Abstract

Hybrid buckypapers (BPs) composed of graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) hold great potential for applications in flexible electronics, electromagnetic shielding, and energy storage. In this study, hybrid BPs were fabricated and characterized to evaluate their structural, thermal, and electrical properties. Hybrid BPs with varying GNP/CNT mass ratios (0/100, 25/75, 50/50, 75/25, 85/15, 90/10, and 95/5 wt%) were prepared via vacuum-assisted filtration of well-dispersed aqueous suspensions stabilized by surfactants. The resulting hybrid GNP/CNT BPs were dried and subjected to post-treatment processes to enhance structural integrity and electrical performance. Characterization techniques included scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR), Raman spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms, and impedance spectroscopy (IS). The hybrid GNP/CNT BPs exhibited electrical conductivities comparable to conventional CNT-based BPs. At GNP concentrations of 25 to 50 wt%, electrical conductivity values approached those of CNT-based BPs, while at GNP concentrations between 75 and 90 wt%, a slight increase in conductivity was observed (171%). These results highlight a synergistic effect at lower CNT concentrations, where the combination of CNTs and GNPs enhances conductivity. The findings suggest that optimal conductivity is achieved through a balanced incorporation of both materials, offering promising prospects for advanced BP applications.

1. Introduction

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the development of new materials and structural designs for various applications, including the oil and gas, aerospace, medical, and automotive industries, among others [1,2,3]. Within this context, carbon is a highly versatile element capable of forming a wide range of structures with diverse properties. Advances in materials science, particularly in fabrication techniques and production technologies, have driven the emergence of novel carbon-based materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs), and graphynes, expanding beyond traditional forms such as graphite, which have garnered increasing attention [4,5,6,7,8,9].

Fullerenes, discovered in 1985, are spherical or ellipsoidal molecules composed of carbon atoms in sp2 hybridization. Their discovery paved the way for the synthesis of CNTs in 1991. CNTs are hollow cylindrical structures formed by sp2-hybridized carbon atoms arranged in a uniform hexagonal lattice, consisting of one or more layers of graphene. These nanostructures exhibit exceptional chemical and physical properties, including high tensile strength, elastic modulus, low density, and remarkable thermal conductivity and stability. Furthermore, their hydrophobic nature makes them highly promising for applications in separation sciences, electrochemistry, and various fields of materials science [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Buckypaper (BP) is a thin, porous film composed of carbon-based nanomaterials, typically fabricated through the filtration of well-dispersed suspensions [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. CNTs are widely employed in BP production due to their outstanding mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties, as well as their ability to form interconnected networks. During fabrication, CNTs self-assemble into highly entangled structures, resulting in lightweight, flexible, and conductive films. These characteristics make CNT-based BPs highly promising for applications such as electromagnetic shielding, energy storage, sensors, and composite reinforcement [16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

The development of hybrid BPs incorporating GNPs offers significant advantages by combining the unique properties of CNTs and graphene-based materials [20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The inclusion of GNPs enhances the structural integrity of BP, improving mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and thermal stability. Additionally, the synergistic interaction between CNTs and GNPs facilitates the formation of an interconnected network, optimizing electron transport pathways and enhancing overall performance [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Graphene-based materials, such as GNPs, have been widely studied due to their exceptional physical properties, enabling the development of materials with superior mechanical strength, electrical conductivity, and thermal efficiency [28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. In ideal graphene layers, sp2-hybridized carbon atoms are highly organized, promoting efficient electron transport and storage [32,33,34,35,36].

In this study, CNTs and GNPs were used to fabricate hybrid BPs. The preparation process was designed to integrate these nanomaterials, leveraging their complementary properties while overcoming the limitations of single-material BPs. Hybrid BPs provide greater control over porosity and density, making them highly suitable for applications in filtration, sensors, and energy storage. The synergistic combination of CNTs and GNPs also reduces aggregation and improves dispersion, resulting in more homogeneous and well-structured materials [20,21,22,23,24,25].

Another key advantage of hybrid BPs is their multifunctionality, including flexibility, lightness, and chemical resistance. These attributes make them highly versatile for a range of applications, including electromagnetic shielding, supercapacitors, batteries, and biomedical devices, while also contributing to cost reduction in material production [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30].

Common BP fabrication techniques include vacuum filtration [34,35,36,37], inkjet printing [35,36,37,38], dip coating [36,37,38,39], and chemical vapor deposition with floating catalysts [37,38,39,40,41]. Among these, vacuum filtration is the most widely employed method. It involves dispersing nanofillers in solution, followed by filtration through a suitable membrane. As the suspension passes through the filter, the nanomaterials gradually deposit to form thin films with high porosity. The resulting BPs exhibit a highly macroporous structure, with pore sizes ranging from 10 to 15 µm, low density, and high electrical conductivity [33,34,35,36].

Several studies have investigated hybrid BP preparation. Dichiara et al. [21,22,23,24] explored the interaction between GNPs and CNTs for the development of adsorbents, demonstrating that CNTs form an extensive network in which GNPs are embedded. This arrangement increases the distance between nanoparticles, enhancing adsorption by enlarging the contact area between the solute and nanoparticles.

Patole et al. [22,23,24,25] investigated hybrid BP composed of 50 wt% CNTs and 50 wt% GNPs, fabricated via a wet filtration-zipping process using GNPs with fewer than 10 layers and multi-walled CNTs. Their study reported a 247% increase in electrical conductivity compared to pure CNT-based BP. Additionally, the inclusion of GNPs in the CNT network resulted in increased transverse expansion under load, leading to a negative Poisson’s ratio.

In this study, hybrid BPs were prepared using GNPs with four graphene layers. This specific geometry was selected to enhance interactions with CNTs, promoting better dispersion and integration between the two materials. The study focuses on examining how this GNP structure influences the structural, electrical, and thermal properties of hybrid BPs, intending to maximize their potential for a wide range of applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The following materials were used to prepare the hybrid BPs in this work:

Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs) with an average length of 1.5 µm, an average diameter of 9.5 nm, purity of 90%, and an average aspect ratio of 158, specifically grade NC 7000 from Nanocyl S.A. (Sambreville, Belgium); Graphene nanoplatelets (GNP) supplied by CheapTubes (Grafton, VT, USA), with a number of layers of 4, an average thickness of less than 4 nm, a lateral size ranging between 1 and 2 µm, and a purity greater than 99%.

The surfactant Triton X-100® (Dinâmica Química Contemporânea Ltd., Indaiatuba, Brazil) was used in the dispersion of carbon materials. It has a critical micelle concentration ranging from 0.22 to 0.24 mmol/L (0.02 wt%) and a molecular weight of 646.87 g/mol. To remove the surfactant, acetone with a purity of 99.63% (also supplied by Dinâmica Química Contemporânea Ltd., Indaiatuba, Brazil) was used. For the preparation of hybrid BPs, it was necessary to use a sacrifice woven blanket. In this case, a polyacrylonitrile (PAN) blanket, prepared by electrospinning, was used. For this purpose, PAN (Mn = 267,000 g/mol) supplied by Radici Group (Sumaré, SP, Brazil) was selected. To remove the PAN blanket after the BP formation, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) with a purity of 99.65%, supplied by Dinâmica Química Contemporânea Ltd. (Indaiatuba, Brazil), and isopropyl alcohol with a purity of 99.8%, also supplied by Dinâmica Química Contemporânea Ltd. (Indaiatuba, Brazil), were used.

2.2. Experimental Characterization of the CNT and GNP

Raman spectroscopy analyses of the CNTs, GNPs and BPs were conducted to assess their structural characteristics. A HORIBA Scientific instrument LabRAM HR Evolution, coupled to a CCD detector (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan) was used, employing a He-Ne laser (532 nm), using a grating of 600 g·mm−1. The 100× objective was used, and the data acquisition conditions were: ND filter was set to 10%. Peak positions of the spectra were obtained by fitting a Lorentzian function using LabSpec 6 software. The Raman microscope is equipped with a motorized stage for automated XYZ movement, allowing Raman mapping.

X-ray measurements of the CNTs, GNPs and BPs were conducted using a Rigaku diffractometer (Ultima IV model) operating at 40 kV and 30 mA, with copper Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å) and a nickel filter to block Kβ radiation. A 2ϴ range of 5° to 90° was scanned at a rate of 10° per minute. The average thickness of CNTs was estimated using Scherrer’s equation (Equation (1)), while the average number of walls was determined as a ratio of the average thickness to the inter-tube distance, calculated using Bragg’s law (Equation (2)) [42,43].

where τ is the mean size of the ordered (crystalline) domains; K is a dimensionless shape factor (0.9); λ is the X-ray wavelength; β is the line broadening at half the maximum intensity and θ is the Bragg angle.

where λ is the wavelength, θ is the glancing angle and d is a grating constant.

Morphological characterization of the CNTs and GNPs was performed using field emission gun scanning electron microscopy (FEG-SEM). The images were obtained with a TESCAN MIRA3 operating at 5 kV. The carbon materials (CNT and GNP) were mounted on a stub with carbon tape and coated with a thin layer of gold for 90 s using a Quorum Q150RS Plus sputtering device.

2.3. Preparation of Sacrifice Woven Blanket

The preparation of PAN electrospun nanofibers (PEN) blankets was carried out according to Oliveira Junior et al. [44]. The process began with solubilizing 1.5 g of PAN in 13.5 mL of DMF on a magnetic stirring plate at 120 rpm for 1 h at 100 °C. Subsequently, the solution was placed in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min to ensure homogeneity. It was then transferred to a 20 mL glass syringe fitted with a 30 mm × 0.8 mm needle.

During the electrospinning process of PAN blankets, the following parameters were applied: temperature of (25 ± 5) °C, relative humidity of (55 ± 5)%, infusion rate of 1.5 mL/h, working distance (syringe tip to collector) of 80 mm, collector rotation speed of 1000 rpm, and voltage of 14 kV.

2.4. Preparation of Hybrid BPs

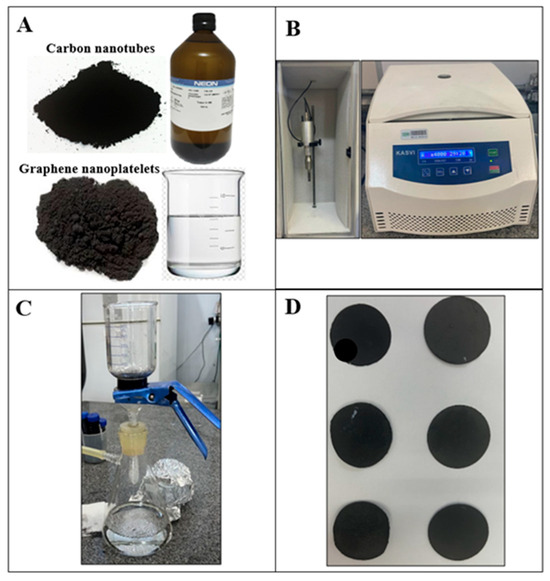

The preparation of BPs (Figure 1) was carried out according to Rojas et al. [13]. Table 1 presents the nomenclature and compositions of the hybrid BPs. The preparation process involved dispersing different concentrations of GNP/CNT (0/100, 25/75, 50/50, 75/25, 85/15, 90/10, and 95/5 wt%) in 200 mL of distilled water and 2 g of Triton-X100® surfactant using high-power sonication with an ultrasound tip (Sonics, Newtown, CT, USA, Vibra-Cell VCX750, 20 kHz, 750 W). The dispersion was performed in an ice bath to maintain a temperature below 25 °C and prevent overheating. The ultrasound parameters included a total processing time of 40 min at 40% amplitude, with a pulse cycle of 5 s on and 3 s off.

Figure 1.

BP production process: (A) materials used in production, (B) ultrasound tip and centrifuge, (C) vacuum filtration process and (D) BPs.

Table 1.

Nomenclature and composition of BPs.

After sonication, the suspension was centrifuged (KASVI K14-4000) (São José dos Pinhais, Brazil) at 4000 rpm for 30 min to separate aggregates from the dispersed particles. The supernatant was then vacuum filtered through a Nylon® membrane (45 mm diameter, 0.45 µm pore size) with four PAN blankets (each measuring 45 mm × 45 mm) stacked perpendicularly on the membrane.

The surfactant was removed by washing with acetone. Finally, the BP was carefully removed from the filtration membrane and dried at room temperature for 15 h. Each side of BP/PEN was sequentially immersed in 25 mL of DMF at 60 °C using a Corning® PC-420D hot plate (Corning, NY, USA) for 10 min. It was then immersed in 25 mL of isopropyl alcohol for another 10 min and subsequently dried at room temperature for 15 h.

2.5. Experimental Characterization of the Hybrid BPs

2.5.1. FEG-SEM Analysis Procedure

Morphological characterization of the hybrid BPs was conducted using FEG-SEM. Images were acquired with a TESCAN MIRA3 (TESCAN Group, Brno, Czech Republic) operating at 5 kV. Sample preparation involved mounting on carbon double-sided tape and sputter-coating with a thin gold layer to enhance electrical conductivity.

2.5.2. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

FT-IR was conducted using a PerkinElmer Spectrum 2000 spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Scanning was performed in the range of 3700 to 700 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 after averaging 20 scans.

2.5.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) Procedure

Thermogravimetric analysis was performed on a Netzsch Iris® TG F1 instrument (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Baviera, Germany) with a heating rate of 20 °C/min under nitrogen and synthetic air flow at 50 mL/min. The temperature range analyzed was 40–800 °C and the mass of samples was 0.01 g.

2.5.4. Nitrogen Adsorption Isotherms Methodology

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms were obtained using a Quantachrome Nova-e series instrument. Sample preparation involved degassing under vacuum at 80 °C for 5 h. The surface area was determined by the BET equation [45], while total pore volume was calculated at P/P0 = 0.98 using NovaWin® 11.01 software.

2.5.5. Impedance Spectroscopy (IS) Methodology

Electrical characterization was conducted via IS measurements using a Solartron SI 1260 Impedance/Gain-phase Analyzer (Solartron Analytical, AMETEK, Farnborough, Hampshire, UK). A 0.5 V alternating current was applied over a frequency range of 1–105 Hz. To ensure electrical contact, a thin layer of gold/palladium alloy was deposited on both sides of the samples using a metallizer (Bal-tec, MED020, Bal-tec, MED020, Bal-Tec AG, Balzers, Liechtenstein), forming a metal-composite-metal structure. The AC electrical conductivity (σAC) of the materials was calculated based on the sample thickness (l), contact area (A), and impedance modulus (|Z|), as described in Equation (3).

3. Results

3.1. Results of Characterization of the CNT and GNP

The Raman spectrum of carbon materials with sp2 hybridization exhibits three characteristic bands. The G band appears at approximately 1580 cm−1 and corresponds to the C=C stretching mode in sp2-hybridized carbon structures. The position and intensity of this band depend directly on the degree of graphitization, which reflects the structural perfection of the sp2 domains. As graphitization increases, the G band narrows and shifts to lower wavenumbers. The D band occurs at approximately 1350 cm−1 and is associated with structural defects in the sp2 carbon network, frequently designated as disorder, or vibrational modes related to edge atoms, typically observed in smaller graphitic domains. These assignments and interpretations are consistent with previously reported studies [46,47]. The intensity ratio between the D and G bands (ID/IG) serves as an indicator of the degree of disorder in the sample. The 2D (or G’) band, appears at approximately 2700 cm−1 and is related to the structural organization within the bi-dimensional plane of graphitic materials [48].

Figure 2A presents the Raman spectra of CNT and GNP samples, where the three previously discussed bands are observed in all spectra. In the Raman spectrum of GNP, two well-defined main bands are present: The G band (IG) at 1561 cm−1 and the D band (ID) at 1337 cm−1. The ID/IG ratio obtained was approximately 0.81, and the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the 2D band was 43 cm−1.

Figure 2.

(A) Raman spectra showing the D, G, and 2D bands, (B) Lorentzian fitting curve applied to the 2D band into four components (peaks 1–4), and (C) X-ray diffraction patterns of CNT and GNP.

The crystallite size (La), the distance between defects (LD), and the defect density (nD) were calculated according to Cançado et al. [49,50], using Equations (4)–(6), respectively.

where ID and IG are the intensities of the D and G peaks, respectively, and λl is the laser wavelength in nanometers (nm).

The crystallite size (La) calculated using Equation (4) was approximately 250 nm. The average distance between defects and the defect density, calculated using Equations (5) and (6), were 49 nm and 1.19 × 1010 cm−2, respectively. These results are consistent with those reported by Cançado et al. [49,50] in their studies.

The G band corresponds to the interaction of an E2g phonon in the stretching of sp2 bonds within the graphene planes of the GNP structure, indicating regions of high structural crystallinity in graphene layers. In contrast, the D band is associated with sp3-hybridized carbons at the edges, structural defects, or amorphous regions. This band primarily corresponds to the pre-existing defects in the graphene layers, especially at the edges of the graphene sheets in GNP.

In addition to the results presented above, it is possible to infer the number of layers present in the samples through the analysis of the 2D band using Lorentzian curve fitting. Figure 2B shows this fitting performed for the GNP sample. It can be observed that the best fit was achieved with four curves, which is typically associated with bilayer graphene [51,52,53,54]. This result is consistent with the material specifications, which state that it has a number of layers of four.

The four components of the 2D peak in bilayer graphene can, in principle, be attributed to two distinct mechanisms: the splitting of phonon branches or the splitting of electronic bands [51,52,53,54]. In bilayer graphene, interaction between the graphene layers causes the π and π* bands to split into four, with different splittings for electrons and holes. The incident laser light can couple only two pairs among these four bands [51,52,53,54]. On the other hand, the two nearly degenerate phonons from the highest optical branch can couple all electronic bands with one another. The four resulting processes involve phonons with momenta q1B, q1A, q2A, and q2B, each corresponding to phonons with different frequencies due to the strong dispersion of the phonon branches near the K point. These phonons give rise to the four peaks observed in the Raman spectrum of bilayer graphene.

However, phonons q1A and q2A, which scatter between bands of the same type, are associated with more intense processes than q2A and q2B, since the portion of phase space where the double resonance condition is satisfied is larger [51,52,53,54,55].

For CNTs, the Raman spectrum exhibited D and G bands at 1344 and 1577 cm−1, respectively. The D band is associated with carbons near vacancies, defects, or structural disorder, while the G band corresponds to E2g phonon interaction modes in the parallel plane between nanotube layers, reflecting structural integrity [55]. Moreover, CNTs consist of concentric graphene sheets cylindrically rolled up. Their Raman spectra are similar to those of defective pyrocarbons, exhibiting significantly more intense D and 2D bands than those observed in GNP, indicating a higher degree of disorder [53].

Figure 2C presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of CNT and GNP, further supporting the findings from Raman spectroscopy. In the XRD pattern of GNP, a characteristic peak at 26.52° and a minor peak at 54.5° are observed, corresponding to the (002) and (004) planes, respectively, consistent with similar observations in other studies [56,57]. The crystallographic reference used was JCPDS 00-012-0212. These peaks are associated with the d-spacing between graphene sheets in GNP [58,59]. The interplanar distance, calculated using Bragg’s Law, was 0.337 nm, a value similar to that of graphite (d002 = 0.336 nm) [60,61].

To further analyze the GNP diffractogram and determine the number of GNP layers, the Scherrer equation was applied, resulting in a value of approximately 0.85 nm for the GNP thickness and 3.4 Å for the interwall distance. Based on this thickness, the GNP can be classified as ordered graphene nanoplatelets (number of layers = 4).

In the XRD pattern of CNT, the most intense peak was observed at 25.81°, corresponding to the diffraction of the (002) planes, which is related to the interlayer spacing of the multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) [62]. The interlayer spacing of 3.45 Å was determined from the 2θ value of this peak. Furthermore, using this peak, the Dhkl value was determined to estimate the average diameter and the number of layers. The obtained Dhkl value was approximately 29 Å, indicating that the MWCNTs used have an average of eight layers. These results are consistent with findings from other studies in the literature [58,63].

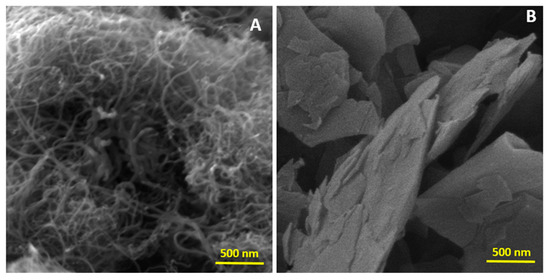

Figure 3 presents the FEG-SEM images of the CNT and GNP samples. In Figure 3A, the CNTs appear as single graphene sheets rolled into cylindrical shapes, with a length significantly greater than their diameter. Due to their high aspect ratio, CNTs tend to cluster and intertwine along their length axis, driven by strong Van der Waals interactions [24].

Figure 3.

FEG-SEM images of (A) CNT and (B) GNP.

In Figure 3B, the FEG-SEM image reveals the presence of GNPs. This GNP has an average thickness of less than 4 nm and consists of four graphene layers. The sheets stack closely into aggregates due to interplanar π–π interactions [26,27,28].

3.2. Characterization Results of the Hybrid BPs

3.2.1. FEG-SEM Results

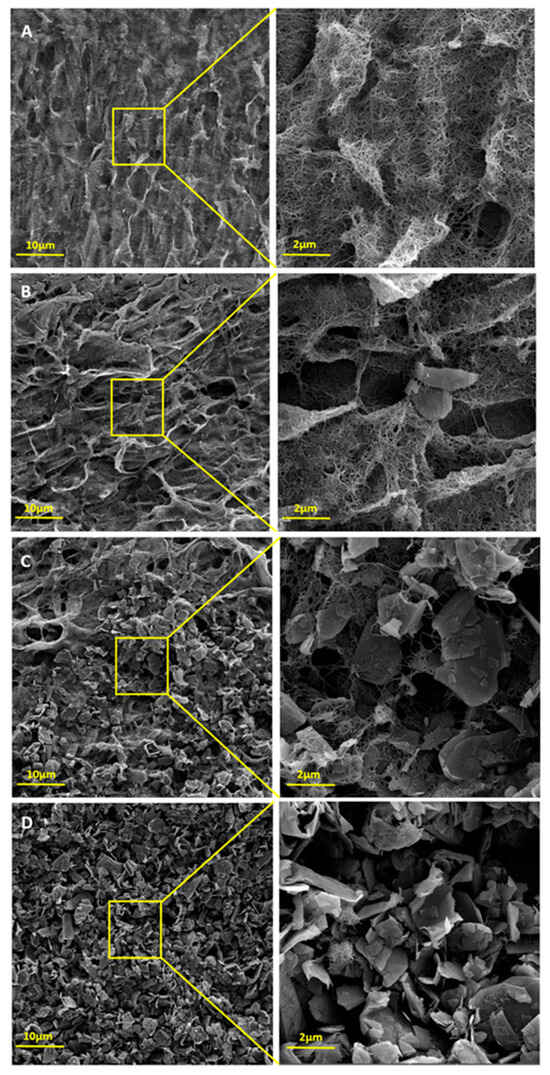

Obtaining BPs composed entirely of GNP was not feasible, as at this concentration made the BP was highly extremely brittle and unable to form free-standing films. To address this, CNTs were added as secondary phase, allowing the successful fabrication of BPs with up to 95 wt% GNP.

Figure 4 presents the FEG-SEM images of hybrids BPs with GNP/CNT compositions of 0/100, 25/75, 50/50, and 95/5. The morphologies of CNT and GNP are clearly distinguishable. In the CNT-based BP (Figure 4A), only entangled nanotube cylinders are visible, showing a more uniform morphology with greater interaction among the CNTs. In Figure 4B, small amounts of GNP are visible within the CNT entanglements. While GNPs interacted with CNTs and contributed to hybrid BP formation, they made the BP more fragile and less uniform, likely due to their larger dimensions. These observations became even more evident when attempting to remove the produced BP from the filter, as manual handling alone caused its fragmentation. As the GNP content increases, more GNP sheets and fewer entangled CNTs are visible, with this trend most evident in Figure 4D, which has the highest GNP content.

Figure 4.

FEG-SEM images of (A) GNP/CNT 0/100, (B) GNP/CNT 25/75, (C) GNP/CNT 50/50, and (D) GNP/CNT 95/5 BPs.

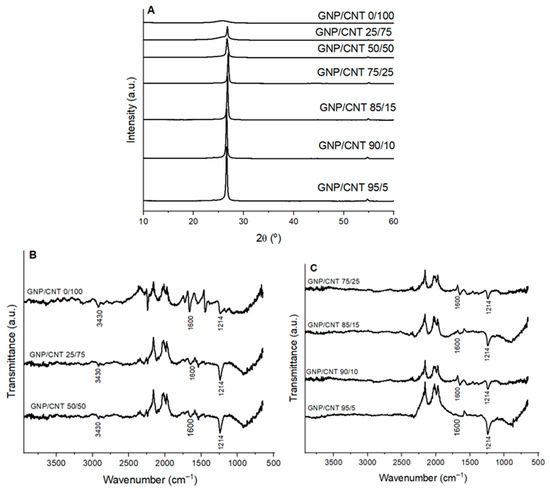

3.2.2. Structural Characterization: XRD, FT-IR, and Raman Spectroscopy

Figure 5A presents the XRD spectra of GNP/CNT 0/100 BP and hybrid BPs with different GNP and CNT concentrations. The spectrum of GNP/CNT 0/100 closely resembles that of neat CNT, showing only the intense peak at 25.81°. In the hybrid BPs, the CNT peak weakens and broadens due to the hybrid interaction. As GNP concentration increases, the intensity of the 26.52° GNP peak rises, and a new peak at 54.5° emerges, characteristic of GNP. These results align with FEG-SEM observations and previous studies [28,29,30].

Figure 5.

(A) XRD patterns, (B,C) FT-IR spectra of GNP/CNT 0/100 BP and hybrid GNP/CNT BPs with different GNP and CNT contents.

Figure 5B,C presents the FT-IR spectra of GNP/CNT 0/100 BP and hybrid BPs with different GNP and CNT contents. In the case of GNP/CNT 0/100, two weak bands appeared at 3430 cm−1 (O–H stretching vibration from surface groups) and 1600 cm−1 (conjugated –C=C– bonds) [64]. Consistent with XRD and FEG-SEM results, characteristic CNT and GNP peaks coexist in the FT-IR spectra of the hybrid BPs [65,66]. The peaks observed in the hybrid BPs can be attributed to the O–H stretching vibrations of intercalated water molecules and structural OH groups (3430 cm−1), skeletal vibrations of non-oxidized graphitic domains (1600 cm−1), and C–OH stretching vibration (1214 cm−1) [67,68]. The GNP/CNT interaction requires further investigation using Raman spectroscopy. Similar results have been reported by other authors [25].

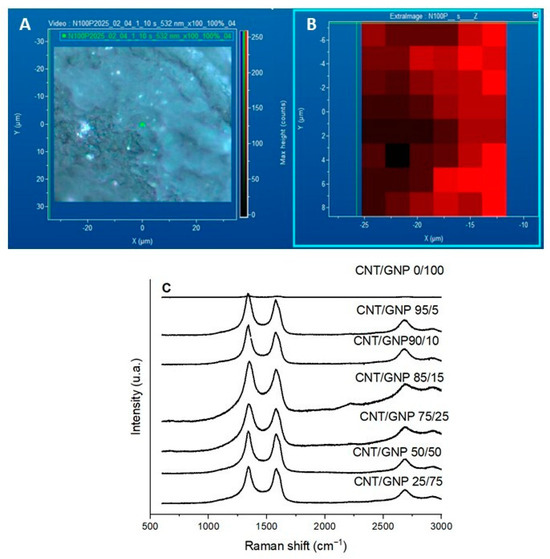

Surface mapping of the BP was carried out to detect the presence of GNP and CNT and to observe their distribution. Figure 6A shows a typical optical microscopy image of the surface of a CNT/GNP 50/50 sample. The GNP smooth surface is highly reflective and is observed as bright spots in the microscopy image. The spatial resolution does not allow to acquire the Raman spectra of single GNP platelets; however, the Raman spectrum reflects the presence of the two nanomaterials, measuring the intensity of the 2D peak. Figure 5B shows the map of the distribution of GNP and CNT across the sample for the BP with a 50/50 composition.

Figure 6.

(A) Micrograph and (B) mapping of the CNT/GNP 50/50 sample, and (C) Raman spectra for CNT/GNP 0/100 BP and hybrid CNT/GNP BPs with different GNP and CNT contents.

The Raman spectra of the compositions studied in this work are presented in Figure 6C. In the CNT/GNP 0/100 sample, which corresponds to the buckypaper composed only of CNTs, the relatively weak ID and IG peaks are mainly due to the morphology of the CNT network and the orientation effects during Raman measurement. The dense and entangled CNT bundles in the buckypaper can lead to partial laser absorption and multiple scattering, reducing the effective Raman signal intensity. Additionally, local heating and light shielding effects between overlapping nanotubes may further attenuate the detected signal. No discernible changes are observed in the spectra after increasing the CNT/GNP ratios. Only the two peaks corresponding to the D band (1350 cm−1) and the G band (1580 cm−1) are detected, and their relative intensities remain almost constant up to the 50/50 ratio. However, after the addition of higher GNP concentrations, a spectral change occurs: the D band shows a noticeable increase in intensity. This is a typical characteristic of CNTs, as they contain more defect sites [69,70].

The structural quality of the carbon-based materials was further assessed by analyzing their Raman spectra, particularly the ID/IG ratio, which reflects the relative intensities of the disorder-induced D band and the graphitic G band. This parameter is widely used as a measure of defect density and structural disorder in sp2 carbon materials. As shown in Table 2, the BP samples exhibited ID/IG ratios greater than 1, which is indicative of a high degree of disorder and the presence of numerous structural defects, such as vacancies, edges, dopants, or distortions in the carbon lattice. These results also suggest a reduction in the size of graphitic domains, implying that the well-ordered sp2 regions are fragmented into smaller domains. Notably, the CNT sample displayed a higher ID/IG ratio compared to the GNP, further confirming its greater structural disorder. These findings are consistent with the morphological and compositional characteristics previously discussed [51,52,53,54].

Table 2.

Intensities of the D and G bands (ID and IG) and the corresponding ID/IG ratios for the analyzed materials.

3.2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) Results

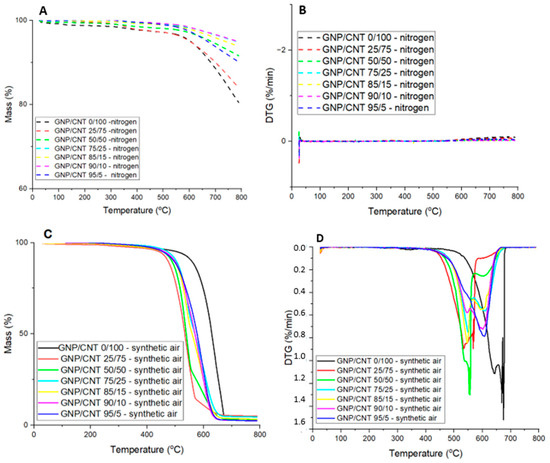

Figure 7A,B show the TGA and first derivative (DTG) curves of the BPs heated under nitrogen. Figure 7A presents the thermal degradation behavior of BPs under an inert atmosphere (nitrogen), presenting the weight loss as a function of temperature. The degradation of GNP/CNT 0/100 begins at approximately 360 °C, which is attributed to the thermal degradation of the CNT graphene walls with structural defects [71]. All the compositions follow a similar thermal degradation trend; however, as the GNP content increases, the thermal stability increases as well. The second thermal degradation process starting near 500 °C is common to all BP; however it presents higher thermal decomposition rates for the CNT-dominant compositions. The BP GNP/CNT 25/75 exhibits a similar behavior compared to GNP/CNT 0/100, likely due to the higher CNT content of its composition, while higher GNP compositions show higher thermal stability. The residual mass at 800 °C is approximately 80% for GNP/CNT 0/100 and between 90 and 94% for hybrid BPs. By the end of the analysis, the BP degradation process is not fully completed, likely due to the stable carbon sp2 configuration and minimum structural defects of CNTs and GNP materials.

Figure 7.

(A) TGA curves in nitrogen, (B) DTG curves in nitrogen, (C) TGA curves in synthetic air atmosphere, and (D) DTG curves in synthetic air atmosphere for GNP/CNT 0/100 BP and hybrid GNP/CNT BPs with different GNP and CNT contents.

Figure 7C,D show the TGA and first derivative (DTG) curves of the BPs heated under an oxidizing atmosphere (synthetic air). According to the literature, the decomposition temperature of Triton is around 300 °C [72]. In Figure 7C,D, a slight downward trend in the thermal curve can be observed starting at this temperature, suggesting the onset of Triton degradation in the sample. Although the change is not very pronounced, likely due to the small amount of residual surfactant, the data indicate that some degradation is indeed taking place in this temperature range.

Due to the strong affinity of carbon and oxygen [73,74,75], CNTs and GNPs react with oxygen at temperatures near 500 °C, leading to combustion. Therefore, these materials should be used under oxidizing atmospheres at temperatures well below 500 °C to maintain structural integrity [76,77]. The TGA curves of the BPs reveal a steep weight loss process constituted by two distinct mass loss events for all compositions, as observed on the corresponding DTG curves. The two peaks of the DTG curve, representing the maximum rate of thermal decomposition of two processes (Tmax1 and Tmax2) are observed at different temperature ranges, depending on the GNP and CNT content. It is interesting to note that the BP with a lower GNP contents (25 and 50%) present Tmax2 at lower temperatures near 550 °C, higher GNP contents (75–95%) present Tmax2 near 600 °C, while CNT alone shifts the Tmax2 towards 675 °C, the latter exhibiting the greater thermal stability of all BP. These observations are summarized in Table 3, presenting the temperature at the onset of degradation (Tonset), Tmax1, Tmax2, and the residual mass remaining at 800 °C for all BPs. The results indicate that the starting degradation temperature, or thermal degradation onset temperature, is also affected by the GNP content. This effect is particularly evident for the GNP/CNT 0/100 BP in synthetic air, where thermal degradation begins around 411 °C, with maximum decomposition rates at 643 °C and 675 °C, resulting in a residual mass of approximately 4.5%. This residual mass is attributed to the presence of catalytic metals and impurities in the CNT [78]. For hybrid BPs analyzed in synthetic air, the total mass loss ranges from approximately 2.5% to 4.5%.

Table 3.

Thermal degradation onset temperature (Tonset), maximum decomposition rate temperatures (Tmax1 and Tmax2), and residual mass for BPs.

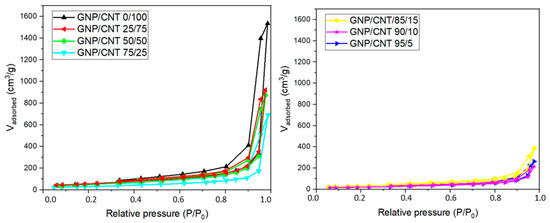

3.2.4. Nitrogen Adsorption Isotherms Results

Information on the surface area and total pore volume of the BPs was obtained through the analysis of nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms. Figure 8 presents the nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms obtained for all the BPs studied. All the isotherms can be classified as type II, characteristic of non-porous materials, and type IV, exhibiting hysteresis at higher relative pressures, according to IUPAC [79]. Above a relative pressure of 0.9, a sharp increase in the adsorbed amount occurs, accompanied by a well-defined hysteresis loop, which is associated with the presence of mesoporosity. The isotherm for the GNP/CNT 0/100 BP closely resembles those previously reported for other BPs prepared using the same type of CNT and low molecular weight dispersants [80]. The GNP/CNT 0/100 BP exhibits a higher amount of nitrogen adsorption at a relative pressure of 0.8, indicating a more prominent presence of mesoporosity compared to the hybrid GNP/CNT BPs. This enhanced mesoporosity can be attributed to the blocking effect of the CNT mesoporosity by the GNP. These results suggest notable differences in the internal morphologies between the hybrid GNP/CNT BPs and the CNT-based BP. Additionally, the layer-like structure of the GNPs creates tortuous and complex pathways for gas molecule diffusion, which can be associated with the reduction in the measured permeated volume as the GNP content increased [81].

Figure 8.

N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms of GNP/CNT 0/100 BP and hybrid GNP/CNT BPs with different GNP and CNT contents.

The surface area and total pore volume of the BPs are important characteristics that influence permeability performance. The surface area results obtained using the Brunauer, Emmet and Teller (BET) method and the total pore volume determined at a relative pressure of 0.95 (V0.95) are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Surface area (SBET) and total pore volume (V0.95) values for the BPs.

The surface area for the GNP/CNT 25/75 was 210 m2/g, which is similar for the CNT-based BP (205 m2/g). Nevertheless, GNP has a significantly larger width, which may have contributed to the reduction in surface area observed in the hybrid BPs compared to the CNT-based BP. As the GNP content increases in the BP compositions, the SBET value tends to decrease, likely due to the larger size of the GNPs compared to the CNTs. Due to their higher surface area, CNTs exhibit stronger interactions among themselves, resulting in BPs that are less brittle and more flexible, as evidenced by their morphological characteristics.

In summary, the hybrid BPs exhibit a more compact structure with reduced porosity, attributed to the shape characteristics of both carbon nanomaterials, which interact synergistically to form a more efficiently packed and closed structure. The space between the CNT and GNP aggregates is almost eliminated, indicating that incorporating GNP enhances the dispersion of CNTs within the resulting network, as evidenced by the FEG-SEM images and supported by other studies [82,83,84].

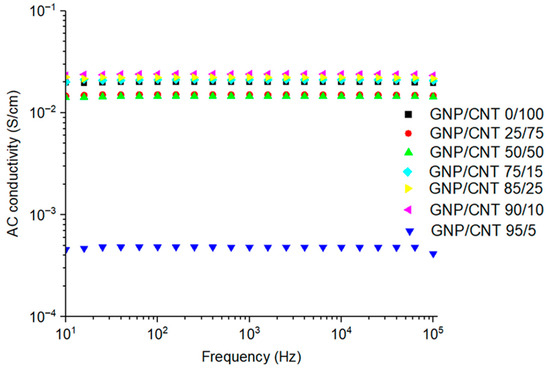

3.2.5. Impedance Spectroscopy (IS) Results

Impedance spectroscopy (IS) is a good method to evaluate the complex electrical behavior of BPs, providing valuable insights into their morphology [85]. The electrical conductivity (σ) response depends on the formation of conductive paths that involve physical contact, as well as the proximity and continuity of these paths throughout the sample. These conductive paths must be capable of polarizing and interacting with the incident electric field to generate an electric current.

The volumetric conductivity (AC) was measured through IS analysis of the BPs, and the results are illustrated in Figure 9. For all compositions, the BPs exhibit similar trends of the logarithmic plots of AC versus frequency. The GNP/CNT 0/100 exhibited AC electrical conductivity comparable to that of the hybrid samples. This behavior can be attributed to the saturation of the percolation threshold in the CNT network, combined with compensating effects introduced by the GNPs, such as enhanced packing density and larger interfacial contact area. Although GNPs tend to reduce the number of conductive CNT–CNT junctions, their incorporation can improve overall charge transport uniformity by decreasing local resistance variations. As a result, both pure CNT and hybrid buckypapers display similar levels of AC conductivity in the order of 10−2 S/cm.

Figure 9.

AC volumetric conductivity of 0/100 GNP/CNT buckypaper and GNP/CNT buckypapers with varying GNP and CNT contents.

The synergistic effect of the incorporation of GNP/CNT is evident in Figure 9. The composition of 25 to 50 wt% of GNP in the BP maintains the electrical conductivity comparable to that of CNT-based BP. Higher GNP concentrations ranging from 75 to 90 wt% induce a slight increase in electrical conductivity relative to the GNP/CNT 0/100 composition. These results suggest that low amounts of CNT may be sufficient to form conductive pathways, as reported in the literature [43,86]. However, when the GNP content reached 95 wt%, the AC conductivity decreased from approximately 10−1 S/cm (CNT-based BP) to ~10−3 S/cm (GNP/CNT 95/5). The predominance of GNP in the BP, interrupting the CNT network, affects the electrical conductivity, hindering the flow of electric current. This reduction may relate to the distinct morphology of the GNP compared to the CNT. The 1D shape of CNT and their small size result in a large number of CNT, even at low weight content, facilitating the formation of an entangled network and establishing conductive pathways. In contrast, the large lateral size and conductivity of the 2D GNPs will contribute to the formation of conductive paths; however, this requires the presence of a CNT network that extends these conductive pathways throughout the BP.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the feasibility of producing hybrid buckypapers (BPs) with tunable properties by varying the ratio of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs). The presence of CNTs, even in small amounts, was crucial to maintain the structural integrity of the BPs, enabling the fabrication of flexible and homogeneous hybrid membranes. The GNP/CNT ratio significantly influenced the thermal stability, electrical conductivity, surface area, and porosity of the materials. Notably, hybrid BPs exhibited enhanced thermal stability under an inert atmosphere and maintained high electrical conductivity across a broad range of compositions, with synergistic effects observed at intermediate GNP contents (75–90 wt%). These findings highlight the potential of hybrid BPs as lightweight, multifunctional materials for applications requiring customizable thermal, electrical, and barrier properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva), F.P., M.C.P. and E.B.; methodology, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva), T.d.S. (Thiély da Silva), R.C., R.R., G.M., L.M., B.U. and M.G.; software, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva); validation, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva), F.P., M.C., M.C.P. and E.B.; formal analysis, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva), T.d.S. (Thiely da Silva) and R.C.; investigation, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva); resources, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva), M.C.P. and E.B.; data curation, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva); writing—original draft preparation, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva); writing—review and editing, T.d.S. (Thiély da Silva), R.C., R.R., G.M., L.M., B.U. and M.G.; visualization, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva); supervision, F.P., M.C., M.C.P. and E.B.; project administration, T.d.S. (Thais da Silva), F.P., M.C. and E.B.; funding acquisition, F.P., M.C., M.C.P. and E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant numbers #2023/08407-4, #2024/11092-8, and #2024/11035-4, and by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), processes 306576/2020-1, 404875/2023-8, 305357/2023-9, 304876/2020-8, and 307933/2021-0. This study was also financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to grants: #2023/08407-4, 2024/11092-8, and 2024/11035-4, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico), processes 306576/2020-1, 404875/2023-8, 305357/2023-9, 304876/2020-8 and 307933/2021-0. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES)-Finance Code 001. The authors also thank INPE (National Space Research Institute-Brazil) for FEG-SEM micrographs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC | Volumetric conductivity |

| BET | Brunauer, Emmet and Teller |

| BP | Buckypaper |

| CNT | Carbon nanotube |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| FEG-SEM | Field emission gun scanning microscopy |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared |

| GNP | Graphene nanoplatelets |

| IS | Impedance spectroscopy |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PEN | PAN electrospun nanofibers |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| USA | United States of America |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Di Benedetto, R.M.; Botelho, E.C.; Janotti, A.; Ancelotti, A.C., Jr.; Gomes, G.F. Development of an artificial neural network for predicting energy absorption capability of thermoplastic commingled composites. Compos. Struct. 2021, 257, 113131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.C.M.; Appezzato, F.C.; Costa, M.L.; Oliveira, P.C.; Botelho, E.C. The effect of the ocean water immersion and UV aging on the dynamic mechanical properties of the PPS/glass fiber composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2011, 30, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, E.C.; Nogueira, C.L.; Rezende, M.C. Monitoring of nylon 6,6/carbon fiber composites processing by X-ray diffraction and thermal analysis. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 86, 3114–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahuru, R.; Shaari, N.; Mohamed, M.A. Allotrope carbon materials in thermal interface materials and fuel cell applications: A review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2019, 44, 2471–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eatemadi, A.; Daraee, H.; Karimkhanloo, H.; Kouhi, M.; Zarghami, N.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Nanomedicine Research Group. Carbon nanotubes: Properties, synthesis, purification, and medical applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, D.; Yang, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Chirality pure carbon nanotubes: Growth, sorting, and characterization. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 2693–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Wei, F. Advances in production and applications of carbon nanotubes. In Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Preparations, Properties and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Handbook of Graphene: Graphene-like 2D Materials; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Alothman, Z.A.; Wabaidur, S.M. Application of carbon nanotubes in extraction and chromatographic analysis: A review. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelo-Pérez, L.M.; Herrera-Herrera, A.V.; Hernández-Borges, J.; Rodríguez-Delgado, M.Á. Carbon nanotubes: Solid-phase extraction. J. Chromatogr. A 2010, 1217, 2618–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, M.Z.; Nascimento, M.R.L.; Tormen, L.; Vieira, I.C.; Quináia, S.P. Avaliação de nanotubos de carbono funcionalizados visando o desenvolvimento de métodos de pré-concentração de íons metálicos e determinação por técnicas espectrométricas e eletroanalíticas. Quim. Nova 2020, 43, 1086–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.A.; Ardila-Rodríguez, L.A.; Diniz, M.F.; Gonçalves, M.; Ribeiro, B.; Rezende, M.C. Optimization of Triton X-100 removal and ultrasound probe parameters in the preparation of multiwalled carbon nanotube buckypaper. Mater. Des. 2019, 166, 107612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayan, P.M.; Schadler, L.S.; Giannaris, C.; Rubio, A. Single-walled carbon nanotube–polymer composites: Strength and weakness. Adv. Mater. 2000, 12, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Kausar, A.; Siddiq, M. A review on properties and fabrication techniques of polymer/carbon nanotube composites and polymer intercalated buckypapers. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2015, 54, 1524–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, G.T.; Park, Y.B.; Wang, S.; Liang, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Kramer, L. Mechanical and electrical properties of polycarbonate nanotube buckypaper composite sheets. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 325705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Guan, J.; Simard, B.; Gómez-Fatou, M.A. Poly(phenylene sulphide) and poly(ether ether ketone) composites reinforced with single-walled carbon nanotube buckypaper: II—Mechanical properties, electrical and thermal conductivity. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2012, 43, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Guan, J.; Simard, B.; Gómez-Fatou, M.A. Poly(phenylene sulphide) and poly(ether ether ketone) composites reinforced with single-walled carbon nanotube buckypaper: I—Structure, thermal stability, and crystallization behaviour. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2012, 43, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, S.; Ma, K.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, M. Tensile strain sensing of buckypaper and buckypaper composites. Mater. Des. 2015, 88, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaeri, M.M.; Ziaei-Rad, S.; Vahedi, A.; Karimzadeh, F. Mechanical modelling of carbon nanomaterials from nanotubes to buckypaper. Carbon 2010, 48, 3916–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, D. Influence of geometries of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the pore structures of Buckypaper. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2012, 43, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, H.; Liu, Y.; Leng, J. Self-sensing properties of smart composite based on embedded buckypaper layer. Struct. Health Monit. 2015, 14, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorabi, S.; Rajabi, L.; Madaeni, S.S.; Zinadini, S.; Derakhshan, A.A. Effects of three surfactant types of anionic, cationic and nonionic on tensile properties and fracture surface morphology of epoxy/MWCNT nanocomposites. Iran Polym. J. 2012, 21, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichiara, A.B.; Sherwood, T.J.; Benton-Smith, J.; Wilson, J.C.; Weinstein, S.J.; Rogers, R.E. Free-standing carbon nanotube/graphene hybrid papers as next generation adsorbents. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 6322–6327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patole, S.P.; Arif, M.F.; Susantyoko, R.A.; Almheiri, S.; Kumar, S. A wet-filtration-zipping approach for fabricating highly electroconductive and auxetic graphene/carbon nanotube hybrid buckypaper. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Sun, X. Free-standing graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid papers used as current collector and binder free anodes for lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2013, 237, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Gou, J. Study on 3-D high conductive graphene buckypaper for electrical actuation of shape memory polymer. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2012, 4, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Srivastava, S.K.; Pionteck, J.; Mittal, V. Mechanically and thermally enhanced multiwalled carbon nanotube–graphene hybrid filled thermoplastic polyurethane nanocomposites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2015, 300, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, T.T.; Pham-Huu, C.; Janowska, I.; Kim, T.; Castro, M.; Feller, J.F. Hybrid films of graphene and carbon nanotubes for high performance chemical and temperature sensing applications. Small 2015, 11, 3485–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punetha, V.D.; Rana, S.; Yoo, H.J.; Chaurasia, A.; McLeskey, J.T., Jr.; Ramasamy, M.S.; Cho, J.W. Functionalization of carbon nanomaterials for advanced polymer nanocomposites: A comparison study between CNT and graphene. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 67, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Anjos, E.G.; Moura, N.K.; Antonelli, E.; Baldan, M.R.; Gomes, N.A.S.; Braga, N.F.; Santos, A.P.; Rezende, M.C.; Pessan, L.A.; Passador, F.R. Role of adding carbon nanotubes in the electric and electromagnetic shielding behaviors of three different types of graphene in hybrid nanocomposites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2023, 36, 3209–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovtun, A.; Treossi, E.; Mirotta, N.; Scidà, A.; Liscio, A.; Christian, M.; Valorosi, F.; Boschi, A.; Young, R.J.; Galiotis, C.; et al. Benchmarking of graphene-based materials: Real commercial products versus ideal graphene. 2D Mater. 2019, 6, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, P.; Louw-Gaume, A.E.; Kucki, M.; Krug, H.F.; Kostarelos, K.; Fadeel, B.; Dawson, K.A.; Salvati, A.; Vázquez, E.; Ballerini, L.; et al. Classification framework for graphene-based materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7714–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Segundo, J.E.D.; Vilar, E.O. Grafeno: Uma revisão sobre propriedades, mecanismos de produção e potenciais aplicações em sistemas energéticos. Rev. Eletrônica Mater. Process. 2016, 11, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.N.R.; Biswas, K.; Subrahmanyam, K.S.; Govindaraj, A. Graphene, the new nanocarbon. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 2457–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.U.; Kausar, A.; Ullah, H.; Badshah, A.; Khan, W.U. A review of graphene oxide, graphene buckypaper, and polymer/graphene composites: Properties and fabrication techniques. J. Plast. Film Sheeting 2016, 32, 336–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C.; Kramer, L. Processing and property investigation of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNT) buckypaper/epoxy resin matrix nanocomposites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2004, 35, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Ruan, J.; Fan, Z.; Luo, G.; Wei, F. Preparation of a carbon nanotube film by ink-jet printing. Carbon 2007, 45, 2712–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.Y.; Kang, T.J.; Im, H.W.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, Y.H. Single-walled carbon-nanotube networks on large-area glass substrate by the dip-coating method. Small 2008, 4, 2255–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, W. In-situ curing of glass fiber reinforced polymer composites via resistive heating of carbon nanotube films. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 149, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbartoreh, A.R.; Wang, B.; Shen, X.; Wang, G. Advanced mechanical properties of graphene paper. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 109, 014306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Anjos, E.G.R.; Braga, N.F.; Ribeiro, B.; Escanio, C.A.; Cardoso, A.d.M.; Marini, J.; Antonelli, E.; Passador, F.R. Influence of blending protocol on the mechanical, rheological, and electromagnetic properties of PC/ABS/ABS-g-MAH blend-based MWCNT nanocomposites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, J.D.; Edie, D.D. Carbon-Carbon Materials and Composites; Noyes Publications: Park Ridge, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira Junior, M.S.; Manzolli Rodrigues, B.V.; Marcuzzo, J.S.; Guerrini, L.M.; Baldan, M.R.; Rezende, M.C. A statistical approach to evaluate the oxidative process of electrospun polyacrylonitrile ultrathin fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharlamova, M.V.; Kramberger, C. Electrochemistry of carbon materials: Progress in Raman spectroscopy, optical absorption spectroscopy, and applications. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavan, L.; Rapta, P.; Dunsch, L. In situ Raman and Vis-NIR spectroelectrochemistry at single-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 328, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, A.H.; Zarbin, A.J. Nanocompósitos entre nanotubos de carbono e nanopartículas de platina: Preparação, caracterização e aplicação em eletro-oxidação de álcoois. Quim. Nova 2014, 37, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, L.G.; Takai, K.; Enoki, T.; Endo, M.; Kim, Y.A.; Mizusaki, H.; Jorio, A.; Coelho, L.N.; Magalhães-Paniago, R.; Pimenta, M.A. General equation for the determination of the crystallite size La of nanographite by Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 163106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, L.G.; Jorio, A.; Ferreira, E.H.M.; Stavale, F.; Achete, C.A.; Capaz, R.B.; Moutinho, M.V.d.O.; Lombardo, A.; Kulmala, T.S.; Ferrari, A.C. Quantifying defects in graphene via Raman spectroscopy at different excitation energies. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3190–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, J.H.; Terrones, M.; Mansfield, E.; Hurst, K.E.; Meunier, V. Evaluating the characteristics of multiwall carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2011, 49, 2581–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S.; et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 187401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokobza, L.; Bruneel, J.-L.; Couzi, M. Raman spectroscopy as a tool for the analysis of carbon-based materials (highly oriented pyrolytic graphite, multilayer graphene and multiwall carbon nanotubes) and of some of their elastomeric composites. Vib. Spectrosc. 2014, 74, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, E.G.R. Desenvolvimento de Nanocompósitos Híbridos de GNP e MWCNT em Blendas de PC/ABS para Carcaça de Componentes Eletrônicos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yalovega, G.E.; Brzhezinskaya, M.; Dmitriev, V.O.; Shmatko, V.A.; Ershov, I.V.; Ulyankina, A.A.; Smirnova, N.V. Interfacial interaction in MeOx/MWNTs (Me–Cu, Ni) nanostructures as efficient electrode materials for high-performance supercapacitors. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djamila, B.; Eddine, L.S.; Abderrhmane, B.; Nassiba, A.; Barhoum, A. In vitro antioxidant activities of copper mixed oxide (CuO/Cu2O) nanoparticles produced from the leaves of Phoenix dactylifera L. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 14, 6567–6580. [Google Scholar]

- Um, J.G.; Jun, Y.S.; Elkamel, A.; Yu, A. Engineering investigation for the size effect of graphene oxide derived from graphene nanoplatelets in polyurethane composites. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Seidel, C.; Schulte, K. Preparation and characterization of graphite nanoplatelet (GNP)/epoxy nanocomposite: Mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 3878–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Singh, V.; Verma, H.S.; Bhatti, M. Microwave assisted synthesis and characterization of graphene nanoplatelets. Appl. Nanosci. 2016, 6, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Anjos, E.G.R.; Brazil, T.R.; de Melo Morgado, G.F.; Antonelli, E.; Medeiros, N.C.d.F.L.; Santos, A.P.; Indrusiak, T.; Baldan, M.R.; Rezende, M.C.; Pessan, L.A.; et al. Graphene related materials as effective additives for electrical and electromagnetic performance of epoxy nanocomposites. FlatChem 2023, 41, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waikar, M.R.; Sonker, R.K.; Gupta, S.; Chakarvarti, S.K.; Sonkawade, R.G. Post-γ-irradiation effects on structural, optical, and morphological properties of chemical vapor deposited MWCNTs. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 110, 104975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain, Q.T.; Haq, S.H.; Alshammari, A.; Al-Mutlaq, M.A.; Anjum, M.N. The systemic effect of PEG-nGO-induced oxidative stress in vivo in a rodent model. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prlainović, N.Z.; Bezbradica, D.I.; Knežević-Jugović, Z.D.; Stevanović, S.I.; Ivić, M.L.A.; Uskoković, P.S.; Mijin, D.Ž. Adsorption of lipase from Candida rugosa on multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, L.; Jiang, J. Hierarchical porous nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets derived from biomass waste for high-performance supercapacitor. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 192, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lu, L.; Wen, Y.; Xu, J.; Duan, X.; Zhang, L.; Hu, D.; Nie, T. Electrocatalytic oxidation of 4-chlorophenol at a novel poly-L-arginine modified glassy carbon electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 787, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Srivastava, S.K. Carbon nanostructures: Current practice and future prospects in electronics. Polym. Int. 2014, 63, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Dou, H.; Gao, B.; Yuan, C.; Yang, S.; Hao, L.; Shen, L.; Zhang, X. Facile synthesis of mesoporous MnCo2O4 nanowire arrays on Ni foam for high-performance supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 5115–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Hibino, H. Raman spectroscopy of epitaxial graphene on SiC: Influence of morphology and layer number. Carbon 2011, 49, 2264–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, E.B.; Son, H.; Samsonidze, G.G.; Souza Filho, A.G.; Saito, R.; Kim, Y.A.; Muramatsu, H.; Hayashi, T.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Raman spectroscopy of double-walled carbon nanotubes treated with H2SO4. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 2007, 76, 045425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetgin, S.H. Effect of multi walled carbon nanotube on mechanical, thermal and rheological properties of polypropylene. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 4725–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuda, K.; Kimura, H.; Murahashi, T. Evaporation and decomposition of Triton X-100 under various gases and temperatures. J. Mater. Sci. 1989, 24, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.; Edwards, I.A.S.; Menendez, R.; Rand, B.; West, S.; Hosty, A.J.; Kuo, K.; McEnaney, B.; Mays, T.; Johnson, D.J.; et al. Introduction to Carbon Science; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, G.R.; Rao, K.R. Carbon-carbon composites: An overview. Def. Sci. J. 1993, 43, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, E. Carbon-Carbon Composites; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.P.; Wang, J.N. Preparation of large-area double-walled carbon nanotube films and application as film heater. Phys. E 2009, 42, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayan, P.M.; Iijima, S. Capillarity-induced filling of carbon nanotubes. Nature 1993, 361, 333–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.M.; Banks, R.; Hamerton, I.; Watts, J.F. Characterisation of commercially CVD grown multi-walled carbon nanotubes for paint applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2016, 90, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweetman, L.J.; Alcock, L.J.; McArthur, J.D.; Stewart, E.M.; Triani, G.; in het Panhuis, M.; Ralph, S.F. Bacterial filtration usando carbon nanotube/antibiotic buckypaper membranes. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 781212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Mai, Y.-W. Influence of aspect ratio on barrier properties of polymer-clay nanocomposites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 088303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, D.; Wang, R.; Wu, L.; Guo, Y.; Ma, L.; Weng, Z.; Qi, J. Flame retardancy effects of graphene nanoplatelet/carbon nanotube hybrid membranes on carbon fiber reinforced epoxy composites. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 820901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chang, K.; Tien, H.; Lee, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.M.; Hu, C. Design and tailoring of a hierarchical graphene-carbon nanotube architecture for supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 2374–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Ramesh, P.; Sun, X.; Bekyarova, E.; Itkis, M.E.; Haddon, R.C. Enhanced thermal conductivity in a hybrid graphite nanoplatelet–carbon nanotube filler for epoxy composites. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4740–4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, W.; Schleussner, D. Field-emission characteristics of carbon buckypaper. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2003, 2, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Anjos, E.G.R.; Brazil, T.R.; de Melo Morgado, G.F.; Antonelli, E.; Rezende, M.C.; Pessan, L.A.; Moreira, F.K.V.; Marini, J.; Passador, F.R. Renewable PLA/PHBV blend-based graphene nanoplatelets and carbon nanotube hybrid nanocomposites for electromagnetic and electric-related applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 6165–6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Anjos, E.G.R.; Passador, F.R.; de Carvalho, A.B.; Rezende, M.C.; Sundararaj, U.; Pessan, L.A. Advanced ternary carbon-based hybrid nanocomposites for electromagnetic functional behavior in additive manufacturing. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 40, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).