Abstract

DES encodes the muscle-specific intermediate filament protein desmin, which is highly relevant to the structural integrity of cardiomyocytes. Mutations in this gene cause different cardiomyopathies including dilated cardiomyopathy. Here, we functionally validate DES-p.L112Q using SW-13, H9c2 cells, and cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells by confocal microscopy in combination with deconvolution analysis. These experiments reveal an aberrant cytoplasmic aggregation of mutant desmin. In conclusion, these functional analyses support the re-classification of DES-p.L112Q as a likely pathogenic variant leading to dilated cardiomyopathy.

1. Introduction

We have read with great interest the manuscript ‘Genetic Profiling and Phenotype Spectrum in a Chinese Cohort of Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Patients’ [1]. The authors have genetically characterized a cohort of 55 pediatric Chinese patients with dilated, hypertrophic, restrictive, and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy [1]. One patient with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) diagnosed at the age of 13 carried a heterozygous de novo variant DES-p.L112Q (c.335T>A) [1], which is localized in a conserved hotspot region within the 1A domain of desmin [2]. The DES gene (OMIM, *125660) encodes the muscle-specific intermediate filament protein desmin [3], which consists of a highly conserved rod domain flanked by non-helical head and tail domains [4]. The rod domain is sub-divided into coil-1A, -1B-, and -2. Desmin filaments connect different cellular substructures like the cardiac desmosomes, costameres, and Z-disc [5,6,7]. Therefore, desmin is highly relevant to the structural integrity of cardiomyocytes [8].

It is known, that several pathogenic desmin genetic variants localized in close proximity to DES-p.L112Q disturb filament assembly, leading to aberrant cytoplasmic desmin aggregates [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Since the authors have not reported any functional data about DES-p.L112Q, we address here whether desmin filament formation is affected by this novel rare variant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plasmid Generation

The pEYFP-N1-DES plasmid has been previously described [12]. The variant DES-p.L112Q was inserted into this expression plasmid using the Q5 Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) in combination with the two oligonucleotides 5′-GAAGGTGGAGCAGCAGGAGCTCAATG-3′ and 5′ TCGTTGGTGCGCGTGGTCAG-3′ (Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland). Plasmids were prepared using the GeneJET Miniprep Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and were verified by Sanger sequencing (Macrogen, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

2.2. Cell Culture and Transfection

SW-13 and H9c2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs, NP00040-8, UKKi011-A, https://ebisc.org/UKKi011-A/ accessed on 5 December 2025) were kindly provided by Dr. Tomo Šarić (University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany). The iPSCs were cultured in Essential 8 Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on vitronectin-coated cell culture plates. One day before transfection, the cells were transferred to µ-Slide 8-Well chambers (ibidi, Gräfelfing, Germany). Transfections were performed using Lipofectamin 3000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher).

2.3. Differentiation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells into Cardiomyocytes

iPSCs were differentiated into cardiomyocytes by modulation of the Wnt-pathway as previously described in detail [16]. For metabolic selection, iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes were selected with glucose-free RPMI 1640 Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 4 mM sodium-lactate for five days. iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes were cultured for maturation more than 100 days in cardio culture medium as previously described [16].

2.4. Fixation and Staining

Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Afterwards, the cells were fixated with 4% Histofix (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) at room temperature (RT) for 15 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X-100 (solved in PBS) for 15 min at RT. F-actin and the nuclei were stained in SW-13 and H9c2 cells using phalloidin conjugated to Texas-Red (1:400, 40 min, RT, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1 µg/mL, 5 min, RT). iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes were incubated overnight with monoclonal mouse anti-α-actinin-2 antibodies (1:200, A7732, Sigma Aldrich, Burlington, VT, USA) in combination with secondary polyclonal goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 568 (1:200, A11004, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.5. Confocal Microscopy

Confocal microscopy in combination with deconvolution analysis was performed as previously described in detail using a TCS SP8 system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) [17]. In brief, three-dimensional stacks were generated and shown as maximum intensity projections using the LAS X software (version 3.5.7.23335) (Leica Microsystems). Deconvolution analysis was performed using the Huygens Essential software (version 23.04.0) (Scientific Volume Imaging B.V., Hilversum, The Netherlands).

2.6. Molecular Desmin Model

Recently, the molecular structure of the highly homologous intermediate filament protein vimentin was published [18]. We used this structure to model the desmin anti-parallel tetramer structure using the SWISS-MODELL server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/ accessed on 10 July 2025) [19]. The tetrameric desmin structure was visualized using PyMOL Molecular Graphics Systems (version 3.1.6.1) (Schrödinger LLC, New York, NY, USA).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Cell transfections were performed in quadruplicate, and filaments or aggregates were manually counted in about one hundred cells. GraphPad Prism 10 software (version 10.6.1) (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA) was used for the generation of pie or bar charts. All data are shown as mean values ± standard deviation. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used for statistical analysis of aggregate and filament formation in transfected cells.

3. Results

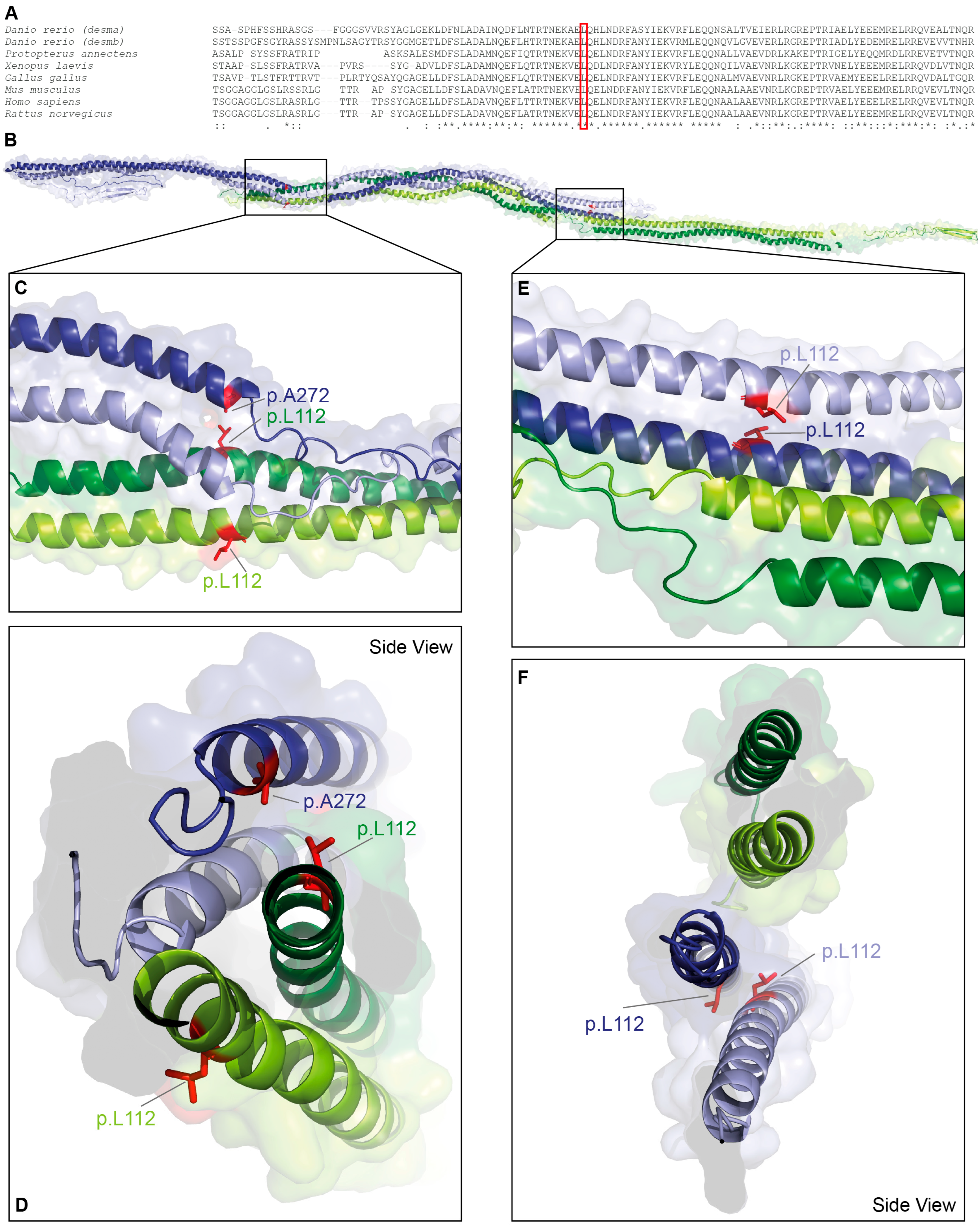

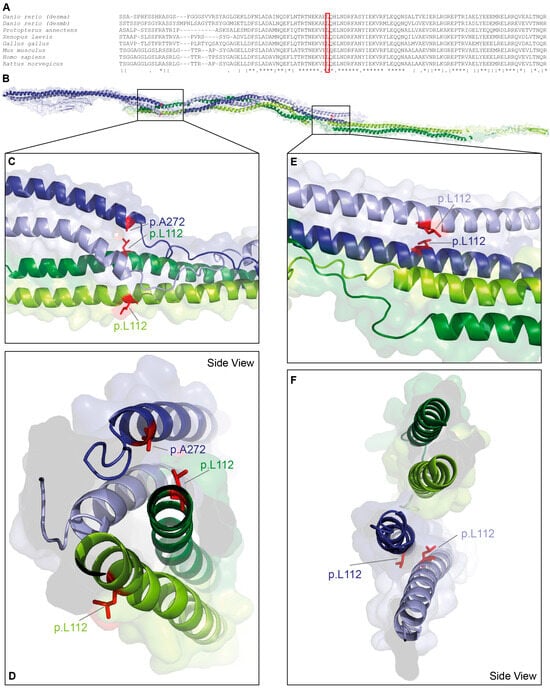

DES-p.L112Q is localized in a highly conserved stretch at the N-terminus of the 1A domain (Figure 1A). Leucine 112 is a hydrophobic amino acid contributing to the coiled-coil formation between the α-helices of the parallel dimer (Figure 1B–D). Additionally, it mediates presumably hydrophobic interactions with alanine 272 of the antiparallel dimer (Figure 1E,F). Within the antiparallel desmin tetramer, the two constituent dimers are not structurally equivalent. One dimer displays its C-terminal tail domains in a relatively extended, linear orientation, whereas in the opposing dimer, the tail domains appear partially folded back toward the rod domains.

Figure 1.

Structural analysis of DES-p.L112Q. (A) Partial desmin sequence alignments of different vertebrate species. Leucine 112 is highly conserved (highlighted by a red box). (B–F) Molecular model of the desmin tetramer. The backbone is shown in green, and the leucine 112 residues are shown in red. In addition, alanine 272 is labelled in blue.

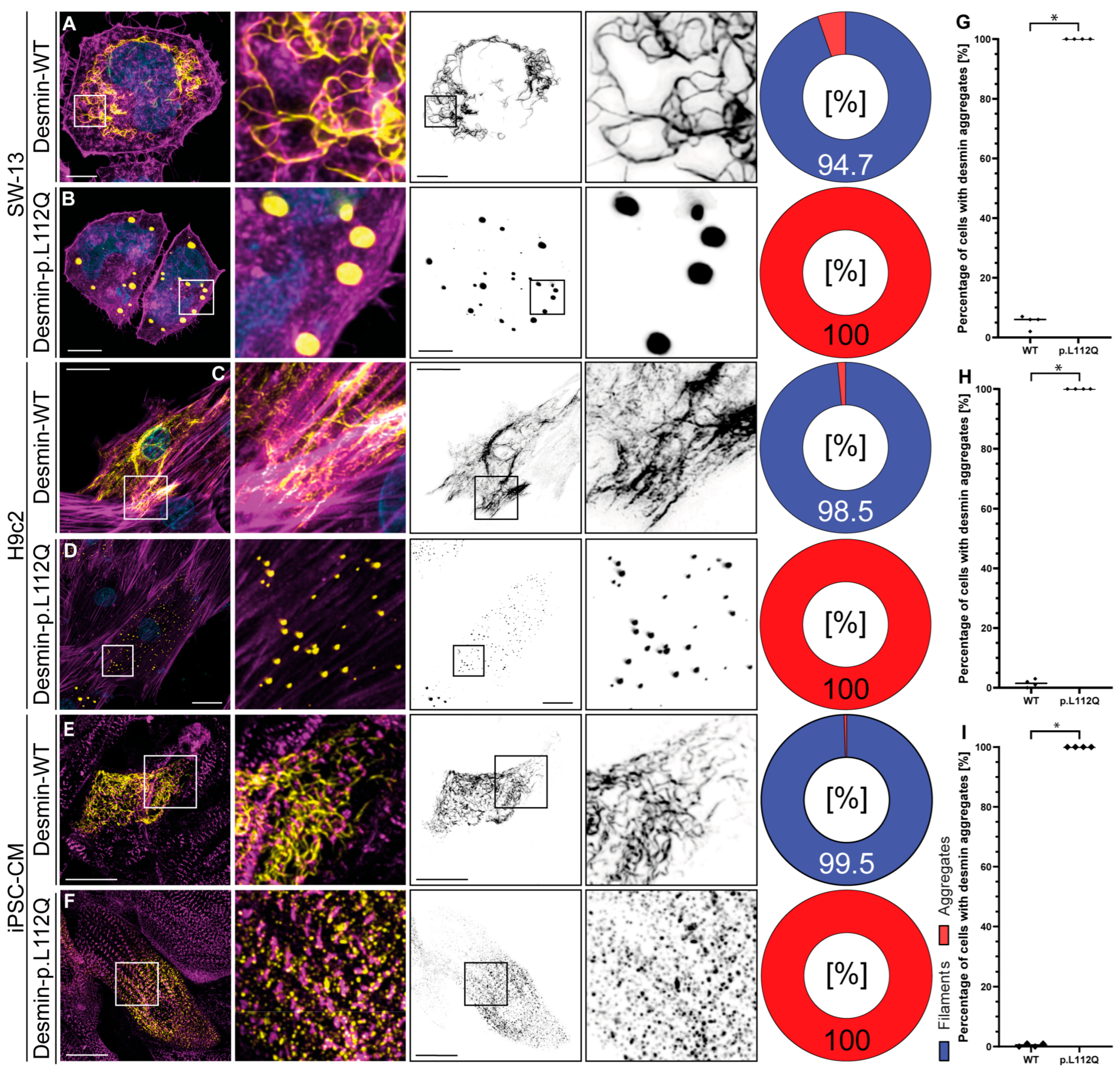

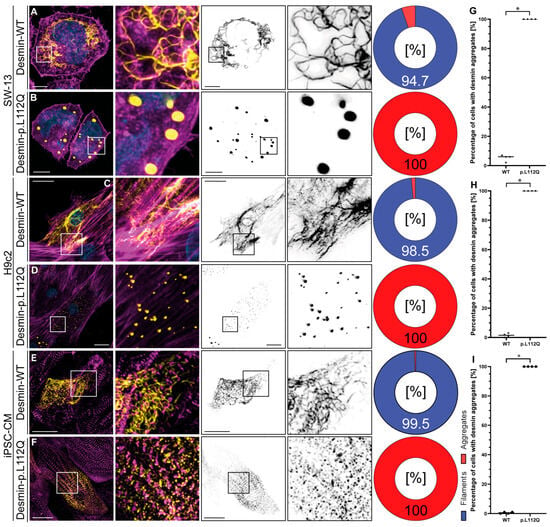

Confocal microscopy in combination with deconvolution analysis revealed, independently of the cell type used, a filament assembly defect in desmin-p.L112Q. We used SW-13 cells, since this cell line does not express endogenous desmin or any other cytoplasmic intermediate filament proteins [20]. H9c2 and iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes express, in contrast, endogenous desmin [21,22]. Desmin-p.L112Q aggregates within the cytoplasm (Figure 2), indicating that the hydrophobic interactions within the dimer and tetramer structure of desmin may be disturbed by introducing a polar glutamine residue at position 112. In contrast, wild-type desmin forms filamentous structures of different sizes and shapes in most transfected cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cellular analysis of DES-p.L112Q. Representative cell images of SW-13 (A,B), H9c2 cells (C,D), and cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (E,F) are shown. Desmin is shown in yellow or black, F-actin or α-actinin-2 is shown in magenta, and the nuclei are shown in cyan. Scale bars represent 10 µm (SW-13) or 20 µm (H9c2 and iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes). (G–I) Quantification of the percentage of filament and aggregate-forming cells are shown as pie and bar charts (mean values ± standard deviation). In total, four independent cell transfection experiments (n = 4) were performed, and about 100 transfected cells were analyzed per transfection experiment. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used for statistical analysis (* p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Recently, Xing et al. identified the heterozygous de novo variant DES-p.L112Q in a pediatric patient with DCM [1]. The authors classified this novel desmin variant according to the guidelines of the American College of Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [23] as a variant of unknown significance (VUS) fulfilling the PM6, PM2, and PP3 criteria [1]. At the same amino acid position, a different likely pathogenic variant (p.L112R) causes aberrant cytoplasmic desmin aggregation [2]. Comparably, our functional analysis showed a detrimental defect of desmin-p.L112Q similar to desmin-p.L112R. Desmin-p.L112Q forms aberrant cytoplasmic aggregates, indicating an intrinsic desmin filament assembly defect. Recently, we validated the filament assembly assay according the detailed guidelines of the ACMG [24] including twelve different positive and negative controls [17]. Therefore, functional studies indicate an additional strong criterion for the pathogenicity of DES-p.L112Q and may be helpful in the classification of genetic variants.

5. Limitations

In the future, it may be valuable to characterize further patho-mechanisms using patient-specific iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from individuals diagnosed with DCM carrying DES variants.

6. Conclusions

Here, we report that desmin-p.L112Q causes a filament assembly defect similar to other pathogenic DES variants. Therefore, our functional data complement the data of Xing et al. [1] and support the re-classification of DES-p.L112Q as a likely pathogenic variant rather than a VUS. These findings may be relevant for clinical and genetic counselling of further patients carrying similar DES variants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.L., S.V. and J.R.; formal analysis, A.L. and A.B.; investigation, A.L., S.V., J.G. (Joline Groß), A.G. and A.B.; data curation, A.L., S.V. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.L., S.V., J.R., J.G. (Joline Groß), A.G., J.G. (Jan Gummert), H.M. and A.B.; visualization, A.L., S.V. and A.B.; supervision, A.B.; resources J.G. (Jan Gummert); project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, H.M. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was kindly funded by the Medical Faculty of the Ruhr-University Bochum (FoRUM, F1074-2023 and F1099-24) and by the ‘Deutsche Herzstiftung e. V.’ (Frankfurt a. M., Germany). In addition, we are thankful to the Erich and Hanna Klessmann Foundation (Gütersloh, Germany) for financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article. The plasmids described are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

A.B. is a shareholder in Tenaya Therapeutics, Prime Medicine, and Merck. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Abbreviations

| ACMG | American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| DCM | Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| iPSCs | Induced pluripotent stem cells |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| RT | Room temperature |

| VUS | Variant of Unknown Significance |

References

- Xing, G.; Chen, L.; Lv, L.; Xu, G.; Duan, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Q. Genetic Profiling and Phenotype Spectrum in a Chinese Cohort of Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Patients. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Holler, S.; Gummert, J.; Milting, H. The N-Terminal Part of the 1A Domain of Desmin Is a Hot Spot Region for Putative Pathogenic DES Mutations Affecting Filament Assembly. Cells 2022, 11, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.L.; Lilienbaum, A.; Butler-Browne, G.; Paulin, D. Human desmin-coding gene: Complete nucleotide sequence, characterization and regulation of expression during myogenesis and development. Gene 1989, 78, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H.; Aebi, U. Intermediate Filaments: Structure and Assembly. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a018242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalakas, M.C.; Park, K.Y.; Semino-Mora, C.; Lee, H.S.; Sivakumar, K.; Goldfarb, L.G. Desmin myopathy, a skeletal myopathy with cardiomyopathy caused by mutations in the desmin gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Gaertner-Rommel, A.; Milting, H. Molecular insights into cardiomyopathies associated with desmin (DES) mutations. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 983–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartenbeck, J.; Franke, W.W.; Moser, J.G.; Stoffels, U. Specific attachment of desmin filaments to desmosomal plaques in cardiac myocytes. EMBO J. 1983, 2, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, L.G.; Dalakas, M.C. Tragedy in a heartbeat: Malfunctioning desmin causes skeletal and cardiac muscle disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1806–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klauke, B.; Kossmann, S.; Gaertner, A.; Brand, K.; Stork, I.; Brodehl, A.; Dieding, M.; Walhorn, V.; Anselmetti, D.; Gerdes, D.; et al. De novo desmin-mutation N116S is associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 4595–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernengo, L.; Chourbagi, O.; Panuncio, A.; Lilienbaum, A.; Batonnet-Pichon, S.; Bruston, F.; Rodrigues-Lima, F.; Mesa, R.; Pizzarossa, C.; Demay, L.; et al. Desmin myopathy with severe cardiomyopathy in a Uruguayan family due to a codon deletion in a new location within the desmin 1A rod domain. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2010, 20, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Voß, S.; Milting, H. Desmin-p. Y122S affects the filament formation and causes aberrant cytoplasmic desmin aggregation. Hum. Gene 2024, 41, 201299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Hedde, P.N.; Dieding, M.; Fatima, A.; Walhorn, V.; Gayda, S.; Saric, T.; Klauke, B.; Gummert, J.; Anselmetti, D.; et al. Dual color photoactivation localization microscopy of cardiomyopathy-associated desmin mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 16047–16057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodehl, A.; Dieding, M.; Klauke, B.; Dec, E.; Madaan, S.; Huang, T.; Gargus, J.; Fatima, A.; Saric, T.; Cakar, H.; et al. The novel desmin mutant p.A120D impairs filament formation, prevents intercalated disk localization, and causes sudden cardiac death. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2013, 6, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protonotarios, A.; Brodehl, A.; Asimaki, A.; Jager, J.; Quinn, E.; Stanasiuk, C.; Ratnavadivel, S.; Futema, M.; Akhtar, M.M.; Gossios, T.D.; et al. The Novel Desmin Variant p.Leu115Ile Is Associated with a Unique Form of Biventricular Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahim, M.A.; Ali, N.M.; Albash, B.Y.; Al Sayegh, A.H.; Ahmad, N.B.; Voss, S.; Klag, F.; Gross, J.; Holler, S.; Walhorn, V.; et al. Phenotypic Diversity Caused by the DES Missense Mutation p.R127P (c.380G>C) Contributing to Significant Cardiac Mortality and Morbidity Associated with a Desmin Filament Assembly Defect. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2025, 18, e004896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Zhang, J.; Azarin, S.M.; Zhu, K.; Hazeltine, L.B.; Bao, X.; Hsiao, C.; Kamp, T.J.; Palecek, S.P. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, S.; Milting, H.; Klag, F.; Semisch, M.; Holler, S.; Reckmann, J.; Goz, M.; Anselmetti, D.; Gummert, J.; Deutsch, M.A.; et al. Atlas of Cardiomyopathy Associated DES (Desmin) Mutations: Functional Insights Into the Critical 1B Domain. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2025, 18, e005358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eibauer, M.; Weber, M.S.; Kronenberg-Tenga, R.; Beales, C.T.; Boujemaa-Paterski, R.; Turgay, Y.; Sivagurunathan, S.; Kraxner, J.; Koster, S.; Goldman, R.D.; et al. Vimentin filaments integrate low-complexity domains in a complex helical structure. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2024, 31, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, K.K.; Chen, L.B. Absence of intermediate filaments in a human adrenal cortex carcinoma-derived cell line. Exp. Cell Res. 1986, 163, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hescheler, J.; Meyer, R.; Plant, S.; Krautwurst, D.; Rosenthal, W.; Schultz, G. Morphological, biochemical, and electrophysiological characterization of a clonal cell (H9c2) line from rat heart. Circ. Res. 1991, 69, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovhannisyan, Y.; Li, Z.; Callon, D.; Suspene, R.; Batoumeni, V.; Canette, A.; Blanc, J.; Hocini, H.; Lefebvre, C.; El-Jahrani, N.; et al. Critical contribution of mitochondria in the development of cardiomyopathy linked to desmin mutation. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brnich, S.E.; Abou Tayoun, A.N.; Couch, F.J.; Cutting, G.R.; Greenblatt, M.S.; Heinen, C.D.; Kanavy, D.M.; Luo, X.; McNulty, S.M.; Starita, L.M.; et al. Recommendations for application of the functional evidence PS3/BS3 criterion using the ACMG/AMP sequence variant interpretation framework. Genome Med. 2019, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.