Abstract

This study evaluated the seasonal greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and carbon assimilation of Bambusa edulis under four soil amendment treatments—control (C), biochar (B), fertilizer using vermicompost (F), and biochar plus fertilizer (B + F)—in a coastal shelterbelt system in south-western Taiwan. Over a 12-month period, CO2 and N2O fluxes and photosynthetic carbon uptake were measured. The control (C) treatment served as the baseline, exhibiting the lowest greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and carbon assimilation. Its summer N2O emissions were 39.54 ± 20.79 g CO2 e m−2, and its spring carbon assimilation was 13.2 ± 0.84 kg CO2 clump−1. In comparison, the amendment treatments significantly enhanced both emissions and carbon uptake. The fertilizer-only (F) treatment resulted in the highest levels, with peak summer N2O emissions increasing by 306.5% (to 160.73 ± 96.22 g CO2 e m−2) and spring carbon assimilation increasing by 40.2% (to 18.5 ± 0.62 kg CO2 clump−1). An increase in these values was also observed in the combined biochar and fertilizer (B + F) treatment, although the magnitude was less than that of the F treatment alone. In the B + F treatment, summer N2O emissions increased by 130.3% (to 91.1 ± 62.51 g CO2 e m−2), while spring carbon assimilation increased by 17.4% (to 15.5 ± 0.36 kg CO2 clump−1). Soil CO2 flux was significantly correlated with atmosphere temperature (r = 0.63, p < 0.01) and rainfall (r = 0.45, p < 0.05), while N2O flux had a strong positive correlation with rainfall (r = 0.71, p < 0.001). The findings highlight a trade-off between nutrient-driven productivity and GHG intensity and demonstrate that optimized organic and biochar applications can enhance photosynthetic carbon gain while mitigating emissions. The results support bamboo’s role in climate mitigation and carbon offset strategies within nature-based solution frameworks.

1. Introduction

The Paris Agreement’s 2050 net-zero goal has accelerated mitigation strategies that combine technological decarbonization with carbon sequestration and nature-based solutions (NbS) [1,2]. NbS—such as reforestation, peatland rehabilitation, and blue carbon restoration—are increasingly embedded in national and corporate strategies, supported by frameworks like the Science-Based Targets initiative and the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures [3,4]. Among land-based ecosystems, bamboo has emerged as a promising candidate for rapid and scalable carbon sequestration. Characterized by its fast growth cycle and high biomass accumulation, managed bamboo plantations—especially in subtropical Asia—have been reported to sequester carbon at rates 2–4 times greater than conventional conifer forests [5,6]. Recent studies have emphasized the role of carbon-based soil amendments in enhancing soil quality and contributing to climate mitigation. For instance, Adekiya et al. [7] demonstrated that the application of biochar and plant residues significantly increased soil organic carbon stocks while maintaining crop productivity in subtropical agricultural systems. In Taiwan, both native and naturalized bamboo species such as Bambusa edulis are widely integrated into agroforestry systems and windbreak plantations. However, extrapolating these known effects to coastal saline–alkaline environments remains problematic due to the unique microbial and physiological stresses present in these systems. There is a critical lack of empirical data on how biochar and organic fertilizers interact to influence the carbon trade-off—balancing photosynthetic gain against respiratory losses—specifically within bamboo shelterbelts for a critical challenge lies in the carbon trade-off mechanism. While organic fertilizers are essential for overcoming nutrient limitations and maximizing photosynthetic carbon assimilation in bamboo, they typically elevate the risk of N2O emissions through accelerated microbial nitrogen transformations. This creates a conflict between maximizing carbon uptake and minimizing soil emissions. Theoretically, biochar amendment can resolve this conflict by interacting with soil chemistry—specifically by adsorbing labile nitrogen and improving soil aeration. This suggests a potential conceptual framework where biochar acts to decouple agronomic productivity from emission intensity, particularly in saline environments where soil structure is often compromised. This study bridges this gap by using fertilizer and biochar application trials to monitor the dynamic state of greenhouse gas emissions in the field.

Bambusa edulis (Odashima) Keng is a widely cultivated species in western Taiwan, primarily grown for its edible shoots. Beyond its agricultural value, this species also serves ecological functions such as mitigating wind damage and stabilizing soils. Its vigorous rhizome system and rapid regrowth capability indicate significant potential for above- and belowground carbon accumulation. Field-based evaluations are increasingly recognized as essential to quantify the species’ carbon sequestration capacity, particularly under varying soil nutrient and moisture regimes [8,9]. To enhance both plant productivity and soil fertility, farmers often apply organic soil amendments like compost and biochar. Biochar—a stable, carbon-rich material produced through pyrolysis of organic matter in low-oxygen environments—is notable for its high porosity, chemical stability, and long-term carbon persistence [10]. Incorporation of biochar into soil has been shown to improve physical properties such as aggregation and water retention [11], while also contributing to the long-term stabilization of soil organic carbon. Moreover, studies indicate that the combined application of biochar and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) can regulate plant physiological, biochemical, and agronomic traits, thereby enhancing crop resilience under drought conditions [12]. Beyond these effects, the high surface area and porous structure of biochar enable the chelation and adsorption of heavy metals (e.g., arsenic), supporting water purification and soil remediation [13]. Biochar can further improve nitrogen use efficiency, modulate soil enzyme activities, and foster beneficial microbial communities, collectively influencing nutrient cycling and greenhouse gas (GHG) dynamics [14,15]. However, these microbial inter-actions may also modify CO2 and N2O emissions, with effects dependent on soil type, amendment rate, and crop system [16].

Studies on the effectiveness of biochar in mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have produced variable outcomes. Some research has shown that biochar can significantly reduce nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions by enhancing soil aeration and influencing microbial denitrification processes [17,18]. However, other investigations have observed increases in carbon dioxide (CO2) efflux, potentially driven by stimulated microbial activity or rhizosphere priming effects [19]. In addition, recent findings suggest that adjusting soil moisture levels [20] and modifying cultivation regimes [21] can also contribute to GHG emission reductions in managed agroecosystems. These outcomes appear to be highly context-dependent, influenced by variables such as soil composition, amendment type, and climatic conditions. Meta-analyses by Woolf et al. [22] and Biederman & Harpole [23] have confirmed the general efficacy of biochar in enhancing soil carbon stability and nitrogen use efficiency, especially in marginal or nutrient-deficient soils. In tropical and subtropical settings, biochar amendments have further been associated with improved plant resilience against soil acidification and periodic drought stress, making them particularly suitable for bamboo cultivation under environmental extremes. Notably, Novak et al. [24] and Gao et al. [25] reported synergistic benefits when biochar is applied alongside organic fertilizers, including enhanced microbial diversity and more efficient nutrient cycling, potentially shifting net GHG outcomes in favor of carbon retention. These results emphasize the importance of application strategies and soil conditions when using biochar as a climate mitigation tool. Despite these promising findings, empirical evidence from subtropical coastal regions, particularly those affected by saline soil and water stress, remains limited. Taiwan’s bamboo shelterbelt systems therefore provide a valuable context for evaluating how organic and biochar amendments influence ecosystem carbon balance and emission dynamics.

This study aimed to assess the impacts of different soil amendment regimes on the greenhouse gas fluxes and carbon assimilation capacity of Bambusa edulis windbreak systems located in Dongshi Township, Chiayi County, southwestern Taiwan. A one-year field trial was conducted across four management treatments: control (C), biochar (B), fertilizer (F), and biochar plus fertilizer (B + F) application. We hypothesize that biochar, when applied alone or in combination with organic fertilizer, can reduce GHG emissions while enhancing photosynthetic carbon uptake compared to fertilizer-only treatments. By monitoring soil CO2 and N2O fluxes using static chamber techniques, alongside leaf-level photosynthetic performance and estimated carbon assimilation rates, this study provides insight into the seasonal carbon dynamics of coastal bamboo ecosystems. This research offers crucial, site-specific empirical data by concurrently evaluating the trade-off between greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and photosynthetic carbon uptake in a coastal bamboo shelterbelt system. Furthermore, this study was conducted within the challenging context of the saline–alkaline sandy soils of south-western Taiwan, an environment where such empirical evidence remains limited.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Experimental Design

2.1.1. Location

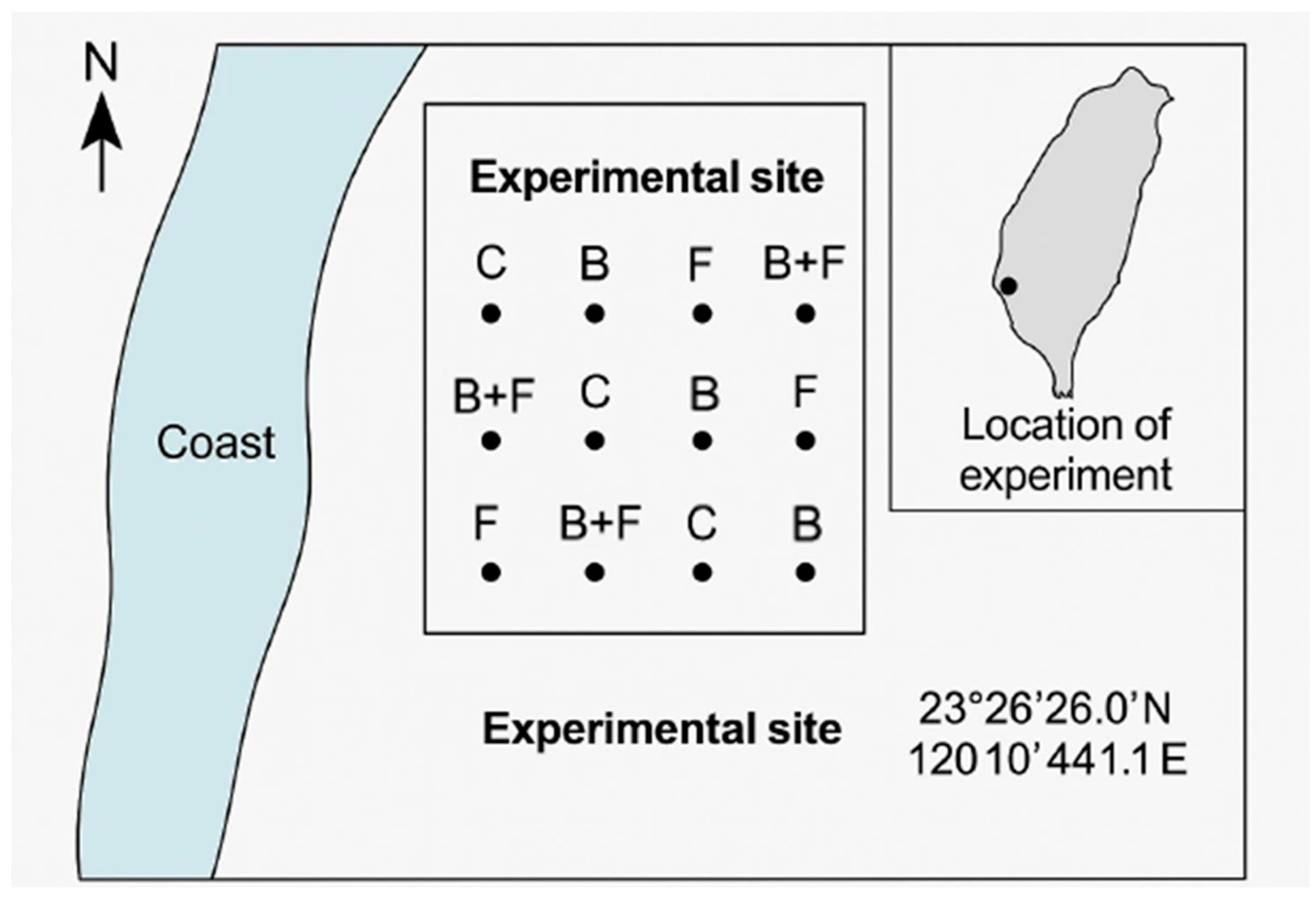

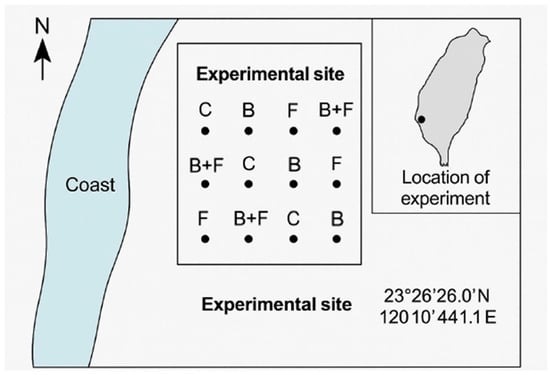

The field experiment was carried out in a coastal windbreak forest located in Wenzi Village, Dongshi Township, Chiayi County, Taiwan (23°26′26.0″ N, 120°10′44.1″ E). Meteorological data for the study site were obtained from the Chiayi Weather Station of the Central Weather Administration, located at 23°29′45.3″ N, 120°25′58.5″ E.

2.1.2. Climatic Data

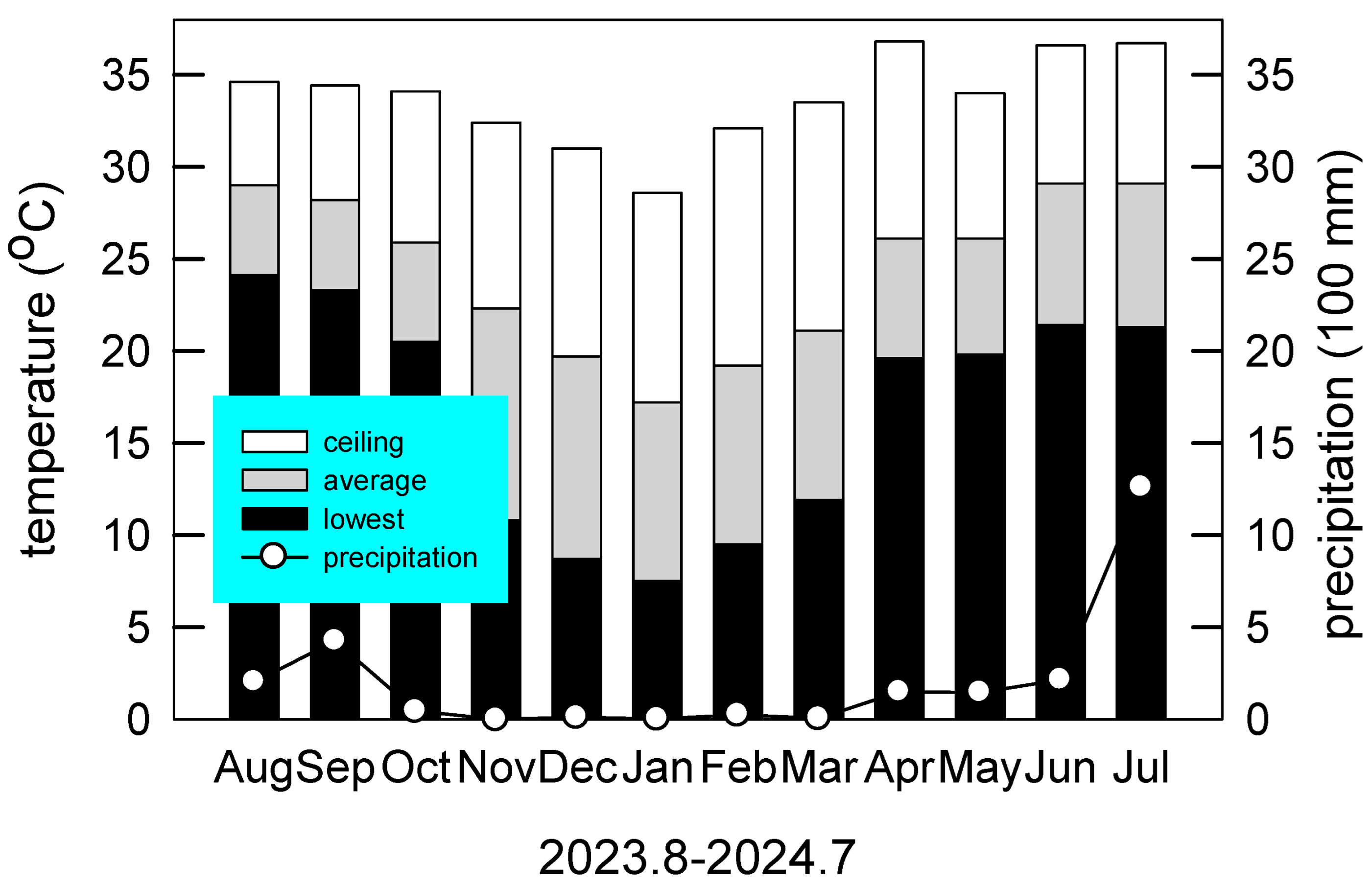

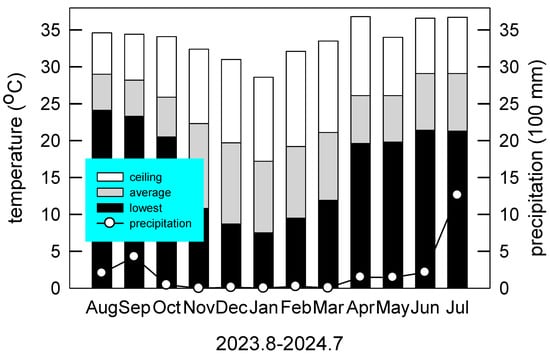

The monitoring period spanned from August 2023 to July 2024, corresponding precisely with the duration of the field experiment. During this period, the total annual precipitation was 2491 mm. The highest recorded temperature was 36.8 °C in April (spring), while the lowest was 7.5 °C in January (winter). The mean annual temperature was 24.41 °C (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Monthly air temperatures (bar) and precipitation (circle) during the study period from August 2023 to July 2024 at Chiayi County, Taiwan (23°29′45.3″ N, 120°25′58.5″ E).

2.1.3. Soil Characterization

The soil at the experimental site was classified as mildly saline–alkaline sandy soil, with a salt content ranging from 0.1% to 0.25% and a pH of approximately 8.5 (Figure 2). According to the classification standard widely used by U.S. Salinity Laboratory Staff [26], the soil condition at this site was Slightly saline.

Figure 2.

The field experiment was carried out in a coastal windbreak forest located in Wenzi Village, Dongshi Township, Chiayi County, Taiwan (23°26′26.0″ N, 120°10′44.1″ E). The experiment included four soil amendment treatments: control (C), biochar (B), fertilizer using vermicompost (F), and a combination of biochar and fertilizer (B + F). Each treatment included three monitored bamboo clumps.

2.1.4. Crop and Its Management

The plant material used in the study consisted of a salt-tolerant cultivar of Bambusa edulis, specifically selected and propagated for its adaptability to saline environments [27]. Saline soils are typically characterized by high concentrations of soluble salts—particularly Na+, Cl−, and SO42−—which can adversely affect plant water uptake, enzyme activity, and microbial processes.

The total area is approximately 0.4 hectares, with a planting density of 4 m × 4 m. The trial spanned from August 2023 to July 2024, during which data was collected at monthly intervals. The experiment included four soil amendment treatments: control (C), biochar (B), fertilizer using vermicompost (F), and a combination of biochar and fertilizer (B + F). Amendments were applied on four occasions: 31 August 2023 (autumn); 22 November 2023 (winter); 22 February 2024 (spring); and 15 May 2024 (summer). Fertilization was performed using 5 kg of vermicompost per clump per application. Biochar treatments used 5 kg of commercially available rice husk biochar per clump. For the combined treatment (B + F), each clump received 5 kg of vermicompost and 5 kg of biochar per application.

2.1.5. Measurement

Each treatment included three monitored bamboo clumps. During each seasonal measurement, the following parameters were recorded: (1) leaf-level photosynthesis, assessed by selecting two leaves per clump; (2) soil CO2 flux, measured at three locations around each clump; and (3) soil N2O flux, also measured at three locations around each clump. For each treatment, three bamboo clumps were selected for monitoring.

2.2. Soil Greenhouse Gas Flux Measurement

Monthly measurements of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, specifically carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O), were conducted using a closed chamber method. Gas fluxes were quantified by connecting transparent chamber lids to gas analyzers—namely, a CO2 analyzer (LI-830) and an N2O analyzer (LI-7820) were produced by LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA—with data recorded via the default data loggers supplied with each device.

The chamber system, developed by our research team, consists of a semi-cylindrical transparent acrylic upper cover and a circular stainless steel base ring (20 cm in height, 30 cm in diameter). For larger plants, an oversized acrylic chamber lid was used to accommodate plant height. During each measurement, the steel ring was inserted 5 cm into the soil. The acrylic cover was then secured tightly to the base using strong clamps to ensure airtight conditions. A pump and flexible tubing were used to direct the enclosed air from the chamber to the analyzers.

When plant height exceeded the standard chamber capacity, a larger chamber (24 × 24 × 50 cm or greater) was used to capture GHG emissions.

Gas fluxes were calculated using the ideal gas law, based on the linear increase in gas concentration over time. The flux (F) was calculated using the following equation [20,21,28]:

where:

Flux = (S × V × t_c × M)/(RT × 1000 × A)

- F: Gas flux (mg m−2 h−1)

- S: Slope of gas concentration increase over time (ppm s−1) (CH4: 20 s; N2O: 20 s; CO2: 30 s)

- V: Volume of the chamber (L)

- tc: Time conversion constant, N2O: 20 s: 180 = (1 h × (60 min/h) × ((60 s/min)/20 s)); CO2: 120 = (1 h × (60 min/h) × ((60 s/min)/30 s))

- M: Molecular weight of the gas (g mol−1)

- R: Ideal gas constant (0.082 L atm mol−1 K−1)

- T: Absolute temperature (K)

- 1000: Unit conversion factor (1 mg = 1000 µg)

- A: Area of the chamber base (m2)

2.3. Photosynthetic Carbon Assimilation Measurement

Carbon assimilation in Bambusa edulis (Odashima) was estimated based on leaf photosynthetic responses, measured using a portable photosynthesis system (GFS 3000, Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). Photosynthetic light response curves were generated, and key parameters were calculated following the methods described by Chen et al. [29]. These parameters included the maximum assimilation rate (Amax), quantum efficiency (α), light compensation point (LCP), light saturation point (LSP), curve shape parameter (θ), and dark respiration rate (Rd).

The values of α, LCP, and Rd were derived from the linear portion of the light response curve under low irradiance conditions (≤50 mold m−2 s−1), using linear regression. Carbon assimilation rates were estimated using the model proposed by Chen et al. [29], with the following equation for net photosynthetic rate (A, μmol m−2 s−1):

In Equation (2), the parameters Amax, α, and θ were obtained from light response curves measured in different seasons. Il (μmol m−2 s−1) represents the incident light intensity and was estimated using Beer’s Law, based on canopy-level measurements following the method described by Chen et al. [29].

Once the leaf-level net photosynthetic rate (A) was calculated, the daily carbon assimilation per plant (Ac) was estimated using Equation (3), incorporating daily photoperiod (h) and total leaf area (L). Monthly CO2 assimilation was obtained by multiplying Ac by the number of days in each month. The annual CO2 assimilation per plant was calculated as the sum of monthly values [29].

Leaf area index (LAI) was measured monthly using a plant canopy analyzer (LAI-2200, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). For each sampling event, LAI readings were taken at four orientations around each of the three sample bamboo clumps. A 90° view cap was used during measurements to minimize distortion from the central culm. The software (FV2200, LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) was used to calculate LAI, which was then combined with the measured canopy radius to estimate the ground projection area and total leaf area per plant [28].

Nighttime respiration was estimated using the dark respiration rate (Rd) obtained from the light response curve. To correct for temperature effects, respiration temperature response curves were concurrently measured. Monthly dark respiration rates were adjusted based on mean monthly temperatures. Nighttime respiration was then calculated using the following equation:

In Equation (4), Rt represents the temperature-adjusted dark respiration rate, and n denotes the duration of nighttime (in hours). The product of Rt and n yields the daily nighttime respiration per plant (Rc). Multiplying Rc by the number of days in each month provides the monthly respiration total. Finally, net carbon flux (i.e., net primary productivity, NPP) was calculated by subtracting total respiration from total assimilation for each plant [29].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics 18 and SigmaPlot 10.0 software. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test was applied to evaluate significant differences among treatment means. In addition, Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the relationships between greenhouse gas fluxes (CO2 and N2O) and environmental variables, including air temperature and precipitation. All data were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance prior to analysis to ensure the validity of parametric assumptions.

3. Results

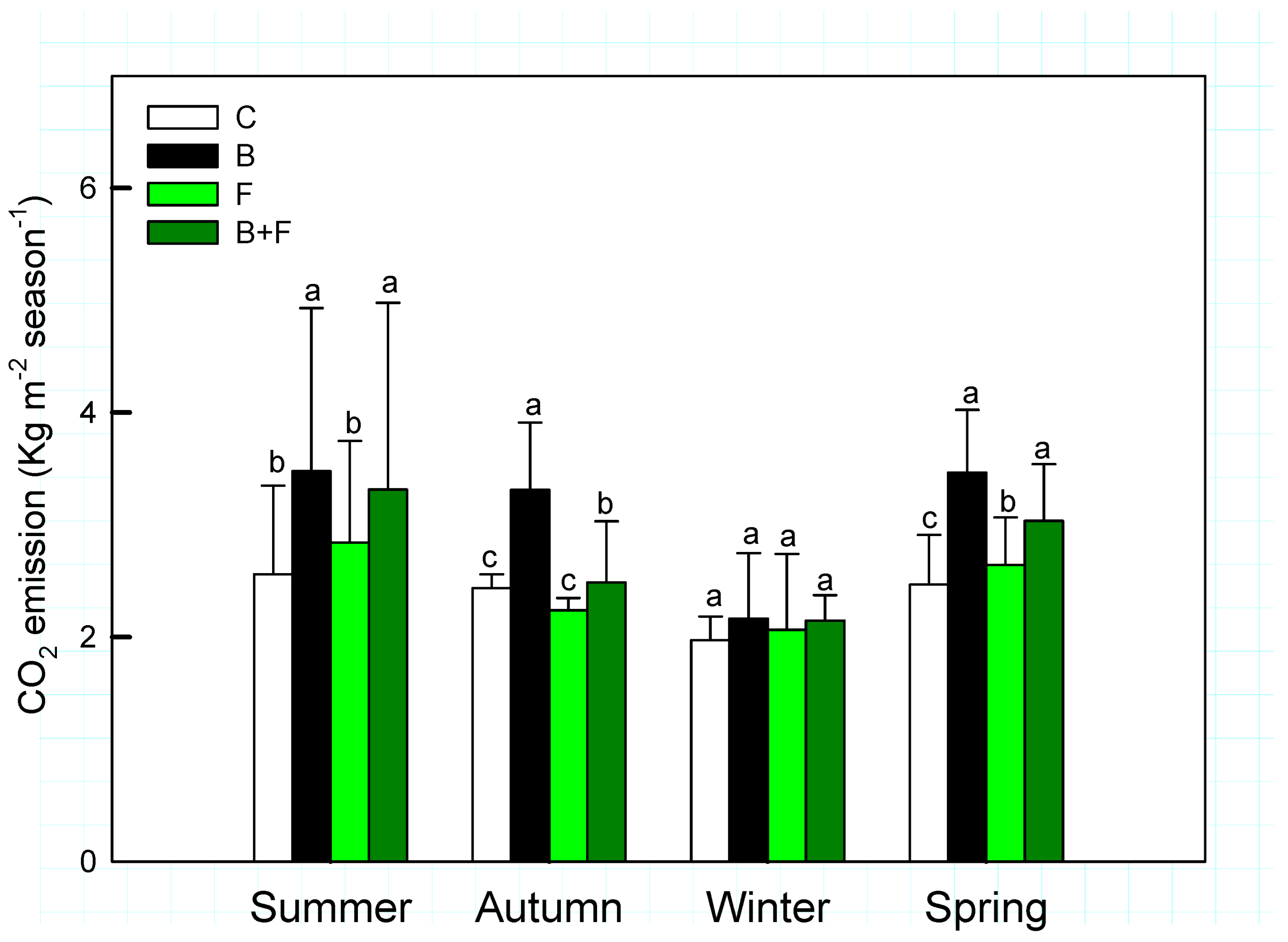

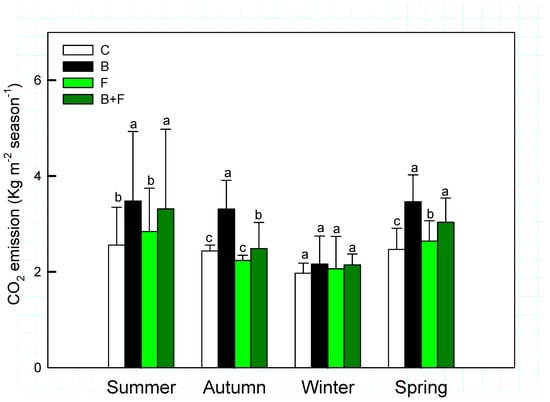

3.1. Seasonal Variation in CO2 Emissions

Seasonal averages of soil CO2 fluxes in Bambusa edulis plots are presented in Figure 3. Across the four seasons, soil CO2 emissions exhibited both temporal variation and treatment-specific differences. The mean seasonal CO2 efflux ranged between 2 and 4 kg m−2, following the order: control (C) < fertilizer only (F) < biochar combined with fertilizer (B + F) < biochar alone (B). These results indicate that biochar application generally led to increased CO2 emissions, with statistically significant differences observed (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were detected among all treatments when analyzed pairwise.

Figure 3.

Seasonal variation of soil CO2 emission (Kg m−2 season−1) under different treatments (C = control, B = biochar, F = fertilizer, B + F = biochar + fertilizer). Error bars represent standard deviation. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in Tukey HSD analysis among the four field treatments (n = 12).

The B + F treatment produced intermediate levels of CO2 flux—averaging 3.31 ± 1.66 µmol m−2 s−1 in summer and 2.15 ± 0.23 µmol m−2 s−1 in winter—suggesting potential interactive effects between organic and inorganic inputs. Notably, CO2 emissions declined across all treatments during the winter season, likely due to reduced atmosphere temperatures inhibiting microbial respiration and root activity.

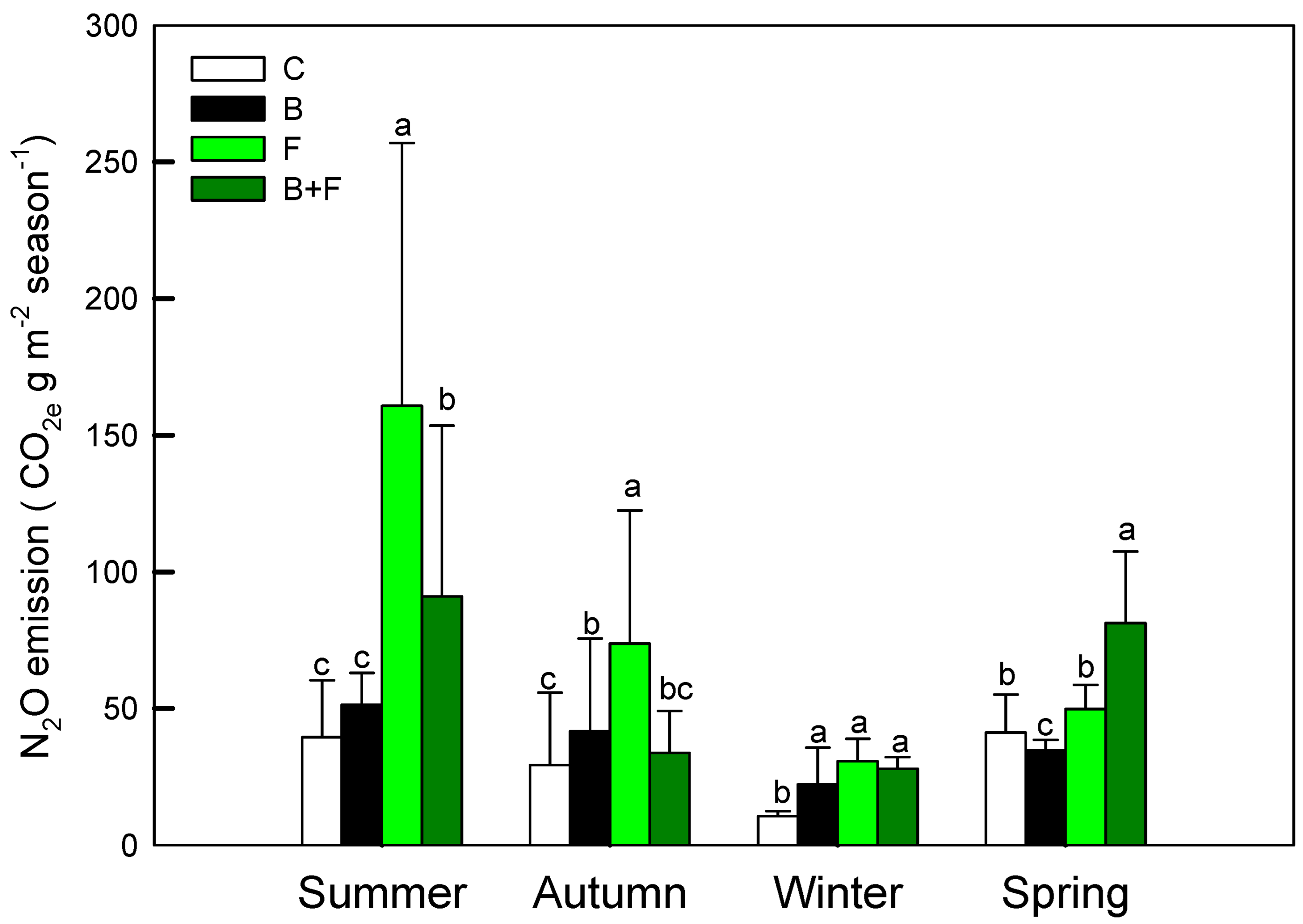

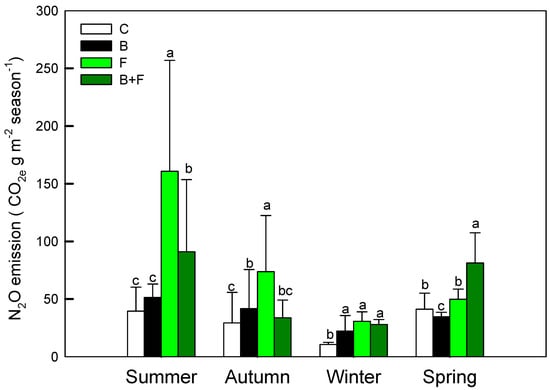

3.2. N2O Emissions and Fertilizer Response

Soil N2O fluxes displayed pronounced differences among treatments in Figure 4 Plots receiving fertilizer (F) or biochar plus fertilizer (B + F) consistently exhibited higher N2O emissions compared to the control (C) and biochar-only (B) treatments. Notably, peak N2O fluxes occurred following fertilization events and during warmer seasons, particularly summer and autumn. The highest emission levels in F-treated plots reached 160.73 ± 96.22 g CO2 e m−2 during summer and 73.83 ± 48.56 g CO2 e m−2 in autumn.

Figure 4.

Seasonal N2O emission (CO2 e g m−2 season−1) under different treatments (C = control, B = biochar, F = fertilizer, B + F = biochar + fertilizer). Error bars represent standard deviation. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in Tukey HSD analysis among the four field treatments (n = 12).

These findings indicate that vermicompost application significantly stimulates N2O emissions, likely via enhanced nitrification and denitrification processes. In contrast, the incorporation of biochar was associated with substantial emission reductions—43.3% lower in summer and 54.3% lower in autumn relative to fertilizer-only plots—highlighting its mitigation potential. Statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA revealed significant treatment effects (p < 0.05). Post hoc comparisons further clarified the ranking of annual N2O emissions as follows: C ≈ B > B + F > F. These results underscore the dominant role of nitrogen inputs in driving N2O fluxes and suggest that biochar may help suppress emissions when co-applied with fertilizers.

Pearson correlation analysis (Table 1) revealed that CO2 fluxes were positively associated with atmosphere temperature (r = 0.63, p < 0.01) and rainfall (r = 0.45, p < 0.05). N2O fluxes showed even stronger correlation with rainfall (r = 0.71, p < 0.001), indicating its central role in regulating gaseous nitrogen losses. No significant correlations were found between gas fluxes and atmosphere temperature, suggesting below that rainfall, which affects ground conditions, were the dominant drivers.

Table 1.

Pearson correlation coefficients between soil greenhouse gas emissions and environmental factors.

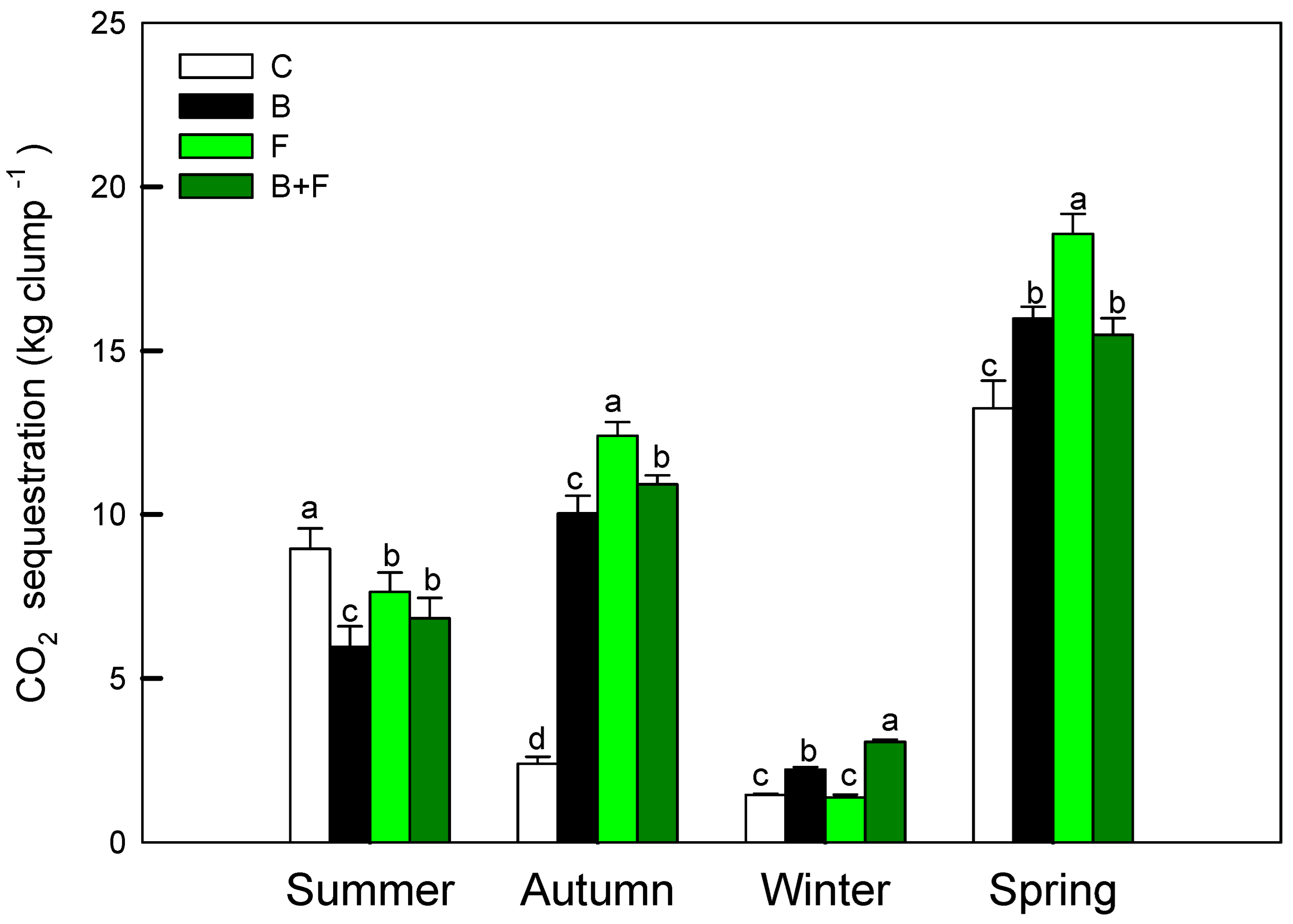

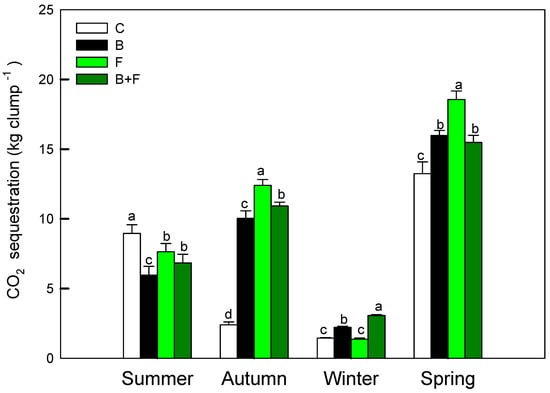

3.3. Carbon Assimilation Performance

Measurements of photosynthetic performance revealed both seasonal variation and treatment-dependent differences in net carbon assimilation. As shown in Figure 5, the seasonal carbon sequestration capacity of Bambusa edulis ranged from approximately 1.8 to 18.5 kg CO2 per clump per season. Among the four treatments, the fertilizer-only (F) group exhibited the highest carbon assimilation, with a peak value of 18.6 kg CO2 clump−1 observed in spring. The biochar plus fertilizer (B + F) treatment followed, with a seasonal average of 9.9 kg CO2 clump−1, while the biochar-only (B) treatment yielded a slightly lower average of 8.5 kg CO2 clump−1. The control (C) group consistently showed the lowest carbon uptake, averaging 6.5 kg CO2 clump−1 across all seasons. Based on proportional comparison with the fertilization (F) treatment, the B + F treatment reduced spring carbon assimilation to 83.4%. In contrast, the control plots showed the lowest values, with spring carbon assimilation accounting for only 71.3% of the F treatment, respectively (13.2 kg CO2 clump−1).

Figure 5.

Seasonal net carbon assimilation rates (kg clump−1) estimated from photosynthetic activity and LAI. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in Tukey HSD analysis among the four field treatments (n = 12).

In autumn, the carbon assimilation of the control group was significantly lower (p < 0.05), likely due to reduced precipitation that intensified drought stress. In the absence of nutrient supplementation, plants in the control plots experienced more pronounced physiological decline under water-limited conditions.

All treatments exhibited their lowest carbon assimilation rates in winter, corresponding to the dormant phase of bamboo growth. With the onset of spring rainfall, new leaf emergence stimulated an increase in photosynthetic activity and carbon uptake. The seasonal trends observed highlight the role of fertilization in enhancing canopy productivity and total carbon input across growth cycles.

When comparing GHG emissions with assimilation rates, the F and B + F treatments showed higher gross CO2 release but also substantially elevated carbon uptake. The biochar treatment (B) offered a balanced profile with moderate emissions and enhanced photosynthesis. Control plots maintained the lowest emissions and uptake. This result highlights the benefits of biochar application in reducing greenhouse gas emissions under fertilized cultivation, carrying important implications for carbon budgeting and mitigation strategies in bamboo agroecosystems.

4. Discussion

4.1. CO2 Emissions

The elevated CO2 efflux observed in the fertilizer (F) and biochar-plus-fertilizer (B + F) treatments in this study can be attributed to a rise in heterotrophic respiration, likely stimulated by microbial proliferation in response to nutrient availability [30]. Enhanced nitrogen levels are known to promote root development and rhizosphere metabolic activity, thereby contributing to higher respiration rates [31,32]. Moreover, the peak CO2 emissions recorded during the summer season reflect optimal microbial and root functioning under warm and moist conditions [33]. Crucially, while fertilization drove total respiration up, the B + F treatment produced moderate CO2 fluxes relative to the fertilizer-only plots. This suggests that the co-application of biochar and composted inputs successfully tempered microbial decomposition rates and modulated carbon release in this saline soil system.

These findings are consistent with previous research highlighting the influence of environmental and management factors on GHG dynamics [34,35]. The pattern observed here exemplifies a common trade-off in tropical agroecosystems, where productivity gains are often accompanied by elevated emission intensities [36]. Regarding biochar effects, although some studies attribute increased emissions to priming effects from labile carbon [17,37], our results align more closely with research demonstrating microbial immobilization and stabilization of organic carbon [38]. For instance, Bovsun et al. [39] reported that biochar application could reduce soil CO2 emissions by 28.2% to 57.7% (at rates of 3 kg/m2 and 1 kg/m2, respectively). The fact that our B + F treatment maintained lower fluxes than the F treatment corroborates this stabilizing potential, distinguishing biochar’s role from that of purely labile organic amendments.

4.2. N2O Emissions and Nitrogen Transformation Pathways

Our results showed that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions varied significantly among treatment types. Plots treated with nitrogen fertilizer (vermicompost) exhibited the highest N2O emissions, particularly during the summer and autumn seasons. The rapid nitrogen availability in vermicompost creates microbial “hotspots”, triggering pulses of GHG emissions [40]. This observation is consistent with Shcherbak et al. [41], who reported a nonlinear escalation of N2O fluxes with increased nitrogen fertilizer rates, largely due to intensified nitrification–denitrification pathways [42,43]. These findings are also in line with the global trend reported by Amirahmadi et al. [44], whose meta-analysis revealed that combined biochar and chemical fertilizer (BCF) treatments led to a 62.9% increase in N2O emissions. In contrast, the B + F treatment in our study resulted in lower emissions. This is attributed to its gradual nutrient release and higher carbon-to-nitrogen ratio, which promotes microbial nitrogen immobilization and limits denitrification. Charles et al. [45] noted that while organic fertilizers display greater variability, they typically reduce average N2O output due to improved microbial stability. Furthermore, combining biochar with organic fertilizers has been shown to enhance nitrogen retention, alter microbial community structure, and suppress denitrification processes [40,46]. These findings suggest that, although reducing fertilizer use can lower N2O emissions, fertilization remains essential in saline–alkaline farmlands to ensure yield stability. Under such conditions, the integration of biochar with fertilization emerges as a priority strategy for mitigating N2O emissions while sustaining agricultural productivity [24,25].

Environmental factors also modulate GHG fluxes. Rainfall was significantly correlated with N2O emissions in our study, reaffirming the findings by Xia et al. [47], who emphasized that water-filled pore space (WFPS) strongly influences N2O emissions, with the highest fluxes occurring when WFPS ranges between 50% and 90%. Such mechanisms may explain why periodic drying cycles in paddy fields, as reported by Loaiza et al. [48], tend to increase N2O emissions under alternate wetting and drying (AWD) conditions. During the drying phase, enhanced nitrification can stimulate subsequent aerobic N2O release, while re-flooding may trigger denitrification, further elevating emissions [32,49]. On the other hand, the experimental results of Yang et al. [20] indicated that reducing fertilizer application decreases N2O emissions and can further suppress the effects of soil moisture fluctuations. In addition to moisture, the total amount of emissions will vary depending on soil texture, which is related to soil microbial activity, and this is a critical factor that needs to be considered in future research [50]. However, a limitation of the present study is that we did not measure changes in soil moisture or spatial texture variations, which prevents a more direct analysis of this mechanism. Nevertheless, the application of biochar, due to its porous structure, can further mitigate N2O formation under fluctuating moisture conditions [51], a process consistent with the patterns observed in this study.

Regarding the frequency of greenhouse gas (GHG) measurements, the development of Tier 3 emission factors typically requires monitoring at weekly or biweekly intervals to capture short-term fluctuations. However, numerous studies on GHG emissions from paddy fields have demonstrated that conducting measurements every 7–10 days during critical growth stages (e.g., tillering, heading, and irrigation periods) is sufficient to effectively capture the peaks and temporal trends of CH4 and N2O emissions. For example, experiments conducted in China, Korea, and Japan have successfully employed 7–10 day intervals to obtain reliable estimates of seasonal cumulative emissions, which have been widely published in international journals [18,20,21,52,53,54]. Accordingly, the measurement intervals adopted in this study were designed based on these references and are statistically robust in reflecting both seasonal variations and treatment effects. It is important to note that monthly sampling may not capture short-term flux spikes. Consequently, the cumulative emission values reported here should be interpreted as conservative estimates, although the relative trends among treatments remain representative. These results provide empirical evidence that integrated use of biochar and compost represents a viable strategy to reduce GHG intensity while sustaining photosynthetic performance. Finally, the coastal site’s saline conditions likely influenced these dynamics; the enhanced performance under biochar treatments may partly reflect improved osmotic buffering, which warrants further investigation through direct salinity measurements in future studies.

4.3. Carbon Assimilation and Photosynthetic Response

The enhancement of bamboo’s photosynthetic performance under fertilization aligns with well-documented physiological mechanisms, whereby increased nitrogen availability promotes chlorophyll synthesis, Rubisco enzyme activity, and stomatal regulation [55,56]. Consequently, the elevated net assimilation rates (An) observed in fertilizer (F) and biochar-plus-fertilizer (B + F) plots mirror responses seen in other high-biomass, fast-growing species such as Eucalyptus [57]. In terms of productivity, carbon assimilation estimates based on leaf area index (LAI) ranged from 1.8 to 18.5 kg CO2 per clump per season. These values are consistent with, or even surpass, those reported for intensively managed bamboo plantations in subtropical China [5,6]. To contextualize these findings for carbon inventory purposes, we upscaled these clump-level rates assuming a standard planting density of 400 clumps h−1. The results demonstrate a significant increase in mitigation potential: from 0.72 tons CO2 e ha−1 in the unfertilized control to 7.4 tons CO2 e ha−1 per growing season in the biochar-fertilized treatment. This ten-fold increase underscores the scalability of nutrient-management strategies in enhancing the carbon sink function of bamboo forests.

4.4. Management Implications for Bamboo Agroecosystems

The observed trade-off between enhanced carbon uptake and increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the fertilizer (F) and biochar-plus-fertilizer (B + F) treatments underscores the complexity of managing bamboo-based agroforestry systems for both productivity and climate outcomes. While the use of synthetic fertilizers can drive short-term gains in biomass accumulation, the associated rise in N2O emissions poses challenges for long-term carbon neutrality if not carefully managed [58].

Conversely, compost-only treatments offered a more favorable balance, achieving improved photosynthetic performance while maintaining relatively low GHG emissions. This aligns with findings by Agegnehu et al. [59], who reported that organic amendments can enhance soil health and plant growth without promoting excessive nitrogen losses. Adekiya et al. [7] also reported that long-term application of biochar and plant residues in subtropical maize systems significantly increased soil organic carbon and sustained crop yields. The addition of biochar, as demonstrated in this study, further contributed to N2O mitigation, highlighting its value as a carbon-stabilizing amendment with long-term sequestration potential [60].

With the growing emphasis on soil-derived greenhouse gas emissions within climate policy frameworks and voluntary carbon credit systems, localized empirical evidence is becoming increasingly essential for informing monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) protocols. In alignment with Taiwan’s 2050 carbon neutrality objectives, the strategic integration of bamboo shelterbelt systems—particularly under well-regulated nutrient regimes—presents a promising solution to reconcile carbon sequestration efforts with emission mitigation targets [61]. Furthermore, evaluating the performance of bamboo species alongside other reforestation or afforestation alternatives may assist in optimizing land-use decisions [2,62]. Considering bamboo’s ecological advantages—including rapid biomass recovery, effective erosion control, and contributions to rural livelihoods—properly managed bamboo landscapes hold strong potential to serve as multifunctional assets in climate-resilient rural development strategies.

5. Conclusions

The joint application of biochar and fertilizer significantly upregulated bamboo photosynthetic capacity (An) and leaf area index, driving substantial biomass accumulation. With carbon assimilation estimates reaching 1.8–18.5 kg CO2 per clump per season, nutrient management emerges as a critical lever for maximizing ecosystem productivity. In the context of Taiwan’s “Net Zero 2050” goals, these findings validate the potential of intensively managed bamboo forests as high-efficiency carbon sinks. Specifically, the superior sequestration rates observed in biochar-amended plots provide the necessary scientific baseline for developing bamboo-specific carbon offset methodologies and establishing the “additionality” required for carbon credit certification. Future forest management policies should therefore prioritize precision fertilization and biochar integration to optimize bamboo’s contribution to regional carbon mitigation strategies.

Author Contributions

Y.-P.H., Conceptualization; Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, C.-I.C.: Methodology, Writing—review & editing; C.-P.S.: Methodology, Writing—original draft; J.-Y.S.: Investigation; W.-C.C.: Writing—review & editing; Y.-H.L.: Formal analysis, Project administration, Resources; S.-C.L.: Investigation; C.-C.C.: Writing—review & editing; X.-C.Y.: Writing—original draft; W.-H.H.: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing; C.-W.W.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Seddon, N.; Chausson, A.; Berry, P.; Girardin, C.A.J.; Smith, A.; Turner, B. Understanding the value and limits of nature-based solutions to climate change and other global challenges. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi). Foundations for Science-Based Net-Zero Target Setting in the Corporate Sector; SBTi: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://sciencebasedtargets.org (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). Guidance on the Identification and Assessment of Nature-Related Issues. In The LEAP Approach; TNFD: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://tnfd.global (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Wang, Y.C. Estimates of biomass and carbon sequestration in Dendrocalamus latiflorus culms. For. Prod. Ind. 2004, 23, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Zhou, G.; Jiang, H.; Yu, S.; Fu, J.; Li, W.; Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Peng, C. Carbon sequestration by Chinese bamboo forests and their ecological benefits: Assessment of potential, problems, and future challenges. Environ. Rev. 2011, 19, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekiya, A.O.; Alori, E.T.; Ogunbode, T.O.; Sangoyomi, T.; Oriade, O.A. Enhancing organic carbon content in rropical soils: Strategies for sustainable agriculture and climate change mitigation. Open Agric. J. 2023, 17, e18743315282476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; Yen, T.M. Assessing aboveground carbon storage capacity in bamboo plantations with various species related to its affecting factors across Taiwan. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 481, 118745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.Y.; Hsieh, I.F.; Lin, P.H.; Laplace, S.; Ohashi, M.; Chen, T.H.; Kume, T. Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens) forests as a significant carbon sink? A case study based on 4-year measurements in central Taiwan. Ecol. Res. 2017, 32, 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, M.J.; Grønli, M. The art, science, and technology of charcoal production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 1619–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, S.; Bezemer, T.M.; Cornelissen, G.; Kuyper, T.W.; Lehmann, J.; Mommer, L.; Sohi, S.P.; van de Voorde, T.F.; Wardle, D.A.; van Groenigen, J.W. The way forward in biochar research: Targeting trade-offs between the potential wins. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2015, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul-Lalay; Ullah, S.; Shah, S.; Jamal, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Mihoub, A.; Zia, A.; Ahmed, I.; Seleiman, M.F.; Mancinelli, R.; et al. Combined effect of biochar and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on physiological responses of canola (Brassica napus L.) subjected to drought stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 1814–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Ghaffar, A.; Zakir, A.; Khan, Z.U.H.; Saeed, M.F.; Rasool, A.; Jamal, A.; Mihoub, A.; Marzeddu, S.; Boni, M.R. Activated biochar is an effective technique for arsenic removal from contaminated drinking water in Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, D.; Liang, G.; Liang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Ai, C.; Zhou, W. Maize biochar addition rate influences soil enzyme activity and microbial community composition in a fluvo-aquic soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2015, 96, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Razavi, B.; Ludwig, B.; Zamanian, K.; Zang, H.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Dippold, M.A.; Gunina, A. Combined biochar and nitrogen application stimulates enzyme activity and root plasticity. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for Environmental Management: An Introduction. In Biochar for Environmental Management; Joannes, L., Stephen Joseph, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Pan, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Effects of biochar application on fluxes of three biogenic greenhouse gases: A meta-analysis. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2016, 2, e01202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, J.; Müller, K.; Li, Y.; Fu, W.; Lin, Z.; Wang, H. Effects of biochar application in forest ecosystems on soil properties and greenhouse gas emissions: A review. J. Soils Sediments 2018, 18, 546–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Yi, Q.; Xu, M.; Zheng, J.; Bian, R.; Zhang, X.; Pan, G. Biochar improves soil organic carbon stability by shaping the microbial community structures at different soil depths four years after an incorporation in a farmland soil. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 5, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.C.; Huang, M.Y.; Chen, C.I.; Lin, C.H.; Huang, W.H.; Lee, L.H.; Wang, C.W. Assessing the benefits of alternating wet and dry (AWD) irrigation of rice fields on greenhouse gas emissions in central Taiwan. Taiwania 2025, 70, 530–539. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.W.; Lin, K.H.; Feng, Y.Z.; Lin, Y.W.; Yang, Z.W.; Chen, C.I.; Huang, M.-Y. Effects of crop rotation and tillage on CO2 and CH4 fluxes in paddy fields. Taiwania 2025, 70, 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Street-Perrott, F.A.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, L.A.; Harpole, W.S. Biochar and its effects on plant productivity and nutrient cycling: A meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.M.; Lima, I.; Xing, B.; Gaskin, J.W.; Steiner, C.; Das, K.C.; Ahmedna, M.; Rehrah, D.; Watts, D.W.; Busscher, W.J.; et al. Characterization of designer biochar produced at different temperatures and their effects on a loamy sand. Ann. Environ. Sci. 2009, 3, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Cui, K.; Wu, Z.; Shi, M.; Song, X. Biochar amendment alters the nutrient-use strategy of Moso bamboo under N additions. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 667964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Salinity Laboratory Staff. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils. In Agriculture Handbook 60; Richards, L.A., Ed.; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.C.; Huang, L.C.; Chang, C.T.; Sung, H.Y. Purification and characterization of soluble invertases from suspension-cultured bamboo (Bambusa edulis) cells. Food Chem. 2006, 96, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, S.H.; Wu, H.; Hsieh, H.L.; Chen, C.P.; Lin, H.J. Effects of modulating probiotics on greenhouse gas emissions and yield in rice paddies. Plant Soil Environ. 2025, 71, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-I.; Wang, Y.-N.; Lin, H.-H.; Wang, C.-W.; Yu, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-C. Seasonal photosynthesis and carbon assimilation dynamics in a Zelkova serrata (Thunb.) Makino Plantation. Forests 2021, 12, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raich, J.W.; Tufekciogul, A. Vegetation and soil respiration: Correlations and controls. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subke, J.A.; Inglima, I.; Cotrufo, M.F. Trends and methodological impacts in soil CO2 efflux partitioning: A meta-analytical review. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 921–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, R.; Li, R.; Hu, Y.; Guo, S. Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration to nitrogen fertilization: Varying effects between growing and non-growing seasons. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A.; Luo, Y. On the variability of respiration in terrestrial ecosystems: Moving beyond Q10. Glob. Change Biol. 2006, 12, 154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.P.; Hatton, B.J.; Singh, B.; Cowie, A.L.; Kathuria, A. Influence of biochars on nitrous oxide emission and nitrogen leaching from two contrasting soils. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 1224–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertel, C.; Matschullat, J.; Zurba, K.; Zimmermann, F.; Erasmi, S. Greenhouse gas emissions from soils—A review. Geochemistry 2016, 76, 327–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Chen, X. Meta-analysis data quantifying nitrous oxides emissions from Chinese vegetable production. Data Brief 2018, 19, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, A.R.; Gao, B.; Ahn, M.Y. Positive and negative carbon mineralization priming effects among a variety of biochar-amended soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M.; Sorrenti, G.; Panzacchi, P.; George, E.; Tonon, G. Biochar reduces short-term nitrate leaching from a horizon in an apple orchard. J. Environ. Qual. 2013, 42, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovsun, M.A.; Castaldi, S.; Nesterova, O.V.; Semal, V.A.; Sakara, N.A.; Brikmans, A.V.; Khokhlova, A.I.; Karpenko, T.Y. Effect of Biochar on Soil CO2 Fluxes from Agricultural Field Experiments in Russian Far East. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalos, D.; Jeffery, S.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; Guardia, G.; Vallejo, A. Meta-analysis of the effect of urease and nitrification inhibitors on crop productivity and nitrogen use efficiency. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 189, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, I.; Millar, N.; Robertson, G.P. Global meta-analysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9199–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggs, E.M. Soil microbial sources of nitrous oxide: Recent advances in knowledge, emerging challenges and future direction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Yan, X.; Yagi, K. Evaluation of effectiveness of enhanced-efficiency fertilizers as mitigation options for N2O and NO emissions from agricultural soils: Meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1837–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirahmadi, E.; Ghorbani, M.; Adani, F. Biochar contribution in greenhouse gas mitigation and crop yield considering pyrolysis conditions, utilization strategies and plant type—A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A.; Rochette, P.; Whalen, J.K.; Angers, D.A.; Chantigny, M.H.; Bertrand, N. Global nitrous oxide emission factors from agricultural soils after addition of organic amendments: A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 236, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, A.; Ji, C.; Joseph, S.; Bian, R.; Li, L.; Pan, G.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Biochar’s effect on crop productivity and the dependence on experimental conditions—A meta-analysis of literature data. Plant Soil 2013, 373, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Mei, K.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Zhang, M. Response of N2O emission to manure application in field trials of agricultural soils across the globe. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 733, 139390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loaiza, S.; Verchot, L.; Valencia, D.; Guzmán, P.; Amezquita, N.; Garcés, G.; Puentes, O.; Trujillo, C.; Chirinda, N.; Pittelkow, C.M. Evaluating greenhouse gas mitigation through alternate wetting and drying irrigation in Colombian rice production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2024, 360, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaine, N.; Carrijo, D.R.; Adviento-Borbe, M.A.; Linquist, B. Greenhouse gases from irrigated rice systems under varying severity of alternate-wetting and drying irrigation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Sereenonchai, S.; Uttarotai, T. Effects of soil texture on microbial community composition and abundance under alternate wetting and drying in paddy soils of central Thailand. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh-Toosi, A.; Clough, T.J.; Condron, L.M.; Sherlock, R.R.; Anderson, C.R.; Craigie, R.A. Biochar incorporation into pasture soil suppresses in situ nitrous oxide emissions from ruminant urine patches. J. Environ. Qual. 2011, 40, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Oh, J.H.; Kim, P.J. Evaluation of silicate iron slag amendment on reducing methane emission from flood water rice farming. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 128, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Kim, P.J. Silicate fertilization in no-tillage rice farming for mitigation of methane emission and increasing rice productivity. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 132, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreye, C.; Dittert, K.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, S.; Tao, H.; Sattelmacher, B. Fluxes of methane and nitrous oxide in water-saving rice production in North China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2007, 77, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R. Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia 1989, 78, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, A.; Sakuma, H.; Sudo, E.; Mae, T. Differences between maize and rice in N-use efficiency for photosynthesis and protein allocation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 952–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, N.G.; Attard, R.D.; Ghannoum, O.; Lewis, J.D.; Logan, B.A.; Tissue, D.T. Impact of variable [CO2] and temperature on water transport structure–function relationships in Eucalyptus. Tree Physiol. 2011, 31, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Smith, P.; Martino, D.; Cai, Z.; Gwary, D.; Janzen, H.; Kumar, P.; McCarl, B.; Ogle, S.; O’Mara, F.; Rice, C.; et al. Greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 789–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agegnehu, G.; Bass, A.M.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Benefits of biochar, compost and biochar–compost for soil quality, maize yield and greenhouse gas emissions in tropical agricultural soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 543, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. (Eds.) Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan EPA. Taiwan’s Net-Zero Emissions Pathway; Environmental Protection Administration, Executive Yuan: Taipei, Taiwan, 2022. Available online: https://www.ndc.gov.tw/en/Content_List.aspx?n=B666BCFA2C722230 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Griscom, B.W.; Adams, J.; Ellis, P.W.; Houghton, R.A.; Lomax, G.; Miteva, D.A.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Shoch, D.; Siikamäki, J.V.; Smith, P.; et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11645–11650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).