1. Introduction

Natural or free convection within cavities has been extensively studied due to its fundamental importance in engineering applications such as electronic cooling, solar collectors, building insulation, and thermal energy storage systems (Bergman [

1] and Bejan [

2]). The convective motion in a cavity is primarily driven by buoyancy forces arising from temperature gradients along the walls, which induce complex flow and thermal patterns depending on the geometry, boundary conditions, and fluid properties. Numerous studies have investigated natural convection (NC) in square, rectangular, and cylindrical cavities under various thermal conditions. For instance, Rahman et al. [

3] numerically analyzed MHD free convection heat and mass transfer along a vertical porous surface within a rotating system with a tempted magnetic field. Cesini et al. [

4] examined NC heat transport from a horizontal cylinder blocked by a rectangular cavity employing numerical and experimental techniques. The results indicate that heat transport escalates with the Ra and reaches its peak at a reduced aspect ratio (AR). Additionally, thermal stratification has been shown to play a significant role in altering NC flow behaviors, either suppressing or enhancing convective circulation and thereby affecting HT rates within enclosed domains (Zoubir et al. [

5]).

Unsteady natural convection (UNC) plays a pivotal role in thermal–fluid systems where transient temperature variations give rise to time-dependent flow structures. Unlike steady convection, unsteady behavior can lead to oscillatory, periodic, or even chaotic flow patterns, which strongly influence HT performance and system stability. Foundational work by Patterson and Imberger [

6] introduced a groundbreaking concept for characterizing unsteady states, presenting a scaling analysis for UNC in a differentially heated cavity with uniform wall temperatures. Lei et al. [

7] investigated transient NC in a water-filled isosceles triangular cavity with bottom heating, providing detailed insights into the stages of flow evolution, the influence of the Grashof number (Gr), and the resulting HT characteristics. Rahaman et al. [

8] analyzed transient convective HT within a stratified air-filled enclosure due to uniformly low temperature at the top. They revealed time dependent flow characteristics under a stratified clause. In a related study, Rahaman et al. [

9] investigated UNC in a stratified trapezoidal cavity heated from below. Their study revealed that the initial stratification strongly influences the onset and evolution of convective motion, affecting both flow structures and thermal distributions. The results demonstrated that stronger stratification delays the development of convection and reduces HT rates, highlighting the critical role of initial density gradients in controlling transient convective behavior. Later, Rahaman et al. [

10] numerically examined UNC and HT in a thermally stratified trapezoidal cavity, confirming that stratification intensity significantly influences HT rates and emphasizing its critical role in controlling transient convective behavior and thermal performance in confined enclosures.

Understanding NC in different cavity configurations, such as square, triangular, rectangular, cylindrical, and many others, significantly affects the flow structures, thermal distribution, and overall HT performance. Variations in cavity shape influence the formation of boundary layers, circulation patterns, and the onset of flow instabilities, thereby controlling the efficiency of convective transport. Bouafia and Daube [

11] investigated NC about a square-shaped solid body situated inside a rectangular cavity subjected to large temperature gradients, showing that strong thermal gradients significantly affect flow structure and enhance HT around the solid body. Roshani et al. [

12] highlighted the significance of buoyancy-driven convection in triangular cavities, showing that barrier placement and geometric configuration critically affect circulation patterns and HT characteristics. Das and Basak [

13] conducted comprehensive CFD- and heatline-based analyses of NC in square and triangular cavities equipped with distributed and discrete solar heaters, providing valuable insights into the influence of heating configuration on thermal performance. Karatas and Derbentli [

14] examined NC in rectangular cavities with differential heating and a time-periodic boundary condition, revealing that periodic temperature variations substantially modify flow structures and thermal distributions, resulting in oscillatory convection patterns. Charles et al. [

15] examined turbulent NC in a rectangular cavity and found that turbulence markedly enhances HT relative to laminar flow while generating complex, highly unsteady velocity and temperature fields. Berdnikov et al. [

16] studied the development of transient NC inside a rectangular cavity subjected to abrupt heating of a vertical wall, demonstrating that rapid thermal forcing produces transient flow structures and dynamic temperature fields, leading to complex circulation patterns. Fichera et al. [

17] developed a model for NC within a rectangular cavity where the vertical walls are differentially heated, highlighting that wall temperature differences strongly dictate circulation patterns and thermal boundary layers. Farahani et al. [

18] investigated NC in a tall rectangular cavity containing an oscillating and rotating cylinder, revealing that cylinder motion and rotation significantly alter flow structures and thermal distribution, with oscillation frequency, rotation speed, and cylinder position strongly influencing convective patterns and HT rates. Islam et al. [

19] numerically examined magnetohydrodynamic free convection in a rectangular enclosure containing a corner-mounted heater and a centrally placed triangular obstacle, demonstrating that increasing the Hartmann number suppresses buoyancy-driven circulation and reduces HT. Their results further showed that the triangular obstacle alters flow pathways, intensifies localized thermal gradients, and influences the overall Nusselt number depending on its orientation.

Square enclosures are extensively employed as benchmark models in NC studies owing to their straightforward geometric configuration and clearly prescribed boundary conditions. They enable comprehensive theoretical, numerical, and experimental analyses of complex thermo-fluid phenomena such as boundary layers formation, temperature stratification, hydrodynamic instabilities, and the transition between laminar and turbulent flow transitions. De Vahl Davis [

20] conducted a classical benchmark numerical study of air-filled square cavities, providing accurate steady-state solutions over Ra extending from 10

3 to 10

6. Pesso and Piva [

21] extended the investigation to low-Prandtl-number fluids with large density variations, highlighting the limitations of the Boussinesq approximation and offering a more realistic representation of thermally driven flows. Hakeem et al. [

22] analyzed NC inside a square enclosure with thermally active plates under diverse boundary conditions, demonstrating the strong influence of the plate position and temperature on HT characteristics. Choi and Kim [

23] carried out a comparative study of various thermal lattice Boltzmann models for simulating NC, assessing their predictive accuracy and numerical stability across a range of Ra. Butler et al. [

24] experimentally examined NC from a heated horizontal cylinder positioned within a differentially heated square enclosure and revealed that the interaction between the cylinder and the cavity walls significantly modifies flow structures and enhances local HT. Saravanan [

25] numerically investigated NC in a square cavity incorporating internal heat-generating baffles. The study analyzed the impacts of baffle length, position, and heat generation rate on the flow structure and thermal behavior in the cavity.

Rectangular cavities have been widely studied due to their geometric simplicity and direct relevance to numerous engineering applications. A substantial body of research has examined NC in rectangular cavities under various thermal boundary conditions. Dalal and Das [

26] numerically investigated NC inside a rectangular domain heated uniformly from the base and cooled from the top and the sidewalls. Their study explored the impact of the Ra and AR on flow patterns and HT performance. Nithyadevi et al. [

27] numerically examined NC within a rectangular domain with partially active sidewalls to analyze the effects of differential heating on flow and HT characteristics. Khezzar et al. [

28] investigated NC in sloped 2D rectangular cavities to assess the influence of the inclination angle and Ra on flow structure and HT performance. Their outcomes illustrated that cavity inclination significantly alters the flow circulation patterns and thermal field symmetry. Hatami [

29] numerically investigated the NC of nanofluids inside a rectangular domain comprising heated fins to examine their influence on flow and HT characteristics. The study revealed that the existence of fins significantly augments convective circulation and HT by increasing the surface area and promoting stronger fluid mixing. Miroshnichenko and Sheremet [

30] provided an inclusive review of turbulent NC and HT in rectangular cavities, utilizing both experimental and numerical approaches. Their study highlighted that turbulence significantly enhances convective HT, particularly at high Ra values, by promoting vigorous mixing and reducing thermal boundary layer thickness. Jobby et al. [

31] conducted an inclusive review on free convection HT inside parallel and inclined rectangular cavities with internal substances under numerous heating conditions. They reported that enclosure inclination, AR, and heat source location strongly influence flow circulation and thermal performance, with moderate inclination angles enhancing HT.

Entropy, a fundamental thermodynamic property, quantifies the degree of disorder within a system and represents the portion of energy that is unavailable for performing useful work. In fluid flow and HT processes, higher entropy formation signifies increased irreversibility and energy loss. Therefore, minimizing EG is indispensable for enhancing the overall thermal performance of systems. Bejan [

32] first introduced the concept of EG minimization to improve energy efficiency in various transport processes by analyzing the loss of usable energy caused by irreversibility. Shuja et al. [

33] performed an entropy analysis to evaluate the irreversibility ratio at different positions of a heat-generating solid body within a cavity and reported that both HT and EG attain their maximum values when the solid body is centrally located. Ilis et al. [

34] investigated EG in rectangular enclosures of varying ARs while maintaining a constant area, employing isotherms, streamlines, and local EG distributions to provide practical insights for reducing entropy inside rectangular enclosures. Varol et al. [

35] examined conjugate NC, HT, and fluid flow irreversibilities in a cavity, highlighting the complex interactions between thermal and fluid frictional effects. Oliveski et al. [

36] conducted a numerical study on EG within rectangular cavities subjected to NC induced by temperature variations on vertical walls, revealing that total EG increases linearly with both AR and the irreversibility coefficient, and exponentially with the Ra. Furthermore, AR and Ra significantly affect the

Beavg and viscous effect. Bouabid et al. [

37] numerically analyzed transient NC and EG in a sloped rectangular domain filled with air, showing that EG increases with the Gr, AR, and irreversibility distribution ratio, exhibiting oscillatory behavior at higher Gr and steady-state characteristics at lower Gr. Singh et al. [

38] investigated thermal mixing and EG in tilted square cavities using the Galerkin finite element method under varying Pr and Ra numbers, finding that flow structure and HT are strongly influenced by cavity corners, circulation patterns, and inclination angles. Similarly, Shavik et al. [

39] analyzed NC and EG within a square cavity at inclination angles ranging from 0° to 60°, demonstrating distinct differences between HT and fluid friction (FF) irreversibilities through entropy maps and

Beavg distributions across various Ra. Salari et al. [

40] numerically examined EG associated with NC in rectangular cavities featuring circularly rounded corners and reported that corner curvature significantly alters flow topology and thermal gradients, thereby influencing both local and global irreversibility. Sheremet et al. [

41] examined NC and EG in a nanofluid-filled square cavity featuring sinusoidal wall heating. Their results indicated that increasing Ra, temperature amplitude, and wave number enhance nanofluid flow and improve HT, mass transfer, and EG. The impact of AR and Gr on UNC, HT, and EG in trapezoidal cavities was investigated by Rahaman et al. [

42], who found that increasing AR decreases the cavity’s thermal efficiency. In a subsequent study, Rahaman et al. [

43] carried out a computational investigation of UNC, HT, and EG in a trapezoidal enclosure filled with thermally stratified water, characterized by a heated bottom surface, stratified inclined surfaces, and a cooled upper surface.

Although NC in square and rectangular cavities has been widely examined, the thermal behavior of configurations featuring a uniformly heated base, a cooled upper surface, and stratified vertical side surfaces filled with stratified air remains insufficiently unexplored. In particular, the transient bifurcation dynamics and the associated thermodynamic performance have not been comprehensively addressed in the existing literature. Thermal stratification along the vertical walls of such cavities develops due to temperature gradients created by differential heating, leading to layered fluid motion and buoyancy-driven convection. This behavior is of significant relevance in various engineering and environmental applications, such as building and room ventilation, solar thermal energy storage, and atmospheric or environmental flow analyses. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study constitutes one of the first comparative investigations aimed at assessing the thermal performance of square and rectangular cavities with identical surface areas and boundary conditions, wherein only the cavities’ height and length are varied. The primary objective of this study is to explore the influence of Ra on flow behavior and bifurcations, focusing specifically on determining the critical Ra associated with transitions, including pitchfork and Hopf bifurcations, as well as the emergence of chaotic flow patterns within air-filled rectangular cavity. Furthermore, the study evaluates the Nuavg, Savg, Beavg, and ECOP for both rectangular and square cavities under identical boundary conditions, surface area, and working fluid. The outcomes of this research offer substantial insight into the effects of geometric configuration on thermal efficiency and bifurcation characteristics in thermally stratified enclosures. The numerical results have been thoroughly validated against previously published data to confirm the credibility and precision of the current findings.

2. Physical Model

The present study primarily focuses on examining the UNC, bifurcation behavior, and HT characteristics in a rectangular cavity through 2D numerical simulation. A comparative analysis is subsequently conducted to evaluate the Nu

avg,

Savg,

Beavg, and overall thermal performance between square and rectangular cavities.

Figure 1 depicts a schematic of the physical domain of (a) rectangular and (b) square cavities, along with the associated boundary conditions. The aspect ratio of the cavity is defined as AR =

H/

L, where

H and

L denote the cavity height and length, respectively. In the present study, the square cavity corresponds to AR = 1.0, while the rectangular cavity has an aspect ratio of AR = 1.563 (with the same surface area as the square cavity). Furthermore, a comparative analysis of thermal performance between square and rectangular cavities is performed under identical boundary conditions and working fluid to elucidate the influence of the geometric configuration on system behavior. The bottom wall of the cavity is maintained at a constant high temperature, denoted as

Th, while the top wall is kept at a lower constant temperature,

Tc. The vertical walls are subjected to thermal stratification, represented by

Ti. The working fluid is air with a Pr of 0.71, initially assumed to be linearly stratified. The thermophysical characteristics of the stratified air are summarized in

Table 1. All walls of the cavity are rigid and satisfy the no-slip velocity condition.

The analysis of the UNC of stratified air within rectangular and square enclosures is performed utilizing a 2D computational approach based on the coupled Navier–Stokes and energy equations under the Boussinesq approximation, as follows (refer to Hossain et al. [

44]):

The dimensional boundary conditions are as follows:

The following are the normalized variables:

Here,

u,

v,

x,

y,

p,

τ, and

θ represent the non-dimensional forms of

U,

V,

X,

Y,

P,

t, and

T, respectively. Two results controlling parameters within the cavities,

Pr and

Ra, are defined as follows (for additional details, see [

10]):

The non-dimensional form of Equation (1) becomes (refer to [

45])

The following are the non-dimensional boundary conditions:

The Nu

avg on the horizontal and vertical walls is defined as follows (see Rahaman et al. [

46,

47] for further details):

Entropy generation represents the overall measure of thermodynamic irreversibility within a system. In an NC arrangement, the primary sources of thermodynamic irreversibility can be traced back to two mechanisms: HT and FF. Local EG associated with these processes can be articulated in the following manner (refer to [

47] for details):

where

Sθ and

Sf correspond to the local EG caused by the HT and the FF. The irreversible distribution ratio, denoted as φ, is defined as follows (refer to Varol et al. [

35] for details):

The local EG within the enclosures, characterized as

Sl, defined as the sum of

Sθ and

Sf, is as follows (refer to [

47]):

The local Bejan number (

Bel) is defined in the following manner (refer to [

42]):

In convective systems, entropy is produced primarily due to temperature gradients (thermal irreversibility) and viscous dissipation (FF irreversibility). A higher average entropy generation (

Savg) indicates greater destruction of available energy and reduced thermodynamic efficiency of the system. The average Bejan number (

Beavg) provides a quantitative measure of the relative contribution of thermal irreversibility compared to total EG within a convective system. The

Savg and the

Beavg are characterized by the following (refer to [

42] for details):

The ecological coefficient of performance (ECOP), which serves as an indicator for assessing the thermal performance within the domain, is defined as follows (for additional details, see [

46]):

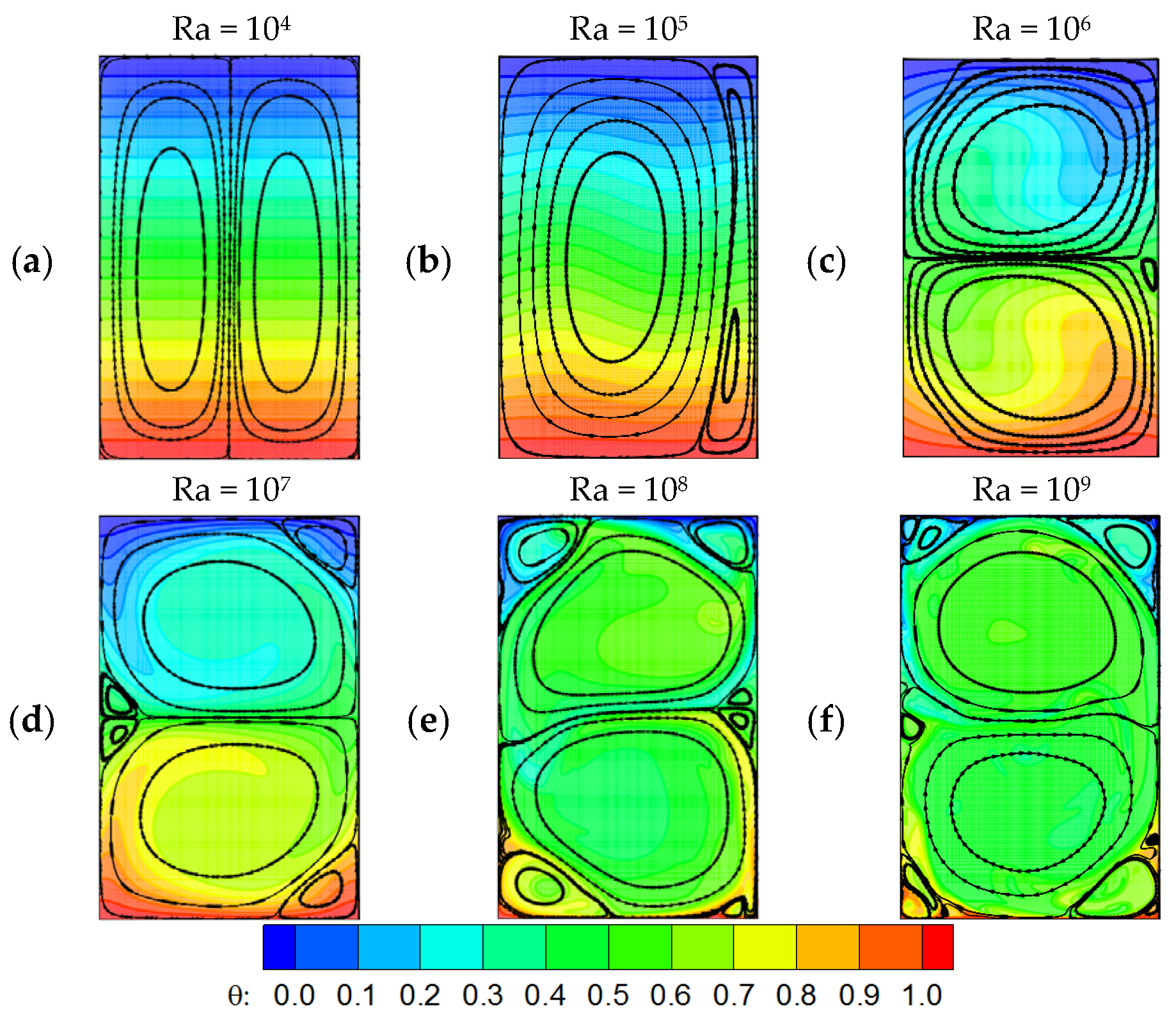

5. Heat Transfer

Although streamlines and isotherms do not directly quantify HT rates at the cavity boundaries, they provide valuable qualitative information about the internal flow structure and the governing physical mechanisms. The average Nusselt number (Nu

avg) quantifies the enhancement of HT at a heated or cooled surface due to convection relative to pure conduction. Physically, it reflects how effectively the flow field transports thermal energy away from the boundary.

Figure 9 illustrates the computed time series of the Nu

avg at the bottom, top, left, and right walls. At the initial state, the temperature distributions of the fluid remain closely aligned with the boundary temperatures of the bottom, top, and vertical walls.

For lower Ra, HT is primarily governed by conduction; therefore, the discussion emphasizes higher Ra values, where the flow changes over from steady to chaotic regime. Initially, because of the thermally stratified air, the HT is minimal; however, during the transitional stage, the stratification effect becomes weakened, and the HT rate increases with rising Ra. At the FDS, the flow remains at a steady state for Ra ≤ 3 × 106, becomes periodic at Ra = 4 × 106, and sustains periodic behavior up to Ra = 9 × 107. Beyond this, at Ra = 2 × 108, the periodicity breaks down, and the flow shifts to a chaotic state.

The HT rate increases monotonically at the bottom (

Figure 9a), top (

Figure 9b), and right vertical (

Figure 9c) walls with increasing Ra. However, an exception is observed at the right vertical wall for higher Ra values, as illustrated in

Figure 9d. At the elevated Ra, the intensity of fluid motion within the cavity increases, leading to the upward (ascending) movement of heated air along the left vertical wall and the downward (descending) movement of cooled air along the right vertical wall. As a result, the HT rate on the left vertical wall becomes significantly higher than that on the right wall.

6. Thermal Performance Analysis for Square and Rectangular Cavities

This study investigates UNC, HT, and bifurcation phenomena within a rectangular cavity, along with a comparative analysis of the Nuavg, Savg, Beavg, and thermal performance between square and rectangular cavities filled with thermally stratified air. In both cases, identical boundary conditions are applied, with variations introduced only in the cavity dimensions (length and width). The flow transition behavior of the square cavity is considered beyond the scope of the current study.

Figure 10 illustrates the variation in Nu

avg at the bottom wall for both square and rectangular cavities over a Ra range from 10

5 to 10

8. As observed, Nu

avg increased consistently with increasing Ra for both geometries, indicating the progressive enhancement of convective HT as buoyancy forces intensify. At the lowest Ra = 10

5, the bottom of the square cavity exhibits a noticeably higher Nu

avg of 5.79 compared to 3.24 for the rectangular cavity, signifying that under weak convection conditions, the square geometry facilitates more effective HT. At Ra = 5 × 10

5, Nu

avg rises to 6.15 in the square cavity and 5.89 in the rectangular cavity. When Ra increases to 10

6, Nu

avg rises to 7.28 in the square cavity and 7.22 in the rectangular cavity, suggesting that the difference between the two configurations becomes insignificant. For Ra = 5 × 10

6, Nu

avg further increases to 14.37 in the square cavity and 13.99 in the rectangular cavity. A substantial enhancement is observed at Ra = 10

7, where Nu

avg reaches 22.00 for the square cavity and 20.10 for the rectangular cavity. At Ra = 5 × 10

7, the values rise to 37.02 and 33.95, respectively. At the Ra of 10

8, Nu

avg attains 50.79 in the square cavity and 41.79 in the rectangular cavity. Overall,

Figure 10 demonstrates that the bottom of the square cavity consistently exhibits slightly higher Nu

avg values than the rectangular cavity. Notably, at Ra = 10

8, the HT rate at the bottom of the square cavity is approximately 17.72% higher than that in the rectangular cavity, confirming the superior thermal performance of the square configuration under strong convective conditions.

Figure 11 presents the variation in the Nu

avg for the square and rectangular cavities over an Ra ranging from 10

5 to 10

8. As expected, Nu

avg increases with increasing Ra for both geometries, demonstrating the progressive enhancement of convective HT as buoyancy forces become more dominant. At the lowest Ra = 10

5, the square cavity exhibits a higher Nu

avg of 5.33 compared to 3.69 for the rectangular cavity, indicating that the square geometry shows stronger fluid circulation under weak convection conditions. At Ra = 5 × 10

5, Nu

avg increases to 6.60 in the square cavity and 5.60 in the rectangular cavity. As Ra reaches to 10

6, Nu

avg rises to 8.01 in the square cavity and 7.27 in the rectangular cavity, showing that both enclosures exhibit comparable convective behavior, although the square configuration remains marginally more effective. For Ra = 5 × 10

6, Nu

avg further increases to 13.99 in the square cavity and 10.80 in the rectangular cavity. At Ra = 10

7, Nu

avg increases to 15.36 for the square cavity and 14.49 for the rectangular cavity. At Ra = 5 × 10

7, the value increases to 20.65 and 25.90, respectively. However, at the highest Ra = 10

8, a distinct reversal in trend is observed: the rectangular cavity attains a significantly higher Nu

avg of 36.97, whereas the square cavity records a lower value of 25.94. This behavior can be attributed to the intensified buoyancy-driven flow in the rectangular enclosure. Consequently, at Ra = 10

8, the HT rate in the rectangular cavity is approximately 29.84% higher than that of the square cavity.

Figure 12 illustrates the variation in HT along the vertical walls for both square and rectangular cavities over a range of (Ra = 10

5–10

8). At Ra = 10

5, the left vertical wall (LVW) of the square cavity exhibits Nu

avg of 4.90, while the rectangular cavity shows a slightly lower value of 4.12. Similarly, at the right vertical wall (RVW), the square cavity exhibits a Nu

avg of 4.97 compared to 4.21 for the rectangular configuration. At Ra = 5 × 10

5, Nu

avg at the LVW increases to 5.20 in the square cavity and 5.45 in the rectangular cavity, while the corresponding values at the RVW rise to 5.18 and 5.51, respectively. As Ra increases to 10

6, the Nu

avg at the LVW reaches 5.47 for the square cavity and 6.86 for the rectangular cavity, whereas at the RVW the values increase to 5.57 and 6.93, respectively. For Ra = 5 × 10

6, further enhancement in HT is observed, with Nu

avg at the LVW increasing to 8.47 in the square cavity and 8.09 in the rectangular cavity, while the corresponding RVW values become 6.01 and 7.73, respectively. At Ra = 10

7, the LVW Nu

avg of the square cavity increases to 11.21, compared to 9.33 for the rectangular cavity, whereas at the RVW the respective values are 6.24 and 8.52. At Ra = 5 × 10

7, Nu

avg at the LVW rises markedly to 17.98 in the square cavity and 29.81 in the rectangular cavity, while at the RVW the corresponding values increase to 8.29 and 12.01, respectively. At the highest Ra = 10

8, a sharp enhancement in HT is observed, particularly in the rectangular cavity. On the LVW, Nu

avg reaches 50.29 in the rectangular configuration, whereas the square cavity records a considerably lower value of 23.74. On the RVW, the square cavity attains a Nu

avg of 10.79, while the rectangular cavity reaches 14.04. As shown in

Figure 12a,b, Nu

avg increases almost linearly for both cavities, indicating the strengthening of convective HT with buoyancy. The RVW (

Figure 12b) consistently exhibits higher HT rates in the rectangular cavity than in the square cavity. On the other hand, at the LVW (

Figure 12a), both geometries display similar HT behavior at lower Ra values. However, at Ra = 10

8, a pronounced enhancement occurs in the rectangular cavity, where the Nu

avg is approximately 52.79% higher than that of the square cavity. Although identical thermal boundary conditions are imposed on both vertical walls in the rectangular cavity, the heat transfer rate becomes significantly higher at the LVW than at the RVW at Ra = 10

8. This disparity arises from the development of asymmetric flow structures as buoyancy forces dominate the flow field. At such high Ra, the flow transitions from a relatively symmetric conduction–convection regime to a strongly convection-driven circulation.

The primary clockwise (or counterclockwise) recirculating cell intensifies and causes warmer fluid to ascend preferentially along one vertical wall, typically the left wall in the present configuration. This results in a thinner thermal boundary layer and a steeper temperature gradient along that wall, which directly enhances the Nuavg. In contrast, the opposite wall experiences descending colder fluid, which forms a thicker boundary layer with weaker temperature gradients, leading to reduced HT.

Figure 13 illustrates the variation in

Savg and

Beavg for square and rectangular cavities over a range of Ra (Ra = 10

5 to 10

8). At Ra = 10

5, the square cavity exhibits

Savg of 72.4, which is slightly higher than 64.2 for the rectangular cavity. At Ra = 5 × 10

5,

Savg increases to 100.50 in the square cavity and 106.60 in the rectangular cavity. As Ra increases to 10

6, both cavities show a noticeable rise in

Savg, reaching 122.3 for the square and 139.5 for the rectangular cavity, indicating that convective motion becomes stronger in both enclosures. For Ra = 5 × 10

6,

Savg further increases to 560.70 in the square cavity and 601.20 in the rectangular cavity. At Ra = 10

7,

Savg increases sharply to 939.5 for the square cavity and 999.7 for the rectangular cavity. At Ra = 5 × 10

7, the values increase to 2000.30 and 3400.20, respectively. A further rise in Ra to 10

8 leads to a dramatic increase in

Savg, reaching 2997.7 for the square cavity and 4940.3 for the rectangular cavity. The higher

Savg observed in the rectangular cavity at elevated Ra values signifies more intense convective circulation and greater irreversibility due to thermal and viscous effects. As depicted in

Figure 13a,

Savg values for both cavities remain closely aligned up to Ra = 10

7. However, at Ra = 10

8 the

Savg of the rectangular cavity becomes significantly higher, approximately 39.32% greater than that of the square cavity.

The variationa in the

Beavg are depicted in

Figure 13b for different Ra. At lower Ra = 10

5,

Beavg values are nearly identical for both cavities (0.99 for square and 0.98 for rectangular), indicating that HT irreversibility dominates over FF. As Ra increases,

Beavg gradually decreases, reaching 0.16 for the square cavity and 0.10 for the rectangular cavity at Ra = 10

8. This steady decline reflects the growing contribution of FF effects at higher buoyancy-driven flow intensities.

The ecological coefficient of performance (ECOP = Nuavg/Savg) serves as an indicator to measure the thermal performance within the simulation domain. A higher ECOP value corresponds to reduced EG, indicating enhanced thermodynamic efficiency, whereas a lower ECOP value replicates diminished HT performance because of the elevated thermal convection and associated irreversibilities.

Figure 14 demonstrates the variation in the ECOP for square and rectangular cavities at different Ra. At Ra = 10

5, the ECOP values are 0.0736 for the square cavity and 0.0575 for the rectangular cavity, indicating slightly superior thermal performance in the square configuration under low buoyancy conditions. At Ra = 5 × 10

5, ECOP decreases to 0.0681 for the square and 0.0556 for the rectangular cavity. As Ra increases to 10

6, ECOP decreases to 0.0655 for the square and 0.0521 for the rectangular cavity. For Ra = 5 × 10

6, ECOP decreases to 0.0404 for the square and 0.0283 for the rectangular cavity. With further increases in Ra, the ECOP continues to decline, reaching 0.0163 and 0.0145 at Ra = 10

7, and finally 0.0087 and 0.0075 at Ra = 10

8 for the square and rectangular cavities, respectively.

At Ra = 105, the square cavity demonstrates approximately 21.93% higher thermal efficiency than the rectangular cavity. At higher buoyancy levels, the thermal efficiency remains evident: 11.35% at Ra = 107 and 13.52% at Ra = 108. These findings reveal that the HT performance of the square cavity improves more prominently than that of the rectangular configuration, thereby identifying the square cavity as more thermally efficient under strong buoyancy-driven convection conditions.