How to Detect Low-Energy Isomers of Fullerenes Using Clar Covers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results

- 1.

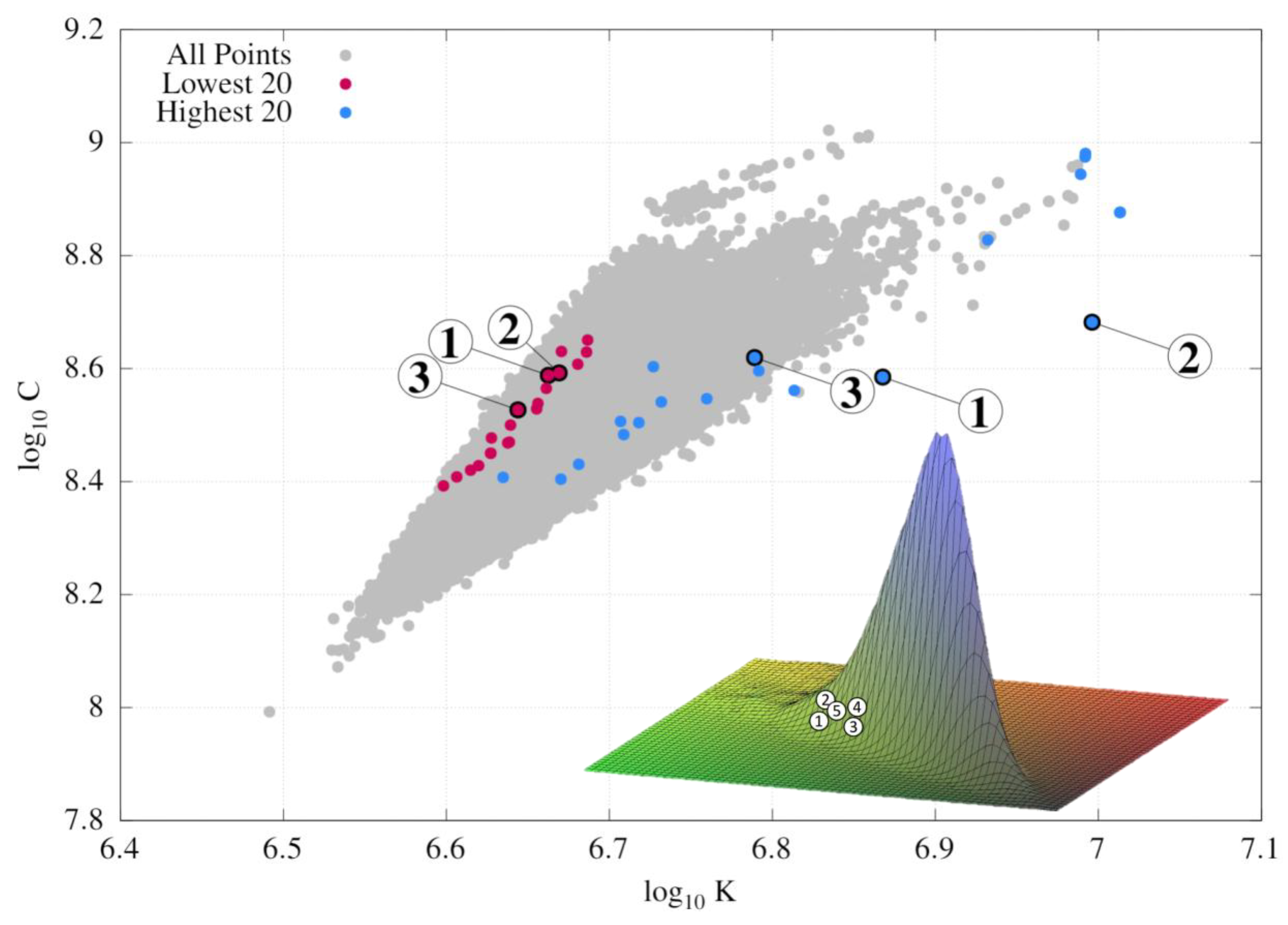

- The lowest-energy structures are indeed distributed close to the left edge of the wedge, in contrast to the highest-energy structures, which are closer to the right edge.

- 2.

- These maximal and minimal points are not located directly on the edge, but only in its vicinity, showing that the C vs. K distribution can be treated only as an approximate descriptor of the thermodynamic stability of fullerene isomers.

- 3.

- The 2D visualization of the wedge in Figure 4 lacks information about the distribution density, leading to an incorrect impression that the low-energy structures are located in the midst of the distribution, rather than on its edge. In reality, both edges of the distribution are flat and account for a small number of points; the majority are located along the bisector of the wedge, with the right edge growing more steeply than the left edge. This behavior is clearest from the 3D visualization of the distribution shown as an inset in Figure 4, where the locations of the five lowest-energy isomers are depicted by numbers. This 3D visualization of the distribution was created by representing each isomer as a 2D Gaussian peak of unit volume located at ; the whole distribution is a union of such peaks.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fowler, P.W.; Manolopoulos, D.E. An Atlas of Fullerenes; Dover: Mineola, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger, P.; Wirz, L.; Avery, J. Program Fullerene: A software package for constructing and analyzing structures of regular fullerenes. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 1508–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwerdtfeger, P.; Wirz, L.N.; Avery, J. The topology of fullerenes. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2015, 5, 96–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, P.; Gu, X. Structural Characteristics of Fullerenes. In Handbook of Fullerene Science and Technology; Lu, X., Akasaka, T., Slanina, Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 81–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolsaet, K.; D’hondt, S.; Goedgebeur, J. House of Graphs 2.0: A database of interesting graphs and more. Discr. Appl. Math. 2023, 325, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Nagase, S. Chapter 32-Computational chemistry of isomeric fullerenes and endofullerenes. In Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry; Dykstra, C.E., Frenking, G., Kim, K.S., Scuseria, G.E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 891–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioslowski, J. Note on the asymptotic isomer count of large fullerenes. J. Math. Chem. 2014, 52, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukhovich, A.D. On the growth rate of the number of fullerenes. Russ. Math. Surv. 2018, 73, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sure, R.; Hansen, A.; Schwerdtfeger, P.; Grimme, S. Comprehensive theoretical study of all 1812 C60 isomers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 14296–14305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, N.; Gao, Y.; Yoo, S.; An, W.; Zeng, X.C. Search for Lowest-Energy Fullerenes: C98 to C110. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 7672–7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, N.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, X.C. Search for Lowest-Energy Fullerenes 2: C38 to C80 and C112 to C120. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 17671–17677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. On the Structure and Relative Stability of C50 Fullerenes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 5267–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calaminici, P.; Geudtner, G.; Köster, A.M. First-Principle Calculations of Large Fullerenes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manolopoulos, D.E.; Fowler, P.W.; Taylor, R.; Kroto, H.W.; Walton, D.R.M. An end to the search for the ground state of C84? J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1992, 88, 3117–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolopoulos, D.E.; Fowler, P.W. Molecular graphs, point groups, and fullerenes. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 7603–7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.L.; Xu, C.H.; Wang, C.Z.; Chan, C.T.; Ho, K.M. Systematic study of structures and stabilities of fullerenes. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 46, 7333–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.L.; Wang, C.Z.; Ho, K.M.; Xu, C.H.; Chan, C.T. The geometry of small fullerene cages: C20 to C70. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 97, 5007–5011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, R.L.; Scuseria, G.E. Theoretical Study of C90 and C96 Fullerene Isomers. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 4212–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuseria, G.E. Ab Initio Calculations of Fullerenes. Science 1996, 271, 942–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroto, H.W. The stability of the fullerenes Cn, with n = 24, 28, 32, 36, 50, 60 and 70. Nature 1987, 329, 529–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioslowski, J.; Rao, N.; Moncrieff, D. Standard Enthalpies of Formation of Fullerenes and Their Dependence on Structural Motifs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8265–8270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Caporossi, G.; Hansen, P. Distance Matrices, Wiener Indices, and Related Invariants of Fullerenes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 6232–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcamí, M.; Sánchez, G.; Díaz-Tendero, S.; Wang, Y.; Martín, F. Structural patterns in fullerenes showing adjacent pentagons: C20 to C72. J Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2007, 7, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.H.; Wu, R.; Tian, J.L.; Clarke, J.; Gibson, C.; Fowler, P.W. From C58 to C62 and back: Stability, structural similarity, and ring current. J. Comput. Chem. 2017, 38, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Z. Curved Pi-Conjugation, Aromaticity, and the Related Chemistry of Small Fullerenes (<C60) and Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 3643–3696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wiener, H. Structural Determination of Paraffin Boiling Points. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaban, A.T.; Millis, D.; Ivanciuc, O.; Basak, S. Reverse Wiener indices. Croat. Chem. Acta 2000, 73, 923–941. [Google Scholar]

- Balaban, A.T. Topological indices based on topological distances in molecular graphs. Pure Appl. Chem. 1983, 55, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, A.T.; Liu, X.; Klein, D.J.; Babic, D.; Schmalz, T.G.; Seitz, W.A.; Randić, M. Graph Invariants for Fullerenes. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1995, 35, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Taeri, B. Szeged index of TUC4C8(S) nanotubes. Eur. J. Combin. 2009, 30, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Balasubramanian, K. Spectral moments of fullerene cages. Mol. Phys. 1993, 79, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, E. Characterization of 3D molecular structure. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 319, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, S.; Friedrich, T. A geometric constraint, the head-to-tail exclusion rule, may be the basis for the isolated-pentagon rule in fullerenes with more than 60 vertices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 19142–19147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Klein, D.J.; Schmalz, T.G. Preferable Fullerenes and Clar-Sextet Cages. Fuller. Sci. Technol. 1994, 2, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Heine, T.; Zerbetto, F. Competition between Even and Odd Fullerenes: C118, C119, and C120. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 9625–9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Tendero, S.; Martín, F.; Alcamí, M. Structure and Electronic Properties of Fullerenes : Is an Exception to the Pentagon Adjacency Penalty Rule? Chem. Phys. Chem. 2005, 6, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.W.; Nikolić, S.; De Los Reyes, R.; Myrvold, W. Distributed curvature and stability of fullerenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 23257–23264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achiba, Y.; Fowler, P.W.; Mitchell, D.; Zerbetto, F. Structural Predictions for the C116 Molecule. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 6835–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Lee, S.L.; Yu, C.H. Computations in Treating Fullerenes and Carbon Aggregates. In Reviews in Computational Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Zhao, X.; Uhlík, F.; Lee, S.L.; Adamowicz, L. Computing enthalpy–entropy interplay for isomeric fullerenes. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 2004, 99, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, Z.; Uhlík, F.; Adamowicz, L. Theoretical Predictions of Fullerene Stabilities. In Proceedings of the Handbook of Fullerene Science and Technology; Lu, X., Akasaka, T., Slanina, Z., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 111–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.A. Structures and Stability of Fullerenes, Metallofullerenes, and Their Derivatives. In Proceedings of the Handbook of Computational Chemistry; Leszczynski, J., Kaczmarek-Kedziera, A., Puzyn, T., Papadopoulos, M.G., Reis, H., Shukla, M.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1031–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Liu, S.; Rong, C.; Zhong, A.; Liu, S. Toward Understanding the Isomeric Stability of Fullerenes with Density Functional Theory and the Information-Theoretic Approach. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 17986–17990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Jin, J.; Liu, M. Mapping structure-property relationships in fullerene systems: A computational study from C20 to C60. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabirov, D.S.; Ori, O.; László, I. Isomers of the C84 fullerene: A theoretical consideration within energetic, structural, and topological approaches. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2018, 26, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Jin, J.; Liu, M. Extrapolating Beyond C60: Advancing Prediction of Fullerene Isomers with FullereneNet. Digit. Discov. 2025; Accepted manuscript. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Díaz-Tendero, S.; Alcamí, M.; Martín, F. Generalized structural motif model for studying the thermodynamic stability of fullerenes: From C60 to graphene passing through giant fullerenes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 19646–19655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.; Kawashima, Y.; Dawson, W.; Katouda, M.; Nakajima, T.; Hirao, K. A Simple Model for Relative Energies of All Fullerenes Reveals the Interplay between Intrinsic Resonance and Structural Deformation Effects in Medium-Sized Fullerenes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, S.L.; Karton, A.; Chan, B.; Page, A.J. Thermochemical stabilities of giant fullerenes using density functional tight binding theory and isodesmic-type reactions. J. Comput. Chem. 2021, 42, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Jin, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Chuang, C.; Jin, B.Y.; Tománek, D. Local curvature and stability of two-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 245403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Zhao, Y.X.; Han, Y.B.; Yuan, K.; Nagase, S.; Ehara, M.; Zhao, X. Theoretical Investigation of the Key Roles in Fullerene-Formation Mechanisms: Enantiomer and Enthalpy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irle, S.; Zheng, G.; Elstner, M.; Morokuma, K. From C2 Molecules to Self-Assembled Fullerenes in Quantum Chemical Molecular Dynamics. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irle, S.; Zheng, G.; Wang, Z.; Morokuma, K. The C60 Formation Puzzle “Solved“: QM/MD Simulations Reveal the Shrinking Hot Giant Road of the Dynamic Fullerene Self-Assembly Mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 14531–14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinadayalane, T.C.; Leszczynski, J. Fundamental Structural, Electronic, and Chemical Properties of Carbon Nanostructures: Graphene, Fullerenes, Carbon Nanotubes, and Their Derivatives. In Proceedings of the Handbook of Computational Chemistry; Leszczynski, J., Kaczmarek-Kedziera, A., Puzyn, T., Papadopoulos, M.G., Reis, H., Shukla, M.K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1175–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, D.; Klein, D.; Sah, C. Symmetry of fullerenes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1993, 211, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, H.A.; Kang, J.S. ZZ polynomials for isomers of (5,6)-fullerenes Cn with n = 20–50. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witek, H.A.; Podeszwa, R. Kekulé Counts, Clar Numbers, and ZZ Polynomials for All Isomers of (5,6)-Fullerenes C52–C70. Molecules 2024, 29, 4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.P.; Witek, H.A. An algorithm and FORTRAN program for automatic computation of the Zhang-Zhang polynomial of benzenoids. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2012, 68, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.P.; Witek, H.A. Determination of Zhang-Zhang Polynomials for Various Classes of Benzenoid Systems: Non-Heuristic Approach. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2014, 72, 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Podeszwa, R.; Witek, H.A. ZZPolyCalc: An open-source code with fragment caching for determination of Zhang-Zhang polynomials of carbon nanostructures. Comp. Phys. Comm. 2024, 301, 109210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.P.; Zhang, F.J. The Clar covering polynomial of hexagonal systems I. Discret. Appl. Math. 1996, 69, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. The Clar covering polynomial of hexagonal systems with an application to chromatic polynomials. Discret. Math. 1997, 172, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, F. The Clar covering polynomial of hexagonal systems III. Discret. Math. 2000, 212, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, I.; Furtula, B.; Balaban, A.T. Algorithm for simultaneous calculations of Kekulé and Clar structure counts, and Clar number of benzenoid molecules. Polycyc. Arom. Comp. 2006, 26, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, J.; Witek, H.A. ZZ polynomials of regular m-tier benzenoid strips as extended strict order polynomials of associated posets. Part 1. Proof of equivalence. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2022, 87, 585–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, J.; Witek, H.A. ZZ polynomials of regular m-tier benzenoid strips as extended strict order polynomials of associated posets. Part 2. Guide to practical computations. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2022, 88, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, J.; Witek, H.A. ZZ polynomials of regular m-tier benzenoid strips as extended strict order polynomials of associated posets. Part 3. Compilation of results for m = 1–6. MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 2022, 88, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, M.; Porezag, D.; Jungnickel, G.; Elsner, J.; Haugk, M.; Frauenheim, T.; Suhai, S.; Seifert, G. Self-consistent-charge density-functional tight-binding method for simulations of complex materials properties. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 58, 7260–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaus, M.; Cui, Q.; Elstner, M. DFTB3: Extension of the Self-Consistent-Charge Density-Functional Tight-Binding Method (SCC-DFTB). J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011, 7, 931–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaus, M.; Goez, A.; Elstner, M. Parametrization and Benchmark of DFTB3 for Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hourahine, B.; Aradi, B.; Blum, V.; Bonafé, F.; Buccheri, A.; Camacho, C.; Cevallos, C.; Deshaye, M.Y.; Dumitricǎ, T.; Dominguez, A.; et al. DFTB+, a software package for efficient approximate density functional theory based atomistic simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 124101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witek, H.A.; Irle, S.; Zheng, G.; de Jong, W.A.; Morokuma, K. Modeling carbon nanostructures with the self-consistent charge density-functional tight-binding method: Vibrational spectra and electronic structure of C28, C60, and C70. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 125, 214706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podeszwa, R.; Witek, H.A. ZZPolyCalc: An Open-Source Code with Fragment Caching for Determination of Zhang-Zhang Polynomials of Carbon Nanostructures. 2023. Fortran 2008 Code in GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/quantumint/zzpolycalc (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Wu, Z.C.; Jelski, D.A.; George, T.F. Vibrational motions of buckminsterfullerene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1987, 137, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutte, W.T. How to Draw a Graph. Proc. London Math. Soc. 1963, s3-13, 743–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, S.J.; Fowler, P.W.; Hansen, P.; Manolopoulos, D.E.; Zheng, M. Fullerene isomers of C60. Kekulé counts versus stability. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1994, 228, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.J.; Schmalz, T.G.; Hite, G.E.; Seitz, W.A. Resonance in C60 Buckminsterfullerene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108, 1301–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ye, D.; Liu, Y. A combination of Clar number and Kekulé count as an indicator of relative stability of fullerene isomers of C60. J. Math. Chem. 2010, 48, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrgott, M.; Köksalan, M.; Kadziński, M.; Deb, K. Fifty years of multi-objective optimization and decision-making: From mathematical programming to evolutionary computation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Witek, H.A.; Podeszwa, R. How to Detect Low-Energy Isomers of Fullerenes Using Clar Covers. C 2025, 11, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040089

Witek HA, Podeszwa R. How to Detect Low-Energy Isomers of Fullerenes Using Clar Covers. C. 2025; 11(4):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040089

Chicago/Turabian StyleWitek, Henryk A., and Rafał Podeszwa. 2025. "How to Detect Low-Energy Isomers of Fullerenes Using Clar Covers" C 11, no. 4: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040089

APA StyleWitek, H. A., & Podeszwa, R. (2025). How to Detect Low-Energy Isomers of Fullerenes Using Clar Covers. C, 11(4), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11040089