Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation Prediction in Patients with CIED by a Novel Deep Learning Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

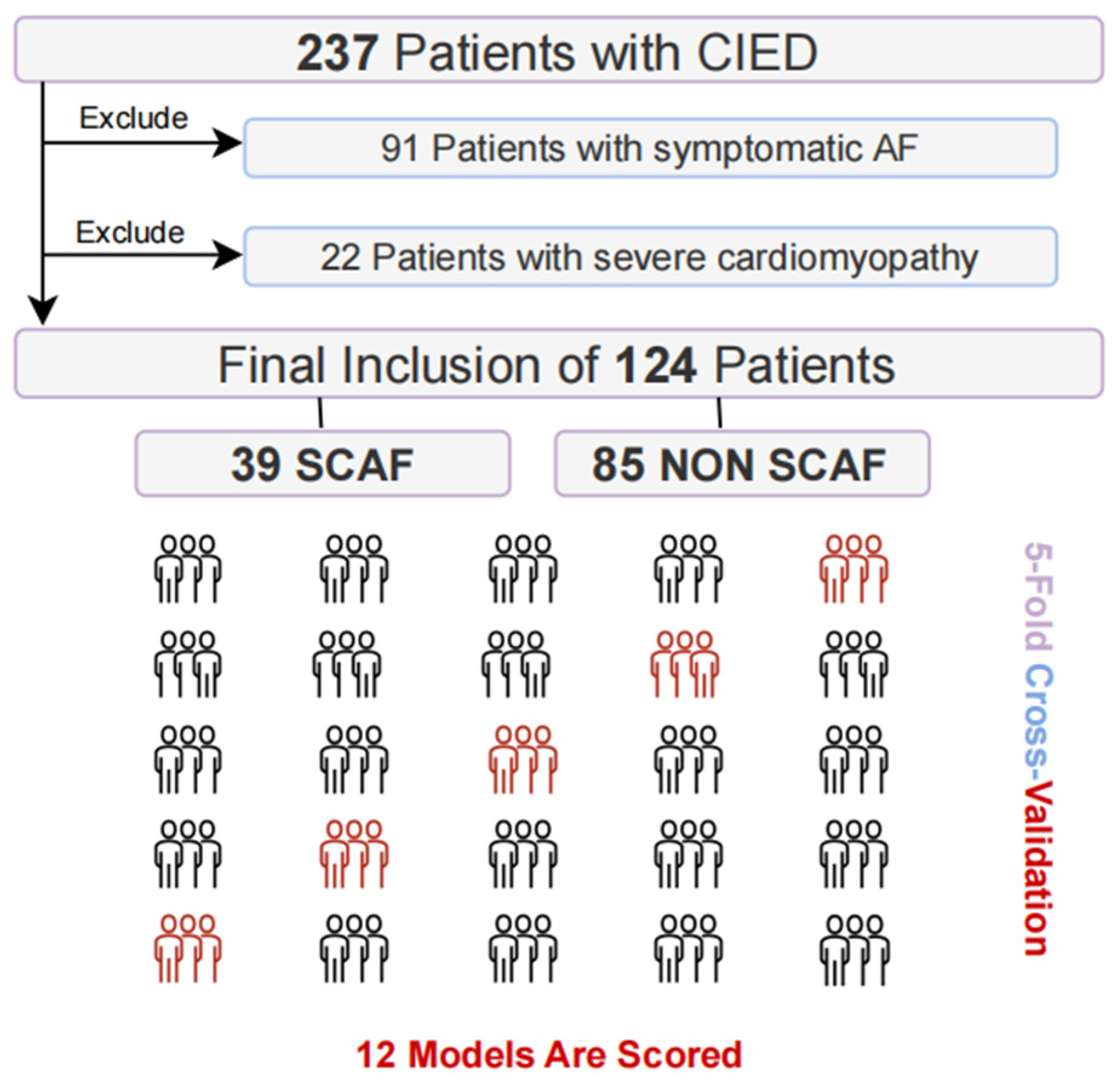

2.1. Patient Enrollment and Clinical Data Collection

2.2. Data Preprocessing

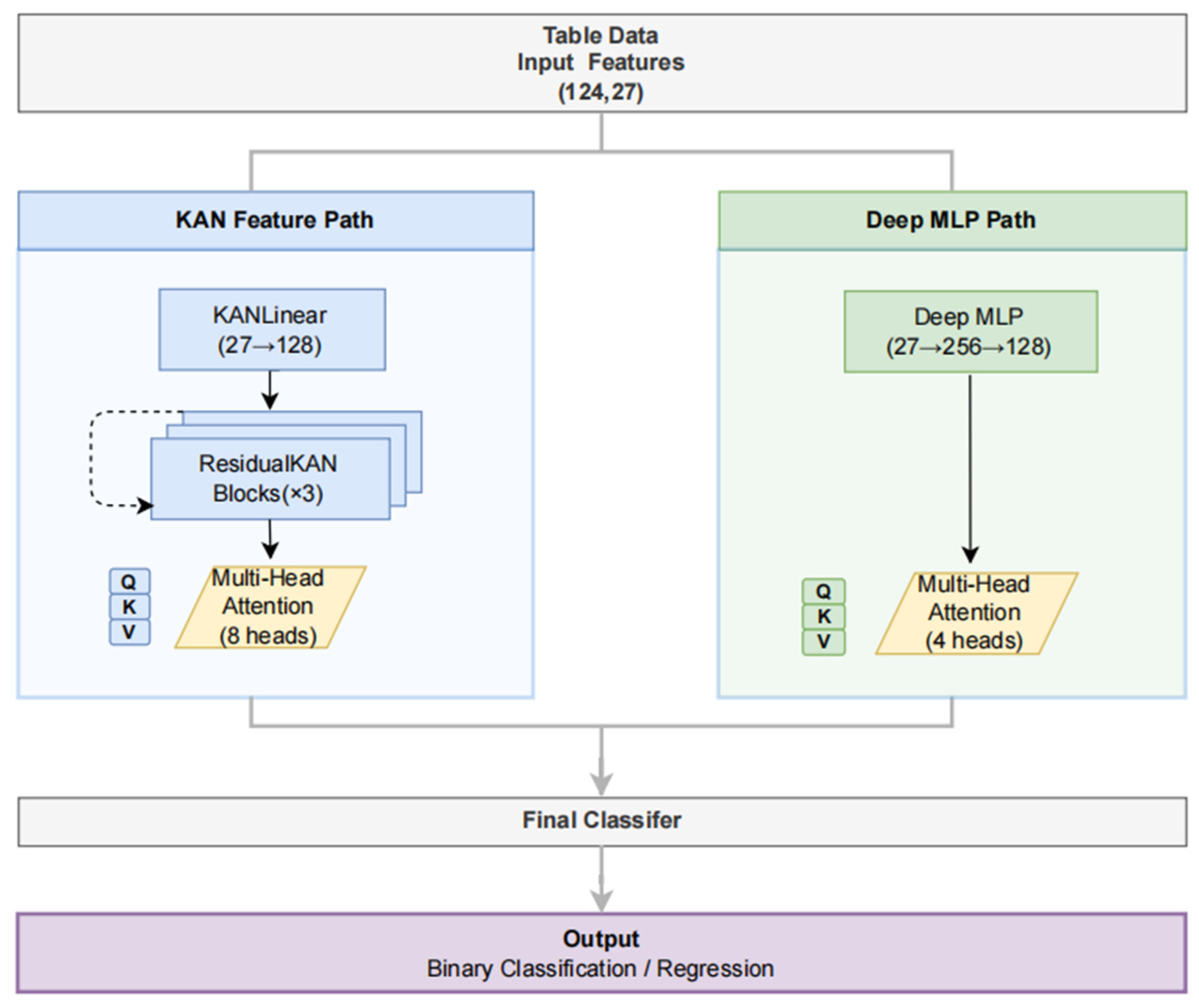

2.3. Model Development

2.4. Baseline Models

2.5. Model Training and Evaluation

2.6. Model Interpretability Analysis

2.7. Knowledge Distillation for Clinical Risk Scoring

2.8. External Validation

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

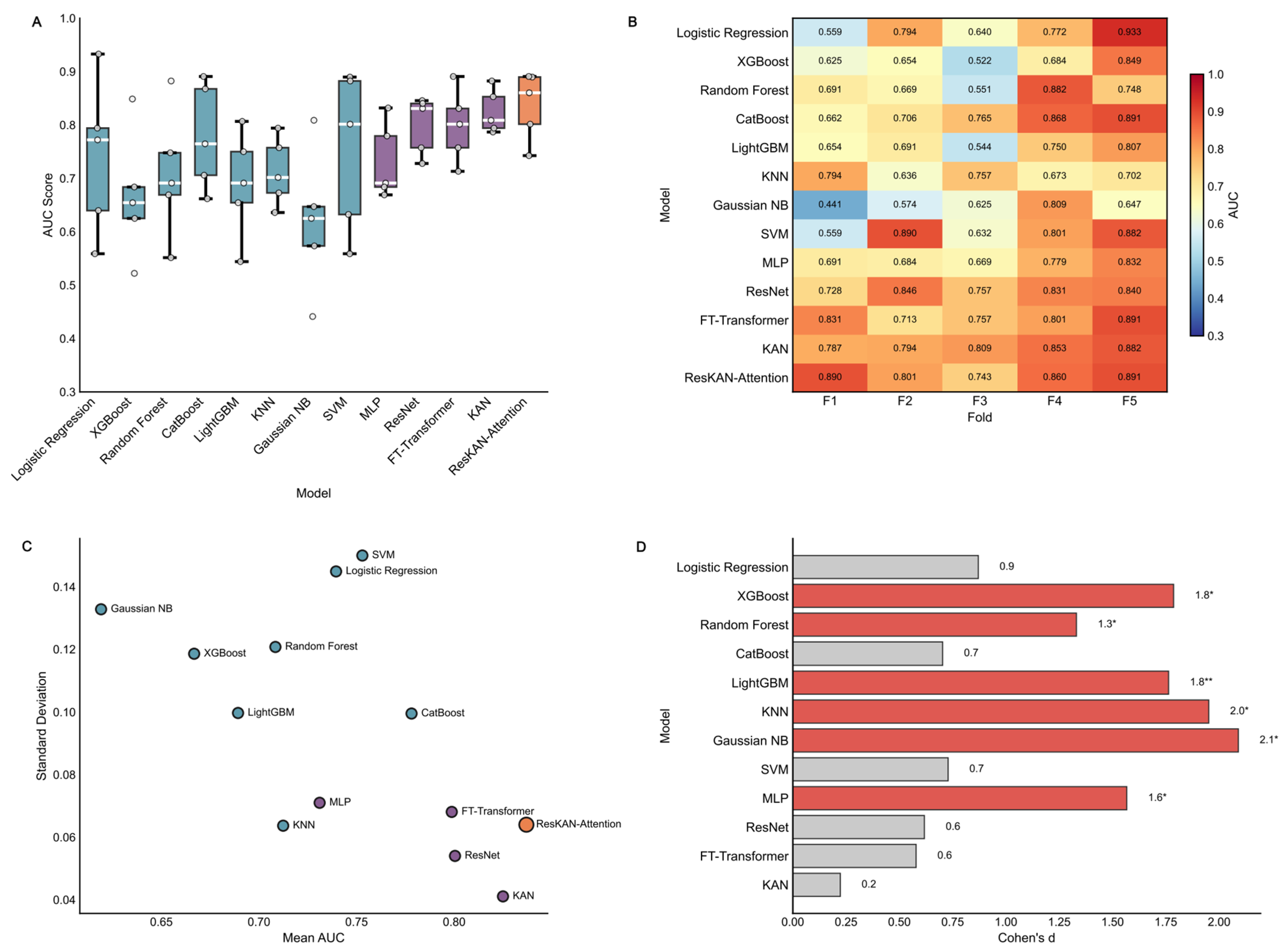

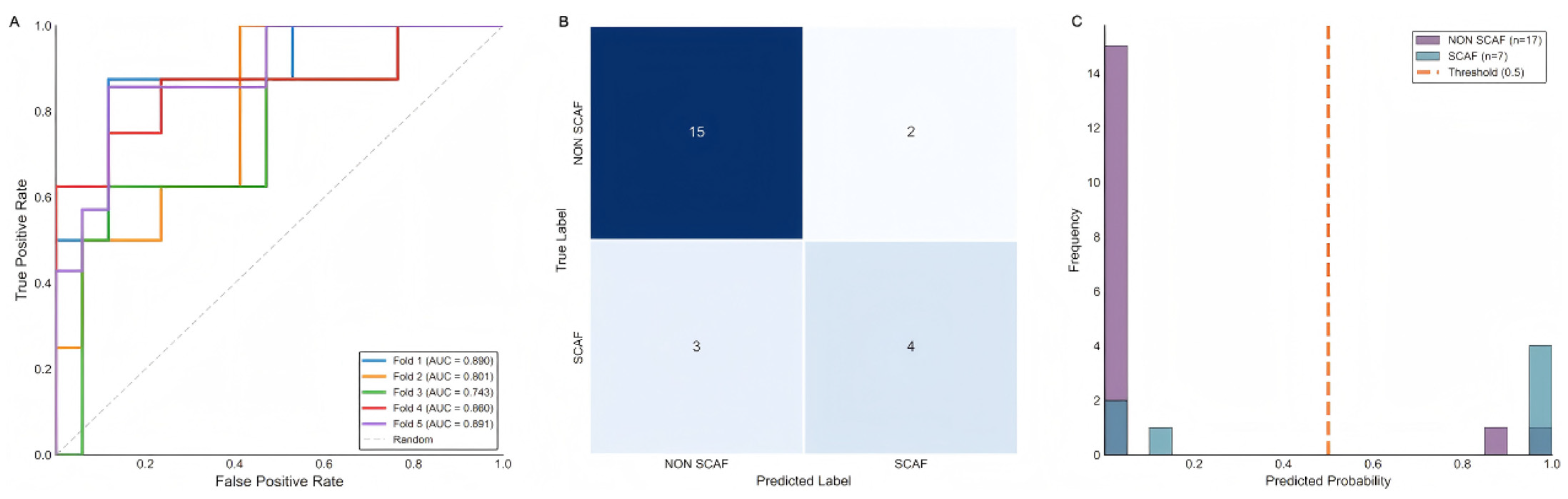

3.2. Model Performance

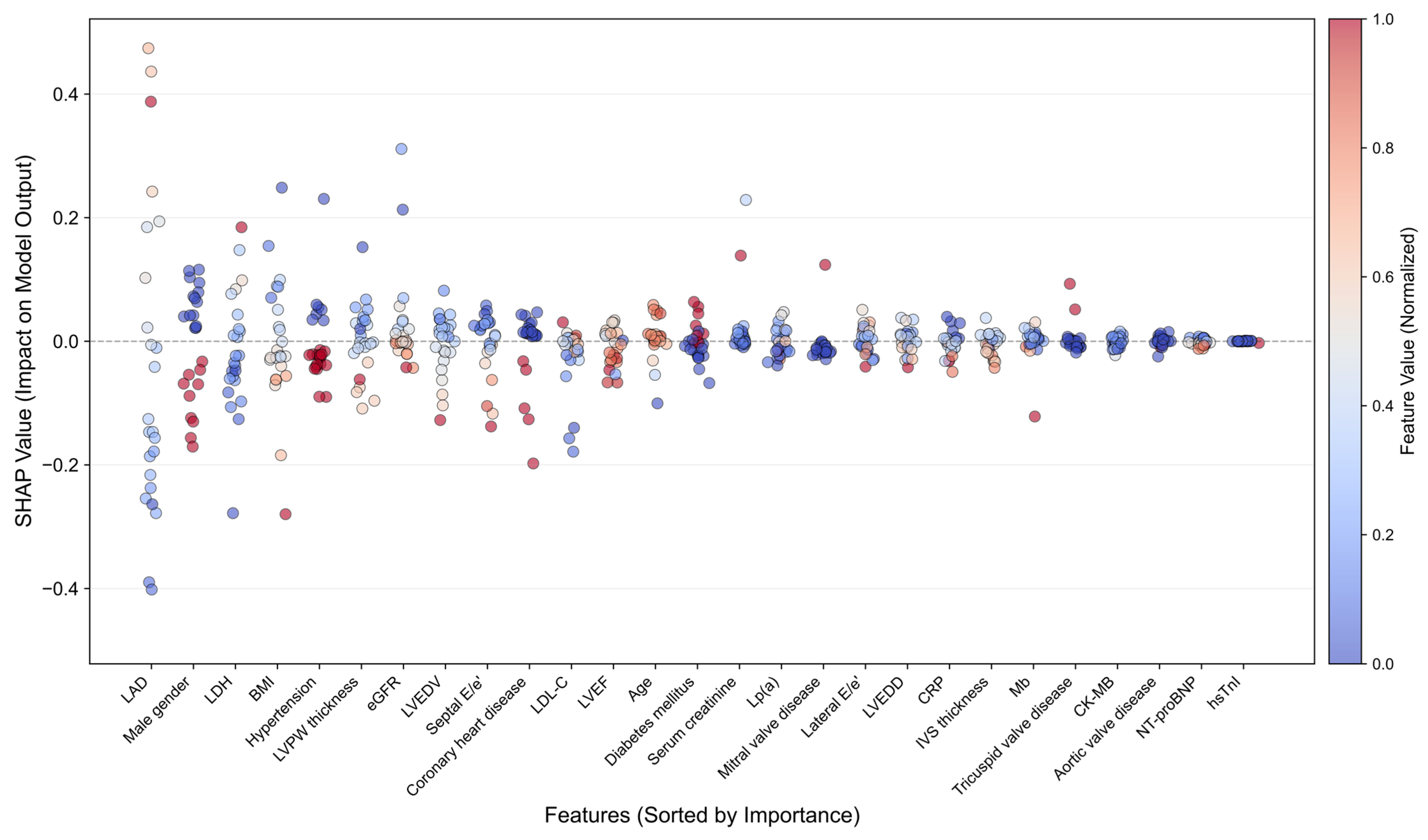

3.3. Model Interpretability Analysis

3.4. Development and Validation of Clinical SCAF Risk Scoring

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCAF | Subclinical atrial fibrillation |

| CIED | cardiac implantable electronic device |

| KAN | Kolmogorov–Arnold Network |

| LAD | left atrial diameter |

| AHRE | atrial high-rate episode |

| MLP | multilayer perceptrons |

| ResNet | residual networks |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive exPlanations |

| LIME | Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations |

References

- Healey, J.S.; Connolly, S.J.; Gold, M.R.; Israel, C.W.; Gelder, I.C.V.; Capucci, A.; Lau, C.P.; Fain, E.; Yang, S.; Bailleul, C.; et al. Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation and the Risk of Stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.M.; Ruff, C.T. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation: Weighing the absolute risks and benefits. Circulation 2024, 149, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, K.; Pastori, D.; Li, Y.-G.; Székely, O.; Shahid, F.; Boriani, G.; Lip, G.Y.H. Atrial high rate episodes in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: Implications for clinical outcomes. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2019, 108, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.; De Potter, T.J.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Developed by the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Endorsed by the European Stroke Organisation (ESO). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Attia, Z.I.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Asirvatham, S.J.; Deshmukh, A.J.; Gersh, B.J.; Carter, R.E.; Yao, X.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Erickson, B.J.; et al. An artificial intelligence-enabled ECG algorithm for the identification of patients with atrial fibrillation during sinus rhythm: A retrospective analysis of outcome prediction. Lancet 2019, 394, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Vaidya, S.; Ruehle, F.; Halverson, J.; Soljačić, M.; Hou, T.; Tegmark, M. KAN: Kolmogorov-arnold networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:240419756. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, C.; Lee, G.J.; Teo, Y.H.; Teo, Y.N.; Toh, E.M.; Li, T.Y.; Guo, C.Y.; Ding, J.; Zhou, X.; Teoh, H.L. Machine Learning Modeling to Predict Atrial Fibrillation Detection in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source Patients. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheini, M.; Ren, X.; May, J. Cross-attention is all you need: Adapting pretrained transformers for machine translation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.08771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorishniy, Y.; Rubachev, I.; Khrulkov, V.; Babenko, A. Revisiting deep learning models for tabular data. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 18932–18943. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I.; Hutter, F. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, Proceedings of 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Guyon, I., von Luxburg, U., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garreau, D.; Luxburg, U. Explaining the explainer: A first theoretical analysis of LIME. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Sicily, Italy, 26–28 August 2020; pp. 1287–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, S.; Pfeifer, J.M.; Ulloa-Cerna, A.E.; Nemani, A.; Carbonati, T.; Jing, L.; vanMaanen, D.P.; Hartzel, D.N.; Ruhl, J.A.; Lagerman, B.F.; et al. Deep Neural Networks Can Predict New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation From the 12-Lead ECG and Help Identify Those at Risk of Atrial Fibrillation–Related Stroke. Circulation 2021, 143, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Cho, M.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.; Oh, I.-Y.; Cho, Y.; Lee, J.H. Artificial intelligence predicts undiagnosed atrial fibrillation in patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source using sinus rhythm electrocardiograms. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, T.; Liang, Z.; Xia, Y.; Yan, L.; Xing, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, S. Mobile photoplethysmographic technology to detect atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2365–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhubl, S.R.; Waalen, J.; Edwards, A.M.; Ariniello, L.M.; Mehta, R.R.; Ebner, G.S.; Carter, C.; Baca-Motes, K.; Felicione, E.; Sarich, T.; et al. Effect of a Home-Based Wearable Continuous ECG Monitoring Patch on Detection of Undiagnosed Atrial Fibrillation: The mSToPS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, P.; D’Onofrio, A.; Vitulano, G.; Calo’, L.; Bertini, M.; Santini, L.; Savarese, G.; Santobuono, V.E.; Lavalle, C.; Viscusi, M. Clinical value of multiple sensors contributing to a composite heart failure ICD monitoring index. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, ehae666.3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, W.L.; Morganroth, J.; Pearlman, A.S.; Clark, C.E.; Redwood, D.R.; Itscoitz, S.B.; Epstein, S.E. Relation between echocardiographically determined left atrial size and atrial fibrillation. Circulation 1976, 53, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, C.; Liu, P.; Zhang, M.; Niu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhong, G. Low-normal free triiodothyronine as a predictor of post-operative atrial fibrillation after surgical coronary revascularization. J. Thorac. Dis. 2024, 16, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, S.; Wenger, N. Gender differences in atrial fibrillation: A review of epidemiology, management, and outcomes. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2019, 15, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joglar, J.A.; Chung, M.K.; Armbruster, A.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Chyou, J.Y.; Cronin, E.M.; Deswal, A.; Eckhardt, L.L.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Gopinathannair, R. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS guideline for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 109–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total | SCAF Group | Non-SCAF Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 124) | (N = 39, 31.5%) | (N = 85, 68.5%) | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 72.0 ± 10.8 | 72.9 ± 7.8 | 71.5 ± 12.0 | 0.43 |

| Male gender | 68 (54.8) | 14 (35.9) | 54 (63.5) | 0.006 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 3.7 | 23.6 ± 4.2 | 24.1 ± 3.4 | 0.47 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 84 (67.7) | 24 (61.5) | 60 (70.6) | 0.41 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 38 (30.6) | 10 (25.6) | 28 (32.9) | 0.53 |

| Coronary heart disease | 33 (26.6) | 6 (15.4) | 27 (31.8) | 0.08 |

| Aortic valve disease | 6 (4.8) | 2 (5.1) | 4 (4.7) | 1 |

| Mitral valve disease | 6 (4.8) | 5 (12.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.01 |

| Tricuspid valve disease | 9 (7.3) | 5 (12.8) | 4 (4.7) | 0.14 |

| Biochemical Parameters | ||||

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 564.0 ± 911.1 | 926.2 ± 1271.3 | 393.8 ± 620.0 | 0.02 |

| hsTnI (pg/mL) | 135.7 ± 1224.1 | 25.9 ± 56.3 | 183.3 ± 1465.3 | 0.33 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 10.2 ± 23.2 | 4.0 ± 6.2 | 13.1 ± 27.3 | 0.03 |

| Myoglobin (ng/mL) | 31.8 ± 21.1 | 29.3 ± 14.6 | 32.9 ± 23.3 | 0.3 |

| CK-MB (ng/mL) | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 0.98 |

| LDH (IU/L) | 218.3 ± 73.0 | 224.1 ± 50.5 | 215.6 ± 81.3 | 0.5 |

| Lp(a) (g/L) | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.33 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 0.29 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 83.1 ± 25.6 | 83.5 ± 29.8 | 82.9 ± 23.6 | 0.92 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 74.9 ± 17.8 | 71.7 ± 19.1 | 76.4 ± 17.1 | 0.2 |

| Echocardiographic Parameters | ||||

| Left atrial diameter (mm) | 41.5 ± 4.7 | 43.9 ± 5.0 | 40.3 ± 4.1 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 65.2 ± 7.0 | 65.2 ± 5.0 | 65.3 ± 7.8 | 0.99 |

| LVEDD (mm) | 49.5 ± 6.0 | 48.2 ± 5.2 | 50.1 ± 6.2 | 0.08 |

| LVEDV (mL) | 118.2 ± 32.1 | 112.4 ± 28.6 | 120.7 ± 33.4 | 0.18 |

| IVS thickness (mm) | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 10.0 ± 1.9 | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 0.89 |

| LVPW thickness (mm) | 9.1 ± 1.1 | 8.9 ± 1.3 | 9.2 ± 1.1 | 0.34 |

| Septal E/e′ | 12.4 ± 6.5 | 13.8 ± 6.5 | 11.8 ± 6.5 | 0.14 |

| Lateral E/e′ | 9.0 ± 3.6 | 9.9 ± 4.4 | 8.5 ± 3.1 | 0.09 |

| Model | AUC | ACC | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Machine Learning | |||||

| Logistic Regression | 0.7395 ± 0.1296 | 0.7110 ± 0.0976 | 0.5406 ± 0.1056 | 0.6750 ± 0.2031 | 0.5897 ± 0.1344 |

| XGBoost | 0.6668 ± 0.1061 | 0.6943 ± 0.0570 | 0.5107 ± 0.0896 | 0.4179 ± 0.1559 | 0.4529 ± 0.1185 |

| Random Forest | 0.7084 ± 0.1080 | 0.7017 ± 0.0401 | 0.5589 ± 0.1079 | 0.4107 ± 0.0492 | 0.4644 ± 0.0228 |

| CatBoost | 0.7782 ± 0.0890 | 0.6860 ± 0.0436 | 0.5000 ± 0.0777 | 0.3393 ± 0.1485 | 0.3881 ± 0.1273 |

| LightGBM | 0.6893 ± 0.0892 | 0.6943 ± 0.0570 | 0.5107 ± 0.0896 | 0.4179 ± 0.1559 | 0.4529 ± 0.1185 |

| KNN | 0.7124 ± 0.0569 | 0.7013 ± 0.1069 | 0.5466 ± 0.1336 | 0.6679 ± 0.0956 | 0.5920 ± 0.1041 |

| Gaussian NB | 0.6191 ± 0.1188 | 0.5393 ± 0.0921 | 0.3411 ± 0.0512 | 0.5214 ± 0.3063 | 0.3752 ± 0.1388 |

| SVM | 0.7529 ± 0.1342 | 0.7417 ± 0.0707 | 0.6052 ± 0.1279 | 0.7000 ± 0.2031 | 0.6239 ± 0.0931 |

| Deep Learning | |||||

| MLP | 0.7311 ± 0.0635 | 0.7183 ± 0.0480 | 0.5750 ± 0.1000 | 0.4429 ± 0.1571 | 0.4857 ± 0.1092 |

| ResNet | 0.8004 ± 0.0483 | 0.7823 ± 0.0595 | 0.6819 ± 0.1009 | 0.5643 ± 0.1251 | 0.5643 ± 0.1251 |

| FT-Transformer | 0.7987 ± 0.0609 | 0.7190 ± 0.0930 | 0.5483 ± 0.1009 | 0.7000 ± 0.2179 | 0.6027 ± 0.1351 |

| KAN | 0.8250 ± 0.0367 | 0.7347 ± 0.0576 | 0.5829 ± 0.0795 | 0.6179 ± 0.1530 | 0.5885 ± 0.0959 |

| Advanced Deep Learning Model | |||||

| ResKAN-Attention | 0.8370 ± 0.0572 | 0.7503 ± 0.1164 | 0.6603 ± 0.2122 | 0.6393 ± 0.0591 | 0.6333 ± 0.1124 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lan, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhang, N.; Cao, Q.; Jin, Q.; Luo, Q.; Wei, Y.; Bao, Y.; Lin, C.; Pan, W.; et al. Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation Prediction in Patients with CIED by a Novel Deep Learning Framework. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2026, 13, 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010018

Lan Y, Lin C, Zhang N, Cao Q, Jin Q, Luo Q, Wei Y, Bao Y, Lin C, Pan W, et al. Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation Prediction in Patients with CIED by a Novel Deep Learning Framework. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2026; 13(1):18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010018

Chicago/Turabian StyleLan, Yongying, Chengze Lin, Ning Zhang, Qing Cao, Qi Jin, Qingzhi Luo, Yue Wei, Yangyang Bao, Changjian Lin, Wenqi Pan, and et al. 2026. "Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation Prediction in Patients with CIED by a Novel Deep Learning Framework" Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 13, no. 1: 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010018

APA StyleLan, Y., Lin, C., Zhang, N., Cao, Q., Jin, Q., Luo, Q., Wei, Y., Bao, Y., Lin, C., Pan, W., Chen, K., Wu, L., & Xie, Y. (2026). Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation Prediction in Patients with CIED by a Novel Deep Learning Framework. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease, 13(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd13010018