Abstract

Fungal biota represents important constituents of phyllosphere microorganisms. It is taxonomically highly diverse and influences plant physiology, metabolism and health. Members of the order Diaporthales are distributed worldwide and include devastating plant pathogens as well as endophytes and saprophytes. However, many phyllosphere Diaporthales species remain uncharacterized, with studies examining their diversity needed. Here, we report on the identification of several diaporthalean taxa samples collected from diseased leaves of Cinnamomum camphora (Lauraceae), Castanopsis fordii (Fagaceae) and Schima superba (Theaceae) in Fujian province, China. Based on morphological features coupled to multigene phylogenetic analyses of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, the large subunit of nuclear ribosomal RNA (LSU), the partial beta-tubulin (tub2), histone H3 (his3), DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit (rpb2), translation elongation factor 1-α (tef1) and calmodulin (cal) genes, three new species of Diaporthales are introduced, namely, Diaporthe wuyishanensis, Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis and Paratubakia schimae. This study contributes to our understanding on the biodiversity of diaporthalean fungi that are inhabitants of the phyllosphere of trees native to Asia.

1. Introduction

The various fungi that inhabit the outer surface and the inner microenvironment of plant leaves are referred to as phyllosphere fungi [1,2]. These fungi include saprophytes, pathogens, epiphytes and endophytes and can affect plant growth and/or help enhance resistances to biotic and abiotic stress [3,4]. There is significant diversity of phyllosphere fungi whose members span diverse phyla in the Fungal Kingdom, particularly within the Ascomycota and the Basidiomycota [5]. Although studies examining the diversity of fungi in different trophic levels remain limited, fungal diversity on leaves has been shown to be lower than in soil but higher than that found on flowers and fruits, with several studies focusing on entomopathogenic fungi reporting highest diversity in soil, followed by leaves, leaf litter and twigs [6,7]. However, knowledge concerning phyllosphere fungal diversity particularly within the Diaporthales remains limited.

The camphor and timber trees, Cinnamomum camphora (L.) J. Presl and Castanopsis fordii Hance, and the flowering plant, Schima superba Gardner & Champ., are widely distributed in south-eastern China, where they can be the dominant members of forest ecosystems [8,9,10]. They play important roles in stabilizing soil, reducing erosion and protecting water sources [11,12]. In addition, these trees have important economic values, with various parts of certain members of the genus Castanopsis and Cinnamomum frequently employed as part of traditional medicinal practices [11,13]. The crude extracts and chemical constituents derived from Castanopsis exhibit a wide range of biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial and other effects [11]. Cinnamic acid, eugenol and cinnamyl alcohol from Cinnamomum were the active components of cardiovascular protection [13]. The fungi that associate with Cinnamomum, Castanopsis and Schima plants play different roles, with information concerning fungal Diaporthales diversity lacking, especially from diseased leaves [14,15]. Here, we report on the isolation and characterization of new fungal species isolated from diseased leaves of Cinnamomum camphora, Castanopsis fordii and Schima superba in Fujian Province, China. Based on morphological and molecular phylogenetic analyses, we identify three new fungal species, namely Diaporthe wuyishanensis sp. nov. in Diaporthaceae, Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis sp. nov. in Gnomoniaceae, and Paratubakia schimae sp. nov. in Tubakiaceae. Detailed descriptions and illustrations of the three new species are given. To the best of our knowledge, our data include the first identification and description of Paratubakia, (P. schimae sp. nov.) in China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Sources, Isolation, Morphological Characterization and Selection

Fungal spot disease specimens found on leaves of Cinnamomum camphora, Castanopsis fordii and Schima superba were collected at Meihua Mountain National Nature Reserve, Longyan City and Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, Wuyishan City in Fujian Province, China. The two sampling sites are representative areas of large Cinnamomum, Castanopsis and Schima forests, with high plant diversity, abundant precipitation and more mountains. The leaf specimens were placed in paper bags, which were labeled with the details concerning plant hosts, locations, geographical features and altitudes [16]. Specimens were taken to laboratory and treated as described in Photita et al. [17]. The fungi were isolated using a tissue separation method as follows: ~25 mm2 diseased tissue fragments were cut from leaves displaying spot symptoms. The fragments were first sterilized by soaking in 75% ethanol for 60 s and then rinsed once with sterile deionized water for 20 s. Following this, samples were placed in 5% NaOCl for 30 s and then rinsed three times with sterile deionized water for 60 s each time. Finally, fragments were dried on sterilized filter paper and then placed onto potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates for fungal outgrowth [17]. Pure colonies were obtained after sequential passage via culturing of growing fungal colony edges on PDA. Plates were incubated in a light incubator (12:12) at 25 °C. Strains were presumptively identified following three steps: firstly, each strain was sequenced with ITS and tef1 phylogenetic markers. The BLASTn searches were used to determine the most closely related taxa in the GenBank database with the ITS sequences. Secondly, the family or genus level phylogenetic analysis was conducted using ITS-tef1 sequences. For Diaporthe, strains were assigned to Diaporthe different complexes and referred to Dissanayake et al. [18]. Thirdly, amplification of other different loci and phylogenetic analyses were conducted using different multi-locus datasets. Ultimately, herbarium materials were kept at the Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China (HMAS), and living cultures were maintained in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC). Colony features were imaged with digital camera (Canon EOS 6D MarkII, Tokyo, Japan) at 7 and 15 days after inoculation in indicated media. Microstructures were observed and photographed using a stereo microscope (Nikon SMZ745, Tokyo, Japan) and biological microscope (Ni-U, Tokyo, Japan) with a digital camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using differential interference contrast (DIC) [19]. Structural measurements were measured using Digimizer 5.4.4 software (https://www.digimizer.com).

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

Fungal DNA was directly extracted from growing mycelia on PDA after 5–7 days of growth using the Fungal DNA Mini Kit (OMEGA-D3390, Feiyang Biological Engineering Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) according to the product manual. Nucleotide sequences corresponding to seven genetic loci were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a Bio-Rad Thermocycler (Hercules, CA, USA). For Diaporthe, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region was amplified with primers ITS5 and ITS4, the calmodulin (cal) gene with primers CAL-228F and CAL-737R, the histone H3 (his3) gene with primers CYLH3F and H3-1b, the translation elongation factor 1-α (tef1) gene with primers EF1-728F and TEF1-986R and the beta-tubulin (tub2) gene with primers Bt2a and Bt2b as described [20,21,22,23]. The same primers were used for Gnomoniopsis, with the exception of amplification of the tef1 gene, which was performed using primers EF1-728F and EF-2 [20,21,23,24]. For Paratubakia, the ITS and tub2 sequences were amplified with the primers listed above, and in addition, the LSU gene was amplified with primers LROR and LR5, the DNA-directed RNA polymerase II subunit (rpb2) gene with primers fRPB2-5F and fRPB2-7cR and the tef1 gene with primers EF1-728F and EF-2 [20,21,23,24,25,26,27]. The PCR thermal cycle program, primer pairs and sequence are listed in Table 1. The PCR reaction mixture was 25 µL, containing 12.5 μL of 2 × Spark Taq PCR Master Mix (Without Dye) (Shandong Sparkjade Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Jinan, China), 1 μL of template DNA, 1 µL each 10 µM primer (Tsingke, Fuzhou, China) and 9.5 µL of sterile water. Qualified PCR products were checked on electrophoresed in 1% agarose gel (RM19009 and RM02852, ABclonal) and were sequenced by a commercial company (Fuzhou Sunya Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Fuzhou, China).

Table 1.

Target sequences, primer pairs and PCR programs used for application in this study.

2.3. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

New sequences generated from this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Reference sequences were downloaded from GenBank (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Sequences were aligned with MAFFT v.7 (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/, (accessed on 29 August 2024)) and corrected manually by MEGA 7 software [28,29]. The concatenated aligned sequences were analyzed by Maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods using the CIPRES Science Gateway portal (https://www.phylo.org/, accessed on (30 August 2024)) and Phylosuite software v. 1.2.3 [30,31]. The Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was performed with 1000 rapid bootstrap replicates using the GTRGAMMA substitution model by RaxML-HPC2 on ACCESS v. 8.2.12 [32,33]. For Bayesian inference (BI) analyses, Partition Finder2 was used to select the evolutionary model for each locus [34]. Four simultaneous Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were initiated from random trees with 1 million generations for the Diaporthe, 15 million generations for the Gnomoniopsis and 5 million generations for the Tubakiaceae analyses. In the tests, analyses were sampled every 100 generations. The first 25% of trees were discarded, and remaining trees were used to determine posterior probabilities (PPs). System diagrams were plotted using FigTree v. 1.4.5_pre (https://github.com/rambaut/figtree/releases (accessed on 3 September 2024)).

Table 2.

Information of specimens and GenBank accession numbers of the sequences used in the analysis of the Diaporthe virgiliae species complex.

Table 3.

Information of specimens and GenBank accession numbers of the sequences used in the analysis of Gnomoniopsis.

Table 4.

Information of specimens and GenBank accession numbers of the sequences used in the analysis of Tubakiaceae.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analyses

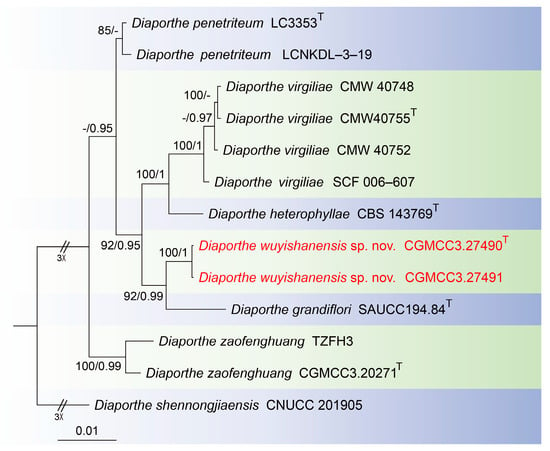

For the Diaporthe virgiliae species complex, the concatenated sequences dataset for the ITS, cal, his3, tef1 and tub2 genes were analyzed. The alignment included 13 taxa with Diaporthe shennongjiaensis as the outgroup (CNUCC 201905) (Figure 1). The sequence dataset contained 2653 characters (cal: 1–468, his3: 469–936, ITS: 937–1528, tef1: 1529–1865, tub2: 1866–2653) including gaps. Of these, 2418 characters were constant, 148 variable characters were parsimony-uninformative and 87 characters were parsimony informative. The SYM + I model was proposed for ITS, and the GTR model was proposed for tef1, and the HKY + I model was proposed for cal, his3 and tub2. The topology of Bayesian analyses was almost identical to the ML tree; thus, the Bayesian tree is shown.

Figure 1.

Consensus tree of Diaporthe virgiliae species complex inferred from Bayesian inference analyses based on the combined ITS, cal, his3, tef1 and tub2 sequence dataset, with Diaporthe shennongjiaensis (CNUCC 201905) as the outgroup. The Maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap support values and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPPs) above 80% and 0.90 are shown at the nodes. Strains marked with “T” are ex-type, ex-epitype and ex-neotype. The isolates from this study are indicated in red.

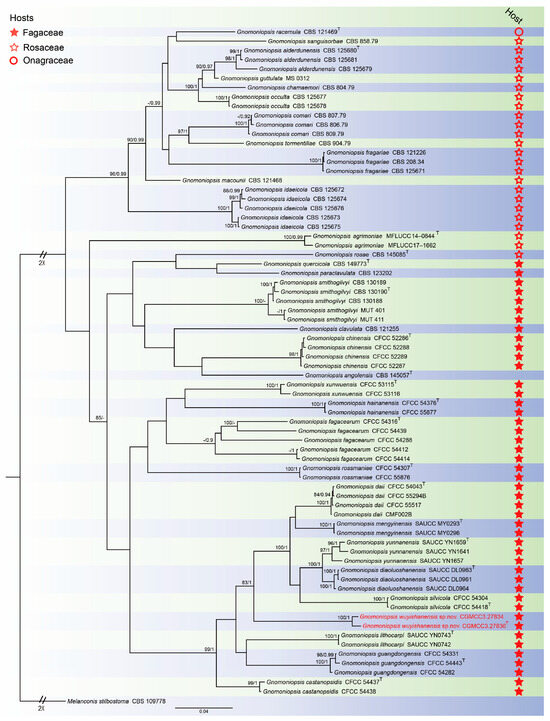

For Gnomoniopsis phylogenetic analyses, the concatenated sequence dataset combining the ITS, tef1 and tub2 gene loci was used. The alignment included 73 taxa with Melanconis stilbostoma as the outgroup (CBS 109778) (Figure 2). The sequence dataset contained 2584 characters (ITS: 1–564, tef1: 565–1710, tub2: 1711–2584) including gaps. Of these, 1462 characters were constant, 142 variable characters were parsimony-uninformative and 980 characters were parsimony informative. The GTR + I + G model was proposed for ITS, tef1 and tub2 analysis. The topology of the Bayesian analyses was almost identical to the ML tree; thus, the Bayesian tree is shown.

Figure 2.

Consensus tree of Gnomoniopsis inferred from Bayesian inference analyses based on the combined ITS, tef1 and tub2 sequence dataset, with Melanconis stilbostoma (CBS 109778) as the outgroup. The Maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap support values and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPPs) above 80% and 0.90 were shown at the nodes. Strains marked with “T” are ex-type, ex-epitype and ex-neotype. The isolates from this study are indicated in red.

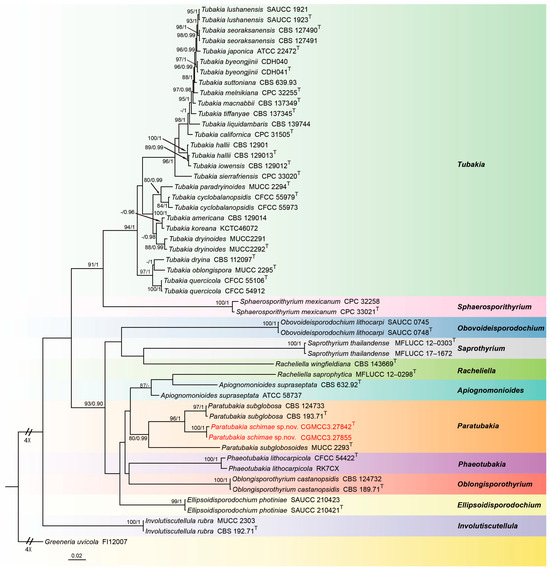

To infer the interspecific relationships between Paratubakia within Tubakiaceae, a dataset consisting of ITS, LSU, rpb2, tef1 and tub2 sequences was assembled and analyzed. The alignment included 52 taxa with Greeneria uvicola (FI12007) as the outgroup (Figure 3). The sequence dataset contained 3809 characters (ITS: 1–666, LSU: 667–1516, rpb2: 1517–2501, tef1: 2502–3217, tub2: 3218–3809) including gaps. Of these, 2473 characters were constant, 148 variable characters were parsimony-uninformative and 1188 characters were parsimony informative. The GTR + I + G model was proposed for ITS, LSU, rpb2 and tub2, and the HKY + I + G model was proposed for tef1 analyses. The topology of Bayesian analysis was almost identical to the ML tree; thus, the Bayesian tree is shown.

Figure 3.

Consensus tree of Tubakiaceae inferred from Bayesian inference analyses based on the combined ITS, LSU, rpb2, tef1 and tub2 sequence dataset, with Greeneria uvicola (FI12007) as the outgroup. The Maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap support values and Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPPs) above 80% and 0.90 were shown at the nodes. Strains marked with “T” are ex-type, ex-epitype and ex-neotype. The isolates from this study are indicated in red.

3.2. Taxonomy

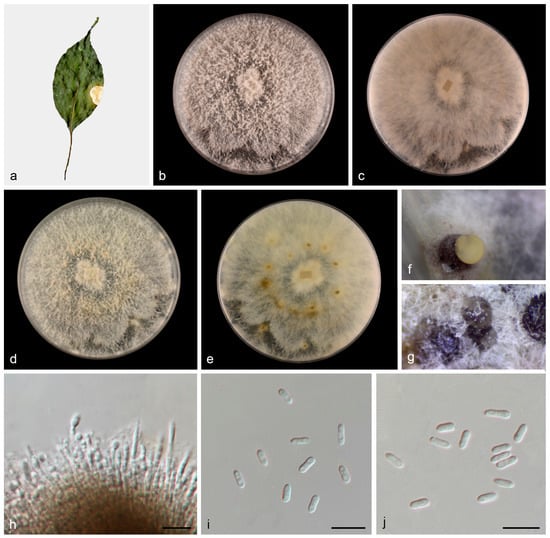

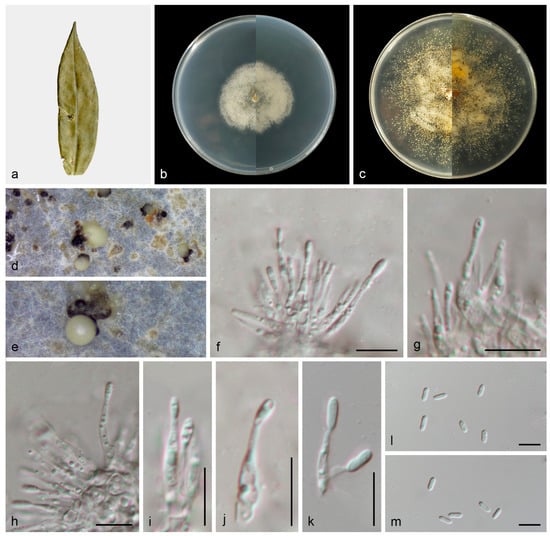

3.2.1. Diaporthe wuyishanensis W.B. Zhang and J.Z. Qiu, sp. nov., Figure 4

MycoBank Number: MB856022

Etymology: the epithet “wuyishanensis” refers to the locality, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve.

Holotype: China: Fujian Province, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, 27°38′37.88″ N, 117°55′52.39″ E, on diseased leaves of Cinnamomum camphora, 7 September 2022, T.C. Mu, holotype HMAS 352949, ex-holotype living culture CGMCC3.27490.

Figure 4.

Diaporthe wuyishanensis (HMAS 352949). (a) Diseased leaves of Cinnamomum camphora; (b,c) surface and reverse sides of colony after 7 days on PDA (d,e) and 14 days; (f,g) conidiomata; (h) conidiogenous cells and conidia; and (i,j) alpha conidia. Scale bars: (h–j) 10 µm.

Description: Asexual morphs: Conidiomata on PDA medium, coriaceous, pycnidial, solitaryor aggregated, superfical, dark brown to black, globose to subglobose, creamy yellowish conidial droplets exuded from ostioles. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, phialidic, densely aggregated, cylindrical or clavate, straight to slightly curved, 19.7–22.4 × 1.7–2.3 μm, n = 20. Conidia septate, hyaline, smooth, cylindrical or subcylindrical, cylindric-clavate, 4.3–6.5 × 1.4–2.6 μm, mean = 5.6 × 1.9 μm, L/W ratio = 3.0, n = 30. Beta conidia, gamma conidia and sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies on PDA were fluffy, and aerial mycelia were abundant, grayish in the center and white at the edge. The surface was initially white, then became pale yellow with age and reverse grayish yellow spots in the middle. Colonies on PDA covered 90 mm plates after 1 week at 25 °C, growth rate 11.8–12.5 mm/day.

Other materials examined: China: Fujian Province, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, 27°38′37.88″ N, 117°55′52.39″ E, on diseased leaves of Cinnamomum camphora, 7 September 2022, T.C. Mu, paratype HMAS 352950, ex-paratype living culture CGMCC3.27491.

Notes: In this study, multigene phylogenetic analysis showed that Diaporthe wuyishanensis (CGMCC3.27490 and CGMCC3.27491) formed an independent clade (92% ML/0.99 PP, Figure 1) with Diaporthe grandiflori [35]. However, Diaporthe wuyishanensis distinguished from Diaporthe grandiflori by ITS and tef1 loci comparison (32/552 in ITS and 19/317 in tef1). Morphologically, the alpha conidia of Diaporthe wuyishanensis are smaller than Diaporthe grandiflori (4.3–6.5 × 1.4–2.6 vs. 6.3–8.3 × 2.8–3.3 μm), and Diaporthe grandiflori produces alpha conidia and beta conidia, whereas Diaporthe wuyishanensis appears to only produce alpha conidia. Therefore, we introduce this fungus as a new species.

3.2.2. Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis T.C. Mu and J.Z. Qiu, sp. nov., Figure 5

MycoBank Number: MB856023

Etymology: The epithet “wuyishanensis” refers to the collection site of the holotype, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve.

Holotype: China: Fujian Province, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, 27°43′42.05″ N, 117°42′49.13″ E, on diseased leaves of Castanopsis fordii, 30 June 2023, T.C. Mu and Z.A. Heng, holotype HMAS 353149, ex-holotype living culture CGMCC3.27836.

Figure 5.

Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis (HMAS 353149). (a) Diseased leaves of Castanopsis fordii; (b) surface and reverse sides of colony after 7 days on PDA (c) and 14 days; (d,e) conidiomata; (f–k) conidiogenous cells and conidia; and (l,m) conidia. Scale bars: (f–m) 10 µm.

Description: Asexual morphs: Conidiomata developed on PDA, pycnidial, solitary, black, creamy conidial droplets exuded from ostioles. Conidiophores are indistinct, frequently reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells hyaline, smooth, phialidic, clavate, straight to sinuous, attenuate towards apex, 10.8–23.8 × 1.4–2.6 μm, n = 20. Conidia hyaline, smooth, aseptate, oblong to ellipsoid, subcylindrical, 5.1–8.7 × 1.4–3.0 μm, mean = 6.6 ×2.1 μm, L/W ratio = 3.2, n = 30. Sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies flat with irregular margin, white aerial mycelium then becoming pale gray by age. PDA attaining 36.0–40.7 mm in diameter after 1 week at 25 °C, growth rate 5.1–5.8 mm/day. PDA attaining 77.2–80.1 mm in diameter after 2 weeks at 25 °C, growth rate 5.5–5.7 mm/day.

Other materials examined: China: Fujian Province, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, 27°43′42.05″ N, 117°42′49.13″ E, on diseased leaves of Castanopsis fordii, 30 June 2023, T.C. Mu and Z.A. Heng, paratype HMAS 353148, ex-paratype living culture CGMCC3.27834.

Notes: Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis was isolated from diseased leaves of C. fordii from Fujian Province, China. Gnomoniopsis fagacearum (CFCC 54414) was collected from diseased leaves of Castanopsis eyrei from Fujian Province, China, by Jiang et al. [30]. Phylogenetically, Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis forms a well-supported (83% ML/1 PP, Figure 2) clade that is close, but distinct from Gnomoniopsis guangdongensis, Gnomoniopsis lithocarpi and Gnomoniopsis silvicola [30,36]. Morphologically, the conidia of Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis are larger than Gnomoniopsis guangdongensis, Gnomoniopsis lithocarpi and Gnomoniopsis silvicola (5.1–8.7 × 1.4–3.0 vs. 4.3–5.2 × 1.4–2.0 vs. 4.0–5.8 × 1.7–2.4 vs. 4.3–5.9 × 1.9–2.7 μm). Therefore, we introduce this taxon as a new species.

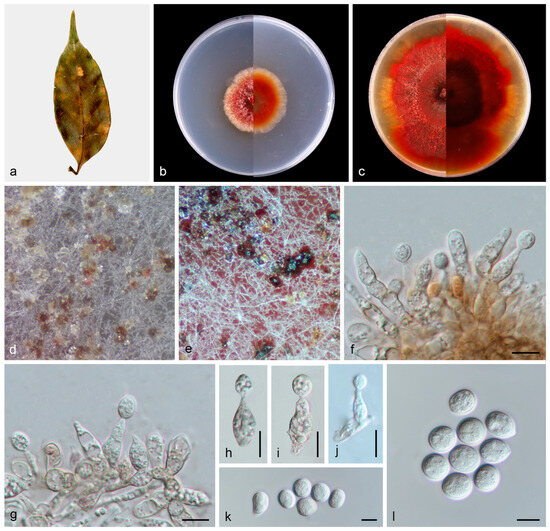

3.2.3. Paratubakia schimae T.C. Mu and J.Z. Qiu, sp. nov., Figure 6

MycoBank Number: MB856024

Etymology: The epithet “schimae” refers to the genus of the host plant on which it was collected, Schima.

Holotype: China: Fujian Province, Longyan City, Meihua Mountain National Nature Reserve, 25°39′20.91″ N, 116°55′32.01″ E, on diseased leaves of Schima superba, 14 September 2022, J.H. Chen and C.J. Yang, holotype HMAS 353150, ex-holotype living culture CGMCC3.27842.

Description: Asexual morphs: Conidiomata formed on the surface of PDA medium, pycnothyria grouped together, initially white and apricot, then became black with age. Conidiophores reduced to conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells, hyaline to pale brown, smooth, thin-walled, phialidic, obclavate, 13.0–20.5 × 4.4–5.8 μm, n = 20. Conidia hyaline to slightly pigmented, smooth, solitary, globose to subglobose, with inconspicuous to conspicuous hilum, 10.6–13.7 × 9.4–11.8 μm, mean = 12.1 × 10.5 μm, L/W ratio = 1.2, n = 30. Sexual morph not observed.

Culture characteristics: Colonies flat with regular margin, aerial mycelium white. This species can produce red pigment during growth, which causes the surface and reverse sides of PDA medium to change from colorless to red. PDA attaining 37.7–40.3 mm in diameter after 1 week at 25 °C, growth rate 5.4–5.8 mm/day. PDA attaining 78.7–85.6 mm in diameter after 2 weeks at 25 °C, growth rate 5.6–6.1 mm/day.

Other materials examined: China: Fujian Province, Longyan City, Meihua Mountain National Nature Reserve, 25°39′20.91″ N, 116°55′32.01″ E, on diseased leaves of Schima superba, 14 September 2022, J.H. Chen and C.J. Yang, paratype HMAS 353151, ex-paratype living culture CGMCC3.27855.

Notes: In this study, Paratubakia schimae form a well-supported (96% ML/1 PP, Figure 3) clade that is close to Paratubakia subglobosa within Tubakiaceae trees. However, Paratubakia schimae is distinguished from Paratubakia subglobosa by ITS, tef1, tub2 and rpb2 loci (24/519 in ITS, 38/569 in tef1, 19/498 in tub2 and 20/760 in rpb2) [37]. Morphologically, the conidiogenous cells of Paratubakia schimae are larger than Paratubakia subglobosa (13.0–20.5 × 4.4–5.8 vs. 8.0–12.0 × 2.0–3.0 μm). Therefore, we introduce this fungus as a new species.

Figure 6.

Paratubakia schimae (HMAS 353150). (a) Diseased leaves of Schima superba; (b) surface and reverse sides of colony after 7 days on PDA (c) and 14 days; (d,e) conidiomata; (f–j) conidiogenous cells and conidia; and (k,l) conidia. Scale bars: (f–l) 10 µm.

4. Discussion

Studies examining fungal diversity on leaves have led to the discovery of a variety of new species and taxa that include pathogens as well as potentially beneficial epi- and endophytes [38,39,40]. Diaporthales Nannf. (phylum Ascomycota) constitutes an important order of phyllosphere fungi [41,42]. Recent advances include the description of a new family, Pyrisporaceae C.M. Tian & N. Jiang, erected based on the type genus Pyrispora C.M. Tian & N. Jiang, with Pyrispora castaneae as the type species, which was collected from leaves of the Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima) [43]. Also, Obovoideisporodochium Z. X. Zhang, J. W. Xia & X. G. Zhang was established with the type species Obovoideisporodochium lithocarpi isolated from leaves of Lithocarpus fohaiensis [44]. In a survey of fungi associated with plant leaves in south-western China, eight new species of Diaporthe were identified from tea (Camellia sinensis): Castanea mollissima, Chrysalidocarpus lutescens, Elaeagnus conferta, Elaeagnus pungens, Heliconia metallica, Heterostemma grandiflorum, Litchi chinensis, Machilus pingii, Melastoma malabathricum and Millettia reticulate [35].

The genus Diaporthe Nitschke (syn. Phomopsis (Sacc.) Bubák) belongs to Diaporthaceae Höhn. ex Wehm. (Diaporthales), with Diaporthe eres as the type species [45,46]. Species of Diaporthe include both plant pathogens and endophytes, typically with broad host ranges, as well as saprophytes [47]. Currently, more 1200 epithets of Diaporthe and 983 of Phomopsis have been recorded in the Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org/; (accessed 10 September 2024)). Based on five single genetic loci, as well as multigene phylogentic analyses, the genus Diaporthe was re-structured with seven sections proposed: Betulicola, Crotalariae, Eres, Foeniculina, Psoraleae-pinnatae, Rudis and Sojae, with boundaries for 13 species and 15 species complexes [18]. The lengthy phylogenetic trees of the entire Diaporthe and data analysis were avoided, which provides mycologist and taxonomists with the convenience of focusing on specific sections, species complexes and species. Here, a new species, Diaporthe wuyishanensis, is introduced into the Diaporthe virgiliae species complex, based on both morphological differences and multi-locus (ITS, cal, his3, tef1 and tub2) molecular analyses. The Diaporthe virgiliae species complex contains five species, viz. Diaporthe grandiflori, Diaporthe heterophyllae, Diaporthe penetriteum, Diaporthe virgiliae and Diaporthe zaofenghuang, previously [18].

Gnomoniopsis Berl. is a genus in the Gnomoniaceae G. Winter (Diaporthales) with Gnomoniopsis chamaemori as the type species [48]. Gnomoniopsis was originally studied as a subgenus within Gnomonia Ces. & De Not. because of their similar morphology [49]. However, Gnomoniopsis has been separated from Gnomonia by means of morphology, phylogeny and host associations [36,48,49]. As important pathogens of agricultural and forestry trees, flowers and fruit, species of Gnomoniopsis can cause signficant plant damage and resultant economic losses [50,51,52,53]. It is reported that leaf spot diseases of oak (Quercus alba and Quercus rubra) have also been caused by Gnomoniopsis clavulata infection in North America [54], and Gnomoniopsis fragariae is reported to result in leaf blotch disease of strawberry in Europe [52]. Within the past 10–12 years, Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi has been isolated from diseased chestnut in Spain, Portugal and Greece, which are important chestnut-producing countries in Europe [55,56]. Gnomoniopsis castaneae infection damages the fruit of chestnuts and can cause cankers and necrosis on leaves. Cankers have also been reported on chestnut wood, red oak and hazelnut trees and are currently considered major threats to global chestnut production, potentially threatening the reintroduction of American chestnut, as the fungus has been found in North America [57].

With respect to host plants, Gnomoniopsis appears to mainly inhabit three plant families, viz. Rosaceae, Fagaceae and Onagraceae [49,58]. This is reflected in phylogram plant host analyses, in which Gnomoniopsis divides into three clades: Rosaceousclade, Fagaceousclade and Onagraceousclade, with most species currently assigned within the former two clades. Species of Gnomoniopsis have host-specific features in each clade, although the molecular basis for this specificity remains unknown. The new species we report, Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis, fits within the Fagaceous clade. These characterizations and placements allow for surveillance of potential outbreaks in relevant hosts.

The genus Paratubakia U. Braun & C. Nakash. belongs to Tubakiaceae U. Braun, J.Z. Groenew. & Crous (Diaporthales) with Paratubakia subglobosa as the type species [37]. Based on morphological and phylogenetic analyses, Phaeotubakia (type species: Phaeotubakia lithocarpicola) has more recently been proposed. Based on a multigene phylogeny (LSU and rpb2), Paratubakia subglobosa and Paratubakia subglobosoides have been shown to form an independent branch of Tubakiaceae. Currently, Paratubakia includes only two species: Paratubakia subglobosa and Paratubakia subglobosoides. Tubakiaceae has been proposed to accommodate the genera Apiognomonioides, Involutscutellula, Oblongisporothyrium, Paratubakia, Racheliella, Saprothyrium, Sphaerosporithyrium and Tubakia based on LSU sequence alignment and type genus Tubakia [37]. Subsequently, Obovoideisporodochium was established based on the type species Obovoideisporodochium lithocarpi [44], and Ellipsoidisporodochium was erected based on the type species Ellipsoidisporodochium photiniae [59]. Both Obovoideisporodochium lithocarpi and Phaeotubakia lithocarpicola and most Tubakiaceae species were found from Fagaceae plants [60]. Species of Paratubakia were only found and described from the Japanese blue oak (Quercus glauca) [37]. Here, we report on a new species Paratubakia schimae, with, to the best of our knowledge, the genus found and described in China for the first time. As this is the first description of Paratubakia in China, its distribution and potential host range remain unknown. However, our data suggest significant likelihood for additional discovery.

5. Conclusions

In this study, based on morphological features and multigene phylogenetic analyses, we described three new species of Diaporthales distributed within three different genera from China, viz. Diaporthe wuyishanensis, Gnomoniopsis wuyishanensis and Paratubakia schimae. These studies reveal a high diversity of phyllosphere fungi and help plant pathologists, taxonomists and phytologists to improve understanding of plant–fungal interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G., T.M. and J.Q.; methodology, J.S.; software, Y.M.; validation, J.Y., M.Z. (Mengjia Zhu) and L.Y.; formal analysis, H.P. and Y.L.; investigation, M.Z. (Minhai Zheng); resources, H.L. (Huajun Lv) and Z.H.; data curation, X.G., T.M., J.S., Y.M., J.Y., M.Z. (Minhai Zheng), L.Y., H.P., Y.L., Z.H., H.L. (Huiling Liang), L.F., X.M., H.M. and Z.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G. and T.M.; writing—review and editing, J.Q. and N.O.K.; visualization, Z.Q. and T.M.; supervision, X.G. and J.Q.; project administration, Z.Q. and J.Q.; funding acquisition, X.G. and J.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32270029, U1803232, 31670026), the National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2017YFE0122000), a Social Service Team Support Program Project (No. 11899170165), Science and Technology Innovation Special Fund (Nos. KFB23084, CXZX2019059S, CXZX2019060G) of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, a Fujian Provincial Major Science and Technology Project (No. 2022NZ029017), an Investigation and evaluation of biodiversity in the Jiulong River Basin (No. 082·23259-15), Macrofungal and microbial resource investigation project in Longqishan Nature Reserve (No. SMLH2024 (TP)-JL003#) and an Investigation of macrofungal diversity in Junzifeng National Nature Reserve, Fujian Province (No. Min QianyuSanming Recruitment 2024-23).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All sequences generated in this study were submitted to the NCBI database.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to Weibin Zhang, Jinhui Chen, Chenjie Yang and Sen Liu, who helped us with collecting samples, taking pictures and providing us with multigene sequence data of some new species.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Matthew, T.A.; Jonas, R.; Samuel, K.; Constanze, M.; Sang-Tae, K.; Detlef, W.; Eric, M.K. Microbial hub taxa link host and abiotic factors to plant microbiome variation. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002352. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Nomura, K.; Wang, X.; Sohrabi, R.; Xu, J.; Yao, L.; Paasch, B.C.; Ma, L.; Kremer, J.; Cheng, Y.; et al. A plant genetic network for preventing dysbiosis in the phyllosphere. Nature 2020, 580, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.E.; Mejia, L.C.; Kyllo, D.; Rojas, E.I.; Maynard, Z.; Robbins, N.; Herre, E.A. Fungal endophytes limit pathogen damage in a tropical tree. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15649–15654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannadan, S.; Rudgers, J.A. Endophyte symbiosis benefits a rare grass under low water availability. Funct. Ecol. 2008, 22, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlec, A. Novel techniques and findings in the study of plant microbiota: Search for plant probiotics. Plant Sci. 2012, 193–194, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, A.; Li Destri Nicosia, M.G.; Cacciola, S.O.; Droby, S.; Schena, L. Metabarcoding analysis of fungal diversity in the phyllosphere and carposphere of Olive (Olea europaea). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, R.A.; Masoudi, A.; Valdiviezo, M.J.; Keyhani, N.O. Discovery of Gibellula floridensis from infected spiders and analysis of the surrounding fungal entomopathogen community. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, C.; Zheng, S.; Hong, W.; Su, S.; Wu, C. Effects of forest gaps on some microclimate variables in Castanopsis kawakamii natural forest. J. Mt. Sci. 2012, 9, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, L.A.; Xu, M. The complete chloroplast genome of Cinnamomum camphora and its comparison with related Lauraceae species. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhang, L.; Cui, S.; Chen, F.; Xiong, Y.; Xie, P. Potential for forest vegetation carbon storage in Fujian Province, China, determined from forest inventories. Plant Soil 2011, 345, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Li, G.Q.; He, R.J.; Huang, Y.L. Genus Castanopsis: A review on phytochemistry and biological activities. Fitoterapia 2024, 179, 106216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Wan, J.; Liu, C.; Shi, X.; Xia, X.; Prakash, S.; Zhang, X. Retrogradation properties and in vitro digestibility of wild starch from Castanopsis sclerophylla. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 103, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Su, B.; Jiang, H.; Cui, N.; Yu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of the genus Cinnamomum (Lauraceae): A review. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Wang, X.W.; Liang, Y.M.; Tian, C.M. Lasiodiplodia cinnamomi sp. nov. from Cinnamomum camphora in China. Mycotaxon 2018, 133, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.C.; Tibpromma, S.; Dong, K.X.; Gao, C.X.; Zhang, C.S.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Elgorban, A.M.; Gui, H. Unveiling fungi associated with Castanopsis woody litter in Yunnan Province, China: Insights into Pleosporales (Dothideomycetes) Species. MycoKeys 2024, 108, 15–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, K.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, X.; Hu, H.; Wu, Q.; Liu, L.; Lin, Y.; Shen, X.; Kang, J.; et al. Stromatolinea, a new diatrypaceous fungal genus (Ascomycota, Sordariomycetes, Xylariales, Diatrypaceae) from China. MycoKeys 2024, 108, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Photita, W.; Taylor, P.W.J.; Ford, R.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S.L. Morphological and molecular characterization of Colletotrichum species from herbaceous plants in Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2005, 18, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, A.J.; Zhu, J.T.; Chen, Y.Y.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Liu, J.K. A re-evaluation of Diaporthe: Refining the boundaries of species and species complexes. Fungal Divers. 2024, 126, 1–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Xiong, C.; Gao, S.; Xu, W.; Zhao, L.; Song, C.; Liu, X.; James, T.Y.; Li, Z.; et al. ASF1 regulates asexual and sexual reproduction in Stemphylium eturmiunum by DJ-1 stimulation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Fungal Divers. 2023, 123, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, F.J.R.M.; Lee, S.H.; Taylor, L.; Shawe-Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal rna genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., Eds.; Academic Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Risède, J.M.; Simoneau, P.; Hywel-Jones, N.L. Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: Species with sphaeropedunculate vesicles. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 415–430. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kistler, H.C.; Cigelnik, E.; Ploetz, R.C. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing panama disease of banana: Concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2044–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Samuels, G.J. Taxonomy and phylogeny of Gliocladium analysed from nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 1994, 98, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic Relationships among Ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. Mafft online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Voglmayr, H.; Bian, D.R.; Piao, C.G.; Wang, S.K.; Li, Y. Morphology and phylogeny of Gnomoniopsis (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) from Fagaceae leaves in China. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, C.Y.; Gao, F.; Jakovlić, I.; Lei, H.P.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zou, H.; Wang, G.T.; Zhang, D. Using phylosuite for molecular phylogeny and tree-based analyses. iMeta 2023, 2, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandros, S. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. The CIPRES science gateway: Enabling high-impact science for phylogenetics researchers with limited resources. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference of the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment. Bridging from the Extreme to the Campus and Beyond, Chicago, IL, USA, 16 July 2012; Association for Computing Machinery: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. Partitionfinder2: New Methods for Selecting Partitioned Models of Evolution for Molecular and Morphological Phylogenetic Analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Huang, S.; Xia, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z. Morphological and molecular identification of Diaporthe species in south-western China, with description of eight new species. MycoKeys 2021, 77, 65–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, R.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal four new species of Gnomoniopsis (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) from China. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, U.; Nakashima, C.; Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Moreno-Rico, O.; Rooney-Latham, S.; Blomquist, C.L.; Haas, J.; Marmolejo, J. Phylogeny and taxonomy of the genus Tubakia s. lat. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2018, 1, 41–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibpromma, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Bhat, J.D.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.; Promputtha, I.; Doilom, M.; Yang, J.B.; Tang, A.M.C.; Karunarathna, S.C. Identification of endophytic fungi from leaves of Pandanaceae based on their morphotypes and DNA sequence data from southern Thailand. MycoKeys 2018, 33, 25–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, D.S.; Thambugala, K.M.; Jeewon, R.; Hongsanan, S.; Kuo, C.H.; Hyde, K.D. Additions to Chaetothyriaceae (Chaetothyriales): Longihyalospora gen. nov. and Ceramothyrium Longivolcaniforme, a new host record from decaying leaves of Ficus ampelas. MycoKeys 2019, 61, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, H.C.; Cai, L.T.; Li, W.; Pan, D.; Xiang, L.; Su, X.; Li, Z.; Adil, M.F.; Shamsi, I.H. Phyllospheric microbial composition and diversity of the tobacco leaves infected by Didymella segeticola. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 699699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, I.C.; Crous, P.W.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Jeewon, R.; Phillips, A.J.L.; Bhat, J.D.; Perera, R.H.; Li, Q.R.; Li, W.J.; et al. Families of Diaporthales based on morphological and phylogenetic evidence. Stud. Mycol. 2017, 86, 217–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.K.; Hyde, K.D.; Mapook, A.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Bhat, J.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Jeewon, R.; Wen, T.C. Taxonomic studies of some often over-looked Diaporthomycetidae and Sordariomycetidae. Fungal Divers. 2021, 111, 443–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Fan, X.; Tian, C. Identification and characterization of leaf-inhabiting fungi from Castanea plantations in China. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Mu, T.; Liu, S.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Xia, J. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal a new genus and two new species of Tubakiaceae from China. MycoKeys 2021, 84, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, A.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Liu, J.J. Unravelling Diaporthe species associated with woody hosts from karst formations (Guizhou) in China. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, A.; Lin, L.; Li, Y.; Fan, X. Diversity and pathogenicity of six Diaporthe species from Juglans Regia in China. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.R.; Glienke, C.; Videira, S.I.; Lombard, L.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Diaporthe: A genus of endophytic, saprobic and plant pathogenic fungi. Pers.-Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2013, 31, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.M.; Castlebury, L.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Sogonov, M.V.; White, J.F. Systematics of genus Gnomoniopsis (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales) based on a three gene phylogeny, host associations and morphology. Mycologia 2010, 102, 1479–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogonov, M.V.; Castlebury, L.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Mejía, L.C.; White, J.F. Leaf-inhabiting genera of the Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales. Stud. Mycol. 2008, 62, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Liang, L.Y.; Tian, C.M. Gnomoniopsis chinensis (Gnomoniaceae, Diaporthales), a new fungus causing canker of Chinese chestnut in Hebei Province, China. MycoKeys 2020, 67, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Tian, C. An emerging pathogen from rotted chestnut in China: Gnomoniopsis daii sp. nov. Forests 2019, 10, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayanga, D.; Miriyagalla, S.D.; Manamgoda, D.S.; Lewers, K.S.; Gardiennet, A.; Castlebury, L.A. Molecular reassessment of diaporthalean fungi associated with strawberry, including the leaf blight fungus, Paraphomopsis obscurans gen. et comb. nov. (Melanconiellaceae). IMA Fungus 2021, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Pu, M.; Cui, Y.; Gu, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C. Research on the isolation and identification of black spot disease of Rosa chinensis in Kunming, China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogonov, M.V.; Castlebury, L.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; White, J.F. The type species of Apiognomonia, A. veneta, with its Discula anamorph is distinct from A. errabunda. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguín, O.; Rial, C.; Piñón, P.; Sainz, M.J.; Mansilla, J.P.; Salinero, C. First report of Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi causing chestnut brown rot on nuts and burrs of sweet chestnut in Spain. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possamai, G.; Dallemole-Giaretta, R.; Gomes-Laranjo, J.; Sampaio, A.; Rodrigues, P. Chestnut brown rot and Gnomoniopsis smithogilvyi: Characterization of the causal agent in Portugal. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aglietti, C.; Cappelli, A.; Andreani, A. From chestnut tree (Castanea sativa) to flour and foods: A systematic review of the main criticalities and control strategies towards the relaunch of chestnut production chain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jiang, N.; Tian, C.M. Tree inhabiting gnomoniaceous species from China, with Cryphogonomonia gen. nov. Proposed. MycoKeys 2020, 69, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.B.; Zhang, Z.X.; Liu, R.Y.; Mu, T.C.; Zhang, X.G.; Li, Z.; Xia, J.W. Morphological and molecular identification of Ellipsoidisporodochium gen. nov. (Tubakiaceae, Diaporthales) in Hainan Province, China. Phytotaxa 2022, 552, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Xue, H.; Piao, C.G.; Li, Y. Phaeotubakia lithocarpicola gen. et sp. nov. (Tubakiaceae, Diaporthales) from leaf spots in China. MycoKeys 2023, 95, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).