Abstract

Cardiac myosin inhibitors have been shown to improve diastolic function in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). Comparative studies to evaluate the diastolic effects of mavacamten versus alcohol septal ablation (ASA) have yet to be examined. In this single-center retrospective analysis, we compared echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function in adult patients with obstructive HCM treated with mavacamten (n = 23) or ASA (n = 22). Baseline imaging was obtained prior to therapy, and follow-up imaging was obtained five months after ASA and or initiation of mavacamten. Left-sided filling pressures (E/e’) improved with both ASA (18.6 versus 15.3, p < 0.001) and mavacamten (17.4 versus 13.5, p = 0.01). Among patients who underwent ASA, mitral annular tissue velocity (e’) was increased at the lateral annulus (6.0 versus 6.1, p = 0.02) with a trend to improvement at the septum (4.0 versus 5.0, p = 0.14). Similarly, among patients treated with mavacamten, septal e’ was increased (6.0 versus 6.7, p < 0.01) and a trended improvement was observed for the lateral e’ (5.7 versus 7.0, p = 0.06). Mavacamten therapy was also associated with an improvement in the LA volume index (45.6 versus 34.5, p < 0.001). Patients treated with ASA were older, more likely to have used tobacco, and had greater limitation in functional status. In this retrospective analysis, ASA and mavacamten were similarly associated with improvements in echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function and left-sided filling pressures, though mavacamten had a more discernible effect on the left-atrial volume index. Larger studies are required to further characterize the relative efficacy of the two therapeutic modalities.

1. Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common familial cardiomyopathy and is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion [1,2]. The prevalence of HCM is estimated to be between 1:500 and 1:200 in the general population and impacts more than 20 million people worldwide [3,4]. Mutations associated with HCM disrupt sarcomere formation, causing myofibril disarray and cellular hypertrophy as determined histologically [5]. Structurally, HCM manifests with pathological thickness of the myocardium, tissue scarring, and ventricular stiffening, which are associated with the clinical features of heart failure [5].

Heart failure in the setting of HCM may be observed as a function of obstructive or non-obstructive left-ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) hemodynamics [6]. Two-thirds of patients with HCM exhibit obstructive hemodynamics. Heart failure associated with obstructive physiology is attributed to a narrowed outflow tract and steep pressure gradients (>30 mmHg at rest and >50 mmHg with provocation) across the LVOT that result from hypercontractility, ventricular thickness, and aberrations in the mitral valve apparatus [7,8,9,10]. Conversely, heart failure associated with non-obstructive physiology primarily results from diastolic heart disease ascribed to pathologic myocardial thickness, a small ventricular cavity, and impaired myocardial relaxation.

Pharmacologic agents that improve left-ventricular filling and reduce myocardial contractility, including beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and disopyramide, have historically served as first-line therapies in the treatment of obstructive HCM [1,2]. Septal-reduction therapies (SRTs), including alcohol septal ablation (ASA) and surgical myectomy, are considered in patients who have been either unable to tolerate or are refractory to first-line medical therapies [1,2,11,12,13]. ASA is a catheter-based approach aimed at thinning the interventricular septum (IVS) by delivering alcohol into the proximal septal perforators to induce a controlled myocardial infarction within the septum [14]. Historically, ASA is the preferred strategy for SRT in patients who are not candidates for surgical myectomy [2,15].

Myosin inhibitors have emerged as a novel therapeutic tool to dampen myocardial contractility and relieve LVOT obstruction in HCM [2,16,17,18,19,20,21]. These small molecules inhibit myosin-head-associated ATPase activity and thereby reduce actin–myosin cross-bridging within the sarcomere [16,17]. Mavacamten is the first commercially available myosin inhibitor that has been shown to improve cardiac hemodynamics and functional performance in patients with obstructive HCM [18,19,22]. Emerging evidence suggests cardiac myosin inhibitors may directly improve echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function [22,23,24]. We have previously observed that septal myectomy is associated with improvements in diastolic function in patients with HCM. Additionally, we recently reported that SRT with ASA yields comparable improvements in obstructive hemodynamics and patient functional status when compared to mavacamten [23]. In this follow-up study, we sought to examine how mavacamten compares with ASA in modifying parameters of diastolic function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and End Points

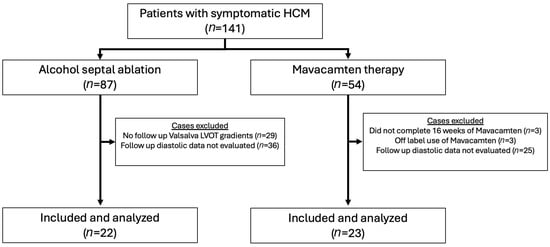

Patients of the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute (BCVI) of Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, IL, managed for HCM from July 2012 to May 2024 were sampled for this study. Patients who had undergone ASA (n = 87) were identified through individual chart review. Patients currently or previously treated with mavacamten were identified through the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) enrollment at Northwestern (n = 54) (Figure 1). Clinical and echocardiographic data were collected and reported for individuals at baseline and at 5 months (average 5.1 months; interquartile range (IQR) 3.5–6.0 months) following ASA or initiation of mavacamten, respectively. Mavacamten dosing was coordinated as described in the prescribing information literature issued by Bristol Myers Squibb. In the ASA arm, 29 patients were excluded because follow-up echocardiograms with assessment of Valsalva-induced LVOT gradients were not available between 3 and 12 months of the procedure. Among the residual individuals, an additional 36 individuals were excluded because diastolic parameters were not obtained during follow-up imaging. In the mavacamten arm, six individuals were excluded. Three of these individuals were excluded because they had not completed at least 16 weeks of follow-up. One patient in the mavacamten cohort was excluded because dosing was initiated at a 2.5 mg dose, which is outside the parameters of the REMS dosing protocol, and two others were excluded because pre-treatment Valsalva outflow tract gradients were less than 50 mmHg. Among the residual individuals, an additional 25 were excluded because diastolic parameters were not obtained during follow-up imaging. NYHA class was determined by chart review and clinical documentation. Left-ventricular dysfunction requiring discontinuation of mavacamten therapy (LVEF < 50%) was not observed within 36 weeks of initiating therapy in any participants. Baseline characteristics are expressed as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency and percent (%) for categorical variables.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram illustrating patient selection for the study cohorts.

2.2. Imaging Assessment

Echocardiograms were performed in accordance with contemporary American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) guidelines [25]. LVOT gradients, mitral inflow (E and A), tissue Doppler annular velocities (E’), and left-atrial volume indices were assessed in accordance with ASE guidelines [26].

2.3. Statistics

Baseline and functional characteristics were reported as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or number (%). Demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes between treatment groups were compared using a two-sample t-test, the Chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Differences within each treatment group, between baseline and follow-up functional characteristics, were compared using the paired Student t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank test as appropriate. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS (v9.4, Cary NC, USA) and R version 4.2.2. Institutional Review Board approval at Northwestern University was obtained before the initiation of this study.

3. Results

The study groups comprised patients diagnosed with obstructive HCM who underwent ASA (n = 22) compared with patients who initiated treatment with mavacamten (n = 23). The two groups were similar with respect to multiple demographic criteria and elements of the medical history, including body mass index (BMI), sex distribution, history of hypertension, history of atrial fibrillation, presence of an in situ implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD), and prior use of beta blockers (p > 0.05 for all) (Table 1). Patients in the ASA group were older (76 versus 61 years, p < 0.001) and were more likely to have used tobacco (77% versus 13%, p < 0.001). Patients in the ASA arm were more likely to have been treated with non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (p = 0.002) and disopyramide (p = 0.047) and had a poorer functional status such that 71.4% described NYHA Class III limitations compared to 30.4% in the mavacamten arm (p = 0.007). There were three patients in the mavacamten arm and one patient in the ASA arm who had previously undergone septal reduction therapy. Similar observations were made within the larger study cohort prior to excluding patients who did not have echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function assessed during follow-up (Supplementary Materials Table S1).

Table 1.

Study cohort demographics, comorbidities, and medications.

Therapy with each of ASA and mavacamten was associated with a significant reduction in LVOT gradient over 5 months of observation (p < 0.001) (Table 2). There was no difference between the baseline LVOT gradient (78.2 versus 100.0 mmHg, p = 0.11) and follow-up LVOT gradients at 5 months (15.0 versus 23.0, p = 0.16) between the ASA- and mavacamten-treated groups, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline and 5-month outcomes between alcohol septal ablation and mavacamten for LVOT gradient, diastolic function parameters, LA volume index, and LA reservoir strain.

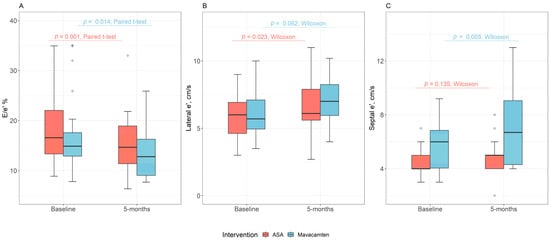

In the ASA group, 5 months after ASA, there was an increase in the lateral E’ tissue velocity (6.0 versus 6.1, p = 0.02), whereas the septal E’ tissue velocity trended up (4.0 versus 5.0, p = 0.14). Over this period, the lateral E/e’ (16.7 versus 12.2, p < 0.001), septal E/e’ (20.0 versus 18.0, p = 0.02), and average E/e’ (18.6 versus 15.3, p < 0.001) values were reduced (Table 2, Figure 2). Average E/A was reduced over the 5-month observation period (0.9 versus 0.8, p = 0.043). LA reservoir strain trended towards improvement 5 months after ASA (p = 0.05). There was no significant difference in mitral inflow velocity or LA volume index at baseline when compared to 5 months following therapy for patients who underwent ASA (p > 0.05 for all) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of baseline and 5-month * outcomes between alcohol septal ablation and mavacamten for (A) average E/e’, (B) lateral e’, and (C) septal e’. * The 5-month endpoint was an approximation with an average of 5.1 months and an interquartile range of 3.5–6.0 months.

Similarly, mavacamten treatment was associated with changes in multiple parameters of diastolic function after 5 months of therapy (Table 2). There was an increase in septal E’ (6.0 versus 6.7, p = 0.005) with a trend towards improvement in lateral E’ (5.7 versus 7.0, p = 0.06) with mavacamten (Table 2, Figure 2). There was a reduction in each of septal E/e’ (16.3 versus 13.1, p = 0.03), lateral E/e’ (14.3 versus 11.3, p = 0.03), and average E/e (17.4 versus 13.5, p = 0.01) (Table 2, Figure 2). Mavacamten therapy was also associated with an improvement in the LA volume index (45.6 versus 34.5, p < 0.001). There was no difference in LA reservoir strain with mavacamten treatment. Additionally, there was no change in mitral E or E/A when comparing baseline to 5-month follow-up among patients who were treated with mavacamten (Table 2).

Mitral inflow velocities (E) and E/e’ values (lateral, septal, and average) were not different between the ASA and mavacamten arms at baseline or after 5-month follow-up. The ratio of passive versus active mitral filling velocity (E/A) was similar at baseline and greater in the mavacamten arm compared to ASA at 5-month follow-up (0.8 versus 1.1, p = 0.001). LA volume index was greater in the mavacamten arm at baseline (36.2 versus 45.6, p = 0.039); however, no difference was seen at 5-month follow up (35.0 versus 34.5, p = 0.90) (Table 2).

4. Discussion

Cardiac myosin inhibitors (CMIs) have emerged as a tool in the management of obstructive HCM. CMIs have been shown to not only reduce myocardial contractility and outflow tract obstruction, but emerging evidence finds that they are also associated with improvements in diastolic function [22,24,27,28]. In this study, we compare mavacamten to ASA to examine how each of these approaches modifies echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function. Our observations find that ASA and mavacamten yield comparable improvements in LVOT obstruction and echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function.

Specifically, we observe that both ASA and mavacamten are associated with significant improvements in mitral annular tissue velocity (e’) and left-sided filling pressures as determined by E/e’ after 5 months. With mavacamten both septal and lateral e’ improved over time; however, only lateral e’ improved to meet the threshold of statistical significance with ASA. Interpretation of septal e’ velocities should be tempered by the knowledge that this may not be a reliable measure of diastolic function in patients who have undergone ASA [29]. It has been proposed that direct injury of the basal septum by ASA results in tissue fibrosis and thereby diminishes tissue velocities and the sensitivity of septal e’ as a measure of diastolic function.

In addition to diastolic function, those in the mavacamten group showed a statistically significant decrease in LAVI at 5-month follow up. Given the small size of the study, this finding would require further validation in a larger cohort.

Differences in clinical characteristics between our study groups are present and thereby limit the reliability of direct comparison. The study groups were comprised of individuals with similar BMIs and sex-ratios; however, patients in the ASA arm were older and more likely to have prior tobacco exposure. Individuals in the ASA cohort were also more likely to have been treated with non-dihydropyridine CCB and/or disopyramide compared to their mavacamten-treated counterparts. The differences observed may reflect an overall older and sicker population in the ASA arm. Indeed, a larger fraction of patients in the ASA arm reported functional limitations that met NYHA Class III criteria. Nevertheless, despite these clinical differences, there was no difference in LVOT obstruction, mitral inflow velocity (E), lateral and septal e’ values, and left-sided filling pressures as determined by E/e’ at baseline.

Lastly, the small study size, single-center focus, and retrospective nature limit the generalizability of these observations. Short-term follow-up impedes determination of long-term features of this comparison. Large multi-center trials with extended follow-up will be required to address these questions. Furthermore, longer-term follow-up may show more significant improvements in diastolic function parameters, including LAVI. At this time, follow-up was likely too short to see improvement in all diastolic parameters.

We previously reported that ASA and mavacamten yielded comparable performance characteristics with respect to hemodynamic parameters (LVOT, ejection fraction, and mitral regurgitation) and associated improvement in patient functional status (NYHA class) [23]. This is the first study of its kind to compare improvements in echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function between patients who underwent ASA against those who were treated with mavacamten. Importantly, these data suggest that relief of outflow tract obstruction, independent of therapeutic approach, may be sufficient to improve hemodynamic parameters that define diastolic function. Undoubtedly, larger studies are required to further characterize the relative efficacy of the two therapeutic modalities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcdd13010016/s1, Table S1: Demographics, comorbidities, and medications of the sample population prior to excluding patients who did not have echocardiographic follow-up of diastolic function parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., L.C. and P.C.C.; methodology, D.S., L.C., A.S.B. and P.C.C.; formal analysis, Z.M. and A.S.B.; data curation, D.S., K.H., A.S., M.S., E.Y.K. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, D.S.; supervision, L.C. and P.C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University (protocol code STU00219379, approval date 6 September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as this was a retrospective analysis that was approved by the IRB, as listed above.

Data Availability Statement

Primary data can be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Abigail Garza BSN RN and Kayla Mueller BSN RN for their efforts in organizing clinical information and coordinating care for the HCM patients cared for at Northwestern Memorial Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Baljash Cheema has served as a consultant for Caption Health, Inc and Viz.ai; is a speaker with honorarium from Bristol Myers Squibb; has served on an Advisory Board for Novo Nordisk; and is an advisor with equity interest in Healthspan, Inc and Zoe Biosciences. Dr. Vera H. Rigolin has stock ownership in Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Paul C. Cremer reported receiving grants from Novartis and Kiniksa and receiving personal fees from Kiniksa, Sobi, and CardiolRx Therapeutics outside the submitted work. Dr. Lubna Choudhury coauthored the SEQUOIA-HCM study of aficamten, and the MAVERICK-HCM study on non-obstructive HCM. Additionally, she was an investigator of the EXPLORER-HCM study of mavacamten in obstructive HCM, MAPLE-HCM, a study examining the efficacy of aficamten versus Metoprolol for obstructive HCM; a current investigator in ACACIA-HCM, a study examining the efficacy of aficamten in non-obstructive HCM; FOREST-HCM, a long-term effects study of aficamten in obstructive and non-obstructive HCM; and MAVA-LTE, a long-term effects study of mavacamten in obstructive and non-obstructive HCM.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HCM | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| ASA | Alcohol septal ablation |

| LA | Left atrium |

| LVOT | Left-ventricular outflow tract |

| SRTs | Septal reduction therapies |

| IVS | Interventricular septum |

| REMS | Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy |

| LVEF | Left-ventricular ejection fraction |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| ASE | American Society of Echocardiography |

| BMP | Body mass index |

| CMIs | Cardiac myosin inhibitors |

| LAVI | Left-atrial volume index |

References

- Maron, B.J. Clinical Course and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommen, S.R.; Ho, C.Y.; Asif, I.M.; Balaji, S.; Burke, M.A.; Day, S.M.; Dearani, J.A.; Epps, K.C.; Evanovich, L.; Ferrari, V.A.; et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR Guideline for the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 2324–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massera, D.; McClelland, R.L.; Ambale-Venkatesh, B.; Gomes, A.S.; Hundley, W.G.; Kawel-Boehm, N.; Yoneyama, K.; Owens, D.S.; Garcia, M.J.; Sherrid, M.V.; et al. Prevalence of Unexplained Left Ventricular Hypertrophy by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in MESA. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semsarian, C.; Ingles, J.; Maron, M.S.; Maron, B.J. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, A.J.; Braunwald, E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Genetics, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Circ. Res. 2017, 121, 749–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.Y.; Pozios, I.; Haileselassie, B.; Ventoulis, I.; Liu, H.; Sorensen, L.L.; Canepa, M.; Phillip, S.; Abraham, M.R.; Abraham, T.P. Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Nonobstructive, Labile, and Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e006657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrid, M.V.; Balaram, S.; Kim, B.; Axel, L.; Swistel, D.G. The Mitral Valve in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Test in Context. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Dhillon, A.; Popovic, Z.B.; Smedira, N.G.; Rizzo, J.; Thamilarasan, M.; Agler, D.; Lytle, B.W.; Lever, H.M.; Desai, M.Y. Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Patients Without Severe Septal Hypertrophy: Implications of Mitral Valve and Papillary Muscle Abnormalities Assessed Using Cardiac Magnetic Resonance and Echocardiography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2015, 8, e003132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H.; Setser, R.M.; Thamilarasan, M.; Popovic, Z.V.; Smedira, N.G.; Schoenhagen, P.; Garcia, M.J.; Lever, H.M.; Desai, M.Y. Abnormal papillary muscle morphology is independently associated with increased left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart 2008, 94, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guigui, S.A.; Torres, C.; Escolar, E.; Mihos, C.G. Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A narrative review. J. Thorac. Dis. 2022, 14, 2309–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihos, C.G.; Escolar, E.; Fernandez, R.; Nappi, F. A systematic review and pooled analysis of septal myectomy and edge-to-edge mitral valve repair in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpern, D.G.; Swistel, D.G.; Po, J.R.; Joshi, R.; Winson, G.; Arabadjian, M.; Lopresto, C.; Kushner, J.; Kim, B.; Balaram, S.K.; et al. Echocardiography before and after resect-plicate-release surgical myectomy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gati, S.; Bäck, M.; Börjesson, M.; Caselli, S.; Collet, J.P.; Corrado, D.; Drezner, J.A.; Halle, M.; et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines on sports cardiology and exercise in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 17–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D.R., Jr.; Valeti, U.S.; Nishimura, R.A. Alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Indications and technique. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2005, 66, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batzner, A.; Pfeiffer, B.; Neugebauer, A.; Aicha, D.; Blank, C.; Seggewiss, H. Survival After Alcohol Septal Ablation in Patients with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 3087–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, F.I.; Robertson, L.A.; Armas, D.R.; Robbie, E.P.; Osmukhina, A.; Xu, D.; Li, H.; Solomon, S.D. A Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Study of the Cardiac Myosin Inhibitor Aficamten in Healthy Participants. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2022, 7, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, M.S.; Masri, A.; Nassif, M.E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Arad, M.; Cardim, N.; Choudhury, L.; Claggett, B.; Coats, C.J.; Düngen, H.D.; et al. Aficamten for Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Oreziak, A.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Abraham, T.P.; Masri, A.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Saberi, S.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Wheeler, M.T.; Owens, A.; et al. Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, M.Y.; Owens, A.; Wolski, K.; Geske, J.B.; Saberi, S.; Wang, A.; Sherrid, M.; Cremer, P.C.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Tower-Rader, A.; et al. Mavacamten in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Referred for Septal Reduction: Week 56 Results from the VALOR-HCM Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, M.S.; Masri, A.; Choudhury, L.; Olivotto, I.; Saberi, S.; Wang, A.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Nagueh, S.F.; Rader, F.; et al. Phase 2 Study of Aficamten in Patients with Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitner, S.B.; Jacoby, D.; Lester, S.J.; Owens, A.; Wang, A.; Zhang, D.; Lambing, J.; Lee, J.; Semigran, M.; Sehnert, A.J. Mavacamten Treatment for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Clinical Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.M.; Lester, S.J.; Solomon, S.D.; Michels, M.; Elliott, P.M.; Nagueh, S.F.; Choudhury, L.; Zemanek, D.; Zwas, D.R.; Jacoby, D.; et al. Effect of Mavacamten on Echocardiographic Features in Symptomatic Patients with Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 2518–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samhan, A.; Saleh, D.; Kim, E.Y.; Hu, M.; Mueller, K.; Garza, A.; Schormann, E.; Bindra, P.; Cheema, B.; Fullenkamp, D.E.; et al. Comparison of Alcohol Septal Ablation with Mavacamten in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2025, 239, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.M.; Claggett, B.L.; Wang, X.; Jering, K.; Prasad, N.; Roshanali, F.; Masri, A.; Nassif, M.E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Abraham, T.P.; et al. Impact of Aficamten on Echocardiographic Cardiac Structure and Function in Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 1789–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.; Rahko, P.S.; Blauwet, L.A.; Canaday, B.; Finstuen, J.A.; Foster, M.C.; Horton, K.; Ogunyankin, K.O.; Palma, R.A.; Velazquez, E.J. Guidelines for Performing a Comprehensive Transthoracic Echocardiographic Examination in Adults: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2019, 32, 1–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, P.C.; Geske, J.B.; Owens, A.; Jaber, W.A.; Harb, S.C.; Saberi, S.; Wang, A.; Sherrid, M.; Naidu, S.S.; Schaff, H.; et al. Myosin Inhibition and Left Ventricular Diastolic Function in Patients with Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Referred for Septal Reduction Therapy: Insights from the VALOR-HCM Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, e014986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, M.Y.; Okushi, Y.; Wolski, K.; Geske, J.B.; Owens, A.; Saberi, S.; Wang, A.; Cremer, P.C.; Sherrid, M.; Lakdawala, N.K.; et al. Mavacamten-Associated Temporal Changes in Left Atrial Function in Obstructive HCM: Insights from the VALOR-HCM Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 18, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, E.; Sabate-Rotes, A.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Ommen, S.R.; Nishimura, R.A.; Dearani, J.A.; Schaff, H.V. Septal myectomy after failed alcohol ablation: Does previous percutaneous intervention compromise outcomes of myectomy? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 150, 159–167.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.