Abstract

The traditional way to model the statistics of turbulent flow and dispersion is through averaged conservation equations, in which the turbulent transport terms are described by semi-empirical expressions. A new development has been reported by Brouwers in a number of consecutive papers published over the last 15 years. The new development is that presented descriptions can be obtained through the application of fundamental principles of statistical physics and making use of the asymptotic structure of turbulence at a high Reynolds number. They no longer rely on empirical constructions, minimise calibration factors, and are not limited to specific flow situations. This article updates the contents of these works and presents them in coherent manner. The first derivations are presented as expressions for turbulent diffusion. These are subsequently implemented in a closed set of equations expressing the conservation of mean momentum, mean fluctuating energy, and energy dissipation rate. Predictions from these equations are shown to compare favourably with the results of direct numerical simulations (DNS) of the Navier–Stokes equations of highly anisotropic and inhomogeneous channel flow. The presented model equations provide a solid basis to calculate the main statistical parameters of turbulent flow and dispersion in engineering praxis and environmental analysis.

1. Introduction

Fluid flow is often of a turbulent nature. Velocities and pressures vary irregularly with time. The occurrence of turbulence is closely related to the value of the Reynolds number, which is defined by

where U [m/s] is the fluid velocity, [m2/s] is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, and L [m] is characteristic length of the configuration in which or around which the flow takes place, e.g., the diameter of a pipe, the blade-span of a windmill, the length of an airfoil, or the height above the Earth’s surface. Turbulence is known to occur for values of which exceed . For air, is about [m2/s] and for water [10−6]. Many applications involving air are covered by [m] and [m/s]; for water, [m] and [m/s]. In all these cases, , implying turbulent fluid flow. Turbulence is more the rule than the exception. Practical cases of turbulent flow and dispersion are shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 1.

Turbulent flow behind windmills at sea visualised by condensing vapour.

Figure 2.

Spray behind Formula 1 car.

Figure 3.

Dispersion of smoke from chimney caused by atmospheric turbulence in the area.

Measurements of velocities and pressures in configurations of turbulent fluid flow often reveal stationary stochastic behaviour; time averages taken at fixed points are rather constant over longer periods of time. Data also reveal statistical distributions of velocity which are Gaussian or close to Gaussian: among others, that of Townsend [1], Laufer [2], Morrison et al. [3], Klebanoff [4] and Voth et al. [5] But general expressions for the statistical parameters which define these distributions were absent. General results were limited to specific cases, notably the expressions for the mean flow in the log layer by Von Karman [6] and the expressions for the high frequencies of turbulence by Kolmogorov [7].

A solid starting point for analysis is the Navier–Stokes equations, which describe the flow. These can be time-averaged, resulting in equations for mean values of velocity, pressure, and temperature. The problem arises with the average values of the products of fluctuating quantities within the non-linear convection terms in the equations. They describe the effect of fluctuations on mean flow quantities. It is known as the closure problem.

To overcome the closure problem, representations of average non-linear convective fluctuations have been proposed which are of a semi-hypothetical nature, drawing analogies with molecular chaos. Boussinesq [8] was the first to follow this line of thinking by introducing the gradient hypothesis, stating that the averaged non-linear fluxes are proportional to the derivative of the mean quantity preceded by a constant termed the turbulent viscosity or turbulent diffusion coefficient. Several versions and extensions based on the same idea have since been put forward by the pioneers of turbulence theory: Taylor [9], Prandtl [10], and Von Karman [6], among others. They also form the basis of many of today’s semi-empirical computer models used in engineering and environmental analyses; for example, see the works of Hanjalic and Launder [11] and Bernard and Wallace [12]. A prominent example of the semi-empirical approach is the widely used basic k- model [13,14]. Brouwers [15] recently showed that predictions by this model exhibited remarkable deviations from the results of direct numerical simulations (DNS) of the Navier–Stokes equations by Hoyas et al. [16,17] and Kuerten et al. [18].

Another way to describe turbulence is by the Lagrangian representation of fluid motion. It is common in fluid mechanics to describe fluid velocities at fixed positions, the so-called Eulerian approach which is also found in the Navier–Stokes equations. In the Lagrangian representation, velocities under consideration are those of a marked fluid particle which moves with the flow like a passive admixture. This approach was particularly motivated by questions of turbulent dispersion of aerosols and harmful substances in the atmosphere. Taylor [19] introduced the Lagrangian representation for the case of homogeneous isotropic turbulence. To address more general cases of anisotropic inhomogeneous turbulence, the Lagrangian approach became centred around the formulation of the Langevin equation for fluid particle velocity, presented in the work of Thomson [20], Wilson et al. [21], Borgas et al. [22], Pope [23], and Sawford [24]. Its integration resulted in the discovery of the path of the fluid particle and admixture connected to it. Many repeated simulations lead to a description of particle dispersion. A drawback was the formulation of a complete and unique expression for the damping term in the Langevin equation. It is known as the non-uniqueness problem and is outlined in Ref. [20]. Various expressions have been proposed: Refs. [20,21,22,23,24]. Partial progress could be made by the well-mixed condition of Thomson which matches the Langevin equation to the mean Eulerian velocities of the flow [20]. However, indeterminacy and formulations of a semi-hypothetical nature remained.

A new development was presented in a number of papers by Brouwers [25,26,27,28]. Rather than empiricism and hypothesis, general expressions of specified accuracy were derived. They were obtained by applying methods of statistical physics and random vibrations (Van Kampen [29], Stratonovich [30]), making use of the asymptotic structure of turbulence at a large Reynolds number (Monin and Yaglom, Ref. [7], Volume 2). This article updates these works and presents them in a chronological and coherent manner. In Section 2, formulae are derived for the turbulent diffusion of fluctuating momentum and conservative scalars. In Section 3, these formulae are implemented in averaged equations of the conservation of momentum, fluctuating kinetic energy, and energy dissipation rate. A closed set of equations is thus obtained whose predictions are found to compare well with the results of direct numerical simulations (DNS) of the Navier–Stokes equations of channel flow. It is concluded in Section 4 that the presented model equations provide a better way to predict the statistical parameters of turbulent flow and dispersion in engineering and environmental analysis.

2. Statistical Description of Anisotropic Inhomogeneous Turbulence

The first step in the subsequent analysis is the derivation of a unique description of the Langevin equation for the motion of a marked fluid particle. The diffusion limit of the equation enables the derivation of Eulerian descriptions of turbulent fluxes of momentum and scalars. The developed expressions are compared with the results of direct numerical simulations DNS of the Navier–Stokes equations of inhomogeneous anisotropic channel flow [17,18].

2.1. Langevin Equation Including Kolmogorov Similarity

Turbulent flow occurs for large values of Reynolds numbers, , a situation that is frequently encountered in practice. For , the time over which fluid particle accelerations decorrelate compares to the decorrelation times of particle velocity as to 1, e.g., Ref. [7]. This forms the basis for assuming that the velocity process can be represented by a Markov process, where accelerations are modelled as delta-correlated. The corresponding Langevin equation reads as

where the time-dependent position of the moving fluid particle is described by

and . In the above equations,

Fluid velocities at a fixed point in a fixed frame of reference using the Eulerian description are indicated by , while velocities of fluid particles that move with the flow using the Lagrangian description are indicated by . The coordinate is used to denote a fixed position in the non-moving fixed coordinate system, while is the position of a moving particle. The turbulent flow field is considered to be stationary in a fixed frame of reference. Statistical averages of Eulerian flow variables can be calculated by time averaging, which is indicated by angled brackets or superscript0. The white-noise amplitude can be specified by implementing the Lagrangian version of Kolmogorov’s similarity theory of 1941, also referred to as the K-41 theory: (Ref. [7] Section 21.3 and Ref. [31]).This yields

where is a universal Lagrangian-based Kolmogorov constant and is the mean energy dissipation rate averaged at a fixed position and evaluated at particle position when applied in Equation (4):

where is a fluctuating component of Eulerian velocity at a fixed position .

Although the presence of in the expression for energy dissipation may suggest otherwise, is a characteristic of the main inviscid flow governed by the large energy scales of turbulence. The magnitude of velocity gradients is governed by small viscous scales. It scales as and makes the magnitude of independent of . This independence is reflected in the equations for k and , presented in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4.

The observation that second-order correlations of fluid particle accelerations tend to those of a delta-correlated process, when , is, in itself, not sufficient to justify the Langevin model [25,26]. The description of the forcing term by Gaussian white noise leads to applying ordinary non-intermittent Kolmogorov (K-41) theory. The effects of intermittency, apparent in corrections in higher-order structural functions, are not accounted for in the Langevin model [25,26]. For that purpose, one can adopt a fractal model based on Kolmogorov’s refined similarity theory (Ref. [7] Section 25.2).

However, the statistical averages of particle displacement that determine turbulent dispersion change little under such an approach (Ref. [7] and Borgas [22]). The effect of intermittency is apparent in small viscous scales, which govern the acceleration process, rather than in large energetic scales, which govern the velocity process of turbulence. In many applications, a Langevin model resting on K-41 theory can be considered to be a sound approach for describing the mean dispersion on distances of large-scale turbulence.

Individual values of displacement and velocity obtained from Equations (2) and (3) do not represent the actual values of fluctuating displacements and velocities of fluid particles as they occur in turbulent flow. Instead, they are dummy variables that enable the specification of statistical averages of actual fluid flow. This is achieved by generating many realisations using as a random generator and averaging the results. In the case of the passive marking of fluid particles all starting at position at , the fluctuating velocities should, for every realisation, be selected randomly in accordance with the distribution of the Eulerian fluctuating velocity at position :

During a simulation, the coefficients in Equations (2) and (3) vary in magnitude with the particle position in accordance with their value at . A probabilistic description of particle displacement and its velocity is obtained after performing many simulations and averaging the result at every moment in time. This enables the average spatial distribution of particles with time to be evaluated. This type of Lagrangian averaging is denoted by an overbar. In the case of the simulated variable , it can be written as

where is the value of f at time t in the case of simulation n.

As an alternative to a time simulation using the Langevin equation, the same statistical distributions of fluid particle velocity and position can be obtained from the Fokker–Planck equation associated with Equations (2) and (3). It is given by

where is the joint probability density function of velocity and position at time t.

2.2. Specification of Damping Function by Expansion

Thus far, we have not specified the damping term in the Langevin equation. The specification of the damping term in a form that is generally applicable has long been an issue [20,25,26,27,28]. A way forward was provided by a method in which the Kolmogorov constant is used as the basis for an expansion. Solutions are described in terms of an expansion [26,27,28] in consecutive powers of . The expansion is not related to a dimensionless combination of parameters, which can attain a vanishingly small or large value. Such a combination does not exist. Instead, is used as a scaling parameter, facilitated by its autonomous position in statistical turbulence at a large Reynolds number [26,27,28].

The scaling parameter enters by the white-noise term and results in specific powers of in each of the terms on the basis of the required balances between them. The accuracy of the expansion depends on the truncation of subsequent terms. According to the measurements and data from numerical simulations, has a value of about 7 (see Section 2.8.3).

Realistic solutions in the limit of are obtained from the Langevin equation when all terms scale in the same manner with . For this to happen, the damping term must scale as , and the time of correlation, which is the statistically relevant time, as , thereby noting that the white noise term scales as . The displacement due to fluctuations during correlation scales is . This initial scaling allows for a number of approximations [26,27,28]. To the leading order in , the displacement of a particle is small, and values of fixed-point statistical quantities used in the parameters of the Langevin equation can be represented by their values at the marking point .

We can thus discuss a homogeneous statistical process in the initial stages after marking [26,27,28]. During that short time, the dissipation of energy by viscous action is small. The change in the Hamiltonian by viscous dissipation is small and proportional to . The statistical process is initially one that can be described by Einstein’s fluctuation theory, e.g., Reichl [32]. In the leading-order formulation in powers of , the damping term is linear in velocity, satisfies Onsager symmetry, and its magnitude is determined by the fluctuation–dissipation theorem [27,28]. As a result,

where is the inverse of the covariance tensor of the Eulerian velocity field

2.3. Higher-Order Formulation of the Langevin Equation

Until now, attention has been focused on the leading-order term in the expansion with respect to . The resulting descriptions involve a truncation error of . Such an error will become smaller the larger is. However, in turbulence, the value of is limited to about 7. This corresponds to and implies that the truncation error can become large. Deriving expressions for higher-order terms is thus desired. For that purpose, one can resort to the well-mixed principle of Thomson [20]. Given an initial distribution, particles will, over the course of time, mix with the fluid and attain the distribution of fluid velocity. This equilibrium distribution satisfies the Eulerian interpretation of Equation (8), which is given by Ref. [26].

Here, and is the distribution of the fluctuating component of the fixed-point Eulerian fluid velocity . There is no time derivative in Equation (11) when considering stationary turbulence. Statistical averages at a fixed point do not vary with time. Note further that is not a statistical variable but a fixed position. Statistical averages can be obtained from time averaging at fixed point . Derivatives of with respect to attain values whenever the statistical parameters of (covariances, etc.) vary in space (inhomogeneous turbulence).

The Eulerian distribution is equivalent to the non-equilibrium steady state distribution in statistical mechanics. Equation (11) represents the general form of the fluctuation–dissipation theorem that is appropriate for turbulence. Given , Equation (11) can be used to derive expressions for the damping function . Noting the leading-order formulation with respect to , cf. Equation (9), we have

where is to be determined. To comply with Hamiltonian behaviour, the Eulerian velocity distribution needs to be Gaussian to the leading order:

where is the zero-mean Gaussian while is the correction on the Gaussian behaviour. The formulation according to Equation (13) is in line with the many observations of almost Gaussian behaviour of velocity statistics. Values of the zero-, first-, and second-order moments are fully captured by the Gaussian part of the description:

Values of cumulants higher than second order are determined by . Substituting the description for and Equation (12) into Equation (11), one obtains, for , the following equation:

where there are dropped terms of relative magnitude in the contributions due to non-Gaussianity, i.e., the second term on the right-hand side of Equation (15). Equation (15) is exact, i.e., it does not involve any approximation or truncation with regard to in the case of Gaussian Eulerian velocities . The solution of Equation (15) is presented in Ref. [26]:

where ,

where is the solution of the homogeneous problem

A variety of solutions exists for , linear and non-linear in ; however, each of them contains a degree of indeterminacy apparent in unspecified constants. When confining the damping function to linear representations in , the solution of Equation (18) is

where is the alternating unit tensor. Solution (19) constitutes an antisymmetric extension to the symmetric damping tensor derived in the previous section as described by the first term of solution (12). In this solution , are three dimensionless constants whose values are unknown. It is a reflection of the nonuniqueness problem; except for isotropic turbulence, it is impossible to fully specify the damping function on the basis of a specified fixed-point Eulerian velocity distribution.

Combining Equations (12), (16) and (17) yields, for the damping function in Langevin Equation (2), the expression

While the first term in this solution corresponds to the result of the Hamiltonian base case, the other terms represent the correction due to inhomogeneity in an otherwise locally homogeneous statistical field. The corrections can be related to the change in energy, which was disregarded in the leading-order formulation where underlying particle mechanics can be considered Hamiltonian [26,27]. The second term describes the change in energy due to changes in covariances in the direction of the mean flow. Accelerating or decaying the mean flow results in non-zero values of the second term. The third term describes the effects of the spatial gradient of the fluid velocity covariance. This can be associated with shearing due to external forcing.

Dropping the fourth and fifth term on the RHS of Equation (20) leads to a result known from Thomson [20]. It was one of several proposals made for the damping functions, which all satisfy the well-mixed criterion and which correspond to an entirely Gaussian Eulerian velocity distribution. The variety of possibilities is a reflection of indeterminacy because of nonuniqueness. The analysis in the next section provides an answer to the issue. It reveals descriptions for statistical displacement obtained by applying the diffusion limit to Equation (20), which are unique up to an error of . Contributions of the next-to-leading-order of the non-linear terms in the damping function (the third and fourth terms on the RHS of Equation (20) are absent because of the Gaussian behaviour in the leading-order formulation. The last term in the damping function does not contribute in next to leading order when well mixing is applied according to Equation (18).

2.4. The Diffusion Limit

The diffusion limit concerns the description of random particle displacements on a time scale that is much larger than the correlation time of the fluctuating velocity. As indicated by a balance between the acceleration term and damping term in the Langevin equation, the correlation time can be expressed as

where is the magnitude of velocity fluctuations and is the characteristic time of large scales or of the eddy turn-over time. The description of the time scale is known as coarse graining, e.g., Ref. [7] Volume I, Section 10.3. The magnitude of the fluctuating fluid particle displacement during correlation can be represented by

where represents the size of the eddies, which is also the distance over which the statistical parameters vary in magnitude.

The Langevin model is centred around the fluctuating particle velocity relative to the mean Eulerian velocity: cf. Equations (2) and (3). In line with this representation, the displacement of a fluid particle by the sum of a component due to the mean flow and a component representing the zero-mean random displacement are described (see also Ref. [33] and Section XVI.5 of [29]):

where is the particle track according to the Eulerian mean velocity:

For general inhomogeneous turbulent flow, the Eulerian-based coefficients in the Langevin model vary in magnitude with the space coordinates. This makes the coefficients time-dependent in the Langrangian-based description of the Langevin model. Representing displacement using Equation (23), the time dependency occurs in two ways [27]: (i) through spatial variations when following the particle according to the mean velocity and (ii) through dependency on random displacement

In the next analysis, we shall disregard the dependency on . Furthermore, we disregard the non-linear second term in the damping function as well as on the r.h.s. of Equation (16). Requiring the Gaussian behaviour in the leading-order formulation and well mixing for next-to-leading order, all these terms yield contributions of relative magnitude in the diffusion model (see the Appendix at the end of this section).

The Langevin model, which specifies diffusion to the leading order and next-to-leading order, now follows from Equations (2), (3), (12) and (16).

From Equations (3), (23) and (24), we obtain

Fluctuating Equations (26) and (27) can be transformed into a Fokker–Planck equation for the joint probability of and . The solution is a multi-dimensional Gaussian distribution with time-dependent parameters ([29] Section VIII.6). The zero-mean probability density distribution for the fluid particle position in the fixed Eulerian coordinate system , which moves with the mean Eulerian velocity , is specified by the diffusion equation

subject to a suitably chosen initial distribution at , i.e., the delta pulse in the case of passive marking of particles at and . Note that the time derivative in the above Eulerian description applies to the coordinate system, which moves with the mean velocity according to Equations (23) and (24), .

- To evaluate the diffusion coefficient note that

There is no contribution of the last term of the Langevin Equation (26) because is only correlated with . Substituting Equation (30) into the r.h.s. of Equation (29) results in the following first-order differential equation for the diffusion coefficient:

subject to the initial condition at . The equation describes the transient of the diffusion coefficient towards its value valid in the diffusion limit when . This limit value can be time-dependent on the time scale and can be obtained by iteration using as the small parameter [27]. The leading order follows from a balance between the second term on the l.h.s. and the first term on the r.h.s. Substituting this solution into the neglected other terms and noting that, according to our definitions, when , we obtain, in terms of the Eulerian coordinates of the non-moving frame [27]

The leading-order term in the diffusion tensor is symmetric; the terms that are next to the leading order are not. However, the non-symmetric part of the tensor makes contributions of in the convection of fluid particles and admixture. To demonstrate this, we note that when is anti-symmetric we can use the property that the diffusion term in the conservation equation reduces to a convection term according to . Its contribution is to be compared with convection by mean flow and will be of relative magnitude , which is beyond the accuracy of the perturbation scheme. The non-symmetric part makes no contribution to the next-to-leading-order terms in the diffusion coefficient.

In the above derivation, we considered the limit by which velocities de-correlate from their initial value at . At the same time, one can take , which is the time scale of the large eddies and the time scale of inhomogeneous behaviour. Under this condition, the values of parameters can be represented by their values at the initial marking: . As one can repeat the derivation for any other point of marking, one can replace with , i.e., , and in Equation (32).

The diffusion equation in a non-moving Eulerian frame now follows from Equations (28) and (32) as

where is the probability density of a marked fluid particle at position and time t. The probability distribution applies equally to parameters whose values are linearly connected to the value of the particle position, i.e., concentrations of passive or almost passive admixtures, such as aerosols or the temperature in incompressible or almost incompressible fluids (see also Section 2.6). To determine the distributions from Equation (33), the mean values , co-variances , and mean dissipation rates need to be known. These can be obtained using the techniques of Computational Fluid Dynamics, such as the closed set of equations presented in Section 3 of this monograph.

Appendix

The above results for diffusion were obtained by adopting a number of approximations. This includes disregarding the changes in the coefficients of the Langevin equation due to random displacement : cf. Equation (26). Its effect can be assessed by the Taylor expansion around . For example, , where . Here, t scales as , in accordance with the correlation time of fluid particle velocity. Displacements due to random motion are thus small and during times of correlation. It implies that the second term of the Taylor expansion yields a contribution in the leading-order term of the damping function which is next-to-leading order. But this contribution no longer counts when applying averaging to the Langevin equation according to Equation (30) leading to the specification of the diffusion coefficient. The contribution vanishes because it becomes a triple correlation of zero-mean velocities and displacements. It is zero to first order as velocities and displacements are Gaussian to first order. In summary, we can replace and with and without affecting the accuracy of the two-term expansion.

Another approximation concerned the neglect of the non-linear third and fourth term of the damping function in Equation (20). The terms are next-to-leading order in the expansion scheme. Implementing these non-linear terms in the procedure leading to Equation (30) leads to mean values and triple correlations involving and , which are zero because of the zero-mean Gaussian distributions of and .

The last term on the r.h.s of Equation (20) represents the contribution due to non-uniqueness. As this term is next-to-leading order, we can evaluate its contribution in the diffusion coefficient taking the leading order statistical formulations for and . To leading order, the Langevin equation can be expressed as (cf. Equations (2), (4) and (9)):

where , . Multiply l.h.s and r.h.s. by , where and . Averaging both sides yields

Integrating with respect to time from to , where , so that the correlations have vanished, we have

Note that we used the property that and constitute stationary processes whose statistical values do not vary with time. Equation (36) can be converted to

where . Furthermore, in the diffusion limit

where we took for the probability density of the Gaussian distribution because only the leading-order formulation of the above term counts in the perturbation scheme. Incorporating the above expressions into the r.h.s. of Equation (30) or (31) will lead to an extra term on the r.h.s. of diffusion coefficient Equation (32), which is given by

For general forms of , the term will be next-to-leading order. However, a special situation arises when satisfies the well-mixed condition as specified by Equation (18), as it should. It can then be shown that the above term becomes an anti-symmetric tensor. Therefore, multiply the first of Equation (18) by and integrate over the entire -domain. Partial integration and implementation of the expression of according to Equation (38) yields

The inclusion of Equation (39) in the diffusion equation results in a convective term only. Its relative magnitude is (see the discussion subsequent to Equation (32)). The contribution of the non-unique term in the Langevin equation to diffusion is thus limited to one of relative magnitude compared to the leading terms.

The outcome of the expansion is that Gaussianity can only be required to exist in the leading-order formulation. To model non-Gaussianity in the next-to-leading-order formulation, a general term in the damping function has to be added which captures the contribution of the cumulants of the third and higher orders of Eulerian velocities, i.e., the term in Equations (13) and (17). Applying an analysis similar to that shown above then shows again that such an extra term only yields contributions in the diffusion model which are (Section VIII of Ref. [25]).

2.5. Statistical Descriptions of Momentum Flux

Momentum flux plays a central role in the conservation equations of fluid mechanics. An issue is the specification of the Reynolds stresses, i.e., the mean value of the fluctuating components of the momentum flux tensor. The conservation equations are typically formulated with respect to a fixed coordinate system, viz., the Eulerian formulation. The aim of the present analysis is to derive expressions for the mean value of the fluctuating components that fit in the Eulerian frame. First, the Lagrangian-based momentum flux tensor is considered, where are the velocities of moving fluid particles that all pass at through the surface at (alternatively, one can choose the velocity and the surface but with ultimately the same Eulerian result due to the symmetry of the diffusion tensor).

Statistical averages are determined at a close distance from using Lagrangian-based expressions for , which were derived in the previous sections. Taking the diffusion limit of the Lagrangian-based solutions and letting the distance from approach zero on the coarse scale of the diffusion approximation, a connection can be made with the Eulerian-based value of the tensor: . This enables the completion of the description of the averaged representation of the conservation equations of momentum for fluid mechanics.

The displacement of a marked fluid particle that is at position at time follows from Equation (3) as

where is value of the Eulerian mean velocity at particle position and

To describe the position of the particle, at times close to , expand the r.h.s. of Equation (42):

where is the Eulerian mean velocity at . Neglected terms on the r.h.s. of Equation (43) are larger than quadratic in t and . It can be shown that these terms fail to contribute to . The underlying reason for this is that once averaging is applied, these terms constitute triple correlations whose values are zero when evaluated using the Gaussian distributions of the leading-order formulation. In accordance with the above expansion, the particle velocity is described by

The objective is to describe the average momentum of particles that cross the surface at with velocity . The particles are situated in an area that is small compared to the size of the large eddies so that Eulerian statistical averages can be treated as homogeneous in space. Furthermore, the area considered is large compared to the area where the particle velocities are correlated. For these conditions to be satisfied, , which is the condition for the diffusion limit to apply. This involves a limit process whereby time approaches zero but on the time scale of coarse graining of the diffusion limit: , where is the correlation time of the particle velocities.

The momentum for small negative times is given by

The average value of the momentum of all particles passing the surface is ; that is, adding the momentum of all particles which are at different positions at time —t and dividing by the number will yield

with the property that and at . Fluid particles will cross the plane at different positions. However, the particles under consideration are in an area whose size is limited. The spatial variations in the mean Eulerian velocities are small and can be disregarded within the order of approximation of the developed perturbation scheme. In Equation (46), they are taken to be equal to the value at the point of the crossing of Equation (45).

When applying Langevin Equation (2) to negative values of t, the damping term has to change sign in order to yield the required decay with . Hence, , , and

The correlation can be determined in accordance with Equations (31) and (32), where the energy dissipation rate and the co-variances can be taken to be equal to their values at under the limit process of the diffusion limit. The result equals the expression for the diffusion coefficient of Equation (32).

When shear and mean flow gradients are absent, an isotropic state exists, a feature that is seen in grid turbulence. In this case,

where is Kroneker delta and is the kinetic energy of the isotropic state. It is the analogue of the kinetic energy of translating gas molecules [29,32].

The result of Equation (50) applies in an area where the diffusion limit holds. The area is of volume , where and where is the length of velocity correlations and L is the size of the large eddies or flow configuration. The presented descriptions are valid in the limit of , . The smallness of is limited: . Yet, comparison with a range of results of measurements and direct numerical simulations shows fairly good agreement (Section 2.8). The reason is that terms of order are incorporated into the expansion, and the correlations decay exponentially with time , where is the eddy turnover time (cf. Equation (21)).

Reducing the volume of the area to zero, it becomes identical to a point in the Eulerian description of the flow field. We can thus take

where is the fluctuating Eulerian velocity at position .

Similarly to the analysis in the previous section, one can repeat the above procedures for any other point in Equations (52)–(54) to all positions by replacing with . The resulting statistical descriptions describe in an Eulerian frame the change in the isotropic turbulent stress tensor by gradients of the mean flow. The relation can directly be implemented in the averaged Navier–Stokes equations. Specification of the stresses will be completed by equations for and , which are presented in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4.

2.6. Statistical Descriptions of Scalar Flux

Examples of scalar flux are the dispersion of substances immersed in fluids and of temperature distributions in incompressible and almost incompressible fluids. Turbulence is known to have a significant effect on these phenomena. Similarly to the analysis of the previous section, consider an area that is small compared to the area of inhomogeneity but large compared to the area where particle velocities are correlated. The Lagrangian scalar flux is described by , where are the velocities of marked fluid particles that all pass at through a surface at , and is the value of the scalar quantity at the position of each moving particle. When considering the velocities of particles at a short distance, the time from the surface of passing Equation (44) can be employed. For the value of the scalar quantity at the position of the particle, we have

where is the mean Eulerian-based value of the scalar at position . The first and second term on the right-hand side represent the dispersion of the scalar quantity due to fluid particle displacement, whereby the scalar does not vary in magnitude while moving with the fluid particle. The third term is autonomous random changes in the value of the scalar quantity while moving with the fluid particle. For the first term, take the Eulerian-based mean value at . Similarly to the analysis of the previous section, particles pass through different positions at the surface . However, all these positions are at a limited distance from each other in accordance with the coarse graining of the diffusion limit.

On this scale, spatial variations in value of the first term of the expansion can be disregarded. They can be taken to be equal to the Eulerian mean value at the single point . Furthermore, the first term is allowed to vary deterministically with time , where is the time in the Eulerian fixed frame of reference: . Lagrangian averaging can take place by adding the simulation results of the Langevin equations at a fixed value of and subsequently repeating for every other value of . The variation with is considered to be slow compared to the rapid variation of the random fluctuations of .

Multiplying the right-hand sides of Equations (44) and (55), replacing t by , applying Lagrangian averaging, and letting after applying the diffusion limit, one obtains the following (similar to the procedure of the previous section):

The third and fourth terms on the right-hand side are contributions due to autonomous fluctuation of the scalar when moving with the fluid particles. To determine the values of these terms, the fluctuation equations of need to be known. No attempts will be made to derive such equations. We assume that is a conservative scalar whose value does not change while moving with the fluid particle: . Noting that

and implementing Equation (48) then yields

where equals the Eulerian-based value at . As the relation holds for every position x, we have

where is a conservative scalar that satisfies the Eulerian-based conservation equation

Applying ensemble averaging to the above, substituting Equation (59), and replacing by t, yields

where we employed the averaged version of continuity: . The above result equals the equation for fluid particle distribution given by Equation (33). This is consistent with the feature that the distribution of the particle must be equal to the distribution of a conserved quantity whose value does not change with the value of , following the path of a fluid particle.

2.7. Decaying Grid Turbulence

Decaying grid turbulence has been studied many times throughout the previous century, and many results are available. Turbulence is generated by a uniform mean flow that passes through a grid of squarely spaced bars. The grid is perpendicular to the incoming mean flow. At some distance behind the grid, a homogeneous field of isotropic turbulence develops and decays in the downstream direction with the mean flow. For grid turbulence, exact results for the Langevin and diffusion equations are known. In the present section, I recapitulate these results and compare them with the present results based on the two-term expansion.

For convenience in presentation, turbulence is described in a frame that moves with the uniform mean velocity. I thus describe the equivalent situation where the grid moves with constant speed from right to left through a fluid that is initially at rest. When the grid has passed, a uniform field of isotropic zero-mean Gaussian fluctuations exists, which decays in time. The strength is the same in all three coordinate directions. Therefore, analysis is restricted to fluctuations in one direction only. Corresponding variables are indicated by a subscript of 1. Regarding the independence of fluctuations in three directions, a problem of nonuniqueness, as discussed in Section 2.4, does not exist. The appropriate Langevin equation in one-dimensional form can be written as

where is the Eulerian mean square of the fluctuations

Expressions for and can be derived from the Von Karmanz–Howarth equation for the conservation of the mean kinetic energy of fluctuations. For large Reynolds numbers, these expressions are Ref. [34]:

where is the reference time, i.e., a moment in time where the grid has passed the observer at a fixed position. The value of depends on the dimensioning of the grid and can be established by measurements at time . Implementing Equation (64) into Equation (62), we have

From this result, one can derive (analogous to the derivation in Section 2.4) the diffusion equation

where the diffusion coefficient is given by

Note that the diffusion coefficient does not decrease in the stream-wise direction. A decay in the strength of fluctuations is compensated for by an increase in the correlation time.

The results of Equations (65)–(67) were obtained without using the expansion. The Langevin equation according to a two-term expansion is given by Equations (2) and (20). Introducing the features of grid turbulence results in an equation that is the same as Equation (65). The diffusion coefficient according to the two-term expansion is given by Equation (32). This reduces, in the case of grid turbulence, to Expanding the exact result given by Equation (67) in powers of yields .

The first two terms in the diffusion coefficient of the exact result thus agree with the two-term expansion. The third term amounts to a relative contribution of 0.9% when . In conclusion, the two-term expansion complies with the corresponding expansion of the exact result, and the error of truncating the third term is small. The latter conclusion is, however, of limited value as the grid turbulence is isotropic and only slightly inhomogeneous in the stream-wise direction. In practice, turbulence is mostly anisotropic and appreciably inhomogeneous. The next section analyses such a case.

2.8. Comparison with DNS of Turbulent Channel Flow

Turbulence is a well-known feature of flows in pipes and channels and in boundary layers along walls, including the boundary layers along the earth’s surface. A representative case for such flows is a developed turbulent flow in a channel of two parallel flat plates. The statistical values are constant in the direction of the mean flow between the plates and in the direction that is parallel to the plates and perpendicular to the mean flow but changes significantly in magnitude in the direction normal to the plates. The fluctuations are strongly anisotropic.

2.8.1. Exact Results

Some exact results can be derived from the averaged Navier–Stokes (N-S) Equations (Ref. [7] volume I, p. 268). The averaged equations are given by

where is pressure relative to the pressure of the fluid at rest, and is the density. In the case of a developed turbulent channel flow, the mean values involving fluctuating velocities and pressure gradients vary only with the wall normal coordinate . The averaged N-S equations then reduce to

where is the coordinate of the mean flow direction, are the co-variances of fluctuating velocities, and is the mean pressure. The contribution of the viscous stress, represented by the last term in Equation (68), was disregarded in the above equations. The effect is limited to thin viscous layers near the wall. Their effect on the flow outside of these thin layers can be accounted for by the boundary condition imposed on the shear stress at the wall. From Equations (69) and (70), one obtains the following solutions:

where is the shear velocity and is the distance between the parallel plates. The shear velocity can be related to the pressure drop in the channel by solving the flow in the boundary layer at the wall. The relationship is also known from measurements, e.g., Ref. [7]. The value of is representative for the magnitude of the fluctuations.

2.8.2. Results from the Expansion

The exact results of Section 2.8.1 can be extended by supplementing the expressions for the turbulent momentum diffusion of Equation (54). For the channel flow, these become

where is the mean flow in the channel and where the diffusion coefficients are obtained from Equation (32) as

Equations (71)–(78) constitute 8 relations for 10 variables: , and . A closed system of equations requires two extra equations. These are provided by the conservation equations for kinetic energy k and dissipation rate known from CFD models [11,12]. At this point, our aim is not to study a complete and closed system of equations but to analyse all those components that describe turbulent transport individually. For this purpose, one can calculate the values of the left-hand sides and right-hand sides of the developed relations using the data of direct numerical simulations and compare them with each other. This provides a direct test of the outcome of the expansion. A complete and closed set of equations is formulated and analysed in Section 3 of this monograph.

2.8.3. Comparison with the DNS Results

Super computers have created the possibility to simulate turbulent fluid flows through direct numerical simulations (DNS) of the equations that govern fluid flow, i.e., the Navier–Stokes equations. Initially, attention was focused on grid turbulence at modest values of Reynolds numbers. The calculation power has increased with time. This allows the handling of flows at larger Reynolds numbers and with more complex configurations of channel flow. Hoyas et al. [17] recently published results for channel flow at a friction Reynolds number of . This corresponds to a bulk flow Reynolds number of about . DNS is the most reliable technique for studying turbulence, and its outcome can be considered as exact. The results of Hoyas et al. provide an excellent opportunity to verify the present results.

Statistical Values of Fluctuations

Making , , k, , P, and dimensionless according to

and henceforth dropping in Section 2 the asterisks of the dimensionless variables, one can derive, from Equations (71)–(78), the relations

where

and P is the production of energy, defined as

From Equations (80)–(82), it can be verified that, at , . This is consistent with the solution for a zero mean flow gradient. At , the solutions for the log law apply, according to which, . From Equations (80)–(82), one then finds

These reveal anisotropy whose magnitude depends on the magnitude of .

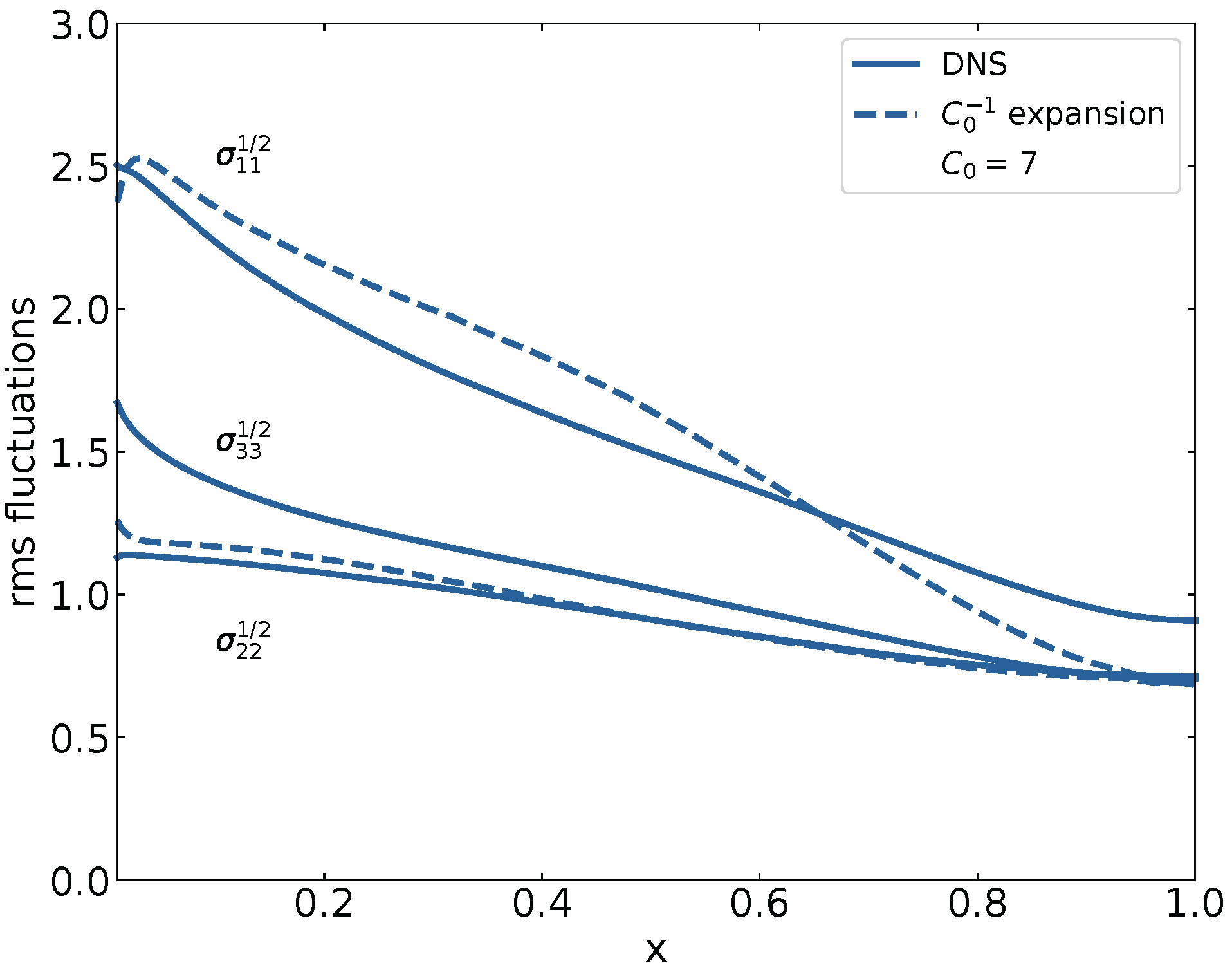

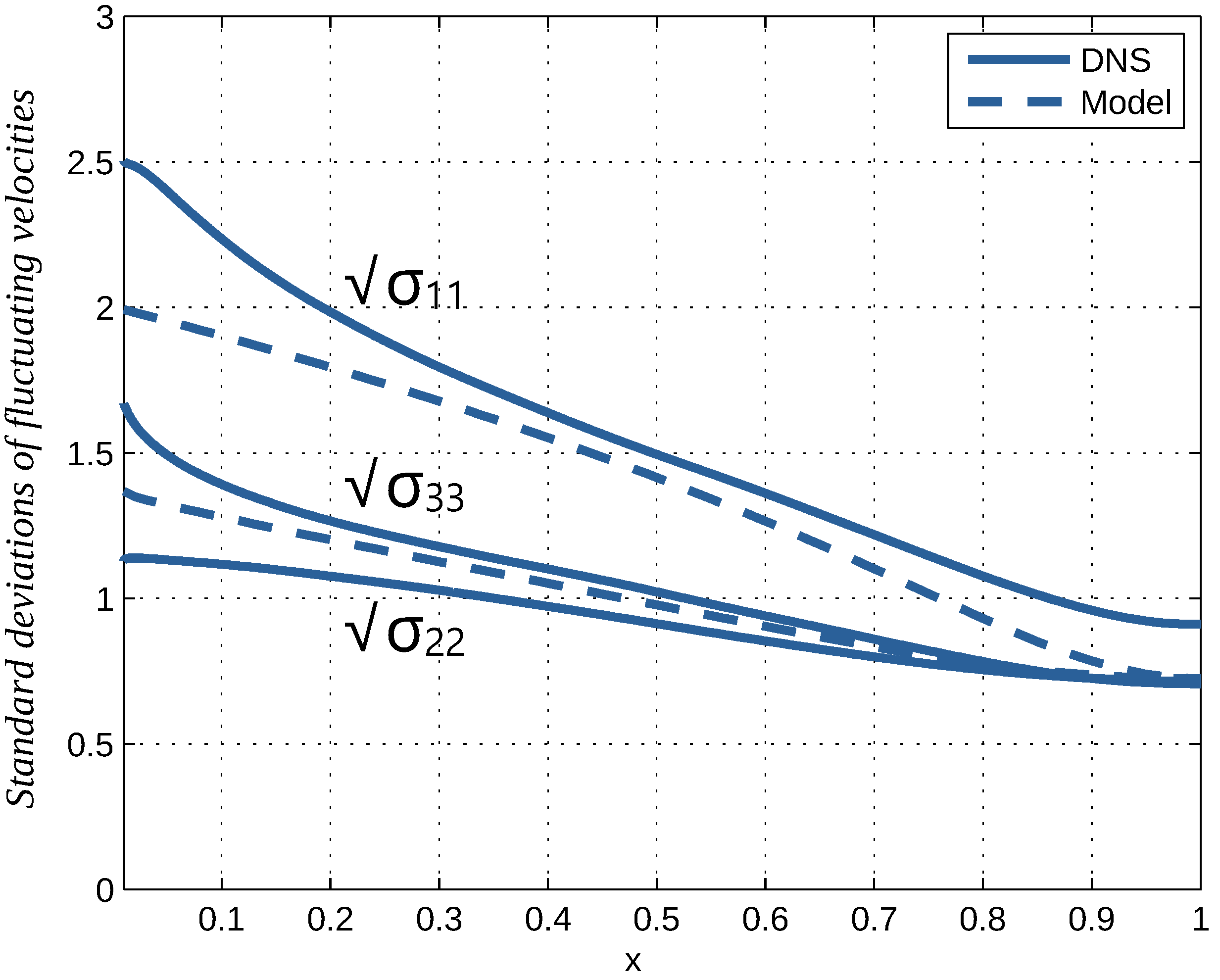

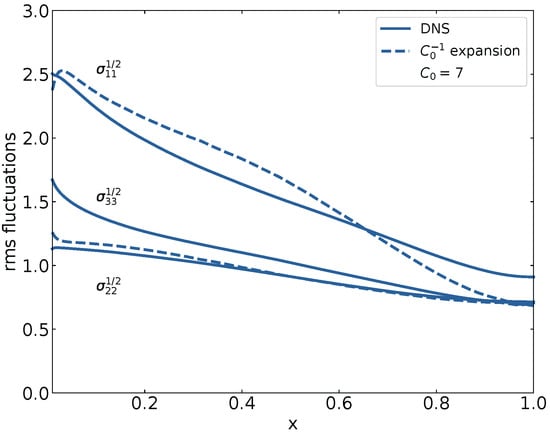

Figure 4 shows the values of the root mean square of fluctuations according to Equations (80)–(82) versus x for taken from DNS and . The values are compared with the corresponding DNS values of these parameters. Close to the wall at , the effect of the viscous layer is seen. Its thickness is about , which amounts to 1% of the height of the channel. The results of the expansion only apply outside this area. Here, it is seen that strong anisotropy in the longitudinal direction is predicted.

Figure 4.

The root mean square values of the velocity fluctuations versus the dimensionless distance from the wall. The root mean square values obtained from DNS are represented by full lines. The root mean square values of the expansion are represented by broken lines. They result from Equations (80) and (81), in which the right-hand sides were evaluated using the DNS values. Differences between full and broken lines can be ascribed to truncation of the expansion.

A difference between fluctuations in the normal and the span-wise direction as forecast by DNS is not revealed. Differences between the longitudinal fluctuations and normal fluctuations near the axis are not revealed either. Near , differences between rms values in the normal and span-wise direction are at maximum. The differences between longitudinal and transverse fluctuations are at a maximum at . Otherwise, the differences between the DNS and expansion are rather limited—keeping in mind the limited smallness of the perturbation parameter .

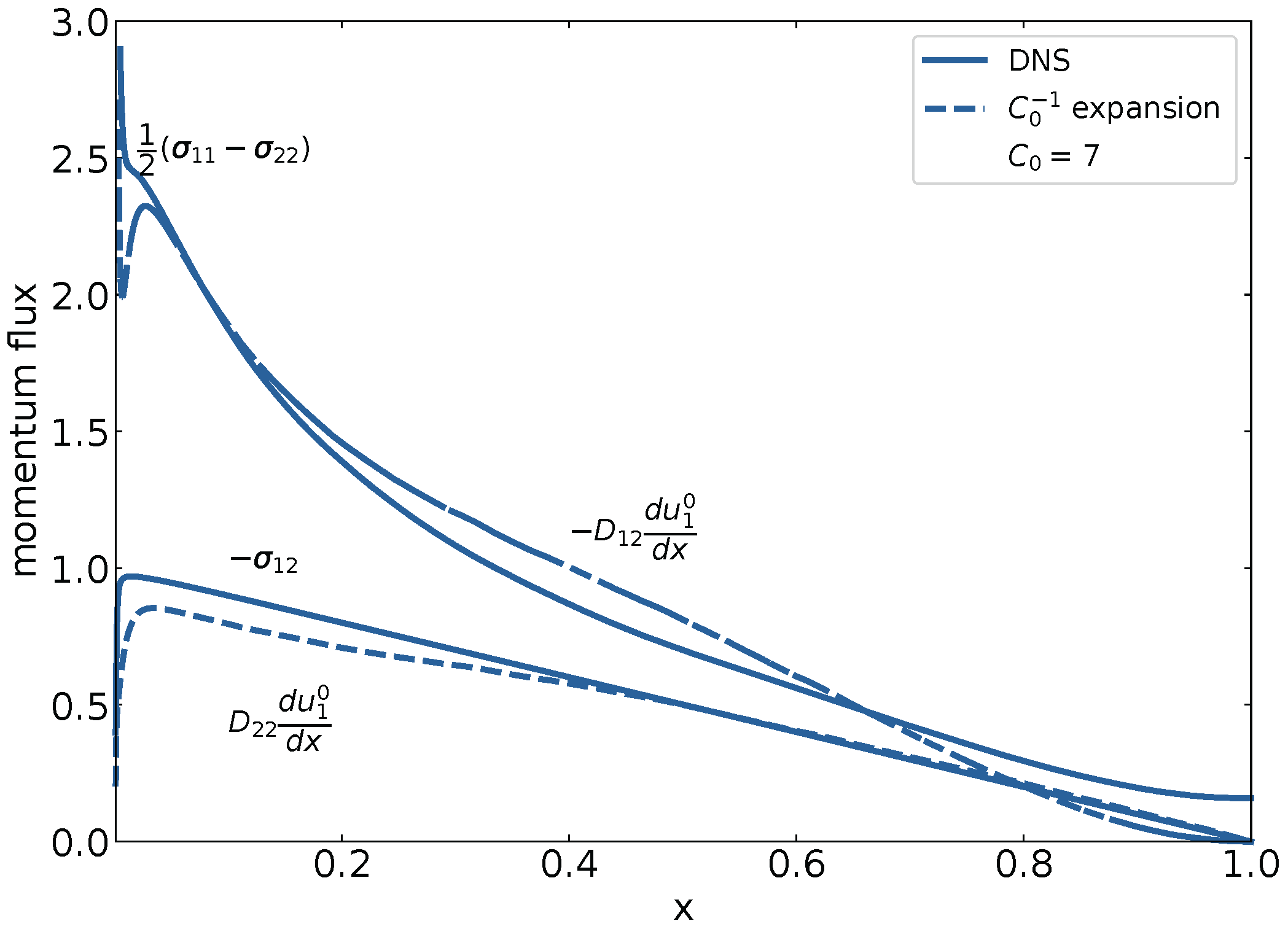

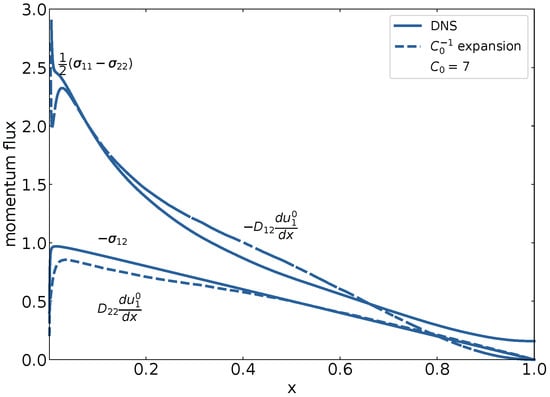

Statistical Values of Turbulent Fluxes

An issue in turbulence theory is the statistical description of the non-linear fluctuating convective terms in the equations of conservation of momentum and energy. The issue is known as the closure problem. The present analysis provided an answer through the expressions for turbulent flux and turbulent diffusion coefficients. Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the results obtained for these terms and compare them with the DNS results.

Figure 5.

The mean momentum fluxes versus the dimensionless distance from wall. The values of and are obtained using DNS and are represented by full lines. The values of and result from the expansion and are represented by broken lines. They follow from Equations (73), (75) and (76), using the DNS values for , and .

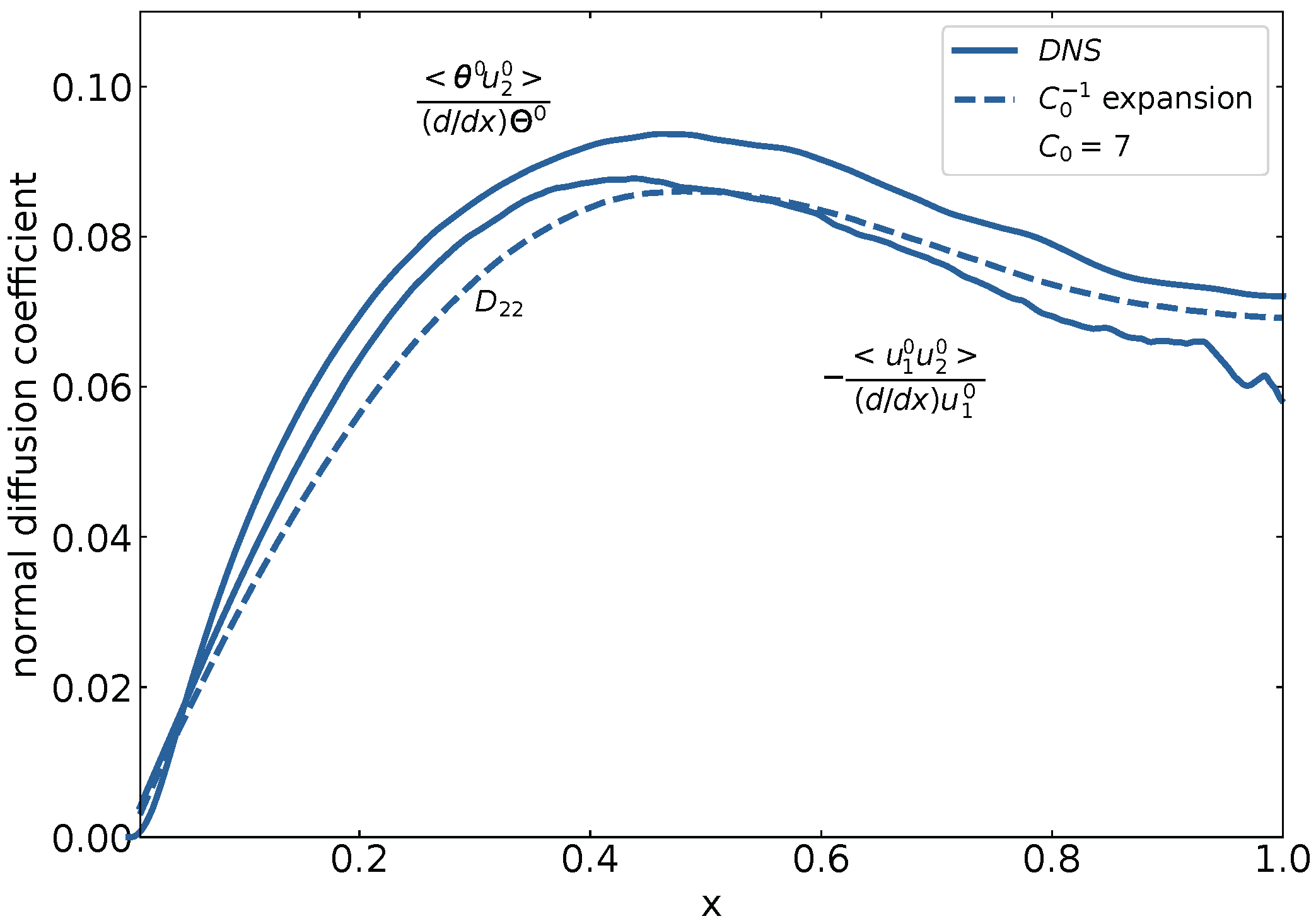

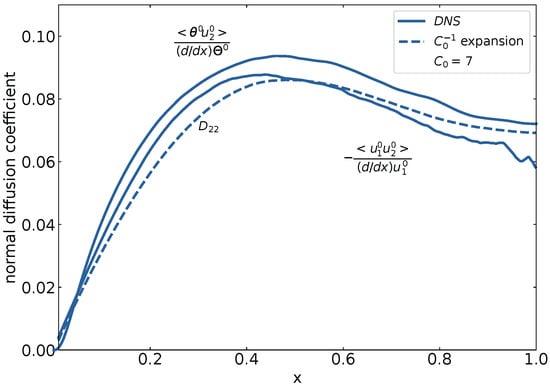

Figure 6.

Coefficients of diffusion in the wall-normal direction for momentum transport and heat transport versus dimensionless distance from wall. The values of and are obtained using DNS and are presented by full lines. The values of result from the expansion. They follow from Equation (78), in which the right-hand side was evaluated using the DNS values. They are represented by a broken line.

Diffusion Coefficients

Coefficients of diffusion in the wall normal direction are compared in Figure 6. The diffusion of both momentum using the data of Hoyas et al. [17] and of the conserved scalar temperature using the DNS data of Kuerten et al. [18] is analysed.

Kolmogorov Constant

In general, it is found that a value of 7 for gives a good fit to the DNS. This value is somewhat higher than the value of 6.2 mentioned previously, considering the DNS of turbulent channel flow at of [27]. A value of of 7 at a high Reynolds number has been claimed by Sawford, referring to the DNS of grid turbulence [24].

Conclusions

The results for the main Eulerian statistical parameters in the case of channel flow are shown in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. They reveal fairly good agreement between the predictions of the model when compared with those of the DNS. This conclusion applies to turbulent channel flow, which is a case of turbulence that is significantly anisotropic and inhomogeneous. As the model has a general basis, this entails the prospect of yielding reliable results for other cases of anisotropic inhomogeneous turbulent flow.

3. Closed Set of Equations to Calculate Statistical Parameters of Turbulent Flow and Dispersion

The expressions for turbulent diffusion derived in the previous section are used to formulate averaged versions of conservation equations of momentum, of fluctuating energy, and of dissipation rate. The solutions of these equations are shown to compare favourably with results of the DNS of channel flow.

3.1. Averaged Conservation Equations

The flow is that of a fluid with constant or almost constant density , e.g., a liquid or a gas at subsonic speed. Turbulent fluctuations measured at a fixed point in space are treated as a statistical process which is stationary or almost stationary in time compared to the time of velocity fluctuations. Statistical averages follow from time averaging over sufficiently long time intervals. The time-averaged representation of the Navier–Stokes equations is given by

- Conservation of mass:

3.2. Diffusion Representations of Turbulent Fluxes

The appearance of turbulent fluxes in the convection terms of the averaged conservation equations results in an unclosed set of equations for mean flow variables. As shown in Section 2, to resolve this issue, descriptions of the turbulent flux terms have been derived which are based on general principles of statistical turbulence at a large Reynolds number [35,36,37]. The derivation starts from the formulation of a Langevin or fluctuation equation and the associated Fokker Planck or diffusion equation for the velocity and position of a marked fluid particle [25,26,27]. The approach is known from applications in molecular dynamics and related stochastic problems [29,30,38], yielding the descriptions of the transport coefficients of viscosity, thermal conductivity, and diffusion of dilute gases [38,39]. Challenges in the case of turbulence are the inhomogeneous and anisotropic nature of turbulence, dissipation of energy, and general specification of the coefficients of the equations by the Eulerian statistical values of the flow.

The following principles and properties were invoked:

- –

- The formulation of a Langevin equation for fluid particle velocity is in accordance with the property that auto correlations of particle accelerations are vanishingly short compared to those of velocities in the limit of a large Reynolds number [7].

- –

- Kolmogorov similarity theory holds for the small viscous scales of turbulence [7]; it’s inertial subrange representation specifies the white noise term in the Langevin equation.

- –

- Solutions of the Langevin and diffusion equation are presented by a perturbation expansion in powers of the inverse of the Kolmogorov constant [25,26,27]. Predictions are matched with data of measurements and DNS revealsvalues of around 6–7 [23,25,26,27]. In the present analysis, .

- –

- The time scale of velocity fluctuation and its decorrelation scales compared to the time scale of energy dissipation: This enables to treat the first term of the solution as a Hamiltonian process and to apply the fluctuation–dissipation theorem and Onsager symmetry [29,32].

- –

- The well-mixing principle of Lagrangian and Eulerian velocities [20] enables the specification of the second term in the expansion of the diffusion result.

- –

- Particle displacement during velocity correlation scales as compared to the scale of inhomogeneity, enabling the Lagrangian formulation to be converted into an Eulerian one [27,36].

Results for turbulent fluxes of momentum and conservative scalars are as follows (cf. Equations (54) and (59)).

momentum flux

temperature flux (and flux of any conservative scalar)

In Equation (89), is Kronecker delta and is the kinetic energy of the isotropic state. It is the analogue of the kinetic energy of translating gas molecules [40]. The value of follows from the equation for kinetic energy presented in the next section.

The diffusion coefficient in Equations (89) and (90) is specified by (cf. Equation (32))

where

is the energy dissipation rate whose governing equation is presented in Section 3.3 and is the Kolmogorov constant.

Implementing the above expressions in Equation (89) results in a set of algebraic relations of the covariance tensor in terms of and mean velocity gradients. Solving these non-linear coupled equations for given and mean velocity gradients can pose some problems due to multi-valued dependencies between variables in specific areas of the flow field [15]. An alternative formulation which circumvents such problems is obtained by the following procedure. The diffusion coefficients on the right hand side of Equation (4) represent a certain state which is altered by the gradients of the mean flow, leading to a new state of co-variance values, described by the left hand side of Equation (89). This principle can be applied to any state. It can be applied to a basic isotropic state . The thus-determined new state can serve as the basis for the calculation of the next state. This process can be continued up to and including terms of . The result inhibits the same truncation error as the original formulation, cf. Equation (91). For the diffusion coefficient , we obtain

while the covariance tensor follows from Equation (89) as

where

is rate of strain. For the kinetic energy , we can write using Equation (94)

which relates k to the isotropic value of the kinetic energy . The second and third term on the RHS of Equation (94) and the second term on the RHS of Equation (96) describe the anisotropy of the turbulent fluctuations. The last term of the RHS of Equation (93) originates from the terms in the formulation Equation (91) The term complies with the decaying part of kinetic energy and the dissipation of homogeneous isotropic turbulence behind a grid, as shown in Section 2.7.

The presented descriptions are valid up to a truncation error of . They are the result of applying general principles and do not involve empiricism and calibration factors.

3.3. Equation for Kinetic Energy

A closed set of equations is obtained upon formulating equations for k connected to through Equation (96) and . For both variables, equations can be derived from the Navier–Stokes equations. For k, we can write [11,12]:

where P is the mean production of energy by turbulent fluctuations, defined by

and where and are the fluctuating parts of kinetic energy and pressure, respectively, that is, the kinetic energy and dissipation rates minus their time-averaged values. There are two turbulent flux terms in Equation (97), i.e., the third and fourth term on the LHS of Equation (97), which need to be modelled. Equation (90) is valid for a conservative scalar while kinetic energy and pressure are non-conservative variables. An approximate approach is to treat the sum of the two flux terms as a conservative scalar proceeded by a calibration constant , which corrects for non-conservative behaviour

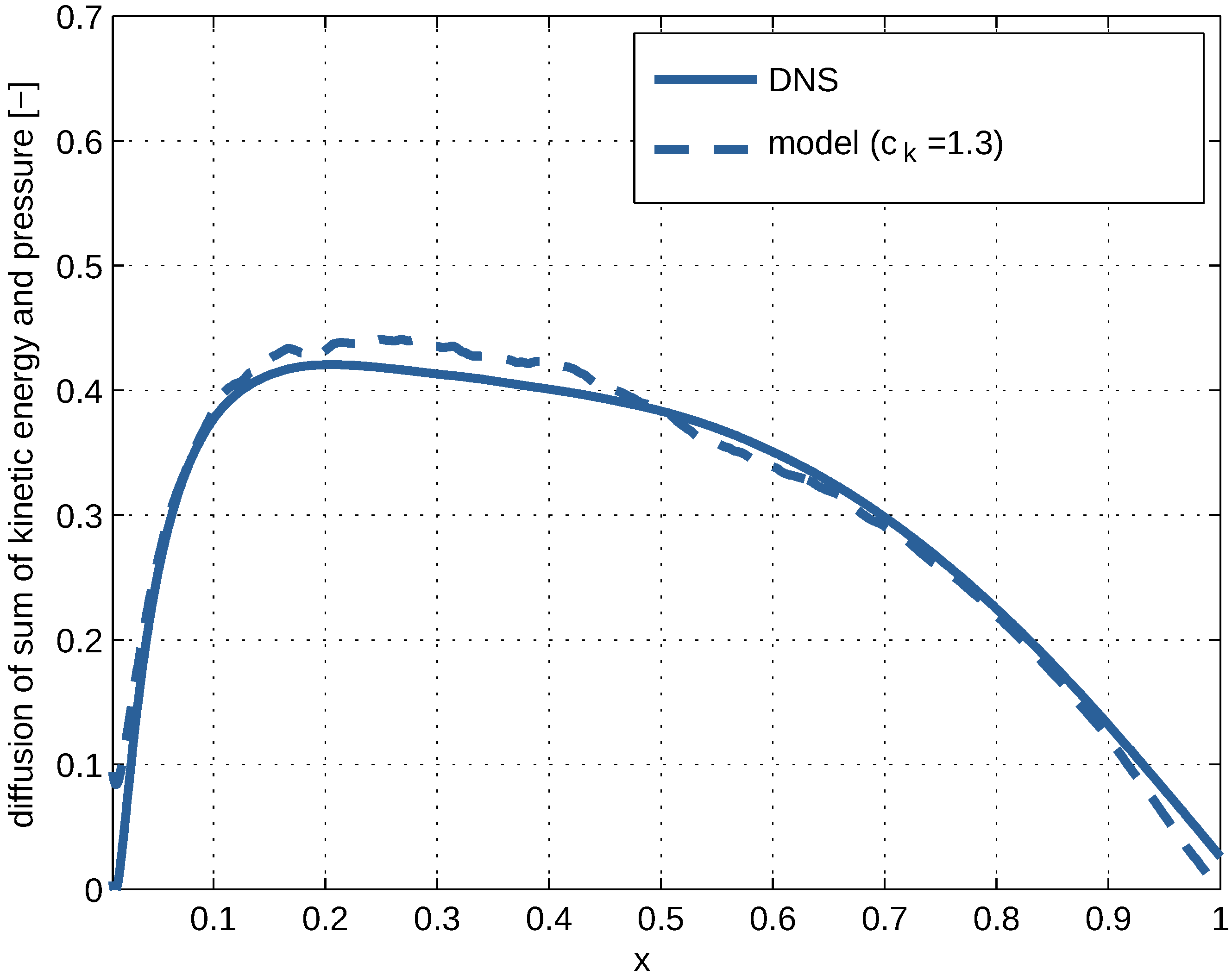

Comparison with the DNS of channel flow reveals that (see Section 3.6 and Figure 13). This value of the calibration factor leads to good agreement over the entire distance from the wall to the centre of the channel. It indicates that gives the correct dependency on distance, while the degree of anisotropy changes significantly over the same distance.

Substituting for , in Equation (98) expressions (92), (89) and (93), and making use of the equation of continuity (86), yields

where is determined by shear stresses

which are specified by Equations (89) and (93). The following equation for kinetic energy is obtained

where k can be replaced by using Equation (96), resulting in an equation specifying . The equation describes the change in due to energy production and dissipation (the last term on RHS), diffusion of energy (the first term on the RHS), and energy convection (the term on the LHS). In case of the random motion of gas molecules, is a constant, depending on temperature. In case of turbulence, changes in value according to Equation (102).

3.4. Equation for Energy Dissipation

To arrive at a closed set of equations for statistical parameters, an equation for energy dissipation needs to be derived. In the case of homogeneous isotropic decaying turbulence behind a grid, such an equation can be obtained through a self-similar solution [12]. But, for general inhomogeneous anisotropic turbulence, general solutions are not known. A semi- empirical approach is needed. Starting from the Navier–Stokes equations, a conservation equation for energy dissipation can be formulated. In averaged form, this equation reads as

where is the fluctuating part of the energy dissipation and is its mean value. The function is of a complex form [11,12], whose value is governed by averages of small scale fluctuations of turbulent velocities. Following Kolmogorov theory, can be expressed in terms of parameters relating to the large scales of turbulence. In line with this thinking, a semi-empirical expression for can be formulated which combines energy production and energy dissipation as [11,12]

where and are calibration constants, determined below. Turbulent transport by fluctuations is described by

where is a calibration constant which corrects for the non-conservative behaviour of . Upon substituting Equations (104) and (105) into Equation (103), we have as the transport equation for

The constants and can be determined by considering the cases of decaying grid turbulence and the log layer of turbulent channel flow. In case of grid turbulence, there are no mean flow gradients and production is nil. The RHS of Equation (106) then complies with decaying grid turbulence and a suitable value for is 1.9 [11,12]. In case of the log layer of channel flow, turbulent diffusion of kinetic energy vanishes when approaching the wall of the channel. As follows from Equation (100) and (102), production and dissipation the become equal. According to the solutions of the log layer, the gradient of the mean flow behaves as , where is the Von Karman constant, , is the shear velocity (square root of the shear stress at the wall divided by fluid density), and is the distance from the wall. Noting that near and at the wall, the shear stress is , from Equation (98), it follows that P behaves as and behaves the same. Substituting these dependencies in the diffusion term of in Equation (106) and evaluating the diffusion coefficient, one finds that the diffusion term is also proportional to (see also the formulae presented in Section 3.6). To avoid the explosion of these terms when approaching the wall, we have to equate the coefficients of these terms such their total becomes zero, as . This leads to the following relation:

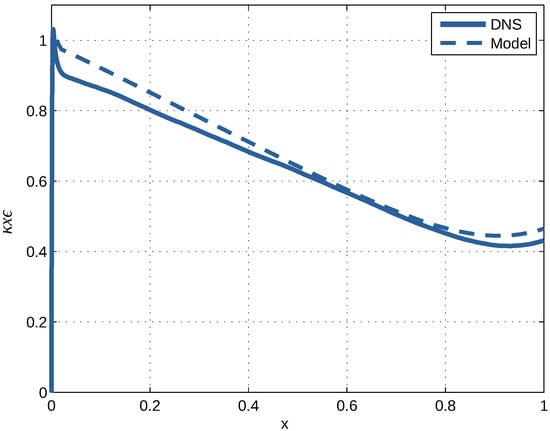

The complete specification of all coefficients in Equation (106) is achieved by determining the value of . Matching the solution for as a function of to the results of DNS reveals a value for of (see Section 3.6). This gives good agreement over the entire range of values, i.e., from the wall to the centre of the channel (see Figure 8).

3.5. Boundary Conditions

Equations (86)–(107) constitute a closed set of equations for the variables , p, , , , k, , and . The boundary conditions to be applied to the differential equations will vary from case to case, depending on the configuration under consideration. In many cases, they will be similar to those used in the basic k- model [13,14]. Along the walls, thin boundary layers are present where the present formulae, which are entirely devoted to large-scale turbulence at a high Reynolds number, do not apply. In the case of the equations for kinetic energy and energy dissipation, the area of the boundary layers can be surpassed by making use of the solutions of the log layer, which are valid just outside the boundary layer [13,14]. In the next section, this will be demonstrated for the case of channel flow.

3.6. Test Case: Channel Flow

Here, the flow between parallel plates with distance between them is considered. The mean flow is parallel to the plates in the direction . Statistical averages vary with distance from the wall. As shown in Section 2.8.1, from the conservation equations, analytical solutions can be derived [7,36]. They are valid outside the thin viscous and buffer layer at the wall and up to the symmetry axis at the centre of the channel: , where is friction Reynolds number . is assumed to be large, such that the thickness of the boundary/buffer layer, which conventionally is taken as , is small compared to the half-height of the channel H. The region is referred to as main section. It is also the region where the present model results based on the statistics of the large scales hold.

Throughout this section, we shall use the dimensionless representations of Equation (79) and drop the asterices of the dimensionless variables. According to the analytical solutions of the averaged Navier–Stokes equations we have for the dimensionless shear stress outside the boundary and buffer layer at the wall,

Another expression for the dimensionless shear stress is obtained from the present model results. For channel flow, it is obtained from Equations (89) and (93) as

where is the dimensionless wall-normal turbulent diffusion coefficient or turbulent viscosity and x is the dimensionless distance from the wall. Fluxes of kinetic energy and pressure in the wall-normal direction are obtained from Equations (99) and (110) as

where . Equating the RHS’s of Equations (108) and (109), and implementing Equation (110), yields an expression for , which upon substituting into the RHS’s of Equations (89), (93) and (96), yields the following expressions for mean squares of fluctuating velocities and mean kinetic energy:

Using Equations (88), (90) and (93), the transport of the (almost) conservative scalar (temperature, tracers, aerosols, fumes) is described by

where

The existence of negative off-diagonal diffusion coefficients seems to be confirmed by studies and measurements of transport in the atmospheric surface layer (Ref. [7], volume 1, pp. 666–669).

The differential equations for , with k specified by Equation (114), and , with k again specified by Equation (114), are in a dimensionless form, given by

where the coefficients are given by , , , and , while is specified by Equation (107). Here, , and have fixed values, while and have calibrated values. They calibrate the non-conservative scalars kinetic energy and pressure and energy dissipation according to Equations (99) and (105). Calibration took place by comparison with DNS results for turbulence flux of kinetic energy and pressure (Figure 11) and with the distribution of energy dissipation (Figure 8).

At the outer edge of the thin viscous laminar and buffer layer at the wall, the following solutions for the log layer apply: and which pertain to production equals dissipation and where is the Von Karman constant, [41]. Using Equations (109) and (110), we then obtain as boundary conditions

These boundary conditions are specified by the solutions of the log layer. The effects of the boundary and buffer layers are only apparent through the value of the shear velocity , which was used to make velocities non-dimensional. The value of the shear velocity is determined by the pressure drop in the mean flow direction for the given mean velocity. There are theoretical and experimentally confirmed relations for the relationship determining , e.g., Ref. [7], Volume 1, p. 301. At the symmetry axis of the channel, we have

The boundary value for in Equation (119) also follows from the term between brackets in energy Equation (117). The term originates from the difference between production and dissipation. Setting to zero results in the value for given by Equation (119).

Asymptotic analysis of the boundary and buffer layer reveals unspecified values for covariances at the outer edge of the layer (Ref. [7], Volume 1, pp. 279–281). Normalised with the shear velocity , these values and the distributions of with respect to x are entirely determined by the statistics of the large scales, which are governed by mean flow gradients. It is reflected in the solutions of Equations (112)–(114). Exception is a small drop in the value of 1 of near the wall, which is shown by the DNS (see Figure 8). This drop can be ascribed to viscous effects and cannot be addressed by the solution of Equation (117).

The distribution of mean velocity predicted by the model is obtained by integrating the RHS of the above equation. Because the model does not describe the velocity in the viscous and buffer layers at the wall, the integration starts at some distance from the wall, for which the position is taken. The value of to be taken at this point is . It corresponds to the value of the DNS results of , and also agrees with the values obtained from measurements (Ref. [7], Volume 1, Figure 25).

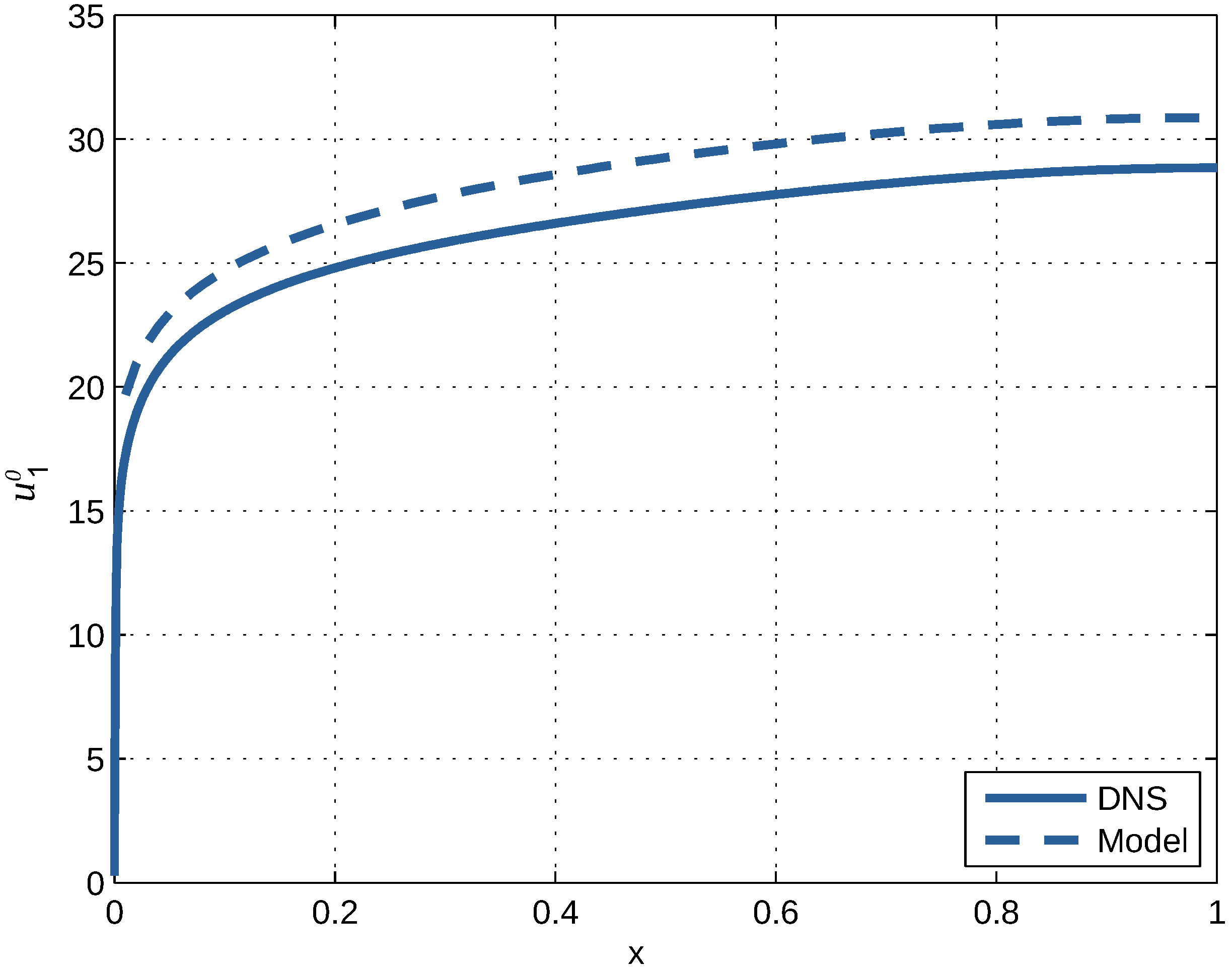

Values for and have been derived by the numerical solutions of Equations (117) and (118), subject to the boundary conditions of Equations (119) and (120). These values were used to determine the diffusion coefficient of turbulent shear stress or viscosity according to Equation (110), of the sum of turbulent fluxes of kinetic energy and pressure according to Equation (111), of the Reynolds stresses according to Equations (112)–(113), of the kinetic energy k according to Equation (114), and of the mean flow according to Equation (121). Predictions were compared with the DNS results for [17]. The comparisons are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 7.

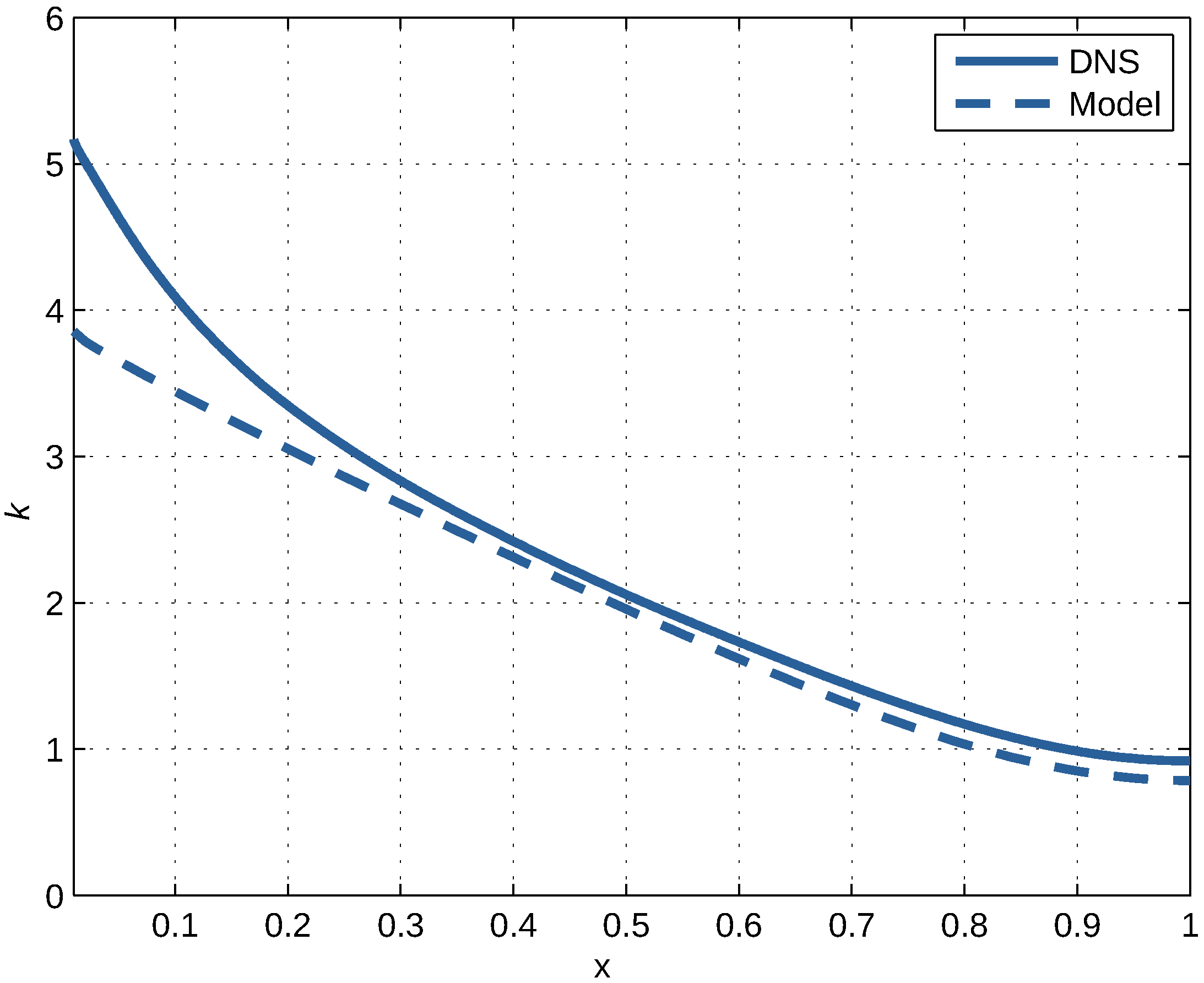

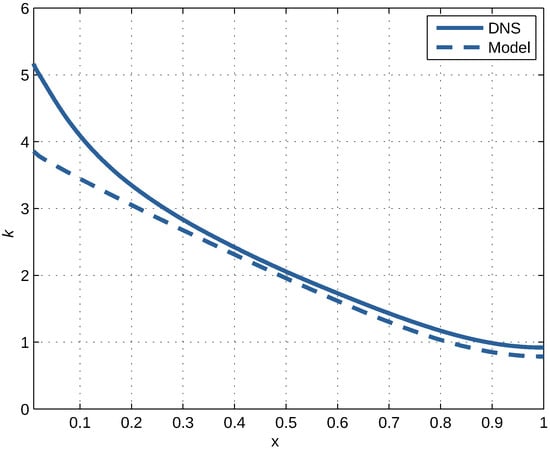

Dimensionless kinetic energy of fluctuations versus dimensionless distance from the channel wall according to DNS at and the model.

Figure 8.

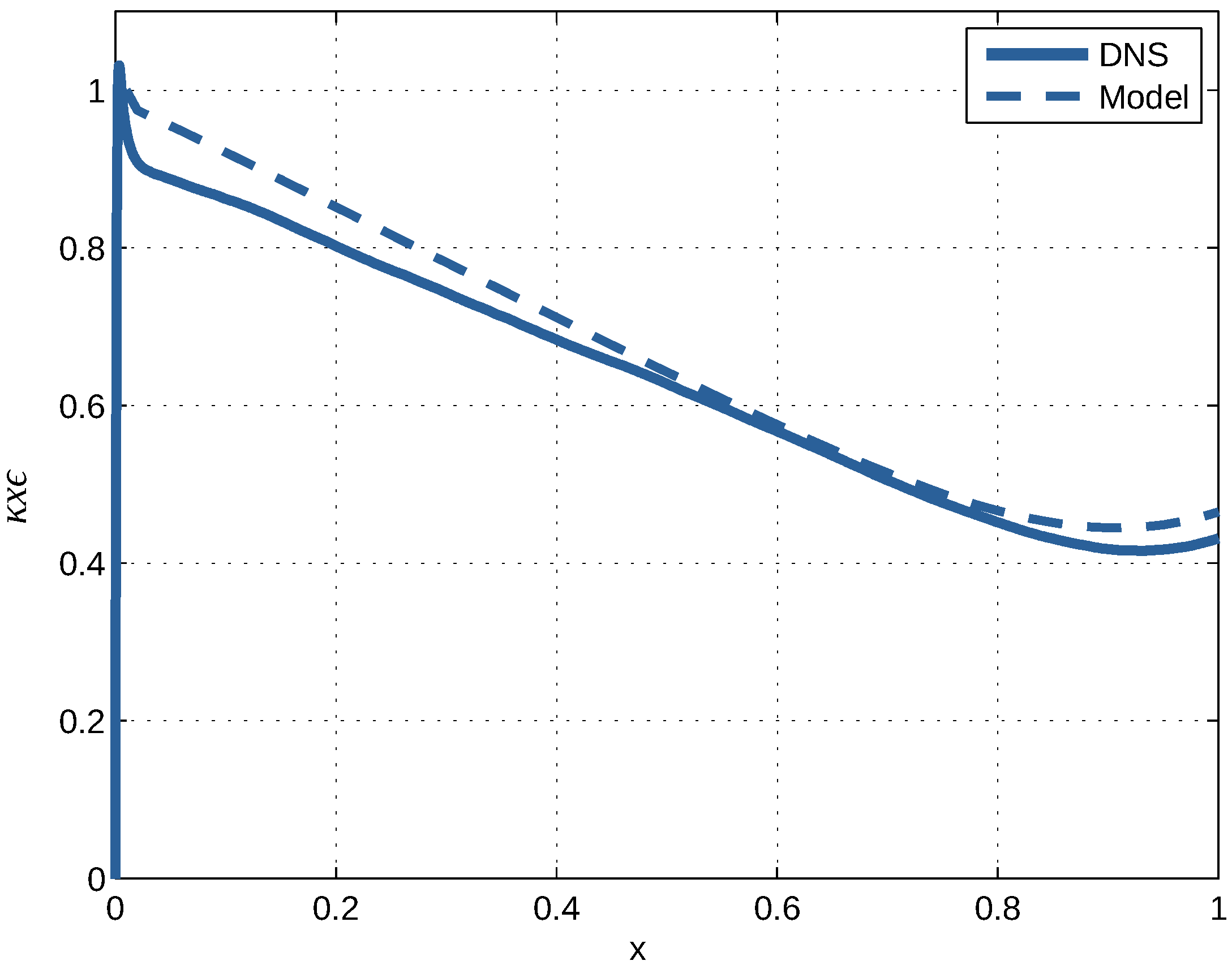

Dimensionless and normalised energy dissipation rate versus dimensionless distance from the channel wall according to DNS at and the model.

Figure 9.

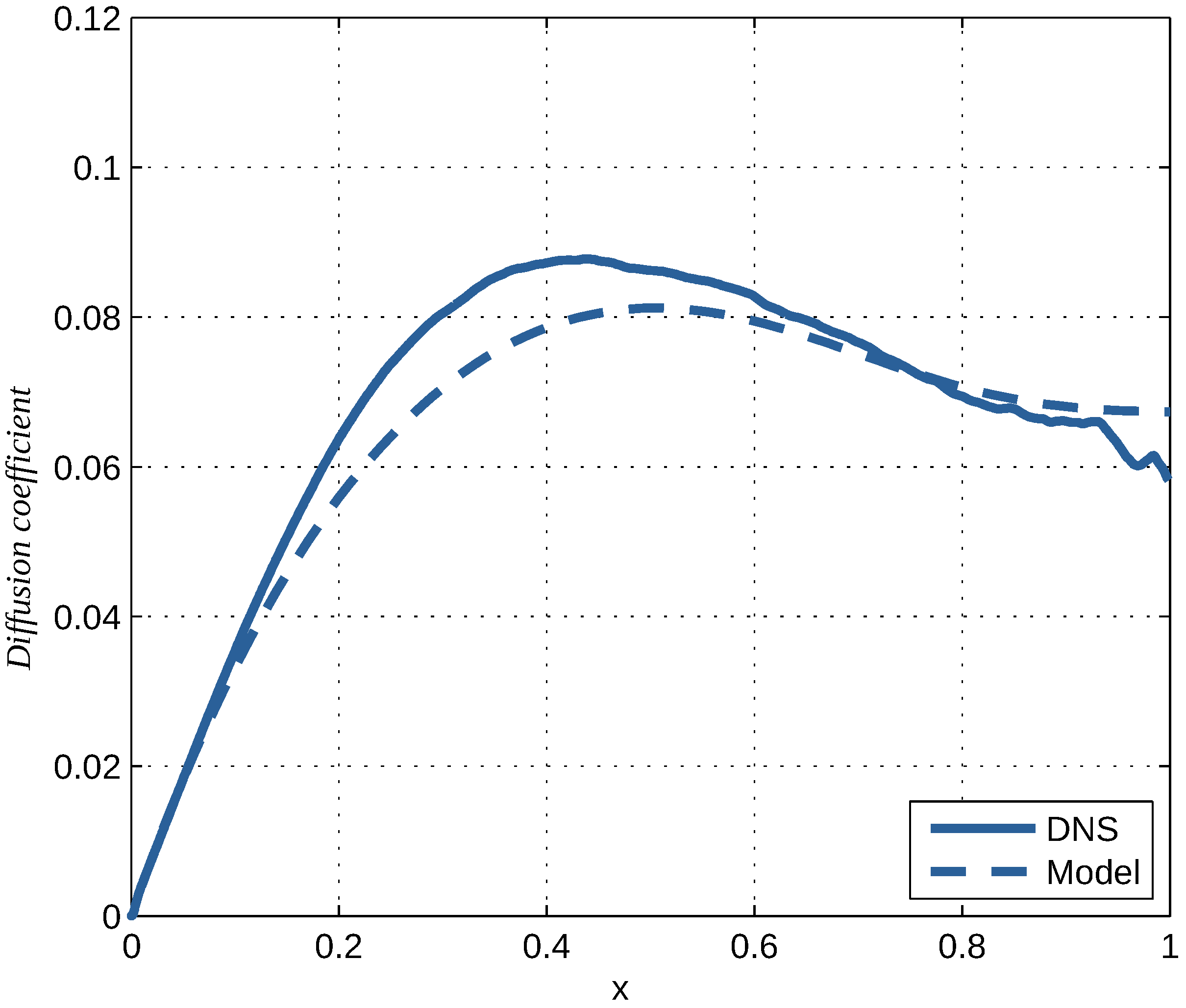

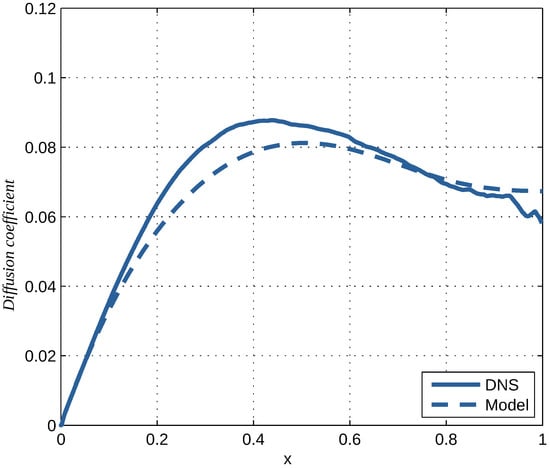

Dimensionless turbulent diffusion constant versus dimensionless distance from the channel wall according to DNS at and the model .

Figure 10.

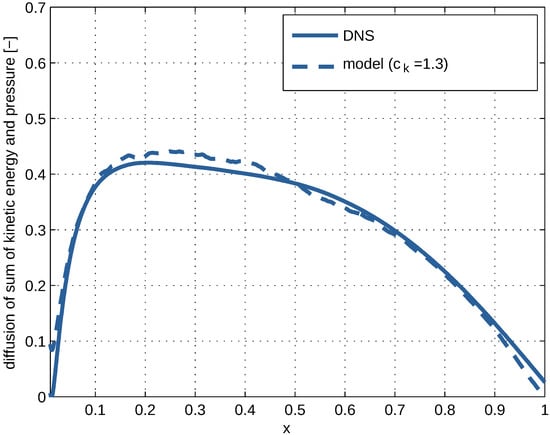

Sum of turbulent fluxes of kinetic energy and pressure (cf. Equation (99)) versus the dimensionless distance from the wall, x. The solid line is the sum according to DNS at and the dashed line is according to the model.

Figure 11.

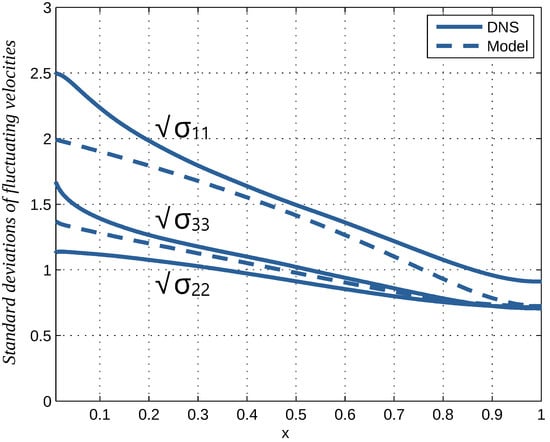

Dimensionless standard deviations of fluctuating velocities versus dimensionless distance from the channel wall according to DNS at and the model.

Figure 12.

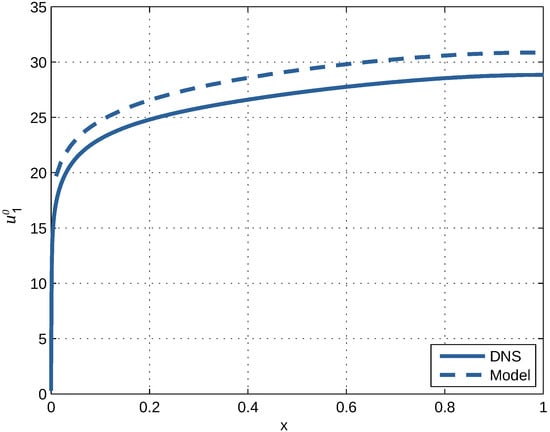

Dimensionless mean velocity versus dimensionless distance from the channel wall according to DNS at and the model.

From the figures, it is seen that model results show good to satisfactory agreement with the DNS. Deviations are largest in case of the diagonal components of the Reynolds stresses shown in Figure 11. The anisotropy apparent in deviations from the isotropic value of these stresses is determined by the higher-order contributions in the expansion, which are more prone to errors by truncation.

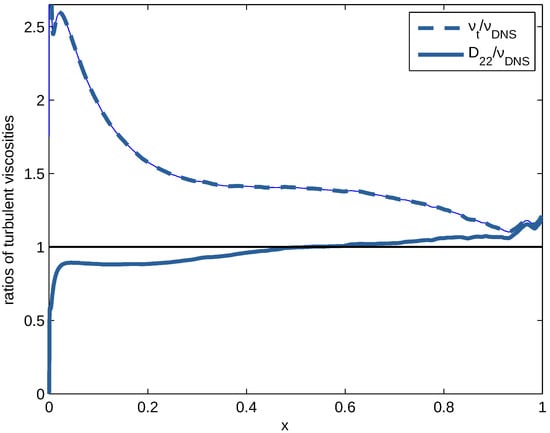

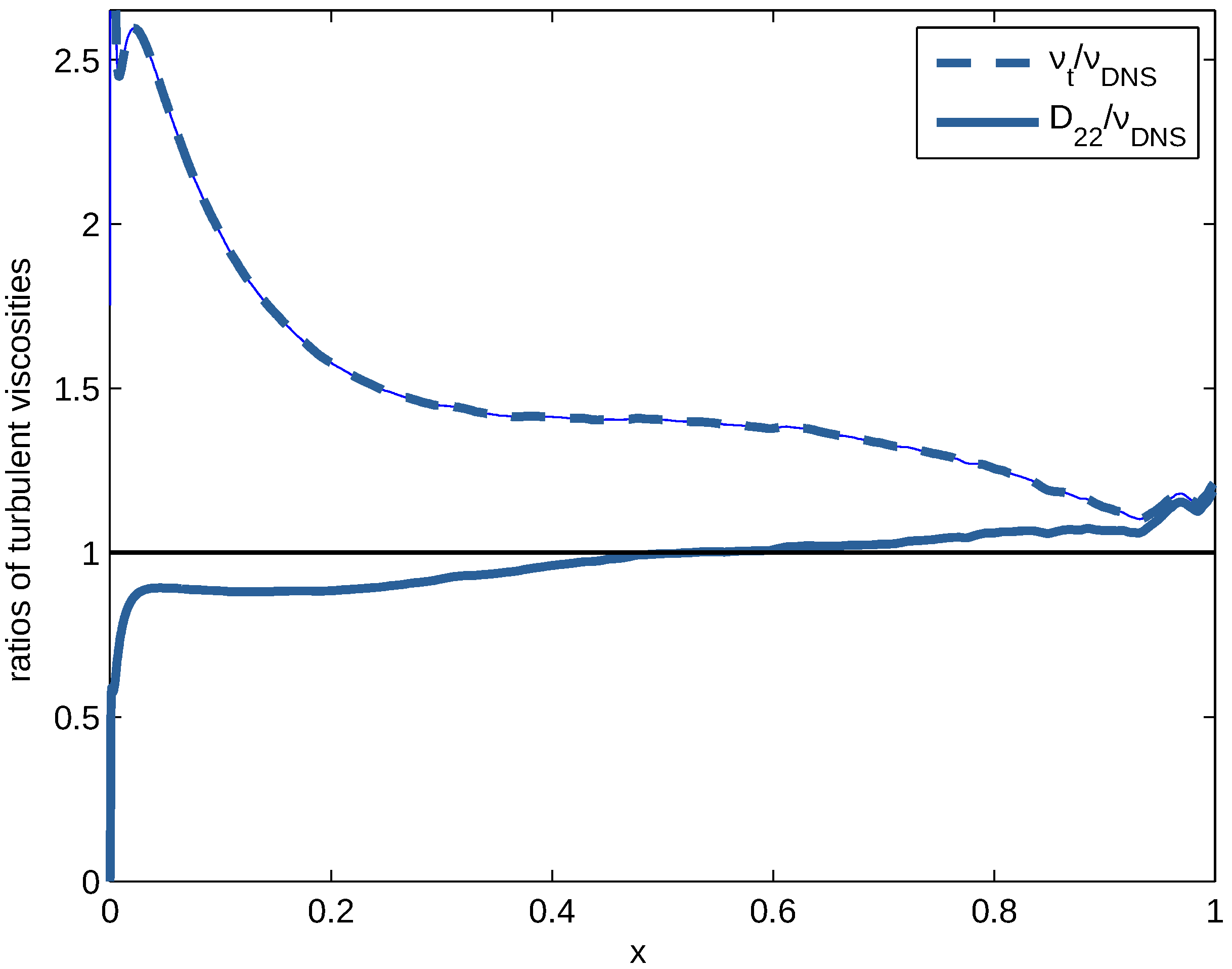

The present results represent a significant improvement to those obtained from the basic k- model [15]. This widely used model is based on semi-empirical formulations for turbulent fluxes which appear not to match the DNS results [15]. An illustration is presented in Figure 13. A remarkable deviation is seen in the value of the diffusion coefficient of the basic k- model in the outer half of the channel. In this area, the turbulence is similar to that of the atmospheric layer. It governs the dispersion of smoke from chimneys (Figure 13), of radioactive aerosols emitted from exploding nuclear power stations, the spread of wildfires, etc. In contrast with the basic k- model, the presented model predicts turbulent diffusion in this area correctly. The underlying formulae were derived from general principles of statistical physics and turbulence at a large Reynolds number. They provide a more solid means for calculating the statistics of turbulent flow and dispersion. Adapting the numerical codes of the basic k- model to the equations of the present model is straightforward.

Figure 13.

Ratio of turbulent viscosity of the present model to that of DNS at (lower line) and ration of turbulent viscosity of the basic k- model to that of DNS at (upper line) versus dimensionless distance from the wall x.

Figure 13.

Ratio of turbulent viscosity of the present model to that of DNS at (lower line) and ration of turbulent viscosity of the basic k- model to that of DNS at (upper line) versus dimensionless distance from the wall x.

4. Conclusions

The starting point of the presented analysis was the formulation of a Langevin equation for the statistical representation of the velocity of a marked fluid particle and its displacement. The formulation applies to turbulence at a large Reynolds number as conventionally encountered in practice. It includes the inertial subrange representation according to Kolmogorov theory. Explicit expressions are obtained through perturbation expansions using the inverse of the Kolmogorov constant as the small parameter: . The first term corresponds to Hamiltonian dynamics and enables the application of Onsager symmetry to specify the damping term in the Langevin equation. The next term is specified upon applying Thomsons mixing principle.

Because of small fluid particle displacement during velocity correlation time, the Lagrangian formulation of fluctuating terms can be transformed into Eulerian ones at each point of marking in the Lagrangian representation. It results in expressions in a closed form for the turbulent diffusion of momentum and of conservative scalars such as temperature in almost incompressible flow, fumes, and aerosol particles. In contrast with the expressions used in traditional empirically based models, the expressions are of a general nature, do not contain fit constants, and are not limited to specific cases. They compare in a favourable manner with the results of direct numerical simulations (DNS) of the Navier–Stokes equations of strongly inhomogeneous anisotropic channel flow (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13). This contrasts with the results from the widely used empirical k- model, which show remarkable deviations from DNS (Ref. [15] and Figure 13).

The expressions for diffusion are included in a closed set of equations containing the averaged version of the Navier–Stokes equations, of average conservation of fluctuating kinetic energy k and of average turbulent dissipation rate . The diffusion expressions of the non-conservative scalars k and in these equations are represented by those of a conservative scalar provided with a correction factor. The value of the correction factor is deduced from a comparison with the DNS of channel flow. Good agreement between diffusion expressions over the entire distance from the wall is observed using a constant value of the calibration factor. It facilitates the application of the model equations to flows in channels and configurations with a similar flow structure such as turbulent boundary layers and the atmospheric surface layer along the Earth.

The magnitude of the mean flow gradient and the degree of anisotropy in the channel flow change greatly with distance from the channel wall, a feature seen in many other cases of turbulent flow. The insensitivity of the value of the calibration constants of these strong changes suggests that the proposed functional relationship for the diffusion of k and has wider applicability than that of the flow in channels and related cases. It opens the door to the widespread application of the model equations, such as in the cases shown in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3, without a direct need to adapt the calibration factors used in the diffusion representations of k and of channel flow.

In general, predictions of values of statistical parameters by the model show good to satisfactory agreement with those of DNS of channel flow. They provide a significant improvement to the results from the widely used basic k- model, which show remarkable differences. At the same time, it is noted that the mathematical structure of the present model does not deviate significantly from that of the basic k- model. Implementation of the present model equations in a CFD code derived from k- software should be an easy task to be taken up by CFD developers.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank G.M. Janssen for preparing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author J.J.H.(Bert) is principal scientist at the company Romico Hold VBA. The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Townsend, A.A. The Measurement of double and triple correlation derivatives in isotropic turbulence. Math. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 1947, 43, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, J. The Structure of Turbulence in Fully Developed Pipe Flow; National Advisory Committee for Aeronaut Technical Report No. 1174; National Committee for Aeronautics: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, J.F.; McKeon, B.J.; Jiang, W.; Smits, A.J. Scaling of the stream-wise velocity component in turbulent pipe flow. J. Fluid Mech. 2004, 508, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebanoff, P.S. Characteristics of Turbulence in a Boundary Layer with Zero Pressure Gradient; National Advisory Committee for Aeronaut Technical Report No. 1247; National Committee for Aeronautics: Washington, DC, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Voth, G.A.; Porta, A.L.; Crawford, A.M.; Alexander, J.; Bodenschatz, E. Measurements of particle acceleration in fully developed turbulence. J. Fluid Mech. 2002, 469, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Karman, T. Mechanische Ähnlichkeit und Turbulenz; Weidmannsche Buchh.: Hildesheim, Germany, 1930; pp. 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Monin, A.S.; Yaglom, A.M. Statistical Fluid Mechanics; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Boussinesq, J. Théorie de l’écoulement tourbillant (theories of swirling flow), mém. prés. par div. savantsa l’acad. Sci. Paris 1877, 24, 726–736. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.I.I. Eddy motion in the atmosphere. Phil. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1915, 215, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prandtl, L. Bericht über Untersuchungen zur ausgebildeten Turbulenz. J. App. Math. Mech. 1925, 5, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanjalić, K.; Launder, B. Modelling Turbulence in Engineering and the Environment: Second-Moment Routes to Closure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P.S.; Wallace, J.K. Turbulent Flow: Analysis, Measurement and Prediction; Wiley: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ansys Fluent 12.0. Theory Guide, Section 4 Turbulence, 4.4.1 Standard k-ϵ Model. Available online: https://afs.enea.it (accessed on 23 January 2009).