Abstract

Wildland fires have become a major research subject among the national and international research community. Different simulation models have been developed to prevent this phenomenon. Nevertheless, fire propagation models are, until now, challenging due to the complexity of physics and chemistry, high computational requirements to solve physical models, and the difficulty defining the input parameters. Nevertheless, researchers have made immense progress in understanding wildland fire spread. This work reviews the state-of-the-art and lessons learned from the relevant literature to drive further advancement and provide the scientific community with a comprehensive summary of the main developments. The major findings or general research-based trends were related to the advancement of technology and computational resources, as well as advances in the physical interpretation of the acceleration of wildfires. Although wildfires result from the interaction between fundamental processes that govern the combustion at the solid- and gas-phase, the subsequent heat transfer and ignition of adjacent fuels are still not fully resolved at a large scale. However, there are some research gaps and emerging trends within this issue that should be given more attention in future investigations. Hence, in view of further improvements in wildfire modeling, increases in computational resources will allow upscaling of physical models, and technological advancements are being developed to provide near real-time predictive fire behavior modeling. Thus, the development of two-way coupled models with weather prediction and fire propagation models is the main direction of future work.

1. Introduction

Fire is a complex phenomenon, with dimensions of time and space that can vary on a scale from seconds and millimeters to over a day and over a kilometer. When it occurs in forests, fire can have a huge impact on humans as it puts lives and properties in danger. In particular, large-scale wildfires are responsible for economic losses, suppression costs, and natural resource losses and damages [1]. Portugal was the only country in the member states of the European Union with a decrease in forest area from 1990 to 2015. Forest fires are the reason behind this reduction, as Portugal is one of the countries most affected by this phenomenon. Forest fuel management and the forest in general are crucial to preventing forest fires that damage the ecosystem and release large amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere.

The simulation of wildfires remains a challenging and complex task because it involves both multi-physics and multi-scale. Wildfires can be described as a complex combination of highly chaotic chemical reactions and physical processes [2]. The transport of the energy released due to the chemical reactions occurs at scales ranging from a few tens of meters up to several kilometers as a flame zone that self-propagates into unburnt fuel. Advection, radiation, and transport of burning material are the phenomena involved in energy propagation [3]. Hence, due to the extremely complex phenomenon, its prediction is essential in decision-making for preventing and fighting a forest fire. An important parameter in wildfires is the rate of spread (ROS) which is a function of complex interactions between combustion, air flow, and atmospheric conditions. These interactions depend on the fuel (type, composition, and quantity), terrain (slope), and atmospheric conditions (mainly wind). The variability nature of these parameters complicates the task of accurately predicting the behavior and spread of wildfires.

According to Sullivan [4,5,6], there are three main categories of models for wildland fire spread behavior across the landscape: physical and quasi-physical models, empirical and quasi-empirical models, and simulation and mathematical analog models. From this perspective, models of a physical nature are based on the fundamental chemistry and physics of combustion and fire spread, while the quasi-physical model attempts to represent only the physics. In turn, an empirical model contains no physical source, and it is generally based only on a statistical nature. In contrast, a quasi-empirical model uses some form of physical framework upon which to base the statistical modeling chosen. Lastly, simulation models implement the preceding types of models in a simulation rather than a modeling context, while mathematical analog models utilize a mathematical percept to model the spread of wildland fire. Bakhshaii and Johnson [7], in a recent review, called these last two models a first-generation type of wildfire models. The authors also introduced the concept of a new generation of wildfire models that rely on the use of both physical and empirical fire models coupled with a numerical weather prediction model or computational fluid dynamic (CFD) model. However, despite all of the categories mentioned, it is possible in a simple way to classify the wildfire models into just two types in order to simulate the dynamic spatial fire spread across the landscape.

The first one is made of models based on CFD principles, which attempt to replicate fire behavior based on the fundamentals of fire, combustion, and heat transfer processes. CFD models are based on Navier–Stokes equations with auxiliary relationships for aspects such as chemical reactions, turbulence, and heat transfer. As a result, such models are less reliant upon extensive experimental relations for robustness. FIRETEC-HIGRAD model [8,9], developed at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, USA, is an example of a developed model based on the basic principles of CFD. This model consists of a coupled multiphase transport/wildland fire model based on mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations (HIGRAD [10,11,12]). This model is used to solve the equation of the local atmosphere motions, employing a fully compressible gas transport formulation in order to represent the coupled interactions of the combustion, fluid mechanics, and heat transfer involved in wildland fires across the landscape. The last phenomenon, wildfire propagation, is based on the FIRETEC fire model.

The second one encompasses perimeter propagation models, which apply empirical equations for the ROS, such as the Rothermel model [13], to simulate the fire perimeter’s propagation. Perimeter propagation models are used to simulate the large-scale propagation of fire across a landscape rather than directly solve the physics and chemical fundamentals that govern the fire. They can be based mainly on empirical relationships measured in the field or based on mathematical expressions. The fire perimeter in these models is the interface between burnt, burning, and unburnt regions and can be subdivided into front-tracking methods or cellular methods. In the front-tracking approach, the fire perimeter is described as a set of lines that expand according to a given rate of spread, and the point source for future propagation is each point on the fire perimeter. These models are considered computationally fast, although only one type of front shape is usually considered, elliptical. Models using this approach include, among others, Phoenix RapidFire [14], Prometheus [15], Aurora [16], and FARSITE [17]. In the cellular category methods, the domain is discretized into a grid over which all input data are prescribed, all calculations are performed, and empirical or physical formulas are used to update the state of the grid (e.g., according to wind direction, intensity and also the vegetation) over time. Examples of such models include, among others, FireStation [18] and FIREMAP [19]. Although cell-based simulators are simpler to implement, they are not widely used in comparison with front propagation models due to the fire shape distortion caused by the restriction of fire travel between adjacent cells [16].

Furthermore, there are two other models that play a major role in the assessment of wildfire data in the literature which are the mathematical models and the geographic information system (GIS). Mathematical models describe a system that makes use of language and mathematical concepts to describe a given phenomenon, such as the fire rate of spread. The importance of this type of model lies in the fact that they serve as a basis for developing various software programs that simulate the spread of fire in various configurations of terrain and environment, such as BEHAVE and FARSITE. The GIS model aims to store, display, and process spatial data. These data are stored in a grid structure (array) where each cell corresponds to a uniform parcel [19]. Then, these models are combined with mathematical models to compute the fire spread.

Although wildfire modeling has been reviewed in other publications, considering the current state-of-the-art and the authors’ knowledge, there has not been a review or bibliometric analysis of the works developed regarding this subject to guide interested researchers in developing simulations of fire propagation. Therefore, this work presents a review of the studies on the subject, focusing on the published work in the last two decades. For this, initially, an overview of wildfire modeling is given. Then, studies are described chronologically and analyzed bibliometrically through the software tool VOSviewer 1.6.18. Ultimately, the papers selected were divided into three main categories according to the main approach followed (centered on mathematical models, CFD models, or GIS).

In the following sections, the strategy and criteria to select studies for review are first established (Section 2); then, general numbers about the systematic review, such as the number of papers, journals, and research groups with more publications, are presented. In Section 3 and Section 4, details concerning the state-of-the-art in terms of methods used, as well as information about the input data, solution, and main research topics, are discussed. Finally, observations from this literature review are drawn, and a general perspective of further work is provided (Section 5).

2. Systematic Review

2.1. Methodology

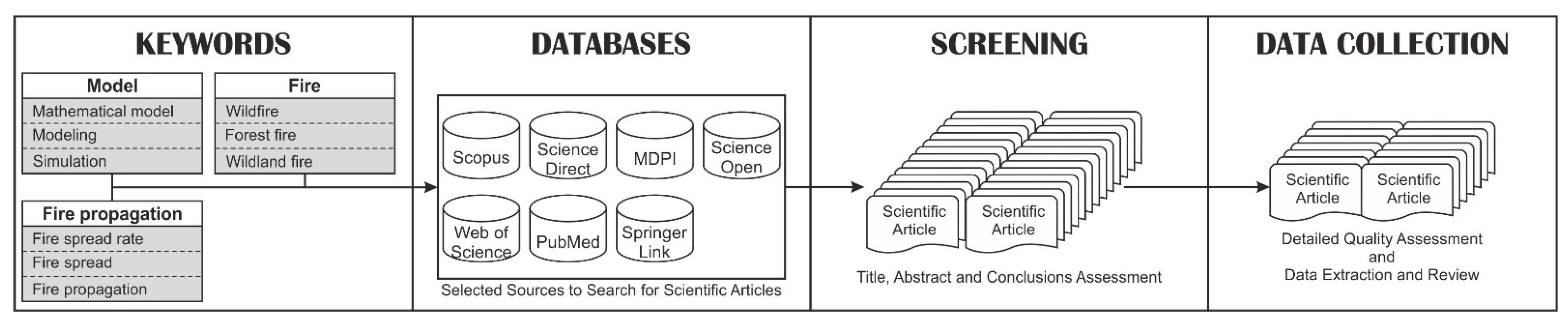

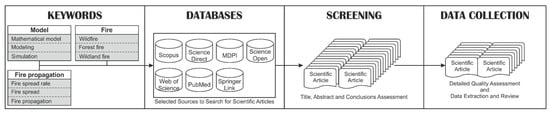

Considering the main guidelines of the PRISMA methodology [20], the strategy to conduct the present review was established. First, this systematic literature search was performed from papers published in the last two decades. The search for scientific papers was completed in the largest scientific databases of peer-reviewed literature such as Scopus, Science Direct, Web of Science, PubMed, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), Springer Link, and Science Open databases.

An advanced search using multiple keywords was carried out to find the most relevant papers. The documents were identified with advanced search query strings such as “(Fire spread rate OR Fire spread OR Fire propagation) AND (Wildfire OR Forest fire OR Wildland fire) AND (Mathematical model OR Modeling OR Simulation)”. The different keywords used were based on the various subjects that characterize the main research object. Next, the scientific papers were verified to see whether the authors could read the complete texts. The abstracts and conclusions were then read to screen out non-numerical studies or those that do not include fire spread (using a mathematical, GIS, or CFD model). Finally, data extraction and collection were completed to further analyze the information and draw some considerations and conclusions about the different aspects of the numerical models.

After carefully selecting the scientific papers, the information was organized in an Excel spreadsheet, from which duplicates were removed and the literature assessment was started. To perform the analysis in a more efficient, organized, and systematic way, the scientific papers were then listed in chronological order, and a summary of the papers in order to provide the authors with an overview of the studies and an idea of the evolution in this topic was completed.

Figure 1 presents the systematic research technique used in this work, according to PRISMA, and the details about the screening and selection process. After excluding duplicated papers and inadequate papers based on the abstract and conclusions reading, 59 full scientific papers were analyzed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review.

In addition, the selected papers were saved in Mendeley, a free reference manager software, and all the literature data were exported to VOSviewer 1.6.18 software for network analysis.

2.2. Overview of the Literature

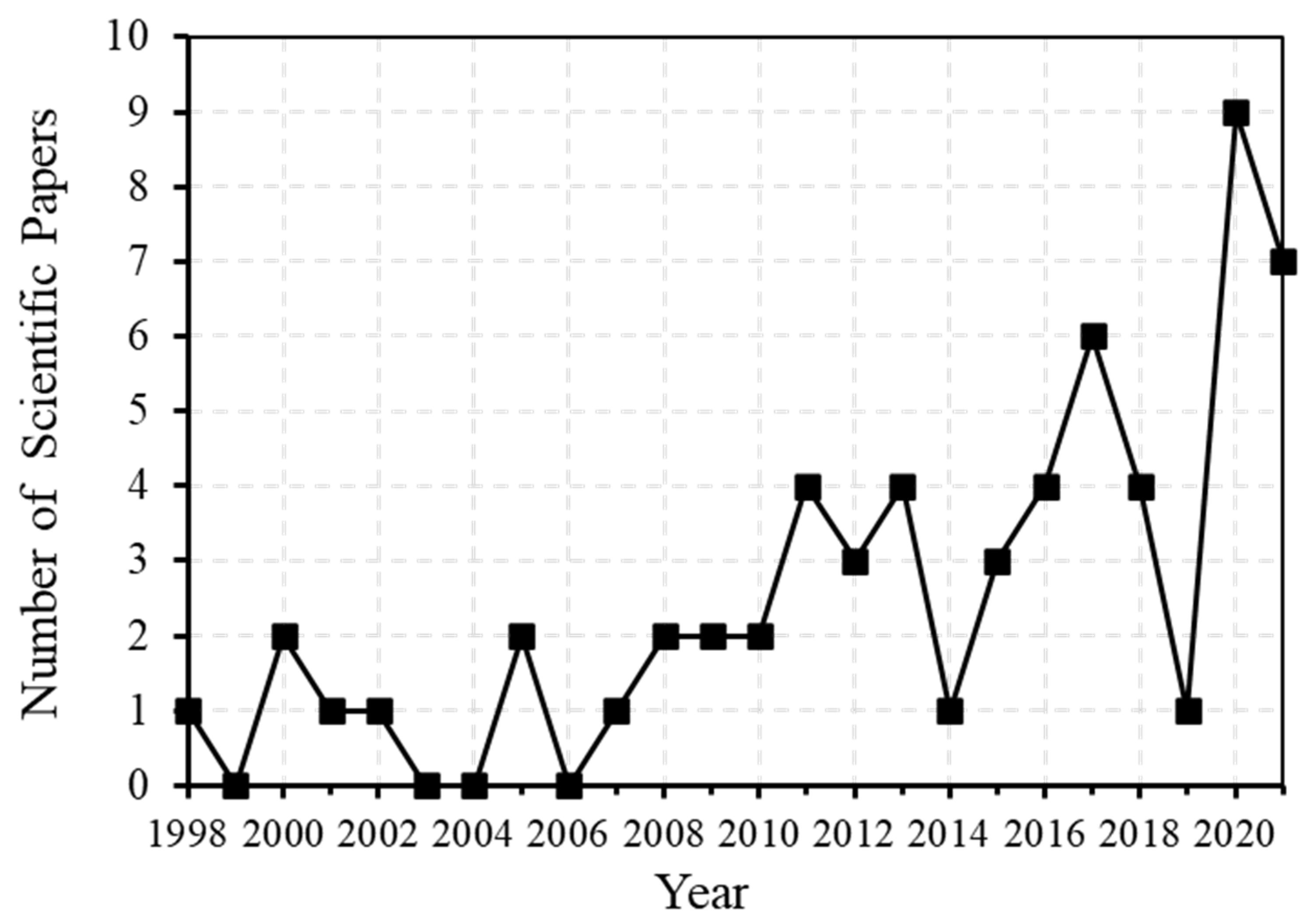

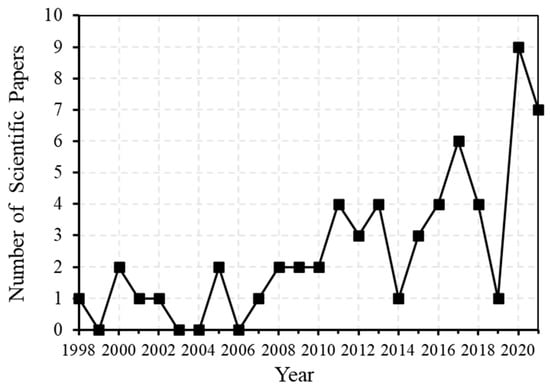

Figure 2 presents the number of publications identified by the year of publication, with a clear increase in the number since 1998. From this literature it was found that the most productive scientific journals were the International Journal of Wildland Fire and Environmental Modelling & Software, contributing to 40% of the published papers.

Figure 2.

Publications over time.

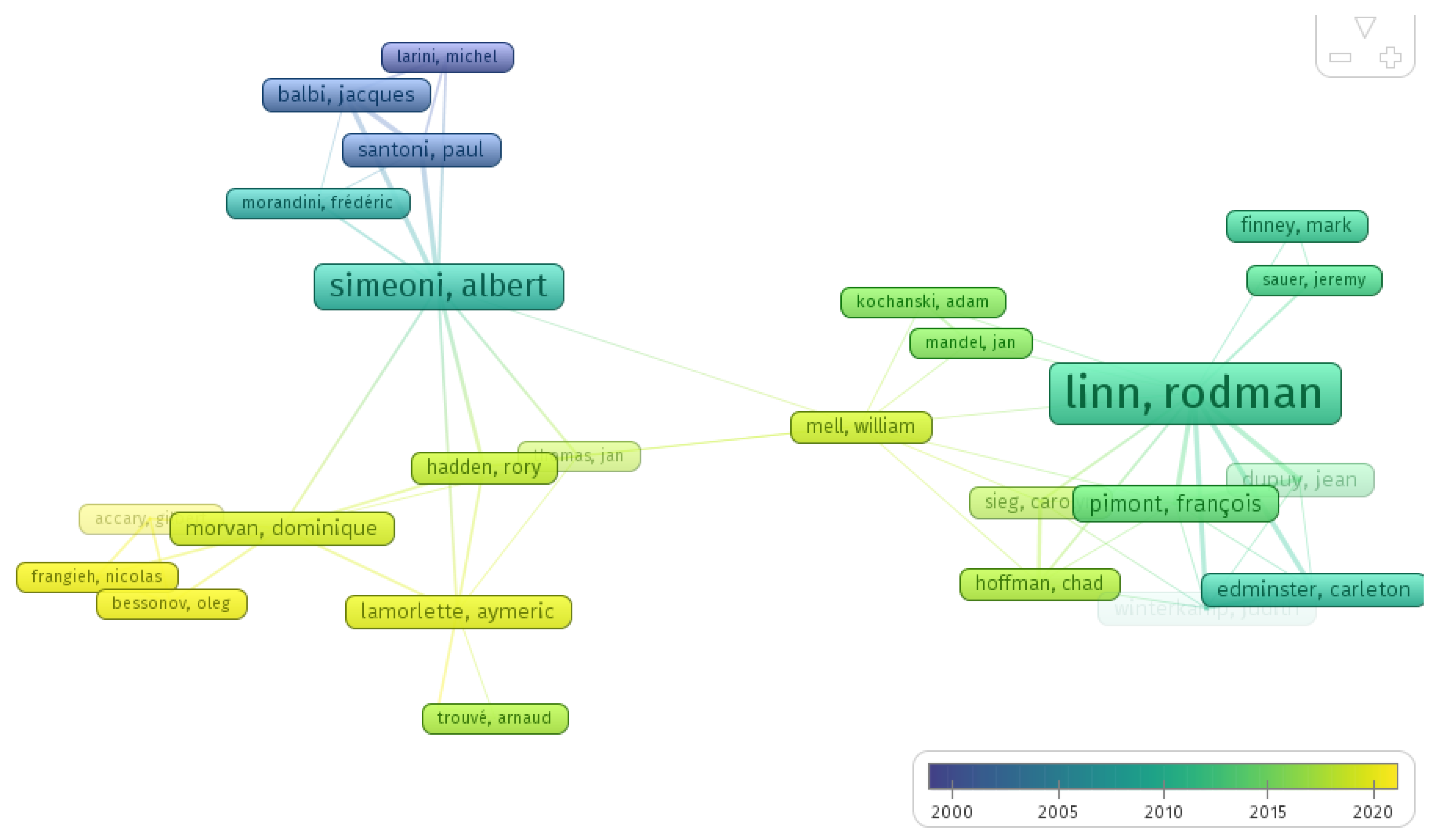

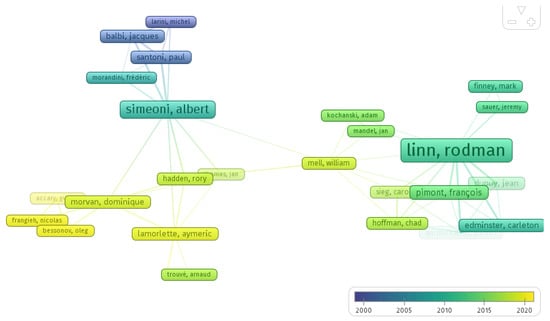

Figure 3 represents the network of different authors and their collaborations with other co-authors. The minimum number of documents is two. The lead to 25 authors being plotted in the graph out of 59. The authors with more publications, Albert Simeoni and Linn Rodman, represent two different research groups in the wildland fire modeling subject. Both authors are responsible for 16 and 9 publications, respectively.

Figure 3.

Network analysis diagram based on authors’ collaboration (output from VOSviewer).

After the bibliometric analysis, Table 1 was created with the five most cited papers about wildland fire modeling in order to present some insights of the most used literature. The most cited author was Linn in 2005 and Lopes in 2002, for their works employing CFD models with a total of 118 and 100 citations, respectively. Both works represent the early developments of wildland fire models.

Table 1.

The five most cited scientific papers about wildfire modeling.

3. General Trends from Modeling the Wildfire Behavior

3.1. Summary

The importance of advanced approaches to combat wildland fires is undeniably growing with ongoing climate change. These approaches, not excluding empirical knowledge and decisions based on experience, also use models, methods, and technology for managing and planning fire prevention. In this context, several approaches have been proposed. Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 present the current state-of-the-art of the papers selected, divided by type of model (numerical weather prediction models as WRF-SFIRE [22] are included in CFD category). It aims to provide an overall review of the key aspects, and main conclusions highlighted in each paper, and it also indicates if the work performed was validated.

The term spread model is generally understood as a physical–mathematical model composed of a system of equations whose solution results in numerical values capable of quantitatively predicting, in average space-time terms, some physical aspects of the natural behavior of all or a small fraction of a forest fire front, such as the rate of spread, flame height, ignition risk, or fuel consumption. This is all based on input information on the relevant parts of the forest and surrounding environment (vegetation, environmental, and terrain topography characteristics) [24,25].

There are several classifications of the mathematical modeling of forest fires depending on the elements considered by researchers in this field. In the literature on this topic, this classification is not only quite varied but, perhaps most importantly, not very consistent. Generally, the mathematical models of wildland fire can be classified according to the nature of the equations, subdivided into theoretical, empirical, and semi-empirical [24].

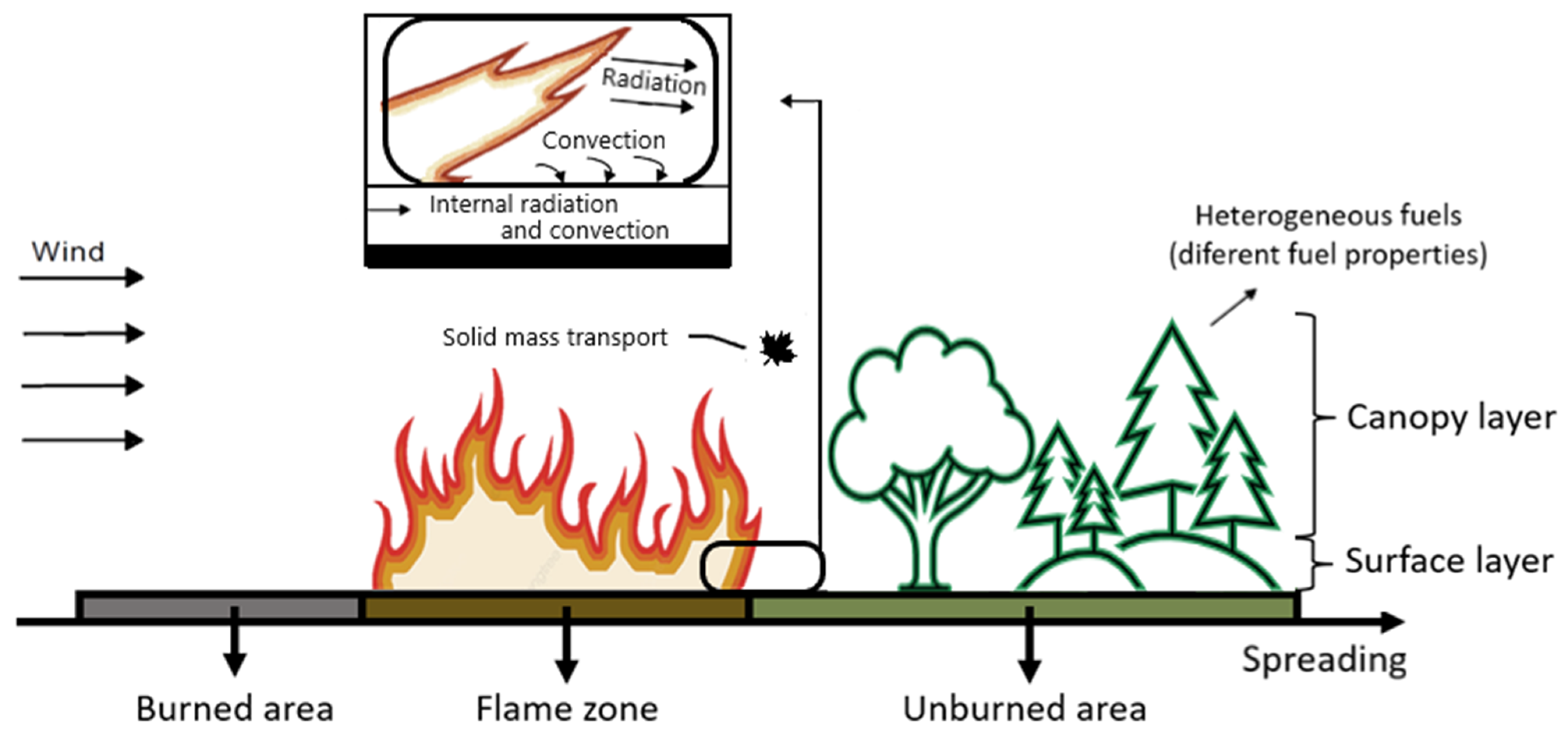

Figure 4 presents an overview of the approach used to develop the mathematical models, considering several different factors. Table 2 presents the most significant details of the mathematical papers reviewed.

Figure 4.

Simple approach of the mathematical models.

Table 2.

Details of the scientific papers presenting mathematical models.

Table 2.

Details of the scientific papers presenting mathematical models.

| Author | Key Aspects | Main Conclusions | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allaire et al., 2021 [26] | Provides a method to generate a probabilistic forecast of a burned area. | The calibrated ensembles lead to better overall accuracy. | Simulation |

| Aedo and Bonilla, 2021 [27] | Development of a numerical model to predict the loss of soil organic matter. | The soil water content controlled the heat consumed during vaporization and prevented soil decay. | Simulation |

| Jiang et al., 2021 [28] | Development of a fire spread model based on the heterogeneous cellular automata model. | The model can generate fire spread predictions with acceptable accuracy and short running time. | Simulation |

| Allaire et al., 2020 [29] | Prediction of surface fire spread and focus on the uncertainty. | Fire danger maps can be developed based on probabilistic fire simulations. | Simulation |

| Yuan et al., 2020 [30] | Development of parametric uncertainty analysis in an upslope fire spread model. | Values of ignition and flame temperatures have significant impacts on the predicted values of ROS under lower slopes. | Simulation |

| Rossa and Fernandes, 2018 [31] | Development of two empirical functions for ROS under windless conditions. | Both models confirm that independent variables are adequate descriptors of ROS. | Simulation |

| Rossa and Fernandes, 2018 [32] | Development of an empirical model for wind-aided ROS. | Laboratory evaluation showed improved predictions concerning the Rothermel model. | Experiments |

| Matthieu et al., 2017 [33] | Development of a fire spread model based on raster implementation. | The model can overpredict the spread rate of fire on the flanks. | Simulation |

| Hilton et al., 2015 [34] | Implementation of a wildfire spread model based on the level set method. | Local variation in combustion conditions slows the rate of propagation. | Simulation |

| Simeoni et al., 2015 [35] | Proposes an algorithm to accelerate the solution of the semi-physical model. | The accuracy of the results is not affected by this algorithm. | Experiments |

| Rochoux et al., 2013 [36] | Presentation of the potential benefits of data assimilation techniques. | Data assimilation has the potential to dramatically increase fire simulation accuracy. | Experiments and Observations |

| Simeoni et al., 2011 [37] | Study the fire spreading through a heterogeneous medium with a 2D reaction–diffusion physical model. | Combining different processes to create heterogeneity and improves the efficiency of heterogeneous zones to describe fire behavior. | Simulation |

| Mallet et al., 2009 [38] | Focus on a minimalist treatment of the fire front. | ROS depends on the wind speed and the angle between wind direction and the normal to the fire front. | Simulation |

| Johnston et al., 2008 [16] | Presentation of a cell-based wildfire simulator that uses an irregular grid. | Faster than traditional fire front propagation schemes. | Simulation |

| Morandini et al., 2005 [39] | Proposes a 2D nonstationary model of fire spreading across a fuel bed. | The model provided good results but should be tested in more realistic conditions. | Experiments |

| Simeoni et al., 2001 [40] | Study the advection effect on the fire spread across a fuel bed. | The knowledge of the gas velocity distribution proved to be essential to ROS. | Experiments |

| Simeoni et al., 2001 [41] | Improvement of semi-physical fire spread models based on the multiphase concept and a single equation. | Adding the advection term implies that the fire can theoretically spread faster than the wind. | Experiments |

The other approach that has grown in popularity over the past few decades is CFD modeling, with an established field in urban physics research, practice, and design due to its ability to provide details of the relevant flux variables in all the domains under well-controlled conditions [42]. CFD presents itself as a virtual fluid dynamics simulator characterized by the movement of the atmosphere and is a crucial tool in terms of numerical simulations [42,43]. CFD software can analyze a significant range of issues related to either laminar and turbulent flows, incompressible and compressible fluids, and multiphase flows, among others. The main issues are the computing power and accuracy of the results, which are associated with reduced computational time and efforts while improving product performance [44].

Table 3 presents the review carried out on the CFD papers. Most of those articles focused on a model’s capability to predict the fire rate of spread, which is shown to be influenced by several factors, including fuel bed characteristics, terrain slope, and wind speed [45,46,47]. Other studies, such as those using coupled fire/atmospheric numerical modeling techniques, study the factors that connect fire line length, geometry, and ROS from fires originated by line ignitions, to replicate the main flow patterns [48,49]. Fire behavior is also studied through the characterization of fire perimeter progression contours, fire regime transition and its associated heat transfer mechanisms, fire intensity, and fire-front shape, among several other parameters [43,50,51,52,53]. Due to the large quantities of modeling uncertainties that remain unquantified in the literature, mainly because of computing constraints or the amount of available data on adequate fuels, wind, and vegetation, a significant number of papers also focus on the modeling of these factors to account for possible errors [54,55,56,57].

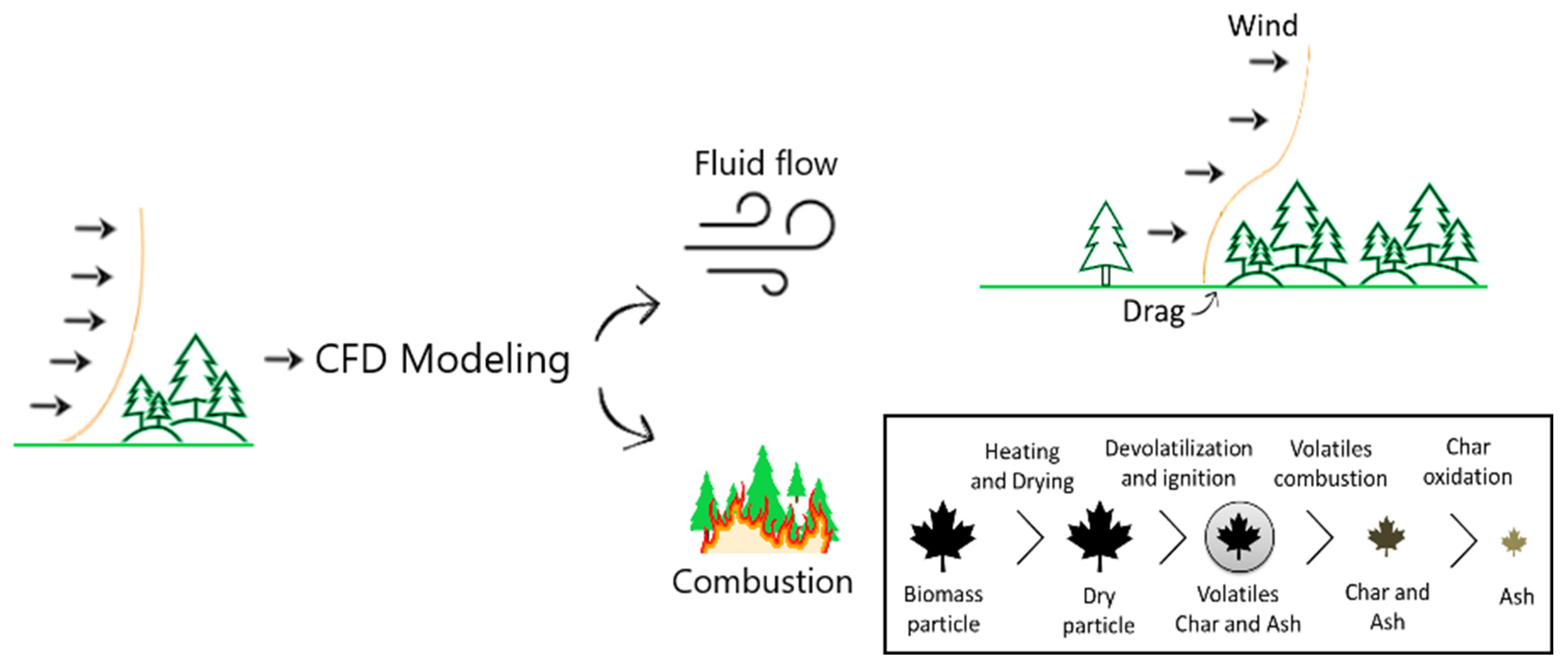

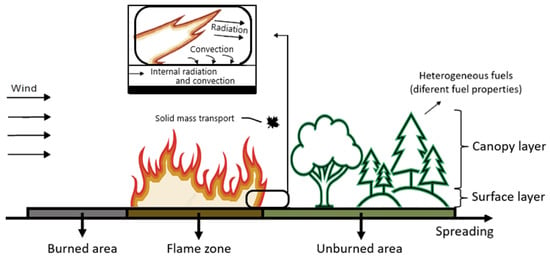

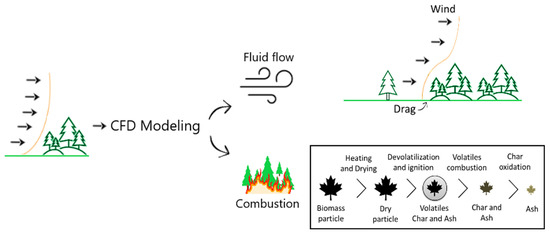

The flow drag caused by the presence of the forest and the combustion processes associated with fire are the two key challenges in wildfire modeling that have received increased attention. The analysis allowed us to conclude that these forest fire-related problems, shown in Figure 5, can be appropriately modeled using CFD techniques.

Figure 5.

Wildfire-related CFD modeling approach.

Table 3.

Details of the scientific papers presenting CFD models.

Table 3.

Details of the scientific papers presenting CFD models.

| Author | Key Aspects | Main Conclusions | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valero et al., 2021 [54] | Exploration of multi-fidelity approaches to fire spread prediction. | Fuel moisture, fuel load, and wind speed are the uncertainties responsible for most of the variation in fire rate of spread. | Experiments |

| Mueller et al., 2021 [56] | Considers the level of detail used to describe the environment and the predicted fire behavior. | Increasing the detail in canopy fuel structure and implementing turbulent boundary conditions at the domain had a minor impact. | Experiments |

| Atchley et al., 2021 [58] | Investigation of how fuel density fidelity and heterogeneity shape effective wind characteristics affect fire behavior. | Incorporating high-resolution fuel fidelity and heterogeneity information is crucial to capture effective wind conditions. | - |

| Zhang and Lamorlette, 2020 [57] | Considers the effect of vegetation characteristics on the flame tilt angle and the radiative heat transfer. | Predicts free and non-free fires, proposing a new tilt angle model and a new model for radiative heat power reaching the vegetation. | Simulation |

| Zhang et al., 2020 [50] | Investigate fire regime transition and its associated heat transfer mechanisms. | The new configuration is considered more suitable for investigating the fire regime transition. | Simulation |

| Linn et al., 2020 [43] | A new simulation tool to rapidly solve fire–atmospheric feedback. | Capability to capture basic trends in fire behavior, the response of fire spread to the size of the fire, and consumption of canopy fuels. | Compared with other models |

| Agranat and Perminov, 2020 [48] | A multiphase model is developed and incorporated into PHOENICS. | The predicted ROS agreed well with experimental values obtained at various wind speeds. | Experiments |

| Frangieh etal., 2020 [51] | Study of the 3D structure of a fire front propagating. | While in low wind speed, plumes rise and are not visibly affected by the action of crosswind, in stronger winds, they crossfire in front. | Experiments |

| Lopes et al., 2019 [52] | Two-way coupling method for fire behavior prediction. | Buoyancy-modified wind field should be considered as an input in fire prediction models. | Real fire data |

| Frangieh et al., 2018 [53] | A fully multiphase model that was developed can predict the fire ROS numerically. | Fire ignition can affect the shape of the fire front without significantly affecting ROS | Experiments |

| Chen et al., 2018 [59] | The model includes pyrolysis coupled with detailed chemistry combustion. | Enabled gas-phase fluid interactions, and combustion products/smoke formation, considering the radiation feedback on the solid fuel interface. | Experiments |

| Desmond et al., 2017 [60] | Replication of experiments in a wind tunnel. | Inclusion of forestry and buoyancy effects in CFD using sources and sink terms. | Experiments |

| Lopes et al., 2017 [45] | Describes an evolution of FireStation, incorporating a wind calculation module that considers feedback. | The two-way coupling importance decreases as the fire area gets larger. Update frequency influences the calculation time. | Simulation |

| Houssami et al., 2016 [61] | Presents a method for controlling the behavior of porous wildland fuels. | It was possible to reproduce the mass loss and temperatures that agree with the experiments. | Experiments and Simulation |

| Hoffman et al., 2015 [62] | Development of empirical relations between wind speed and crown fire. | Values from physics-based models fell within the 95% prediction interval of the empirical data. | Simulation |

| Canfield et al., 2014 [49] | Study of factors that connect fire line length, geometry, and ROS. | Increased ignition line length of simulated grass fires leads to increased ROS. | Simulation |

| Satoh et al., 2013 [63] | Study of the termination of fire whirls by means of aerial firefighting. | Fire extinguishment in the boundary is affected by the heat release rate of houses, wind speed, and location of a large structure. | Simulation |

| Linn et al., 2013 [64] | Exploration of fire/vegetation/atmosphere interactions. | Sparse fuels in heterogeneous woodlands can be overcome by decreasing fuel moisture content, moving dead canopy needles to the ground, increasing above-canopy wind speeds. | Simulation |

| Pimont et al., 2012 [46] | Discusses the effects of slope on ROS under different wind speeds. | Strong wind: the effect of the slope is relatively linear. Moderate wind: slope effect is between both. | Compared with other models |

| Linn et al., 2012 [55] | Exploration of changes in within-stand wind behavior and fire propagation associated with three time periods. | Averaging wind data affects ROS to varying degrees depending on the specific phase position of ignition with wind fluctuations. | Experiments |

| Koo et al., 2012 [65] | Several firebrand models are developed, and their transport trajectories are studied. | Firebrand trajectories without terminal velocity are larger than those from models with it. | - |

| Ghisu T. et al., 2011 [66] | Model for fire-front propagation based on a level-set methodology. | A simpler model to describe fire propagation in a landscape. | - |

| Mandel et al., 2011 [22] | Description of the physical model, numerical algorithms, and structure. | The model was able to support real runs, considering the level-set method. | Simulation |

| Dupuy et al., 2011 [67] | Discusses obstruction of ambient winds and existence of indraft flows downwind of a head fire (effects). | Flows are most favorable when a wildfire is driven downslope by a weak wind and backfire ignited at the bottom of the slope. | Experiments |

| Parsons et al., 2010 [68] | Investigation of the effect of spatial variability in crown fuels on the forward spread rate of fire. | Significant differences in ROS arose due to subtle fine-scale, dynamic interactions between the atmosphere, fuels, and fire. | Simulation |

| Linn et al., 2010 [47] | Analysis of different fuel beds on flat and upslope topography. | Fire acceleration when spread uphill; strong dependence of fireline thickness/ROS/perimeter shapes on fuel bed features. | Simulation |

| Endalew et al., 2009 [69] | Simulation of the airflow within model plant canopies. | Flow deviation around the trees is larger with increasing canopy density. | Wind tunnel measurements |

| Mochida et al., 2008 [21] | Assessment of the accuracy of the canopy models for CFD predictions. | Model coefficients were optimized according to field measurements. | Field measurements |

| Linn et al., 2005 [9] | Investigation of aspects of fire behavior in grasslands. | ROS depends on wind, shape, and fire size. Lateral ROS depends on wind and fire line length. | Experiments/empirical models |

| Linn and Cunningham, 2005 [70] | Exploration of several fundamental aspects of fire behavior. | The spread of fire increases with wind speed and depends on the initial length of the fire line. | Simulation and Experiments |

| Lopes et al., 2002 [18] | Software for simulation of fire spread over complex topography. | Realistic simulations can be used in planning fire suppression operations. | Historical data |

| Reisner et al., 2000 [11] | Presentation of a numerical technique to improve a wildfire model. | Stable and accurate technique for solving fundamental equations. | Simulation |

| Reisner et al., 1998 [10] | Presentation of a numerical model using a combined approach. | A modeling system is a useful tool for determining wildfire propagation. | Experiments |

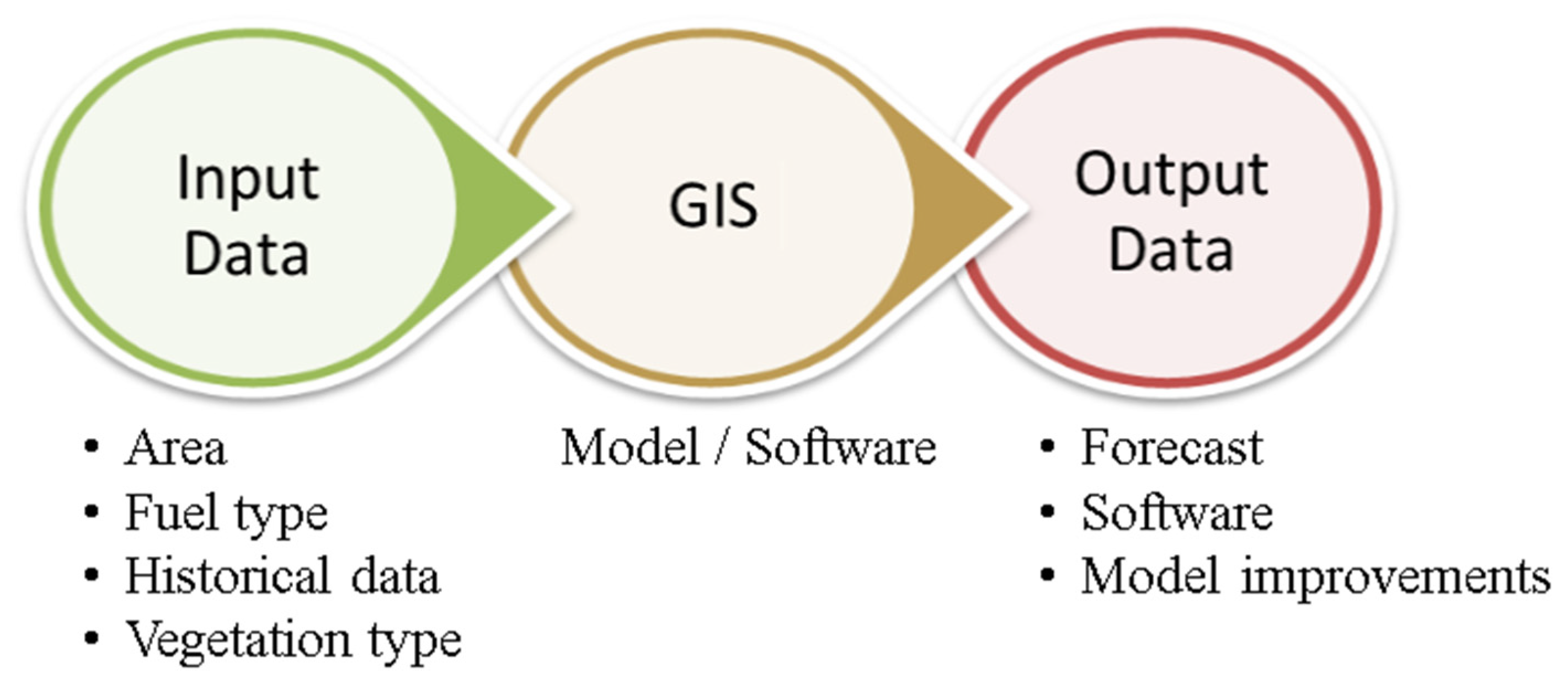

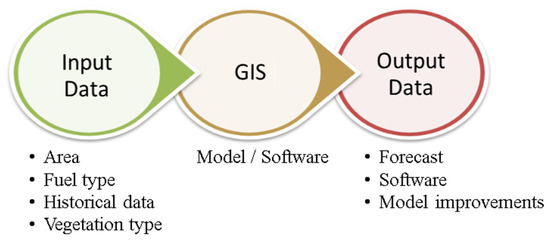

Alongside with the developments and studies regarding CFD and mathematical models, GIS models were also analyzed. The group of scientific papers selected reinforces the importance of visualization when the objective is to provide insights into the communities and bring the study of wildfires and the real world closer [71]. The rise of technology is a great ally when dealing with wildfires promoting the specific development of databases such as LANDFIRE or even new models/software (MEDFire, Firemap, FireStation, FuelManager). Wildland fires are a truly complex phenomenon to study, and the complexity of the models developed in these papers reinforces the need to collect data for further analysis [23].

Figure 6 presents the main sequence of a GIS process, which highlights the importance of the input data for the model to be as refined as possible. That refinement will lead to better forecast/output data.

Figure 6.

Main flowchart of GIS process.

Table 4.

Details of the scientific papers that present GIS models.

Table 4.

Details of the scientific papers that present GIS models.

| Author | Key Aspects | Main Conclusions | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oliveira et al., 2021 [72] | Development of a monthly fire spread probability model based on historical data. | The probability of fire spread highly correlates with historical data. | Historical data |

| Salis et al., 2021 [73] | Application of wildfire simulation modeling to analyze wildfire exposure and risk transmission in Sardinia | The main findings can be used to further evaluate expected wildfire behavior or transmission potential. | Historical data |

| Crawl et al., 2017 [71] | Presentation of a web platform, Firemap, its architecture, and main components for geospatial data services and fire prediction. | Based on the interactions, Firemap proved to be a helpful tool in the firefighter community. | - |

| Valero et al., 2017 [74] | Presentation of a two-fold methodology to couple automated wildfire monitoring with accurate fire spread forecasting. | Automatically detects the location of the fire perimeter and emits a reliable forecast of its future evolution. | Experiments |

| Monedero et al., 2017 [75] | Proposes different algorithms to deal with fire behavior analysis using a final perimeter as an input. | The backward time method provides good results and is easy to implement and solve quickly. | - |

| Herráez et al., 2016 [76] | Discussion of the integration of two models into a GIS-based interface. | The tool developed is efficient and fully operational. | Historical data |

| Duane et al., 2016 [77] | Presentation of a model that evaluates the weights of five landscape factors in fire spread performance. | Separation of fires according to synoptic weather situations can improve fire modeling in landscape fire models. | Historical data |

| Kevin et al., 2013 [23] | The origin of LANDFIRE and the use of its data are outlined. | LANDFIRE provides the means to game the landscape to design cost-effective treatment alternatives. | - |

| Vasconcelos et al., 1992 [19] | Description of concepts behind FIREMAP and comparison with a real fire occurrence. | A potentially useful tool that goes beyond the display of spatial information. | Historical data |

3.2. Input Data

The main input parameters for each type of model selected will be highlighted in this section, varying according to the model’s requirements.

3.2.1. Mathematical Model

To retain the most relevant information from the set of mathematical model documents, Table 5 was created to identify the software and models used for the fire simulations, some of the most important input parameters, and the respective outputs of each work. It is important to mention that Table 5 only contemplates the articles with the relevant input data for this section. The second column of Table 5 shows the software used, and the models considered by the authors. This analysis reveals that a number of software tools, including FlamMap, are available in the literature to assist in investigating this subject. It is also essential to highlight the Rothermel model, which is implemented in various software programs and is used as a tool for comparing outcomes in several studies [13].

Table 5.

Details of the scientific papers using mathematical models.

The next three columns on Table 5 represent the three main characteristics considered in the assessment of the different models: type of fuel used, terrain configuration, and wind velocity. Regarding the type of fuel used, it has been verified that in most of the laboratory tests, pine fuel is used (as pine needles), followed by fuel beds of grass, branches, litter, and other types of vegetation (used or contemplate from historical fire data). In the terrain configuration, the main factor considered is slope: some tests are performed without any type of slope, i.e., flat terrain, and in other cases, with slope conditions (either upslope or downslope). Regarding wind speed, values are usually arbitrated or selected employing field measurements or literature data. In wind tunnel tests, wind opposing the fire direction was also contemplated. However, not all of the authors considered wind as a factor.

The last column refers to the outputs of each study, where the main objective is to determine the fire ROS. In addition to calculating the ROS, some papers also present the amount of burned area, fire perimeter, fire front evolution, and heat and gas fluxes.

Other critical input data, such as meteorological conditions (ambient temperature and relative humidity) and vegetation characteristics (physical dimensions, fuel particle density, humidity, moisture content, the surface to volume ratio, etc.), were reviewed and the values considered are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Essential inputs in mathematical models.

3.2.2. CFD Model

To present the input data of the CFD scientific papers, Table 7 was developed. The input data were separated into seven columns to easily identify each parameter studied in the different studies.

Table 7.

Details of the CFD scientific papers.

The second column on Table 7 presents the domain scale: small (all dimensions are less than 100 m), medium (between 100 m and 1 km), or large (larger than 1 km). The third column highlights the software/model information. The HIGRAD/FIRETEC model was common in the earliest studies. However, other models and programs were later employed, including the ANSYS Fluent and CFX, Phoenics, NIST FDS-4 software, and the software system FireStation, which incorporates a surface fire spread model and a solver for the fluid flow (Navier–Stokes) equations [45]. Additionally, the wildland–urban interface fire dynamics simulator (WFDS), an extension of the fire dynamics simulator (FDS), is used. In this model, compared with FIRETEC, the physics of combustion is computed in a different way. WFDS assumes that combustion occurs solely by mixing fuel gas and oxygen and is independent of temperature. Another interesting model used in the literature was WRF-FIRE which is a combination of the weather research and forecasting model (WRF) and a fire code (FIRE) based on semi-empirical equations to compute the rate of spread of the fire line. This model is essentially a reimplementation of the coupled atmosphere–wildland fire-environment (CAWFE) model. However, a new implementation of a fire model based on the level set method resulted in a new version of WRF-FIRE called WRF-SFIRE.

The fourth column identifies the turbulence models applied. There is a definite trend toward using two models, Large Eddy Simulation (LES) and the Reynolds averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) k-ε model. RANS models only simulate average turbulent characteristics and mean fields, while LES captures transient motions of the wind resolving turbulent structures [64]

For five through seven columns (combustion mechanism, combustion model, and vegetation representation), the checklist method was used to keep a simple and easy-to-read table. For the combustion mechanism, a single-step reaction was adopted in the majority of recent works. For the combustion models, the Eddy dissipation concept model was frequently employed. A rectangular homogeneous subdomain was used for the vegetation representation, considering a series of parameters such as moisture content, types of vegetation, and fuel dept.

The last column contains the initial conditions presented in each paper, which are typically the initial wind speed values, boundary conditions, ignition source, and velocity inlet profile, usually described as a log-law type of function.

3.2.3. GIS Model

In recent years, forest fires have had an increasingly negative impact on both the environment and mankind. With this issue in mind, research is also improving in accuracy and sophistication [74]. The intricacy of a wildfire can be studied using GIS, enabling the construction of integrated information systems for future combinations with other environmental models to produce improved visualizations and forecasts for fire and forest management [76].

For a better understanding of the crucial aspects regarding the reviewed GIS scientific papers that were selected, Table 8 was created, collecting the main input data. The first column contains the model’s scale, to understand the range of the model. The second column indicates the software/model used as a basis for GIS.

Table 8.

Details of the GIS scientific papers.

Another important consideration when discussing GIS is the type of data used to validate the models considered in each paper, which is presented in the third column and can range from historical data to real fire data. The fourth column displays some of the main vegetation characteristics considered in the GIS papers: fuel type, moisture content, and vegetation height. All of these parameters play a crucial role in developing a GIS model. The fifth column of Table 8 specifies the weather conditions that each paper evolved from. Weather conditions establish a significant relation within the different models to analyze the fire spread. Lastly, the final column presents the output that each paper provided, indicating if it is a new software/model or another output that increases the knowledge base surrounding GIS.

4. Research Topics Examined in the Selected Studies

Some topics were highlighted during the review of the selected papers and are presented in this section: flow, vegetation, and combustion. Given the nature of each model, some present more details on a specific topic than others.

4.1. Air Flow

In some mathematical models, the authors only consider natural convection [27,61]. According to [30], the convection coefficient of the flame-induced convective cooling is a function of the Reynolds number, which is dependent on factors including the local flow velocity, the air viscosity, and the typical fuel particle diameter.

In laboratory tests that typically involve the use of wind tunnels, the flow is simulated inside the wind tunnel itself and may fluctuate depending on the fluid’s changing properties. These tests enable the investigation of the influence of the slope as well as the distribution of the fluid’s velocity profile, all of which are thought to be necessary to accurately characterize propagation rates [40]. Two experiments are discussed by [39]: the first was conducted for the horizontal spread of fire by still air, and the second was conducted at the Instituto Superior Técnico for the horizontal spread of wind over an inclined surface.

Other studies adopted the multiphase approach, which consists in solving conservation equations (mass, momentum, and energy) averaged in a control volume at an adequate scale that contains a gas phase flowing through a solid phase while considering the strong coupling between the two phases [35,41]. Due to the sample’s exposure to induced air, which can either cool or heat the solid phase, convection’s influence is not dominant but can be higher on top of the sample than inside it when there is only natural convection [61].

FIRETEC and WFDS are two distinct physics-based modeling strategies that [62] described in detail. The turbulence model used in FIRETEC employs transport equations for turbulent kinetic energy at a number of specified length scales along with an approximation known as the Boussinesq to estimate the Reynolds stresses related to these length scales. The energy equation in WFDS is presented in terms of enthalpy rather than potential temperature, in contrast to FIRETEC. With WFDS’s low Mach number approximation, thermally-driven flow is possible without being constrained by completely compressible models’ small-time step restrictions.

For the CFD articles, one of the most common approaches is the method of solving the flow field through the RANS equations coupled with the k-ɛ turbulence model. This approach has been used successfully to model atmospheric flows over complex terrains [52]. Wildfire flows are turbulent, therefore a set of rules to properly model the turbulence associated needs to be considered. When compared to linear models, CFD is expected to significantly improve the accuracy of airflow and turbulence predictions in complex terrains, particularly in cases of flow separation or when thermal effects become significant [79]. Regarding the wind flow field, it can be solved using a steady state approach, for instance [45], and simulations have shown that flows are most favorable when the wildfire is driven downslope by a weak wind and the backfire is ignited at the bottom of the slope [67].

According to [50] and studies based on 3D considerations, forest fire propagation through vegetation can experiences two types of flow behaviors, an atmosphere boundary layer flow which changes to a mixing layer flow. They occur behind (on the burnt vegetation layer, described by the log-law wind profile) and in front of the flame front (on unburnt vegetation). Hence, the flow over forest canopies has a variety of unique properties that set it apart from other atmospheric boundary layer flows. To properly understand its effect, is necessary to understand how a simple flat terrain affects the wind characteristics [79].

Several authors also reported that the presence of an obstruction, such as forests, causes the flow to deviate around the trees. This effect is larger with the increasing canopy density [69]. This effect, the drag caused by the trees, can be accounted for by the introduction of source and sink terms in the momentum and turbulent energy equations or by variation of the roughness length parameter, accounted for in the velocity inlet profile. Inside the forest, the airflow is significantly less when compared to the undisturbed wind, and its variation depends on the amount and distribution of vegetation. Turbulence is also induced at the interface between the high canopy trees and the freestream flow [80].

As for the GIS-reviewed papers, the flow effect is not considered a primary topic. However, the models are constructed using the approach used in CFD models, such as CANYON, a 3D Navier–Stokes solver [18].

4.2. Vegetation

As previously mentioned, mathematical models can perform two types of experimental tests—those conducted in laboratories and those conducted in the field. Because of this, the fuel type (vegetation) employed in these studies may be either homogeneous or heterogeneous and, as a result, may have various properties (moisture content, fuel depth, fuel load, surface–volume ratio, heat content, and particle density).

In several cases, the laboratory tests use fuel beds composed of pine needles (Pinus pinaster and Pinus ponderosa), grass, sticks, and litter layers [36,38,40]. In the literature, some tests performed with these types of fuel beds vary from 1 to 1.5 m wide and 1 to 8 m long, always depending on the authors’ decision based on previous works [31,32].

On the other hand, testing conducted in the open field can be carried out in places where topographical characteristics (slope and orientation) and atmospheric characteristics (wind speed and direction, relative humidity, and ambient temperature) can change. For instance, in [36], a validation test of the model was performed outside on a small patch of flat, horizontal grass with 4 m by 4 m dimensions. The grass’ uniform thickness would be 8 cm, its moisture content would be 22%, and its reported wind speed would be 1.3 m/s.

To determine whether the ROS calculated is close to that recorded in reality, simulations can also be performed using data from actual fires that have already occurred using the appropriate software (FIRETEC, WFDS, and SWIFFT). For this, it is necessary to introduce as input parameters characteristic data of the region where the fire occurred [62]. Matthieu et al. [33] use vegetation data from three different fires that occurred: one in Australia (themeda grass), one in Thailand (deciduous forest fuel mix), and the last one in a Mediterranean area (live strawberry and foliage mix).

When analyzing the burning behavior of wildland fuels, the role of the vegetation parameter in CFD modeling and other types of modeling must be taken into account due to the extremely complex heat and mass transfer problems caused by the many physical parameters that are associated with it, such as vegetation properties, topography, and the environmental conditions [57]. When the vegetation effect is taken into account, several factors are typically considered, including fuel height (m), fuel density (kg/m3), fuel load (kg/m2), moisture content (%), fuel depth (m), fuel volume fraction, surface-to-volume ratio (1/m), among others [56,67].

In the literature review of the CFD papers, the most common types of vegetation were grass, pine trees/leaves, dead pine needles, jack pine, black spruce, short chaparral, ponderosa pine forests, apple, and cherry orchard.

Many studies have been conducted to establish an adequate way to represent this element of terrain complexity, forestry, which has already been identified as requiring special attention in CFD simulations. This element exerts a considerable drag force on the wind, inducing turbulence and altering local temperature and heat flux profiles [60]. Some models, such as FIRETEC, represent vegetation as a porous medium providing bulk momentum and heat exchange between gas and solid phases [70]. Most of the studies represent vegetation through a rectangular porous sub-domain. Some include both forestry and buoyancy effects by adding source and sink terms in the governing equations [49,61,70]. Others have attempted to add more detail to the canopy fuel structure by including the 3D architecture of the canopies in the model [56], but it was shown that increasing the detail in the canopy fuel structure and implementing turbulent boundary conditions in the domain had a minor impact. Therefore, it is possible to include both forest and buoyancy effects in the numerical simulations by using source and sink terms, achieving satisfactory convergence. Desmond et al. [60] have described two sets of source and sink terms for vegetation modeling.

Regarding GIS models, vegetation research has a significant impact on them. When analyzing wildland fire behavior, the distribution of fuels is frequently identified as a crucial factor [58]. Weather, topography, and fuel all play a role in how quickly a fire spreads, though the precise contributions of each are still unclear [77]. Canopy heterogeneity will increase the spatial and temporal variation of the wind, corresponding to an intermittent sweeping of fast-moving air down the canopy and the ejection of slow-moving air upward out of the canopy [58].

Although most of the time, the fuel classification was lacking in terms of quality, fire potential is increased, and losses are caused by fire by climate-driven vegetation stress and unfavorable fire weather [23]. Fuel loads directly impact the intensity and spread of fires, and vegetation indices obtained from remote sensing imagery can be used to determine the proportion of fuel loads on a regional scale [72]. After a significant wildfire incident, fuel loads can recover completely in some locations in just 2.43 years [72]. It was also possible to confirm the significance of modeling post-fire vegetation dynamics in order to obtain an estimate of greenhouse gas emissions.

4.3. Combustion

In mathematical models, the term combustion is automatically linked to other processes, such as ignition and heat transfer (through three different mechanisms: radiation, convection, and conduction). Numerous authors use the fictitious concept of ignition temperature, which is not a physical property of fuel, when discussing ignition in order to simplify the complex nature of combustion chemistry. However, there is no consensus in the literature regarding the values of ignition temperatures for wildland fuels [30]. According to [35], the combustion reaction is assumed to take place above a threshold temperature. Above this temperature, the fuel mass is considered to decline exponentially, and the amount of heat produced per unit of fuel mass is constant.

The physical properties of the fuel bed, such as the surface area per unit mass of fuel, which provides a measure of how simple ignition is and how quickly combustion occurs, are more likely to explain significant changes in the combustion process: high exposed area enhances flame-to-fuel heat transfer and low mass makes temperatures rise faster. As fuel particles become more tightly packed, combustion should be delayed by a lack of oxygen [31].

According to a model called SWIFFT described by [33], the combustion process is driven by unsteady energy conservation within the fuel stratum and detailed heat transfer mechanisms, including radiation from the flaming zone and embers, surface and internal convection, and radiation loss.

As for the ROS, it depends on the combustion process and on a number of complex interactions involving pyrolysis, flow, and atmospheric dynamics, according to [36].

In the last ten years, combustion models have gained more and more attention in the field of CFD modeling. As shown in Table 7, the Eddy dissipation concept (EDC) combustion model is the most frequently used model for the turbulence–chemistry interaction [49,51,52,54,57,58], with some exceptions such as the use of the strained laminar flamelet combustion model [59].

While some authors model combustion through a single-step mixing controlled chemical reaction [51,55,56], others used Arrhenius-type kinetics for the heterogeneous reactions [48,56].

Most CFD papers used a burner to inject CO from the bottom boundary into the computational domain to represent the key process of wildland fire. This gas phase reaction was driven by competition between the CO–air turbulence and molecular diffusion rates [50,57]. The burner can be activated along an ignition line for a predetermined period or until it has burned through an amount of fuel equal to the available amount above the burning region.

Linn et al. [55] used a reaction rate formulation for the combustion process based on a limited mixing assumption. This depends on the relative density of the solid fuel and oxygen, the turbulent diffusion rate, the stoichiometry of the fuel and oxygen, and a probability distribution function for the temperature within a resolved grid volume. The same author stated in another publication that moisture content is one of the fuel characteristics that most affects ignition; the lower it is, the easier the particles ignite, as expected [64].

The widely used FIRETEC model describes the set of chemical reactions in a wildland fire as one solid-gas reaction, which involves wood reacting with oxygen to produce heat and inert gases [9]. In contrast, if a simplified model is considered, the focus is essentially on the release of CO2 and CO. Hence, one reaction representing the oxidation of CO and a second reaction corresponding to the dissociation of the CO2 are fundamental for combustion modeling. This is in line with the work of Urbanski [81], who set out to record emission factor data by geographical zones (tropical, temperate, and boreal) and vegetation types (forest/savanna and grassland). The author stated that the highest emissions were recorded for CO2 and CO, followed by PM2.5 and CH4.

When discussing combustion, the Rothermel model addresses fire spread, and the development of GIS research is highly correlated [19,21,76,78]. Weather, topography, and fuel are additional factors that affect fire spread [77]. The preference for the Rothermel model is due to the high adaptability to any prospective fuel complex [18].

Other papers consider the fire spread probability model to be a simple Bayesian probability [72]. This probability spread model made it possible to develop several conclusions, one of which is that the locations with the highest fire frequencies are not always those with the largest fuel loads.

5. Final Remarks

The increasing problems caused by wildfires worldwide have been receiving special attention from the scientific community. Wildland fire modeling research is a multidisciplinary topic that is largely related to combustion science. The importance of this subject has rapidly increased in the last few years mainly due to the importance of creating prevention strategies and promoting management strategies, supporting operational decision-making, and assessing the effectiveness of different procedures on fire behavior and propagation. These objectives were only possible by taking into account crucial interactions in wildland fires, such as the interaction of fire with vegetation and weather on temporal and spatial scales. This work addresses 59 papers about wildfire modeling published in the last two decades, particularly 17 concerning mathematical models, 33 CFD models, and 9 GIS models. The most important remarks resulting from this work are:

- A representative sample of wildfire modeling works and a reproducible investigation containing a representative number of relevant scientific papers were achieved. Nonetheless, some works not containing the exact keywords or the words not being contained in the databases are intentionally not included. The sample was considered representative of the current state-of-the-art of the main topic and comprehensive enough.

- Research over the past two decades has grown significantly and enhanced the mechanisms of wildfire and the primary influence of different parameters such as weather, topography, and fuel in the fire rate of spread. These advances improved the efficacy of wildfire predictions and the understanding of the phenomenon. Nevertheless, there is still consensus on the physical interpretation of the acceleration of wildfires, but complete knowledge of the mechanisms leading to its ignition and propagation are far from fully understood. Most of the works applied empirical models such as the Rothermel model, which only applies to situations where the environment and vegetative conditions are identical to those used for the study.

- Additionally, some CFD models developed for wildland fire studies require evaluation against relevant and equivalent experimental data to the simulated scenario. For this reason, this is why, these models are still considered as research tools among the scientific community. These were the main limitations found during the review.

Regarding the key aspects and lessons learned in this review, observed trends and topics are related to the development of two-way coupled CFD models with weather prediction models and modules containing the capability to represent the fire spread and heat release. This aspect is of great importance since there is a strong interaction between the atmosphere and fire, and this dependency is important to be considered in the wildfire simulation. Some important aspects related to this subject:

- Sophisticated CFD models are still time consuming, even if executed on parallel supercomputers, and they need improvements regarding the interconnection between the fluid flow prediction and the vegetation consumption and combustion [56].

- Due to the fast development of technology and advances in computational power, GIS models seem to be effective for wildfire modeling tools due to the spatial nature of the fire spread and the easy integration of submodels, such as fire and wind models, and the ease of acquiring data and displaying the outputs.

- GIS models are being developed to provide near real-time predictive fire behavior modeling, making these tools useful for the different people involved in fire management, control, and suppression. Consequently, a model that is simple, intuitive, user-friendly, and accessible to a wide range of operators that might not be familiar with the different models is provided.

Investigations in the field of wildfire modeling should certainly not stop here, and more research is necessary. Scientists and the people involved in fire protection and suppression need ways to assess fire behavior and prediction. With the developments and advances in computing speed, storage, and graphical capabilities, it is expected that better wildland fire prediction systems will be developed in the next few years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S., J.T. and S.T.; methodology, J.S., J.M., I.G. and R.B.; investigation, J.S., J.M., I.G. and R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S., J.M., I.G., R.B., J.T. and S.T.; writing—review and editing, J.S., J.T., S.T. and F.A.; supervision, J.T., S.T. and F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) within the R&D Units Project Scope UIDB/00319/2020 (ALGORITMI) and R&D Units Project Scope UIDP/04077/2020 (METRICS) and through project: PCIF/GRF/0141/2019: “O3F—An Optimization Framework to reduce Forest Fire”.

Acknowledgments

The first author would like to express his gratitude for the support given by the FCT through the PhD Grant SFRH/BD/130588/2017. Inês Gonçalves and João Marques would like to also express their acknowledgment of the support given by the FCT through the project: PCIF/GRF/0141/2019: “O3F—An Optimization Framework to reduce Forest Fire”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| CAWFE | Coupled Atmosphere–Wildland Fire-Environment |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamic |

| EDC | Eddy Dissipation Concept |

| FDS | Fire Dynamics Simulator |

| FIRE | Fire code |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GWR | Geographically Weight Regression |

| HDWM | High-Definition Wind Model |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PhFFS | Physical Forest Fire Spread |

| RANS | Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes |

| ROS | Fire Rate of Spread |

| WFDS | Wildland–urban interface Fire Dynamics Simulator |

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting model |

References

- Liu, N.; Lei, J.; Gao, W.; Chen, H.; Xie, X. Combustion dynamics of large-scale wildfires. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2021, 38, 157–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.L. Inside the Inferno: Fundamental Processes of Wildland Fire Behaviour Part 1: Combustion Chemistry and Heat Release. Fire Sci. Manag. 2017, 3, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.L. Inside the Inferno: Fundamental Processes of Wildland Fire Behaviour Part 2: Heat Transfer and Interactions. Fire Sci. Manag. 2017, 3, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A. Wildland surface fire spread modelling, 1990–2007. 1: Physical and quasi-physical models. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.L. Wildland surface fire spread modelling, 1990–2007. 2: Empirical and quasi-empirical models. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A. Wildland surface fire spread modelling, 1990–2007. 3: Simulation and mathematical analogue models. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshaii, A.; Johnson, E.A. A review of a new generation of wildfire–atmosphere modeling. Can. J. For. Res. 2019, 49, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, R. A Transport Model for Prediction of Wildfire Behavior; Los Alamos National Lab.: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Linn, R.; Cunningham, P. Numerical simulations of grass fires using a coupled atmosphere-fire model: Basic fire behavior and dependence on wind speed. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2005, 110, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, J.; Bossert, J.; Winterkamp, J. Numerical Simulations of Two Wildfire Events Using a Combined Modeling System (HIGRAD/BEHAVE); No. LA-UR-97-4036; CONF-980121; Los Alamos National Lab.: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner, J.; Wynne, S.; Margolin, L.; Linn, R. Coupled atmospheric-fire modeling employing the method of averages. Mon. Weather Rev. 2000, 128, 3683–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, J.; Knoll, D.; Mousseau, V.; Linn, R. New numerical approaches for coupled atmosphere-fire models. In Proceedings of the Third Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, 9 January 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rothermel, R. A Mathematical Model for Predicting Fire Spread in Wildland Fuels; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1972; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Tolhurst, K.; Shields, B.; Chong, D. Phoenix: Development and Application of a Bushfire Risk Management Tool. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2008, 23, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tymstra, C.; Bryce, R.W.; Wotton, B.M.; Taylor, S.W.; Armitage, O.B. Development and Structure of Prometheus: The Canadian Wildland Fire Growth Simulation Model; Natural Resources Canada: Edmonton, AL, Canada, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, P.; Kelso, J.; Milne, G. Efficient simulation of wildfire spread on an irregular grid. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, M. FARSITE: Fire Area Simulator-Model Development and Evaluation; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, A.M.G.; Cruz, M.G.; Viegas, D.X. FireStation—An integrated software system for the numerical simulation of fire spread on complex topography. Environ. Model. Softw. 2002, 17, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.; Guertin, P. FIREMAP-Simulation of Fire Growth With a Geographic Information System. Int. J. Wildland Fire 1992, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochida, A.; Tabata, Y.; Iwata, T.; Yoshino, H. Examining tree canopy models for CFD prediction of wind environment at pedestrian level. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2008, 96, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, J.; Beezley, J.; Kochanski, A. Coupled atmosphere-wildland fire modeling with WRF 3.3 and SFIRE 2011. Geosci. Model Dev. 2011, 4, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.; Opperman, T. LANDFIRE-A national vegetation/fuels data base for use in fuels treatment, restoration, and suppression planning. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, E.; Zárate, L.; Planas, E.; Arnaldos, J. Mathematical models and calculation systems for the study of wildland fire behaviour. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2003, 29, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, J.; Viegas, D. Modelos de Propagação de Fogos Florestais: Estado-da-Arte para Utilizadores Parte II: Modelos Globais e Sistemas Informáticos. Silva Lusit. 2002, 9, 237–265. [Google Scholar]

- Allaire, F.; Mallet, V.; Filippi, J.B. Novel method for a posteriori uncertainty quantification in wildland fire spread simulation. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 90, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aedo, S.; Bonilla, C. A numerical model for linking soil organic matter decay and wildfire severity. Ecol. Modell. 2021, 447, 109506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, F.; Fang, L.; Zheng, X.; Qiao, X.; Li, Z.; Meng, Q. Modelling of wildland-urban interface fire spread with the heterogeneous cellular automata model. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 135, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaire, F.; Filippi, J.; Mallet, V. Generation and evaluation of an ensemble of wildland fire simulations. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2020, 29, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Liu, N.; Xie, X.; Viegas, D. Physical model of wildland fire spread: Parametric uncertainty analysis. Combust. Flame 2020, 217, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossa, C.; Fernandes, P. Empirical modeling of fire spread rate in no-wind and no-slope conditions. For. Sci. 2018, 64, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossa, C.; Fernandes, P. An empirical model for the effect of wind on fire spread rate. Fire 2018, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gennaro, M.; Billaud, Y.; Pizzo, Y.; Garivait, S.; Loraud, J.; El Hajj, M.; Porterie, B. Real-time wildland fire spread modeling using tabulated flame properties. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 91, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J.; Miller, C.; Sullivan, A.; Rucinski, C. Effects of spatial and temporal variation in environmental conditions on simulation of wildfire spread. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 67, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, A.; Santoni, P.; Balbi, J. A strategy to elaborate forest fire spread models for management tools including a computer time-saving algorithm. Int. J. Model. Simul. 2002, 22, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rochoux, M.; Delmotte, B.; Cuenot, B.; Ricci, S.; Trouvé, A. Regional-scale simulations of wildland fire spread informed by real-time flame front observations. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013, 34, 2641–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, A.; Salinesi, P.; Morandini, F. Physical modelling of forest fire spreading through heterogeneous fuel beds. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2011, 20, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, V.; Keyes, D.; Fendell, F. Modeling wildland fire propagation with level set methods. Comput. Math. Appl. 2009, 57, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandini, F.; Simeoni, A.; Santoni, P.; Balbi, J. A model for the spread of fire across a fuel bed incorporating the effects of wind and slope. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2005, 177, 1381–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, A.; Santoni, P.; Larini, M.; Balbi, J. On the wind advection influence on the fire spread across a fuel bed: Modelling by a semi-physical approach and testing with experiments. Fire Saf. J. 2001, 36, 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeoni, A.; Santoni, P.; Larini, M.; Balbi, J. Proposal for theoretical improvement of semi-physical forest fire spread models thanks to a multiphase approach: Application to a fire spread model across a fuel bed. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2001, 162, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B. Computational Fluid Dynamics for urban physics: Importance, scales, possibilities, limitations and ten tips and tricks towards accurate and reliable simulations. Build. Environ. 2015, 91, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, R.; Goodrick, S.; Brambilla, S.; Brown, M.; Middleton, R.; O’Brien, J.; Hiers, J. QUIC-fire: A fast-running simulation tool for prescribed fire planning. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 125, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccolieri, R.; Santiago, J.L.; Rivas, E.; Sanchez, B. Review on urban tree modelling in CFD simulations: Aerodynamic, deposition and thermal effects. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Ribeiro, L.; Viegas, D.; Raposo, J. Effect of two-way coupling on the calculation of forest fire spread: Model development. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2017, 26, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimont, F.; Dupuy, J.; Linn, R. Coupled slope and wind effects on fire spread with influences of fire size: A numerical study using FIRETEC. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, R.; Winterkamp, J.; Weise, D.; Edminster, C. A numerical study of slope and fuel structure effects on coupled wildfire behaviour. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2010, 19, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agranat, V.; Perminov, V. Mathematical modeling of wildland fire initiation and spread. Environ. Model. Softw. 2020, 125, 104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, J.; Linn, R.; Sauer, J.; Finney, M.; Forthofer, J. A numerical investigation of the interplay between fireline length, geometry, and rate of spread. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 189–190, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Verma, S.; Trouvé, A.; Lamorlette, A. A study of the canopy effect on fire regime transition using an objectively defined Byram convective number. Fire Saf. J. 2020, 112, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangieh, N.; Accary, G.; Morvan, D.; Méradji, S.; Bessonov, O. Wildfires front dynamics: 3D structures and intensity at small and large scales. Combust. Flame 2020, 211, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Ribeiro, L.; Viegas, D.; Raposo, J. Simulation of forest fire spread using a two-way coupling algorithm and its application to a real wildfire. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2019, 193, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangieh, N.; Morvan, D.; Meradji, S.; Accary, G.; Bessonov, O. Numerical simulation of grassland fires behavior using an implicit physical multiphase model. Fire Saf. J. 2018, 102, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, M.; Jofre, L.; Torres, R. Multifidelity prediction in wildfire spread simulation: Modeling, uncertainty quantification and sensitivity analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 141, 105050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, R.; Anderson, K.; Winterkamp, J.; Brooks, A.; Wotton, M.; Dupuy, J.; Pimont, F.; Edminster, C. Incorporating field wind data into FIRETEC simulations of the International Crown Fire Modeling Experiment (ICFME): Preliminary lessons learned. Can. J. For. Res. 2012, 42, 879–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.; Skowronski, N.; Clark, K.; Gallagher, M.; Mell, W.; Simeoni, A.; Hadden, R. Detailed physical modeling of wildland fire dynamics at field scale-An experimentally informed evaluation. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 120, 103051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lamorlette, A. An extensive numerical study of the burning dynamics of wildland fuel using proposed configuration space. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 160, 120174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, A.; Linn, R.; Jonko, A.; Hoffman, C.; Hyman, J.; Pimont, F.; Sieg, C.; Middleton, R. Effects of fuel spatial distribution on wildland fire behaviour. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2021, 30, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yuen, A.; Wang, C.; Yeoh, G.; Timchenko, V.; Cheung, S.; Chan, Q.; Yang, W. Predicting the fire spread rate of a sloped pine needle board utilizing pyrolysis modelling with detailed gas-phase combustion. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 125, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, C.; Watson, S.; Hancock, P. Modelling the wind energy resources in complex terrain and atmospheres. Numerical simulation and wind tunnel investigation of non-neutral forest canopy flows. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2017, 166, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssami, M.; Thomas, J.; Lamorlette, A.; Morvan, D.; Chaos, M.; Hadden, R.; Simeoni, A. Experimental and numerical studies characterizing the burning dynamics of wildland fuels. Combust. Flame 2016, 168, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, C.; Mell, W.; Sieg, C.; Pimont, F. Evaluating Crown Fire Rate of Spread Predictions from Physics-Based Models. Fire Technol. 2016, 52, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, K.; Liu, N.; Zhou, K.; Xie, X. CFD study of termination of fire whirls in urban fires. Procedia Eng. 2013, 62, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, R.; Sieg, C.; Hoffman, C.; Winterkamp, J.; McMillin, J. Modeling wind fields and fire propagation following bark beetle outbreaks in spatially-heterogeneous pinyon-juniper woodland fuel complexes. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 173, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, E.; Linn, R.; Pagni, P.; Edminster, C. Modelling firebrand transport in wildfires using HIGRAD/FIRETEC. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2012, 21, 396–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisu, T.; Arca, B.; Pellizzaro, G.; Duce, P. An application of the level-set method to fire front propagation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Fire Behaviour and Risk, Alghero, Italy, 4–6 October 2011; pp. 227–228. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, J.; Linn, R.; Konovalov, V.; Pimont, F.; Vega, J. Exploring three-dimensional coupled fireatmosphere interactions downwind of wind-driven surface fires and their influence on backfires using the HIGRAD-FIRETEC model. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2011, 20, 734–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.; Sauer, J.; Linn, R. Crown Fuel Spatial Variability and Predictability of Fire Spread. In Proceedings of the VI International Conference on Forest Fire Research, Coimbra, Portugal, 15–18 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Endalew, A.; Hertog, M.; Gebrehiwot, G.; Baelmans, M.; Ramon, H.; Nicolaï, B.; Verboven, P. Modelling airflow within model plant canopies using an integrated approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2009, 66, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, R.; Winterkamp, J.; Colman, J.; Edminster, C.; Bailey, J. Modeling interactions between fire and atmosphere in discrete element fuel beds. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2005, 14, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawl, D.; Block, J.; Lin, K.; Altintas, I. Firemap: A Dynamic Data-Driven Predictive Wildfire Firemap: Data-Driven Predictive Firemap: A Dynamic Dynamic Data-Driven Environment Predictive Wildfire Wildfire Modeling and Visualization Firemap: Dynamic Predictive Wildfire Modeling a. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 108, 2230–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, U.; Soares-Filho, B.; Costa, W.; Gomes, L.; Bustamante, M.; Miranda, H. Modeling fuel loads dynamics and fire spread probability in the Brazilian Cerrado. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 482, 118889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, M.; Arca, B.; Del Giudice, L.; Palaiologou, P.; Alcasena-Urdiroz, F.; Ager, A.; Fiori, M.; Pellizzaro, G.; Scarpa, C.; Schirru, M.; et al. Application of simulation modeling for wildfire exposure and transmission assessment in Sardinia, Italy. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 58, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, M.; Rios, O.; Mata, C.; Pastor, E.; Planas, E. An integrated approach for tactical monitoring and data-driven spread forecasting of wildfires. Fire Saf. J. 2017, 91, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monedero, S.; Ramirez, J.; Molina-Terrén, D.; Cardil, A. Simulating wildfires backwards in time from the final fire perimeter in point-functional fire models. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 92, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herráez, P.; Sevilla, A.; Canals, F.; Cascón, M.; Rodríguez, M. A GIS-based fire spread simulator integrating a simplified physical wildland fire model and a wind field model. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 2142–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, A.; Aquilué, N.; Gil-Tena, A.; Brotons, L. Integrating fire spread patterns in fire modelling at landscape scale. Environ. Model. Softw. 2016, 86, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, M.A. Fire growth using minimum travel time methods. Can. J. For. Res. 2002, 32, 1420–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridis, A. Modelling of Wind Turbine Wakes in Complex Terrain Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Master’s Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cedell, P. Forest Simulation with Industrial CFD Codes; KTH Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Urbanski, S.P.; Hao, W.M.; Baker, S. Chapter 4 Chemical Composition of Wildland Fire Emissions. Dev. Environ. Sci. 2008, 8, 79–107. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |