Abstract

Small-scale two-phase flows are subject to intense capillary accelerations that must be treated with care in order to avoid artifacts often associated with the numerical methodologies used, such as excessive fragmentation of structures. This analysis proposes a formulation of capillary actions for compressible viscous two-phase flows within the framework of discrete mechanics, where the concept of mass is abandoned in favor of a law of motion that describes the conservation of accelerations, one related to inertia and the other to external actions. With the introduction of the capillary term, the sum of a capillary potential gradient and the dual curl of a vector potential is consistent with the other terms of the law of motion, a formal Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition. This fully compressible formulation reproduces the capillary waves generated by the source terms and the contact and shock discontinuities in the two immiscible fluids. This methodology completely eliminates parasitic currents due mainly to the presence of residual curl in the capillary source terms. Several classic examples demonstrate the validity of this approach.

1. Introduction

Numerical simulation of two-phase flows in the presence of interfaces poses specific problems when spatial scales are comparable to capillary length. The most traditional method is interface capture, which can be achieved using Eulerian techniques where the interface crosses fixed volumes, or Lagrangian methods where the mesh is modified according to the evolution of the free surface. Numerous methods have been developed to capture the shape of the interface in a fixed mesh, the best known of which is certainly the Volume Of Fluid method, which consists of defining the volume fraction of one of the two phases in the mesh [1,2]. Another formulation, the Level-Set method, implicitly represents the interface through the evolution of the solution of a differential equation [3,4,5]. Small-scale capillary effects are generally taken into account by integrating source terms into the law of motion; the most widely used physical model is probably Brackbill’s [6], based on volume fraction, which allows both the curvature of the interface to be calculated and the pressure jump effects on either side of the interface to be defined. Each of these methods has advantages and disadvantages that are well documented in the journals cited. Two-phase flows are largely represented by Navier–Stokes equations in their compressible or incompressible formulations. Mass conservation is always ensured by an adjoint equation, the continuity equation, whose variable is density, with the relationship between pressure and density being ensured by a state law; in the case of compressible two-phase flow, it is therefore necessary to define a state law for each phase.

The proposed approach differs significantly from traditional formulations used to model and simulate two-phase flows. It is based on a law of motion that reflects the conservation of acceleration [7]. According to the theory of special relativity, Einstein’s principle establishes the equivalence between mass and energy; since acceleration is already energy per unit of mass and length, mass is a redundant quantity in the law of motion and, moreover, in other equations of mechanics. The concept of momentum, the product of mass or density and velocity, itself contains this distinctive feature. In reality, Galileo’s weak equivalence principle (WEP), derived from his observations on the universal fall of bodies, is a local law, strictly independent of the concept of mass. The interpretation of discrete mechanics, which differs from that initially adopted, from that used in the theory of relativity, and from that still in use today, is based on the observation of this experiment: bodies fall at the same velocity and with the same acceleration, regardless of their nature and mass. This experiment can only be interpreted on the basis of kinematics. Acceleration, energy per unit of mass and length, is the only quantity considered absolute here and constitutes the founding principle of the discrete formulation. The discrete law of motion derived from this principle of conservation of acceleration allows us to find solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations without the presence of density. The equation obtained reflects Helmholtz–Hodge’s decomposition of acceleration into a sum of two terms, a first component curl-free and a second divergence-free. All terms of the equation, including capillary source terms [8], are written according to this same principle, which confers particular properties on the law of motion [9].

This discrete formulation is extended here to compressible two-phase flows where each phase has different physical characteristics, particularly compressibility; capillary waves and waves related to compressibility, surface discontinuity, and shock waves are thus closely linked. After presenting the derivation of the law of motion, the definitions of characteristics related to capillary effects, in particular for surface tension, are redefined by the absence of the concept of density in the formulation. An in-depth analysis of the interactions between capillary effects and compressibility effects is performed based on the velocities of capillary waves and compressibility waves relative to the viscous effects that are always present in both phases. Classic examples of two-phase flows in the presence of capillary acceleration include (i) the oscillatory motion of an initially elliptical drop, already studied in the case of incompressible motion [10], and (ii) the capillary equilibrium of an interface between a liquid and a gas between two vertical planes. In the latter case, Jurin’s law, which concerns the average height of the meniscus, is supplemented by a second law concerning the rotation-shear equilibrium. Only the addition of this second law allows static equilibrium and a strictly zero velocity around the meniscus to be obtained. Finally, the case of shock waves generated by the integration of capillary terms is treated specifically, at very small time scales, in the case of a cylindrical drop subjected to instantaneous acceleration.

2. Discrete Mechanics Framework

2.1. Geometric Structures

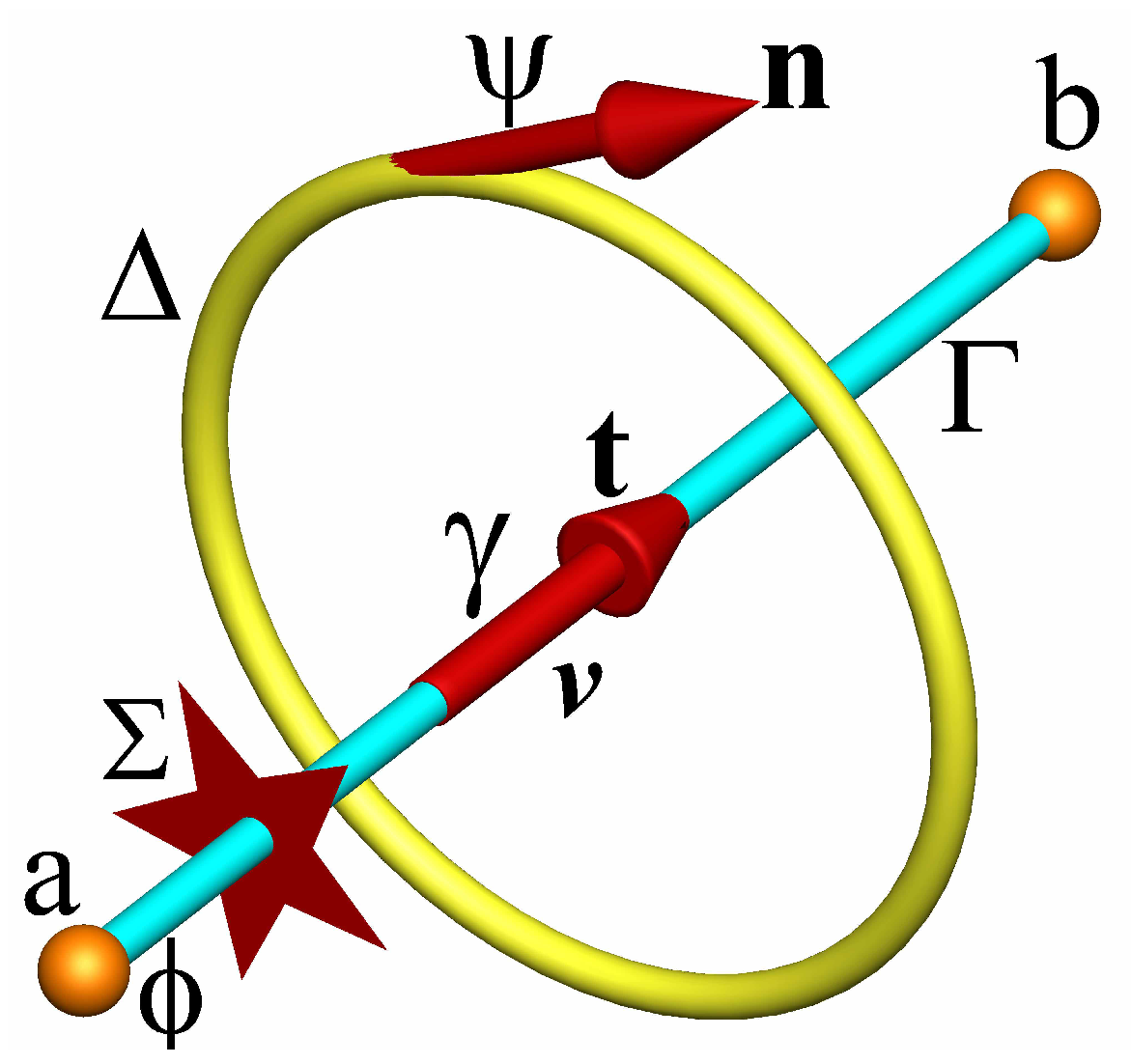

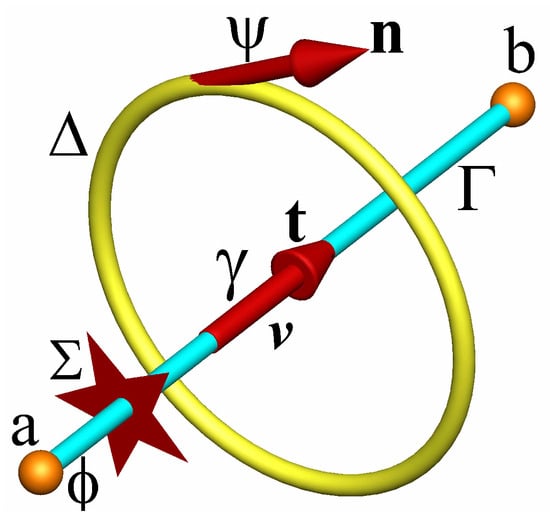

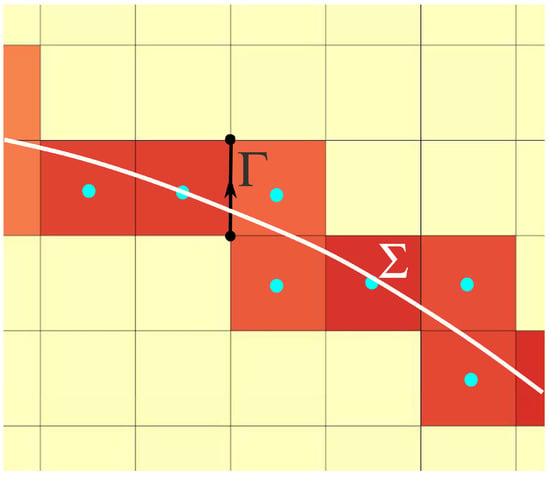

The derivation of the discrete equation of motion requires a complete geometric framework; the notions of continuous medium, derivation at a point, analysis and continuum mechanics are abandoned and replaced by two structures called primal and dual, which can be inverted. The privileged directions of classical mechanics, like the notion of global frame of reference, are also abandoned. Figure 1 shows schematically the two elementary geometric structures; their orientation in space is not specified—one will simply define a local frame of reference by the orientations of the unit vectors of the segment and orthogonal to the primal facet . The local frame of reference is called in reference to the concepts of electromagnetism whose unification by Maxwell made it possible to understand the interactions of direct and induced currents in two interwined circuits [11].

Figure 1.

axwell local frame of reference: the primal structure is represented by the segment of length oriented by the unit vector ; the planar primal surface is constituted by the family oriented by the vector such that . The closed contour oriented by forms the dual surface whose normal is . The scalar potential is fixed at the vertices of the primary structure and the vector potential is carried by the normal. The star on the segment represents the trace of the interface between the two fluids.

The oriented contour of the primal facet is formed by the set of sides of the corresponding polygon; the primal and dual facets are considered to be planar, even if this is not always the case in practice. The contour of the dual facet is made up of all the oriented segments of the associated polygon. The vectors and are orthogonal by construction, . The segment of length , whose ends are a and b, is chosen to represent the component of velocity and the component of acceleration . The velocity vector and the acceleration vector will remain undefined; even if they can be reconstructed using their components, this will not be useful. Two functions will be used subsequently: , a scalar defined at points a and b named scalar potential, and associated with the unit vector named vector potential.

In addition, four discrete differential operators are introduced. The first is the operator applied to the scalar potential; it differs from the classical gradient vector because it only applies to the component on the segment , i.e., . Thus, is both a scalar on the oriented segment and a vector. The second operator, named primal curl, is calculated from the circulation of the vector on the contour using Stokes’ theorem, ; it will then be assigned to a dual contour and named , one of the curl components orthogonal to . Similarly, the dual curl operator corresponds to a line integral on the dual contour, then assigned to the primal segment ; the symbol chosen here to represent the dual curl is the most coherent and poses no problem of compatibility with the classical tensor product, since the notion of tensor does not exist in discrete mechanics. Finally, the divergence operator corresponds to the integral on the dual volume of all the fluxes having the same vertex, ; the result is then assigned to the vertex a. In a continuous context, is a polar vector and an axial or pseudo-vector. The two primal and dual curl operators are thus differentiated by the function to which they apply. This discrete framework is completed by two notions, (i) the time lapse between the current time and the time where the initial equilibrium is defined, and (ii) the discrete horizon , the length traveled by a wavefront of sound celerity c on a rectilinear trajectory.

The physical model has many properties, in particular the local and global orthogonality of the operators, , also verified by the discrete operators; the discrete model also mimics the properties of the continuum and , whatever the polygonal or polyhedral geometric topologies, structured or unstructured.

2.2. Compressible Kinematics

The abandonment of the notion of mass for the derivation of the laws of discrete mechanics is suggested by the new interpretation of the Weak Equivalence Principle (WEP), where Newton’s second law is translated into an equality between accelerations . From this point onwards, the concept of continuum dynamics disappears in its turn in favor of an extension of kinematics. As a result, the notion of compressibility, which was closely associated with the material medium through density variation, can now be perceived from a different angle. The primary quantity in this approach is acceleration, considered as an absolute quantity, intrinsically measurable at any place and at any time without an external reference frame. Velocity is a relative quantity , which can only be calculated if its value at time is itself known; this is the principle of relativity or the principle of inertia. Similarly, the displacement at time must be defined from its value at time , i.e., .

The material medium could be anything from solid to fluid to vacuum, and the laws of mechanics would apply to the propagation of waves of all kinds. Abandoning the notion of material medium in favor of the concepts of propagation and energy opens the way to particle mechanics, with or without mass. As with material media, a particle’s motion is governed by the accelerations applied to it, rather than by forces, and its mass is therefore irrelevant to the description of its motion. The quantity that relates its own acceleration to the accelerations imposed on it is energy per unit mass ,

which depends on the velocity divergence. In the case where , motion undergoes compression, or expansion when . Contrary to the idea that this quantity is volumetric, this operator has a much broader physical meaning and applies to one dimension of space as well as to the motion of isolated particles. Consider the accelerated motion of two particles initially apart on a straight trajectory. If , they diverge from each other, and when this divergence tends towards zero, the distance separating them becomes constant. The increment of energy acquired or given up by a particle during the time lapse can be evaluated from the relation (1), written with the compresive energy per unit mass. Any particle or volume element in a material medium subjected to acceleration will see its energy increase or decrease according to the law (1). The massless photon obeys the same law, since it has a kinetic energy per unit mass . Compressible kinematics therefore dissociates the notion of material medium from that of propagation or motion. The differentiation between the material medium and the wave suggests an unusual view of their interaction: the celerity of a material medium does not exist until wave propagation approaches it; the celerity of a medium at rest or at low velocity is not defined.

2.3. Equation of Motion

The modeling of the equation of motion is initiated by the fundamental law of dynamics expressed in terms of acceleration, , i.e., the intrinsic acceleration of the particle or material medium is equal to the sum of the accelerations applied to it; the notion of vector addition is restricted here to the segment. Like the notion of mass, the concepts of force, pressure, and power are abandoned. The integration of acceleration on the segment of length is energy per unit mass. The sum of the imposed accelerations is modeled in two terms of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition, the first curl-free and the second divergence-free, . The integral law of motion is as follows:

The idea of deriving an equation of motion established for any inertial reference frame is abandoned. The discrete equation of motion is introduced for the local reference frame of length for a time period such that , where the quantities , and are defined. Quantities with an exponent o refer to the same quantities at time when mechanical equilibrium is assumed. The scalar and vector potentials are called retarded potentials in reference to the retarded potentials of electromagnetism [12]; they are defined by

where and are the longitudinal and transverse celerities, respectively. They depend, of course, on the medium in which the waves propagate: the swell, a fluid or a solid, or a vacuum where, in this case, the celerity of light is equal to . By explaining the increases and , the law of motion becomes

Equation (4) is formally a wave equation and can be reduced to the following. The term represents the acceleration due to possible source terms, which will also be written as two terms of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition.

The potentials must be updated to reach equilibrium in the current state; the corresponding updates are written:

where and are, respectively, the attenuation factors of longitudinal and transverse waves, due to their dissipation by the medium. The symbol ⟼ simply translates the actualization of potentials at time . This explicit incremental process naturally reveals only the shear energy and not the complete rotation ; in fact, a uniform rotational motion characterized by the velocity such that generates no dissipation. The same reasoning applies to a uniformly expanding motion such that [13].

Inertia is a fundamental element in the equations of fluid mechanics. In Eulerian variables, the material derivative is composed of the partial derivative in time and the inertia terms themselves noted . These non-linear terms oppose the variation of translational and rotational motion in time and space, as well as conflict with the other terms of the equation of motion that ensure its equilibrium.

In classical mechanics, inertia terms are expressed from the velocity in a three-dimensional space . They take different forms, (i) , (ii) or (iii) ; the latter term is none other than the Lamb vector with .

In discrete mechanics, the velocity considered is that carried by the segment of the Figure 1; it is a scalar on a segment oriented by . Inertia is expressed differently: it is the sum of two orthogonal contributions of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition. The material derivative reads

where is also carried by the segment . This term can be assimilated to a curvature of the inertial potential, . As with the curvature of a geometric surface, the two curvature terms can add up, as in the case of the surface of a sphere; cancel each other out, as in the case of a minimal surface (a catenoid, for example); or take on any value. The case of zero inertia is linked (i) either to zero velocity or (ii) to a sum where the two terms annihilate; the motion is then qualified as non-inertial even if each term is non-zero. Some stationary motions, such as Couette or Poiseuille, have this characteristic.

The very special case of uniform rotation mentioned above is of great importance. It is considered inertial in classical mechanics and generates a fictitious term, the centrifugal acceleration. The expression (6) applied to this rotational motion leads to , the motion is non-inertial in discrete mechanics. This distinction and the generation of fictitious accelerations (centrifugal, Coriolis) are due to the very foundations of mechanics, to the concept of a continuous medium where all quantities must be represented at a single point. Since we are dealing with vectors, it becomes necessary to consider their components in the three-dimensional space . A null vector must therefore have all three of its components equal to zero, which is an overabundant constraint.

The two inertia components of , and can be non-zero but equal, and their difference zero. This is the case, for example, with the Poiseuille flow. Note that these two components are carried by the same segment, and that the operation is a simple sum. This result reveals a troubling aspect of classical mechanics and relativity, which use spatial reference frames. The age-old concept of the continuous medium, from which differential calculus, integration and mathematical analysis in general derive, implicitly introduces constraints on the representation of reality. Maxwell’s reference frame allows us to reduce the direct and induced actions of any phenomenon to a single representation on the segment. The case of uniform rotational motion is emblematic of the conceptual difference between the two approaches.

Euler’s equations in non-conservative form allow us to recover the usual meaning of the variables in the new approach. First, by dividing the internal energy equation by the density, we find is the law (1), noting that , the very definition of scalar potential acceleration. This conservation equation translates the equivalence between and the density . Finally, dividing the vector equation by the density gives ; it is therefore not possible to transform this relationship directly into the form . The underlying reason lies in the very nature of the concept of momentum , which inconsistently combines two quantities, one of which is a scalar and the other a vector. In discrete mechanics, has no meaning or representation in , the local frame of reference; only acceleration and velocity are carried by the segment. Some other thermodynamic quantities can be deduced from potential and velocity, notably entalpy, , which is identified by the Bernoulli potential .

The law of motion (4) is a wave equation that can be easily transformed by substituting the displacement variable into velocity and using the classic vector calculus formula :

In a Lagrangian description, the second derivative of matter in time becomes a partial derivative and we find a dalembertian law since, in fact, the solution does not depend on time in a Lagrangian description since it is defined only at time . This law applies to both displacement and velocity :

The term corresponds to a retarded field similar to that of electromagnetism [12]. Equation (7) is therefore structurally a relativistic law [13], like the wave equation or Maxwell’s equations. But the difference lies in the presence of two non-linearities, and , included in the material derivative. Thus, the discrete Equation (8) is relativistic, and the classical demonstration is based on the invariance of the equations by a Lorentz transformation [13].

At this point, it is worth comparing the concepts of discrete mechanics and continuum mechanics to clarify how the discrete formalism takes a different path from that of special relativity. The latter is based on the notion of a continuous medium and a change in reference frame in three-dimensional space. Lorentz transformations, like the quadrivector formalism of relativity, are defined for a space and time t, grouped together within the concept of space–time. However, the treatment of each direction of space is not homogeneous: the direction of wave propagation is privileged, while the other two orthogonal directions are unaffected. Furthermore, for the Lorentz transformation, the coordinates transverse to the relative motion of the , and frames are assumed to be invariant, and . It is therefore no longer necessary to consider these orthogonal directions, and the whole analysis of relativity theory can be limited to the direction of wave propagation and, of course, time. In discrete mechanics, the formulas for transforming laws from a frame of reference to a frame of reference no longer make sense, and interactions from one local frame of reference to another take place through cause and effect. A further restriction applies: these interactions are necessarily linked to a single direction in space, that of the path oriented by the unit vector for irrotational propagation. This leaves only two fundamental quantities: a direction in space and time. These arguments confirm the value of replacing the global reference frame of classical mechanics with Maxwell’s local reference frame .

The spatial discretization of the discrete law of motion (4) is performed using only four discrete operators: the gradient of the scalar potential restricted to the edge , the dual curl of the vector potential, the primal curl of the velocity, and the divergence of the velocity. The combination of these operators leads to a “ready-to-use” code where the velocities on the segments are the unknowns of the linear system; this is solved by a non-preconditioned BiCGStab2 conjugate gradient method. Time integration is performed using first- or second-order schemes, as appropriate. The computation times required to obtain a numerical solution between time and time t are very similar to those observed for solving the Navier–Stokes equations. All terms of the law of motion are implicited, except for the non-linear term, which is semi-linearized, so there are no other constraints on the time step.

Numerous test cases have already been published (i) on analytical solutions to Navier–Stokes equations, (ii) reference solutions for steady or unsteady laminar flows, (iii) two-phase flows, (iv) Fluid Structure Interaction, (v) solutions for compressible flows with or without shocks and (vi) solutions for turbulent flows. In all these cases, including turbulent flows, the convergence of the numerical solution is of order two in space and time. Convergence in compressible hyperbolic test cases is of order one in shocks, as in other TVD-type schemes.

2.4. Capillary Surface Tension and Curvature

The calculation of the average local curvature of interfaces and the form of capillary source terms in the law of motion are two essential elements for representing transport at the interface between two fluids; these two quantities are distinct, even though some formulations combine the two concepts. This is the case in Brackbill’s CSF (Continuum Surface Tension) model [6], where the surface force per unit interfacial area is written as follows:

where is the surface tension, is the average curvature, and is the normal to the interface. If the two fluids are separated by an interface, with the normal oriented toward fluid 2, the two phases are identified by a volume fraction :

where the discontinuous interface is replaced by a zone of continuous variation of c with a thickness h of order of magnitude related to the mesh . In order to formulate the volume force, a modified phase function will be defined so as to vary continuously across the interface by convolution with an interpolation function [6]. If the law of motion is the Navier–Stokes equation, the expression for the volume force is

where is the jump in volume fraction on either side of the interface.

There are many other models for calculating the capillary term, including variants of Brackbill’s model or formulations, whether or not they separate the calculation of capillary force from the calculation of curvature. Various methodologies allow for very accurate calculation of the average curvature of interfaces, such as using front-tracking methods [14,15]. The reviews and articles [1,2] provide an overview of the main methods used to represent two-phase flows, particularly the VOF (Volume Of Fluid) method and the LS (Level-Set) method.

Discrete mechanics [9] take a completely different approach, based on the fundamental law of discrete mechanics formulated in terms of accelerations, where the capillary acceleration is expressed in two terms—one curl-free and the second divergence-free—in the form of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition,

where is the scalar potential of capillary acceleration and is its vector potential. Since the concept of mass has been abandoned, as has that of density, physical parameters must no longer include these quantities; thus, the surface tension becomes the surface tension per unit mass denoted by , whose unit is , and the product is an energy per unit mass expressed in .

The capillary energy carried by the edge is locally conservative; if and are the intrinsic acceleration potentials of fluids, the equilibrium of these quantities can be written in the form [7],

and, like any surface discontinuity, it is advected at the velocity of the interface between the two fluids. The quantities are the retarded potentials of the fluid acceleration, and are those of the capillary acceleration. The latter can therefore be expanded in the form

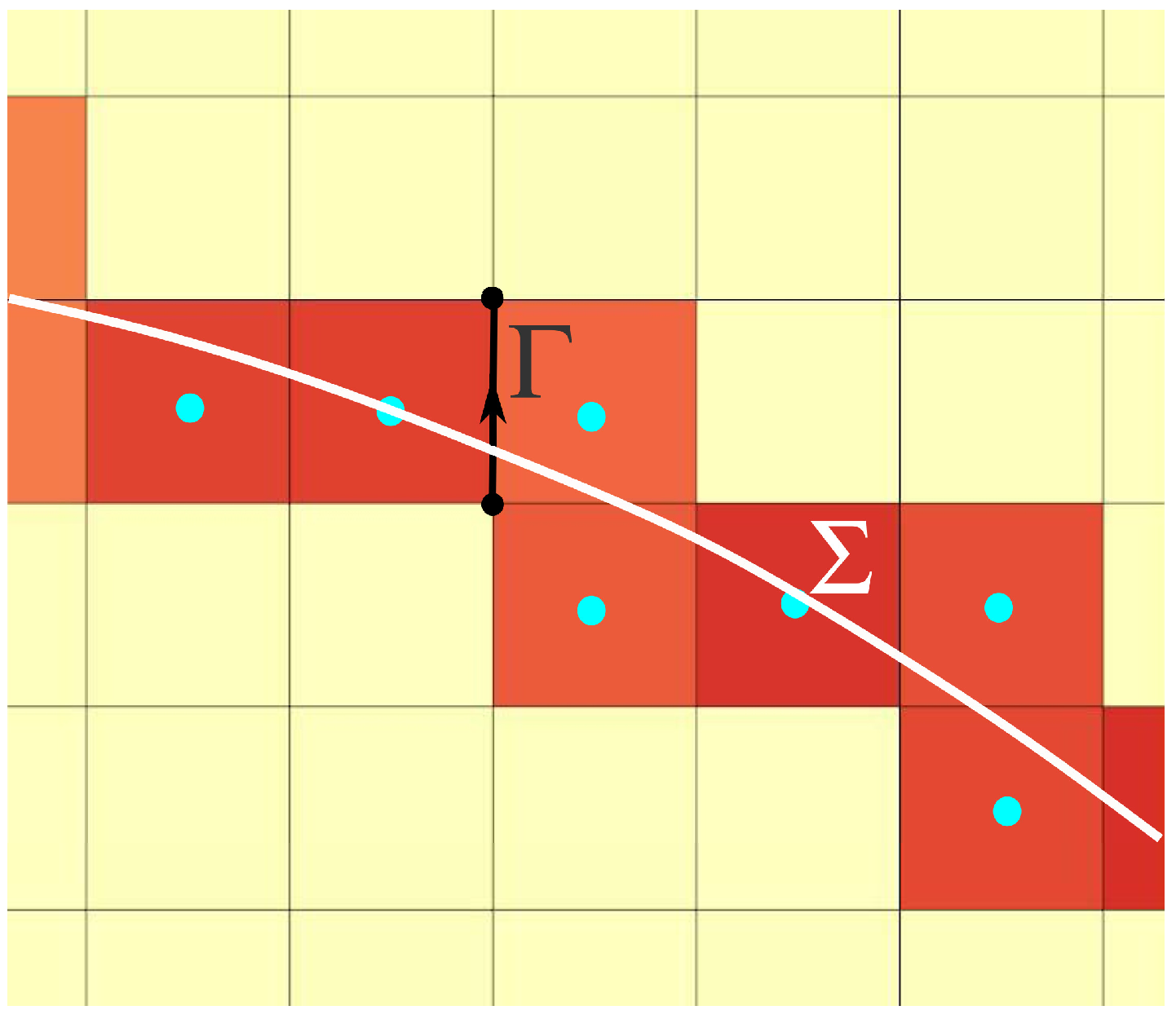

From a practical point of view, the procedure consists of initializing the capillary energy on the primal and dual geometric structures from located on the segments . The material derivative of this can be broken down into two accelerations: the gradient of the scalar potential and the dual curl of the capillary energy located on the facets. Figure 2 schematizes the deposition of the capillary vector energy at the initial instant on the segments of the primitive structure cut by the interface . The scalar potential is none other than the pressure difference on either side of the interface. Since the fluids are non-viscous, the local rotation is due solely to the rotation generated by capillary effects; this is localized in the two cells with a common edge crossed by the interface. The rotation in the other cells of the physical domain is strictly zero. The capillary acceleration modifies the velocity of the fluid at each instant and therefore the celerity of the interface.

Figure 2.

Interfacial energy deposit at initial time on the interface between two fluids discretized by the edges of the primal geometric structure.

The material derivative of the discrete field can be decomposed into an irrotational component and a solenoidal component in the form . It can be obtained using a specific solver, but it is the discrete law of motion that, in all cases, allows this Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition to be performed by separating the effects of compression from the effects of rotation. These retarded capillary potentials, and , represent, respectively, the energies per unit mass for the compression effects and the rotation effects relative to capillarity. They can be added to the scalar potential of the intrinsic acceleration and its vector potential . In the case of a global solution based on the local equation of motion, the velocity will integrate all effects. From a physical point of view, the two components of capillary acceleration contribute to the deformation of the interface in order to minimize the capillary energy locally.

In order to compare the orders of magnitude of the effects that intermingle in a viscous compressible capillary flow, the discrete law of motion, where the total acceleration is , is rewritten by grouping all these effects into the two components of the Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition,

It should be noted that viscous rotational energy is entirely dissipated as heat, while capillary energy is conserved locally in the retarded energy . Table 1 provides the values of energies per unit mass for three physical phenomena: compression effects, capillary effects, and viscous diffusion. Compression energy is evaluated by the longitudinal celerity , capillary energy by the celerity , and viscosity by the kinematic viscosity of the fluid . In this formulation, the discrete curvature is evaluated based on the dihedral angle [8].

Table 1.

Orders of magnitude of energies per unit mass (in m2s−2) of compressive, capillary, and viscous forces in the case of a water droplet with a radius of m for a characteristic time interval of s.

The orders of magnitude of these characteristics are calculated for a water droplet with a radius of 1 mm and a characteristic time s. Table 1 allows us to conclude on the relative importance of each of the terms. In particular, we see that the capillary compression effects defined by the value of are negligible compared to the very low compressibility of the fluid, which leads to a celerity , where is the isentropic compressibility coefficient. Thus, the capillary energy can be neglected in the term of Equation (15). The longitudinal celerities of liquids lead us to consider that the flows are practically incompressible, unless very low time constants are adopted. Viscosity obviously plays an important role at high time constants, where the dissipation of mechanical and capillary energy ultimately destroys the finest structures, particularly in turbulent two-phase flows. In two-phase fluid mechanics, these comparisons are made using the Weber number and the capillary number . The order of magnitude of the capillary velocity itself can be estimated from the surface tension and curvature, .

The curvature of the interface is an essential element of capillary effects, but it is only a geometric component of the formulation of these effects in the law of motion. In fact, the group is the main marker of capillary-induced movements; it is an energy per unit area expressed in m2 s−2 in the International System, located on the segment of the main geometric structure. Two other locations of this capillary energy are defined, with the first denoted located at the vertices of the main structure and located on the facets cut by . Thus, knowledge of the initial capillary energy alone is sufficient to generate capillary fluid motions. The discrete equation of motion strictly conserves energy per unit mass thanks to the local acceleration . In the context of discrete mechanics, the practical calculation of curvature is performed using proven Eulerian and Lagrangian techniques, described in detail in previous articles on the subject [8,10].

2.5. Surface and Shock Discontinuities

The discrete law of motion reveals two contributions where the time derivative is equal to two accelerations, the first being curl-free and the second divergence-free. When the motion is essentially compressible, the role of the isentropic compressibility coefficient or the longitudinal velocity becomes predominant. The action of capillary effects generates pressure variations that are all the greater as is large, particularly for liquids. The transport of two immiscible fluids corresponds to a surface discontinuity where the velocity of the interface is equal to the normal velocity of the fluid, but capillary waves also lead to shock waves governed by the velocities of the fluids present.

The discrete formulation is based on two forms of energy: the compression energy per unit mass represented by the scalar potential and the rotational or shear energy determined by the vector potential . It is therefore essential to modify Euler’s equations by replacing the pressure with the scalar potential , writing

where represents continuous flows, is this same energy integrated over the segment of the main structure, and is the average density over this segment; these last two quantities are piecewise constants and are integrated into the gradient operator of expression (16b). By setting , we define an energy per unit volume, , located at the interface. The quantity appears as a phase function that characterizes the intersection of the segment and the interface . The first term of the second member of (16b) is volumetric and corresponds to the thermodynamic variations of fluid quantities, while the second term is related to the surface and defines the energies associated with discontinuities, contact surfaces, and shock waves. Euler’s equations can thus be reformulated as an alternative integrating discontinuities,

Only the vector Equation (17a) is solved in order to obtain the discrete velocity . The potentials , and are then updated from the divergence of the velocity and its curl . In the case of irrotational flows, the last term of (17a) is then omitted, as is the update (17d). The potential is updated by writing the increment in the form . Clearly, the thermodynamic and surface effects characterized by and allow energy exchanges between the two, but the total mass and energy will be conserved. The discrete law of motion can be written, ignoring rotational effects, symbolically as , where the indices refer to volume and surface. The solution to a two-phase flow problem where capillary effects are present is represented by the quadruplet , where the potentials are advected using an appropriate methodology.

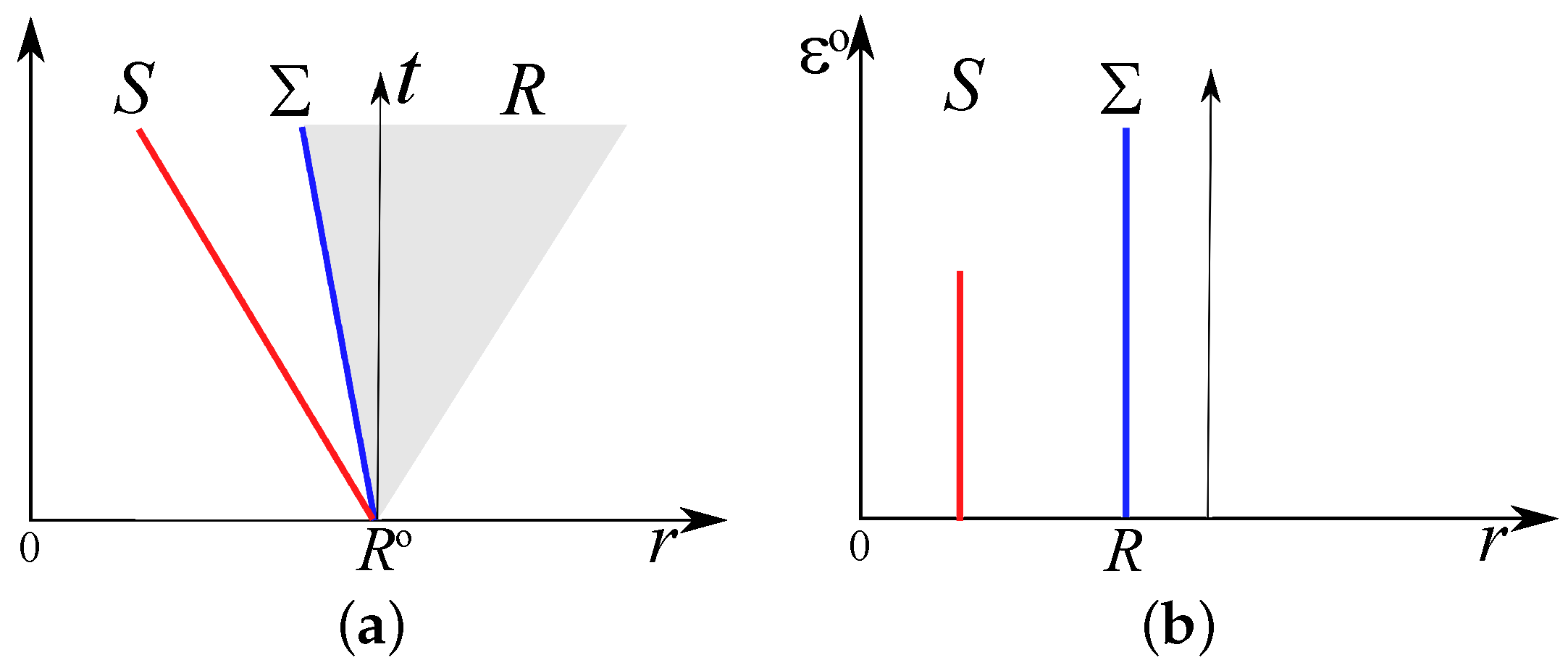

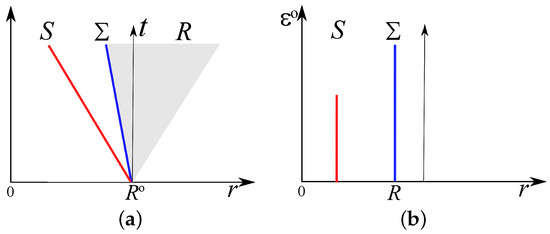

Figure 3 is a schematic representation of the extension of shock and rarefaction zones over time. In the case of a drop initially at rest without capillary acceleration, the pressure or scalar potential is uniform throughout the domain; once capillary effects are activated, the drop is subjected to low-amplitude radial compression because the velocity of the liquid it is composed of is high. This compression is correlated with an expansion of the surrounding liquid in the form of a rarefaction wave. These waves persist for a long time but eventually disappear, resulting in static or dynamic equilibrium depending on the problem under consideration.

Figure 3.

(a) Representation of the radius as a function of time of waves in a cylindrical drop initially at rest subjected to capillary acceleration; is the surface discontinuity, is the shock wave, and is the rarefaction zone. (b) The instantaneous capillary energy associated with the waves.

The conservation of certain quantities is a pillar of the derivation of mechanical equations. The Navier–Stokes and Euler equations conserve the mass, momentum, and total energy of a system . Discrete mechanics is governed by other principles, mainly the conservation of acceleration, a local quantity based on the length segment of the Maxwell reference frame. The conservation of acceleration is in fact the conservation of total energy per unit mass, composed of the acceleration of compression and that of rotation. For irrotational compressible flows, Euler’s equations conserve total energy ; in discrete mechanics, the conservation of total energy per unit mass is local, and its extension to the physical domain under consideration requires integration over mass rather than volume. If the physical domain represents both the mass it contains and its volume, the conservation of total energy is written as follows:

where and .

Thus, total energy conservation is ensured by the discrete formulation expressed in terms of energy per unit mass, both locally and globally, noting that in the latter case, integration must be performed over the mass element . Mass conservation is implicitly ensured by the equivalence between mass and intrinsic energy in the discrete formulation.

3. Some Basic Capillary Flows

3.1. Laplace’s Static Equilibrium

In almost all applications covered by the Navier–Stokes equations, the solutions correspond to observations, but in exceptional cases, they can lead to artifacts because they are not complete. This is the case with Laplace’s static equilibrium, where a drop of fluid takes on a spherical shape in another fluid that is immiscible with that of the drop under the influence of capillary forces or accelerations concentrated on the interface between the two media. This problem can be solved analytically by taking certain assumptions into account. Laplace’s law can then be written as a pressure difference , where is the curvature of a sphere of radius R. The problem posed here is different: it is a question of whether static equilibrium can be obtained as a convergence to the steady state of an evolution problem modeled by the Navier–Stokes equations. To transform this problem of two fluids separated by an interface with specified boundary conditions into a single-fluid model where the capillary terms are introduced in volumetric form into the Navier–Stokes equations, it is necessary to reformulate these terms based on the normal and tangential stresses of continuum mechanics.

where is the viscous stress tensor, p is the pressure, and is the surface tension. The last term corresponds to Marangoni effects present if the surface tension depends on temperature. This condition of classical mechanics, which applies to the interface between two fluids, is simplified in the case of two non-viscous fluids because, in the case of Newtonian fluids, the viscous stress tensor becomes zero with viscosity. For static equilibrium, only the second member remains, which is itself equal to zero.

The modeling of volumetric capillary source terms was carried out by J.U. Barckbill et al. [6] considering non-viscous fluids and constant surface tension. The capillary force introduced into the Navier–Stokes equations thus becomes

where is the normal outside the interface and is an indicator of the presence of the interface in the volume.

To clarify the nature of this term, consider a drop of radius R of one fluid in equilibrium with another; the two immiscible fluids generate a surface tension per unit mass where is the surface tension. This case is simplified by limiting the physical domain to a plane and the drop to a circle of the same radius. This problem, known as Laplace’s capillary equilibrium, defines the capillary pressure difference as , where is the curvature of the interface at mechanical equilibrium. If the shape of the interface is not initially circular, the effects of capillarity induce velocities in both fluids that rapidly attenuate if the fluids are viscous, leading to perfect mechanical equilibrium where velocities are strictly zero on the macroscopic scale. The only question that arises here is whether the Navier–Stokes equations correctly simulate this phenomenon, both dynamically, of course, and in terms of static equilibrium.

This elementary test case used to qualify the capillary models introduced into the Navier–Stokes equations in the study of two-phase flows actually covers many physical and numerical aspects related to the choice of the discrete capillary model, the spatial approximation and time steps of the simulations, the choice of the interface tracking method, etc. Since the 1990s, many authors have reproduced this problem from the Navier–Stokes equations by incorporating a source term localized on the interface . The best-known one is the model by Brackbill et al. [6], the Continuum Surface Force (CSF) method, which introduces a source term based on the general definition of capillary force where is the normal outside the interface , is the local curvature, and is the Dirac delta function, which specifies the location of the interface. Many variants have since been developed, most of which incorporate the density of fluids in the form of a ratio or a difference.

A phenomenon known as eddy currents or parasitic currents has been observed by authors who have used different capillary models to simulate small-scale two-phase flows. These parasitic effects are very well described by D. Harvie [16], who studied the phenomenon by establishing a correlation between the amplitude of these parasitic effects and the physical parameters of the problem integrated into three dimensionless parameters, the capillary number , the Reynolds number , and the Weber number . These quantities are written as , and , where V is a characteristic flow velocity, is an average density, and is the viscosity of the continuous phase. These parasitic currents, which can sometimes have a significant amplitude, persist indefinitely even when macroscopic mechanical equilibrium is reached. D. Harvie correctly attributes the presence of these currents to the generation of erroneous rotational components but does not give the root cause of these non-physical effects. Many authors claim to have significantly reduced these parasitic currents using more sophisticated capillary models, but they do not provide the exact cause of their existence and do not question the model based on Navier–Stokes equations; most authors attribute these effects to the discrete nature of numerical simulations. In summary, these parasitic currents, which persist over time in viscous and non-viscous fluids, reflect the inconsistency of these equations. Denner’s analysis [17] shows that implicit treatment of capillary flows makes it possible to overcome the strict constraints associated with capillary waves.

This opinion on the Navier–Stokes equations with the capillary source term is supported by several objective reasons. The first observation corresponds to the analysis of the velocity field when a polar orthogonal structured mesh is adopted. In this case, parasitic currents are absent and the velocity very quickly becomes strictly zero. The reason for this is that the interface only intersects segments that are orthogonal to it, so that the capillary force is a pure radial gradient whose accumulation in the pressure gradient exactly reproduces the Laplace pressure difference, . The second reason is related to the extension of the CSF model to tangential stresses, which are not taken into account by the model. Indeed, the capillary force (20) can be projected along a normal component, but also in the form of a tangential stress, in the form

where is the unit vector of each segment intersected by the interface and is the normal to this vector in the same plane. This local decomposition leads to a formal separation of normal effects and tangential effects, which are assumed to be zero in the CSF model. The result is instructive: (i) if the second component is ignored, we obtain the previous result in which the pressure is close to that theoretically expected, and parasitic currents are present; (ii) taking into account the second component of (21), a vortex superimposes itself on the compression of the drop. This rotational flow has no physical significance since the velocity at equilibrium must be strictly zero. However, the second component of the capillary force does exist and should result in a persistent tangential stress.

In summary, the Navier–Stokes equations were established based on the conservation of momentum derived from Newton’s second law, but the forces applied in the form of source terms were considered to be derived from scalar potentials. Dynamic or static equilibrium required the introduction of a potential, pressure, but no potential to ensure the equilibrium of tangential stresses. This lack of symmetry in the Navier–Stokes equations prevents certain properties associated with them, as defined by Noether’s theorems [18]. Proof of this observation is provided by the following experiment: Laplace equilibrium is approximated using a simulation in polar coordinates where the drop is geometrically consistent with the mesh whose axes are oriented along r and . Thus, the normal outside the interface is oriented along r and the component along is zero; in this case, the capillary acceleration is reduced to and there are no more parasitic currents.

In discrete mechanics, all source terms of the law of motion (4) are written a priori in the form of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition, particularly those of capillary effects,

where is the normal vector to each of the facets of the primitive geometry and is the discrete surface tension.

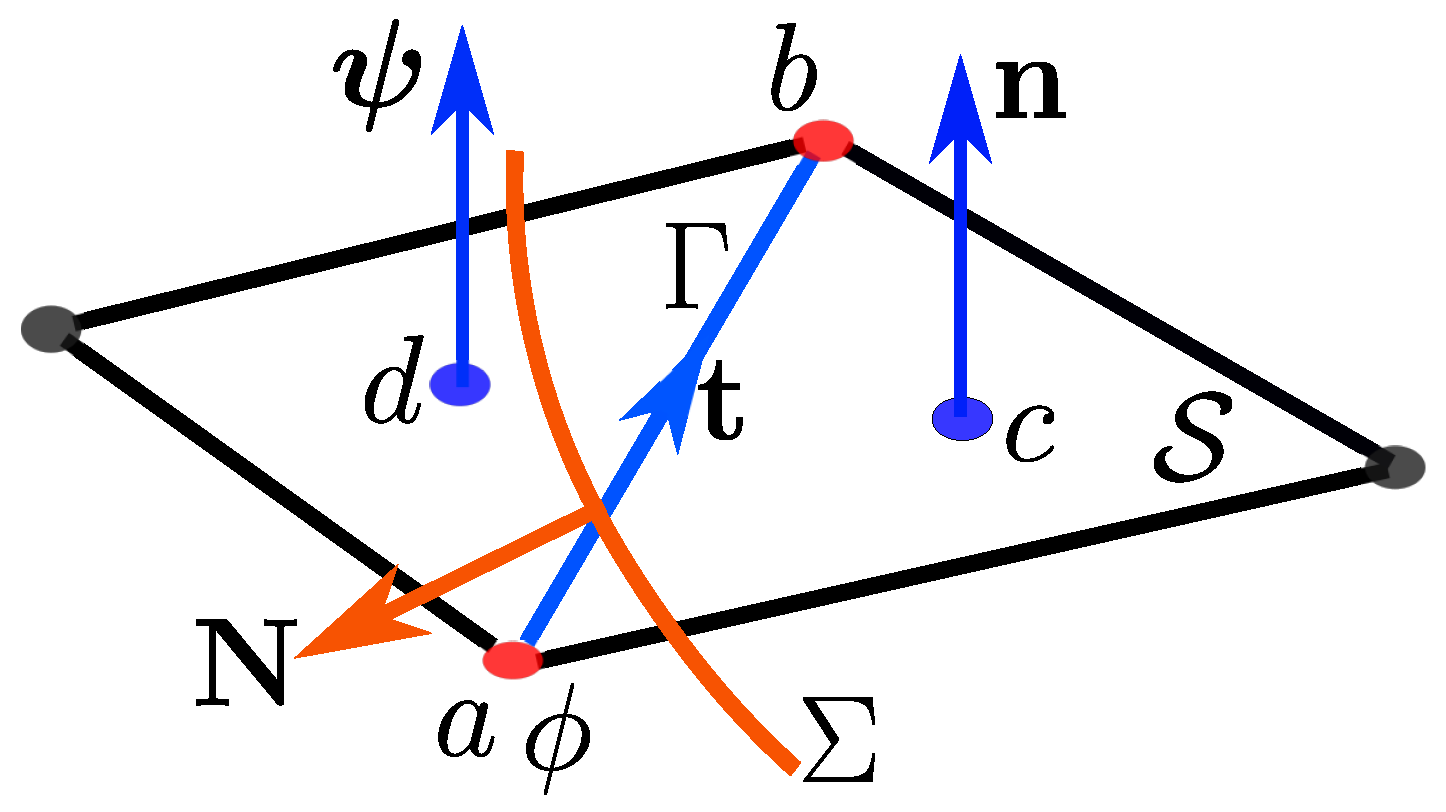

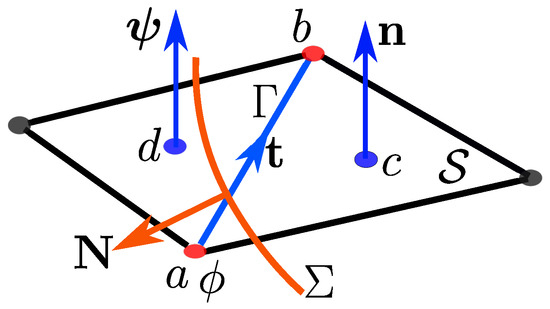

The location of the physical quantities is specified in Figure 4, which shows the interface between the two fluids; the scalar potential and the surface tension are positioned at the vertices of the primitive structure, and the vector potential and the transverse surface tension are located on the facet . In the absence of variations in surface tension as a function of temperature, the connection conditions between the two media are written as follows:

where, unlike in classical mechanics, the tangential stresses are not zero, even for an ideal fluid () or for a state of static equilibrium. In the latter case, the normal and tangential connection conditions are separated into two relations, (23a) and (23b). In fact, these conditions are implicitly satisfied in the discrete law of motion (4) equipped with capillary source terms.

Figure 4.

The interface of the external normal in a plane intersects the segment oriented according to between vertices a and b; the scalar potential is located on the vertices and the vector potential is located on the facets oriented according to , located at c and d.

In the absence of the Marangoni effect, condition (19) relating to classical mechanics is reduced to the normal component alone, which reproduces Laplace equilibrium when the curvature is constant. This is not the case for discrete mechanics, where tangential stresses due to capillary effects accumulate in the vector potential . The explanation for this physical phenomenon lies in the similarity between fluid mechanics and solid mechanics. The bending of a beam generates compressive and shear stresses on either side of the neutral fiber. The Laplace equilibrium for two Newtonian fluids generated by capillary actions is, of course, a static state where the velocity is zero at equilibrium, but the pressure difference on either side of the interface only exists because the drop collapses in on itself, creating a radial movement counteracted by the incompressibility of the fluids. At the same time, the tangential stresses created by the non-zero curvature of the interface accumulate in the vector potential under the influence of the expansion of the fluid on the outside and its contraction in its concave part, even if the velocity remains zero. In this process, the role of viscosity is zero, as is velocity.

The discrete law of motion (4) intrinsically solves this problem. Regardless of the discrete capillary model chosen, the physical parameters, the mesh quality, or the interface transport method, the capillary source term must be written in the form of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition, the sum of a curl-free component and a divergence-free component [19]. If this is not the case, such as in the CSF model, , or in any other model, the pressure difference will be obtained by accumulation of the compression effects included in this source term, but no other term in the Navier–Stokes equations will compensate for the rotational components of the parasitic currents. On the other hand, the discrete model (4) introduces the vector potential , which is equivalent to the scalar potential for compression effects in terms of rotational effects. In the case where the source term is not decomposed beforehand, the capillary mechanical equilibrium is described by the equation

where terms involving velocity are strictly zero.

The physical model is developed by the author in [8] with numerous examples of capillary flows. In particular, the source term can be divided a priori into two components of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition, , where the two capillary potentials can themselves be expressed as functions of velocity . The discrete Equation (4) allows us to simulate the evolution of velocity and potentials over time and naturally reduces to a static Equation (24) when mechanical equilibrium is satisfied.

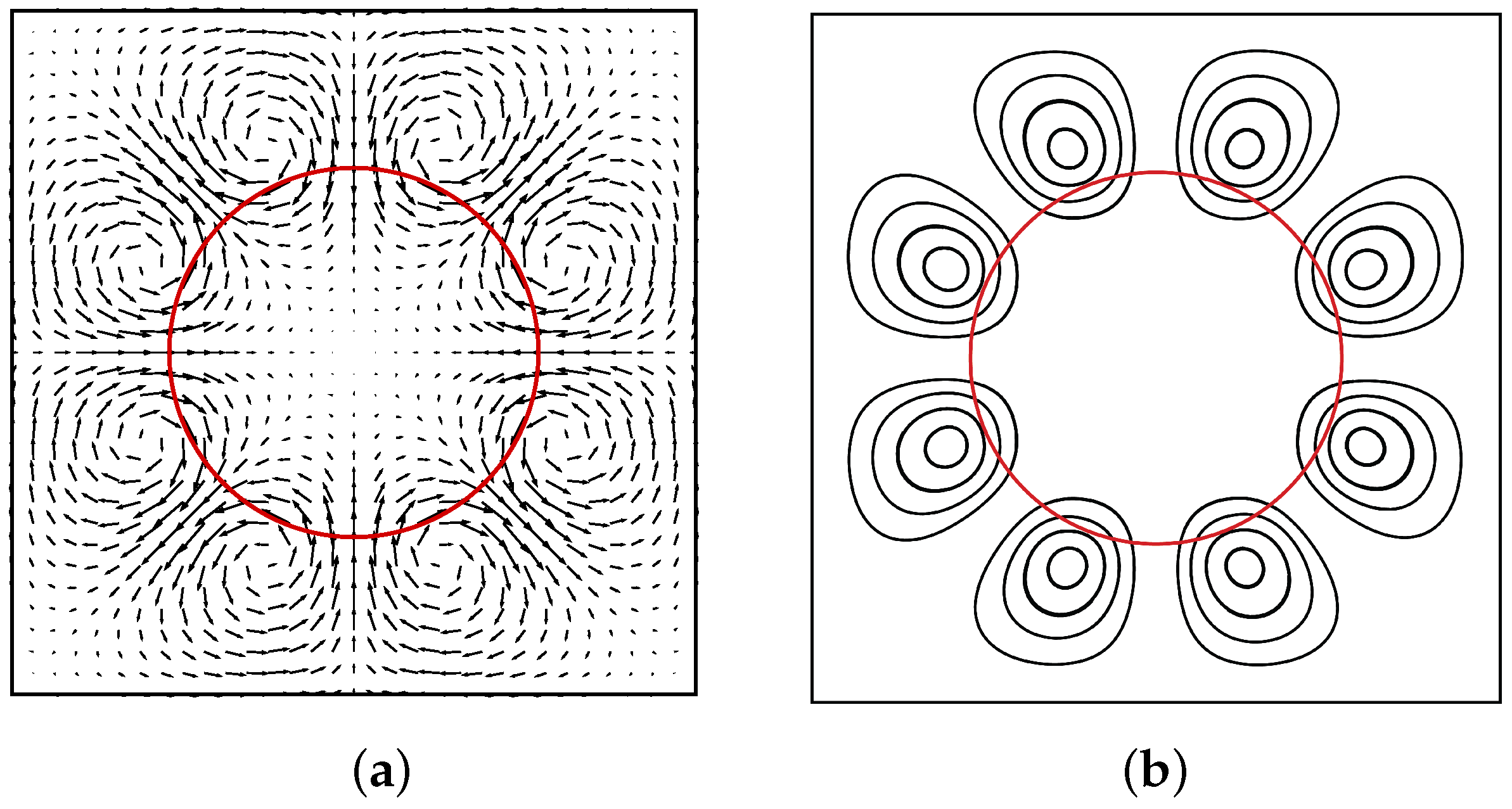

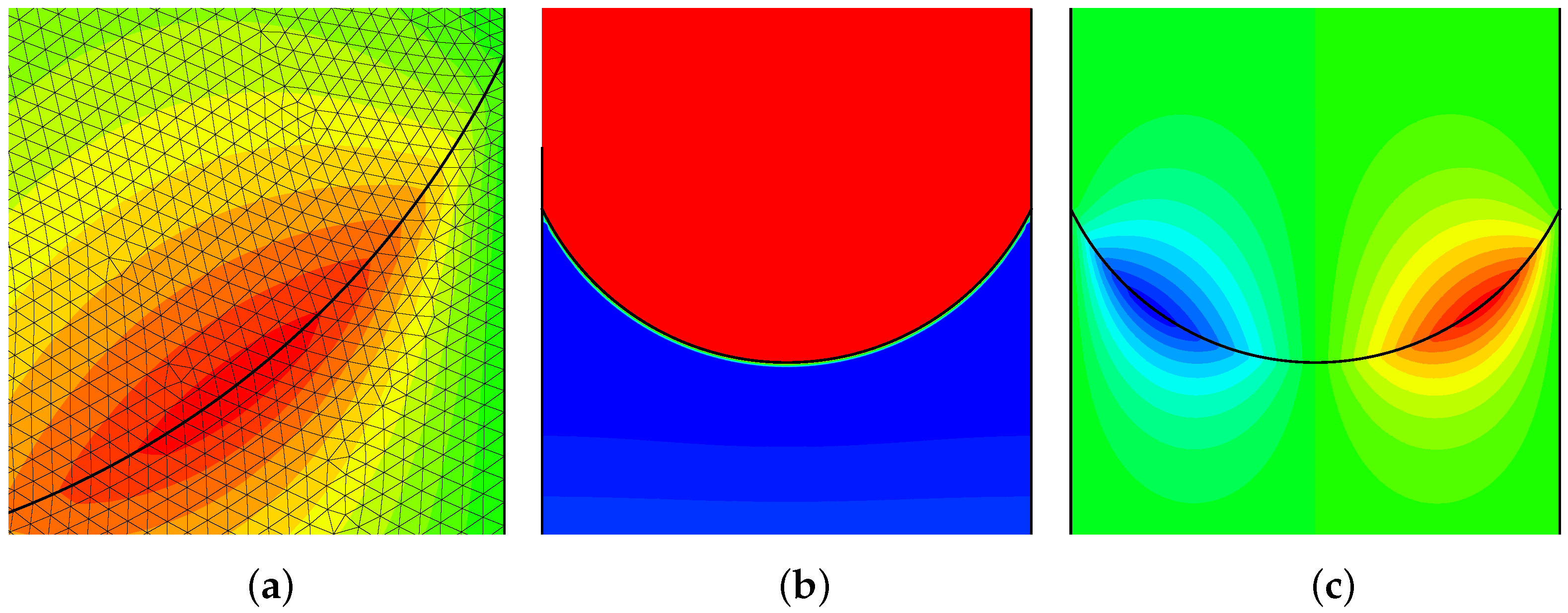

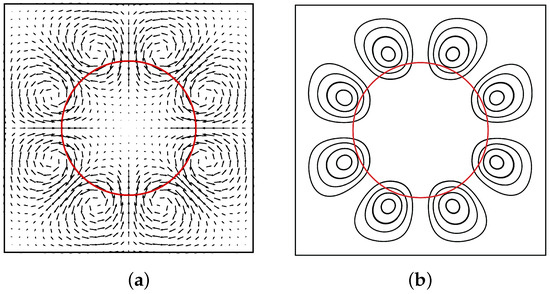

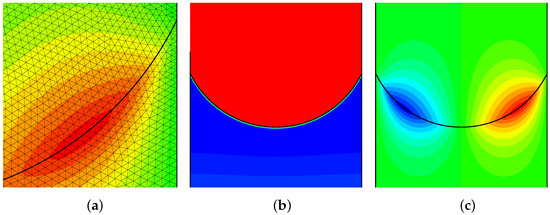

To clarify the nature of parasitic currents, consider a simple example of a cylindrical water droplet of radius R in air contained within a square domain, as illustrated in Figure 5. The numerical simulation based on Equation (4) consists of integrating a source term and calculating the variations in velocity and potential until a steady-state solution is obtained. The circle defining the interface is projected onto a uniform structured mesh of Cartesian meshes, and a ray tracing method allows, in the general case, the vertices of this mesh included in the object concerned to be detected. The curvature is calculated from Lagrangian markers, but in this case, the curvature is constant and strictly equal to . The surface tension per unit mass is also a constant equal to ; the normal to the interface is also calculated with accuracy. Thus, the source term is defined exactly, and no numerical error supports the idea of parasitic currents linked to purely numerical artifacts. The phenomenon observed using the Navier–Stokes equations does not depend on (i) the densities of the fluids, (ii) their viscosities, (iii) the number of meshes in the structured or unstructured mesh, or (iv) the time steps used for the simulations. As indicated by D. Harvie [16], in the absence of forced convection, the intensity depends solely on capillary and inertial effects characterized by the capillary number and the Weber number . It is therefore not necessary to provide the numerical values used; the emphasis here is on the underlying reason for the existence of these parasitic currents. Observation of the results obtained with the two models presented in Figure 5 shows that they are very different. With the Navier–Stokes equations, in the absence of the vector potential , parasitic currents appear spontaneously in both fluids and cross the interface ; these persist indefinitely over time. When this potential is present in the discrete law of motion, the velocities attenuate rapidly and Equation (24) is strictly satisfied with a zero velocity throughout the domain, i.e., in machine double precision. In the latter case, the scalar potential difference on either side of the interface is strictly equal to , which is the theoretical value of Laplace’s capillary equilibrium. The absence of the vector potential in the Navier–Stokes equations leads to the maintenance of a rotational component whose existence cannot be guaranteed by the pressure gradient. Table 2 shows the value of the residual velocity norm for a simulation performed using the Navier–Stokes equations, as well as the norm of the vector potential for the proposed formulation in the case of Laplace’s static equilibrium. The velocity is never zero in the case of the Navier–Stokes equations, and the streamlines cross the interface between the two fluids in steady state. These behaviors do not depend on the time step or the spatial approximation.

Figure 5.

Viscous capillary static equilibrium of the Laplace problem. (a) Velocity vectors obtained from the Navier–Stokes equations with and ( ms−1) and (b) vector potential of the discrete law of motion (24) with a velocity field . The simulations were performed on a uniform Cartesian mesh of cells and the velocity is zero.

Table 2.

Norm of the residual velocity and norm of the vector potential for simulations based on the Navier–Stokes equations and the discrete formulation, illustrated in Figure 5.

Regardless of the capillary model, the properties of the fluids used, and the methodology chosen, the conclusions are always the same. The source term is explicitly or implicitly decomposed into a curl-free component and a divergence-free component. In fact, the equation of motion (4) behaves like a Helmholtz–Hodge extractor of the source term . Since the scalar potential alone cannot accumulate both pressure and shear stresses, it is imperative to introduce and maintain the notion of vector potential in all cases, including for Newtonian fluids. As in the previous example of capillary rise, mechanical equilibrium always results in the presence of these two potentials (25). The absence of this potential in the Navier–Stokes equations invalidates the notion of completeness necessary for any physical model.

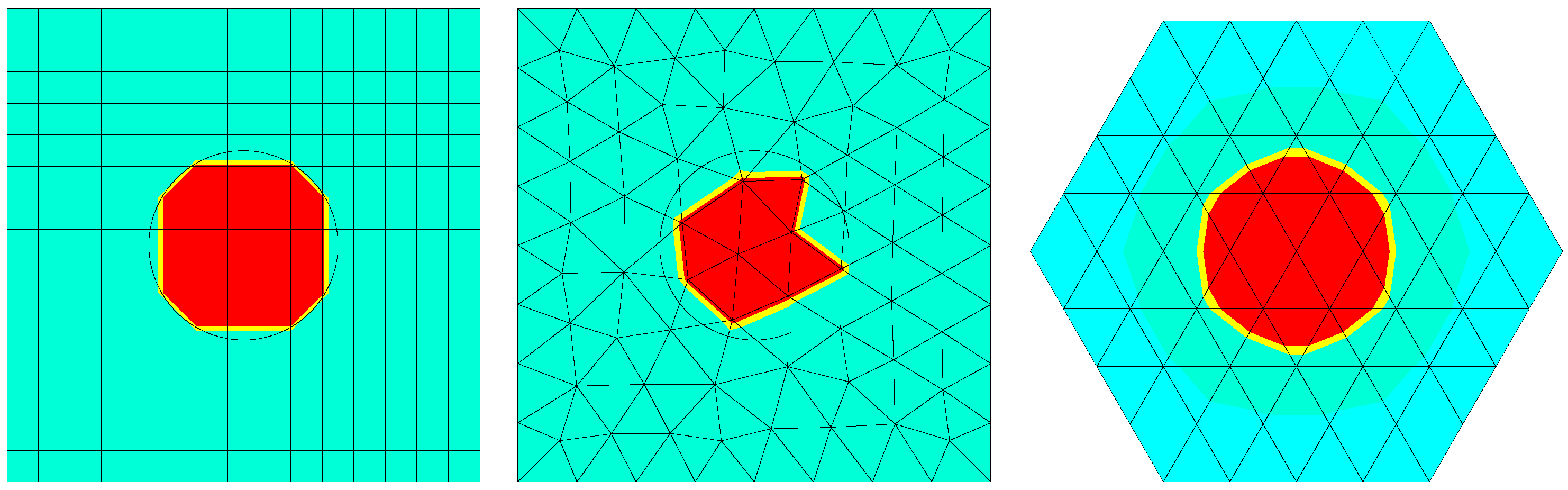

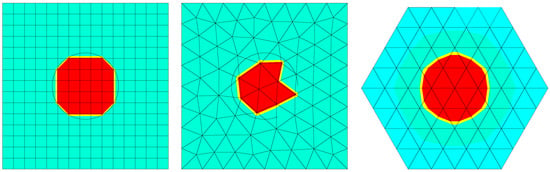

Figure 6 illustrates the results obtained for the Laplace problem in the context of discrete mechanics for several mesh examples: a structured Cartesian mesh, an unstructured mesh based on arbitrary triangles, and a mesh based on regular triangles.

Figure 6.

Equilibrium of a droplet under a capillary effect simulated using a meshes based on Cartesian quadrangles, triangles and equilateral triangles; the potential difference on either side of the interface is exact [10].

In all cases, including highly distorted meshes, direct numerical simulation provides a solution without parasitic currents, i.e., velocities less than and an exact value for the pressure difference between the two phases.

3.2. Capillary Equilibrium of a Fluid Between Two Planar Surfaces

Based on current knowledge, static capillary equilibrium in a tube with a circular cross-section or between two planes is defined solely by Jurin’s formula, where is the capillary tension, is the average curvature, g is gravity, and is the height to which the meniscus rises in static equilibrium; it should be noted that this height is an average value that corresponds to the barycentric height. This quantity is of course correlated with the pressure difference existing between the lower and upper parts of the vertical capillary tube. The problem addressed here is that of the completeness of the modeling of this phenomenon given in the current framework with the sole contribution determined by the equilibrium of pressure. The objective is to prove physically and mathematically that static equilibrium cannot be obtained from this single explanation of pressure.

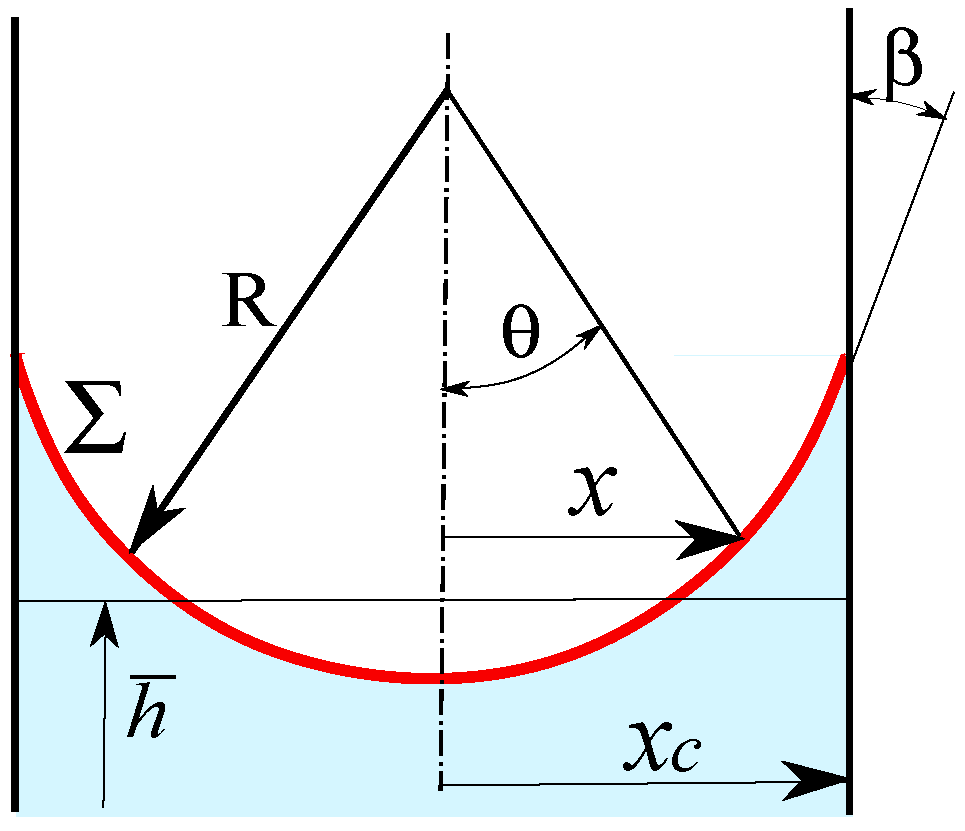

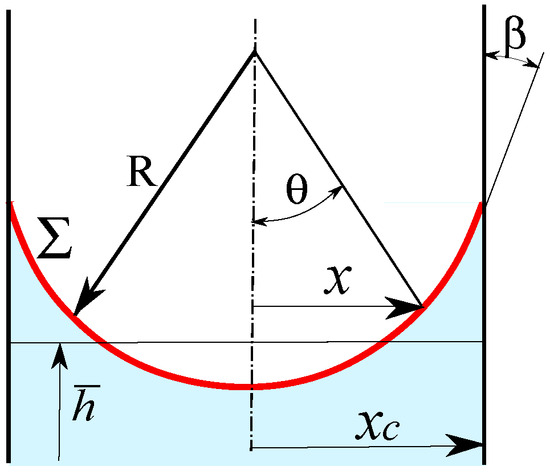

Consider two fluids, a liquid with density and kinematic viscosity covered by a gas with density and kinematic viscosity , contained between two planes separated by a distance . Figure 7 shows the interface formed between the two vertical planes of these two immiscible fluids; it is part of a circle with radius R, i.e., curvature , connected to the two planar surfaces by a contact angle . The gravitational acceleration is defined by the vector . The surface tension between the two fluids is here set at , where is the traditional surface tension.

Figure 7.

Diagram of the interface between two parallel planes separated by delimiting the liquid and gas phases, where is its radius of curvature, is the contact angle between the liquid and a vertical plane, and is the barycentric capillary rise height [9]; the red line represents the interface between the two fluids.

The source term representing external accelerations, capillary acceleration, and gravitational acceleration are not aligned in this case, and each is the sum of two components: one curl-free and the other divergence-free. The law of motion that expresses dynamic equilibrium in the presence of the other terms of compression and rotation is written as follows:

where the longitudinal and transverse velocities, and , define, respectively, the compressibility of the two fluids and the viscosity for Newtonian viscous fluids; the quantities and are the longitudinal and transverse curvatures. The Cartesian coordinates are calculated from the polar coordinates where x is the abscissa x is counted from the median plane and the origin of is defined from the barycentric height .

The physical phenomena involved in capillary equilibrium are complex and closely related. The effect of gravity tends to pull the liquid down between the two planes to reach an equilibrium where the interface is horizontal. Capillary effects act to pull the liquid upward near the surfaces. These contradictory effects lead to a surface that is part of a circle, neglecting the influence of gravity on the shape of the interface, which is a perfectly acceptable assumption if the distance between the two planes is small; this phenomenon is of secondary importance here, since the objective is to explain the origin of parasitic currents. The two contributions to static equilibrium are in fact related to the compression and rotation energies represented by the scalar and vector potentials. These two contributions are then written as follows:

with where is the kinematic viscosity of fluids.

The vector law of motion (26) contains all the terms necessary to simulate the different phases of capillary rise, with inertia governing the inertial phase in the early stages of the simulation where the rise velocity is a function of time in , and viscosity governing the later phase to reach static equilibrium where only gravitational and capillary effects persist indefinitely. It is this latter phase that is of interest, because the mathematical model, the law of motion, must be able to represent it strictly. This is the case in discrete mechanics where the law of motion, for a velocity set to zero in all terms, becomes

This relationship, where the gradient of one function is equal to dual curl of another function, is satisfied when these two orthogonal operators are equal to a harmonic function or a constant. Since potentials are only defined up to a constant, this relationship can be divided into two parts:

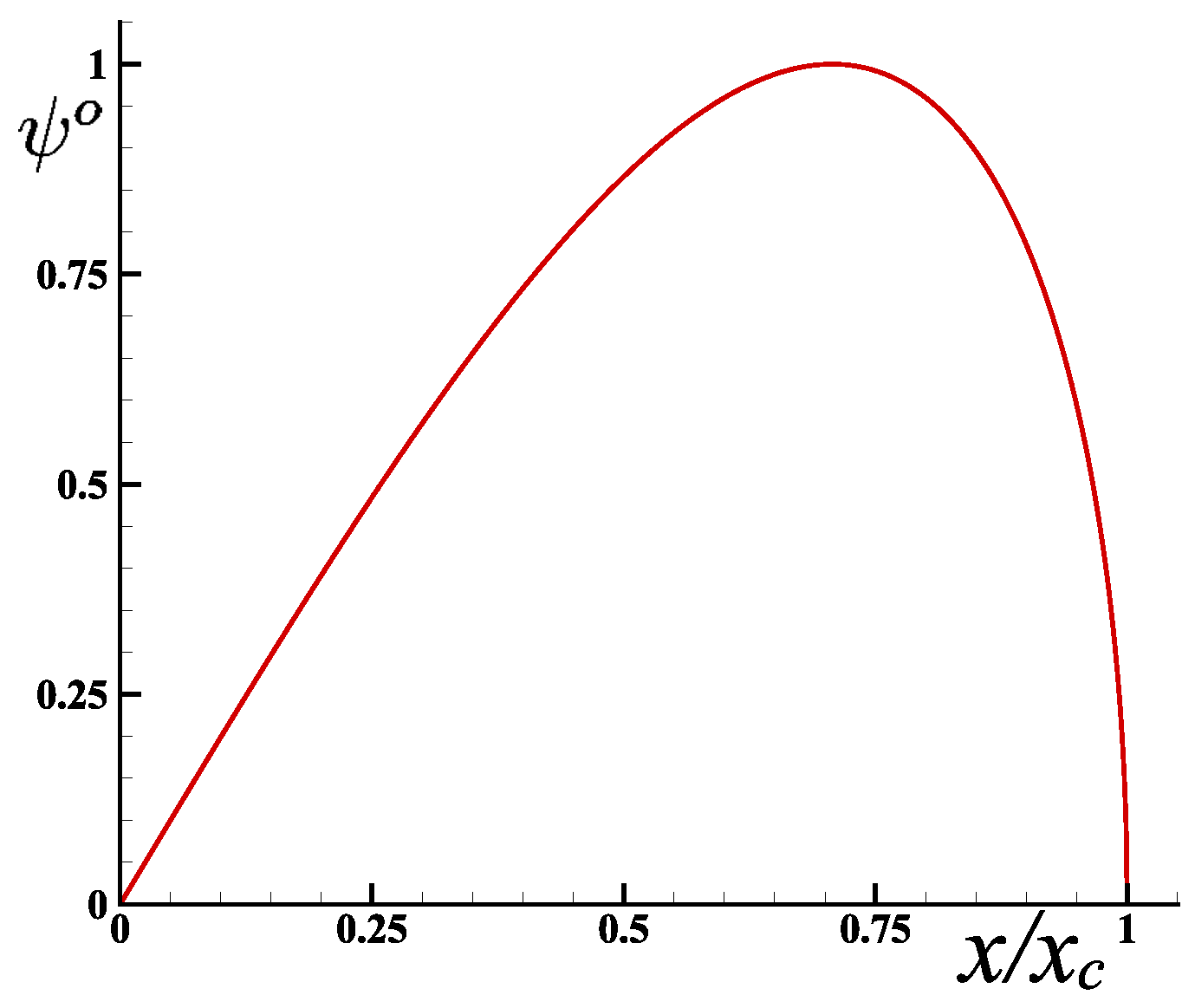

where is related to the shape of the interface, which, in this case, is cylindrical. We can deduce that the height is equal to , which corresponds to Jurin’s law, noting that is the barycentric height and not the height below the meniscus used by many authors. Noting that , we can finally deduce the expressions of the potentials as a function of x or the polar angle :

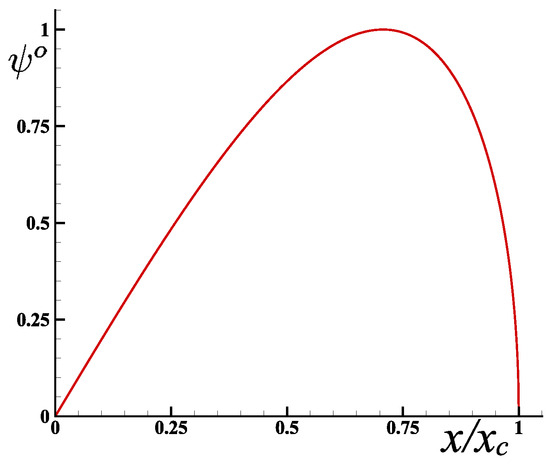

with , where is the limit angle, defined as the contact angle . The evolution of the vector potential is shown in Figure 8 as a function of the ratio along the interface . The maximum vector potential is reached for .

Figure 8.

Variation in the vector potential on the interface as a function of [9].

Jurin’s law is incomplete and insufficient to represent capillary equilibrium. This statement is true from a mathematical and physical point of view; it is necessary that the capillary equilibrium relative to this problem be strictly respected. Most work on capillary rise aims to show that the capillary height corresponds well to experiments or numerical simulations [20,21,22,23]. While experiments do indeed lead to the static equilibrium predicted by Jurin’s law, numerical simulations based on the Navier–Stokes equations reveal, regardless of the methodology used, parasitic currents in the form of vortices while the interface is stationary.

What physical analysis would allow us to conclude that there is a static equilibrium at a strictly zero velocity? The underlying reason is related to the accumulation of viscous stresses in a fluid. In the case of a Newtonian fluid, shear stress only exists if the fluid is in motion, so Newton’s law is written as , where is the dynamic viscosity. In discrete mechanics, the viscous stress takes another form, . In a viscoplastic fluid such as Bingham fluid, with very low stresses, there is a threshold where the fluid behaves like a solid, the velocity becomes strictly zero, while the stress does not. In the meniscus area, the fluid tends to descend under the effect of gravity, but capillary effects cause it to rise back up near the walls, and the two actions are not aligned. A vortex forms and persists for a long period of time; viscous stresses accumulate as in a solid and the velocity decreases. The Newtonian fluid model is then no longer able to represent this behavior with a very long time constant. The discrete law of motion (26) includes the equilibrium vector potential , which allows viscous stresses to accumulate in the same way that the scalar potential (or pressure) accumulates compressive stresses. Observation of fluids near a meniscus shows that velocities are not zero during capillary rise, but that they attenuate and tend toward zero when capillary equilibrium is reached. The modeling of an elastic solid is based on two potentials: the scalar potential , which accumulates compressive stresses, and the vector potential , which updates shear stresses from the term , where is the transverse velocity. At high time constants, Newtonian fluids do not accumulate shear stresses, and the product is replaced by the kinematic viscosity . In parallel with very low stresses, the shear energy is stored in the potential , and the fluid then behaves like a solid.

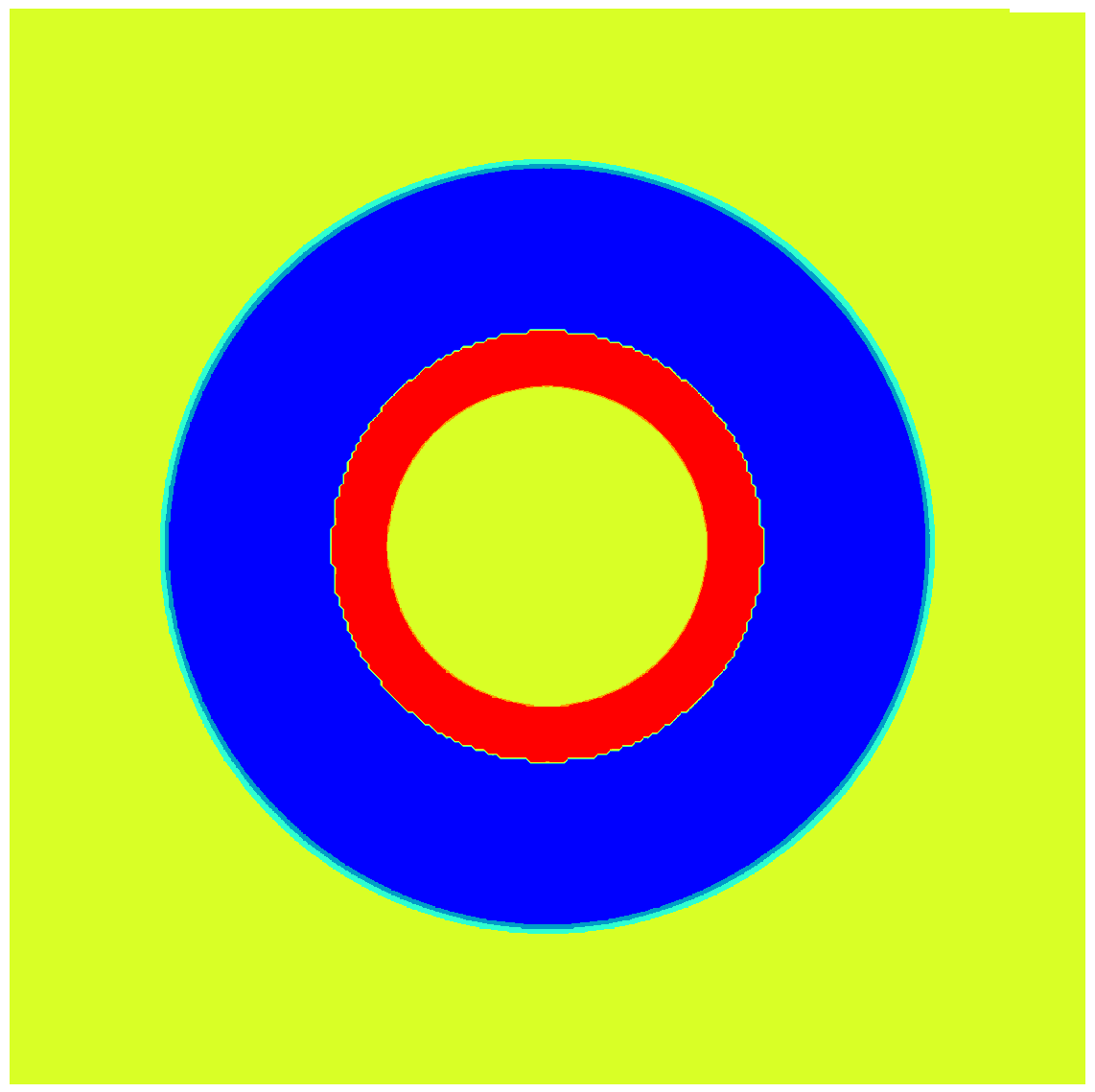

After this physical analysis, the problem can be addressed directly by solving the law of motion. Consider the geometry illustrated in Figure 7, which combines a liquid and a gas between two vertical planes. The densities of the liquid and gas expressed in SI units are, respectively, equal to kg m−3 and kg m−3. The kinematic viscosities are equal to m2s−1. The contact angle is set to a value such that and the half-distance between the two planes is equal to m. Given the contact angle, the curvature of the interface is therefore equal to m−1. The surface tension m3s−2 and the product is equal to m2s−2; furthermore, the value of gravity ms−2 leads to a barycentric capillary height of 10−3 m. The domain is flat, rectangular, with dimensions , and the base of the interface between the two fluids in static equilibrium is positioned at . The value of the downward vertical gravity is chosen so as to obtain an upward or downward displacement of the interface, or static equilibrium. The primal topology is shown in Figure 9a and corresponds to a mesh based on regular triangles delimiting the two media by a mesh line. The boundary conditions are associated with vertical solid walls () and horizontal free walls where the pressure is constant and equal to . The pressure difference on either side of the interface resulting from the simulations must be equal to at static equilibrium.

Figure 9.

(a) Detail of the primary mesh topology based on regular triangles; the interface is delimited by a mesh line separating the two fluid domains. The density of the lower fluid is equal to and that of the upper fluid is equal to . The curvature of the interface is equal to . (b,c) static mechanical equilibrium defined by the two potentials, scalar and vector . The maximum values of the vector potential are , while the scalar potential varies in the range . The velocity is strictly zero throughout the domain [9].

The procedure used to solve the problem by direct simulation consists of defining an interface at a fixed average height in the form of a portion of a circle and tessellating the two connected domains in two dimensions of space with regular triangles. Solving the law of motion then gives a non-zero velocity field whose average is positive or negative. Depending on the sign of this quantity, the height is adjusted to obtain a zero velocity field. Depending on the parameters defined above, the process actually leads to a state of rest and a strictly zero velocity. The static equilibrium is then described by (31),

where the gradient of one function is equal to twice the curl of another function. The Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition is the cornerstone of the derivation of the discrete law of motion; it is not used here a priori to separate the two components of a vector, but as a fundamental principle of the behavior of the entanglement of two phenomena. Maxwell’s frame of reference perfectly illustrates this principle by showing the respective roles of direct and induced actions. The results of the numerical simulation are presented in Figure 9, where the two static equilibrium potentials satisfy condition (31).

The static equilibrium results are perfectly consistent in both the liquid and gas domains, with a scalar potential varying in the range and a vector potential around the interface varying around zero, . The average height m is therefore consistent with the imposed gravity value, m s−2.

To conclude this problem of capillary rise between two planes or a tube, we can say that static equilibrium can only be achieved by introducing a vector potential that accumulates shear stresses in the same way that pressure accumulates compressive stresses. This phenomenon raises the fundamental physical question of the Newtonian viscous model at very low shear stresses; viscosity is fundamentally a difficult parameter to determine at very low time constants or very low stresses.

3.3. Compressible Laplace Equilibrium

The case of two-dimensional compressible inviscid capillary flow is treated using the general discrete formulation (4). The square with dimensions m contains a phase with a celerity equal to m s−1 and a cylindrical drop with a celerity of m s−1; the radius of the drop is equal to m and the surface tension per unit volume is set at m3s−2.

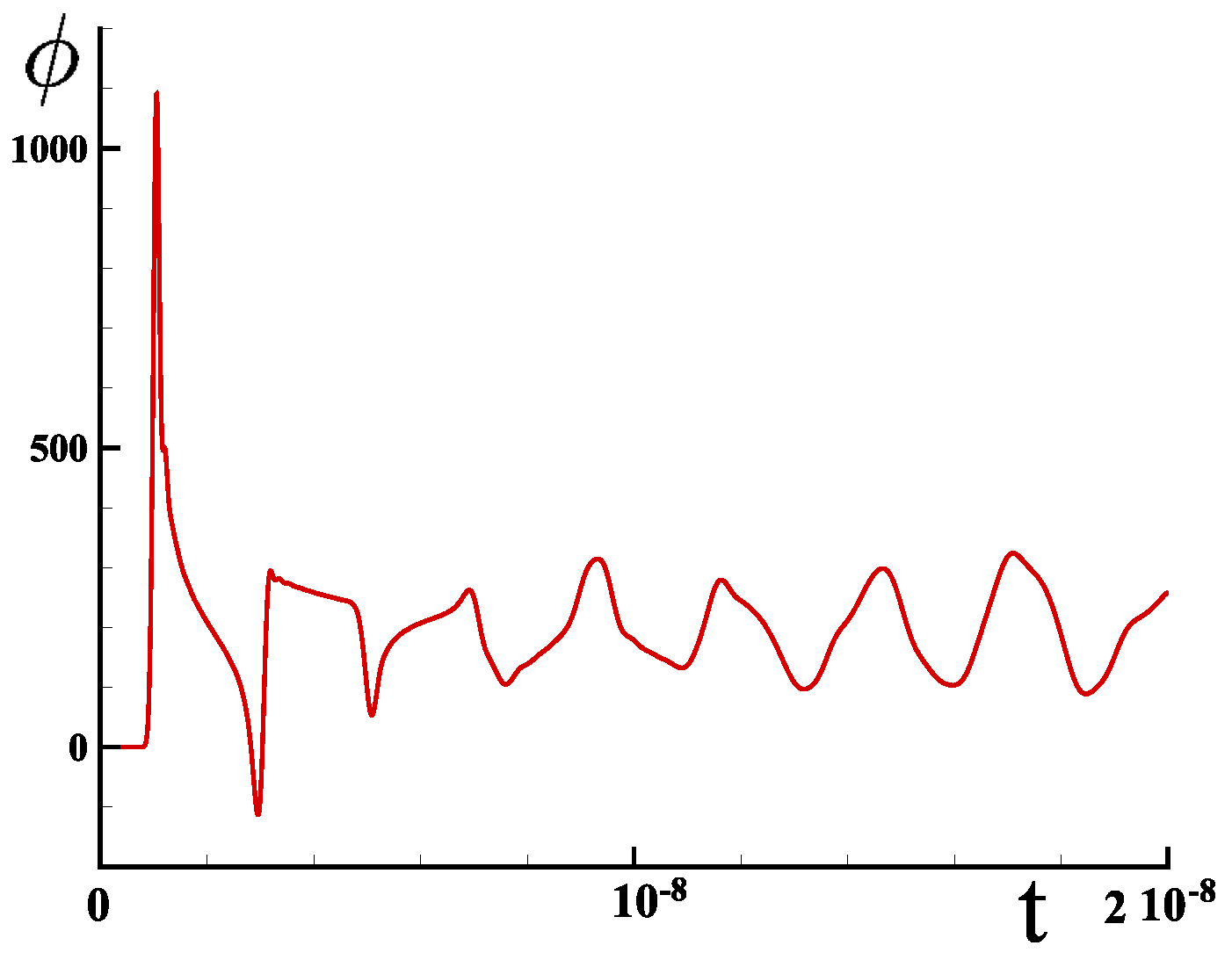

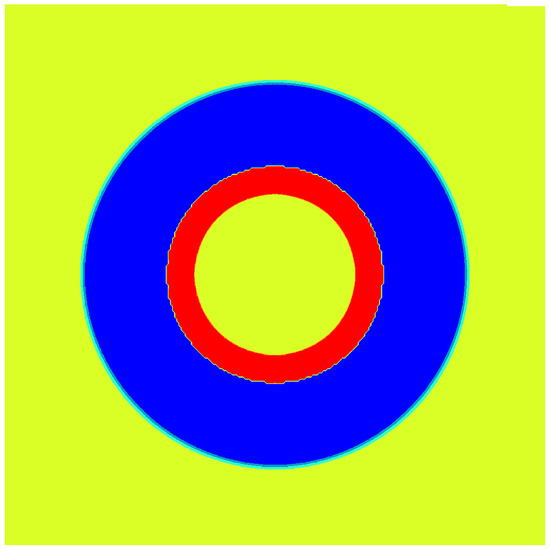

At the initial time, the velocity and pressure are strictly zero throughout the domain and the scalar potential is also zero. The two components of the capillary source term are then activated and compression and rarefaction waves propagate on either side of the interface, with the shock wave developing towards the inside of the drop and the rarefaction wave propagating towards the outside. Figure 10 shows the scalar potential field (pressure) for a time s. When the unstable waves reach the center of the drop and the edges of the square domain, they reflect and combine over time.

Figure 10.

Droplet with radius m in a square cavity is filled with two non-viscous fluids; the figure shows the scalar potential field; the Cartesian mesh contains cells, the time step is equal to s and the snapshot time is s. The velocities of the fluids are equal to m s−1 outside and m s−1 inside; the outline of the drop is represented by a white circle.

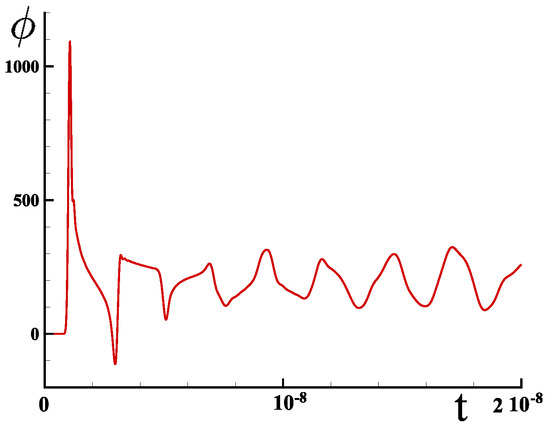

Figure 11 shows the evolution of pressure over time at the center of the cylindrical drop. Under the specified conditions, the static equilibrium pressure is equal to Pa. The pressure at the center of the drop remains zero, but when the shock wave concentrates there, the pressure becomes much higher than the equilibrium value. After this stage, the relative pressure becomes negative, and the successive expansions and compressions attenuate more or less rapidly depending on the value of the viscosity, which is zero in this case.

Figure 11.

Evolution of scalar potential (pressure) at the center of the droplet over time.

The results of this simulation are entirely consistent with what might be expected and confirm the validity of the approach used to represent two-phase flows, regardless of the time constants chosen to observe the physical phenomenon. On a small time scale, compressibility effects predominate, but eventually diminish for viscous fluids, returning to Laplace’s static law.

4. Conclusions

Simulating compressible two-phase flows requires solving several different problems: (i) choosing a physical model with accuracy and completeness properties, i.e., a model that accurately represents physical phenomena at all spatial and temporal scales, (ii) consistent capillary terms where irrotational and solenoidal components are simultaneously present in the form of a Helmholtz–Hodge decomposition, (iii) the restoration, where applicable, of static equilibria that are strictly zero velocity, (iv) verification of the few known static and dynamic theoretical solutions, and finally (v) consistency of wave propagation in the presence of surface discontinuities and shocks.

The original formulation presented allows us to find results that are well established theoretically and experimentally for two-phase flows driven by capillary accelerations, such as Laplace’s static equilibrium without parasitic currents or the oscillation frequency of an elliptical drop. In particular, it reveals the fundamental role of the rotation component in the equilibrium between accelerations, notably capillary and gravitational. The case of the static equilibrium of a column of fluid in a capillary shows that Jurin’s law is insufficient to guarantee both the height of the meniscus and its cylindrical shape when the velocity of the liquid is strictly zero. The discrete mechanics established for all types of compressible and incompressible flows is based on the conservation of acceleration and thus eliminates any interpolation of quantities, such as density, that exist in classical formulations. The order-of-magnitude analysis of viscous, capillary, and compression effects shows that these phenomena are closely related given the small spatial dimensions of capillary flows. Under conditions where compressibility plays an important role, the pressure obtained differs considerably from static equilibrium values, as shown by the unstable pressure evolution in a drop subjected to capillary acceleration.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hirt, C.; Nichols, B. Volume of Fluid (VOF) method for the dynamics of free boundaries. J. Comput. Phys. 1981, 39, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popinet, S. Numerical Models of Surface Tension. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2018, 50, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethian, J.; Smereka, P. Level Set Methods for Fluid Interfaces. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2003, 35, 34–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trontin, P.; Vincent, S.; Estivalezes, J.; Caltagirone, J. A subgrid computation of the curvature by a particle/level-set method. Application to a front-tracking/ghost-fluid method for incompressible flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2012, 231, 6990–7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottet, G.H.; Maire, E.; Milcent, T. Level Set Methods for Fluid-Structure Interaction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, J.; Koth, D.; Zemack, C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 100, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltagirone, J.P. An alternative to the Navier-Stokes equation based on the conservation of acceleration. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 978, A21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltagirone, J.P. Modeling capillary flows by conservation of acceleration and surface energy. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2024, 171, 104672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caltagirone, J.P. Towards a Unification of the Laws of Physics in Classical Fields Theory; ISTE; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Caltagirone, J.P. Application of discrete mechanics model to jump conditions in two-phase flows. J. Comput. Phys. 2021, 432, 110151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1865, 155, 459–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liénard, A. Champ électrique et magnétique produit par une charge électrique concentrée en un point et animée d’un mouvement quelconque. L’Éclair. Électr. 1898, 16, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Caltagirone, J.P. Extension of Galilean invariance to uniform motions for a relativistic equation of fluid flows. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 013103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koffi Bi, D.A.; Tavares, M.; Chénier, E.; Vincent, S. Accuracy and convergence of the curvature and normal vector discretizations for 3D static and dynamic front-tracking interfaces. J. Comput. Phys. 2022, 461, 111197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, M.; Koffi-Bi, D.A.; Chenier, E.; Vincent, S. A two-dimensional second order conservative front-tracking method with an original marker advection approach based on jump relations. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2020, 27, 1550–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, D.; Davidson, M.; Rudman, M. An Analysis of Parasitic Current Generation in Volume of Fluid Simulations. Appl. Math. Model. 2006, 30, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, F.; van Wachem, B. Numerical time-step restrictions as a result of capillary waves. J. Comput. Phys. 2015, 285, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmann-Schwarzbach, Y. The Noether Theorems; Invariance and Conservations Laws; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranocha, H.; Ostaszewski, K.; Heinisch, P. Discrete Vector Calculus and Helmholtz Hodge Decomposition for Classical Finite Difference Summation by Parts Operators. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quéré, D.; Azzopardi, M.J.; Delattre, L. Drops at Rest on a Tilted Plane. Langmuir 1998, 14, 2213–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambau, T. Montée Capillaire, Tubes et Grains. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paris-Diderot—Paris VII, Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, A. Simulation Numérique de la Montée Capillaire en Espace confiné, en vue de L’Application à des Procédés D’Élaboration de Matériaux Composites par Imprégnation Non-Réactive ou réactive. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Delannoy, J. Les Surprises de la Montée Capillaire. Ph.D. Thesis, Sorbonne Université, Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.