3.2. Carbon Characterization

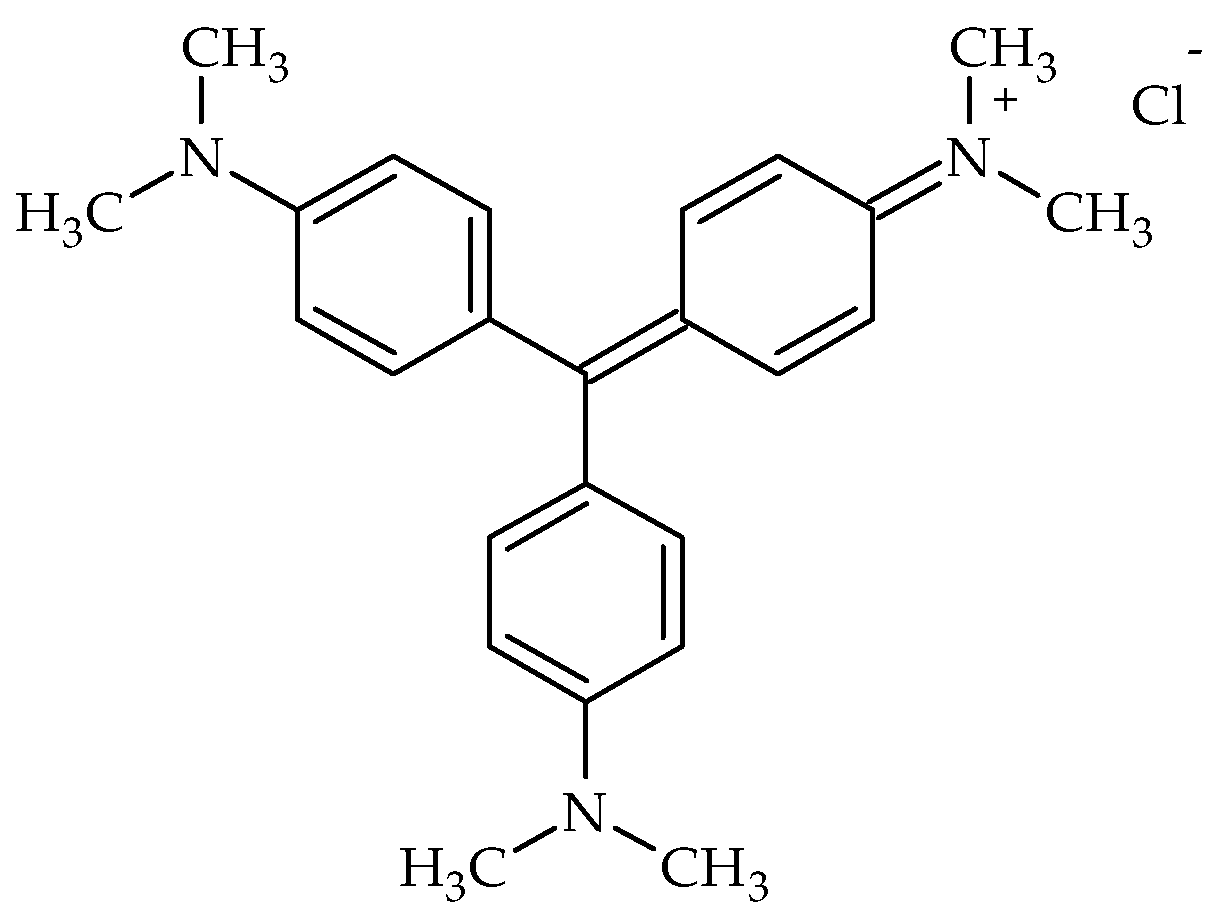

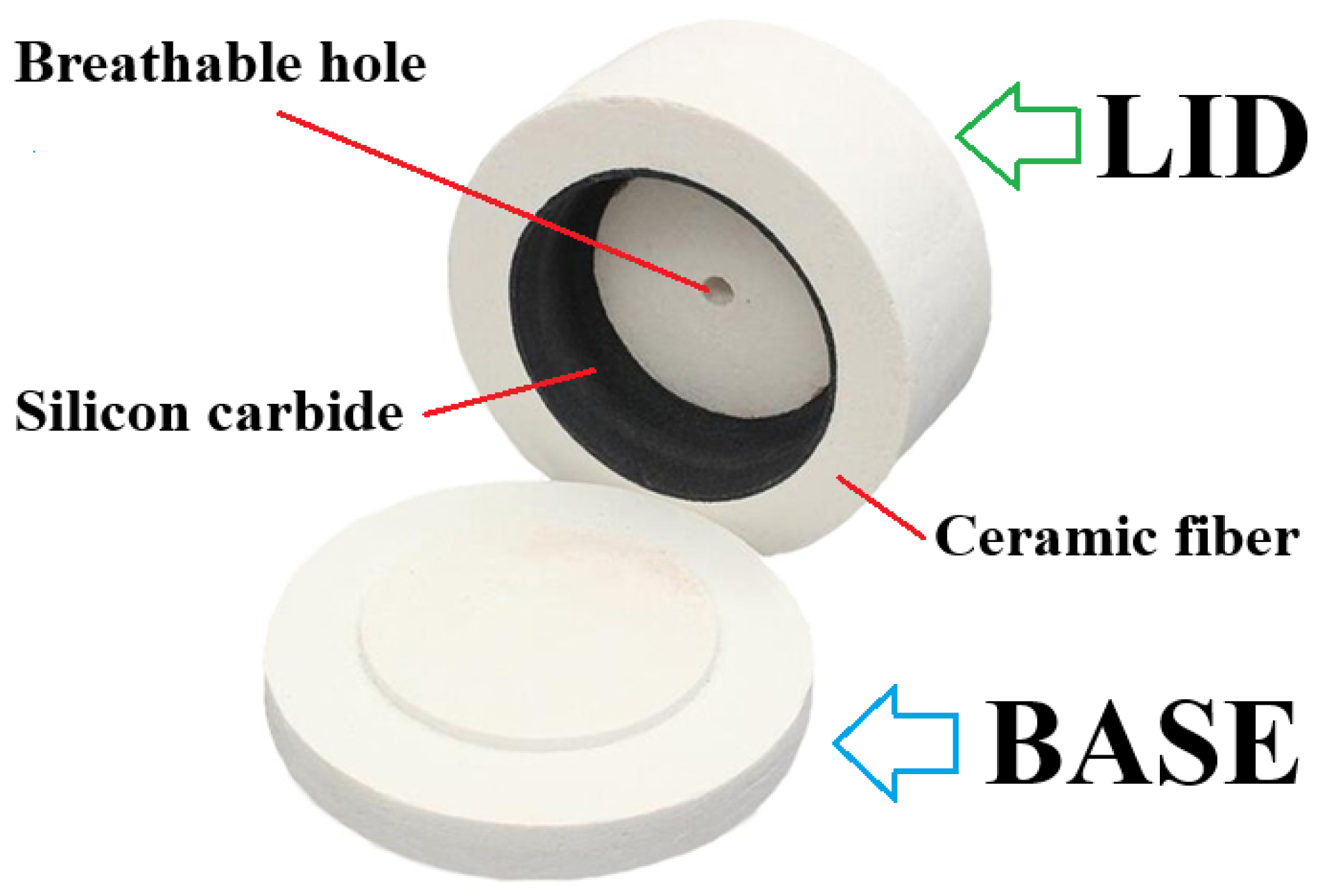

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was employed to investigate the surface morphology of the activated carbons synthesized from two different lignocellulosic precursors: peanut shells (C-PS) and spruce cones (C-SC). The microstructural analysis of the SEM micrographs (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) revealed significant morphological differences between the two carbon materials, highlighting the influence of precursor structure and composition on the physical characteristics of the resulting activated carbons. The SEM images for C-PS show clear porosity, numerous channels and layered and fibrous structures (

Figure 3).

Figure 4 shows the SEM micrographs of the C-SC activated carbon, which exhibits a markedly different morphology. The material appears to have a slightly layered structure, a heterogeneous surface with numerous micropores and cracks. The sample’s appearance may suggest a directional structure. The observed differences underscore the critical role of precursor selection in tuning the morphological properties of activated carbons.

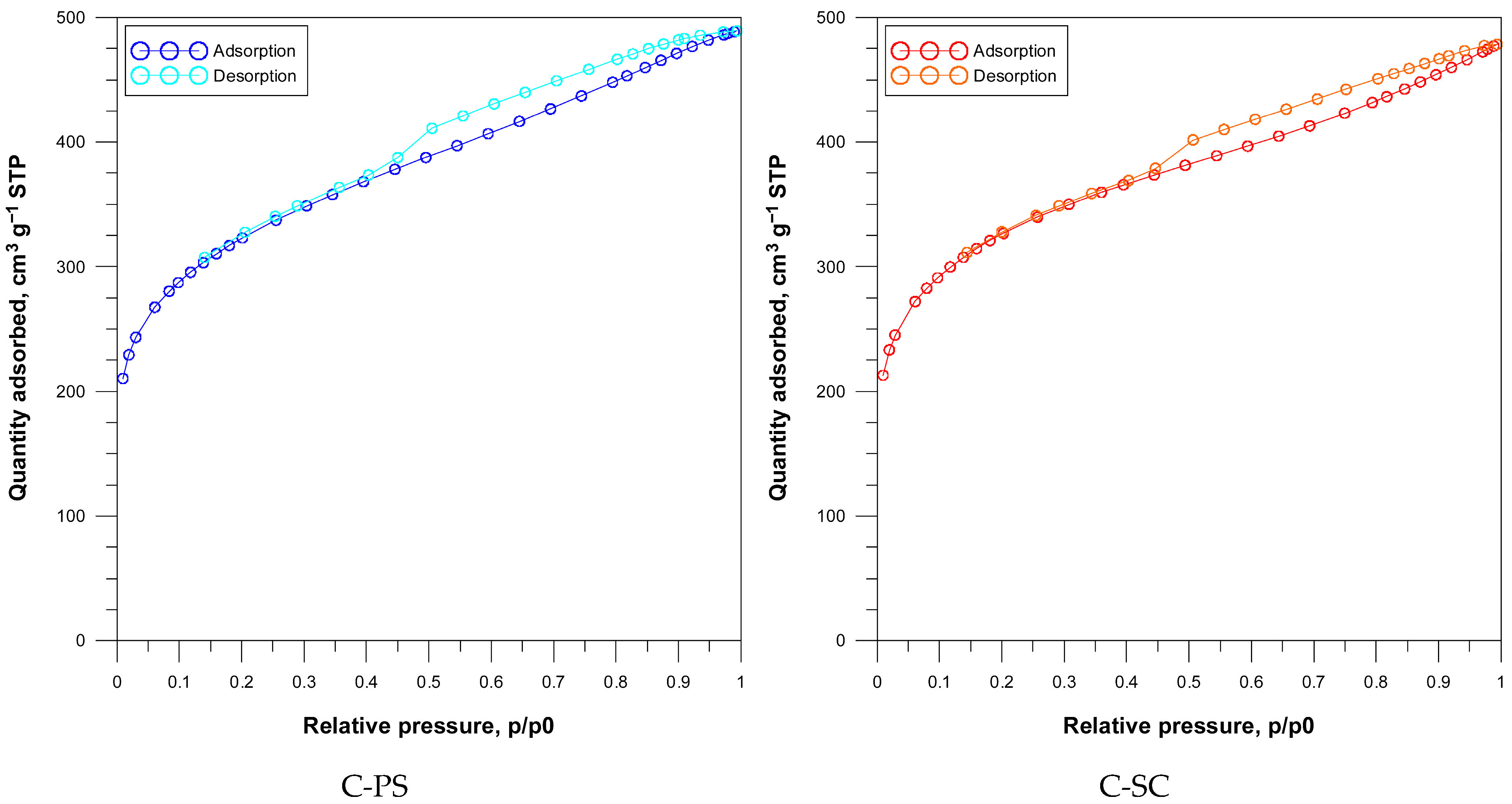

The porosity of activated carbons significantly influences their adsorption performance by affecting the surface accessibility, diffusion, and interaction of adsorbates like dyes. The carbons derived from peanut shells (C-PS) and spruce cones (C-SC), both activated with 85% phosphoric acid (1:1), were analyzed for specific surface area, pore volume, and pore structure via nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution (PSD) analysis.

According to the IUPAC recommendation, the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of both carbons were assigned to Type IV with H4-type hysteresis loops, indicating the micro-mesoporous materials [

21].

The rapid increase in nitrogen adsorption at very low p/p

0 results from adsorption in narrow mesopores, while the gradual increase in N

2 adsorption at medium and high relative pressures corresponds to monolayer and multilayer adsorption in mesopores. The phenomenon of capillary condensation occurs with the appearance of hysteresis loops. A H4-type loop is typically associated with narrow slit-like pores for aggregates of micro- and mesoporous carbons. The isotherms obtained for the tested materials are typical for carbons with a mixed micro- and mesoporous structure (

Figure 5).

According to

Table 1, the porous structure obtained from nitrogen adsorption–desorption analysis showed that both carbons possessed high specific surface areas (S

BET approx. 1145–1156 m

2 g

−1) and total pore volumes (0.74–0.76 cm

3 g

−1). The micropore surface area and volume were slightly higher for C-SC (430 m

2 g

−1 and 0.186 cm

3 g

−1) compared to C-PS (391 m

2 g

−1 and 0.169 cm

3 g

−1), contributing to better adsorption performance.

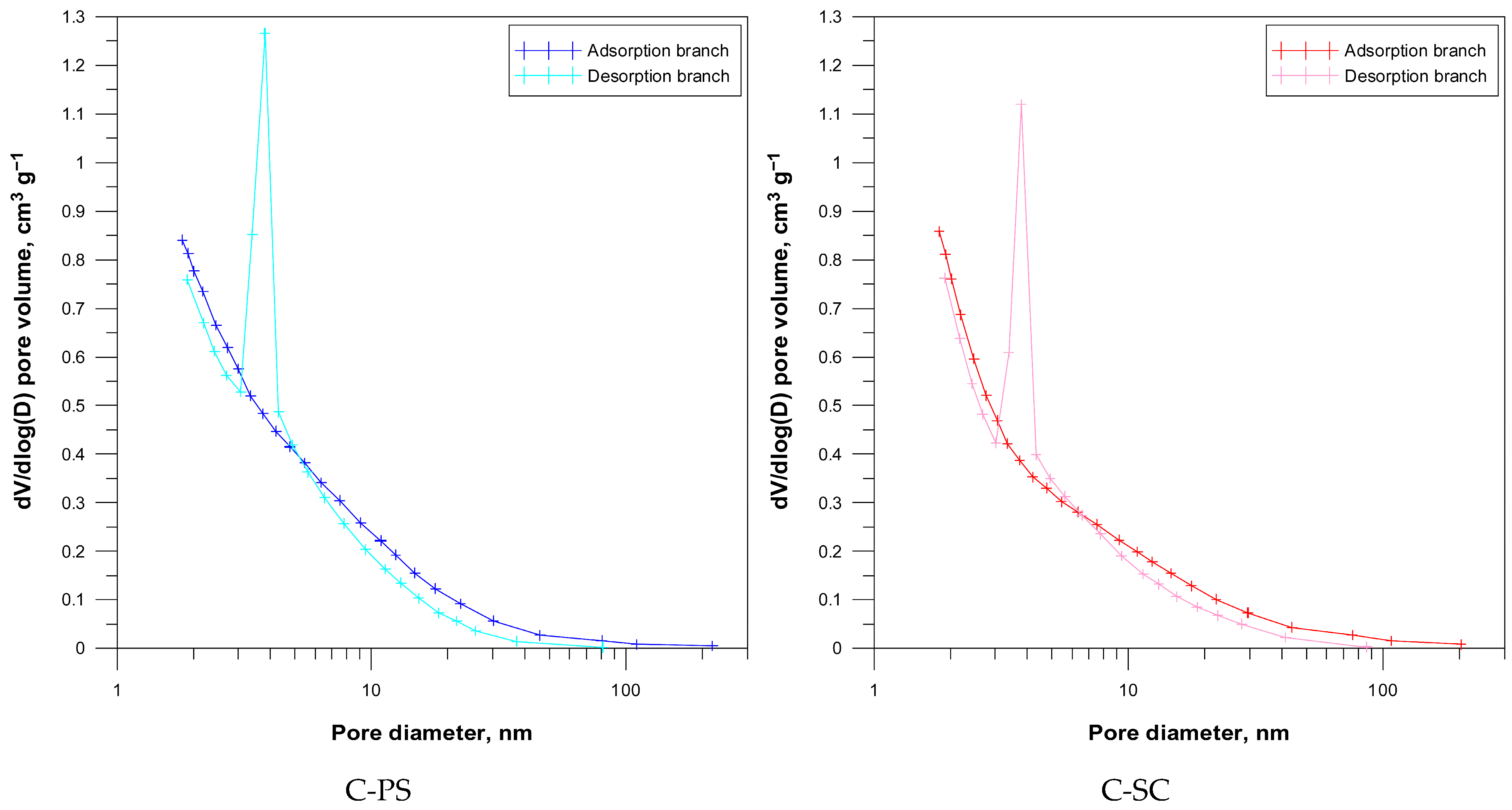

The pore size distribution obtained from nitrogen desorption represents the volume occupied by pores of different diameters. The space occupied by different pore sizes is represented as differential distribution curves dV/dlog (D) (

Figure 6). It is worth noting that the pore size distributions derived from the adsorption and desorption branches differ significantly. Some variations are also observed between the carbon types, reflecting their different pore structures.

The pore size distribution for the studied carbons reveals a well-developed porous structure ranging from 2 to 150 nm, encompassing micropores, mesopores, and macropores. The proportion of pores with diameters greater than 50 nm is almost negligible, suggesting that the carbons are primarily micro- and mesoporous.

It is well known that hysteresis loops that appear in the multilayer range of physisorption isotherms are generally associated with the filling and emptying of mesopores.

In more complex pore structures, the desorption pathway often depends on network effects and various forms of pore blocking, which occur when wide pores have access to the external surface only through narrow, ink bottle-like pore necks. Wide pores are filled and remain filled during desorption until the narrow necks empty at lower vapor pressures.

Delayed condensation occurs in open-ended pores with cylindrical geometry, meaning that in such a pore complex, the adsorption branch of the hysteresis loop is not in thermodynamic equilibrium. Therefore, if the pores are filled with a liquid-like condensate, thermodynamic equilibrium is established on the desorption branch [

21].

The desorption branch was previously preferred for analyzing mesopore size, but this practice is now considered questionable because the desorption pathway may depend on network percolation effects or pore diameter changes along single channels. On the other hand, the persistence of a metastable multilayer is likely to delay the condensation process on the adsorption branch, especially if the pores tend to adopt a slit-like shape [

22].

From desorption branch, a maximum appears at 4 nm corresponding to mesopores. In this case, applying the BJH method to the adsorption and desorption branches of the isotherm gives a completely different result. According to Groen et al., the peak observed at around 4 nm does not accurately reflect the porous properties of the material [

23].

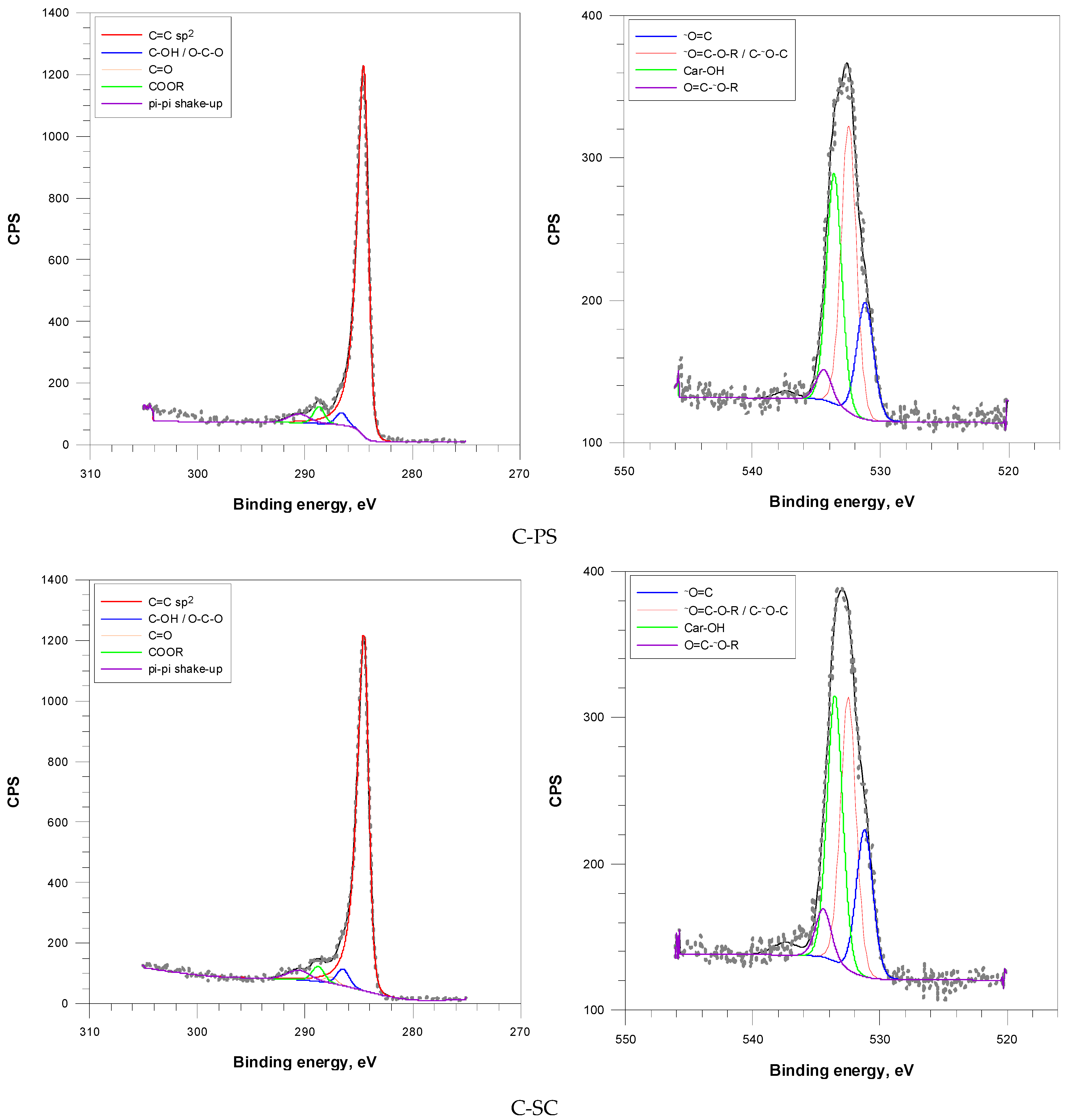

The surface composition and chemical states of elements on phosphoric-acid-activated peanut shell (C-PS) and spruce cone (C-SC) carbons were analyzed using XPS and SEM-EDS techniques (

Table 2 and

Table 3). These analyses provide critical insights into the types and distribution of oxygenated groups and the heteroatom doping (mainly phosphorus) that influence adsorption performance, particularly in dye removal.

Elemental analysis by SEM-EDS and XPS revealed that the resulting porous carbons were composed primarily of carbon and oxygen. Both techniques report similar atomic percentages for carbon, with slightly lower values in XPS, likely reflecting the increased surface contribution of oxygen and phosphorus. The minimal difference suggests a uniform carbon distribution from bulk to surface. Oxygen levels are also comparable across both techniques, indicating that oxygen-containing groups are fairly evenly distributed, with no significant surface enrichment or depletion.

Phosphorus content is higher in XPS than EDS when comparing atomic percentages. This suggests that phosphorus is surface-enriched, particularly in sample C-SC, possibly due to the doping or activation process leading to phosphorus-containing functional groups (e.g., phosphate, phosphonate) migrating toward or forming at the surface. The elevated P content in XPS indicates that phosphorus functional groups are more concentrated at the outermost surface, which could enhance surface-related properties such as adsorption or hydrophilicity. Phosphorus groups may contribute to acidity and provide additional adsorption sites, further improving dye uptake.

From to XPS data, both materials show high carbon content, indicating good carbonization and structural integrity (C 1s, 284.8 eV). Oxygen content reflects surface functional groups that can enhance hydrophilicity and interact with polar dye molecules (O 1s, 533.1 eV). Phosphorus likely comes from residual phosphate groups introduced during activation, which may enhance surface acidity or electron-donating properties (P 2p, 134.1 eV).

According to the XPS spectra (

Figure 7), the carbon C (1s) peak was deconvoluted into five main components: C=C sp

2 (284.5 eV), C–OH/O–C–O (286.6 eV), C=O (287.6 eV), COOR (288.8 eV), and π-π* shake-up (290.6 eV). The oxygen O (1s) peak was split into four main components: O=C (531.2 eV), Car–OH (533.6 eV), O=C-O-R/C-O-C/C-OH (532.5 eV), and O=C-O-R (534.5 eV).

Surface chemical characterization by XPS revealed that both carbons were predominantly composed of a well-developed graphitic carbon structure, indicating a degree of conjugation and structural order (C=C sp

2), with contents of 90.3% for C-PS and 87.4% for C-SC (

Table 4). Carbon from spruce cons showed a higher proportion of oxygen-containing groups such as hydroxyl/ether (C–OH/O–C–O, 3.8%), carbonyls including ketones, aldehydes (C=O, 1.5%), and esters/carboxylates (COOR, 3.4%) compared to analog from peanut shells. These functional groups are known to facilitate adsorption via hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. The spruce-based carbon is also characterized by a higher amount of π-π* shake-up satellite (4.0%). It occurs in conjugated systems (graphitic domains), indicating extended π-electron systems and structural order.

Based on XPS spectra of the O (1s), it was confirmed that spruce-based carbon had a greater abundance of carbonyl/quinone groups (O=C, 21.2%) and phenolic hydroxyl groups (Car–OH, 35.7%) than C-PS (

Table 5). Slightly higher ester content in C-SC could support acid-base interactions during adsorption. The enhanced oxygen functionality in C-SC likely contributes to its higher affinity for crystal violet dye through polar interactions.

High-resolution XPS spectra of the P (2p) region were recorded for both activated carbon samples (C-PS and C-SC). The results reveal that the binding energies and spectral profiles are identical for both samples, indicating that phosphorus exists in the same chemical states, regardless of the precursor used.

The main peak at 133.3 eV (P 2p3/2 A) is characteristic of phosphate species, where phosphorus is in the oxidation state (P5+). This indicates that phosphorus is primarily present in the form of phosphate groups at the surface. The secondary component at 136.0 eV (P 2p3/2 B), with a much smaller contribution (~6%), likely corresponds to more oxidized phosphorus species, such as polyphosphates or pyrophosphates. The presence of these forms may result from oxidative surface treatments or the condensation of phosphate species during carbon activation.

3.3. Crystal Violet Adsorption

Due to their properties, porous activated carbons are widely used to purify water from dye contaminants [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

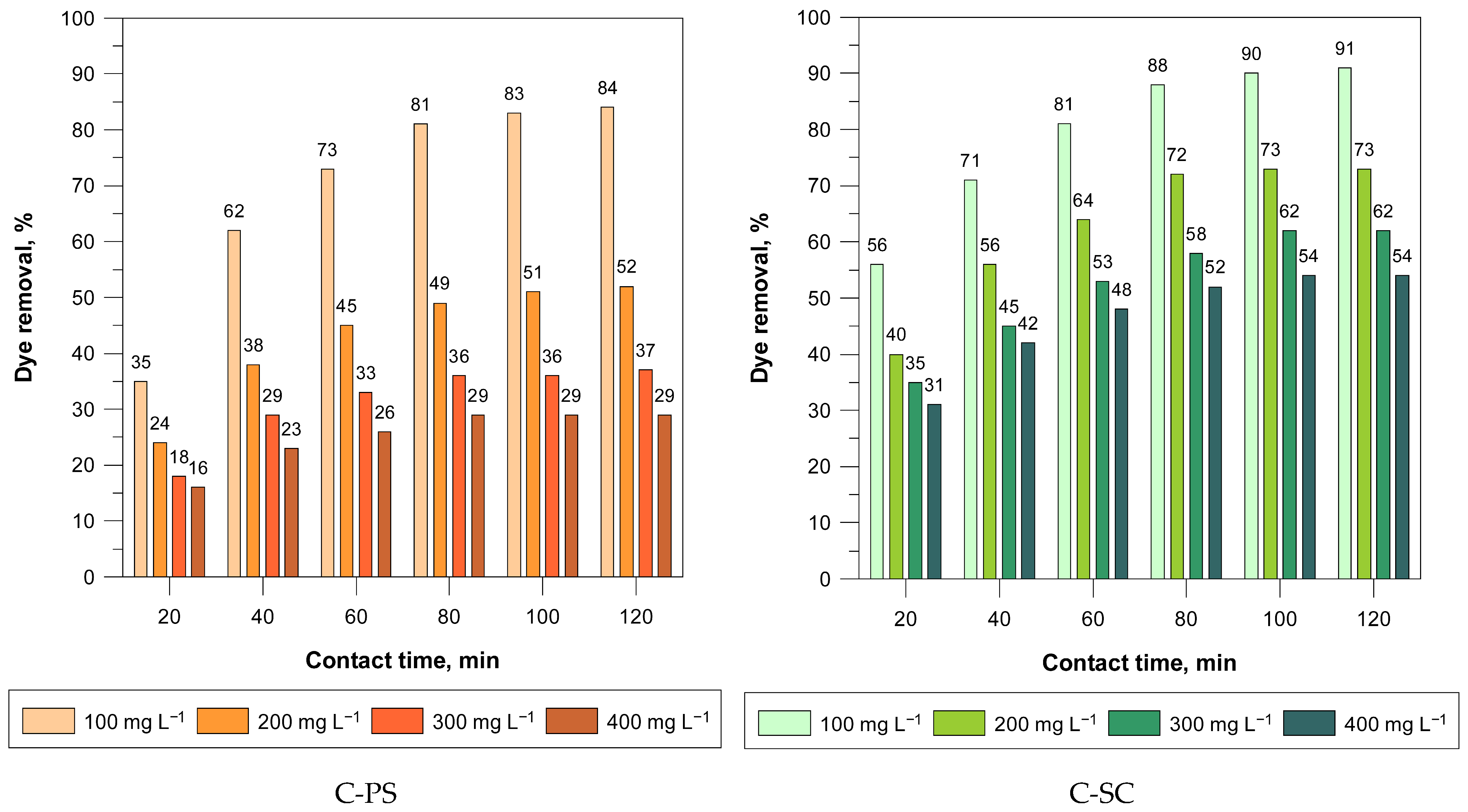

The performance of activated carbons derived from peanut shells (C-PS) and spruce cones (C-SC) for the removal of crystal violet dye was evaluated across a range of initial dye concentrations (100–400 mg L

−1) and contact times (20–120 min). According to Guzel et al., crystal violet dye molecules have a size of 1.4 nm × 1.4 nm [

29]. Abbasi et al. consider a more spatial structure with a triangular form of the distances between carbons at different nitrogens, which are, respectively, 0.9 nm × 1.0 nm × 1.1 nm [

30]. In each case, the molecular size allows for the CV molecules to diffuse into the meso- and macropores. Furthermore, hydrophobic interactions may occur between the nonpolar, graphitic structure of the carbons surface and the less polar aromatic groups of the CV molecule. Therefore, the results demonstrate significant differences in the adsorption efficiency between the two carbon sources, particularly at lower concentrations.

For both C-PS and C-SC, dye removal increased with longer contact times, indicating that the adsorption process is time-dependent and likely controlled initially by surface adsorption followed by slower pore diffusion. C-PS showed a steady rise in removal efficiency over time, reaching a maximum of 84% at 120 min for the 100 mg L−1 solution. In contrast, C-SC removal efficiency increased rapidly up to 90% and then plateaued, indicating a faster equilibrium.

C-SC consistently outperformed C-PS at all concentrations. At a concentration of 100 mg L

−1, C-PS achieved 84% elimination, compared to 91% for C-SC. This trend continued at higher concentrations, with both materials exhibiting a decrease in elimination efficiency with increasing concentration likely due to saturation of the active sites. C-PS maintained a significantly lower elimination percentage, particularly at a concentration of 400 mg L

−1 (29%) compared to C-SC (54%) (

Figure 8).

The adsorption kinetics of crystal violet onto phosphoric-acid-activated carbons derived from peanut shells (C-PS) and spruce cones (C-SC) were evaluated using pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models across four initial dye concentrations (100–400 mg L

−1) (

Table 6,

Figure S1). These models help to clarify the rate-controlling mechanisms and the likely nature of adsorption.

Kinetic modeling further elucidated the adsorption mechanism. Both the PFO and PSO kinetic models were applied, but the PSO model showed better fitting (R2 > 0.98), suggesting the existence of a chemisorption process.

The rate constants () for C-SC were generally higher than those of C-PS, indicating faster adsorption kinetics. The PSO model also predicted values closer match to the experimental adsorption capacity, particularly for C-SC, reinforcing its superior adsorption capability.

The equilibrium adsorption behavior of crystal violet on activated carbons derived from peanut shells (C-PS) and spruce cones (C-SC), both treated with phosphoric acid, was evaluated using the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D-R) isotherm models (

Table 7,

Figure S2). These models provide information on the nature of the adsorption process, surface characteristics, and the maximum adsorption capacity of the materials.

The Langmuir model assumes monolayer adsorption on a surface with a finite number of homogeneous sites and no interaction between the adsorbed molecules. The maximum capacities () of 11.37 mg g−1 for C-PS and 22.05 mg g−1 for C-SC confirm the improved superior adsorption efficiency that was observed experimentally.

C-SC provides more accessible or higher-energy adsorption sites, potentially due to better-developed porosity or favorable surface chemistry. C-PS had a higher Langmuir constant value (0.1763 L mg−1) compared to C-SC (0.0571 L mg−1), indicating a higher affinity for crystal violet at low concentrations, despite its lower capacity. Both materials fit well with the Langmuir model, but C-PS showed a slightly better correlation (R2 = 0.9281) than C-SC (R2 = 0.9821), indicating a more ideal monolayer adsorption behavior.

The Freundlich isotherm, which describes heterogeneous surface adsorption and multilayer formation, also fitted well (R2 > 0.999). The Freundlich exponent reflects favorable adsorption properties, and both materials had > 1, indicating favorable adsorption. The Freundlich constants () and heterogeneity factor () showed that C-PS had a higher values of those parameters compared to C-SC, suggesting stronger surface heterogeneity and more favorable adsorption sites on C-PS. However, the higher values for C-SC indicate that, despite slightly lower heterogeneity, C-SC have a greater adsorption capacity, likely due to their enhanced porosity and surface chemistry.

The Dubinin–Radushkevich (D-R) model provides insights into the adsorption mechanism, whether physical or chemical, and the porosity of the adsorbent. The process is considered to be chemisorption- or ion-exchange-controlled when the value is between 8 and 16 kJ mol

−1 and to be controlled by physical adsorption or van der Waals interactions when the value is below 8 kJ mol

−1 [

31]. The isotherm parameters revealed adsorption energies (

) approx. 0.084 J mol

−1 for the obtained carbons, which are well below 8 kJ mol

−1, indicating the presence of a physisorption process driven primarily by specific interactions. The D-R model had the weakest correlation for both materials (C-PS = 0.8001; C-SC = 0.7914), suggesting that it may not adequately describe the adsorption mechanism compared to the Langmuir and Freundlich models.

For both adsorbents, the Polanyi potential values showed a clear decreasing trend with increasing concentration, reflecting the gradual occupation of adsorption sites with decreasing energy. At the lowest concentration, C-PS exhibited a Polanyi potential of approximately 154.03 J2 mol−2, while C-SC exhibited a noticeably higher value of approximately 248.46 J2 mol−2. This indicates that the second carbon initially offers adsorption sites with significantly higher energy compared to the first.

With increasing concentrations, decreased in both cases, reaching values approaching 8.71 J2 mol−2 and 13.54 J2 mol−2, respectively, at the highest concentrations studied. The decreasing difference between the two carbons at higher concentrations indicates the saturation of the highest-energy sites and adsorption onto lower-energy sites, which is typical for heterogeneous adsorbent surfaces.

The observed differences in Polanyi potential correlate well with the differences in microporosity between the two adsorbents, which can be directly related to their porous structure (

Table 1).

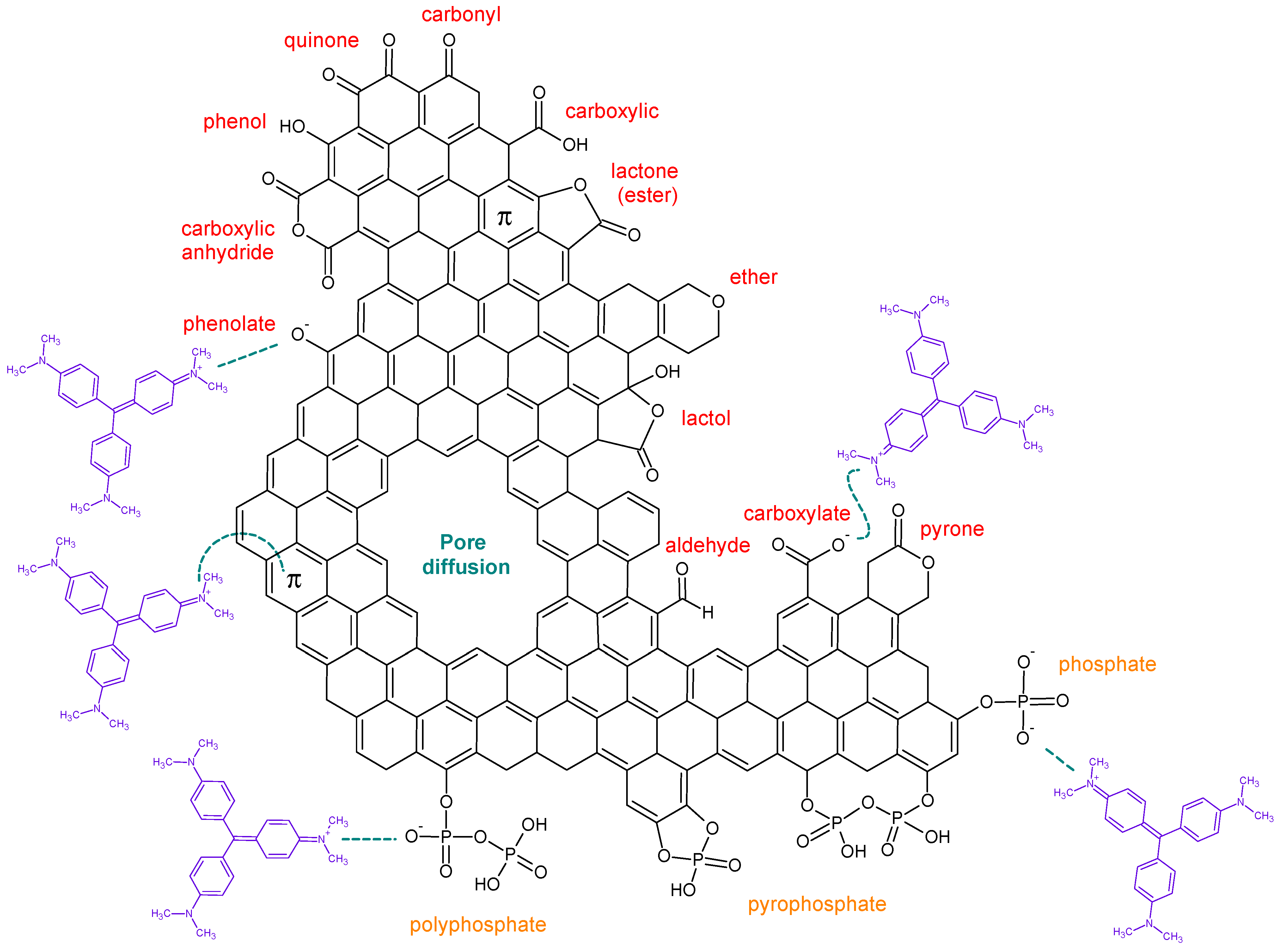

Pore diffusion, π–π electron donor–acceptor interaction, and H-bonding, as well as electrostatic interactions, are different types of adsorption mechanisms [

32].

Spruce-based carbon is characterized by a more oxidized functional group (XPS), higher phosphorus content (XPS and SEM-EDS), higher π–π* reaction intensity (aromatic interactions), more micropores, and higher adsorption capacity. All these features indicate enhanced physisorption, particularly through π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions with the cationic dye crystal violet.

Peanut-based carbon, although still rich in graphitic carbon and characterized by decent oxygenation, exhibits fewer surface functions, which explains the slightly lower adsorption capacity and a slight preference for physisorption at lower concentrations.

The superior adsorption performance of spruce-based carbon can be attributed to its balanced combination of a high surface area, enhanced microporosity, and rich surface chemistry with oxygen- and phosphorus-containing groups.

These properties enable efficient adsorption via multiple mechanisms (

Figure 9): physical adsorption through micropores and mesopores, which provide a large surface area and pore volume; and specific interactions, including hydrogen bonding, as well as π–π interactions between the aromatic rings of the dye and graphitic domains on the carbon surface, supported by the π–π* shake-up signals observed in XPS. While peanut-based carbon also showed promising adsorption behavior, its slightly lower porosity and fewer functional groups resulted in reduced dye uptake and slower kinetics.

Adsorption studies have shown that both materials are effective, but C-SC offers a higher capacity, while C-PS is characterized by a higher affinity and faster surface interactions at lower dye concentrations.

The CV adsorption capacity values in this work are comparable, or even higher, to those found in the literature. Loulidi et al. suggested that the maximum adsorption capacity in a monolayer was 12.2 mg g

−1 [

33], while Abbas et al. found that the maximum adsorption capacity was 20.95 mg g

−1 [

34].