Abstract

Wound dressing coverages (WDC) play a key role in protecting skin lesions and preventing infection. Polymeric membranes have been widely explored as WDC due to their ability to incorporate bioactive agents, including antimicrobial nanoparticles and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In this study, polycaprolactone (PCL)-based membranes functionalized with titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) and ibuprofen (IBP) were fabricated using a film manufacturing approach, and their structural and biocompatibility profiles were evaluated. The membranes were characterized by SEM, FTIR and XPS. Bands at 1725 cm−1, 2950 cm−1, 2955 cm−1, 2865 cm−1 and 510 cm−1 proved molecular stability of reagents during manufacture. In SEM, the control shows the flattest surface, while the PCL-IBP and PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs groups had increased rugosity. In vitro biocompatibility was evaluated using human fetal osteoblasts (hFOB). On day 3, the cell adhesion response of hFOB seeded in PCL-IBP and PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs groups showed the biggest absorbances (p = 0.0014 and p = 0.0491, respectively). On day 7 PCL-IBP group had lower lectin binding than the control (p = 0.007) and the PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs (p = 0.015) membranes, but no evidence of cytotoxicity was observed in any group. Furthermore, the Live/Dead test adds more biocompatibility evidence to conveniently discriminate between live and dead cells. The PCL polymeric membrane elaborated in this study may confer antiseptic, analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties, making these membranes ideal for skin lesions.

1. Introduction

The skin plays a crucial role in protection against environmental threats. When this barrier is disrupted, a complex biological process is initiated to restore its protective function [1,2]. The development of devices that enhance skin regeneration is therefore of significant interest, particularly for wounds associated with chronic conditions such as diabetes mellitus, vascular diseases, or prolonged mechanical pressure in critically ill patients [1,3,4].

Wound dressing coverages (WDC) are commonly applied to protect damaged skin [5], prevent infection [3], reduce pain, and promote reepithelialization [6]. In addition, WDC should be fabricated from biodegradable and biocompatible materials to ensure safe interaction with biological tissues [7]. A wide range of dressing strategies has been developed, including hydrocolloids, foam dressings, biological wound dressings, hydrogels, and polymeric films [8,9].

Synthetic biomaterials remain the primary resource for WDC fabrication due to their thermal stability, favorable mechanical properties, and ability to be readily loaded with therapeutic agents [10,11]. These properties may be exploited individually or synergistically. Accordingly, WDC have been functionalized with drugs or bioactive molecules to enhance epithelial cell migration, proliferation, and adhesion, as well as to prevent microbial infection during the wound healing process [12,13].

Polymeric membranes offer versatile control over physicochemical properties relevant to wound healing applications [14]. By adjusting parameters such as membrane flexibility, absorption, and desorption, WDCs can modulate drug release kinetics or provide moisturizing effects. Among the polymers commonly used, polycaprolactone (PCL) has attracted considerable attention and has been extensively employed in the fabrication of membranes for skin wound healing due to its biocompatibility and mechanical stability [15,16].

The control of wound-related infections remains a major clinical challenge. To address this issue, metallic nanoparticles (NPs) and antimicrobial macromolecules have been incorporated into WDC [17,18]. In particular, nanoparticles such as silver, zinc oxide, titanium dioxide (TiO2), and copper have received significant attention owing to their antimicrobial activity, high stability in biological environments, and generally favorable effects on the wound healing process [19,20].

WDC can also be functionalized with drugs to modulate the inflammatory response. The localized delivery of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) provides analgesic and antipyretic effects, thereby reducing pain and inflammation at the wound site. Ibuprofen (IBP), a widely used NSAID, inhibits cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme highly expressed in skin tissue [21]. This inhibition prevents the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins and thromboxanes, resulting in a reduction in inflammatory mediators and subsequent attenuation of pain receptor activation. Localized drug delivery minimizes systemic exposure and associated side effects, making drug-loaded WDCs an attractive strategy for controlling inflammation and improving patient comfort [22,23].

The use of PCL and TiO2 has been previously reported. This combination has been employed to fabricate fibrillar membranes for the controlled release of tetracycline [20], as well as to produce films incorporating cerium dioxide and chitosan to enhance the antibacterial performance of TiO2 [18]. However, these manufacturing approaches typically require the use of high-voltage electric fields or elevated temperatures to synthesize the wound dressing coverages and may degrade the functionalized molecules used [20,24].

Although PCL-based systems, antimicrobial nanoparticles, and anti-inflammatory drugs have been independently explored for wound healing applications, their integration into a single platform using a rapid and straightforward film manufacturing approach remains limited. For this reason, the objective of this study was to evaluate the structural characteristics and cellular response of a PCL-based WDC functionalized with TiO2 NPs and IBP. The proposed device was therefore designed to combine components with well-documented antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory potential, establishing its biocompatibility profile as a foundation for future multifunctional wound healing applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Membrane Manufacturing

The polymeric membranes were fabricated following a previously reported method, with modifications in the polymer composition [25]. Briefly, PCL pellets (polycaprolactone, MW = 70,000–90,000 g/mol; Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in a solvent mixture of acetone and chloroform (3:1, respectively) to obtain a final polymer concentration of 6% (p/v). The resulting stock solution was divided into three experimental groups. The first group consisted of pure PCL and was used as the control. The second group was supplemented with ibuprofen (PCL-IBP), while the third group contained ibuprofen and titanium dioxide nanoparticles (PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs).

For the PCL-IBP formulation, ibuprofen (Mw = 206.28 g/mol, CAS No: 15687-27-1 Merck) powder was added at a concentration of 2%. In the PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs group, 2% of ibuprofen and 0.3% of TiO2 NPs (Mw = 79.87 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich) were incorporated in the stock solution. All solutions were magnetically stirred at room temperature for 2 h to ensure complete homogenization. Subsequently, the solutions were cast into Petri dishes and allowed to dry at room temperature for 2 h. The resulting membranes were sterilized under a germicidal UV lamp (ZW30S19W-Z894, diameter 19 mm, 30 W potency, 110 V, 107 μw/cm2 irradiance) under the laminar flow cabinet for 15 min before further characterization and biological evaluation.

2.2. Membrane Characterization

The membrane samples were dehydrated using a graded ethanol series and subsequently sputter-coated with a 5 nm gold layer (EMS 150R, Quorum, East Sussex, UK). Surface morphology was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-6700, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. SEM images were acquired at magnifications of 50×, 100×, and 500×.

Molecular characterization was performed by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Thermo Scientific Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. Spectra were recorded in the range of 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. Additionally, crystalline phase analysis was conducted by X-ray (XRD) using a diffractometer operating in Bragg–Brentano geometry with Cu-Kα lamp (λ = 1.5417 Å) over a range of 2θ = 5° to 2θ = 40°.

2.3. In Vitro Studies

The human fetal osteoblast cell line (hFOB, ATCC CRL-11372) was used for biological evaluations. hFOB cells were cultured in 75 cm2 culture flasks with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biosciences, Princeton, NJ, USA), 2.5 mM L-glutamine, and antibiotic solution (streptomycin 100 µg/mL and penicillin 100 U/mL, Sigma-Aldrich). Cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Upon reaching approximately 90% confluence, cells were trypsinized and seeded onto the membranes at a density of 3 × 104 cells/mL. Cell viability was assessed at 3, 5, and 7 days using the resazurin assay (R7017; Sigma-Aldrich). At each experimental period, 200 µL of fresh culture medium and 20 µL of resazurin were added to each well and incubated for 4 h. The absorbance was quantified using a microplate reader at 600 nm (ChroMate; Awareness Technology, Palm City, FL, USA).

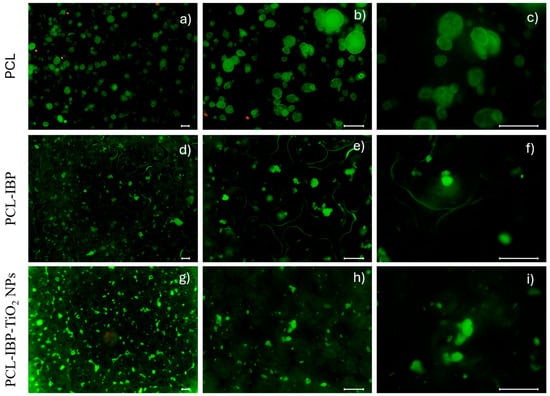

Cell–cell and cell–material interactions were further evaluated using a Live/Dead Cell Staining Kit (ENZO ALX-850-249). Briefly, 1 × 103 cells were seeded onto the membranes and incubated for 24 h. Samples were then gently washed twice with PBS and stained using a cell-permeable green fluorescent dye (Ex/Em = 488/518 nm) to label live cells, and propidium iodide (Ex/Em = 488/515 nm) to identify dead cells. Fluorescent images were acquired using a fluorescence microscope at magnifications of 10×, 20×, and 40×.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 software. The Shapiro–Wilk and Bartlett tests were employed to verify data normality and variance homogeneity. To determine significant differences among groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis was conducted. All quantitative data were expressed as the arithmetic mean with standard error of the mean, with a significance level set at α < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. FTIR and X-Ray Diffraction Analyses

In this study, polymeric WDC devices functionalized with antiseptic and analgesic components were developed. Macroscopically, all membranes exhibited a pearly white appearance and a flexible texture that allowed easy handling.

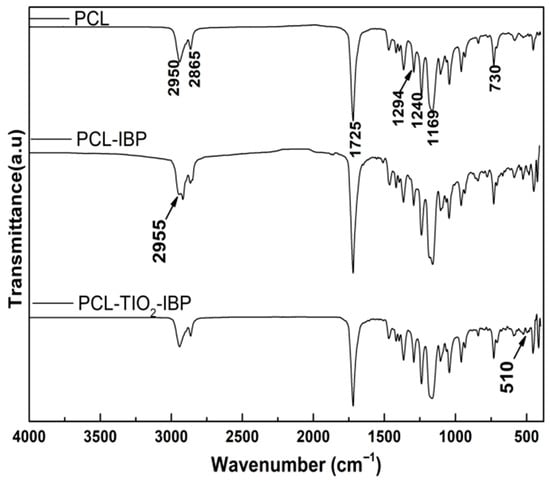

FTIR spectra of all groups showed a characteristic absorption band at 1725 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibration of the carbonyl (C=O) group [26], which is typical of PCL (Figure 1). Additionally, asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of methylene (C-H2) groups were observed at approximately 2950 cm−1 and 2865 cm−1, respectively [24].

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra. Comparative spectra of the membranes of PCL, PCL-IBP and PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs are shown. PCL: polycaprolactone. IBP: Ibuprofen. TiO2 NPs: titanium dioxide nanoparticles.

In the PCL–IBP and PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs membranes, the presence of IBP was confirmed by an absorption band at 2955 cm−1, attributed to asymmetric C-H3 stretching, as well as a band at 1240 cm−1 corresponding to C–O stretching vibrations. Furthermore, the PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs group exhibited a distinct absorption band at 510 cm−1, which can be attributed to Ti–O–Ti stretching vibrations, indicating the successful incorporation of TiO2 nanoparticles [18]. No peaks corresponding to chloroform were found at 3034 cm−1 (C-H) or 771 cm−1 (C-Cl) [27].

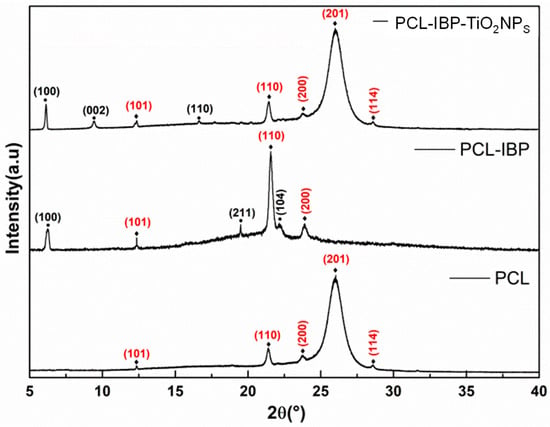

The comparative XRD patterns of the membranes are shown in Figure 2. The PCL membrane was consistent with diffraction patterns to International Crystallography Diffraction Data (ICDD) standards PDF 00-062-1286 [28] for the composites PCL-IBP and PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs. Characteristic diffraction peaks corresponding to the (101), (110), (200), (201), and (114) crystallographic planes of PCL were observed, indicating that the crystalline structure of PCL was maintained after functionalization. The presence of IBP in the composite membranes was confirmed by diffraction peaks associated with the reference pattern PDF 00-032-1723 (ICCD) [29], corresponding to the monoclinic crystalline structure of IBP, with reflections indexed to the (100), (002), (110), (211), and (104) planes.

Figure 2.

X-ray diffraction pattern. The crystallographic planes indicated with (⧫) were associated with PCL d(00-062-1286) and the crystallographic planes marked with (•) were associated with IBP (00-032-1723). PCL: polycaprolactone. IBP: Ibuprofen. TiO2 NPs: titanium dioxide nanoparticles.

3.2. Microstructural Evaluation

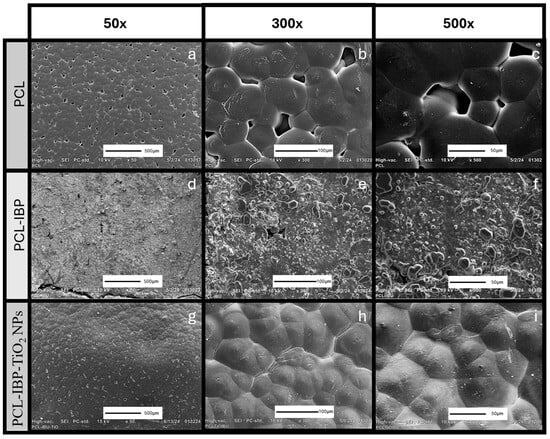

The SEM evaluation revealed distinct surface morphologies among the different membrane formulations (Figure 3). The control PCL membrane exhibited a relatively smooth and flat surface with dispersed droplet-like features and interrupted porosity (Figure 3a–c).

Figure 3.

SEM Characterization. Photomicrographs of the morphology of membranes of PCL (a–c), PCL-IBP (d–f) and PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs (g–i). 50×, 300×, 500× magnification. SEM: Scanning electron microscope. PCL: polycaprolactone. IBP: Ibuprofen. TiO2 NPs: titanium dioxide nanoparticles.

Incorporation of IBP resulted in noticeable changes in surface morphology. The PCL–IBP membranes displayed increased surface roughness accompanied by a reduction in pore density (Figure 3d–f). Interestingly, the PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs membranes showed a more homogeneous and compact surface morphology. The presence of TiO2 nanoparticles appeared to reduce the agglomeration of IBP particles, resulting in the flattest surface among all groups and a further decrease in porosity (Figure 3g–i).

3.3. Biocompatibility Evaluation

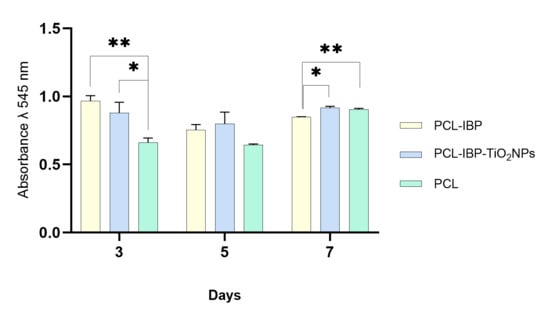

Cell–material interaction assays indicated good biocompatibility of all membrane formulations. At day 3, both the PCL–IBP and PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs groups exhibited higher resazurin absorbance values compared to the control group (Figure 4). The absorbance values of the PCL–IBP (0.965) and PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs (0.879) groups were not significantly different from each other (p = 0.3350), while both were significantly higher than the control group (p = 0.0014 and p = 0.0491, respectively).

Figure 4.

Cell viability test. The hFOB response seeded onto the surface of PCL, PCL-IBP, and PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs indicates the biocompatibility of scaffolds. All data was present as mean, standard error and α < 0.05. PCL: polycaprolactone. IBP: Ibuprofen. TiO2 NPs: titanium dioxide nanoparticles. *: p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

At day 7, no evidence of cytotoxicity was observed in any of the evaluated groups. The absorbance value of the PCL–IBP group (0.847) was lower than that of the control group (0.904; p = 0.007) and the PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs group (0.915; p = 0.015). In contrast, no statistically significant difference was observed between the control and PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs groups (p = 0.475), suggesting sustained cell viability in the presence of TiO2 nanoparticles.

Live/Dead staining further supported the biocompatibility of the membranes (Figure 5). The control PCL group exhibited a higher proportion of dead (red) cells compared to the composite groups; however, live (green) cells predominated in all cases. In the PCL–IBP group, material autofluorescence outlined the scaffold perimeter and promoted the formation of cell clusters in the central region, where a high density of viable cells was observed. The PCL–IBP–TiO2 NPs membranes showed a more homogeneous distribution of live cells across the surface, while reduced porosity was evident due to material autofluorescence.

Figure 5.

Live/Dead test. The fluorescent images of membranes at different magnifications (10×, 20×, 40×) of PCL (a–c), PCL-IBP (d–f) and PCL-IBP-TiO2 NPs (g–i), PCL: polycaprolactone. IBP: Ibuprofen. TiO2 NPs: titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Bar = 100 µm.

4. Discussion

In this study, polymeric WDC devices were developed using PCL-based membranes. PCL has been widely employed in medical applications due to its biodegradability, tunable mechanical properties, ease of manufacturing, and capacity to incorporate therapeutic agents [18,20,24]. These characteristics have been demonstrated in electrospun PCL-based systems functionalized with TiO2 and tetracycline for controlled drug delivery against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [30].

Electrospinning is one of the most commonly used techniques for WDC fabrication, as it enables the production of fibrous structures with controlled physical and chemical properties through the application of high-voltage electric fields [31]. However, this approach raises concerns related to the use of cytotoxic solvents and the requirement for high voltages. In the present work, we sought to combine the well-documented antimicrobial potential of TiO2 nanoparticles and the analgesic properties of ibuprofen using a manufacturing strategy that does not rely on high-voltage processing. This electric-free and straightforward fabrication method represents a simple and accessible alternative that preserves molecular integrity during membrane formation.

This assumption was supported by FTIR and XRD analyses, which indicated that the incorporation of ibuprofen and TiO2 nanoparticles did not induce detectable alterations in the chemical backbone or crystalline structure of PCL [18]. The preservation of characteristic PCL absorption bands and diffraction planes, together with the identification of IBP and TiO2-related signals, suggests that the rapid manufacturing approach enables the integration of bioactive components while maintaining structural stability, a critical requirement for wound dressing applications.

During solvent evaporation, polymer precipitation likely occurred in a non-uniform manner, resulting in heterogeneous polymer-rich regions and surface porosity, as observed in SEM micrographs. Such morphological features have been reported to influence cell–material interactions by modulating focal adhesion sites and the spatial organization of adhesion-related proteins such as vinculin and paxillin [32]. Accordingly, the surface variations observed in the present membranes may have contributed to the differences in cellular distribution and adhesion behavior [33].

Fluorescence imaging revealed that cells tended to cluster within polymer-rich regions or displayed a more heterogeneous distribution in coated membranes, which may explain the observed differences in metabolic activity. The increased surface roughness of the PCL–IBP and PCL–IBP–TiO2 membranes likely enhanced initial cell adhesion, resulting in higher metabolic activity at early time points. Taken together, these findings indicate that the incorporation of ibuprofen and TiO2 nanoparticles did not induce cytotoxic effects over the evaluated period. The absence of a long-term increase in metabolic activity, particularly in the PCL–IBP group, should not be interpreted as a detrimental effect, but rather as evidence of stable cell–material interactions, since the resazurin assay reflects metabolic activity rather than cell proliferation. Under these conditions, all formulations supported sustained cellular viability, fulfilling the primary objective of establishing biocompatibility of the proposed manufacturing approach.

Metallic nanoparticles have been widely explored in WDC applications due to their antimicrobial properties. For instance, PCL membranes functionalized with gelatin and silver nanoparticles have shown dose-dependent inhibition of bacterial growth [34]. In the case of TiO2 nanoparticles, their photoactivity under UV exposure leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species, suggesting potential antimicrobial functionality in wound environments exposed to light [35]. Additionally, the incorporation of ibuprofen may contribute to localized anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects without systemic exposure. Although these functional properties were not directly evaluated in the present study, the results suggest that the proposed membranes constitute a promising platform for future multifunctional wound healing applications.

5. Conclusions

The present study describes the development of a PCL-based WDC with several potential advantages. First, the absence of high-voltage processing offers a safer and simpler manufacturing approach compared with electrospinning-based techniques. Second, the membranes were readily functionalized with ibuprofen and TiO2 nanoparticles while preserving molecular integrity, as confirmed by spectroscopic analyses. Third, the integration of bioactive components with reported antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory potential suggests that the proposed system may serve for wound care applications. Finally, the photoactive properties of TiO2 nanoparticles further support the suitability of these membranes for external skin injuries. Overall, the developed WDCs demonstrated manufacturing stability and favorable biocompatibility with hFOB cells, fulfilling the objective of establishing a safe and structurally stable platform for future wound healing applications.

Author Contributions

J.A.V.-L.N. conceptualization, formal analysis, wrote the final manuscript; A.P.-G. provided critical revisions, approved the final version of the manuscript; M.O.-M. performed FTIR and data analysis; M.A.Á.-P. performed SEM analysis, wrote and revised the final manuscript; I.A.N.-T. performed X-ray diffraction and data analysis; S.M.F. cell culture standardization and biocompatibility evaluation; F.C.V.-V. conceived the original idea, provided critical revisions, approved the final version of the manuscript, and obtained funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We appreciate the support provided by the “Secretaria de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación” (SECIHTI) through its scholarship (number: A220027 and CVU: 892519) to Jael Adrian Vergara-Lope Nuñez) during his Doctoral studies in the Program “Ciencias Quimicobiológicas” of the ENCB-IPN. The present work was funded by the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México grant numbers UNAM-DGAPA-PAPIIT-IA208324 and PAPIIT-IT200424.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank DGAPA-PAPIIT. We thank Tech Teresa Baeza Kingston, for her technical support, and IIM-UNAM technicians Adriana Tejeda Cruz, Miguel Angel Canseco, Carlos Flores, for their collaboration in the following techniques: XDR, FTIR, and SEM.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WDC | Wound Dressing Coverage |

| NSAID | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory |

| PCL | Polycaprolactone |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| TiO2 | Titanium Dioxide |

| IBP | Ibuprofen |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

References

- Grada, A.; Phillips, T.J. Nutrition and Cutaneous Wound Healing. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 40, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanchetta, F.C.; De Wever, P.; Morari, J.; Gaspar, R.C.; Prado, T.P.D.; De Maeseneer, T.; Cardinaels, R.; Araújo, E.P.; Lima, M.H.M.; Fardim, P. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Chitosan/HPMC/Insulin Hydrogel for Wound Healing Applications. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, A.I.; Marza, S.M.; Dragomir, M.F.; Negoescu, A.; Sarosi, C.; Novac, C.S.; Pestean, C.; Moldovan, M.; Oana, L. The Potential of Composite Cements for Wound Healing in Rats. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, J.; Beeson, T.; Dillon, J.; Yang, Z.; Mravec, M.; Malloy, C.; Cuddigan, J. Hospital-Acquired Pressure Injuries and Acute Skin Failure in Critical Care: A Case-Control Study. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2021, 48, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Le, H.; Chang, F. Functional Hydrogel Dressings for Treatment of Burn Wounds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 788461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Júnior, E.M.; De Moraes Filho, M.O.; Costa, B.A.; Fechine, F.V.; Vale, M.L.; Diógenes, A.K.D.L.; Neves, K.R.T.; Uchôa, A.M.D.N.; Soares, M.F.A.D.N.; De Moraes, M.E.A. Nile Tilapia Fish Skin–Based Wound Dressing Improves Pain and Treatment-Related Costs of Superficial Partial-Thickness Burns: A Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2021, 147, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheokand, B.; Vats, M.; Kumar, A.; Srivastava, C.M.; Bahadur, I.; Pathak, S.R. Natural Polymers Used in the Dressing Materials for Wound Healing: Past, Present and Future. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 1389–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Ngoc Le, T.T.; Nguyen, A.T.; Thien Le, H.N.; Pham, T.T. Biomedical Materials for Wound Dressing: Recent Advances and Applications. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 5509–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wu, B.; Zou, K.; Chen, H. Efficacy of Different Types of Dressings on Pressure Injuries: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 5857–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobi, R.; Ravichandiran, P.; Babu, R.S.; Yoo, D.J. Biopolymer and Synthetic Polymer-Based Nanocomposites in Wound Dressing Applications: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderibigbe, B.A. Hybrid-Based Wound Dressings: Combination of Synthetic and Biopolymers. Polymers 2022, 14, 3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesko, A.; Petkova, P.; Tzanov, T. Hydrogel Dressings for Advanced Wound Management. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 25, 5782–5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protzman, N.M.; Mao, Y.; Long, D.; Sivalenka, R.; Gosiewska, A.; Hariri, R.J.; Brigido, S.A. Placental-Derived Biomaterials and Their Application to Wound Healing: A Review. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Vázquez, F.C.; Arenas-Alatorre, J.; Chavarría-Bolaños, D.; Pozos-Guillén, A.; Alvárez-Pérez, M.A.; Ortiz-Magdaleno, M. Cellular Response of Surface Functionalized Polymeric Fiber Mesh Coating Onto Dental Titanium Implants. Odovtos Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2024, 26, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Liang, S.; Lin, P.; Lai, X.; Lan, X.; Wang, H.; Tang, Y.; Gao, B. Phase Change Material-Embedded Multifunctional Janus Nanofiber Dressing with Directional Moisture Transport, Controlled Release of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs, and Synergistic Antibacterial Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 52244–52261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, H.; Sofini, S.P.S.; Balasubramanian, D.; Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. Biomedical Applications of Natural and Synthetic Polymer Based Nanocomposites. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 35, 269–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merzougui, C.; Miao, F.; Liao, Z.; Wang, L.; Wei, Y.; Huang, D. Electrospun Nanofibers with Antibacterial Properties for Wound Dressings. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2022, 33, 2165–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmugam, A.; Sellappan, L.K.; Manoharan, S.; Rameshkumar, A.; Kumar, R.S.; Almansour, A.I.; Arumugam, N.; Kim, H.-S.; Vikraman, D. Development of Chitosan-Based Cerium and Titanium Oxide Loaded Polycaprolactone for Cutaneous Wound Healing and Antibacterial Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando-Magraner, E.; Bellot-Arcís, C.; Paredes-Gallardo, V.; Almerich-Silla, J.M.; García-Sanz, V.; Fernández-Alonso, M.; Montiel-Company, J.M. Antibacterial Properties of Nanoparticles in Dental Restorative Materials. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2020, 56, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, A.I.; Lee, J.Y.; Son, B.C.; Park, C.H.; Kim, C.S. Bi-Layered Nanofibers Membrane Loaded with Titanium Oxide and Tetracycline as Controlled Drug Delivery System for Wound Dressing Applications. Polymers 2019, 11, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasabova, I.A.; Uhelski, M.; Khasabov, S.G.; Gupta, K.; Seybold, V.S.; Simone, D.A. Sensitization of Nociceptors by Prostaglandin E2–Glycerol Contributes to Hyperalgesia in Mice with Sickle Cell Disease. Blood 2019, 133, 1989–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainza, G.; Villullas, S.; Pedraz, J.L.; Hernandez, R.M.; Igartua, M. Advances in Drug Delivery Systems (DDSs) to Release Growth Factors for Wound Healing and Skin Regeneration. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2015, 11, 1551–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeira, R.S.; Miguel, S.P.; Cabral, C.S.D.; Moreira, A.F.; Ferreira, P.; Correia, I.J. Development of a Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Lysine Electrospun Membrane-Based Drug Delivery System for Improved Skin Regeneration. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 570, 118640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustine, R.; Hasan, A.; Patan, N.K.; Augustine, A.; Dalvi, Y.B.; Varghese, R.; Unni, R.N.; Kalarikkal, N.; Al Moustafa, A.; Thomas, S. Titanium Nanorods Loaded PCL Meshes with Enhanced Blood Vessel Formation and Cell Migration for Wound Dressing Applications. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19, 1900058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Vazquez, F.C.; Chavarria-Bolaños, D.; Ortiz-Magdaleno, M.; Guarino, V.; Alvarez-Perez, M.A. 3D-Printed Tubular Scaffolds Decorated with Air-Jet-Spun Fibers for Bone Tissue Applications. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cedillo, E.; Ortega-Lara, W.; Rocha-Pizaña, M.R.; Gutierrez-Uribe, J.A.; Elías-Zúñiga, A.; Rodríguez, C.A. Electrospun Polycaprolactone Fibrous Membranes Containing Ag, TiO2 and Na2Ti6O13 Particles for Potential Use in Bone Regeneration. Membranes 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasalle, B.S.I.; Pandian, M.S.; Ramasamy, P. Molecular Interactions Studies on Chloroform in the Environment of O-Cresol: FTIR Spectroscopy and Quantum Chemical Calculations. Braz. J. Phys. 2023, 53, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDF 00-062-1286; Database for Materials Characterization. International Center for Diffraction Data (ICDD): Newton Square, PA, USA, 2024.

- PDF 00-032-1723; Database for Materials Characterization. International Center for Diffraction Data (ICDD): Newton Square, PA, USA, 2024.

- Safdari, F.; Gholipour, M.D.; Ghadami, A.; Saeed, M.; Zandi, M. Multi-Antibacterial Agent-Based Electrospun Polycaprolactone for Active Wound Dressing. Prog. Biomater. 2022, 11, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.; Cai, J.; Schaedel, A.-L.; Van Der Plas, M.; Malmsten, M.; Rades, T.; Heinz, A. Zein-Polycaprolactone Core–Shell Nanofibers for Wound Healing. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 621, 121809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berniak, K.; Ura, D.P.; Piórkowski, A.; Stachewicz, U. Cell–Material Interplay in Focal Adhesion Points. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 9944–9955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, S.; Ferraris, S.; Spriano, S.; Krysiak, Z.J.; Kaniuk, Ł.; Marzec, M.M.; Kim, S.K.; Szewczyk, P.K.; Gruszczyński, A.; Wytrwal-Sarna, M.; et al. Surface Potential and Roughness Controlled Cell Adhesion and Collagen Formation in Electrospun PCL Fibers for Bone Regeneration. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, X.; Du, Y.; Xu, J.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y. Development and Characterization of Novel Orthodontic Adhesive Containing PCL–Gelatin–AgNPs Fibers. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.I.S.; De Oliveira, I.N.; De Conto, J.F.; De Souza, A.M.; Batistuzzo De Medeiros, S.R.; Egues, S.M.; Padilha, F.F.; Hernández-Macedo, M.L. Photocatalytic Effect of N–TiO2 Conjugated with Folic Acid against Biofilm-Forming Resistant Bacteria. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.