Abstract

This study explores the production of hydrates with binary (CH4/C2H6) gaseous mixtures, varying the concentration of each species from 25 to 75 vol%. The thermodynamics of this process are explored in detail, and the achieved results are explained in terms of cage occupancy and compared with the phase boundary equilibrium conditions of pure methane and pure ethane hydrates. The addition of ethane is found to not contribute significantly to the quantity of gas captured in hydrates. Conversely, it delays the massive growth of hydrates, shifting the process towards conditions supporting the formation of pure methane hydrates. The presence of C2H6 molecules within the hydrate lattices improved their overall stability and avoided the dissociation of water cages even under temperature increases (from the conditions measured at the end of formation) up to 14.40 °C. This latter property makes ethane a viable support species for the solid storage of energy gases in the form of hydrates.

1. Introduction

Gas hydrates consist of particular clathrate structures where an ordered and crystalline lattice of water molecules spontaneously grows in the presence of specific gas molecules, physically trapping them within solid and polyhedral cages [1]. Only Van der Waals forces are established between the crystalline network formed by hydrogen-bonded water molecules and the gas species. Since the energy required to break Van der Waals bonds is equal to 0.3 kcal/mol, gas molecules are considered only physically and not chemically trapped within the hydrate lattice [2].

Gas hydrates were initially explored for their tendency to spontaneously grow within natural gas pipelines, thus causing undesired gas blockages; then, from the mid-1930s onwards, enormous deposits of natural gas were found to be widespread in the form of hydrates, meaning that they started to be considered as a potential new alternative energy source [3,4]. Huge reservoirs of natural gas hydrates were gradually discovered in natural areas demonstrating conditions suitable for their formation and stability, based on factors such as the availability of water and suitable gas species, relatively high pressures, and low temperatures. Therefore, hydrate reservoirs were discovered in offshore areas, such as deep oceans and continental margins, where approximately 97% of the discovered reservoirs are sited, and permafrost regions, which comprise the remaining 3% [5]. The main offshore natural reservoirs were documented in the South China Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the Japan Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Bering Strait [6], while the most relevant deposits in permafrost regions can be found in Alaska, Siberia, and the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau [7]. Gas hydrates have a high energy density: the combustion of one cubic meter of methane hydrates may produce up to 33.79 MJ of energy; considering the estimated quantity of natural gas hydrates diffused worldwide, approximately equal to 1015–1017 m3, this alternative energy source theoretically allows the production of more than twice the amount of energy still contained in all of the conventional fossil energy sources currently known about and available [8].

Different methodologies have been developed for the recovery of methane from natural gas hydrate reservoirs [9], including depressurization [10,11], thermal stimulation [12,13], chemical inhibitor injections [14,15], and a combination of these techniques [16]. Depressurization and thermal stimulation are used to modify the local thermodynamic conditions, thus moving hydrates from the corresponding stability regions outside and causing the release of methane. Meanwhile, the injection of chemical inhibitors directly intervenes in the hydrate lattice, making the local conditions no longer suitable for its stability. In addition to energy production from naturally existing reservoirs, the production and melting of gas hydrates can be advantageously exploited in numerous applications. The storage of carbon dioxide, in the form of hydrates, in deep oceans is considered one of the most promising options for the final disposal of this greenhouse gas: its storage capabilities can be assumed to be unlimited and the pressure/temperature conditions may ensure high stability for the solid CO2-containing lattice, making this solution significantly safer than CO2 storage in inland aquifers [17]. Moreover, in the case of accidental losses, CO2 molecules would dissolve in the water, with the consequent release of these molecules into the atmosphere being negligible [18].

Hydrates can also be used for storing energy gases [19]. Methane can be stored as a liquid at −83 °C and 5 MPa [20,21]. When considering the same pressure, methane can easily be captured in hydrates at temperatures greater than 0 °C [22]. Similarly, hydrates can also be considered for hydrogen storage. This latter option was proposed for the first time in the 1990s [23]; however, the pressures required for this process (approximately equal to 200 MPa at room temperature and more than 30 MPa at temperatures approaching 0 °C [24]) were immediately considered unattractive. However, the usage of appropriate chemical promoters, and/or the capture of hydrogen in mixtures with other appropriate molecules, was found to be capable of reducing the required pressures by more than one order of magnitude, thus increasing the interest in such a prospective approach again [25,26,27,28].

Due to the similarity of their physical properties to those of ice, gas hydrates can also be used for seawater desalination and, more generally, for wastewater treatment [29]. During their formation and growth, these structures do not chemically include ions or, if present, impurities within their lattice. Once formed, hydrates can easily be separated from the remaining liquid phase, and their melting allows us to obtain fresh water (with an efficiency up to 98%) [30]. In the case of desalination, the removal efficiency depends on the ion size and charge [31]. In greater detail, the lower the charge and the larger the ionic size, the more effective the treatment is [32,33,34].

The same property allows us to also consider hydrate production for food concentration [35]. The removal of water to obtain concentrated juices is often carried out via evaporation and represents the most costly step of the process [36]. In addition, evaporation cannot be applied when volatile species are present, meaning that the use of a membrane becomes mandatory [37,38].

Cold storage is considered an emerging sector and a viable solution for reducing the gap that exists between electricity production and consumption [39]. The most widespread techniques for cold storage are based on liquid water, ice, eutectic salts, and gas hydrates [40]. With the exception of liquid water, the other options are based on phase change processes. In comparison with ice, the advantage of using hydrates is the possibility of producing them at temperatures higher than 0 °C [41]. Moreover, hydrates are less expensive than eutectic salts and do not cause corrosion [42,43].

In addition to the technologies described above, hydrates can also be used for several further processes, such as gas mixture separation and others [44]. Hydrate-based gas separation techniques (HBGS) are attracting growing attention, since high selectivity can theoretically be reached and the process is environmentally friendly [45,46,47,48]. Depending on the formation of specific hydrate structures, possessing different water cages and ratios between large and small cavities, some gas species can easily be captured in the available cavities, while some other species, initially present in the same mixture, are not involved in the enclathration process [49]. The separation process can also be carried out between species capable of forming hydrates. In this latter configuration, the different formation conditions and the respective partial pressures play a key role in determining the process’ feasibility and efficiency [50].

In detail, this research work explores the possibility of producing hydrates to store methane within solid structures and at mild and competitive pressures. Hydrates are capable of capturing up to 172 m3 of methane (measured at std conditions) in only one cubic meter of crystalline lattice [3]. Based on this estimation, the combustion of one cubic meter of methane hydrate could generate up to 33.79 MJ of energy [51], thus making hydrates a potentially high-energy-density storage carrier. The hosting medium (water) is inexpensive; moreover, the transportation phase would also be easier, since energy gases are stored in solid form. However, the usage of clathrate hydrates as storage carriers for energy gases is still a long way from technical maturity [52]. The reason for this can be attributed to the stochastic features of their formation: their storage capacity may vary within a certain range, even if the process conditions are kept constant [53]. In particular, the most relevant differences are stochastically generated during the initial nucleation phase [54]. The storage capacity can be identified in relation to the hydration number of the hosting lattice. The hydration number can be described as the ratio between water and guest molecules in the hydrate phase. Methane can occupy all cavities forming the sI unit cell, and the corresponding may reach 5.75. Conversely, when only the larger cavities can be occupied, as is the case for carbon dioxide, the hydration number is theoretically equal to 7.67. However, these values are true under the assumption of 100% cage occupancy, which is rarely achievable. As a consequence of this, the hydration number is usually higher, reaching 19 for sI hydrates. A lower cage occupancy often means reduced stability for the hydrate lattice, and consequently higher storage costs.

Pursuing the feasibility of energy gas storage in the form of hydrates means ensuring, at the same time, the possibility of producing hydrates under competitive thermodynamic conditions and reaching hydration number values that are as low as possible. These two goals can be achieved together by introducing appropriate guest species in mixtures with methane.

Despite the abundance of data describing the formation and melting conditions of hydrates containing methane, there is a substantial lack of experimental data describing the same processes in the presence of binary mixtures containing small-chain hydrocarbons. This study aims to provide pressure–temperature data that is exploitable for gas storage applications.

As explained later in this paper, methane molecules preferentially occupy smaller cavities in sI hydrates. The addition of species capable of forming hydrates at relatively low pressures and capable of easily fitting into larger cavities could allow us to reach the goals of storing energy gases in the form of hydrates, reducing their consumption, and completely avoiding the utilization of chemical additives. In this sense, highly suitable guest species include ethane, propane, and isobutane. These gases are naturally present (usually at low concentrations) in natural gas mixtures. If their concentration does not exceed certain limits, gas separation/purification processes after storage can be avoided. Previous studies confirmed the tendency of these gases, when added into mixtures with guest species with a smaller molecular diameter, to promote the capture of gas and to widely increase the stability of the hydrate lattice [55,56]. The research discussed in Gambelli et al. (2024) [57] deals with hydrate formation and dissociation with a binary CH4/C3H8 (85/15 vol%) mixture. The addition of propane enhanced the gas capture process and reduced the pressure required for phase equilibrium in pure methane hydrates to 19.42 bar. The results also confirmed a certain kinetic promotion due to the addition of propane. Specifically, the formation rate increased from 3.9 × 10−4 mol/min to 7.410−4 mol/min.

However, this synergistic effect is strongly related to the smaller associated guest species; for instance, propane was found to be capable of promoting the capture of methane, while it did not provide any valuable effects in the enclathration of carbon dioxide [57]. This study confirmed that the addition of propane, in mixtures with methane or carbon dioxide, impacted the overall amount of gas captured. Specifically, when mixed with methane, it increased the quantity of gas captured to 0.106 mol, while when mixed with carbon dioxide, the amount of gas captured decreased to about 0.057 mol.

The present study explores the production of hydrates with binary (CH4/C2H6) gaseous mixtures at different concentrations to establish the role of ethane when capturing methane in water cages. The thermodynamic evolution of this process was observed and described, while the promoting effect, due to the added guest species, was quantified in terms of methane captured and energy accumulation.

2. Interaction Between CH4 and C2H6 Molecules When Forming sI Hydrates

In nature, three different typologies of hydrate structures have been found to exist: the cubic Structure I (sI), the cubic Structure II (sII) and the hexagonal Structure H (sH). The formation of a specific structure is mainly a function of the species (or the mixture of different compounds) involved in the process [58,59]. Each structure consists of the aggregation of five possible polyhedral base cavities, commonly denoted with the nomenclature “nimi”, where “ni” indicates the number of edges on a specific face, while “mi” is the number of faces having “ni” edges. The unit cell of sI contains two pentagonal dodecahedrons (512, the smallest typology of cavity) and six tetrakaidecahedrons (51262). This structure is the most widespread in nature and is the one spontaneously formed by methane and carbon dioxide molecules [60]. The cubic sII contains sixteen 512 cages and eight hexakaidecahedrons (51264). The ratio between large and small cavities is crucial for both replacement purposes and for gas storage applications, being equal to 3 in sI and to 2 in sII [61]. Finally, the hexagonal sH is based on three 512 cages, two irregular dodecahedrons (435663), and one icosahedron (51268). The peculiarity of this latter structure is that, unlike sI and sII, a minimum of two different species is always required to make its formation feasible.

The ability of guest species to fit into a specific hydrate cavity is mainly a function of their size and geometry. To enter into a cavity, the gas compound must have a molecular diameter lower than that of the cavity, but at the same time, its size needs to be as close as possible to that of the corresponding cavity; otherwise, stability would not be possible and the enclathration process would be prevented. However, if the molecular and cage diameters are approximately the same, the capture process might require geometrical distortion. This is why the CO2/CH4 process has a maximum theoretical efficiency equal to 75%: due to its molecular diameter, carbon dioxide can easily replace methane molecules only in large cavities of sI, which are three times more prevalent in the hydrate structure than small cavities.

The ability of a guest molecule to fit into a specific cavity can be expressed in terms of the cage filling ratio, or the ratio between molecular and cavity diameters. The filling ratios for methane, carbon dioxide, ethane, and propane in the cavities forming sI and sII hydrates are indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Molecular diameters (md) of CH4, CO2, C2H6, and C3H8 and their corresponding cage filling ratios (molecular diameter/cavity diameter—dimensionless) in the cavities forming sI and sII hydrates.

To enter into a certain cavity, the filling ratio has to be equal to or lower than one. Due to its molecular diameter, ethane can form both sI and sII, but it can only occupy large cavities, since its filling ratio for small cavities is higher than one (1.08 in sI and 1.1 in sII). Similarly to ethane, carbon dioxide can also form both structures and occupy large cavities. The only difference is that it can also enter into the small 512 cavities of sI, even if geometrical distortion is required. Therefore, pure methane, pure ethane, and pure carbon dioxide spontaneously form sI, while pure propane leads to the formation of sII.

Binary (CH4/CO2) mixtures form sI hydrates. Within the crystalline framework, methane molecules occupy the small cavities, while carbon dioxide molecules fit into the large cavities. In theory, these mixtures could also lead to the production of sII hydrates. However, the filling ratio of CO2 molecules in 51264 is mostly lower than that in 51262, making sI the most stable hydrate structure for this mixture. With the increase in CO2 concentration, the formation conditions gradually become milder, since this species requires lower pressure (at the same temperature) to be captured in water cages. Such a condition must consider the ratio between large and small cages in the sI hydrate, equal to 3:1; therefore, at CO2 concentrations higher than 75%, the capture of methane in mixed hydrates will no longer be promoted and the formation conditions will remain unchanged.

Similarly, CH4/C2H6 mixtures are also suitable for the production of sI hydrates. Similarly to the previous mixture, methane molecules occupy the small cavities, while ethane molecules the large cavities. However, these mixtures are also suitable for the production of sII, with consequential benefits in terms of gas storage per unit of hydrate produced [1]. The growing interest in hydrate stability, due to the presence of binary mixtures containing small-chain hydrocarbons, as seen in those explored in this study, is demonstrated by the current literature, where the results achieved via MD simulation with the same gas mixtures can be found [55,56], being compared with experimental findings. In fact, the filling ratio for methane molecules in small 512 cavities increases from 0.855 in sI to 0.868 in sII. At the same time, the filling ratio of ethane molecules in large cavities drops from 0.939 to 0.826. Therefore, both species show an ideal filling factor in the case of sII hydrates.

Finally, propane molecules can exclusively fit into the large cavities of sII, since the filling ratio related to small cavities is higher than one. For this reason, the only synergistic option consists of coupling it with methane for the production of sII [57,62,63].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Apparatus and Materials

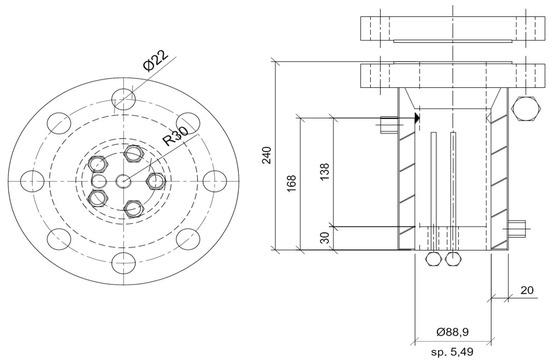

The experimental work conducted in this study consisted of producing and melting hydrates with methane/ethane mixtures at different concentrations in order to determine the role of ethane as a key parameter for gas storage, the quantity of hydrates formed, and the thermodynamic conditions required for the capture of gas molecules in water cages. Based on the scope of this study, a small-scale reactor was considered, consisting of a pressurized unstirred device (by Metalserbatoi, Perugia, Italy) with a cylindrical shape and an internal volume equal to 1 dm3 (7.79 cm diameter and 21 cm height). Figure 1 provides a technical scheme of the reactor.

Figure 1.

Technical scheme of the reactor used for CH4/C2H6 hydrate production. Values are given in [mm].

The reactor was entirely made of 316SS, enabling it to reach internal pressures of up to 90 bar. The gas species were injected from the bottom in order to better permeate porous sediments when present inside. Two channels could be used for this scope. The upper flange contained five channels and hosted all of the required sensors, a safety valve, and the gas ejection pipe. Its tightness was guaranteed with mono-use spiro-metallic gaskets (model DN8U PN 10/40 316-FG C8 OR). As visible in Figure 1, the reactor had an integrated coil for the efficient flow of refrigerant fluids when fast subcooling was required. The internal temperature was measured with three Type K thermocouples with a class accuracy of 1. The thermocouples (by TC Direct, Hillside, IL, USA) were positioned at different depths within the reactor (at 5, 10, and 15 cm from the top) to detect the possible occurrence of internal gradients, especially during hydrate formation. Pressure was measured with a digital manometer, model MAN-SD (by Kobold), with a class accuracy equal to ±0.5% of the full scale. The sensors were connected to a data acquisition system (by National Instruments) and elaborated in LabView (directly provided by University). A picture of the assembled apparatus is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

(Left): Picture of the reactor, equipped with pressure/temperature sensors and connected to gas cylinders. (Right): Zoomed-in image of the upper flange, with particular focus on the gas ejection channel.

The gas ejection channel was designed to allow for the fast ejection of the internal gaseous phase and, when required, for the extraction of small gas samples for use in GC analyses. Therefore, it contained a pressure reducer that could be used to move small portions of gas at a low pressure within a secondary volume enclosed with a porous septum, where it could be easily withdrawn with a syringe.

The whole system was placed in a cooled room to maintain consistent conditions and to keep all components at the control temperature, with an accuracy equal to ±0.1 °C. More detailed information about the experimental apparatus can be found elsewhere in the literature [57,62,63].

Ethane and methane, with purity degrees equal to 99.99%, were provided by Nippon Gases and were used in the experiments.

3.2. Procedure

Gas hydrates were formed and melted according to procedures already tested and described in detail in previous studies [57,62]. The reactor was initially filled with demineralized water and porous silica sand and the flange was then sealed. A porous medium was inserted to ensure the production of hydrates throughout the whole reactor and not exclusively at the gas–liquid interface. A detailed description of this setup can be found elsewhere in the literature [57,62]. Water was inserted in excess in order to make gas the limiting factor in the process, thus ensuring the highest possible gas capture and better emulating the phase boundary equilibrium conditions for the system.

The methane/ethane mixture was inserted through opposite channels, and then gas injection continued until the desired internal pressure was reached. Gas was injected at sufficiently elevated temperatures to completely avoid the production of hydrates during gas injection. As the study focused on the thermodynamics of the process and not on its kinetics, the initial pressure was allowed to differ between the various tests, as a function of the gas mixture used, without causing inaccuracies in the results. Therefore, we decided to focus on the thermodynamic region existing between the phase equilibrium conditions of pure methane and pure ethane hydrates.

The production of hydrates was obtained by gradually lowering the temperature; the decreasing gradient was fixed between 0.1 and 0.2 °C/h. With the lowering of temperature, the system entered into the thermodynamic region previously mentioned and the reaction took place under conditions depending on the mixture tested and after a certain delay, attributable to the induction period. Formation finished when the pressure definitively stabilized in correspondence with the lowest temperature fixed for the system.

The same procedure was followed for melting hydrates: the internal temperature was gradually increased until complete dissociation of hydrates was observed and the same pressure–temperature conditions present within the reactor before the formation process took place were reached.

4. Results and Discussion

This section describes the production of binary (CH4/C2H6) gaseous hydrate mixtures at three different concentrations:

- (i)

- CH4/C2H6 75/25 vol%;

- (ii)

- CH4/C2H6 50/50 vol%;

- (iii)

- CH4/C2H6 25/75 vol%.

The different results obtained are then compared, including with the phase equilibrium conditions of pure methane [64,65,66,67,68] and pure ethane [69,70,71,72,73] hydrates, defined according to previous studies and the current literature. The various concentrations were selected to respect the different proportions of large and small cavities, both in sI (3:1) and in sII (1:1). Finally, the last concentration was used to observe what happens when working with an excess of ethane. Several tests were carried out for each concentration selected in order to ensure the reliability of results. In this section, three tests for each concentration are described.

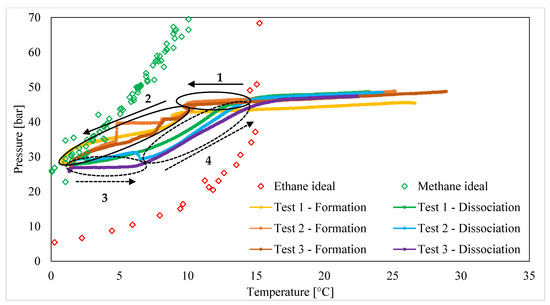

Figure 3 describes the production of hydrates with CH4/C2H6 (75/25 vol%) mixtures. In the same diagram, the phase boundary conditions of pure methane and pure ethane hydrates are visible.

Figure 3.

Formation and melting conditions measured for CH4/C2H6 (75/25 vol%) hydrates.

In this figure, the process evolution is indicated with black arrows: continuous lines refer to hydrate formation, while dotted lines refer to hydrate dissociation. As expected, the process took place under thermodynamic conditions between those describing the phase equilibrium of pure methane and pure ethane hydrates. The different experiments showed high similarity among each other, proving the repeatability of results. Clearly, the dissociation curves showed a higher similarity degree than the formation curves, due to the stochastic tendencies of this latter process.

Both formation and dissociation can be divided into two main steps. In Figure 3, those related to hydrate formation are highlighted with black continuous circles and are numbered as steps “1” and “2”, while the dissociation steps are marked with black dotted circles and are numbered as steps “3” and “4”.

Once the phase boundary line of pure ethane hydrates was passed, the formation of hydrates did not start immediately and the P-T trend remained equal to that observed outside of the stability region (to the right of the phase boundary line, as previously mentioned). This step, which can be associated with the induction period, is indicated in Figure 3 with the number “1”. The induction period can be considered as the time that elapsed from the beginning of the massive production of hydrates to when the system entered into the conditions suitable for the production and stability of these compounds [74,75]. The present study deals with the thermodynamics of hydrate formation, and the induction time was therefore not quantified. However, in each group of tests, as discussed in this section, pressure initially decreased exclusively as a function of temperature, which accelerated its reducing trend, depending on the production of hydrates. However, this deviation always occurred after the system entered into the thermodynamic region between the phase boundary curves of pure methane and pure ethane hydrates, while it never started near the phase boundary line of pure ethane hydrates. This aspect also allowed us to confirm the production of mixed hydrates instead of structures containing a single species. The massive production of hydrates signified a marked deviation from experimental P-T curves; in particular, pressure started to drop faster until it reached its minimum value (step “2”). During this step, the process was only partially governed by the main driving thermodynamic forces, with the most relevant differences between the various tests being determined by the stochastic nature of the process and the heat and mass transfer properties of the system, which obviously did not remain exactly equal among the various tests [76].

The dissociation process started after the room was allowed to warm up. The melting of hydrates started with a certain delay and began only after the internal temperature was higher than that registered at the end of hydrate formation (step “3”). This property can be attributed to the ability of the system to preserve itself, even under conditions unsuitable for the stability of hydrates (the most superficial layers limited heat transfer through the most internal layers, thus preventing their melting for a certain time period), and to the presence of ethane molecules, which favored the permanence of the hydrate lattice until the system approached P-T conditions typical of pure ethane hydrate phase boundary conditions. Finally, the massive dissociation of hydrates took place (step “4”) and pressure increased again, until reaching the values registered before hydrate formation. The experimental curves depict a melting trend comparable to that of pure ethane hydrates. At the right-hand side of the equilibrium curve of pure ethane hydrates, hydrates are not present, and the P-T trend exclusively depends on the equation of state for gases.

The experiments reveal that the addition of one-fourth ethane to the mixture allowed the formation and melting conditions to be shifted towards milder pressures. Hydrates formed and melted under conditions between those described for pure methane and pure ethane hydrate formation. Independently of the typology of the structure formed, ethane was the limiting species. Therefore, methane in excess remained in the gaseous phase since the thermodynamic conditions were unsuitable for the production of pure methane hydrates. The production of hydrates continued until the system approached the equilibrium curve of pure methane hydrates, proving the gradual consumption of ethane, which made the required formation conditions harder to achieve. Conversely, the presence of ethane molecules within the crystalline lattice increased the stability of structures and dissociation began at temperatures significantly higher than those needed to complete the formation of hydrates. The improved stability of hydrate structures, due to the inclusion of ethane molecules, will be explored further in the following paragraphs.

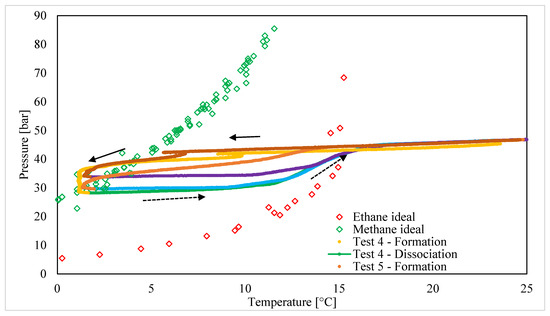

Figure 4 depicts the production and melting of hydrates by using binary CH4/C2H6 (50/50 vol%) mixtures.

Figure 4.

Formation and melting conditions measured for CH4/C2H6 (50/50 vol%) hydrates.

Moreover, at this concentration, the four different steps previously described are clearly visible, with some differences. The massive production of hydrates occurred with a certain delay compared to Tests 1–3 (C2H6 25 vol%): pressure started to decrease (as a consequence of hydrate formation) only after the local conditions approached the phase equilibrium curve of pure methane hydrates. Moreover, the formation process partially occurred under thermodynamic conditions also suitable for the production of pure ethane hydrates. This latter event can be partially attributed to the prolonged induction period: the massive production started only after the local conditions were already close to the phase curve of methane hydrates. At the same time, Test 5 showed a shorter induction period and, similarly to the other tests, completed the formation phase in a region also suitable for the production of pure methane hydrates.

The higher concentration of ethane in the mixture strengthened the preservation of the structure at the beginning of dissociation: the melting of hydrates started at temperatures higher than the corresponding values measured at the end of hydrate formation. The following melting of water cages demonstrated a trend closer and more adherent to the phase equilibrium curve of pure ethane hydrates. Finally, outside of the region of stability for pure ethane hydrates, the P-T curves assumed a trend completely overlapping with the same curves before the formation process took place.

Despite the smaller quantity of methane in the gaseous mixture, at this specific concentration (CH4/C2H6 50/50 vol%), the formation process was mainly affected by this species. Conversely, the dissociation trend can mostly be attributed to the increased concentration of ethane in the mixture.

As visible in the following paragraphs, the overall quantity of hydrates produced remained close to that obtained with CH4/C2H6 75/25 vol%.

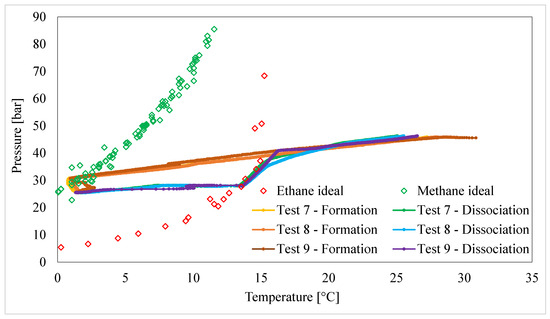

Finally, Figure 5 describes the production and dissociation of hydrates using the last binary mixture tested in this study: CH4/C2H6 25/75 vol%.

Figure 5.

Formation and melting conditions measured for CH4/C2H6 (25/75 vol%) hydrates.

The results observed with this latter mixture (Tests 7 to 9) agree with the previous tests (Figure 3 and Figure 4). In particular, the induction period continued until the process conditions reached those of pure methane hydrates’ phase equilibrium; the massive production of hydrates occurred under the same formation requirements as methane hydrates. The same is true for the dissociation process: hydrates did not start melting until the system reached the profile of pure ethane phase boundary equilibrium. The hydrates melted following the behavior of pure ethane hydrates. Similarly to the previous experiments, at the right-hand side of the equilibrium curve of ethane hydrates, the absence of any internal process causes the initial and final experimental curves to overlap with each other.

From these diagrams, it can be concluded that increasing concentrations of ethane lead to longer induction periods and stronger self-preservation tendencies of the system and, at the same time, gradually shift the formation conditions towards the phase boundary curve of pure methane hydrates and the melting conditions towards the phase boundary curve of pure ethane hydrates.

The following tables provide numerical data measured during hydrate melting; Table 2 describes the mixture having 25 vol% C2H6, Table 3 provides data for the mixture with 50 vol%, and Table 4 provides data for the mixture with 75 vol% C2H6.

Table 2.

Pressure–temperature values measured during the dissociation of hydrates formed with the CH4/C2H6 (75/25 vol%) mixture.

Table 3.

Pressure–temperature values measured during the dissociation of hydrates formed with the CH4/C2H6 (50/50 vol%) mixture.

Table 4.

Pressure–temperature values measured during the dissociation of hydrates formed with the CH4/C2H6 (25/75 vol%) mixture.

Based on the evidence emerging from the P-T evolution of each experiment, three main factors were identified and quantified: the quantity (moles) of hydrates formed, the induction period, and the preservation properties of hydrates. The quantity of hydrates formed was calculated according to Equation (1):

where VPORE [cm3] is the internal volume available for the production of hydrates. The porosity of sand was measured with a porosimeter, model Thermo Scientific Pascal 140, and is equal to 34%. Z represents the compressibility factor, calculated according to the Peng–Robinson equation. ρHYD is the ideal molar density of hydrates, equal to 0.91 g/cm3 [77,78]. Pressure and temperature are indicated with “P” and “T”, while the beginning and end of hydrate formation are identified with the subscripts “i” and “f”. In further detail, the compressibility factor (Z) was calculated according to Fitzgerald and colleagues [79], as follows:

where

with

For each mixture, specific values of the acentric factor (w), critical temperature (Tc), and critical pressure (Pc) were considered. These values are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Values of w, Tc, and Pc used for Z calculation and its corresponding values for each mixture.

The induction period and self-preservation of hydrates were only evaluated thermodynamically; each parameter was described in terms of ΔT. The first parameter was evaluated by considering the temperature measured when the system overtook the phase equilibrium curve of pure ethane hydrates and the temperature measured when a marked deviation in pressure, compared to the trend shown in the absence of formation (at the right-hand side of the curve previously mentioned), was observed. Similarly, the ability of the hydrate lattice to preserve itself was quantified in terms of temperature, taking into account the temperatures measured at the end of hydrate formation and during dissociation, as soon as pressure started to increase intensively, due to the melting of hydrates. Therefore, both the induction period and preservation effects were quantified in terms of the temperature delay observed before hydrates started to massively grow/melt within the reactor.

The quantity of hydrates formed was calculated according to Equation (1), where pressure and temperature values referring to the beginning and end of hydrate formation were defined as the mean of values measured in all the experiments carried out with the same mixture. The same quantities were achieved:

- − CH4/C2H6 (25/75 vol%) mixture: 0.195 mol;

- − CH4/C2H6 (50/50 vol%) mixture: 0.197 mol;

- − CH4/C2H6 (75/25 vol%) mixture: 0.255 mol.

The quantity of gas captured in water cages gradually increased with the growing concentration of methane in the gaseous mixture. In particular, at methane concentrations equal to 25 vol% and 50 vol%, respectively, 0.195 and 0.197 moles of gas were involved in the production of hydrates. Conversely, when the gas mixture consisted of 75 vol% methane, this quantity increased up to 0.255 moles. Since the thermodynamic conditions present within the reactor during each experiment were more suitable for ethane than for methane hydrates, the values reported above confirm the contemporary inclusion of both species within the hydrate lattice. These results could suggest the predominant production of sI hydrates. However, according to the ratio between large and small cavities in sI (3:1), the highest capture rate of gas was expected in tests performed with the first mixture, where ethane was the most abundant species (75 vol%). Conversely, the most abundant production occurred in the last group of experiments, with an initial CH4/C2H6 content equal to 75/25 vol%. These latter results suggest the possible formation of different structures (sI and sII) as a function of the mixture composition, in agreement with Subramanian and colleagues [70], who experimentally proved the transition from sI to sII over the CH4 composition range of 72.2–75 mol%. This suggests the approximately complete consumption of ethane for the production of mixed hydrates and, due to the relatively high partial pressure, the consumption of some of the methane for the formation of mono-species hydrates.

These results encourage the usage of ethane for improving the efficiency of methane in solid forms: the addition of one-fourth of this “support gas” allows the cages to capture methane under milder thermodynamic conditions and without using chemical promoters. The results achieved in this study agree with the existing literature, where the presence of ethane molecules in gaseous binary mixtures containing methane was proven to be responsible for delayed the melting of cages and enhanced self-preservation effects [80].

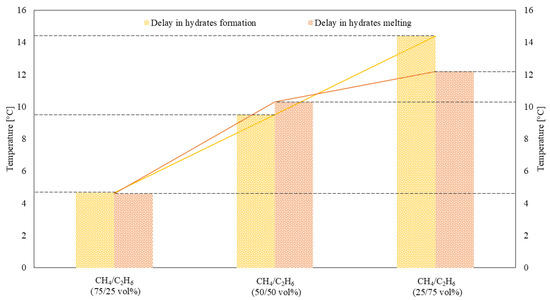

The effects of adding ethane into mixtures with methane at different concentrations on key parameters of the hydrate formation/dissociation processes, such as induction period and self-preservation from melting, are described in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Thermodynamic quantification of the induction period and preservation from melting as a function of the initial CH4/C2H6 composition of the gaseous mixture.

As previously explained, the induction period was only thermodynamically defined, since this study is not focused on the time evolution or the kinetics of the process. Therefore, this expression was used to define the delay, expressed as a function of temperature, between the thermodynamic configuration where the massive formation of hydrates would have begun and when it effectively took place. Such a delay was found to increase with the concentration of ethane in the gaseous mixture. In detail, it was equal to +4.67 °C for CH4/C2H6 (75/25) vol%, +9.51 °C for CH4/C2H6 (50/50) vol%, and +14.40 °C for CH4/C2H6 (25/75) vol%.

Similarly, mixed hydrates showed a certain tendency to preserve their solid structure despite the local increase in temperature, proportional to ethane content in the gaseous mixture. Considering the three different mixtures described above, the temperature delay before observing hydrate dissociation was equal to +4.59 °C, +10.30 °C, and +12.20 °C, respectively.

It should be highlighted that, independently of these two similar tendencies, both formation and dissociation occurred within the thermodynamic region between the phase boundary equilibrium curves of pure methane and pure ethane hydrates. However, the two phenomena numerically described and shown in Figure 6 behaved in an opposite to each other. As expected, the increasing concentration of C2H6 in the mixture shifted the melting conditions towards the phase boundary conditions of pure ethane hydrates. Conversely, the delay in hydrate formation was unexpectedly directly proportional to ethane concentration. This means that the addition of ethane to the mixture gradually shifted the massive formation step towards the phase equilibrium curve of pure methane hydrates. This latter property of the present system is worthy of further investigation in future studies. Moreover, during the induction period, the formation of hydrates is possible. This term is commonly used to define the time elapsed until the production of hydrates becomes clearly visible [74,75], but the production of hydrates during it is feasible. Even though this research is focused on the process’ thermodynamic evolution, these results highlight that the addition of ethane to the system, in mixtures with methane, slows down the process’ kinetics. Conversely, from a thermodynamic point of view, the upper barrier of pure methane hydrate equilibrium was never passed.

These results confirm that CO2/CH4 replacement processes, in the presence of support species with a molecular diameter larger than carbon dioxide, need to be further investigated. When CO2 is mixed with smaller molecules capable of forming hydrates, such as N2, the formation conditions always fall within the equilibrium curves of the two pure species, and the positioning of the phase equilibrium curve, with respect to those belonging to the pure species, is a function of the mixture composition [81]. While the delayed dissociation is an opportunity for a more stable hydrate lattice after replacement (higher efficiency carbon dioxide storage), a longer induction period may result in a relevant reduction in methane recovery even if, considering the species considered in this study, it should lead to higher cage occupancy, thus making the process faster.

Apart from this, the addition of ethane undoubtedly improves the stability of crystalline structures. The presence of only 25 vol% ethane thermodynamically delayed hydrated dissociation by about 4.59 °C. When pure ethane was present within water cages, the melting of hydrates occurred at even higher temperatures that when a mixture containing 50–75 vol% methane was used.

Based on the data discussed above, it can be concluded that ethane represents a viable option for the solid storage of energy gases in the form of hydrates. This support gas ensures greater stability of the formed crystalline lattice and makes the energy requirements lower, even in the absence of chemical promoting additives. Increased stability also means a safer process, both during the storage and transportation steps. Finally, its separation from methane before its end use would not incur excessive requirements or costs.

5. Conclusions

Natural gas mixtures often contain minor concentrations of light hydrocarbons with a molecular weight and size greater than those of methane, such as ethane, propane, and butane. Their role during the formation and dissociation of sI hydrates needs to be experimentally investigated, since they could have a significant effect during CO2/CH4 replacement processes or during energy gas storage processes.

The present research focused on the production and dissociation of hydrates hosting methane mixed with different concentrations of ethane. Three different mixtures were considered, namely (25/75), (50/50), and (75/25) vol%. While the production and melting of hydrates with methane and carbon dioxide have been explored in the literature, experimental data regarding mixtures containing small-chain hydrocarbons (C2-C3) is substantially more limited. Nevertheless, these species are often present, even if at relatively low concentrations, in natural gas mixtures (including those contained in natural hydrate reservoirs), thus playing a role in defining the phase equilibrium conditions of these systems. Moreover, due to their molecular size, these compounds have the ability to strongly affect the key properties of hydrates, such as the cage filling ratio, the overall cage occupancy rate, and the self-preservation effect. For these reasons, further experimental efforts are widely encouraged in this field. Our experiments were carried out in a small-scale unstirred reactor filled with porous silica sand to reproduce classical offshore sediment conditions and to extend the production of hydrates to the entire volume of the reactor.

By themselves, pure methane and pure ethane are capable of forming sI hydrates, while in the mixed version, ethane molecules can occupy the large cavities, thus improving the stability of the whole lattice, while methane molecules preferentially fit into the small cavities.

In terms of the overall quantity of gas captured, relevant differences between the various mixtures tested were not observed: the number of moles of hydrates formed varied from 0.195 to 0.255 mol. However, it should be noted that the highest capture rate was obtained with the lowest initial concentration of ethane (25 vol%).

Both an induction period and improved hydrate stability (the latter described as improved capability for self-preservation under conditions different from the reached equilibrium) were thermodynamically described, taking the form of a temperature delay from which the formation and dissociation processes should have begun.

The induction period was relevant in the presence of ethane and increased with its concentration, from 4.67 to 14.40 °C. The same was observed for hydrate dissociation, which occurred with a delay ranging from 4.59 to 12.20 °C, depending on the concentration of ethane.

Both for CO2/CH4 replacement and for energy gas storage, this delayed formation could represent a limiting factor which needs to be further investigated. Conversely, the higher stability highlighted with these experiments makes this species a viable option to form hydrates under milder thermodynamic conditions (with lower energy requirements), improve their stability, and make both their formation and transportation (in the case of energy gas storage) safer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.G.; methodology, A.M.G.; validation, D.P., F.R. and G.G.; formal analysis, A.M.G.; investigation, A.M.G. and D.P.; resources, F.R. and G.G.; data curation, A.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.G.; supervision, D.P., F.R. and G.G.; project administration, F.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support derived by the PNRR project entitled “High Efficiency Hydrogen Storage (HEHS)”, ID: RSH2B_000052 (to Prof. Giovanni Gigliotti and Prof. Federico Rossi). The authors also acknowledge the technical and material contribution of AiZoOn Technology Consulting and Nippon Gases Industrial Srl.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sloan, E.D.; Koh, C.A. Clathrate Hydrates of Natural Gases, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Yin, S.; He, G.; Li, J.; Wu, Q. Research progress of the kinetics on natural gas hydrate replacement by CO2 containing mixed gas: A review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 108, 104837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.G.; Zhang, W.; Yan, K.F.; Cai, J.; Chen, Z.Y.; Li, X.S. Research on micro mechanism and influence of hydrate-based methane-carbon dioxide replacement for realizing simultaneous clean energy exploitation and carbon emission reduction. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 248, 117266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Teng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Bao, W.; Han, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, H. Review on the synergistic effect between metal-organic frameworks and gas hydrates for CH4 storage and CO2 separation applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M.; Rossi, F. Review on the usage of small-chain hydrocarbons (C2-C4) as aid gases for improving the efficiency of hydrate-based technologies. Energies 2023, 16, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, F. Geochemical characteristics of borehole cores and their indicative significance for gas hydrates in the permafrost area, Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Appl. Geochem. 2025, 178, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Xu, C.G.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, X.K.; Li, G.; Wang, Y. Investigation into gas production from natural gas hydrate: A review. Appl. Energy 2016, 172, 286–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Z.; You, C. Combined styles of depressurization and electrical heating for methane hydrate production. Appl. Energy 2021, 282, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, K.; Yi, W.; Li, X.S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.Z. Influence of heat conduction and heat convection on hydrate dissociation by depressurization in a pilot-scale hydrate simulator. Appl. Energy 2019, 251, 113405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.C.; Prasad, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Sangway, J.S. Energy recovery from simulated clayey gas hydrate reservoir using depressurization by constant rate gas release, thermal stimulation and their combination. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, J.C.; Li, X.S.; Zhang, Y. Experimental investigation of optimization of well spacing for gas recovery from methane hydrate reservoir in sandy sediment by heat stimulation. Appl. Energy 2017, 207, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Liu, H.; Lin, Q.; Wu, M.; Sun, L. Heat and mass transfer analysis during the process of methane hydrate dissociation by thermal stimulation. Fuel 2024, 362, 130790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, A.P.; Tulegenov, T.B.; Stoporev, A.S.; Novikov, A.A.; Gushchin, P.A.; Vinokurov, V.A. Does dimethyl sulfoxide inhibit or promote methane hydrate nucleation and growth? J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 437, 128393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, A.P.; Mendgaziev, R.I.; Stoporev, A.S.; Istomin, V.A.; Sergeeva, D.V.; Ogienko, A.G.; Vinokurov, V.A. The pursuit of a more powerful thermodynamic hydrate inhibitor than methanol. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a case study. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 423, 130227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M.; Rossi, F. Re-definition of the region suitable for CO2/CH4 replacement into hydrates as a function of the thermodynamic difference between CO2 hydrate formation and dissociation. Proc. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 169, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M.; Presciutti, A.; Rossi, F. Kinetic considerations and formation rate for carbon dioxide hydrate, formed in presence of a natural silica-based porous medium: How initial thermodynamic conditions may modify the process kinetic. Thermochim. Acta 2021, 705, 179039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, K.; Wu, S.; Chen, Q.; Bian, J. Hydrate-based CO2 sequestration technology: Feasibility mechanisms, influencing factors, and applications. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 219, 111121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminu, M.D.; Nabavi, S.; Rochelle, C.; Manovìc, V. A review of developments in carbon dioxide storage. Appl. Energy 2017, 208, 1389–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cao, Q.; Xu, D.; Luo, S.; Guo, R. Improved methane storage capacity on methane hydrate promoted by vesicles from carboxylate surfactants and quaternary ammonium. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 93, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kwon, H.T.; Choi, K.H.; Lim, W.; Cho, J.H.; Tak, K.; Moon, L. LNG: An eco-friendly cryogenic fuel for sustainable development. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 4264–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veluswamy, H.P.; Wong, A.J.H.; Babu, P.; Kumar, R.; Kulprathipanja, S.; Rangsunvigit, P.; Linga, P. Rapid methane hydrate formation to develop a cost effective large scale energy storage system. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 290, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Guo, G.; Liu, G.Q.; Luo, S.J.; Guo, R.B. Effects of surfactants micelles and surfactant-coated nanosphere on methane hydrate growth pattern. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 144, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyadin, Y.A.; Larionov, E.G.; Manakiv, A.Y.; Zhurko, F.V.; Aladko, E.Y.; Mikina, T.V.; Komarov, V.Y. Clathrate hydrates hydrogen and neon. Mendeleev Commun. 1999, 9, 209–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, G.S.; Stegailov, V.V. Toward determination of the new hydrogen hydrate clathrate structures. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 3560–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, L.; Liang, D.; Li, D. Phase equilibria and dissociation enthalpies of hydrogen semi-clathrate hydrate with tetrabutyl ammonium nitrate. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2021, 57, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Sugahara, T.; Moritoki, M.; Sato, H.; Ohgaki, K. Thermodynamic stability of hydrogen + tetra-n-butyl ammonium bromide mixed gas hydrate in nonstoichiometric aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, K.; Yang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Teng, Y. Experimental and theoretical study on dissociation thermodynamics and kinetics of hydrogen-propane hydrate. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 426, 131279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bhattacharjee, G.; Kumar, R.; Linga, P. Solidified hydrogen storage (Solid-HyStore) via clathrate hydrates. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M.; Pezzolla, D.; Rossi, F.; Gigliotti, G. Thermodynamic description of CO2 hydrates production in aqueous systems containing NH4Cl; evaluation of NH4+ removal from water via spectrophotometric analysis. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 281, 119137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamoddin, M.; Varaminian, F. Water desalination using R141b gas hydrate formation. Desalination Water Treat. 2014, 52, 2450–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam Park, K.; Hong, S.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Kang, K.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Ha, M.G.; Lee, J.D. A new apparatus for seawater desalination by gas hydrate process and removal characteristics of dissolved minerals (Na+, Mg2+, Ca2+, K+, B3+). Desalination 2011, 274, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikward, N.; Nakka, R.; Khavala, V.; Bhadani, A.; Mamane, H.; Kumar, R. Gas hydrate-based process for desalination of heavy metal ions from an aqueous solution: Kinetics and rate of recovery. ACS ES&T Water 2021, 1, 134–144. [Google Scholar]

- Karamoddin, M.; Varaminian, F. Water purification by freezing and gas hydrate process, and removal of dissolved minerals (Na+, K+, Mg2+, Ca2+). Desalination 2022, 537, 115855. [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri, S.M.; Kolliopoulos, G. Hydrate based desalination for sustainable water treatment: A review. Desalination 2022, 5, 115855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.F.; Trombin, V.G.; Marques, V.N.; Martinez, L.F. Global orange juice market: A 16-year summary and opportunities for creating value. Trop. Plant. Pathol. 2020, 45, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, A.; Mushtaq, M.; Islam, T. Fruit juice concentrates. Fruit Juices 2018, 5, 217–240. [Google Scholar]

- Claben, T.; Seidl, P.; Loekman, S.; Gatternig, B.; Rauch, C.; Delgado, A. Review on the food technological potentials for gas hydrate technology. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 29, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Hitzmann, B.; Zettel, V. A future road map for carbon dioxide (CO2) gas hydrate as an emerging technology in food research. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2021, 14, 1758–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Xia, X.; Wang, F.; Wu, X.; Cheng, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y. Clathrate hydrate for phase change cold storage: Simulation advances and potential applications. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kumar, N.; Hirschey, J.; Akamo, D.O.; Li, K.; Tugba, T.; Goswami, M.; Orlando, R.; LaClair, T.J.; Graham, S.; et al. Stable salt hydrate-based thermal energy storage materials. Compos. B Eng. 2022, 233, 109621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Sun, Z. Synthesis and thermal properties of n-tetradecane phase change microcapsules for cold storage technology. J. Energy Storage 2020, 117, 104959. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.; Wang, F.; Tian, Y.; Wu, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, L.; Yang, P.; Zhao, J. Review and prospects of hydrate cold storage technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, M.; Wang, T.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y. An in-situ MRI method for quantifying temperature changes during crystal hydrate growth in porous medium. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 31, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanadhan, S.K.; Singh, A.; Veluswamy, H.P. Hydrate-based gas separation (HBGS) technology review: Status, challenges and way forward. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 131, 205465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Qian, Y.C.; Liu, Z.Q.; Xu, T.Z.; Sun, Q.; Liu, A.X.; Yang, L.; Gong, J.; Guo, X. The hydrate-based separation of hydrogen and ethylene from fluid catalytic cracking dry gas in presence of n-octyl-ß-d-glucopyranoside. Int. J. Hydrogn Energy 2022, 47, 31350–31369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.; Daraboina, N. A systematic review of recent advances in hydrate technology for precombustion carbon capture. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.; Lee, J.; Seo, Y. Separation efficiency and equilibrium recovery ratio of SF6 in hydrate-based greenhouse gas separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Zhang, T.H.; Xu, Z.B.; Wu, Y.W.; Sun, C.Y.; Chen, G.J. Study on the gas composition of hydrate phase and untreated liquid phase for hydrate-based gas separation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, A.; Hayashi, S.; Tajima, H.; Kiyono, F.; Yanagisawa, Y.; Yamasaki, A. Gas separation using tetrahydrofuran clathrate hydrate crystals based in the molecular sieving effect. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 139, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linga, P.; Kumar, R.; Englezos, P. Gas hydrate formation from hydrogen/carbon dioxide and nitrogen/carbon dioxide gas mixtures. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2007, 62, 4268–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gambelli, A.M.; Rossi, F. Experimental study on the effect of SDS and micron copper particles mixture on carbon dioxide hydrates formation. Energies 2022, 15, 6540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Song, W.; Chen, B.; Song, Y. A method of cycling icing and melting for stable and rapid formation of hydrate: Novel strategy of hydrate-based energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 98, 112839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Seo, D.; Lee, Y.; Moon, S.; Park, Y. Promoting thermodynamic stability of hydrogen hydrates with gas-phase modulators for energy-efficient blue hydrogen storage. Fuel 2024, 372, 132196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahant, B.; Kushwaha, O.S.; Kumar, R. Thermodynamic phase equilibria study of Hythane (methane+hydrogen) gas hydrates for enhanced energy storage applications. Fluid Phase Equilibr. 2024, 582, 114089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Fan, Z.; Negahban, S. Structural and dynamic analyses of CH4-C2H6-CO2 hydrates using thermodynamic modeling and molecular dynamic simulation. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2022, 169, 106749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Li, X.; Negahban, S. Molecular-level insights into the structure stability of CH4-C2H6 hydrates. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 247, 117039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M.; Gigliotti, G.; Rossi, F. Production of CH4/C3H8 (85/15 vol%) hydrate in a lab-scale unstirred reactor: Quantification of the promoting effect due to the addition of propane to the gas mixture. Energies 2024, 17, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makogon, Y.F. Natural gas hydrates—A promising source of energy. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2010, 2, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makogon, Y.F.; Holditch, S.A.; Makogon, T.Y. Natural gas-hydrates—A potential energy source for the 21 Century. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2007, 56, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M.; Filipponi, M.; Nicolini, A.; Rossi, F. Natural gas hydrate: Effect of sodium chloride on the CO2 replacement process. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConference SGEM 2019, 19, 333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Gambelli, A.M. Variations in terms of CO2 capture and CH4 recovery during replacement processes in gas hydrate reservoirs, associated to the “memory effect”. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 360, 132154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M.; Rossi, F.; Gigliotti, G. Hydrates production with binary CO2/C3H8 gaseous mixtures (90/10, 85/15, 80/20 vol%) in batch and unstirred conditions: The role of propane on the process thermodynamics. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 298, 120441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M. Hydrates production with gaseous CO2/C3H8 and CH4/C3H8 (90/10 vol%) mixtures and definition of the role of propane during CO2/CH4 replacement processes. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 88, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavoh, C.B.; Partoon, B.; Lal, B.; Keong, L.K. Methane hydrate-liquid-vapor-equilibrium phase condition measurements in the presence of natural amino acids. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 37, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottger, A.; Kamps, A.P.S.; Maurer, G. An experimental investigation on the phase equilibrium of the binary system (methane + water) at low temperatures: Solubility of methane in water and three-phase (vapour + liquid + hydrate) equilibrium. Fluid Phase Equilibr. 2016, 407, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, H.D.; Ohmura, R. Phase equilibrium condition measurements in methane clathrate hydrate forming system from 197.3 K to 238.7 K. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2016, 102, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, Z.; Khan, M.S.; Lal, B. Thermodynamic modelling on methane hydrate equilibrium condition in the presence of electrolyte inhibitor. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 19, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, R.; Uchida, T.; Takeya, S.; Nagao, J.; Minagawa, H.; Ebinuma, T.; Narita, H. Clathrate hydrate formation in (methane + water + methylcyclohexanone) systems: The first phase equilibrium data. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2003, 35, 2045–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, E.M.; Edmond, B.; Moorwood, R.A.S.; Szcepanski, R. Hydrate structure stability in simple and mixed hydrates. Fluid Phase Equilibr. 1996, 117, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Kini, R.A.; Dec, S.F.; Sloan, E.D. Evidence of structure II hydrate formation from methane + ethane mixtures. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2000, 55, 1981–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Zhang, G.B.; Carroll, J.J.; Li, S.L.; Jiang, S.H.; Guo, W. Experimental investigation into gas recovery from CH4-C2H6-C3H8 hydrates by CO2 replacement. Appl. Energy 2018, 229, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundramoorthy, J.D.; Hammonds, P.; Lal, B.; Philips, G. Gas hydrate equilibrium measurement and observation of gas hydrate dissociation with/without a KHI. Procedia Eng. 2016, 148, 870–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambelli, A.M. Deviation of phase boundary conditions for hydrates of small-chain hydrocarbons (CH4, C2H6 and C3H8) when formed within porous sediments. Energies 2024, 17, 5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Dong, H.; Sun, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, L. Effect of a weak electric field on THF hydrate formation: Induction time and morphology. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 194, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Zendehboudi, S.; Abdi, M.A. Deterministic tools to estimate induction time for methane hydrate formation in the presence of Luvicap 55W solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 348, 118374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, X.; Zheng, R.; Chen, Y.; Hou, J. Experimental investigation on dissociation driving force of methane hydrate in porous media. Fuel 2015, 160, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeya, S.; Kida, M.; Minami, H.; Sakagami, H.; Hackikubo, A.; Takahashi, N.; Shoji, H.; Soloviev, V.; Wallmann, K.; Biebow, N.; et al. Structure and thermal expansion of natural gas clathrate hydrates. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2006, 61, 2670–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aregba, A.G. Gas hydrate—Properties, formation and benefits. Open J. Yangtze Oil Gas 2017, 2, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.C.; Castaldi, M.J.; Zhou, Y. Large scale reactor details and results for the formation and decomposition of methane hydrates via thermal stimulation dissociation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 94, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kida, M.; Takeya, S.; Ohmura, R.; Nagao, J.; Hori, A. Dissociation behavior of methane-ethane mixed-gas hydrates. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 656–662. [Google Scholar]

- Gambelli, A.M. Methane replacement into hydrate reservoirs with carbon dioxide: Main limiting factors and influence of the gaseous phase composition, over hydrates, on the process. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 478, 147247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).