likely through the downregulation of tyrosinase activity and melanin synthesis pathways.

3.11. Dermal Safety Evaluation of K. griseola JNUCC 62

A total of 30 healthy volunteers (29 females and 1 male; 96.7% female) successfully completed the human primary skin irritation test of the ethyl acetate extract of K. griseola JNUCC 62 (JNUCC62 EA). The participants represented a range of skin types, including dry (23.3%), normal (60.0%), and dry–oily combination (16.7%), and none reported any prior history of cutaneous irritation or allergic sensitivity. Following 24 h occlusive patch application, neither JNUCC62 EA-25 (25 µg/mL) nor JNUCC62 EA-50 (50 µg/mL) induced any visible signs of erythema, edema, papules, or vesiculation at either the first (20 min post-removal) or second (24 h post-removal) observation point.

All participants exhibited normal skin conditions without subjective symptoms such as itching, burning, or stinging. The mean response value (R) for both formulations was 0.0, corresponding to the “None to Slight” irritation category under the PCPC (2014) classification (

Table 10). No local or systemic adverse effects were observed during or after the test period, and no participant required medical intervention or discontinued due to adverse reactions.

Collectively, these results confirm that JNUCC62 EA caused no primary irritation on human skin, even at concentrations up to 50 µg/mL. Accordingly, the extract was classified as a non-irritant material under both PCPC (2014) and Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) guidelines, demonstrating excellent dermal tolerability and safety suitable for use in cosmetic and cosmeceutical formulations.

4. Discussion

This study presents the first integrated genomic and metabolomic characterization of

Kitasatospora griseola JNUCC 62, an actinobacterial strain isolated from the volcanic wetland soil of Mulyeongari Oreum, Jeju Island, and evaluates its cosmeceutical potential [

1,

30]. The unique geochemical environment of Mulyeongari Oreum—a volcanic crater wetland within Mt. Halla National Park, characterized by oligotrophic conditions, low nutrient availability, and high mineral content—creates selective pressures that promote the evolution of microorganisms with exceptional biosynthetic capacities [

16,

17]. Actinomycetes from such volcanic habitats are expected to harbor genetically diverse biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) and produce structurally unique, bioactive metabolites [

18,

19,

20]. The findings of this study strongly support this hypothesis.

Genomic sequencing revealed a complete genome of 8.31 Mb with a GC content of 72.8% and 7265 coding sequences (CDSs) [

21]. Comparative genomic indices, including ANI 97.46% and dDDH 84.4%, confirmed a conspecific relationship with the type strain K. griseola JCM 3339ᵀ [

25]. Genome mining using antiSMASH 8.0 identified 30 BGCs, accounting for 18.6% of the genome, including PKS, NRPS, RiPP/lanthipeptide, terpene, and hybrid types [

30]. Several BGCs showed high homology to known clusters for formicamycin [

6], lankacidin, and lanthipeptide-type compounds, while others were novel or cryptic, possibly reflecting the unique ecological characteristics of its volcanic wetland isolation source. This BGC richness aligns with the general metabolic potential of Actinomycetales [

1,

2] and underscores the independent evolutionary trajectory of

Kitasatospora relative to

Streptomyces, as evidenced by distinct spore wall composition, 16S rRNA,

gyrB signatures, and complex secondary metabolic systems [

3,

4,

5].

In comparison with other

Kitasatospora genomes analyzed by Li et al. [

7], conserved PKS, NRPS, and terpene clusters were also observed in JNUCC 62, demonstrating shared ancestral biosynthetic traits within the genus. However, our antiSMASH results revealed that a substantial proportion of the 30 BGCs identified in JNUCC 62 showed low or no similarity to the representative clusters summarized by Li et al., suggesting substantial strain-specific biosynthetic expansion. Notably, several cryptic clusters (e.g., Regions 7, 11, 20, 24–30) lacked close homologs in both

Kitasatospora and

Streptomyces genomes, supporting the presence of unexplored metabolic pathways unique to this strain.

Furthermore, whereas Li et al. provided comparative genomic predictions of biosynthetic potential across the genus, the present study experimentally validated the production of indole-derived β-carboline and pyrrole compounds and established genome-to-metabolite correlations for specific hybrid NRPS–PKS and arylpolyene clusters. This functional confirmation represents a significant advancement beyond existing comparative genomic studies.

Under conventional laboratory conditions, most BGCs remain transcriptionally silent [

6,

7,

10,

11,

12,

13]. To selectively activate specific pathways, we employed precursor-directed fermentation by supplementing L-tryptophan, a biosynthetic substrate that directly feeds into indole metabolism. This targeted approach was selected because genome mining revealed multiple NRPS–PKS hybrid clusters containing tryptophan-utilizing domains, suggesting greater inducibility of indole-derived pathways compared with others.

Ethyl acetate extracts from tryptophan-supplemented cultures produced four metabolites—1-acetyl-β-carboline, perlolyrine, tryptopol, and 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid—structurally consistent with the predicted NRPS–PKS and arylpolyene BGCs. HPLC analysis demonstrated significant induction of β-carboline biosynthesis upon precursor addition, while pyrrole metabolites predominated under non-supplemented conditions, indicating differential pathway activation.

Although direct experimental evidence linking indole metabolism to volcanic environmental adaptation is currently limited, the ability of K. griseola JNUCC 62 to produce structurally unique indole-derived metabolites highlights an underexplored metabolic potential that may be shaped by its volcanic wetland origin. We acknowledge this as a hypothesis requiring further ecological and regulatory validation in future studies.

In contrast to the well-known polyketide and diterpene compounds previously reported from

Kitasatospora, such as satosporins and sclarene derivatives with primarily antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory activities [

14,

15], the β-carboline and pyrrole metabolites identified in this study constitute a distinctive class of indole-derived small molecules. These compounds exhibited multifunctional cosmeceutical activities—antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-melanogenic—simultaneously in the absence of cytotoxicity, expanding the recognized chemical and functional spectrum of the genus. Their strong redox-modulating properties further support the hypothesis that adaptation to the volcanic wetland environment enriched biosynthetic pathways for skin health–related bioactivities.

The ethyl acetate extract (JNUCC62 EA) exhibited multifunctional bioactivity suitable for cosmeceutical applications. It displayed strong antioxidant capacity in the ABTS assay (IC

50 ≈ 116 μg/mL) [

28], anti-inflammatory activity via inhibition of nitric oxide (31.09 ± 3.69% of control) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α) in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages, and anti-melanogenic effects in α-MSH-stimulated B16F10 melanoma cells, reducing melanin content to 61.49 ± 1.24% and tyrosinase activity to 24.32 ± 0.31% of control, without cytotoxicity. A human primary skin irritation test confirmed no irritation (R = 0.0) up to 50 µg/mL, establishing excellent dermal safety [

29]. These triple functionalities—antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and whitening—are consistent with the broad redox and inflammatory signaling modulation properties of β-carboline/indole-pyrrole scaffolds and are supported by COG classification showing enrichment in metabolism and transcription-related categories [

27].

Given the demonstrated safety profile and biological efficacy, JNUCC62 EA or its purified metabolites may be effectively formulated into topical cosmetic products such as brightening serums, essences, lotions, and sheet masks targeting hyperpigmentation and sensitive-skin inflammation. Moreover, precursor-assisted fermentation offers a practical and scalable production strategy that aligns with cosmetic ingredient manufacturing practices.

Compared with previous studies on

Kitasatospora, which mainly reported polyketides (e.g., satosporins A/B) [

14] and diterpenes (e.g., sclarene from CYC2) [

15], the discovery of indole-derived alkaloids from a volcanic soil-derived strain represents a significant advancement. The synergistic efficacy of these metabolites, combined with genomic evidence of diverse redox enzymes and regulators, positions JNUCC 62 as a promising source of safe, multifunctional cosmeceutical ingredients [

9].

Despite these findings, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, genome assembly remains at the draft level with three contigs [

21], limiting definitive conclusions about chromosomal architecture (e.g., linear vs. circular, repeat regions). Second, BGC-metabolite linkages rely on predictive correlations and lack genetic validation (e.g., gene knockout/overexpression or heterologous expression). Third, bioactivity assessments are confined to in vitro cell-based models and limited human patch testing, excluding long-term exposure, phototoxicity, or sensitization endpoints critical for cosmetic compliance. Fourth, only four metabolites were isolated, while most of the 30 BGCs remain silent [

31,

32].

Future studies should adopt a multi-omics, mechanism-driven, and industry-aligned roadmap to fully unlock the biosynthetic and application potential of

K.

griseola JNUCC 62. This includes constructing expression maps through integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses to quantitatively determine how specific culture variables—such as precursor type and dose, dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, trace elements, and co-cultivation—selectively activate individual biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) [

33,

34]. Targeted activation of silent clusters should be pursued using CRISPRi/CRISPRa systems and transcription factor engineering [

35,

36,

37]. Metabolic flux analysis combined with stable isotope labeling (e.g.,

13C-tryptophan) will be essential to trace the biosynthetic origins of β-carboline and pyrrole derivatives. Molecular mechanisms underlying melanogenesis (via the NRF2-MITF-TYR axis) and inflammation (via iNOS/NF-κB and MAPK pathways) must be elucidated at the signaling level. To advance toward cosmeceutical commercialization, human repeat insult patch testing (HRIPT), formulation stability studies (assessing light, oxidation, and pH effects), and raw material standardization (including marker compound quantification, residual solvent limits, and microbial safety thresholds) are required to meet regulatory and industrial standards [

38,

39,

40].

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that

K. griseola JNUCC 62 from Jeju’s volcanic wetland is a genomically rich, metabolically versatile actinomycete capable of producing novel indole alkaloids with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and whitening properties and proven dermal safety. The integrated approach—genomics, precursor-directed fermentation, metabolite isolation, bioactivity screening, and safety validation—establishes a robust framework for developing safe, multifunctional cosmeceutical ingredients. This work underscores the immense value of volcanic wetland-derived actinomycetes as an innovative natural product library for the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries, while advocating a sustainable model that balances biodiversity conservation with industrial exploitation [

2,

9].