Abstract

In this work, we present a theoretical and experimental investigation of the fluid–structure interaction between a freely moving wall and an oscillatory flow. Our objective is to elucidate the coupling mechanism between the fluid and the oscillating body that gives rise to reverse streaming, that is, the reversal in the rotation direction of the resulting steady vortices, and to apply this analysis to the case of a freely moving wavy wall. The flow is analyzed theoretically based on a two-dimensional model and an analytical solution is obtained using a perturbation method. Experimental results based on Particle Image Velocimetry are also presented, where an oscillatory flow generated by an electromagnetic force in an electrolyte layer drives a wavy wall floating on the surface. The results confirm the occurrence of reverse streaming and demonstrate that the flow dynamics depend on the density ratio between the freely moving solid and the fluid. The analytical solution qualitatively captures the streaming reversal observed in the experiments.

1. Introduction

A wide range of natural phenomena and engineering applications feature oscillatory flows confined by rigid or deformable boundaries. In such systems, the presence of dissipation together with nonlinear convective effects can produce a net transport of mass, momentum, and heat, even when the flow has zero mean. Examples of this kind of flows occur in physiological [1,2] and oceanographic phenomena [3,4], as well as in applications aimed at enhancing heat transfer [5,6].

The classical solution to Stokes’ second problem [7], which describes the motion generated when a flat plate oscillates harmonically in its own plane within a still viscous fluid, exemplifies the fundamental behavior of oscillatory viscous flow near a solid wall. In Stokes’ linear solution, wall oscillations produce an oscillatory flow of the same frequency, whose amplitude decays exponentially away from the wall. When nonlinear convective effects occur, such as those introduced by wall curvature, mass conservation gives rise to a transverse velocity component. Consequently, a secondary flow develops, comprising an oscillatory component at twice the driving frequency and a steady part, called steady streaming [8,9]. The latter is the generation of a steady recirculating motion that arises from a primary zero-mean oscillatory flow induced by vibrating boundaries or a pulsating pressure field. This phenomenon is a second-order effect produced by nonlinear Reynolds stresses within the unsteady boundary layer, which make the time-averaged oscillatory motion nonzero. Due to viscous effects, the resulting steady flow extends beyond the boundary layer, a defining feature of steady streaming [10].

Among the seminal works on steady streaming are the classic contributions of Rayleigh [11] and Schlichting [12,13]. Early studies of this phenomenon focused mainly on the oscillatory motion of cylinders [10,14,15] or spheres [16,17,18] immersed in a quiescent viscous fluid. More recently, interest in steady streaming has resurged due to its potential for a variety of microfluidic applications, including enhanced mixing [19,20] and manipulation of suspended particles [21,22]. Streaming flows induced by microbubbles have also been used for particle sorting [23]. In many of these applications, acoustic techniques play a central role in generating the streaming flow [24]. Moreover, the possibility of using streaming in biological processes or for bioengineering purposes has recently been proposed. For instance, fluid oscillations around a fixed cylinder in a microchannel can generate streaming eddies that can trap and levitate cells without direct contact [25]. Streaming flows have also been shown to be valuable for a wide range of tasks, including microparticle transport and manipulation, regulation of particle flocculation [26] and drug delivery [27,28].

Streaming generation, whether at the macroscopic or microscopic scale, has been mostly achieved using mechanical or acoustic transducers that induce oscillations of solid bodies or bubbles immersed in the fluid, or by employing pumps that drive the flow, for example, in microchannels. Electromagnetic approaches for generating streaming have also been investigated numerically, considering a quiescent layer of liquid metal disturbed by an external oscillating dipole magnet [29,30]. More recently, an alternative configuration involving a floating free moving magnet on an electrolyte layer subjected to an alternating electric current demonstrated, both experimentally and theoretically, the feasibility of inducing streaming [31]. Moreover, an unexpected effect was found, namely that the rotating sense of streaming vortices reverses with respect to the classical case of an oscillating cylinder. The coupling between the fluid and the free-moving body has been identified as the cause of reverse streaming.

The present work extends previous investigations by performing a two-dimensional theoretical analysis and an experimental study of the boundary-layer flow induced by a freely moving wavy wall in a viscous fluid. Considering boundary waviness provides an effective model for representing the perturbations introduced by wall roughness, which are particularly important at microscales [32,33,34]. First, assuming that the thickness of the Stokes layer is much smaller than the wavelength of the wall and the wall amplitude is smaller than the thickness of the Stokes layer, the axial viscous diffusion terms can be neglected, producing a formulation of the boundary-layer of the problem [35,36], in which the boundary condition of the free-moving wall is incorporated. Next, by applying a suitable coordinate transformation, an analytical solution is obtained using a perturbation method, under the assumption that the oscillation amplitude of the fluid is small relative to the wall wavelength, thus preventing boundary-layer separation [10]. The second-order solution captures the steady streaming flow and confirms that its direction can be reversed by varying the density ratio between the fluid and the wall. Furthermore, theoretical predictions about the streaming reversal, are qualitatively validated through experiments in which a freely moving wavy wall floating on an electrolyte layer is set into oscillatory motion by an electromagnetic force, leading to the formation of steady streaming vortices.

2. Formulation of the Problem

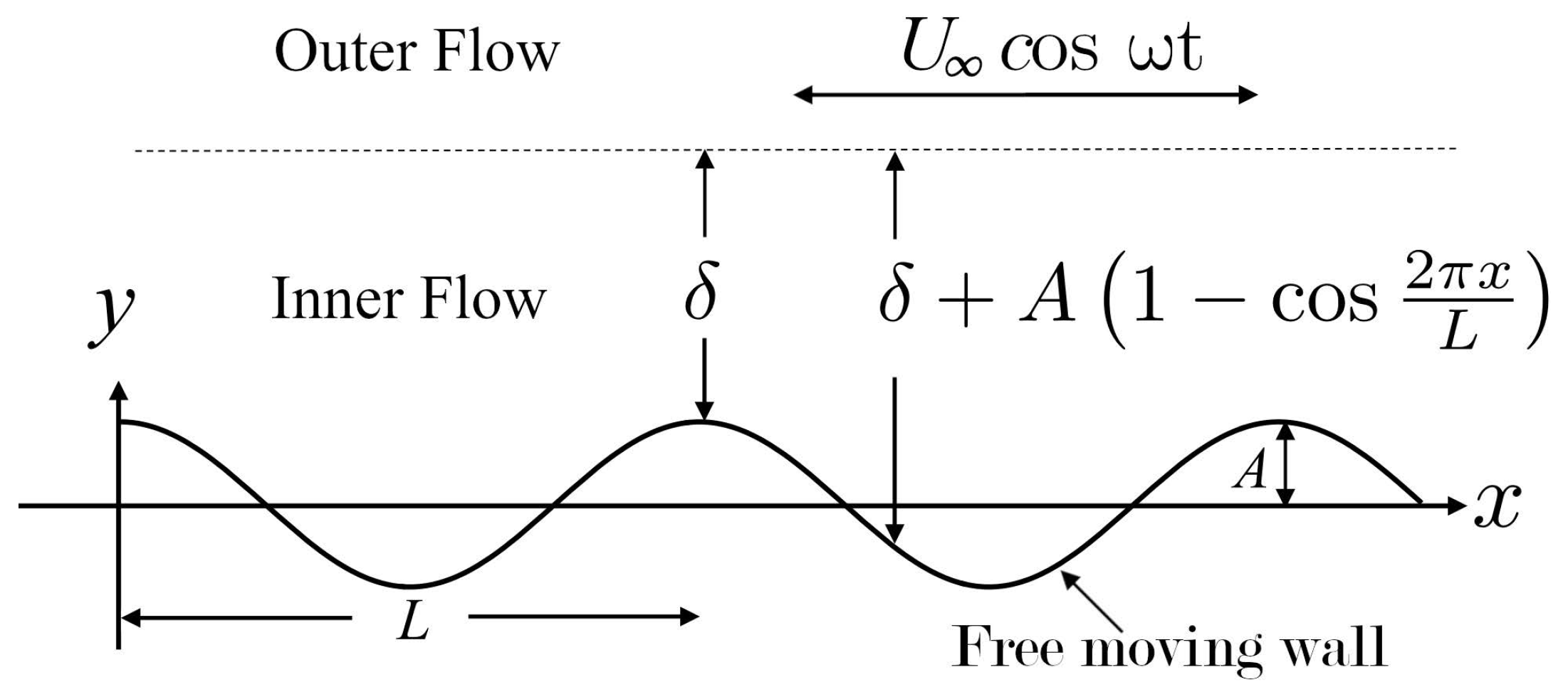

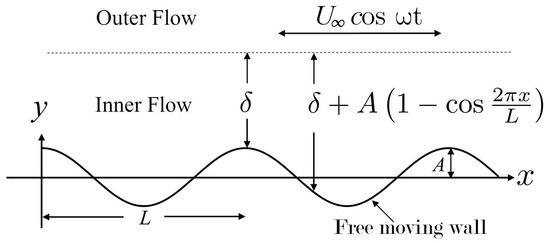

The theoretical framework and corresponding analytical solution developed here are based on the methodology outlined in [36]. We examine the oscillatory motion of an incompressible Newtonian fluid bounded by a freely moving, infinitely long wavy wall, whose shape is defined by the following equation:

where A and L are the amplitude and wavelength of the wall, while x is the stream-wise coordinate (see Figure 1). A harmonic pressure gradient applied in the x-direction drives the flow, producing oscillatory motion of the fluid about a zero mean far from the wavy wall. The axial velocity in this region is given by , where denotes the velocity amplitude and the angular frequency of oscillation. The motion of the incompressible Newtonian fluid is governed by the continuity equation,

and the momentum balance equation,

where the velocity and pressure fields are and p, respectively, while is the kinematic viscosity and is the mass density of the fluid. In two-dimensional flow, the continuity and momentum equations can be expressed as

where u and v denote the velocity components in the streamwise and transverse directions, respectively. The following dimensionless variables are then introduced:

where is the thickness of the Stokes layer, . In dimensionless terms, the continuity and momentum equations are

where , while, for simplicity, the over line in u, v and p has been removed. The parameter represents the ratio of the fluid displacement amplitude, , and the wall wavelength, L. To prevent boundary-layer separation, the small-amplitude of oscillation condition is assumed to hold, namely, [10]. Moreover, we assume that the Stokes layer thickness is much smaller than the wavelength of the wavy wall, i.e., . Under this condition, the axial viscous diffusion terms in Equations (9) and (10) can be neglected, since momentum transport by viscous diffusion is significantly stronger in the transverse direction than in the streamwise direction. Hence,

From Equation (12), we observe that . Therefore, the system simplifies to the following boundary-layer formulation:

which must satisfy both the matching condition for the streamwise velocity with the outer flow outside the boundary layer and the interaction with the free-moving wavy solid wall. At the free-moving wavy wall, the fluid is required to satisfy the no-slip boundary condition. Therefore, the boundary conditions that Equations (13) and (14) must satisfy are the following:

where denotes the dimensionless amplitude of the wall and and are the velocity components of the wall. When the following coordinate transformation is applied,

which corresponds to a transformation to a reference frame in which the wall is flat, the boundary conditions can be simplified. Under this transformation,

Figure 1.

Sketch of the 2D oscillatory boundary-layer flow over a free moving wavy wall, where the motion of the wall is determined by the fluid-wall interaction. A harmonic potential flow oscillates in the outer region above the wavy surface, generating a boundary-layer flow. is the boundary layer thickness, while A and L are the amplitude and wavelength of the wall, respectively.

In order to satisfy volumetric flow conservation, the waviness of the wall must be taken into account. At the crest, the boundary layer removes a fluid volume equal to , which corresponds to the flow deficit created by the boundary layer (see Figure 1). Because the flow is incompressible, the same deficit must appear in every transverse section, which yields the following balance equation

with denoting the velocity modification due to the wavy wall. In non-dimensional form, this becomes

Expressed in the coordinate frame in which the wall is rendered flat, the nondimensional outer flow becomes

where denotes the real part of the quantity in the brackets. On the other hand, the momentum balance equation satisfied by the outer flow is

which represents the pressure gradient required to balance the inertia in the outer flow. Using transformations (17) and (18) and substituting outer-flow expression (22) to eliminate the pressure, Equations (13) and (14) become

which must satisfy the following boundary conditions:

Note that the dimensionless amplitude is required to be less than one. This means that the wall amplitude is smaller than the thickness of the Stokes layer, , as shown in Figure 1. Otherwise, it would imply that the wall amplitude extends beyond the edge of the boundary layer, and the assumptions for the boundary layer problem, as stated by Equations (23)–(26), would not be valid.

To solve the system of equations, we must provide an explicit expression for the velocity of the wall ), since it serves as a boundary condition that directly shapes the motion of the fluid near the wall. For this purpose, we apply Newton’s second law to the wall, which gives the balance between its inertia and the external forces acting on it. The dimensionless governing equation for the motion of the wall is

where is the force vector field and is a dimensionless parameter that represents the ratio of wall density to fluid density . If , in such a way that , the inertia of the wall dominates, which corresponds to a fixed wall problem where the wall acceleration is zero. In turn, when , implies that the inertia of the wall is negligible, similar to the case where there is no wall and the potential flow remains. For this study, considering that experimental observations confirm that the movement of the wall occurs only horizontally (see Section 4), it is imposed that the solid wall is free to move only in the horizontal direction. Therefore, , and the horizontal component of the acceleration in Equation (27) has to be balanced by the drag force on the wall in this direction. Hence, considering the boundary layer approximation, Newton’s second law for the solid wall takes the form

where the term in parentheses on the right-hand side of (28) is the contribution of pressure and shear stress to the drag force on the wall [37].

3. Perturbation Solution

We now assume that the streamwise (u) and transverse (v) velocity components, together with the pressure and the horizontal wall velocity, can be expanded in a perturbation series with respect to the small parameter , for values of , that is,

where the first- and second order approximations are denoted, respectively, by subscripts 0 and 1.

3.1. First Order Approximation

By substituting Equations (29) and (30) into (24) and equating the coefficients of powers of , at we obtain

which must satisfy the following boundary conditions:

along with

where satisfies (22) with the boundary condition . This problem represents a generalization of Stokes’ second problem to the case of a freely moving wall [31]. The solution may be sought in the form

where is a constant that depends on the waviness of the wall and has to be determined. Introducing (37) into (33), we find the equation

which must satisfy and as . Here, , and the constant can be expressed as . The solution of (38) that satisfies the boundary conditions coupled with Newton’s second law for the wall (Equation (28)) is

In order to determine , (37) and (39) are substituted in (36), along with obtained from the solution of Equation (22). Once this is done, we find from (36)

where

In (40), and correspond to the contributions of pressure and shear stress to the drag force, respectively. Hence, the velocity component at first order in the streamwise direction is

or explicitly

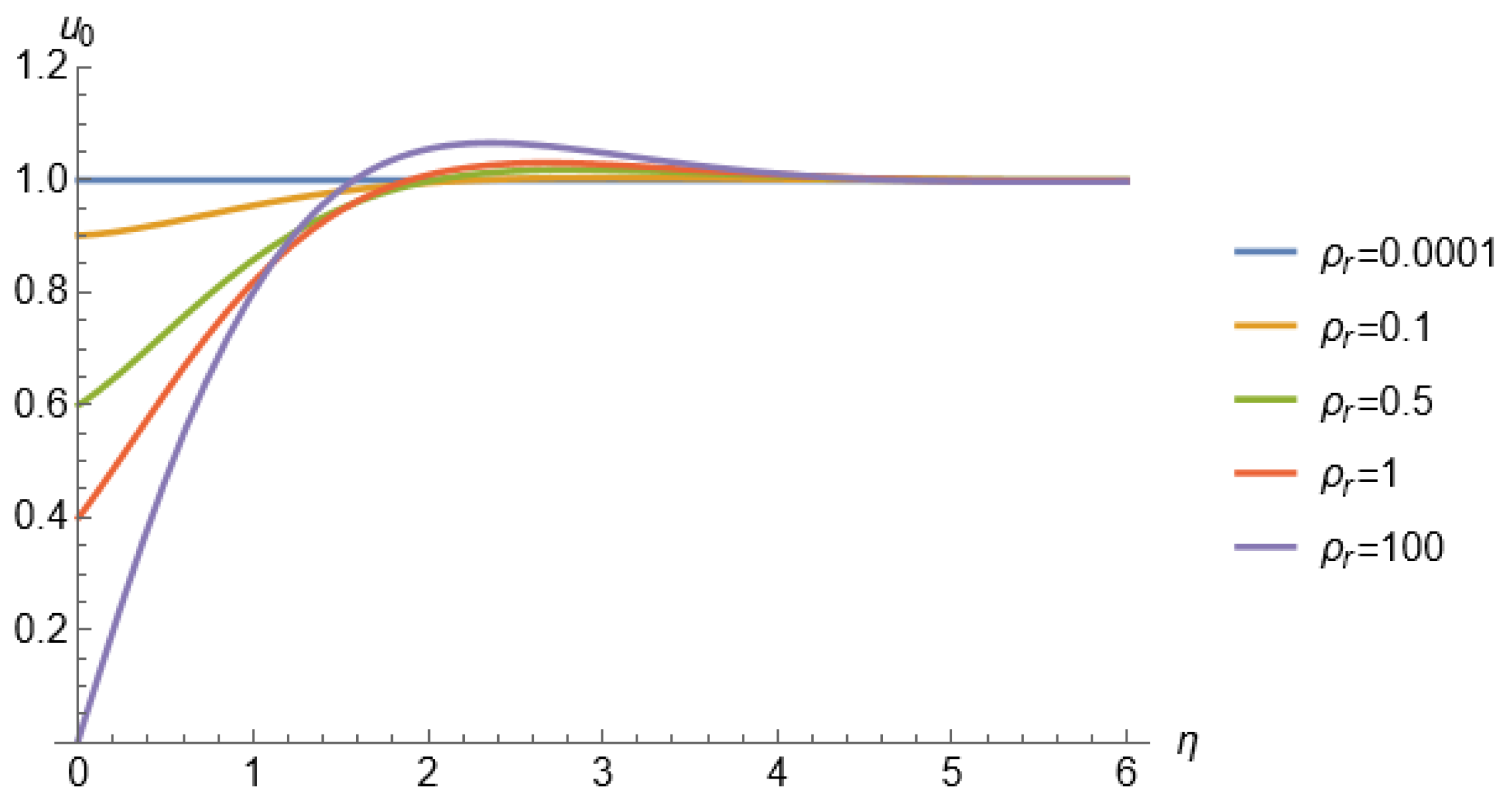

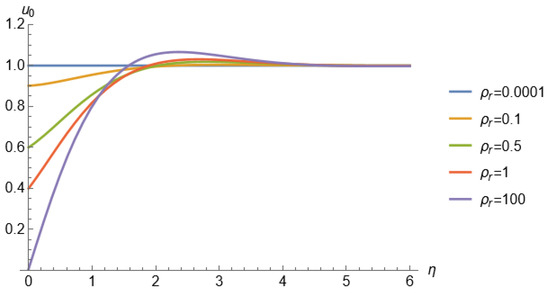

Figure 2 shows the normalized axial velocity as a function of the transverse coordinate , for a fixed time () and different values. When , the system approaches the limit of a vanishingly light wall (i.e., the density of the wall tends to zero), and the normalized axial velocity matches the amplitude of the potential flow throughout the entire domain. As increases (), a phase lag emerges between the fluid response and the wall motion, and the velocity at the wall () becomes non-zero. For large values of (), the system approaches the fixed-wall limit, corresponding to a boundary condition of zero-velocity at the wall.

Figure 2.

First order axial velocity as a function of the transversal coordinate for different values. and .

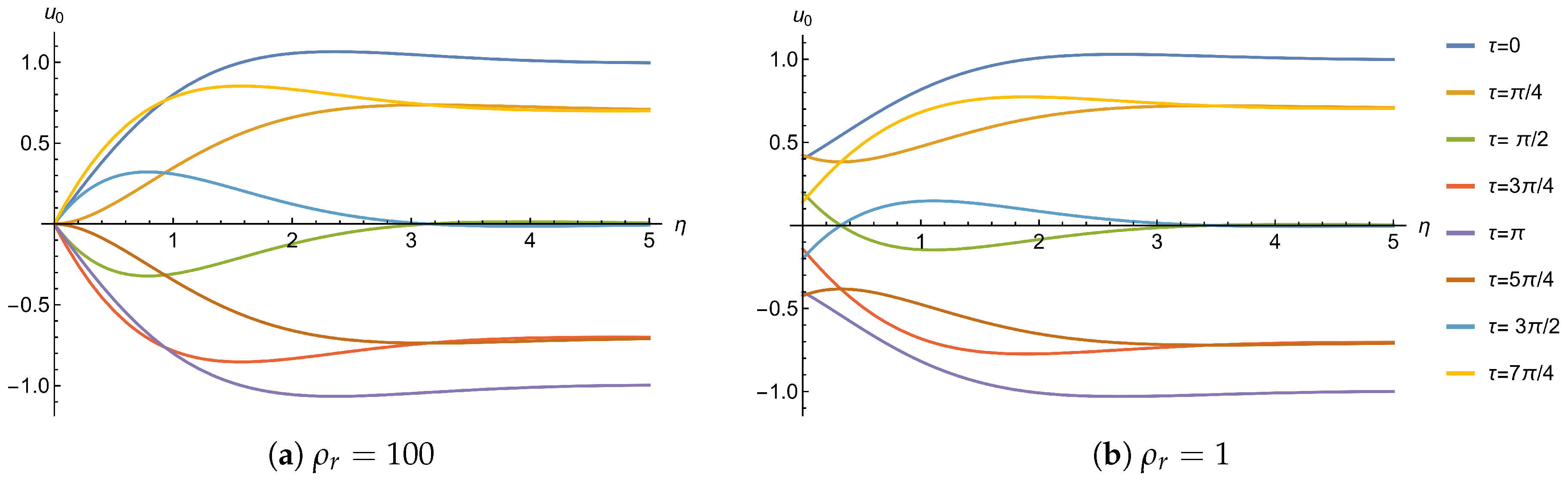

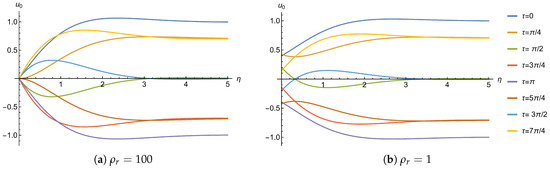

Figure 3 shows the axial velocity as a function of the transverse coordinate , at different times with and for two representative values of . The fixed-wall case (), is shown in Figure 3a. In this situation, the wavy wall has a density much larger than that of the fluid, so its inertia dominates and the wall effectively remains stationary (zero velocity). This case corresponds to the modified Stokes’ second problem [31]. Furthermore, Figure 3b presents the freely moving light wall case (), where displays a nonzero value at at every instant, matching the instantaneous wall velocity.

Figure 3.

First order axial velocity as a function of the transversal coordinate at different times with . (a) Fixed-wall case, . (b) Freely moving wall case, .

3.2. Second Order Approximation

Using Equations (24), (29) and (30), the equation governing for the () approximation is derived as

It is worth noting that the right-hand side of Equation (44) contains convective terms proportional to . Consequently, besides the oscillatory components at twice the fundamental frequency, the nonlinear terms also generate time-independent contributions responsible for the steady streaming flow. Taking this into account, can be written in the form

where the subscripts u and s refer, respectively, to the unsteady and steady contributions. The equations satisfied by and can be found by substituting (37), (43) and (45) in Equation (44). In fact, the steady contribution satisfies

where the over bar indicates conjugate complex quantities. As occurs in the classical steady streaming case [10,13], if condition (47) is imposed on the wall, it is not possible to satisfy condition (48) at infinity. Therefore, condition (48) must be relaxed by requiring to take a finite value as . The solution of Equation (46) satisfying the relaxed boundary conditions is

Taking the limit when the wall density tends to infinity (), Equation (49) reduces to the corresponding expressions for the classical streaming case with a fixed wall [10,12,13]. Therefore, the steady velocity components parallel and transverse to the wall at second-order can be written, respectively, as

where satisfies the boundary condition at . In the classical case with a fixed plate the steady tangential velocity, , at the edge of the boundary layer () yields Rayleigh’s law of streaming [10,13], namely,

This steady velocity is originated by the Reynolds stresses related to oscillatory viscous flow [10]. In the case of a moving wall, the classical Rayleigh law of streaming is modified as follows:

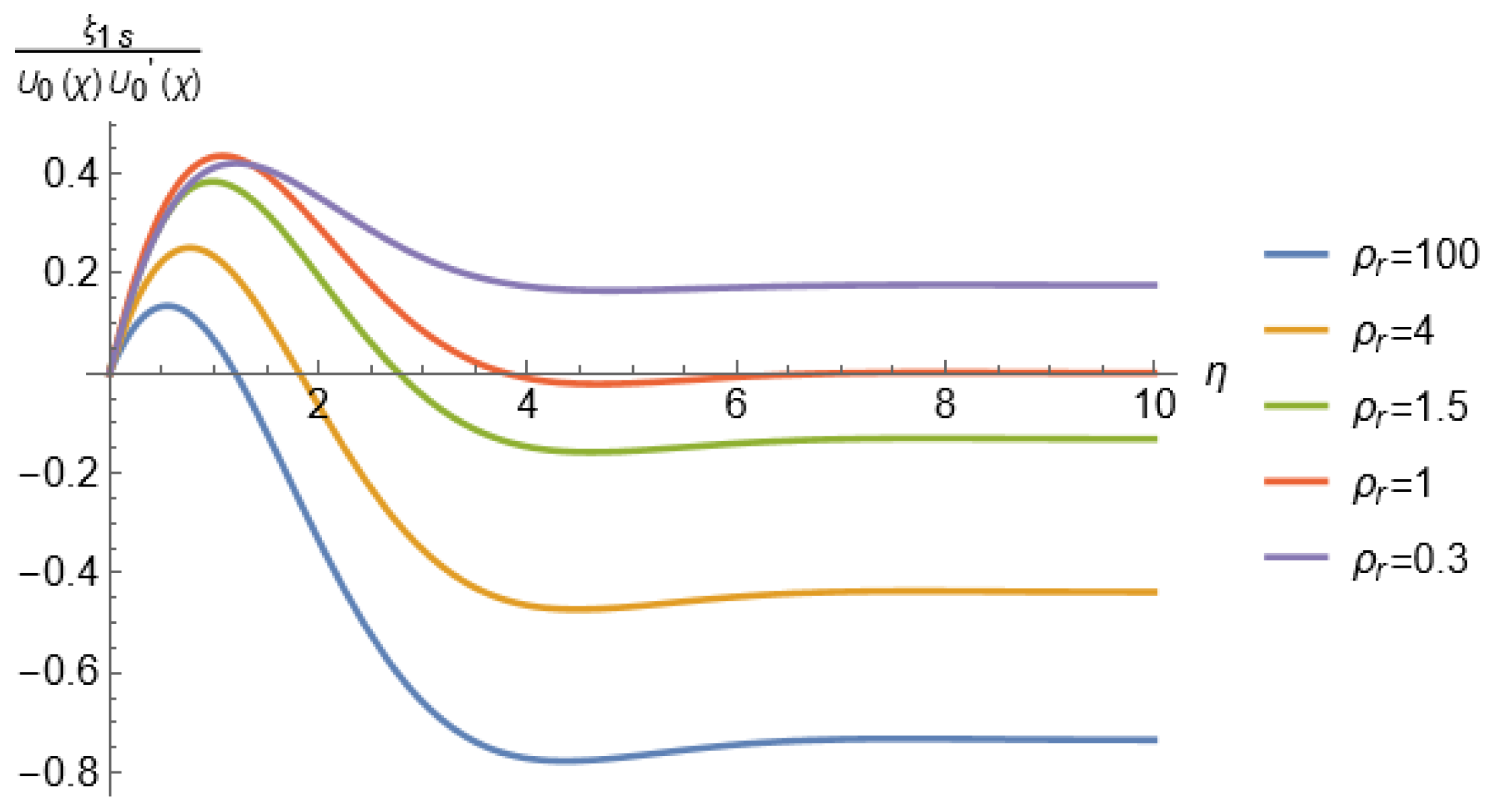

where

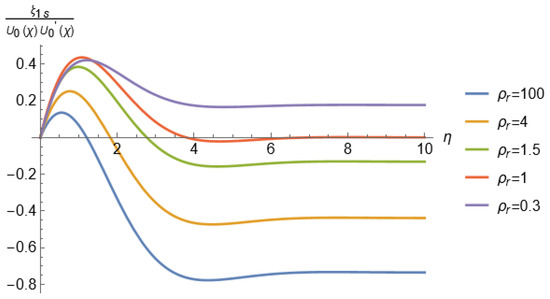

If we take the limit where the density of the wall tends to infinity (), Equation (54) recovers the classical Rayleigh’s law of streaming for a fixed wall, i.e., . This behavior is illustrated in Figure 4 which shows , normalized with , as a function of for different values of the parameter . It can be observed that at the edge of the inner boundary layer (), the limit value of the normalized function increases from negative values (−3/4 for ) to higher values as decreases. In fact, for the normalized value is approximately zero and becomes positive for , indicating a reversal in the direction of the steady axial velocity. The fact that the reversal occurs for small values of (<1), confirms that this effect is a direct consequence of the free-motion condition of the wall. It is important to note that the nonzero axial velocity at the edge of the boundary layer, given by Equation (50), reflects the penetration of the steady streaming flow—either normal or reversed, depending on the value of —into the outer potential flow.

Figure 4.

Normalized as a function of for different values of . and .

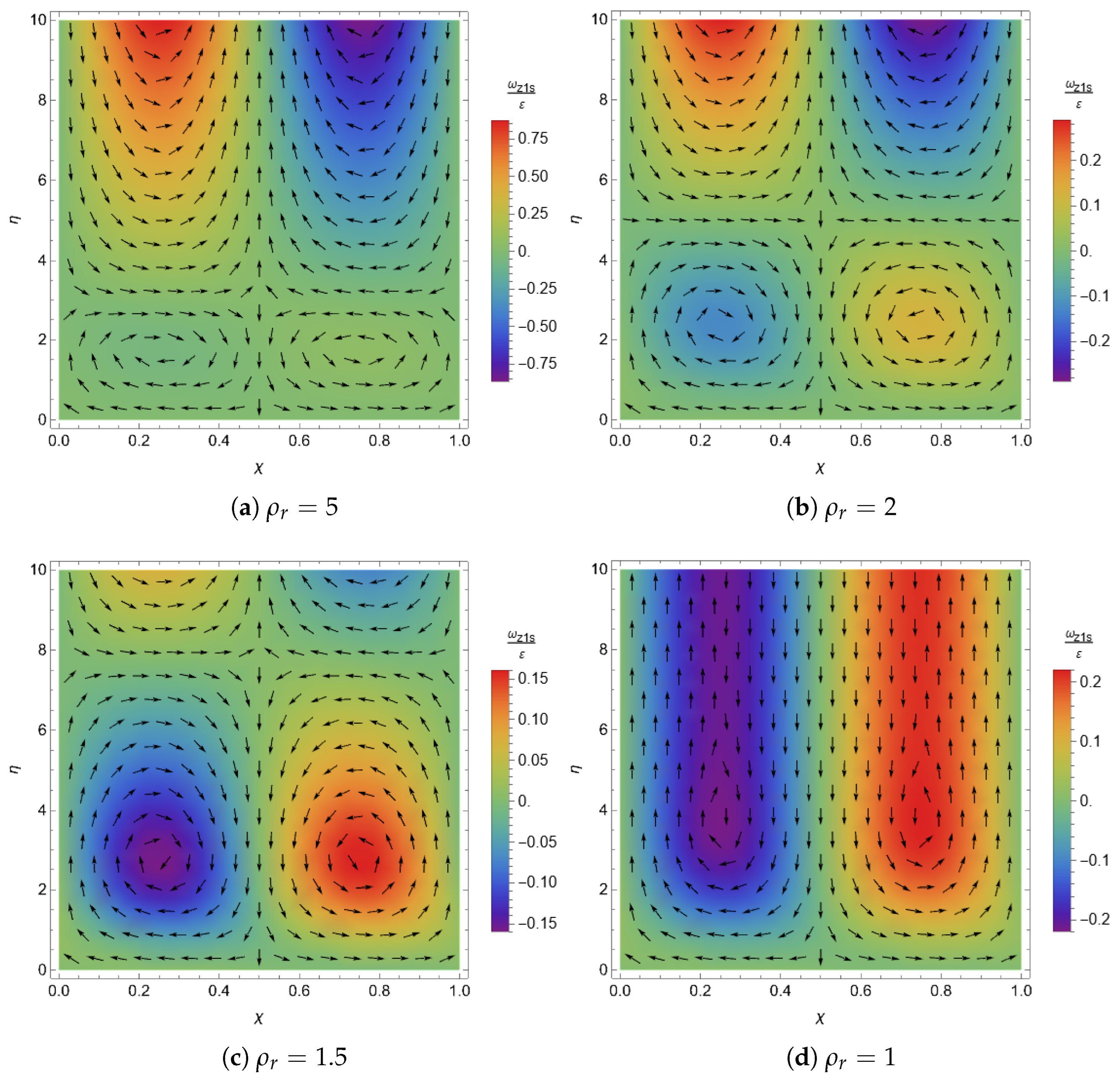

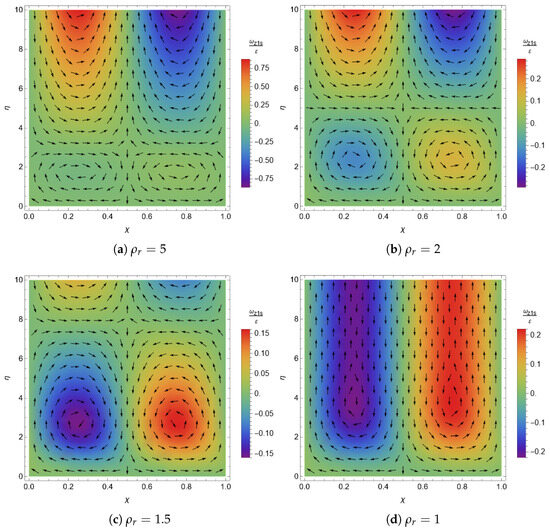

An illustrative way to show the appearance of reverse steady streaming is to plot the steady vorticity in the z-direction, , which in the present problem is given as

In Figure 5, the velocity field is superimposed on a background color map representing the vorticity field over one wall wavelength, obtained from Equation (55) for different values of , assuming a small wall amplitude (). Figure 5a illustrates the case , where two small counter rotating vortices are located near the wall, while an upper pair of vortices extends into the potential flow. As decreases to 2 and 1.5 (Figure 5b,c), the lower vortices increase in both size and intensity. Finally, when , Figure 5d shows only two elongated vortices with a reversed sense of rotation compared with the case, penetrating into the outer potential flow.

Figure 5.

Steady streaming velocity field superimposed on a background color vorticity map () over one wall wavelength, for different values and with .

4. Experiments

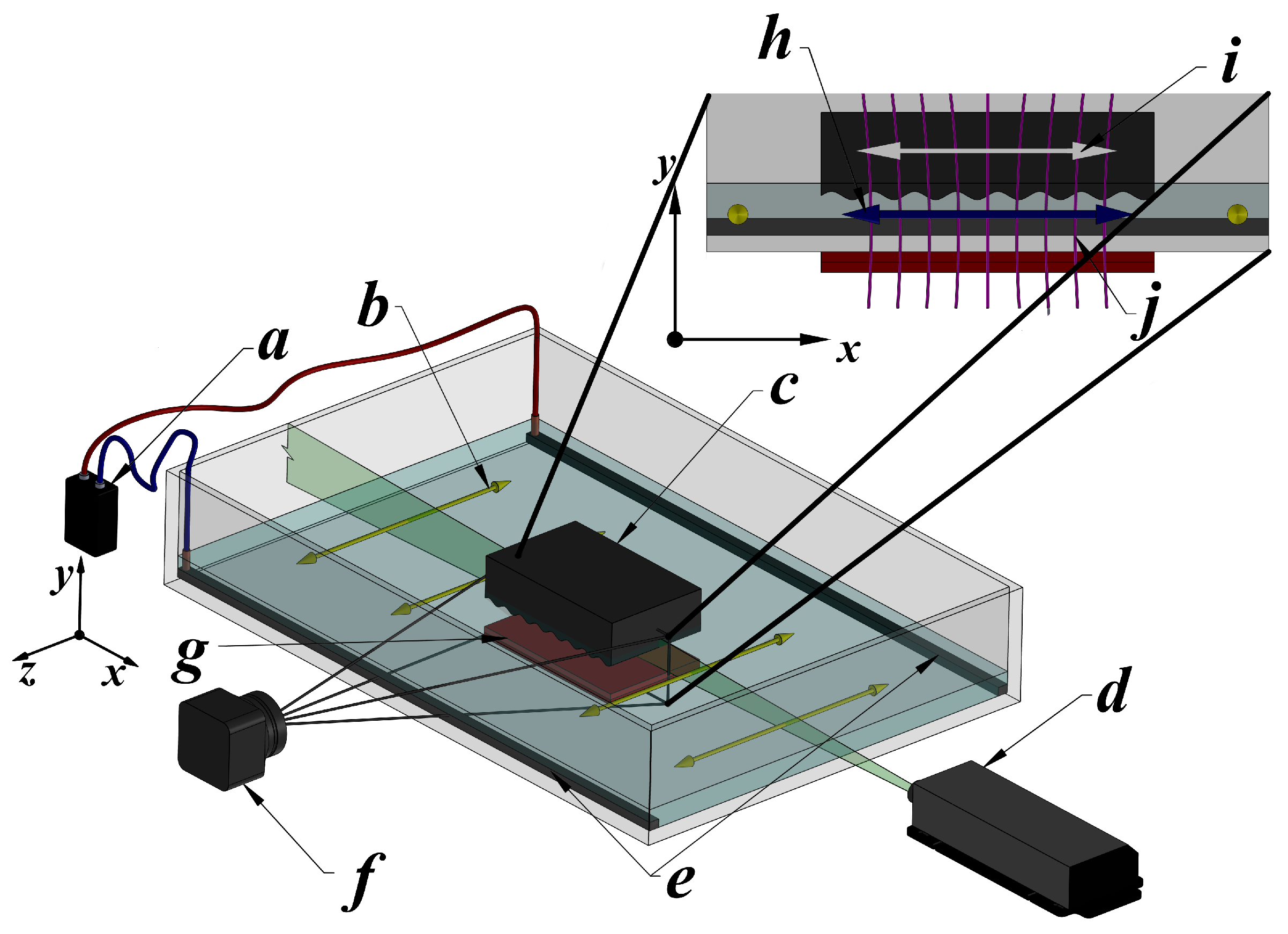

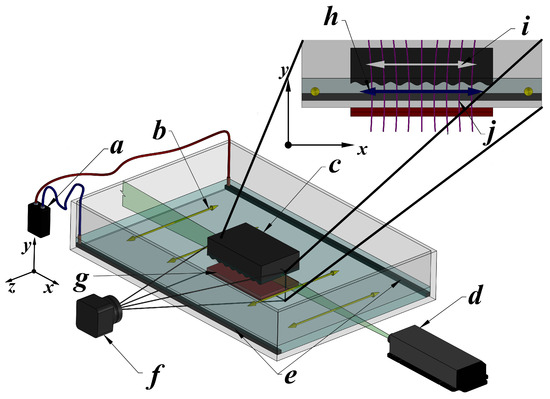

We now experimentally investigate the steady streaming induced by a freely moving wavy wall. From an experimental standpoint, the simplest way to realize a freely moving wall driven by an oscillating fluid is to float the wall on a liquid layer. The experimental setup consists of a glass container (30 cm × 15 cm × 16 cm) partially filled with an electrolyte solution to a height of cm. A plastic wavy plate floats freely on the surface, while an oscillating Lorentz force drives the fluid motion, as shown in Figure 6. The working fluid is a weak electrolytic solution of sodium bicarbonate at 8.6% by weight. At room temperature (20°), the mass density, kinematic viscosity, and electrical conductivity of the electrolyte are kg/m3, m2/s and S/m, respectively. A magnetic field is generated by a rectangular permanent magnet (8 cm × 5 cm × 0.5 cm) located beneath the container. The maximum magnetic field intensity, measured with a Tesla meter (F.W. Bell, model 048, Portland, OR, USA) at the magnet surface, is 0.5 T. An oscillatory electric current is applied between two parallel graphite electrodes using a function generator (Tektronix, model CFG250, Beaverton, OR, USA). The amplitude of the electric current is set to 120 mA, whereas the frequency range is 200–400 mHz. Under these conditions, electrolysis remains negligible. The origin of the coordinate system is located at the geometric center of the container’s bottom wall. The x-y plane lies within the vertical plane of the setup, with the y-axis oriented normal to the bottom wall, while the z-axis points in the perpendicular direction. The alternating electric current applied along the z-direction interacts with the magnetic field, whose main component lies in the y-direction, generating a Lorentz force that drives the fluid and the floating wavy wall into oscillatory motion along the x-direction. Although the flow past the wavy wall may produce a lift in the vertical direction, experimental observations confirm that the movement of the wall occurs only horizontally. Therefore, we conclude that, under the explored conditions, the lift force is negligible and the balance of the wavy wall in the vertical direction is purely hydrostatic.

Figure 6.

Isometric view of the experimental device (not to scale). The upper-right panel: view of the x-y plane from the PIV analysis. (a) Function generator. (b) Oscillatory electrical current. (c) Floating plate. (d) Laser source. (e) Graphite electrodes. (f) Camera. (g) Permanent magnet. (h) Oscillatory flow generated by the Lorentz force. (i) Oscillatory motion of the floating plate. (j) Magnetic field lines.

The wavy plate (7.8 cm × 4.8 cm × 2.0 cm) is made of 3D-printed ABS plastic and has a sinusoidal surface profile with amplitude 2 mm and wave length mm. The plate is polished and then coated with Fast Dry Acrylic Enamel to smooth the surface. The floating plastic plate has a uniform density ( kg/m3). In order to vary the density ratio (), the effective density of the floating plate was increased by placing weight uniformly on the plate. Thus, the effective density of the floating plate can be considered uniform. As a result, the corresponding density ratio spans the range .

Velocity fields are obtained with particle image velocimetry (PIV) in the x-y plane. Silver coated glass spheres (10 μm in diameter) are illuminated with a green laser sheet for the PIV measurements. To avoid, as far as possible, the recording of three-dimensional effects arising from the lateral boundaries in the z-direction of the wavy wall, the laser sheet is projected onto the mid-plane (). Consequently, the experiments are conducted under conditions that roughly approximate two-dimensional flow behavior in the -plane. The video recordings are captured using a camera (Nikon D80, Tokyo, Japan), with an AF Micro-Nikkor 60 mm f/2.8 lens. After the transient state, the recorded images are analyzed using PIVLab (version 3.12.001) [38]. The maximum amplitude of the experimental velocity was mm/s. Therefore, the corresponding Reynolds number, = 15, indicates a laminar flow. In turn, the parameter is smaller than unity (), ensuring the absence of boundary layer separation [10]. In addition, the Stokes layer thickness m is much smaller than the wavelength L, yielding a ratio of . Nevertheless, the dimensionless wall amplitude is , which lies outside the validity range of the theoretical model’s assumptions.

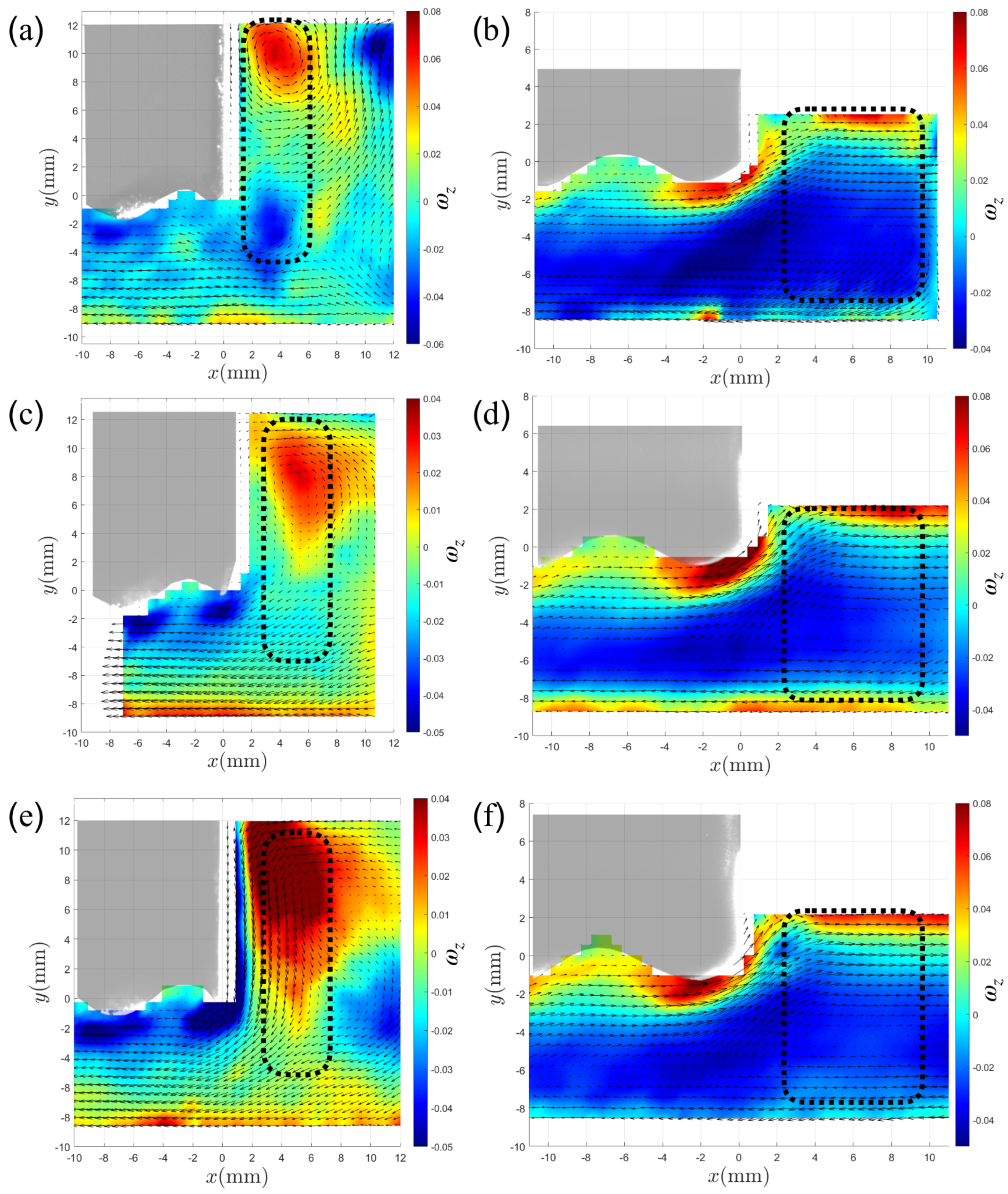

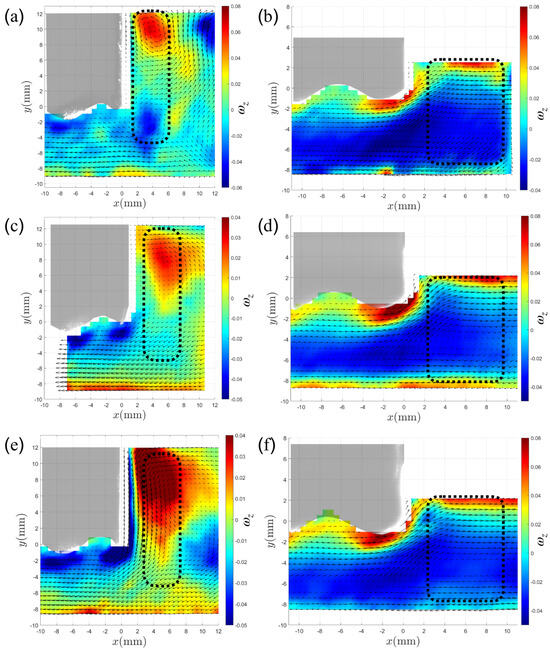

The PIV data are phase-averaged over one oscillation cycle to extract the steady streaming component. The resulting streaming flows are presented in Figure 7 where the velocity fields are shown on a colored background indicating the vorticity for three different oscillation frequencies (, 300 and 400 mHz), and two different density ratios ( and 0.94). Due to the finite size of the wavy wall, vortex formation is most evident near the side edges of the plate, where curvature variations are more pronounced. The main vortical regions are enclosed in dotted rectangles. Figure 7a,b correspond to and , respectively, both obtained at a common frequency of mHz. The case , that approaches the fixed wall limit, shows a large vortical structure with positive rotation in the upper flow region, while a smaller vortex with negative rotation is located below the large structure. In the light-wall case, , where the plate sinks to a shallower depth due to its lower density, a very large vortex with negative rotation is observed in the lower region of the flow which coincides with the theoretical prediction of the reverse steady streaming for . Similar results are observed in Figure 7c,d corresponding to the driven frequency of mHz, although only slight signs of the smaller vortex located below the large structure are found in the case . Finally, Figure 7e,f correspond to a frequency of mHz, where the positive vortex in the case is intensified while the lower one disappears. In turn, as for previous frequencies, the reverse streaming is clearly observed for .

Figure 7.

One cycle time-averaged velocity and vorticity fields from PIV. In (a,c,e), steady streaming flow is observed for at , 300 and 200 mHz, respectively. In (b,d,f), reverse steady streaming appears for at the same frequencies. The dotted rectangles indicate the flow region where the streaming and reverse streaming are observed. Flow reversal can also be observed in the region beneath the wavy wall.

Although technical issues (discussed in the next section) prevent the observation of streaming vortices within the undulations of the wall as in the theoretical solution (Figure 5), it can be clearly observed in Figure 7 that the flow beneath the wall reverses its direction when the density ratio varies.

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

We have investigated, both theoretically and experimentally, the fluid–structure interaction between a freely moving wavy wall and an imposed oscillatory laminar flow. This configuration represents a generalization of the modified Stokes’ second problem with a free-moving wall [31]. This study focuses on the steady streaming flow generated by nonlinear Reynolds stresses within the boundary layer, which arise due to the wall’s curvature. In particular, the objective was to demonstrate that the direction of rotation of the streaming vortices reverses when the density ratio between the wall and the fluid becomes sufficiently small.

The theoretical model considers an infinite wavy wall subjected to a harmonically oscillating potential flow that generates a boundary-layer motion. Using a perturbation approach in which the dimensionless displacement amplitude of the fluid is treated as a small parameter and assuming that the dimensionless wall amplitude is less than one, the boundary-layer equations are solved in conjunction with Newton’s second law for the wavy wall, which balances the wall’s inertia with the drag force exerted by the fluid. The solution, expressed in terms of the density ratio between the wall and the fluid, exhibits a first-order oscillatory response with a phase lag between the wall and the fluid motion. When , the inertia of the wall dominates and the fixed-wall limit is recovered. In contrast, for , the drag force exceeds the inertial effects, and the phase lag between the two motions becomes pronounced. The second-order solution contains both a harmonic component oscillating at twice the original frequency and a steady streaming contribution. As in the classical case [10], the streaming flow does not vanish at the edge of the boundary layer but instead penetrates into the outer flow which leads to a modified Rayleigh’s law of streaming. The results clearly show that as the density ratio decreases to , the direction of rotation of the steady vortices that extend into the outer flow is reversed, confirming that this reversal originates from the free motion of the wall.

The experimental setup consisted of a plastic wavy wall with adjustable density, floating on a layer of electrolyte driven by an oscillating Lorentz force. Velocity fields were obtained using PIV for three different frequencies and two different density ratios and subsequently averaged over a complete oscillation period to extract the steady streaming pattern. Experimental constraints prevent an exact realization of the idealized assumptions underlying the theoretically studied problem, primarily because the finite extent of the wavy wall introduces effects that are not captured in the theoretical model. In particular, the edges of the floating wall create abrupt geometrical transitions that promote the formation of large vortical structures in the regions adjacent to the wall. Consequently, comparison between the experimental observations and theoretical predictions are limited to the qualitative confirmation of reverse streaming, as the experimental setup does not fully satisfy the simplifying assumptions underlying the theoretical model. Furthermore, the limited resolution of the PIV system prevents visualization of the boundary-layer flow within the wall’s wavy regions, although the reversal of the flow beneath the wall when the density ratio varies is clearly observed. Therefore, the main objective—experimental verification of the reversal of steady streaming by varying the density ratio between the wall and the fluid—was successfully achieved. In future experimental studies, adjusting the oscillation frequency and thus the boundary-layer thickness, reducing the wall amplitude, and enhancing the PIV resolution may provide optimal conditions for resolving the flow within the boundary layer.

Because wall waviness serves as an effective model for the perturbations induced by surface roughness, this study may have potential applications in both microfluidic and oceanographic flows, where the reversal of streaming motion could play a significant role in particle transport.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; methodology, J.C.D.-L., S.G.-J., D.R.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; software, J.C.D.-L. and S.G.-J.; validation, J.C.D.-L., S.G.-J., D.R.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; formal analysis, J.C.D.-L., S.G.-J., D.R.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; investigation, J.C.D.-L., S.G.-J., D.R.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; resources, A.F. and S.C.; data curation, J.C.D.-L., D.R.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.C.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; writing—review and editing, J.C.D.-L., A.F. and S.C.; visualization, S.G.-J., D.R.D.-L. and A.F.; supervision, A.F. and S.C.; funding acquisition, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

A.F. thanks the program Investigadoras e Investigadores por México from Secihti and Fundación Marcos Moshinsky.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kumar, H.; Tawhai, M.; Hoffman, E.; Lin, C.L. Steady streaming: A key mixing mechanism in low-Reynolds-number acinar flows. Phys. Fluids 2011, 23, 041902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Martínez-Bazán, C.; Gutiérrez-Montes, C.; Criado-Hidalgo, E.; Pawlak, G.; Bradley, W.; Haughton, V.; Lasheras, J.C. On the bulk motion of the cerebrospinal fluid in the spinal canal. J. Fluid Mech. 2018, 841, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeaux, P. Sand ripples under sea waves Part 1. Ripple formation. J. Fluid Mech. 1990, 218, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, D.; Horrillo-Caraballo, J.; Karunarathna, H. The shape and residual flow interaction of tidal oscillations. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci. 2022, 276, 108023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzweg, U.H. Enhanced heat conduction in oscillating viscous flows within parallel-plate channels. J. Fluid Mech. 1985, 156, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.; Cuevas, S.; del Río, J.; López de Haro, M. Heat transfer enhancement in oscillatory flows of Newtonian and viscoelastic fluids. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2009, 52, 5472–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, G.G. On the Effect of the Internal Friction of Fluids on the Motion of Pendulum. Trans. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1851, 9, 8–106. [Google Scholar]

- Telionis, D.P. Unsteady Viscous Flows; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, N. Steady Streaming. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2001, 33, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, J.T. Double boundary layers in oscillatory viscous flows. J. Fluid Mech. 1966, 24, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayleigh, L. On the circulations of air observed in Kundt’s tubes and or some allied acoustical problems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 1884, 175, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting, H. Berechnung ebner periodischer Grenzschichtstromungen. Phys. Z. 1932, 33, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting, H. Boundary Layer Theory, 7th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 428–432. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelsen, A.F. An experimentalinvestigation of high Reynolds number steady streaming generated by oscillating cylinders. J. Fluid Mech. 1974, 64, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, N. The steady streaming induced by a vibrating cylinder. J. Fluid Mech. 1975, 68, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, N. On a sphere oscillating in a viscous fluid. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Maths. 1966, 19, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohara, N. The unsteady flow around an oscillating sphere in a viscous fluid. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1982, 51, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A. Steady streaming due to small amplitude torsional oscillations of a sphere in a viscous fluid. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Maths. 1993, 46, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritharan, K.; Strobl, C.; Schneider, M.; Wixforth, A.; Guttenberg, Z. Acoustic mixing at low Reynolds numbers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 054102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, D.; Mao, X.; Shi, J.; Juluri, B.K.; Huang, T.J. A millisecond micromixer via single-bubble-based acoustic streaming. Lab Chip 2009, 9, 2738–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Minten, J.; Rallabandi, B. Particle hydrodynamics in acoustic fields: Unifying acoustophoresis with streaming. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2024, 9, 044303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Nunn, A.R.; Brumley, D.R.; Sader, J.E.; Collis, J.F. The propulsion direction of nanoparticles trapped in an acoustic field. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 984, R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thameem, R.; Rallabandi, B.; Hilgenfeldt, S. Fast inertial particle manipulation in oscillating flows. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2017, 2, 052001(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, M.; Green, R.; Ohlin, M. Acoustofluidics 14: Applications of acoustic streaming in microfluidic devices. Lab Chip 2012, 12, 2438–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, B.; Chen, J.; Schwartz, D.T. Hydrodynamic tweezers: 1. Noncontact trapping of single cells using steady streaming microeddies. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 5429–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleischmann, F.; Luzzatto-Fegiz, P.; Meiburg, E.; Vowinckel, B. Pairwise interaction of spherical particles aligned in high-frequency oscillatory flow. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 984, A57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, H.; Giltinan, J.; Kozielski, K.; Sitti, M. Mobile microrobots for bioengineering applications. Lab Chip 2017, 17, 1705–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, T.; Chan, F.K.; Gazzola, M. Streaming-enhanced flow-mediated transport. J. Fluid Mech. 2019, 878, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinz, S. Direct and Large-Eddy Simulations of Wall-Bounded Magnetohydrodynamic Flows in Uniform and Non-Uniform Magnetic Fields. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut für Thermo- und Fluiddynamik, Technische Universität Ilmenau, Thuringia, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz, S.; Thomann, J.; Eichfelder, G.; Boeck, T.; Schumacher, J. Expensive multi-objective optimization of electromagnetic mixing in a liquid metal. Optim. Eng. 2021, 22, 1065–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, A.; Piedra, S.; Piñeirua, M.; Cuevas, S. Reverse streaming generated by a free-moving magnet. J. Fluid Mech. 2025, 1015, A28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.C.; Chen, C.L.; Chen, C. Electrokinetically-driven non-Newtonian fluid flow in rough microchannel with complex-wavy surface. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2012, 173–174, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.; Bautista, O.; Escandón, J.; Méndez, F. Electroosmotic flow of a Phan-Thien–Tanner fluid in a wavy-wall microchannel. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 498, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcos, J.; Bautista, O.; Méndez, F.; Peralta, M. Analysis of an electroosmotic flow in wavy wall microchannels using the lubrication approximation. Rev. Mex. Fís. 2020, 66, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, S.; Sierra-Espinosa, F.Z.; Avramenko, A.A. Magnetic damping of steady streaming vortices in oscillatory viscous flow over a wavy wall. Magnetohydrodynamics 2002, 38, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, S.; Domínguez-Lozoya, J.C.; Córdova-Castillo, L. Oscillatory boundary layer flow of a Maxwell fluid over a wavy wall. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2023, 321, 105125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, F.A. An Introduction to Fluid Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thielicke, W.; Stamhuis, E.J. PIVlab—Towards User-friendly, Affordable and Accurate Digital Particle Image Velocimetry in MATLAB. J. Open Res. Softw. 2014, 2, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.