Abstract

This article considers key determinants of terroir tourism in the context of organic vineyards in Oregon, US. Emerging from anthropology, climatology, ecology, geography and wine tourism, terroir tourism has been recently recognized to have potential for developing tourism in Oregon. However, research has sought to determine terroir tourism and its characteristics, differentiating it from wine tourism. This case of Oregon will investigate a wine territory through the examination of organic vineyards. The relative importance of terroir within the organic vineyard destinations of Oregon is examined. Determining the characteristics of terroir tourism from a review on terroir and the experience economy 4E framework on wine tourism develops the case into organic vineyards with terroir tourism characteristics. Ultimately, an attempt to further develop wine tourism destinations based on their unique terroir esthetic experiences, and the potential for terroir tourism within the experience economy, is developed.

1. Introduction

Wine tourism continues to grow in popularity for both researchers and tourists [1]. However, a new and related form of tourism has recently emerged—terroir tourism—which is heavily reliant on its connections to a unique territory [2]. Research suggests that the characteristics of a region, place, or land within a territory define the attributes of terroir tourism [2]. The term ‘terroir’, a French term derived from terre (land), has been used to denote the special characteristics of a place, interacting with plant genetics in agricultural products such as wine, coffee, chocolate, tea, and cheese [3]. Particularly, French winemakers employed the concept of terroir by identifying differences in wines from different regions, or vineyards. The concept of terroir is developed as a way of describing the unique aspects of a place, which influence and shape the wine made from it [4].

Terroir can be defined as sense of place, which points to the unique characteristics of the local environment to produce certain qualities of the product [5]. The history of terroir and grape growth and their symbiotic nature from agricultural product to consumer offering provides a relationship that is unique to few products, like organic wine and the place where the grapes are grown. Further investigation into the potential experiences of terroir tourists in organic vineyards is, therefore, warranted. That being said, terroir is an understudied field. Although authenticity and unique experiences are present in all vineyards and places, the emergence of terroir characteristics within terroir tourism provides support for further investigation into vineyards that are designated as organic. This investigative paper examined Oregon, US, as an organic wine territory.

As of 2015, the total sustainable planted acres of vineyards in Oregon, US, was 12,502. Fifty-two percent of the total planted acres are considered certified vineyard acres. The state of Oregon, with its high percentage of organic vineyards that hold unique terroir characteristics, could capitalize on the opportunity to specifically market themselves to the segment of terroir tourists particularly interested in organic grape production. The Oregon Tilth has certified 1,600 acres as meeting the USDA standard for organic grape production for the value-added product of organic wine (Table 1) [6]. Ultimately, organic viticultural practices seek to preserve and protect the natural environment as well as maintain the naturalistic qualities of the wine produced from the region. Hence, these practices make Oregon a potential organic wine destination, which share many characteristics with terroir tourism. Furthermore, the practices associated with organic, sustainable winemaking are really the traditional ones [7].

Table 1.

Oregon’s Organic Vines (Adapted from [8], with permission from Oregon Organic Wine, 2015).

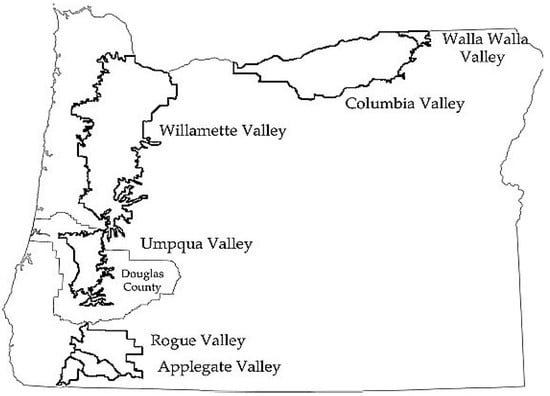

Oregon’s organic vineyard activities and distinct terroir lend themselves to a more themed experience than conventional vineyards, and offer strong terroir tourism themes through organic farming events highlighting organic wine and territory. Examples include farm-to-fork events, where dinners are held at a family style harvest table, surrounded by the beautiful bounty from organic gardens. An example of terroir tourists enjoying a themed experience is noted at Cowhorn Vineyards and Gardens in the Applegate Valley AVA (Figure 1): wine club outings that offer sips of their freshest, organic, local bio-dynamic Oregon wines, with a lovely view of the farm fields and rolling hills beyond the winery and territory [9]. As reported by Gorthy, Cowhorn owners Bill and Barabra Steele have styled their new wine tasting experience to imbibe a “living” way, which focusses on clean wine and a “green” tasting room [9]. The single-story building, clad in Oregon cedar, recycled cork, and rusty Corten steel sits at the heart of the winery and vineyard operations. The interior space, large patio and partially covered wood deck allow visitors to savor the site while also observing up-close the farming and processing practices. This offers guests at the organic vineyard and gardens a themed terroir experience.

Figure 1.

The spatial depiction of Oregon’s American Viticultural Areas (AVAs). (Adapted from [10], with permission from Jones, 2004).

2. Literature Review

Previous literature has demonstrated the importance and effectiveness of segmenting wine consumers based on their motivations and behaviors as wine tourists [11,12], and psychographically, using measures such as wine tourism involvement and wine knowledge [13]. Regardless of type, segmenting wine tourists is an important component of understanding terroir tourism consumer behavior because of their varying interests in wine and grape production within a territory. Getz and Brown studied the motivation and behavior of wine consumers in Calgary, Canada, and found these tourists to be primarily cultural tourists, interested in wine and food, and outdoor recreational opportunities [14]. Whereas in China, while learning about wine and winemaking, tasting wine and hearing stories about wine are of interest [15] Thach highlights the importance of segmenting wine consumers [16]. Segmentation of wine between conventional grape product and organic grape production is a current trend in the industry and suggests a similar segmentation for wine tourists and terroir tourists, which might provide the further development of tourism products to meet the unique experiences that each tourist desire.

An experiential view of wine tourism has been scant, although promising [17,18,19,20,21] given the hedonic nature of the experience. Quadri’s [22] dissertation study on rural wine tourism utilized the central constructs of the experience economy model, the 4Es—education, esthetics, entertainment and escapist [23]—to explain the experiential nature of wine tourism. The suitability of this framework to help understand the greater wine tourism experience has been developed in several studies, as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indicators of 4Es in literature with regard to wine tourists (adapted from [21], with permission from Quadri-Felitti & Fiore, 2012).

Examples of experience-based activities for wine tourists, with respect to the 4E framework, include [21]:

Education

- Wine tastings and seminars

- Culinary-wine pairing events

- Home wine-making seminars

- Cooking and craft-making classes

Entertainment

- Cellar concerts, music in the vineyard

- Wine-blending demonstration

- Farm and food demonstrations

Escapist

- Vineyard hikes, cycling tours

- Hot air ballooning over vineyards

- Vineyard tours by horse and carriage

Esthetics (enriched by sensual environments)

- Consuming the ‘winescape’

- Enjoying unique lodging (B&B) and wines

- Driving along rural roads lined with vineyards

- Art and craft fairs at wineries

The esthetic experience entails immersion in a sensual environment. The winescape reflects this opportunity and has proven to be fundamental for wine tourism [17]. Terroir tourism activities at organic vineyards are noted in Oregon as an esthetic experience. Experiences like soil sampling, geologic digs, and terroir walks and talks are offered at the Momtazi organic vineyard and Maysara winery in McMinville, Oregon [24]. The Montazi vineyard is the largest planted Demeter Biodynamic Certified in Oregon with 532 acres of planted grapes [25] and the largest biodymanic wine producer in the state. While some businesses may engage customers primarily through one realm of experience, many offer experiences that encompass multiple realms. An experience that encompasses all four realms is said to hit the ‘sweet spot’ in the middle of the framework—a ‘mnemonic place’ that is distinct from the everyday norm and is only possible through the staging and theming of an experience [26]. For instance, a goat farmer who makes Neufchâtel, a cheese originally from the town of the same name in the region of Normandy, France, may find it appropriate to build a Bed & Breakfast or retail store esthetic experience around a French provincial theme [27].

Theming

For Pine & Gilmore, before an experience can be staged, it must be successfully themed [23]. Furthermore, theming an experience means scripting a story reliant upon guests’ participation. Similarly, effective interpretation at a winery follows an overarching theme unique to the vineyard. According to Pine & Gilmore, five key principles define successful creation of a theme: (1) An engaging theme must alter a guest’s sense of reality; (2) the richest venues possess themes that fully alter one’s sense of reality by affecting the experience of space, time, and matter; (3) engaging themes integrate space, time and matter into a cohesive, realistic whole; (4) themes are strengthened by creating multiple places within a place; (5) a theme should fit the character of the enterprise staging the experience [23]. Each of these principles seem to point to the fact that the theme should enhance a sense of place for the visitors, as well as an important goal for an interpretive theme. Interpretation can serve as a winery’s primary form of communication with their audience.

In order to fulfill these purposes, businesses create interpretive plans. Many times, businesses start out solely selling goods or offering services and want to add value by offering distinct customer experiences. The mix of goods and services offered by small firms can range from very focused to diverse. These goods and services may offer cues for the kind of theme or impression around which to build experiences. Therefore, terroir tourism is constructed by theming a destination before it can be successfully staged as a territory with terroir characteristics.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Terroir has been used to explain agriculture for centuries, but the discourse on terroir has recently promoted the association of ‘place’ and product quality in the minds of many consumers [3]. With respect to wine, many people believe that all of the features of a winegrowing region taken as a whole—its terroir—culminate in a distinctive influence that can be tasted in the wine [28]. The three different levels of terroir as described by Thach [16] were investigated to help characterize terroir tourism characteristics: (1) The literal level, meaning “earth or soil” [29]; (2) the environmental level, including “climate, sunlight, topography, geology; and soil/water relations” [30]; and (3) the holistic level, which includes “all of the above plus viticulture and winemaking practices, as well as desires of the consumer and the local community” [31].

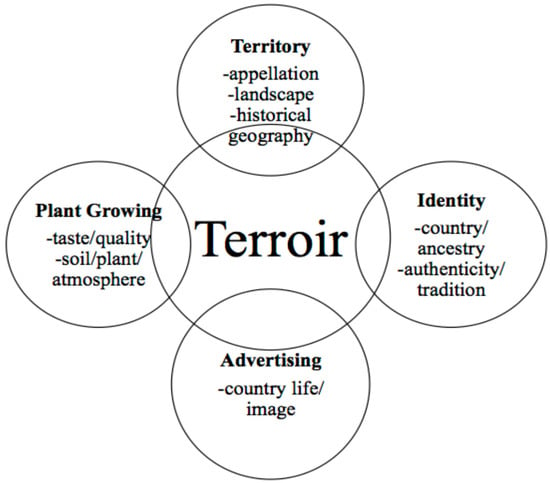

Vaudour characterized viticultural terroir (grape growing), as four components: plant growing, territory, advertising, and identity (Figure 2) [32]. The plant growing terroir is based on the notion that the quality of agricultural products is related to the agronomic properties of a farmed environment. The territory aspect of terroir, which is expressed in Europe through appellation systems and over time becomes a historical geography—think, for instance, of the storied wines from Burgundy or Bordeaux—has been examined in this investigation within Oregon, an organic wine production region.

Figure 2.

A typology of viticultural terroir (adapted from [32], with permission from Vaudour, 2002).

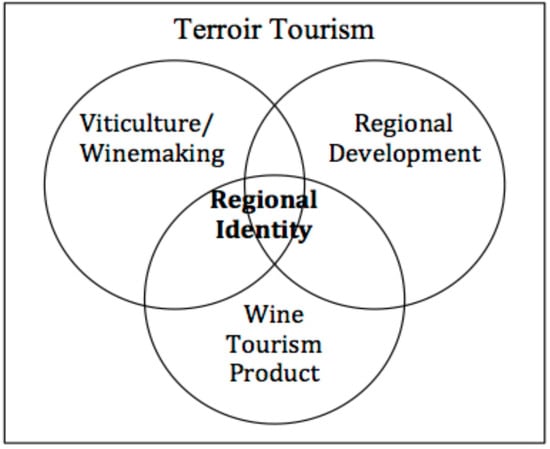

Holland et al. developed a framework of terroir tourism with regional development, wine tourism product and viticulture and winemaking components to form regional identity (Figure 3) [33]. Moran [34] suggests that the importance of human involvement should be factored into crafting terroir at the holistic level as well: “Great wines…are created by people understanding where they work and expressing its qualities quality in their product” [35]. The geographical characteristics of terroir and associated human interaction together construct the cultural landscape of the locality (place or region)—a set of conditions for producing high-quality culinary products with creative and artistic characteristics of the place (place identity and image), which reflect their place of origin [36]. To capitalize on these characteristics, terroir can be and is often used in marketing as an image for a winegrowing region [37]. A scientific approach to researching the characteristics of terroir tourism will also develop on previous experiments that have clearly shown that numerous aspects of terroir can be specified [38]. As suggested by Jones [38], Marlowe and Lee share that territory is most closely characterized in the literature investigating terroir and tourism together [2]. Their findings indicate that territory terms such as a region, land, and place are relevant keywords to reveal the characteristics of terroir tourism. The strongest terroir tourism characteristic is, therefore, the territory within a place, giving it distinctive destination quality and is not simply the wine region as a whole [2].

Figure 3.

A conceptual framework of terroir tourism (adapted from [33], with permission from Holland et al., 2014).

While a wine region’s wine tourism traditionally connects the identity of a winery to regional location externalities without addressing the question of terroir, terroir categories like territory are key potential elements of location choices for terroir tourists. Furthermore, these terroir categories are private resources, rather than externalities. Organic vineyards provide these private resources for Oregon wineries and their vineyards, which reinforces the connection between organic viticultural practices and terroir tourism potential in Oregon.

Oregon’s wineries are already globally recognized for its sustainability practices. Another trend putting this region in the spotlight is the production of organic wine. Although Oregon has only about 13,000 acres of wine grapes compared to California’s 450,000-plus acres, it is estimated that over 50 percent of Oregon’s vineyards are sustainable or organic compared to California’s one percent. Therefore, the unique terroir of Oregon and the organic vineyard sites, which make up such a high percentage of Oregon’s overall grape and wine industry, make it an ideal terroir-driven destination. A regional identity to support the continued experiential nature of terroir also needs policy partners to preserve the place that possesses terroir. In this case for Oregon, 23 percent of its vineyards have met very stringent certification guidelines and are LIVE-certified sustainable or organic [8].

This article investigating experience economy research on wine tourism and the development of organic vineyards in Oregon expects to add to the applied research of Oregon as an emerging terroir tourism destination. Terroir tourism has the potential to be developed further by applying the characteristics of terroir from a vine perspective to marketing the state as a sustainable wine destination through the organic production of wine. Terroir tourism development, as part of a creative food economy in rural communities, should characterize local factors building on local competitive advantages, local resources, local products, and local distinctiveness like the territory Oregon, USA and its organic vines and wine. Quadri-Felitti & Fiore shared that the 4Es offer a relevant framework to examine the wine tourism experience [21]. Therefore, this investigation on terroir tourism should support further investigation using the 4E framework to conclude if similar or separate experiences for the wine tourist exist compared to terroir tourism within an emerging gastronomic tourism destination. Future research into experiencing the unique and authentic terroir of a destination and ultimately creating characteristics of the terroir tourist to support terroir driven destinations should be investigated, which will support those destinations with regional identity tied to terroir to share. Moreover, future research based on this study will have potential to create theoretical frameworks and conceptual literature on terroir tourism.

As a practical contribution, terroir tourism destinations can create unique programs aimed at highly specialized wine tourists by studying the characteristics of terroir tourism and their relationship to organic wine production. In summary, there has been increasing creative economic initiatives in place-based rural community development in recent years, and Oregon is no exception. It follows that the creative food economy in rural community development depends on promoting the region‘s agricultural sector, along with a terroir tourism strategy to include organic farming practices. These factors, contributing to the quality of life and lifestyle of local individuals and tourists alike in grape-growing and wine-producing territories, will promote organic vineyards and more sustainable production in the world of wine as unique terroir tourism destinations like Oregon become more recognized for their terroir characteristics. Jones et al. states that some regions have had hundreds and even thousands of years to define, develop, and understand their best terroir; while newer regions typically face a trial-and-error stage of finding the best variety and terroir match, and in the case of Oregon, it is its organic produce [10].

Author Contributions

Equal contributions were made by authors Marlowe and Bauman to this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dreyer, A.; Brammer, E. Wine Tourism Trends; Institute for Tourism Research, Hochschule Harz: Wernigerode, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe, B.; Lee, S. Conceptualizing terroir wine tourism. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubek, A. The Taste of Place: A Cultural Journey into Terroir; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing-Mulligan, M. Wine for Dummies; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, R. American Terroir: Savoring the Flavors of Our Woods, Waters, and Fields; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Tilth. Oregon Certified Sustainable Organic Vineyard/Winery List. 2016. Available online: http://tilth.org/organic_wineries.html (accessed on 4 June 2016).

- Tsui, Bonnie on This Oregon Trail, Pioneers Embrace Organic Wine. 2010. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/30/travel/30ecowine.html?pagewanted=all (accessed on 21 March 2017).

- Oregon Organic Wine, Oregon Certified Organic Wines. 2015. Available online: http://www.winetouroregon.com/organic_wineries.html (accessed on 4 June 2016).

- Gorthy, Joel Cowhorn Vineyard & Garden Follows Nature’s Lead in Low-Impact Agriculture, Takes Lead in Sustainable Tasting-Room Design. The Register Guard, Salem, Oregon. 2019. Available online: https://www.registerguard.com/lifestyle/20180221/cowhorn-vineyard--garden-follows-natures-lead-in-low-impact-agriculture-takes-lead-in-sustainable-tasting-room-design (accessed on 12 February 2018).

- Jones, G.V.; Snead, N.; Nelson, P. Geology and wine 8. Modeling viticultural landscapes: A GIS analysis of the terroir potential in the Umpqua Valley of Oregon. Geosci. Can. 2004, 31, 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Knight, J.; Charters, S. The winery as educator: Do wineries provide what the tourist needs? Aust. N. Z. Wine Ind. J. 2002, 16, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J. South African wine routes: Some perspectives on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famularo, B.; Bruwer, J.; Li, E. Region of origin as choice factor: Wine knowledge and wine tourism involvement influence. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2010, 22, 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, J. The Wine Tourism Experience in New Zealand: An Investigation of Chinese Visitors’ Interest and Engagement. Tour. Rev. Int. 2018, 22, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thach, L. Dirt Attractions: Do Terroir and Wine Tourism Work Together. 2011. Available online: http://www.winebusiness.com/news/?go=getArticle&dataId=92858#.U3IzYr2j9XU.email (accessed on 16 August 2017).

- Alant, K.; Bruwer, J. Wine tourism behaviour in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, G.; Mitchell, R.; Getz, D.; Crouch, G.; Ong, B. Sensation seeking and the prediction of attitudes and behaviours of wine tourists. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Wine tourism among Generations X and Y. Turizam Znanstveno-Stručni Časopis 2008, 56, 257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Pikkemaat, B.; Peters, M.; Boksberger, P.; Secco, M. The staging of experiences in wine tourism. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.L.; Fiore, A.M. Experience economy constructs as a framework for understanding wine tourism. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.L. An Experience Economy Analysis of Tourism Development along the Chautauqua-Lake Erie Wine Trail. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe, B. Organic Oregon: An emerging experience in terroir tourism. In Proceedings of the XI International Terroir Congress, McMinnville, OR, USA, 13 July 2016; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Willamette Wines. Total Certified Sustainable Acres in Oregon. 2015. Available online: http://willamettewines.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Certified-Acres-2015.pdf (accessed on June 4 2016).

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Updated Edition; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, A.M.; Kim, J. An integrative framework capturing experiential and utilitarian shopping experience. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, B. The Geography of Wine: How Landscapes, Culture, Terroir, and the Weather Make a Good Drop; Penguin Group Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Websters’s Dictionary. Definition of Terroir. 2014. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/terroir (accessed on 1 June 2016).

- Robinson, J. The Oxford Companion to Wine, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gade, D.W. Tradition, territory, and terroir in French viniculture: Cassis, France, and appellation controlee. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2004, 94, 848–867. [Google Scholar]

- Vaudour, E. The quality of grapes and wine in relation to geography: Notions of terroir at various scales. J. Wine Res. 2002, 13, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, T.; Smit, B.; Jones, G. Toward a conceptual framework of terroir tourism: A case study of the Prince Edward County, Ontario wine region. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, W. Crafting terroir: People in cool climates, soils, and markets. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Cool CLIMATE Symposium for Viticulture and Oenology, Christchurch, New Zealand, 6 February 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, W. Terroir—The human factor. Aust. N. Z. Wine Ind. J. 2003, 16, 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Croce, E.; Perri, G. Food and Wine Tourism. In Translated into English by Suzanna Miles; CABI International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, P.; Creasy, G.L. Terroir—Competing definitions and applications. Aust. N. Z. Wine Ind. J. 2003, 18, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.V. Terroir and wine, what matters most when growing grapes. Earth Magazine, 9 January 2014; 36–43. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).