A Review of Recent Advances in Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials for CO2 Capture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Collection and Methodology

3. Overview of CO2 Capture Mechanisms by Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials

4. Feedstocks and Preparation Techniques of Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials

4.1. Biomass Feedstocks

4.2. Biomass Carbonization Techniques

4.2.1. Pyrolysis

4.2.2. Hydrothermal Carbonization

4.2.3. Comparison of Carbonization Techniques and Biomass Feedstock Suitability

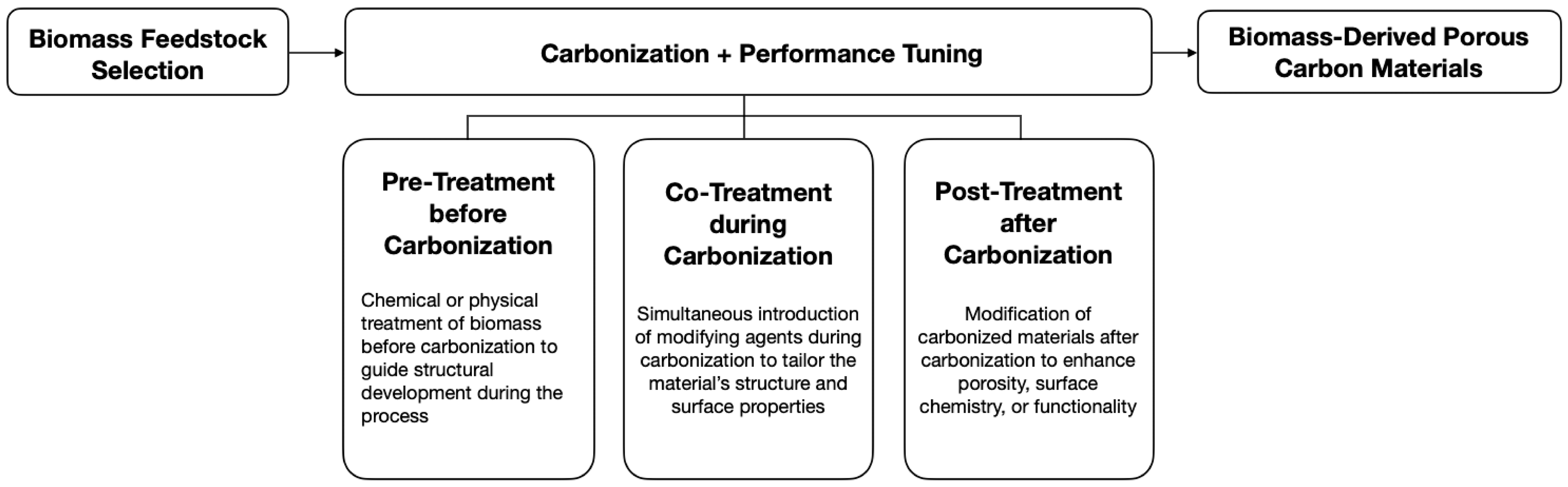

4.3. Performance Tuning Techniques for Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials

4.3.1. Activation

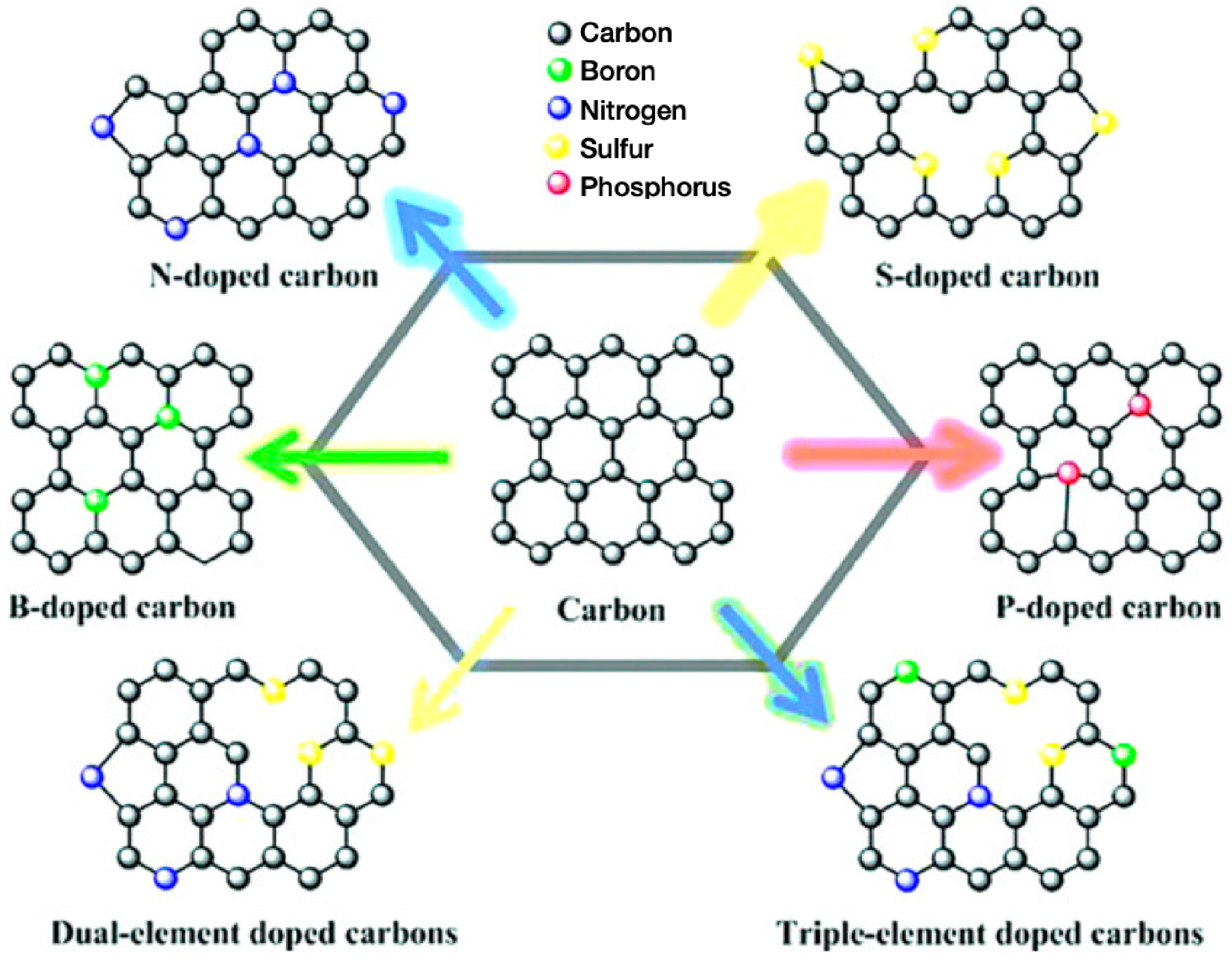

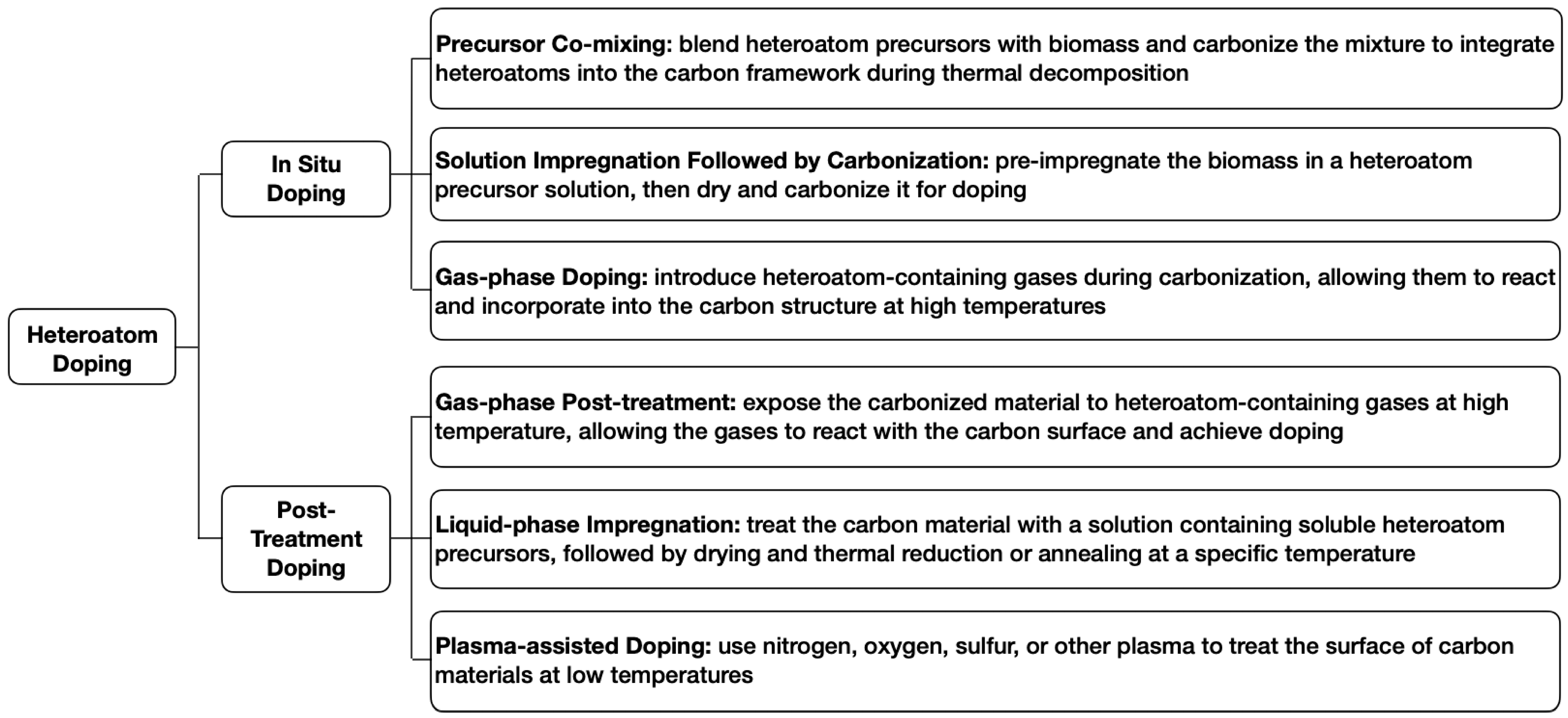

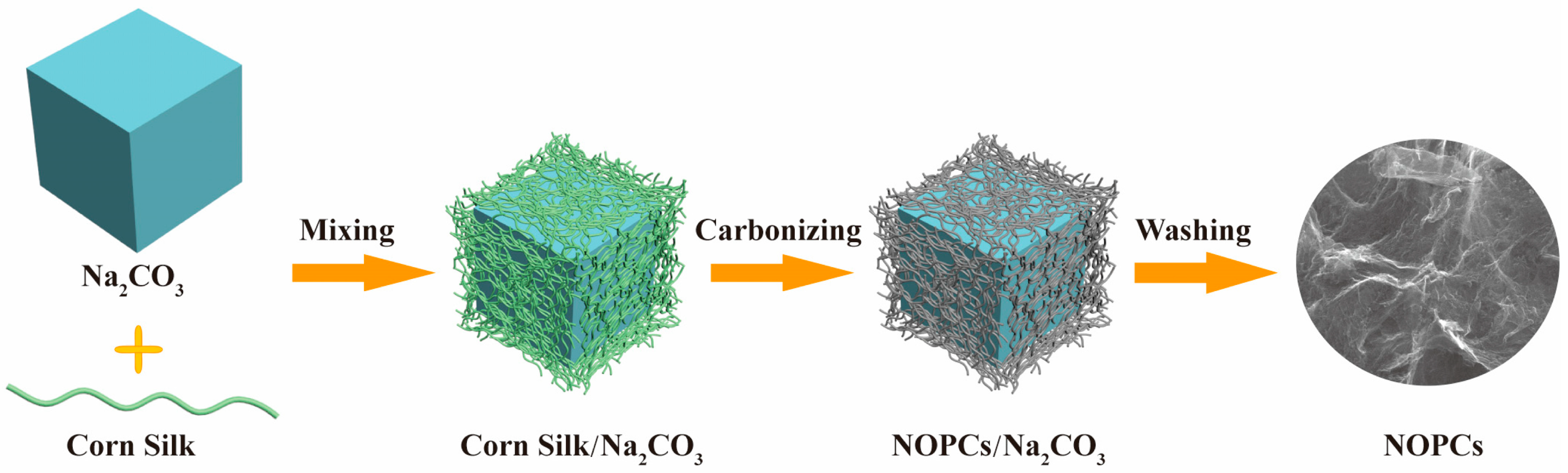

4.3.2. Heteroatom Doping

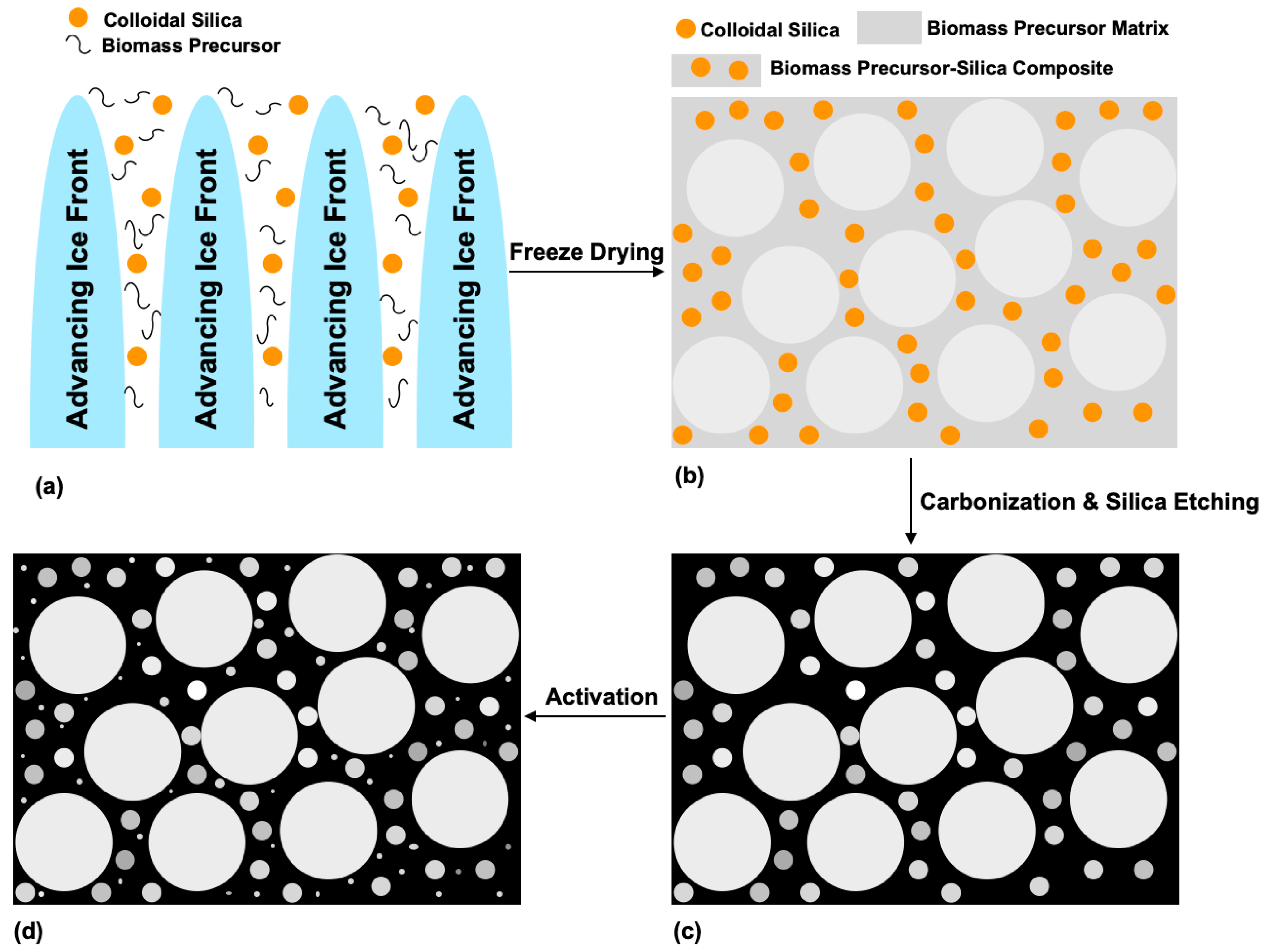

4.3.3. Templating

4.3.4. Comparison of Performance Tuning Strategies

5. Typical Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials and Research Progress

5.1. Activated Carbons

5.1.1. Conventional Activated Carbons

5.1.2. Nanoporous Activated Carbons

5.1.3. Functionalized Activated Carbons

5.2. Hierarchical Porous Carbon Materials

5.3. Other Innovative Carbon Materials

5.3.1. Functionally Enhanced Biomass-Derived Carbons

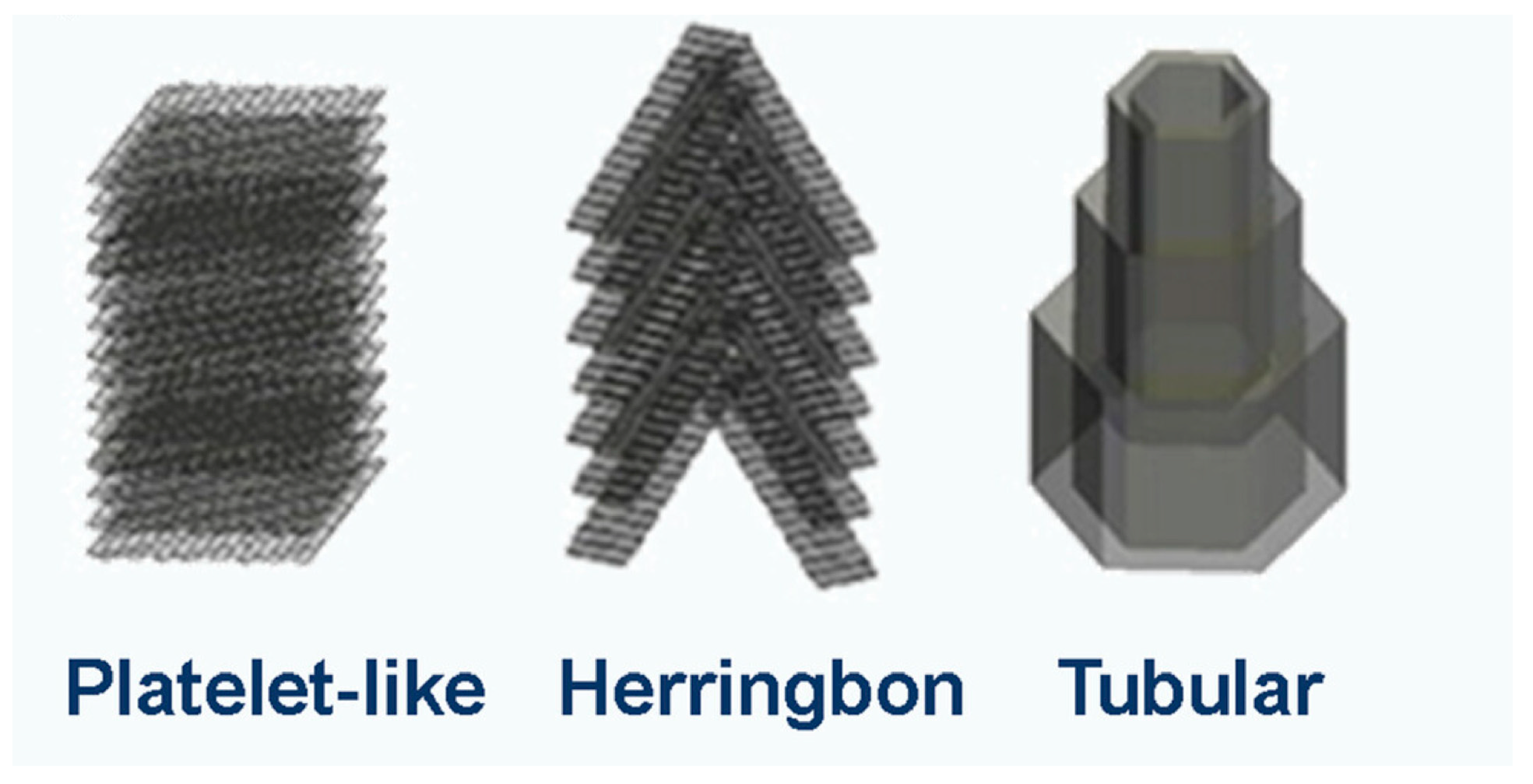

5.3.2. Morphologically Engineered Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials

5.3.3. Carbon Materials Integrating Functional and Morphological Innovations

6. Challenges and Future Directions

6.1. Technical Challenges and Prospects

6.2. Industrial and Economic Barriers to Scale-Up and Techno-Economic Assessment

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nunes, L.J.R. The Rising Threat of Atmospheric CO2: A Review on the Causes, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Environments 2023, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, M.; Tyagi, B. Terrestrial Carbon Cycle: Tipping Edge of Climate Change Between the Atmosphere and Biosphere Ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2022, 2, 867–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J.F.; Huntingford, C.; Williamson, M.S.; Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Boulton, C.A.; Buxton, J.E.; Sakschewski, B.; Loriani, S.; Zimm, C.; Winkelmann, R.; et al. Committed Global Warming Risks Triggering Multiple Climate Tipping Points. Earths Future 2023, 11, e2022EF003250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickfeld, K.; MacIsaac, A.J.; Canadell, J.G.; Fuss, S.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, C.D.; Lohila, A.; Matthews, H.D.; Peters, G.P.; Rogelj, J.; et al. Net-Zero Approaches Must Consider Earth System Impacts to Achieve Climate Goals. Nat. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Li, J.; Tang, X.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Ge, Z.; Yuan, F. Coal-Fired Power Plant CCUS Project Comprehensive Benefit Evaluation and Forecasting Model Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mon, M.T.; Tansuchat, R.; Yamaka, W. CCUS Technology and Carbon Emissions: Evidence from the United States. Energies 2024, 17, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yan, G.; Kong, S.; Yao, J.; Wen, P.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Suppression of Anthracite Dust by a Composite of Oppositely-Charged Ionic Surfactants with Ultra-High Surface Activity: Theoretical Calculation and Experiments. Fuel 2023, 344, 128075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Yan, G.; Kong, S.; Yang, T.; Yao, J.; Wen, P.; Li, G. Study on the Mechanism of the Influence of Surfactant Alkyl Chain Length on the Wettability of Anthracite Dust Based on EDLVO Theory and Inverse Gas Chromatography. Fuel 2023, 353, 129187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Li, G.; Wu, J. Application of In-Situ Combustion for Heavy Oil Production in China: A Review. J. Oil Gas Petrochem. Sci. 2018, 1, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yao, J. A Review of In Situ Leaching (ISL) for Uranium Mining. Mining 2024, 4, 120–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Song, Y. Dynamic Analysis Approach to Evaluate In-Situ Combustion Performance for Heavy Oil Production. J. Oil Gas Petrochem. Sci. 2019, 2, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschiv, S.; Paraschiv, L.S. Trends of Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions from Fossil Fuels Combustion (Coal, Gas and Oil) in the EU Member States from 1960 to 2018. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maka, A.O.M.; Alabid, J.M. Solar Energy Technology and Its Roles in Sustainable Development. Clean. Energy 2022, 6, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Arsalan, M.H. Solar Power Technologies for Sustainable Electricity Generation—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Hydrogen from Solar Energy, a Clean Energy Carrier from a Sustainable Source of Energy. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 4110–4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavner, P. Wind Power as a Clean-Energy Contributor. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4397–4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, D. A Review of Multiphase Energy Conversion in Wind Power Generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wu, L.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, R. Strategies for Effectively Harvesting Wind Energy Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2022, 100, 107522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Gao, Q.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.L.; Cheng, T. Optimization Strategy of Wind Energy Harvesting via Triboelectric-Electromagnetic Flexible Cooperation. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, H.; Dai, L.; Liu, M.; Xiao, Y.; Cong, T.; Gu, H. The Role of Nuclear Energy in the Carbon Neutrality Goal. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 162, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yao, J.; Song, Y.; Tang, J.; Han, H.; Cui, X. A Review of the Metallogenic Mechanisms of Sandstone-Type Uranium Deposits in Hydrocarbon-Bearing Basins in China. Eng 2023, 4, 1723–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Peluzo, B.M.T.; Kraka, E. Uranium: The Nuclear Fuel Cycle and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storrs, K.; Lyhne, I.; Drustrup, R. A Comprehensive Framework for Feasibility of CCUS Deployment: A Meta-Review of Literature on Factors Impacting CCUS Deployment. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2023, 125, 103878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Vishal, V.; Garg, A. CCUS in India: Bridging the Gap Between Action and Ambition. Prog. Energy 2024, 6, 023004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Han, H.; Yang, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, G. A Review of Recent Progress of Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) in China. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yao, J. Direct Air Capture (DAC) for Achieving Net-Zero CO2 Emissions: Advances, Applications, and Challenges. Eng 2024, 5, 1298–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachola, C.d.S.; Ciotta, M.; Azevedo dos Santos, A.; Peyerl, D. Deploying of the Carbon Capture Technologies for CO2 Emission Mitigation in the Industrial Sectors. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 7, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltsev, S.; Morris, J.; Kheshgi, H.; Herzog, H. Hard-to-Abate Sectors: The Role of Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) in Emission Mitigation. Appl. Energy 2021, 300, 117322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cao, X.; Luo, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wu, F. Prospects of Magnesium-Based Adsorbents in Pre-Combustion CO2 Capture: A Review from Laboratory Preparation to Scale-Up Application Exploration. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 21085–21124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Wen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zou, J.; Emami-Meybodi, H.; Zeng, F.; Dindoruk, B. Conformance Control Design for CO2 Geological Utilization and Storage with Case Studies in Yanchang and Shengli CCUS Pilot Projects. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 254, 214056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Rui, Z.-H.; Liu, Y.-L.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, J.-R.; Khan, W.A.; Du, K. Characterization of CO2 Transport in Low-Permeability Reservoirs Using Low-Field Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance and Mass-Transfer Theory: Experimental Applications on Evaluation of CO2 Sequestration. SPE J. 2025, 30, 6511–6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H.; Huang, X.; Rui, Z.; Zou, J.; Afanasyev, A. Bio-Based Materials Regulating Interfacial Behavior of Multiphase Systems During CO2 Geological Utilization and Storage: A Review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 346, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; He, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y. CO2 Leakage in Geologic Carbon Storage: A Review of Its Impacts and Detection. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rui, Z. A Storage-Driven CO2 EOR for a Net-Zero Emission Target. Engineering 2022, 18, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rui, Z.; Yang, T.; Dindoruk, B. Using Propanol as an Additive to CO2 for Improving CO2 Utilization and Storage in Oil Reservoirs. Appl. Energy 2022, 311, 118640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, M.; Xu, G.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, T.; Yang, G.; Pan, L. Machine Learning-Guided Prediction of Desalination Capacity and Rate of Porous Carbons for Capacitive Deionization. Small 2024, 20, e2401214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gong, Y.; Li, D.; Pan, C. Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials: Synthesis, Designing, and Applications for Supercapacitors. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 3864–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardene, O.H.P.; Gunathilake, C.A.; Vikrant, K.; Amaraweera, S.M. Carbon Dioxide Capture Through Physical and Chemical Adsorption Using Porous Carbon Materials: A Review. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, G.; Yin, H.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, H.; An, T. Adsorption and Desorption Mechanism of Aromatic VOCs onto Porous Carbon Adsorbents for Emission Control and Resource Recovery: Recent Progress and Challenges. Environ. Sci. Nano 2022, 9, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.-L.; Zhang, H.; Shao, L.-M.; Lü, F.; He, P.-J. Preparation and Application of Hierarchical Porous Carbon Materials from Waste and Biomass: A Review. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 1699–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Fei, J.; Zhou, J.; Shan, S.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, S. Highly Efficient Removal of Quinolones by Using the Easily Reusable MOF Derived-Carbon. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ren, P.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Jia, D.; Wu, D. Coal Tar Pitch-Based Porous Carbon: Synthetic Strategies and Their Applications in Energy Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e04092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisheh, H.; Abdin, Y. Carbon Fibers: From PAN to Asphaltene Precursors; A State-of-Art Review. C 2023, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelnoor, N.; AlHajaj, A.; Khaleel, M.; Vega, L.F.; Abu-Zahra, M.R.M. Activated Carbons from Biomass-Based Sources for CO2 Capture Applications. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalak, T. Potential Use of Industrial Biomass Waste as a Sustainable Energy Source in the Future. Energies 2023, 16, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandaker, T.; Islam, T.; Nandi, A.; Anik, M.A.A.M.; Hossain, M.d.S.; Hasan, M.d.K.; Hossain, M.S. Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials for Sustainable Energy Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2025, 9, 693–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguib, H.M.; Hou, G. Exploitation of Natural and Recycled Biomass Resources to Get Eco-Friendly Polymer. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, T.R.; Nanda, S.; Meda, V.; Dalai, A.K. Densification of Waste Biomass for Manufacturing Solid Biofuel Pellets: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 231–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Bin Abu Sofian, A.D.A.; Chan, Y.J.; Chakrabarty, A.; Selvarajoo, A.; Abakr, Y.A.; Show, P.L. Hydrothermal Carbonization: Sustainable Pathways for Waste-To-Energy Conversion and Biocoal Production. GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematian, T.; Barati, M. Nanobiocatalytic Processes for Producing Biodiesel from Algae. In Sustainable Bioenergy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambo, S.A.; Abdulla, R.; Mohd Azhar, S.H.; Marbawi, H.; Gansau, J.A.; Ravindra, P. A Review on Third Generation Bioethanol Feedstock. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bušić, A.; Marđetko, N.; Kundas, S.; Morzak, G.; Belskaya, H.; Ivančić Šantek, M.; Komes, D.; Novak, S.; Šantek, B. Bioethanol Production from Renewable Raw Materials and Its Separation and Purification: A Review. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, F.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q.; Chang, J.-S.; Ho, S.-H. Biohydrogen Production from Microalgae for Environmental Sustainability. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karishma, S.; Saravanan, A.; Senthil Kumar, P.; Rangasamy, G. Sustainable Production of Biohydrogen from Algae Biomass: Critical Review on Pretreatment Methods, Mechanism and Challenges. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 366, 128187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamusoko, R.; Jingura, R.M.; Chikwambi, Z.; Parawira, W. Biogas: Microbiological Research to Enhance Efficiency and Regulation. In Handbook of Biofuels; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusweireh, R.S.; Rajamohan, N.; Sonne, C.; Vasseghian, Y. Algae Biogas Production Focusing on Operating Conditions and Conversion Mechanisms—A Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.; Monteiro, E.; Tabet, F.; Rouboa, A. Numerical Investigation of Optimum Operating Conditions for Syngas and Hydrogen Production from Biomass Gasification Using Aspen Plus. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.J.; Ong, H.C.; Gan, Y.Y.; Chen, W.-H.; Mahlia, T.M.I. State of Art Review on Conventional and Advanced Pyrolysis of Macroalgae and Microalgae for Biochar, Bio-Oil and Bio-Syngas Production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 210, 112707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, P.; Wang, P.; Chen, N.; Qian, B.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Dai, B. Functional Carbon from Nature: Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials and the Recent Progress of Their Applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2205557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makepa, D.C.; Chihobo, C.H. Sustainable Pathways for Biomass Production and Utilization in Carbon Capture and Storage—A Review. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2025, 15, 11397–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Xia, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, X.S. A Review on Biomass-Derived Hard Carbon Materials for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 5881–5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Suo, G.; Zhang, L.; Lu, S.; Chen, Z. Biomass-Derived Carbon for High-Performance Batteries: From Structure to Properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2201584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, A.; Zhu, H.; Ma, T. Recent Progress in Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials Used for Secondary Batteries. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 3017–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaiyan, P.; Dos Reis, G.S.; Karuppiah, D.; Subramaniyam, C.M.; García-Alvarado, F.; Lassi, U. Recent Progress in Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials for Li-Ion and Na-Ion Batteries—A Review. Batteries 2023, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cui, B.; Yin, P.; Zhang, C. Design and Preparation of Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials for Supercapacitors: A Review. C 2018, 4, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Kong, Q.; Cao, Y.; Sun, G.; Su, F.; Wei, X.; Li, X.; Ahmad, A.; Xie, L.; Chen, C.-M. Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Materials with Different Dimensions for Supercapacitor Electrodes: A Review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 16028–16045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, Y.-N.; Tang, W.; Yang, J.; Peng, C.; Guo, Z. Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials for High-Performance Supercapacitors: Current Status and Perspective. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2021, 4, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Dai, S.Y. Design of Biomass-Based Renewable Materials for Environmental Remediation. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Tan, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, M.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ye, S.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y. Biomass-Derived Porous Graphitic Carbon Materials for Energy and Environmental Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 5773–5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kaur, P.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Mustafa, M.A.; Rani, J.; Kaur, J.; Kaushal, S. Advances in Surface Modification of Biomass and Its Nanostructuring for Enhanced Environmental Remediation Applications. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 8774–8815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Mazzotti, M. Potential for Hydrogen Production from Sustainable Biomass with Carbon Capture and Storage. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 112123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yao, J. A Review of Algae-Based Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (Algae-Based CCUS). Gases 2024, 4, 468–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Muñoz, E.M.; García-Mateos, F.J.; Rosas, J.M.; Rodríguez-Mirasol, J.; Cordero, T. Biomass Waste Carbon Materials as Adsorbents for CO2 Capture under Post-Combustion Conditions. Front. Mater. 2016, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.B.; Hasan Johir, M.A.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Nghiem, L.D.; Richardson, C.; Moni, M.A.; Bryant, M.R. Activated Carbon Preparation from Biomass Feedstock: Clean Production and Carbon Dioxide Adsorption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, G.; Rehman, A.; Hussain, S.; Mahmood, Q.; Fteiti, M.; Heo, K.; Ikram, M.; Aizaz Ud Din, M. Towards a Sustainable Conversion of Biomass/Biowaste to Porous Carbons for CO2 Adsorption: Recent Advances, Current Challenges, and Future Directions. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 4941–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, L.d.S.; Moreira, B.R.d.A.; Viana, R.d.S.; Dias, E.S.; Rinker, D.L.; Pardo-Gimenez, A.; Zied, D.C. Spent Mushroom Substrate Is Capable of Physisorption-Chemisorption of CO2. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, B. Understanding the Role of Noncovalent Interactions in Gas Sensing with Metal-Coordinated Complexes (MCCs). Top. Curr. Chem. 2025, 383, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEnaney, B. Adsorption and Structure in Microporous Carbons. Carbon 1988, 26, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W. The Use of Gas Adsorption for the Characterization of Porous Solids. Colloids Surf. 1989, 38, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkov, B.; Čermák, J.; Šefara, M.; Janků, J. Pore Classification in the Characterization of Porous Materials: A Perspective. Open Chem. 2007, 5, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Shi, X.; Wang, C.; Gao, Y.; Xu, S.; Hao, G.; Chen, S.; Lu, A. Advances in Post-Combustion CO2 Capture by Physical Adsorption: From Materials Innovation to Separation Practice. ChemSusChem 2021, 14, 1428–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.H.; Bhown, A.S. Comparing Physisorption and Chemisorption Solid Sorbents for Use Separating CO2 from Flue Gas Using Temperature Swing Adsorption. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.; Mondragón, F.; Truong, T.N. CO2 Adsorption on Carbonaceous Surfaces: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Study. Carbon 2003, 41, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovic, L.R. The Mechanism of CO2 Chemisorption on Zigzag Carbon Active Sites: A Computational Chemistry Study. Carbon 2005, 43, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorantla, K.R.; Mallik, B.S. Reaction Mechanism and Free Energy Barriers for the Chemisorption of CO2 by Ionic Entities. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrota, A.S.; PaÅ¡ti, I.A. Chemisorption as the Essential Step in Electrochemical Energy Conversion—Review. J. Electrochem. Sci. Eng. 2020, 10, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.A.; Byun, J.; Yavuz, C.T. Carbon Dioxide Capture Adsorbents: Chemistry and Methods. ChemSusChem 2017, 10, 1303–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Basu, J.K.; Das, G. A Novel Gas–Liquid Contactor for Chemisorption of CO2. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 94, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Hu, T.; Xie, R.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Yao, K.; Shan, S. Dual Synergistic Effect of the Amine-Functionalized MIL-101@cellulose Sorbents for Enhanced CO2 Capture at Ambient Temperature. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, L.; Li, B.; Xiong, J.; Wei, G.; Yang, X.; Li, M.; Peng, S.; Liu, H. Synergistic Strategy of Physical and Chemical Adsorption on Nanofeather-Like Amino Adsorbents for Stable and Efficient CO2 Capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 370, 133239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zeng, Y.; Hou, Y.; Cai, Q.; Liu, Q.; Shen, B.; Ma, X. CO2 Adsorption on N-Doped Porous Biocarbon Synthesized from Biomass Corncobs in Simulated Flue Gas. Langmuir 2023, 39, 7566–7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phromphithak, S.; Onsree, T.; Shariati, K.; Drummond, S.; Katongtung, T.; Tippayawong, N.; Naglic, J.; Lauterbach, J. Low-Transition Temperature Mixtures Pretreatment and Hydrothermal Carbonization of Corncob Residues for CO2 Capture Materials. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Xin, C.; Kong, X.; Hu, X.; Guo, Q. The Development of Activated Carbon from Corncob for CO2 Capture. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 33069–33078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, W.; Wang, R.; Ding, F.; Hong, P.; Gao, B. Straw and Wood Based Biochar for CO2 Capture: Adsorption Performance and Governing Mechanisms. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 287, 120592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, H. A Facile and Low-Cost Route to Heteroatom Doped Porous Carbon Derived from Broussonetia Papyrifera Bark with Excellent Supercapacitance and CO2 Capture Performance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Weldekidan, H.; Mohanty, A.; Misra, M. Effect of Physicochemical Activation on CO2 Adsorption of Activated Porous Carbon Derived from Pine Sawdust. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foorginezhad, S.; Zerafat, M.M.; Asadnia, M.; Rezvannasab, G. Activated Porous Carbon Derived from Sawdust for CO2 Capture. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 317, 129177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjumon, J.; Maria Ruban, A.; Kaur, H.; Sajan, D.; Mahasivam, S.; Bansal, V.; Singh, G.; Vinu, A. Functionalized Nanoporous Biocarbon with High Specific Surface Area Derived from Waste Hardwood Chips for CO2 Capture and Supercapacitors. Small Sci. 2025, 5, 2500174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Diaz de Tuesta, J.L.; Gonçalves, C.N.D.P.; Gomes, H.T.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Silva, J.A.C. Compost from Municipal Solid Wastes as a Source of Biochar for CO2 Capture. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2020, 43, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherymoosavi, S.; Verheyen, V.; Munroe, P.; Joseph, S.; Reynolds, A. Characterization of Organic Compounds in Biochars Derived from Municipal Solid Waste. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, V.; Ashiq, A.; Ramanayaka, S.; Wijekoon, P.; Vithanage, M. Biochar from Municipal Solid Waste for Resource Recovery and Pollution Remediation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2019, 17, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Falco, C.; Titirici, M.-M.; Fuertes, A.B. High-Performance CO2 Sorbents from Algae. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Yan, Q. In-Situ Pyrolysis of Taihu Blue Algae Biomass as Appealing Porous Carbon Adsorbent for CO2 Capture: Role of the Intrinsic N. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, X.; Cai, J. The Direct Carbonization of Algae Biomass to Hierarchical Porous Carbons and CO2 Adsorption Properties. Mater. Lett. 2016, 180, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Neelima, T.K.; Archana, T.M. Renewable Functional Materials Derived from Animal Wastes and Organic Garbage Waste to Wealth—A Green Innovation in Biomass Circular Bioeconomy. In Handbook of Advanced Biomass Materials for Environmental Remediation; Materials Horizons: From Nature to Nanomaterials; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, A.; Gaur, V.K.; Rawat, N.; Wankhade, P.R.; Gaur, G.K.; Awasthi, M.K.; Sagar, N.A.; Sirohi, R. Advances in Biomaterial Production from Animal Derived Waste. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 8247–8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Luo, J.; Huo, L.; Zhao, L.; Yao, Z. Straw-Derived Porous Biochars by Ball Milling for CO2 Capture: Adsorption Performance and Enhanced Mechanisms. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 229, 121000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Baquy, M.A.-A.; Nkoh Nkoh, J.; Hoque, M.d.R.; Li, J.; Naser, H.M.; Moniruzzaman, M. Evaluating the Potential of Different Crop Straw Biochar to Capture Carbon Dioxide and Increase the Growth of Zea mays L. Discov. Soil 2024, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boujibar, O.; Souikny, A.; Ghamouss, F.; Achak, O.; Dahbi, M.; Chafik, T. CO2 Capture Using N-Containing Nanoporous Activated Carbon Obtained from Argan Fruit Shells. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, L.B.; Fiuza, R.A.; de Andrade, R.C.; Andrade, H.M.C. CO2 Capture on Activated Carbons Derived from Mango Fruit (Mangifera indica L.) Seed Shells. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2018, 131, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aimikhe, V.J.; Anyebe, M.S.; Ibezim-Ezeani, M. Development of Composite Activated Carbon from Mango and Almond Seed Shells for CO2 Capture. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2024, 14, 4645–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogungbenro, A.E.; Quang, D.V.; Al-Ali, K.A.; Vega, L.F.; Abu-Zahra, M.R.M. Physical Synthesis and Characterization of Activated Carbon from Date Seeds for CO2 Capture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 4245–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Li, Q.; Demir, M.; Yu, Q.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, L. Lotus Seed Pot-Derived Nitrogen Enriched Porous Carbon for CO2 Capture Application. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 655, 130226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazmi, A.; Nicolae, S.A.; Modugno, P.; Hasanov, B.E.; Titirici, M.M.; Costa, P.M.F.J. Activated Carbon from Palm Date Seeds for CO2 Capture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo, V.; Alfè, M.; Raganati, F.; Zhumagaliyeva, A.; Doszhanov, Y.; Ammendola, P.; Chirone, R. CO2 Adsorption Under Dynamic Conditions: An Overview on Rice Husk-Derived Sorbents and Other Materials. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2019, 191, 1484–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xiao, R. Preparation of a Dual Pore Structure Activated Carbon from Rice Husk Char as an Adsorbent for CO2 Capture. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 186, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murge, P.; Dinda, S.; Roy, S. Adsorbent from Rice Husk for CO2 Capture: Synthesis, Characterization, and Optimization of Parameters. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 10786–10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobele, G.; Dizhbite, T.; Gil, M.V.; Volperts, A.; Centeno, T.A. Production of Nanoporous Carbons from Wood Processing Wastes and Their Use in Supercapacitors and CO2 Capture. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 46, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhan, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Xu, Y. Preparation of Activated Carbon Through the Pyrolysis of Waste Bamboo Chips and Evaluation of Its CO2 Adsorption Efficacy. Biomass Convers. Biorefin 2025, 15, 10553–10565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Su, R.; Gao, N. Preparation of Activated Biomass Carbon from Pine Sawdust for Supercapacitor and CO2 Capture. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 4335–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Chen, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Fan, M. Heteroatom Self-Doped Activated Biocarbons from Fir Bark and Their Excellent Performance for Carbon Dioxide Adsorption. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 25, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Elsayed, I.; Song, X.; Shmulsky, R.; Hassan, E.B. Microporous Carbon Nanoflakes Derived from Biomass Cork Waste for CO2 Capture. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 142465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, T.-H.; Wong, J.W.C. A Critical Review: Emerging Bioeconomy and Waste-To-Energy Technologies for Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Management. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2019, 1, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D.; Pires, J.C.M. Atmospheric CO2 Capture by Algae: Negative Carbon Dioxide Emission Path. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwer, A.; Hamed, S.M.; Osman, A.I.; Jamil, F.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; Alhajeri, N.S.; Rooney, D.W. Algal Biomass Valorization for Biofuel Production and Carbon Sequestration: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 2797–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Gao, N. Biomass-Based Carbon Materials for CO2 Capture: A Review. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 68, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fang, Y.; Yang, H.; Xin, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. Effect of Volatiles Interaction During Pyrolysis of Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin at Different Temperatures. Fuel 2019, 248, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, M.; Chen, Y.; Xin, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, H. Vapor–Solid Interaction Among Cellulose, Hemicellulose and Lignin. Fuel 2020, 263, 116681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Le, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Pan, T. Free Radical Reaction Mechanism on Improving Tar Yield and Quality Derived from Lignite After Hydrothermal Treatment. Fuel 2017, 207, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibet, J.; Khachatryan, L.; Dellinger, B. Molecular Products and Radicals from Pyrolysis of Lignin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12994–13001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizani, C.; Escudero Sanz, F.J.; Salvador, S. Effects of CO2 on Biomass Fast Pyrolysis: Reaction Rate, Gas Yields and Char Reactive Properties. Fuel 2014, 116, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.d.N.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Abbas, H.F. Effects of Pyrolysis Parameters on Hydrogen Formations from Biomass: A Review. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 10467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas e Silva, F.; Monteggia, L.O. Pyrolysis of Algal Biomass Obtained from High-Rate Algae Ponds Applied to Wastewater Treatment. Front. Energy Res. 2015, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, H. Review of Reactions and Molecular Mechanisms in Cellulose Pyrolysis. Curr. Org. Chem. 2016, 20, 2444–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, H. Lignin Pyrolysis Reactions. J. Wood Sci. 2017, 63, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppaladadiyam, A.K.; Vuppaladadiyam, S.S.V.; Awasthi, A.; Sahoo, A.; Rehman, S.; Pant, K.K.; Murugavelh, S.; Huang, Q.; Anthony, E.; Fennel, P.; et al. Biomass Pyrolysis: A Review on Recent Advancements and Green Hydrogen Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; Xiao, R.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z. Influence of Temperature and Residence Time on Characteristics of Biochars Derived from Agricultural Residues: A Comprehensive Evaluation. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2020, 139, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motasemi, F.; Afzal, M.T. A Review on the Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis Technique. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethaib, S.; Omar, R.; Kamal, S.M.M.; Awang Biak, D.R.; Zubaidi, S.L. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Biomass Waste: A Mini Review. Processes 2020, 8, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Budarin, V.L.; Gronnow, M.J.; De Bruyn, M.; Onwudili, J.A.; Clark, J.H.; Williams, P.T. Conventional and Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Biomass Under Different Heating Rates. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2014, 107, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez, J.A.; Arenillas, A.; Fidalgo, B.; Fernández, Y.; Zubizarreta, L.; Calvo, E.G.; Bermúdez, J.M. Microwave Heating Processes Involving Carbon Materials. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Yue, Q. Review on Microwave-Matter Interaction Fundamentals and Efficient Microwave-Associated Heating Strategies. Materials 2016, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaskin, M.S.; Kumar, V. Assessing the Effectiveness of the Hydrothermal Carbonization Method to Produce Bio-Coal from Wet Organic Wastes. Therm. Eng. 2020, 67, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, S.Z.; Zainudin, S.F.; Mohd Aris, A.; Chin, K.B.; Musa, M.; Mohamad Daud, A.R.; Syed Hassan, S.S.A. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Sewage Sludge into Solid Biofuel: Influences of Process Conditions on the Energetic Properties of Hydrochar. Energies 2023, 16, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. A Review of the Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass Waste for Hydrochar Formation: Process Conditions, Fundamentals, and Physicochemical Properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhan, L.; Ok, Y.S.; Gao, B. Minireview of Potential Applications of Hydrochar Derived from Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 57, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal-Uddin, A.-T.; Reza, M.T.; Norouzi, O.; Salaudeen, S.A.; Dutta, A.; Zytner, R.G. Recovery and Reuse of Valuable Chemicals Derived from Hydrothermal Carbonization Process Liquid. Energies 2023, 16, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranja, M.J.; da Silva, R.C.J.; Bisinoti, M.C.; Moreira, A.B.; Ferreira, O.P.; Melo, C.A. Semivolatile Organic Compounds in the Products from Hydrothermal Carbonisation of Sugar Cane Bagasse and Vinasse by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 12, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jia, J.; Jin, Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Yin, Q.; Zhao, Z. Forming Mechanism of Coke Microparticles from Polymerization of Aqueous Organics During Hydrothermal Carbonization Process of Biomass. Carbon 2022, 192, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Khandaker, T.; Anik, M.A.-A.M.; Hasan, M.d.K.; Dhar, P.K.; Dutta, S.K.; Latif, M.A.; Hossain, M.S. A Comprehensive Review of Enhanced CO2 Capture Using Activated Carbon Derived from Biomass Feedstock. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 29693–29736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Liu, Q.; He, X.; Wang, G.; Chen, N.; Peng, J.; Ma, L. Molecular Structure and Formation Mechanism of Hydrochar from Hydrothermal Carbonization of Carbohydrates. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 9904–9915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyatnyk, I.; Yakupova, I. Impact of Chemical and Physical Treatments on the Structural and Surface Properties of Activated Carbon and Hydrochar. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 2500–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Luo, L.; Liu, Z.; Miao, W.; Xia, Y. A Critical Review of Hydrochar Based Photocatalysts by Hydrothermal Carbonization: Synthesis, Mechanisms, and Applications. Biochar 2024, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Akaeme, F.C.; Georgin, J.; de Oliveira, J.S.; Franco, D.S.P. Biomass Hydrochar: A Critical Review of Process Chemistry, Synthesis Methodology, and Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Li, F.; Fang, D.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, H.; Pan, B. Effects of Hydrophobic Coating on Properties of Hydrochar Produced at Different Temperatures: Specific Surface Area and Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, K.; Ghaemi, A. A Comprehensive Review of the Physicochemical Properties and Performance of Novel Carbon-Based Adsorbents for CO2 Capture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 20248–20287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, P.T.; Reed, A.R. Development of Activated Carbon Pore Structure via Physical and Chemical Activation of Biomass Fibre Waste. Biomass Bioenergy 2006, 30, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergova, K.; Eser, S. Effects of Activation Method on the Pore Structure of Activated Carbons from Apricot Stones. Carbon 1996, 34, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould-Idriss, A.; Stitou, M.; Cuerda-Correa, E.M.; Fernández-González, C.; Macías-García, A.; Alexandre-Franco, M.F.; Gómez-Serrano, V. Preparation of Activated Carbons from Olive-Tree Wood Revisited. II. Physical Activation with Air. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Walawender, W.P.; Fan, L.T.; Fan, M.; Daugaard, D.; Brown, R.C. Preparation of Activated Carbon from Forest and Agricultural Residues Through CO2 Activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2004, 105, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuong, D.A.; Nguyen, H.N.; Tsubota, T. Activated Carbon Produced from Bamboo and Solid Residue by CO2 Activation Utilized as CO2 Adsorbents. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 148, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Peng, J.; Li, W.; Yang, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Xia, H. Effects of CO2 Activation on Porous Structures of Coconut Shell-Based Activated Carbons. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 8443–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J.; Xing, Z.-J.; Duan, Z.-K.; Meng, L.; Wang, Y. Effects of Steam Activation on the Pore Structure and Surface Chemistry of Activated Carbon Derived from Bamboo Waste. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 315, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, S.; González, J.F.; González-García, C.M.; Zamora, F. Control of Pore Development During CO2 and Steam Activation of Olive Stones. Fuel Process. Technol. 2008, 89, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, G.S.; Fowler, G.D.; Sollars, C.J. A Study of the Characteristics of Activated Carbons Produced by Steam and Carbon Dioxide Activation of Waste Tyre Rubber. Carbon 2003, 41, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Luo, A.; Zhao, Y. Preparation and Characterisation of Activated Carbon from Waste Tea by Physical Activation Using Steam. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2018, 68, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oginni, O.; Singh, K.; Oporto, G.; Dawson-Andoh, B.; McDonald, L.; Sabolsky, E. Influence of One-Step and Two-Step KOH Activation on Activated Carbon Characteristics. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, B.; Zubatiuk, T.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J.; Chen, W.Y. Chemical Activation of Biochar for Energy and Environmental Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2019, 35, 777–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Rockstraw, D.A. Activated Carbons Prepared from Rice Hull by One-Step Phosphoric Acid Activation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2007, 100, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakout, S.M.; Sharaf El-Deen, G. Characterization of Activated Carbon Prepared by Phosphoric Acid Activation of Olive Stones. Arab. J. Chem. 2016, 9, S1155–S1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadoun, H.; Sadaoui, Z.; Souami, N.; Sahel, D.; Toumert, I. Characterization of Mesoporous Carbon Prepared from Date Stems by H3PO4 Chemical Activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 280, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Sabio, M.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Role of Chemical Activation in the Development of Carbon Porosity. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2004, 241, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Ródenas, M.A.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Linares-Solano, A. Understanding Chemical Reactions Between Carbons and NaOH and KOH. Carbon 2003, 41, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrvarz, E.; Ghoreyshi, A.A.; Jahanshahi, M. Surface Modification of Broom Sorghum-Based Activated Carbon via Functionalization with Triethylenetetramine and Urea for CO2 Capture Enhancement. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2017, 11, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Geng, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Gao, B.; Zhang, X.; Chu, P.K.; et al. Redefining the Roles of Alkali Activators for Porous Carbon. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 2034–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Yin, B.; Akbar, A.; Li, W.-W.; Dai, Y.; Liew, K.M. Nano-Micro Pore Structure Characteristics of Carbon Black and Recycled Carbon Fiber Reinforced Alkali-Activated Materials. npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, E.; Shah, S.A.; Shah, S.N.A. Chloride Salt-Activated Carbon for Supercapacitors. In Biomass-Based Supercapacitors; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Liu, X.; Diao, R.; Qi, F.; Ma, P. Structural Regulation of Ultra-Microporous Biomass-Derived Carbon Materials Induced by Molten Salt Synergistic Activation and Its Application in CO2 Capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tang, J.; Xie, X.; Wei, J.; Xu, D.; Shi, L.; Ding, K.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Zhang, S.; et al. Char Structure Evolution During Molten Salt Pyrolysis of Biomass: Effect of Temperature. Fuel 2023, 331, 125747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, H.; Lin, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, P.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, J.; Cui, H. Advances in Micro-/Mesopore Regulation Methods for Plant-Derived Carbon Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, M.; Hashim, R.; Ibrahim, M.N.M.; Sulaiman, O. Effect of Acidic Activating Agents on Surface Area and Surface Functional Groups of Activated Carbons Produced from Acacia Mangium Wood. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2013, 104, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toles, C.A.; Marshall, W.E.; Johns, M.M. Surface Functional Groups on Acid-Activated Nutshell Carbons. Carbon 1999, 37, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Su, C.; Liu, B.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, K.; Zeng, Z.; Li, L. Heteroatom-Doped Porous Carbons Exhibit Superior CO2 Capture and CO2/N2 Selectivity: Understanding the Contribution of Functional Groups and Pore Structure. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 259, 118065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.B.; Devendiran, S.; Venkatesan Savunthari, K.; Arumugam, P.; Mukerjee, S. Multifarious Heteroatom-Doped/Enriched Carbon-Based Materials for Energy Storage Prospectives: A Crucial Insight. ChemRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M.; Tanaka, N.; Sakai, M.; Yamaguchi, S. Structurally Constrained Boron-, Nitrogen-, Silicon-, and Phosphorus-Centered Polycyclic π-Conjugated Systems. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8291–8331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Z.; Wang, X.; Tan, B. Porous Organic Polymers for CO2 Capture and Catalytic Conversion. Chem.—A Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202404089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, H.V.; Bai, M.G.M.; Rajeswara Rao, M. Functional π-Conjugated Two-Dimensional Covalent Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 11029–11060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, S.; Dai, Q.; Wang, H.; Wu, D.; Zhao, L.; Hu, C.; Dai, L. Heteroatom-Doped Carbon Materials for Multifunctional Noncatalytic Applications. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 29860–29897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajri, W.; De Luna, Y.; Bensalah, N. Review on Recent Applications of Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Materials in CO2 Capture and Energy Conversion and Storage. Energy Technol. 2022, 10, 2200498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, Z.; Guo, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Luo, H.; Dai, S. De Novo Fabrication of Multi-Heteroatom-Doped Carbonaceous Materials via an In Situ Doping Strategy. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 4740–4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xing, B.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. A High-Performance Biochar Produced from Bamboo Pyrolysis with In-Situ Nitrogen Doping and Activation for Adsorption of Phenol and Methylene Blue. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 2872–2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Jia, J. Dual-Doped Carbon Composite for Efficient Oxygen Reduction via Electrospinning and Incipient Impregnation. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Christodoulou, C.; Nardi, M.V.; Koch, N.; Sachdev, H.; Müllen, K. Chemical Vapor Deposition of N-Doped Graphene and Carbon Films: The Role of Precursors and Gas Phase. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 3337–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Xia, Q.X.; Wan, Z.; Yun, J.M.; Wang, Q.M.; Kim, K.H. Highly Porous Carbon Nanofoams Synthesized from Gas-Phase Plasma for Symmetric Supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 360, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podyacheva, O.; Korobova, A.; Yashnik, S.; Svintsitskiy, D.; Stonkus, O.; Sobolev, V.; Parmon, V. Tailored Synthesis of a Palladium Catalyst Supported on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanotubes for Gas-Phase Formic Acid Decomposition: A Strong Influence of a Way of Nitrogen Doping. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 134, 109771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Sánchez-Polo, M.; Gómez-Serrano, V.; Álvarez, P.M.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.C.M.; Dias, J.M. Activated Carbon Modifications to Enhance Its Water Treatment Applications. An Overview. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 187, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Fan, W. Nitrogen-Containing Porous Carbons: Synthesis and Application. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, X.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, J. Molten Salt Synthesis of Nitrogen-Doped Porous Carbons for Hydrogen Sulfide Adsorptive Removal. Carbon 2015, 95, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, G.A.K.M.R.; Jeong, J.-H. Porous Carbon for CO2 Capture Technology: Unveiling Fundamentals and Innovations. Surfaces 2023, 6, 316–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczęśniak, B.; Phuriragpitikhon, J.; Choma, J.; Jaroniec, M. Recent Advances in the Development and Applications of Biomass-Derived Carbons with Uniform Porosity. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 18464–18491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgras, V.; Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Kim, J.; Torad, N.L.; Dutta, S.; Ariga, K.; Hossain, M.d.S.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Wu, K.C.W. Fabrication of Nanoporous Carbon Materials with Hard- and Soft-Templating Approaches: A Review. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2019, 19, 3673–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Rudisill, S.G.; Petkovich, N.D. Perspective on the Influence of Interactions Between Hard and Soft Templates and Precursors on Morphology of Hierarchically Structured Porous Materials. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Bhaumik, A. Soft Templating Strategies for the Synthesis of Mesoporous Materials: Inorganic, Organic–Inorganic Hybrid and Purely Organic Solids. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 189–190, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenchom, L.; Kraehnert, R.; Smarsly, B.M. Recent Progress in Soft-Templating of Porous Carbon Materials. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yan, B.; Zheng, J.; Feng, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, T.; Chen, J.; Jiang, S.; Du, C.; et al. Recent Progress in Template-Assisted Synthesis of Porous Carbons for Supercapacitors. Adv. Powder Mater. 2022, 1, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, S.; Vojisavljevic, K.; Počuča-Nešić, M.; Zivojevic, K.; Mladenovic, M.; Knezevic, N. Hard Template Synthesis of Nanomaterials Based on Mesoporous Silica. Met. Mater. Eng. 2018, 24, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poolakkandy, R.R.; Menamparambath, M.M. Soft-Template-Assisted Synthesis: A Promising Approach for the Fabrication of Transition Metal Oxides. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 5015–5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Zhang, J.; Liu, A.; Zhu, G. Influence of Humidity on Adsorption Performance of Activated Carbon. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 416, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Hou, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W.; Fu, L.; Gao, X. Humidity Sensitivity Reducing of Moisture Swing Adsorbents by Hydrophobic Carrier Doping for CO2 Direct Air Capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolle, J.M.; Fayaz, M.; Sayari, A. Understanding the Effect of Water on CO2 Adsorption. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 7280–7345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.V.; Preuss, K.; Guo, Z.X.; Titirici, M.M. Understanding the Hydrophilicity and Water Adsorption Behavior of Nanoporous Nitrogen-Doped Carbons. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 18167–18179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xie, F.; Ullah, S.; Ma, L.; Teat, S.J.; Ma, S.; Thonhauser, T.; Tan, K.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Enhancing Carbon Dioxide Capture under Humid Conditions by Optimizing the Pore Surface Structure. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 32385–32395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemak, J.; Michalkiewicz, B. Enhancement of CO2 Adsorption on Activated Carbons Produced from Avocado Seeds by Combined Solvothermal Carbonization and Thermal KOH Activation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 40133–40141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, T.; Asrafali, S.P.; Kim, S.-C. Heteroatom-Enhanced Porous Carbon Materials Based on Polybenzoxazine for Supercapacitor Electrodes and CO2 Capture. Polymers 2023, 15, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhong, W.; Dong, W. Recent Advances in Biomass-Derived Porous Carbons for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture: From Preparation and Adsorption Mechanisms to Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 520, 165890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raganati, F.; Miccio, F.; Ammendola, P. Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide for Post-Combustion Capture: A Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 12845–12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ospino, R.; Reinert, L.; Izquierdo, M.T.; Celzard, A.; Duclaux, L.; Fierro, V. Challenges and Insights in CO2 Adsorption Using N-Doped Carbons under Realistic Conditions. Environ. Res. 2025, 273, 121211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosrowshahi, M.S.; Mashhadimoslem, H.; Shayesteh, H.; Singh, G.; Khakpour, E.; Guan, X.; Rahimi, M.; Maleki, F.; Kumar, P.; Vinu, A. Natural Products Derived Porous Carbons for CO2 Capture. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2304289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.W.J.; Chen, C.; Buffet, J.-C.; O’Hare, D. Correlations of Acidity-Basicity of Solvent Treated Layered Double Hydroxides/Oxides and Their CO2 Capture Performance. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 9306–9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, Á.; Suárez-García, F.; Martínez-Alonso, A.; Tascón, J.M.D. Influence of Porous Texture and Surface Chemistry on the CO2 Adsorption Capacity of Porous Carbons: Acidic and Basic Site Interactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 21237–21247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Cai, P.; Wang, Z.; Lv, X.; Kawi, S. Surface Acidity/Basicity and Oxygen Defects of Metal Oxide: Impacts on Catalytic Performances of CO2 Reforming and Hydrogenation Reactions. Top. Catal. 2023, 66, 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, L.G.T.; Agustini, C.B.; Perez-Lopez, O.W.; Gutterres, M. CO2 Adsorption Using Solids with Different Surface and Acid-Base Properties. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lukose, B.; Ensing, B. A Free Energy Landscape of CO2 Capture by Frustrated Lewis Pairs. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 3376–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrowshahi, M.S.; Abdol, M.A.; Mashhadimoslem, H.; Khakpour, E.; Emrooz, H.B.M.; Sadeghzadeh, S.; Ghaemi, A. The Role of Surface Chemistry on CO2 Adsorption in Biomass-Derived Porous Carbons by Experimental Results and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.P.; Wu, S. Acid/Base-Treated Activated Carbons: Characterization of Functional Groups and Metal Adsorptive Properties. Langmuir 2004, 20, 2233–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xia, S.; Ren, X.; Dong, Y. Phosphoric Acid Addition: Insight into the Mechanism Governing Biochar Structural Evolution. Energies 2025, 18, 6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oginni, O.; Singh, K.; Oporto, G.; Dawson-Andoh, B.; McDonald, L.; Sabolsky, E. Effect of One-Step and Two-Step H3PO4 Activation on Activated Carbon Characteristics. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 8, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Yin, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, X. Synergistic Effect of Porous Structure and Heteroatoms in Carbon Materials to Boost High-performance Supercapacitor. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 10963–10973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Xuan, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J.; Dong, X.; Xi, F. N-Doped Mesoporous Carbon by a Hard-Template Strategy Associated with Chemical Activation and Its Enhanced Supercapacitance Performance. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 238, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malini, K.; Selvakumar, D.; Kumar, N.S. Activated Carbon from Biomass: Preparation, Factors Improving Basicity and Surface Properties for Enhanced CO2 Capture Capacity—A Review. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 67, 102318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Dziejarski, B. Activated Carbons—Preparation, Characterization and Their Application in CO2 Capture: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 40008–40062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, C.Y.; Laziz, A.M. Recent Progress in Synthesis and Application of Activated Carbon for CO2 Capture. C 2022, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neme, I.; Gonfa, G.; Masi, C. Activated Carbon from Biomass Precursors Using Phosphoric Acid: A Review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yue, L.; Hu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, Y.; Sun, Y.; DaCosta, H.; Guo, L. Efficient CO2 Capture by Porous Carbons Derived from Coconut Shell. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 4287–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayu, A.R.; Muda, N. Preparation and Characterization of Impregnated Activated Carbon from Palm Kernel Shell and Coconut Shell for CO2 Capture. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Shirzad, M.; Silva, J.A.C.; Rodrigues, A.E. Biomass/Biochar Carbon Materials for CO2 Capture and Sequestration by Cyclic Adsorption Processes: A Review and Prospects for Future Directions. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 57, 101890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Ouzzine, M.; Cruz, O.F.; Sreńscek-Nazzal, J.; Campello Gómez, I.; Azar, F.-Z.; Rey Mafull, C.A.; Hotza, D.; Rambo, C.R. Conversion of Fruit Waste-Derived Biomass to Highly Microporous Activated Carbon for Enhanced CO2 Capture. Waste Manag. 2021, 136, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, H.; Farhan, M.; Amjad, M.; Riaz, F.; Kazim, A.H.; Sultan, M.; Farooq, M.; Mujtaba, M.A.; Hussain, I.; Imran, M.; et al. Biomass Waste Utilization for Adsorbent Preparation in CO2 Capture and Sustainable Environment Applications. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 46, 101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin, J.; Kishibayev, K.; Tokpayev, R.; Khavaza, T.; Atchabarova, A.; Ibraimov, Z.; Nauryzbayev, M.; Nazzal, J.S.; Giraldo, L.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C. Functional Activated Biocarbons Based on Biomass Waste for CO2 Capture and Heavy Metal Sorption. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 48191–48210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, D.; Back, J.O.; Gurtner, D.; Giberti, S.; Hofmann, A.; Bockreis, A. Alternative Feedstock for the Production of Activated Carbon with ZnCl2: Forestry Residue Biomass and Waste Wood. Carbon. Resour. Convers. 2022, 5, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botomé, M.L.; Poletto, P.; Junges, J.; Perondi, D.; Dettmer, A.; Godinho, M. Preparation and Characterization of a Metal-Rich Activated Carbon from CCA-Treated Wood for CO2 Capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 321, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, F.; Aroua, M.K.; Kassim, M.A.; Ali, U.F.M. Transforming Plastic Waste into Porous Carbon for Capturing Carbon Dioxide: A Review. Energies 2021, 14, 8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Z.; Deng, S.; Zhao, R. Numerical Simulation and Performance Analysis of Temperature Swing Adsorption Process for CO2 Capture Based on Waste Plastic-Based Activated Carbon. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 17822–17833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Zafanelli, L.F.A.S.; Almeida, J.P.P.; Ströher, G.R.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Silva, J.A.C. Novel Insights into Activated Carbon Derived from Municipal Solid Waste for CO2 Uptake: Synthesis, Adsorption Isotherms and Scale-Up. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhu, C.C.; Tan, Z.C.; Bao, L.W.; Wang, J.J.; Miao, G.; Kong, L.Z.; Sun, Y.H. Preparation of N-Doped Activated Carbons with High CO2 Capture Performance from Microalgae (Chlorococcum sp.). RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 38724–38730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Ochedi, F.O.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y. Porous Biochars Derived from Microalgae Pyrolysis for CO2 Adsorption. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 7646–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos, J.; Beckner, M.; Rash, T.; Firlej, L.; Kuchta, B.; Yu, P.; Suppes, G.; Wexler, C.; Pfeifer, P. Nanospace Engineering of KOH Activated Carbon. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 015401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Alcañiz-Monge, J.; de la Casa-Lillo, M.A.; Linares-Solano, A. CO2 As an Adsorptive To Characterize Carbon Molecular Sieves and Activated Carbons. Langmuir 1998, 14, 4589–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghurabi, E.H.; Boumaza, M.M.; Al-Masry, W.; Asif, M. Optimizing the Synthesis of Nanoporous Activated Carbon from Date-Palm Waste for Enhanced CO2 Capture. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Bahadur, R.; Mee Lee, J.; Young Kim, I.; Ruban, A.M.; Davidraj, J.M.; Semit, D.; Karakoti, A.; Al Muhtaseb, A.H.; Vinu, A. Nanoporous Activated Biocarbons with High Surface Areas from Alligator Weed and Their Excellent Performance for CO2 Capture at Both Low and High Pressures. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, L.K.C.; Gonçalves, A.A.S.; Queiroz, L.S.; Chaar, J.S.; da Rocha Filho, G.N.; da Costa, C.E.F. Utilization of Acai Stone Biomass for the Sustainable Production of Nanoporous Carbon for CO2 Capture. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2020, 25, e00168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, S.S.; Elumalali, S.K.; Kumaresan, T.K.; Meganathan, R.; Ashok, A.; Pawar, V.; Vediappan, K.; Ramasamy, G.; Karazhanov, S.Z.; Raman, K.; et al. Partially Graphitic Nanoporous Activated Carbon Prepared from Biomass for Supercapacitor Application. Mater. Lett. 2018, 218, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Lakhi, K.S.; Ramadass, K.; Kim, S.; Stockdale, D.; Vinu, A. A Combined Strategy of Acid-Assisted Polymerization and Solid State Activation to Synthesize Functionalized Nanoporous Activated Biocarbons from Biomass for CO2 Capture. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 271, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Chu, X.; Ren, F.; Zheng, S.; Shao, Z. Study on CO2 Adsorption Performance of Biocarbon Synthesized in Situ from Nitrogen-Rich Biomass Pomelo Peel. Fuel 2023, 352, 129163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, X.; Ji, B.; Xu, Z.; Bao, S.; Yang, Z.; Mei, J.; Rong, J.; Li, Z. Nitrogen Self-Doping Hierarchical Pore Biochar for Enhanced CO2 Capture: Modulation of Pore Structure and Surface Properties. Langmuir 2025, 41, 8876–8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Sun, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, B.; Tong, X.; Wang, X.; Niu, Y.; Wu, J. Biomass Based N/O Codoped Porous Carbons with Abundant Ultramicropores for Highly Selective CO2 Adsorption. Energies 2023, 16, 5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Shi, W.; Yin, H.; Zhang, S.; Yang, B. Poplar Catkin-Derived Self-Templated Synthesis of N-Doped Hierarchical Porous Carbon Microtubes for Effective CO2 Capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, E.; Cheng, S.; Tu, R.; He, Z.; Jia, Z.; Long, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, X. High Yield Self-Nitrogen-Oxygen Doped Hydrochar Derived from Microalgae Carbonization in Bio-Oil: Properties and Potential Applications. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 314, 123735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Ma, X. Preparation of Multi-Heteroatom Self-Doped Carbon Materials Using Industrial Waste Template Agent Combined with One-Step Carbonization: Multiple Applications in Supercapacitors and CO2 Adsorption. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 373, 133609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M.; Ferrero, G.A.; Fuertes, A.B. One-Pot Synthesis of Biomass-Based Hierarchical Porous Carbons with a Large Porosity Development. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 6900–6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajula, F.; Galarneau, A.; Renzo, F. Di Advanced Porous Materials: New Developments and Emerging Trends. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 82, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, F.; Ergang, N.S.; Stein, A. Effects of Hierarchical Architecture on Electronic and Mechanical Properties of Nanocast Monolithic Porous Carbons and Carbon−Carbon Nanocomposites. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 5543–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lam, C.W.K.; Wu, N.; Pang, S.-S.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ju, Z. Multiple Templates Fabrication of Hierarchical Porous Carbon for Enhanced Rate Capability in Potassium-Ion Batteries. Mater. Today Energy 2019, 11, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovich, N.D.; Stein, A. Controlling Macro- and Mesostructures with Hierarchical Porosity Through Combined Hard and Soft Templating. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 3721–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; He, Y.; Yin, S.; Chang, X.; Zhang, J.; Peng, L.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Wei, Q.; Lan, K.; et al. Bimodal Ordered Porous Hierarchies from Cooperative Soft-Hard Template Pairs. Matter 2023, 6, 3099–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, H.; Yang, P.; Xiao, L.; Du, L.; Lu, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, J.; An, M. A Dual-Template Strategy to Engineer Hierarchically Porous Fe–N–C Electrocatalysts for the High-Performance Cathodes of Zn–Air Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 9761–9770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, L.; Dua, R.; Bhandari, N.; Ramanujapuram, A.; Wang, P.; Giannelis, E.P. A Facile Approach for the Synthesis of Monolithic Hierarchical Porous Carbons—High Performance Materials for Amine Based CO2 Capture and Supercapacitor Electrode. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wu, D.; Fu, R. Carbon Microfibers with Hierarchical Porous Structure from Electrospun Fiber-Like Natural Biopolymer. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi, M.; Younesi, H.; Bahramifar, N. Superior CO2 Capture Performance on Biomass-Derived Carbon/Metal Oxides Nanocomposites from Persian Ironwood by H3PO4 Activation. Fuel 2018, 223, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, C.; Hatton, T.A. The Potential of Molten Metal Oxide Sorbents for Carbon Capture at High Temperature: Conceptual Design. Appl. Energy 2020, 280, 116016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, L.K.G.; Bhatta, U.M.; Venkatesh, K. Metal Oxides for Carbon Dioxide Capture. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Inamuddin, A.A., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 38, pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, A.E.; Gao, B.; Zimmerman, A.; Harris, W. Biomass-Facilitated Production of Activated Magnesium Oxide Nanoparticles with Extraordinary CO2 Capture Capacity. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Shao, Z.; Wen, S.; Wang, J.; Ning, P.; Lu, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q. Biomass-Derived Carbon/MgO-Al2O3 Composite with Superior Dynamic CO2 Uptake for Post Combustion Capture Application. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 54, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, Y.; Fang, M.; Liu, B.; Chen, R.; Shi, R.; Wu, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Li, L. In-Situ Activated Ultramicroporous Carbon Materials Derived from Waste Biomass for CO2 Capture and Benzene Adsorption. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 158, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, A.E.; Gao, B.; Wang, S. Carbon Dioxide Capture Using Various Metal Oxyhydroxide–Biochar Composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, S.; Akhtar, M.; Arshad, M.; Ijaz, M.H.; Janjua, M.R.S.A. A Review on Synthesis of MOF-Derived Carbon Composites: Innovations in Electrochemical, Environmental and Electrocatalytic Technologies. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 27575–27607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, M.; De, A.; Mishra, S. Cellulose and Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Synergistic Strategies for Developing High-Performance Cellulose/MOFs Composites. Cellulose 2025, 32, 6891–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, M.; Lu, H.; Liu, H. Study on the Preparation of Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon and Enhanced Carbon Capture Performance via MOF-Assisted Granulation. Langmuir 2025, 41, 12078–12088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, H.; Hu, Y.; Tong, X.; Zhong, L.; Peng, X.; Sun, R. Sustainable Hierarchical Porous Carbon Aerogel from Cellulose for High-Performance Supercapacitor and CO2 Capture. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 87, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Kimura, S.; Wada, M.; Kuga, S.; Zhang, L. Cellulose Aerogels from Aqueous Alkali Hydroxide–Urea Solution. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Yuan, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, T.C.; He, G.; Yuan, S. Cellulose-Based Aerogel Derived N, B-Co-Doped Porous Biochar for High-Performance CO2 Capture and Supercapacitor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 269, 132078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y. Layered 2D Materials in Batteries. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 27907–27939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Chu, K.; Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wei, L.; Xu, Y.; Yao, G.; Chen, Q. Optimizing the Interlayer Spacing of Heteroatom-Doped Carbon Nanofibers Toward Ultrahigh Potassium-Storage Performances. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 9212–9221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Ma, Y.; Qu, W.; Qian, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, A.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Hu, Z.; et al. Large Interlayer Distance and Heteroatom-Doping of Graphite Provide New Insights into the Dual-Ion Storage Mechanism in Dual-Carbon Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202307083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Lin, S.; Yu, D.; Wang, Z.; Deng, F.; Zhou, X.; Ma, G.; Lei, Z. Interlayer and Doping Engineering in Partially Graphitic Hollow Carbon Nanospheres for Fast Sodium and Potassium Storage. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 107339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinckmann, S.A.; Patra, N.; Yao, J.; Ware, T.H.; Frick, C.P.; Fertig, R.S. Stereolithography of SiOC Polymer-Derived Ceramics Filled with SiC Micronwhiskers. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1800593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinckmann, S.A.; Yao, J.; Young, J.C.; Jones, M.H.; Fertig, R.S., III; Frick, C.P. Additive Manufacturing of SiCNO Polymer-Derived Ceramics via Step-Growth Polymerization. Open Ceram. 2023, 15, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Zeng, Q.; Li, F.; Shi, L.; Wu, W.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, H. Effect of Boron Doping on the Interlayer Spacing of Graphite. Materials 2022, 15, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.; Lee, J.; Bahadur, R.; Karakoti, A.; Yi, J.; Vinu, A. Highly Graphitized Porous Biocarbon Nanosheets with Tunable Micro-Meso Interfaces and Enhanced Layer Spacing for CO2 Capture and LIBs. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 134464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunpandian, R.; Kumar, M.; Lasalle, B.S.I.; Vijayakumar, P.; Chang, J.-H. Hierarchical Synthesis of Multi-Layer Graphene-like and Nitrogen-Doped Graphitized Carbon from Dead Leaf Biomass for High-Performance Energy Storage and CO2 Capture. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, 172, 106100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Yang, Y.; Kang, F. Carbon Nanofibers Prepared via Electrospinning. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2547–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Lee, J.S. Electrospinning-Based Carbon Nanofibers for Energy and Sensor Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Duan, G.; Jiang, S. Electrospun Carbon Nanofibers and Their Reinforced Composites: Preparation, Modification, Applications, and Perspectives. Compos. B Eng. 2023, 249, 110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, Z.; Gong, W.; Xu, F.; Song, X.; He, X.; Fan, M. Electrospun Carbon Nanofibers and Their Applications in Several Areas. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 22316–22330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, C.; Li, M.; Truong, P.; Li, J.; Lin, H.-S.; Naik, M.T.; Xiang, S.; Jackson, B.E.; Kuo, W.; et al. Enhancing the Multi-Functional Properties of Renewable Lignin Carbon Fibers via Defining the Structure–Property Relationship Using Different Biomass Feedstocks. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 3725–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, A.; Pulikkalparambil, H.; Jagadeesh, P.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Recent Advancements in Lignocellulose Biomass-Based Carbon Fiber: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfond, J.; Meng, T.; Li, S.; Li, T.; Hu, L. Highly Electrically Conductive Biomass-Derived Carbon Fibers for Permanent Carbon Sequestration. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 35, e00573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, R.; Nah, Y.-C.; Oh, H. Spider Silk-Derived Nanoporous Activated Carbon Fiber for CO2 Capture and CH4 and H2 Storage. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 69, 102401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Dai, L.; Si, C. Lignin-derived Carbon Fibers: A Green Path from Biomass to Advanced Materials. Carbon Energy 2025, 7, e662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Q. Fabrication of Vertical Structure Type Bimetallic MOF@ Biomass Aerogels for Efficient CO2 Capture and Separation. Carbon. Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.H.; Kim, M.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, M.; Park, Y.D. Metal–Organic-Framework-Decorated Carbon Nanofibers with Enhanced Gas Sensitivity When Incorporated into an Organic Semiconductor-Based Gas Sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 10637–10647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shezad, N.; Kumar, P.; Patel, A.; Matsakas, L.; Akhtar, F. Metal-Organic Frameworks Coated Cellulose Nanofibers for Localized Carbon Dioxide Capture. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 2025, 9924588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Feng, S.; Yang, X.; Lyu, H.; Wei, S.; Shen, B. A Review of Biomass Porous Carbon for Carbon Dioxide Adsorption from Flue Gas: Physicochemical Properties and Performance. Fuel 2025, 387, 134318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, M.; Lapa, N.; Fonseca, I.; Esteves, I.A.A.C. Biomass Valorization to Produce Porous Carbons: Applications in CO2 Capture and Biogas Upgrading to Biomethane—A Mini-Review. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 625188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodah, A.E.M.; Ghosal, M.K.; Behera, D. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Agricultural Residues: Current Scenario, Challenges, and Future Direction. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 2195–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I.; Pérez, S.F.; Fernández-Ferreras, J.; Llano, T. Microwave-Assisted Pyrolysis of Forest Biomass. Energies 2024, 17, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriapparao, D.V.; Vinu, R. Biomass Waste Conversion into Value-Added Products via Microwave-Assisted Co-Pyrolysis Platform. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Bhaumik, A.; Wu, K.C.-W. Hierarchically Porous Carbon Derived from Polymers and Biomass: Effect of Interconnected Pores on Energy Applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3574–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Vilya, K.; Pradhan, M.; Nayak, A.K. Recent Advancement of Biomass-Derived Porous Carbon Based Materials for Energy and Environmental Remediation Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 6965–7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yu, Y.; Chang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Kaplan, D.L. Enhanced CO2 Capture and Utilization through Chemically and Physically Dual-Modified Amino Cellulose Aerogels Integrated with Microalgae-Immobilized Hydrogels. ACS EST Eng. 2025, 5, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, D.; Mac Dowell, N.; Shah, N.; Petit, C.; Fennell, P.S. A Techno-Economic Analysis and Systematic Review of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) Applied to the Iron and Steel, Cement, Oil Refining and Pulp and Paper Industries, as Well as Other High Purity Sources. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 61, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, K.; Upadhyay, A.; Runge, T.; Bergman, R.; Puettmann, M.; Bilek, E. Life-Cycle Assessment and Techno-Economic Analysis of Biochar Produced from Forest Residues Using Portable Systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 189–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstone, M.; Kopits, E.; Wolverton, A. Developing a Social Cost of Carbon for US Regulatory Analysis: A Methodology and Interpretation. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2013, 7, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhaus, W.D. Revisiting the Social Cost of Carbon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1518–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Pathways to a Low-Carbon Economy: Version 2 of the Global Greenhouse Gas Abatement Cost Curve. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/pathways-to-a-low-carbon-economy (accessed on 1 September 2013).

- Zimmermann, A.W.; Wunderlich, J.; Müller, L.; Buchner, G.A.; Marxen, A.; Michailos, S.; Armstrong, K.; Naims, H.; McCord, S.; Styring, P.; et al. Techno-Economic Assessment Guidelines for CO2 Utilization. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Drese, J.H.; Jones, C.W. Adsorbent Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Large Anthropogenic Point Sources. ChemSusChem 2009, 2, 796–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochelle, G.T. Amine Scrubbing for CO2 Capture. Science 2009, 325, 1652–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Muûls, M.; Wagner, U.J. The Impact of the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme on Regulated Firms: What Is the Evidence After Ten Years? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2016, 10, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Capture Mechanism | Interaction | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physisorption | van der Waals forces, dipole interactions | Reversible and good regenerability; Low energy consumption; Mature, low-cost synthesis | Low selectivity; Limited capacity by pore structure; Less stable at high temperature or humidity | [77,81,82] |

| Chemisorption | Chemical bonds (covalent or ionic) | High selectivity; Stable at elevated temperature/pressure; Tunable surface sites enhance CO2 affinity | May be irreversible or energy-intensive to regenerate; Lower cyclic stability; Complex, costly functionalization | [83,84,85,87,88] |

| Physisorption–Chemisorption Synergy | van der Waals forces, dipole interactions, and chemical bonds | High capacity; Strong selectivity; Good cyclic stability; Effective across wide temperature/pressure ranges | Complex design balancing pores and functionality; Performance depends on structure-component synergy; Higher production cost | [89,90] |

| Feedstock Type | Resource Ability | Key Features | Advantages for Carbon Materials | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural residues | Seasonal availability; Abundant and widely accessible | Rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin; High carbon content; Low ash and sulfur | Easily pyrolyzed; Tunable pore structure; High carbon yield | [91,92,93,94] |

| Forestry residues | Large quantities; Widely distributed; Stable supply | High lignin content; High carbon content; Low ash, sulfur, and heavy metal contents; Uniform structure | Suitable for high surface area activated carbon; Low impurity levels; Stable pore structure; Excellent adsorption performance | [95,96,97,98] |

| Municipal solid wastes | Massive quantity; Diverse sources; High recycling potential | Complex composition; Pretreatment required; High proportion of organic components | Promotes waste valorization; Strong environmental co-benefits | [99,100,101] |

| Algae | Short growth cycle; High light-use efficiency; Obtainable via enriched water bodies or cultivation | High carbon, low lignin; Nitrogen-rich; Easily doped/modified | Biomass can capture CO2; Nitrogen-rich carbon favors chemisorption sites and enhances performance | [102,103,104] |

| Animal-derived biomass | High-value utilization potential | Rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur; Easily self-doped | Naturally multi-heteroatom-doped; High surface activity; Favorable for CO2 chemisorption and catalytic reactions | [105,106] |

| Biomass Components | Pyrolysis Temperature (°C) | Thermal Stability | Product Characteristics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemicellulose | 200–350 | Low | Low char yield; Produces abundant volatile small molecules; Unstable char structure | [126,133] |

| Cellulose | 300–400 | Moderate | Moderate char yield; Forms lamellar structures with well-developed porosity | [126,134] |

| Lignin | >400 | High | High char yield; Stable carbon framework; Rich in aromatic structures | [126,135] |

| Pyrolysis Process | Heating Rate | Residence Time | Feedstock Characteristics | Main Products | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slow pyrolysis | 0.1–1 °C/s | Several minutes to hours | Dense, low-moisture, lignocellulosic-rich biomass | Mainly biochar | [126,137] |

| Fast pyrolysis | 10–200 °C/s | 0.5–10 s | Light, low- to moderate-moisture, high-volatile-matter biomass | Mainly bio-oil | [126,136] |

| Flash pyrolysis | >1000 °C/s | <1 s | Fine, low-moisture, high-volatile-matter biomass | Bio-oil and gases | [126,136] |