Vericiguat Therapy Is Associated with Reverse Myocardial Remodeling in Chronic Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Patient Population

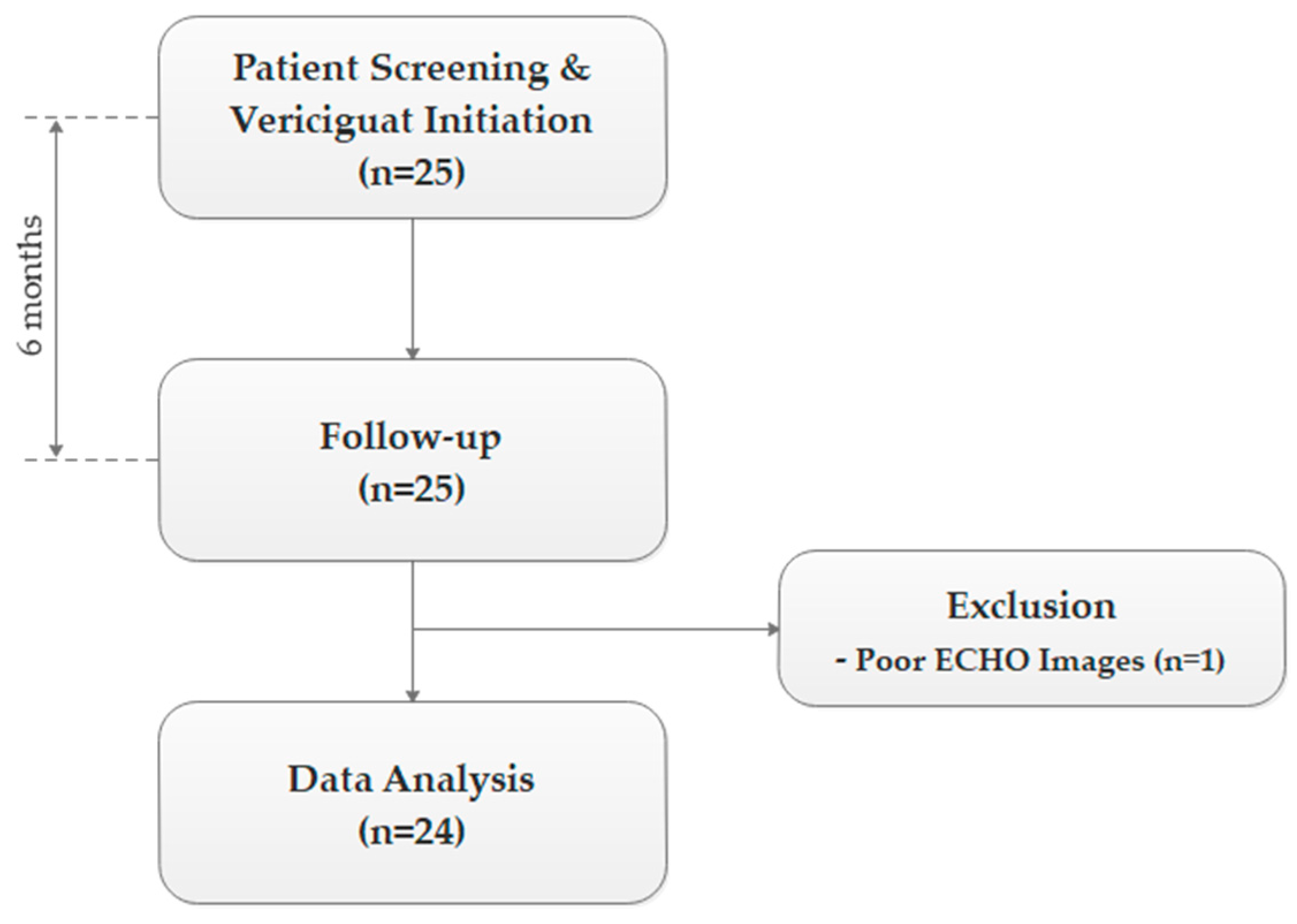

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Biochemical Evaluation

2.4. Echocardiographic Imaging

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Data

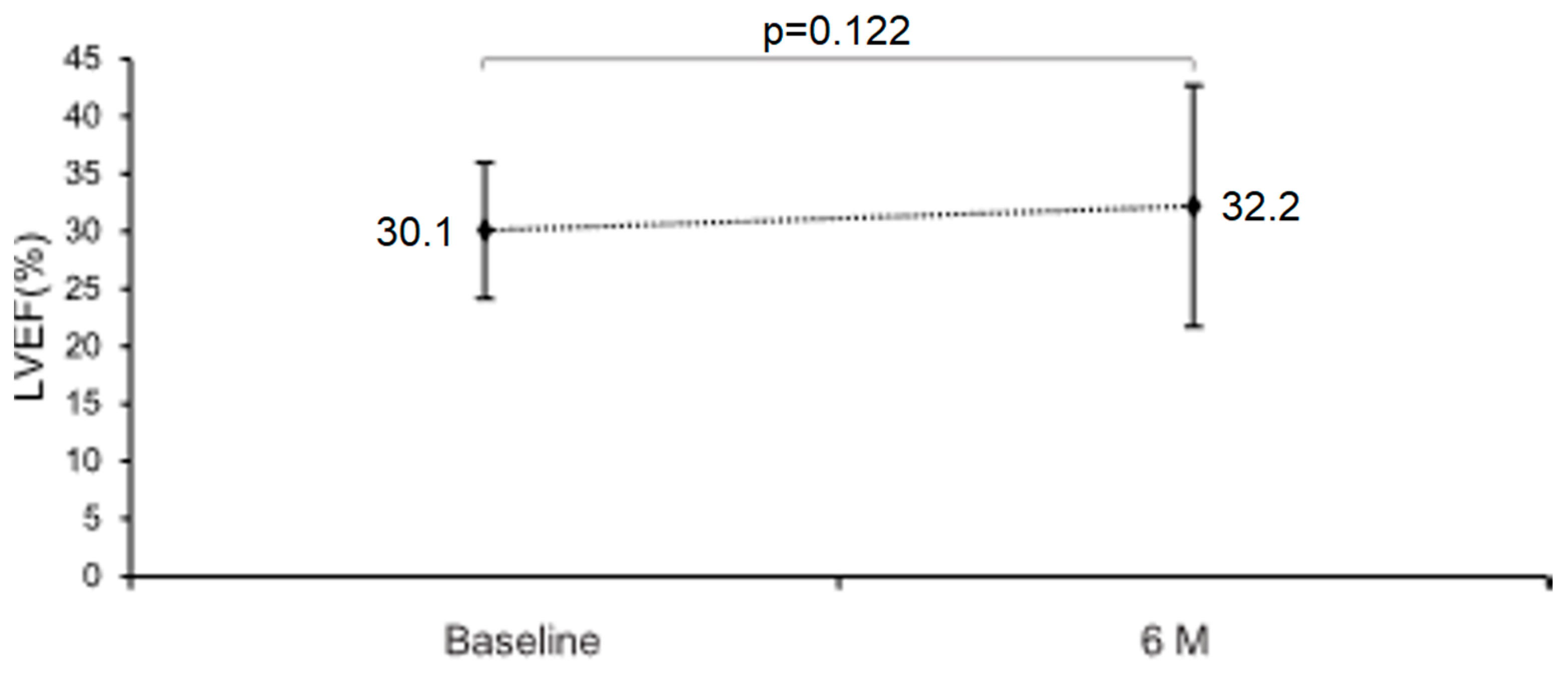

3.2. Primary Outcome

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

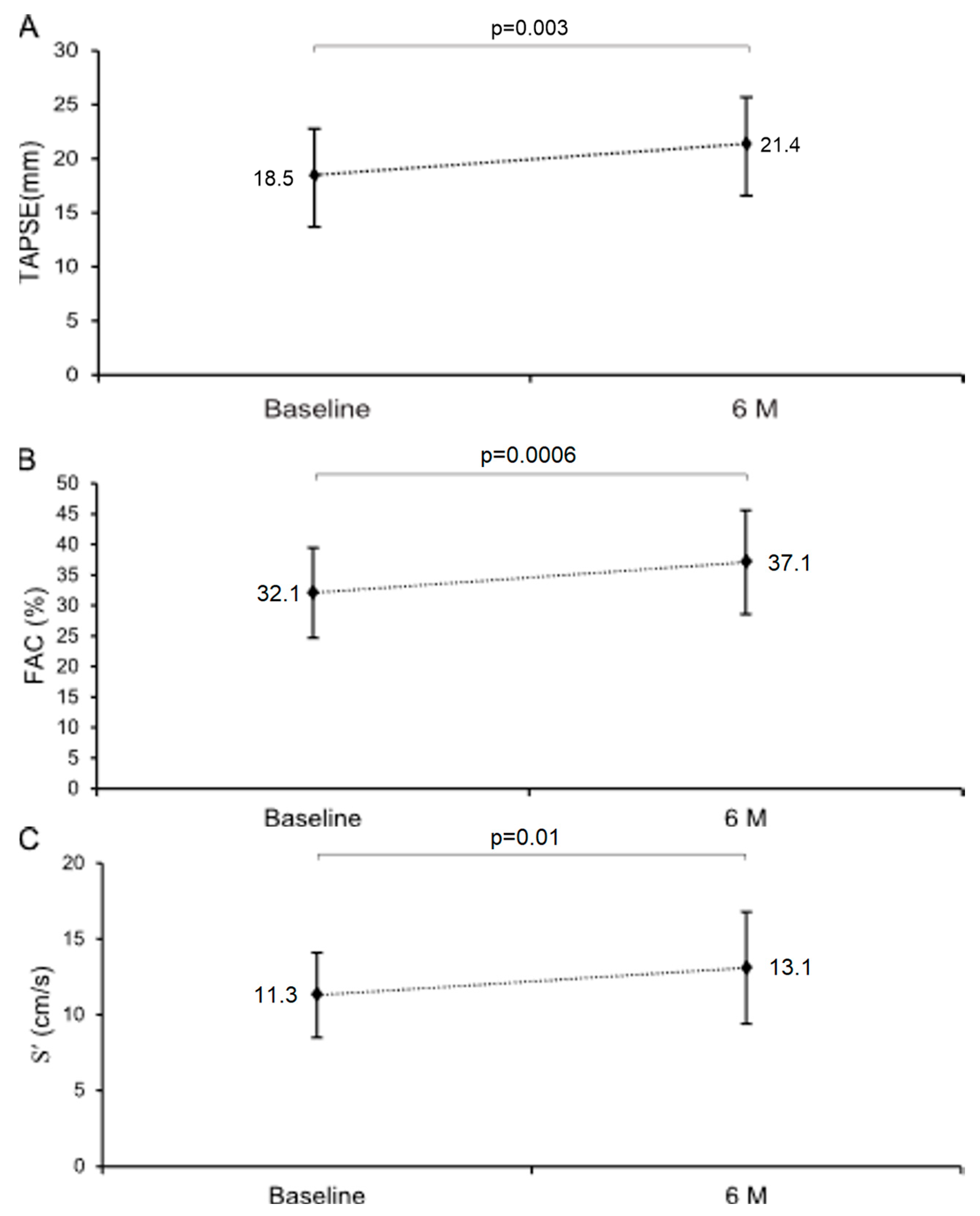

3.3.1. Myocardial Function

3.3.2. Myocardial Structure

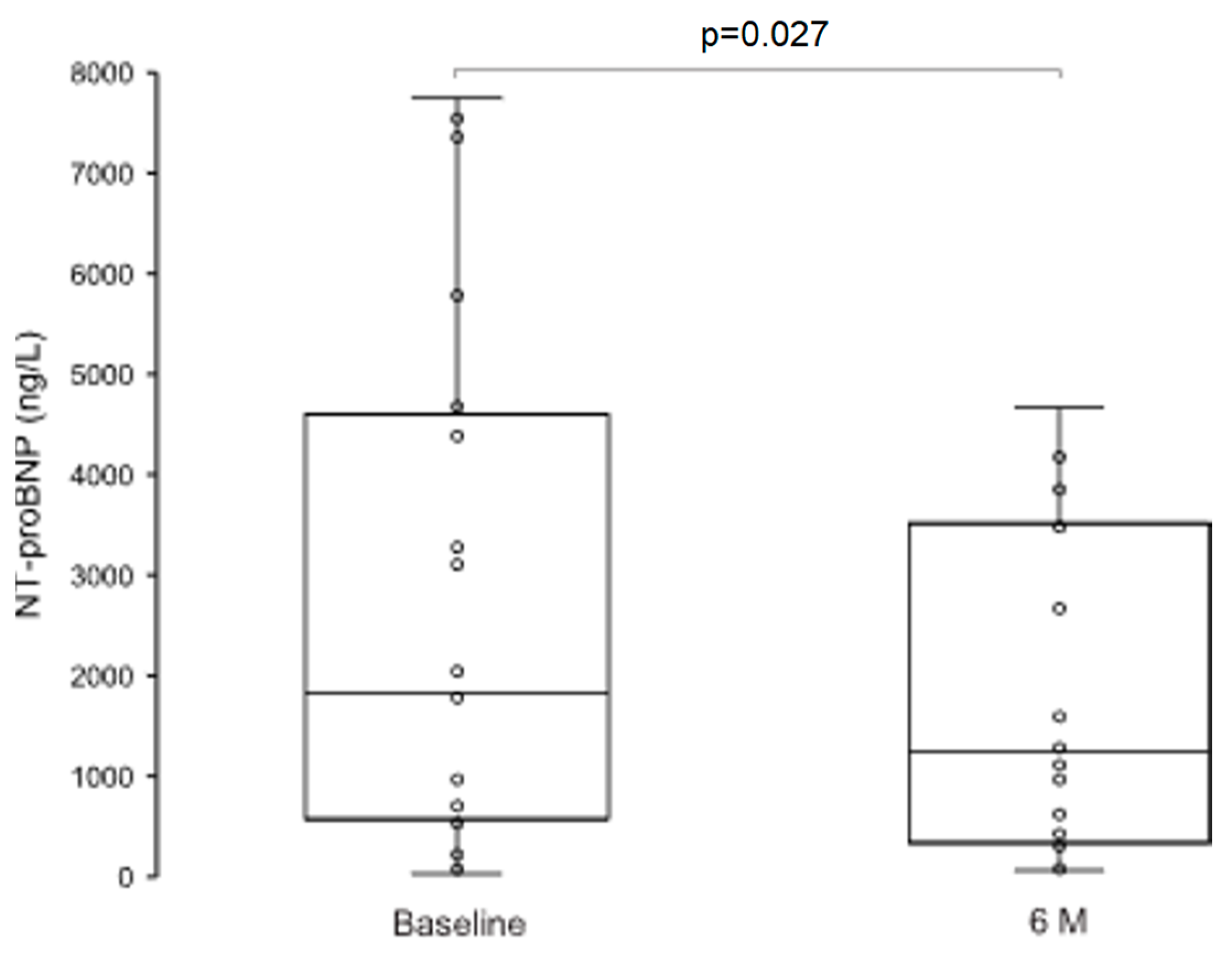

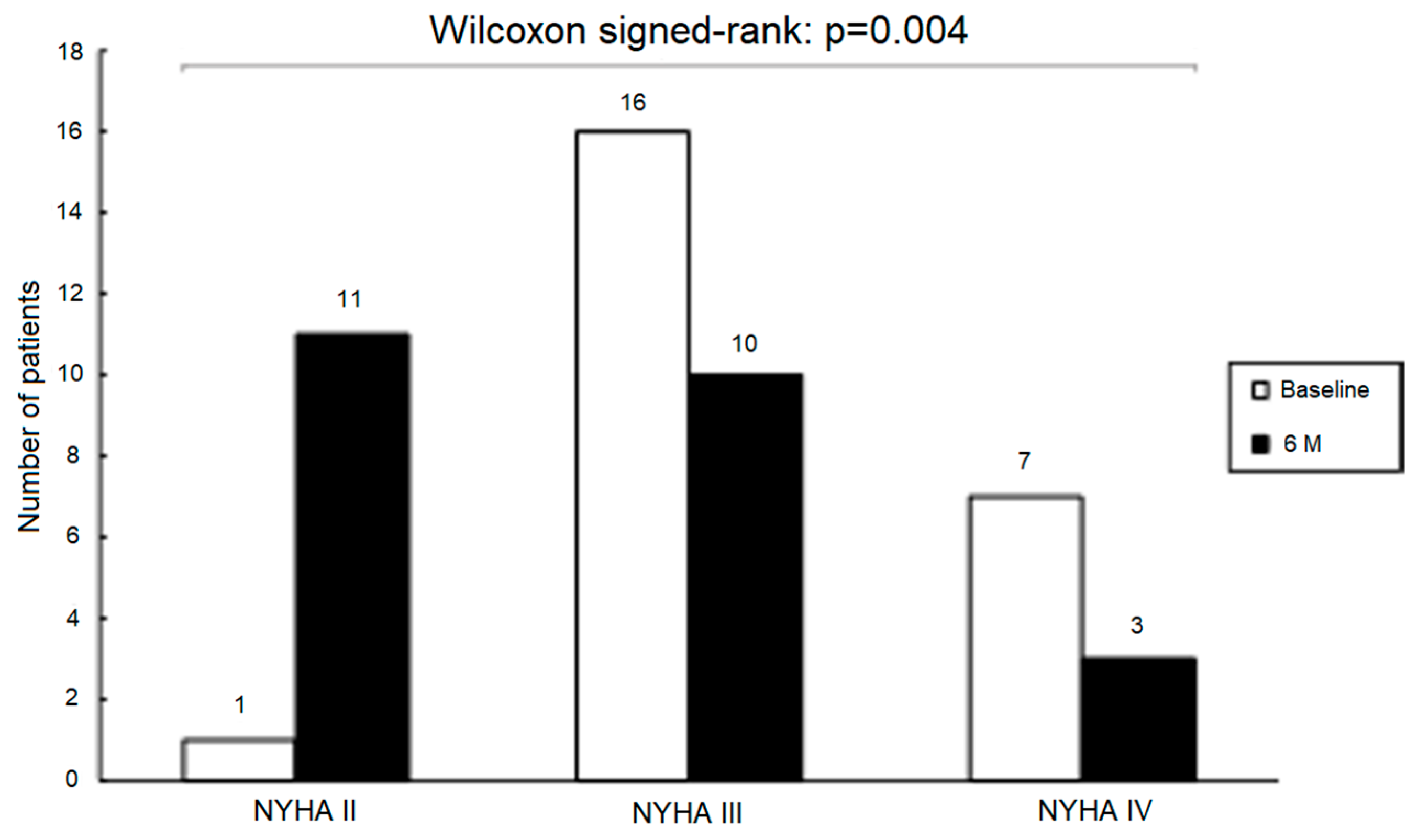

3.3.3. Neurohumoral Activation and NYHA Functional Class

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A2C | apical 2-chamber view |

| A4C | apical 4-chamber view |

| ACEi | angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor(s) |

| ARB | angiotensin receptor blocker(s) |

| ARNI | angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor |

| BB | beta-blockers |

| cGMP | cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| E/e′ | ratio of early mitral inflow velocity to mitral annular early diastolic velocity |

| FAC | fractional area change |

| GDMT | guideline-directed medical therapy |

| HFrEF | heart failure with reduced ejection fraction |

| LVAD | left ventricular assist device |

| LVEDV | left ventricular end-diastolic volume |

| LVEDD | left ventricular end-diastolic dimension |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| LVESD | left ventricular end-systolic dimension |

| LVESV | left ventricular end-systolic volume |

| LVOT VTI | left ventricular outflow tract velocity-time integral |

| MRA | mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist(s) |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| PLAX | parasternal long-axis |

| PSAX | parasternal short-axis |

| RVIDd | right ventricular internal diameter in diastole |

| sGC | soluble guanylate cyclase |

| SGLT2i | sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor(s) |

| TAPSE | tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion |

| TRgrad | tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient |

| S′ | tricuspid lateral annular systolic velocity |

References

- Mcmurray, J.J.V.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; Rouleau, J.L.; Shi, V.C.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; et al. Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition versus Enalapril in Heart Failure. PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, E895–E1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, K.; Butler, J.; Fonarow, G.C. Residual risk in heart failure and the need for simultaneous implementation and innovation. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 1477–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voors, A.A.; Angermann, C.E.; Teerlink, J.R.; Collins, S.P.; Kosiborod, M.; Biegus, J.; Ferreira, J.P.; Nassif, M.E.; Psotka, M.A.; Tromp, J.; et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: A multinational randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Yang, M.; Manzi, M.A.; Hess, G.P.; Patel, M.J.; Rhodes, T.; Givertz, M.M. Clinical Course of Patients With Worsening Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC 2019, 73, 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojda, G. Interactions between NO and reactive oxygen species: Pathophysiological importance in atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetes and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999, 43, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernow, J.; Jung, C. Arginase as a potential target in the treatment of cardiovascular disease: Reversal of arginine steal? Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, F.; Monge, J.C.; Gordon, A.; Cernacek, P.; Blais, D.; Stewart, D.J. Lack of Role for Nitric Oxide (NO) in the Selective Destabilization of Endothelial NO Synthase mRNA by Tumor Necrosis Factor–α. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1995, 15, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletti, L.; Curello, S.; Bachetti, T.; Malacarne, F.; Gaia, G.; Comini, L.; Volterrani, M.; Bonetti, P.; Parrinello, G.; Cadei, M.; et al. Serum from Patients with Severe Heart Failure Downregulates eNOS and Is Proapoptotic. Circulation 1999, 100, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, E.J.; Kass, D.A. Cyclic GMP signaling in cardiovascular pathophysiology and therapeutics. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 122, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandner, P. From molecules to patients: Exploring the therapeutic role of soluble guanylate cyclase stimulators. Biol. Chem. 2018, 399, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghiade, M.; Greene, S.J.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Lam, C.S.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Ponikowski, P.; Shah, S.J.; Solomon, S.D.; Kraigher-Krainer, E.; et al. Effect of Vericiguat, a Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulator, on Natriuretic Peptide Levels in Patients with Worsening Chronic Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: The SOCRATES-REDUCED Randomized Trial. JAMA 2015, 314, 2251–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, P.W.; Pieske, B.; Anstrom, K.J.; Ezekowitz, J.; Hernandez, A.F.; Butler, J.; Lam, C.S.; Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Jia, G.; et al. Vericiguat in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1883–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranek, M.J.; Terpstra, E.J.M.; Li, J.; Kass, D.A.; Wang, X. Protein Kinase G Positively Regulates Proteasome-Mediated Degradation of Misfolded Proteins. Circultion 2013, 128, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranek, M.J.; Kokkonen-Simon, K.M.; Chen, A.; Dunkerly-Eyring, B.L.; Vera, M.P.; Oeing, C.U.; Patel, C.H.; Nakamura, T.; Zhu, G.; Bedja, D.; et al. PKG1-modified TSC2 regulates mTORC1 activity to counter adverse cardiac stress. Nature 2019, 566, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, B. Interference of antihypertrophic molecules and signaling pathways with the Ca2+?calcineurin?NFAT cascade in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 63, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, H.; Tsuruda, T.; Sekita, Y.; Hatakeyama, K.; Imamura, T.; Kato, J.; Asada, Y.; Stasch, J.-P.; Kitamura, K. Pressure-independent effects of pharmacological stimulation of soluble guanylate cyclase on fibrosis in pressure-overloaded rat heart. Hypertens. Res. 2009, 32, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajec, T.; Poglajen, G. Targeting the NO–sGC–cGMP Pathway: Mechanisms of Action of Vericiguat in Chronic Heart Failure. Cells 2025, 14, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.G.; Trikalinos, T.A.; Kent, D.M.; Antonopoulos, G.V.; Konstam, M.A.; Udelson, J.E. Quantitative Evaluation of Drug or Device Effects on Ventricular Remodeling as Predictors of Therapeutic Effects on Mortality in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC 2010, 56, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poglajen, G.; Frljak, S.; Zemljic, G.; Cerar, A.; Knezevic, I.; Vrtovec, B. Clinical and echocardiographic effects of vericiguat therapy in advanced heart failure patinets undergoing LVAD support. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 284. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 16, 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieske, B.; Pieske-Kraigher, E.; Lam, C.S.; Melenovský, V.; Sliwa, K.; Lopatin, Y.; Arango, J.L.; Bahit, M.C.; O’COnnor, C.M.; Patel, M.J.; et al. Effect of vericiguat on left ventricular structure and function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The VICTORIA echocardiographic substudy. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2023, 25, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, J.; Ma, Y.; Guan, X.; Wang, S.; Chang, Y. Efficacy of vericiguat in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A prospective observational study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallash, M.; Frishman, W.H. Vericiguat, a Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulator Approved for Heart Failure Treatment. Cardiol. Rev. 2025, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Vitiello, L.; Milani, F.; Volterrani, M.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Tomino, C.; Bonassi, S. New Therapeutics for Heart Failure Worsening: Focus on Vericiguat. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, J.; Banchs, J.; Parker, H.; Cornwell, W. Right ventricular function across the spectrum of health and disease. Heart 2022, 109, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koitabashi, N.; Aiba, T.; Hesketh, G.G.; Rowell, J.; Zhang, M.; Takimoto, E.; Tomaselli, G.F.; Kass, D.A. Cyclic GMP/PKG-dependent inhibition of TRPC6 channel activity and expression negatively regulates cardiomyocyte NFAT activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 48, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, S.H.; Busch, J.L.; Corbin, J.D. cGMP-Dependent Protein Kinases and cGMP Phosphodiesterases in Nitric Oxide and cGMP Action. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 525–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rüdebusch, J.; Benkner, A.; Nath, N.; Fleuch, L.; Kaderali, L.; Grube, K.; Klingel, K.; Eckstein, G.; Meitinger, T.; Fielitz, J.; et al. Stimulation of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) by riociguat attenuates heart failure and pathological cardiac remodelling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 179, 2430–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barefield, D.; Sadayappan, S. Phosphorylation and function of cardiac myosin binding protein-C in health and disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 48, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thoonen, R.; Giovanni, S.; Govindan, S.; Lee, D.I.; Wang, G.-R.; Calamaras, T.D.; Takimoto, E.; Kass, D.A.; Sadayappan, S.; Blanton, R.M. Molecular Screen Identifies Cardiac Myosin–Binding Protein-C as a Protein Kinase G-Iα Substrate. Circ. Heart Fail. 2015, 8, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, M.; Kötter, S.; Grützner, A.; Lang, P.; Andresen, C.; Redfield, M.M.; Butt, E.; dos Remedios, C.G.; Linke, W.A. Protein Kinase G Modulates Human Myocardial Passive Stiffness by Phosphorylation of the Titin Springs. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronzwaer, J.G.; Paulus, W.J. Nitric oxide: The missing lusitrope in failing myocardium. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 2453–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, J.R.d.A.R.R.; Cardoso, J.N.; Cardoso, C.M.d.R.; Pereira-Barretto, A.C. Reverse Cardiac Remodeling: A Marker of Better Prognosis in Heart Failure. Arq. Bras. de Cardiol. 2015, 104, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekowitz, J.A.; O’cOnnor, C.M.; Troughton, R.W.; Alemayehu, W.G.; Westerhout, C.M.; Voors, A.A.; Butler, J.; Lam, C.S.; Ponikowski, P.; Emdin, M.; et al. N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and Clinical Outcomes. JACC Heart Fail. 2020, 8, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.S.P.; Giczewska, A.; Sliwa, K.; Edelmann, F.; Refsgaard, J.; Bocchi, E.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; O’cOnnor, C.M.; Roessig, L.; et al. Clinical Outcomes and Response to Vericiguat According to Index Heart Failure Event. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senni, M.; Lopez-Sendon, J.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Ponikowski, P.; Nkulikiyinka, R.; Freitas, C.; Vlajnic, V.M.; Roessig, L.; Pieske, B. Vericiguat and NT-proBNP in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Analyses from the VICTORIA trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 3791–3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.G.; Girón, M.F.d.S.; Marco, M.d.V.G.; Jorge, L.R.; Saavedra, C.P.; Bou, E.M.; Guerra, R.A.; Dorta, E.C.; Quintana, A.G. Clinical profile, associated events and safety of vericiguat in a real-world cohort: The VERITA study. ESC Heart Fail. 2024, 11, 4222–4230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, G.; Rubattu, S.; Volpe, M. Targeting Cyclic Guanylate Monophosphate in Resistant Hypertension and Heart Failure: Are Sacubitril/Valsartan and Vericiguat Synergistic and Effective in Both Conditions? High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2021, 28, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopaschuk, G.D.; Verma, S. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefits of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Dong, M.; Sun, X.; Jia, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, X.; Lu, H. Vericiguat in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients on guideline-directed medical therapy: Insights from a 6-month real-world study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 417, 132524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Koning, M.-S.L.Y.; Emmens, J.E.; Romero-Hernández, E.; Bourgonje, A.R.; Assa, S.; Figarska, S.M.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Samani, N.J.; Ng, L.L.; Lang, C.C.; et al. Systemic oxidative stress associates with disease severity and outcome in patients with new-onset or worsening heart failure. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2023, 112, 1056–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurer, S.; Pioch, S.; Pabst, T.; Opitz, N.; Schmidt, P.M.; Beckhaus, T.; Wagner, K.; Matt, S.; Gegenbauer, K.; Geschka, S.; et al. Nitric Oxide–Independent Vasodilator Rescues Heme-Oxidized Soluble Guanylate Cyclase From Proteasomal Degradation. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonen, R.; Cauwels, A.; Decaluwe, K.; Geschka, S.; Tainsh, R.E.; Delanghe, J.; Hochepied, T.; De Cauwer, L.; Rogge, E.; Voet, S.; et al. Cardiovascular and pharmacological implications of haem-deficient NO-unresponsive soluble guanylate cyclase knock-in mice. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; McMullan, C.J.; Anstrom, K.J.; Barash, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Borentain, M.; Corda, S.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Felker, G.M.; Gates, D.; et al. Vericiguat in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (VICTOR): A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2025, 406, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.V.; Van Nguyen, S.; Le Pham, A.; Nguyen, B.T.; Van Hoang, S. Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in the new era of heart failure treatment. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0309948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Study Population (n = 24) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 62.8 (9.3) |

| Gender (male) | 22 (91.7%) |

| NYHA functional class | |

| II | 1 (4.2%) |

| III | 16 (66.7%) |

| IV | 7 (29.2%) |

| Etiology of heart failure | |

| DCMP | 16 (66.7%) |

| IHD | 8 (33.3%) |

| Laboratory measurements, mean (SD) | |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 139.7 (3.5) |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.7 (0.5) |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 103.4 (23.2) |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI)/1.73 m2 | 62.0 (16.2) |

| Bilirubin (umol/L) | 16.2 (12.0) |

| AST (ukat/L) | 0.5 (0.2) |

| ALT (ukat/L) | 0.5 (0.2) |

| gGT (ukat/L) | 1.2 (1.1) |

| NT-proBNP (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 1829.0 (658.3–4457.3) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 152.3 (19.9) |

| Leukocytes (109/L) | 8.0 (2.3) |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 195.2 (48.2) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (37.5%) |

| Arterial hypertension | 14 (58.3%) |

| COPD | 1 (4.2%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 11 (45.8%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 6 (25.0%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 9 (37.5%) |

| Medications | |

| ARNI | 23 (95.8%) |

| ACEi/ARB | 1 (4.2%) |

| BB | 23 (95.8%) |

| MRA | 24 (100%) |

| SGLT2i | 23 (95.8%) |

| Digitalis | 3 (12.5%) |

| Diuretics | 14 (58.3%) |

| Statins | 14 (58.3%) |

| Oral anticoagulant | 11 (45.8%) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 5 (20.8%) |

| Variable | Baseline n = 24 | 6M n = 24 | Change | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVOT VTI (cm) | 14.8 ± 3.7 | 16.1 ± 3.8 | 1.6 ± 2.7 | 0.011 |

| LVEDV (ml) | 213.3 ± 54.9 | 197.6 ± 65.6 | −15.7 ± 37.4 | 0.051 |

| LVESV (ml) | 149.5 (112.5–175.5) | 129.0 (79.5–166.5) | −14.5 (−36.0–4.0) | 0.031 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 63.8 ± 5.9 | 62.8 ± 7.0 | −1.0 ± 4.7 | 0.328 |

| LVESD (mm) | 55.3 ± 6.0 | 53.5 ± 8.4 | −1.8 ± 5.7 | 0.145 |

| E/e′ | 14.1 ± 5.1 | 15.3 ± 7.3 | 1.0 ± 6.0 | 0.473 |

| RVIDd (mm) | 40.5 ± 5.8 | 37.9 ± 7.0 | −2.3 ± 3.8 | 0.002 |

| TRgrad (mmHg) | 34.9 ± 9.9 | 33.2 ± 10.1 | −1.7 ± 5.3 | 0.130 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bajec, T.; Žorž, N.; Ugovšek, S.; Zemljič, G.; Cerar, A.; Frljak, S.; Okrajšek, R.; Girandon Sušanj, P.; Šebeštjen, M.; Vrtovec, B.; et al. Vericiguat Therapy Is Associated with Reverse Myocardial Remodeling in Chronic Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010017

Bajec T, Žorž N, Ugovšek S, Zemljič G, Cerar A, Frljak S, Okrajšek R, Girandon Sušanj P, Šebeštjen M, Vrtovec B, et al. Vericiguat Therapy Is Associated with Reverse Myocardial Remodeling in Chronic Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleBajec, Tine, Neža Žorž, Sabina Ugovšek, Gregor Zemljič, Andraž Cerar, Sabina Frljak, Renata Okrajšek, Petra Girandon Sušanj, Miran Šebeštjen, Bojan Vrtovec, and et al. 2026. "Vericiguat Therapy Is Associated with Reverse Myocardial Remodeling in Chronic Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010017

APA StyleBajec, T., Žorž, N., Ugovšek, S., Zemljič, G., Cerar, A., Frljak, S., Okrajšek, R., Girandon Sušanj, P., Šebeštjen, M., Vrtovec, B., & Poglajen, G. (2026). Vericiguat Therapy Is Associated with Reverse Myocardial Remodeling in Chronic Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010017