Abstract

In this work, a novel polyvinyl alcohol/starch (PVA/St)-based composite film was fabricated by integrating citric acid (CA) and silver-loaded biochar (C-Ag) nanofillers to enhance antibacterial functionality. Sorghum straw-derived biochar was loaded with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) through a green synthesis route using Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn extract. The successful crosslinking by CA and the uniform incorporation of AgNPs were confirmed by FTIR, XRD, and SEM. Notably, the optimized composite film containing 1.5 g/L C-Ag exhibited strong broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, with inhibition zones of 28 mm against E. coli, 29 mm against S. aureus, and 26 mm against P. aeruginosa, respectively. The high efficacy is attributed to the synergistic effect between the sustained release of Ag+ and the CA-induced acidic microenvironment. This work provides a green and high-performance antibacterial material to address the potential microbe contamination.

1. Introduction

The governance of water environmental pollution has become one of the core challenges facing global sustainable development. Organic pollutants and pathogenic bacteria remaining in industrial and domestic wastewater continuously threaten aquatic ecosystem security and public health [1,2]. In response to this challenge, research efforts have focused on developing effectual and low-consumption materials and technologies for wastewater treatment. Among them, bio-based materials (such as cellulose-based gels and polylactic acid microspheres) demonstrate promising application prospects due to their biodegradability, tunable structures, and environmental compatibility [3,4,5]. To further enhance material performance, researchers have developed composite materials such as nanofiber-reinforced gels and multilayer structured adsorbents, which significantly improve mechanical stability while effectively increasing pollutant removal efficiency [6,7]. Meanwhile, for targeted suppression of pathogenic microorganisms, natural antibacterial components and inorganic antibacterial materials have been successfully incorporated into gel systems, creating dual-functional materials capable of simultaneously degrading pollutants and inactivating pathogenic bacteria [8,9,10,11,12]. This integration provides a novel technological pathway for highly efficient water treatment.

Among various bio-based materials, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and starch (St) have attracted extensive attention due to their outstanding biocompatibility, biodegradability, and film-forming characteristics. The PVA molecular chain, abundant in hydroxyl groups, demonstrates excellent hydrophilicity and processability [13]. St, as a natural polysaccharide, is inexpensive and extensively available [14]. The PVA and St blending can achieve complementary advantages, forming basic packaging film materials [15,16,17]. While PVA/St films have advantages, they also exhibit relatively weak mechanical strength and poor water vapor barrier properties [18]. Most importantly, the lack of intrinsic antibacterial functionality makes them susceptible to microbial contamination [19].

To augment the performance of PVA/St membranes, the physical modification and chemical crosslinking strategies can be adopted to enhance mechanical strength and water vapor barrier properties [20,21,22,23]. Citric acid (CA) crosslinking manifests unique merits due to its green and eco-friendly characteristics [22]. The -COOH groups in CA molecule can generate ester bonds with -OH groups of PVA/St, fabricating a three-dimensional network structure and considerably improving water resistance and mechanical properties [22,23,24]. The antimicrobial function of food packaging materials is essential for food preservation. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), as one kind of effectual antimicrobial material, have showcased broad application in textiles, food packaging, medical care, and environmental protection because of their special chemical and physical properties and multiple antimicrobial mechanisms. However, free AgNPs are prone to agglomeration and inactivation and have a risk of migration [25,26,27,28,29]. To address these limitations while adhering to sustainable principles, green synthesis of AgNPs using plant extracts has gained considerable interest [30]. In particular, the use of plant extracts as reducing and stabilizing agents has gained prominence due to their abundance, low cost, and rich content of bioactive compounds such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and terpenoids. These phytochemicals can effectively reduce metal ions to nanoparticles while capping them, preventing aggregation and enhancing stability [31,32,33]. Biochar, as a bio-based functional material, features a highly developed pore structure and abundant surface functional groups (such as carboxyl groups, phenolic hydroxyl groups, etc.), enabling it not only to serve as a nano-filler to enhance the mechanical properties of the matrix but also to acquire functional modification through the loading of active components onto the pores [34,35,36,37]. Meanwhile, nanomaterials such as silver-loaded biochar (C-Ag) possess the broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties of silver ions and the porous adsorption characteristics of biochar, simultaneously enhancing the mechanical strength, antimicrobial activity and environmental stability of films [38]. Accordingly, adding C-Ag into antimicrobial materials offers a breakthrough solution for degradable packaging materials by combining the unique properties of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) with biochar.

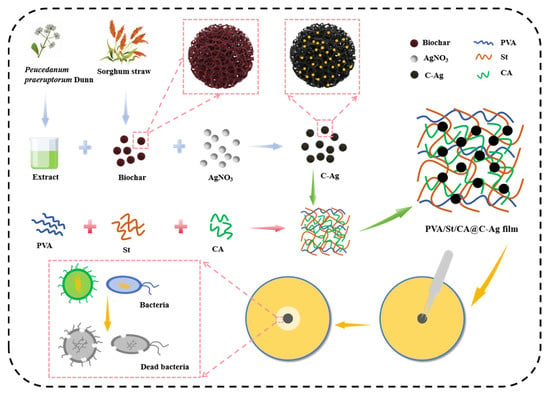

In this context, Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn, a traditional medicinal herb widely documented for its diverse coumarin and flavonoid constituents, was specifically selected. These characteristic secondary metabolites, particularly praeruptorins and flavonoids, are known to possess strong reducing capacities and can effectively stabilize nascent nanoparticles. Its local availability further underscores our commitment to resource sustainability, making it an ideal green reductant that aligns with the principles of green chemistry and circular economy. This study developed a novel antibacterial composite film via a threefold innovative strategy: (i) green synthesis of AgNPs using Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn extract, (ii) their immobilization on biochar, and (iii) crosslinking of the PVA/St matrix with citric acid. Specifically, Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn extract was employed as a green reducing agent to synthesize C-Ag from sorghum straw. Through this integrated approach, a hierarchically structured PVA/St-based composite film was successfully fabricated (Figure 1). Multi-scale characterization techniques including Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were systematically adopted to estimate the comprehensive impacts of crosslinked networks and nanofillers on the composite film’s antimicrobial performance. This work provided a green and effective antibacterial composite film, which has potential application.

Figure 1.

Synthesis and antibacterial application of PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite films.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

Polyvinyl alcohol, soluble starch, citric acid, glycerol, and silver nitrate were purchased from Run You Reagent Co. (Changzhou, China). DPPH was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). E. coli ATCC 25922, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and S. aureus ATCC 6538 were provided by the Typical Cultures Depository Center (Manassas, VA, USA). Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn and sorghum straw were obtained locally from Changzhou, China.

2.2. Pre-Processing of Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn

Firstly, the collected Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn was rinsed several times with triple-distilled water to eliminate dust and impurities. Furthermore, it was oven-dried (40 °C) to remove moisture. Eventually, the dried material was milled into powder using a grinder and passed through a 60-mesh sieve. A total of 5.0 g of Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn powders were scattered in distilled water (100 mL) and subjected to ultrasonic extraction (8 h). The mixture was then filtered to obtain the extract, which was stored at 4 °C for further use.

2.3. Preparation of Sorghum Straw Biochar Loaded with Nanosilver

Initially, sorghum straw underwent pretreatment involving washing, drying, grinding, and sieving. Subsequently, the resulting powder was placed in a muffle furnace and calcined (300 °C, 120 min). Upon completion of calcination, the biochar was withdrawn and allowed to cool naturally, followed by a secondary grinding step. Afterwards, 5.0 g of biochar was soaked in silver nitrate solution (4.0 g/L, 100 mL) and continuously stirred (120 min) to ensure thorough impregnation. Following this mixing process, 20 mL of Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn extract was adopted for reducing the silver ions under continuous stirring at ambient temperature. The reduction reaction was monitored visually by observing the color change in the suspension [39]. The completion of the reaction was confirmed when the color stabilized to a deep brown, indicating the formation of AgNPs, and no further color change was observed for an extended period [40]. Once the reduction reaction was over, the resulting suspension was filtered and dried. Eventually, the silver-impregnated biochar (C-Ag) was subjected to the calcination (400 °C, 2 h) for stabilizing and firmly loading AgNPs within the biochar matrix.

2.4. Preparation of PVA/St-Based Nanocomposite Films

The preparation process of PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite film was conducted. Firstly, 5.0 g of PVA was dispersed in 100 mL of deionized water, dissolved (90 °C, 60 min) and further cooled down at room temperature. Subsequently, 5 g of St was mixed with 100 mL of water and further gelatinized at 85 °C until the solution was clear. Afterwards, citric acid (CA), glycerol, PVA, St and C-Ag were blended (90 °C, 60 min), and the prepared solution was poured into a mold and dried at 50 °C. Eventually, the formed PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite film was removed from the mold. The samples were named P/St, P/St/CA, P/St@C-Ag and P/St/CA@C-Ag.

2.5. Bacteriostatic Properties

Bacterial suspensions (including E. coli ATCC 25922, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and S. aureus ATCC 6538) at an initial concentration of 108 CFU/mL were taken and uniformly spread on the surface of the solid medium. Afterwards, a hole punch was used to make a 9 mm cavity in the LB agar plate, and 0.1 g of composite film was added to each hole. Subsequently, the medium was incubated in an incubator at 37 °C. After 24 h, the size of the inhibition zone was recorded and measured in order to find out the calcination temperature and the concentration of silver nitrate with the best inhibition effect.

2.6. Structure of C-Ag and Composite Films

The functional groups of C-Ag and composite films were analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (Nicolet IS50 FTIR, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The surface morphology and silver distribution were characterized by Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, SU8010, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The crystal structure was determined by X-ray Diffraction (XRD, Bruker D2 Phaser, Karlsruhe, Germany). The thickness of composite film was measured with a precision digital thickness gauge (accuracy 0.01 mm) by taking the average of multiple point measurements.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as the mean, with variability expressed as the standard deviation (SD), based on three independent replicates (n = 3). All analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25.0). The significance of the difference is as follows: * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, *** indicates p < 0.001, and ns indicates p > 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. FT-IR

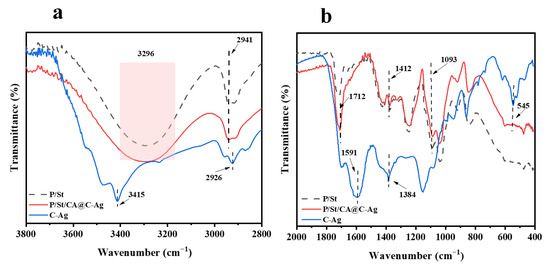

The FTIR spectra of the C-Ag, PVA/St, and PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite films are depicted in Figure 2. Characteristic peaks of the prepared materials are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of PVA/St, PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite films, and C-Ag at wavenumber 3800 to 2800 cm−1 (a); FTIR spectra of PVA/St, PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite films, and C-Ag at wavenumber 2000 to 400 cm−1 (b).

Table 1.

Results of FTIR spectroscopic analysis of PVA/St, PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite films, and C-Ag.

The C-Ag exhibits a strong peak near 3415 cm−1, manifesting that the material is rich in hydroxyl groups (-OH), and the peaks around 2926 cm−1 and 1591 cm−1 confirm that it has aliphatic and aromatic carbon skeleton structures [41]. The most critical characteristic peak about 545 cm−1 directly verifies the formation of the Ag-O bond, revealing that silver is stably loaded on the biochar surface through chemical bonding rather than physical adsorption. The typical peaks of the PVA/St film (hydroxyl vibration near 3296 cm−1, C-H stretching vibration around 2941 cm−1, and C-O vibration about 1093 cm−1) can be retained in all composite systems, revealing that the polymer skeleton structure remained stable [42]. Notably, the characteristic O-H peak of C-Ag at 3415 cm−1 is not distinctly visible in the P/St/CA@C-Ag spectrum, as it is likely masked by the strong and broad hydroxyl absorption of the PVA/St matrix (3296 cm−1) and may have merged due to interfacial interactions. By supplementing CA, the enhancement of the peaks near 1712 cm−1 (C=O) and 1412 cm−1 (COO−) proves the esterification crosslinking reaction of CA with PVA/St, supporting the generation of the crosslinked structure [43]. Carboxylate characteristic peaks can be observed in the PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite film around 1412 cm−1 and 1384 cm−1, and the C-O peak shifts near 1093 cm−1, proving that CA may coordinate with Ag+ in C-Ag via COO− [44]. This could improve the dispersibility of biochar and augment the interfacial interaction of the composite materials. CA not only serves as a crosslinking agent to enhance the polymer network but may also optimize the diffusion performance of C-Ag through metal coordination.

3.2. SEM

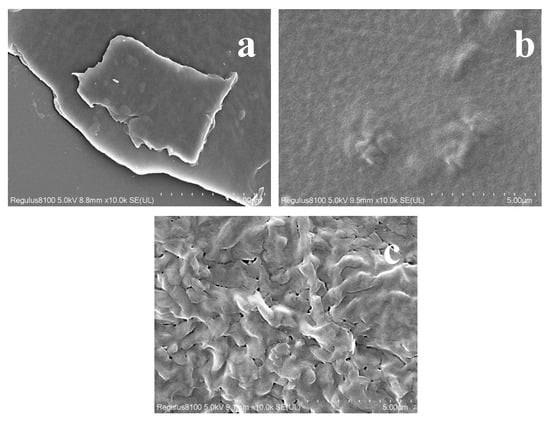

The SEM analysis shows that the C-Ag exhibits a distinctly rough and modified surface topography, with a uniform distribution of particulate entities on its surface (Figure 3). This morphological change is characteristic of successful surface functionalization and nanoparticle deposition, as documented for similar metal-loaded composite systems [45]. The PVA/St film manifests a smooth surface, displaying good compatibility between these components [46]. Upon adding CA, the crosslinking effect might result in a denser and more homogeneous film structure [47]. The incorporation of C-Ag can augment the surface roughness of the composite film. With well-scattered biochar particles, no considerable agglomeration occurs and strong interfacial adhesion with the matrix can happen. Further modification with CA led to an even denser structure, effectively loading both the silver particles and biochar while enhancing interfacial bonding. Thus, while SEM provides crucial morphological evidence for filler incorporation and dispersion, the definitive chemical and structural identification of AgNPs is unambiguously confirmed by the complementary XRD and FTIR analyses [48,49].

Figure 3.

SEM image of C-Ag (a), PVA/St (b), and PVA/St/CA@C-Ag (c) composite films.

3.3. XRD

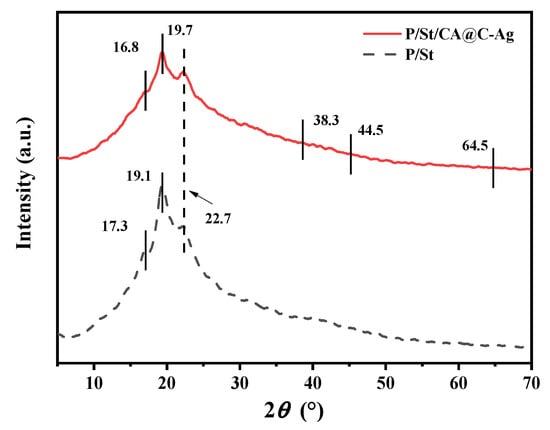

The crystallinity of C-Ag and different composite films is shown by measuring with XRD. The XRD pattern of C-Ag manifests a broad diffraction peak near 22.7° (Figure 4), corresponding to the amorphous structure of biochar, while the characteristic peaks at 38.3°, 44.5°, and 64.5° are indexed to the (111), (200), and (220) crystal planes of face-centered cubic (FCC) structured metallic silver (JCPDS No. 04-0783), providing definitive evidence for the successful formation of crystalline AgNPs [50]. Upon mixing PVA and St, the diffraction peak of the PVA (101) plane shifts from 19.7° to a lower angle of 19.1°, and the St peak at 17.3° is broadened, revealing an increase in PVA lattice spacing due to starch molecule intercalation. Upon crosslinking with CA, the PVA crystalline peak further shifts to a higher angle of 19.7° with increased full width at half maximum (FWHM), while the characteristic starch peak at 17.3° considerably weakens due to esterification, generating a new broad peak near 16.8° and confirming the formation of an amorphous crosslinked product [51]. In the composite films, the intensity of the amorphous carbon peak (22.7°) from biochar diminishes, whereas the sharp Ag (111) diffraction peak near 38.3° proves the stable presence of AgNPs [52,53]. These structural alterations indicate that CA can disrupt the crystalline regions of PVA/St through ester bond crosslinking while constructing a three-dimensional network. This crosslinked network, evidenced by the FTIR and XRD spectral shifts, forms the structural basis for the film’s enhanced mechanical stability and controlled degradation. Meanwhile, the interfacial interactions between silver-loaded biochar and the polymer matrix allow the material to maintain antimicrobial activity while acquiring tunable crystallinity. This tailored microstructure, comprising a CA-crosslinked network and well-dispersed C-Ag fillers, establishes the structural basis for the material’s final properties. Specifically, the crosslinked network and strong filler-matrix adhesion enhance mechanical strength by efficiently transferring stress. Concurrently, the hydrophilic nature of the components and the adjustable crystallinity collectively govern the degradation behavior by controlling water penetration and polymer chain scission rates.

Figure 4.

XRD of PVA/St and PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite films.

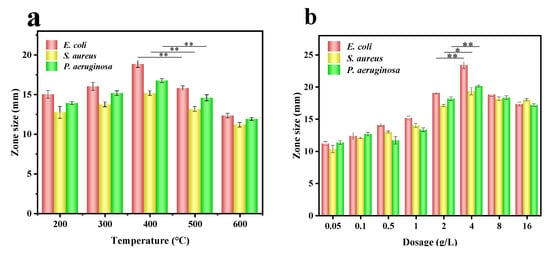

3.4. Effect of Calcination Temperature and Silver Ion Concentration of the Composite Material on the Antibacterial Ability

The antimicrobial properties of C-Ag against E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus were measured by the agar plate diffusion method, and the results are shown in Figure 5. The calcination temperature and silver ion concentration of the composite material influence the pore structure of biochar, the particle size and dispersion of AgNPs, and thus impact the antimicrobial performance of the composite material [53]. Upon elevating temperature, the antimicrobial effect of C-Ag on the three bacteria first enhanced and then declined (Figure 5a). Statistical analysis indicated that the samples prepared at 400 °C exhibited stronger antibacterial activity compared to other temperatures (p < 0.01). The inhibitory zones against E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa were 19 mm, 15 mm, and 16.5 mm, respectively. Under this calcination temperature, the pore size of biochar enlarged, and the specific surface area also increased [54], favoring that AgNPs are uniformly dispersed and exposed on the biochar surface. Below the calcination temperature, the structure of biochar is mainly microporous, with a low specific surface area. The particle size of AgNPs is small and is easily encapsulated in a dense structure, making it difficult to contact with bacteria and acquire poor antimicrobial efficacy. Excessively high calcination temperature may lead to excessive graphitization of biochar, an increase in micropores but melting of AgNPs, a decrease in the utilization rate of specific surface area, and impact the release of AgNPs, consequently resulting in poor antimicrobial efficacy.

Figure 5.

Diameter of the inhibition zone of C-Ag complex on E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa at different temperatures (AgNO3 fixed at 1.5 g/L) (a) and AgNO3 concentrations (temperature fixed at 400 °C) (b). Asterisks denote statistical significance (* indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01).

With increasing the concentration of silver nitrate, the antimicrobial effect of C-Ag on the three bacteria firstly improved and then weakened (Figure 5b). The formulation with 4 g/L AgNO3 showed enhanced antibacterial effects, with mean inhibition zones of 23 mm for E. coli, 19 mm for S. aureus, and 20 mm for P. aeruginosa; these values were statistically superior to those at adjacent concentrations (p < 0.05). In the low concentration range of AgNO3, due to the insufficient silver loading, AgNPs might be sparsely distributed on the surface of biochar, and the antimicrobial effect is weak [55]. In the high concentration range of AgNO3, excessive silver loading leads to agglomeration of AgNPs, a declined specific surface area, a reduction in the release rate of silver ions, and a decline in antimicrobial activity [56]. Accordingly, C-Ag with a calcination temperature of 400 °C and AgNO3 of 4 g/L were selected for a series of subsequent studies.

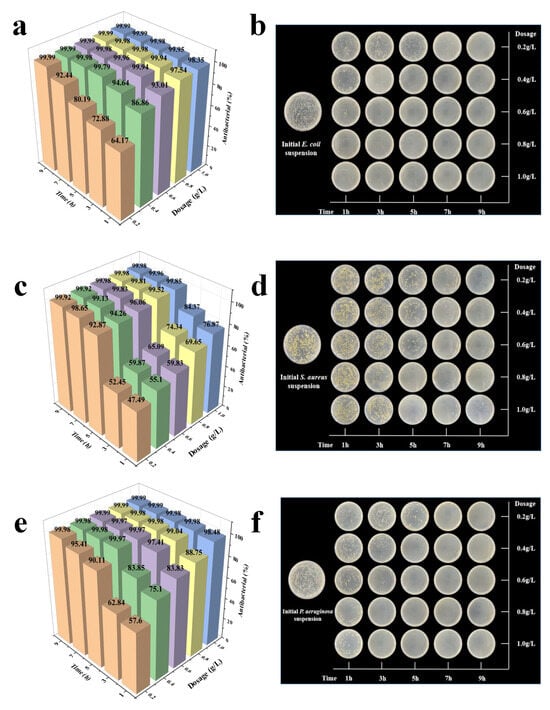

3.5. Effect of the Composite Materials on Antibacterial Ability Under Different Composite Doses and Action Duration

The antibacterial activity of C-Ag against E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa was evaluated over a range of concentrations (0.2–1.0 g/L) and a series of identical contact times (1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9 h) using the plate colony counting method. As evidenced in Figure 6, with increasing C-Ag loading and action duration, the antimicrobial effect underwent significant changes. When the action duration was 5 h, the antimicrobial rates of C-Ag against the three kinds of bacteria all reached more than 80%. For E. coli, the antimicrobial rate was over 94% (C-Ag 0.4 g/L, action time 3 h) (Figure 6a,b). For S. aureus, the antimicrobial rate exceeded 92% (C-Ag 0.2 g/L, action time 5 h) (Figure 6c,d). For P. aeruginosa, the antimicrobial rate arrived at more than 97% (C-Ag 0.6 g/L, action time 3 h) (Figure 6e,f). Increasing the C-Ag content and prolonging the action duration both considerably enhance the antimicrobial efficacy [57]. Under identical conditions, the silver-loaded biochar rendered stronger inhibitory effects against Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli) compared to Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus). The thinner peptidoglycan layer of Gram-negative bacteria renders them more susceptible to silver ion penetration, whereas the thicker cell wall structure of Gram-positive bacteria provides a more robust protective barrier [58].

Figure 6.

The impact of the composite materials on E. coli (a,b), S. aureus (c,d), and P. aeruginosa (e,f) under different composite doses and action durations. [Note: some plate photo images contain the background of cell phone, which do not affect the judgement of antibacterial efficacy].

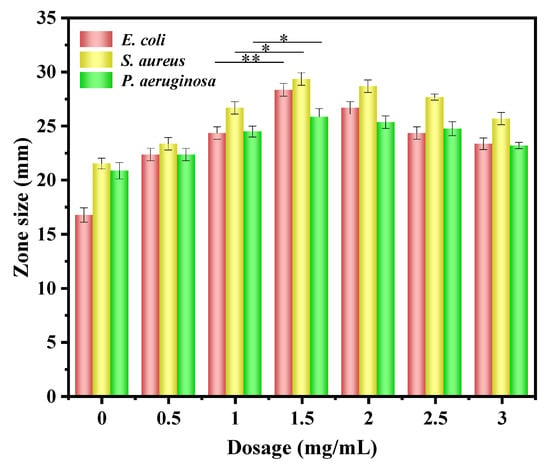

3.6. Effect of the Composite Materials with Different C-Ag Contents on Antibacterial Ability

The antibacterial activities of the composite films against E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa were evaluated by the agar disk diffusion method under standardized conditions (incubation at 37 °C for 24 h), as shown in Figure 7. The PVA/St composite film did not exhibit significant antimicrobial activity against the three tested strains, which was consistent with its own characteristic of lacking antimicrobial components [59]. Upon introducing C-Ag, the PVA/St@C-Ag composite film exerted significant antimicrobial effects, mainly due to the continuous release of Ag+ in C-Ag. Through multiple actions such as disrupting the integrity of bacterial cell membranes, interfering with DNA replication, and inhibiting the activity of respiratory chain enzymes, antimicrobial effects can be enhanced [60]. In the PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite film with CA and C-Ag, the antimicrobial effect was further considerably promoted. This is mainly associated with the coordination of carboxyl groups in CA with Ag+, which would promote dispersion and sustained-release performance. Meanwhile, the constructed acidic microenvironment might facilitate the release of Ag+ and interfere with bacterial metabolism [61]. It can also optimize the film pore structure and increase the contact of antimicrobial sites. Under the optimized condition of 1.5 g/L C-Ag content, the inhibition zone diameters of the PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite film against E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa were 28 mm, 29 mm and 26 mm, respectively, which were significantly larger than those of films with other C-Ag concentrations (p < 0.05). The antibacterial performance of this optimized film also shows promising potential when benchmarked against other recently reported advanced nanocomposites. For instance, a CMC/SA/Ag-GO film achieved inhibition zones of 21.3 mm and 18.0 mm against E. coli and S. aureus, respectively [62]. Similarly, a CLTS/SA/AgNPs/ZnOs film exhibited zones of about 19.0 mm and 18.1 mm against the same pathogens [63]. In direct comparison, our PVA/St/CA@C-Ag film at the same 1.5 g/L loading produced larger inhibition zones (28 mm and 29 mm), underscoring its competitive efficacy. However, further increasing the C-Ag content beyond this point resulted in a decrease in antibacterial activity. This reversal of efficacy is directly caused by structural changes at high filler loadings. Specifically, excessive C-Ag leads to agglomeration of AgNPs, reducing the effective specific surface area, while simultaneously densifying the composite film matrix and hindering the release and diffusion of Ag+ [64]. Therefore, the concentration of 1.5 g/L represents the optimal balance, providing sufficient well-dispersed AgNPs without inducing these detrimental structural effects. Based on the optimization results of C-Ag loading, PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite film with C-Ag concentration of 1.5 g/L was selected. The superior antibacterial performance of the C-Ag composite underscores the efficacy of the Peucedanum praeruptorum Dunn extract not only as a green reducing agent but also potentially as a source of stabilizing agents that contribute to the formation of well-dispersed and bioactive AgNPs on the biochar support [65].

Figure 7.

Diameter of the inhibition zone of PVA/St/CA@C-Ag films with different C-Ag concentrations. Asterisks denote statistical significance (* indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01).

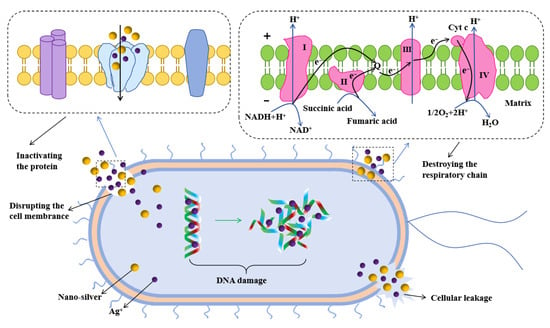

The PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite film demonstrated highly efficient antimicrobial performance through multiple synergistic mechanisms, as evidenced in Figure 8. The exposed C-Ag in the composite film might directly penetrate the cell membrane of bacteria through surface AgNPs, causing damage to the integrity of the membrane structure and causing the leakage of substances within the film. AgNPs can continuously liberate Ag+ in a humid environment, which may bind to thiol enzymes in bacteria and interfere with the activities of respiratory chain enzymes and DNA replication-related proteins [66]. Meanwhile, the CA crosslinked network enhances Ag+ activity by reducing local pH. The hydroxyl group of St coordinates with Ag+ to regulate the sustained-release kinetics. PVA matrix immobilized C-Ag to prevent AgNPs from aggregating and inactivating [67]. Beyond its primary role in direct antibacterial action, the three-dimensional CA-crosslinked network plays a critical role in modulating the environmental profile of the composite. By effectively confining the AgNPs, this structure significantly mitigates their unintended release into the environment. This controlled confinement ensures a more sustained and localized release of bioactive Ag+, thereby enhancing long-term efficacy while substantially reducing the risk of ecotoxicity. This attribute is pivotal for advancing environmentally benign antibacterial materials that align with green chemistry principles [68].

Figure 8.

Proposed antibacterial mechanism.

4. Conclusions

This work successfully fabricated PVA/St/CA@C-Ag composite films by crosslinking CA and C-Ag. Structural analyses (FTIR, XRD, and SEM) confirmed the formation of ester bonds between PVA/St and CA, as well as the homogeneous diffusion of AgNPs within the biochar matrix. The composite film manifested exceptional antimicrobial performance, with optimal activity achieved at 1.5 g/L C-Ag loading, owing to the sustained release of Ag+ and the acidic microenvironment created by CA. The film has potential application in wastewater treatment. More importantly, the design employs a synergistic strategy where CA crosslinks the polymer matrix and coordinates with silver ions, enhancing the stability of the C-Ag and promoting a sustained release profile. This integrated approach effectively mitigates nanoparticle aggregation and uncontrolled leaching, improving long-term efficacy and environmental safety. Consequently, the composite film shows promise for advanced applications beyond wastewater treatment, such as in active food packaging to extend shelf life or as antibacterial coatings. In summary, this work provides a novel and practical antibacterial material through rational design, offering a viable solution for microbial control across multiple sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and C.M.; methodology, Y.W. and C.M.; software, J.G.; investigation, C.M.; resources, J.G.; data curation, J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W. and J.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.H.; supervision, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the Frontier Technology Research and Development Plan of Jiangsu Province (BF2025080).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Analysis and Testing Center (Changzhou University) for the analysis of biomass samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kokkinos, P.; Mantzavinos, D.; Venieri, D. Current trends in the application of nanomaterials for the removal of emerging micropollutants and pathogens from water. Molecules 2020, 25, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.L.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; He, C.; Di, Y.; Lu, S.; Huang, H.; Lin, B.; Wang, D.; Fan, B. Antibacterial anthraquinone dimers from marine derived fungus Aspergillus sp. Fitoterapia 2019, 133, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, K.; Soundararajan, N.; Goud, V.V.; Katiyar, V. Cellulose nanocrystals modulate curcumin migration in PLA-based active films and its application as secondary packaging. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 9642–9657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, M.; Ghasemian, A.; Dehghani-Firouzabadi, M.R.; Mazela, B. Cellulose and its nano-derivatives as a water-repellent and fire-resistant surface: A review. Materials 2022, 15, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, B.; Ying, G. Effect of acetylation of two cellulose nanocrystal polymorphs on processibility and physical properties of polylactide/cellulose nanocrystal composite film. Molecules 2023, 28, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, S.R.; Bhosale, R.R.; Moyo, A.A.; Shinde, S.B.; Yadav, T.B.; Dhavale, R.P.; Chalapathi, U.; Patil, D.R.; Anbhule, P.V. Effect of Zn doping on antibacterial efficacy of CuO nanostructures. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202301997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.E.; Saleh, I.A.; Al-Masri, H.A.; Hamoud, Y.A.; Okla, M.K.; Shaghaleh, H. Green synthesis of copper nanoparticles from Kiwi peel: Antibacterial properties and the role of mexy gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa efflux pumps. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 6741–6764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mráz, P.; Kopecký, M.; Hasoňová, L.; Hoštičková, I.; Vaníčková, A.; Perná, K.; Žabka, M.; Hýbl, M. Antibacterial activity and chemical composition of Popular plant essential oils and their positive interactions in combination. Molecules 2025, 30, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Shen, S.; Yi, Z. Synthesis of uniform zinc peroxide nanoparticles for antibacterial application. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 86, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekol, T.A.; Beyene, B.B.; Teshale, A.T.; Mamo, S.G. Phytochemical investigation, antibacterial and antioxidant activity determination of leaf extracts of Cynoglossum coeruleum (Shimgigit). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 3946–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Tang, F.; Zhang, J.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, L. Preparation of silver nanoparticles through the reduction of straw-extracted lignin and its antibacterial hydrogel. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2025, 32, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Lian, L.; Pang, C.; Hong, L. Polymers with a thymol end group for durable antibacterial cotton fabrics. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Guo, H. Research progress of polyvinyl alcohol water-resistant film materials. Membranes 2022, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchese, C.L.; Spada, J.C.; Tessaro, I.C. Starch content affects physicochemical properties of corn and cassava starch-based films. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, B.H.; Hameed, N.J. Study of the mechanical properties of polyvinyl alcohol/starch blends. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 20, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, T.C.; Goncalves, S.A.; Marangoni Júnior, L.; Alves, R.M.V.; Andrade, V.T.; Sato, H.H.; Vieira, R.P. Incorporation of limonene oligomers into poly (itaconic acid)/starch blend films for antimicrobial and antioxidant packaging applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 8752–8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Kong, N.; Hou, Z.; Men, L.; Yang, P.; Wang, Z. Sponge-like porous polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan-based hydrogel with integrated cushioning, pH-indicating and antibacterial functions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Bharimalla, A.K.; Mahapatra, A.; Dhakane-Lad, J.; Arputharaj, A.; Kumar, M.; Raja, A.; Kambli, N. Effect of polymer blending on mechanical and barrier properties of starch-polyvinyl alcohol based biodegradable composite films. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Zubair, M.; Roopesh, M.; Ullah, A. An overview of advanced antimicrobial food packaging: Emphasizing antimicrobial agents and polymer-based films. Polymers 2024, 16, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, H.; Wan, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, D.; Zhu, M.; Chen, Y. Strong, water-resistant, and ionic conductive all-chitosan film with a self-locking structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 23797–23807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Cai, P.; Cao, X.; Chen, B.; Pan, Y. Water-resistant poly (vinyl alcohol)/ZnO nanopillar composite films for antibacterial packaging. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 50403–50413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Uppaluri, R.; Das, C. Feasibility of poly-vinyl alcohol/starch/glycerol/citric acid composite films for wound dressing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Wu, J.; Peng, T.; Li, Y.; Lin, D.; Xing, B.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L. Preparation and application of starch/polyvinyl alcohol/citric acid ternary blend antimicrobial functional food packaging films. Polymers 2017, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, S.F.; Romainor, A.N.B.; Pang, S.C.; Lihan, S. Antimicrobial starch-citrate hydrogel for potential applications as drug delivery carriers. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 101239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Govahi, M.; Litkohi, H.R. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and chitosan-coated silver nanoparticles (CS-AgNPs) using Ferula gummosa Boiss. gum extract: A green nano drug for potential applications in medicine. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 291, 138619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qian, D.; Xu, L.; Zhao, C.; Ma, X.; Han, C.; Mu, Y. Green synthesis of AgNPs and their application in chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol/AgNPs composite sponges with efficient antibacterial activity for wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 142935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Wan, S.; Meng, F.; Weng, W.; Zhang, Y. Characterization of silver nanoparticles loaded chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol antibacterial films for food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 136, 108305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, A.; Ranade, T.N.; Mali, S.N.; Ahmad Yasin, H.K.; Pratap, A. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs): Comprehensive insights into bio/synthesis, key influencing factors, multifaceted applications, and toxicity—A 2024 update. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 7549–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Szewczuk-Karpisz, K.; Sokołowska, Z.; Kercheva, M.; Dimitrov, E. Purification of aqueous media by biochars: Feedstock type effect on silver nanoparticles removal. Molecules 2020, 25, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumavat, S.R.; Mishra, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles, their characterization, and applications. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, J.; Sultana, M.S.; Dhar, P.K.; Hasan, M.K.; Dutta, S.K. Green mediated synthesis of cerium oxide nanoparticles by using Oroxylum indicum for evaluation of catalytic and biomedical activity. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 25409–25424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidu, J.; Miškovská, A.; Jarošová, I.; Čejková, A.; Maťátková, O. Antibacterial properties of silver and gold nanoparticles synthesized using Cannabis sativa waste extract against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Cannabis Res. 2025, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Ajaj, R.; Zhang, H.; Ibrahim, M.; Muhammad, N.; Al-Awthan, Y.S.; Bahattab, O.S.; Ullah, I. Green synthesis an eco-friendly route for the synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Thevetia peruviana and their biological activities. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Q.; Fan, B.; He, Y.-C. Antibacterial, antioxidant, Cr (VI) adsorption and dye adsorption effects of biochar-based silver nanoparticles–sodium alginate-tannic acid composite gel beads. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chausali, N.; Saxena, J.; Prasad, R. Nanobiochar and biochar based nanocomposites: Advances and applications. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 5, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fučík, J.; Jarošová, R.; Baumeister, A.; Rexroth, S.; Navrkalová, J.; Sedlář, M.; Gargošová, H.Z.; Mravcová, L. Assessing earthworm exposure to a multi-pharmaceutical mixture in soil: Unveiling insights through LC–MS and MALDI-MS analyses, and impact of biochar on pharmaceutical bioavailability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 48351–48368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuny, B.N.; Kospa, D.A.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Gebreil, A. Stable polyethylene glycol/biochar composite as a cost-effective photothermal absorber for 24 hours of steam and electricity cogeneration. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 31077–31091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Cheng, Y.; Liang, X.; Yang, Z. Synthesis of activated carbon loaded nanosilver and study of water corrosion resistance and antimicrobial properties. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 52, 104890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskuzhina, L.; Batasheva, S.; Kryuchkova, M.; Rozhin, A.; Zolotykh, M.; Mingaleeva, R.; Akhatova, F.; Stavitskaya, A.; Cherednichenko, K.; Rozhina, E. Advances in the toxicity assessment of silver nanoparticles derived from a Sphagnum fallax extract for monolayers and Spheroids. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, C.R.; Maharana, S.; Mandhata, C.P.; Bishoyi, A.K.; Paidesetty, S.K.; Padhy, R.N. Biogenic silver nanoparticle synthesis with cyanobacterium Chroococcus minutus isolated from Baliharachandi sea-mouth, Odisha, and in vitro antibacterial activity. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, B.; Zhao, R.; Wang, X.; Pan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ge, B. Adsorption behavior and performance of ammonium onto sorghum straw biochar from water. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Ding, J.; Yan, X.; Yan, W.; He, M.; Yin, G. Plasticization of cottonseed protein/polyvinyl alcohol blend films. Polymers 2019, 11, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur, A.; Rodrigues, M.; Capanema, N.; Carvalho, S.; Gomes, D.; Mansur, H. Functionalized bioadhesion-enhanced carboxymethyl cellulose/polyvinyl alcohol hybrid hydrogels for chronic wound dressing applications. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 13156–13168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Hong, G.; Mazaleuskaya, L.; Hsu, J.C.; Rosario-Berrios, D.N.; Grosser, T.; Cho-Park, P.F.; Cormode, D.P. Ultrasmall antioxidant cerium oxide nanoparticles for regulation of acute inflammation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 60852–60864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, Y.; Bisauriya, R.; Goswami, R.; Hlaing, A.; Moe, T. Hydrothermal synthesis of SnO2/cellulose nanocomposites: Optical, Structural, and morphological characterization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhao, H.; Song, X.; Ji, Z.; Xie, C.; Chen, F.; Meng, Y. Biomimetic robust starch composite films with super-hydrophobicity and vivid structural colors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, N.; Ahmed, N.Y.; Mal, S.S.; Bharath, P.A.S.; Zhuo, G.-Y.; Noothalapati, H.; Managuli, V.; Mazumder, N. Assessment of biocompatibility for citric acid crosslinked starch elastomeric films in cell culture applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emek, M.; Şahin, E.İ.; Ibrahim, J.E.F.; Kartal, M. Electromagnetic Shielding Performance of Ta-Doped NiFe2O4 Composites Reinforced with Chopped Strands for 7–18 GHz Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kadi, F.K.; Adbulkareem, J.F.; Azhdar, B.A. Evaluation of the mechanical and physical properties of maxillofacial silicone type A-2186 impregnated with a hybrid chitosan–TiO2 nanocomposite subjected to different accelerated aging conditions. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, Q.; Yu, R.; Zhang, H.; Nie, F.; Zhang, W. Enhancing K2S2O8 electrochemiluminescence based on silver nanoparticles and zinc metal–organic framework composite (AgNPs@ZnMOF) for the determination of l-cysteine. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23437–23446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürler, N.; Paşa, S.; Erdoğan, Ö.; Cevik, O. Physicochemical properties for food packaging and toxicity behaviors against healthy cells of environmentally friendly biocompatible starch/citric acid/polyvinyl alcohol biocomposite films. Starch-Stärke 2023, 75, 2100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Tan, Y.; Ye, D.; Jia, Y.; Liu, P.; Yu, H. High-water-absorbing calcium alginate fibrous scaffold fabricated by microfluidic spinning for use in chronic wound dressings. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 39463–39469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, J.-C.; Yang, T.-Y.; Hung, C.-C.; Shih, C.-J. Silica-based silver nanocomposite 80S/Ag as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans inhibitor and its in vitro bioactivity. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 19, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Tang, L.; Hu, J.; Jiang, M.; Shi, X.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Pan, X. Removal of toxic metals from aqueous solution by biochars derived from long-root Eichhornia crassipes. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Lee, W.; Choi, J.W.; Bumbudsanpharoke, N.; Ko, S. A facile green fabrication and characterization of cellulose-silver nanoparticle composite sheets for an antimicrobial food packaging. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 778310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikhao, N.; Ounkaew, A.; Srichiangsa, N.; Phanthanawiboon, S.; Boonmars, T.; Artchayasawat, A.; Theerakulpisut, S.; Okhawilai, M.; Kasemsiri, P. Green-synthesized silver nanoparticle coating on paper for antibacterial and antiviral applications. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 9651–9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, C.-Y.; Wang, Z.-X.; Xie, H. Silver nanoparticles: Synthesis, medical applications and biosafety. Theranostics 2020, 10, 8996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Xie, F.; Geng, L.; He, R.; Sun, M.; Ni, T.; Xu, P.; Xing, C.; Peng, Y.; Chen, K. Micro-electro nanofibrous dressings based on PVDF-AgNPs as wound healing materials to promote healing in active areas. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.; Zafar, H.; Mahmood, A.; Niazi, M.B.K.; Aslam, M.W. Starch-capped silver nanoparticles impregnated into propylamine-substituted PVA films with improved antibacterial and mechanical properties for wound-bandage applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tăbăran, A.-F.; Matea, C.T.; Mocan, T.; Tăbăran, A.; Mihaiu, M.; Iancu, C.; Mocan, L. Silver nanoparticles for the therapy of tuberculosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 2231–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, F.; Hu, X.; Lu, J.; Sun, X.; Gao, J.; Ling, D. Responsive assembly of silver nanoclusters with a biofilm locally amplified bactericidal effect to enhance treatments against multi-drug-resistant bacterial infections. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Sethy, C.; Kundu, C.N.; Tripathy, J. Synergetic reinforcing effect of graphene oxide and nanosilver on carboxymethyl cellulose/sodium alginate nanocomposite films: Assessment of physicochemical and antibacterial properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yao, G.; Li, K.; Ye, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J. Preparation, characterization, and antibacterial application of cross-linked nanoparticles composite films. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanlalveni, C.; Lallianrawna, S.; Biswas, A.; Selvaraj, M.; Changmai, B.; Rokhum, S.L. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts and their antimicrobial activities: A review of recent literature. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 2804–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwada, C.A.; Ndivhuwo, P.S.; Matshetshe, K.; Aradi, E.; Mdluli, P.; Moloto, N.; Otieno, F.; Airo, M. Phytochemical-assisted synthesis, optimization, and characterization of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial activity. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 14170–14181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Nishio Ayre, W.; Jiang, L.; Chen, S.; Dong, Y.; Wu, L.; Jiao, Y.; Liu, X. Enhanced functionalities of biomaterials through metal ion surface modification. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1522442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, R.-Z.; Yi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hao, L.-M.; Wu, J.-H.; Hu, G.-H.; He, H. Facile and green fabrication of electrospun poly (vinyl alcohol) nanofibrous mats doped with narrowly dispersed silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 3937–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Fan, B.; He, Y.-C. UV-blocking, antibacterial, corrosion resistance, antioxidant, and fruit packaging ability of lignin-rich alkaline black liquor composite film. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).