Abstract

Four endophytic fungi were isolated from the medicinal plant, Catharanthus roseus, and were identified as Diaporthe spp. with partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF1), beta-tubulin (TUB), histone H3 (HIS), calmodulin (CAL) genes, and rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region (TEF1-TUB-HIS--CAL-ITS) multigene phylogeny suggested for species delimitation in the Diaporthe genus. Each fungus produces a unique mixture of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with an abundant mixture of terpenoids analyzed by headspace solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fiber-GC/MS. These tentatively-detected terpenes included α-muurolene, β-phellandrene, γ-terpinene, and α-thujene, as well as other minor terpenoids, including caryophyllene, patchoulene, cedrene, 2-carene, and thujone. The volatile metabolites of each isolate showed antifungal properties against a wide range of plant pathogenic test fungi and oomycetes, including Alternaria alternata, Botrytis cinerea, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Fusarium graminearum, and Phytophthora cinnamomi. The growth inhibition of the pathogens varied between 10% and 60% within 72 h of exposure. To our knowledge, the endophytic Diaporthe-like strains are first reported from Catharanthus roseus. VOCs produced by each strain of the endophytic Diaporthe fungi were unique components with dominant monoterpenes comparing to known Diaporthe fungal VOCs. A discussion is presented on the inhibitive bioactivities of secondary metabolites among endophytic Diaporthe fungi and this medicinal plant.

1. Introduction

Many plants remain unexplored for their endophytic fungi and the potentially important products that they may produce [1]. Catharanthus roseus is known as a pharmaceutical plant containing rich anticancer alkaloids. The extracts of many organs of this plant also exhibit antimicrobial effects [2,3,4,5,6]. It turns out that Catharanthus roseus is host to a diverse group of endophytic fungi [7,8,9,10]. Some endopytic fungi were found to produce several metabolites biosynthesized by the host Catharanthus roseus. The endophytic fungi Curvularia sp. CATDLF5 and Choanephora infundibulifera CATDLF6 isolated from leaf issues were able to enhance leaf vindoline production content of C. roseus cv. prabal by 2.29–4.03 times through root inoculation [8]. Endophytic Fusarium spp. from stem issues seemed to facilitate the host plant to produce secondary metabolites [9]. Additionally, some endophytic fungi from the plant produced antimicrobial compounds. For example, the compounds hydroxyemodin, citreoisocoumarin, citreoisocoumarinol, and cladosporin from endophytic fungi of leaves were effective in inhibiting fungal pathogens [10]. Diaporthe are commonly found as endophytes in a wide range of plants around the world [11,12,13,14,15]. These endophytes are prolific producers of antimicrobial metabolites [15,16]. D. endophytica and D. terebinthifolii, isolated from the medicinal plants Maytenus ilicifolia and Schinus terebinthifolius, had an inhibitory effect against Pseudomonas citricarpa in vitro and in detached fruits [12,13]. The crude extracts of Diaporthe sp. MFLUCC16-0682 and Diaporthe sp. MFLUCC16-0693 exhibited notable antibacterial and antioxidant activities [14]. An endophytic Phomopsis (asexual state of Diaporthe) fungus isolated from the stems of Ficus pumila, exhibited broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative human and phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi [15]. Thus, the genus Diaporthe is a potential source of metabolites that can be used in a variety of applications [14]. However, endophytic Diaporthe fungi have not been recorded from Catharanthus roseus to the present.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have noted biofumigative effects especially from the endophytic fungus—Muscodor albus [17]. These observations opened a unique venue for the application of endophytic microorganisms to the ecological-friendly biocontrol of pests [17]. The inhibitive bioactive compounds were also found in a few isolates of endophytic Diaporthe [18]. An endophytic Phomopsis isolate of Odontoglossum sp. in Northern Ecuador was reported to produce a unique mixture of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with sabinene, 1-butanol, 3-methyl; benzeneethanol; 1-propanol, 2-methyl, and 2-propanone. The VOCs showed antifungal bioactivities on a wide range of plant pathogenic fungi, such as Sclerotinia, Rhizoctonia, Fusarium, Botrytis, Verticillium, Colletotrichum and oomycetes Pythium, and Phytophthora [18]. The PR4 strain of an endophytic Phomopsis obtained from the medicinal plant Picrorhiza kurroa also produced a unique set of bioactive VOCs inhibitive to plant pathogenic fungi growth. The dominant compounds in VOCs of the PR4 strain were reported as menthol, phenylethyl alcohol, isomenthol, β-phellandrene, β-bisabolene, limonene, 3-pentanone and 1-pentanol [19]. In view of the antimicrobial properties of the extracts from the medicinal plant Cantharatus roseus, and limited knowledge on endophytic Diaporthe species in this host, we conducted an investigation on the antifungal bioactivity of VOCs from four endophytic Diaporthe strains isolated from wild Catharanthus roseus in China. The combined sequences of five loci, elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF1), beta-tubulin (TUB), histone H3 (HIS), calmodulin (CAL) genes, and the rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region were used for the strains’ phylogenetic analyses within genus Diaprothe. Inhibitory bioactivity executed volatile organic compounds from the strains were observed on growths of tested plant pathogens in co-culture. Active components of VOCs were analyzed and inferred using headspace solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fiber-GC/MS and based on their reported properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Endophytic Fungal Isolation

The four endophytic fungi were isolated from wild plants, Catharanthus roseus, growing in the National Natural Conservation Area of TongGu Mountain, located in Wenchang city of Hainan Province. Several stem segments (5–10 cm in length) were collected for the eventual isolation of endophytes. Retrieving endophytic fungi followed a previously described procedure [20]. Briefly, the external tissues of segments were cleaned with tap water and scrubbed with 70% ethanol prior to excision of internal tissues. Then the segments were excised into smaller fragments about 0.2–0.5 cm in length. The fragments were thoroughly exposed to 75% ethanol for 60 s, 3% NaClO for 90 s, and sterile water for 60 s by agitation. The fragments at the last step were drained on sterile filter papers and put on water agar in Petri plates for growing endophytes. Further, pure isolates were obtained in potato dextrose agar media and stored on sterilized, inoculated barley seeds at 4 °C and −80 °C. The four fungi of interest were assigned with our laboratory acquisition number-ID FPYF3053-3056 and deposited in China Forestry Culture Collection Center assigned IDs of CFCC 52704-52707.

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR, and Sequencing

Fungal genomic DNA was extracted from colonies growing on PDA for one week with the CTAB procedure [20]. The extracted DNA was further purified through Mini Purification kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) following the manufacture’s protocols. The DNA quality and concentration were determined with a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) after the DNA was checked with Genegreen nucleic acid dye (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd.) in an electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel stained under ultraviolet light. The extracted DNA was used as a template for the further PCR amplification ITS sequence and TEF1, CAL, TUB, and HIS genes regions. The primers were used to amplify the ITS targets, namely, the ITS1 and ITS4 [21], TEF1 with EF1-688F/EF1-1251R [22], CAL with CL1F/CL2A or CAL563F/CL2A [23], TUB with T1/Bt-2b or Bt2a/Bt-2b [24,25], and HIS with HISdiaF/HISdiaR, sequences that were 5′-GGCTCCCCGYAAGCAGCTCGCCTCC-3 and 5′-ATYCCGACTGGATGGTCACACGCTTGG-3, respectively. All PCR reaction mixtures and conditions were followed as per the Taq PCR MasterMix kits (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacture’s protocol. A PCR reaction system consisted of 0.5 µL of each primer (10 µM), 3 µL (15–80 ng) of DNA template, 12.5 µL of 2 × Taq PCR MasterMix (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd.), and 8.5 µL of double distilled water in total of 25 µL. The ITS thermal cycling program was as follows: 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 94 °C for 60 s, 55 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension step of 72 °C for 5 min. The annealing temperature at 55 °C for 45 s was changed in this program for CAL, β-tubulin and TEF amplification. For amplification of HIS, the program was changed with a cycling program of 32 cycles and an annealing temperature at 55 °C for 60 s. PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gels mixed with Genegreen Nucleic Acid Dye and purified with a quick Midi Purification kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co., Ltd.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing PCR products were cycle-sequenced the BigDye® Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in an ABI Prism 3730 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) at Biomed Company in Beijing. Then sequence data collected by ABI 3730 Data collection v. 3.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and ABI Peak Scanner Software v. 1.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), were assembled with forward and reverse sequences by BioEdit. The gene sequences were submitted and awarded access numbers in GenBank of NCBI (Table 1).

Table 1.

Access numbers for ITS, translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF1), beta-tubulin (TUB), histone H3 (HIS), calmodulin (CAL) genes region sequences of the four endophytic Diaporthe fungi in the GenBank of NCBI.

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

In order to determine the phylogenetic locations of the four isolates within the Diaporthe genus, 143 reference taxa [26] (Table 2) together with the four isolates were used for building a phylogenetic a tree with Diaporthella corylina as a root outgroup species [23]. The evolutionary relationships were taken on a five-gene concatenated alignment of ITS, TEF1, CAL, HIS, and TUB regions by maximum likelihood (ML) and maximum parsimony (MP) phylogenetic analyses. Sequences were aligned using the MAFFTv.7 online program with default parameters [27]. A partition homogeneity test implemented in PAUP* v.4.0 (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, USA) was applied to determine if the five sequence data could be combined. The best evolutionary model for the partitioning analysis was performed on the concatenated sequences by PartitionFinder 2.1.1 [28]. A concatenated alignment for the five gene regions was made from SequenceMatrix [29]. The inference methods of maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony in Mega 6.0 [30] were applied to estimate phylogeny for the concatenated sequences, with the evolutionary models GTR and AIC for ML and MP, respectively, with a bootstrap support of 1000 replicates. Evidence on the trees were visualized and edited by TreeGraph 2 [31].

Table 2.

Reference sequences of Diaporthe strains with NCBI access numbers for phylogenetic analysis.

2.4. Antifungal Activity Tests for Fungal VOCs

The antifungal activity of the VOCs was determined by the methods previously described [17,18,20]. The four endophytic fungal strains of Diaporthe and targeted plant pathogenic microorganisms were paired opposite to each other in Petri plates containing PDA with a diameter of 90 mm. The agar was divided into two halves by removing a 2 cm wide strip in the center. An endophytic test fungus was inoculated onto one half-moon of the agar and incubated at 25 °C for five days for optimum production of volatile compounds before the antagonism bioassay. A test pathogen was inoculated onto the opposite half-moon part of the agar at the fifth day. The plates were then wrapped with parafilm and incubated at 25 °C in dark for 72 h. Growth of filamentous pathogenic fungi were quantitatively assessed after 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h based on multiple measurements of growth relative to controls, as described previously [17,18]. The colony diameter was measured in an average of four diameters on hours 24, 48, and 72 h, disregarding the initial inoculum size. Percentage of growth inhibition was calculated as the formula: |(a − b/b)| × 100, a = mycelial colony diameter in control plate; b = mycelial colony diameter in the antagonism treatment plate. Statistical significance (p < 0.01) was evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Tukey 5% test. Antifungal activity of VOCs was tested against the plant pathogenic fungi Alternaria alternata, Botryosphaeria dothidea, Botrytis cinerea, Cercospora sp., Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Fusarium graminearum, Sphaeropsis sapinea, and Valsa sordida, in addition to the oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi. All tests were made in quintuplicate. Control cultures were obtained by growing each plant pathogen alone, under the same conditions.

2.5. Qualitative Analyses on Volatiles of the Four Endophytic Cultures

VOCs in the air space above the endophytic fungal colonies grown for five days at 25 ± 2 °C on PDA were analyzed using the solid phase microextraction (SPME) fiber technique according to previously described protocols [17,18,20]. Control PDA Petri plates not inoculated with the strain was used to subtract compounds contributed by the medium. All treatments and checks were done in triplicate. A fiber syringe of 50/30 divinylbenzene/carboxen on polydimethylsiloxane (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was conditioned for 40 min at 200 °C, exposed to the vapor phase inside Petri during 40 min through a small hole (0.5 mm in diameter) drilled on the sides of the Petri plate. The fiber was directly inserted into the TRACE DSQ inlet (Thermo Electron Corporation, Beverly, MA, USA), at 200 °C, splitless mode. The desorption time was 40 s and the desorbed compounds were separated on a 30.0 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm, HP-5MS capillary column, using the following GC oven temperature program: 2 min at 35 °C up to 220 °C at 7 °C/min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The electronic ionization energy was 70 eV and the mass range scanned was 41–560 uma. The scan rate was 5 spec/s. Transfer line and ionization chamber temperatures were 250 °C and 200 °C respectively. Tentative identification of the volatile compounds produced by the four endophytic Diaporthe fungi was made via library comparison using the NIST database and all chemical compounds were described in this report following the NIST database chemical identity. Tentative compound identity was based on at least a 70% quality match with the NIST database information for each compound. Data acquisition and data processing were performed with the Hewlett Packard ChemStation software system (Version 2.0, Scientific Instrument Services, Inc., Ringoes, NJ, USA). Relative amounts of individual components of the treatments were determined and expressed as percentages of the peak area within the total peak area and as an average of the three replicates.

3. Results

3.1. The Identification on the Four Endophytic Isolates within the Diaporthe Genus

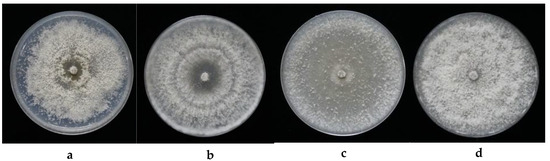

Each of the four isolates falling within the genus Diaporthe were further defined using molecular analyses as they appeared different, morphologically (Figure 1). For instance, strain FPYF3053 had compact mycelia with crenate margins, these colonies developed a brownish yellow pigmentation in the center on the underside having a growth rate of 18.3 mm day−1 (Figure 1a). On the other hand, strain FPYF3054 had aerial mycelium forming concentric rings with grey and dark pigmentation at the center showing a growth rate of 30.97 mm day−1 (Figure 1b). Strain FPYF3055 had vigorously-growing aerial hyphae near the margin, but loose hyphae scattered inside with aging, with a growth rate of 23 mm day−1 (Figure 1c). Finally, strain FPYF3056 had a compact mycelium with a crenate margin, but no pigmentation with a growth rate of 21.7 mm day−1 (Figure 1d).

Figure 1.

The colony cultures for the four endophytic Diaporthe fungi and their plant host. (a) FPYF3053; (b) FPYF3054; (c) FPYF3055; and (d) FPYF3056.

A combined alignment of five loci ITS, TUB, TEF1, HIS, and CAL was used for ML and MP phylogenic analyses. Based on the multi-locus phylogeny (Figure 2), the four endophytic Diaporthe strains could not be placed in one species only because they are distinct from each other and from all reference species listed (Table 2, Figure 2). Strains FPYF3055 and FPYF3056 were clustered by giving a high bootstrap support (BS = 82) from MP inference (Figure S1) while both separated from each other in ML inference (Figure S2). The reference sequences used to construct the phylogenetic tree were listed in Table 2 with their Genbank accession numbers. The alignment was uploaded in Treebase assigned with SI 22757.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree based on combinedITS, CAL, TEF1, HIS, and TUB sequence alignment generated from a maximum parsimony and maximum likelihood analyses. Values near the branches represent parsimony/likelihood bootstrap support values (>70%), respectively. The tree is rooted with Diaporthella corylina. The four endophytic isolates were each named with strain ID marked green box. Compressed branches were used for saving space. The complete phylogenetic trees of MP and ML can be found in Figures S1 and S2, respectively.

3.2. The VOCs’ Bioactivities of the Four Diaporthe Strains against Plant Fungal Pathogens

All of the four strains were observed to inhibit the growth of nine selected fungal pathogens by producing volatile compounds in the PDA medium (Table 3). The nine pathogens, Alternaria alternata, Botryosphaeria dothidea, Botrytis cinerea, Cercospora asparagi, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Fusarium graminearum, Phytophthora cinnamomi, Sphaeropsis sapinea, and Valsa sordida, are important causal agents to major trees, such as poplars and pines, or agricultural crops in China and elsewhere. All FPYF strains showed different inhibitory activities along the measurements, an exception was observed for the case of strain FPYF3053, which promoted the growth of Phytophthora cinnamomi (Table 3). Furthermore, all selected pathogens, except V. sordid, achieved obvious growth inhibition over around 10% during the testing period. After 24 h, B. cinerea was the most sensitive to VOCs emitted by all endophytic strains, reaching percent inhibitions of more than 55% when dual cultured with each strain. B. dothidea and A. alternata were highly sensitive to VOCs of all the endophytic strains, getting percent inhibitions of more than 30% with an exception to 28% of A. alternata in VOCs of the strain FPYF3053. V. sordida had the least sensitive or insensitive performance in VOCs from all the strains, showing percent inhibitions around 3% when dual cultured with FPYF3056. The inhibitive intensity of FPYF strains’ VOCs on growth of pathogens decreased in times to most duel cultures. The maximum drop of the intensity was by 31% in percent inhibition on the pathogen B. cinerea duel culturing with strain FPYF3056. The obvious increase in intensity occurred in the pathogen F. graminearum duel culturing with FPYF3055 and FPYF3056, increasing by around 10% during 72 h. Some pathogens grew fast without percent inhibition records after 24 h (V. sordida) or 72 h (B. dothidea and F. graminearum).

Table 3.

Growth inhibition percentage of plant pathogens by VOC bioassays of four Diaporthe strains. Percent of inhibition is shown as the means of four measurements of diameters with standard deviation (n = 4).

3.3. The Qualification on VOCs of the Four Endophytic Diaporthe Strains

Each of the Diaporthe isolates showed a unique VOC profile as measured by SPME (Table 4). Nineteen VOC components from the four fungi were identified and seven compounds were unidentified according our set standard of a 70% quality match with the GC-MS. Generally, the terpenoids were the major components in the VOCs of each strain. The main terpenes included α-thujene, β-phellandrene, γ-terpinene, l-menthone, cyclohexanol, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)-, α-muurolene. The amounts of each component of these monoterpenes had a relative area over 10% of the total of its VOCs. There also existed other minor terpenoids at very low amounts, including carene, α-phellandrene, thujone, caryophyllene, patchoulene, etc. Two monoterpenes, β-phellandrene and α-muurolene, and a chemical biphenylene,1,2,3,6,7,8,8a,8b-octahydro-4,5-dimethyl, which were detected in VOCs of all four strains. Four chemicals were common to VOCs from FPYF3053, FPYF3055, and FPYF3056, including α-thujene, 1,3-cyclohexadiene, 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)-, γ-terpinene and 3-cyclohexen-1-ol, and 4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-,(R)-. However, each strain produced a unique mixture of volatile organic compounds. The strain FPYF3053 produced 15 volatile compounds with three prominent components, α-thujene, β-phellandrene, and α-muurolene. FPYF3054 was able to synthesize eight compounds with three prominent components of β-phellandrene, l-menthone, and cyclohexanol,5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)- in VOC mixtures. Strains FPYF3055 and 3056 generated relatively close chemical compositions in amount and quality of VOCs compared to FPYF3053 and FPYF3054. However, FPYF3055 had three prominent components, α-thujene, γ-terpinene, and 3-cyclohexen-1-ol,4-methyl-1-(1-methylethyl)-,(R)-, in 12 compounds of the VOCs, while FPYF3056 had three prominent components—namely α-thujene β-phellandrene, and γ-terpinene—of 13 compounds in its VOCs.

Table 4.

Chemical composition of volatiles obtained from mycelial cultures of the four endophytic Diaporthe fungi using solid–phase microextraction (SPME).

4. Discussion

4.1. Endophytic Diaporthe spp. from Catharanthus roseus

Four isolates of endophytes in the genus Diaporthe were obtained from the medicinal plant Catharanthus roseus growing in a conservation area of Southern China. In order to best distinguish these individual organisms they were subjected to a combined analysis of five-loci alignment of TEF1-TUB-CAL-HIS-ITS which gave a more robust isolate identification [23]. Adding our four endophytic isolates did not affect the congruency in each locus, partition homogeneity for the combination and the best evolutionary model for the five-locus concatenated alignment reported. Diaporthe fungi are one of the most common endophytic fungal communites found in plants [11]. However, the previous work on endophytic fungi from C. roseus [7,8,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42] did not record strains of the Diaporthe genus. Alternaria alternata was determined as the dominant endophytic species in leaf tissue of C. roseus along with associated fungi from the following genera, Aspergillus, Fusarium, Penicillium, and Helminthosporium [33]. In addition the endophytes of root tissue appeared including Colletotrichum sp., Macrophomina phaseolina, Nigrospora sphaerica, and Fusarium solani [7]. Other isolated endophytic fungi from this plant included Colletotrichum truncatum, Drechsclera sp., Cladosporium sp., and Myrothecium sp. [43]. To our four Diaporthe strains, no reproductive structures were obtained in the employed conditions. They were designated Diaporthe sp. strains (FPYF3053-3056) without spore characterization strictly using phylogenetic analysis. The strains seemed not to share a close phylogenetic relationship to any other species based on the five-locus alignment study (Figure 2, [12,23,26]). The robust inference on the strains will take place when fruits bodies appear combined with full species phylogeny in the genus Diaporthe.

4.2. VOCs Antifungal Effects of Endophytic Diaporthe spp. from Catharanthus roseus

Compounds extracted from Catharanthus roseus [4,5] and extracts from some endophytes of this plant [10,44] have been shown to have antimicrobial bioactivities to some human microbial pathogens and plant fungal pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida albicans, etc. However, the VOCs or essential oils from Catharanthus roseus in the literature is scarce results on antimicrobial activities [45,46]. The previous work on the other endophytic fungi of this host plant did not consider that VOCs of the endophyte may have antimicrobial activities [7,8,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. However, this work shows that VOCs produced by four endophytic Diaporthe fungi from the plant are able to functionally inhibit the growth of a number of specifically-targeted fungal pathogens (Table 3).

In the past there have been three endophytic Diaporthe strains recorded with their VOCs [18,19,47]. Two of them were reported to be inhibitory to plant pathogens [18,19]. One strain PR4 was isolated from a medicinal plant growing in Kashimir, Himalayas [19]; the other strain EC-4 was isolated from Odontoglossum sp. in Northern Ecuador [18]. With our four strains, the volatile compounds from endophytic Diaporthe fungi varied in degrees of inhibition against selected pathogenic fungi and test timings depending on the endophytic strain (Table 3 and Table 5). However, the maximal inhibition of fungal growth of Diaporthe was from strain PR4, which reduced growth of Rhizoctonia solani by 100%. FPYF strains’ and EC-4 VOCs also appeared effective in the inhibition of growth of Botrytis cinerea by more than 30% with a maximal of 50.42 ± 1.8%. During the test course of 72 h, to most cases, FPYF strains’ VOCs showed strong bioactivities in the first day and then decreased inhibition on the pathogens in following two days (Table 3). PR4 VOCs were effective in reducing radial growth of Pythium ultimatum by 13.3%; EC-4 VOCs were effective in reducing radial growth of Pythium ultimatum, Phytophthora cinnamomi, and Phytophthora palmivora by 59.1 ± 0.9%, 42.0 ± 0.5%, and 5.6 ± 0.5%, respectively. FPYF3054-3056’s VOCs were effective against Phytophthora cinnamomi in a range of 25.21 ± 4.3 ~ 11.32 ± 4.2%. The alcohol compounds such as 1-propanol,2-methyl- and 1-butanol,3-methyl- might made the oomycete P. cinnamomi more sensitive to EC-4’s VOCs [18], which were lack in VOCs of all FPYF strains (Table 4). The two alcohol compounds had antimicrobial activities in VOCs of endophytic Phomopsis sp. strain EC-4 [18]. The sensitivity of the pathogen F. graminearum to VOCs from Diaprothe spp. might be analogous even though the VOCs components were not similar among Diaprothe strains. Two Diaporthe strains FPYF3053, 3055 (Table 2) and Diaporthe strain PR4 [19] had percent inhibition of F. graminearum growth of around 30% under their VOCs bioactivities. However, only beta-phellandrene was a common compound found in VOCs among them (Table 4, [19]). Contrast to cytochalasins as a predominantly common component in soluble secondary metabolites of Diaporthe strains [16], the genus-specific or predominant conserved components of fungal VOCs of genus Diaporthe should be proposed to illustrate further. The experimental data suggests that the VOCs of FPYF strains are both biologically active and biologically selective. Finally, isolate FPYF3053 were showed no effective inhibition of Phytophthora cinnamomi growth. In this study, we attempt to understand the VOCs inhibitory impacts from the endophytic Diaporthe strains without consideration of interaction between the strains and pathogenes. Future research is proposed to investigate the dual interaction in the VOCs’ levels and other molecules between fungal interactions [48].

Table 5.

Comparison VOCs’ inhibitive effect among Diaporthe strains.

The headspace analyses of the four Diaporthe strains in potato dextrose medium revealed that three monoterpenes—β-phellandrene, biphenylene,1,2,3,6,7,8,8a,8b-octahydro-4,5-dimethyl and α-muurolene—seemed to be characteristic compounds of endophytic Diaporthe strains endophytic to Catharathus roseus. However, among all monoterpenes mentioned above, only 1-menthone can be found in volatile compounds of Catharathus roseus flowers, the essential oil of which is high in limonene and other monoterpenes [45,46]. Menthol and β-phellandrene were also found in VOCs of Diaporthe strain PR4 with very low relative amounts of less than 1.0% [19]. No chemicals were shared in VOCs between our FPYF strains and Phomopsis strain EC-4 (Table 4, [18]). Therefore, the antifungal VOCs from the four endophytic Diaporthe Chinese strains possesses unique VOC compositions compared with known Diaporthe VOCs. Although many fungi were reported to produce many terpene compounds in their VOCs [49], our Diaporthe fungi maybe of some interest as a source of some other monoterpenes, which often only have been thought to originate from specific plants. For instance, essential oils from many plants containing more or less such monoterpenes as α-thujene, β-phellandrene [50,51,52], γ-terpinene [53,54], l-menthone [55,56], cyclohexanol, α-muurolene, thujone, and caryophyllene have some antifungal activities. For example, γ-terpinene, singly or in mixtures with sabinene in oil from coastal redwood leaves, has strong antifungal activity on some endophytic fungi [53]. Therefore, it could be rational to infer the terpenes in FPYF strains synergistically played a main role in their inhibition pathogenic fungi growths. In addition, the high content of monoterpenes in the Diaporthe VOCs does have potential for the biofuel industry [18,20,57].

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2309-608X/4/2/65/s1. Figure S1. MP phylogenetic tree of five-locus alignment for FPYF3053-3056 in genus Diaporthe with Diaporthella corylina as an outgroup; Figure S2. ML phylogenetic tree of five-locus alignment for FPYF3053-3056 in genus Diaporthe with Diaporthella corylina as an outgroup.

Author Contributions

D.-H.Y. conceived the grant and designed the experiments; D.-H.Y., and T.L. collected the plant samples and identified the plant; X.S. and H.L. performed the experiment; D.-H.Y. organized the manuscript; G.S. advised research and revised manuscript. And G.D. managed laboratory jobs for this work and processed the submission.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Fundamental Research Funds of CAF (CAFYBB2017MA010, to D.-H.Y.). We thank Han Xu (Research Institute of Tropical Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry) for kindly helping with host plant identification, and thank Kaiying Wang (Research Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment and Protection) for taking part in the work on sample collection and fungal isolation. The authors sincerely appreciate the three peer reviewers’ valued comments on the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kumar, G.; Chandra, P.; Choudhary, M. Endophytic fungi: A potential source of bioactive compounds. Chem. Sci. Rev. Lett. 2017, 6, 2373–2381. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Khanna, A.; Chauhan, A.; Chauhan, G.; Kaushik, P. In vitro evaluation of crude extracts of Catharanthus roseus for potential antibacterial activity. Int. J. Green Pharm. 2008, 2, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, S.; Govindaraji, V.; Kannan, K.N.; Jayakumararaj, R. In vitro evaluation of antibacterial activity using crude extracts of Catharanthus roseus L. (G.) Don. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2008, 12, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Kabesh, K.; Senthilkumar, P.; Ragunathan, R.; Kumar, R.R. Phytochemical analysis of Catharanthus roseus plant extract and its antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2015, 3, 162–172. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, P.J.; Ghosh, J.S. Antimicrobial activity of Catharanthus roseus—A detailed study. Br. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 1, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafy, M.; Matter, M.; Asker, M.; Rady, M. Production of indole alkaloids in hairy root cultures of Catharanthus roseus l. and their antimicrobial activity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016, 105, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakra, N.S.; Koul, M.; Chandra, R.; Chandra, S. Histological investigations of healthy tissues of Catharanthus roseus to localize fungal endophytes. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2013, 20, 205–209. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, S.S.; Singh, S.; Babu, C.S.V.; Shanker, K.; Srivastava, N.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Kalra, A. Fungal endophytes of Catharanthus roseus enhance vindoline content by modulating structural and regulatory genes related to terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, M.; Tang, Z.; Rao, L. Isolation and identification on endophytic fungus from Catharanthus roseus. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2008, 36, 12712–12713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpotu, M.O.; Eze, P.M.; Abba, C.C.; Umeokoli, B.O.; Nwachukwu, C.U.; Okoye, F.B.C.; Esimone, C.O. Antimicrobial activities of secondary metabolites of endophytic fungi isolated from Catharanthus roseus. J. Health Sci. 2017, 7, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.N.; Padmavathy, S. Impact of endophytic microorganisms on plants, environment and humans. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, P.J.C.D.; Savi, D.C.; Gomes, R.R.; Goulin, E.H.; Senkiv, C.D.C.; Tanaka, F.A.O.; Almeida, Á.M.R.; Galli-Terasawa, L.; Kava, V.; Glienke, C. Diaporthe endophytica and D. terebinthifolii from medicinal plants forbiological control of Phyllosticta citricarpa. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 186, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonial, F.; Maia, B.H.L.N.S.; Sobottka, A.M.; Savi, D.C.; Vicente, V.A.; Gomes, R.R.; Glienke, C. Biological activity of Diaporthe terebinthifolii extracts against Phyllosticta citricarpa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanapichatsakul, C.; Monggoot, S.; Gentekaki, E.; Pripdeevech, P. Antibacterial and antioxidant metabolites of Diaporthe spp. Isolated from flowers of Melodorum fruticosum. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 75, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakshith, D.; Santosh, P.; Satish, S. Isolation and characterization of antimicrobial metabolite producing endophytic Phomopsis sp. from Ficus pumila Linn. (Moraceae). Int. J. Chem. Anal. Sci. 2013, 4, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkirui, C.; Stadler, M. The genus Diaporthe: A rich source of diverse and bioactive metabolites. Mycol. Prog. 2017, 16, 477–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.A.; Dirkse, E.; Sears, J.; Markworth, C. Volatile antimicrobials from Muscodor albus, a novel endophytic fungus. Microbiology 2001, 147, 2943–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.K.; Strobel, G.A.; Knighton, B.; Geary, B.; Sears, J.; Ezra, D. An endophytic Phomopsis sp. possessing bioactivity and fuel potential with its volatile organic compounds. Microb. Ecol. 2011, 61, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadri, M.; Deshidi, R.; Shah, B.A.; Bindu, K.; Vishwakarma, R.A.; Riyaz-Ul-Hassan, S. An endophyte of Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex. Benth, producing menthol, phenylethyl alcohol and 3-hydroxypropionic acid, and other volatile organic compounds. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Strobel, G.; Yan, D.-H. The production of 1,8-cineole, a potential biofuel, from an endophytic strain of Annulohypoxylon sp. FPYF3050 when grown on agricultural residues. J. Sustain. Bioenergy Syst. 2017, 7, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.D.; Lee, S.B.; Taylor, J.W.; Innis, M.A.; Gelfand, D.H.; Sninsky, J.J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal rnagenes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. A Guide Methods Appl. 1990, 18, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.; Crous, P.; Correia, A.; Phillips, A. Morphological and molecular data reveal cryptic species in Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Fungal Divers. 2008, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, L.; Alves, A.; Alves, R. Evaluating multi-locus phylogenies for species boundaries determination in the genus Diaporthe. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, N.; Donaldson, G. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium arenonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 7, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayanga, D.; Castlebury, L.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Chukeatirote, E.; Hyde, K.D. Insights into the genus Diaporthe: Phylogenetic species delimitation in the D. eres species complex. Fungal Divers. 2014, 67, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. Mafft multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. Partitionfinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidya, G.; Lohman, D.; Meier, R. Sequencematrix: Concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 2011, 27, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. Mega6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöver, B.C.; Müller, K.F. Treegraph 2: Combining and visualizing evidence from different phylogenetic analyses. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayob, F.W.; Simarani, K. Endophytic filamentous fungi from a Catharanthus roseus: Identification and its hydrolytic enzymes. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momsia, P.; Momsia, T. Isolation, frequency distribution and diversity of novel fungal endophytes inhabiting leaves of Catharanthus roseus. Int. J. Life Sci. Biotechnol. Pharm. Res. 2013, 2, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kharwar, R.N.; Verma, V.C.; Strobel, G.; Ezra, D. The endophytic fungal complex of Catharanthus roseus (L.) g. Don. Curr. Sci. 2008, 95, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogaran, S.; Kannan, K.P.; Mathiyalagan, Y. Fungal endophytes from Phyllanthus acidus (L.) and Catharanthus roseus (L.). Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2017, 8, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K.; Muthumary, J. Taxol production from Pestalotiopsis sp an endophytic fungus isolated from Catharanthus roseus. J. Ecobiotechnol. 2009, 1, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Palem, P.P.C.; Kuriakose, G.C.; Jayabaskaran, C. An endophytic fungus, Talaromyces radicus, isolated from catharanthus roseus, produces vincristine and vinblastine, which induce apoptotic cell death. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayob, F.W.; Simarani, K.; Abidin, N.Z.; Mohamad, J. First report on a novel nigrospora sphaerica isolated from Catharanthus roseus plant with anticarcinogenic properties. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakotoniriana, E.F.; Chataigné, G.; Raoelison, G.; Rabemanantsoa, C.; Munaut, F.; El Jaziri, M.; Urveg-Ratsimamanga, S.; Marchand-Brynaert, J.; Corbisier, A.-M.; Declerck, S.; et al. Characterization of an endophytic whorl-forming Streptomyces from Catharanthus roseus stems producing polyene macrolide antibiotic. Can. J. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Rathod, V.; Singh1, A.K.; Haq, M.U.; Mathew, J.; Kulkarni, P. A study on extracellular synthesis of silver nanoparticles from endophytic fungi, isolated from ethanomedicinal plants Curcuma longa and Catharanthus roseus. Int. Lett. Nat. Sci. 2016, 57, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickoo, M.; Farooq, U.; Bhatt, N.; Dhiman, M.; Alam, A.; Khan, M.A.; Jaglan, S. Alterneriol: Secondary metabolites derived from endophytic fungi Alternaria spp. isolated from Catharanthus roseus. UJPAH 2015, 1, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Rao, L.; Peng, G.; Zhou, M.; Shi, G.; Liang, Y. Effects of endophytic fungus and its elicitors on cell status and alkaloid synthesis in cell suspension cultures of Catharanthus roseus. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 5, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar]

- Sunitha, V.H.; Devi, D.N.; Srinivas, C. Extracellular enzymatic activity of endophytic fungal strains isolated from medicinal plants. World J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 9, 01–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Banerjee, D. Broad spectrum antibacterial activity of granaticinic acid, isolated from Streptomyces thermoviolaceus NT1; an endophyte in Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 5, 006–011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pinho, P.G.; Goncalves, R.F.; Valent, P.; Pereira, D.M.; Seabra, R.M.; Andrade, P.B.; Sottomayor, M. Volatile composition of Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don using solid-phase microextraction and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2009, 49, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, S.; Saha, K.; Sultana, N.; Khan, M.; Nada, K.; Afroze, M. Comparative studies of volatile components of the essential oil of leaves and flowers of Catharanthus roseus growing in bangladesh by GC-MS analysis. Indian J. Pharm. Biol. Res. 2015, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bier, M.C.J.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Soccol, C.R. Biotransformation of limonene by an endophytic fungus using synthetic and orange residue-based media. Fungal Biol. 2017, 121, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertrand, S.; Schumpp, O.; Bohni, N.; Monod, M.; Gindro, K.; Wolfender, J.-L. De novo production of metabolites by fungal co-culture of Trichophyton rubrum and Bionectria ochroleuca. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickschat, J.S. Fungal volatiles—A survey from edible mushrooms to moulds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2017, 34, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzoli, S.; Božović, M.; Baldisserotto, A.; Sabatino, M.; Cesa, S.; Pepi, F.; Vicentini, C.B.; Manfredini, S.; Ragno, R. Essential oil extraction, chemical analysis and anti-candida activity of Foeniculum vulgare miller—New approaches. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Qiu, J. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil from Wedelia prostrata. EXCLI J. 2013, 12, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosge, B.; Turker, A.; Ipek, A.; Gurbuz, B.; Arslan, N. Chemical compositions and antibacterial activities of the essential oils from aerial parts and corollas of Origanum acutidens (Hand.-Mazz.) Ietswaart, an endemic species to turkey. Molecules 2009, 14, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-García, F.J.; Langenheim, J.H. Effects of sabinene and γ-terpinene from coastal redwood leaves acting singly or in mixtures on the growth of some of their fungus endophytes. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1991, 19, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.S.; Joshi, N.; Padalia, R.C.; Singh, V.R.; Goswami, P.; Verma, S.K.; Iqbal, H.; Chanda, D.; Verma, R.K.; Darokar, M.P.; et al. Chemical composition and antibacterial, antifungal, allelopathic and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of cassumunar-ginger. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachitha, P.; Krupashree, K.; Jayashree, G.; Gopalan, N.; Khanum, F. Growth inhibition and morphological alteration of Fusarium sporotrichioides by Mentha piperita essential oil. Pharmacogn. Res. 2017, 9, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, M.; Pourbaige, M.; Tabar, H.K.; Farhadi, N.; Hosseini, S.M.A. Composition and antifungal activity of peppermint (Mentha piperita) essential oil from Iran. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2013, 16, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G. The story of mycodiesel. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 19, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).